Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Selection

2.2. Methodology to Determine the Physical and Mechanical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

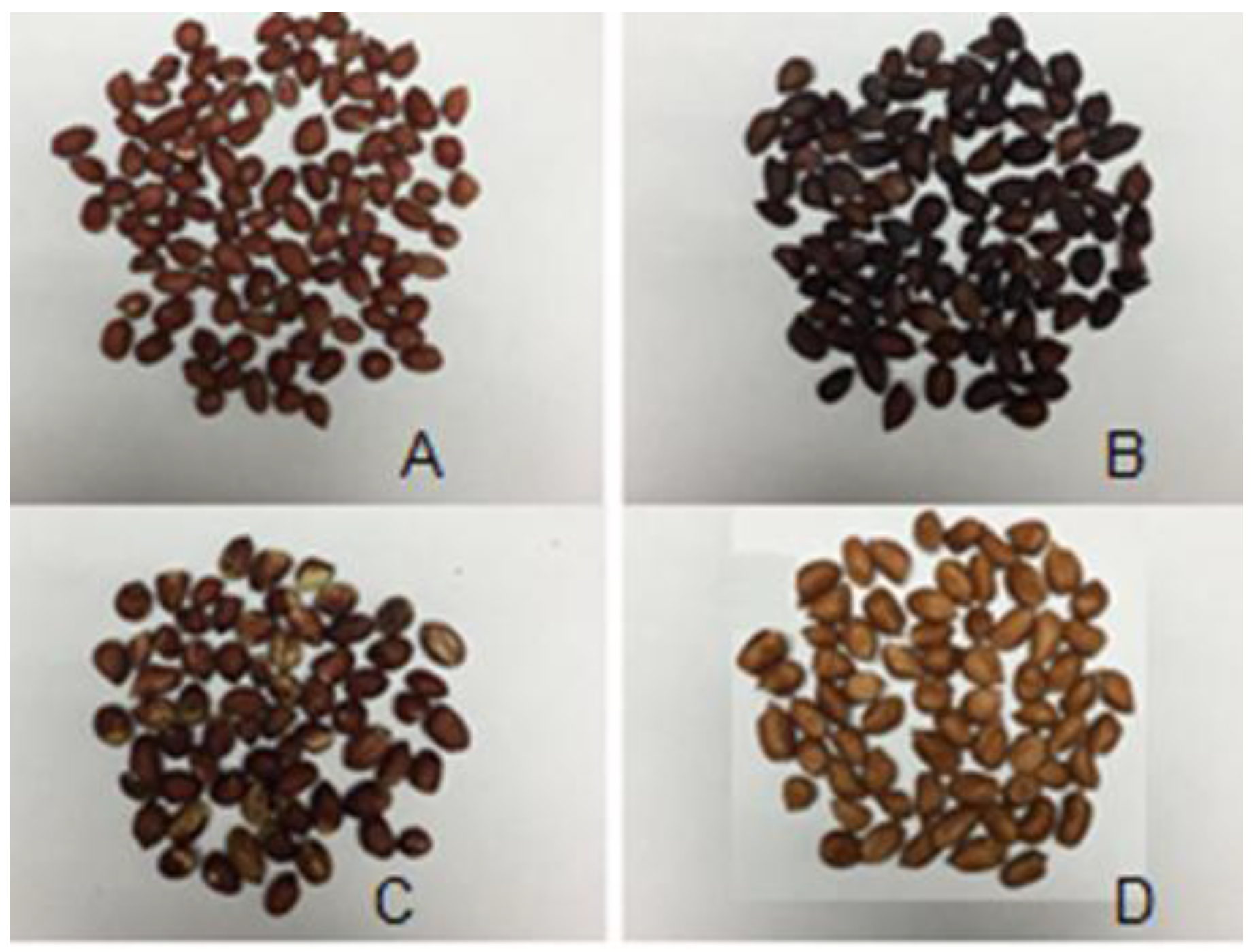

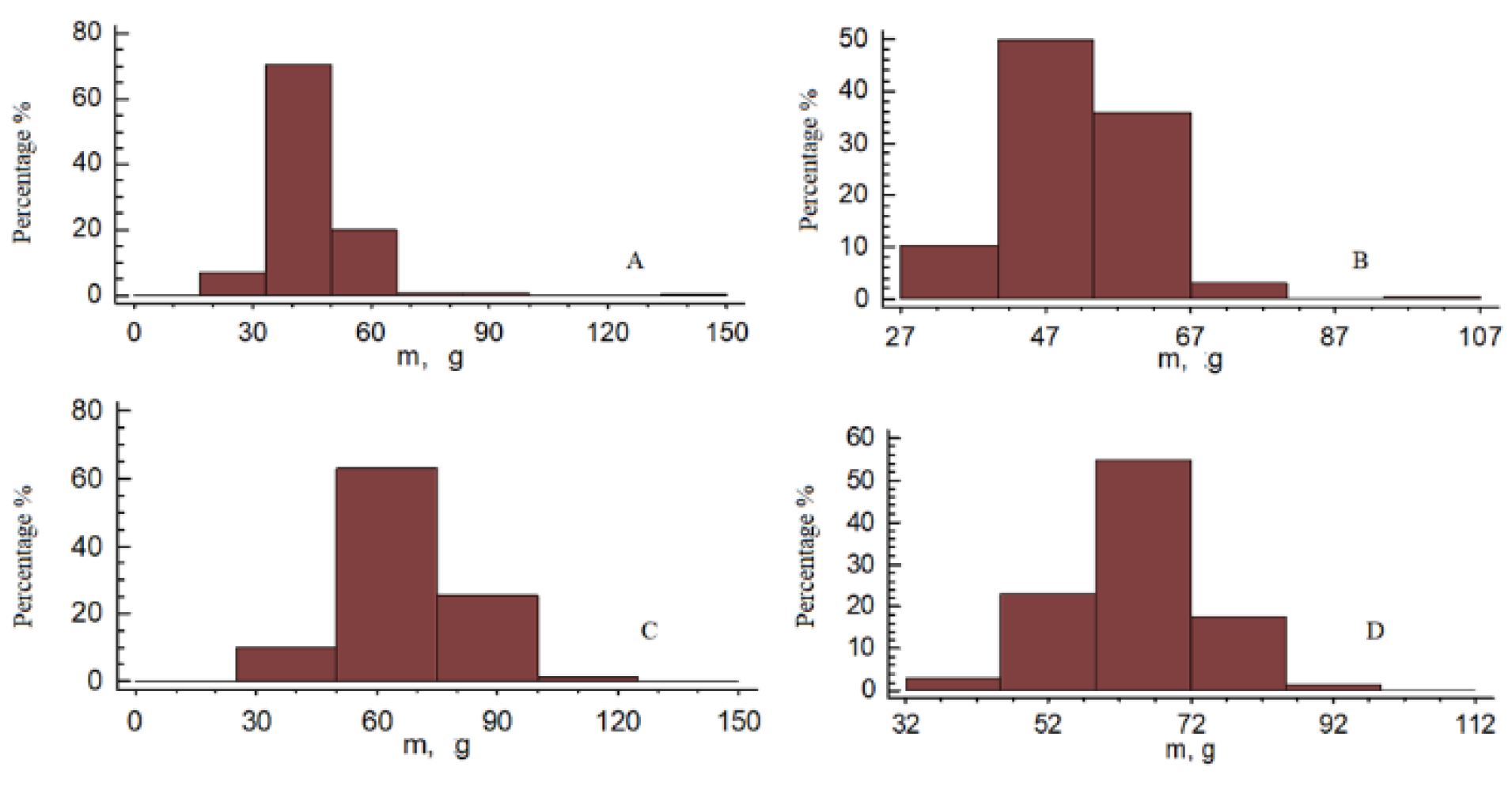

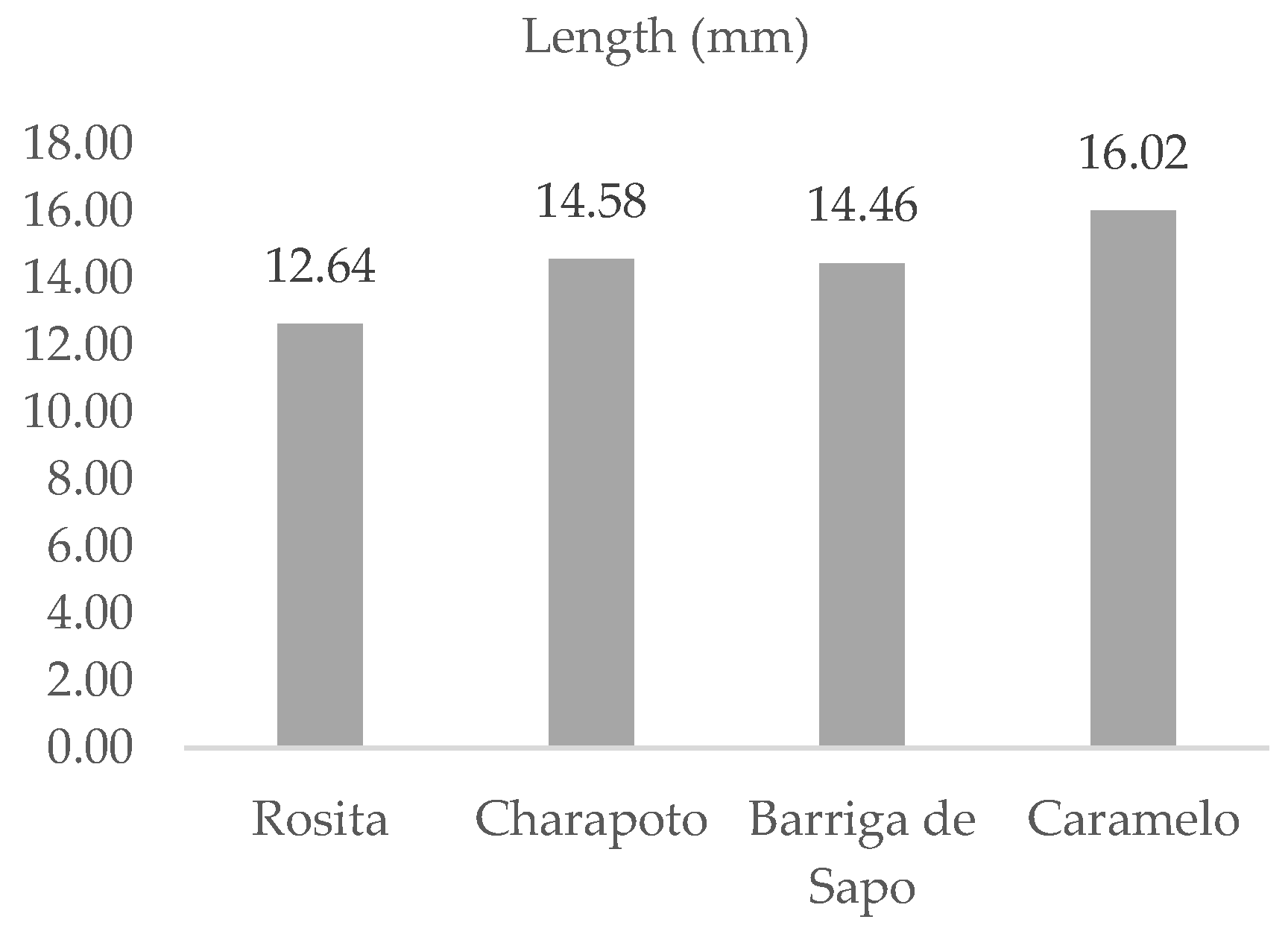

3.1. Physical Properties of Peanut

3.2. Mechanical Properties of Peanut

- Discrete Element Method: Relies on accurate input parameters (e.g., friction, restitution coefficients) for realistic particle interaction simulations [42].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI). Artificial intelligence systems that utilize geometric properties to develop advanced technologies for harvesting and post-harvesting of edible kernels [50].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertioli, D.J., J. Jenkins, J. Clevenger, O. Dudchenko, D. Gao, G. Seijo, S.C. Leal-Bertioli, L. Ren, A.D. Farmer, and M.K. Pandey, The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut Arachis hypogaea. Nat. Genet., 2019. 51(5): p. 877-884. [CrossRef]

