Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bibliographic Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

3. New Steatotic Liver Disease Nomenclature

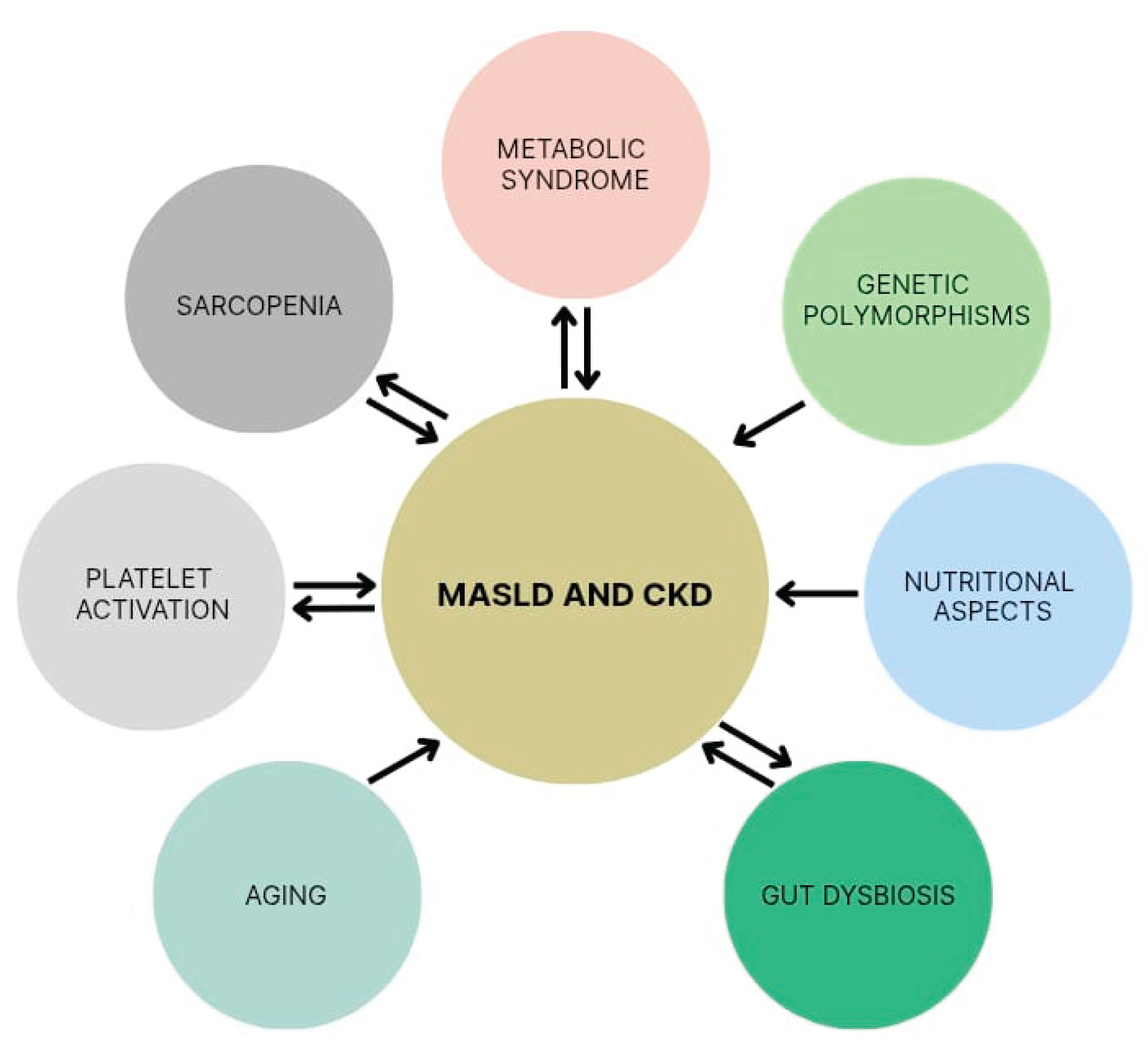

4. Shared Risk Factors Between MASLD and CKD

4.1. Metabolic Syndrome

4.2. Genetic Polymorphisms

4.3. Nutritional Aspects and Gut Dysbiosis

4.4. Aging

4.5. Platelet Activation

4.6. Sarcopenia

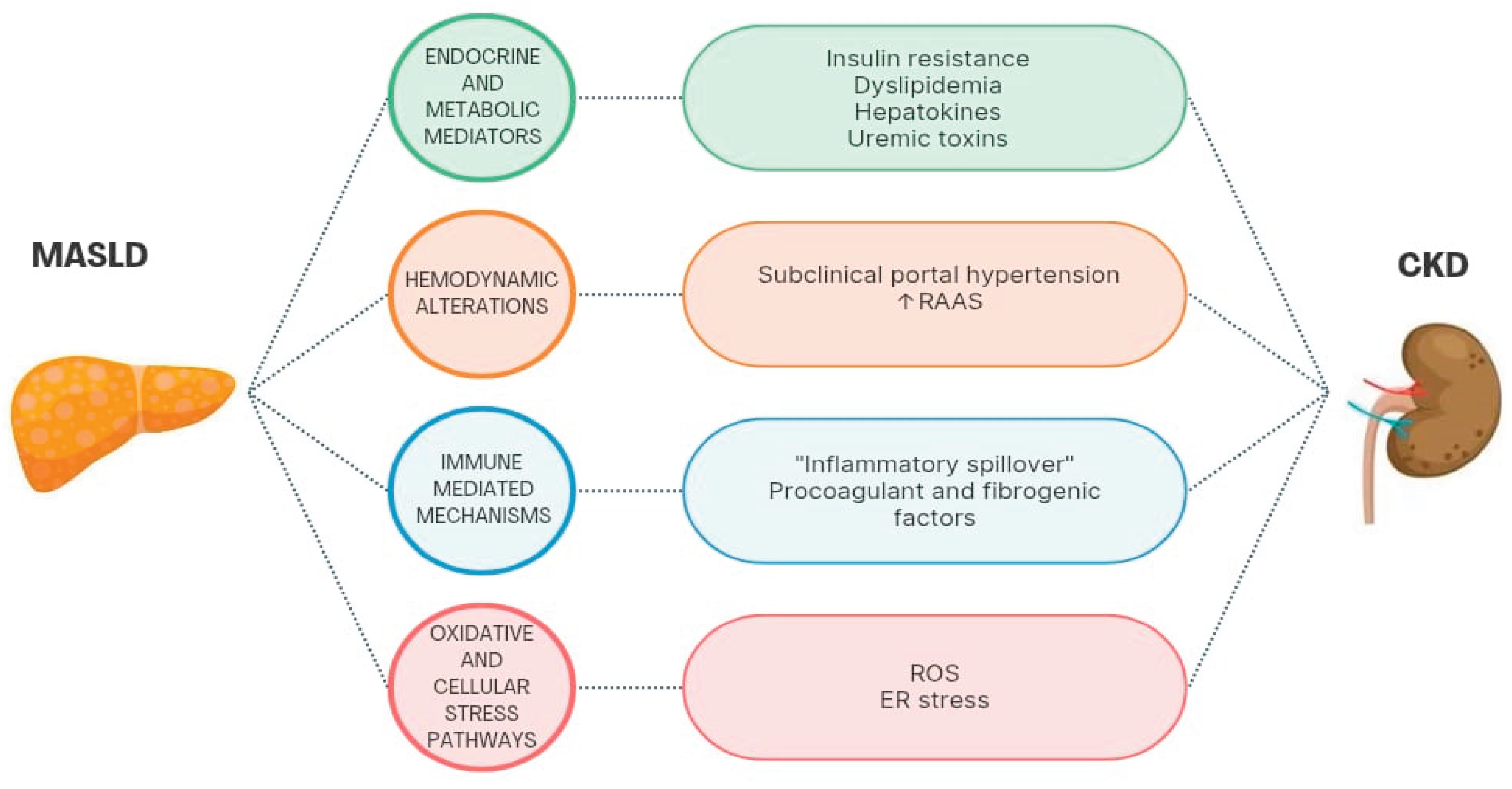

5. MASLD as a Possible Direct Cause of CKD

5.1. Endocrine and Metabolic Mediators

5.2. Hemodynamic Alterations

5.3. Immune-Mediated Mechanisms

5.4. Oxidative and Cellular Stress Pathways

6. Gaps and Limitations in Literature

6.1. Heterogeneity Among Studies

6.2. Studies in Pediatric Populations

6.3. Impact of Alcohol Intake and MetALD

6.4. Treatment Options for Both MASLD and CKD

7. Conclusions and Future Directions for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| MetALD | MASLD abd increased alcohol intake |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| NASH | Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| e-GFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| m-GFR | Measured glomerular filtration rate |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| ALD | Alcoholic liver disease |

| SLD | Steatotic liver disease |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma |

| PNPLA3 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 gene |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| FLI | Fatty liver index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases - tenth revision |

| UACR | Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| RR | Relative risk |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| HDL | High- density lipoprotein |

| ANGPTL8 | Angiopoietin-like protein 8 |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NF-KB | Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 |

References

- Rinella ME, Lazarus J V., Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023;78:1966–86. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Kalligeros M, Henry L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2025;31:S32–50. [CrossRef]

- [Lekakis V, Papatheodoridis G V. Natural history of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Eur J Intern Med 2024;122:3–10. [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol 2023;79:516–37. [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi LE, Marrone A, Rinaldi L, Nevola R, Izzi A, Sasso FC. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a systemic disease with a variable natural history and challenging management. Explor Med 2025;6. [CrossRef]

- Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao YY, Zheng MH. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2024;35:697–707. [CrossRef]

- Sun D-Q, Targher G, Byrne CD, Wheeler DC, Wong VW-S, Fan J-G, et al. An international Delphi consensus statement on metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and risk of chronic kidney disease. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2023;12:386–403. [CrossRef]

