1. Introduction

Spinal anesthesia is considered the method of choice for elective cesarean sections around the world [

1], being an easy-to-perform, quickly acting type of anesthesia that provides greater maternal and fetal safety than general anesthesia. Compared to general anesthesia with airway manipulation and the risk of failed intubation and aspiration complications, spinal anesthesia avoids these complications, and also reduces maternal and fetal exposure to intravenous anesthetic agents. Moreover, spinal anesthesia enables the mother to stay awake during childbirth, allowing an instant bonding experience with the newborn. These advantages have solidified its role as the gold standard for cesarean delivery [

2].

Spinal anesthesia offers a multitude of benefits, but it also introduces various potential complications. Among the numerous potential adverse effects, maternal hypotension emerges as the most critical and recurrent issue because it occurs in approximately 70–80% of cases [

3]. The manifestation of maternal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting together with dizziness results from severe hypotension, which reaches its most extreme form by causing loss of consciousness. An urgent medical issue arises when uteroplacental blood flow reduction occurs, which subsequently causes fetal acidosis along with neonatal distress [

4]. However, there is no universally accepted definition of hypotension in the scientific literature. Some studies define it as a systolic blood pressure decrease of more than 20% from baseline, while others use an absolute threshold of less than 90 mmHg [

4,

5]. Regardless of the definition used, post-spinal hypotension remains a significant clinical challenge, necessitating effective preventive and management strategies [

6].

A multitude of techniques have been investigated to address and reduce the potential occurrence of post-spinal hypotension. The medical practice of administering crystalloids or colloids before surgery has been widely used, yet questions about its effectiveness persist. The medical community commonly employs vasopressors like phenylephrine and ephedrine to treat hypotension, while norepinephrine emerges as a potential alternative because it delivers combined α- and β-adrenergic effects. The strategic placement of patients into specific positions emerges as another crucial medical intervention where applying the left lateral tilt technique prevents aortocaval compression. The medical practice of decreasing local anesthetic dosage while adding opioid adjuvants has become increasingly popular as a technique to attain sufficient anesthesia levels without causing hemodynamic instability. The process of choosing an appropriate opioid adjuvant emerges as a critical factor in altering hemodynamic responses during spinal anesthesia administration [

7].

Anesthetists frequently integrate opioid adjuvants such as fentanyl (F) and morphine (M) into local anesthetics for spinal anesthesia procedures to attain improved intraoperative anesthesia effects while prolonging postoperative pain relief durations. The deployment of these pharmacological agents empowers healthcare practitioners to administer reduced dosages of local anesthetics, which, in theory, leads to lower sympathetic blockade levels and consequently diminishes the risk of hypotension. F and M exhibit distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that may uniquely impact maternal hemodynamic parameters. The intricate examination and comprehension of these differences constitute essential elements in enhancing the selection process of opioids for spinal anesthesia during cesarean sections [

8].

When administered intrathecally, F displays its characteristics as a highly lipophilic opioid by initiating effects quickly while maintaining a shorter duration of action. Through its action on spinal opioid receptors, it delivers powerful analgesic effects which combine synergistically with local anesthetics like bupivacaine to produce enhanced pain relief. The synergistic effect between these agents permits a reduction in bupivacaine dosage requirements, which subsequently helps mitigate maternal hypotension severity by restricting the extent of sympathetic blockade. The quick elimination of F from the body helps to minimize the chances of extended respiratory depression, which represents a typical issue associated with intrathecal opioids. F's capacity to boost pain relief while simultaneously lowering the risk of low blood pressure makes it a widely chosen option for spinal anesthesia during cesarean deliveries [

8,

9].

M is a hydrophilic opioid that exhibits delayed onset of effects while maintaining an extended duration of action. The extended duration of its analgesic properties renders it an essential tool for managing postoperative pain because it delivers effective pain relief throughout a 24-hour period. The inherent hydrophilic properties of this substance cause it to migrate more readily in a cephalad direction through the cerebrospinal fluid, which consequently heightens the potential for delayed respiratory depression. The interaction of M with µ-opioid receptors located in the brainstem, together with its potential to depress vasomotor centres results in a higher occurrence of hypotension than seen with F. Various research investigations indicate that M's extended binding to central opioid receptors may cause severe hemodynamic instability, which makes its application in spinal anesthesia a topic of continued discussion [

10].

The utilization of F and M as adjuvants in spinal anesthesia for cesarean operations remains common practice, yet their distinct effects on maternal hemodynamic parameters remain inadequately understood. Several research investigations indicate that F reduces local anesthetic needs, which helps prevent hypotension, [

11] while M's central nervous system effects cause increased hemodynamic instability. The precise impact of these opioids on maternal blood pressure and cardiovascular function remains undefined, representing a significant gap in existing research.

The frequent occurrence of maternal hypotension combined with its potential adverse effects on both mother and fetus necessitates a direct comparative study of intrathecal F versus M during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. A thorough examination of how these agents affect maternal blood pressure alongside vasopressor needs and hemodynamic stability will yield essential insights to refine anesthetic techniques. This research investigation seeks to elucidate how different opioids affect hemodynamic parameters during spinal anesthesia to enhance anesthetic protocols for cesarean sections, thereby boosting maternal safety while ensuring better neonatal health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The retrospective study was conducted on pregnant women admitted for delivery at Pelican Clinic, Medicover Hospital, Romania, between January 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024.

It received approval from the Pelican Clinic Ethics Committee of Medicover Hospital (Approval No. 2421/10.12.2019) and adhered to the ethical principles of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (1967). Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of their admission to the hospital.

