1. Introduction

A Cesarean Section (CS) is a fetal delivery through a uterine incision and an open abdominal incision (laparotomy) [

1]. World Health Organization (WHO); data indicates that over 18 million cesarean sections are performed annually worldwide. A cesarean percentage of between five percent and fifteen percent is recommended by the WHO a rate below 5% suggests that access to medical technology is limited. The WHO also estimated the prevalence of CS by area, with thirty-six percent in the United States, twenty-three percent in Europe, nine percent in Asia, and four percent in Africa [

2,

3,

4].

The prevalence of post-CS pain is still significant, ranging from 25.5 to 80%, despite improvements in our understanding of the pathogenesis of pain and the development of various analgesic medications and techniques [

5]. Postoperative pain is transitory, inflammatory in nature, and subsides quickly, usually, it takes two to four days following major abdominal surgery and patients feel moderate to severe pain that results from peripheral tissue damage caused by surgery [

6].

According to a study by Hussein et al., 89.8% of pain after CS patients is modest to severe. The duration of surgery, the type of anesthetic used, and the type of analgesics used were all highly associated with the amount of post-cesarean pain [

7]. The percentage of moderate-to-severe pain after CS is 78.4% to 92%, according to another study done in the US, Europe, and Asia. This study suggests that the discrepancy could be caused by barriers in patients' and healthcare providers' attitudes and levels of education regarding the usage of analgesics, as well as the absence of appropriate pain management services [

8].

Pain following CS has been managed with various postoperative pain management approaches over the years, however, none of them is without adverse effects [

5,

9,

10]. Wound infiltration is a low-cost, simple procedure with a good safety margin that has been employed in resource-limited areas as a multimodal analgesic strategy to treat postoperative pain with varied levels of analgesic effectiveness, various published research revealed inconsistent results in lowering postoperative opioid demand and pain severity [

11]. Postoperative analgesia could be effectively attained with the usage of longer-duration local anesthetic agents, like bupivacaine, given to the skin beneath the skin or on both sides of the surgical site [

12].

Tramadol is 2-(dimethyl amino)-methyl)-1-(3ʳ-methoxyphenyl) compound and primarily acting on the central nervous system, its mild agonistic effects on the opioid receptor, its ability to block the absorption of norepheniprne and serotonin (5-HT) in the descending inhibitory pain pathways, and its ability to stimulate the release of 5-HT are at least three different processes by which it exerts its analgesic effects. Research has revealed that tramadol has certain local anesthetic properties when it is injected into peripheral nerves [

13,

14].

The effectiveness of a mixture of bupivacaine with tramadol wound infiltration in lowering the requirement for postoperative opioids and postoperative pain scores has been the subject of conflicting research [

15,

16]. Therefore, this study aims to compare the analgesic effectiveness of wound site infiltration with bupivacaine versus a mixture of bupivacaine with tramadol for postoperative pain management among pregnant women who underwent cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

We have conducted a parallel, double-blind, superiority-randomized controlled trial study at Dilla University Referral Hospital that follows the ethical standards stated in the Declaration of Helsinki and the consolidated standards of reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines [

17]. The participants were randomly assigned to either bupivacaine or a mixture of bupivacaine with tramadol group. The trial registration number is

PACTR202310525672884 (13/10/2023).

2.2. Definitions of the Outcome

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS): is a reliable method for measuring pain intensity that entails requesting a patient to rate her severity of pain on an eleven-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the greatest possible pain.

Total analgesic consumption: The overall amount of analgesic drugs in milligrams(mg) consumed in the first twenty-four hours following the surgery.

VAS (Visual analog Scale): This is a pain rating scale; the scores are derived from patient-reported valuations of symptoms that are recorded at 1 point along a 10 cm line that shows a range between the 2 edges of the scale, which are "no pain" and "worst pain."

Time to first analgesic request: is the time, measured in minutes, between the time the end of surgery and the patient needs analgesics.

2.3. Study Participants

The study was conducted in Dilla University Referral Hospital from Oct 01, 2023, to August 01, 2023; pregnant mothers between 15 and 49 undergoing spinal anesthesia were included in the study. We excluded parturients using alcohol, parturients diagnosed with chronic pain, pregnant mothers with systemic diseases like renal impairment, chronic hepatic disease, respiratory disease, and heart disease, morbidly obese patients (BMI >40kg/m2), spinal anesthesia with adjuvants, operation other than the lower uterine segment incision, pregnant mothers taking opioids preoperatively.

2.4. Randomization, Blinding, and Allocation Concealment

The parturients were randomly allocated to take bupivacaine or a combination of bupivacaine with tramadol after fulfilling the inclusion criteria. The process of simple randomization involved selecting a level from a closed envelope having either B or BT, where B represents the bupivacaine group and BT denotes a combination of the bupivacaine with tramadol groups. A 1:1 ratio of a randomly generated number by the computer was employed. The patients and data collectors were blinded, and the anesthetist in charge who was not part of the study prepared the medications. A sealed, sequentially labeled envelope was used to verify allocation concealment.

