1. Introduction

Atrial cardiopathy is an emerging concept entailing any atrial structural, contractile, electrophysiological or functional changes predisposing to adverse outcomes, including stroke, heart failure, and mortality, even in the absence of clinical arrythmia such as atrial fibrillation (AF) [

1,

2]. With the absence of therapeutic modalities directed towards atrial cardiopathy, identifying conditions that contribute to its development and modify its associations with outcomes is crucial.

Consistent evidence indicates that renal impairment contributes to augmented long-term CVD risk, with cardiovascular mortality remains the principal cause of death in this population [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Beyond its established links to coronary heart disease and heart failure, reduced kidney function may predispose to atrial remodeling and AF [

7,

8,

9]. This is plausible as kidney disease , even at early stages can lead to activation of neurohormonal systems, volume overload, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation, which can promote atrial enlargement, scarring, and electrical abnormalities [

10,

11,

12]. Despite this, less is known about whether reduced renal function predisposes to atrial cardiopathy and whether their co-occurrence amplifies the risk of mortality in the general population.

We hypothesize that reduced eGFR is associated with increased risk of atrial cardiopathy, and that both conditions, whether independent or coexistent, increase the risk of mortality in the general population. Therefore, we investigated the associations of reduced eGFR with risk of atrial cardiopathy, as well as their independent and combined impact on all-cause mortality, using data from the United States Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).

2. Methods and Materials

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing, nationally representative survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to assess health and disease patterns among the non-institutionalized U.S. population. NHANES-III was conducted between 1988 and 1994 with approval from the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. Detailed descriptions of the study design and methodology have been published previously [

11]. By study design, only NHANES-III participants aged ≥40 years underwent electrocardiogram (ECG) recording. For the present analysis, we excluded individuals with missing ECG data, non-sinus rhythm, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <15 mL/min/1.73 m

2.

Sociodemographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, education, family income, and medication use) was obtained through structured in-home interviews. Physical activity was assessed based on frequency and type of leisure-time activities. Height and weight were measured at mobile examination centers and used to calculate body mass index (BMI; kg/m2). Blood pressure was measured up to three times in the seated position and mean systolic and diastolic values were recorded. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or use of glucose-lowering medication. Laboratory assays conducted by NCHS included fasting glucose, total cholesterol, and serum creatinine, among other metabolic measures.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture during home visits or at mobile examination centers. Renal function was assessed using eGFR, calculated from serum creatinine with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. Participants were stratified into two categories: eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Atrial cardiopathy was defined by the presence of at least one of the following abnormalities on resting 12-lead ECGs: abnormal P-wave axis (outside 0–75°), deep terminal negativity in V1 (<100 µV), or prolonged P-wave duration in lead II (>120 ms). ECGs were recorded using a Marquette MAC 12 electrocardiograph (Marquette Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) during mobile examination center assessments [

12,

13]. Digital ECG signals were transmitted to the Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center (EPICARE) at Wake Forest University School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, NC) for central processing. All ECGs were visually inspected by trained technicians and then automatically analyzed using the GE 12-SL program (Marquette Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI).

All-cause mortality was determined through linkage with the National Death Index, with follow-up through December 31, 2015.

Statistical analysis:

We compared participant characteristics by presence of atrial cardiopathy using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages, and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the cross-sectional association between eGFR and atrial cardiopathy. eGFR was modeled both categorically (≥45 vs. <45 mL/min/1.73 m2) and continuously (per 1-SD decrease). Two models were constructed: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and income; Model 2 included Model 1 covariates plus prior cardiovascular disease, smoking status, diabetes, total cholesterol, lipid-lowering medication use, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, and antihypertensive medication use.

