1. Introduction

Cesarean delivery (CD) is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures, and its frequency is on the rise [

1]. Ensuring adequate pain control after CD is a significant concern for anesthesiologists, often necessitating the use of opioids both during hospitalization and after discharge [

2]. Proper pain management and minimizing opioid use after CD are crucial for preventing opioid-induced sedation, supporting the mother’s ability to care for and breastfeed the newborn, fostering mother-baby bonding, enabling early discharge, and improving patient satisfaction [

3,

4]. Additionally, effective analgesia promotes early mobilization, reducing the risk of thromboembolism, and is essential for preventing chronic pain development [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Thus, effective management of post-cesarean pain benefits both the mother and the baby, regardless of the level of relief achieved.

Consequently, for postoperative pain control, a multimodal strategy combining systemic and regional approaches is advised [

9]. Both a somatic component from the wound site and a visceral component from uterine and abdominal manipulation contribute to post-cesarean delivery pain [

10,

11]. The most widely utilized and proven opioid for post-CD analgesia is intrathecal morphine (ITM). According to a study, 150 mcg of ITM is the effective dose for postoperative analgesia in 90% of patients (ED90) following CD when used as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen [

12].

Even though intrathecal morphine (ITM) has a longer duration of action than lipophilic opioids, it can cause unwanted side effects as delayed respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, and itching in mothers. These side effects can have a detrimental influence on patient satisfaction overall [

13,

14]. Alternative analgesic techniques that decrease opioid use are required in order to lessen these side effects and offer efficient analgesia to patients who are unable to receive long-acting neuraxial opioids for any reason. Intraperitoneal local anesthetic instillation (IPLA) is one such method. In order to prevent visceral afferent signals and influence the area of administration, local anesthetics (LA) cause a reversible disruption of nerve impulse transmission [

15]. This may lessen the impression of pain by altering visceral nociception and associated nausea reactions [

16].

Compared to the placebo group, fewer women in the intraperitoneal lidocaine group sought opioids for severe postoperative pain, and lidocaine also decreased early postoperative pain, according to a randomized, placebo-controlled study examining the efficacy of intraperitoneal lidocaine in reducing post-cesarean pain [

17]. Local anesthetic wound infiltration (LWI) is an additional method [

18]. Since the inflammatory reaction to the surgical wound causes some postoperative pain, lowering this inflammation may help with analgesia [

19]. Local anesthetic wound infiltration for post-cesarean analgesia has been shown to effectively relieve postoperative pain, according to a comprehensive review and meta-analysis [

18].

The combination of IPLA, LWI, and RAI with a placebo for analgesia during cesarean delivery under general anesthesia has been compared in one randomized controlled trial in the literature [

20]. It is logical to believe that following a cesarean section, local anesthetic instillation into the peritoneum and infiltration into all layers of the abdomen may improve postoperative analgesic efficacy.

In order to reduce post-cesarean pain in women undergoing elective cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia (SA), we expected that the combination of IPLA, LWI, and RAI would have analgesic efficacy comparable to intrathecal morphine (ITM). Furthermore, we investigated the hypothesis that the combination of local anesthetic instillation into the peritoneum and infiltration into all layers of the anterior abdominal wall would provide postoperative pain scores comparable to ITM while lowering the frequency of opioid-related adverse effects.

2. Materials and Methods

46 pregnant women, ages 18 to 50, with ASA II classification, full-term singleton pregnancies, scheduled for elective cesarean sections with Pfannenstiel incisions under spinal anesthesia at Atatürk University Medical Faculty Hospital, participated in this prospective randomized double-blind study. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study was authorized by the Atatürk University Medical Faculty Hospital Ethics Committee (Ethical Committee No: B.30.2.ATA.0.01.00/339). Before the first patient was enrolled, the study was listed on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05405049).

The study excluded patients who were contraindicated for neuraxial anesthesia, declined to participate, had a BMI > 35 kg/m2, ASA ≥ 3, diabetes, preeclampsia, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain or a history of neuropathic pain, had received intraoperative opioids for pain, had undergone abdominal surgery in the past, had been switched to general anesthesia after spinal anesthesia failed, had excessive bleeding or uterine atony during surgery, had drains in the infiltration area, were unable to comprehend the VAS, or had a history of drug addiction or mental health conditions.

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS), with 0 representing no pain and 100 representing the worst suffering possible, was explained to the patients prior to the procedure, the study’s goal, and its application during the postoperative phase. A statistician-managed computerized random number table was used to randomly allocate the patients to two equal groups, Group LWI+RAI+IPLA and Group M (Group Morphine). Randomization codes were used to consecutively number opaque envelopes. Before spinal anesthesia was administered, the principal investigator opened these envelopes and got the sterile medications ready for the surgeon. The intraoperative and postoperative data were recorded by a different anesthesiologist who was blind to the research groups. Both the patients, surgeons, and the person evaluating the patients during and after surgery were blinded to the group assignments.

