Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

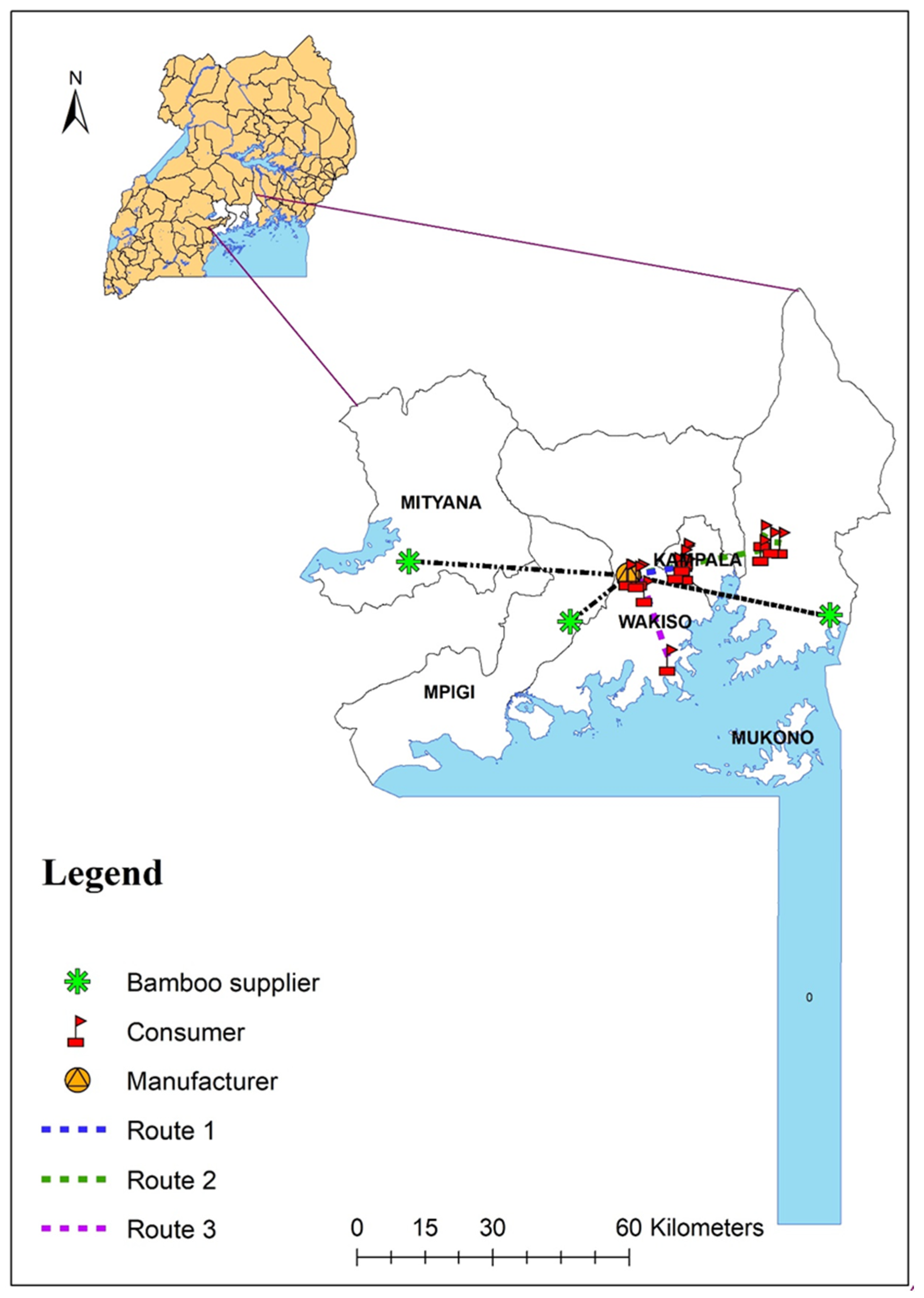

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

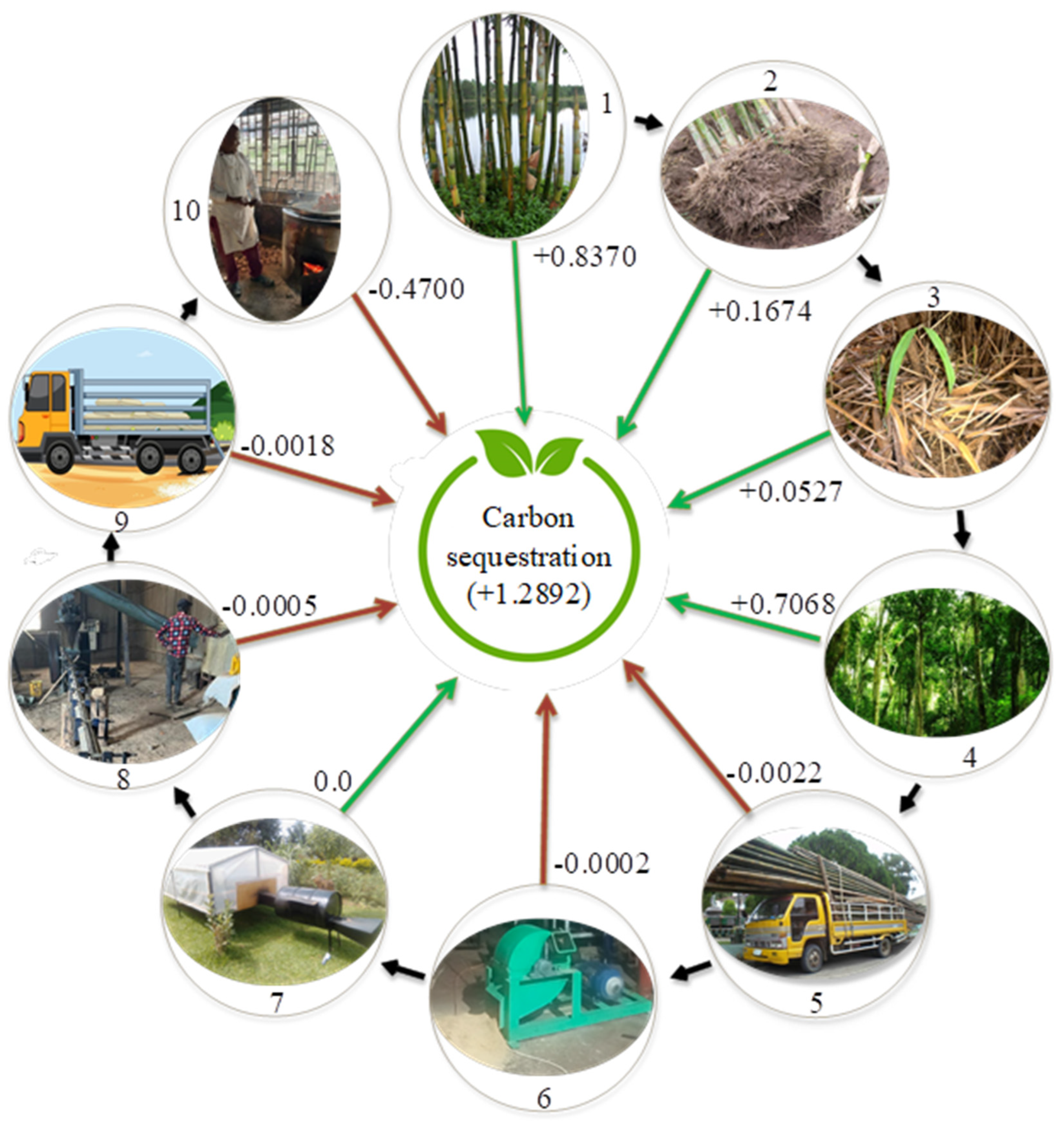

3.1. Above-Ground Carbon Sequestration from Bambusa vulgaris Clumps (Bucket 1)

3.2. Below-Ground Carbon Sequestration (Bucket 2)

3.3. Litter Carbon Sequestration (Bucket 3)

3.4. Continued Carbon Sequestration by the Saved Forest Trees (Bucket 4)

3.5. Transportation of Harvested Bambusa.vulgaris from the Plantation to the Manufacturing Facility (Bucket 5)

3.6. Crushing of Poles or Culms, Branches, and Leaves (Bucket 6)

