1. Introduction

Forests harbor significant biodiversity that is crucial for ecosystem functioning [

1]. They are essential to humanity and ecological balance, serving as reservoirs of carbon and biodiversity while providing vital resources, including fuelwood, which is indispensable to many populations [

2,

3]. In addition to fuelwood, these ecosystems supply non-timber forest products such as caterpillars, fruits, and mushrooms, which contribute to food security and household incomes [

4]. Among these resources, charcoal is a widely used fuel in sub-Saharan Africa, where it constitutes the primary source of domestic energy [

5,

6]. Approximately 195 million people rely on charcoal as their main energy source, while 200 million use it as a secondary source [

7].

In most cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo), charcoal dominates the fuelwood sector. For instance, its consumption is widespread in Kisangani [

8] and reaches extremely high levels in other cities: 98% in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi [

9,

10], 99% in Goma, and 97% in Bukavu [

11,

12]. However, charcoal production suffers from low efficiency due to the predominant use of traditional earth kilns [

13]. The efficiency of these kilns varies from 10% in Lubumbashi [

14,

15], to 12.8% in the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve and 28.1% on the Batéké Plateau [

16]. Some improved techniques, such as those used by agroforestry practitioners in Mampu, achieve yields of approximately 20% [

17]. The low efficiency of charcoal production exacerbates deforestation, even though DR Congo is home to nearly 60% of the forests in the Congo Basin [

3,

18]. Dependence on charcoal poses a major challenge to sustainable forest management. This issue is further aggravated by the lack of sustainable energy alternatives, the prevalence of slash-and-burn agriculture, and small-scale logging [

19,

20].

Deforestation has particularly affected the Miombo forest in the Lubumbashi region due to human activities, notably charcoal production [

21,

22,

23]. The supply of charcoal to urban areas is becoming increasingly complex as forest cover declines. For instance, Lubumbashi’s supply basin lost more than half of its forested area between 1990 (77.90%) and 2022 (39.92%), gradually being converted into wooded savannas, grasslands, or agricultural lands [

23]. As a result, charcoal extraction is shifting farther from the city, with production volumes increasing as the distance traveled grows, highlighting the severity of deforestation driven by this activity [

22].

Despite its negative environmental impact, charcoal remains an important economic driver, generating income throughout its supply chain [

16,

24]. In Lubumbashi, the charcoal sector produces an estimated annual added value of

$50 million, with 59% originating from production, while wholesale and retail sales account for 17% and 16%, respectively [

10]. For charcoal producers, this income covers 80% of their household expenses [

25]. However, the profitability of charcoal production and trade is undermined by several constraints, including high taxation, deteriorated transportation infrastructure [

14,

26,

27], and significant labor costs, all of which impact the earnings of charcoal producers [

28,

29].

A better understanding of the interactions between various economic parameters is essential for improving the management of this sector. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze the factors influencing profitability, such as selling price, transportation and tax costs, and labor remuneration, to develop appropriate policies. Several studies have been conducted on charcoal supply in Lubumbashi, including research on the charcoal supply chain in Lubumbashi and Kinshasa [

26], as well as studies by [

14] and [

30], which examine charcoal supply in Lubumbashi and the value added through value chain analysis. However, none of these studies have focused on the profit optimization strategies employed by sector stakeholders. Moreover, the relationship between charcoal production profitability and forest resource conservation remains unexplored. This research is based on the hypothesis of economic rationality, whereby producers make decisions aimed at maximizing their profit while operating within the constraints of available resources and the technical laws of production [

31].

Thus, this study was initiated to analyze the charcoal marketing practices employed by professional charcoal producers in the rural area of Lubumbashi and their impact on financial profitability. The study is based on the following hypotheses: Marketing practices, particularly the diversification of packaging types, sales locations, and the seasonality of charcoal sales, influence the financial profitability of charcoal production in the rural area of Lubumbashi. Households in Lubumbashi prefer purchasing larger charcoal packages, which positively affects the selling price and the profitability of this type of packaging [

27,

32]. Selling price, production and marketing costs, as well as profitability, increase with the distance from the charcoal production site [

33,

34,

35]. Charcoal marketing during the rainy season is more profitable due to the increase in selling prices [

36,

37].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was conducted in the rural area of Lubumbashi, located in the southeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which serves as the primary supply basin for charcoal to the city of Lubumbashi. The area extends up to 150 km around the city [

30]. This region is characterized by a Cwa climate type according to the Köppen classification [

38]. The rural area of Lubumbashi experiences two distinct seasons: a dry season and a rainy season, which lasts from November to March, with average rainfall of approximately 1232 mm. The annual average temperature is 20°C, with temperature variations ranging from a minimum of 8°C to a maximum of 32°C [

39].

The dominant vegetation in the Lubumbashi region is the Miombo woodland [

40]. The soil types characterizing this environment are latosols, composed of red, ochre-red, and yellow soils [

39]. This forest serves as a vital resource for local populations, providing both timber and non-timber forest products essential for their livelihoods [

25]. Rural economic activities primarily include agriculture, charcoal production, fishing, fruit gathering, as well as mushroom and caterpillar harvesting [

39]. Notably, charcoal production represents a significant economic activity in this region, involving multiple stakeholders from diverse backgrounds [

30,

41].

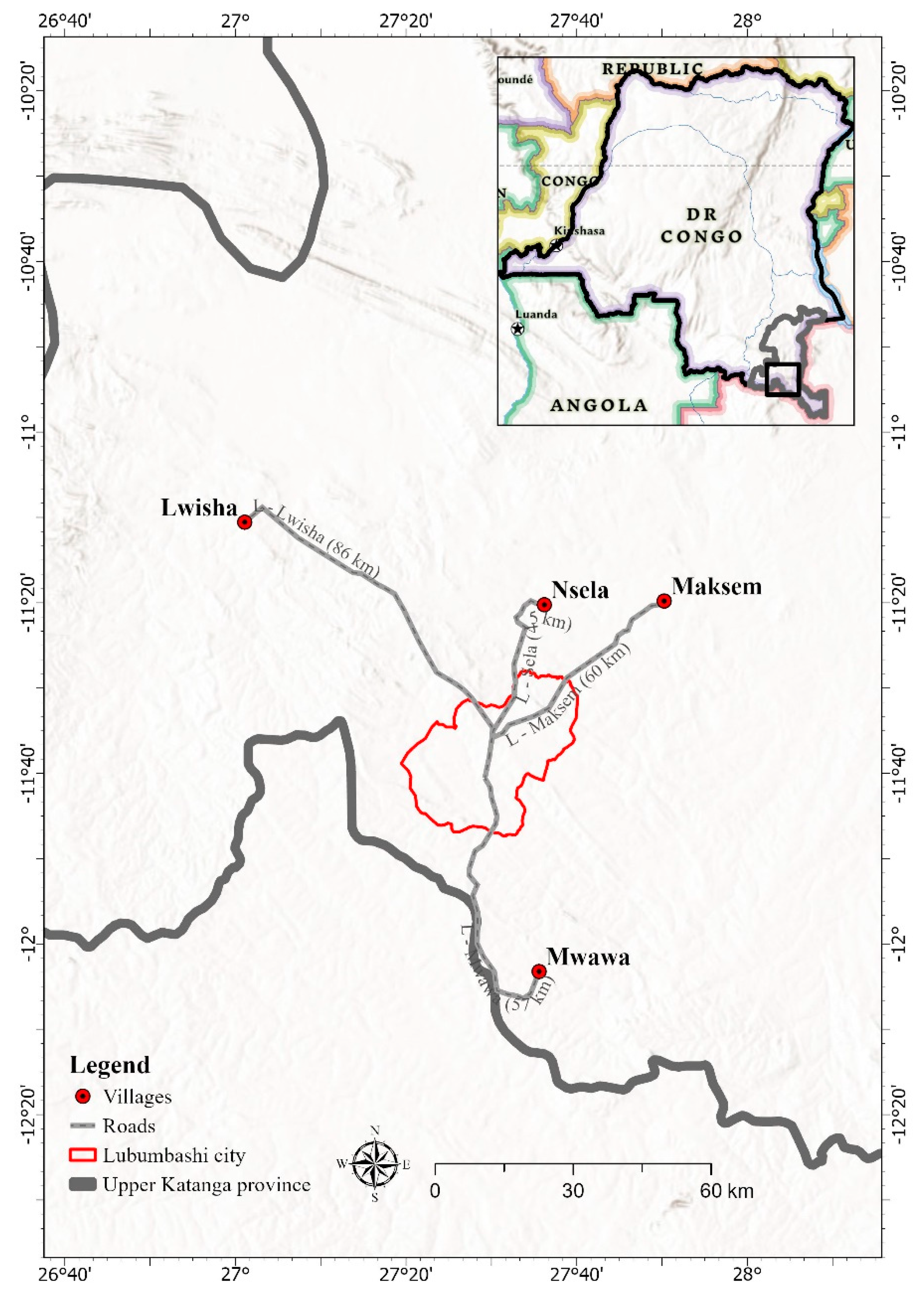

Numerous charcoal-producing villages are established in the rural area of Lubumbashi, including those examined in this study, which are located within an 80 km radius of the city. These villages include Luisha (along the Likasi road), Maksem (on the Kasenga axis), Sela (along the Kinsevere road), and Mwawa (on the Kasumbalesa axis). Among them, Luisha, situated along the Likasi axis, is the farthest from Lubumbashi, with an estimated distance of approximately 86 km (

Figure 1). In addition to forest-related activities, this village is notable for its artisanal mining operations, making it the most densely populated in the area (

Table 1). Mwawa village is located 57 km from the city, while Sela is the closest village, situated 45 km from Lubumbashi. Both villages are primarily characterized by agricultural activities and charcoal production. Lastly, Maksem village, located 60 km from Lubumbashi, is predominantly known for its agricultural activities. Numerous farms in this area have significantly impacted the forest, leading to notable resource degradation and employing various household members as agricultural laborers.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Selection of Villages

The four villages covered in this study were selected following surveys conducted among charcoal vendors at 14 wholesale storage and sales sites in the city of Lubumbashi. The objective of these surveys was to identify the primary sources of the charcoal marketed and consumed in Lubumbashi. Subsequently, exploratory surveys were carried out in 16 villages identified as the main suppliers to the city, as suggested by the vendors at the previously visited storage sites. This investigative phase took place between July 7 and August 7, 2020. The four selected villages stood out due to their high intensity of forest exploitation for charcoal production, particularly evident in the large number of charcoal bags present and the significant influx of resellers from Lubumbashi. Additionally, these villages were accessible and well connected to surrounding villages, creating a spillover effect among them. They were also the most densely populated in their respective areas, as indicated by the number of households in each village (

Table 1).

