Submitted:

01 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

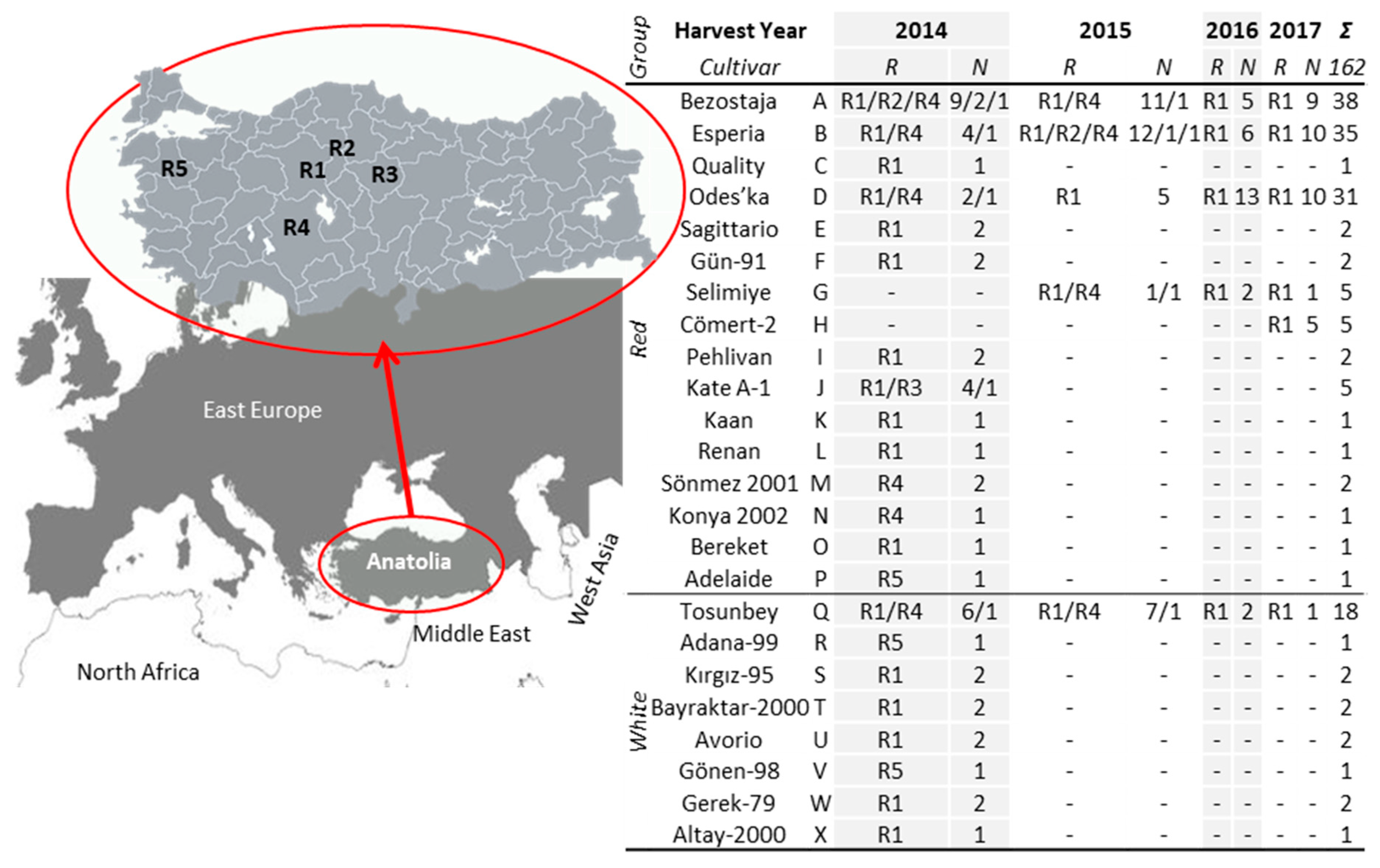

2. Materials and Methods

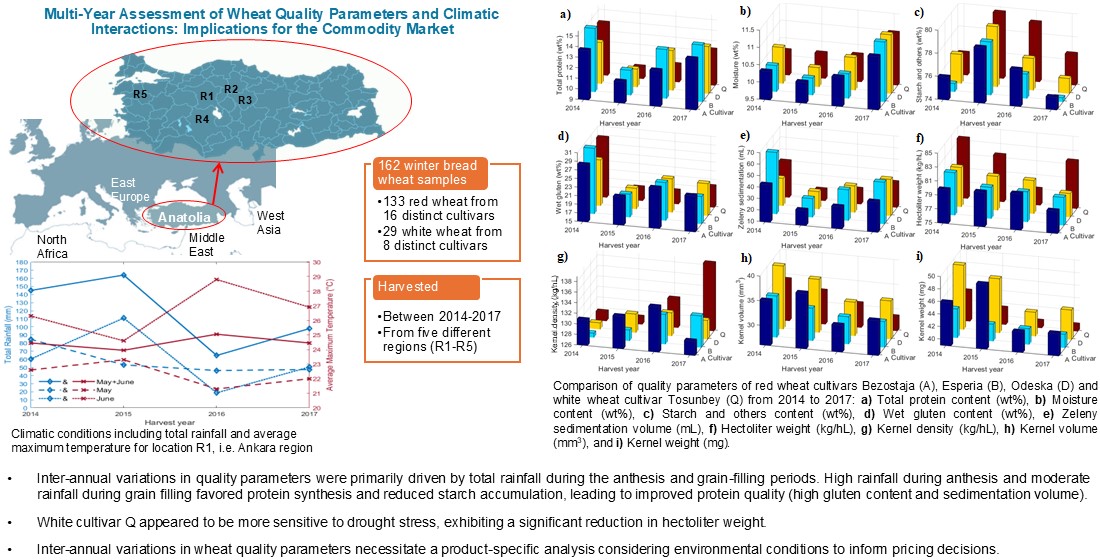

2.1. Types of Bread Wheat

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Analytical Analyses

