Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria for Comorbidities:

2.3. Measurement of Plasma Lipids, Glucose, Glycated Hemoglobin and High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

2.4. Calculation of Glomerular Filtration Rate and Body Mass Index

2.5. Measurement of Cardiac Structure and Function

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics According to Tertile MLR

3.2. Cardiac Remodeling According to Tertile MLR

3.3. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of MLR with Clinical Characteristics and Echocardiographic Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chung, S.C.; Sofat, R.; Acosta-Mena, D.; Taylor, J.A.; Lambiase, P.D.; Casas, J.P.; Providencia, R. Atrial fibrillation epidemiology, disparity and healthcare contacts: A population-wide study of 5.6 million individuals. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 7, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, M.; Laroche, C.; Nieuwlaat, R.; Crijns, H.; Maggioni, A.P.; Lane, D.A.; Boriani, G.; Lip, G.Y.H. Registry E-AGP, Euro Heart Survey on AFI: Increased burden of comorbidities and risk of cardiovascular death in atrial fibrillation patients in Europe over ten years: A comparison between EORP-AF pilot and EHS-AF registries. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 55, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inciardi, R.M.; Giugliano, R.P.; Claggett, B.; Gupta, D.K.; Chandra, A.; Ruff, C.T.; Antman, E.M.; Mercuri, M.F.; Grosso, M.A.; Braunwald, E.; et al. Left atrial structure and function and the risk of death or heart failure in atrial fibrillation. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartas, A.; Samaras, A.; Akrivos, E.; Vrana, E.; Papazoglou, A.S.; Moysidis, D.V.; Papanastasiou, A.; Baroutidou, A.; Botis, M.; Liampas, E.; et al. Tauhe association of heart failure across left ventricular ejection fraction with mortality in atrial fibrillation. ESC. Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu,Y. F.; Chen,Y.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, S.A. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, K.; Sasano,T. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 862164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulin, J.; Siegbahn, A.; Hijazi, Z.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Andersson, U.; Connolly, S.J.; Huber, K.; Reilly, P.A.; Wallentin, L.; Oldgren, J. Interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein and risk for death and cardiovascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, T.; Hijazi, Z.; Lindback, J.; Oldgren, J.; Alexander, J.H.; Connolly, S.J.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Granger, C.B.; Lopes, R.D.; et al. Using multimarker screening to identify biomarkers associated with cardiovascular death in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2112–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Sun, J.Y.; Lou, Y.X.; Sun, W.; Kong, X.Q. Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 379, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46 (Suppl 1), S19–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Thiruvengadam, R. Hypertension in an ageing population: Diagnosis, mechanisms, collateral health risks, treatments, and clinical challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 98, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.J.; Davis, A.M.; Jan, R.H. Management of gout. JAMA. 2021, 326, 2519–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.J.H.; Gransar, H.; Rozanski, A.; Dey, D.; Al-Mallah, M.; Chow, B.J.W.; Kaufmann, P.A.; Cademartiri, F.; Maffei, E.; Han, D.; et al. Simplified approach to predicting obstructive coronary disease with integration of coronary calcium: Development and external validation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Morice, M.C.; Kappetein, A.P.; Colombo, A.; Holmes, D.R.; Mack, M.J.; Stahle, E.; Feldman, T.E.; van den Brand, M.; Bass, E.J.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miida, T.; Nishimura, K.; Hirayama, S.; Miyamoto, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Masuda, D.; Yamashita, S.; Ushiyama, M.; Komori, T.; Fujita, N.; et al. Homogeneous assays for LDL-C and HDL-C are reliable in both the postprandial and fasting state. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2017, 24, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, D.M.; Wright, M.; Baker, P.; Sackett, D. D-dimer for the exclusion of venous thromboembolism: Comparison of a new automated latex particle immunoassay (MDA D-dimer) with an established enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (VIDAS D-dimer). Clin. Lab. Haematol. 1999, 21, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Buggs, V.; Samara, V.A.; Bahri, S. Calculation of the estimated glomerular filtration rate using the 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation and whole blood creatinine values measured with radiometer ABL 827 FLEX. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022, 60, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, G.; Zhu, Y.; Laukkanen, J.A. Glomerular filtration dysfunction is associated with cardiac adverse remodeling in menopausal diabetic Chinese women. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Liu, C.; Song, X.; Zhu, Y. Low body mass is associated with reduced left ventricular mass in Chinese elderly with severe COPD. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, G.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Song, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, L.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. Higher neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with renal dysfunction and cardiac adverse remodeling in elderly with metabolic syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 921204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi,V. ; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, G.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Wei, L.; Chen, X. Higher LDL-C/HDL-C ratio is associated with elevated HbA1c and decreased eGFR levels and cardiac remodeling in elderly with hypercholesterolemia. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Association of high apoB/apoA1 ratio with increased erythrocytes, platelet/lymphocyte ratio, D-dimer, uric acid and cardiac remodeling in elderly heart failure patients: A retrospective study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Shi, K.; Lv, J.; Pang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pei, P.; Du, H.; Millwood, I.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; et al. Association of dietary patterns, circulating lipid profile, and risk of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2023, 31, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escasany, E.; Izquierdo-Lahuerta, A.; Medina-Gomez, G. Underlying mechanisms of renal lipotoxicity in obesity. Nephron 2019, 143, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandino, J.; Martin-Taboada, M.; Medina-Gomez, G.; Vila-Bedmar, R.; Morales, E. Novel insights in the physiopathology and management of obesity-related kidney disease. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Ju, F.; Cai, Y.; Gang, X.; Wang, G. The role of lipotoxicity in kidney disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Ricart, M.; Torramade-Moix, S.; Pascual, G.; Palomo, M.; Moreno-Castano, A.B.; Martinez-Sanchez, J.; Vera, M.; Cases, A.; Escolar, G. Endothelial damage, inflammation and immunity in chronic kidney disease. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornoni, A. Proteinuria, the podocyte, and insulin resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Hao, J.; Hu, H.; Hao, L. The level of serum albumin is associated with renal prognosis and renal function decline in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC. Nephrol. 