- Al Ashi S, Rizvi AA, Rizzo M. Altered kidney function in fatty liver disease: confronting the “MAFLD-renal syndrome.” Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare 2025;5. [CrossRef]

- KDIGO W. Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013;3:19–62. [CrossRef]

- Trevisani F, Di Marco F, Capitanio U, Dell’Antonio G, Cinque A, Larcher A, et al. Renal histology across the stages of chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol 2021;34:699–707. [CrossRef]

- Oshima M, Shimizu M, Yamanouchi M, Toyama T, Hara A, Furuichi K, et al. Trajectories of kidney function in diabetes: a clinicopathological update. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021;17:740–50. [CrossRef]

- Kaya E, Yilmaz Y. Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD): A Multi-systemic Disease Beyond the Liver. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2022;10:329–38. [CrossRef]

- Bilson J, Hydes TJ, McDonnell D, Buchanan RM, Scorletti E, Mantovani A, et al. Impact of Metabolic Syndrome Traits on Kidney Disease Risk in Individuals with MASLD: A UK Biobank Study. Liver International 2024. [CrossRef]

- Agustanti N, Soetedjo NNM, Damara FA, Iryaningrum MR, Permana H, Bestari MB, et al. The association between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2023;17:102780. [CrossRef]

- Musso G, Gambino R, Tabibian JH, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, Hamaguchi M, et al. Association of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001680. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Csermely A, Lonardo A, Schattenberg JM, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: an updated meta-analysis. Gut 2022;71:156–62. [CrossRef]

- Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD as a driver of chronic kidney disease. J Hepatol 2020;72:785–801. [CrossRef]

- Lonardo A, Mantovani A, Targher G, Baffy G. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical and Research Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:13320. [CrossRef]

- Zhang XL, Gu Y, Zhao J, Zhu PW, Chen WY, Li G, et al. Associations between skeletal muscle strength and chronic kidney disease in patients with MASLD. Communications Medicine 2025;5. [CrossRef]

- Caussy C, Rieusset J, Koppe L. The Gut Microbiome and the Gut-Liver-Kidney Axis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gusev E, Solomatina L, Zhuravleva Y, Sarapultsev A. The Pathogenesis of End-Stage Renal Disease from the Standpoint of the Theory of General Pathological Processes of Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:11453. [CrossRef]

- Mambrini SP, Grillo A, Colosimo S, Zarpellon F, Pozzi G, Furlan D, et al. Diet and physical exercise as key players to tackle MASLD through improvement of insulin resistance and metabolic flexibility. Front Nutr 2024;11. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela PL, Carrera-Bastos P, Castillo-García A, Lieberman DE, Santos-Lozano A, Lucia A. Obesity and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023;20:475–94. [CrossRef]

- Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:1461–5. [CrossRef]

- Nardolillo M, Rescigno F, Bartiromo M, Piatto D, Guarino S, Marzuillo P, et al. Interplay between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and renal function: An intriguing pediatric perspective. World J Gastroenterol 2024;30:2081–6. [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo S, Mantovani A, Morieri ML, Muraca E, Invernizzi P, Perseghin G. Impact of MASLD and MetALD on clinical outcomes: A meta-analysis of preliminary evidence. Liver International 2024;44:1762–7. [CrossRef]

- Stefan N, Yki-Järvinen H, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: heterogeneous pathomechanisms and effectiveness of metabolism-based treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025;13:134–48. [CrossRef]

- Byrne CD, Armandi A, Pellegrinelli V, Vidal-Puig A, Bugianesi E. Μetabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a condition of heterogeneous metabolic risk factors, mechanisms and comorbidities requiring holistic treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pipitone RM, Ciccioli C, Infantino G, La Mantia C, Parisi S, Tulone A, et al. MAFLD: a multisystem disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2023;14:204201882211455. [CrossRef]

- Loomba R, Wong VW. Implications of the new nomenclature of steatotic liver disease and definition of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2024;59:150–6. [CrossRef]

- Diaz LA, Ajmera V, Arab JP, Huang DQ, Hsu C, Lee BP, et al. An Expert Consensus Delphi Panel in MetALD: Opportunities and Challenges in Clinical Practice. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal F, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Rinella ME. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Update and impact of new nomenclature on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidance on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2024;79:1212–9. [CrossRef]

- Noureddin M, Wei L, Castera L, Tsochatzis EA. Embracing Change: From Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease to Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Under the Steatotic Liver Disease Umbrella. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2024;22:9–11. [CrossRef]

- Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020;73:202–9. [CrossRef]

- Gofton C, Upendran Y, Zheng MH, George J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:S17–31. [CrossRef]

- Pennisi G, Infantino G, Celsa C, Di Maria G, Enea M, Vaccaro M, et al. Clinical outcomes of MAFLD versus NAFLD: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Liver International 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sripongpun P, Kaewdech A, Udompap P, Kim WR. Characteristics and long-term mortality of individuals with MASLD, MetALD, and ALD, and the utility of SAFE score. JHEP Reports 2024;6. [CrossRef]

- Bilson J, Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Targher G. Steatotic liver disease, MASLD and risk of chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab 2024;50:101506. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki K, Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Takahashi Y, Yamazaki Y, Uchihara N, et al. Concordance between metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology Research 2024;54:600–5. [CrossRef]

- Sandireddy R, Sakthivel S, Gupta P, Behari J, Tripathi M, Singh BK. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024;12. [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan ED, Hughes J, Ferenbach DA. Renal Aging: Causes and Consequences. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;28:407–20. [CrossRef]

- Du K, Wang L, Jun JH, Dutta RK, Maeso-Díaz R, Oh SH, et al. Aging promotes metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease by inducing ferroptotic stress. Nat Aging 2024;4:949–68. [CrossRef]

- Hakim A, Lin KH, Schwantes-An TH, Abreu M, Tan J, Guo X, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of candidate genetic polymorphisms in a large histologically characterized MASLD cohort using a novel framework. Hepatol Commun 2025;9. [CrossRef]

- Jurek JM, Zablocka-Sowinska K, Clavero Mestres H, Reyes Gutiérrez L, Camaron J, Auguet T. The Impact of Dietary Interventions on Metabolic Outcomes in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Comorbid Conditions, Including Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2025;17. [CrossRef]

- Prasad R, Jha RK, Keerti A. Chronic Kidney Disease: Its Relationship With Obesity. Cureus 2022. [CrossRef]

- Quek J, Chan KE, Wong ZY, Tan C, Tan B, Lim WH, et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in the overweight and obese population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;8:20–30. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Zelber-Sagi S, Lazarus J V., Wai-Sun Wong V, Yilmaz Y, Duseja A, et al. Global Consensus Recommendations for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho KD, Daltro C, Daltro C, Cotrim HP. Renal injury and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with obesity. Arq Gastroenterol 2025;62. [CrossRef]

- Theofilis P, Vordoni A, Kalaitzidis RG. Interplay between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: Epidemiology, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and treatment considerations. World J Gastroenterol 2022;28:5691–706. [CrossRef]

- Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:715–25. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Price JK, Owrangi S, Gundu-Rao N, Satchi R, et al. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2024;22:1999-2010.e8. [CrossRef]

- Inukai Y, Ito T, Yokoyama S, Yamamoto K, Imai N, Ishizu Y, et al. Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension as Risk Factors for Advanced Fibrosis in Biopsy Proven Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. J Dig Dis 2025. [CrossRef]

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, Paik JM, Srishord M, Fukui N, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2019;71:793–801. [CrossRef]

- Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM, Tummalapalli SL, Ortiz A, Fogo AB, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol 2024;20:473–85. [CrossRef]

- Furuichi K, Shimizu M, Yamanouchi M, Hoshino J, Sakai N, Iwata Y, et al. Clinicopathological features of fast eGFR decliners among patients with diabetic nephropathy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020;8:e001157. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Deng H, Qin B, Bai L, Li J, Zhang J. Impact of hypertension on liver fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease 2025. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Morris E, Fletcher JA, Thyfault JP, Scott Rector R. The role of angiotensin II in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013;378:29–40. [CrossRef]

- Ng WH, Yeo YH, Kim H, Seki E, Rees J, Ma KS-K, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor use improves clinical outcomes in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver diseases: Target trial emulation using real-world data. Hepatology 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Targher G. PNPLA3 variation and kidney disease. Liver International 2025;45. [CrossRef]

- Rocha S, Oliveira CP, Stefano JT, Yokogawa RP, Gomes-Gouvea M, Zitelli PMY, et al. Polymorphism’s MBOAT7 as Risk and MTARC1 as Protection for Liver Fibrosis in MASLD. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26:6406. [CrossRef]

- Fan C-Y, Wang M-X, Ge C-X, Wang X, Li J-M, Kong L-D. Betaine supplementation protects against high-fructose-induced renal injury in rats. J Nutr Biochem 2014;25:353–62. [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, Liu Y, Yang H, Ma Z, Liu W, Zhao M, et al. Dietary fiber intake, genetic predisposition of gut microbiota, and the risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Food Research International 2025;211:116497. [CrossRef]

