Introduction

Mobile genetic elements, known as transposable elements (TEs), comprise substantial portions of eukaryotic genomes, accounting for over 50% of genomic sequences. Although historically dismissed as genomic "junk," these sequences have gained recognition for their functional contribution to genomic organization and evolutionary processes [

1,

2]. In our previous work, we proposed that transposable elements may function as structural anchors that facilitate and control chromatin folding [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Our previous analyses of transposable element distributions around chromatin contact points suggested a potential role for these repetitive sequences in mediating chromatin interactions [

11].

The development of high-resolution chromatin conformation capture methods, including Hi-C and Micro-C technologies, now enables researchers to map chromatin contacts with high precision [

12], providing insights into the spatial organization of the chromosomes. Earlier, we proposed that identical repetitive elements might adhere to each other, thereby serving as sequence-specific reversible fasteners that guide chromatin folding [

11]. Unlike complementary pairing of single DNA strands into a double helix in head-to-tail orientation, this proposed homological coupling of transposable elements was proposed to occur on a larger scale - by reversibly pairing identical DNA duplexes in head-to-head orientation [

11]. Therefore, we reasoned that if the homological coupling hypothesis is true, we should observe sequence homology between genomic regions brought together at chromatin contact points in chromatin conformation assays. Because transposable elements represent the primary source of sequence homology in the genome, they would likely mediate such homology-based interactions [

11].

In this study, we directly test for sequence homology between chromatin fibers at contact points using public long-read chromatin conformation capture data. Although many more short-read datasets are available, long reads were selected since they should include more of the contacts located in the repetitive regions of the genome. To test whether homological coupling occurs, we measured the sequence homology between pairs of genomic regions that were brought together and ligated during chromatin conformation capture.

Methods

Source Data and Initial Processing

Since we were interested in the role of transposable elements in sequence specificity of chromatin folding, we used CiFi (Chromatin interaction by Fiber-seq) data from McGinty [

13]. They performed chromatin conformation capture on GM12878 lymphoblastoid cells cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde to preserve in vivo chromatin contacts. The CiFi protocol utilized DpnII restriction enzyme digestion, followed by proximity ligation, to join DNA fragments that were spatially close in the nucleus, thereby creating multi-contact concatemers that capture chromatin interactions. After ligation and reverse cross-linking, the DNA underwent PCR amplification using high-fidelity polymerase to enrich for intact molecules, followed by PacBio HiFi sequencing to produce long reads (median 8-10 kb) containing multiple ligated chromatin fragments. Each CiFi read represents multiple chromatin contacts, where ligation junctions between non-contiguous genomic regions indicate chromatin contacts mediated by protein complexes and DNA looping. We downloaded the PacBio HiFi BAM file (GM12878_DpnII_CiFi.HiFi_v3.0_hifi_reads.bam, 56.8GB) containing 12 million CiFi reads from

https://bioshare.bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/bioshare/download/rlc692m7tk5cibb/ciFi/GM12878_CiFi_v3/. We extracted FASTQ sequences from the BAM file using samtools (v1.9) with the command pipeline 'samtools view | samtools fastq'. Reads were aligned to the masked human reference genome (hg38_masked) using minimap2 (v2.17) with parameters optimized for PacBio HiFi data (-x map-hifi --secondary=yes -N 1 --MD). The aligned BAM files were sorted by read name using samtools sort -n. We did not collapse duplicated or overlapping reads. From the total list of reads, we extracted multi-anchor candidate reads identified using stringent criteria: the candidate read should have 2 anchors in a positive DNA strand, the anchors should be on different chromosomes, or separated by over 10 kb on a single chromosome, primary/secondary alignment score ratio ≥2.0, MAPQ=60, and reported error rate <1%.

Ligation Point Detection

We distinguish between ligation junctions (the joining point of two DNA fragments within a sequenced read) and ligation points (the corresponding genomic coordinates where these fragments originated). To identify ligation points, we first detected junctions in the reads by aligning each read anchor to its genomic counterpart in an unmasked genome. Since the anchors were initially detected using the masked version of the genome, they represented unique and low-copy-number sequences. We then expanded these unique sequence alignments into the repetitive parts of the genome by gradually extending the homology area from each anchor. At junctions, this homology sharply dropped. We identified these homology drop sites using a sliding window approach (50 bp window, 10 bp step). Drops and rises were defined as transitions from >83% to <55% homology within a 35bp distance. Only transitions located within 35bp of DpnII restriction sites were retained. Ligation points were identified as the DpnII site coordinates located where homology expansions from two anchors converged, defined by a <50bp distance between the homology drop from the left anchor and the homology rise from the right anchor.