3.7. Drying of the Crushed Bamboo (Bucket 7)

3.8. High Pressure Densification (Bucket 8)

3.9. Transporting YAZINI from the Manufacturing Facility to the Points of Use (Bucket 9)

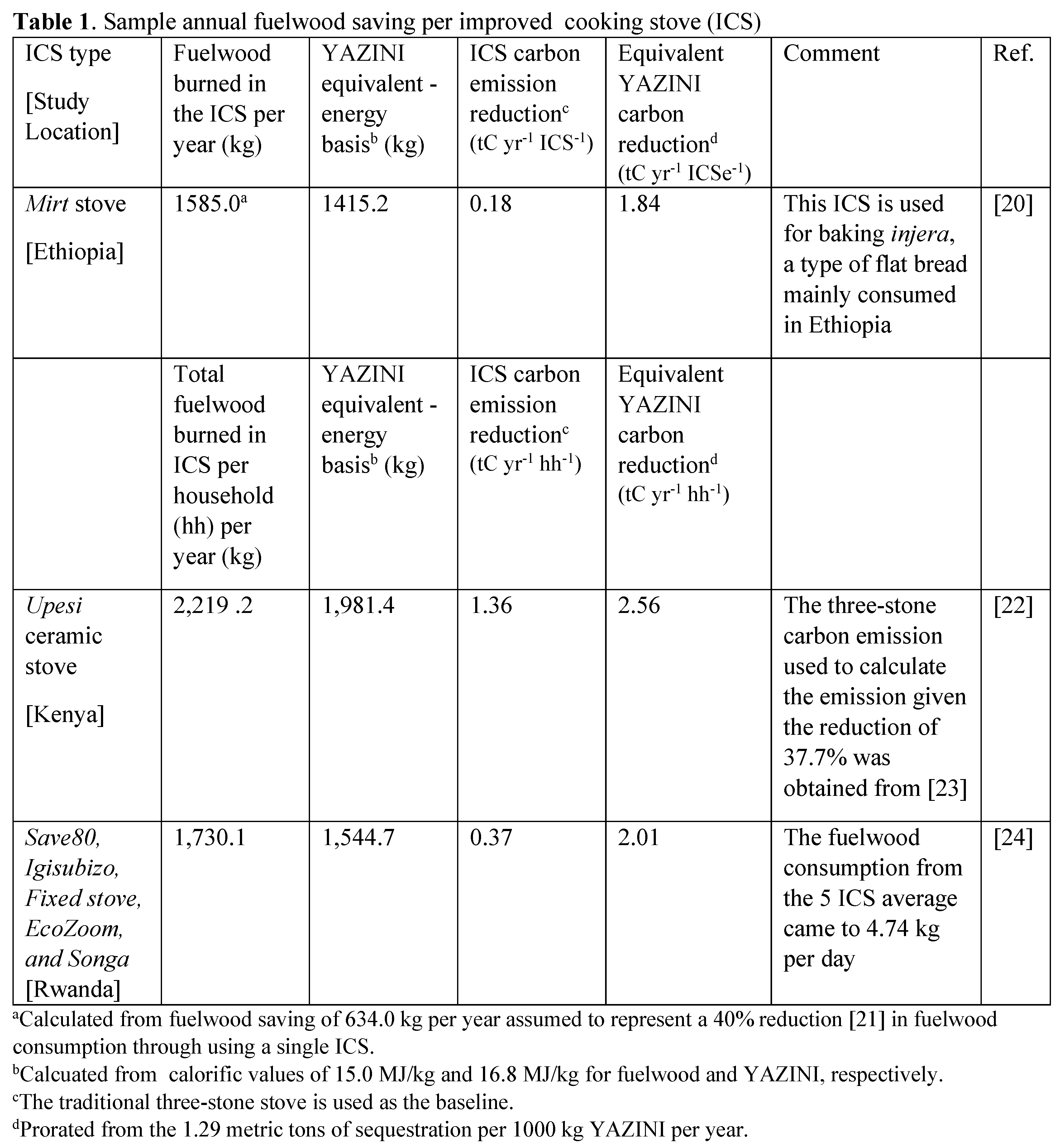

3.10. Cooking/Combustion with/of YAZINI Firewood (Bucket 10)

4. Discussion

|

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C EPA hh ICS IPCC |

Carbon Environmental Protection Agency house hold Improved Cook Stoves Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

References

- A Private Sector Foundation (2020). Uganda Clean Cooking Supply Chain Expansion Project: Market Survey on Institutional Cooking in Uganda, page 7, 2020. The report is not publicly available; a copy was obtained from Geoffrey Ssebuggwawo (gssebuggwawo@psfuganda.org.ug) of Private Sector Foundation.

- Rose, J.; Bensch, G.; Munyehirwe, A.; Peters, J. The forgotten coal: Charcoal demand in sub-Saharan Africa, World Development Perspectives 2022, 25, 100401. [CrossRef]

- Kisaalita, W.S.; Galiwango, J.; Karama, J.J.; Namutosi, W.; Katono, I.W.; Kalanzi, M. (2024). Densified briquette (YAZINI) characterization: Toward a bamboo-based energy value-chain in Uganda. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (In preparation).

