1. Introduction

The reliance on wood fuels as a primary energy source in rural areas of developing nations presents considerable environmental and health challenges. This practice of using wood for heating contributes to deforestation, biodiversity loss and forest degradation, just as traditional methods of burning wood exacerbate GHG emissions and air pollution [

1,

2]. The situation is particularly concerning in Sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest proportion of its population dependent on wood-based biomass for cooking compared to transition and developed regions [

3]. The detrimental impact of this issue is evidenced by the daily consumption of approximately 5 kg of firewood per household, which adversely affects soil fertility and local food systems[

4]. While the necessity for household energy, primarily for cooking food and other essential activities, is emphasized, alternative energy sources remain limited. Despite the availability of cleaner alternatives, their uptake remains limited, and projections show that biomass use will continue to increase over the next few decades [

5,

6]. In this context, a holistic approach is emphasized, balancing energy requirements with sustainable forest management practices. In particular, to redefine the role of seasonal and rural entrepreneurs whose businesses depend on the extraction of natural resources and agricultural products. These actors are considered because they can play a role in clean solutions for reducing emissions and moving towards more sustainable practices.

Rural entrepreneurship in developing countries is essentially about the capacity of individuals to increase the value of local natural resources, such as beekeeping, handicrafts, charcoal production, wood processing and, in addition to small-scale farming, fisheries[

7]. Rural businesses therefore have the charisma to lead the initiative on natural resources sustainability, especially around forest restoration in resource-rich areas. It can be considered desirable that rural entrepreneurs also align themselves with wider sustainability frameworks by incorporating economic, social and environmental considerations into their rural business practices. Rural areas in both developed and developing countries are vital agricultural hubs that feed and support cities [

8,

9]. But there is a striking contrast: developed countries, like the EU, are aging. For example, Finland, Italy and Germany are all seeing their rural population decline, leading to large areas of empty land, which threatens the viability of rural economies especially agriculture [

10]. Regarding rural agriculture, the study conducted in Finland highlights concerns at both local and policy levels pertaining to agri-environmental issues[

11].

In this context, it can be observed that the decline of rural regions appears to favor the preservation of natural forests, particularly in terms of carbon sequestration. The disappearance of rural economies, driven by shrinking populations and declining agricultural production, presents a significant challenge. Conversely, developing countries have experienced a notable increase in rural populations, thereby continuing to depend on human resources to sustain local economies and rural livelihoods [

12]. However, in many of these countries, a substantial portion of rural inhabitants still heavily rely on wood burning for domestic purposes, such as cooking. While this practice provides immediate relief, it also contributes to increased CO2 emissions, which pose significant health risks, especially to children [

13]. The literature on grand challenges, such as these [

14,

15], emphasizes the necessity of a coherent and coordinated approach among stakeholders to enhance resource management sustainably and promote cleaner solutions. Supporting both seasonal and permanent rural enterprises can thus aid in forest conservation, promote rural sustainability, and facilitate the development of environmentally sound alternative fuels. Furthermore, clean energy technologies, including solar, wind energy, and biogas-based clean cooking appliances, offer transformative solutions for reducing various forms of greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating air pollution. This rationale is supported by climate mitigation literature [

16,

17,

18,

19], as the use of wood, agricultural residues, and animal waste has long been associated with environmental degradation.

In response to these challenges, this research examines the barriers to sustainable forest management through a case study of rural communities in Zambia where forest-based livelihoods are a key livelihood. The terms community and village are used interchangeably in this study. The aim of this study, using qualitative research methods, is to identify the main barriers to the uptake of clean technologies and to address environmental concerns that prevent the transition from wood to low-emission alternatives. The study aims to assess the potential of clean energy technologies to reduce methane and greenhouse gas emissions while promoting long-term sustainability. Drawing on extensive fieldwork in cooperation with an international organization, the study uses data collected from 2016 - updated in 2020 - in connection with the Tanganyika Lake Tanganyika Sustainable Development Project [

20]. Given that interventions in sustainable development are carried out through various initiatives around the world, this was a major reason for the choice of this acronym. This provides a comprehensive picture of the interface between technological adoption, environmental protection and livelihoods. Moreover, policy-driven mitigation strategies can play a key role in promoting sustainability, promoting the development of clean energy technologies and encouraging the involvement of the private sector in responsible forest management.

As the global community confronts the pressing challenge of sustainable resource utilization, it is imperative to empower rural populations to devise strategies that harmonize economic development with environmental conservation. This study underscores not only the multifaceted nature of transitioning to clean energy but also the critical need for innovative policy frameworks, financial investments, and community-driven initiatives. By bridging the gap between technology viability and practical implementation, this research aims to promote a future in which rural areas can thrive without compromising environmental health, especially in relation to forest ecosystems. The subsequent sections will delve into these challenges in greater depth and investigate practical strategies to expedite the shift to cleaner energy in rural locales, using the context study on communities in Mpulungu district in Northern Zambia.