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

Based on a prior Indian study, which demonstrated that wound infiltration with a combination of tramadol and bupivacaine extends the painless period, the sample size was determined by selecting analgesic consumption (N1 = 30, µ1 = 386.17, SD1 = 233.84, for a group consisting of bupivacaine and tramadol, and N2 = 30, µ2 = 192.50, SD2 = 134.77 for bupivacaine alone) [

18]. A further 10% was added to the enrollment to account for possible dropout, assuming the balanced design, by utilizing alpha 0.05, effect size 0.4525, power 90%, and sample size determined using power analysis with G power software version 3.1.9.7 to be 53. With 30 people in both groups, the sample size increased to 60 in total.

2.6. Anesthetic Management and Surgery

The night before the procedure, a pre-anesthetic evaluation was completed, and informed consent was obtained. Before spinal anesthesia was administered on the morning of the procedure, parturients were given 200 mg IV cimetidine and 0.1 mg/kg IV dexamethasone 30 minutes before surgery. The non-invasive blood pressure, pulse-oximetry, and electrocardiography (ECG) monitors were attached and recorded. Before spinal anesthesia, 10 ml/kg of isotonic fluid was preloaded into all parturients.

Following spinal anesthesia, the patient's hemodynamics (SPO

2, HR, ECG, and BP) were monitored right away. Every ten minutes, measurements and records of the patient's hemodynamics (SPO2, HR, ECG, and BP) were made and the grade of intraoperative shivering was recorded. The moment the infant was delivered, Uterotonic medications such as misoprostol (400–600µg sublingual) or oxytocin (10 IU IM; infusion 0.04-0.125 IU/min) were administered [

19]. Blood loss, blood transfusions, intraoperative fluid requirements, and complications such as bradycardia, hypotension, nausea, and vomiting were all documented.

When systolic blood pressure (SBP) falls greater than 20% from the starting point, it is referred to as hypotension. Intravenous fluid is used to treat this condition; if it persists after fluid administration, a vasopressor (adrenaline 0.01µg/kg) is used; and atropine (0.02µg/kg) is used to treat heart rates that are less than 60 beats per minute. The method used to grade shivering was the Bedside Shivering Assessment Score (BSAS). Patients received IV tramadol 0.5 mg/kg if they had a shivering grade of three or above [

20].

Depending on the patient's needs, oxygen was given via a nasal prong at a flow rate of two to three liters per minute both during and after surgery. Following the surgery, the last vital sign was documented, and the wound site was infiltrated with 0.7 mg/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine diluted to 20 ml for group B. The BT group received a mixture of 0.7 mg/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine and 2 mg/kg of tramadol diluted to 20 milliliters by the obstetrician [

18]. A 5-point rating system was used to assess postoperative nausea and vomiting, and protocol-compliant care was given to any problems. Using an NRS scale for 24 hours at T2, T6, T12, T18, and T24 hours-where T is the time-the severity of postoperative pain was assessed.

2.7. Data Collection

Data from parturients and clinical charts of individuals who had cesarean sections under intrathecal anesthesia were gathered for the study using standardized questionnaires. The NRS was used to evaluate the severity of pain at five different time points: T2, T6, T12, T18, and T24, where T stands for time. Among the clinical outcomes evaluated were the incidence of PONV, the severity of postoperative pain, the occurrence of shivering, and the first analgesic required time.

2.8. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the severity of pain at 2hr, 6hr, 12hr, 18hr, and 24 hours. The secondary outcomes were total analgesia consumption, first analgesia request time, incidence of shivering, and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The data has been entered into the Epi-data program version 4.6 and analyzed with SPSS version 27. The Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram were used to check the normality of the data. Levene's test was used to determine the homogeneity of variance. Welch's t-test was performed for Levene's test for those data that violate assumptions. The Box plot and Whisker were used to check outliers. Independent sample t-tests were used for parametric and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric ones. Chi-square and Fisher's exact test were used for parametric and non-parametric categorical variables respectively. P values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant. A normally distributed data was shown as mean ± SD. The non-normally distributed numerical data were shown using the median and interquartile range, and the categorical data were represented using percentages (%).