2.4. Physical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

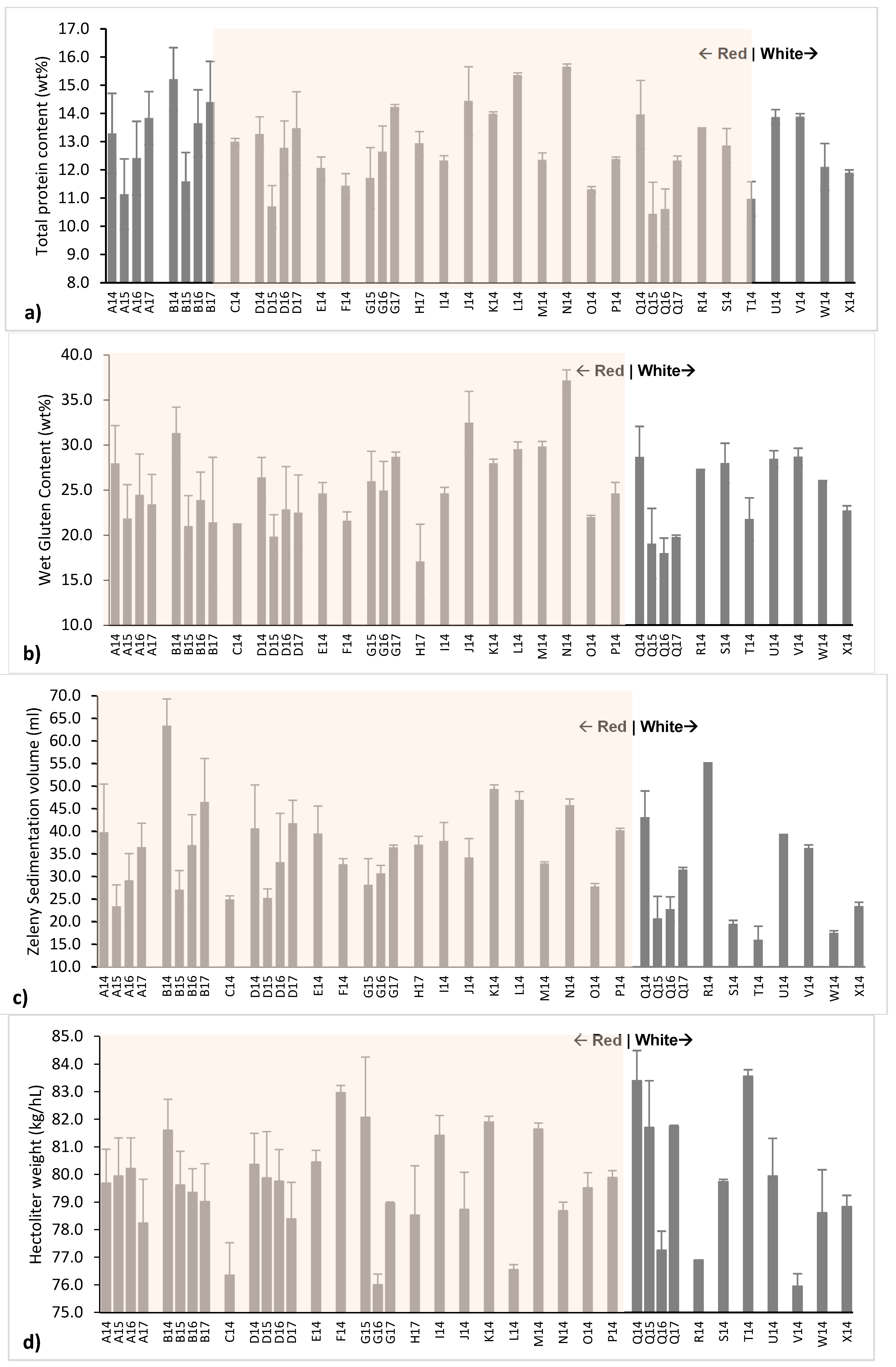

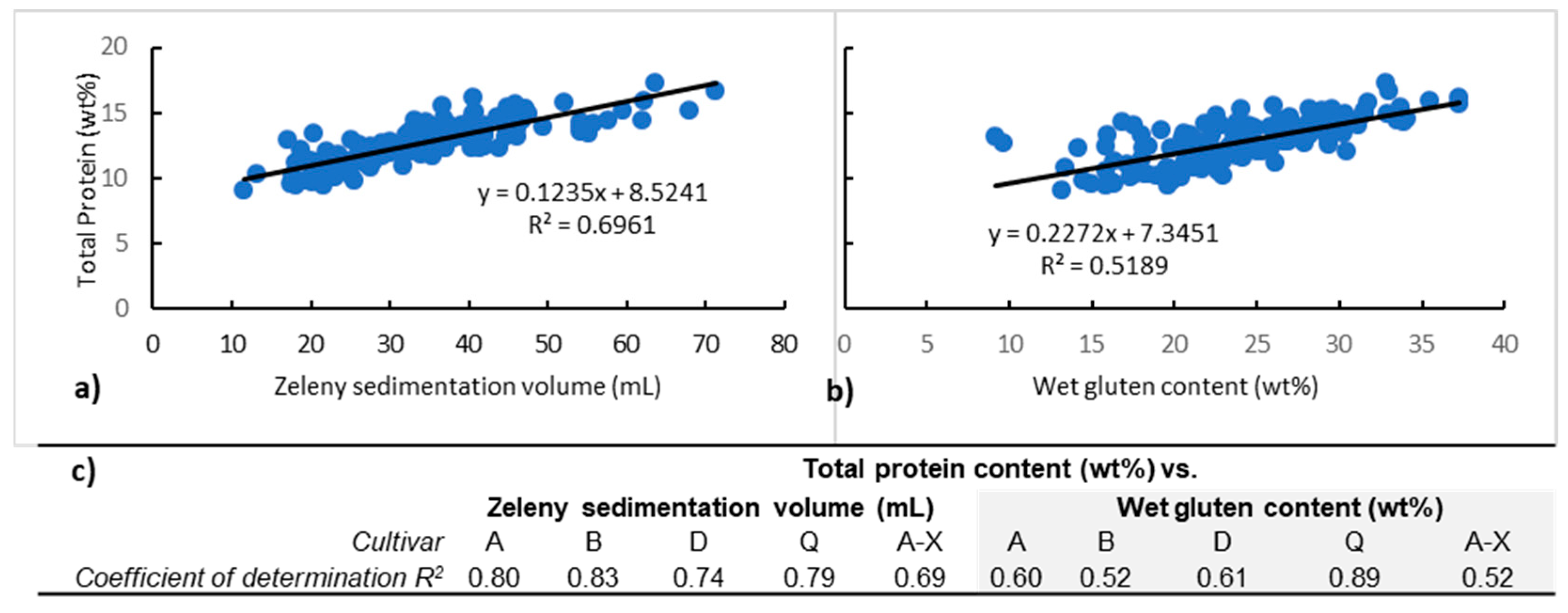

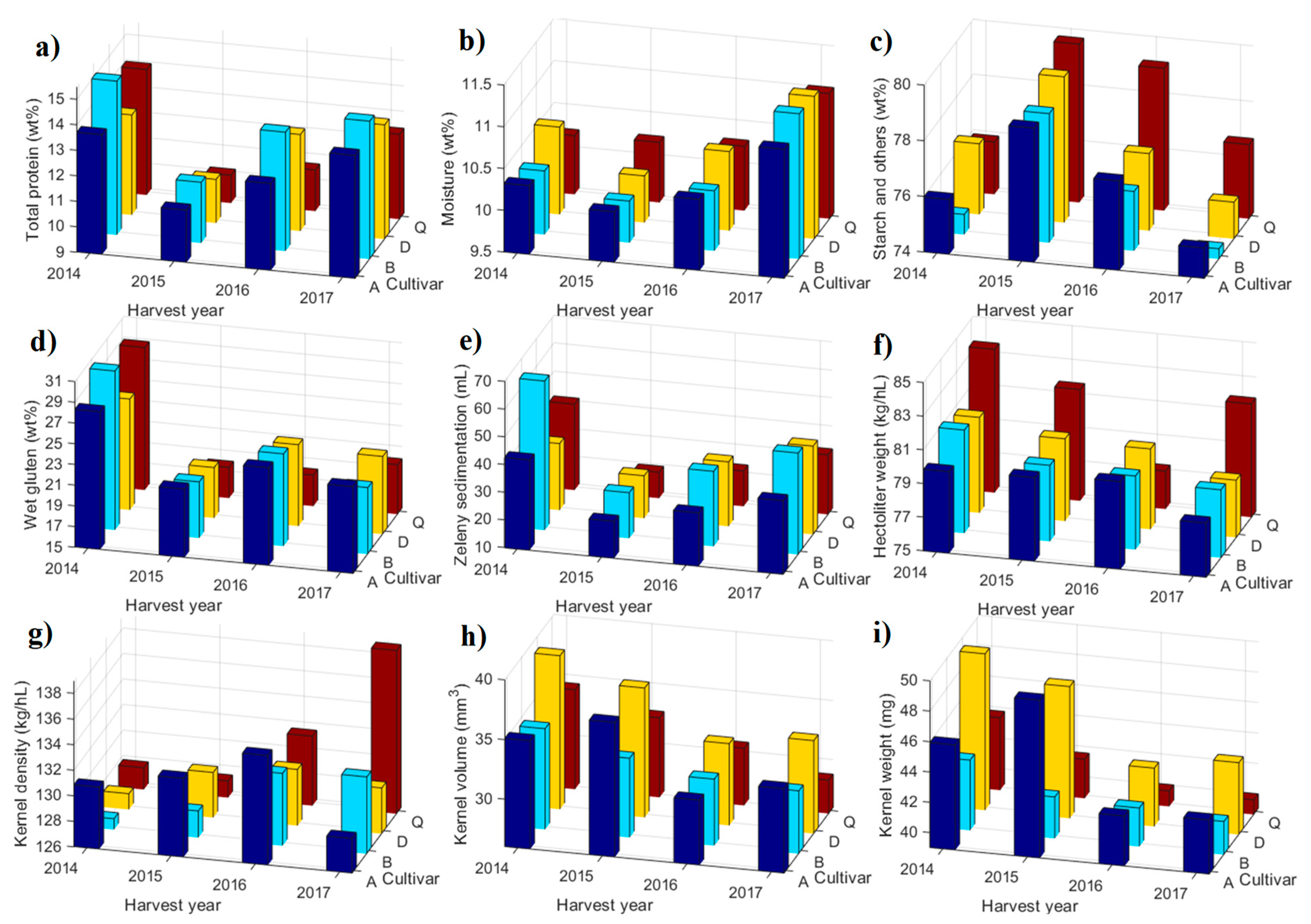

3.1. Analytical Analyses

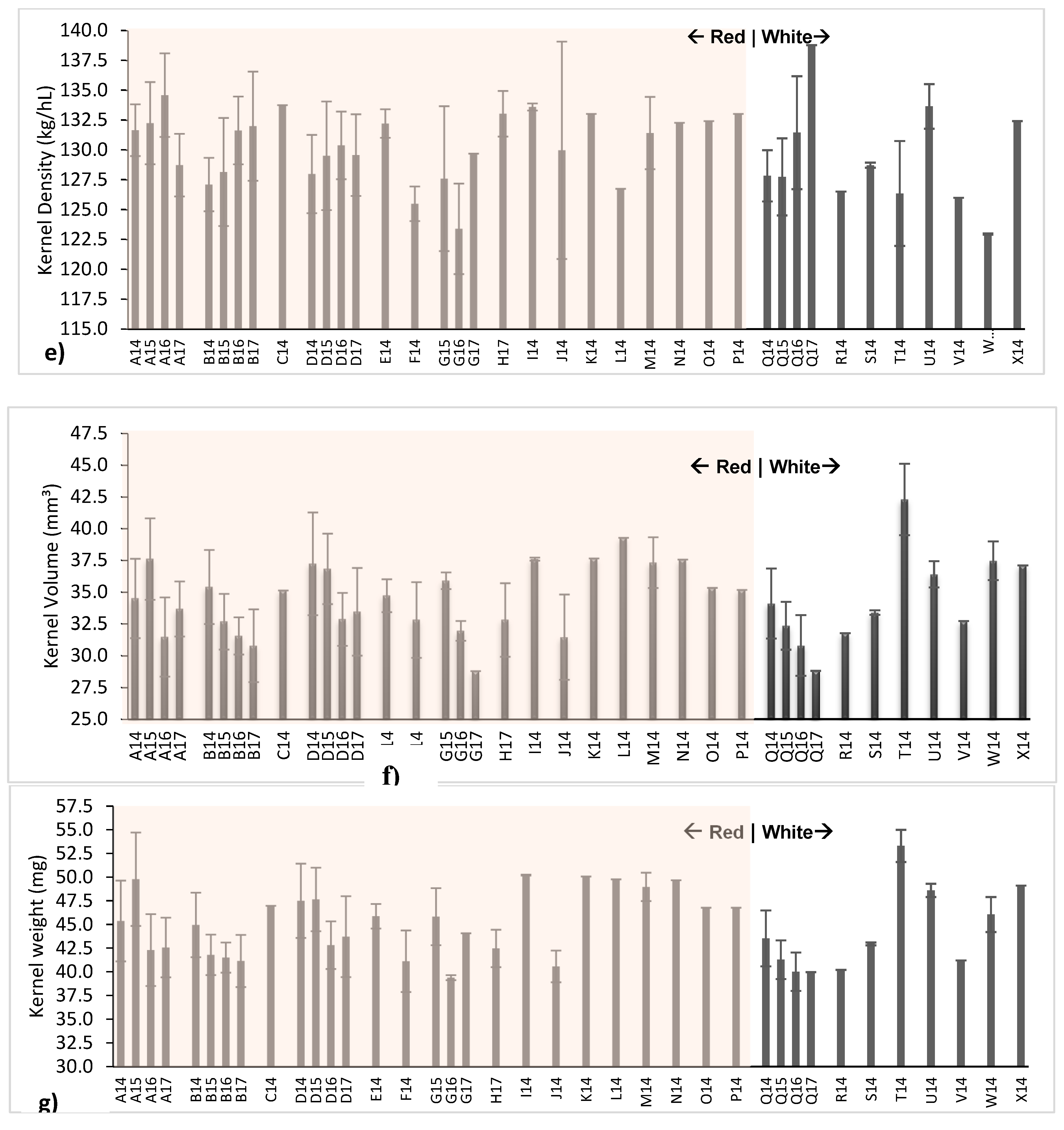

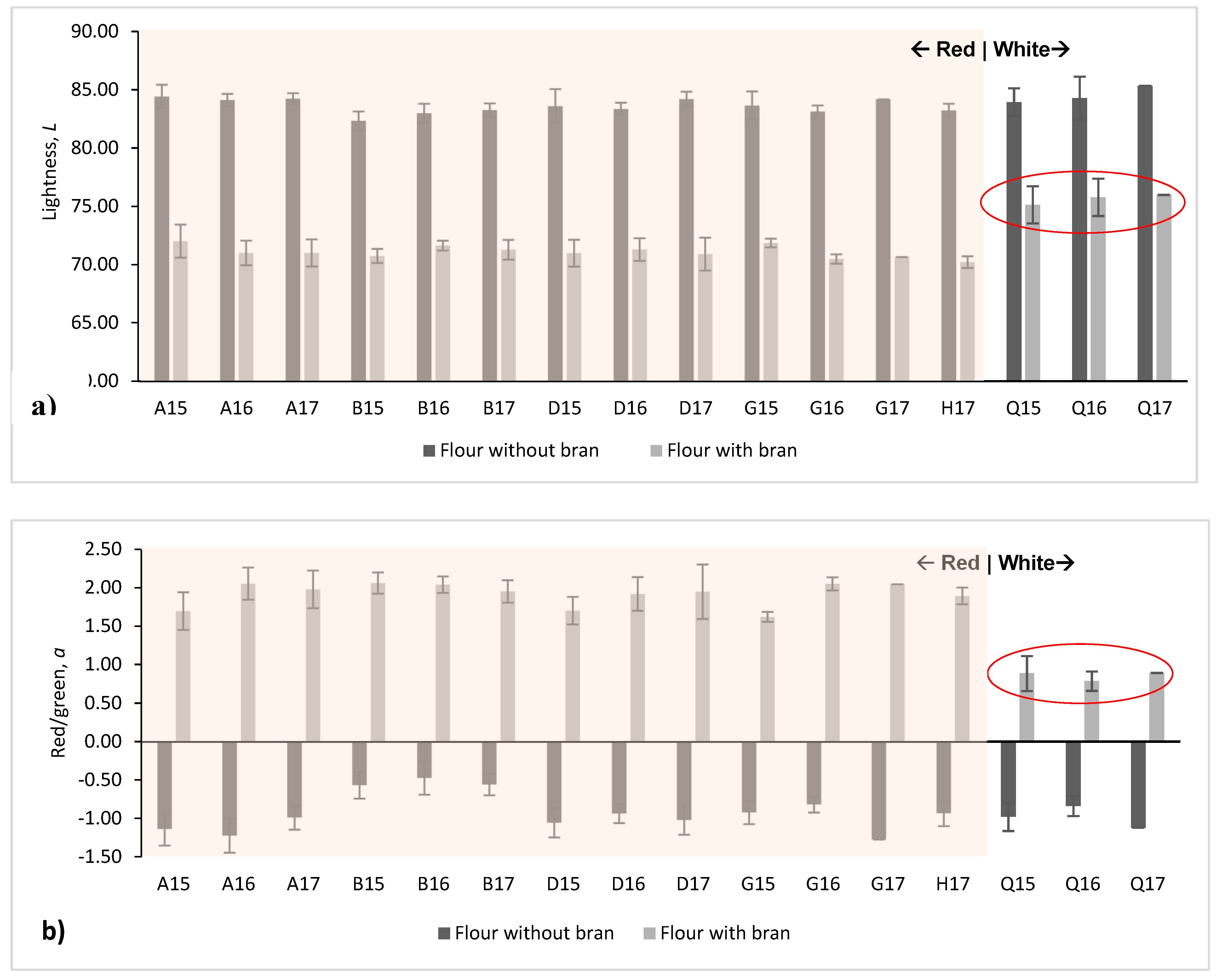

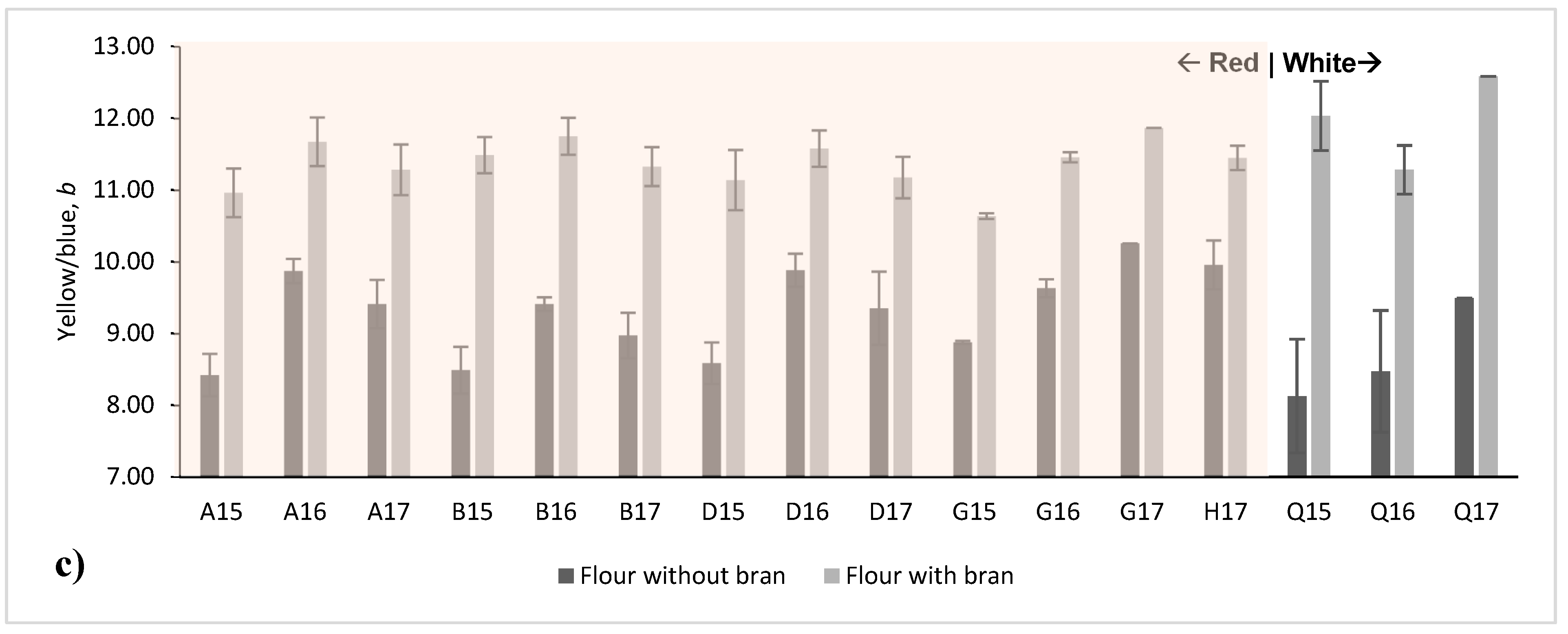

