Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Teach and Repeat Path Following

3. Methodology

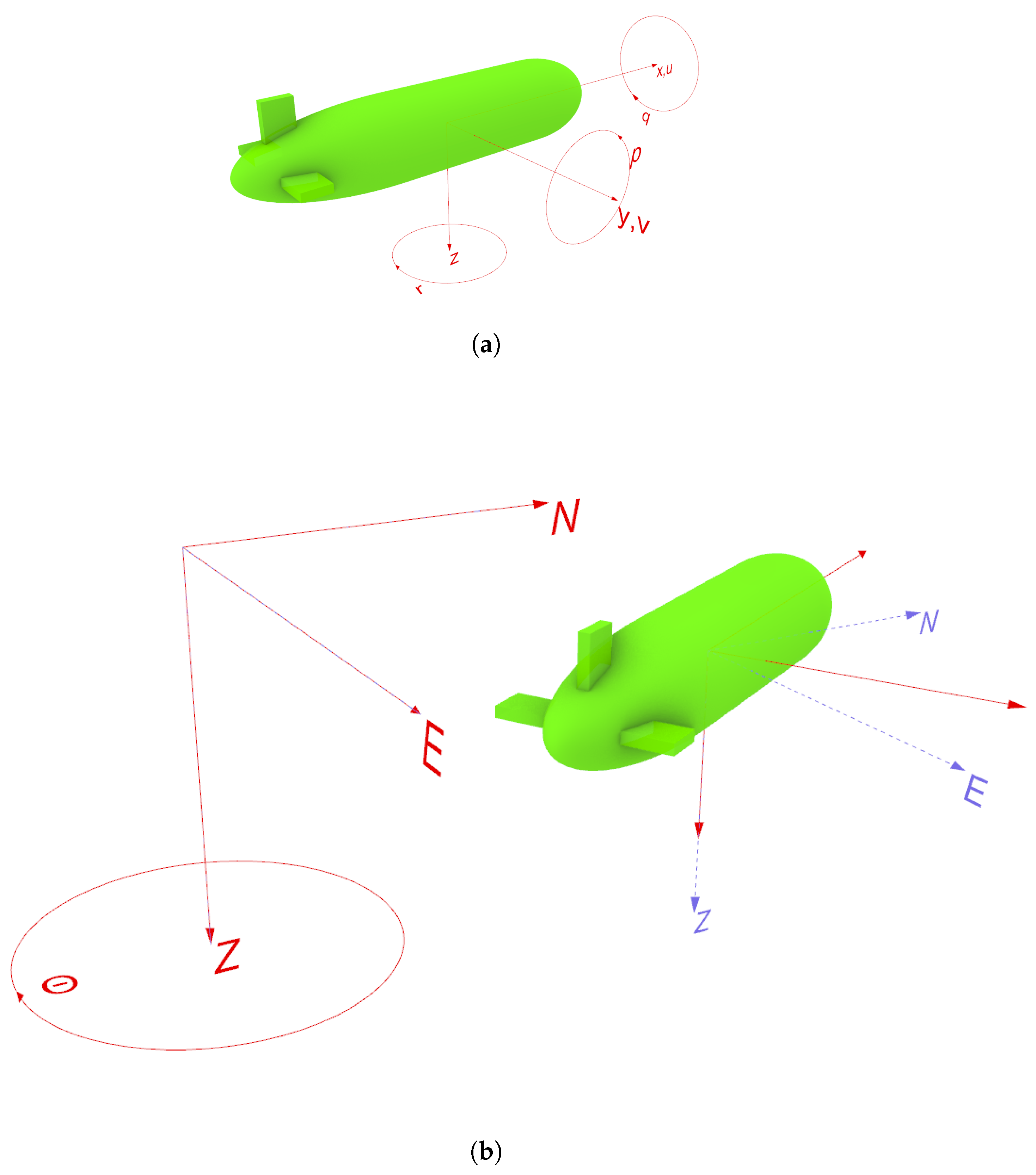

3.1. Conventions

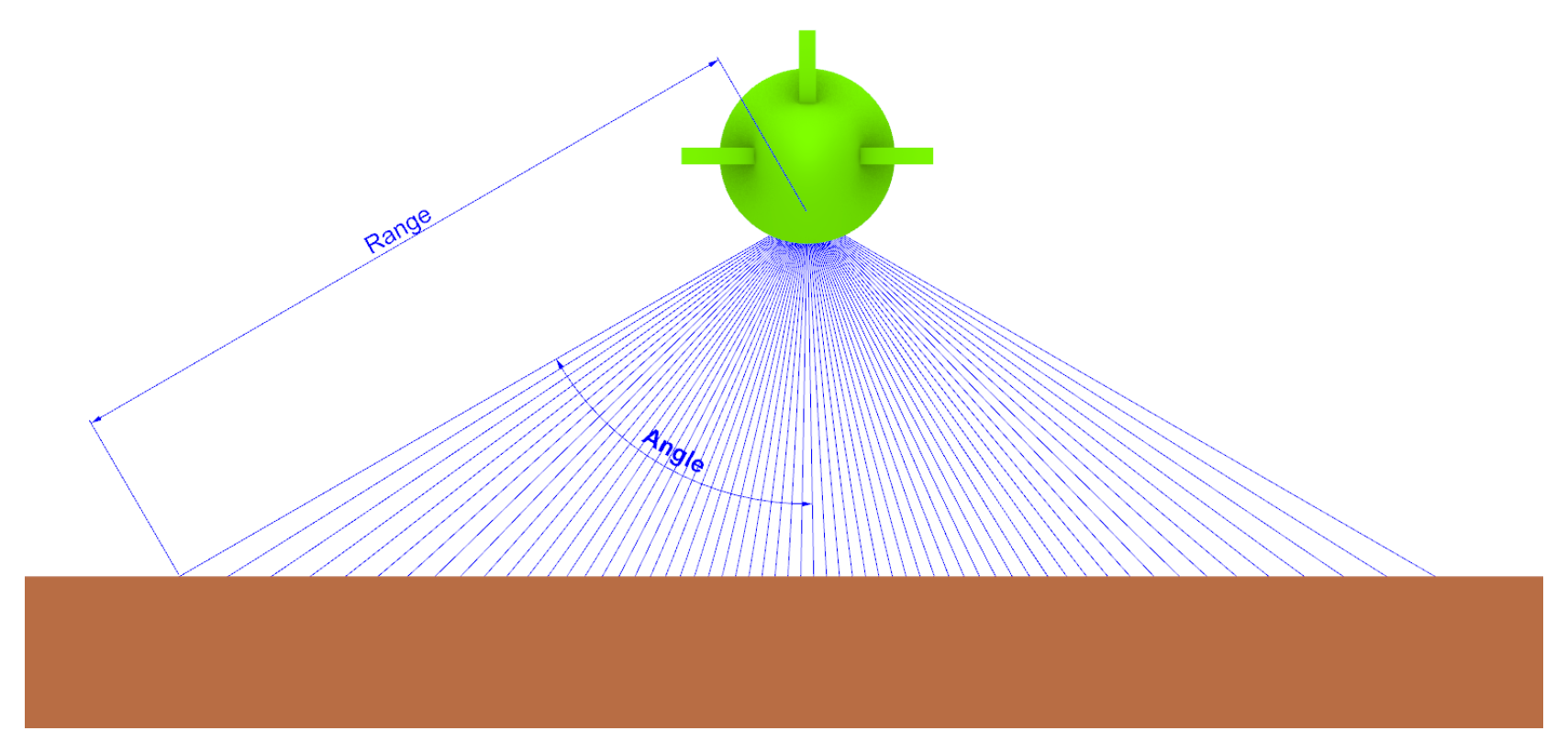

3.2. Multibeam Sonar

3.3. Pose Merging