1.1. Description of the Study Site in Rural Zambia

Mpulungu, located in northern Zambia, is a rural district with a population of 153,564, as recorded in the 2022 Zambian census. This district is notable for its rich biodiversity, which includes extensive forested areas and the vast Lake Tanganyika. The lake is a vital source of fish, while the surrounding forests provide essential wood and fuel for household energy requirements [

20]. However, the challenge of aligning forest supply with the demand for wood fuel consumption presents a significant sustainability issue and hinders efforts to reduce emissions. In a study by Phiri et al. (2019), Zambia's forest cover, which accounts for 66.5 percent of the country's total land area, is rapidly diminishing. Similarly to what was noted in [

22], the country experienced a 6.3 percent decline in forest cover from the 1990s onwards, which amounted to 3.332 million ha. This deforestation rate, averaging 166,600 hectares annually or 0.32 percent, places Zambia among the developing countries most affected by forest loss. The primary causes of deforestation in Africa, particularly relevant to Mpulungu, are logging, firewood and charcoal production. However, there remains a limited comprehension among rural communities, particularly among rural entrepreneurs, concerning their roles and anticipated contributions to sustainable forest management, as well as the obstacles they face in implementing clean technologies to reduce emissions.

2. Research Method

The study used qualitative data collection methods to examine in detail the challenges of sustainable forest management, particularly forest management strategies and emissions in rural Zambia. The survey, carried out in four rural villages, gathered qualitative data through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions and direct observation. This approach has allowed a thorough examination of local knowledge, household wood-fuel collection activities and forest management practices, building on previous and additional studies [

5,

20,

23].

2.1. Data Collection

In 2016, I participated in a local sustainable development initiative at Lake Tanganyika, working under a short-term contract. This project received international funding from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in partnership with the Government of Zambia[

20]. The main aim of the project was to empower local communities with strategies for sustainability. Following this, I conducted a field mission to four rural communities where the project was operational. These communities were chosen based on factors such as road accessibility, the size of the village, and the willingness of local leaders to allow their residents to engage in focus group interviews. The sample included 303 individuals, excluding children aged 10 to 12, whose views on environmental issues were also considered. Discussions at a higher level involved community leaders from the four communities. These communities, located on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, depend on the lake for fishing and the surrounding natural forests. The initial data collection took place in 2016, with the most recent findings and report completed in 2024, that include[

24]. This data collection effort lasted approximately two weeks and covered all four villages situated in remote areas surrounded by natural forest cover. A comprehensive data profile of the interview participants is available in

Table 1.

A cohort of 303 individuals, identified from registered participants, took part in focus group discussions held across four distinct communities in the remote areas of Mpulungu. While the data profile for this study does not include the number of households, an estimation can be made by assuming an average household size of approximately five individuals.

The consolidation of datasets from four separate villages allowed for triangulation, thereby strengthening the validity and reliability of the study's results. This research, centered on rural Zambia, offers valuable insights into the distinct perspectives on forest consumption and emissions in the context of climate change. The study is deeply embedded in the characteristics of rural environments in developing countries, with the aim of aligning rural livelihoods and entrepreneurship with environmental sustainability. Through purposive sampling, the study selected community participants, including experts from the forestry, agriculture, and fisheries departments who functioned as field officers in the villages, as well as representatives from private sector entities involved in forestry and related industries. This approach facilitated a thorough understanding of the diverse perspectives and interests that shape forest management practices in the region. The subsequent qualitative data analysis utilized thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns related to the challenges and opportunities for sustainable forest management.

