1. Introduction

Labor is a natural process involving the gradual onset of painful uterine contractions that increase in frequency and intensity until childbirth [

1]. Severe labor pain is attributed as a primary reason for women requesting cesarean sections [

2]. Therefore, effective labor pain management is essential [

3]. Epidural analgesia is the standard method for alleviating labor pain; however, it requires anesthesiologists and teams to ensure patient safety [

3]. Given the need for specialized expertise in administering epidural analgesia, many healthcare providers have resorted to alternative pain-relief methods. Parenteral opioids such as pethidine, fentanyl, remifentanil, butorphanol, and nalbuphine are commonly used in these cases [

4].

Pethidine is a traditional opioid used to treat labor pain; however, its active metabolite can depress neonatal respiration, which limits its use [

5]. Advances in the management of severe acute pain recommend the use of potent action and rapid-onset opioids, such as remifentanil and fentanyl. These opioids have a shorter duration of action and do not produce active metabolites that can lead to adverse effects [

6]. Consequently, they have been widely used in labor pain management and have demonstrated satisfactory results without causing serious side effects [

7]. Although remifentanil is recommended for intravenous patient-controlled analgesia [

8], its routine use is limited to middle-income countries.

Fentanyl is a 4-anilidopiperidine synthetic opioid that binds to mu (µ)-opioid receptors, inhibiting nerve activityand reducing pain perception [

9]. Its onset of action occurs immediately after intravenous injection and the duration of action is 30–60 min [

4]. It is used in various medical fields and is available worldwide [

10]. Research supports the effectiveness of fentanyl in relieving labor pain, with evidence covering different doses, regimens, and routes of administration [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Intermediate intravenous dosing is commonly used to mitigate concerns about the cumulative dose effect, with 25–100 micrograms (µg) repeated every 5 min to 2 hr [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, neonatal adverse effects, including abnormal intrapartum fetal monitoring, low Apgar scores, need for neonatal resuscitation, and administration of naloxone following a bolus dose of at least 50 µg of fentanyl, have been reported [

11,

12,

14].

Hence, concerns exist regarding the initiated lowest effective dosage for opioid-naïve pregnancy and its potential neonatal adverse effects; moreover, a systematic review unable to determine the most appropriate dosage regimen or opioid type with the least side effects [

7,

18]. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of two low-dose fentanyl regimens (25 µg and 50 µg) for relieving pain during the active phase of labor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This double-blind, parallel-group, randomized, controlled trial was conducted at a tertiary hospital. Participants were recruited between June 16, 2023, and August 3, 2024. Research assistant nurses in the labor ward obtained written informed consent from all eligible participants during the latent phase of labor.

This study was approved by the Institute Review Board of Human Research on March 30, 2023 (approval number: KEF66006) and was registered in the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) on May 30, 2023 ( identification number 20230530005). This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. The study was conducted following the CONSORT 2010 guidelines for clinical trials [

19].

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

This study included pregnant women aged 18 years or older, who were admitted for a planned vaginal delivery and requested analgesia for pain relief during the active phase of labor. The inclusion criteria were singleton pregnancy, cephalic presentation, gestational age between 37+0 and 42+0 weeks, normal intrapartum cardiotocography upon admission, cervical dilation between 5 and 8 cm [

11,

20], and a visual analog scale (VAS) score of 4 or higher [

21,

22].

The exclusion criteria included having received opioids within the previous 24 hr; a respiratory rate (RR) of 10 or fewer breaths per minute; bradycardia (heart rate less than 60 bpm); oxygen saturation from pulse oximetry below 95%; a diagnosis of severe bronchial asthma, glaucoma, heart or liver disease; allergies or previous adverse reactions to opioids; opioid dependence within the past year; use of antidepressants within the last 14 days; cognitive impairments; or intellectual disabilities.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

The randomization process involved a computer-generated sequence—created by a statistician—based on the block randomization method, with randomly selected block sizes of two, four, and six in a 1:1 ratio. Treatment allocations were concealed in sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes. Randomization was performed by the attending nurse when the participants requested analgesia and had at least a moderate pain score [

23] based on a VAS of at least 4 [

22]. All participants, attending nurses, obstetricians involved in their care, outcome collectors, statisticians, and investigators were blinded to treatment allocations. The drug preparations for both groups were identical and were prepared by pharmacists who were not involved in the study.