- Buchynskyi M, Kamyshna I, Halabitska I, Petakh P, Kunduzova O, Oksenych V, et al. Unlocking the gut-liver axis: microbial contributions to the pathogenesis of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Front Microbiol 2025;16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Wang Q, Li D, Chen S, Chen J, Zhu X, et al. Gut microbiome composition and metabolic activity in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Virulence 2025;16. [CrossRef]

- Woo C, Jeong W-I. Immunopathogenesis of liver fibrosis in steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Farris AB, Colvin RB. Renal interstitial fibrosis: Mechanisms and evaluation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2012;21:289–300. [CrossRef]

- Villarroel C, Karim G, Sehmbhi M, Debroff J, Weisberg I, Dinani A. Advanced Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Is Independently Associated With Reduced Renal Function. Gastro Hep Advances 2024;3:122–7. [CrossRef]

- Hill GS, Heudes D, Barié J. Morphometric study of arterioles and glomeruli in the aging kidney suggests focal loss of autoregulation 1. vol. 63. 2003.

- Chekol Abebe E, Tilahun Muche Z, Behaile T/Mariam A, Mengie Ayele T, Mekonnen Agidew M, Teshome Azezew M, et al. The structure, biosynthesis, and biological roles of fetuin-A: A review. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Núñez Y, Almeda-Valdes P, González-Gálvez G, Arechavaleta-Granell M del R. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and atherosclerosis. Curr Diab Rep 2024;24:158–66. [CrossRef]

- Hammerich L, Tacke F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;20:633–46. [CrossRef]

- Norman JT, Clark IM, Garcia PL. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in human renal fibroblasts. vol. 58. 2000.

- Elpek GÖ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis: An update. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:7260. [CrossRef]

- Deng C, Ou Q, Ou X, Pan D. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024;14:e078933. [CrossRef]

- Altajar S, Baffy G. Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2020;8:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Liu L, Li W. Correlation of sarcopenia with progression of liver fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a study from two cohorts in China and the United States. Nutr J 2025;24:6. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson TJ, Miksza J, Yates T, Lightfoot CJ, Baker LA, Watson EL, et al. Association of sarcopenia with mortality and end-stage renal disease in those with chronic kidney disease: a UK Biobank study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021;12:586–98. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Sun X. Does metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease increase the risk of chronic kidney disease? A meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol 2024;25:467. [CrossRef]

- Mouzaki M, Yates KP, Arce-Clachar AC, Behling C, Blondet NM, Fishbein MH, et al. Renal impairment is prevalent in pediatric NAFLD/MASLD and associated with disease severity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2024;79:238–49. [CrossRef]

- Zuo G, Xuan L, Xin Z, Xu Y, Lu J, Chen Y, et al. New Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Fibrosis Progression Associate with the Risk of Incident Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021;106:E3957–68. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Diehl A, Dasarathy S, et al. Prospective Study of Outcomes in Adults with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;385:1559–69. [CrossRef]

- Liang Y, Chen H, Liu Y, Hou X, Wei L, Bao Y, et al. Association of MAFLD with Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Cardiovascular Disease: A 4.6-Year Cohort Study in China. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2022;107:88–97. [CrossRef]

- Mori K, Tanaka M, Sato T, Akiyama Y, Endo K, Ogawa T, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (SLD) and alcohol-associated liver disease, but not SLD without metabolic dysfunction, are independently associated with new onset of chronic kidney disease during a 10-year follow-up period. Hepatology Research 2024. [CrossRef]

- Heo JH, Lee MY, Kim SH, Zheng M-H, Byrne CD, Targher G, et al. Comparative associations of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease with risk of incident chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2024;0:0–0. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhan X, Tian X, Li J, et al. Severity and Remission of Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Fatty/Steatotic Liver Disease With Chronic Kidney Disease Occurrence. J Am Heart Assoc 2024;13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Song WJ, Chen W, Pan Z, Zhang J, Fan L, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease-related hepatic fibrosis increases risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024;36:802–10. [CrossRef]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Lippi G, Franchini M, Zoppini G, et al. NASH Predicts Plasma Inflammatory Biomarkers Independently of Visceral Fat in Men. Obesity 2008;16:1394–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Yang B, Yin J, Hou C, Wang Q. Targeting Insulin Resistance and Liver Fibrosis: CKD Screening Priorities in MASLD. Biomedicines 2025;13. [CrossRef]

- Manco M, Ciampalini P, DeVito R, Vania A, Cappa M, Nobili V. Albuminuria and insulin resistance in children with biopsy proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatric Nephrology 2009;24:1211–7. [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova A, Merscher S, Fornoni A. Kidney lipid dysmetabolism and lipid droplet accumulation in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023;19:629–45. [CrossRef]

- Pal D, Dasgupta S, Kundu R, Maitra S, Das G, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Fetuin-A acts as an endogenous ligand of TLR4 to promote lipid-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med 2012;18:1279–85. [CrossRef]

- Baffy G, Bosch J. Overlooked subclinical portal hypertension in non-cirrhotic NAFLD: Is it real and how to measure it? J Hepatol 2022;76:458–63. [CrossRef]

- An JN, Joo SK, Koo BK, Kim JH, Oh S, Kim W. Portal inflammation predicts renal dysfunction in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int 2020;14:798–807. [CrossRef]

- Gurun M, Brennan P, Handjiev S, Khatib A, Leith D, Dillon JF, et al. Increased risk of chronic kidney disease and mortality in a cohort of people diagnosed with metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease with hepatic fibrosis. PLoS One 2024;19. [CrossRef]

- Lonardo A. Association of NAFLD/NASH, and MAFLD/MASLD with chronic kidney disease: an updated narrative review. Metabolism and Target Organ Damage 2024;4. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Fang Y, Zhou B, Mao G, Cheng J, Zhang X, et al. The association of systemic inflammatory biomarkers with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a large population-based cross-sectional study. Prev Med Rep 2024;37:102536. [CrossRef]