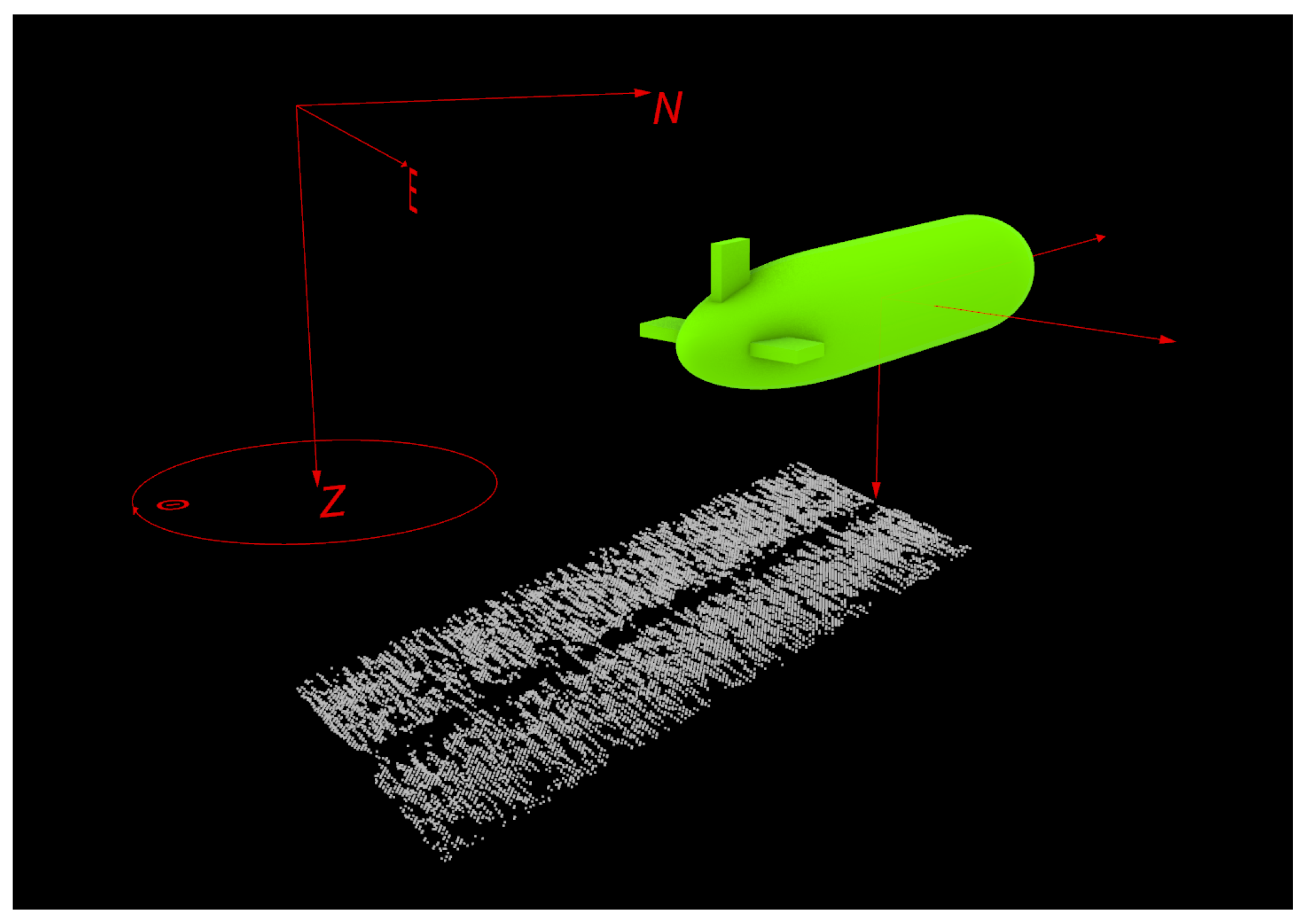

3.4. 3D Point Set Generation

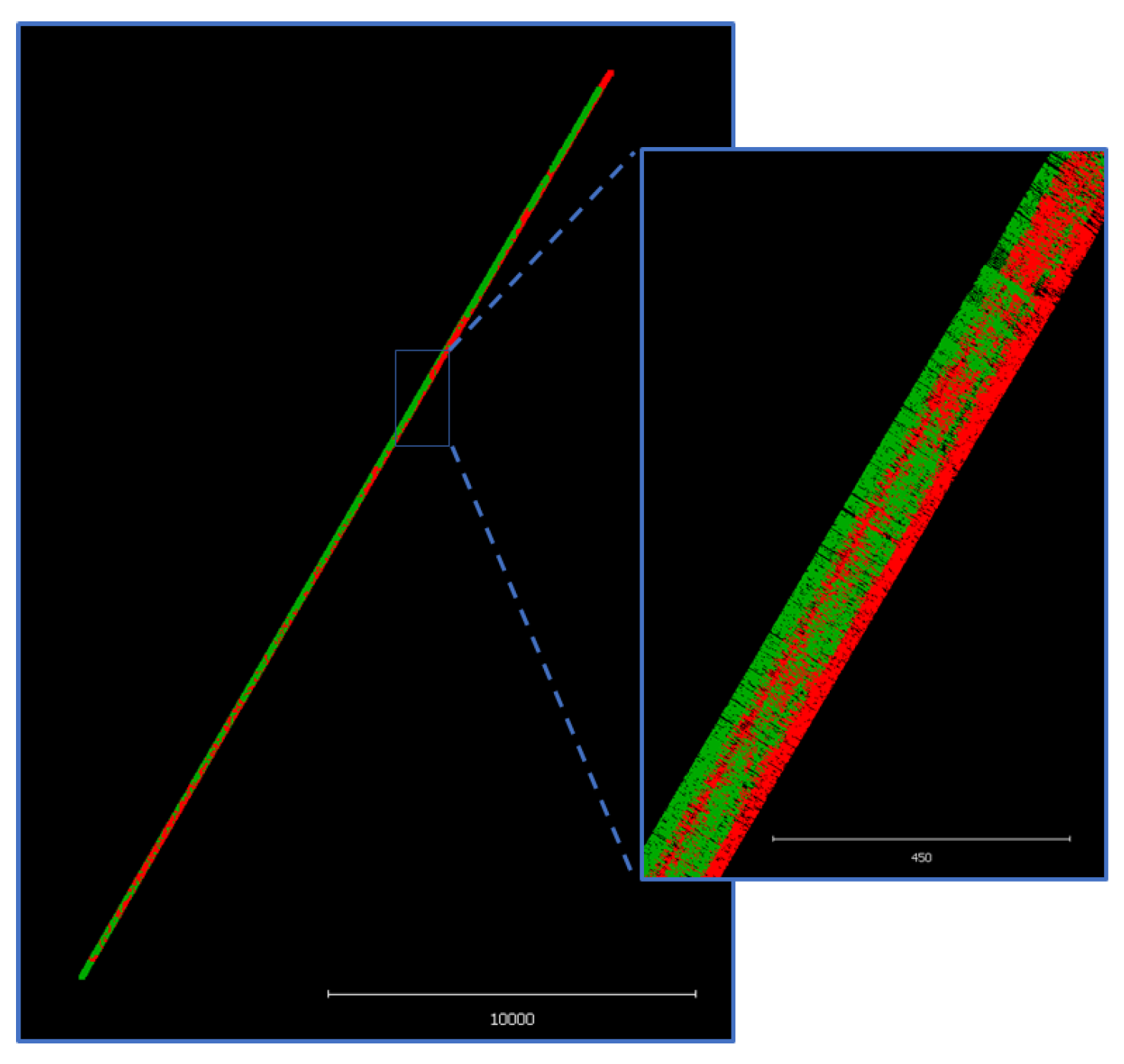

