Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Anthropometric and Laboratory Measurements

2.3. Diagnosis of MASLD/MAFLD and Advanced Liver Fibrosis

2.4. Definition of GHF and CKD Progression

- (1)

-

For individuals without hyperfiltration:

- eGFR persistently ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73m² for ≥ 12 months, or

-

At follow-up, eGFR ≤ 89 mL/min/1.73m² with at least one of the following:

- A sustained annual decline in eGFR ≥ 5 mL/min/1.73m² was observed in subsequent follow-ups.

- A reduction of ≥ 30% in eGFR was observed compared with the previous follow-up.

- (2)

-

For individuals with hyperfiltration:

- eGFR persistently ≤ 60 mL/min/1.73m² for ≥ 12 months, or

-

At follow-up, eGFR ≤ 89 mL/min/1.73m² with at least one of the following:

- A sustained annual decline in eGFR of ≥ 5 mL/min/1.73m² was observed in subsequent follow-ups.

- A reduction of ≥ 30% in eGFR was observed compared with the previous follow-up.

- (3)

-

Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR):

- Newly detected UACR ≥ 30 mg/g at follow-up in previously negative patients

- A ≥ 30% increase from baseline.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

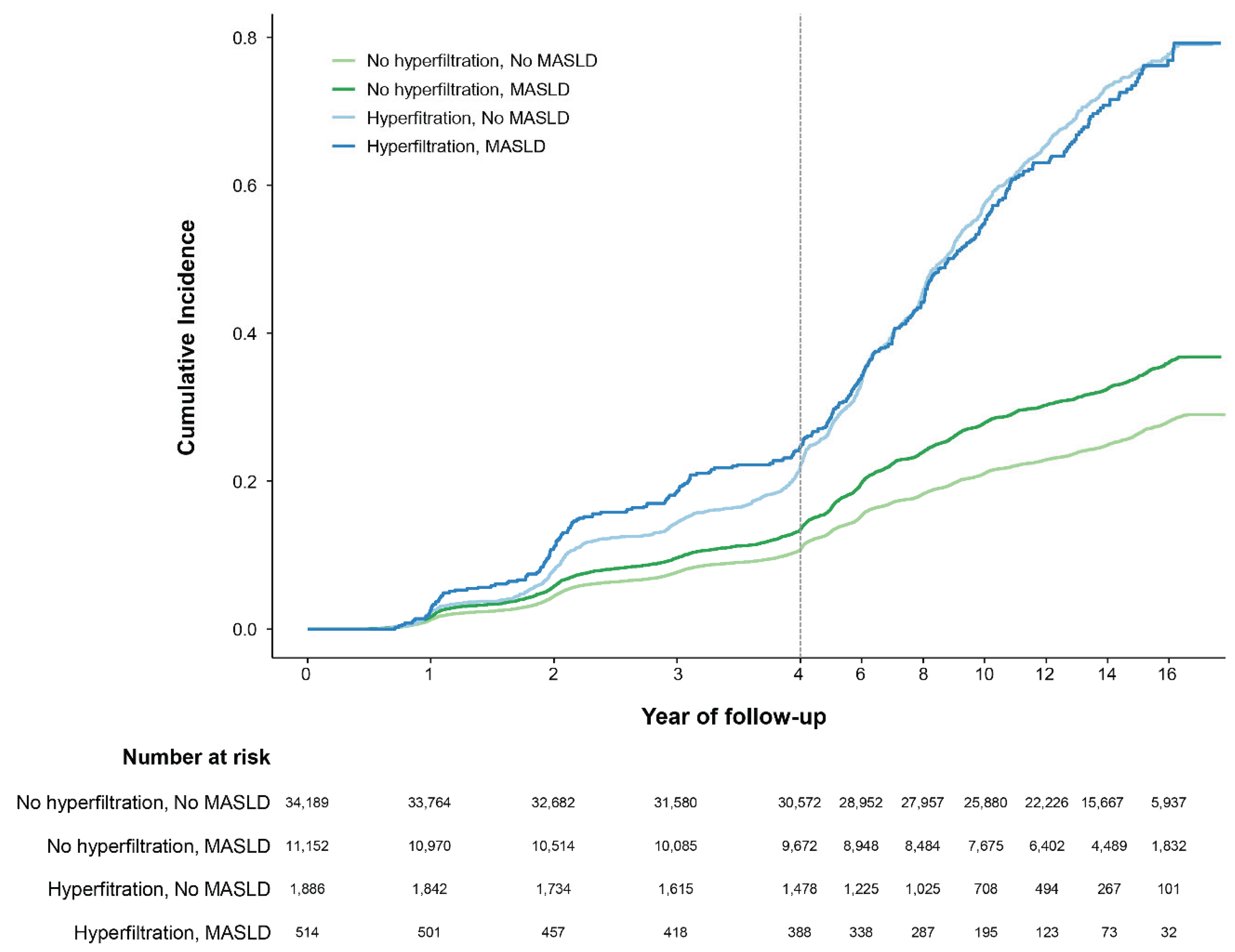

3.2. Primary Outcome

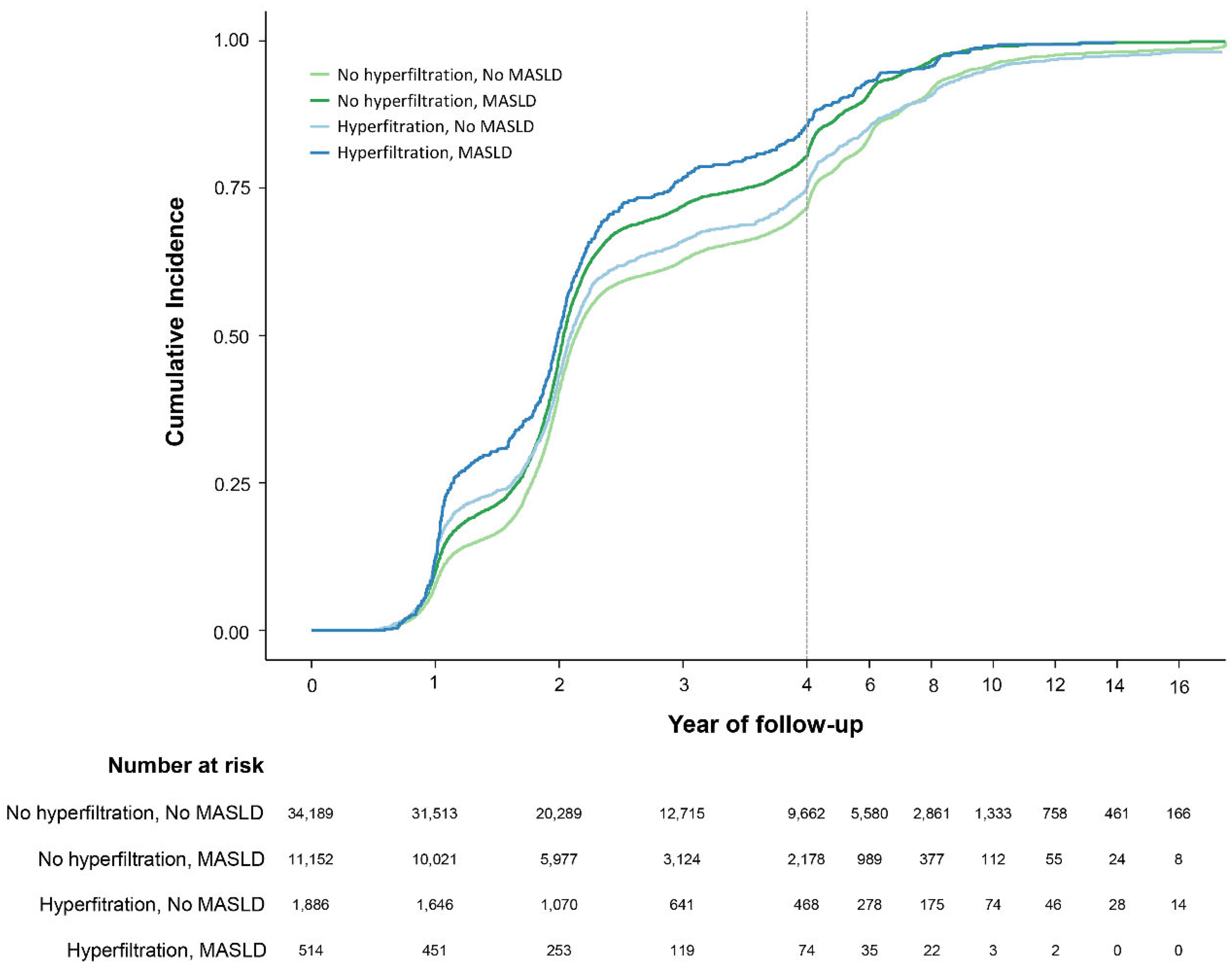

3.3. Secondary Outcome

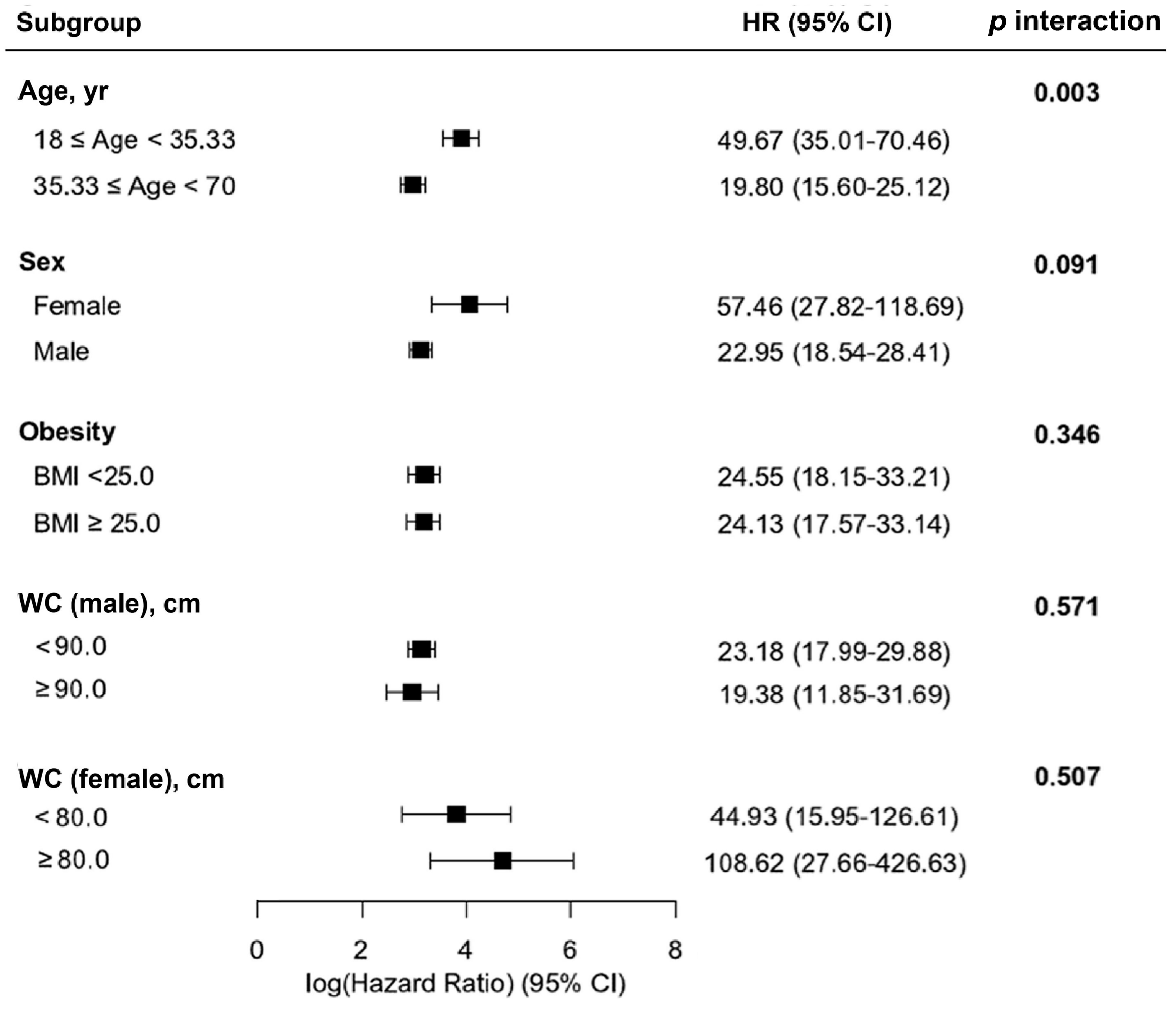

3.4. Other Outcomes and Subgroup Analyses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Work

4.3. Limitations and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MASLD | Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MAFLD | Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| GHF | Glomerular Hyperfiltration |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| WC | Waist Circumference |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| NFS | NAFLD Fibrosis Score |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 Index |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| UACR | Urinary Albumin-Creatinine Ratio |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| LOWESS | Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| PY | Person-Years |