As soon as the patient walked into the operating room, standard ASA monitoring was put into place. A 25-gauge Whitacre needle was used to inject spinal anesthesia at the L3-L4 or L4-L5 intervertebral area after the patients had been seated and their skin had been sterilized and localized with 2% lidocaine. For women undergoing cesarean sections, Group IPLA+RAI+LWI administered a 0.5% bupivacaine with 15 µg fentanyl solution that was calibrated for body weight and height. Group M received a similar 0.5% bupivacaine solution with 150 µg of morphine and 15 µg of fentanyl after height and body weight were taken into account [

21].

After the procedure, the patients were positioned supine with a 15° angle and left uterine displacement. Noninvasive blood pressure was measured every minute for the first 15 minutes after spinal anesthesia, then monitored at 3-minute intervals until the end of the operation. Sensory block levels were assessed by checking for cold sensory loss, and the operation began once the T4 level was reached. Hypotension was defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure of 20% or more below the baseline value. In the case of hypotension, intravenous (IV) norepinephrine (5 µg) or ephedrine (5 mg) was administered until blood pressure returned to baseline, depending on the patient’s heart rate. For persistent or recurrent hypotension, vasopressor therapy was repeated every minute. Bradycardia was defined as a heart rate below 50 beats per minute, and in this case, 1 mg IV atropine was administered. If the patient experienced pain during the operation, 25-50 µg IV fentanyl was given, as per the anesthesiologist’s preference. All patients were given 4 mg IV ondansetron for nausea prophylaxis. After the baby was delivered, oxytocin was administered according to institutional protocol.

