1. Introduction

Impaired kidney function has been consistently linked to an elevated long-term risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), with cardiovascular mortality being the leading cause of death among individuals with kidney disease [

1]. Cardiovascular complications, particularly coronary artery disease (CAD), are among the most prevalent outcomes observed in this population [

2,

3]. The mechanisms underlying this association are multifactorial and may involve both direct effects such as volume overload, hypertension, vascular calcification, and accelerated atherosclerosis that contribute to structural and functional cardiac deterioration, as well as indirect effects through the exacerbation of traditional cardiovascular risk factors [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

While overt cardiovascular events have been extensively studied in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), less is known about the early and often silent manifestations of cardiac injury. Subclinical myocardial injury (SCMI), characterized by subclinical ischemic myocardial damage in the absence of overt symptoms, is a significant predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including CVD mortality [

9,

10]. SCMI can be identified using the Cardiac Infarction/Injury Score (CIIS), a validated electrocardiographic marker of myocardial injury that has been widely applied in epidemiological studies [

10,

11].

Whether impaired kidney function is associated with SCMI is currently unknow, and the combined impact of of both conditions on CV mortality has not been well studied. We addressed these questions using data from the United States Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

NHANES III is a program designed to assess health and nutritional status among U.S. adults and children living in the community. It is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES III was carried out between 1988 and 1994. All participants gave written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) institutional review board. Further information on the survey’s design, methodology, and data availability has been documented in prior publications [

12,

13].

For the purpose of this analysis, we included NHANES III participants with available ECG data at baseline. By design, only NHANES-III participants aged 40 years or older underwent ECG recording. We excluded those with prior CVD (prior myocardial infarction, heart failure or stroke) and those with missing key variables needed for analysis, those with eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m² and those with major ECG abnormalities. After all exclusions, 6057 participants were included in the analysis.

2.2. Ascertainment of Kidney Function

During NHANES-III assessments either in house or mobile units, blood samples were collected via venipuncture by phlebotomist and samples were analyzed for biomarkers including creatinine level. Renal function was assessed using eGFR, which was calculated from serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [

14]. Participants were stratified into two groups: eGFR ≥ 45 mL/min/1.73 m² and eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m².

2.3. Defining Subclinical Myocardial Injury (SCMI)

Electrocardiographic Cardiac Infarction/Injury Score (CIIS) score was used to define SCMI [

10,

15,

16]. In NHANES-III, a resting 12-lead ECG was obtained using a Marquette MAC 12 electrocardiograph (Marquette Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) during a physical examination conducted within a mobile examination center. The digital signals of the ECG tracings were sent to the Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center (EPICARE) of Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, NC) for central processing. ECGs underwent visual inspection by skilled technicians before being automatically processed using GE 12-SL program (Marquette Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin).

The CIIS is a weighted scoring system designed to assess the likelihood of myocardial injury or ischemia based on quantitative ECG features. It incorporates a total of 15 components, including 11 discrete and 4 continuous ECG variables, derived from standard 12-lead ECGs. These elements capture abnormalities in Q waves, R waves, T waves, and the ST segment, and together provide a risk-stratified assessment of cardiac injury. The CIIS is structured to allow for both manual interpretation and automated processing, making it suitable for use in large population-based studies [

11].

In NHANES III dataset, CIIS values were initially stored after being multiplied by 10 to avoid the use of decimal points in the database. For the purpose of this analysis, the values were converted back to their original scale by dividing by 10 [

5]. In accordance with established definitions in the literature, a CIIS score of 10 or greater was used to define the presence of SCMI) [

5,

10,

15,

16].

2.4. Ascertainment of Cardiovascular Mortality

The primary outcome was CV mortality, determined through linkage to the National Death Index with follow-up through December 31, 2015. CV deaths were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes corresponding to underlying causes of death.