2.2.2. Sampling

The sampling was carried out in several stages, with the first stage involving the identification of charcoal producers among the household heads in these four villages. The Bernoulli formula [

15,

43,

44] presented below was used to survey 258 household heads distributed across the four villages (Equation 1).

: the sample size; : the acceptable margin of error (set at 10%); : the critical coefficient for a 90% confidence level ; : the population size, corresponding to the total number of households in the villages of this study.

This selection implies that, for this category of producers, charcoal production represents a more significant source of income than for other charcoal producers. The distribution of the producers monitored by village is as follows: 6 charcoal producers in Luisha, 5 in Maksem, 5 in Sela, and 4 in Mwawa. This choice was driven by the variability in the number of household heads across villages, which influenced the distribution of the charcoal-producing population. As a result, a larger number of charcoal producers was selected in Luisha, while a smaller group was chosen in Mwawa, ensuring an appropriate representation for each village context.

2.2.3. Data Collection

Data collection for this study took place from January 4 to September 28, 2022. It involved tracking charcoal producers from the production phase through to the commercialization of their product [

15,

16]. Data were gathered using a pre-designed form, which allowed for the recording of various economic variables, including the selling price, different production costs (labor, packaging), as well as marketing-related costs (transportation, taxes, handling, and storage fees). Additionally, the selling price and the number of bags sold were also documented. Information on marketing strategies was also collected, including the location and season of sale, as well as the types of packaging used.

Data collection was carried out based on the availability of each charcoal producer, with the producers notifying in advance the day and time of their availability. Regarding packaging, four distinct types were identified according to their volume and weight (

Figure 2). The first type, the largest (locally called "3 pas"), had an average weight of 57 kg. The second type ("2 pas") weighed on average 43 kg, while the third type ("1 pas") had an average weight of 36 kg. Finally, the last type, called "kipupu," weighed on average 29 kg. By calculating the arithmetic mean of these four types of sacks, it was determined that a sack of charcoal weighs, on average, 41.3 kg [

14,

30].

2.2.4. Data Analysis

The data collected in the field after tracking the charcoal producers allowed for the necessary statistical analyses for this study. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation of quantitative variables, including selling prices, production costs, and marketing costs. Similarly, proportions were calculated for the study. Statistical inference, through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Student's t-test, enabled us to first compare the means of the quantitative variables. Specifically, ANOVA allowed us to compare the selling price based on the different marketing locations. This analysis highlighted significant differences between the mean selling prices of charcoal depending on the place of transaction, namely the production site, the village of the charcoal producers, and the city of Lubumbashi. Similarly, the Student's t-test enabled us to compare the variation in charcoal prices based on sales seasons.

Profitability assessment was carried out through financial analysis based on economic calculations that allowed for estimating profit, profit margin, and the benefit/cost ratio. The profit analysis provided insight into the level of management among professional charcoal producers in the rural area of Lubumbashi. A negative profit indicates a loss, meaning that the resources mobilized for the operation did not generate sufficient returns to cover the costs incurred [

45,

46].

Thus, profit and profit margin were calculated as follows, as proposed by [

47]. It should be noted that the calculation of profit begins with the calculation of revenue, as presented below:

Where

: Gross Revenue ;

: Number of Bags Sold ;

: Average Selling Price

Where represents : Profit per producer ; : Bags Sold ; : Average Selling Price ; : Transportation Cost ; : Tax Costs ; : Labor Costs ; : Material Costs ; : Access Cost.

Regarding the costs, those related to materials and land access were not considered in this study. Indeed, the calculations were based on a kiln-level analysis, with monitoring of the charcoal makers starting at the tree cutting stage, without including the land acquisition step. Furthermore, the tenure of access to forest resources varies among individuals and periods, complicating the integration of this parameter into the analysis. In this context, the formula from [

47] was adapted as follows:

: Profit per producer ;

: Bags Sold ;

: Average Selling Price ;

: Transportation Costs ;

: Tax Costs ;

: Labor Costs

: Profit Margin ; : Net Profit ; : Revenue

Gross revenue corresponds to the income generated after the sale of charcoal [

48]. The profit calculation was made to determine the amount actually retained by the charcoal makers after the sale, by subtracting all costs associated with the production and marketing process [

10]. The profit margin, on the other hand, serves as an additional economic indicator to revenue and profit. It helps evaluate the profitability level of charcoal sales by determining the share of profit in the total income of producers [

26,

47].

The Benefit/cost ratio was calculated to determine whether the charcoal production activity carried out by professional charcoal makers in the rural area of Lubumbashi is economically and financially viable. This ratio incorporates all production and marketing costs as well as the profit generated by the activity [

49].

With : Benefit ; : Total Cost

When the ratio ˃1, the activity is considered financially profitable.

This means that for every 1 CDF invested in charcoal production, it generates more than 1 CDF

When the ratio ˂ 1, the activity is considered financially unprofitable.

This means that for every 1 CDF invested in charcoal production, it generates less than 1 CDF in profit.

3. Results

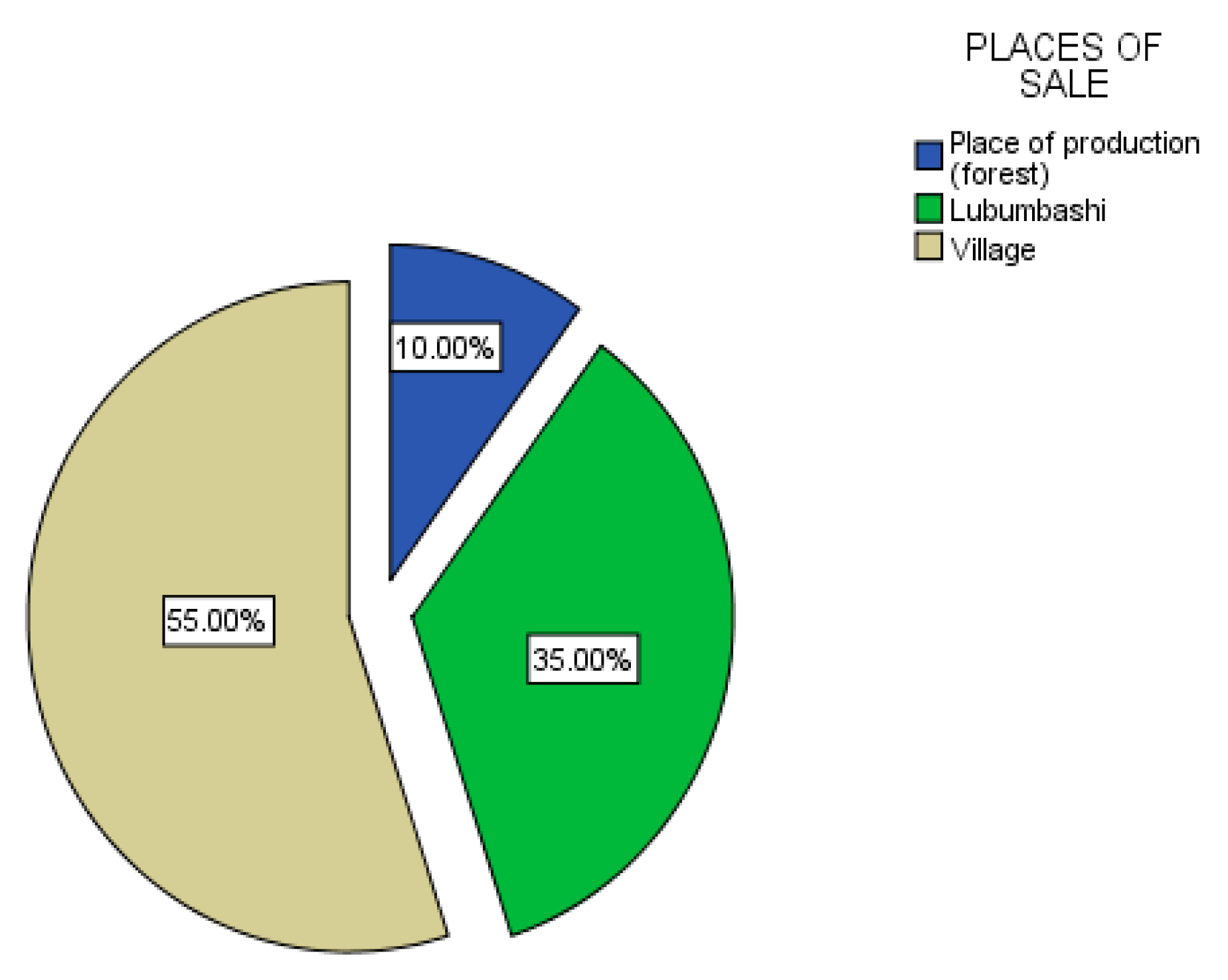

3.1. Places of Sale for Produced Charcoal

The results reveal that 55% of the charcoal producers sell the charcoal within their production village, while 35% transport it to Lubumbashi for marketing. In contrast, only 10% of the sellers sell their production directly at the carbonization site. These results highlight that the majority of the charcoal makers prioritize local sales within their production village (

Figure 3).This section may be divided by subheadings.