| MASH | Metabolic-Associated Steatohepatitis |

| RAS | Renin-Angiotensin System |

| SGLT2 | Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 |

References

- Yang, A.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Y. Transitioning from NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD: Consistent prevalence and risk factors in a Chinese cohort. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, e154–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.C. No More NAFLD: The Term Is Now MASLD. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2024, 39, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.H.; Jeong, S.J.; Wang, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, H.M.; Cho, J.H.; Ahn, Y.C.; Son, C.G. The Clinical Diagnosis-Based Nationwide Epidemiology of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Liver Disease in Korea. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.C.Z.; Anand, V.V.; Razavi, A.C.; Alebna, P.L.; Muthiah, M.D.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Chew, N.W.S.; Mehta, A. The Global Epidemic of Metabolic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.; Koo, D.J.; Lee, W.Y. Insulin Resistance, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Clinical and Experimental Perspective. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Jung, I.; Moon, S.J.; Kwon, H.; Rhee, E.J.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, W.Y.; Oh, K.W.; Park, S.E. Increased Risk of NAFLD in Adults with Glomerular Hyperfiltration: An 8-Year Cohort Study Based on 147,162 Koreans. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeni, A.; Garbin, M.; Zoncape, M.; Romeo, S.; Cattazzo, F.; Mantovani, A.; Cespiati, A.; Fracanzani, A.L.; Tsochatzis, E.; Sacerdoti, D.; et al. Glomerular Hyperfiltration: A Marker of Fibrosis Severity in Metabolic Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in an Adult Population. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandireddy, R.; Sakthivel, S.; Gupta, P.; Behari, J.; Tripathi, M.; Singh, B.K. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1433857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Estrela, G.R. Editorial: Multi-organ linkage pathophysiology and therapy for NAFLD and NASH. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1418066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, O.W.; Aguirre, D.A.; Casola, G.; Lavine, J.E.; Woenckhaus, M.; Sirlin, C.B. Fatty liver: imaging patterns and pitfalls. Radiographics 2006, 26, 1637–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Chang, Y.; Choi, Y.; Kwon, M.J.; Kim, C.W.; Yun, K.E.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Ahn, J.; et al. Age at menarche and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J.; International Consensus, P. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusi, K.; Isaacs, S.; Barb, D.; Basu, R.; Caprio, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Kashyap, S.; Mechanick, J.I.; Mouzaki, M.; Nadolsky, K.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology Clinical Settings: Co-Sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr. Pract. 2022, 28, 528–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.M.; Kang, M.K.; Moon, J.S.; Park, J.G. Performance of Simple Fibrosis Score in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with and without Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2023, 38, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancioglu, R.; et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease: known knowns and known unknowns. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Inker, L.A.; Matsushita, K.; Greene, T.; Willis, K.; Lewis, E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Cheung, A.K.; Coresh, J. GFR decline as an end point for clinical trials in CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation and the US Food and Drug Administration. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 64, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Coresh, J.; Inker, L.A.; Heerspink, H.L.; Grams, M.E.; Greene, T.; Tighiouart, H.; Matsushita, K.; Ballew, S.H.; et al. Change in Albuminuria and GFR as End Points for Clinical Trials in Early Stages of CKD: A Scientific Workshop Sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation in Collaboration With the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, H.; Araki, S.I.; Kawai, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Shirabe, S.I.; Sugimoto, H.; Minami, M.; Miyazawa, I.; Maegawa, H.; Group, J.S. The Prognosis of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Nonalbuminuric Diabetic Kidney Disease Is Not Always Poor: Implication of the Effects of Coexisting Macrovascular Complications (JDDM 54). Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.M.; Lawler, E.V.; Mackenzie, H.S. The hyperfiltration theory: a paradigm shift in nephrology. Kidney Int. 1996, 49, 1774–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Woollard, J.R.; Wang, S.; Korsmo, M.J.; Ebrahimi, B.; Grande, J.P.; Textor, S.C.; Lerman, A.; Lerman, L.O. Increased glomerular filtration rate in early metabolic syndrome is associated with renal adiposity and microvascular proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011, 301, F1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Song, W.J.; Chen, W.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fan, L.; Li, J. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease-related hepatic fibrosis increases risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 36, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, X.; Tian, X.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; He, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, S. Severity and Remission of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty/Steatotic Liver Disease With Chronic Kidney Disease Occurrence. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Xu, X.; Yang, M.; Xu, W.; Xiang, S.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Hua, F.; Huang, X. Metabolically healthy obesity is associated with higher risk of both hyperfiltration and mildly reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate: the role of serum uric acid in a cross-sectional study. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, S. Redefining glomerular hyperfiltration: pathophysiology, clinical implications, and novel perspectives. Hypertens. Res. 2025, 48, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.S.; Kim, G.H.; Chung, S. Intrarenal Mechanisms of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on Tubuloglomerular Feedback and Natriuresis. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul) 2023, 38, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Rhee, C.M.; Chou, J.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Park, J.; Chen, J.L.; Amin, A.N. The Obesity Paradox in Kidney Disease: How to Reconcile it with Obesity Management. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, I.; Fick-Brosnahan, G.M.; Reed-Gitomer, B.; Schrier, R.W. Glomerular hyperfiltration: definitions, mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012, 8, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total | MASLD | MAFLD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p-Value | No | Yes | p-Value | ||