2.5. Other Variables

Demographics (age, sex, race), and smoking status, education level, family income and medication intake were self-reported during an in-home interview. Physical activity was assessed based on the frequency of leisure time activity and included information on types of activity, frequency, and level of activity. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as height over square root of weight using data from physical examination conducted at a mobile examination center. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured while seated and up to three measurements were averaged. Diabetes mellites was defined as fasting blood glucose levels ≥126 mg/dl or the use of glucose-lowering medications. Total cholesterol, creatinine and glucose, and other components in the metabolic panel using laboratory procedures as reported by the National Center for Health Statistics [

13].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

We compared participant characteristics stratified by presence of SCMI using Chi-square test for categorical variables and student T-test for continuous variables. Categorical variables presented as numbers and percentage while continuous variables presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the cross-sectional association between levels of eGFR and the presence SCMI. We modeled eGFR as both categorical (eGFR ≥ 45 vs. < 45) mL/min/1.73 m² and as a continuous variable (per 1 SD decrease). Models were adjusted as follows: Model 1 adjusted for sociodemographic variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. Model 2 was further adjusted for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, BMI, lipid-lowering medication use, smoking status, and physical activity.

We calculated CV mortality incidence rates per 1000-person years stratified by eGFR levels and SCMI status. Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard models were used to assess the associations of low levels of eGFR and SCMI, separately and in combination with CV mortality. Model 1 adjusted for sociodemographic variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. Model 2 was further adjusted for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, BMI, lipid-lowering medication use, smoking status, and physical activity.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A two-sided α of 0.05 was used for hypothesis testing.

3. Results

This analysis included 6057 participants (mean age 57.0±13.0 years); 54.4% women, 50% non-Hispanic whites). A total of 1297 (21.4%) individuals had prevalent SCMI at baseline. Participants with SCMI tended to be older, with higher prevalence diabetes, and higher levels of systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and BMI (

Table 1).

In logistic regression models adjusted for sociodemographic and CV risk factors, low eGFR (< 45 mL/min/1.73 m²) was not associated with increased risk of SCMI compared to those with eGFR ≥ 45 mL/min/1.73 m². Similar results were obtained when eGFR was used in the model per 1-SD decrease (

Table 2).

After a median follow-up of 18.2 years, 690 (11.4%) participants experienced CV mortality. In Cox proportional hazards models, participants with SCMI had a 43% higher risk of CV death compared to those without SCMI, a finding that remained significant in fully adjusted models

. (

Table 3). Similarly, and in a separate analysis, participants with low eGFR (eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m²) had a higher CV mortality rate compared to those with eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m² (32% vs. 10%) with an increased risk of CV mortality by 56% %) in fully adjusted models accounting for sociodemographic and CV risk factors, (

Table 4). Modeling eGFR as a continuous variable, each 1-SD decrease in eGFR was associated with a 14% higher risk of CV mortality in a linear pattern, supporting a dose-response relationship.