2023, 24, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Tao, L.; Zhu, Q.; Jiao, X.; Yan, L.; Shao, F. Association between the metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) among health check-up population in Japan: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1027262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, T.; Neytchev, O.; Witasp, A.; Kublickiene, K.; Stenvinkel, P.; Shiels, P.G. Inflammation and oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2021, 35, 1426–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, J.J.; Aguilera, A.; Stenvinkel, P.; Gil, F.; Selgas, R.; Lindholm, B. Appetite disorders in uremia. J. Ren. Nutr. 2008, 18, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, X.; Xie, S.; Liu, C. Monocyte lymphocyte ratio predicts the new-onset of chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.J.; Jiang, C.Q.; Zhang,W. S.; Cheng, K.K.; Schooling, C.M.; Xu, L.; Liu, B.; Jin, Y.L.; Hubert Lam, K.B.; Lam, T.H. Alcohol sensitivity, alcohol use and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in older Chinese men: The Guangzhou biobank cohort study. Alcohol. 2016, 57, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, N.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, P.; Ping, P.; Fu, S. Relationships between smoking behavior, systemic inflammation, and myocardial infarction and their effects on long-term outcomes in older Chinese patients with coronary artery disease: A prospective study with a 10-year follow-up. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauriello, A.; Correra, A.; Maratea, A.C.; Caturano, A.; Liccardo, B.; Perrone, M.A.; Giordano, A.; Nigro, G.; D’Andrea, A.; Russo, V. Serum lipids, inflammation, and the risk of atrial fibrillation: Pathophysiological links and clinical evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.; Yin, X.; Roetker, N.S.; Magnani, J.W.; Kronmal, R.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Chen, L.Y.; Lubitz, S.A.; McClelland, R.L.; McManus, D.D.; et al. Blood lipids and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis and the Framingham heart study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, R.; Baines, O.; Hayes, A.; Tompkins, K.; Kalla, M.; Holmes, A.P.; O’Shea, C.; Pavlovic, D. Impact of obesity on atrial fibrillation pathogenesis and treatment options. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carna, Z.; Osmancik, P. The effect of obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, alcohol, and sleep apnea on the risk of atrial fibrillation. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70 (Suppl4), S511–S525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, R.; Staszewsky, L.; Sun, J.L.; Bethel, M.A.; Disertori, M.; Haffner, S.M.; Holman, R.R.; Chang, F.; Giles, T.D.; Maggioni, A.P.; et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in a population with impaired glucose tolerance: The contribution of glucose metabolism and other risk factors. a post hoc analysis of the nateglinide and valsartan in impaired glucose tolerance outcomes research trial. Am. Heart J. 2013, 166, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Cai, W.; Dong, Y.; Xue, R.; Liu, C. Meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome and its individual components with risk of atrial fibrillation in different populations. BMC. Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, A.; Correra, A.; Maratea, A.C.; Caturano, A.; Liccardo, B.; Perrone, M.A.; Giordano, A.; Nigro, G.; D’Andrea, A.; Russo, V. Serum lipids, inflammation, and the risk of atrial fibrillation: Pathophysiological links and clinical evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.X.; Ganesan, A.N.; Selvanayagam, J.B. Epicardial fat and atrial fibrillation: Current evidence, potential mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, G.; Massaro, J.M.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Hoffmann, U.; Levy, D.; Ellinor, P.T.; Wang, T.J.; Schnabel, R.B.; Vasan, R.S.; Fox, C.S.; et al. Pericardial fat is associated with prevalent atrial fibrillation: The Framingham heart study. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2010, 3, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadic, M.; Ivanovic, B.; Cuspidi, C. Metabolic syndrome and right ventricle: An updated review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 24, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, R.; Abu Jaber, B.; Alzuqaili, T.; Ghura, S.; Al-Ajlouny, T.; Saadeh, A.M. The relationship of atrial fibrillation with left atrial size in patients with essential hypertension. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Huang, Z.; Tang, X.; Peng, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, H.; Li, S. Monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is associated with subclinical left cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. Heart J. 2022, 63, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahal, H.; McClelland, R.L.; Tandri, H.; Jain, A.; Turkbey, E.B.; Hundley, W.G.; Barr, R.G.; Kizer, J.; Lima, J.A.C.; Bluemke, D.A.; et al. Obesity and right ventricular structure and function: The MESA-right ventricle study. Chest 2012, 141, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seko, Y.; Kato, T.; Haruna, T.; Izumi, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Nakane, E.; Inoko, M. Association between atrial fibrillation, atrial enlargement, and left ventricular geometric remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahik, V.D.; Frisdal, E.; Le Goff, W. Rewiring of lipid metabolism in adipose tissue macrophages in obesity: Impact on insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopaschuk, G.D. Fatty acid oxidation and its relation with insulin resistance and associated disorders. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 68, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.A. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and inflammation: An slalom to obesity and insulin resistance. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2006, 62, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.S.; Jansen, K.M. Impact of obesity-related inflammation on cardiac metabolism and function. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2021, 10, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saotome, M.; Ikoma, T.; Hasan, P.; Maekawa, Y. Cardiac insulin resistance in heart failure: The role of mitochondrial dynamics. Int. J. Mo.l Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.; Shultz, SP.; Dahiya, A.; Fu, J.; Flatley, C.; Duncan, D.; Cardinal, J.; Kostner, K.M.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P.; et al. Relation of reduced preclinical left ventricular diastolic function and cardiac remodeling in overweight youth to insulin resistance and inflammation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 115, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, C.; Tokarska, L.; Stuhlinger, M.; Feuchtner, G.; Hintringer, F.; Honold, S.; Fiedler, L.; Schonbauer, MS.; Schonbauer, R.; Plank, F. Structural cardiac remodeling in atrial fibrillation. JACC. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Association of monocyte-lymphocyte ratio with in-hospital mortality in cardiac intensive care unit patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 96, 107736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, M.; Liu, L.; Dang, X.; Zhu, D.; Tian, G. Monocyte/lymphocyte ratio is related to the severity of coronary artery disease and clinical outcome in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e16267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Low MLR | Moderate MLR | High MLR | r | P | |

| MLR ≤ 0.293 | 0.293 < MLR ≤ 0.460 | MLR > 0.460 | |||

| n=382 | n=392 | n=380 | |||

| MLR | 0.217 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.05* | 0.75 ± 0.38*† | 1 | <0.001 |