| Number, n (%) | 47,741 | 36,075 (75.57) | 11,666 (24.43) | 36,571 (76.61) | 11,170 (23.39) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 31,008 (65.0) | 20,504 (56.8) | 10,504 (90.0) | < 0.001 | 20,911 (57.2) | 10,097 (90.4) | < 0.001 |

| Age, years | 35.33 (5.20) | 35.13 (5.13) | 35.95 (5.38) | < 0.001 | 35.14 (5.14) | 35.95 (5.36) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.36 (3.03) | 22.46 (2.59) | 26.17 (2.51) | < 0.001 | 22.45 (2.58) | 26.36 (2.40) | < 0.001 |

| WC, cm | 79.43 (9.27) | 76.51 (8.24) | 87.69 (6.65) | < 0.001 | 76.56 (8.21) | 88.10 (6.47) | < 0.001 |

| FBG, mg/dL | 92.61 (10.71) | 91.27 (9.14) | 96.75 (13.74) | < 0.001 | 91.30 (9.13) | 96.89 (13.91) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.39 (0.31) | 5.36 (0.29) | 5.48 (0.35) | < 0.001 | 5.36 (0.29) | 5.48 (0.35) | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 113.55 (13.10) | 111.82 (12.54) | 118.88 (13.36) | < 0.001 | 111.83 (12.52) | 119.17 (13.40) | < 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73.60 (9.78) | 72.21 (9.34) | 77.90 (9.85) | < 0.001 | 72.22 (9.33) | 78.10 (9.87) | < 0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 24.32 (16.14) | 22.61 (16.79) | 29.59 (12.53) | < 0.001 | 22.66 (16.74) | 29.75 (12.55) | < 0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 27.51 (26.18) | 22.17 (23.05) | 44.03 (28.29) | < 0.001 | 22.32 (23.16) | 44.49 (28.23) | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 126.53 (81.39) | 107.63 (59.91) | 184.99 (107.20) | < 0.001 | 108.44 (60.65) | 185.76 (108.14) | < 0.001 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 54.55 (11.93) | 56.41 (12.15) | 48.81 (9.12) | < 0.001 | 56.33 (12.13) | 48.73 (9.10) | < 0.001 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 1.04 (0.16) | 1.01 (0.16) | 1.12 (0.14) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (0.16) | 1.12 (0.14) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 85.46 (10.84) | 86.17 (10.83) | 83.24 (10.55) | < 0.001 | 86.16 (10.83) | 83.16 (10.54) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol intake, g/day | 6.38 (7.26) | 5.82 (7.12) | 8.09 (7.42) | < 0.001 | 5.83 (7.12) | 8.15 (7.40) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| never or ex- | 33,770 (72.2) | 26,709 (75.6) | 7,061 (61.6) | 27,047 (75.5) | 6,723 (61.3) | ||