The 2nd, 6th, 12th, 18th, and 24th-hour pain severity was analyzed using a mixed linear model and a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE). A General Estimating Equation (GEE) was run to compare the difference in pain severity with a numerical rating scale (NRS) within the study groups (Bupivacaine versus a comparison of Bupivacaine and tramadol). The difference was expressed with statistical significance, odds ratio, and confidence interval about the first hour. A mixed linear model was run to analyze the continuous repeated measurements (visual analog scale) to investigate the mean pain severity score between groups across time points during follow-up. We followed the modified intention-to-treat analysis principle; only subjects who were randomized and who received all the interventions were included in the final analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Preoperative Characteristics

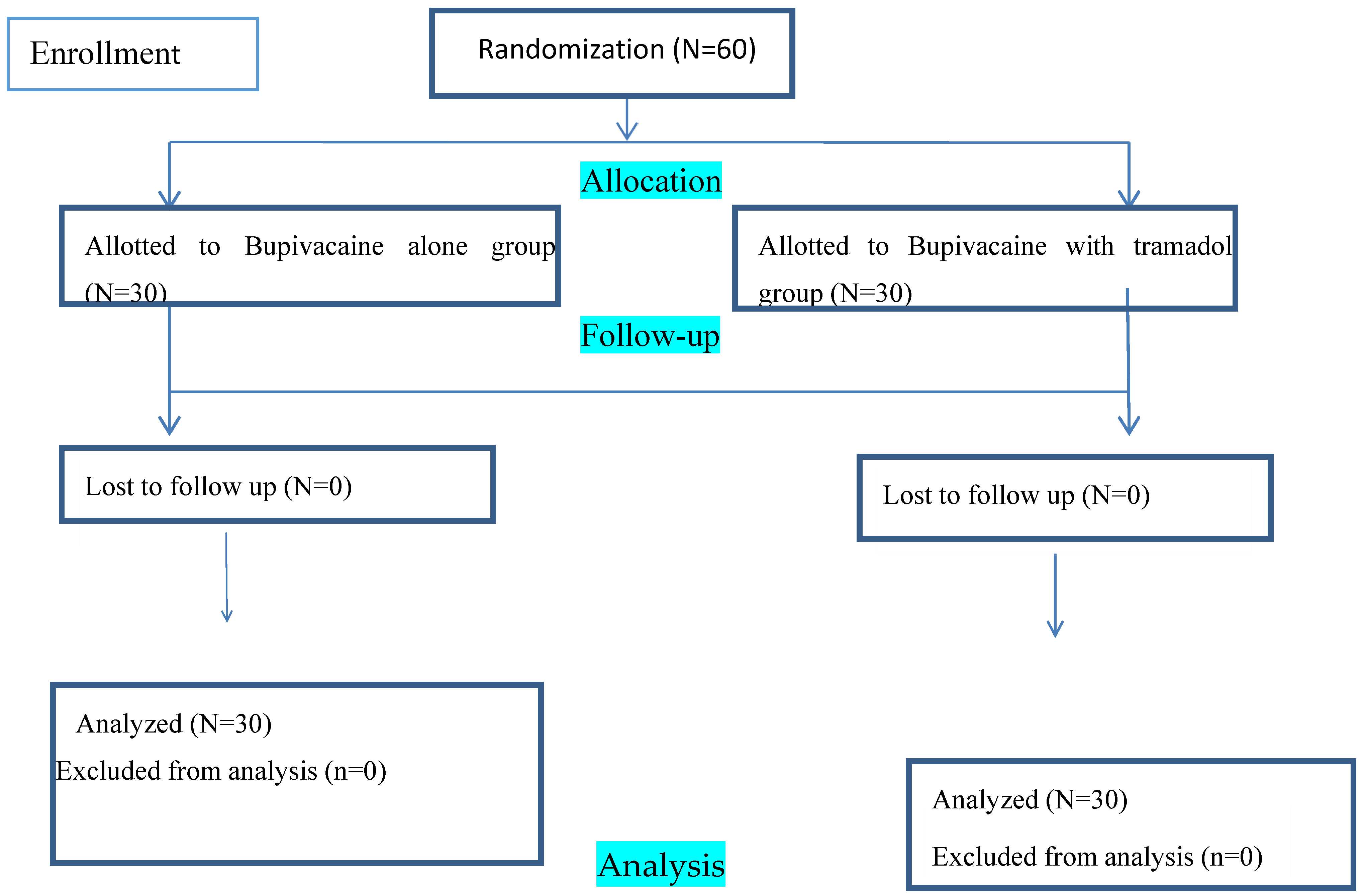

In all, 60 parturients finished the follow-up and analysis during the study period, and there were no occurrences of dropout (

Figure 1). A P-value of more than 0.05 indicates that the groups' perioperative and demographic features are similar for the study subject. Previous CS scar 13(21.67) in the Bupivacaine group and 15(25) in the Bupivacaine with tramadol group was the most common reason for parturients receiving CS, followed by fetal macrosomia 7(11.67) in the Bupivacaine group and 5(8.33) in the Bupivacaine with tramadol group respectively.

Table 1

3.2. Intraoperative Characteristics

At the 6th hour postoperatively, the time the uterus stayed outside the abdomen and pain severity was statistically significant (8.22±1.767), (P=0.027). With a P-value of greater than 0.05, all other intraoperative variables are comparable between the groups. The majority of the procedures were done with a sensory level T6 block, with 15(25) in the group treated with bupivacaine and 17(28.3) in the group treated with bupivacaine plus tramadol.