Results

Ligation Junction Analysis

We are publishing elsewhere a hypothetical model of sequence-specific pairing of chromosomal fragments at contact points, proposed to occur via sequence homology. Since sequence homology is dominated by transposons in the genome, it is essential to examine chromatin conformation data using long reads. We attempted to use the published nanopore data, but it had an excessively high error rate. We found the one by PacBio CiFi (McGinty et al., 2025).

Since it was important to map precisely contact points, we could not use traditional methods, which have too low resolution in genomic coordinates of exact contact points. Typically, restriction enzyme-based chromatin conformation assays treat every restriction site as a potential ligation point and computationally split the read at every restriction site as if they were digested and ligated. However, for our task of testing in-pair homology, we needed to exclude all non-digested and therefore non-ligated restriction sites. Therefore, we inspected them for genomic sequence continuity and found that a high fraction, 20-50%, were incomplete restriction digests likely due to protection by cross-linked protein.

We developed a sequence analysis method that mapped the ligation junction points with greater accuracy. That method required a combination of restriction site presence and that the adjacent sequences came from distant genomic loci. To explain this method and the subsequent analysis of results, we need to describe the events in sufficient detail.

We used the read sequence data from the chromatin conformation mapping assay by McGinty et al. [

13].

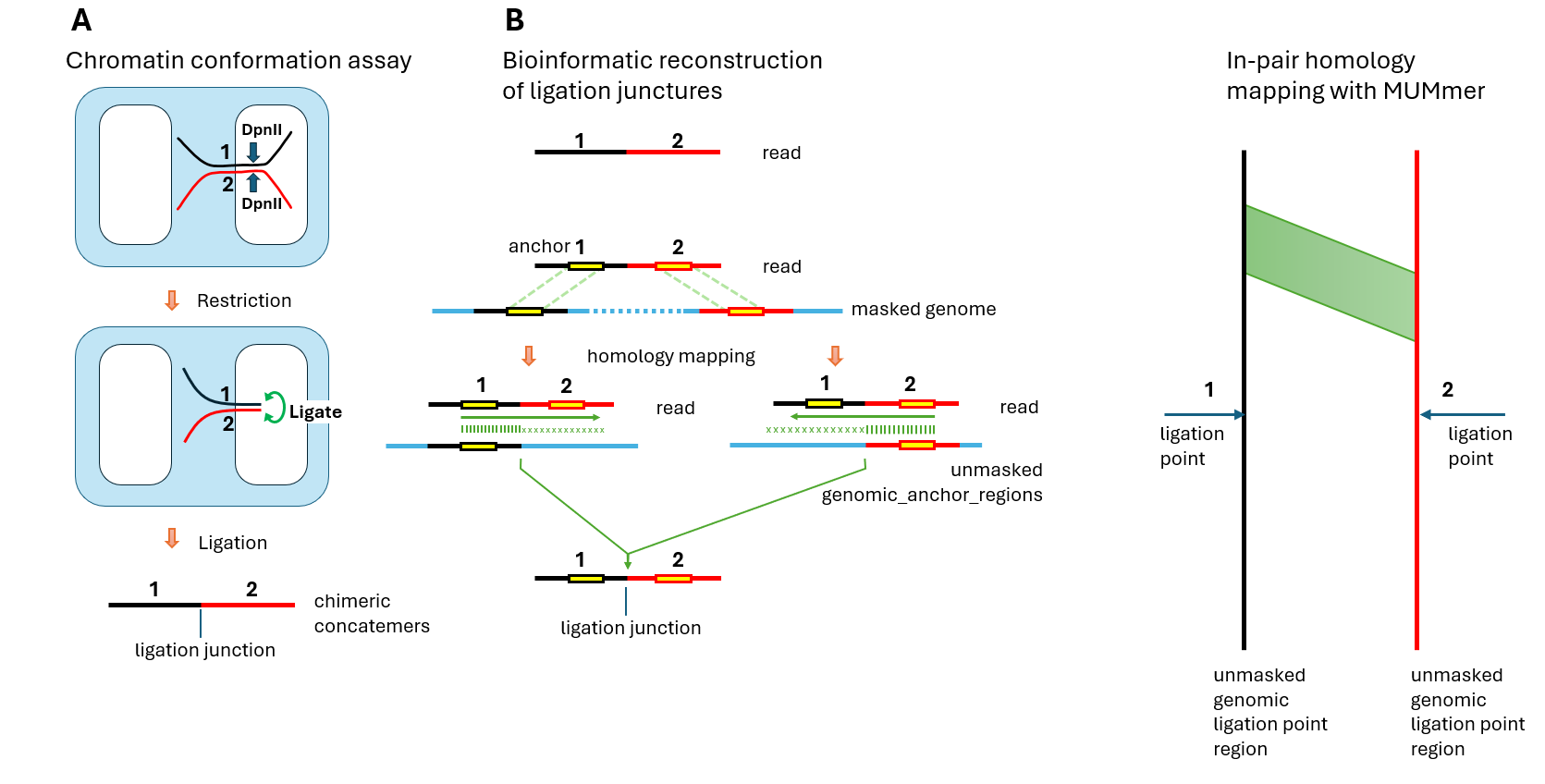

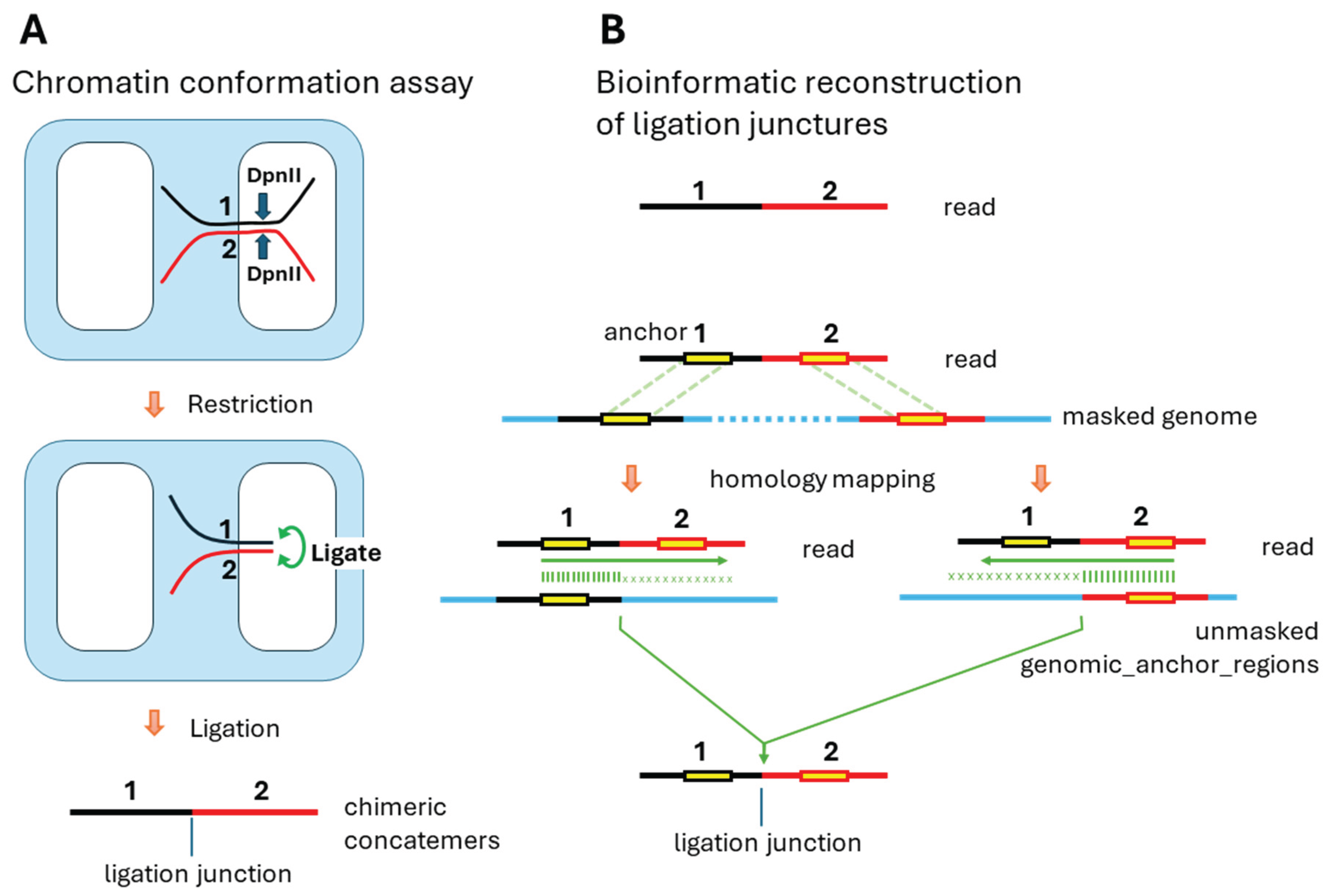

In the chromatin conformation mapping assay by McGinty et al, cells from the GM12878 lymphoblastoid cell line were fixed with formaldehyde to capture chromatin contacts. Cells were permeabilized with nonionic detergent, and chromatin was digested with DpnII restriction enzyme in situ within the permeabilized nuclei. During this process, DNA fragments that were in spatial proximity due to chromatin folding remained tethered by crosslinked proteins (

Figure 1A). The restriction enzyme created free DNA ends that underwent proximity ligation while still held in place by the protein-mediated contacts. After ligation, crosslinks were reversed and the resulting chimeric concatemers were sequenced.