3.5. Local Map Generation

3.6. Filtering

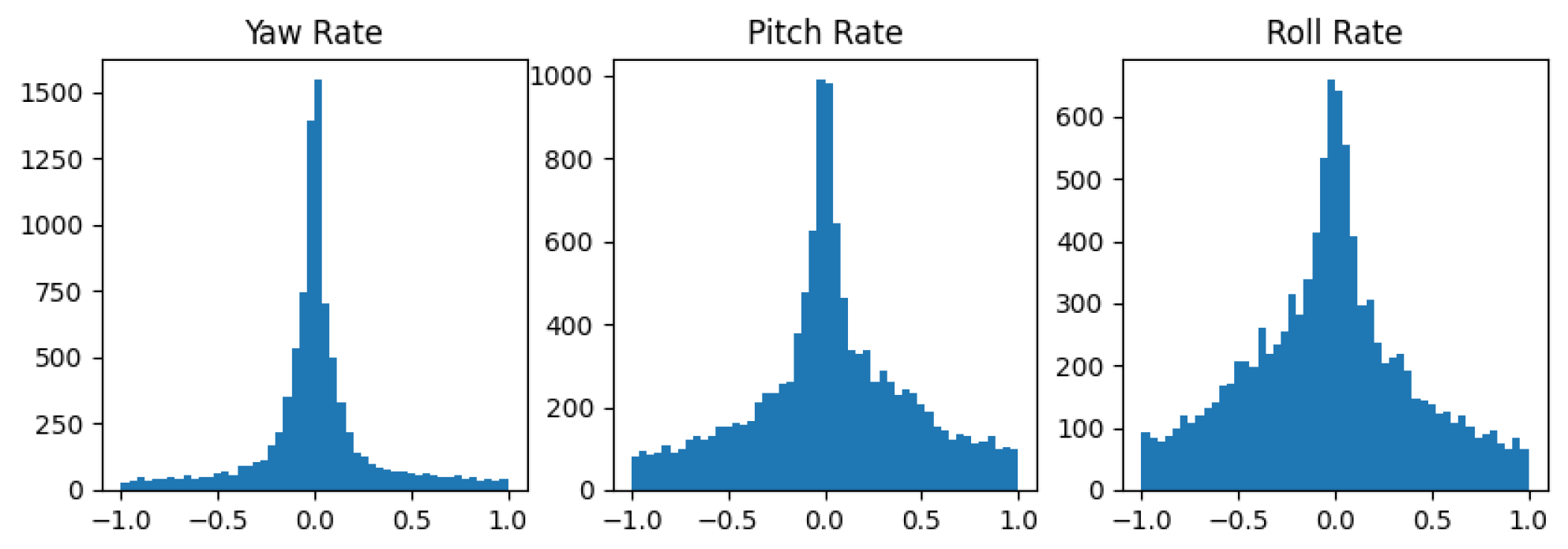

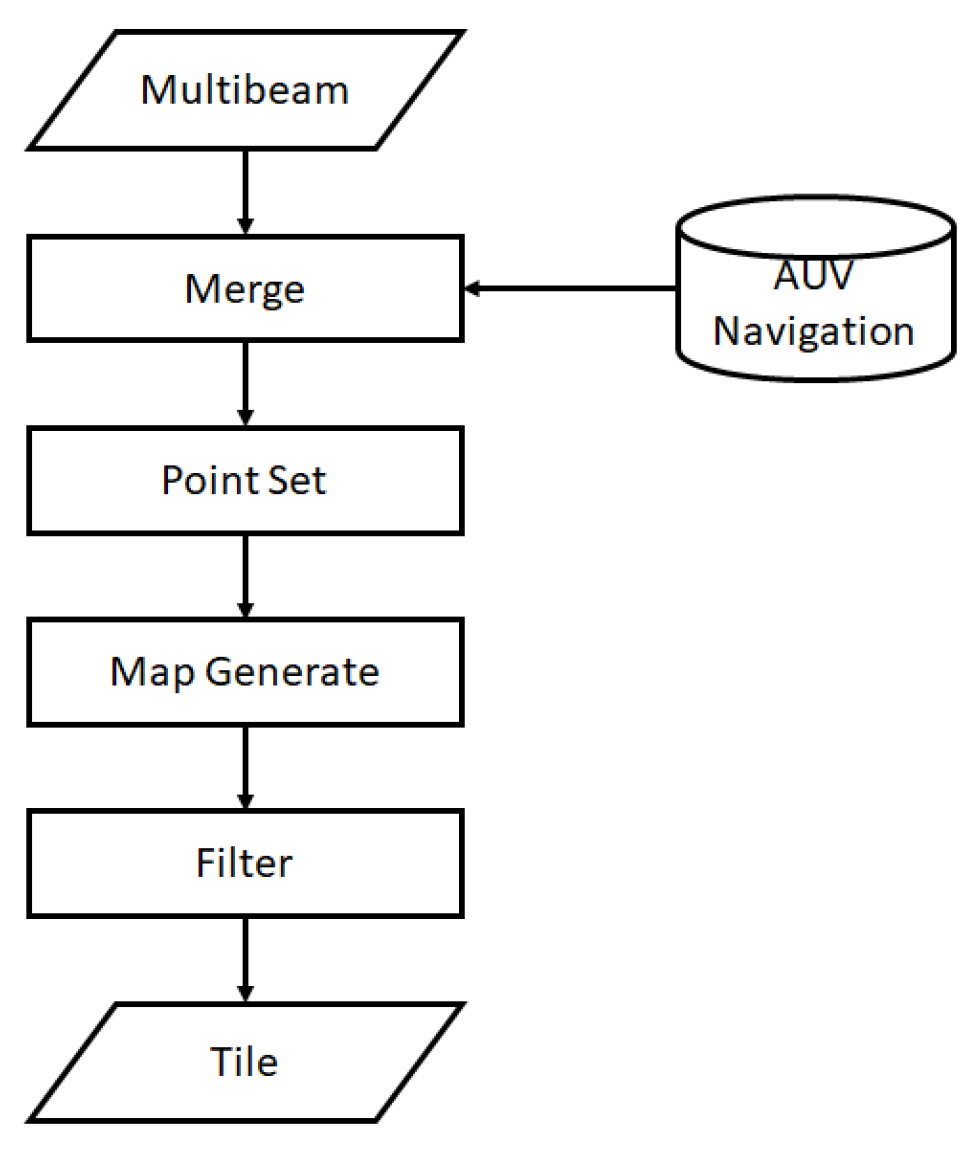