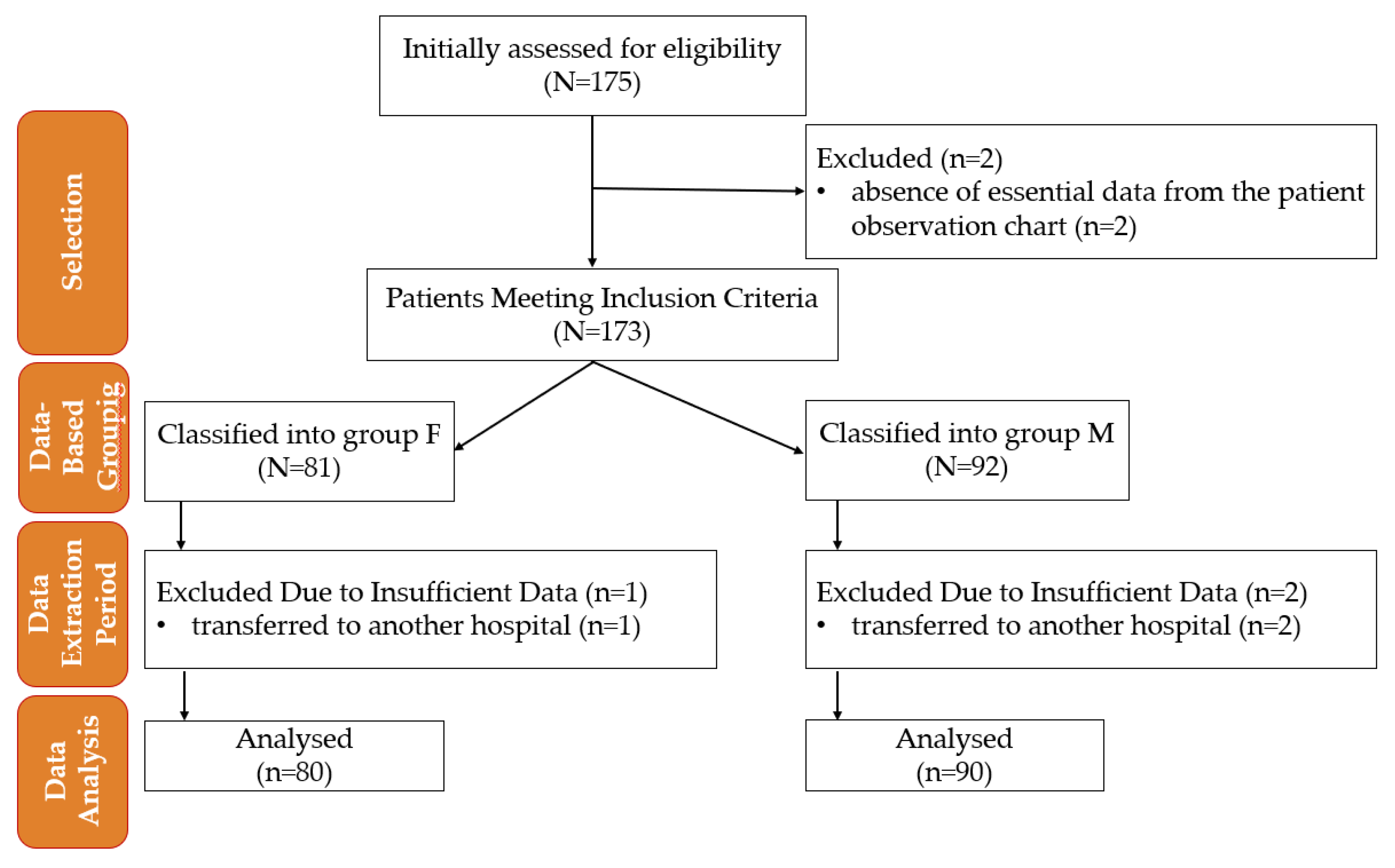

Pre-established eligibility criteria determined the subjects' inclusion in the study. Clinical data analysis was conducted based on the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria without active allocation interventions,

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion and data analysis in the study. M—morphine; F—fentanyl; n—number.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion and data analysis in the study. M—morphine; F—fentanyl; n—number.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I–II (healthy patients or those with mild systemic disease without functional limitations)

Age between 18 and 50 years

No significant medical history, including cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, endocrine, or hematological disorders

No known drug or food allergies

No chronic medication use, including antihypertensive drugs or treatment for any condition, particularly preeclampsia

No history of chronic pain or regular use of analgesics (opioids or non-opioids)

No contraindications to spinal anesthesia, such as coagulopathy, local infection, or anatomical abnormalities

Body weight over 50 kg

Singleton, viable fetus confirmed via ultrasound

Gestational age of at least 37 weeks at the time of elective cesarean section

Indication for elective cesarean section, excluding emergency procedures or cases with maternal or fetal distress.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Acute or chronic fetal distress, diagnosed pre- or postnatally

Fetal malformations, detected intrauterine or postpartum

Development of preeclampsia during pregnancy or peripartum

Need for surgical reintervention within 72 hours postpartum, regardless of the cause

Requirement for opioid administration or other intravenous anesthetics during the procedure

Spinal anaesthesia failure, necessitating conversion to general anesthesia

Absence of essential data in the patient observation chart

Blood loss more than 500 mL

Sensory block maximum at T4 level

Transferred to another hospital.

2.4. Anesthetic Protocol and Monitoring

Preoperatively, all patients included in the study were monitored using the Dräger Infinity Delta system (2001, Lübeck, Germany), which allowed for non-invasive recording of vital parameters. blood pressure (BP), ventricular rate (VR), and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO₂) were continuously measured to ensure patient safety. Each patient received an 18-gauge intravenous cannula and was administered 500 mL of Ringer's lactate solution before the spinal anesthesia. Premedication consisted of 40 mg pantoprazole and 10 mg metoclopramide, both administered intravenously.

Spinal anesthesia was performed under strict aseptic conditions with the patient in a sitting position. The procedure was conducted at the L3-L4 intervertebral space using a 27-gauge pencil-point spinal needle with an introducer. After local anesthetic infiltration with 2 mL of 1% lidocaine, the intrathecal space was identified, and a single-shot anesthetic mixture was administered.

All patients received hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% (5 mg/mL) in doses ranging from 7.5 mg (1.5 mL) to 11 mg (2.2 mL), adjusted according to the patient’s height, administered intrathecally, combined with either intrathecal M at a dose of 0.1 mL (100 µg, solution of 1 mg/mL) or intrathecal F at a dose of 0.25 mL (25 µg, solution of 50 µg/mL).