The computational challenge lay in reconstructing the original genomic positions from the sequenced reads. In the bioinformatic analysis, we were starting with only the read sequence containing ligated fragments (

Figure 1B, top). The read contained a ligation junction where two originally distant genomic regions were joined. To identify the precise ligation points in the genome, we first mapped the read segments flanking the junction to a masked genome using Minimap2, producing anchors that mapped to discontinuous genomic regions. Masking of the genome was necessary to exclude high-copy-number repeats. Only uniquely mapping anchors were retained. However, we were interested in mapping the ligation points that were located in either unique and low-copy-number regions or highly repetitive parts of the genome. Therefore, the obtained genomic anchor positions were then expanded in both directions to obtain larger (20 kb) genomic regions containing these anchors (genomic_anchor_regions). Then we measured the homology of the read to each of the corresponding genomic_anchor_region, expanding each anchor and allowing for small indels. Indels were allowed to compensate for natural variations in the studied cell line compared to the reference genome. For the majority of reads, we observed that the homology, as expected, sharply dropped at some of the DpnII restriction sites. This was true for about 50-80% of DpnII sites, likely because other sites were protected by crosslinked proteins. We identified ligation junctions by requiring two criteria: (1) presence of a DpnII restriction site at the junction in the read, and (2) the read sequences immediately adjacent to the ligation junction had to map to genomic loci separated by over 10kb. The identified junction in the read corresponded to two ligation points (LP1 and LP2) in the genome—positions where restriction occurred and ligation later joined the fragments. As shown in

Figure 1, ligation points do not always correspond exactly to the contact areas. Unlike in Micro-C, where the cuts occur very close, under 20 bases from the crosslinked protein, in the DpnII-based Ci-Fi assay, precision is defined by the actual distance between DpnII digests, allowing contact areas to be located anywhere within approximately 0.5 kb in either direction from the actual ligation point. Although the precision of the exact location of the contact areas was limited to ±0.5 Kb, our method of exact mapping of ligation points was necessary to exclude DpnII sites which were not digested due to crosslinking and therefore did not ligate. This way, accurate locations of ligation points were identified.

From 12 million PacBio CiFi reads, we identified 6,055 ligation points, with 4,924 (81.3%) representing cis interactions (both alignments on the same chromosome) and 1,131 (18.7%) representing trans interactions (alignments on different chromosomes). This cis/trans ratio of 4.4:1 confirms successful Hi-C chemistry and appropriate capture of chromatin contacts.