3.7. Data Preparation Workflow

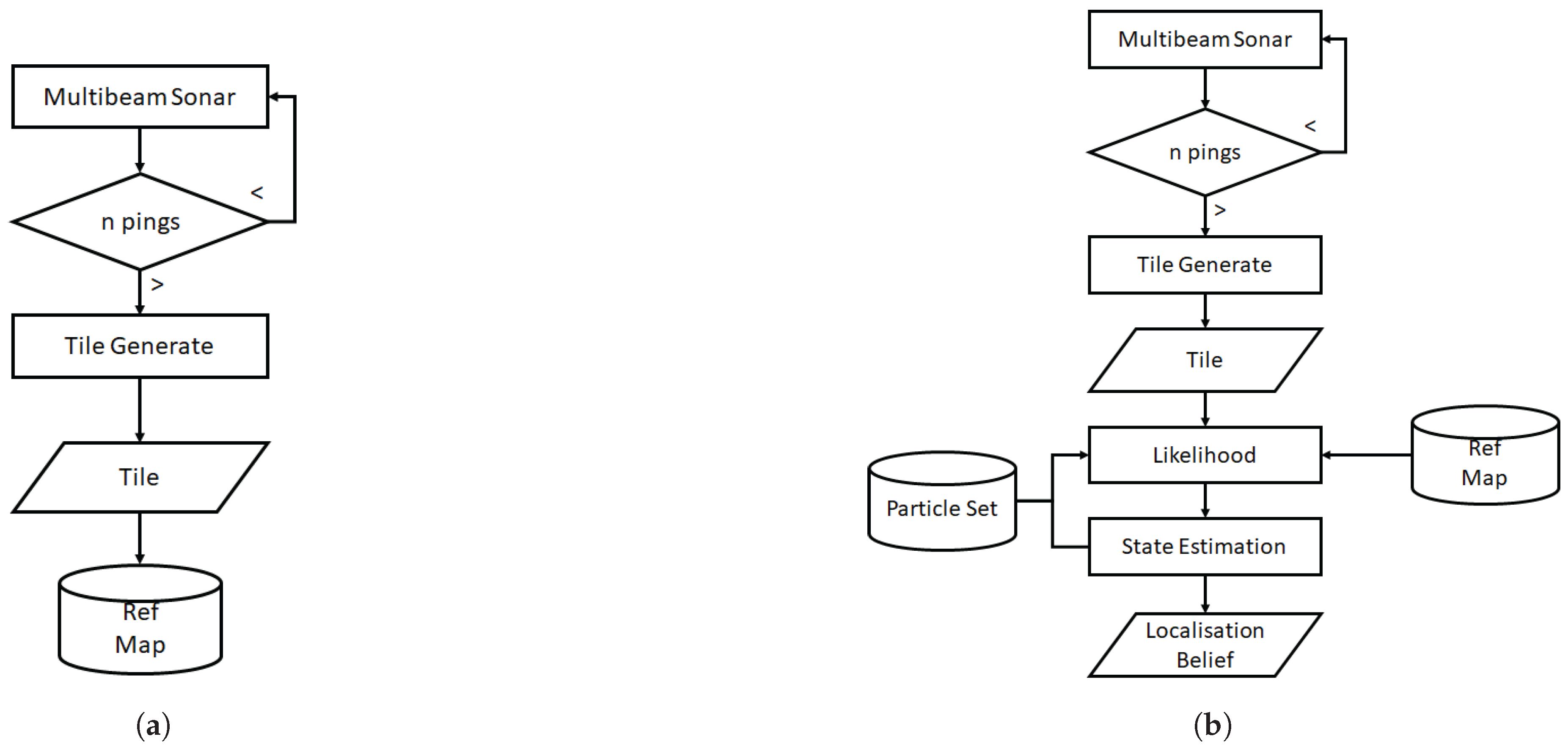

4. Teach and Repeat Implementation