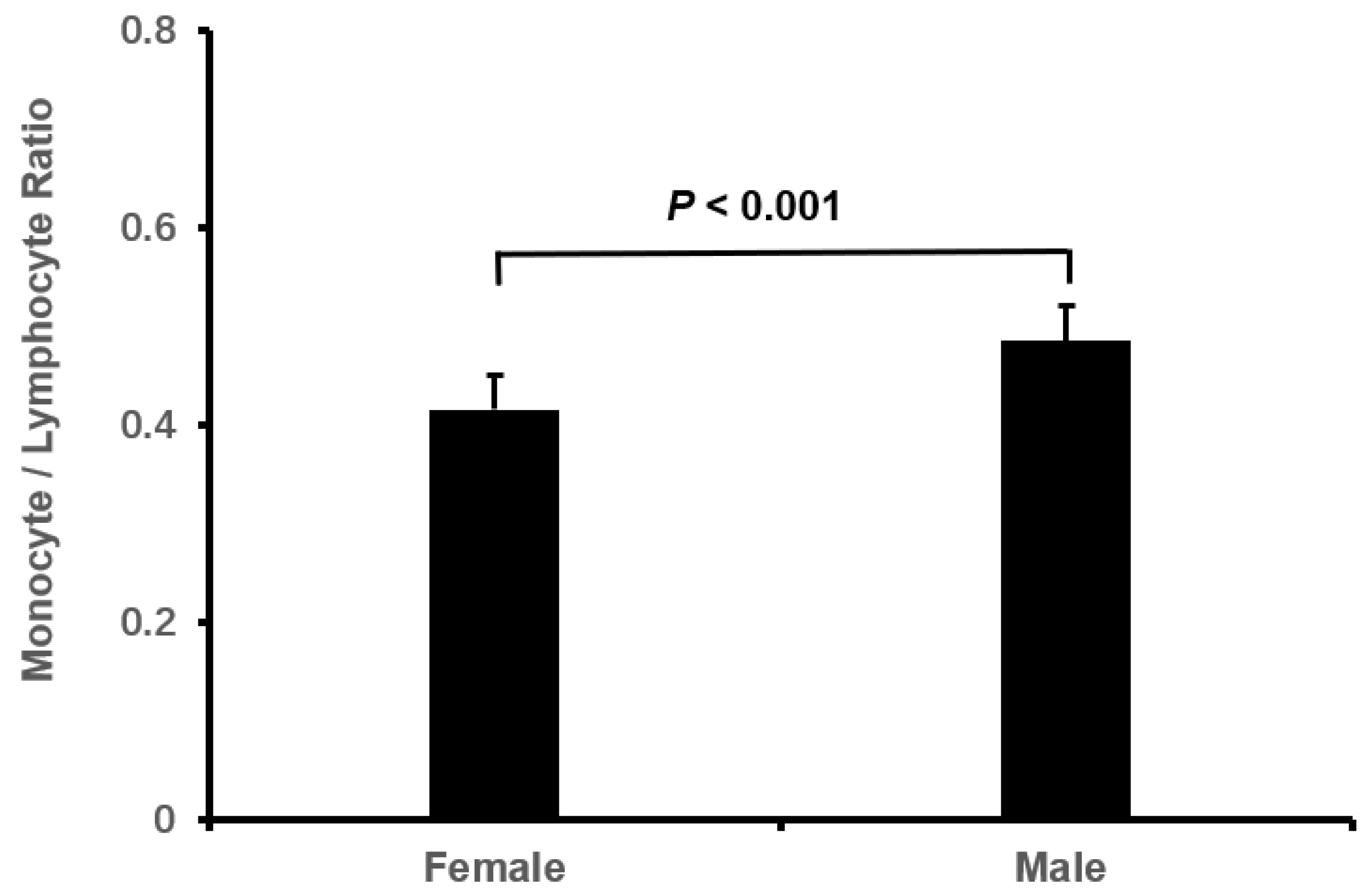

| male, n (%) | 132 (34.6) | 158 (40.3) | 199 (52.4)* | 0.146 | <0.001 |

| age, year | 76.93 ± 7.30 | 78.03 ± 6.71* | 80.22 ± 7.26*† | 0.185 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.51 ± 3.90 | 23.95 ± 3.97* | 23.45 ± 4.26* | -0.112 | 0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 73 (19.1) | 96 (24.5)* | 104 (27.4)*† | 0.079 | 0.024 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 45 (11.8) | 63 (16.1)* | 71 (18.7)*† | 0.078 | 0.028 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 132.02 ± 20.30 | 131.90 ± 21.49 | 130.76 ± 23.95 | -0.023 | 0.702 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 80.50 ± 14.66 | 78.18 ± 15.13* | 76.09 ± 15.69 * | -0.117 | <0.001 |

| Persistent AF, n (%) | 193 (50.5) | 205 (52.3) | 198 (52.1) | 0.013 | 0.869 |

| Long term persistent AF, n (%) | 152 (39.8) | 142 (36.2) | 148 (38.9) | -0.007 | 0.569 |

| Permanent AF, n (%) | 37 (9.7) | 45 (11.5) | 34 (8.9) | -0.010 | 0.492 |

| Type 2 DM, n (%) | 120 (31.4) | 125 (31.9) | 126 (33.2) | 0.015 | 0.874 |

| DM duration, years | 2.64 ± 5.93 | 3.04 ± 6.81 | 3.36 ± 7.07 | 0.044 | 0.329 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 278 (72.8) | 290 (74.0) | 264 (69.5) | -0.030 | 0.355 |