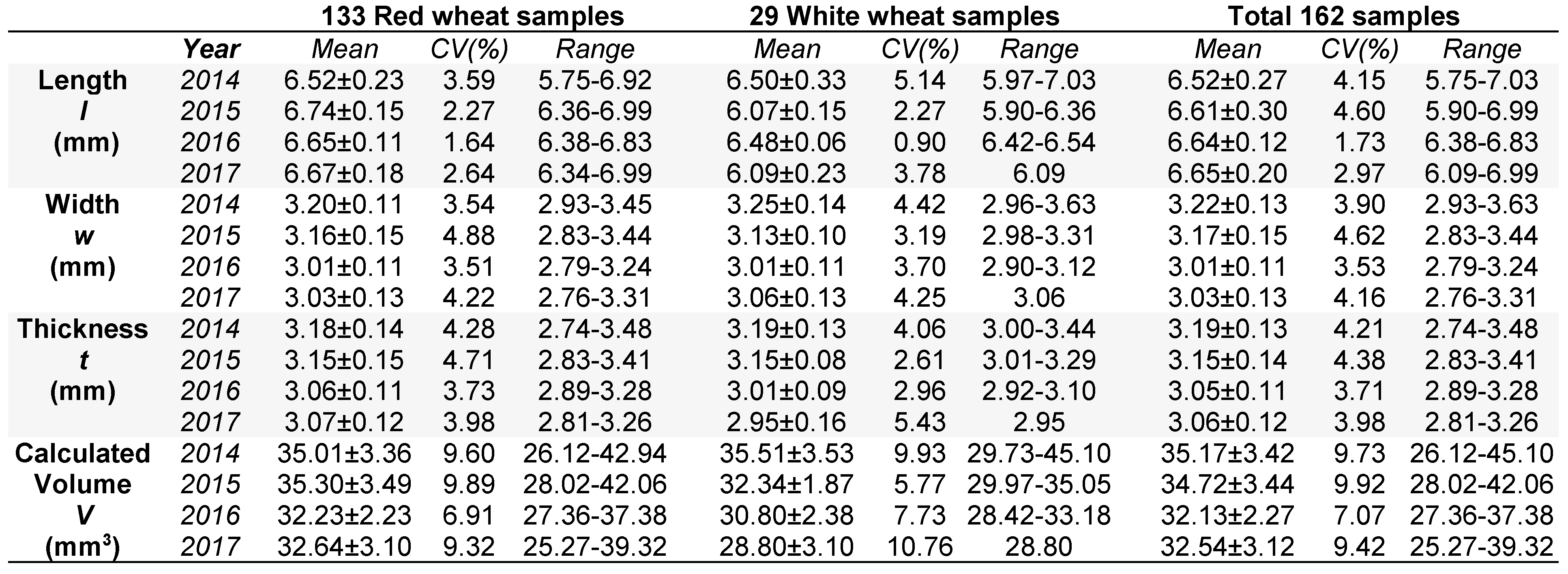

3.2. Physical Analyses

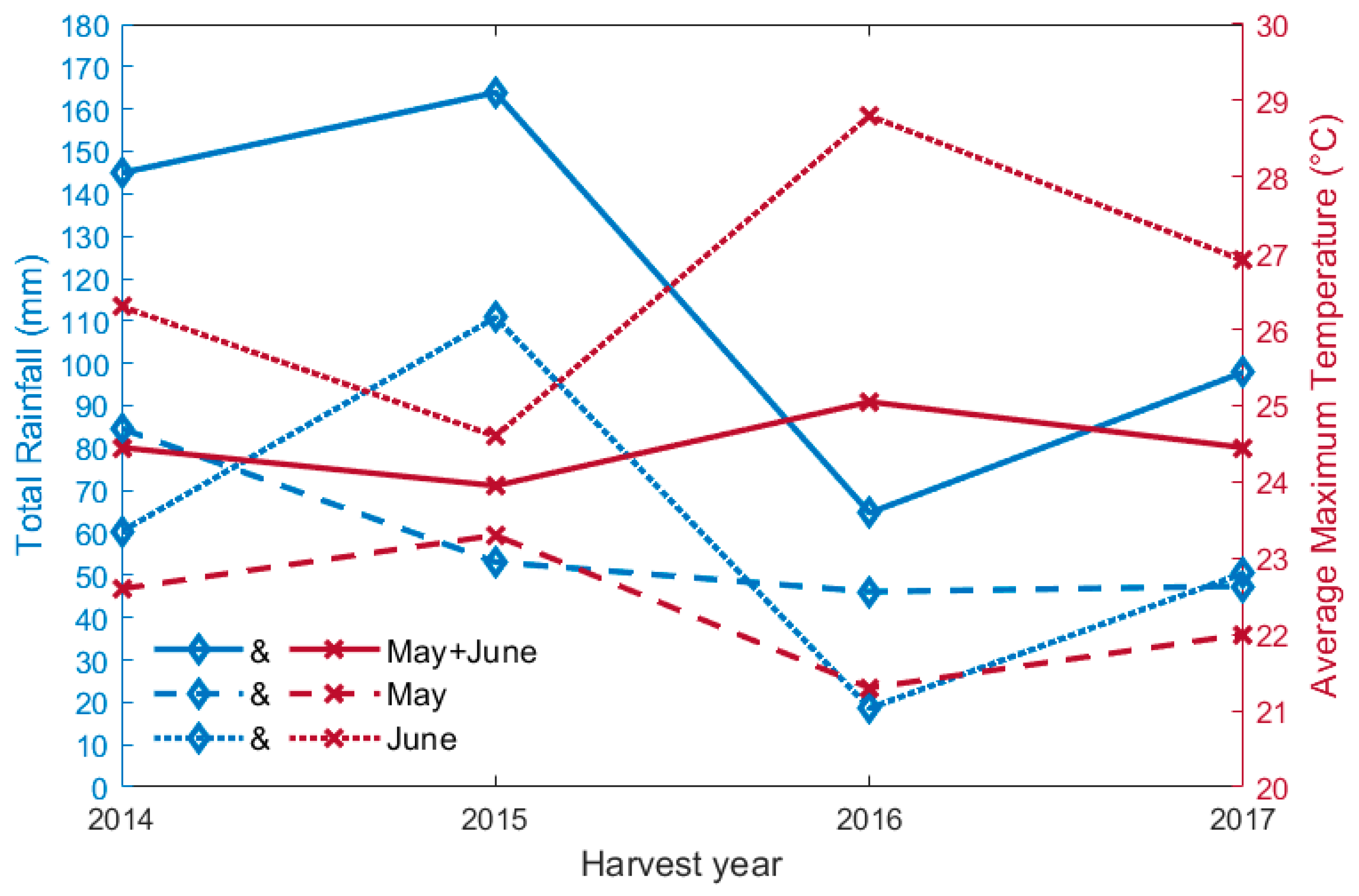

3.3. Analyses Based on Harvest Year and Climatic Conditions

3.3.1. Climatic trends

3.3.2. Wet conditions in 2014 and 2015

3.3.3. Dry Conditions in 2016 and 2017

3.3.4. Cultivar Specific Indications

4. Conclusions

- Significant inter-cultivar variation was observed in key quality parameters, such as Zeleny sedimentation volume, wet gluten content, total protein content, kernel weight, and volume. These pronounced differences were influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. While grain color, as red or white, was not a reliable predictor of quality, as some white cultivars outperformed red cultivars in protein content, gluten content, and sedimentation volume, specific cultivars exhibited consistent superior or inferior performance across various quality parameters.