| current | 13,023 (27.8) | 8,627 (24.4) | 4,396 (38.4) | 8,780 (24.5) | 4,243 (38.7) | ||

| Regular exercise, n (%) | 6,249 (13.1) | 4,944 (13.7) | 1,305 (11.2) | < 0.001 | 4,982 (13.6) | 1,267 (11.3) | < 0.001 |

| FIB-4 | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.05) | < 0.001 | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.05) | < 0.001 |

| NFS | -3.40 (0.84) | -3.34 (0.84) | -3.56 (0.82) | < 0.001 | -3.35 (0.85) | -3.55 (0.81) | < 0.001 |

| Subject groups | PY | Number | Events | IR per 10000 PY | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| GHF (-) | |||||||

| MASLD (-) | 414,579.00 | 34,189.00 | 8,781.00 | 211.81 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| MASLD (+) | 127,389.55 | 11,152.00 | 3,710.00 | 291.23 | 1.36 (1.31-1.42) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) |

| GHF (+) | |||||||

| MASLD (-) | 4,286.60 | 514.00 | 349.00 | 814.16 | 3.62 (3.26-4.03) | 2.79 (2.50-3.10) | 2.56 (2.30-2.86) |

| MASLD (+) | 16,065.92 | 1,886.00 | 1,334.00 | 830.33 | 3.69 (3.48-3.91) | 3.81 (3.60-4.04) | 3.88 (3.66-4.11) |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 296,683.91 | 291,268.91 | 285,665.46 | ||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 296,706.59 | 291,306.70 | 285,733.34 | ||||

| GHF (-) | |||||||

| MAFLD (-) | 420,059.90 | 34,664.00 | 8,916.00 | 212.26 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| MAFLD (+) | 121,908.64 | 10,677.00 | 3,575.00 | 293.25 | 1.37 (1.32-1.43) | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) |

| GHF (+) | |||||||

| MAFLD (-) | 4,096.67 | 493.00 | 336.00 | 820.18 | 3.64 (3.26-4.06) | 2.79 (2.50-3.12) | 2.55 (2.28-2.85) |

| MAFLD (+) | 16,255.85 | 1,907.00 | 1,347.00 | 828.62 | 3.67 (3.47-3.89) | 3.81 (3.59-4.03) | 3.87 (3.65-4.10) |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 296,682.56 | 291,268.64 | 285,666.93 | ||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 296,705.24 | 291,306.43 | 285,734.81 | ||||

| Subject groups | PY | Number | Events | IR per 10000 PY | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| MASLD (-) | |||||||

| GHF (-) | 118,084.48 | 34,189.00 | 33,576.00 | 2,843.39 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| GHF (+) | 6,207.03 | 1,886.00 | 1,829.00 | 2,946.66 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | 1.07 (1.02-1.12) | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) |

| MASLD (+) | |||||||

| GHF (-) | 30,980.77 | 11,152.00 | 11,112.00 | 3,586.74 | 1.30 (1.27-1.33) | 1.26 (1.23-1.29) | 1.20 (1.17-1.23) |

| GHF (+) | 1,299.16 | 514.00 | 510.00 | 3,925.62 | 1.45 (1.33-1.58) | 1.42 (1.30-1.55) | 1.36 (1.24-1.48) |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 924,208.42 | 922,796.69 | 902,578.24 | ||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 924,234.69 | 922,840.48 | 902,656.88 | ||||

| MAFLD (-) | |||||||

| GHF (-) | 119,479.10 | 34,664.00 | 34,049.00 | 2,849.79 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| GHF (+) | 6,271.58 | 1,907.00 | 1,849.00 | 2,948.22 | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | 1.07 (1.02-1.12) | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) |

| MAFLD (+) | |||||||

| GHF (-) | 29,586.15 | 10,677.00 | 10,639.00 | 3,595.94 | 1.30 (1.27-1.33) | 1.26 (1.23-1.29) | 1.20 (1.17-1.23) |

| GHF (+) | 1,234.61 | 493.00 | 490.00 | 3,968.86 | 1.47 (1.35-1.61) | 1.44 (1.31-1.57) | 1.37 (1.25-1.50) |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 924,221.65 | 922,804.07 | 902,590.78 | ||||

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 924,247.92 | 922,847.86 | 902,669.42 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).