2.1. Data Analysis: Impact of Climate Change and GHG Emissions

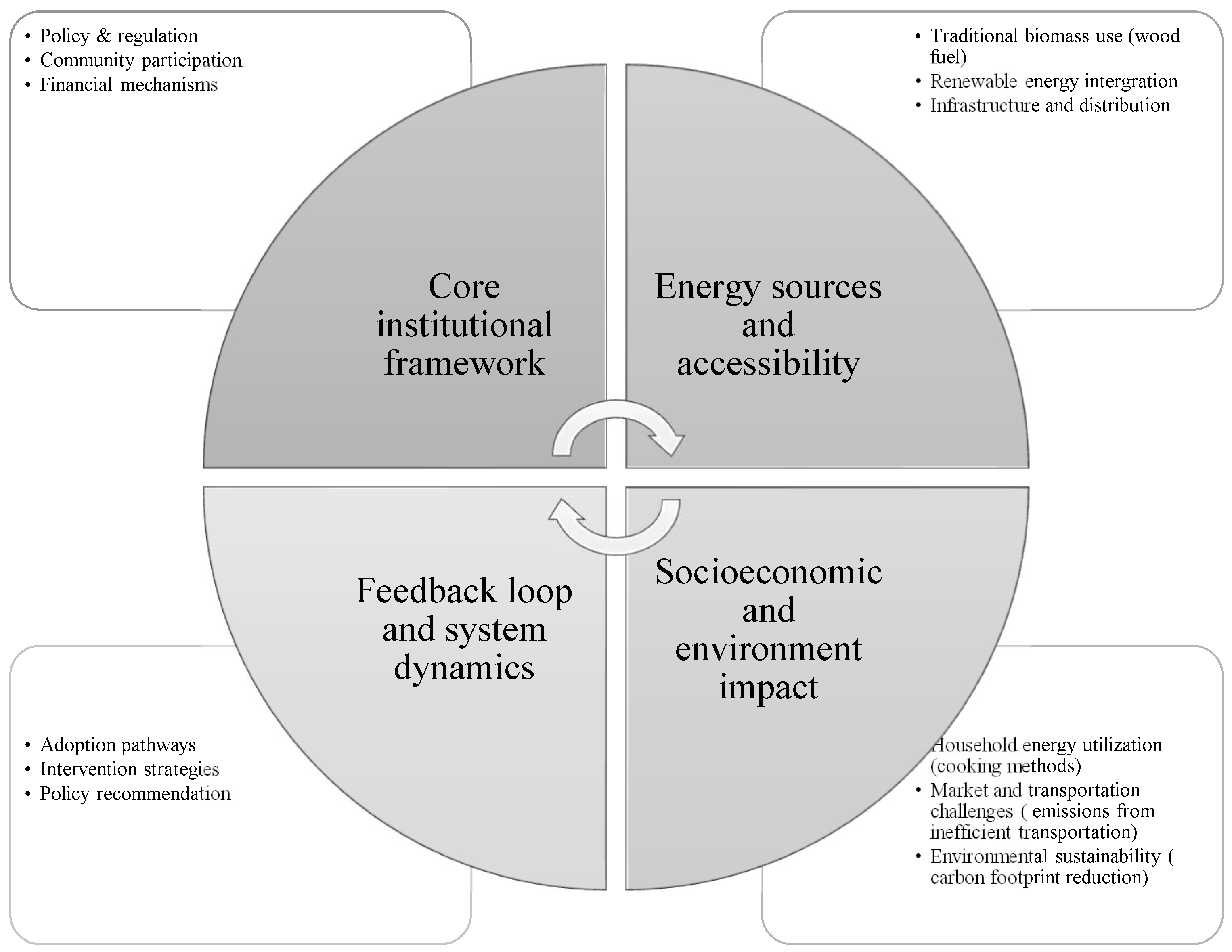

The analysis employs an empirical interpretation to develop a novel institutional model specifically designed for rural energy systems [

25,

26]. This model encapsulates the fundamental processes that define energy accessibility, resource distribution, and governance in rural settings. By systematically examining these mechanisms, key structural patterns influencing energy adoption, sustainability, and economic integration were identified. The approach aims to provide a framework that reflects existing rural energy challenges and offers actionable insights for enhancing institutional efficiency and policy implementation as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The impetus for this research into rural energy use and its environmental repercussions is rooted in a limited understanding of the role rural communities, especially rural entrepreneurs, play in sustainable forest management and emission reduction. Human activities impacting forests, such as forest cultivation, wood fuel consumption, and charcoal production, are significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions[

5,

27,

28]. Understanding the connection between rural energy consumption and its environmental impacts is crucial for tackling climate change issues. This study, therefore, examines the effects of traditional biomass fuels, including charcoal and firewood, on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and environmental degradation. In light of the geographically dispersed nature of settlements, the impact of restricted market access and transportation inefficiencies on the escalation of carbon emissions are considered too. Utilizing an empirical approach, the study reveals significant patterns that influence energy consumption in rural environments, emphasizing the critical need for sustainable energy solutions. The adoption of the institutional model previously described aids in the development of policies, technological progress, and community involvement, all of which are essential for fostering sustainable energy solutions in rural areas and reducing environmental damage.

2.1.1. Dominant Energy Sources in Rural Areas: Charcoal, Firewood, and Solar

In rural areas, energy consumption is largely dictated by the use of traditional biomass fuels and the gradual introduction of renewable alternatives[

16]. Charcoal and firewood are the predominant energy sources, favored for their accessibility and cost-effectiveness, especially among economically disadvantaged households. For example, the felling of trees for heating purposes are extracted from forests in the vicinity of settlements. The production of charcoal, which serves both domestic and commercial needs, exacerbates environmental issues such as deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions. Firewood, a staple for cooking, is typically sourced from nearby forests, placing additional pressure on local ecosystems. Although improved cookstoves offer a viable solution to decrease wood usage and emissions, their widespread adoption is hampered by several factors such availability, insufficient training and limited access to necessary technology[

29]. Conversely, solar energy offers a promising sustainable option but is not widely adopted due to significant initial investment costs and infrastructural challenges.