In-Pair Homology Measurement

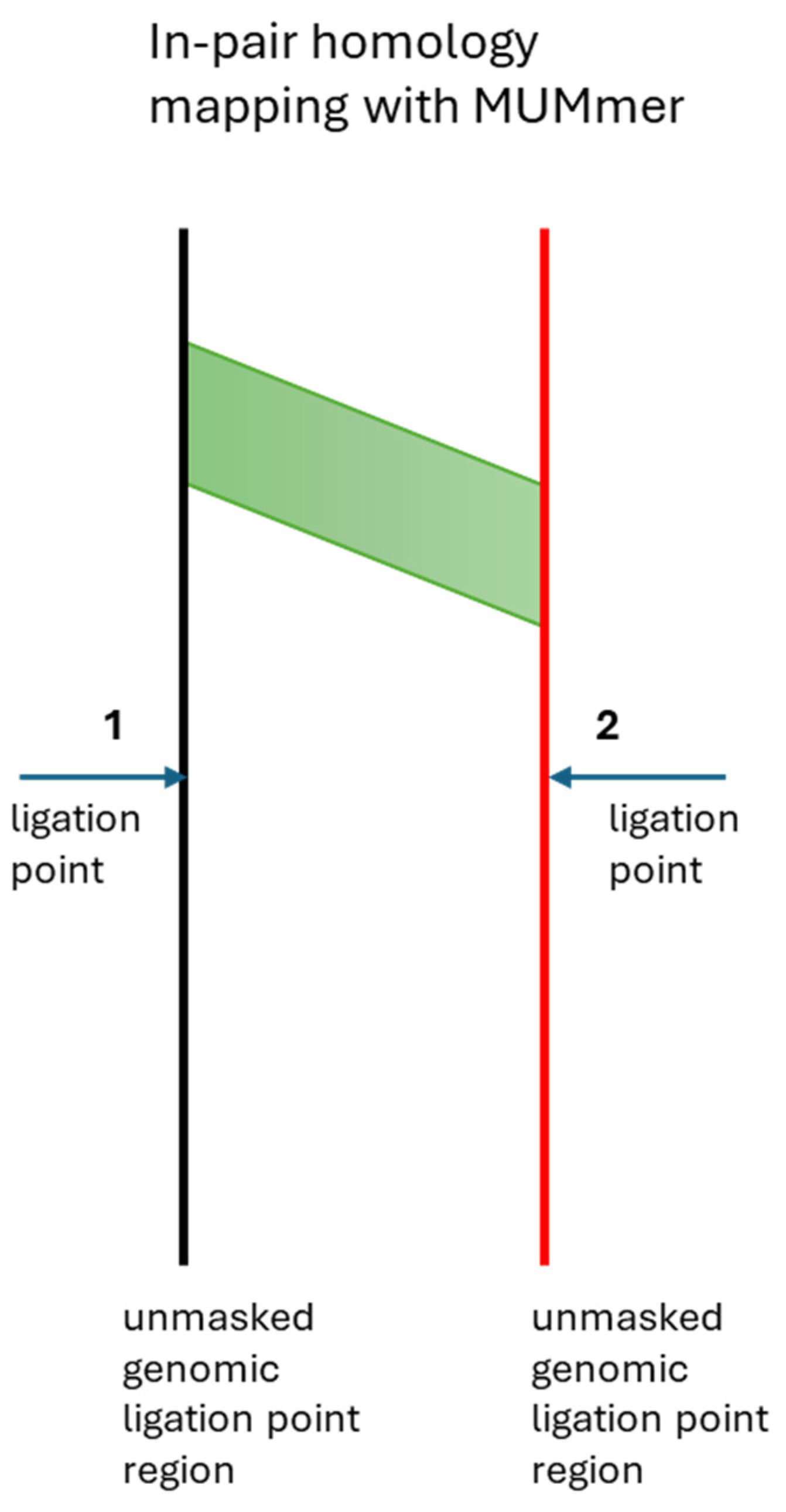

Each ligation event brings together members of a pair of genomic regions,

Figure 2. We analyzed in-pair sequence homology between genomic regions brought together at 6,055 ligation junctions. Using MUMmer to map homology across 80kb windows, we compared sequences from actual ligation point pairs against randomly swapped control pairs. Essentially, we compared the in-pair homology to homology of a member of a pair to a non-member of a pair.