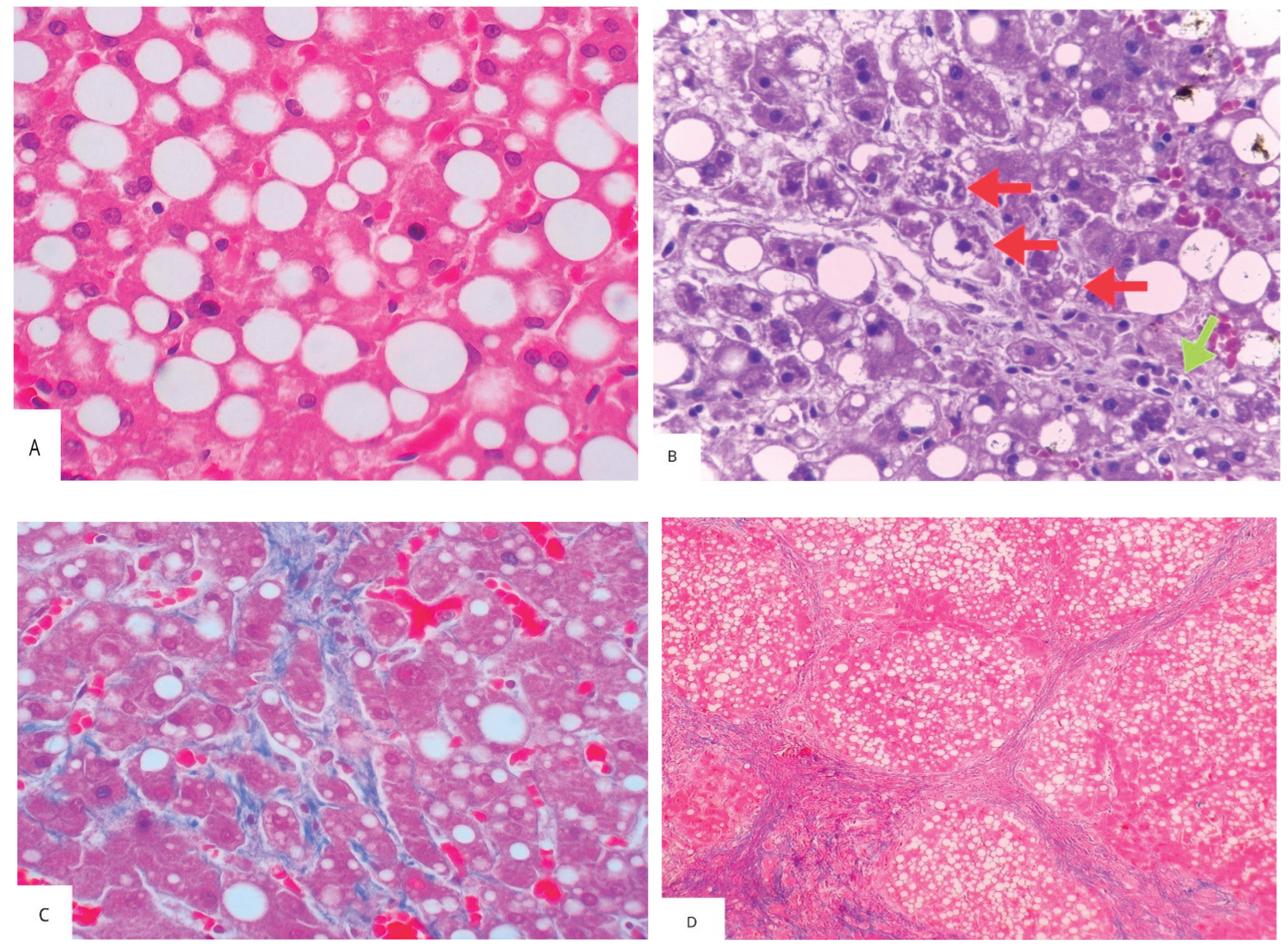

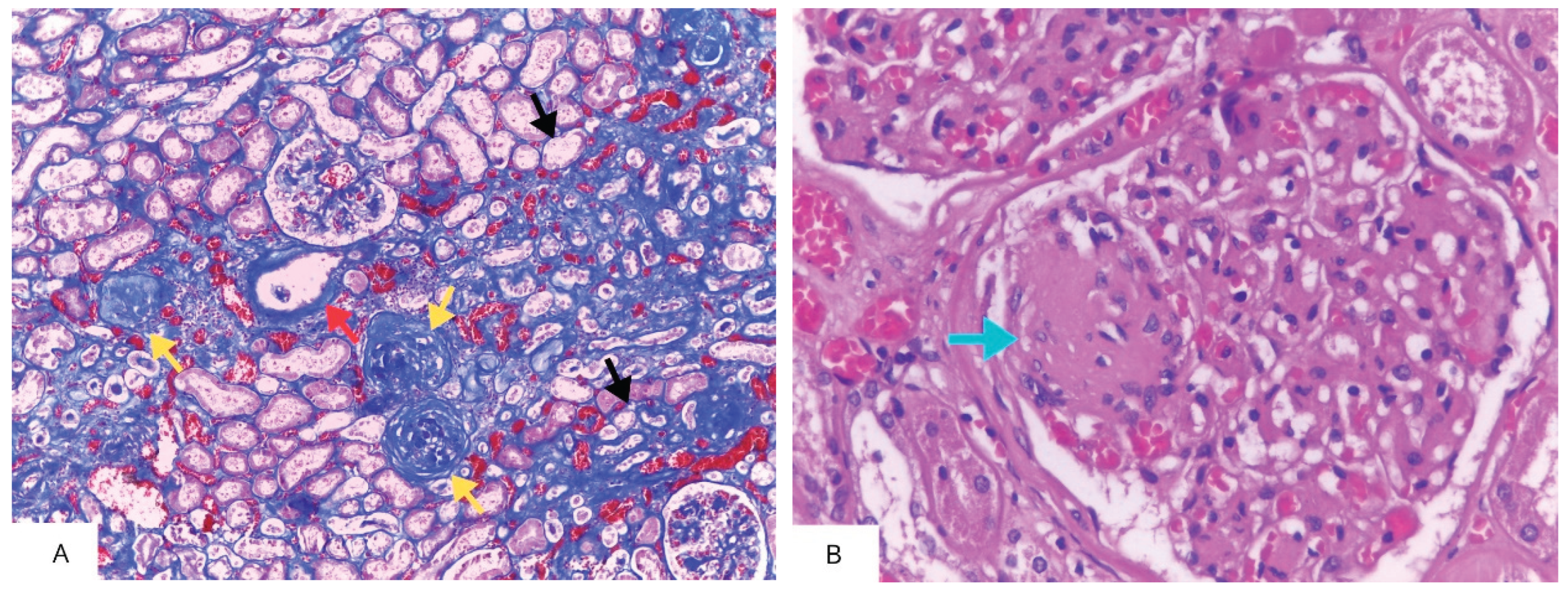

- Lai J, Wang HL, Zhang X, Wang H, Liu X. Pathologic Diagnosis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2022;146:940–6. [CrossRef]