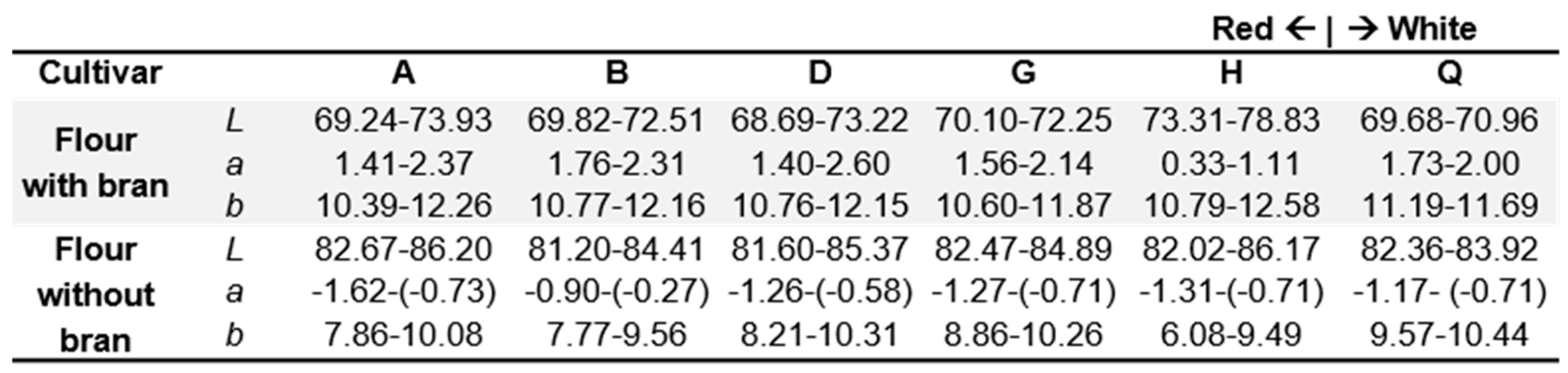

- Color measurements proved no significant relation between redness and yellowness parameters of whole wheat flours and analytical quality parameters. Results indicated that color pigments are primarily located in the bran layer, making them less indicative of the quality of the kernel’s bulk content. Color differences observed between different wheat cultivars suggest a genetic basis for these variations, which persisted across multiple years. However, yellowness, influenced by carotenoid pigments, seems to be more susceptible to environmental factors.

- Hectoliter weight was influenced by multiple factors, including kernel dimensions, volume, weight, density, and moisture content. While environmental factors affected these parameters, the impact varied between cultivars. Cumulative of the variations in these parameters did not significantly affect the hectoliter weight of red cultivars, although insignificant reduction was observed during warmer climates due to a reduction in both grain weight and volume, with the decrease in weight being more pronounced. White cultivar Q appeared to be more sensitive to drought stress, exhibiting a significant reduction in hectoliter weight.

- Kernel volume and weight did not correlate with protein content, due to accumulation of varying amounts of starch based on environmental conditions. Inter-annual variations in quality parameters were primarily driven by total rainfall during the anthesis and grain-filling periods. High rainfall during anthesis and moderate rainfall during grain filling favored protein synthesis and reduced starch accumulation, leading to improved protein quality (high gluten content and sedimentation volume). Conversely, excessive rainfall during grain filling resulted in increased starch accumulation and diluted protein content. Environmental variations did not affect the ratio of gluten proteins to total protein, even though overall content fluctuated.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonfil, D.J.; Posner, E.S. Can bread wheat quality be determined by gluten index? J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.H.; Sun, D.; Nevo, E. Domestication Evolution, Genetics and Genomics in Wheat. Molecular Breeding 2011, 28, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TurkStat. Cereals and Other Crop Products Balance Sheets. TUIK: 2023; Vol. 2024.

- Williams, P.; Sobering, D.; Antoniszyn, J. Protein Testing Methods at the Canadian Grain Commission. Proceedings of Wheat Protein Symposium, Saskatoon.

- Pawlinsky, T.; Williams, P. Prediction of Wheat Bread-Baking Functionality in Whole Kernels, Using Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy. Journal of Near Infrared Spectroscopy 1998, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Halford, N.G.; Lafiandra, D. Genetics of Wheat Gluten Proteins. In Advances in Genetics, Hall, J.C., Dunlap, J.C., Friedmann, T., Eds. Academic Press: 2003; Vol. 49, pp. 111-184.

- Wieser, H.; Seilmeier, W. The Influence of Nitrogen Fertilisation on Quantities and Proportions of Different Protein Types in Wheat Flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 76, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, D.; Šimić, G.; Dvojkovic, K.; Ivić, M.; Plavšin, I.; Novoselović, D. Gluten Protein Compositional Changes in Response to Nitrogen Application Rate. Agronomy 2021, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolfi, V.; D'Auria, G.; Nicolai, M.A.; Nitride, C.; Blandino, M.; Ferranti, P. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on the expression of protein in wheat and tritordeum varieties using a proteomic approach. Food Res Int 2021, 148, 110617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, N.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Y. Effect of high-nitrogen fertilizer on gliadin and glutenin subproteomes during kernel development in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). The Crop Journal 2020, 8, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triboi, E.; Martre, P.; Triboi-Blondel, A.M. Environmentally-Induced Changes in Protein Composition in Developing Grains of Wheat are Related to Changes in Total Protein Content. Journal of Experimental Botany 2003, 54, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, H.; Koehler, P.; Scherf, K.A. Chemistry of wheat gluten proteins: Quantitative composition. Cereal Chemistry 2023, 100, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruskova, M.; Famera, O. Prediction of Wheat and Flour Zeleny Sedimentation Value Using NIR Technique. Czech J Food Sci 2003, 21, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, I.; Anjum, F.M.; Butt, M.S.; Sultan, J.I. Gluten Quality Prediction and Correlation Studies in Spring Wheats Journal of Food Quality 2007, 30, 438-449. 30. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, F.M.; Walker, C.E. Review on the Significance of Starch and Protein to Wheat Kernel Hardness. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1991, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grausgruber, H.; Oberforster, M.; Werteker, M.; Ruckenbauer, P.; Vollmann, J. Stability of Quality Traits in Austrian-Grown Winter Wheats. Field Crops Research 2000, 66, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, I.; Akay, H.; Mut, Z.; Arslan, H.; Ozturk, E.; Erbas Kose, O.D.; Kiremit, M.S. Effects of Different Water Table Depth and Salinity Levels on Quality Traits of Bread Wheat. Agriculture 2021, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrusková, M.; Skodova, V.; Blazek, J. Wheat sedimentation values and falling number. Czech. J. Food Sci. 2004, 22, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt Polat, P.O.; Yagdı, K. Investigations on the Relationships Between Some Quality Characteristics in a Winter Wheat Population. Turkish Journal Of Field Crops 2017, 22, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, R.; Kuzina, F.D. Wheat: Relations Between Some Physical and Chemical Properties. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 1979, 59, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, S.; Sahin, M.; Gocmen Akcacik, A.; Yakisir, E. Effect of Different Grain Size on the Quality of Bread Wheat. Selcuk Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences 2014, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, M.; Gocmen Akcacik, A.; Aydogan, S.; Ozer, E. Ekmeklik Bugday Tane Boyutunun Kalite Ozellikleri Uzerine Etkisi. Anadolu Ege Tarımsal Arastirma Enstitusu Dergisi 2013, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, D.; Tiwari, V. Influence of varying crop seasons and locations in sustaining wheat yield under two agro-climatically diverse zones of India. Field Crops Research 2016, 196, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Kaur, S.; Sharma, A.; Kumari, A.; Tiwari, V.; Sharma, S.; Kapoor, P.; Sheoran, B.; Goyal, A.; Krishania, M. Rising Demand for Healthy Foods-Anthocyanin Biofortified Colored Wheat Is a New Research Trend. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, C.; Ibba, M.I.; Alvarez, J.B.; Sissons, M.; Morris, C. Wheat Quality. In Wheat Improvement: Food Security in a Changing Climate, Reynolds, M.P., Braun, H.J., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; 10.1007/978-3-030-90673-3_11pp. 177-193.