Charcoal production is a widespread practice, with many households relying on it for both income and energy requirements. The process of obtaining raw materials for energy conversion typically involves the cutting down of trees in open forests. Despite governmental efforts to conserve certain forest areas, charcoal production continues to contribute to deforestation, thereby reducing the capacity of carbon sinks to absorb atmospheric CO₂[

5]. At present, there is a scarcity of research focused on assessing the carbon footprint of charcoal burning[

6]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore sustainable energy alternatives, such as the adoption of improved stoves or the expansion of solar energy access. The limited availability of solar power and other renewable energy sources highlights a significant opportunity for research into sustainable household energy solutions. Furthermore, the alteration in rainfall patterns and the rise in temperatures, which are indicative of climate change, are of considerable concern. In this context, it is essential to examine the connections between these climatic changes and local greenhouse gas emissions to develop long-term solutions for natural resource management. In view of community-based climate adaptation strategies, reducing future emissions and enhancing resilience is emphasised.

2.1.2. Seasonal Entrepreneurship and Environmental Impact in Rural Resource Management

Natural resource systems, which include fish, trees, land, wildlife, and livestock, are vital to the sustenance of rural communities. These resources not only support the daily lives of inhabitants but also underpin local economic development. In a similar vein, small-scale agriculture provides a variety of essential food crops, such as maize, cassava, beans, and groundnuts, although yields can differ significantly between villages. Fishing also contributes substantially to nutritional needs and culinary traditions. The notion of a "seasonal entrepreneur" arises from these practices, describing individuals within the community who participate in rain-fed agriculture and fishing during specific seasons. However, certain farming techniques, such as slash-and-burn, are associated with the release of CO₂ and methane. Furthermore, the application of fertilizers and the practice of livestock farming contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, particularly nitrous oxide and methane. There is considerable scholarly discourse on how climate-smart agricultural practices and soil conservation methods can effectively reduce these emissions[

30,

31].

Fish serve as a crucial source of nutrition and livelihood. The effects of climate change and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on aquatic ecosystems are substantial, posing significant challenges for the sustainable management of fisheries. Increasing temperatures, ocean acidification, and alterations in water chemistry are impacting fish population dynamics, resulting in species migration and threatening biodiversity. Overfishing exacerbates these issues by depleting fish stocks more rapidly than ecosystems can naturally replenish them, thereby destabilizing marine food webs and diminishing the resilience of fish populations. Concurrently, fish entrepreneurs, ranging from small-scale fishers to large commercial enterprises, play a critical role in balancing economic viability with sustainability initiatives. Although economic incentives often drive expansion, there is a persistent tension between short-term profitability and the necessity for long-term resource conservation. To effectively address these challenges, it is imperative for adaptive fisheries policies to incorporate climate-responsive strategies and responsible business practices, fostering a market environment where sustainability and profitability can coexist, thereby ensuring the enduring availability of marine resources.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of these diverse perspectives, the subsequent section presents findings based on empirical analyses.

3. Results and Findings

Building upon empirical analyses that informed the development of the institutional model for rural energy systems, this section elucidates key data insights concerning greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, methane dynamics, and the role of rural entrepreneurs in the utilization of forest resources. The tables presented herein delineate critical socio-economic and environmental factors, including household energy consumption patterns, emissions resulting from the use of wood fuels, and the contribution of methane from agricultural and waste management practices, particularly those related to livestock dung. Furthermore, the business sector plays a pivotal role in shaping resource demand, as local enterprises drive fuel consumption, land management, and innovation in energy solutions. While these enterprises contribute to economic growth, their collective decisions significantly impact carbon footprints and environmental sustainability. Interpretation of these data points reveals trends that underscore both the challenges and opportunities associated with reducing emissions while promoting sustainable business models. These findings provide a foundation for assessing existing mitigation strategies and for identifying pathways forward for climate-smart business and energy policy.