Following the spinal injection, the patient was immediately placed in the supine position with a right hip wedge to prevent inferior vena cava compression. Non-invasive BP monitoring was performed. Additional monitored parameters included VR and SpO₂. The motor and sensory block levels were assessed, with the motor block evaluated using the Bromage scale, where 4 indicated maximum efficacy and the sensory block was considered maximum at the T4 level.

Oxygen was administered at a flow rate of 3-4 L/min when oxygen saturation dropped below 95%. Hypotension was managed with ephedrine, prepared in a dilution of 5 mg/mL. If an initial drop in BP was detected, an ephedrine dose of 5-15 mg was administered, depending on the severity of hypotension. Ephedrine administration was repeated to restore optimal systolic blood pressure (BPS). Bradycardia, defined as a heart rate below 55 beats per minute (bpm) within the first 5 minutes, was treated with an intravenous dose of 0.5 mg atropine.

Ringer’s lactate (10-20 mL/kg/h) was administered to maintain adequate intravascular volume. After fetal extraction, 4 mg dexamethasone and 4 mg ondansetron were administered to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting.

2.5. Data Collection

The collected data included demographic and lifestyle characteristics such as age, place of residence, and smoking status. Clinical and anthropometric parameters were recorded, including weight, height, body mass index (BMI), number of pregnancies and births, history of cesarean delivery, presence of contractions at the time of anesthesia, and previous analgesia.

Hemodynamic parameters were monitored before (1), and after anesthesia (2), including BPS, diastolic blood pressure (BPD), mean arterial pressure (MAP), VR, and SpO₂.

Blood pressure was measured before (1) and every minute after spinal anesthesia until 3 minutes after fetal extraction, with the lowest recorded value being considered for the study (2).

VR was measured before (1) and after the intervention during the first 5 minutes, considering the lowest recorded values (2).

SpO₂ was measured before anesthesia (1) and 5 minutes after its administration (2).

Nausea and vomiting were recorded until fetal extraction.

This study is part of a larger research project analysing maternal and neonatal physiological parameters. A complementary study focusing on neonatal outcomes is being published separately.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 29.0.2.0 (20)). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects in the two study groups were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Depending on the data distribution, parametric and non-parametric tests were applied for group comparisons.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of distribution for continuous variables. Subsequently, the comparison tests were adapted to each dataset. For variables with a normal distribution, the independent t-test was applied, while for those with a non-normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Differences between values measured before and after the intervention were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test.

The Chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of categorical data, and Fisher's exact test was applied when cell frequencies were low.

All statistical tests were conducted using a significance threshold of p < 0.05, and the Levene test was employed to assess the homogeneity of variances.

3. Results

The study included 175 patients. Five cases were excluded. The rest were divided into two groups based on the type of anesthesia: 80 patients received F anesthesia (Group F), and 90 patients received M anesthesia (Group M). The baseline characteristics of the two groups are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study groups.