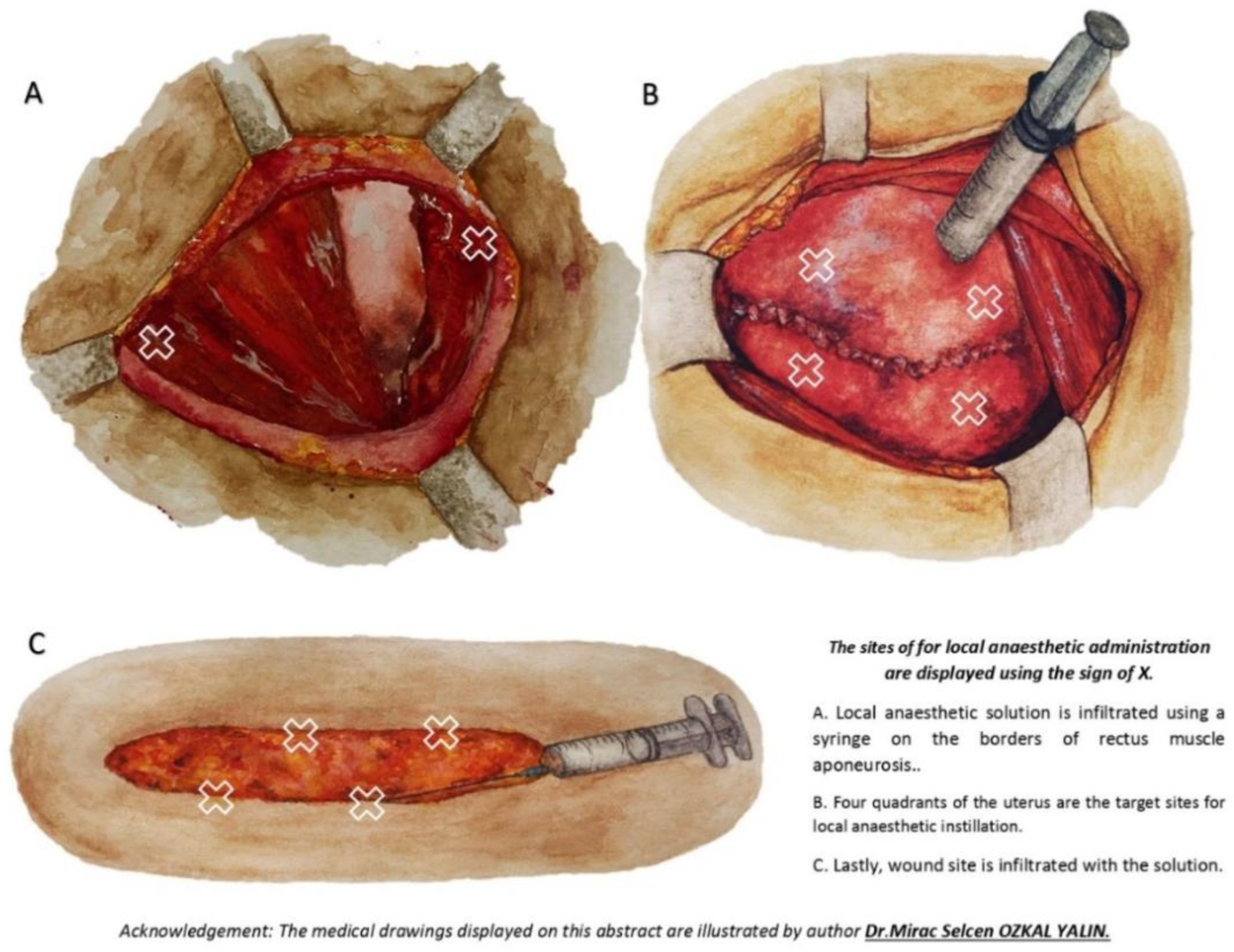

In Group LWI+RAI+IPLA, after the delivery of the newborn and placenta, the uterus was closed. After the accumulated blood in the pelvis was carefully wiped with surgical towels and hemostasis was achieved, a sterile solution containing 15 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine, 15 ml of 2% lidocaine, and 1:200,000 epinephrine was prepared for the surgeon. A total of 10 ml of this solution was carefully dripped into the uterine peritoneal area in all four quadrants of the uterus before the fascia was closed. The parietal peritoneal layer was left open in all patients, as it was not sutured during the surgical procedure at the institution. Subsequently, 10 ml of the solution was infiltrated into the edges of the rectus aponeurosis, and the remaining 10 ml was infiltrated subcutaneously at the wound site (

Figure 1).

Similar to Group LWI+RAI+IPLA, Group M received 30 milliliters of saline in the same amounts and at the same locations. Patients received 50 mg of dexketoprofen and 1 g of paracetamol intravenously (IV) 30 minutes prior to the procedure’s conclusion. All patients received conventional multimodal analgesia following the procedure, which included intravenous dexketoprofen 50 mg every 12 hours for the following 24 hours and intravenous paracetamol 15 mg/kg every 6 hours. It was intended to provide 2 mg of morphine subcutaneously, with a maximum dose of 20 mg every 4 hours, if the patient’s pain score was greater than 3 during the first 24 hours. In the case of nausea and vomiting, IV ondansetron 4 mg was given and repeated every 8 hours if necessary. If pruritus occurred, a 10 mg cetirizine tablet was administered.

Nausea and vomiting were evaluated on a scale of 0 to 3: 0 = no nausea or vomiting, 1 = mild nausea not requiring treatment, 2 = moderate nausea responding to treatment, 3 = severe nausea or vomiting not responding to treatment. Itching was also rated on a scale of 0 to 3: 0 = no itching, 1 = mild itching not requiring treatment, 2 = moderate itching responding to treatment, 3 = severe itching not responding to treatment.

A 5-point rating system was used to gauge patient satisfaction 24 hours after surgery (1 being extremely displeased, 2 being dissatisfied, 3 being mild, 4 being satisfied, and 5 being very satisfied). The Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale was used to measure the degree of sedation [

22]. Additionally, patients were observed for respiratory depression, which is characterized by a respiratory rate of less than eight breaths per minute. For the first 12 hours, the respiratory rate and sedation levels were checked hourly; for the next 12 hours, they were checked every two hours.

Pain during movement (such as moving forward and backward in bed) and at rest (lying motionless in bed) was assessed using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS, 0-100 mm, where 0 = no pain and 100 = worst possible pain) at postoperative 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours. Data collected included patients’ age, weight, height, BMI, gestational age, operation time (from the beginning of the skin incision to the end of skin closure), maximal block level, time to the first opioid requirement (from spinal anesthesia administration to the first opioid use), time to return of bowel movements (defined as the time from the end of the operation to the first passage of gas), local inflammation at the wound site, conversion to general anesthesia, and maternal satisfaction.

The amount of morphine taken overall within the first 24 hours after surgery was the main result. The pain scores at rest and during movement at 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours were one secondary outcome. The duration until the first opioid need and the prevalence of opioid-related adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, pruritus, drowsiness, and respiratory depression, were additional secondary outcomes.

Sample Size

According to Anthony A. Bamigboye et al.’s study [

20], 400 ± 147 mg of pethidine were taken in the first 24 hours after surgery by the group that received an intraperitoneal drip in addition to local anesthetic infiltration into the wound. The G*Power program was used to determine that, with 80% power and a 95% confidence level, 23 participants per group (a total of 46 participants) would be needed for the study in order for the 80 mg difference in consumption between this group and the morphine group to be statistically significant.

Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data, the IBM SPSS 20 statistical software was used. A mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, percentage, and number were used to display the data. The Q-Q plot, skewness, kurtosis, Shapiro-Wilk test, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to evaluate the normal distribution of continuous values.

If the normal distribution condition was satisfied, the Independent Samples t-test was employed for comparisons between two independent groups; if not, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. When the normal distribution requirement was satisfied, the Repeated Measures ANOVA test was employed for comparisons with more than two dependent groups; otherwise, the Friedman test was employed. Depending on the sphericity condition, the Repeated Measures ANOVA test was conducted using either the Sphericity Assumed or Greenhouse-Geisser techniques. Following the Repeated Measures test, post-hoc analyses were conducted using Tamhane’s T2 test for non-homogeneous variances and the Tukey test for homogeneous variances. Following the Friedman test, post-hoc analyses were conducted using the Friedman 2-way ANOVA by ranks (k samples) test. Fisher’s exact test was used for 2x2 comparisons across categorical variables when the expected value was less than 3, the Pearson chi-square test was used when the expected value was larger than 5, and the Chi-square Yates test was used when the expected value was between 3 and 5. When comparing more than two 2x2 categorical variables, the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test was used when the expected value was less than five, and the Pearson chi-square test was used when the expected value was larger than five. A p-value of less than 0.05 was taken into consideration.