| Hypertensive duration, years | 9.87 ± 11.49 | 11.16 ± 12.26 | 11.16 ± 12.30 | 0.044 | 0.215 |

| Gout, n (%) | 7 (1.8) | 22 (5.6)* | 22 (5.8)* | 0.078 | 0.010 |

| Gout duration, year | 0.08 ± 0.92 | 0.38 ± 2.71 | 0.34 ± 2.27 | 0.050 | 0.103 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 166 (43.5) | 167 (42.6) | 185 (48.7) | 0.043 | 0.187 |

| Gensini score | 3.33 ± 9.48 | 4.01 ±11.23 | 3.97 ± 11.61 | 0.024 | 0.621 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 78 (20.4) | 98 (25.0) | 99 (26.1) | 0.054 | 0.151 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.37 ± 1.17 | 6.35 ± 1.17 | 6.46 ± 1.44 | 0.028 | 0.498 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.30 ± 0.73 | 1.11 ± 0.75* | 1.07 ± 0.65* | -0.131 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.24 ± 0.81 | 1.98 ± 0.75* | 1.90 ± 0.72* | -0.181 | <0.001 |

| HLD-C, mmol/L | 1.23 ± 0.38 | 1.22 ± 0.37 | 1.13 ± 0.36*† | -0.114 | <0.001 |

| D-dimer, mmol/L | 0.90 ± 1.54 | 1.29 ± 2.40* | 1.47 ± 1.94* | 0.113 | 0.001 |

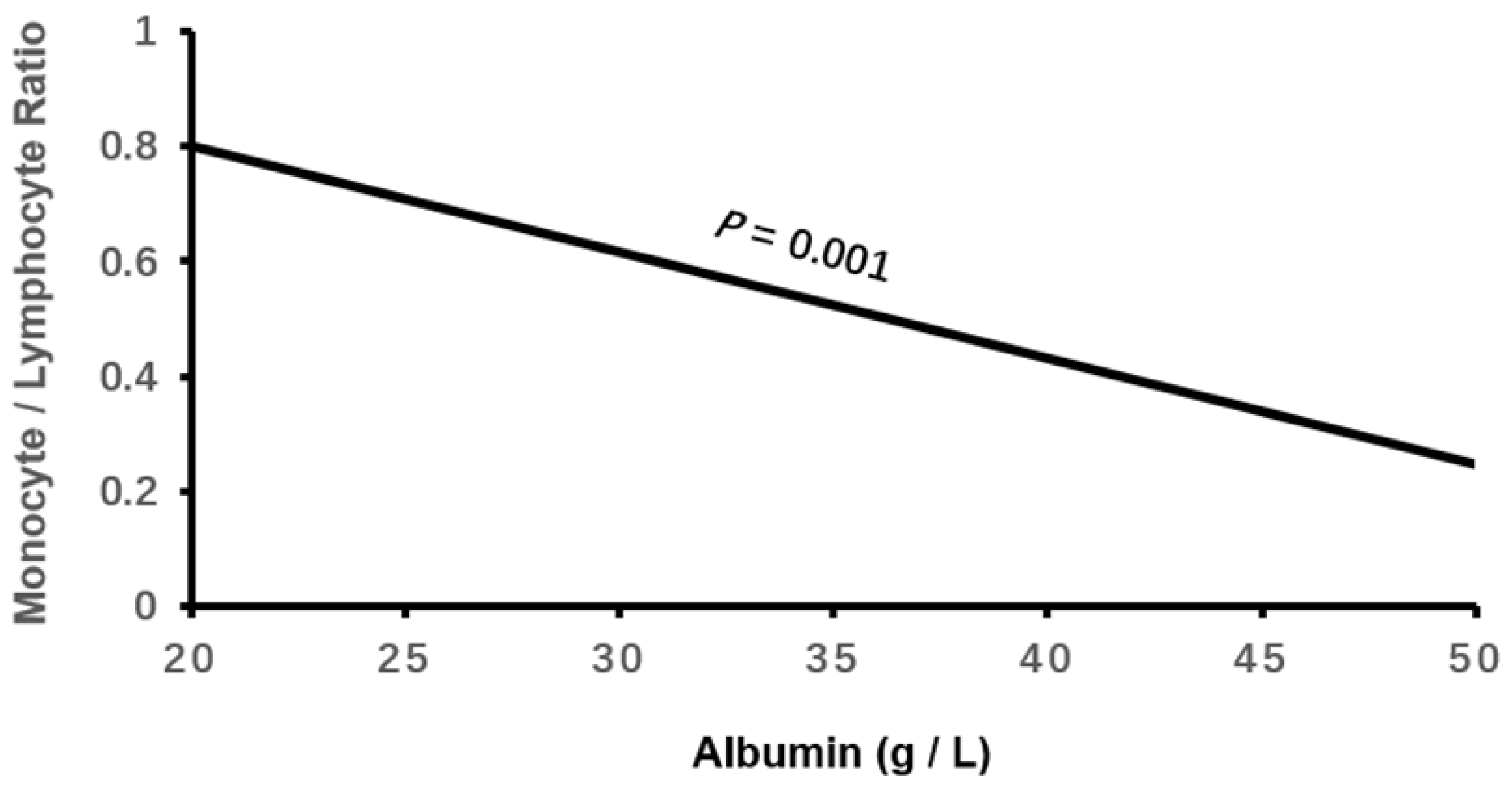

| Albumin, g/L | 40.97 ± 4.43 | 39.82 ± 4.61* | 37.57 ± 4.69*† | -0.289 | <0.001 |