- Rozbicki, J.; Ceglińska, A.; Gozdowski, D.; Jakubczak, M.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Mądry, W.; Golba, J.; Piechociński, M.; Sobczyński, G.; Studnicki, M.; et al. Influence of the Cultivar, Environment and Management on the Grain Yield and Bread-Making Quality in Winter Wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 61, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagella, Z.; Giuliani, M.M.; Giuzio, L.; Volpi, C.; Masci, S. Influence of Water Deficit on Durum Wheat Storage Protein Composition and Technological Quality. European Journal of Agronomy 2010, 33, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asana, R.D.; Williams, R.F. Effect of Temperature Stress on Grain Development in Wheat. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1965, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, I.; Evans, L.T.; Cook, M.G.; Wardlaw, I.F. Factors Influencing Rate and Duration of Grain Filling in Wheat. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 1977, 4, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, B.; Corbellini, M.; Ciaffi, M.; Lafiandra, D.; De Stefanis, E.; Sgrulletta, D.; Boggini, G.; Di Fonzo, N. Effects of Heat Shock During Grain Filling on Bread and Durum Wheats. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1365–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, P.J.; Moss, H.J. Some Effects of Temperature Regime During Grain Filling on Wheat Quality. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1990, 41, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Lestache, E.; Lopez-Bellido, R.J.; Lopez-Bellido, L. Effect of N rate, Timing and Splitting and N Type on Bread-making Quality in Hard Red Spring Wheat Under Rainfed Mediterranean Conditions. Field Crops Research 2004, 85, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, P.; Blackwell, R.D. The Effect of Drought on the Water Use and Yield of Two Spring Wheat Genotypes. The Journal of Agricultural Science 1981, 96, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Map of Europe. Availabe online: https://vemaps.com/europe-continent/eu-c-03 (accessed on 25.04.2024). (accessed on 25.04.2024).

- Map of Turkey with Provinces. Availabe online: https://vemaps.com/turkey/tr-04 (accessed on 25.04.2024). (accessed on 25.04.2024).

- Gastón, A.a.L.; Abalone, R.M.; Giner, S.A. Wheat drying kinetics. Diffusivities for sphere and ellipsoid by finite elements. Journal of Food Engineering 2002, 52, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, M.; Żuk-Gołaszewska, K.; Kwiatkowski, D. Influence of variety on selected physical and mechanical properties of wheat. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 47, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyanchuk, A.M.; Grundas, S.; Velikanov, L.P. Identification of Wheat Morphotype and Variety Based on XRay Images of Kernels. In Advances in Agrophysical Research, Grundas, S., Stepniewski, A., Eds. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2013; 10.5772/52236pp. 223-267.

- Zhou, Q.; Wu, X.J.; Xin, L.; Jiang, H.D.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Jiang, D. Waterlogging and simulated acid rain after anthesis deteriorate starch quality in wheat grain. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniskina, T.S.; Sudarikov, K.A.; Prisazhnoy, N.A.; Besaliev, I.N.; Panfilov, A.A.; Reger, N.S.; Kormilitsyna, T.; Novikova, A.A.; Gulevich, A.A.; Lebedev, S.V.; et al. Phenotyping Wheat Kernel Symmetry as a Consequence of Different Agronomic Practices. Symmetry-Basel 2024, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojic, M.; Rakic, D.; Lazic, Z. Chemometric optimization of the robustness of the near infrared spectroscopic method in wheat quality control. Talanta 2015, 131, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslar, M.; Ertugay, M.F. Determination of protein and gluten quality-related parameters of wheat flour using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS). Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2011, 35, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeshu, Y.; Kasahun, C. Fast and non- destructive multivariate test method to predict bread wheat grain major quality parameters. International Journal of Food Properties 2024, 27, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, F. Tailoring the Structure-Function Relationship in Wheat Gluten Processing, Genotype and Environment Effects in Bio-Based Materials. Doctoral Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Alnarp, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yabwalo, D.N.; Berzonsky, W.A.; Brabec, D.; Pearson, T.; Glover, K.D.; Kleinjan, J.L. Impact of grain morphology and the genotype by environment interactions on test weight of spring and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica 2018, 214, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petingco, M.C.; Casada, M.E.; Maghirang, R.G.; Thompson, S.A.; McNeill, S.G.; Montross, M.D.; Turner, A.P. Influence of Kernel Shape and Size on the Packing Ratio and Compressibility of Hard Red Wheat. Trans. ASABE 2018, 61, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, R.H.; Bremer, E.; Grant, C.A.; Johnston, A.M.; DeMulder, J.; Middleton, A.B. In-crop application effect of nitrogen fertilizer on grain protein concentration of spring wheat in the Canadian prairies. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 2006, 86, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.; Fifield, C.C.; Hartsing, T. Factors Related to the Flour-Yielding Capacity of Wheat. The Northwestern Miller 1965, 272, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, A.D. Grain Size And Morphology: Implications For Quality. In Wheat Structure, Schofield, J.D., Ed. Woodhead Publishing: 1995; pp. 19-24.

- Wang, K.; Fu, B.X. Inter-Relationships Between Test Weight, Thousand Kernel Weight, Kernel Size Distribution and Their Effects on Durum Wheat Milling, Semolina Composition and Pasta Processing Quality. Foods 2020, 9, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.A. Number of Kernels in Wheat Crops and the Influence of Solar-Radiation and Temperature. J. Agric. Sci. 1985, 105, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y. Winter Wheat Adaptation to Climate Change in Turkey. Agronomy-Basel 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Total Rainfall and Average Maximum Temperature Data Sets. Service, T.S.M., Ed. Turkish State Meteorological Service: 2024. Total Rainfall and Average Maximum Temperature Data Sets. Service, T.S.M. (Ed.).