Volcano-Shaped In-Pair Homology Enrichment

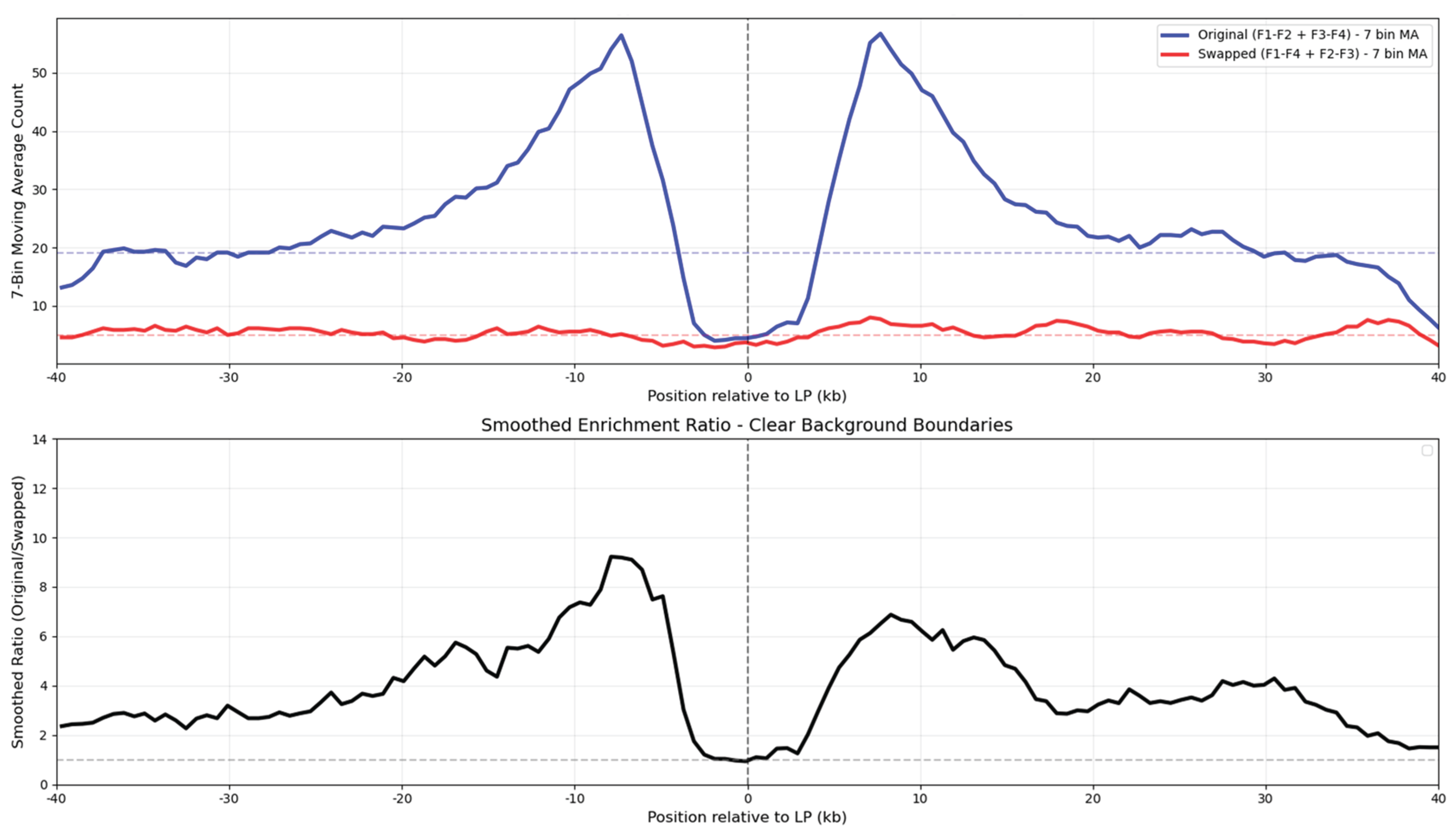

The homology analysis revealed a volcano-shaped enrichment profile centered on the genomic locations of the ligation points, as shown in

Figure 3. The original pairs showed substantially higher homology density than the swapped controls, with enrichment varying strongly by position. Peak enrichment exceeded 8-fold at approximately 7kb on either side of the ligation point, while dropping to near-background levels directly at the ligation point itself, creating a distinctive ~10 kb central depletion basin.

The volcano-shaped in-pair homology enrichment graph represents and average of 6K analyzed ligation points, as shown in

Figure 3. The analysis didn't require the homologies to be located at equal distances from the ligation point, as shown in

Figure 2. The analysis revealed significant homology enrichment between ligated genomic regions compared to controls. In-pair homology was substantially higher than with outside-of-the-pair random reads. Although contact areas are of primary biological interest, while ligation points are secondary, we can only identify ligation points and reasonably assume that contact areas can coincide or be shifted up to approximately 0.5 kb in either direction from the genomic ligation points.

The volcano shape of the distribution curve with the homology depletion basin at the center presents an intriguing phenomenon. Most likely, this is an overlap of a wider positive peak with a narrower antipeak or basin. We suggest a couple of possible explanations: (1) Since the ligation points were detected based on the alignment to the masked genome, the repetitive elements were excluded, creating systematic bias against repeats. Yet, the plotted in-pair homologies between ligated genomic regions are most likely created by the repetitive elements. So the depletion of the repetitive elements near the ligation points by the computational method should have created a homology density basin near the ligation point. Unfortunately, this negative selection can not be avoided, since locating the ligation points requires first finding unique anchors. So the first explanation is very likely. (2) The volcano pattern may reflect genuine chromatin architecture where homology-mediated contacts occur at specific distances from restriction sites, with DNA loops bringing distant homologous regions into proximity. The 10 kb basin may suggest an underlying structural principle in how chromatin fibers organize around contact points, or vice versa, how sequence homology drives chromatin contacts. We don't exclude other possible explanations. In summary, the basin may arise from measurement selectivity, intrinsic biological organization, or other undiscovered mechanisms.

Discussion

We observed an 8-fold in-pair homology enrichment between chromatin fibers at specific distances from ligation points. This pattern suggests that sequence similarity may contribute to three-dimensional chromatin organization through interactions between DNA duplexes.

Potential Mechanisms for Homological Coupling

The volcano-shaped enrichment pattern indicates that homologous sequences may preferentially couple, thus making chromatin folding sequence-specific. This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that similar DNA sequences could recognize and adhere to each other [

10]. We will call this hypothetical phenomenon "homological coupling" or "homocoupling".