In rural regions, energy consumption is predominantly reliant on traditional biomass fuels, such as charcoal and firewood. Charcoal production not only meets household energy demands but also provides a vital source of income for economically disadvantaged families. Firewood, commonly used for cooking, is typically sourced from nearby forests. This dependency raises significant environmental concerns, including deforestation and ecosystem degradation. Although improved cookstoves have been introduced in some communities to reduce wood consumption, their widespread adoption is limited by a lack of training in stove-making techniques. Solar energy emerges as a promising sustainable alternative; however, its adoption in rural areas is hindered by substantial barriers, including high initial costs, limited access to solar technologies, and insufficient awareness of solar energy benefits. Overcoming these challenges and promoting sustainable energy use in rural areas requires a comprehensive approach. This approach should encompass financial incentives, policy interventions, localized training programs, awareness campaigns, public-private partnerships, and investment in research and development of cost-effective and culturally appropriate solar solutions tailored to rural contexts. Equally, transportation is included regarding mode of transportation and its emissions.

Table 2 shows the data collected on rural energy use through community-led discussions, which focused on everyday life issues of access to wood monthly.

To deepen our understanding of CO₂ emissions as presented in

Table 2, particularly those arising from the use of wood and charcoal, we utilized estimated conversion factors derived from established sources [

3,

32]. Based on this approach, the estimated CO₂ emissions were calculated using the following methodology:

Where:

To clarify the methodology of this calculation, let us examine the firewood emission factor, which is quantified as 1.5 kg of CO2 per kilogram of firewood. Each bundle comprises 10 kilograms of firewood, and the monthly consumption amounts to 30 bundles:

While the application of this method shows considerable diversity across various countries in the region, related research has identified comparable strategies [

33,

34,

35]. For the calculations referenced above, the standard methods were obtained from Forest Research guidelines in the United Kingdom, which examines carbon emissions from different fuel types (forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources).

Another important carbon emission aspect is that access to rural markets is severely constrained by the lack of road infrastructure, which hampers the efficient movement of goods. This dependence on old and inefficient transport methods not only reduces economic productivity but also exacerbates carbon leakage. Evaluating the environmental impact of existing transport systems is essential for finding sustainable solutions. Investing in environmentally friendly transport options such as better road networks, electric vehicles or community-based transport cooperatives could reduce the environmental impact while promoting economic growth. Overview of

Table 3, the focus groups were asked about their sources of income, general livelihoods and sustainable practices that they had experienced or adopted in their community.

The findings show that farming was common in most households, but that they were also committed to implementing sustainable practices. Meanwhile, the uptake of clean energy by a significant proportion of communities has been limited by the availability of solar energy and other renewable energy sources. The aim of this section was to understand the barriers to solar energy adoption, such as high upfront investment, limited funding opportunities and insufficient awareness of the benefits of the technology, in order to develop effective policy and intervention strategies. As indicated in

Table 4, these users expressed their knowledge of solar energy, since some households installed small solar panels to illuminate and charge their phones. However, the high costs of obtaining solar energy were significant and reflected in the high average price of solar electricity.

These findings highlight the delicate balance between forest protection initiatives and the continued dependence of rural Zambia on wood fuels as its primary energy source. While sustainable forestry seeks to preserve the integrity of the environment, the continued demand for biomass fuels exacerbates deforestation and contributes to carbon emissions and environmental degradation. Rural households, limited in access to clean energy alternatives, are caught in a vicious circle of unsustainable energy consumption. Although new technologies and policy interventions offer ways to move towards cleaner energy transitions, the effectiveness of these solutions remains mixed, especially in mitigating methane and other greenhouse gases. This complex reality underlines the urgent need for innovative emission monitoring mechanisms, adaptive policy frameworks and economic incentives to reconcile forest conservation with rural security. The interaction between environmental sustainability and socio-economic imperatives requires a holistic approach, combining community-based solutions, technological progress and regulatory mechanisms to create viable paths to a low carbon rural economy. These findings pave the way for a forthcoming debate on the structural and political dimensions needed to integrate sustainable energy models into rural livelihoods.

3.1. Community Perspectives on Poverty

Poverty is often conceptualized through global metrics, such as the United Nations' definition of extreme poverty, which identifies individuals living on less than

$1.90 per day, affecting over 700 million people worldwide [

36]. While this standardized metric is widely acknowledged, the reality in Mpulungu's rural communities offers a contrasting viewpoint. Survey results indicate that residents do not define poverty solely by financial income; instead, they assess household wealth based on material assets and economic stability within their local context. When asked, (a) What defines a wealthy household? (b) What defines a poor household? -- responses highlighted a community-specific scale of wealth evaluation. In Mpulungu, a wealthy household is characterized by the possession of significant household items—such as houses with iron sheet roofing, beds, sofas, and kitchen cabinets—alongside bicycle or motorcycles, and entrepreneurial endeavors like timber trade.