| Parameter |

Group F (n=80) |

Group M (n=90) |

P-value |

| DD |

|

|

|

| Age, years, M ± SD (min, max) |

31.61±4.37 (23.50) |

32.17±4.38 (22.44) |

0.434* |

| Urban residence, n (%) |

55 (68.8) |

62 (68.9) |

0.984** |

| Smoker, n (%) |

13 (14.44) |

15 18.75) |

0.450** |

| Clinical and laboratory data |

|

|

|

| Weight, kg, M ± SD (min, max) |

77±12.83 (50, 110) |

77,84±15.05 (53, 131) |

0.805* |

| Height, cm, M ± SD (min, max) |

164.35±5.86 (150, 180) |

165.21±6.31 (150, 178) |

0.945* |

| BMI, M ± SD (min, max) |

28.25±3.55 (19.20, 39.06) |

28.82±5.29 (19.47, 44.37) |

0.384* |

| Number of pregnancies, n (%) |

|

|

|

| 0 |

42 (52.5) |

50 (55.6) |

0.471*** |

| 1 |

28 (35.0) |

32 (35.6) |

| 2 |

7 (8.8) |

3 (3.3) |

| 3 |

3 (3.8) |

5 (5.6) |

| Number of births, n (%) |

|

|

|

| 0 |

51 (63.8) |

55 (61.1) |

0.402*** |

| 1 |

25 (31.2) |

30 (33.3) |

| 2 |

4 (5.0) |

3 (3.3) |

| 3 |

0 (0.0) |

2 (2.2) |

| Cesarean delivery, n (%) |

26 (32.5) |

27 (30.0) |

0.725** |

| Contractions present, n (%) |

21 (26.2) |

16 (17.8) |

0.181** |

| Previous analgesia, n (%) |

4 (5.0) |

1 (1.1) |

0.189**** |

| BP1S, mmHg, M ± SD |

132.09 ± 14.85 |

130.42 ± 14.51 |

0.475** |

| BP1D, mmHg, M ± SD |

80.50 ± 9.09 |

80.97 ± 8.62 |

0.446** |

| MAP1, mmHg, M ± SD |

97.70 ± 9.72 |

97.45 ± 9.63 |

0.989** |

| VR1, bpm, M ± SD |

95.51 ± 16.89 |

95.94 ± 13.54 |

0.854° |

| SpO₂_1, %, M ± SD |

98.49±0.76 |

98.49±0.70 |

0.934* |

3.1. Blood Pressure and Ventricular Rate

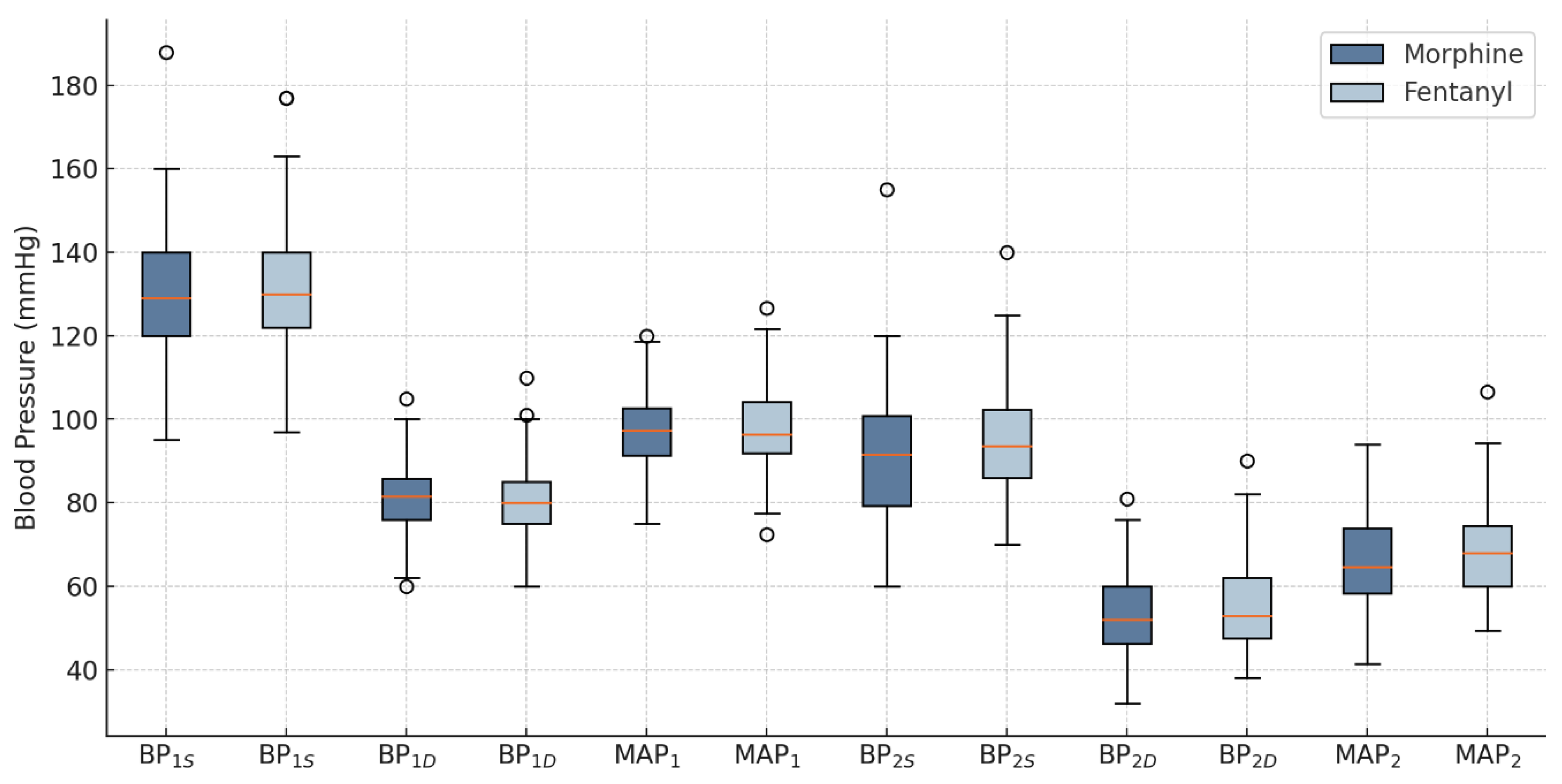

After the intervention, a significant difference in BP

2S was observed between the groups, with the F group showing significantly higher values compared to the M group (95.30±12.99 mmHg vs. 90.58±14.75 mmHg, p=0.032). No statistically significant differences were recorded for BP

2D and MAP

2 values between the F group and the M group (55.26±11.05 vs. 53.08±9.87, p=0.284, and 68.61±11.21 vs. 65.58±10.69, p=0.121, respectively), as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Blood pressure changes in groups. BPS - systolic blood pressure; BPD – diastolic blood pressure; MAP - mean arterial pressure; 1 - before the intervention; 2 - after the intervention.

Figure 2.

Blood pressure changes in groups. BPS - systolic blood pressure; BPD – diastolic blood pressure; MAP - mean arterial pressure; 1 - before the intervention; 2 - after the intervention.

The type of anesthesia did not statistically significantly influence the changes in blood pressure between the time before and after anesthesia administration,

Table 2.

Table 2.

Variation of blood pressure according to the type of anesthesia.

Table 2.

Variation of blood pressure according to the type of anesthesia.

| Parameter |

Group F |

Group M |

P-value |

| ΔBPS, mmHg, M ± SD |

−36.79 ± 17.64 |

−39.84 ± 18.88 |

0.278* |

| ΔBPD, mmHg, M ± SD |

−25.24 ± 13.29 |

−27.89 ± 11.73 |

0.168** |

| ΔMAP, mmHg, M ± SD |

−29.09 ± 13.40 |

−31.87 ± 13.08 |

0.172* |

The incidence of nausea did not show a statistically significant difference between the groups. In group F, 12 patients (15.0%) reported nausea, compared to 17 patients (18.9%) in group M (χ² = 0.453, p = 0.501), indicating a similar distribution of nausea incidence between the two groups.

In group F, only 1 patient (1.3%) experienced vomiting, compared to 10 patients (11.1%) in group M. Fisher’s exact test revealed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.011).