3.2. Quantity of Charcoal Sold

The results show that the charcoal producers sold an average of 91 bags of charcoal in Lubumbashi, 87 bags at the production site, and 57 bags in the production villages. It should also be noted that, considering the packaging types, 36 kg bags were the most sold at the production site, averaging 69.50 ~ 70 bags. The 57 kg bags were predominantly sold in Lubumbashi (55.75 ~ 56 bags) and in the village (62.37 bags). The 43 kg bags were most commonly sold in Lubumbashi (55.33 bags). It is worth noting that no significant difference was found regarding the quantities sold by packaging type, according to the sales locations (P˃0.05, ANOVA). These results highlight that the largest quantity of charcoal produced was sold in Lubumbashi, and that the 57 kg bags were the most sold (

Table 2).

3.3. Selling Price of Charcoal in the Lubumbashi Region

The results indicate that a 57 kg bag is sold for 16,104.17 ± 5,913.64 CDF, while the smallest 29 kg bag is marketed at 6,250.00 ± 1,541.10 CDF. Additionally, the selling price fluctuates depending on the seasons. During the dry season, it ranges between 5,000.00 ± 2,121.32 CDF and 15,291.67 ± 3,963.64 CDF, while during the rainy season, it varies between

6,625.00 ± 1,376.89 CDF and 16,916.67 ± 7,722.80 CDF, although no significant differences were found by packaging type when comparing the two seasons (P˃0.05, Student's t-test).

It is also worth noting that, considering the packaging types, the selling price of charcoal increases with the distance from the production site. A 57 kg bag is sold for an average of 10,000.00 ± 0.00 CDF in the forest, 13,406.25 ± 1,731.73 CDF in the village, and 25,333.33 ± 2,516.61 CDF in Lubumbashi. Similarly, the 29 kg bag is sold for 4,500.00 ± 707.11 CDF in the village and 7,125.00 ± 853.91 CDF in Lubumbashi (

Table 3). These results indicate that the selling price of charcoal varies depending on the packaging types.

3.4. Costs Incurred in Charcoal Production in the Lubumbashi Region

3.4.1. Costs at Different Stages of Production and Marketing

The charcoal production and marketing processes in the Lubumbashi region incur various costs. To produce one bag of charcoal, the charcoal producers spend an average of 770.61 CDF for labor related to tree cutting and wood chopping. During the construction of the kiln, particularly for wood sorting and covering steps, expenses amount to 1,165.00 CDF. Additionally, forest taxes are incurred, estimated at 275.00 CDF (0.1 USD).

The total production cost when the bag is sold directly in the forest is 2,987.60 CDF. This cost increases by 2,000.00 CDF when the sale takes place in the village. When charcoal is marketed in Lubumbashi, additional costs need to be considered, including those related to transportation (3,000.00 CDF), handling (1,000.00 CDF), storage fees (428.57 CDF), and urban taxes (400.00 CDF). These results show that the total production and marketing costs of charcoal consist of several expenses incurred by the charcoal makers, varying depending on the sales location (

Table 4).

3.4.2. Total Costs Based on Packaging Types, Sales Locations, and Seasons

For all types of packaging, these costs range from 308,236.80 ± 184,771.51 CDF in the village to 816,703.20 ± 605,344.36 CDF in Lubumbashi. However, according to the type of packaging, the costs do not show significant variations depending on the seasons. On the other hand, when packaging types are not considered, significant differences were found based on the sales locations during the rainy season (P˂0.05, ANOVA). However, for the 57 kg bag, the costs observed in Lubumbashi during the rainy season amounted to 618,622.20 ± 304,084.10 CDF, compared to 182,844.00 ± 0.00 CDF in the dry season. For the 43 kg bag, costs remained high during both periods. In Lubumbashi, they were estimated at 813,655.1 ± 0.00 CDF during the rainy season and 351,974.70 ± 213,328.88 CDF in the dry season. The results indicate that the production and marketing costs of charcoal vary based on the sales location, increasing with the distance from the production site (

Table 5).

3.5. Profitability of Charcoal Sales Based on Packaging Types, Sales Locations, and Seasons

3.5.1. Sales in the Rainy Season

Considering the average of all packaging types, the profit ranges from 291,482.70 ± 141,846.75 CDF at the production site to 610,748.45 ± 677,771.56 CDF in Lubumbashi. Specifically, the 57 kg bag generated the highest profit in Lubumbashi, reaching 1,491,699.70 ± 23,934.57 CDF. Regarding the average profit margin for all packaging types, it stands at 0.52 in the forest, 0.60 in the village, and 0.42 in Lubumbashi. This is also the case for the benefit/cost ratio: 1.08 in the forest, 1.49 in the village, and 0.72 in Lubumbashi. However, the smallest 29 kg bag recorded negative profit, profit margin, and benefit/cost ratio when sold in Lubumbashi, estimated at -15,804.27 ± 8,326.66 CDF, -0.28, and -0.22, respectively. The results indicate that the profit increases with the distance from the production site during the rainy season. In contrast, the profit margin and benefit/cost ratio are negatively correlated with the distance between the production site and the final market (

Table 6).

3.5.2. Sales in the Dry Season

The profit, considering all types of packaging, ranged from 239,963.46 ± 200,814.28 CDF to 451,777.48 ± 459,777.36 CDF, with a lower level in Lubumbashi and a higher level in the village. A similar trend was observed for the profit margin and benefit/cost ratio, which stood at 0.59 in the village, compared to 0.23 in Lubumbashi (1.46 and 0.29).

For the 57 kg bag, the highest profit and profit margin were recorded in the village, reaching 829,950.00 ± 642,707.47 CDF and 0.68, respectively. In Lubumbashi, these values were lower, with a profit of 277,156.00 ± 0.00 CDF and a profit margin of 0.60.

In contrast, for the smallest 29 kg bag, both the profit and profit margin were negative, both in the village and in Lubumbashi. In the village, they amounted to -1,868.79 ± 0.00 CDF and -0.12, while in Lubumbashi, these values reached -149,954.00 ± 0.00 CDF and -0.31. The negative profit margins of -0.12 in the village and -0.31 in Lubumbashi, as well as the benefit/cost ratios of -0.10 in the village and -0.23 in Lubumbashi, confirm the low profitability of this packaging type in the dry season. The results indicate that, during the dry season, charcoal sales are generally not conducted directly at the production site by the charcoal producers (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology Used in the Present Study

In the present study, a monitoring of 20 professional charcoal producers in the rural area of Lubumbashi was conducted. The selection of a limited number of charcoal producers facilitated data collection from the same individuals, covering the entire process from production to commercialization over an eight-month period. This approach enabled close engagement with the respondents throughout the monitoring period and allowed for in-depth data collection. The rationale behind this choice is that continuous data collection ensures more precise and real-time information. Moreover, profitability calculations were facilitated by using actual market prices during the study period. This methodology was adapted from the charcoal kiln monitoring approach implemented in the Batéké Plateau and Yangambi by [

16].

The data for the present study were collected at each stage of the commercialization chain, providing much more detailed information on charcoal marketing in Lubumbashi and its rural area. These data were essential for economic calculations and highlighted a significant difference compared to estimates obtained from one-time surveys conducted at charcoal vendor’s sales locations [

46,

49].

The economic and financial analysis, based on the calculation of three profitability indicators—profit, profit margin, and benefit-cost ratio—clarified uncertainties regarding the profitability of charcoal production, as previously discussed by several authors who conducted studies in the same area. This methodology enabled us to identify the various relationships between economic variables that determine profitability. While most studies have focused solely on profit calculation or value-added estimation using the value chain approach, their findings also confirmed the profitability of charcoal production, as did ours [

14,

30]. Thus, this research successfully demonstrated the overall economic performance of charcoal production, specifying the conditions under which it becomes more profitable. Furthermore, it highlighted the different relationships between economic variables, in contrast to other studies that primarily used statistical models to analyze these relationships [

50,

51].

4.2. Sales Locations of Produced Charcoal

According to our results, the sales locations for charcoal among the respondents were diverse, with the majority of charcoal producers selling mainly in the village, followed by Lubumbashi, and a minority selling at the production site. Sales at the production site occurred directly between producers and resellers, typically at lower prices. Producers are disadvantaged in favor of intermediaries, which leads to lower profit margins compared to other actors in the value chain [

52]. In contrast, village sales dominated due to the increased selling price, which was driven by a relatively small increase in transportation costs from the forest to the village. This aligns with [

53], who emphasize that various economic factors, including the sales location, can influence the commercialization of charcoal. For instance, in Kalounayes, Senegal, some sellers preferred to dispose of their products informally to avoid additional costs from legal taxes. In Lubumbashi, similar practices exist, as some charcoal sellers prefer to sell at home to avoid different taxes paid at official market stalls and warehouses. On the other hand, in Kinshasa, DR Congo, the commercialization of charcoal is mainly concentrated at markets and warehouses for large bags [

9].