3. Results

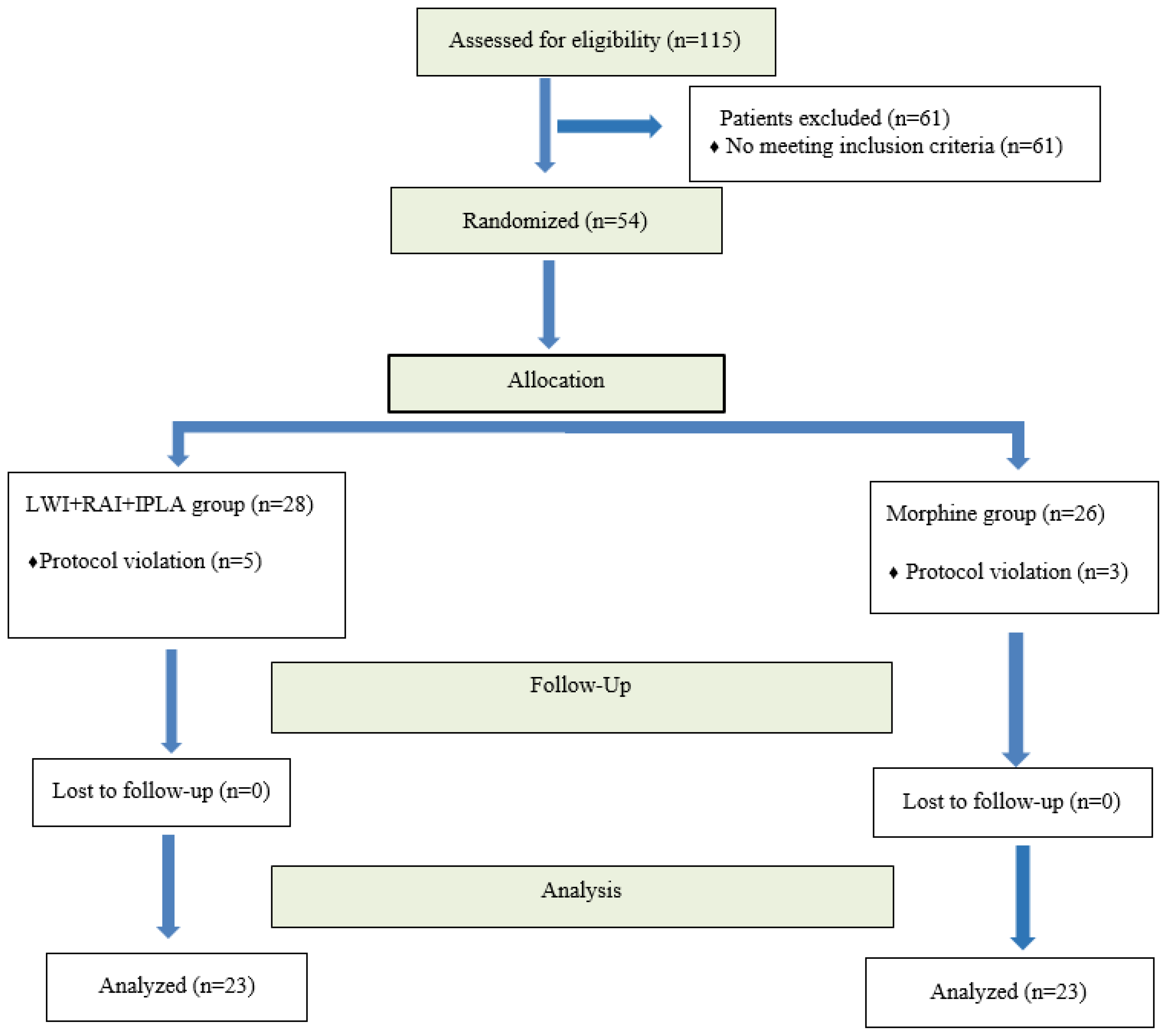

Figure 2 displays the CONSORT flowchart for the investigation. The eligibility of a total of one hundred patients was evaluated. Sixty-one patients were excluded because they did not match the inclusion criteria or refused to participate. As a result, 54 subjects were initially added to the trial. Eight patients were eliminated from the study after randomization because of a procedure violation involving the placement of a drain in the infiltration zone. Five of these patients were in Group LWI+RAI+IPLA, while three were in Group M. Consequently, 46 individuals were included in the final intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 1 displays the patients’ demographic information and operating times. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05,

Table 1), with the exception of height (p = 0.023).

Table 2 displays the groups’ postoperative data. There was no significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05,

Table 2), with the exception of the time of first opioid demand (p = 0.034). Furthermore, the total amount of morphine ingested in the first 24 hours after surgery did not differ statistically significantly between the groups (p = 0.075,

Table 2).