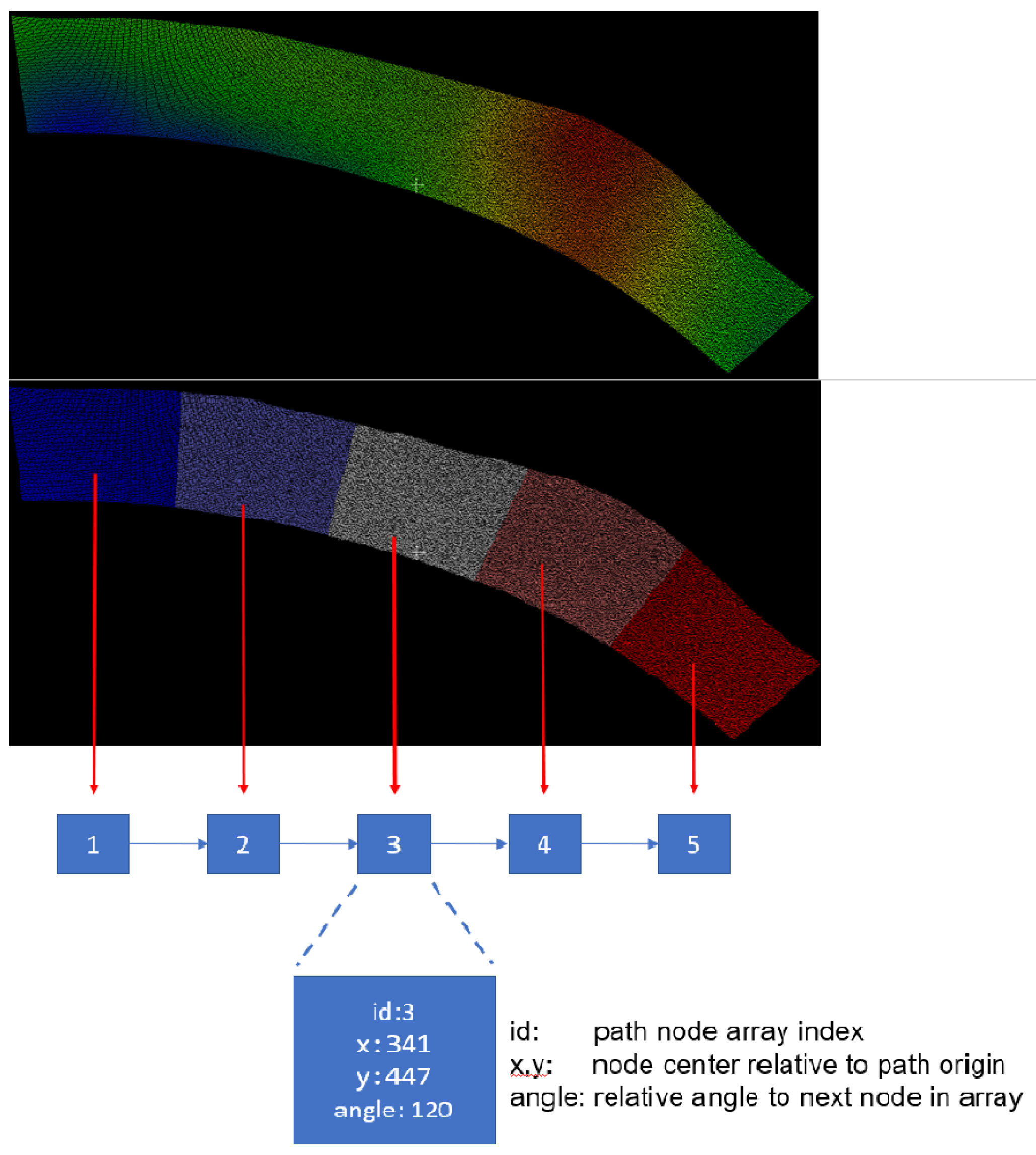

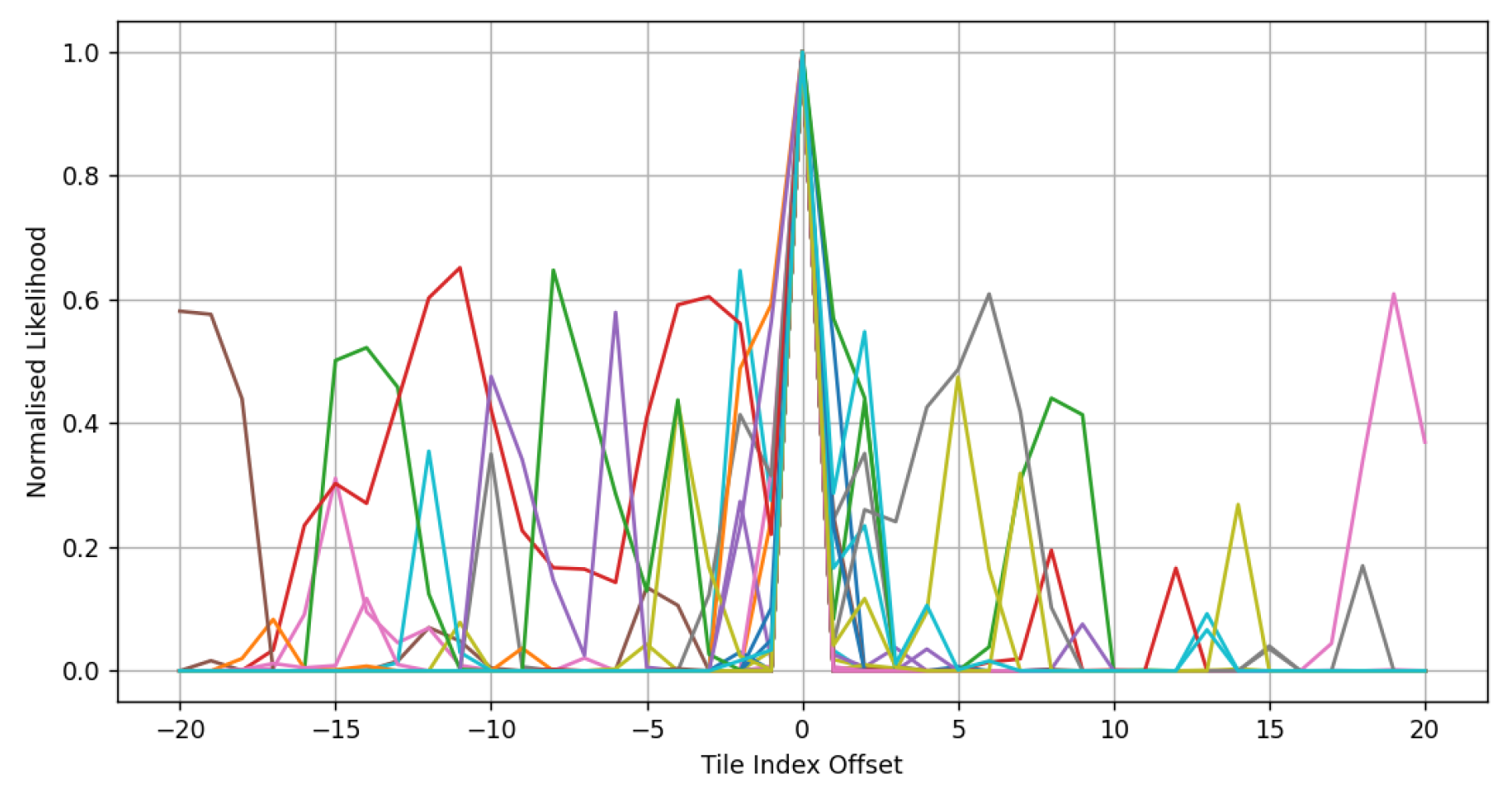

4.1. Tile Association

4.2. State Estimation