- Bertioli, D.J., G. Seijo, F.O. Freitas, J.F. Valls, S.C. Leal-Bertioli, and M.C. Moretzsohn, An overview of peanut and its wild relatives. Plant. Genet. Resour., 2011. 9(1): p. 134-149. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Suárez, M., R.X. Cevallos-Mera, P.J. Lucas-Meza, C.A. Sornoza-Solórzano, C.A. Montes-Rodríguez, and O. González-Cueto, Physical-mechanical properties of peanut (Arachis hypogaea l.) for the design of flat classification surfaces. Rev. Cienc. Tec. Agrop., 2022. 31(2), CU-ID: 2177/v31n2e01.

- Arya, S.S., A.R. Salve, and S. Chauhan, Peanuts as functional food: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol., 2016. 53: p. 31-41. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y., H.J. Kim, Y.Y. Lee, M.H. Kim, J.Y. Lee, M.S. Kang, B.C. Koo, and B.W. Lee, Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of peanut (Arachishypogaea L.) skin extracts of various cultivars in oxidative-damaged HepG2 cells and LPS-induced raw 264.7 macrophages. Food Sci. Nutr., 2021. 9(2): p. 973-984. [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. FAOSTAT. Crops and livestock products. 2025, accessed on: 9 April 2025; Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- USDA. World agricultural production. Foreign agricultural service. Top countries by commodity. 2025, accessed on: April 9 2025; Available from: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/topCountriesByCommodity.

- Akcali, I.D., A. Ince, and E. Guzel, Selected physical properties of peanuts. Int. J. Food Prop., 2006. 9: p. 25-37. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S., R. Sharma, and V. Sardana, Studies on some engineering properties of peanut pod and kernel. J. Agric. Eng. (India), 2011. 48(2): p. 38-42. [CrossRef]

- Fashina, A.B., A. Saleh, and F.B. Akande, Some engineering properties of three selected groundnut (Arachishypogaea L.) varieties cultivated in Nigeria. . Agric. Eng. Int: CIGR Journal, 2014. 16(4): p. 267-277,.

- Gojiya, D., Studies on Physical and Engineering Characteristics of Peanut Kernel. India. Int J Nutr Sci & Food Tech, 2020. 6: p. 2-22,.

- Kiran, C.S., D. Wadikar, K.R. Reddy, and A.D. Semwal, Exploring the potential applications in post-harvest handling and processing of new groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) varieties based on their physicochemical properties. J. Trop. Agric., 2024. 62(2): p. 193-204,.

- Ofori, H., F. Amoah, I.K. Arah, M.-K.A. Piegu, I.A. Aidoo, and E.D.N.A. Commey, Physical properties of selected groundnut (Arachis hypogea L.) varieties and its implication to mechanical handling and processing. Afr. J. Food Sci., 2020. 14(10): p. 353-365. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, H.V. and M. Mathew, Study on physical and engineering properties of groundnut seed for planter development. J. Trop. Agric., 2021. 59(2),.

- Olajide, J. and J. Igbeka, Some physical properties of groundnut kernels. J. Food Eng., 2003. 58(2): p. 201-204. [CrossRef]

- Muchlisyiyah, J., R. Shamsudin, R.K. Basha, R. Shukri, and S. How, The effect of moisture content to the physical properties of long grain paddy (Oryza sativa). Asia-Pac. J. Sci. Technol., 2023. 29(4),.

- Dornelas, K.C., V.R. da Silva, Y.C.C. Pessoa, and J.W.B. do Nascimento, Propriedades físicas e de fluxo de produtos granulares para projeto de silo. Res. Soc. Dev., 2021. 10(10): p. e234101018754. [CrossRef]

- Chenarbon, H.A. and S. Movahhed, Assessment of physical and aerodynamic properties of corn kernel (KSC 704). J. Food Process Eng., 2021. 44(11): p. e13858. [CrossRef]

- Kruszelnicka, W., Study of selected physical-mechanical properties of corn grains important from the point of view of mechanical processing systems designing. Mater., 2021. 14(6): p. 1467. [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H. and L.R. Verma, Determination of friction coefficients of beans and peanuts. Trans. ASABE, 1989. 32(2): p. 0745-0750. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.A.V.d., P.C. Coradi, L.P.R. Teodoro, D.M. Rodrigues, P.E. Teodoro, and R.S.d. Moraes, Multivariate statistical analysis applied to physical properties of soybean seeds cultivars on the post-harvest. Acta Sci. Agron., 2024. 46: p. e63664. [CrossRef]