3. Procedures

Participants who requested analgesia were assessed using the VAS for pain immediately after their uterine contractions subsided. Subsequently, obstetricians or nurses examined cervical dilation to confirm the participants’ stage of labor. The enrolled participants were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups. VAS pain scores, Pasero sedative scores (SS) [

24], RR, blood pressure (BP), pulse rate (PR), and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded at baseline (immediately before the intervention) and at 30, 60, and 120 min after the injection. Metoclopramide (10 mg) was administered intravenously when nausea or vomiting occurred. Additional doses according to the treatment regimens (25 µg vs 50 µg) were administrated intravenously every hour upon the participant’s request. For participants who continued to experience moderate to severe pain (VAS ≥ 4) 30 min after receiving the initial regimen, a rescue dose of intravenous 25 µg fentanyl was offered, with a maximum total dose of 500 µg per course of treatment [

16]. In addition to the fentanyl protocol, all participants received the same standard management during the active phase of labor.

Accordingly, fentanyl was not a routine treatment for relieving labor pain, and there were concerns regarding the new treatment protocol in the local context. Continuous intrapartum cardiotocography was performed electronically for 20 min after fentanyl injection. Abnormal fetal monitoring included minimal variability, repetitive late and variable decelerations, acute bradycardia, and prolonged decelerations. Conservative management was opted in these cases, including interventions such as the left lateral decubitus position, intravenous infusion of isotonic saline solution, and oxygen therapy until a normal trace was observed.

3.1. Intervention Group

The intervention group received a total volume of 2 ml containing 25 µg of fentanyl. This was prepared by mixing 1 ml of 50 µg fentanyl with 3 ml of normal saline, resulting in a total volume of 4 ml with 50 µg of fentanyl. Two milliliters of this mixture was administered intravenously for 1–2 min [

13,

16].

3.2. Control Group

The control group received a total volume of 2 ml containing 50 µg of fentanyl. This was prepared by mixing 1 ml of 50 µg fentanyl with 1 ml of normal saline, resulting in a total volume of 2 ml with 50 µg of fentanyl. The mixture was administered intravenously for 1–2 min [

11,

12,

14,

17].

4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in mean pain score reduction 30 min after fentanyl treatment of the 25 µg and 50 µg regimens. The participants’ self-reported pain scores at the peak of uterine contractions were measured using VAS. The pain scores were recorded immediately before starting the protocol and 30 min after fentanyl administration. Four sets of observations were documented at baseline and at 30, 60, and 120 min after the intervention, if the participant received only one dose. For participants who received multiple doses, observations were recorded before and 30 min after each fentanyl injection.

Secondary outcomes were categorized into maternal and neonatal safety outcomes. Maternal outcomes included total and additional doses of fentanyl, mode of birth, duration of labor, breastfeeding initiation, satisfaction with the study treatment, and adverse effects of fentanyl, such as changes in SS, RR, BP, PR, and SpO2. Neonatal outcomes included intrapartum fetal monitoring, Apgar score ≤7 at 5 min, need for resuscitation, administration of naloxone, and admission to the nursery or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Baseline characteristics, including age, body mass index, parity, cervical dilation at the initiation of treatment, and outcomes, were obtained from electronic medical records. Two hours after delivery, participants were assessed using a questionnaire on their experience of breastfeeding initiation and satisfaction with the study treatment.

4.1. Sample Size

The sample size calculation was based on a primary outcome to assess the effectiveness of a 25 µg of fentanyl dose compared to the standard 50 µg dose in relieving labor pain 30 min after treatment. The minimum threshold for labor pain relief was set at a 0.9 cm reduction on VAS [

15,

25]. A pilot study was conducted to estimate the pooled variance, as well as the mean pain score and standard deviation (mean ± SD) for 30 min after treatment of 25 µg and 50 µg fentanyl doses, which were 7.29 ± 2.04 and 7.01 ± 1.83, respectively. Based on these estimates, with an alpha error of 0.05 and a beta error of 0.2, the total sample size comprised 122 participants, accounting for a 5% dropout rate.