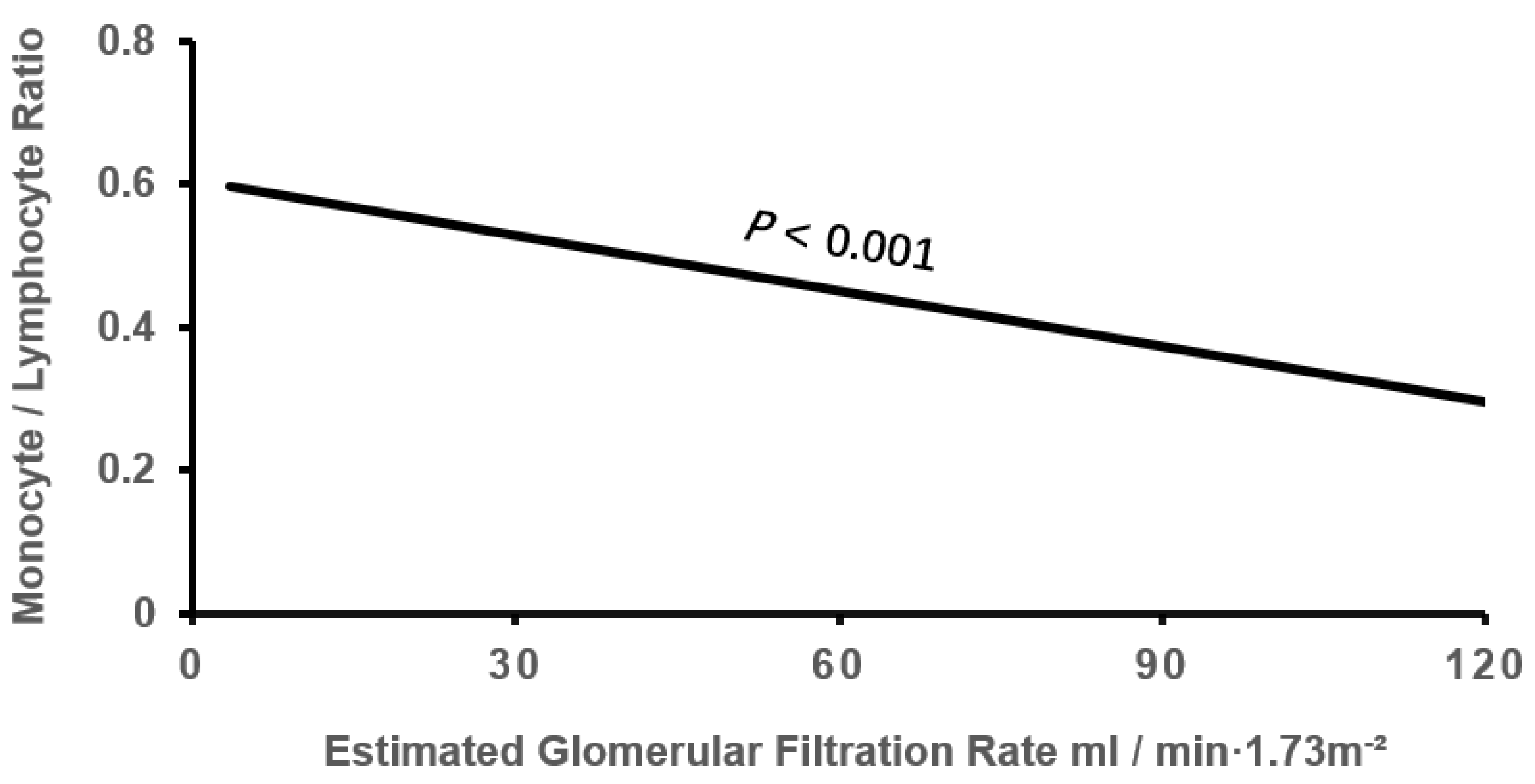

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 67.76 ± 19.19 | 63.27 ± 20.31* | 58.92 ± 24.56*† | -0.163 | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 3.21 ± 4.93 | 4.97 ± 6.20 * | 9,12 ± 7.60 *† | 0.354 | <0.001 |

| monocyte, ×109/L | 0.37 ± 0.13 | 0.47 ± 0.14* | 0.60 ± 0.21 *† | 0.545 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte, ×109/L | 1.72 ± 0.59 | 1.30 ± 0.40 * | 0.89 ± 0.35*† | -0.674 | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil, ×109/L | 3.83 ± 1.25 | 4.05 ± 1.30* | 4.67 ± 1.59*† | 0.445 | <0.001 |

| White blood cell, ×109/L | 6.07 ± 1.53 | 5.97 ± 1.55 | 6.30 ± 1.73*† | 0.059 | 0.018 |