Our results corroborate those of [

26], who compared charcoal sales in the cities of Lubumbashi and Kinshasa. They found that in Lubumbashi, charcoal could be sold along the roadsides of charcoal producers' villages and in Lubumbashi itself. [

30] identified the same sales locations as we did for the charcoal sector in Lubumbashi. However, this time, there was a diversity of actors involved, including producers, resellers, wholesalers, or semi-wholesalers. In Lubumbashi, charcoal sold in small bags is generally handled by retailers.

4.3. Quantity of Charcoal Sold

According to our results, the largest quantities of charcoal produced by professional charcoal producers in the rural area of Lubumbashi were sold in Lubumbashi, and it is in this location that the largest bags (57 kg) were sold the most. The choice to sell large quantities of charcoal in Lubumbashi can be explained by the fact that these producers prefer to maximize their profits by minimizing the number of intermediaries [

54]. This situation also leads to high costs associated with transportation, additional taxes, and other expenses related to the delivery of their goods to Lubumbashi. According to [

55], when charcoal is transported from the periphery to the markets of Kinshasa, transportation costs increase depending on the origin of the charcoal, which directly affects profitability at the point of sale.

4.4. Charcoal Sale Price

Our results revealed that the sale price of charcoal varied according to the packaging types, with the 57 kg bag having the highest prices compared to the others. This indicates that packaging charcoal in larger bags offers advantages in terms of market sale prices. Our findings are consistent with those of [

27], who revealed that in Benin, to attract customers and increase profit margins, all roadside vendors preferred packaging charcoal in large bags weighing between 70 and 75 kg, whereas in the past, packaging ranged between 40 and 60 kg. This can also be explained by the fact that urban households in most African cities tend to prefer larger bags of charcoal [

9]. In this context, [

26] show that the size of a charcoal bag is one of the main factors influencing price variability. Smaller bags tend to cost less, while larger ones come with higher prices. The variability in the weight of different packaging leads to price variation, even in retail sales in urban areas, as noted by [

30].

The sale price of charcoal produced in the rural area of Lubumbashi also varies depending on the seasons. For the largest bag, the price was higher during the rainy season, with only a slight difference in the dry season. According to [

37], the season of charcoal sales influences its price because, in the dry season, charcoal production becomes increasingly intense due to better road conditions. In the rainy season, price fluctuations occur due to the inaccessibility of roads and the return of some producers to agricultural work, which impacts the supply of charcoal as well as production and marketing costs. This dynamic has also been observed in Ethiopia, where the price of charcoal fluctuates based on abundant supply during dry periods [

56].

Our results also revealed that the sale price varied depending on the locations where the charcoal was marketed and increased with the distance from the production site. These findings are consistent with those of [

35], in their study in the southwest of Angola, who observed an increase in charcoal prices in urban centers as the distance from the production sites increased. This situation is economically understandable due to the intermediate costs incurred during the transportation of the product from the production site to other sales locations. Thus, [

14,

44] indicate that several costs are involved in the charcoal marketing process, such as transportation, storage, and taxes. This was further emphasized by [

27], who illustrated that in Benin, comparing the sale at the production site and in the city, the cost price of 1 kg of charcoal increased by 122%.

4.5. Costs Associated with the Production and Marketing of Charcoal

Our results indicate that the costs associated with the production and marketing of charcoal in our study area include those related to labor, packaging, taxes, handling, and transportation. Charcoal producers face several costs during the charcoal production process, as highlighted by [

57]. Of all these costs, transportation costs seem to be the highest, particularly when the charcoal is transported to Lubumbashi. This confirms the findings of [

58], who conducted research in the city of Lamim, Brazil, where they found that transportation expenses accounted for a large portion of the total costs, and when combined with land access and tree purchases, these costs represented 82% of the production expenses. According to [

28], labor is a key variable in the productivity of charcoal production. Additionally, labor compensation can be significant due to competition with other rural activities, such as agriculture [

6,

59].

Our results showed that the costs associated with the production and marketing of charcoal varied depending on the sales locations. These costs increased as the distance from the production site increased. This can be explained by the various transportation costs and taxes incurred during the charcoal's transportation. [

34] emphasize that charcoal gains added value when sold in urban areas due to the various expenses incurred during its transportation. Supply basins are located farthest from major urban centers, which influences both production and marketing costs [

33].

Our results also revealed that production costs did not vary based on the types of packaging. This can be explained by the fact that charcoal producers do not finance activities according to the number of bags to be harvested. The yield is not known in advance, and transportation costs do not account for the dimensions of the bags. [

14] highlights several supply constraints when selling charcoal in bulk in Lubumbashi, including administrative and police hassles, increased transportation costs due to vehicle breakdowns, high fuel costs, and the distance from the supply basin.

4.6. Profitability Following the Sale of Charcoal

According to our results, the sale of charcoal was profitable during the rainy season. Profit was related to the place of sale and increased as the distance from the production site increased, although the profit margin and benefit/cost ratios were negatively correlated between the production site and the final sales location. Sales in Lubumbashi were associated with the highest profit levels, especially for the 57 kg bag, as was the case for the profit margins and benefit/cost ratios. This situation is confirmed by [

47], who, in comparing the profits generated in two cities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kinshasa and Kisangani, found that profit in Kinshasa was higher than in Kisangani because producers in the Kinshasa area sold at higher prices, which positively impacted profit. Similarly, the situation in Lubumbashi is likely the same, which also explains the high profitability levels for the 57 kg bag, which sells at a good price regardless of the sales location. Our findings are supported by those of [

60], who revealed that in Madagascar, the accessibility of the charcoal production site or village played a very important role in generating income and profits. Their results showed that charcoal sellers from inaccessible villages had lower incomes and profits, unlike those from accessible villages, due to higher price levels. The profit margin, as the share of profit in income, did not vary during the rainy season due to fluctuations in sale prices during this period, which were not proportional to the expenses incurred.

In contrast, during the dry season, according to our results, the sale of charcoal by charcoal producers in Lubumbashi was profitable, but with higher profitability levels in the village. During this period, no sales were made at the production site. This indicates that the producers preferred to sell their products either in the village or in Lubumbashi, taking advantage of the road accessibility during this period in hopes of earning more. These results once again confirm the importance of the sale price in the profitability of charcoal, as emphasized by [

61], highlighting the importance for producers to be well-informed about prices in the city in order to maximize their profits [

46,

51].

The profit during the dry season was higher in the village and lower in Lubumbashi. This was the case for the largest 57 kg bag, in terms of its profit margin and benefit/cost ratio. Profits and profit margins during this period were negative for the smallest 29 kg bag. This situation is primarily explained economically by the revenue obtained. This leads us to conclude that the sale price was low in relation to high costs. The sale price of charcoal, which fluctuates frequently during both seasons, explains the losses observed in Lubumbashi during the sale of the small 29 kg bags in the dry season. [

36] reveal that in the city of Kinshasa, when supplying charcoal, the price of a sack can vary significantly from 20,000 CDF to 35,000 CDF, representing an increase of nearly

75%.

4.7. Implications for the Future of Charcoal Production

The charcoal sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo faces numerous challenges, such as the lack of regulation, unsatisfactory performance, and limited sustainability [

62]. The unsustainable exploitation of forest resources exacerbates this situation [

63,

64]. While charcoal marketing offers lucrative potential, strategic decisions throughout the distribution process could enhance the efficiency of this activity [

65]. However, environmental degradation, which limits charcoal producers access to markets [

66], along with high transportation costs, taxes, and labor expenses, affect the economic viability of the activity, compromising the livelihoods of charcoal producers and their families [

63].

Our results showed that charcoal production is profitable, and that costs, selling prices, and even profits were linked to the sales locations, increasing as the distance from the forest—the production site—grew. Given that the charcoal supply basin for the city of Lubumbashi is becoming increasingly distant due to deforestation, as highlighted by [

22] and [

23], households in Lubumbashi are likely to face higher charcoal prices in the long term. The essential role of this fuel in Lushois households is undeniable, as 98% of them use it [

10]. At this rate, serious sustainability issues regarding charcoal supply in Lubumbashi will arise.

In this context, the formalization of the charcoal production activity appears as a crucial solution to combat the illegal exploitation of forest resources [

62]. The lack of appropriate forest management strategies, insufficient institutional engagement in ecosystem protection, and inadequate awareness of the dangers of environmental degradation contribute to the unsustainable exploitation of forest resources [

34]. Thus, the policy we propose is that it becomes imperative for charcoal producers to organize themselves into formal structures, which serve as a leverage to make the activity more sustainable [

67,

68], and thus improve charcoal production and marketing. This organization would facilitate access to financing [

69], as well as the collective regulation of taxes, transport, and selling prices, leading to increased income for charcoal producers [

67]. Additionally, these structures would provide charcoal producers with better representation in the governance of wood fuels, highlighting the strategic role of charcoal production in supporting rural development [

70].