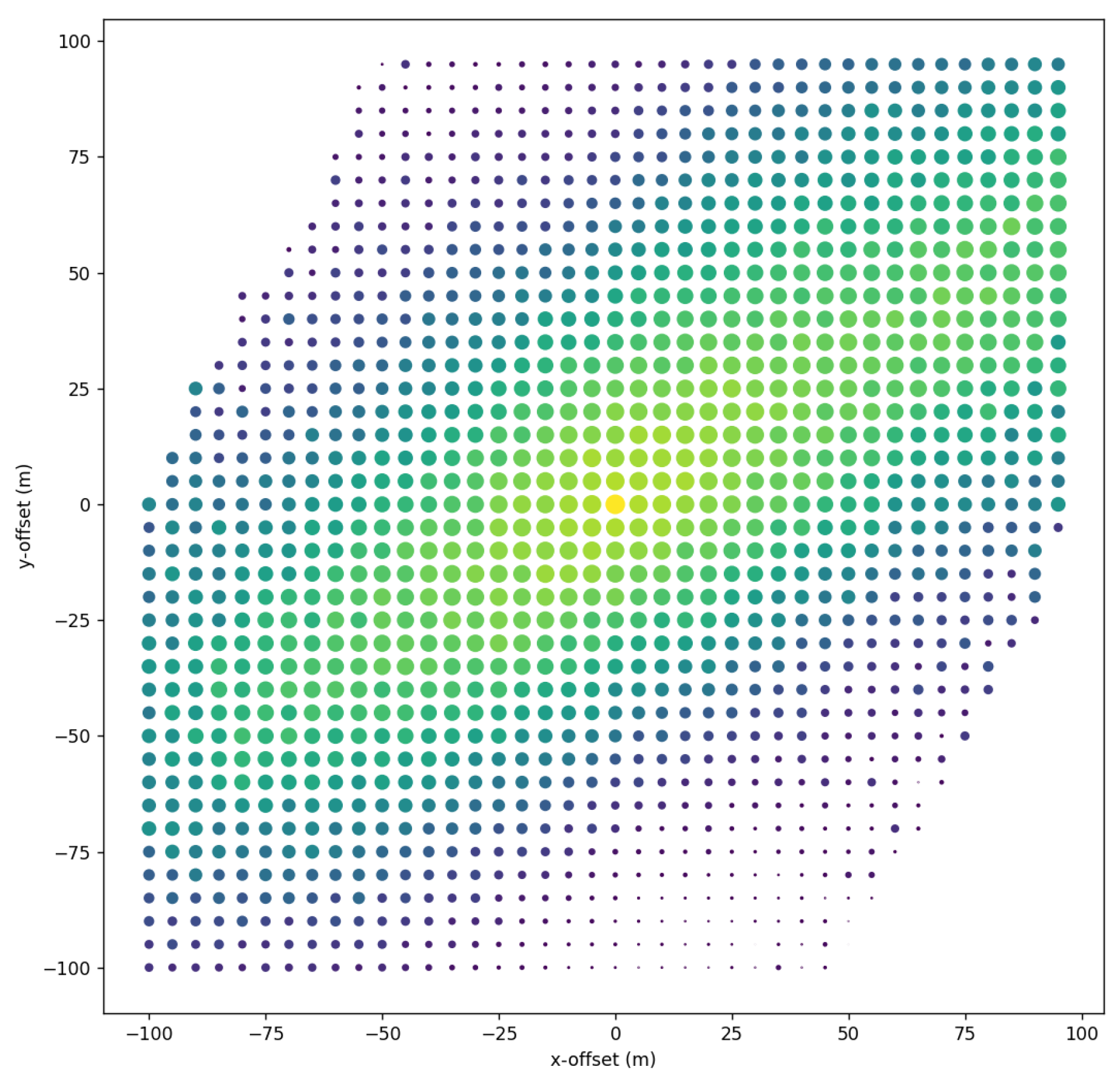

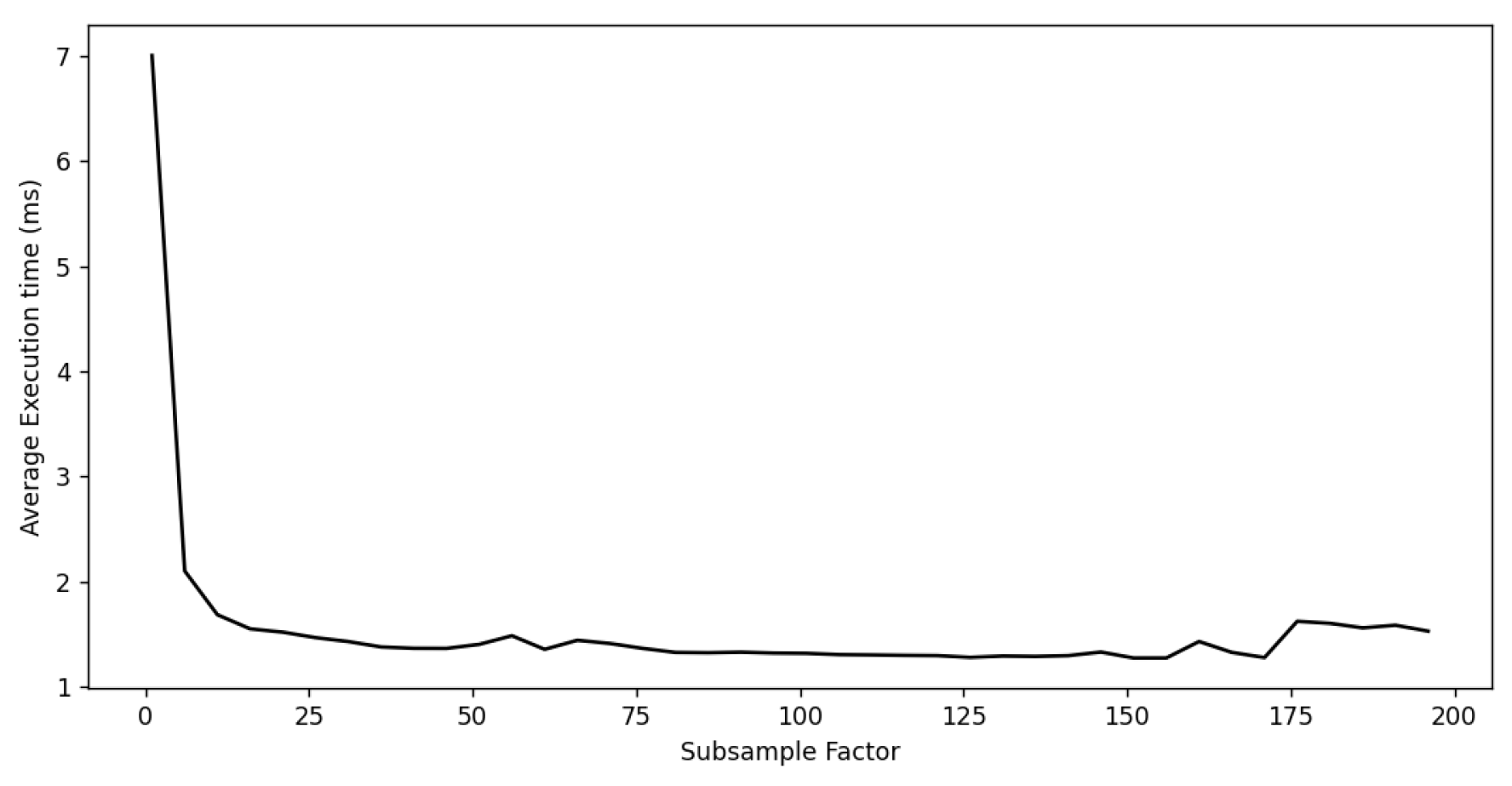

5. Trials and Results