4.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. The primary outcome was compared between the two fentanyl regimens using the Mann–Whitney U test. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) population-averaged model was used to estimate the effect size, which was defined as the mean difference in pain score reduction with a 95% CI across different time points. The Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons at these time points. Because the participants gave birth before the scheduled observation times, missing pain score data were assumed to be missing at random. These were handled using all available individual data, accounting for correlations in the GEE-repeated measurements. Continuous data was tested for normal distribution, presented as mean ± SD, and compared using an independent t-test. Data with a non-normal distribution were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 18.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

4.3. Patient and Public Involvement

The participants were not involved in the design, outcome measurements, or interpretation of the results. The study findings will be shared with participants and the public through scientific articles.

5. Results

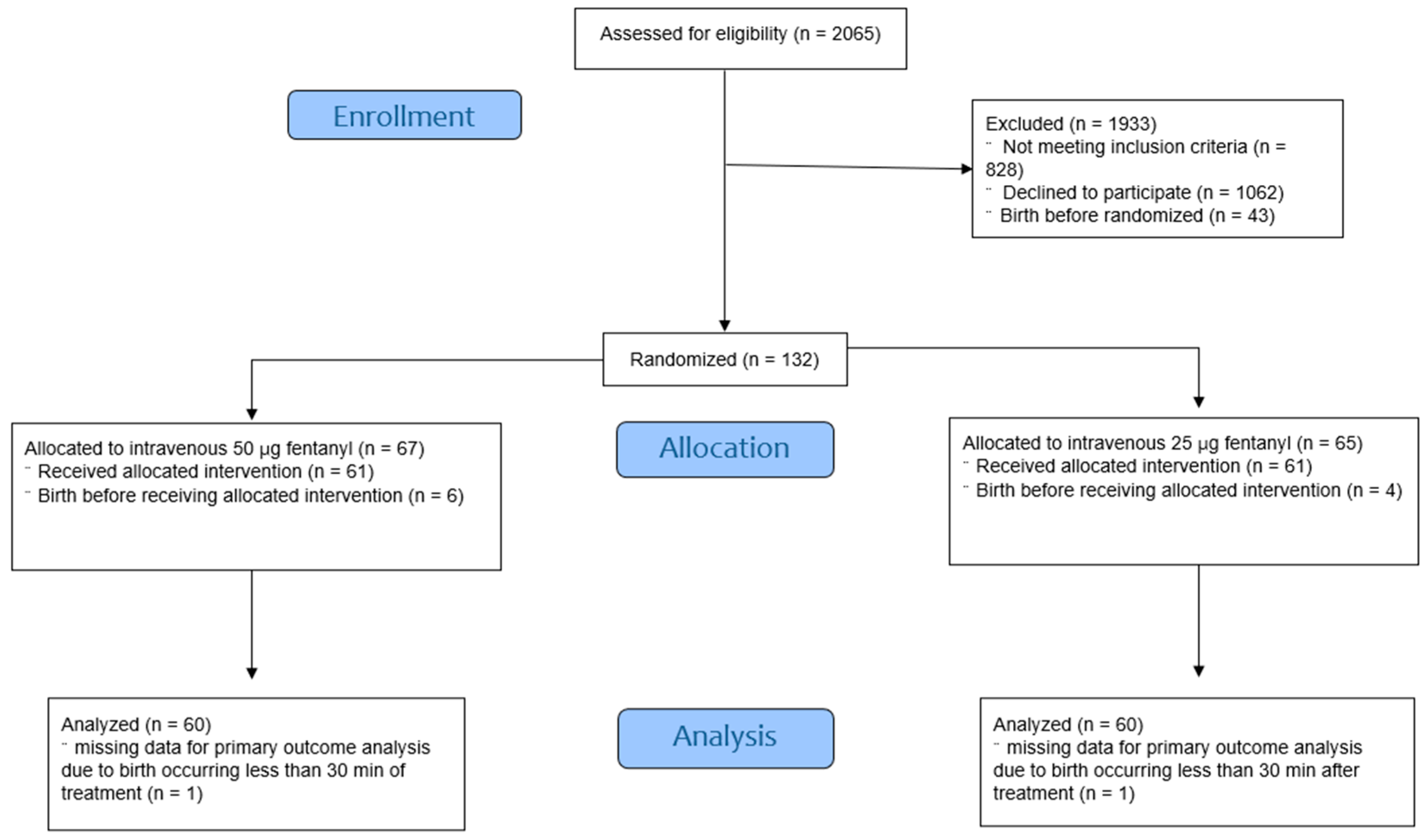

A total of 2065 women with singleton, cephalic, live, and term fetuses who were planning to undergo vaginal delivery were eligible for enrolment. The CONSORT flow diagram depicts the study flow (

Figure 1). Of these, 122 were randomized into two treatment groups. One participant in each group gave birth less than 30 min after receiving the fentanyl injection. Baseline characteristics showed no statistically significant differences between the groups (

Table 1). Approximately 80% of the participants in both groups requested pain relief when the cervical dilation reached 5–6 cm. The median baseline VAS scores were 8.9 (7.5, 10) and 9.2 (8, 10) for the 25 µg and 50 µg fentanyl groups, respectively.