- Gutierrez, M.; Reynolds, M.P.; Raun, W.R.; Stone, M.L.; Klatt, A.R. Spectral Water Indices for Assessing Yield in Elite Bread Wheat Genotypes under Well-Irrigated, Water-Stressed, and High-Temperature Conditions. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuresova, G.; Haberle, J.; Svoboda, P.; Wollnerova, J.; Moulik, M.; Chrpova, J.; Raimanova, I. Effects of Post-Anthesis Drought and Irrigation on Grain Yield, Canopy Temperature and <SUP>13</SUP>C Discrimination in Common Wheat, Spelt, and Einkorn. Agronomy-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, H.M.U.; Sial, M.A.; Bux, H. Evaluation of Bread Wheat Genotypes for Water Stress Tolerance Using Agronomic Traits. Acta Agrobotanica 2020, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Reynolds, M.P.; Trethowan, R.; González-Santoyo, H.; Peña, R.J.; Zapata, F. Relationship between grain yield and carbon isotope discrimination in bread wheat under four water regimes. European Journal of Agronomy 2005, 22, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Bramley, H.; Mahmood, T.; Trethowan, R. Morpho-physiological responses of diverse emmer wheat genotypes to terminal water stress. Cereal Research Communications 2022, 50, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, I.; Sehirali, S.; Orta, H.; Erdem, T.; Erdem, Y.; Yorgancilar, Ö. Effect of different water stresses on the yield and yield components of winter wheat. Cereal Research Communications 2004, 32, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.; Jenner, C. Differential responses to high temperatures of starch and nitrogen accumulation in the grain of four cultivars of wheat. Functional Plant Biology 1985, 12, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.A.; Davidson, H.R.; Winkleman, G.E. Effect of Nitrogen, Temperature, Growth Stage and Duration of Moisture Stress on Yield Components and Protein Content of Manitou Spring Wheat. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 1981, 61, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmoral, L.F.G.; Boujenna, A.; Yanez, J.A.; Ramos, J.M. Forage Production, Grain-Yield, and Protein-Content in Dual-Purpose Triticale Grown for Both Grain and Forage. Agronomy Journal 1995, 87, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Figares, I.; Marinetto, J.; Royo, C.; Ramos, J.M.; Garcia del Moral, L.F. Amino-Acid Composition and Protein and Carbohydrate Accumulation in the Grain of Triticale Grown under Terminal Water Stress Simulated by a Senescing Agent. J. Cereal Sci. 2000, 32, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, C.; Ugalde, T.; Aspinall, D. The physiology of starch and protein deposition in the endosperm of wheat. Functional Plant Biology 1991, 18, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rharrabti, Y.; Elhani, S.; Martos-Núñez, V.; García del Moral, L.F. Protein and Lysine Content, Grain Yield, and Other Technological Traits in Durum Wheat under Mediterranean Conditions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2001, 49, 3802–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Jiang, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Dai, T.; Jiang, D. Reducing Nitrogen Rate and Increasing Plant Density Accomplished High Yields with Satisfied Grain Quality of Soft Wheat via Modifying the Free Amino Acid Supply and Storage Protein Gene Expression. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 2146–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Zhao, C.F.; Zhang, M.X.; Sun, C.J.; Liu, X.X.; Hu, J.L.; Zeeshan, M.; Zaid, A.; Dai, T.B.; Tian, Z.W. Nitrogen enhances the effect of pre-drought priming against post-anthesis drought stress by regulating starch and protein formation in wheat. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwadzingeni, L.; Shimelis, H.; Rees, D.J.G.; Tsilo, T.J. Genome-wide association analysis of agronomic traits in wheat under drought-stressed and non-stressed conditions. Plos One 2017, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shi, K.; Lu, W.P.; Lu, D.L. Effects of Post-silking Shading Stress on Enzymatic Activities and Phytohormone Contents During Grain Development in Spring Maize. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1060–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2014 | CV% | 2015 | CV% | 2016 | CV% | 2017 | CV% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Protein Content (wt%) |

All | 13.38±1.49 | 11.14 | 11.13±1.18 | 10.60 | 12.74±1.28 | 10.05 | 13.74±1.26 | 9.17 |

| Red | 13.49±1.54 | 11.42 | 11.30±1.13 | 10.00 | 12.97±1.15 | 8.87 | 13.78±1.25 | 9.07 | |

| White | 13.15±1.35 | 10.27 | 10.44±1.13 | 10.82 | 10.62±0.72 | 6.78 | 12.33±0.17 | 1.38 | |

|

Moisture Content (wt%) |

All | 10.41±0.33 | 3.17 | 10.06± 0.22 | 2.19 | 10.36±0.25 | 2.41 | 11.17±0.22 | 1.97 |

| Red | 10.41±0.32 | 3.07 | 10.03± 0.22 | 2.19 | 10.36±0.26 | 2.51 | 11.18±0.23 | 2.06 | |

| White | 10.42±0.34 | 3.26 | 10.18± 0.13 | 1.28 | 10.27±0.00 | 0.00 | 11.00±0.00 | 0.00 | |

|

Starch and Others Content (wt%) |

All | 76.21±1.43 | 1.88 | 78.81±1.08 | 1.37 | 76.90±1.25 | 1.63 | 75.09±1.34 | 1.78 |

| Red | 76.11±1.46 | 1.92 | 78.67±1.04 | 1.32 | 76.68±1.10 | 1.43 | 75.04±1.34 | 1.79 | |

| White | 76.43±1.34 | 1.75 | 79.38±1.04 | 1.31 | 79.12±0.72 | 0.91 | 76.67±0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Wet Gluten (wt%) | All | 27.79±4.28 | 15.40 | 20.97±3.81 | 18.17 | 23.16±3.55 | 15.33 | 21.77±5.67 | 26.05 |

| Red | 28.12±4.59 | 16.32 | 21.44±3.64 | 16.98 | 23.67±3.36 | 14.20 | 21.83±5.74 | 26.29 | |

| White | 27.08±3.39 | 12.52 | 19.05±3.88 | 20.37 | 18.00±1.67 | 9.28 | 19.78±0.22 | 1.11 | |

| ZelenySedimentation volume (ml) | All | 38.60±12.74 | 33.01 | 24.63±5.08 | 20.63 | 32.39±6.62 | 20.44 | 40.74±8.51 | 20.89 |

| Red | 41.00±11.85 | 28.90 | 25.59±4.63 | 18.09 | 33.60±5.90 | 17.56 | 41.00±8.48 | 20.68 | |

| White | 33.39±13.04 | 39.05 | 20.69±4.91 | 23.73 | 22.75±2.75 | 12.09 | 31.50±0.50 | 1.59 | |

|

Hectoliter Weight (kg/hL) |

All | 80.41±2.14 | 2.66 | 80.28±1.72 | 2.14 | 79.32±1.53 | 1.92 | 78.66±1.57 | 1.99 |

| Red | 80.11±1.72 | 2.15 | 79.94±1.54 | 1.92 | 79.47±1.47 | 1.85 | 78.58±1.50 | 1.91 | |

| White | 81.06±2.73 | 3.37 | 81.70±1.70 | 2.08 | 77.25±0.05 | 0.06 | 81.73±0.05 | 0.06 | |

|

Kernel Density (102·mg/mm3 or kg/hL) |

All | 129.64±4.33 | 3.34 | 129.42±4.40 | 3.40 | 130.99±4.12 | 3.15 | 130.79±3.96 | 3.02 |

| Red | 130.42±4.44 | 3.40 | 129.83±4.54 | 3.50 | 130.96±4.13 | 3.16 | 130.56±3.77 | 2.89 | |

| White | 127.94±3.53 | 2.76 | 127.73±3.23 | 2.53 | 131.44±4.73 | 3.60 | 138.77±0.01 | 0.01 | |

|

Kernel Volume (mm3) |

All | 35.17±3.42 | 9.73 | 34.72±3.44 | 9.92 | 32.13±2.27 | 7.07 | 32.54±3.12 | 9.42 |

| Red | 35.01±3.36 | 9.60 | 35.30±3.49 | 9.89 | 32.23±2.23 | 6.91 | 32.64±3.10 | 9.32 | |

| White | 35.51±3.53 | 9.93 | 32.34±1.87 | 5.77 | 30.80±2.38 | 7.73 | 28.80±3.10 | 10.76 | |

|

Kernel Weight (mg) |

All | 45.53±4.05 | 8.89 | 44.96±5.01 | 11.15 | 42.02±2.74 | 6.52 | 42.48±3.37 | 7.94 |

| Red | 45.59±3.98 | 8.73 | 45.86±5.11 | 11.14 | 42.18±2.73 | 6.47 | 42.55±3.39 | 7.97 | |

| White | 45.39±4.19 | 9.23 | 43.94±2.05 | 4.66 | 40.02±2.02 | 5.05 | 39.97±4.63 | 11.59 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).