Table 2

Pain severity

The severity of pain in the 6th hour is 6 times higher in the B group in comparison to the BT Group (OR=6.289, CI=2.097-18.858, P= 0.001). The severity of pain in the 12th hour is 4 times the likelihood in the B group in comparison to the BT Group (OR=4.313, CI=1.746-10.654, P= 0.002). The severity of pain in the 18th hour is 6 times the likelihood in the B group in comparison to the BT Group (OR=6.289, CI=2.328-16.987, P= 0.0001).

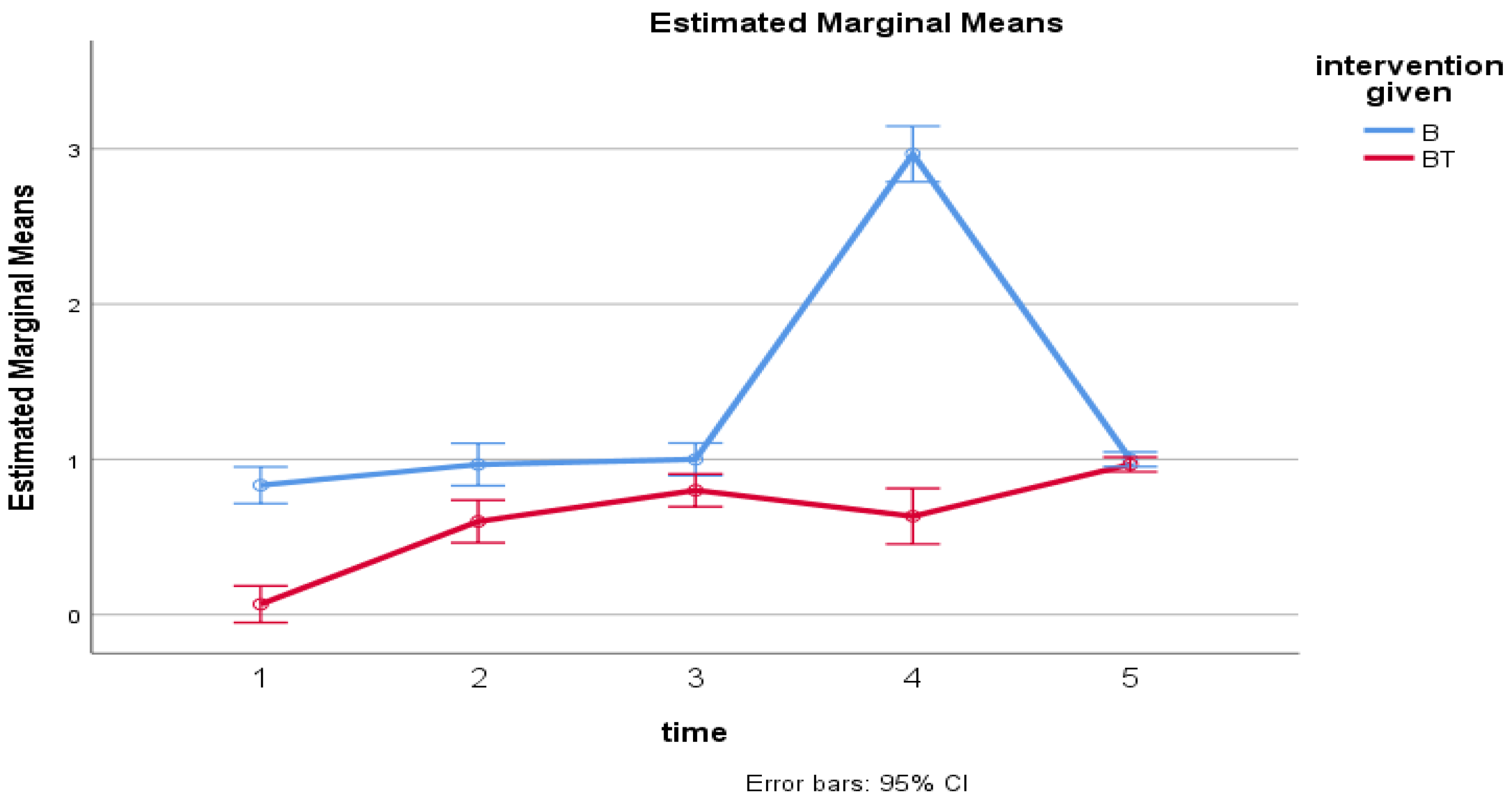

Where= B, Bupivacaine group; BT, Bupivacaine and Tramadol group; 1=follow-up of pain severity @2hr, 2= follow-up of pain severity @6hr, 3= follow-up of pain severity @12hr, 4= follow-up of pain severity @18hr and 5= follow-up of pain severity @24hr (x-axis) and the estimated marginal mean of pain severity (y-axis).