- Baryeh, E.A., Physical properties of bambara groundnuts. J. Food Eng., 2001. 47(4): p. 321-326. [CrossRef]

- Jideani, V.A. and A.I.O. Jideani, Physical and engineering properties of bambara groundnut seed, in Bambara groundnut: Utilization and Future Prospects, V.A. Jideani and A.I.O. Jideani, Editors. 2021, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 61-74.

- Nkambule, S., T. Workneh, S. Sibanda, K. Alaika, and G. Lagerwall, The effect of moisture contents on the physical properties of both bambara groundnut seeds and pods in South Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev., 2023. 23(6): p. 23817-23834. [CrossRef]

- Kurt, C. and H. Arıoglu, Physical and mechanical properties of some peanut varieties grown in Mediterranean environment. Cercet. Agron. Moldova, 2018. LI(2(174)): p. 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Shengsheng, W., J. Jiangtao, J. Xin, and G. Lingxin, Design and experimental optimization of cleaning system for peanut harvester. INMATEH-Agricultural Engineering, 2019. 57(1): p. 243-252,.

- Khir, R., Z. Pan, G.G. Atungulu, and J.F. Thompson, Characterization of physical and aerodynamic properties of walnuts. Trans. ASABE, 2014. 57(1): p. 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.S.d., A.J.d. Carvalho, W.d.C. Siqueira, M.d.M. Rocha, J.B. Borges, E.d.S. Barbosa, and J.A. Barbosa, Physical properties of grains of cowpea genotypes. Rev. Bras. Engen. Agríc. Ambi., 2022. 27(3): p. 216-222. [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, J.L., N.M. Palacios, D.M. Bravo, and M.J. Alava, Peanut production and its impact on Ecuador’s economy. Rev. C. Soc. , 2024. XXX(4): p. 323-338.,.

- United Nations, The 2030 agenda and the sustainable development goals: an opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2018, Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

- Yohanes, H., M.N. Alfa, E.P. Astin, K. Komariyah, L.K. Hartono, W. Puspantari, Astuti, W.E. Widodo, and W.B. Setianto, Exploring fluidization characteristics and physical-mechanical properties of Indonesian groundnuts (Arachis hypogea). AIP Conf. Proc., 2025. 3166(1). [CrossRef]

- Aydin, C., Some engineering properties of peanut and kernel. J. Food Eng., 2007. 79(3): p. 810-816. [CrossRef]

- ElMasry, G., S. Radwan, M. ElAmir, and R. ElGamal, Investigating the effect of moisture content on some properties of peanut by aid of digital image analysis. Food Bioprod. Process, 2009. 87(4): p. 273-281. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, W.D., A.L.D. Goneli, C.M.A. De Souza, A.A. Gonçalves, and H.C.B. Vilhasanti, Propriedades físicas dos grãos de amendoim durante a secagem. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Ambient., 2014. 18(3): p. 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Bepary, R.H., D. Wadikar, and P. Patki, Engineering properties of rice-bean varieties from North-East India. J. Agric. Eng. (India), 2018. 55(3): p. 32-42. [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, R.A., S.M.A. Radwan, M.S. ElAmir, and G.M.A. El-Masry Aerodynamic properties of some oilseeds crops under different moisture conditions J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng., 2011. 2(5): p. 495-507. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.I., R.K. Ahmad, and I. Lawan, Effect of moisture content on some engineering properties of groundnut pods and kernels Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J., 2017. 19(4): p. 200-208,.

- Soyoye, B.O., O.C. Ademosun, and L.A.S. Agbetoye, Determination of some physical and mechanical properties of soybean and maize in relation to planter design Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. , 2018. 20(1): p. 81-89,.

- POWDERPROCESS. Ángulo de reposo: visión general. 2024, accessed on: 29 de abril 2025; Available from: https://powderprocess.net/ES/Angulo_De_Reposo.html.