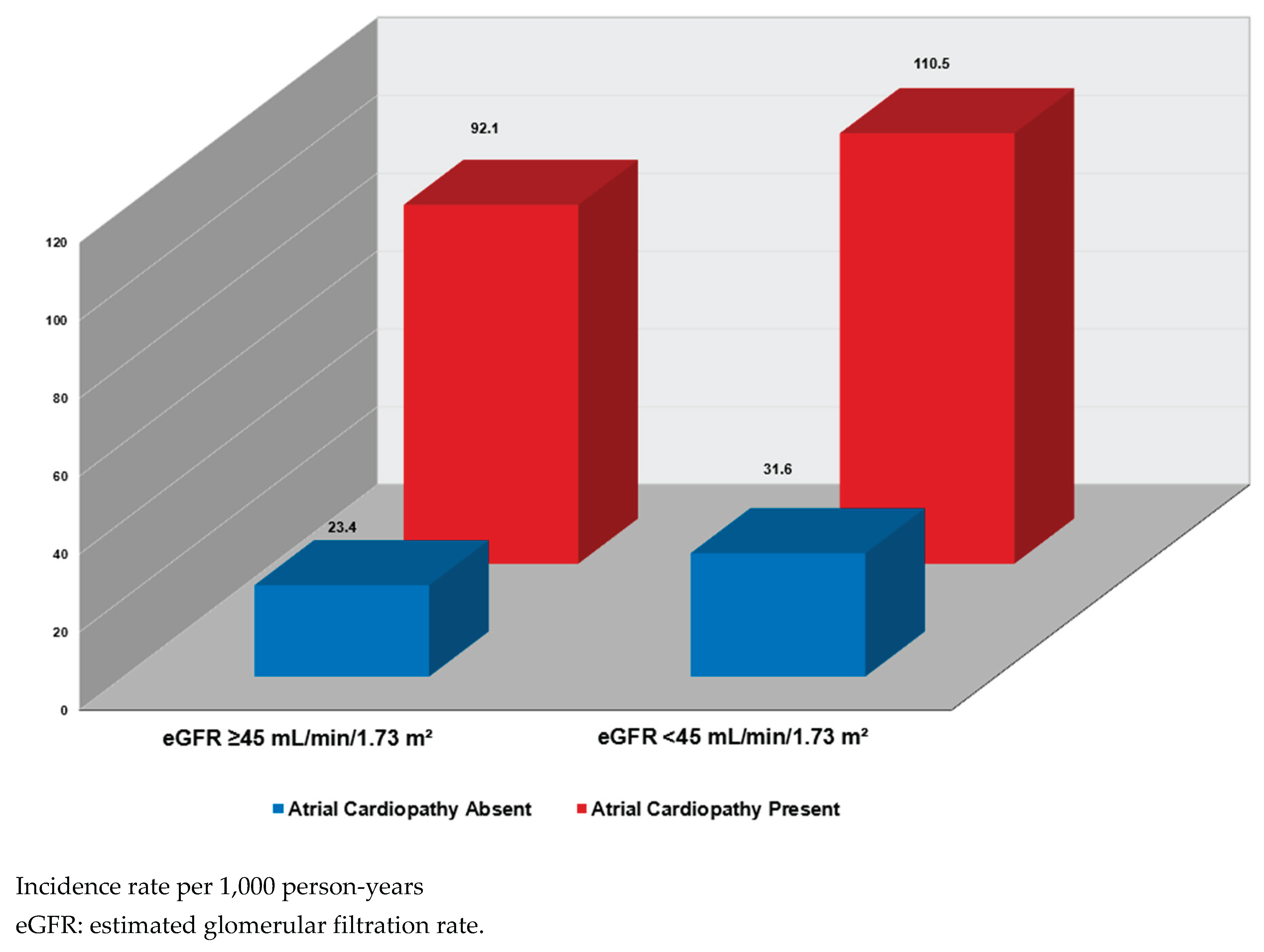

Mortality incidence rates were calculated per 1,000 person-years, stratified by eGFR level and atrial cardiopathy status. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate associations of impaired renal function (eGFR <45 vs. ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2), atrial cardiopathy (present vs. absent), and their combined presence with all-cause mortality. Covariate adjustments followed the same sequence as in logistic regression (Model 1 and Model 2). The interaction between eGFR and atrial cardiopathy was tested in Model 2.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p <0.05.

3. Results

This analysis included 6,573 participants (mean age 57.0 ± 13.0 years; 50.5% women; 74.6% White). At baseline, 47.9% (n=3,151) had atrial cardiopathy. Compared with those without atrial cardiopathy, affected participants were older and more likely to have diabetes and a history of cardiovascular disease. They also exhibited higher systolic blood pressure, greater body mass index, lower mean eGFR, and a higher proportion with eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m

2 (

Table 1).

In logistic regression models adjusted for sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors, reduced eGFR (<45 mL/min/1.73 m

2) was associated with significantly 44% higher odds of atrial cardiopathy compared with eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m

2. When modeled as a continuous variable, each 1-SD decrease in eGFR was similarly associated with increased odds of atrial cardiopathy (OR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.15) (

Table 2).