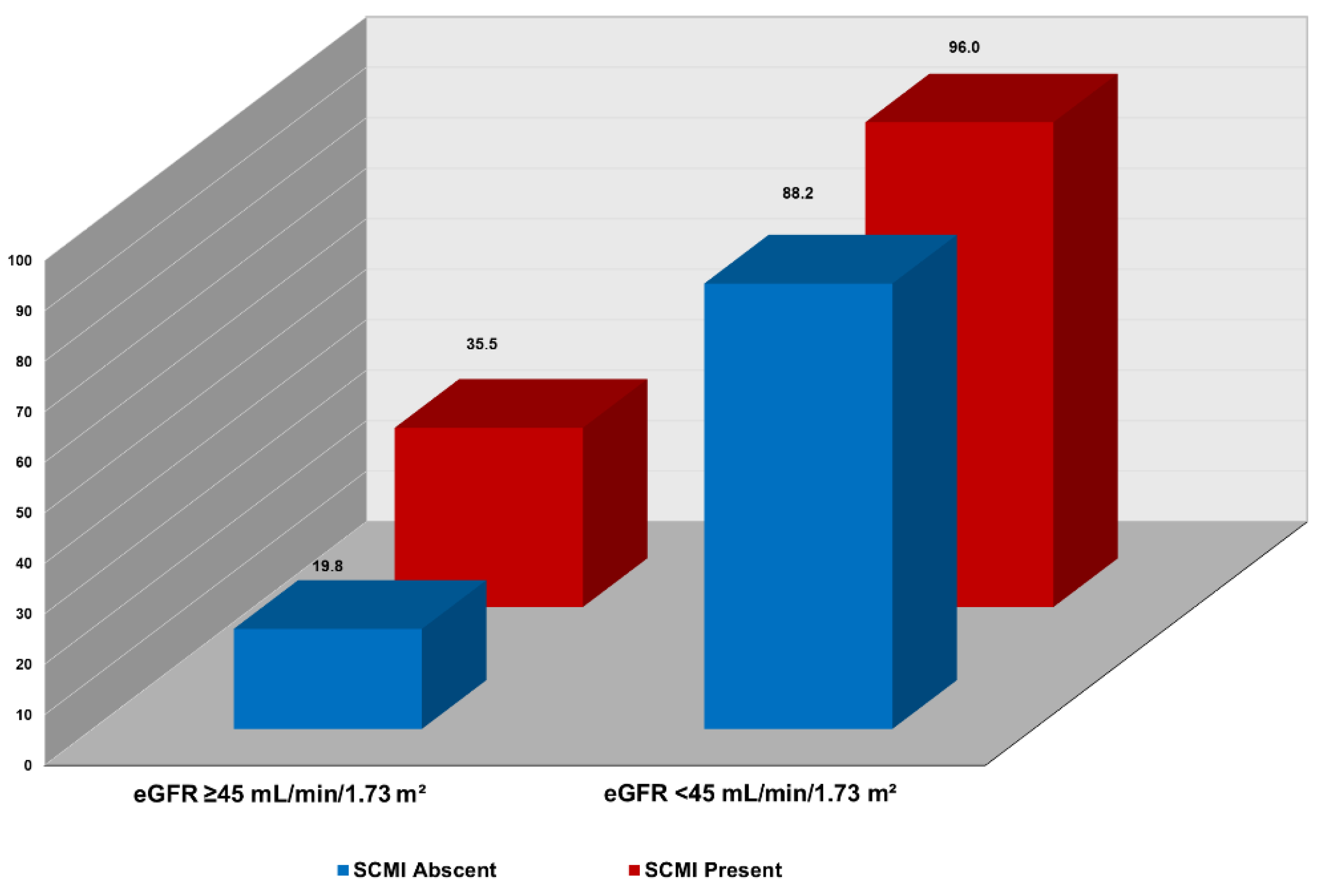

In joint analysis, incremental, stepwise increase in CV mortality was observed across combinations of SCMI and eGFR levels. As shown in

Figure 1, the highest CV mortality rate per 1000-person-year occurred in participants with both eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m²and SCMI. In contrast, the lowest CV mortality rate was in those with eGFR

>45 mL/min/1.73 m²and and without SCMI. Also, in multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, participants with both SCMI and eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m² had more than double the risk of CV death (HR 2.36; 95% CI, 1.65–3.36; p < 0.001) than those without SCMI and with eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m². Other combinations of eGFR eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m² and presence of SCMI status were also associated with increased risk of CV mortality compared eGFR eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m² and absence of SCMI, but the risk was lower than that of concomitant presence of both conditions (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

CV mortality remains the primary cause of death globally and accounts for excess mortality among individuals with impaired kidney function. In this nationally representative analysis, both reduced eGFR and the presence of SCMI were independently associated with increased risk of CV mortality. Importantly, when both conditions coexisted, the risk of CV death nearly doubled, suggesting a synergistic relationship beyond their individual contributions. Despite their shared impact on CV mortality, baseline lower levels of eGFR were not associated with the presence of SCMI. The lack of association between eGFR and SCMI suggests that their synergistic contribution to the risk of CVD is through different pathways.