There is a significant difference across the five time points F (3,165) =139.8, P<0.001 and there is also a significant difference between groups on pain severity F (1, 58)=268, P<0.001. There was also a significant difference in interaction between time and group F (3, 165) =121, P<0.001. However, there was no significant difference in 2hrs and 24rs follow-up time between groups. Whereas, the mean pain score increased over time between groups with a significant increment at 18 hours in the control group (B) as compared to the intervention group(BT). (

Figure 2)

Analgesia consumption

The mean tramadol consumption was lower in a mixture of tramadol and bupivacaine group (BT) (140.00+48.066 mg) than bupivacaine group (175.00+34.114 mg) with a statistically significant mean difference(MD) of 10.761 (95% CI, 13.459 to 56.541), t (58) = 3.252, P= 0.002, (d=0.839). There was no significant difference in mean diclofenac consumption between the two groups in a combination of tramadol and bupivacaine group (52.50+48.844) than bupivacaine alone group (57.50+46.955), (P=0.688), (d=0.104).

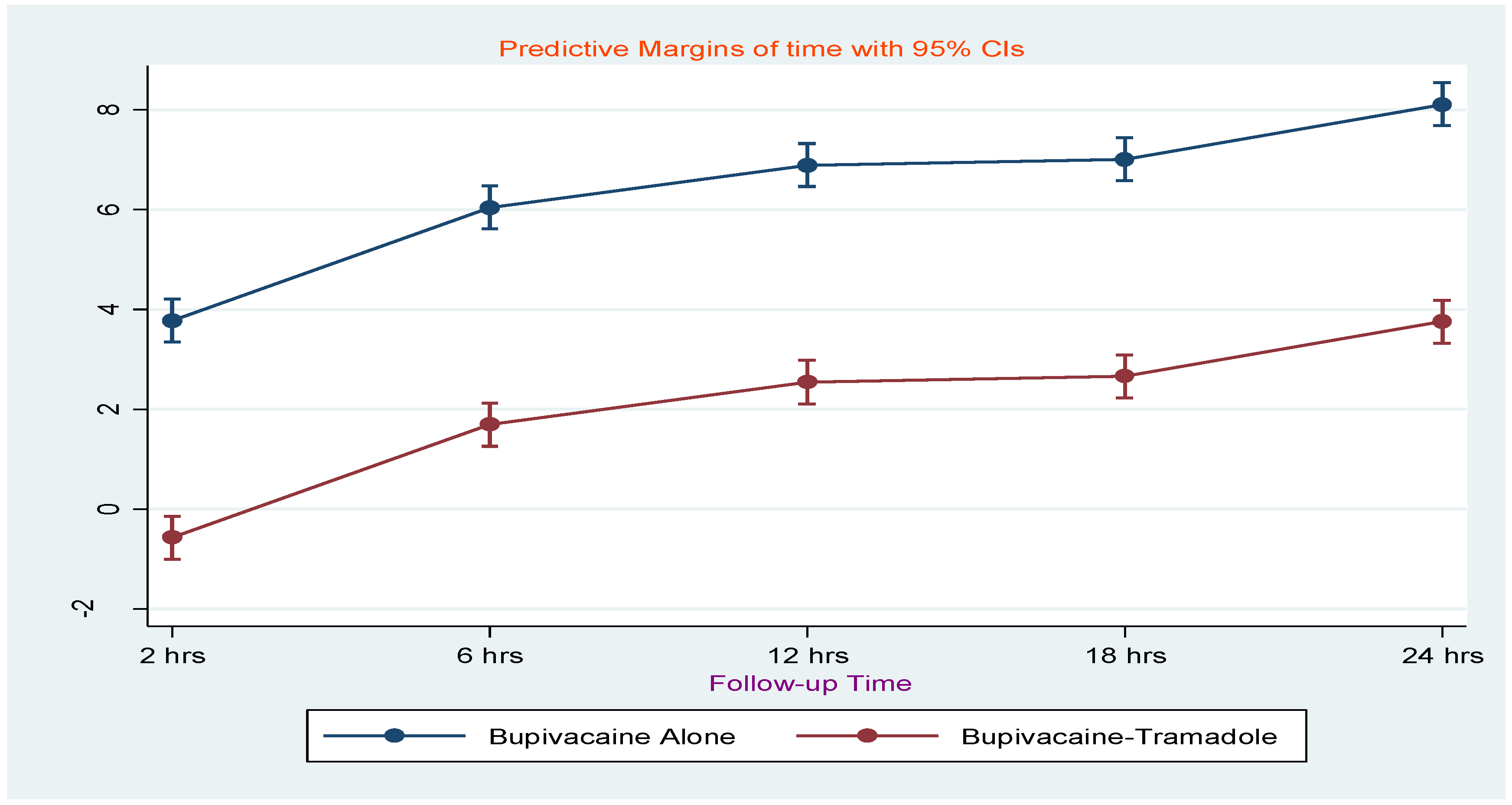

First analgesia request time

The mean first analgesia request time in minutes was

greater in a mixture of tramadol and bupivacaine group, (Mean+ SD) (367.33+50.099

min) than bupivacaine group (216.33+68.744 min) with a statistically

significant mean difference of 15.530 (95% CI, -182.087 to -119.913), t (58)

= 5.6553, P= 0.001. Besides, the marginal means showed that the mean Visual

Analog Scale score increases progressively over time, while at 2 hrs the pain

severity was reduced by (0.58±0.21, 95% CI=-1.00 to -0.144) in the bupivacaine

with tramadol group. Figure 3

There was no difference between the two groups in terms of the incidence of intraoperative shivering and postoperative shivering.