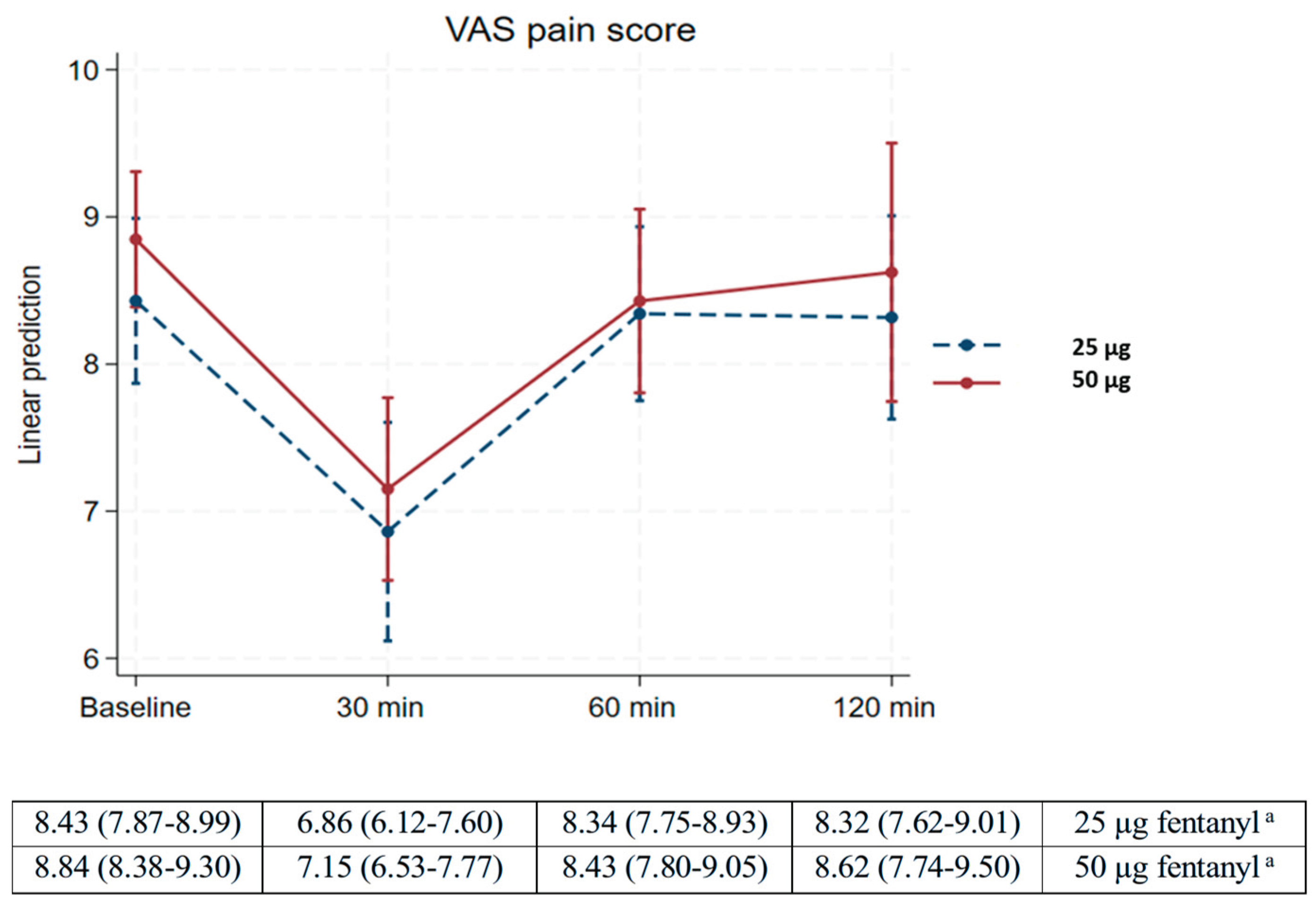

Table 2 demonstrates that pain scores significantly decreased from baseline to 30 min after fentanyl treatment, with mean changes of -1.57 (95% CI -2.1 to -1.1) and -1.69 (95% -2.2 to -1.2) in the 25 µg and 50 µg fentanyl groups, respectively. Additionally, the mean change in pain scores for both groups exceeded the minimum threshold for labor pain relief of 0.9 cm. The mean pain scores in both groups increased from 30 min to 60 min after treatment, with mean changes of 1.5 (95% CI 0.8 to 2.1) in the 25-µg fentanyl group and 1.3 (95% CI 0.5 to 2.0) in the 50-µg fentanyl group. Multiple comparisons of mean differences at baseline, 60 min, and 120 min within each fentanyl group (25 µg and 50 µg) showed no statistically significant differences (

P > 0.999). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in pain reduction between the two fentanyl groups at any time point (

P > 0.999) (

Table 2).

Pain grade scales between fentanyl 25 µg and 50 µg regimens also demonstrated no statistically significant differences (

P = 0.201) (

Table 3). The linear prediction graph of the VAS pain score at the four time points for both groups is presented in

Figure 2.

Table 4 shows that the total dose of fentanyl used in the 25-µg group was significantly lower than that in the 50-µg group (mean ± SD; 32.8 ± 13.3 vs 60.2 ± 22.1,

P < 0.001). No significant differences were noted in the need for additional doses between the two groups (23.7 vs 19.7%,

P = 0.201).

Pregnancy and neonatal adverse outcomes showed no statistically significant differences between the 25 µg and 50 µg intravenous fentanyl groups (

Table 5). Five participants (8.2%) in the 25-µg fentanyl group and 7 participants (11.5%) in the 50-µg fentanyl group experienced a change in Pasero SS from “awake” to “occasionally drowsy” (

P > 0.999). However, none of the participants demonstrated desaturation (SpO

2 ≤ 94%) [

26], hypotension, or syncope. Twenty participants (32.8%) in the 25-µg fentanyl group and 23 participants (37.7%) in the 50-µg fentanyl group demonstrated abnormal intrapartum fetal monitoring (

P=0.214).

None of the neonates experienced birth asphyxia or required naloxone treatment, resuscitation or admission to the NICU. However, tachypnea was the cause of neonatal nursery admission. Approximately 10% of the postpartum women in each group reported difficulty in initiating breastfeeding. Eighty percent of participants in the 25-µg fentanyl group and almost 80% in the 50-µg fentanyl group were satisfied with their pain relief treatment (

Table 5).