While the relationship between poor kidney function and adverse cardiovascular outcomes is well established and generally progresses linearly with CKD stage, our findings showed no significant association between lower levels of eGFR and increased prevalence of SCMI. It is important to note that prior literature has predominantly focused on overt CVD outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], while subclinical disease processes such as SCMI is mainly underexplored. Differences in the associations of CKD with overt CVD versus SCMI probably reflect differences in pathophysiological pathways and disease timelines. While reduced eGFR contributes to cardiac remodeling through mechanisms such as volume overload, arterial stiffness, mineral dysregulation, and systemic inflammation, SCMI likely results from focal ischemic injury or microvascular compromise, processes that may not directly correlate with kidney disease biomarkers [

17]. Additionally, individuals with low eGFR are often targeted for intensive cardiovascular monitoring and early preventive therapy, which may attenuate or delay the development of detectable SCMI, potentially masking any direct relationship [

18].

Some reports have shown that subclinical cardiovascular disease, defined as elevated cardiac biomarkers, was associated with a significantly faster rate of kidney function decline. This raises the possibility of bidirectional or reversed causality, where SCMI contributes to renal dysfunction, rather than the other way around, and provide evidence that structural and functional cardiac changes may adversely affect kidney function [

19,

20]. Such complexity reinforces the need to better understand the temporal and mechanistic links between subclinical cardiac diseases and kidney function.

Our finding of significant association between reduced eGFR CV mortality aligns with prior studies demonstrating the prognostic importance of kidney dysfunction in CV outcomes. In a retrospective study by Huang et al., eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m² had approximately a 70% higher risk of CV mortality compared to individuals with preserved kidney function [

23]. Also, the Framingham Heart Study has demonstrated nearly 40–110% increase in CV mortality even in those with mildly reduced eGFR (60–89 mL/min/1.73 m²) [

24]. These findings emphasize the broad predictive value of renal function markers across clinical and subclinical stages [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The possible mechanisms by which lower eGFR contributes to CV risk include arterial stiffness, widened pulse pressure, impaired coronary perfusion, and left ventricular hypertrophy [

21,

22]. These changes promote myocardial strain, ischemia, and arrhythmogenic remodeling, all of which elevate long-term risk for cardiovascular events.

Our observed association of SCMI with increased CV mortality was also consistent with previous literature [

9,

10,

15]. SCMI reflects a state of chronic, subclinical myocardial injury, often driven by microvascular dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, or autonomic imbalance. The pathophysiological basis linking SCMI to CV mortality may involve several interrelated mechanisms including the cumulative myocardial damage due to repeated silent ischemia or underlying structural abnormalities such as fibrosis and ventricular remodeling [

25]. These alterations can impair myocardial function, reduce contractile reserve, and promote electrical instability, increasing the risk for worsening CVD and mortality [

26,

27]. SCMI may also reflect systemic atherosclerotic burden and autonomic dysregulation, both of which are independently associated with adverse CV outcomes [

28,

29].

While both eGFR and SCMI were independently linked to mortality, a notable finding in our analysis was the synergistic effect; individuals with both reduced eGFR and concurrent SCMI faced nearly double the risk of CV mortality compared to those with neither condition. This excess risk likely reflects both shared mechanisms such as systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and hemodynamic stress and distinct pathological pathways specific to each condition. SCMI may contribute additional ischemic burden and structural remodeling beyond that already imposed by kidney disease.