| Low MLR group | Moderate MLR Group | High MLR group | r | P | |

| MLR≤0.293 | 0.293<MLR≤0.460 | MLR>0.460 | |||

| n=382 | n=392 | n=380 | |||

| RAD, mm | 41.94±5.32 | 43.56±6.75* | 44.75±6.82*† | 0.178 | <0.001 |

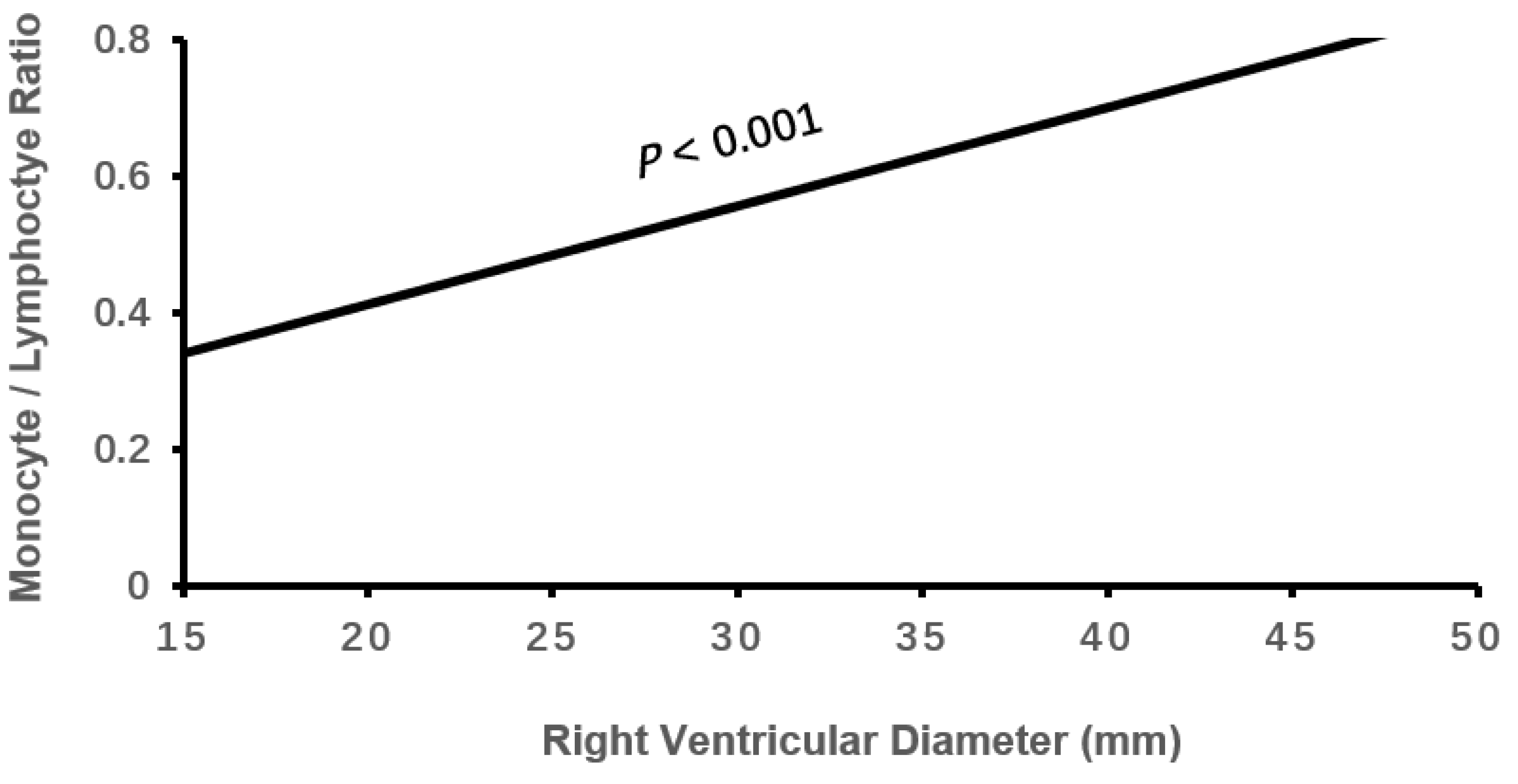

| RVD, mm | 20.60±3.06 | 21.34±3.44* | 22.30±4.40*† | 0.184 | <0.001 |

| LAD, mm | 39.96±6.09 | 41.09±6.04* | 41.92±6.15* | 0.129 | <0.001 |

| IVST, mm | 10.65±1.19 | 10.69±1.39 | 10.68±1.49 | 0.010 | 0.881 |

| LVPWT, mm | 10.48±1.13 | 10.52±1.26 | 10.52±1.28 | 0.012 | 0.875 |

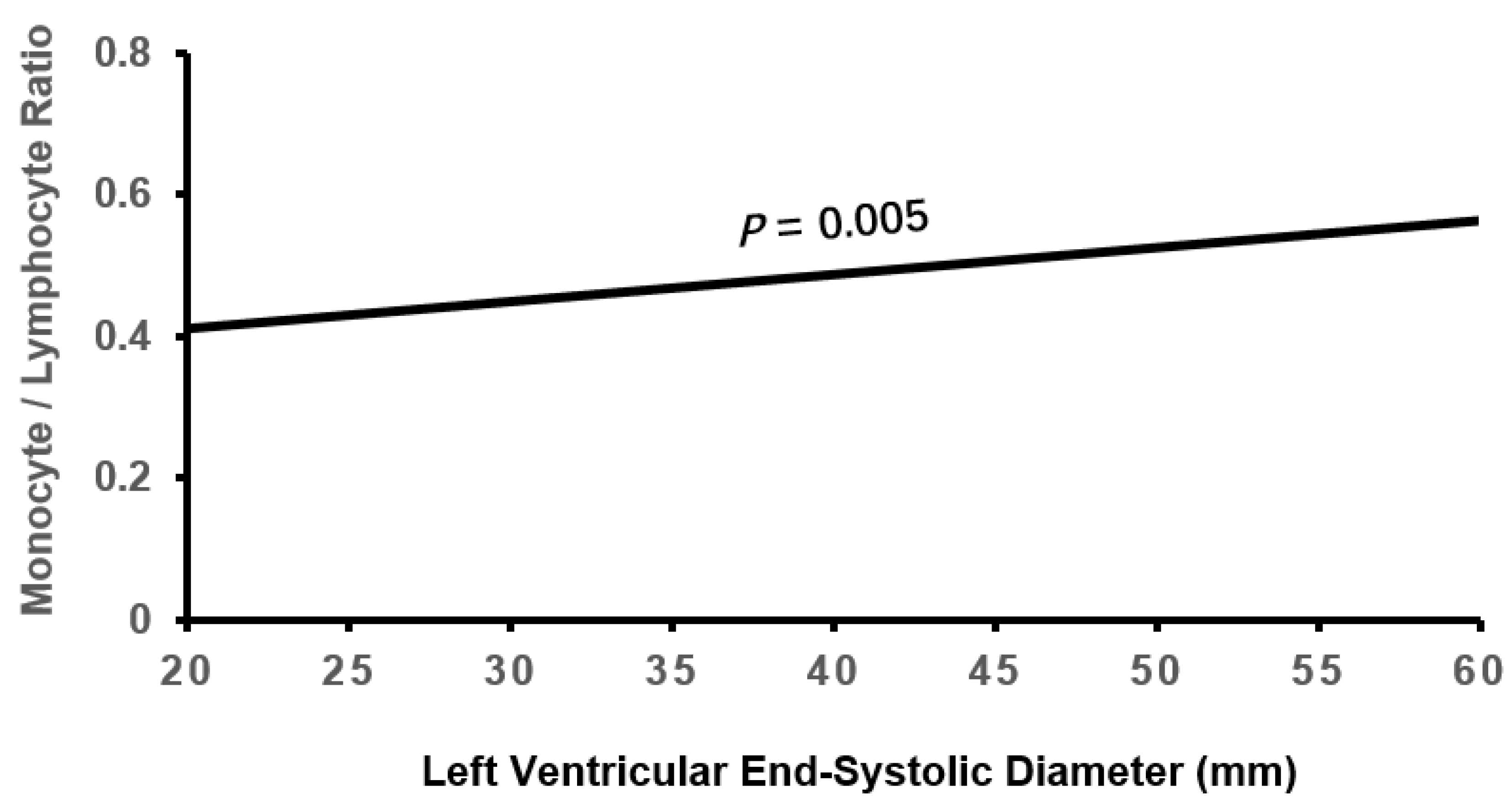

| LVESD, mm | 33.45±6.23 | 33.95±7.00 | 35.33±8.08*† | 0.107 | 0.001 |

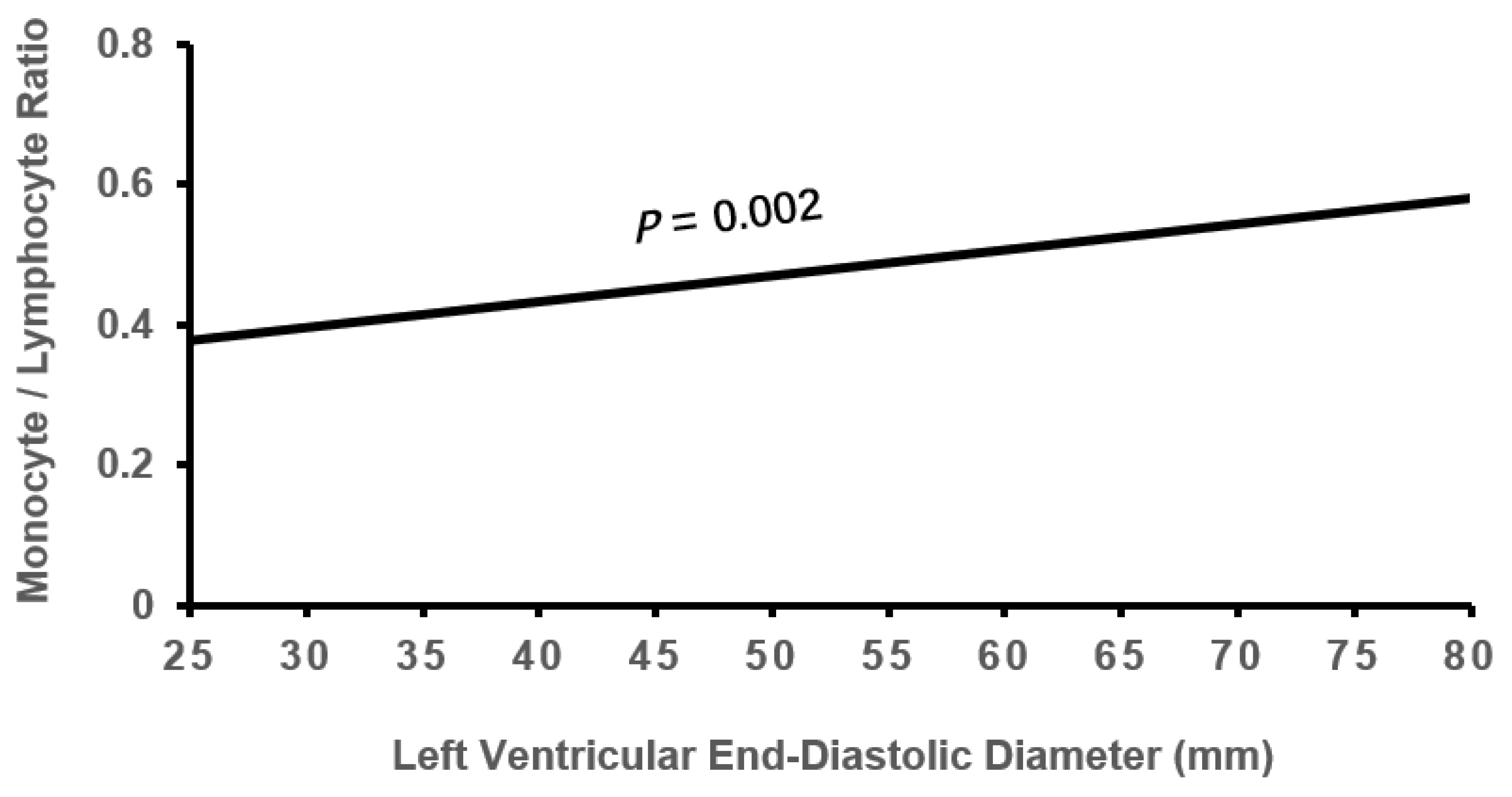

| LVEDD, mm | 47.66±6.01 | 48.44±6.90 | 49.61±7.94*† | 0.113 | 0.001 |