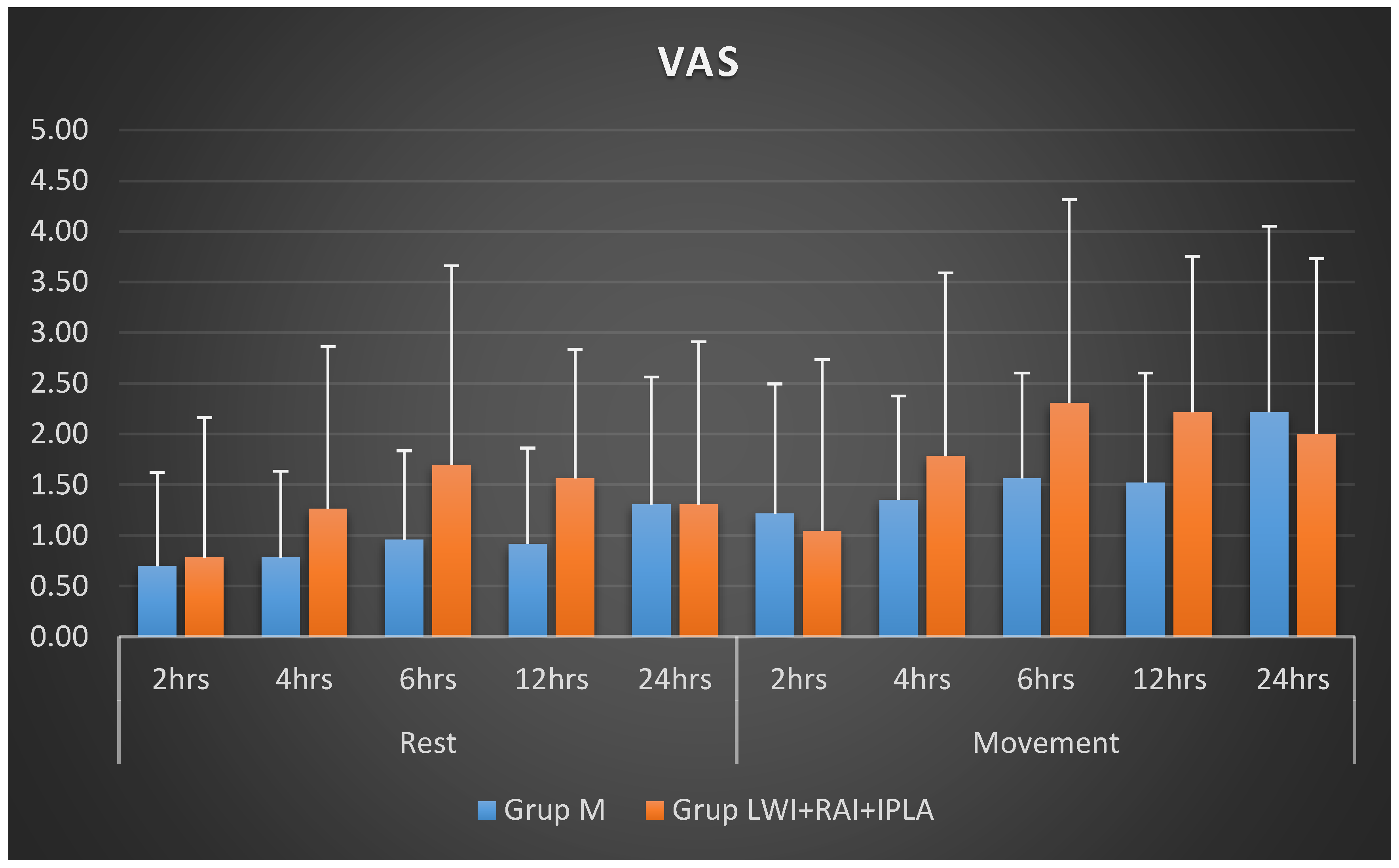

The comparison of active and passive VAS scores obtained at various periods within each group and across groups is shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2. Regarding the active and passive VAS scores recorded at all times, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05,

Table 3,

Figure 3). Group M’s changes in active and passive VAS scores over time did not differ significantly from one another in the intra-group comparison (p > 0.05,

Table 2). On the other hand, Group LWI+RAI+IPLA showed a statistically significant difference in both active (p = 0.004) and passive (p = 0.033) VAS scores over time. This difference was observed between 2-6 hours and 2-12 hours for active VAS scores, and only between 2-6 hours for passive VAS scores.

The two groups’ occurrences of pruritus, postoperative nausea/vomiting, and intraoperative maximal block level are displayed in

Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05,

Table 4), with the exception of pruritus (p = 0.032). Only 8.7% of patients in Group LWI+RAI+IPLA had nausea and vomiting, compared to 30.4% of patients in Group M. Compared to 8.7% of patients in Group LWI+RAI+IPLA, 34.8% of patients in Group M experienced pruritus. None of the patients in either group had respiratory depression.

4. Discussion

Neither the total amount of morphine consumed in the first 24 hours postoperatively nor the pain scores measured at specific times during the first 24 hours showed any significant differences in the current study, which compared the combination of instilling intrathecal morphine (ITM) into the peritoneum and infiltrating local anesthetic into all layers of the anterior abdominal wall to reduce post-cesarean pain. Other opioid-related adverse effects were equally prevalent in both groups, despite itching being much more prevalent in the ITM group. The ITM group’s time to first analgesic necessity was noticeably longer. These results imply that the two analgesic methods offer comparable and efficient pain management.