Taken together, our findings emphasize the value of SCMI as a clinically meaningful marker of cardiovascular vulnerability in patients with impaired kidney function. Incorporating SCMI assessment using ECG-based scores may enhance cardiovascular risk stratification in this population. Given its low cost, broad availability, and non-invasive nature, the electrocardiogram presents a practical method for identifying SCMI in individuals without overt heart disease. In the context of escalating healthcare costs, screening for subclinical cardiovascular disease markers such as SCMI may offer a cost-effective approach for detecting high-risk individuals. Future research should determine whether early identification and management of SCMI can lower cardiovascular mortality in individuals with CKD.

5. Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, kidney function was assessed using a single eGFR measurement, which may not fully capture long-term renal function or reflect dynamic changes over time. Incorporating imaging modalities or additional biomarkers such as albuminuria or cystatin C could provide a more comprehensive assessment of kidney health. Second, SCMI was determined based on a single ECG. While this may limit temporal resolution, we utilized the CIIS, a well-validated scoring system that has demonstrated both diagnostic accuracy and prognostic relevance in detecting subclinical myocardial injury. Lastly, although the models were adjusted for a wide range of sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors, residual confounding due to unmeasured variables cannot be entirely excluded. Despite these limitations, key strengths of the study include the use of a large, diverse, nationally representative sample and the application of validated methods for outcome and exposure assessment.

6. Conclusions

In this analysis of NHANES III participants, both reduced eGFR and the presence of SCMI were independently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. When both conditions coexisted, the risk of CV death was nearly doubled, indicating a synergistic effect that amplifies risk beyond what would be expected from either condition alone. These findings highlight SCMI as a potentially valuable marker for identifying individuals at a higher cardiovascular risk, particularly in the setting of impaired kidney function. Incorporating SCMI into routine risk assessment may enhance the early identification of high-risk patients and support more targeted prevention strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EZS,MM.; Methodology, EZS,MEM,RK.; Software, RK.; Validation, EZS,RK,AS.; Formal Analysis, RK.; Investigation, RK,EZS,AS.; Resources, RK.; Data Curation, RK.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, AS,MAM,MAA; Writing AS,MAM,MAA Review & Editing, AS,MEM,TAZ.; Visualization, RK.; Supervision, MEM,EZS.

Funding

No funds: grants, or other support was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional ethical review and approval were waived for this study as data used were de-identified and publicly available.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

There were no further contributions to this project beyond those of the listed authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vondenhoff, S.; Schunk, S.J.; Noels, H. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Erhöhtes kardiovaskuläres Risiko bei Patienten mit chronischer Niereninsuffizienz. Herz 2024, 49, 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Sarnak, M.; Amann, K.; Bangalore, S.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1823–1838. [CrossRef]

- Vashistha, V.; Lee, M.; Wu, Y.L.; Kaur, S.; Ovbiagele, B. Low glomerular filtration rate and risk of myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 223, 401–409. [CrossRef]

- Mayne, K.J.; Lees, J.S.; Mark, P.B. Cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease. Medicine 2023, 51, 190–195. [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as cardiovascular risk factor in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [CrossRef]

- Noels, H.; van der Vorst, E.P.C.; Rubin, S.; Emmett, A.; Marx, N.; Tomaszewski, M.; Jankowski, J. Renal–cardiac crosstalk in the pathogenesis and progression of heart failure. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 1306–1334. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Mukku, V.K.; Ahmad, M. Coronary artery disease in patients with chronic kidney disease: A clinical update. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2013, 9, 331–339. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.J.; Vassalotti, J.A.; Wang, C.; et al. Who should be targeted for CKD screening? Impact of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53(Suppl. 3), S71–S77. [CrossRef]

- van Domburg, R.T.; Klootwijk, P.; Deckers, J.W.; van Bergen, P.F.; Jonker, J.J.; Simoons, M.L. The cardiac infarction injury score as a predictor for long-term mortality in survivors of a myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 1998, 19, 1034–1041. [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, W.T.; Shah, A.J.; Efird, J.T.; Rautaharju, P.M.; Soliman, E.Z. Subclinical myocardial injury identified by cardiac infarction/injury score and the risk of mortality in men and women free of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 1018–1023. [CrossRef]

- Rautaharju, P.M.; Warren, J.W.; Jain, U.; Wolf, H.K.; Nielsen, C.L. Cardiac infarction injury score: An electrocardiographic coding scheme for ischemic heart disease. Circulation 1981, 64, 249–256. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Plan and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Series 1: Programs and Collection Procedures. Vital and Health Statistics, No. 32; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 1994.