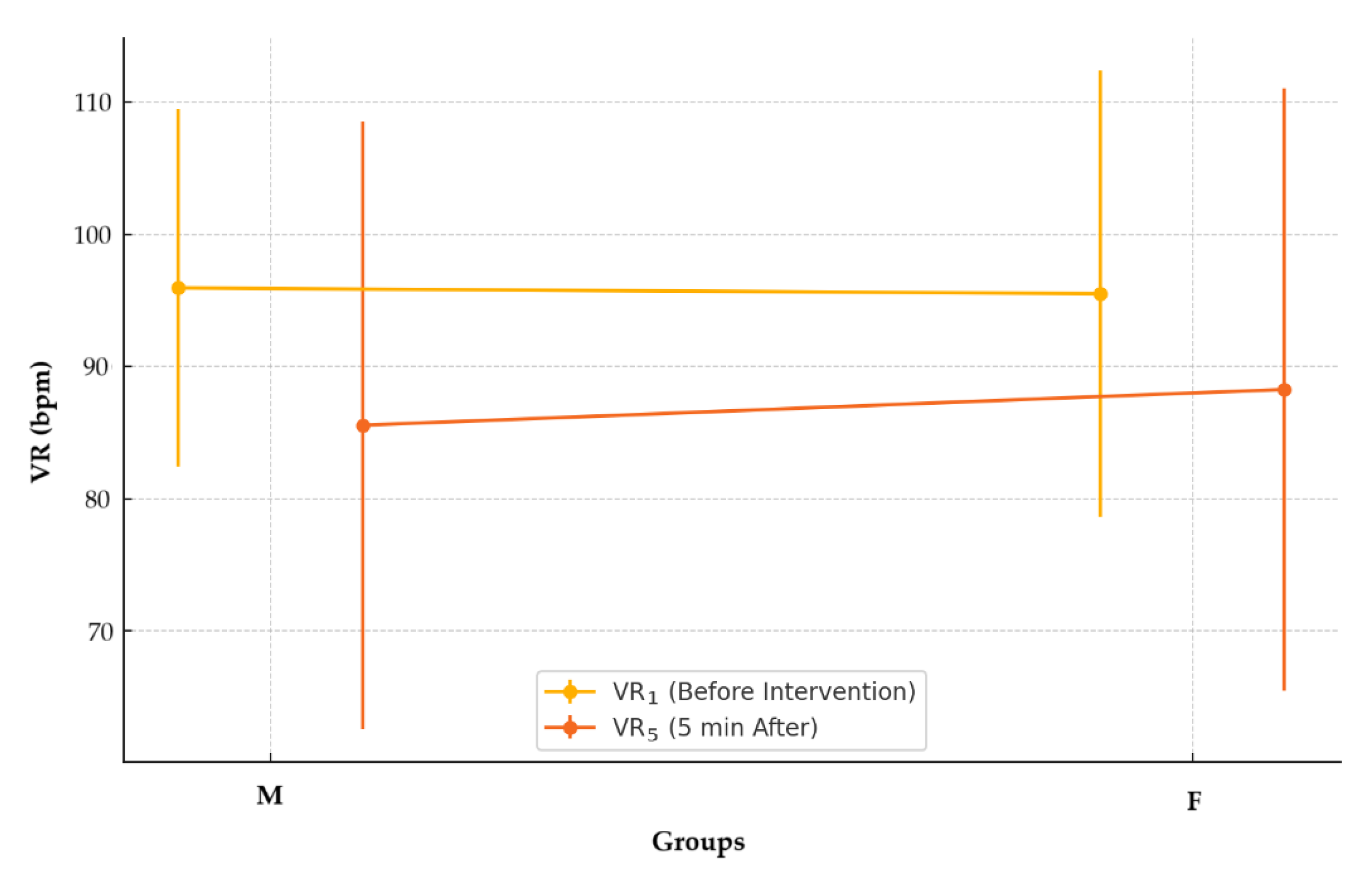

No statistically significant differences were identified in the VR

5 values recorded five minutes after the intervention between the two groups (M: 85.57 ± 22.99 bpm vs. F: 88.26 ± 22.82 bpm; p = 0.424),

Figure 3. The data were non-normally distributed (M, p < 0.001; F, p < 0.001), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences between the groups.

Figure 3.

Ventricular rates before and after intervention by anesthetic group.

Figure 3.

Ventricular rates before and after intervention by anesthetic group.