| PAP, mmHg | 39.04±10.22 | 40.40±10.23 | 43.54±12.26*† | 0.165 | <0.001 |

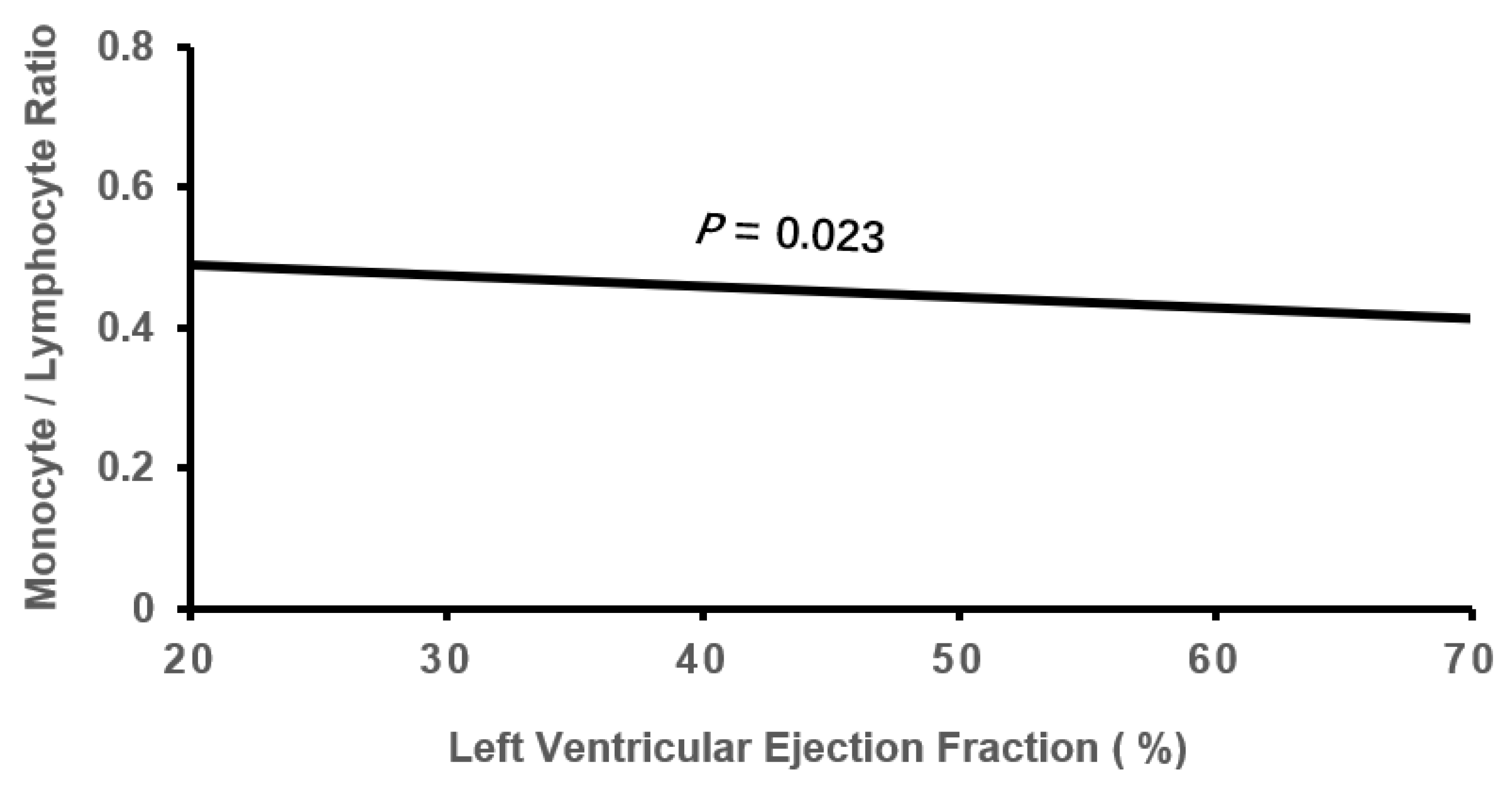

| LVEF, % | 58.38±8.30 | 58.05±8.79 | 56.15±9.79*† | -0.100 | 0.002 |

| β | SE | Wald χ2 | P | OR (95%CI) | |

| Male | 1.173 | 0.292 | 16.192 | <0.001 | 3.233(1.825-5.725) |

| Age | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.44 | 0.507 | 1.011(0.978-1.046) |

| BMI | -0.009 | 0.026 | 0.128 | 0.720 | 0.991(0.941-1.043) |

| Smoking | -0.344 | 0.383 | 0.804 | 0.370 | 0.709(0.334-1.503) |

| Drinking | -0.321 | 0.39 | 0.677 | 0.411 | 0.725(0.337-1.559) |

| Diastolic BP | -0.008 | 0.007 | 1.201 | 0.273 | 0.992(0.978-1.006) |

| Gout | 0.314 | 0.478 | 0.433 | 0.510 | 1.370(0.537-3.494) |

| Triglyceride | 0.174 | 0.211 | 0.684 | 0.408 | 1.190(0.788-1.800) |