- Galedar, M.N., A. Tabatabaeefar, A. Jafari, A. Sharifi, S.S. Mohtasebi, and H. Fadaei, Moisture dependent geometric and mechanical properties of wild pistachio (Pistaciavera L.) nut and kernel. Int. J. Food Prop. , 2010. 13: p. 1323-1338. [CrossRef]

- Ospina, J.E., Características físico mecánicas y análisis de calidad de granos. 2001, Bogotá: Univ. Nacional de Colombia.

- Chen, H., H. Lin, X. Song, F. Zhang, F. Dai, T. Yang, and B. Li, Study on the contact parameter calibration of the maize kernel polyhedral Discrete Element Model. Agric., 2024. 14(9): p. 1644. [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, B., Introduction to tribology. Second edition. Tribology Series. Vol. 56. 2013, Hoboken, Nueva Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Gupta, R. and S. Das, Friction coefficients of sunflower seed and kernel on various structural surfaces. J. Agric. Eng. Res., 1998. 71(2): p. 175-180. [CrossRef]

- Asli-Ardeh, E.A., Y. Abbaspour-Gilandeh, and S. Shojaei, Determination of dynamic friction coefficient of paddy grains on different surfaces. Int. Agrophys., 2010. 24(2): p. 101-105,.

- Tang, H., G. Zhu, Z. Sun, C. Xu, and J. Wang, Impact damage evolution rules of maize kernel based on FEM. Biosys. Eng., 2024. 247: p. 162-174. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., G. Zhu, Z. Wang, W. Xu, C. Xu, and J. Wang, Prediction method for maize kernel impact breakage based on high-speed camera and FEM. Powder Technol., 2024. 444: p. 120002. [CrossRef]

- Ling, J., M. Gu, W. Luo, H. Shen, Z. Hu, F. Gu, F. Wu, P. Zhang, and H. Xu, Simulation analysis and test of a cleaning device for a fresh-peanut-picking combine harvester based on Computational Fluid Dynamics–Discrete Element Method coupling. Agric., 2024. 14(9): p. 1594. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., Y. Jin, W. Luo, F. Wu, L. Shi, F. Gu, M. Cao, and Z. Hu, Measurement and CFD-DEM simulation of suspension velocity of peanut and clay-heavy soil at harvest time. Agron., 2023. 13(7): p. 1735. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., D. Wang, T. Zhu, Y. Tao, and C. Ni, Review of deep learning-based methods for non-destructive evaluation of agricultural products. Biosyst. Eng., 2024. 245: p. 56-83. [CrossRef]

| Variety | Cases | Average | Homogeneous Groups |

| Rosita | 200 | 44.865 | X |

| Charapotó | 200 | 52.15 | X |

| Caramelo | 200 | 64.385 | X |

| Barriga de Sapo | 200 | 68.375 | X |

| Variety | Cases | Average | Homogeneous Groups |

| Rosita | 200 | 7.6908 | X |

| Charapotó | 200 | 7.72975 | X |

| Caramelo | 200 | 8.09165 | X |

| Barriga de Sapo | 200 | 9.27265 | X |

| Coefficient | Surface | Rosita | Caramelo | Charapotó | Barriga de Sapo |

| Stainless steel | 0,61 | 0,73 | 0,71 | 0,82 | |

| Rubber | 0,94 | 0,95 | 0,99 | 1,10 | |

| Carbon steel | 0,73 | 0,71 | 0,78 | 0,79 | |

| Stainless steel | 0,51 | 0,64 | 0,67 | 0,61 | |

| Rubber | 0,76 | 0,79 | 0,95 | 0,87 | |

| Carbon steel | 0,65 | 0,55 | 0,63 | 0,62 | |

| Stainless steel | 0,48 | 0,43 | 0,43 | 0,26 | |

| Rubber | 0,55 | 0,50 | 0,54 | 0,33 | |

| Carbon steel | 0,46 | 0,41 | 0,45 | 0,22 | |

| Stainless steel | 0,38 | 0,32 | 0,31 | 0,19 | |

| Rubber | 0,38 | 0,36 | 0,31 | 0,22 | |

| Carbon steel | 0,35 | 0,32 | 0,31 | 0,13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).