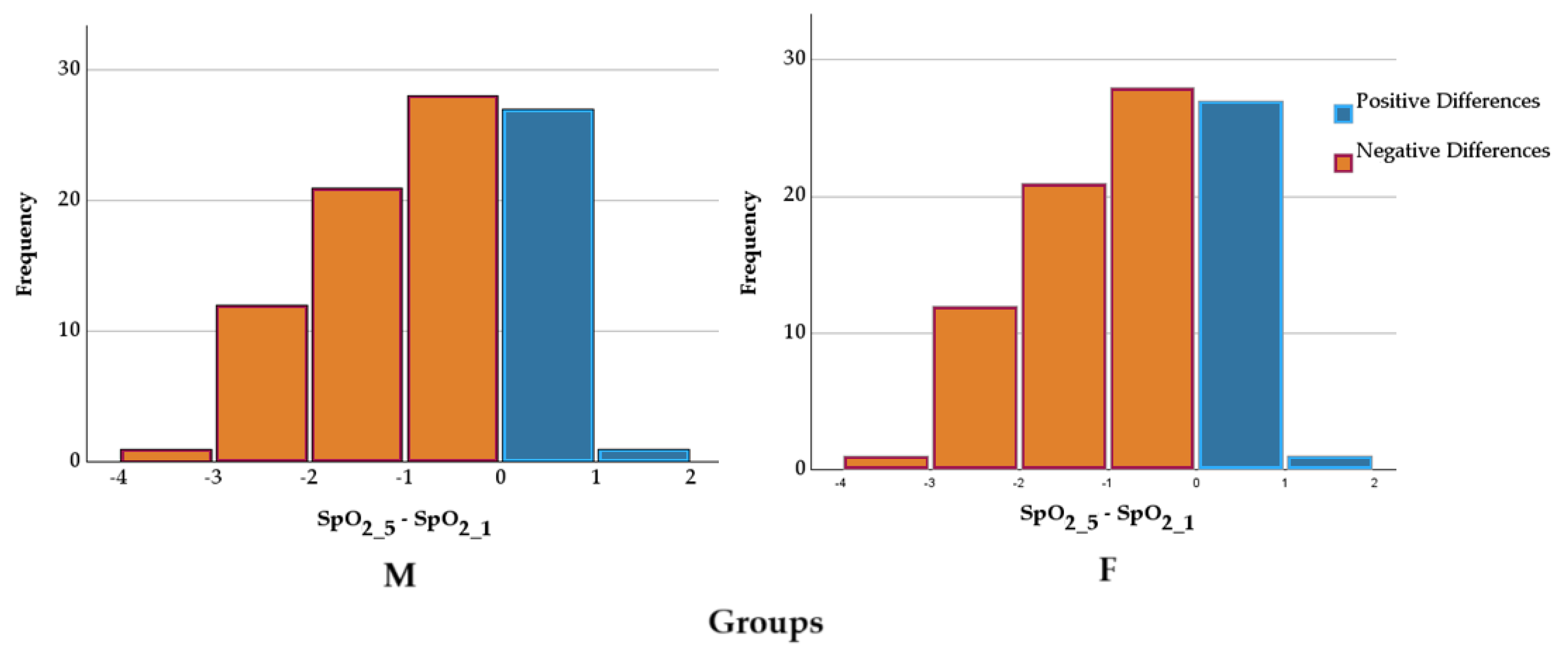

3.2. Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation

For both groups, the differences between SpO₂ values before and those 5 minutes after the intervention were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The results indicated a statistically significant difference between them for group M (98.49±0.70% vs. 97.28±1.17%, Z=−6.919, p<0.001) and group F(98.49±0.76% vs 97.34±1.10%, Z=−6.497, p<0.001). The medians of the differences suggest a consistent change in SpO₂ values between the two evaluation moments,

Figure 4. The differences in SpO₂ reduction between the groups were compared using an independent-samples t-test. The mean reduction in group M was −10.38±22.15%, while in group F, it was −7.25±22.78%. Levene's test indicated homogeneity of variances (F=0.515, p=0.425). The comparison of means did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the groups (t=−0.907, p=0.366, mean difference = −3.13, 95% CI: −9.94 ÷ 3.68). The effect size was small, as indicated by Cohen’s d (d=−0.139). These results suggest that the type of anaesthesia did not significantly influence the reduction in SpO₂.

Figure 4.

SpO₂ differences in groups according to anesthesia. SpO₂ - peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; 1 - before the intervention; 2 – 5 minutes after the intervention.

Figure 4.

SpO₂ differences in groups according to anesthesia. SpO₂ - peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; 1 - before the intervention; 2 – 5 minutes after the intervention.

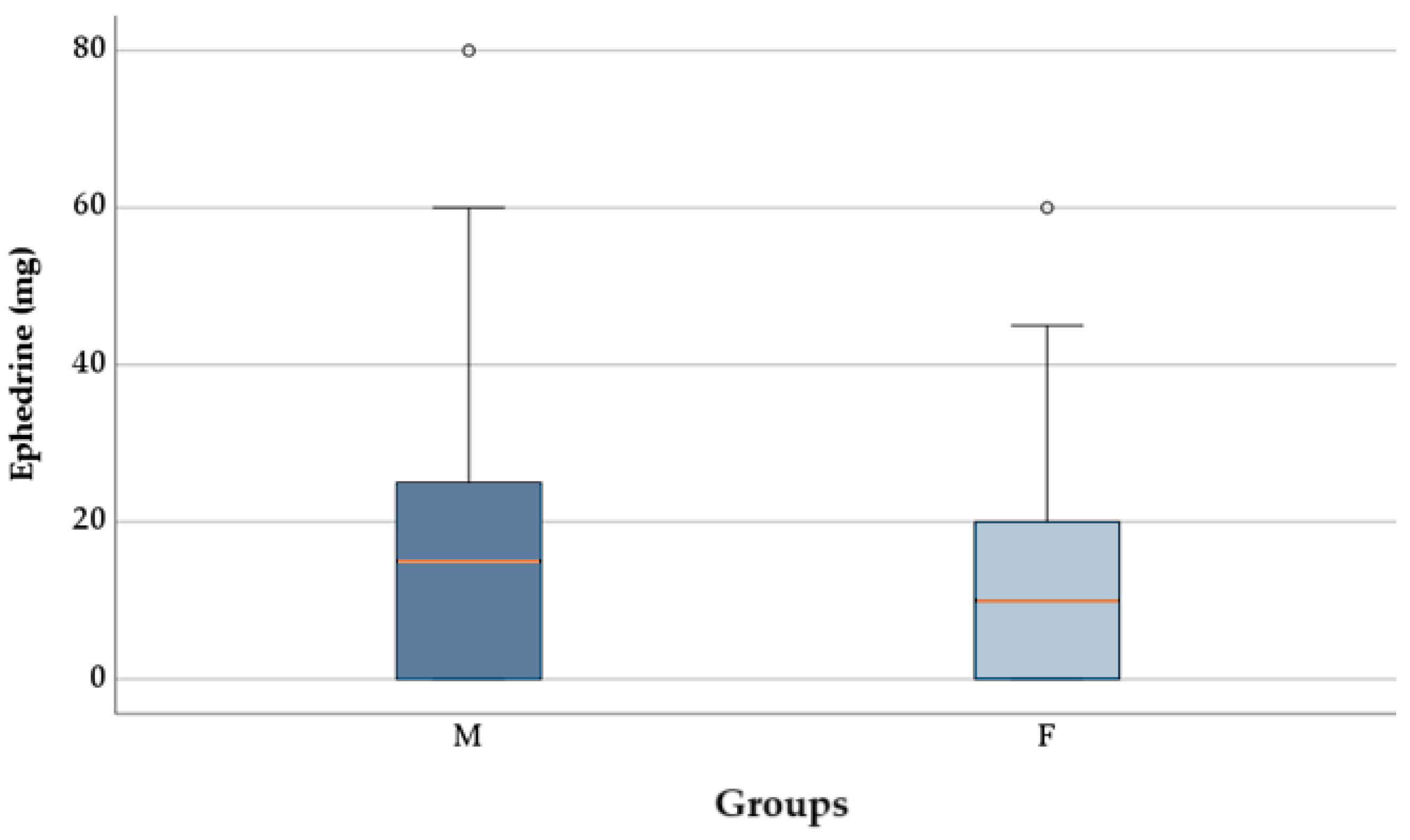

3.3. Administration of Ephedrine and Atropine Based on the Type of Anesthetic Used

The proportion of patients requiring ephedrine did not differ significantly between group M (67, 74.44%) and group F (53, 66.25%), according to the chi-square test (p = 0.242). The ephedrine dose was significantly lower in patients from group F (12.75 ± 13.26 mg) compared to group M (17.72 ± 16.73 mg), as indicated by the t-test [t(168) = 2.129, p = 0.035)],

Figure 5. Data distribution was normal in both groups, and Levene’s test confirmed the homogeneity of variances (p = 0.106).