6. Discussion

This study aimed to identify appropriate non-axial opioid analgesia for relieving labor pain during the active phase based on the new definition of this phase [

20,

27], focusing on its implementation in low-resource settings. Short-acting opioids such as fentanyl, which have minimal adverse effects on the mother and fetus, are the drugs of choice. In addition, the CDC Clinical Practice Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids recommend prescribing the lowest effective dose of opioids to minimize adverse effects [

18]. Although the effective dose of fentanyl can be determined through guidelines, some studies have shown that a 25-µg dose of fentanyl is also effective [

13,

16].

A key strength of this study is that it is the first trial to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of 25-µg fentanyl with the standard 50-µg dose during the active phase of labor, based on the new definition [

20,

27]. This study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice for a double-blind randomized controlled trial.

This study found that the intravenous 25-µg fentanyl dose and the 50-µg dose were effective in relieving labor pain during the active phase. Both regimens reduced pain scores 30 min after fentanyl administration, 1.57 cm and 1.69 cm for intravenous 25-µg fentanyl dose and the 50-µg dose, respectively, which is consistent with findings of other studies around 0.9- 1.6 cm [

11,

14]. However, in the present study, the pain-reducing effects of either fentanyl dose did not persist throughout the observation period. This finding differs from those of other studies [

11,

12,

13,

14], which may be attributed to the timing of treatment in this study, which began when cervical dilation reached at least 5 cm, whereas other studies initiated treatment at 3–4 cm. One strategy for effective pain relief is to administer analgesics at the earliest onset of pain [

28]. Furthermore, the loss of pain relief 60 min after fentanyl treatment was attributed to the duration of the effect of fentanyl, which is typically 30–60 min.

This study revealed that although both fentanyl regimens were safe for the participants, the total dose of intravenous 25-µg fentanyl was significantly lower than that in the 50-µg regimen. No serious neonatal adverse events occurred; however, approximately one-third of the neonates in both groups demonstrated abnormal intrapartum cardiotocography traces, and approximately 10% required nursery admission. Approximately 80% of the participants in both groups were satisfied with pain relief, while approximately 10% encountered difficulty initiating breastfeeding.

Maternal and neonatal safety outcomes in this study were similar to those reported in other studies [

11,

13,

14,

15,

17]. Owing to local concerns regarding the new protocol for labor pain relief using fentanyl, continuous intrapartum cardiotocography monitoring was performed for 20 min in all the participants. Abnormal fetal monitoring was identified in approximately 35% of participants in each group, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [

13,

17]. However, four participants in each group did not respond to conservative management for more than 40 min, leading to expedited cesarean deliveries. Only one neonate required nursery admission. Some studies have considered these abnormal events to be idiosyncratic and found that fentanyl doses below 100 µg did not affect fetal cardiovascular or acid-base balance [

29].

The duration of the active phase of labor in this study was shorter than that observed during spontaneous labor [

30]. This finding is similar to the duration reported by Shoorab et al., where fentanyl was suggested to have shortened the active phase of labor [

13]. However, Atkinson et al. reported that the uterine contraction pattern remained unchanged 1 hr after fentanyl injection [

31]. Østborg et al. found that the mean duration of the active phase of spontaneous labor, starting at 4 cm of cervical dilation, was 368 min for nulliparous women and 165 min for multiparous women [

30]. In comparison, the median durations in this study were 185 min and 121 min in nulliparous and multiparous women, respectively. One possible explanation for this difference is that as Zhang et al. revealed that the progression of labor from 4–6 cm was longer than previously defined [

32].

Although the pain score reduction was approximately 1–2 cm, approximately 80% of the participants were satisfied with the fentanyl regimen for pain relief, which is consistent with the findings of two experimental studies [

14,

15]. This satisfaction may be explained by participants experiencing relief from labor pain without adverse effects from fentanyl treatment, coupled with deep emotional involvement after giving birth [

33].

Approximately 10% of the postpartum women in each group encountered difficulty establishing breastfeeding, which is consistent with previous studies [

15,

16]. Oommen et al. reported that fentanyl has a negative effect on the spontaneous suckling of newborn babies (odds ratio, OR 2.18; 95%CI 1.44–3.29) [

16]. However, this study found a lower rate of early breastfeeding issues (10 vs. 32%), likely because the total fentanyl dose was less than half of that used in the study by Oommen et al. These findings support the idea that the fentanyl dose may influence early breastfeeding difficulties [

16].