- Yoneda M, Kobayashi T, Iwaki M, Nogami A, Saito S, Nakajima A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Systemic Disease and the Need for Multidisciplinary Care. Gut Liver 2023;17:843–52. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah H, Khalil M, Awada E, Lanza E, Di Ciaula A, Portincasa P. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Assessing metabolic dysfunction, cardiovascular risk factors, and lifestyle habits. Eur J Intern Med 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu A, Huang M, Xi Y, Deng X, Xu K. Orchestration of Gut–Liver-Associated Transcription Factors in MAFLD: From Cross-Organ Interactions to Therapeutic Innovation. Biomedicines 2025;13. [CrossRef]

- Sirota JC, McFann K, Targher G, Chonchol M, Jalal DI. Association between nonalcoholic liver disease and chronic kidney disease: An ultrasound analysis from NHANES 1988-1994. Am J Nephrol 2012;36:466–71. [CrossRef]

- Hydes TJ, Kennedy OJ, Buchanan R, Cuthbertson DJ, Parkes J, Fraser SDS, et al. The impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis on adverse clinical outcomes and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study using the UK Biobank. BMC Med 2023;21. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Deng Y, Wang J, Zhao H, Zhang J, Xie W. The association between NAFLD and risk of chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2021;12:204062232110486. [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi SO, Nagelhout E, Sienko D, Lamarre N, Noshad S, Ding Y, et al. Association of Index and Changes in Fibrosis-4 Score with Outcomes in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis. Gastro Hep Advances 2025:100666. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y, Zhao Q, Gong R. Association between metabolic associated fatty liver disease and chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2017–2018. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 2021;14:1751–61. [CrossRef]

- Sumida Y. Limitations of liver biopsy and non-invasive diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:475. [CrossRef]

- Minichmayr IK, Plan EL, Weber B, Ueckert S. A Model-Based Evaluation of Noninvasive Biomarkers to Reflect Histological Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Scores. Pharm Res 2024. [CrossRef]

- Targher G, Pichiri I, Zoppini G, Trombetta M, Bonora E. Increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with Type 1 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver. Diabetic Medicine 2012;29:220–6. [CrossRef]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Lippi G, Zoppini G, Chonchol M. Relationship between Kidney Function and Liver Histology in Subjects with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010;5:2166–71. [CrossRef]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Lippi G, Day C, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and proliferative/laser-treated retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2008;51:444–50. [CrossRef]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Chonchol M, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Lippi G, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is independently associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2010;53:1341–8. [CrossRef]

- Porrini E, Ruggenenti P, Luis-Lima S, Carrara F, Jiménez A, de Vries APJ, et al. Estimated GFR: time for a critical appraisal. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019;15:177–90. [CrossRef]

- Niizuma S, Nakamura S, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Yoshihara F, Kawano Y. Kidney function and histological damage in autopsy subjects with myocardial infarction. Ren Fail 2011;33:847–52. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Lin S, Wang M, Huang J, Liu S, Wu S, et al. Association between NAFLD and risk of prevalent chronic kidney disease: why there is a difference between east and west? BMC Gastroenterol 2020;20:139. [CrossRef]

- Miller KC, Geyer B, Alexopoulos AS, Moylan CA, Pagidipati N. Disparities in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Prevalence, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Dig Dis Sci 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhao D, Zheng X, Wang L, Xie Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y. Overlap prevalence and interaction effect of cardiometabolic risk factors for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nutrition and Metabolism 2025;22. [CrossRef]

- Webster AC, Nagler E V., Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney Disease. The Lancet 2017;389:1238–52. [CrossRef]

- Pan Z, Alqahtani SA, Eslam M. MAFLD and chronic kidney disease: two sides of the same coin? Hepatol Int 2023;17:519–21. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Mu C, Li K, Luo H, Liu Y, Li Z. Estimating Global Prevalence of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight or Obese Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Public Health 2021;66. [CrossRef]

- Pacifico L, Nobili V, Anania C, Verdecchia P, Chiesa C. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:3082–91. [CrossRef]

- Mitsinikos T, Mrowczynski-Hernandez P, Kohli R. Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Pediatr Clin North Am 2021;68:1309–20. [CrossRef]

- Goyal NP, Xanthakos S, Schwimmer JB. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in children. Gut 2025;74:669–77. [CrossRef]

- Feldstein AE, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Treeprasertsuk S, Benson JT, Enders FB, Angulo P. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: A follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut 2009;58:1538–44. [CrossRef]

- Pacifico L, Bonci E, Andreoli G, Di Martino M, Gallozzi A, De Luca E, et al. The Impact of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease on Renal Function in Children with Overweight/Obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1218. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, El-Shabrawi M, Baur LA, Byrne CD, Targher G, Kehar M, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus on pediatric metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Med 2024;5:797-815.e2. [CrossRef]

- Arab JP, Díaz LA, Rehm J, Im G, Arrese M, Kamath PS, et al. Metabolic Dysfunction and Alcohol-related Liver Disease (MetALD): Position statement by an expert panel on alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Di Ciaula A, Bonfrate L, Krawczyk M, Frühbeck G, Portincasa P. Synergistic and Detrimental Effects of Alcohol Intake on Progression of Liver Steatosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2636. [CrossRef]

- Marti-Aguado D, Calleja JL, Vilar-Gomez E, Iruzubieta P, Rodríguez-Duque JC, Del Barrio M, et al. Low-to-moderate alcohol consumption is associated with increased fibrosis in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Hepatol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dixon W, Corey K, Luther J, Goodman R, Schaefer EA. Prevalence and clinical correlation of cardiometabolic risk factors in alcohol-related liver disease and MetALD. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2024:102492. [CrossRef]