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the marketing strategies and profitability of charcoal production in the rural area of Lubumbashi, in the DRC. It was based on regular monitoring of 20 professional charcoal producers, examining the entire process, from production to marketing. The results show that the strategies adopted by charcoal producers, such as the diversification of packaging and sales points, as well as year-round commercialization, directly influence the profitability of their activity. The majority of them sold their charcoal in the village (55%), while 35% transported it directly to Lubumbashi and 10% marketed it at the production site. The selling price, as well as the production and marketing costs, increased with the distance from the production site. Overall, charcoal production remains profitable in all seasons, but it varies according to the type of packaging. The 57 kg bag was the most profitable in terms of profit, profit margin, and cost/benefit ratio. In contrast, the 29 kg packaging proved to be less profitable for sales in Lubumbashi, due to its low or even negative profitability indicators. These limited economic performances are mainly linked to price setting and fluctuations in production and marketing costs.

To improve profitability and sustainability in this sector, we recommend better structuring of producers into associations. Such organizations would allow them to reduce costs through mutual support mechanisms, enhance productivity through training in improved carbonization techniques, and access price information systems. Furthermore, standardizing packaging would contribute to better market regulation. Such an approach would not only help reduce pressure on the Miombo forest but also strengthen producers' profitability, thereby improving their living conditions and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the charcoal sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.U.S., J.N.M.F and J.B.; methodology, N.K.M.; software, N.K.M, H.K.M and D.N.N.; validation, Y.U.S, J.N.M.F and J.B.; formal analysis, N.K.M, J.T.K, L.N.N, and F.B.; investigation, N.K.M.; writing—original draft, N.K.M.; supervision, Y.U.S, P.L; J.N.M.F and J.B.; project administration, Y.U.S and J.B.; funding acquisition, Y.U.S and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project CHARLU (ARES-CCD, Belgium).

Data Availability Statement

The data related to the present study will be available upon request from the interested party.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the members of the studied villages for their hospitality, and especially to all the professional charcoal producers in the rural zone of Lubumbashi, who facilitated our data collection. A special thanks to Mr. Arsen, Jerry, and Mr. Cosmas for their availability and support in the field during the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bergès, L.; Gosselin, M.; Gosselin, F.; Dumas, Y.; Laroussini, O. Prise en compte de la biodiversité dans la gestion forestière : éléments de méthode. Ingénieries n° Spécial 2002 – Aménagement forestier, 2015, 45-55. https://revue-set.fr/article/view/5954.

- Moomaw, W.R.; Law, B.E.; Goetz, S.J. Focus on the role of forests and soils in meeting climate change mitigation goals: summary. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 045009. [CrossRef]

- Eba’a Atyi, R.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Lescuyer, G.; Mayaux, P.; Defourny, P.; Bayol, N.; Saracco, F.; Pokem, D.; Kankeu, R.; Nas, R. Les forêts du bassin du Congo : Etat des forêts 2021. Bogor, Indonésie. CIFOR, 2022, 442 p. https://publications.cirad.fr/une_notice.php?dk=601271.

- Fayama, T.; Traoré, I. ; Sana, H. Contribution des aires protégées à l’amélioration des conditions de vie des populations riveraines : cas de la forêt classée de Dinderesso dans la commune de Bobo-dioulasso. DJIBOUL, 2022, N°003, Vol.3, pp. 300-315. https://djiboul.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/23.-Tionyele.

- Seidel, A. Charcoal in Africa Importance, Problems and Possible Solution Strategies. 2008, 18p. https://energypedia.info/images/2/22/Charcoal-in-africa-gtz_.

- Doggart, N.; Meshack, C. The Marginalization of Sustainable Charcoal Production in the Policies of a Modernizing African Nation. Front. Environ. Sci, 2017, 5, 27, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Bensch, G.; Munyehirwe, A.; Peters, J. The forgotten coal: Charcoal demand in sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. Perspect. 2022, 25, 100401. [CrossRef]

- Ongona, P. Analyse socioéconomique de la consommation de charbon de bois (makala) à Kisangani. Cah. CRIDE, Nouvelle Série. 2013, 10, 2, 1-21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270612123_ANALYSE_SOCIOECONOMIQUE_DE_LA_CONSOMMATION_DE_CHARBON_DE_BOIS_MAKALA_A_KISANGANI.

- Gazull, L.; Dubiez, E.; Mayimba, C.; Péroches, A. Rapport d’étude de la consommation en énergies domestiques des ménages de la ville de Kinshasa. Programme de consommation durable et de substitution partielle au bois-énergie. 2020, 51 p. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/600194/.

- Péroches, A.; Nge, A.; Gazull, L.; Dubiez, E. Rapport d’étude sur la filière bois-énergie de la ville de Lubumbashi. Programme de consommation durable et substitution partielle au bois-énergie. 2021, 78 p. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/600201/.

- Imani, G.; Dubiez, E.; Péroches, A.; Gazull, L. Rapport d’étude de la filière bois énergie dans la ville de Bukavu. Programme de consommation durable et substitution partielle au bois-énergie. 2021, 55 p. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/600202/1/20211112_Rapport_Filière_Bukavu_Vf.pdf.

- Dubiez, E.; Imani, G.; Gazull, L.; Péroches, A. Rapport d’étude de la filière bois-énergie de la ville de Goma. Programme de consommation durable et substitution partielle au bois-énergie.2021, 60 p. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/600200/.

- Schure, J.; Hubert, D.; Ducenne, H.; Kirimi, M.; Awomo, A.; Mpuruta-Ka-Tito, R.; Mumbere, G.; Njenga, M. Carbonisation 2.0 : Comment produire plus de charbon de bois tout en réduisant la quantité de bois et d’émissions de gaz à effet de serre ? Dossier n° 1. Série de dossiers sur le bois-énergie durable. 2021, 26 p. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/8481/.

- Nge, A. Diagnostic socioéconomique et environnemental de la chaîne de valeur « charbon de bois » à Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RDC): Perspectives pour une gestion durable des ressources ligneuses de Miombo. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Lubumbashi, RDC. 2021. 296 p. https:// www.academia.edu/49095718/UNIVERSITE_DE_LUBUMBASHI_VERSION_REVUE_ET_CORRIGEE_1_.

- Kasanda, N.; Khoji, H.; N’Tambwe, D.; Berti, F.; Useni, Y.; Ndjibu, L.; Katond, J.P.; Nkulu, J.; Lebailly, P.; Bogaert, J. Quantification and Determinants of Carbonization Yield in the Rural Zone of Lubumbashi, DR Congo: Implications for Sustainable Charcoal Production. Forests, 2024, 15, 554, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Schure, J.; Pinta, F.; Cerutti P.O.; Kasereka M.L. Efficiency of charcoal production in Sub-Saharan Africa: solutions beyond the kiln. Bois For. Trop. 2019, 340, 57-70. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/592632/1/BFT340-57-70-Efficiency%20. [CrossRef]

- Peltier, R.; Bisiaux, F.; Dubiez, E.; Marien, J.N.; Muliele, J.C.; Proces, P.; Vermeulen, C. 2010. De la culture itinérante sur brulis aux jachères enrichies productrices de charbon de bois, en R.D. du Congo. Montpellier, France. 2010, 16 p. ffhal-00512274f. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/556923/1/document_556923.pdf.

- Tchatchou, B.; Sonwa, D.J.; Ifo, S.; Tiani, A.M. Déforestation et dégradation des forêts dans le Bassin du Congo État des lieux, causes actuelles et perspectives. Papier occasionnel 120. Bogor, Indonesie : CIFOR, 2015, 47 p. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/items/15da95e3-62da-4b24-98a4-e9f0d9c3727e.

- Kasekete, D.; Bourland, N.; Gerkens, M.; Louppe, D.; Schure, J.; Mate J.P. Bois-énergie et plantations à vocation énergétique en République démocratique du Congo : cas de la province du Nord-Kivu – Synthèse bibliographique. Bois For. Trop. 2023, 357, p. 5-28. https://revues.cirad.fr/index.php/BFT/article/view/36927.

- Barbiche, R.; Bisimwa, R. Des forêts et des hommes face au développement durable L’exemple du Congo RDC. Popul. 2020, 4,749,14-16. [CrossRef]

- Useni Y.; Malaisse F.; Cabala, S.; Munyemba, F.; Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo) : Synthèse. Tropicultura, 2017, 35,3, 215-221. https://popups.uliege.be/2295-8010/index.php?id=1277.

- Djibu, J.P.; Vranken, I.; Bastin, J.F.; Malaisse, F.; Nyembwe, S.; Useni, Y.; Ngongo, M.; Bogaert, J. Approvisionnement des ménages Lushois en charbon de bois: quantités, alternatives et conséquences. In : Bogaert, J.; Collinet, G.; Mahy, G. Anthropisation des territoires Katangais. Gembloux : presse universitaires de Gembloux, 2018, pp 297-308. https://orbi.uliege.be.

- Khoji, H.; N’Tambwe, D.; Mwamba, F.; Strammer, H.; Munyemba, F.; Malaisse, F. ; Bastin, J.F.; Useni, Y.; Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land, 2023, 12, 1852, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Ihalainen, M.; Awono, A.; Banda, E.; Moombe, K.; Mwaanga, B.; Schure, J.; Sola, P. Les femmes, cette anomalie persistante dans le secteur du charbon de bois : des approches intégrant la dimension de genre pour des résultats plus inclusifs, équitables et durables. Dossier N°2. Le Bois-Energie Durable. Projet Gouvernance des paysages multifonctionnels (GML). Bogor, Indonésie et Nairobi, Kenya : CIFOR-ICRAF, 2021, 22p. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/items/02d32121-fd20-4fc6-9eda-787e25b0cb5e.