4. Discussion

In our study, the combination of tramadol and bupivacaine group showed a substantial reduction in pain severity as measured by NRS compared to the bupivacaine alone group. Six hours later, the B group had six times more severe pain than the BT group (OR=6.289, CI=2.097-18.858, P=0.001). Compared to the BT Group, the B group experienced four times more severe pain at the 12-hour mark (OR=4.313, CI=1.746-10.654, P=0.002). In the eighteenth hour, the B group experienced six times more severe pain than the BT Group (OR=6.289, CI=2.328-16.987 P=0.0001).

Similar to the findings of Sachidananda et al., our study showed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0484) between the mean (±SD) postoperative pain score of the treatment group at 6 and 12 hours after surgery (2.60 ± 0.97) and that of the control group. However, the mean (±SD) postoperative pain score at 18 and 24 hours was 2.07 ± 0.64 and 2.07 ± 0.37 in the groups receiving bupivacaine and those receiving a combination of bupivacaine and tramadol, respectively, with P = 0.8825(18). The possible explanation for these discrepancies may be the difference in the study population.

According to another study by Gebremedhin et al., which involved 120 patients undergoing lower abdominal surgery, the median (IQR) of pain severity (NRS) score was 0.0 (0-0) until 12 hours, and 1 (0–5) and 3 (1–5) at 18 and 24 hours in the local wound infiltration (LWI) groups with bupivacaine and tramadol (BT) as opposed to LWI bupivacaine alone (B) in the post-anesthesia care unit and ward. There was a notable difference in pain severity between the BT and B at the twelve-, eight, and twenty-four-hour marks (p < 0.001) [44]. However, in our study, there is also a significant difference at 2hr. The discrepancies may be due to a difference in study population, study design, and other confounding variables.

In contrast to our study, the number of patients in the Kumar et al. trial who reported a VAS pain level of >4 did not demonstrate any significant differences between group B and group BT during rest or movement at any recorded time interval during the study period. The estimated postoperative pain-free period was comparable (P=0.01) for the two groups. The first rescue periods for both groups and the total amount of rescue analgesic required were comparable (P>0.05) [22]. The discrepancies may be due to the difference in the study population, sample size, and drug dosage used.

Our study found a statistically significant association (P=0.027) between the length of time the uterus was outside and postoperative pain at 6 hours. At 2 hours, 12 hours, 18 hours, and 24 hours, it was not noteworthy, though. Nafisi's study supports our findings, demonstrating that visceral pain scores were considerably greater in the exteriorization group on the first and second nights compared to the in situ group (66.7 vs. 43.5 on the first night; P < 0.001) and 44.6 vs. 23.9 on the second night (P < 0.001) [23]. Another study by Tan et al. shows that at six hours, exteriorization was linked to a higher incidence of postoperative pain (rated > 5/10) (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.31 to 2.03; I2 = 0%). Comparing in situ repair to 24 hours later, there was no difference in pain levels or the requirement for rescue analgesia (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 0.89 to 6.90; I2 = 94%) [24].

A meta-analysis by Zaphiratos et al., in contrast to our results, indicates that there was no statistically significant difference in terms of intraoperative pain (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.86 to 2.71), vomiting (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.35), or nausea (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.34). A more rapid recovery of bowel function was associated with the repair in situ (MD, 3.09 hours; 95% confidence interval, 2.21 to 3.97) [25]. The discrepancies may be due to the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis and heterogeneity among included studies.

In this study, we found that the mean tramadol consumption in the mixture of bupivacaine with tramadol group was statistically different (140.00+48.066) than the bupivacaine alone group (175.00+34.114), with a statistically significant mean difference of 10.761 (95% CI, 13.459 to 56.541), t (58) = 3.252, P= 0.002, d=0.839. The mean diclofenac was not statistically significant between the two groups BT= (52.50±48.844), B= (57.50±46.955 (P=0.688), (d=0.104. Additionally, there is no significant difference between the two groups' baseline means for HR, MAP, and SBP.

This finding might be due to that tramadol and bupivacaine may have acted synergistically, which might have provided lower analgesic consumption. The synthetic codeine derivative tramadol is a 4 phenyl piperidine. As a receptor agonist, it is. Serotonergic and 2-adrenergic pathways mediate the non-opioid process. Norepinephrine and hydroxyl tryptamine are blocked from returning from nerve terminals by it. Several researches published recently claim that local anesthetics and anti-inflammatory drugs have anti-neuronal effects [

16].