Land ownership is another sign of affluence, with larger cultivated farms and herds of cattle a sign of prosperity. On the contrary, poorer households are defined by their lack of sufficient food security. In this respect, a person or household who is undernourished or can afford only a small amount of food per day is considered poor. Also included in this category are dependence on manual labor for a living and dwellings made of grass-based materials with limited resources. This localized understanding challenges external assumptions about poverty and highlights the importance of livelihoods and access to resources rather than just financial returns. Recognition of these alternative poverty indicators is crucial to designing policies and interventions that resonate with the lived experience of rural communities rather than imposing universal standards. This revelation clearly explains that rural communities are agrarian and pass on for generations, with most of them living in harmony with the natural environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Rural Energy Use and Its Environmental Impact

Rural regions, characterized by their abundance of forests, farmland, and other natural resources, present significant opportunities for climate change mitigation through effective resource management. As primarily agricultural areas, they are integral to both adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change, thereby playing a crucial role in global sustainability initiatives. However, these rural landscapes are influenced by distinct socio-economic dynamics, environmental challenges, and land-use patterns that distinguish them from urban environments. While rural communities depend heavily on forests and natural resources for their livelihoods, there is a pronounced disparity in energy accessibility between developed and developing regions. This disparity highlights the issue of energy poverty, with over 40% of the global population still relying on biomass as their primary energy source [

37].

The findings of this study highlight the significant differences in access to energy in rural areas, where biomass remains the predominant fuel source for more than 40 percent of the world's rural population. In the broader context, the findings clearly highlight that extensive charcoal production and reliance on wood are the main drivers of deforestation and increased carbon emissions in these areas, e.g. [

6,

38]. Although improved biomass stoves offer opportunities for increased energy efficiency, their adoption is hampered by a lack of technical training and accessibility. In addition, rural entrepreneurial activities, including fish trading, agriculture and logging, have a significant impact on natural resource use and methane emissions. Social economic factors such as land tenure, agricultural practices and local entrepreneurial dynamism are key to sustainable energy transition. In order to combat energy poverty effectively, it is essential to implement policies that promote cleaner energy alternatives, provide financial incentives for rural entrepreneurs and provide institutional support for smart energy management.

Rural communities and entrepreneurs have a major impact on energy consumption patterns, which in turn affects the sustainability performance of resource-dependent regions. A significant number of households, together with small farms, fisheries and forestry companies continue to use traditional biomass such as wood and charcoal for their cost effectiveness and availability. However, this dependence worsens deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions, thus exacerbating the climate challenge. Although more and more entrepreneurs in rural areas are exploring cleaner alternatives such as improved stoves, biogas and solar energy, the changeover within households remains uneven, hampered by financial constraints, limited technical knowledge and infrastructure barriers. Tailor-made policies are essential to facilitate wider adoption, not only to encourage sustainable business models, but also to empower households through financial support, training programmes and access to cleaner technologies. Integrating energy efficiency across community and business activities can drive innovation while minimising environmental impact and ultimately support global efforts to mitigate climate change.

Progress towards sustainable development in rural areas depends critically on the integration of inclusive policies and business innovation to promote climate-friendly development. Rural communities, which are at the crossroads of resource dependence and economic expansion, need to move towards cleaner solutions that reconcile environmental protection with livelihoods. Improving institutional frameworks through targeted subsidies, capacity building initiatives and investments in decentralized energy infrastructure can facilitate the uptake of low-emission technologies such as biofuels, advanced biomass and solar energy. Moreover, empowering rural entrepreneurs to lead sustainability initiatives will strengthen resilience and ensure long-term economic viability, enabling local businesses to contribute to reducing emissions and managing resources responsibly. By aligning their energy policies with market-based solutions, rural economies can act as drivers of green innovation, demonstrating that environmental protection and economic prosperity are not mutually exclusive but mutually reinforcing drivers of sustainable development.

4.2. Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Emission Monitoring

Building on the challenges of emissions monitoring and sustainable forestry, new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI)-driven analytics offer promising additions to traditional approaches[

39,

40,

41]. Using machine learning and remote sensing, AI can improve the accuracy of GHG monitoring, providing valuable insights for rural entrepreneurs and policy makers to make informed decisions. In the area of environmental sustainability, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognised as a transformative tool to improve the monitoring of emissions, especially in rural forest settings. Artificial intelligence technologies such as remote sensing and machine learning algorithms make it possible to monitor GHG emissions more precisely and in real time, complementing traditional monitoring techniques, e.g., [

42]. These advanced systems are capable of processing huge data sets, identifying emission trends and predicting environmental changes, providing rural entrepreneurs and policymakers with critical information for strategic decisions. In Zambia's rural areas, in particular, AI-based monitoring systems have the potential to improve the assessment of clean energy uptake and its subsequent impact on the reduction of the carbon footprint. However, the deployment of these technologies is facing obstacles, such as lack of digital infrastructure, limited data availability and financial constraints. Overcoming these challenges by developing support policies and active cooperation between stakeholders could fully realize the potential of AI to promote sustainable forest management.