- Mpundu, M. 2018. Forêt claire de miombo : source d’énergie et d’aliments des populations du Haut-Katanga In : Tshonda, J.; Ngoy, P.; Badie, M.; Krawczyk, J.; Laghmouch, M. République démocratique du Congo HAUT-KATANGA, lorsque richesses économiques et pouvoirs politiques forcent une identité régionale. Tome 1 Cadre naturel, peuplement et politique. 2018, 55-64 pp. https://www.africamuseum.be › rmca › online.

- Trefon, T.; Hendriks, T.; Kabuyaya, N.; Ngoy, B. L’économie politique de la filière du charbon de bois à Kinshasa et à Lubumbashi, appui stratégique à la politique de reconstruction post-conflit en R.D.C. Institut of Development Policy and Management, University of Antwerp. IOB Working paper, 2010, 110 p. https://lirias2repo.kuleuven.be › bitstream › Trefo...

- Mama, V.J.; Biaou, F. Production du charbon de bois au bénin : menace ou opportunité pour l’adoption des mesures au changement climatique ? Cah. Cent. Bénin. Rech. Sci. Innov. 2017, 11, 50-70. https://publicationschercheurs.inrab.bj/uploads/fichiers/recents/71b47ec3a19016c4221c82ca77351995.pd.

- Andaregie, A.; Worku, A.; Astatkie, T. Analysis of economic efficiency in charcoal production in Northwest Ethiopia: A Cobb-Douglas production frontier approach. Trees For. People, 2020, 2, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kamwilu, E.; Duguma, L.A.; Orero, L. 2021. The Potentials and Challenges of Achieving Sustainability through Charcoal Producer Associations in Kenya: A Missed Opportunity? Sustainability, 2021, 13, 2288, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Münkner, C.A.; Bouquet, M.; Muakana, R. Analyse des chaines de valeur ajoutée en bois-énergie et bois d'œuvre de la ville de Lubumbashi dans la province du Katanga. Programme Biodiversité et forêt, GIZ, 2015, 92 p.

- Chia, E.; Petit, M.; Brossier, J. Théorie du comportement adaptatif et agriculture familiale. Gasselin P. (ed.), Choisis J.P. (ed.), Petit S. (ed.), Purseigle F. (ed.), Zasser-Bedoya S. (ed.). L’agriculture en famille : travailler, réinventer, transmettre, EDP Sciences, 2020, pp.81-100, 2014, 978-2-7598-1192-2 978-2- 7598-1765-8. ff10.1051/978-2-7598-1192-2.c006ff. ffhal-02163636. https://hal.science/hal-02163636.

- Gazull, L.; Gautier, D.; Raton, G. Analyse de l'évolution des filières d'approvisionnement en bois-énergie de la ville de Bamako : Mise en perspective des dynamiques observées avec les politiques publiques mises en œuvre depuis 15 ans. Rapport d'expertise du CIRAD, Département Forêts UPR "Ressources forestières et Politiques publiques, 2006, 48 p. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/274378433.

- Kaina, A.; Dourma, M.; Folega, F.; Diwediga, B.; Wala, K.; Akpagana, K. Localisation des bassins de production de bois énergie et typologie des acteurs de la filière dans la région centrale du Togo. Rev. Ivoir. Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 196 – 211. https://www.researchgate.net › publication › 35323761...

- Tamboura, S.; Irie, B.V.G.; Akoué, Y. Sens et enjeux du maintien de la production informelle du charbon de bois en contexte de changement climatique. RIREP. 2022, 6, 287-303. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03873510/document.

- Kissanga, R.; Catarino, L.; Máguas, C.; Cabral, A.I.R. Dynamics of land-cover change and characterization of charcoal production and trade in southwestern Angola. Remote Sens. Appl.: Soc. Environ. 2024, 34, 101162, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Masamba, J.; Mpanzu, P.; Ngonde, H.; Kinkela, C. 2023. État des lieux de l’utilisation des énergies de cuisson dans les ménages de Kinshasa : analyse de la substitution du bois-énergie. Bois For. Trop.2023, 355 : 35-46. Doi : . [CrossRef]

- Bekpa-Kinhou, A.C.M. Exploitation Du Bois Energie Et Du Charbon De Bois Dans La Commune De Zogbodomey Au Centre Du Benin. Int. J. Prog. Sci. Technol. 2024, Vol. 42 No. 2, pp. 458-466. https://ijpsat.org/index.php/ijpsat/article/view/5957.

- Vranken, I. Pollution et contamination des sols aux métaux lourds dues à l’industrie métallurgique à Lubumbashi : Empreinte écologique, impact paysager, pistes de gestion. Mémoire de fin d’Etudes, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgique. 2010, 90 p. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/118879.

- Malaisse, F. How to Live and Survive in Zambezian Open Forest (Miombo Ecoregion); Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2010, Volume 23, pp. 91–97 https://presses.uliege.be/produit/how-to-live-and-survive-in-zambezian-open-forest-miombo-ecoregion/.

- Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Boisson, S.; Useni, Y. La végétation naturelle d’Élisabethville (actuellement Lubumbashi) au début et au milieu du XXième siècle. Geo-Eco-Trop., 2021, 45, 1 : 41-51. https://www.geoecotrop.be/uploads/publications/pub_451_04.pdf.

- Kasanda, N.; Useni, Y.; Ngoy, L.; Berti, F.; Nkulu, J.; Lebailly P. Caractéristiques des producteurs de charbon de bois du bassin d’approvisionnement de la ville de Lubumbashi (RDC) : Analyse sociodémographique, socio ethnographique, typologie et organisation de la production. Tropicultura, 2024, 2295-8010 Volume 42 , 2558, 1-20. https://popups.uliege.be › 2295-8010 › pdf.

- N’tambwe, N.D.; Muteya, K.H.; Kasongo, K.B.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Useni, S.Y.; Masengo, K.W.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests, 2023, 14, 687. [CrossRef]

- Muteba, D. Caractérisation des modes de consommation alimentaire des ménages à Kinshasa : Analyse des interrelations entre modes de vie et habitudes alimentaires. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Liège Gembloux-Agro Biotech, Gembloux, Belgique, 2014, p.179. https://orbi.uliege.be › bitstream › MUTEBA_Th...

- Sabuhungu, G. Analyse de la demande en charbon de bois par les ménages urbains de Bujumbura au Burundi. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Liège Gembloux-Agro Biotech, Gembloux, Belgique, 2016, p.192. https://orbi.uliege.be/bitstream/2268/200912/1/Emery%20Ga.

- Yabi, J.A.; Paraïso, A.; Yegbemey, R. N.; Chanou, P. Rentabilité Economique des Systèmes Rizicoles de la Commune de Malanville au Nord-Est du Bénin. Bull. Rech. Agron. Bénin (BRAB), Numéro spécial Productions Végétales & Animales et Economie & Sociologie Rurales, 2012, 1-12. http://www.slire.net/download/1769/article_1_yabi_et_al_rizicu.

- Mere, S.; Yabi, A.J. Déterminants de la rentabilité économique des activités de l’artisanat du bois au Nord-Est du Bénin. Afr. Sci. 2024, 24(4), 87-105.

- Schure, J.; Ingram, V.; Akalakou-Mayimba, C. Bois énergie en RDC : Analyse de la filière des villes de Kinshasa et de Kisangani. Projet Makala, Gérer durablement la ressource bois énergie, 2011, 88 p. http://makala.cirad.fr/les_produits/publications/rapports/2011_analyse_de_la_filiere_bois_energie_des_villes_de_kinshasa_et_de_kisangani_cifor.

- Bonou, A. Estimation de la valeur économique des Produits Forestiers Non Ligneux (PFNL) d’origine végétale dans le village de Sampéto (commune de Banikoara). Mémoire de DEA, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Benin, 2008, 66 p. . [CrossRef]

- Paraïso, A.; Yabi, A.J.; Sossou, A.; Zoumarou-Wallis, N.; Yègbémey, R.N. Rentabilité économique et financière de la production cotonnière a Ouaké au Nord–Ouest du Bénin. Ann. Sci. Agron. 2012, 16 (1), 91-105. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/asab/article/view/106721.

- FAO. Manuel sur les statistiques des coûts de production agricoles : Directives pour la collecte, la compilation et la diffusion des données, 2016, 104 p. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core /bitstreams/5fc3ca32-e450-4882-ba74-854d3cf09659/content.

- Dossa, F.K.; Todota, C.T.; Miassi, E.S.; Agboton, G.A. Analyse comparée de la performance économique des cultures de coton et de maïs au Nord-Bénin: cas de la commune de Kandi. Int. J. Curr. Innov. Adv. Res.. 2018, Volume 1, Issue 6, 118-130. https://ijciar.com/index.php/journal/article/view/61.

- Lejars, C.; Courilleau, S., 2014. La filière d’oignon d’été dans le Saïs au Maroc : la place et le rôle des intermédiaires de la commercialisation. Altern. Rur. 2014, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Sane, A.B.S.; Barry, B.; Benga, A.G.F. Impact socio-économique et écologique de l’aménagement forestier du massif des Kalounayes. J. Écon. Manag. Environ. Droit. 2020, 3, 2, 84-99. https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/JEMED/article/view/23025.

- Agbugba, I.K.; Ajuruchukwu, O. 2013 .Market Structure, Price Formation and Price Transmission for Wood Charcoal in Southeastern Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, Vol. 5, No. 10; Canadian Center of Science and Education, 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Shuku, N. Impact de l’utilisation de l’énergie-bois dans la ville province de Kinshasa en République démocratique du Congo (RDC). Mémoire de Maitrise, Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada, 2011, 168 p. https://archipel.uqam.ca/4598/1/M12010.pdf.