Figure 5.

Ephedrine dosages between groups.

Figure 5.

Ephedrine dosages between groups.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients who received atropine based on the type of anaesthesia (group M: 9, 10% vs F: 3, 3.75%, p = 0.198).

4. Discussion

Studying the different effects of F and M on maternal hemodynamics in the context of cesarean section with spinal anesthesia is essential for understanding their impact on cardiovascular stability.

4.1. Blood Pressure and Ventricular Rate

The main cause of maternal hypotension post-spinal anesthesia is a sympathetic blockade, which triggers vasodilation along with a reduced venous return and subsequently lowers cardiac output, according to research [

10]. The selection of opioid adjuvants serves as a critical element for controlling the reactions of the cardiovascular system.

In this study, F was associated with significantly higher post-intervention BP

S than M (95.30 ± 12.99 mmHg vs. 90.58 ± 14.75 mmHg, p = 0.032). However, no significant differences were observed in BP

D or MAP between the two groups. The results match findings from Botea et al. (2022), who evaluated F's superior ability to maintain stable BP compared to M during intrathecal use during cesarean sections [

11]. F maintains better stability because of its lipophilic characteristics, allowing quicker system clearance and reduced hypotensive side effects [

12]. The hydrophilic nature of M produces delayed onset and prolonged duration of action that results in continuous hypotensive effects through continued activity on brainstem vasomotor centres [

13].

Nausea and vomiting are common side effects of spinal anesthesia, often triggered by hypotension-induced cerebral hypoperfusion and direct opioid effects on the chemoreceptor trigger zone. [

14]. In the present study, vomiting was significantly less frequent in the F group (1.3%) than in the M group (11.1%, p = 0.011), whereas nausea rates were similar. Research by DeSousa et al. (2014) supports that intrathecal M administration leads to an increased frequency of nausea and vomiting [

15]. The hydrophilic characteristics of this substance allow it to move cephalad through cerebrospinal fluid, leading to greater potential for nausea and vomiting. Due to its lipophilic properties, F reduces the rostral spread and reduces the risk of opioid-induced nausea and vomiting [

16]. The properties of F make it an ideal choice for managing maternal comfort during cesarean delivery.

Bradyarrhythmia after spinal anesthesia happens mainly through reduced venous return, decreased heart output, and increased parasympathetic response [

17]. The autonomic effects of opioid adjuvants can modulate this response along with heart rate changes. In the current study, no significant differences in ventricular rate were observed between the F and M groups five minutes after spinal anesthesia administration. This result contrasts with findings from Sibanyoni et al. (2022), who suggested that intrathecal M may be more likely to induce bradycardia due to its prolonged effects on central autonomic regulation [

18]. However, the lack of significant differences in the current study may be due to the relatively low opioid doses used and the effective management of hemodynamic changes with ephedrine and atropine.

4.2. Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation

Opioid adjuvants in spinal anesthesia can impact oxygenation by modulating central respiratory control, particularly through the depression of brainstem respiratory centres [

19].

In the present study, both F and M led to slight but statistically significant reductions in SpO₂ values five minutes after spinal anesthesia administration, though no significant differences were observed between the two groups. The current study findings match those presented by Sibanyoni et al. (2022), who documented M's extended reaction with central opioid receptors leading to delayed respiratory depression [

18]. The observed decreases in oxygen saturation monitored in the present research were minimal, thus demonstrating that both substances can be safely employed during spinal anesthesia without causing significant respiratory issues.

4.3. Administration of Ephedrine and Atropine Based on the Type of Anesthetic Used

Spinal anesthesia frequently causes hypotensive effects that need vasopressor therapy to maintain stable BP. The mixed α- and β-adrenergic agonist ephedrine serves as the primary medication to treat spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension because it enhances cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance [

5]. The administration of atropine occurs as a therapeutic measure for treating clinically significant bradycardia that develops after spinal anesthesia procedures.

In the current study, the administration frequency of ephedrine remained similar between patients who received F compared to those who received M (66.25% vs. 74.44%, p = 0.242). Research showed the F treatment group needed lower ephedrine doses than the M group for hypotension correction procedures (p = 0.035). F recipients received 12.75 ± 13.26 mg of ephedrine, while M subjects received 17.72 ± 16.73 mg. F demonstrates stronger hemodynamic stability, which results in a reduction of vasopressor intervention requirements.

The study findings support previous work by Ebrie et al. (2022), who demonstrated that F acts as a spinal anesthesia adjuvant to reduce local anesthetic doses, thereby limiting sympathetic blockade [

7]. Studies by Gallagher et al. (2024) demonstrated that F administered intrathecally leads to better BP control than M due to its quick elimination from systemic circulation and small effects on central hemodynamic management [

20].

The increased ephedrine requirement in the M group can be attributed to M's prolonged central nervous system effects, particularly its interaction with brainstem vasomotor centres, which exacerbates hypotension and necessitates greater vasopressor support [

9]. M’s hydrophilic nature also leads to prolonged spinal fluid circulation, potentially extending its depressant effects on cardiovascular function [

9].

Regarding atropine administration, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups (M: 10% vs. F: 3.75%, p = 0.198). This suggests that while both opioids may induce some degree of bradycardia, the incidence was relatively low and did not vary significantly between the groups. These results are consistent with findings by Shahid et al. (2024), who reported that intrathecal opioids rarely cause severe bradycardia, necessitating atropine intervention, especially at low doses [

2].

These findings support the preferential use of F as an adjuvant in spinal anesthesia for cesarean sections due to its association with lower vasopressor requirements and improved hemodynamic stability.