- Zheng T, Wang X, Kamili K, Luo C, Hu Y, Wang D, et al. The relationship between alcohol consumption and chronic kidney disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2024;59:480–8. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Xu J, Liu F, Wang X, Yang H, Li X. Alcohol Drinking and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Damage: A Meta-Analysis of 15 Prospective Cohort Studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2019;43:1360–72. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Friedman SL, Gra-Oramas B, Gonzalez-Fabian L, Villa-Jimenez O, et al. Improvement in liver histology due to lifestyle modification is independently associated with improved kidney function in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:332–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zhang T, Liu Y, Bai S, Jiang J, Zhou H, et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle was associated with an attenuation of the risk of chronic kidney disease from metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease: Results from two prospective cohorts. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 2023;17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Rouillard N, Mao X, Lai R, Cheung R, Sasaki K, et al. Enhanced long-term outcomes with laparoscopic bariatric surgery in patients with severe obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a retrospective cohort study. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2023;0:0–0. [CrossRef]

- Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, Schattenberg JM, Loomba R, Taub R, et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2024;390:497–509. [CrossRef]

- Au K, Yang W. Resmetirom as an important cornerstone of multidisciplinary management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2025;14:290–4. [CrossRef]

- Fan J-G, Xu X-Y, Yang R-X, Nan Y-M, Wei L, Jia J-D, et al. Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Fatty Liver Disease (Version 2024). J Clin Transl Hepatol 2024;12:955–74. [CrossRef]

- Mathur A, Ozkaya E, Rosberger S, Sigel KM, Doucette JT, Bansal MB, et al. Concordance of vibration-controlled transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography for fibrosis staging in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Eur Radiol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ratziu V, Hompesch M, Petitjean M, Serdjebi C, Iyer JS, Parwani A V., et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted digital pathology for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: current status and future directions. J Hepatol 2024;80:335–51. [CrossRef]

- Zerehpooshnesfchi S, Lonardo A, Fan J-G, Elwakil R, Tanwandee T, Altarrah MY, et al. Dual etiology vs. MetALD: how MAFLD and MASLD address liver diseases coexistence. Metabolism and Target Organ Damage 2025;5. [CrossRef]

- Samanta A, Sarma M Sen. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A silent pandemic. World J Hepatol 2024;16:511–6. [CrossRef]

| Authors, year | Study characteristics | Diagnosis of SLD / CKD | Main findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al., 2024 [78] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 8 cohort studies from Asia and the UK, comprising 598,531 patients. Follow-up ranging from 4.6 to 12.9 years. Aim: to compare the incidence of CKD in persons with MAFLD and controls without MAFLD. |

SLD: MAFLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, proteinuria, or urine albumin/creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g. |

MAFLD was associated with a higher incidence of CKD (HR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.24-1.53) adjusted for sex, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking status | 1.Meta-analysis with high heterogeneity (I2 = 95%). 2.Seven of the eight studies were from Asia. 3.No assessment of MAFLD severity at baseline. |

| Agustanti et al., 2023 [14] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 studies (7 cross- sectional and 4 longitudinal) from Asia, Europe, and the USA, comprising 355,886 patients. Follow-up ranging from 4.6 to 6.5 years Aim: to determine the incidence and prevalence of CKD according to the presence and severity of MAFLD at baseline. |

SLD: MAFLD or NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound, transient elastography, or FLI. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or UACR of 30 mg/g or greater or proteinuria (positive dipstick test result of +1 or greater). |

MAFLD was associated with higher prevalence (OR = 1.50, 95% CI 1.02-2.23) and incidence (HR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.18-1.52) of CKD adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, study region, and follow-up duration. Significant liver fibrosis, but not steatosis, was associated with greater likelihood of developing CKD. | 1.Meta-analysis with high heterogeneity (I2: 97.7% for cross-sectional and 84.6% for longitudinal studies). 2.Eexposure group included patients with either NAFLD or MAFLD criteria, leading to possible selection bias. 3.Absence of histological analysis of SLD. |

| Mantovani et al., 2022 [16] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 longitudinal studies from Asia, Europe and the USA, comprising 1.222,032 patients. Median follow-up of 9.7 years. Aim: to determine the incidence of CKD according to the presence and severity of MAFLD at baseline. |

SLD: NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by liver enzymes, blood biomarkers, imaging methods, liver histology or ICD-10 codes. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with or without overt proteinuria. |

NAFLD was associated with higher incidence of CKD (HR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.33-1.54) adjusted for age, sex, obesity, hypertension, diabetes and other conventional CKD risk factors. |

1. The authors suggest a possible association between the severity of NAFLD (especially liver fibrosis) and incident CKD but emphasize that the studies that assessed hepatic fibrosis did not include a control group without NAFLD, resulting in insufficient data for a meta-analysis. 2. Meta-analysis with medium to high heterogeneity (I2 = 60.7%). |

| Musso et al., 2014 [15] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 studies (20 cross-sectional and 13 longitudinal) from Asia, the USA, Europe, and Saudi Arabia, comprising 63,902 patients. Follow-up ranging from 3 to 27 years Aim: to determine the incidence and prevalence of CKD according to the presence and severity of NAFLD at baseline. |

SLD: NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by liver histology, imaging (ultrasound, computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or spectroscopy), biochemistry (elevations in serum liver enzymes). CKD: eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, or proteinuria (UACR, 24-h albumin excretion rate, fresh morning urine dipstick), or other abnormalities due to tubular disorders or structural abnormalities detected by electrolyte or urinary sediment alterations, histology, imaging, or history of kidney transplantation. |

NAFLD was associated with higher prevalence (OR = 2.12, 95% CI 1.69-2.66) and incidence (HR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.65-1.95) of CKD. NASH was associated with higher prevalence (OR = 2.53, 95% CI 1.58-4.05) and incidence (HR = 2.12, 95% CI 1.42-3.17) of CKD than steatosis alone. Advanced liver fibrosis was associated with higher prevalence (OR = 5.20, 95% CI 3.14-8.61) and incidence (HR = 3.29, 95% CI 2.30-4.71) of CKD than non-advanced fibrosis. All findings were adjusted for diabetes status, traditional risk factors for CKD, obesity, and insulin resistance. | 1.Meta-analysis with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 77%). 2.Only 5 studies with biopsy-proven NAFLD, totaling 690 patients, leading to possible small study bias. |

| Sanyal, 2021 [81] | Prospective multicenter cohort study from the USA, including 1,773 patients with NAFLD (with or without fibrosis). Median follow-up of 4 years. Aim: to determine longitudinal outcomes according to the severity of NAFLD. | SDL: NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by liver biopsy. CKD: decrease in eGFR of >40% |