- Worku, A.; Andaregie, A.; Astatkie, T. Analysis of the Charcoal Market Chain in Northwest Ethiopia. Small-scale For. 2021, 20, 407–424. [CrossRef]

- Mutta, D.; Mahamane, L.; Wekesa, C.; Kowero, G.; Roos, A. Sustainable Business Models for Informal Charcoal Producers in Kenya. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 3475, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Schettini, B.; Jacovine, L.; Torres, C.; Carneiro, A.; Villanova, P.; Rocha, S.; Rufino, M.; Castro, R. Wood and charcoal production in the kiln-furnace system: how do the costs and revenues variation affect economic feasibility? Rev. Árvore. 2021, 45:e4539, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Eniola, P.O. Menace and Mitigation of Health and Environmental Hazards of Charcoal Production in Nigeria. Afr. Handb. Clim. Chang. Adapt. 2021, 17 p. [CrossRef]

- Ranaivoson, T. Impacts écologiques et socio-économiques de la production de charbon de bois sur le Plateau Mahafaly, sud-ouest de Madagascar. Thèse de doctorat, Université d’Antanarivo, Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2017, 120 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320372267_Impacts_ecologiques_et_socio-economiques_de_la_production_de_charbonde_bois_sur_le_Plateau_Mahafaly_sud-ouest_de_Madagascar.

- Brobbey, L.; Hansen, C.; Kyereh, B. The dynamics of property and other mechanisms of access: The case of charcoal production and trade in Ghana. Land Use Policy, 2021, 101, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Ciza, S.; Mikwa, J.F.; Malekezi, A.; Gond, V.; Bosela, F. Identification des moteurs de déforestation dans la région d’Isangi, République démocratique du Congo. Bois For. Trop. 2015, 3 2 4, 2. 29-38. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/578166/ . [CrossRef]

- Zira, B.D. Economic Analysis of Charcoal Production in Semi - Arid Region of Nigeria. IJARSSET, 2019, 52-61. https://internationalpolicybrief.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/.

- Mbuangi, M.; Ntoto, R.; Kisombe, M.; Khonde, C. Les enjeux socioéconomiques et écologiques de la production du charbon de bois dans la périphérie de la ville de Boma en RDC. JISTEE, 2021, Vol.(vi),3, 42-54. https://jistee.org/wp-content/uploads /2021/09/Mbuangi-Lusuadi-Maurice42-54.pdf.

- Zulu, L.C.; Richardson, R.B. Charcoal, livelihoods, and poverty reduction: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2013, 17, 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Trégourès, A. La structuration des filières d’approvisionnement en bois énergie dans la province du Zambèze (Mozambique) : Programme sous-national de réduction des émissions de carbone liées à la déforestation et à la dégradation forestière (REDD+). Mémoire de Mastère Spécialisé Forêt, Nature et Société (AgroParisTech), 2015, 120 p. https://www.nitidae.org › files › 161019111820.

- Schure, J.; Ingram, V.; Sakho-Jimbira, M.S.; Levang, P.; Wiersum, K.F. Formalisation of charcoal value chains and livelihood outcomes in Central- and West Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2012, 17, 95-105. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/3879/. [CrossRef]

- Baumert, S.; Luz, A.C.; Fisher, J.; Vollmer, F.; Ryan, C.M.; Patenaude, G.; Zorrilla-Miras, P.; Artur, L.; Nhantumbo, I.; Macqueen, D. Charcoal supply chains from Mabalane to Maputo: Who benefits? Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 33,129-138. [CrossRef]

- Oluwasola, B.T.; Solomon, K.; Omowunmi, B.; Olujide, J. Analyzing the Aspects of Profitability of Charcoal Production and Marketing in Ibarapa Zone of Oyo State Nigeria, Curr. Strat. Econ. Manag, 2019, Vol. 5, 137-145. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. The Power of the Informal Smallholder charcoal production in Mozambique. Post graduate degree, The University of Edinburgh, 2016, 169 p. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/23654.

Figure 1.

Location of the studied villages in the rural area of Lubumbashi and their respective distances from the city.

Figure 1.

Location of the studied villages in the rural area of Lubumbashi and their respective distances from the city.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the types of charcoal packaging identified in the rural area of Lubumbashi. A: Represents the largest bag, weighing about 57 kg, with a very wide upper part. The sticks at its end correspond to the length equivalent to 3 spans (a measurement used by charcoal producers). B: A 43 kg bag, moderately wide at the top, and the sticks at its end correspond to 2 spans. C: A 36 kg bag, narrower, and the length of the sticks at its end measures around 1 span. D: A bag weighing around 29 kg, with no extended sticks at its end, generally measuring less than one span.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the types of charcoal packaging identified in the rural area of Lubumbashi. A: Represents the largest bag, weighing about 57 kg, with a very wide upper part. The sticks at its end correspond to the length equivalent to 3 spans (a measurement used by charcoal producers). B: A 43 kg bag, moderately wide at the top, and the sticks at its end correspond to 2 spans. C: A 36 kg bag, narrower, and the length of the sticks at its end measures around 1 span. D: A bag weighing around 29 kg, with no extended sticks at its end, generally measuring less than one span.

Figure 3.

Distribution of professional charcoal producers by Their sales locations.

Figure 3.

Distribution of professional charcoal producers by Their sales locations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the charcoal-producing villages studied in the rural area of Lubumbashi (DR Congo).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the charcoal-producing villages studied in the rural area of Lubumbashi (DR Congo).

| No. |

Village |

Geographical coordinates |

Number of households |

| 1 |

Maksem |

11° 19’ S; 27° 50’ E |

2,133 |

| 2 |

Sela |

11° 20’ S; 27° 36’ E |

1,150 |

| 3 |

Mwawa |

12° 03’ S; 27° 35’ E |

163 |

| 4 |

Luisha |

11° 10’ S; 27° 01’ E |

2,670 |

| Total |

6,116 |

Table 2.

Quantity (mean ± standard deviation) of charcoal sold per charcoal maker according to the sales locations in Lubumbashi and its rural area, during the period from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are expressed as Mean ± standard deviation. n represents the sample size.

Table 2.

Quantity (mean ± standard deviation) of charcoal sold per charcoal maker according to the sales locations in Lubumbashi and its rural area, during the period from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are expressed as Mean ± standard deviation. n represents the sample size.

| Sales locations |

Types of packaging |

| 57 kg |

43 kg |

36 kg |

29 kg |

All types of bags |

| Production site (n=2) |

35.00 ± 0.00 |

- |

69.50±92.63 |

- |

87.00± 67.88 |

| Village (n=11) |

62.37 ± 32.95 |

22.50 ± 25.05 |

40.00 ± 0.00 |

6.00 ± 2.82 |

58.27 ± 37.86 |

| Lubumbashi (n=7) |

55.75 ± 36.13 |

55.33 ± 33.50 |

52.00 ± 44.58 |

23.50 ± 31.00 |

91.28 ± 38.81 |

| Total (n=20) |

58.23 ± 31.91 |

36.57 ± 31.56 |

55.83 ± 51.43 |

17.67 ± 25.69 |

(n=20) |

| P value |

0.744 |

0.195 |

0.925 |

0.494 |

0.494 |

Table 3.

Evolution of the Selling Price (mean ± standard deviation) from January to September 2022, according to seasons, sales locations, and packaging types in Lubumbashi and the rural area. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC). n = Sample size.

Table 3.

Evolution of the Selling Price (mean ± standard deviation) from January to September 2022, according to seasons, sales locations, and packaging types in Lubumbashi and the rural area. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC). n = Sample size.

| Variables |

Types of packaging |

| Sac de 57 kg |

Sac de 43 kg |

Sac de 36 kg |

Sac de 29 kg |

All Types of Packaging |

| Season |

| Rainy season (n=11) |

16,916.67 ± 7,722.80 |

11,666.67 ± 2,886.75 |

8,000.00 ± 3,464.10 |

6,625.00 ± 1,376.89 |

12,045.46 ± 5,090.43 |

| Dry season (n=9) |

15,291.67 ± 3,963.64 |

11,000.00 ± 5,354.13 |

10,166.67 ± 2,362.90 |

5,500.00 ± 2,121.32 |

12,435.19 ± 4,364.42 |

| P value |

0.656 |

0.855 |

0.421 |

0.461 |

0.863 |

| Sales location |

| Production site (n=2) |

10,000.00 ± 0.00 |

- |

6,000.00 ± 0.00 |

- |

7,000.00 ± 1,414.21 |

| Lubumbashi (n=7) |

25,333.33 ± 2516.61 |

15,333.33 ± 1,527.53 |

11,666.67 ± 577.35 |

7,125.00 ± 853.91 |

15,250.00 ± 6,860.21 |

| Village (n=11) |

13,406.25 ± 1.731.73 |

8,250.00 ± 2,061.55 |

7,500.00 ± 0.00 |

4,500.00 ± 707.11 |

11,242.43 ± 3,135.91 |

| Total |

16,104.17 ± 5.913.64 |

11,285.71 ± 4,151.88 |

9,083.33 ± 2,905.45 |

6,250.00 ± 1,541.10 |

12,220.84 ± 5,191.03 |

| P Value |

0.000* |

0.004* |

0.002* |

0.021* |

0.084 |

Table 4.