Statistical power was used to estimate the sample size for the study, specifically to assess the primary objective of comparing pain score reductions 30 min after treatment with intravenous 25-µg and 50-µg fentanyl doses. Unfortunately, approximately 25% and 50% of data were missing at the 60- and 120-min time points, respectively. The missing data were due to the trial being conducted during the active phase of labor, including nulliparous and multiparous women who delivered before the scheduled observation times. Consequently, the small sample size became a limitation, reducing the ability to assess repeated measurement outcomes. Additionally, the study did not include a sensitivity or subgroup analysis of factors that could contribute to variations in labor pain, such as parity. Furthermore, no long-term follow-up data was available.

7. Conclusions

To summarize, the effectiveness of pain relief during the active phase of labor after 30 min of treatment with 25-µg intravenous fentanyl was comparable to that of 50-µg intravenous fentanyl. Both regimens were safe for maternal use and resulted in high patient satisfaction. Although serious neonatal adverse events did not occur, concerns remain regarding abnormal intrapartum fetal monitoring and difficulty in establishing breastfeeding. These findings can help inform pregnant individuals and their companions, and guide healthcare providers in delivering appropriate intrapartum care. Appraising the comparable effectiveness in relieving labor pain and the satisfaction with both 25 µg and 50 µg doses, along with the benefit of using a lower amount of the drug, this study suggests using 25-µg intravenous fentanyl can be an alternative regimen for labor pain relief. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal time interval for fentanyl administration to ensure effectiveness, safety, and strategies to minimize fentanyl-related breastfeeding issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and S.S.; Methodology, V.S., P.J. and S.S.; Validation, V.S. and S.S.; Formal analysis, P.I. and S.S.; Investigation, V.S. and S.S.; Data curation, V.S. and S.S.; Writing -Original draft, V.S.; Writing - Review and Editing, P.J. and S.S.; Visualization, V.S., P.J. and S.S.; Supervision, V.S. and S.S.; Project Administration, V.S.; Funding acquisition, V.S.

Funding

This study received funding from the “POL. Gen. Dr. Jongiate Aojanepong Fund” of the Royal Thai College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RTCOG; grant identifier 012-RTCOG2304). Financial support allowed for the procurement of necessary research materials and facilitated data collection and analysis. The opinions of the authors expressed in this article are not always agreed upon by the Royal Thai College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Khon Kaen Hospital Institute Review Board in Human Research (Project identification code KEF66006) on 30 March 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants, nurses, residents, and staff at Khon Kaen Hospital for facilitating the study. We would like to extend special thanks to Dr. Phuping Akavipat, Dr. Ussanee Sangkomkamhang, and Prof. Kitti Jiraratanapochai for their contributions to the peer reviewers who refined the research content, and Piyanan Suparattanagool for serving as a consultant during the analysis process. We also thank the Royal Thai College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RTCOG) for funding this study.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Labor, S.; Maguire, S. The pain of labour. Rev Pain 2008, 2, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Show, K.L.; Ngamjarus, C.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Rattanakanokchai, S.; Duangkum, C.; Bohren, M.A.; et al. Fentanyl for labour pain management: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Othman, M.; Dowswell, T.; Alfirevic, Z.; Gates, S.; Newburn, M.; et al. Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, 2012, CD009234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D. A review of systemic opioids commonly used for labor pain relief. J Midwifery Womens Health 2011, 56, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morselli, P.L.; Rovei, V. Placental transfer of pethidine and norpethidine and their pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1980, 18, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douma, M.R.; Verwey, R.A.; Kam-Endtz, C.E.; van der Linden, P.D.; Stienstra, R. Obstetric analgesia: a comparison of patient-controlled meperidine, remifentanil, and fentanyl in labour. Br J Anaesth 2010, 104, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.A.; Burns, E.; Cuthbert, A. Parenteral opioids for maternal pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 6, CD007396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrapartum care. Clinical Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London 2023 [Internet]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596341/.