The dynamic relationship between rural enterprise, sustainable forest management and emission reduction presents both challenges and opportunities for shaping environmental and economic outcomes. The study highlights the crucial role of rural entrepreneurs in promoting the uptake of clean energy and promoting sustainable practices. Despite their importance, these efforts are often hindered by significant obstacles, including technological limitations, political constraints and socio-economic differences. Innovative solutions such as artificial intelligence-based emissions monitoring offer promising opportunities to improve the accuracy of GHG monitoring, thus facilitating more efficient policy making and adaptation strategies. However, successful mainstreaming of artificial intelligence depends on factors such as the readiness of infrastructure, availability of data and financial investment in rural areas. Overcoming these challenges requires a comprehensive approach that combines the use of innovative technologies with efforts to promote local involvement and capacity building. As policymakers, researchers and communities work towards scalable sustainability solutions, it is essential that implementation frameworks are constantly refined and that more in-depth social and economic compromises are explored. The present study contributes to this ongoing debate by underlining the need for an integrated strategy linking business, environmental protection and rural development to further global climate action.

5. Practical Implications

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to reduce GHG emissions and methane production from rural energy systems. The central insight is the strong influence of rural entrepreneurs and communities whose choices influence resource management, energy innovation and emission reduction. By promoting the introduction of cleaner technologies - such as biomass boilers and decentralised renewable energy solutions, such as biogas - businesses can facilitate the transition to more sustainable practices. Moreover, institutional frameworks need to be adapted to support methane capture and carbon offset initiatives, particularly in the agricultural and forestry sectors. These strategies not only improve climate resilience but also strengthen rural economies and promote a climate that reconciles environmental sustainability with entrepreneurship. As rural communities face the challenges of energy transition, it will be crucial to reconcile economic incentives with environmental responsibility in order to create a more sustainable future.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

The study does not disclose the names of individuals who took part in the focus group, therefore their confidentiality was respected.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. Sibanda, S. Takentsi, and D. Gonese, “Energy consumption, technological innovation, and environmental degradation in SADC countries,” Cogent Soc Sci, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. V. Emodi, T. Chaiechi, and A. B. M. R. Alam Beg, “Are emission reduction policies effective under climate change conditions? A backcasting and exploratory scenario approach using the LEAP-OSeMOSYS Model,” Appl Energy, pp. 1183–1217, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. O. Acheampong, J. Dzator, and D. A. Savage, “Renewable energy, CO2 emissions and economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa: Does institutional quality matter?,” J Policy Model, vol. 43, no. 5, pp. 1070–1093, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Amede, A. A. Konde, J. J. Muhinda, and G. Bigirwa, “Sustainable Farming in Practice: Building Resilient and Profitable Smallholder Agricultural Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 5731, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Bamwesigye et al., “Charcoal and wood biomass utilization in uganda: The socioeconomic and environmental dynamics and implications,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 20, pp. 1–18, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Francesconi, M. Vanegas-Cubillos, and V. Bax, “Carbon footprints of forest degradation and deforestation by ‘basic-needs populations’: a review,” Carbon Footprints, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Islas-Moreno, M. Muñoz-Rodríguez, and W. Morris, “Understanding the rural entrepreneurship process: A systematic review of literature,” 2021, Inderscience Publishers. [CrossRef]

- A. Kratzer and J. Kister, Rural-urban linkages for sustainable development, 1st ed. in The dynamics of economic space. Abingdon, Oxon ; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2021.

- M. Yami, S. Feleke, T. Abdoulaye, A. D. Alene, Z. Bamba, and V. Manyong, “African rural youth engagement in agribusiness: Achievements, limitations, and lessons,” Jan. 01, 2019, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- M. Jokela, M. Laakasuo, S. Parikka, A. Rotkirch, and H. Hämäläinen, “Psychological and social wellbeing associated with regional population change in Finland,” J Community Appl Soc Psychol, vol. 34, no. 4, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Åkerman, M. Kaljonen, and T. Peltola, “Integrating environmental policies into local practices: The politics of agri-environmental and energy policies in Rural Finland,” Local Environ, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 595–611, 2005. [CrossRef]

- A. Ezeh, F. Kissling, and P. Singer, “Why sub-Saharan Africa might exceed its projected population size by 2100,” Oct. 17, 2020, Lancet Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- G. Petrokofsky, W. J. Harvey, L. Petrokofsky, and C. A. Ochieng, “The importance of time-saving as a factor in transitioning from woodfuel to modern cooking energy services: A systematic map,” Forests, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1149, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Doh, P. Tashman, and M. H. Benischke, “Adapting to grand environmental challenges through collective entrepreneurship,” in Academy of Management Perspectives, Academy of Management, 2019, pp. 450–468. [CrossRef]