Distribution of Production and Marketing Costs (mean ± standard deviation) per Bag of Charcoal Produced, Based on Sales Locations in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area. The period considered is from January to September 2022, and the exchange rate is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

Table 4.

Distribution of Production and Marketing Costs (mean ± standard deviation) per Bag of Charcoal Produced, Based on Sales Locations in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area. The period considered is from January to September 2022, and the exchange rate is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

| Activities |

Sales Location |

| Forest |

Village |

Lubumbashi |

All sales locations |

| Felling and cutting |

770.61 ± 0.00 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Sorting and covering |

1.165.00 ± 0.00 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Packaging |

777.00 ± 0.00 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Village transport |

0 |

2,000.00 ± 447.21 |

0 |

0 |

| Lubumbashi transport |

0 |

0 |

3,000.00 ± 577.35 |

3,000.00 ± 577.35 |

| Forest taxes |

275.00 ± 35.35 |

285.00 ± 85.15 |

300.00 ± 95.74 |

289.47± 82.63 |

| Village taxes |

0 |

261.11 ± 48.59 |

221.43 ± 26.73 |

243.75 ± 44.25 |

| Lubumbashi taxes |

0 |

0 |

400.00 ± 76.38 |

400.00 ± 76.38 |

| Storage |

0 |

0 |

428.57 ± 48.79 |

425.00 ± 46.29 |

| Loading and unloading |

0 |

0 |

1,000.00 ± 0.00 |

1,000.00 ± 0.00 |

Table 5.

Production and Marketing Costs (Mean and Standard Deviation) Based on Sales Locations, Seasons, and Packaging Types. The values are presented in Congolese Francs, and the period considered is from January to September 2022. The exchange rate is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC). n = Sample size.

Table 5.

Production and Marketing Costs (Mean and Standard Deviation) Based on Sales Locations, Seasons, and Packaging Types. The values are presented in Congolese Francs, and the period considered is from January to September 2022. The exchange rate is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD in September 2022 (Source: BCDC). n = Sample size.

Variables

(Rainy season) |

Sales location |

|

| Forest |

Village |

Lubumbashi |

P value |

| 57 kg bag (n=7) |

108,426.50 ± 0.00 |

296,324.27 ± 44,746.39 |

618,622.20 ± 304,084.10 |

0.177 |

| 43 kg bag (n=3) |

- |

44,672.00 ± 12,635.15 |

813,655.80 ± 0.00 |

0.013* |

| 36 kg bag (n=3) |

215,304.05 ± 286,961.54 |

- |

502,821.00 ± 0.00 |

0.563 |

| 29 kg bag (n=4) |

35,737.60 ± 0.00 |

- |

73,137.60 ± 0.00 |

- |

| All bag types (n=11) |

269,517.30 ± 210,292.43 |

202,810.88 ± 145,838.85 |

847,939.05 ± 83.247.58 |

0.000* |

Variables

(Dry season)

|

|

|

|

|

| 57 kg bag (n=6) |

- |

268,032.00 ± 191,204.51 |

182,844.00 ± 0.00 |

0.705 |

| 43 kg bag (n=4) |

- |

156,352.00 ± 157,939.37 |

351,974.70 ± 213,328.88 |

0.407 |

| 36 kg bag (n=3) |

- |

178,688.00 ± 0.00 |

461,681.10 ± 575,341.53 |

0.757 |

| 29 kg bag (n=2) |

- |

17,868.80 ± 0.00 |

639,954.00 ± 0.00 |

- |

| All bag types (n=9) |

- |

308,236.80 ± 184,771.51 |

816,703.20 ± 605,344.36 |

0.085 |

Table 6.

Distribution of Profit, Profit Margin, and Benefit/Cost Ratio During the Rainy Season from the Sale of Different Charcoal Packaging Types in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area, from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are in Mean ± Standard Deviation. GR represents Gross Revenue; PM represents Profit Margin; B/C represents Benefit/Cost Ratio. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD as of September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

Table 6.

Distribution of Profit, Profit Margin, and Benefit/Cost Ratio During the Rainy Season from the Sale of Different Charcoal Packaging Types in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area, from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are in Mean ± Standard Deviation. GR represents Gross Revenue; PM represents Profit Margin; B/C represents Benefit/Cost Ratio. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD as of September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

| Variables |

|

Sales location |

| |

Forest |

Village |

Lubumbashi |

| 57 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

350,000.00 ± 0.00 |

836,666.67 ± 91,527.77 |

2,282,500.00 ± 60,104.07 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

108,426.50 ± 0.00 |

296,324.27 ± 44,746.39 |

618,622.20 ± 304,084.10 |

| Profit (CDF) |

241,573.50 ± 0.00 |

540,342.40 ± 110,678.99 |

1,491,699.70 ± 23,934.57 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.69 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

| B/C Ratio |

2.23 |

1.82 |

2.41 |

| 43 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

- |

100,000.00 ± 28,284.27 |

1,335,000.00 ± 0.00 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

- |

813,655.80 ± 0.00 |

44,672.00 ± 12,635.15 |

| Profit (CDF) |

- |

55,328.00 ± 0.00 |

521,344.19 ± 0.00 |

| PM (CDF) |

- |

0.55 |

0.39 |

| B/C Ratio |

|

0.07 |

11.67 |

| 36 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

417,000.00 ± 555,785.93 |

- |

660,000.00 ± 0.00 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

215,304.05 ± 286,961.54 |

|

502,821.00 ± 0.00 |

| Profit (CDF) |

201,695.95 ± 268,824.39 |

- |

157,179.00 ± 0.00 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.48 |

- |

0.24 |

| B/C Ratio |

0.94 |

- |

0.31 |

| 29 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

- |

40,000.00 ± 0.00 |

57,333.33 ± 8,326.66 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

|

35,737.60 ± 0.00 |

73,137.6 0± 0,00 |

| Profit (CDF) |

- |

4,262.40 ± 0.00 |

- 15,804.27 ± 8,326.66 |

| PM (CDF) |

- |

0.11 |

-0.28 |

| B/C Ratio |

- |

0.11 |

-0.22 |

| All Types of Bags |

GR (CDF) |

561,000.00 ± 352,139.18 |

504,400.00 ± 385,850.75 |

1,458,687.5 ± 62,5870.3 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

269,517.30 ± 210,292.43 |

202,810.88 ± 145,838.85 |

847,939.05 ± 83,247.58 |

| Profit (CDF) |

291,482.70 ± 141,846.75 |

301,589.10 ± 250,323.38 |

610,748.45 ± 677,771.56 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.52 |

0.60 |

0.42 |

| B/C Ratio |

1.08 |

1.49 |

0.72 |

Table 7.

Distribution of Profit, Profit Margin, and Benefit/Cost Ratio During the Dry Season from the Sale of Different Charcoal Packaging Types in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area, from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are in Mean ± Standard Deviation. GR represents Gross Revenue; PM represents Profit Margin; B/C represents Benefit/Cost Ratio. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD as of September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

Table 7.

Distribution of Profit, Profit Margin, and Benefit/Cost Ratio During the Dry Season from the Sale of Different Charcoal Packaging Types in Lubumbashi and its Rural Area, from January to September 2022. The values presented in the table are in Mean ± Standard Deviation. GR represents Gross Revenue; PM represents Profit Margin; B/C represents Benefit/Cost Ratio. The exchange rate considered is 2,050 CDF per 1 USD as of September 2022 (Source: BCDC).

| Packaging |

Sales location |

| Variables |

Village |

Lubumbashi |

| 57 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

829,950.00 ± 642,707.47 |

460,000.00 ± 0.00 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

268,032.00 ± 191,204.51 |

182,844.00 ± 0.00 |

| Profit (CDF) |

561,918.00 ± 454,126.10 |

277,156.00 ± 0.00 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.68 |

0.60 |

| B/C Ratio |

2.09 |

1.52 |

| 43 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

215,000.00 ± 205,060.97 |

572,000.00 ± 280,014.29 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

156,352.00 ± 157,939.37 |

351,974.70 ± 213,328.88 |

| Profit (CDF) |

58,648.00 ± 47,121.59 |

220,025.30 ± 66,685.40 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.27 |

0,38 |

| B/C Ratio |

0.38 |

0,63 |

| 36 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

300,000.00 ± 0.00 |

603,000.00 ± 759,432.68 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

178,688.00 ± 0.00 |

461,681.10 ± 575,341.53 |

| Profit (CDF) |

121,312.00 ± 0.00 |

141,318.90 ± 184,091.15 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.40 |

0.23 |

| B/C Ratio |

0.67 |

0.31 |

| 29 kg bag |

GR (CDF) |

16,000.00 ± 0.00 |

490,000.00 ± 0.00 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

17,868.80 ± 0.00 |

639,954.00 ± 0.00 |

| Profit (CDF) |

-1,868.79 ± 0.00 |

-149,954.00 ± 0.00 |

| PM (CDF) |

-0.12 |

-0.31 |

| B/C Ratio |

-0.10 |

-0.23 |

| All Types of Bags |

GR (CDF) |

760,014.28 ± 593,564.09 |

1,056,666.67 ± 444,088.49 |

| Total costs (CDF) |

308,236.80 ± 184,771.51 |

816,703.20 ± 605,344.36 |

| Profit (CDF) |

451,777.48 ± 459,777.36 |

239,963.46 ± 200,814.28 |

| PM (CDF) |

0.59 |

0.23 |

| B/C Ratio |

1.46 |

0.29 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).