- Al-Hasani, R.; Bruchas, M.R. Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor-dependent signaling and behavior. Anesthesiology 2011, 115, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, J.; Fraser, G.L.; Coursin, D.B.; Riker, R.R.; Fontaine, D.; Wittbrodt, E.T.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med 2002, 30, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raksakulkiat, S.; Punpuckdeekoon, P. A Comparison of meperidine and fentanyl for labor pain reduction in Phramongkutklao hospital. J Med Assoc Thai 2019, 102, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk, M.; El-Shamy, E.S.; Massod, A.; Dawood, R.; Habeeb, R. The safety and acceptability of intravenous fentanyl versus intramuscular pethidine for pain relief during labour. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2015, 42, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoorab, N.J.; Zagami, S.E.; Mirzakhani, K.; Mazlom, S.R. The effect of intravenous fentanyl on pain and duration of the active phase of first stage labor. Oman Med J 2013, 28, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duangkum, C.; Sirikarn, P.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Sothornwit, J.; Chaiyarah, S.; Saksiriwuttho, P.; et al. Subcutaneous vs intravenous fentanyl for labor pain management: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2024, 6, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleet, J.; Belan, I.; Jones, M.J.; Ullah, S.; Cyna, A.M. A comparison of fentanyl with pethidine for pain relief during childbirth: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2015, 122, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oommen, H.; Oddbjørn Tveit, T.; Eskedal, L.T.; Myr, R.; Swanson, D.M.; Vistad, I. The association between intrapartum opioid fentanyl and early breastfeeding: a prospective observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021, 100, 2294–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn, W.; Rathke, A.; Leuschen, M.P.; Chleborad, J.; Weidner, W. Fentanyl citrate analgesia during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989, 161, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, D.; Ragan, K.R.; Jones, C.M.; Baldwin, G.T.; Chou, R. CDC Clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain – United States [Internet]. MMWR Recomm Rep 2022, 71, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010, 1, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labour care guide: user’s manual from the World Health Organization 2020 [Internet]. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017566.

- Robinson, C.L.; Phung, A.; Dominguez, M.; Remotti, E.; Ricciardelli, R.; Momah, D.U.; et al. Pain scales: what are they and what do they mean. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2024, 28, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Moore, R.A.; McQuay, H.J. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 1997, 72, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, D.; Ragan, K.R.; Jones, C.M.; Baldwin, G.T.; Chou, R. Prescribing opioids for pain — The new CDC clinical practice guideline. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 2011–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, N.; Quinlan, J.; El-Boghdadly, K.; Fawcett, W.J.; Agarwal, V.; Bastable, R.B.; et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on the prevention of opioid-related harm in adult surgical patients. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.M. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med. 1998, 5, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Driscoll, B.R.; Howard, L.S.; Earis, J.; Mak, V.; Bajwah, S.; Beasley, R.; et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. BMJ Open Respir Res 2017, 4, e000170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. First and second stage labor management: ACOG clinical practice guidelines no. 8. 2024, 143, 144–162.

- Borsook, D.; Youssef, A.M.; Simons, L.; Elman, I.; Eccleston, C. When pain gets stuck: the evolution of pain chronification and treatment resistance. Pain 2018, 159, 2421–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J.B.; Coaldrake, L.A.; Bolan, J.C.; Mondino, M.; Mazel, P.; Gilman, R.M.; et al. Placental passage and uterine effects of fentanyl. Anesth Analg 1983, 62, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østborg, T.B.; Romundstad, P.R.; Eggebø, TM. Duration of the active phase of labor in spontaneous and induced labors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017, 96, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, B.D.; Truitt, L.J.; Rayburn, W.F.; Turnbull, G.L.; Christensen, H.D.; Wlodaver, A. Double-blind comparison of intravenous butorphanol (stadol) and fentanyl (sublimaze) for analgesia during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994, 171, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Troendle, J.F.; Yancey, M.K. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002, 187, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L.; Banse, R. Psychological aspects of childbirth: evidence for a birth-related mindset. European J Social Psychology 2021, 51, 124–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).