The mechanism of homocoupling remains to be determined. We consider several possibilities. One possibility is that negative-from-negative repulsion of DNA duplexes is neutralized by intranuclear small positive ions such as spermins, and two duplexes interact directly to adhere in head-to-head orientation while maintaining their identical sequence alignments. Alternatively, proteins might mediate the recognition process. One intriguing possibility is that distant genomic regions form loops that meet at individual nucleosomes, where their sequences are, in effect, compared and reversibly retained if sufficiently similar. This would provide a structural basis for sequence comparison without requiring direct DNA-DNA contact.

From One-Dimensional Sequence to Three-Dimensional Structure

If homological coupling occurs, it could provide a mechanism for translating linear sequence information into spatial organization. Similar repetitive sequences distributed along chromosomes might find each other in nuclear space, potentially creating functional contacts based on sequence homology. This process could contribute to chromatin reorganization in response to changing conditions. Homological coupling could bring distant regions together by looping in 3D, to combine genes with their regulatory elements. Thus linear, one-dimensional genomic sequence would program its three-dimensional folding and function.

If repetitive elements compete for coupling partners based on sequence similarity, this would create dynamic equilibria in chromatin organization. Stronger homology might produce more stable interactions, while weaker homology could allow for more transient contacts. Such competition could contribute to chromatin reorganization. Changes in one region might affect its availability for interactions, potentially influencing the organization of other genomic regions. This represents one possible mechanism for gene expression and cell cycle coordination.

Transposable Elements as Genomic Organizers

Although we have not yet directly determined whether the observed homologies occur between transposable elements, this is likely the case. Since transposable elements comprise over 50% of the genome and represent the primary source of sequence homology, they would overwhelmingly dominate homology-mediated interactions compared to low-copy sequences. If this is found to be the case, that would suggest that transposable elements may serve a positive function and are not genomic parasites. It is likely that transposable elements have evolved to be retained at non-random genomic positions where they program chromatin folding and therefore function through homological coupling. Their repetitive nature makes them ideal candidates for creating a mesh of coupling anchors. Repetitive elements retained at specific locations could serve as genomic "anchors" that bring together distant regulatory regions or create boundaries between functional domains.

DNA methylation of transposable elements could modulate homological coupling strength. Razin et al. (2007) proposed that methylation enhances DNA hydrophobicity, promoting chromatin compaction. This mechanism suggests that methylated regions might preferentially interact through hydrophobic forces, potentially altering which sequences participate in homological coupling.

Epigenetic Modulation of Coupling

Razin et al. [

14] proposed, based on experimental evidence, that chromatin condensation is mediated by hydrophobicity caused by DNA methylation, and this was further expanded by Kaur et al. [

15]. It is well established that normally methylated and compacted transposable elements undergo waves of demethylation and decompaction during development and cancer [

16,

17]. Accordingly, we suggest that proposed homological coupling can be regulated by methylation, causing coupling and demethylation, causing uncoupling.

Mechanism of Clustering of Alu and L1 Elements

Alu and L1 elements are the most abundant repetitive elements in our genome, comprising 28% of its total length and represented by about 1.6 million copies. The total weight of DNA in an adult body is approximately 250 g, of which Alu and L1 elements constitute about 66 g. Although these repeats are spread uniformly over the genome in seemingly random fashion, they form tight clusters in 3D as measured by live FISH microscopy [

18]. Although other mechanisms can be responsible for this 3D clustering, such as mediated by Alu-binding protein, we also suggest that homological coupling should be considered as a primary mechanism of such clustering.

Future Directions

To understand which sequences participate in homological coupling, we need to map the actual homologous regions at contact points. Are they specific transposon families? What is the minimum homology length and percent identity required? Do certain sequence motifs promote or inhibit coupling? The answers will determine whether this mechanism contributes to gene regulation or merely reflects passive chromatin organization.

This work establishes homological coupling as a potential chromatin organizing principle. Critical questions remain: What is the minimum homology length and identity required for coupling? Which transposon families participate? What specific motifs provide stronger coupling? What functional elements, such as genes, are associated with coupled transposable elements, and what is the possible functional consequence of coupling for these specific genes?

In vivo and in vitro experiments with synthetic and modified sequences could test homological coupling experimentally. FRET and Micro-C could serve as readouts of homocoupling efficiency. If validated, homological coupling might enable practical applications. Controlling chromatin architecture through sequence-based coupling could help direct cell fate and improve cellular reprogramming efficiency in regenerative medicine. Repetitive elements would become potential therapeutic targets in diseases involving chromatin dysfunction.