ITM, intraperitoneal local anesthetic (IPLA), or local anesthetic wound infiltration (LWI) without ITM are the three main methods of post-cesarean analgesia that are studied in the literature. For instance, there was no discernible difference between the lidocaine and placebo groups in terms of the total amount of morphine taken for breakthrough pain in the first 24 hours after surgery in a randomized, placebo-controlled study that examined the effectiveness of 20 ml intraperitoneal lidocaine for reducing post-cesarean pain [

17]. There was no discernible difference in pain levels between the two groups throughout the first 24 hours following cesarean delivery, despite the lidocaine group reporting lower pain scores during movement and during rest two hours later. Every patient in that study received ITM.

The impact of local anesthetic wound infiltration on analgesia following cesarean section was investigated in a comprehensive review and meta-analysis comprising 21 research [

18], taking into account patients who received intrathecal morphine (ITM) as well as those who did not. Lower pain scores during rest and movement in the first 24 hours after surgery, as well as a significant decrease in opioid intake, were found by the analysis. Nevertheless, the subgroup analysis revealed that women who did not receive ITM had lower opioid usage than those who did.

Continuous wound infiltration and ITM were compared for postoperative analgesia in cesarean sections performed under combination spinoepidural anesthesia in a research by Kainu et al. [

23]. In comparison to the wound infiltration group, ITM was demonstrated to lower the mean oxycodone consumption within the first 24 hours. However, there was no discernible difference between the two groups’ pain scores.

The results of these studies suggest that when ITM is administered, both intraperitoneal local anesthetic instillation (IPLA) and local anesthetic wound infiltration (LWI) have minimal effects on reducing opioid consumption in the first 24 hours postoperatively and may have limited impact on pain scores. In contrast, in our current study, where ITM was applied to one group and not to the other, and IPLA, LWI, and rectus abdominis infiltration (RAI) were used in combination in the non-ITM group, we found that morphine consumption and pain scores were similar in both groups at 24 hours postoperatively. This suggests that the combination of local anesthetic administration at the incision site and intraperitoneally could have provided more effective analgesia by addressing pain from both superficial structures and the peritoneum. This dual mechanism may explain the positive results observed in our study, even without ITM.

In a randomized controlled study by Bamigboye et al. [

20] on cesarean deliveries (CD) performed under general anesthesia, 30 ml of local anesthetic was administered to one group as IPLA+RAI+LWI, while the same volume of saline was given to the other group at the same anatomical sites. The results showed that opioid consumption in the first hour postoperatively was significantly reduced in the group receiving local anesthetic (LA). However, no difference was observed between the groups in opioid consumption at the 8-hour and 24-hour marks. Furthermore, pain scores in the group receiving LA were significantly lower in the first 4 hours postoperatively compared to the saline group, with a trend towards reduced pain continuing over the 24-hour period, although this trend was not statistically significant.

In contrast, our study applied intrathecal morphine (ITM) to one group, and while we found no significant difference between the groups in terms of opioid consumption over the first 24 hours (except for the time of first opioid requirement), pain scores were consistently lower in both groups during the early postoperative hours. Specifically, the LWI+RAI+IPLA group provided analgesic efficacy comparable to the morphine group in terms of both opioid consumption and pain scores. The pain relief provided by LWI+RAI+IPLA was expected to decrease over time due to the naturally declining effect of local anesthetics. This was reflected in the significant difference found in the active VAS scores between 2-6 hours and 2-12 hours and in the passive VAS scores between 2-6 hours in the LWI+RAI+IPLA group. On the other hand, no significant difference was found in the changes of active and passive VAS scores over time in the morphine group, likely due to the long-acting nature of morphine.

Our work shows that the combination of LWI+RAI+IPLA can offer an efficient substitute for ITM, contributing to multimodal analgesia of equal quality, even though the analgesic impact of local anesthetics fades with time. Since we think opioid intake would be lower in the first few hours after surgery because of the lower pain scores, we specifically looked at the overall amount of opioids consumed in the first 24 hours. Additionally, the first several hours following a cesarean delivery usually see a higher demand for analgesia. In order to improve maternal comfort, lessen pain concentration, encourage early mobilization and nursing, and promote early bonding with the newborn, it is critical to reduce pain scores early on while utilizing fewer opioids.

In a study on cesarean sections under spinal anesthesia [

24], the combination of IPLA, LWI, and a placebo was compared for postoperative analgesia, without the use of ITM. While no significant difference was found between the groups regarding the time to first opioid requirement and the total opioid consumption over 24 hours, instillation was found to significantly reduce pain scores during movement in the early postoperative period compared to placebo. However, in later hours, the lowest pain scores at both rest and during movement were observed in the LWI group at all time points. It was speculated that the effect of instillation wore off in the late postoperative period, and the subcutaneous local anesthetic may have been slowly absorbed by the tissue, eventually reaching effective blood levels. This led to the conclusion that combining both techniques (instillation and local wound infiltration) may improve postoperative pain management in women undergoing cesarean section.