- Nath, A.J.; Das, G.; Das, A.K. Above ground standing biomass and carbon storage in village bamboos in North East India. Biomass and Bioenergy 2009, 33, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nfornkah, B.N.; Kaam, R.; Martin, T.; Louis, S.; Cedric, C.D.; Forje, G.W.; Delanot, T.A.; Rosine, T.M.; Baurel, A.J.; Loic, T.; Herman, Z.T.G.; Yves, K.; Varten, D.S. Culm allometry and carbon storage capacity of Bambusa Vulgaris Schrad. ex J.C. Wendel. in the tropical evergreen rain forest of Cameroon. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 2021, 40, 622–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, E.R.; Mesenbring, E.C.; Agao, D.; Alirigia, R.; Begay, T.; Moro, A.; Oduro, A.; Brown, Z.; Dickinson, K.L.; Hannigan, M.P. A glimpse into real-world kitchens: Improving our understanding of cookstove usage through in-field photo-observations and improved cooking event detection (CookED) analytics. Development Engineering 2021, 6, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.; Ryan, C.M.; Williams, M.; Powell, P.; Goodman, L.; Tipper, R. A pilot project to store carbon as biomass in African woodlands. Carbon Management 2010, 1, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankun, W.; Hong, C.; Rong, Z.; Liu Xing’e, L.; Durai, J. (2019). Properties of East African Bamboo: The Physical, Mechanical, Chemical and Fibre Test Results of Three East African Bamboo Species. INBAR Working Paper No. 81. Title of Site. Available online: URL (accessed on June 5, 2025).

- Kaam, R.; Tchamba, M.; Nfornkah, B.N.; Djomo, C.C. Allometric equations and carbon stocks assessment for Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J.C. Wendl. in the bimodal rainfall forest of Cameroon. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu-Poku, A.; Obeng, G.Y.; Mensah, E.; Kwaku, M.; Acheampong, N.; Duah-Gyamfi, A.; Adu-Bredu, S. Assessment of aboveground, below ground, and total biomass carbon storage potential of Bambusa vulgaris in tropical moist forest in Ghana, West Africa. Renewable Energy and Environmental Sustainability 2023, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, M.; Assan, F.; Dadzie, P.K. Aboveground biomass storage and fuel values of Bambusa vulgaris, Oxynanteria abyssinica and Bambusa vulgaris var. vitata plantations in the Bobiri forest reserve of Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 2020, 39, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Gbalaa, F.N.; Guéib, A.M.; Tondoha, J.E. Carbon stocks in selected tree plantations, as compared with semi-deciduous forests in central-west Côte d’Ivoire. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 2017, 239, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Hou, H.; Taudes, A. (2013). Carbon trading system for road freight transport: the impact of government regulation. Advances in Transportation Studies an International Journal, Special Issue, 49–60. http://worldcat.org/issn/18245463.

- Pantoja-Gallegos, J.L.; Dominguez Vergara, N.; Dominguez-Perez, D.N. Calculation of the fuel consumption, fuel economy and carbon dioxide emissions of a heavy-duty vehicle. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemical Transport Association. (2011). Guidelines for Measuring and Managing CO2 Emission from Freight Transport Operations. https://www.ecta.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ECTA-CEFIC-GUIDELINE-FOR-MEASURING-AND-MANAGING-CO2-ISSUE-1.pdf.

- Piecyk, M.I.; Mckinnon, A.C. Forecasting the carbon footprint of road freight transport in 2020. International Journal of Production Economics 2020, 128, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokye, R.; Kalong, R.M.; Bakar, E.S.; Ratnasingam, J.; Jawaid, M.; Awang, K.B. Variations in moisture content affect the shrinkage of Gigantochloa scortechinii and Bambusa vulgaris at different heights of the bamboo culm. BioResources 2014, 9, 7484–7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, P.; Aguiar, C.; Labbe, N.; Commandre, J.-M. Enhancing the combustible properties of bamboo by torrefaction. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 8225–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafalew, A.; Soromessa, T.; Demisew, S.; Belina, M. Validation of allometric models for Sele-Noni Forest in Ethiopia. Modelling Earth Systems and Environment 2023, 9, 2239–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.; Beyene, A.; Bluffstone, R.; Gebreegziabher, Z. Martinsson, P.; Toman, M.; Vieider, F. Ecological Economics 2022, 198, 107467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresen, E.; DeVries, B.; Herod, M.; Verchot, L.; Müller, R. Fuelwood savings and carbon emission reduction by the use of improved cooking stoves in an Afromontane Forest, Ethiopia Land. 2014, 3, 1137–1157. [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.A.; Espira, A. A large-scale, village-level test of wood consumption patterns in a modified traditional cook stove in Kenya. Energy for Sustainable Development 2019, 49, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, R.; Ezzati, M.; Kammen, D.M. Greenhouse gas implications of household energy technology in Kenya. Environmental Science and Technology 2003, 37, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwizeyimana, V.; Mutert, M.; Mbonigaba, T.; Niyonshuti, A.; Nkurikiye, J.B.; Nsabuwera, V.; Peters, J.; Ruticumugambi, J.A.; Gatesi, J.; Mukuralinda, A.; Verbist, B.; Muys, B. Assessment of the efficiency of improved cooking stoves and their impact in reducing forest degradation and contaminant emissions in Eastern Rwanda. Energy for Sustainable Development 2024, 80, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).