Patients with stage F4 fibrosis had a decrease of more than 40% in the eGFR compared to those with stages F0 to F2 fibrosis (2.98 vs. 0.97 events per 100 person-years; HR = 1.9; 95% CI 1.1-3.4) adjusted for age, race, sex, length of biopsy specimen, and diabetes status. | 1.Limited generalizability (study conducted at tertiary care centers with predominantly White populations. 2. F3 fibrosis was not associated with a decrease in eGFR of >40% when compared to F0-F2 (HR = 0.9; 95%CI 0.6-1.6) |

| Gao et al., 2024 [85] | Retrospective cohort study from China, including 79,540 patients. Median follow-up of 12.9 years. Aim: to determine the incidence of CKD according to the presence, severity, and remission of MAFLD/MASLD |

SLD: MAFLD and MASLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 or positive proteinuria (≥1+). |

MAFLD/MASLD was associated with a higher incidence of CKD (HR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.09-1.16]); risk increased according to severity of steatosis (p <0.001). Even after remission of MAFLD/MASLD, patients with prior moderate to severe hepatic steatosis still had a higher risk of CKD. Adjustments: age, sex, smoking, drinking, exercise, education, income, eGFR at baseline, uric acid, ALT, metabolic dysfunction, use of antihyperglycemic, antihypertensive, and antilipidemic agents. |

Most patients in the study were male (80%). |

| Mori et al., 2024 [83] | Retrospective cohort study from Japan, including 12,138 patients. Follow-up of 10 years. Aim: to determine the incidence of CKD according to SLD status at baseline (MASLD, MetALD, ALD, and SLD without metabolic dysfunction) compared to the incidence of CKD in non-SLD control subjects | SLD: MASLD, MetALD, and ALD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or proteinuria by dipstick. |

The incidence of CKD was higher in individuals with MASLD (HR = 1.20; CI 1.08-1.33) and ALD (HR = 1.41; CI 1.05-1.88), but not MetALD (HR = 1.11; CI 0.90-1.36) when compared to those without SLD. Individuals with SLD without metabolic dysfunction had a lower incidence (HR = 0.61 [0.39-0.96]) than those without SLD. Adjustments: age, sex, baseline eGFR, smoking, diabetes, systemic hypertension, and dyslipidemia. |

Study conducted in a single urban clinic (possibility of selection bias) |

| Liang et al., 2022 [82] | Cohort study from China, including 6,873 patients. Follow-up of 4.6 years. Aim: to compare the incidence of extra-hepatic diseases in persons with MAFLD and controls without MAFLD. |

SLD: NAFLD and MAFLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound. CKD: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or UACR 30 μg/mg or greater. |

MAFLD was associated with a higher incidence of CKD (RR = 1.64; 95% CI 1.39-1.94). Similar associations for NAFLD were observed. Adjustments: age, sex, education, smoking status, and leisure-time exercise. | NAFLD and MAFLD were also associated with an increased incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. |

| Mouzaki et al., 2024 [79] | Prospective multicenter cohort study from the USA, including 1,164 children (age 13 ± 3 years). Median follow-up of 2 years. Aims: to determine the prevalence of hyperfiltration or CKD in children with NAFLD/MASLD and determine links with liver disease severity. |

SLD: MASLD/ NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by biopsy. CKD: Hyperfiltration or eGFR < 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

Significant liver fibrosis was associated with hyperfiltration (OR: 1.45). Progression of renal impairment was not associated with change in liver disease severity. Adjustments: BMI, insulin resistance, hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, age, ethnicity, race, gender, and T2DM. |

1. Most participants were Hispanic. 2. Short follow-up. 3.Study did not include proteinuria as a definition of CKD. |

| Zuo et al., 2021 [80] | Prospective cohort study from China, including 4,042 patients aged 40 years or more. Mean follow-up of 4.4 years. Participants were divided into 4 groups at baseline: 57.4% participants with non-NAFLD, 13.2% with incident NAFLD, 21.6% with persistent NAFLD, and 7.8% with NAFLD resolution. Aim: to assess associations between changes in NALFD status/progression of NAFLD fibrosis and the risk of incident CKD. |

SLD: NAFLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound and NAFLD fibrosis score. CKD: UACR 30 mg/g or greater, or eGFR 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or lower. |

Incident NAFLD was associated with incident CKD (OR = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.003-2.06) compared to non-NAFLD. However, the risk of incident CKD was not significantly different between groups with NAFLD resolution and persistent NAFLD. In the persistent NAFLD group, fibrosis progression was associated with a higher incidence of CKD compared to stable fibrosis (OR = 2.82; 95% CI, 1.22-6.56). Adjustments: baseline and evolution of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. |

1. The study population consisted of more women and older participants from a community-based population. 2. NAFLD and CKD at baseline and follow-up were determined concurrently, precluding the determination of causation. |

| Heo et al., 2024 [84] | Cohort study from Korea, including 214,145 adults with normal kidney function at baseline. Median follow-up: 6.1 years Aim: to compare the incidence of CKD among 5 groups of participants: Without steatosis, NAFLD-only, MASLD-only, both NAFLD and MASLD, and SLD not categorized as NAFLD or MASLD | SLD: NAFLD, and MASLD criteria, diagnosed by ultrasound. CKD: eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria. |

The group meeting both NAFLD and MASLD criteria had the highest risk of CKD (HR = 1.21 [95% CI, 1.04-1.42]). The MASLD-only group had a similar risk (HR = 1.96 [95% CI, 1.44-2.67]), but NAFLD alone was not independently associated with CKD or albuminuria. Adjustments: age, sex, education, smoking history, exercise, alcohol intake, history of coronary artery disease, use of anti-hypertensive medications, and levels of eGFR at baseline. |

Authors suggest that MASLD criteria are better than NAFLD criteria at identifying individuals at high risk of incident CKD or albuminuria. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).