- J. Howard-Grenville, S. J. Buckle, B. J. Hoskins, and G. George, “Climate change and management,” Jun. 01, 2014, Academy of Management. [CrossRef]

- E. Daka, “Adopting Clean Technologies to Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Africa: a Systematic Literature Review,” Environ Manage, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 87–98, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Lundan, “International business and global climate change,” J Int Bus Stud, vol. 42, no. 7, pp. 974–977, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Nyong, F. Adesina, and B. Osman Elasha, “The value of indigenous knowledge in climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the African Sahel,” Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 787–797, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Hosseinzade, H. Jafari, and M. A. Ahmadian, “Rural entrepreneurship and sustainable development towards environmental sustainability (Central Bardaskan City area),” Ukr J Ecol, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 235–245, 2018.

- C. Munshimbwe and F. Ng’andu, “DATA COLLECTION FROM MPULUNGU DISTRICT # Questions Scoping for GEF Project Site, Lake Tanganyika Development Project-Mpulungu District,” 2000.

- D. Phiri, J. Morgenroth, and C. Xu, “Four decades of land cover and forest connectivity study in Zambia—An object-based image analysis approach,” International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation, vol. 79, pp. 97–109, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Mbindo, “Forest cover crisis in the sub-tropics: a case study from Zambia,” XII World Forestry Congress, 2003.

- F. D. Babalola and E. B. Jegede, “Participation of stakeholders in sustainable management of a state-owned forest reserve in kwara state, nigeria,” Revista Produção e Desenvolvimento, vol. 6, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Bangwe, G. Silungwe, and V. I. J. Neeraj, “IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS AND RESULTS REPORT (IPR),” 2022.

- J. W. Creswell, R. Shope, V. L. P. Clark, and D. O. Green, “Spring 2006 How Interpretive Qualitative Research Extends Mixed Methods Research,” 2006.

- P. D. Ellis, “Effect sizes and the interpretation of research results in international business,” J Int Bus Stud, vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 1581–1588, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Bradnum and T. Makonese, “Design and performance evaluation of wood-burning cookstoves for low-income households in South Africa,” Journal of energy in Southern Africa, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pia. Katila and International Union of Forest Research Organizations., Forests under pressure : local responses to global issues. International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO), 2014.

- V. Vigolo, R. Sallaku, and F. Testa, “Drivers and barriers to clean cooking: A systematic literature review from a consumer behavior perspective,” Nov. 21, 2018, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- C. Makate, “Local institutions and indigenous knowledge in adoption and scaling of climate-smart agricultural innovations among sub-Saharan smallholder farmers,” Mar. 09, 2020, Emerald Group Holdings Ltd. [CrossRef]

- C. V. O. Abegunde, M. Sibanda, and A. Obi, “Determinants of the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices by small-scale farming households in King Cetshwayo district municipality, South Africa,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Dauda et al., “Innovation, trade openness and CO2 emissions in selected countries in Africa,” J Clean Prod, vol. 281, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Appiah, M. Fagg, and A. Pappinen, “A Review of Reforestation Approaches in Ghana: Sustainability and Genuine Local Participation Lessons for Implementing REDD+ Activities,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.europeanjournalofscientificresearch.com.

- D. L. Skole et al., “Direct measurement of forest degradation rates in malawi: Toward a national forest monitoring system to support redd,” Forests, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 426, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Banda, C. G. Musuka, and L. Haambiya, “Extent of Participation in Co-management on Lake Tanganyika, Zambia,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.openscienceonline.com/journal/ijaff.

- A. Addae-Korankye, “Causes of Poverty in Africa: A Review of Literature,” 2014. [Online]. Available: www.aijssnet.com.

- Y.-S. Ren, X. Kuang, and T. Klein, “Does the urban–rural income gap matter for rural energy poverty?,” Energy Policy, vol. 186, p. 113977, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Kokko, “Local forest governance and benefit sharing from reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) : case,” 2010. [Online]. Available: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se.

- M. SaberiKamarposhti, K.-W. Ng, M. Yadollahi, H. Kamyab, J. Cheng, and M. Khorami, “Cultivating a sustainable future in the artificial intelligence era: A comprehensive assessment of greenhouse gas emissions and removals in agriculture,” Environ Res, vol. 250, p. 118528, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, A. Nabavi-Pelesaraei, and S. Shamshirband, “Investigations of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions of fattening farms using artificial intelligence methods,” Environ Prog Sustain Energy, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 1546–1559, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Hashemi, Sustainable Integrated Clean Environment for Human & Nature. Basel, Switzerland: MDPI - Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2021.

- A. Hammond and P. J. Keleher, Remote Sensing. London: IntechOpen, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).