A cohort study conducted by Zewdu et al.' on the effectiveness of wound infiltration for patients undergoing elective CS in comparison to the placebo group supports our findings, which indicate that the control group's analgesic use of tramadol and diclofenac over the 24-hour postoperative period was considerably greater than that of the WSI group (P-value = 0.014) [

11]. Consistent with our findings, research by Sarwar A., Tasleem S., et al. found that WSI consumed much less tramadol than the placebo group [26]. Additionally, our results are in line with other studies that reported a much higher request for postoperative analgesia in the bupivacaine group as opposed to WSI [

12,27].

In our study, the first analgesic request time in minutes in the local wound infiltration (LWI) with the BT group is more notable than in the B group. A study conducted by Sachidananda et al on elective CS patients comparing wound infiltration with a mixture of tramadol and bupivacaine(BT) versus bupivacaine alone(B) is in line with our results. The mean interval between the first analgesic request following LWI with BT for lower abdominal surgery and 192.50 ± 134.7 min in the LWI BA group (P = 0.0002) was 386.17 ± 233.84 min [

18].

Our study's findings are consistent with one done by Taksakande et al. In Group BT, the first request for analgesia was made in 390.71 ± 243.74 minutes, while in Group B; it was 190.05 ± 130.67 minutes. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0001). The first rescue analgesia dose was required in Group B earlier than in Group BT, and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0001). When comparing Group B and Group BT, Group BT's postoperative analgesia lasted longer (P = 0.0001) [28].

Study strengths and limitations

This study was of high quality, given the double-blinded design; our study has some limitations including the lack of control over confounding variables such as the size of the incision, the time of uterine exteriorization, and the shorter duration of the postoperative follow-up time.

5. Conclusion

This randomized controlled trial reveals wound infiltration with a mixture of Bupivacaine with tramadol (0.7mg/Kg of 0.25% Bupivacaine and 2mg/Kg of tramadol) is an effective than bupivacaine alone group for postoperative pain management among parturients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. Furthermore, the application of a Bupivacaine and tramadol mixture to the wound site results in a prolonged period of painlessness and a prolonged duration of analgesia request time, decreasing the overall consumption of opioids.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; MM, SM, and ZA, methodology; SM and HG, software; BD and MM, validation; MK and MM formal analysis MM and, investigation SM and MM, resources and data curation; HM and SA, writing-original draft preparation; MM and SM, writing-review and editing; BD and MM, visualization, supervision, and project administration; MM, SM, and ZA,. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Dilla University has funded this research.

Institutional Review Board statement

This study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dilla University College of Health Sciences and Medicine with a unique protocol number (duirb/029/23-05). This protocol is registered at the Pan African Clinical Trial registry under the identification protocol number PACTR202310525672884. The IRB was informed of the study protocol modification. All IRBs and ethics committees updated participant materials and informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Each patient provided written informed permission after being told of the study's benefits and dangers. The study allowed participants to withdraw at any time, and their rationale for doing so was recorded.

Data Availability Statement

The trial dataset was safely kept on password-protected servers at Dilla University, with strict access controls in place, and the principal researchers had complete access to it. With the establishment of proper data sharing agreements and upon reasonable request, access to the anonymous dataset may be made accessible for external researchers. Any personally identifiable details will be eliminated before data release to keep patientnts confidentiality. Results that remain anonymous will be shared through publishing in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at international conferences. This protocol is registered at the Pan African Clinical Trial registry under the identification protocol number PACTR202310525672884.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully thank everyone who contributed to this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval; CS, Cesarean Section; DBP, Diastolic Blood Pressure; HR, Heart Rate; LA, Local Anesthetics; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; OR, Odds Ratio; PACU, Post Anesthesia Care Unit; SA, Spinal Anesthesia; SBP, Systolic Blood Pressure; SPO2, Peripheral capillary Oxygen Saturation; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WI, Wound Infiltration

References

- Sung S, Mahdy H. Cesarean Section. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls PublishingCopyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2022.

- Wondie AG, Zeleke AA, Yenus H, Tessema GA. Cesarean delivery among women who gave birth in Dessie town hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216344. [CrossRef]

- Alemu WM, Ashagrie HE, Agegnehu AF, Admass BA. Comparing the analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block versus wound infiltration for post-cesarean section pain management: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Surgery Open. 2021;35:100377. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Vega E, Casco S, Chamizo K, Flores-Hernández D, Landini V, Guillén-Florez A. Rising trends of cesarean section worldwide: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2015;3(2):00073. [CrossRef]

- Abate SM, Mergia G, Nega S, Basu B, Tadesse M. Efficacy and safety of wound infiltration modalities for postoperative pain management after cesarean section: a systematic review and network meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):194. [CrossRef]