In our present study, we combined IPLA and LWI techniques with RAI, providing analgesia to both the peritoneum and all layers of the anterior abdominal wall. This resulted in analgesic efficacy similar to that of ITM. While a previous study used a mixture of 10 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 10 ml of 2% lidocaine (20 ml total), we used a similar local anesthetic mix, but in a higher volume of 30 ml (15 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 15 ml of 2% lidocaine) with the addition of epinephrine. The inclusion of long-acting bupivacaine was aimed at achieving stronger and longer-lasting analgesia, due to the synergistic effects of the two anesthetics. In line with a study by Tharvet et al. [

25], we added epinephrine to prolong the duration of the anesthetic’s action, which we believe contributed to the analgesic efficacy comparable to ITM.

In our study, the morphine group’s delay to the first analgesic demand was noticeably longer. This may be explained by the delayed onset of morphine due to its hydrophilic nature, as well as the delayed absorption and delayed efficacy of local anesthetics from the tissues.

While ITM offers effective analgesia, it is known to cause side effects like nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and sedation [

26]. The severity of pruritus is dose-dependent, and it tends to be less bothersome at lower doses, typically not requiring treatment [

27]. In a study by Kainu et al., where 160 micrograms of morphine was used, pruritus was observed in 70% of patients, though only a few required treatment for it. Nausea was found in 14% of ITM patients, but no significant difference was observed between groups. In our study, pruritus was observed in 34.8% of patients in the ITM group and 8.7% in the other group, with the difference being statistically significant. However, no medication was required for pruritus in our study. The difference in pruritus incidence between our study and Kainu et al.’s [

23] study might be due to the lower dose of ITM used in our study. Nausea and vomiting occurred in 30.4% of patients in the ITM group and 8.7% in the other group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Regarding patient heights, we found a substantial difference between the groups in our study. However, we think that the height difference has no bearing on the study’s findings because the local anesthetic dose for spinal anesthesia was determined using both height and weight, and there was no discernible difference between the groups’ intraoperative maximal block levels.

Our study demonstrated that the LWI+RAI+IPLA technique for postoperative cesarean analgesia provided analgesic efficacy comparable to ITM. Additionally, side effects such as itching, nausea, and vomiting were less frequent in the LWI+RAI+IPLA group compared to the ITM group, which could be considered an advantage of this method. While general anesthesia is not typically the first choice for cesarean deliveries, it may be necessary for women who cannot undergo spinal or epidural anesthesia or who prefer regional anesthesia alternatives. In such cases, the LWI+RAI+IPLA technique may provide a valuable option for pain management.

Abdominal plane blocks are also used for post-cesarean analgesia; however, the LWI+RAI+IPLA technique is simpler to perform. The application of abdominal wall nerve blocks requires specialized training and ultrasonography (USG). In contrast, the LWI+RAI+IPLA technique can be effectively administered in resource-limited settings, such as those without access to USG or by individuals who have not received training in nerve blocks. This makes it a more accessible and easier-to-implement option for providing analgesia.

Limitations

There are several limitations in our study that should be acknowledged. First, we did not assess the level of sensory block, particularly during the early postoperative period. The residual effects of spinal anesthesia could potentially influence opioid consumption and pain scores, and this factor was not considered. Additionally, we did not measure opioid consumption at specific time intervals within the first 24 hours postoperatively; instead, we only calculated the total amount of opioids consumed over the 24-hour period. Since most patients were discharged 24 hours after surgery, we were limited in our ability to evaluate opioid consumption and pain scores beyond this time frame. Furthermore, evaluating patient recovery was not one of the primary or secondary objectives of this study. Future research could focus on assessing the impact of these analgesic methods on obstetric recovery quality using scales like the ObsQoR-10, which evaluates various aspects of postoperative recovery such as pain, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and breastfeeding.

5. Conclusions

Our research concludes that the application of a local anesthetic, which involves infiltration into all layers of the anterior abdominal wall and instillation into the peritoneum, offers an analgesic efficacy that is similar to that of ITM but with fewer adverse effects. For patients who cannot receive neuraxial morphine or who are not suitable for neuraxial anesthesia, we think the LWI+RAI+IPLA technique is a simple and efficient way to provide analgesia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I., A.D. and G.N.C.S.; methodology, R.I., A.D., M.A.Y. and K.K.; software, M.S.O.Y. and M.A.; validation, A.D. and I.I..; formal analysis, K.K., C.A..; investigation, A.D., G.N.C.S., and I.I..; data curation, K.K. A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I., A.D.; writing—review and editing, G.N.C.S., I.I. and M.A.; visualization, M.S.O.Y., S.T.K.; supervision, R.I., A.D., M.A.Y.; project administration, R.I., A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Atatürk University Medical Faculty Hospital Ethics Committee (Ethical Committee No: B.30.2.ATA.0.01.00/339).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ecker, J.L.; Frigoletto, F.D. Jr. Cesarean delivery and the risk-benefit calculus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:885–888. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, B.T.; Franklin, J.M.; Bykov, K.; Avorn, J.; Shrank, W.H.; Brennan, T.A.; et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-na€ıve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(353):353.e1–353.e18. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Patel, S.D.; Jadin, S.; Carvalho, B.;, Halpern, S.H. Transversus abdominis plane block compared with wound infiltration for postoperative analgesia following cesarean delivery: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:1710–27. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J.B.; Jeppesen, I.S.; Jørgensen, H.; Wetterslev, J.; Møiniche, S. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1919–27. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Patel, S.D.; Jadin, S.; Carvalho, B.; Halpern, S.H. Transversus abdominis plane block compared with wound infiltration for postoperative analgesia following Cesarean delivery: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2020 Dec;67(12):1710-1727. [CrossRef]