- Thomas, A.; Belsky, D.W.; Gu, Y. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and biological aging in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999–2018. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 1535–1542. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Robyak, K.; Zhu, Y. The CKD-EPI 2021 equation and other creatinine-based race-independent eGFR equations in chronic kidney disease diagnosis and staging. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2023, 8, 952–961. [CrossRef]

- Chebrolu, S.; Kazibwe, R.; Soliman, E.Z. Association between family income, subclinical myocardial injury, and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Clin. Cardiol. 2024, 47, e70036. [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, N.S.; Sobih, M.H.; Soliman, M.Z.; Mostafa, M.A.; Kazibwe, R.; Soliman, E.Z. Association between atherogenic dyslipidemia and subclinical myocardial injury in the general population. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4946. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Kon, V. Mechanisms for increased cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2009, 18, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.P.; Ho, J.E.; Joseph, J.J.; Kernan, W.N.; Khera, A.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lekavich, C.L.; Lewis, E.F.; Lo, K.B.; Ozkan, B.; Palaniappan, L.P.; Patel, S.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Sperling, L.S.; Virani, S.S.; Wright, J.T.; Singh, R.R.; Elkind, M.S.V.; American Heart Association. Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic health: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1606–1635. [CrossRef]

- Shlipak, M.G.; Katz, R.; Kestenbaum, B.; Fried, L.F.; Siscovick, D.; Sarnak, M.J. Clinical and subclinical cardiovascular disease and kidney function decline in the elderly. Atherosclerosis 2009, 204, 298–303. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Shlipak, M.G.; Katz, R.; et al. Subclinical cardiac abnormalities and kidney function decline: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 1137–1144. [CrossRef]

- Hallan, S.; Astor, B.; Romundstad, S.; Aasarød, K.; Kvenild, K.; Coresh, J. Association of kidney function and albuminuria with cardiovascular mortality in older vs younger individuals: The HUNT II study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 2490–2496. [CrossRef]

- Di Lullo, L.; Gorini, A.; Russo, D.; Santoboni, A.; Ronco, C. Left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease patients: From pathophysiology to treatment. Cardiorenal Med. 2015, 5, 254–266. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Hsu, Y.L.; Chuang, Y.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Chan, T.C. Association between renal function and cardiovascular mortality: A retrospective cohort study of elderly from health check-up. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049307. [CrossRef]

- Ataklte, F.; Song, R.J.; Upadhyay, A.; Musa Yola, I.; Vasan, R.S.; Xanthakis, V. Association of mildly reduced kidney function with cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020301. [CrossRef]

- Schirone, L.; Forte, M.; D’Ambrosio, L.; et al. An overview of the molecular mechanisms associated with myocardial ischemic injury: State of the art and translational perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 1165. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Matsushita, K.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Hoogeveen, R.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E. Chronic hyperglycemia and subclinical myocardial injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Graham, E.L.; Douglas, J.A.; Jack, K.; Conner, M.J.; Arena, R.; Chaudhry, S. Subclinical cardiac dysfunction is associated with reduced cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiometabolic risk factors in firefighters. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 752–760. [CrossRef]

- Hadaya, J.; Ardell, J.L. Autonomic modulation for cardiovascular disease. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 617459. [CrossRef]

- Yiu, K.H.; Zhao, C.T.; Chen, Y.; et al. Association of subclinical myocardial injury with arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2013, 12, 94. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).