Over a median follow-up of 18.1 years, 3,076 deaths occurred. In Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors, both atrial cardiopathy and reduced renal function were associated with higher odds of mortality ((HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.04–1.20) vs. (HR:1.50, ; 95% CI: 1.34-1.68), respectively. In a dose response fashion, each 1-SD decrease in eGFR was associated an incremental 10% increased risk of mortality (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

In joint analyses, mortality risk increased stepwise across combinations of atrial cardiopathy and eGFR categories. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the highest mortality rate was observed among participants with both atrial cardiopathy and eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m

2, while the lowest rate was observed in those without atrial cardiopathy and with eGFR ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m

2. In multivariable Cox models, coexistence of both conditions conferred the greatest risk (HR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.46–1.94), exceeding the risk associated with atrial cardiopathy alone or impaired renal function defined as lower eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m

2 alone (interaction p=0.011) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

With increasing prevalence, mortality, and morbidity of both cardiovascular and renal diseases worldwide, examining their interrelationship as well as identifying modifying factors associated with worse prognosis is crucial. In this racially and ethnically representative sample, our study revealed that reduced kidney function (eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2) is associated with increased risk of atrial cardiopathy. In longitudinal analysis, both reduced eGFR and atrial cardiopathy were independently associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality. Importantly, when both conditions coexisted, the risk of mortality was highest. This observation reflects the overlapping and synergistic mechanisms that accelerate progression toward adverse outcomes.

Over recent years, research has increasingly clarified the interrelationship between kidney disease and atrial remodeling, linking renal dysfunction to atrial arrhythmias, particularly AF [

14,

15]. In our analysis, reduced eGFR was associated with a 44% higher risk of atrial cardiopathy, underscoring the adverse impact of impaired renal function on atrial structure and electrophysiology. These findings are consistent with and extend previous reports linking renal dysfunction to atrial pathology.

For an instance, in the MESA study, participants with both electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality and albuminuria had a 2.43-fold higher risk of developing AF compared with those without either condition [

14]. A large systematic review and meta-analysis by Ha et al., including over 28 million participants, further confirmed that eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 and albuminuria were associated with 43% and 64% higher risks of incident AF, respectively, reinforcing the link between renal impairment and atrial electrical abnormalities [

16]. Interestingly, Gong et al. also demonstrated a possible bidirectional relationship in diabetic populations, showing that left atrial volume index and strain parameters were independently associated with renal impairment, with progressive atrial dysfunction as kidney disease advanced [

17]. Collectively, these findings suggest that kidney dysfunction and atrial remodeling are interrelated processes that may amplify each other’s adverse effects.

Although some of these studies evaluated AF as the primary outcome, the observed associations likely reflect a shared atrial disease substrate characterized by fibrosis, conduction delay, and mechanical dysfunction. Our findings extend this evidence by demonstrating that reduced eGFR is associated with atrial cardiopathy which is an intermediate phenotype of atrial disease representing a mechanistic pathway linking renal dysfunction to increased all-cause mortality.

The association between low eGFR and atrial cardiopathy reflects a combination of structural, electrical, and metabolic stress on the atria. Reduced kidney function promotes chronic activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems, leading to systemic inflammation, which in turn trigger oxidative stress, and fluid overload. These processes increase atrial wall tension, trigger fibroblast activation, and cause extracellular matrix deposition, resulting in atrial fibrosis and impaired conduction [

18]. Alongside this, the electrolyte imbalances associated with low eGFR including elevated serum levels of potassium and phosphorus play a role as well as it disrupts ion channel function, prolong atrial depolarization, and alter P-wave morphology.

19 Over time, these changes create a vulnerable atrial substrate prone to abnormal conduction and mechanical dysfunction, even before the onset of atrial fibrillation [

19,

20,

21].

From a prognostic standpoint, our findings demonstrated that both atrial cardiopathy and reduced kidney function are independently associated with increased mortality risk, with the greatest risk observed when both conditions coexist. This pattern supports the hypothesis that structural and electrical atrial abnormalities in atrial cardiopathy may amplify the systemic consequences of renal dysfunction, while declining kidney health may worsen atrial remodeling, together driving patients into a higher-risk trajectory.