- Zalon ML. Mild, moderate, and severe pain in patients recovering from major abdominal surgery. Pain management nursing : official journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses. 2014;15(2):e1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hussen I, Worku M, Geleta D, Mahamed AA, Abebe M, Molla W, et al. Post-operative pain and associated factors after cesarean section at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2022;81. [CrossRef]

- Borges NC, Pereira LV. Predictors for Moderate to Severe Acute Postoperative Pain after Cesarean Section. 2016;2016:5783817. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Zhao G, Song G. The Efficacy and Safety of Local Anesthetic Techniques for Postoperative Analgesia After Cesarean Section: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. 2021;14:1559-72. [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian M, Leysi M, Hemmati AA, Mirmohammadkhani M. The effect of low-dose intravenous ketamine on postoperative pain following cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: a randomized clinical trial. Oman medical journal. 2015;30(1):11-6. [CrossRef]

- Zewdu D, Tantu T, Olana M, Teshome D. Effectiveness of wound site infiltration for parturients undergoing elective cesarean section in an Ethiopian hospital: A prospective cohort study. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2021;64:102255. [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye AA, Hofmeyr GJ. Caesarean section wound infiltration with local anaesthesia for postoperative pain relief - any benefit? South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 2010;100(5):313-9. [CrossRef]

- Kaki AM, Al Marakbi W. Post-herniorrhapy infiltration of tramadol versus bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief: a randomized study. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2008;28(3):165-8. [CrossRef]

- Subedi M, Bajaj S, Kumar MS, Yc M. An overview of tramadol and its usage in pain management and future perspective. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019;111:443-51. [CrossRef]

- Sarwar A TS. Effectiveness of Local Bupivacaine Wound Infiltration in Post Operative Pain Relief After Caesarean Section. J Soc Obstet Gynaecol Pak. 2016;6(3):125-8.

- Haliloglu M, Bilgen S, Menda F, Ozcan P, Ozbay L, Tatar S, et al. Analgesic efficacy of wound infiltration with tramadol after cesarean delivery under general anesthesia: Randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(7):816-21. [CrossRef]

- Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan AW, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. Jama. 2022;328(22):2252-64. [CrossRef]

- Sachidananda R, Joshi V, Shaikh S, Umesh G, Mrudula T, Marutheesh M. Comparison of analgesic efficacy of wound infiltration with bupivacaine versus mixture of bupivacaine and tramadol for postoperative pain relief in caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia: A double-blind randomized trial. Journal of Obstetric Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2017;7(2):85-9. [CrossRef]

- Heesen M, Carvalho B, Carvalho JCA, Duvekot JJ, Dyer RA, Lucas DN, et al. International consensus statement on the use of uterotonic agents during caesarean section. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(10):1305-19. [CrossRef]

- Acharya S, and N Dhakal. “Comparison Between Tramadol and Meperidine for Treating Shivering in Patients Undergoing Surgery under Spinal Anaesthesia”. Nepal Medical College Journal. 2020;22(1-2):27-32. [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin TD, Obsa MS, Andebirku AA, Gemechu AD, Haile KE, Zemedkun A. Local wound infiltration with a mixture of tramadol and bupivacaine versus bupivacaine alone in those undergoing lower abdominal surgery: Prospective cohort study, 2020. International Journal of Surgery Open. 2022;44:100508. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Batra YK, Panda NB, Rajeev S, Nagi ON. Tramadol added to bupivacaine does not prolong analgesia of continuous psoas compartment block. Pain Pract. 2009;9(1):43-50. [CrossRef]

- Nafisi S. Influence of uterine exteriorization versus in situ repair on post-Cesarean maternal pain: a randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2007;16(2):135-8. [CrossRef]

- Tan HS, Taylor CR, Sharawi N, Sultana R, Barton KD, Habib AS. Uterine exteriorization versus in situ repair in Cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2022;69(2):216-33. [CrossRef]

- Zaphiratos V, George RB, Boyd JC, Habib AS. Uterine exteriorization compared with in situ repair for Cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(11):1209-20. [CrossRef]

- Aimen Sarwar S. Effectiveness of Local Bupivacaine Wound Infiltration in Post-Operative Pain Relief After Caesarean Section. JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETY OF OBSTETRICIANS AND GYNAECOLOGISTS OF PAKISTAN. 2016;6(3):125-8.

- Krishnegowda S, Pujari V, Doddagavanahalli S, Bevinaguddaiah Y, Parate L. A randomized control trial on the efficacy of bilateral ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric nerve block and local infiltration for post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Journal of Obstetric Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2020;10:32. [CrossRef]

- Taksakande K, Movva H, Rallabandi S, Nasal R, Jhadav J, Wankhede P. To compare the analgesic efficacy of wound infiltration with bupivacaine and mixture of bupivacaine and tramadol for postoperative pain relief in cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. Journal of Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences University. 2021;16(4):724-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).