In summary, this initial report of in-pair homology enrichment near chromatin contacts suggests that sequence homology may direct chromatin folding in a sequence-specific manner, leading to the pairing of identical sequences (homological coupling). Further research is needed to verify this finding and characterize the mechanism of homological coupling.

Data Availability Statement

The custom python scripts developed in this study are openly available in Github https://github.com/maxrempel/lp2

Acknowledgements

We thank Jekaterina Erenpreisa for suggesting relevance of hydrophobicity and Alu clustering. The research was funded solely by the author.

References

- Cordaux, R.; Batzer, M.A. The Impact of Retrotransposons on Human Genome Evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 691–703, . [CrossRef]

- Deininger, P. Human Retrotransposable Elements: An End or Just the Beginning? Nature Reviews Genetics 2021, 22, 749–771, . [CrossRef]

- Polesskaya, O.; Guschin, V.; Kondratev, N.; Garanina, I.; Nazarenko, O.; Zyryanova, N.; Tovmash, A.; Mara, A.; Shapiro, T.; Erdyneeva, E.; et al. On Possible Role of DNA Electrodynamics in Chromatin Regulation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2017, . [CrossRef]

- Polesskaya, O.; Kananykhina, E.; Roy-Engel, A.M.; Nazarenko, O.; Kulemzina, I.; Baranova, A.; Vassetsky, Y.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. The Role of Alu-Derived RNAs in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Conditions. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 115, 29–34, . [CrossRef]

- V. Savelyev, I.; V. Zyryanova, N.; O. Polesskaya, O.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. On the Existence of the DNA Resonance Code and Its Possible Mechanistic Connection to the Neural Code. Neuroquantology 2019, 17, . [CrossRef]

- Savelev, I.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. Possible Traces of Resonance Signaling in the Genome. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2020, 151, 23–31, . [CrossRef]

- Savelev, I.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. Evidence for DNA Resonance Signaling via Longitudinal Hydrogen Bonds. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2020, 156, 14–19, . [CrossRef]

- Myakishev-Rempel, M.; Savelev, I.V. How Schrödinger’s Mice Weave Consciousness. In Rhythmic Advantages in Big Data and Machine Learning; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 201–224 ISBN 9789811657221.

- Savelev, I.V.; Miller, R.A.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. How the Biofield Is Created by DNA Resonance. In Rhythmic Advantages in Big Data and Machine Learning; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 161–199 ISBN 9789811657221.

- Vikhorev, A.V.; Savelev, I.V.; Polesskaya, O.O.; Rempel, M.M.; Miller, R.A.; Vetcher, A.A.; Myakishev-Rempel, M. The Avoidance of Purine Stretches by Cancer Mutations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11050, . [CrossRef]

- Vikhorev, A.V.; Rempel, M.M.; Polesskaya, O.O.; Savelev, I.V.; Myakishev-Rempel, M.V. Patterns of Transposable Element Distribution around Chromatin Ligation Points Revealed by Micro-C Data Analysis. arXiv [q-bio.OT] 2024.

- Krietenstein, N.; Abraham, S.; Venev, S.V. Recent Advancements in Chromosome Conformation Capture Techniques, Particularly Micro-C, Have Enabled High-Resolution Mapping of Chromatin Interactions" in Introduction. Molecular Cell 2020, 554–565.

- McGinty, S.P.; Kaya, G.; Sim, S.B.; Corpuz, R.L.; Quail, M.A.; Lawniczak, M.K.N.; Geib, S.M.; Korlach, J.; Dennis, M.Y. CiFi: Accurate Long-Read Chromatin Conformation Capture with Low-Input Requirements. bioRxivorg 2025.

- Razin, S.V.; Gavrilov, A.A.; Iarovaia, O.V. Role of DNA Methylation in Heterochromatin Formation and Gene Silencing. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2007, 72, 1385–1399, . [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Plochberger, B.; Costa, P.; Cope, S.M.; Vaiana, S.M.; Lindsay, S. Hydrophobicity of Methylated DNA as a Possible Mechanism for Gene Silencing. Phys. Biol. 2012, 9, 065001, . [CrossRef]

- Friedli, M.; Trono, D. The Developmental Control of Transposable Elements and the Evolution of Higher Species. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 2015, 31, 429–451, . [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.L.; Wulaningsih, W.; Lehmann, U. Transposable Elements in Human Cancer: Causes and Consequences of Deregulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 974, . [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-Y.; Chang, L.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, S.; Chao, C.-W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; et al. Homotypic Clustering of L1 and B1/Alu Repeats Compartmentalizes the 3D Genome. Cell Research 2021, 31, 1037–1051, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).