The mortality risk associated with kidney disease is largely attributed to enhanced cardiovascular risk, even beyond progression to end-stage renal failure in many cohorts [3−6,22−24]. The mechanisms include a proinflammatory state, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and activation of maladaptive neurohormonal systems, which together accelerate vascular aging, atherosclerosis, vascular calcification, and myocardial fibrosis [18−21,25,26]. Impaired excretory function leads to accumulation of uremic toxins, volume overload, disturbances in mineral metabolism, and electrolyte derangements, all of which further stress the cardiovascular system.

19 These pathologies can impair myocardial structure, promote left ventricular hypertrophy, and predispose to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death [

22,

23]. In addition, the microvascular ischemia and endothelial injury inherent to kidney disease may likewise contribute to atrial ischemia and fibrosis, setting the stage for atrial cardiopathy [

24].

Meanwhile, atrial cardiopathy confers mortality risk through mechanisms linked to thrombosis, arrhythmia, and heart failure [

25,

26]. Structural and electrical remodeling of the atria including fibrosis and conduction heterogeneity promotes blood stasis, which increases the likelihood of clot formation and systemic embolism [

26]. In addition, the effect of atrial cardiopathy on atrial structural and functional status can lead to atrial contractile dysfunction, thereby reducing cardiac output and promoting heart failure decompensation [

25]. Several cohort studies have shown that markers of atrial dysfunction as evident by abnormal P-wave indices or reduced atrial strain predict all-cause mortality and ischemic events independent of overt AF [

27].

The observed synergy between reduced eGFR and atrial cardiopathy may reflect the intersection of these shared and distinct pathways. Systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, neurohormonal activation, endothelial injury, and fibrotic remodeling act as common mediators [18−21,25,26]. Kidney disease may potentiate atrial injury via volume overload, hypertension, metabolic derangements, and microvascular ischemia, while atrial pathology may worsen renal hemodynamics, elevate upstream pressures, compromise cardiac–renal coupling, and amplify neurohormonal stress [

18,

21]. The cycle may intensify over time, accelerating progression toward decompensated heart failure, arrhythmic events, and multiorgan dysfunction, thereby elevating mortality beyond what either condition would produce in isolation.

These results highlight the need for closer clinical attention to atrial cardiopathy markers in patients with reduced kidney function, as their coexistence may identify a subgroup at particularly high risk. Understanding this overlap may help guide risk categorization and early intervention strategies, particularly in community-based settings where comorbidities may otherwise remain undetected. Clinically, our findings emphasize the importance of incorporating simple ECG markers into risk stratification for patients with impaired renal function. Identification of atrial cardiopathy in this population could inform targeted early interventions, closer cardiovascular monitoring, and refinement of existing prognostic tools to improve outcome prediction and patient management.

Limitations:

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we adjusted many sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors, but some residual confounding from unmeasured variables such as inflammatory markers, medication adherence, or other socioeconomic determinants. Second, we used ECG markers for detecting the atrial cardiopathy, which, despite being reproducible and widely available, may not fully detect the structural and functional atrial remodeling that could be assessed with imaging or biomarker data. Finally, our findings are based on U.S. adults from NHANES-III, it might be not enough for generalizability or applicable for non-U.S. populations.

5. Conclusions

In this nationally representative cohort of middle-aged and older U.S. adults, impaired renal function and electrocardiographic atrial cardiopathy were each independently associated with increased all-cause mortality, and their coexistence conferred a synergistically elevated risk. These findings underscore the value of simple ECG markers for identifying high-risk individuals with chronic kidney disease in community settings. Incorporating atrial cardiopathy assessment into routine care for patients with reduced eGFR may enhance risk stratification and guide early preventive interventions. Future research should evaluate whether targeted therapies addressing atrial remodeling in patients with kidney disease can mitigate this amplified mortality risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.S. and R.K.; methodology, E.Z.S., M.A.M. and R.K.; software, R.K.; validation, E.Z.S., R.K. and T.Z. formal analysis, R.K.; investigation, R.K., E.Z.S.,M.S.E and T.Z resources, R.K.; data curation, R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Z, M.Z.S, M.A.M., M.S.E; writing T.Z, M.Z.S, and M.A.M review and editing, A.E.S., M.A.M. and T.A.Z.; visualization, R.K.; supervision, M.A.M. and E.Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional ethical review and approval were waived for this study as data used were de-identified and publicly available.