4.4. Study Limitations and Clinical Implications

The study generates crucial data regarding maternal BP responses to intrathecal injections of F versus M, yet some experimental challenges exist. The research was conducted exclusively at one centre, which constrains the widespread application of its results. Additional validation requires more extensive proof from larger multisite trials to confirm these results.

The clinical data support F's use as the better opioid choice for spinal anesthesia during cesarean sections because it maintains stable maternal hemodynamics while decreasing the need for vasopressors and vomiting symptoms. The study findings support why F has become more popular than M in obstetric anesthesia, especially for patients who need enhanced hemodynamic control or risk developing hypotension [

12].

5. Conclusions

The current study showed that F administered intrathecally provided superior BP control than M for spinal anesthesia during cesarean surgical procedures. The administration of F produced both elevated post-treatment BP measurements and decreased the need for vasopressor medication and vomiting incidents relative to morphine usage. The investigated opioid adjuvant delivery method proves F presents a safer use potential for obstetric anesthesia through improved maternal stability alongside superior comfort. Additional studies should investigate the neonatal effects together with long-term maternal recovery outcomes from using different opioids in spinal anesthesia for cesarian section procedures to improve these methodologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.M. and N.N.; methodology, R.C.M., N.N., and M.C.C.M.; software, H.T.J. and P.M.; validation, R.C.M., N.N., and M.C.C.M.; formal analysis, N.N. and R.C.M.; investigation, P.M., H.T.J., and M.C.C.M.; resources, M.C.C.M. and R.C.M.; data curation, P.M. and H.T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N., H.T.J. and R.C.M.; writing—review and editing, R.C.M., H.T.J., and P.M.; visualization, H.T.J. and N.N.; supervision, N.N., R.C.M., and M.C.C.M.; project administration, R.C.M. and N.N.; funding acquisition, N.N. and R.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Pelican Clinic Ethics Committee of Medicover Hospital (Approval No. 2421/10.12.2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of their admission to the hospital.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Nicoleta Negrut.

Acknowledgments

All authors thank the University of Oradea for providing the logistic facilities they used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| BP |

Blood Pressure |

| BPD

|

Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| BPS

|

Systolic Blood Pressure |

| MAP |

Mean Arterial Pressure |

| SpO₂ |

Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation |

| VR |

Ventricular Rate |

References

- Yu, C.; Gu, J.; Liao, Z.; Feng, S. Prediction of spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension during elective cesarean section: A systematic review of prospective observational studies. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 2021, 47, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, N.; Rashid, A. M. Knowledge, fear and acceptance rate of spinal anesthesia among pregnant women scheduled for cesarean section: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary care hospital in Karachi. BMC Anesthesiology 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chooi, C.; Cox, J.J.; Lumb, R.S.; Middleton, P.; Chemali, M.; Emmett, R.S.; Simmons, S.W.; Cyna, A.M. Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 8, Cd002251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KlÖHR, S.; ROTH, R.; HOFMANN, T.; ROSSAINT, R.; HEESEN, M. Definitions of hypotension after spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: Literature search and application to parturients. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2010, 54, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butwick, A. J.; Columb, M. O.; Carvalho, B. Preventing spinal hypotension during caesarean delivery: What is the latest? British Journal of Anaesthesia 2015, 114, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M. J.; Khan, S.; Khan, R. Frequency of post spinal hypotension in elective cesarean section after Spinal Anesthesia. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrie, A. M.; Woldeyohanis, M.; Abafita, B. J.; Ali, S. A.; Zemedkun, A.; Yimer, Y.; Ashebir, Z.; Mohammed, S. Hemodynamic and analgesic effect of intrathecal fentanyl with bupivacaine in patients undergoing elective cesarean section; a prospective Cohort Study. PLOS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HAMBER, E. Intrathecal lipophilic opioids as adjuncts to surgical spinal anesthesia. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 1999, 24, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, A. Intrathecal Morphine https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499880/ (accessed Feb 7, 2025).

- Šklebar, I. Spinal anaesthesia-induced hypotension in obstetrics: Prevention and therapy. Acta Clinica Croatica 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botea, M. O.; Lungeanu, D.; Petrica, A.; Sandor, M. I.; Huniadi, A. C.; Barsac, C.; Marza, A. M.; Moisa, R. C.; Maghiar, L.; Botea, R. M.; Macovei, C. I.; Bimbo-Szuhai, E. Perioperative analgesia and patients’ satisfaction in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: Fentanyl versus morphine. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhn, A. S.; Hobelmann, J. G.; Oyler, G. A.; Strain, E. C. Protracted renal clearance of fentanyl in persons with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2020, 214, 108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, M. V.; Reussien, E.; Vermeulen, B. A.; Zonneveld, S.; Westerman, E. M.; de Graaff, J. C.; Houweling, B. M. Serious adverse events after a single shot of intrathecal morphine: A case series and systematic review. Pain Research and Management 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, S.; Jedlicka, J.; Strinitz, E.; Niedermayer, S.; Chappell, D.; Hofmann-Kiefer, K.; Hinske, L. C.; Groene, P. Association between intraoperative hypotension and postoperative nausea and vomiting: A retrospective cohort study. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2024, 40, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSousa, K. A. Intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia: Current trends. World Journal of Anesthesiology 2014, 3, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008, 11 (Suppl. 2), S133–S153. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J. M. Hypotension and bradycardia during spinal anesthesia: Significance, prevention, and treatment. Techniques in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management 2000, 4, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanyoni, M.; Biyase, N.; Motshabi Chakane, P. The use of intrathecal morphine for acute postoperative pain in lower limb arthroplasty surgery: A survey of practice at an academic hospital. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palkovic, B.; Marchenko, V.; Zuperku, E. J.; Stuth, E. A.; Stucke, A. G. Multi-level regulation of opioid-induced respiratory depression. Physiology 2020, 35, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, A.; Maria, S.; Micalos, P.; Ahern, L. Effect of fentanyl compared to morphine on pain score and cardiorespiratory vital signs in out-of-hospital adult STEMI patients. International Journal of Paramedicine 2024, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).