- Gadsden, J.; Hart, S.; Santos, A.C. Post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Anesth Analg 2005; 101(Suppl 5): S62-9. [CrossRef]

- Karlström, A.; Engström-Olofsson, R.; Norbergh, K.G.; Sjöling, M.; Hildingsson, I. Postoperative pain after cesarean birth affects breastfeeding and infant care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2007; 36: 430-40. [CrossRef]

- Eisenach, J.C.; Pan, P.H.; Smiley, R.; Lavand’homme, P.; Landau, R.; Houle, T.T. Severity of acute pain after child¬birth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain 2008; 140: 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.H. Post cesarean delivery pain management: multimodal approach. Int J ObstetAnesth. 2006;15(3):185-8. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, J.G.; Curley, G.; Carney, J.; et al. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2008; 106:186–191. [CrossRef]

- Lavand’homme, P. Postcesarean analgesia: effective strategies and association with chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006; 19:244–248. [CrossRef]

- Sviggum, H.P.; Arendt, K.W.; Jacob, A.K.; Niesen, A.D.; Johnson, R.L.; Schroeder, D.R.; Tien, M.; Mantilla, C.B. Intrathecal Hydromorphone and Morphine for Postcesarean Delivery Analgesia: Determination of the ED90 Using a Sequential Allocation Biased-Coin Method. Anesth Analg 2016; 123: 690–7. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J.B.; Jeppesen, I.S.; Jørgensen, H.; Wetterslev, J.; Møiniche, S. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1919–1927. [CrossRef]

- Siti Salmah, G.; Choy, Y.C. Comparison of morphine with fentanyl added to intrathecal 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine for analgesia after caesarean section. Med J Malaysia. 2009;64:71–74.

- Lui, K.C.; Chow, Y.F. Safe use of local anaesthetics: prevention and management of systemic toxicity. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:470–475.

- Kahokehr, A.; Sammour, T.; Soop, M.; Hill, A.G. Intraperitoneal use of local anesthetic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:637–656. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Carvalho, J.C.; Downey, K.; Kanczuk, M.; Bernstein, P.; Siddiqui, N. Intraperitoneal Instillation of Lidocaine Improves Postoperative Analgesia at Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(2):554-9. [CrossRef]

- Oluwaseyi, A.; Ituk, U.; Habib, S.A. Local anaesthetic woundinfiltration for postcaesarean section analgesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016 Oct;33(10):73142. [CrossRef]

- Dray, A. Inflammatory mediators of pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:125-31. [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, A.A.; Justus, H.G. Ropivacaine abdominal wound infiltration and peritoneal spraying at cesarean delivery for preemptive analgesia. Int J GynaecolObstet. 2008;102:160–164. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, K.M.; Ali, M.A.; Ullah, H. Comparison of spinal anesthesia dosage based on height and weight versus height alone in patients undergoing elective cesarean section. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016 Apr;69(2):143-8. [CrossRef]

- Pasero, C. Assessment of sedation during opioid administration for pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2009;24:186-190. [CrossRef]

- Kainu, J.P.; Sarvela, J.; Halonen, P.; Puro, H.; Toivonen, H.J.; Halmesmäki, E.; Korttila, K.T. Continuous wound infusion with ropivacaine fails to provide adequate analgesia after caesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012 Apr;21(2):119-24. [CrossRef]

- Dagasan Cetin, G.; Dostbil, A.; Aksoy, A.; Kasali, K.; Ince, R.; Kahramanlar, A.A.; Atalay, C.; Topdagi Yilmaz, E.P.; Ince, I.; Ozkal, M.S. Intraperitoneal instillation versus wound infiltration for postoperative pain relief after cesarean delivery: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023 Jan;49(1):209-219. [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A.A.; Yehia, A.H.; Wahba, K.A.; Ali, AE.G. Efficacy and safety of post-cesarean section incisional infiltration with lidocaine and epinephrine versus lidocaine alone in reducing postoperative pain: a randomized controlled double-blinded clinical trial. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2016;17:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sarvela, J.; Halonen, P.; Soikkeli, A.; Korttila, K. A double-blinded, randomized comparison of intrathecal and epidural morphine for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2002;95:436–40. [CrossRef]

- Sarvela, P.J.; Halonen, P.M.; Soikkeli, A.I.; Kainu, J.P.; Korttila, K.T. Ondansetron and tropisetron do not prevent intraspinal morphine- and fentanyl-induced pruritus in elective cesarean delivery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006;50:239–44. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).