| LDL-C | 0.063 | 0.155 | 0.163 | 0.686 | 1.065(0.786-1.442) |

| HDL-C | -0.186 | 0.318 | 0.341 | 0.559 | 0.831(0.446-1.549) |

| D-dimer | -0.027 | 0.07 | 0.147 | 0.701 | 0.974(0.849-1.116) |

| Albumin | -0.136 | 0.027 | 25.513 | <0.001 | 0.872(0.827-0.92) |

| eGFR | -0.013 | 0.005 | 5.852 | 0.016 | 0.987(0.977-0.998) |

| RAD | -0.021 | 0.023 | 0.851 | 0.356 | 0.979(0.936-1.024) |

| RVD | 0.105 | 0.036 | 8.486 | 0.004 | 1.110(1.035-1.192) |

| LAD | -0.016 | 0.022 | 0.562 | 0.453 | 0.984(0.943-1.026) |

| LVESD | -0.153 | 0.072 | 4.575 | 0.032 | 0.858(0.746-0.987) |

| LVEDD | 0.108 | 0.053 | 4.207 | 0.040 | 1.114(1.005-1.234) |

| PAP | 0.018 | 0.01 | 3.318 | 0.069 | 1.018(0.999-1.038) |

| LVEF | -0.071 | 0.029 | 6.239 | 0.012 | 0.931(0.880-0.985) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).