Informed Consent Statement

For the current analysis, patient consent was waived because our study used publicly available, de-identified data from the NHANES database. As part of the standard NHANES protocol, at the time of original data collection (1988–1994) all participants provided documented informed consent at the time of original home interview and health examination. In accordance with ethical guidelines and institutional policies, the use of such data does not require additional informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goette A, Kalman JM, Aguinaga L, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: definition, characterization, and clinical implication. Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Card Electrophysiol J Work Groups Card Pacing Arrhythm Card Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2016;18(10):1455-1490. [CrossRef]

- Edwards JD, Healey JS, Fang J, Yip K, Gladstone DJ. Atrial Cardiopathy in the Absence of Atrial Fibrillation Increases Risk of Ischemic Stroke, Incident Atrial Fibrillation, and Mortality and Improves Stroke Risk Prediction. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;9(11):e013227. [CrossRef]

- Cockwell P, Fisher LA. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10225):662-664. [CrossRef]

- Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One. 2016;11(7):e0158765. [CrossRef]

- Yu AS, Pak KJ, Zhou H, et al. All-Cause and Cardiovascular-Related Mortality in CKD Patients With and Without Heart Failure: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. Kidney Med. 2023;5(5):100624. [CrossRef]

- Vondenhoff S, Schunk SJ, Noels H. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Herz. 2024;49(2):95-104. [CrossRef]

- Ryu H, Kim J, Kang E, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality in Korean patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1131. [CrossRef]

- Bansal N, Xie D, Sha D, et al. Cardiovascular Events after New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Adults with CKD: Results from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2018;29(12):2859-2869. [CrossRef]

- Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013;382(9889):339-352. [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | Does Chronic Kidney Disease Result in High Risk of Atrial Fibrillation? Accessed October 4, 2025. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cardiovascular-medicine/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2019.00082/full.

- Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, 1999-2010. Vital Health Stat Ser 1 Programs Collect Proced. 2013;(56):1-37.

- He J, Tse G, Korantzopoulos P, et al. P-Wave Indices and Risk of Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke. 2017;48(8):2066-2072. [CrossRef]

- P-wave durations from automated electrocardiogram analysis to predict atrial fibrillation and mortality in heart failure - PubMed. Accessed October 4, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36461637/.

- Ahmad MI, Chen LY, Singh S, Luqman-Arafath TK, Kamel H, Soliman EZ. Interrelations between albuminuria, electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality, and incident atrial fibrillation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2023;383:102-109. [CrossRef]

- Bao M qiang, Shu G jun, Chen C jin, Chen Y nong, Wang J, Wang Y. Association of chronic kidney disease with all-cause mortality in patients hospitalized for atrial fibrillation and impact of clinical and socioeconomic factors on this association. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9. [CrossRef]

- Ha JT, Freedman SB, Kelly DM, et al. Kidney Function, Albuminuria, and Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2024;83(3):350-359.e1. [CrossRef]

- Gong M, Xu M, Pan S, Jiang X. Association between left atrial remodeling and early renal impairment in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025;25(1):436. [CrossRef]

- Cardiac Fibrosis in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications - PubMed. Accessed October 4, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26293766/.

- Navarro-Garcia JA, Keefe JA, Song J, Li N, Wehrens XHT. Mechanisms underlying atrial fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2025;205:37-51. [CrossRef]

- Kiuchi MG. Atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: A bad combination. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2018;37(2):103-105. [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | Chronic Kidney Disease Increases Atrial Fibrillation Inducibility: Involvement of Inflammation, Atrial Fibrosis, and Connexins. Accessed October 4, 2025. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01726/full.

- Turakhia MP, Blankestijn PJ, Carrero JJ, et al. Chronic kidney disease and arrhythmias: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(24):2314-2325. [CrossRef]

- Pun PH. The interplay between CKD, sudden cardiac death, and ventricular arrhythmias. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(6):480-488. [CrossRef]

- Querfeld U, Mak RH, Pries AR. Microvascular disease in chronic kidney disease: the base of the iceberg in cardiovascular comorbidity. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(12):1333-1356. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad MI, Mujtaba M, Floyd JS, Chen LY, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic markers of atrial cardiomyopathy and risk of heart failure in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1143338. Published 2023 Apr 26. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro E, Winters J, van Nieuwenhoven FA, Schotten U, Verheule S. The Complex Relation between Atrial Cardiomyopathy and Thrombogenesis. Cells. 2022 Sep 22;11(19):2963. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen LY, Soliman EZ. P Wave Indices-Advancing Our Understanding of Atrial Fibrillation-Related Cardiovascular Outcomes. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:53. Published 2019 May 3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).