5.1. General

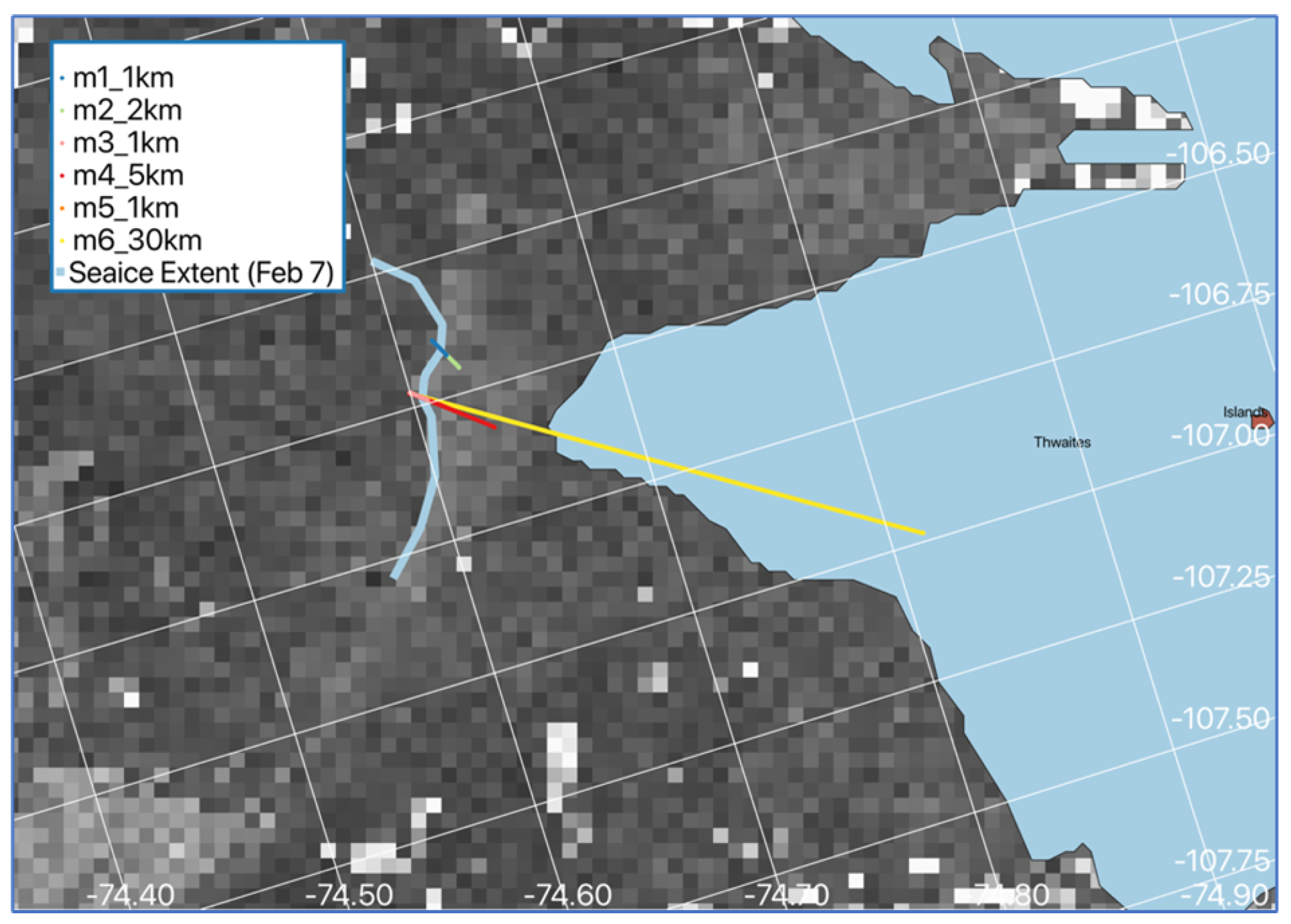

5.2. Data Collection

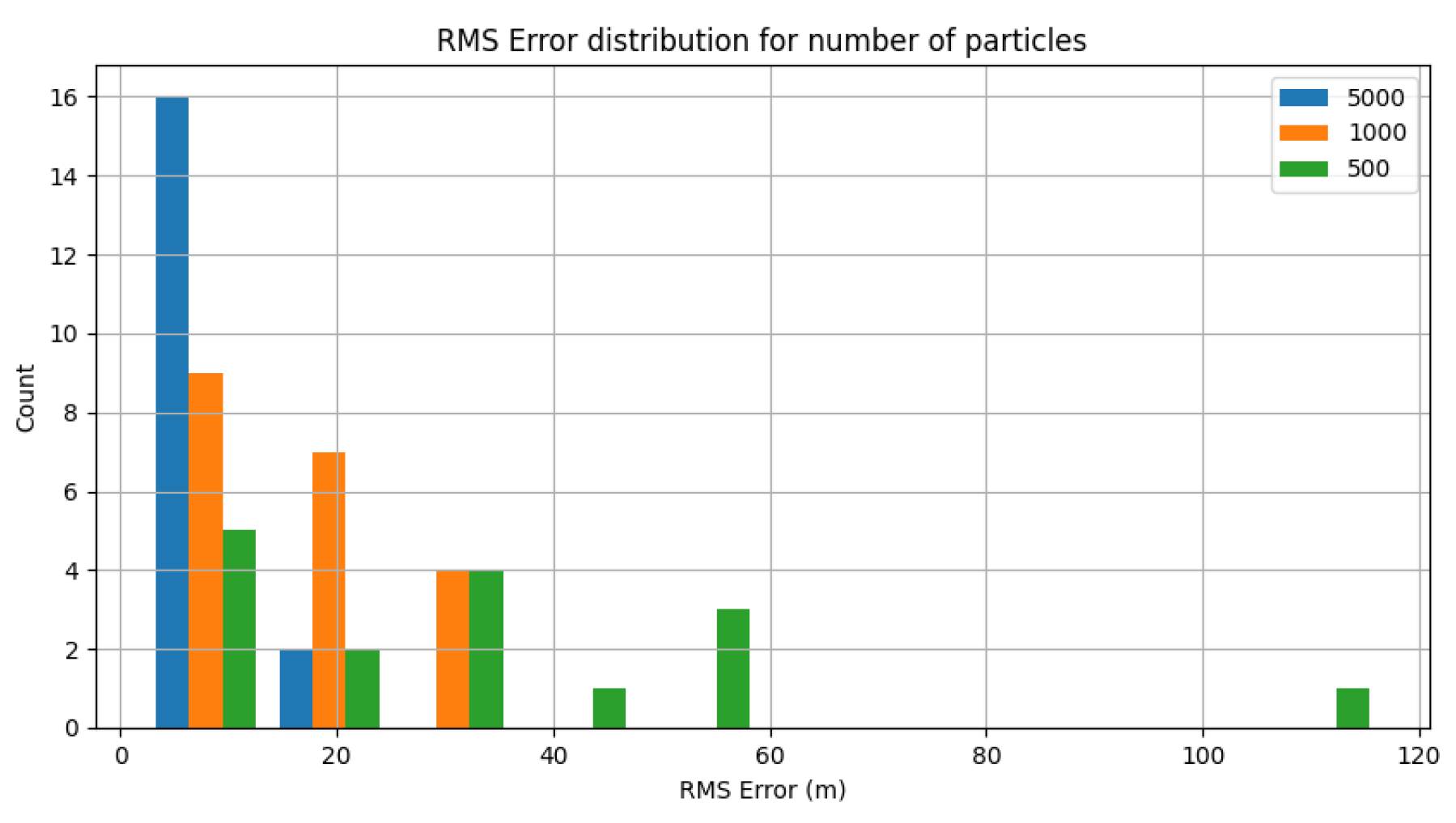

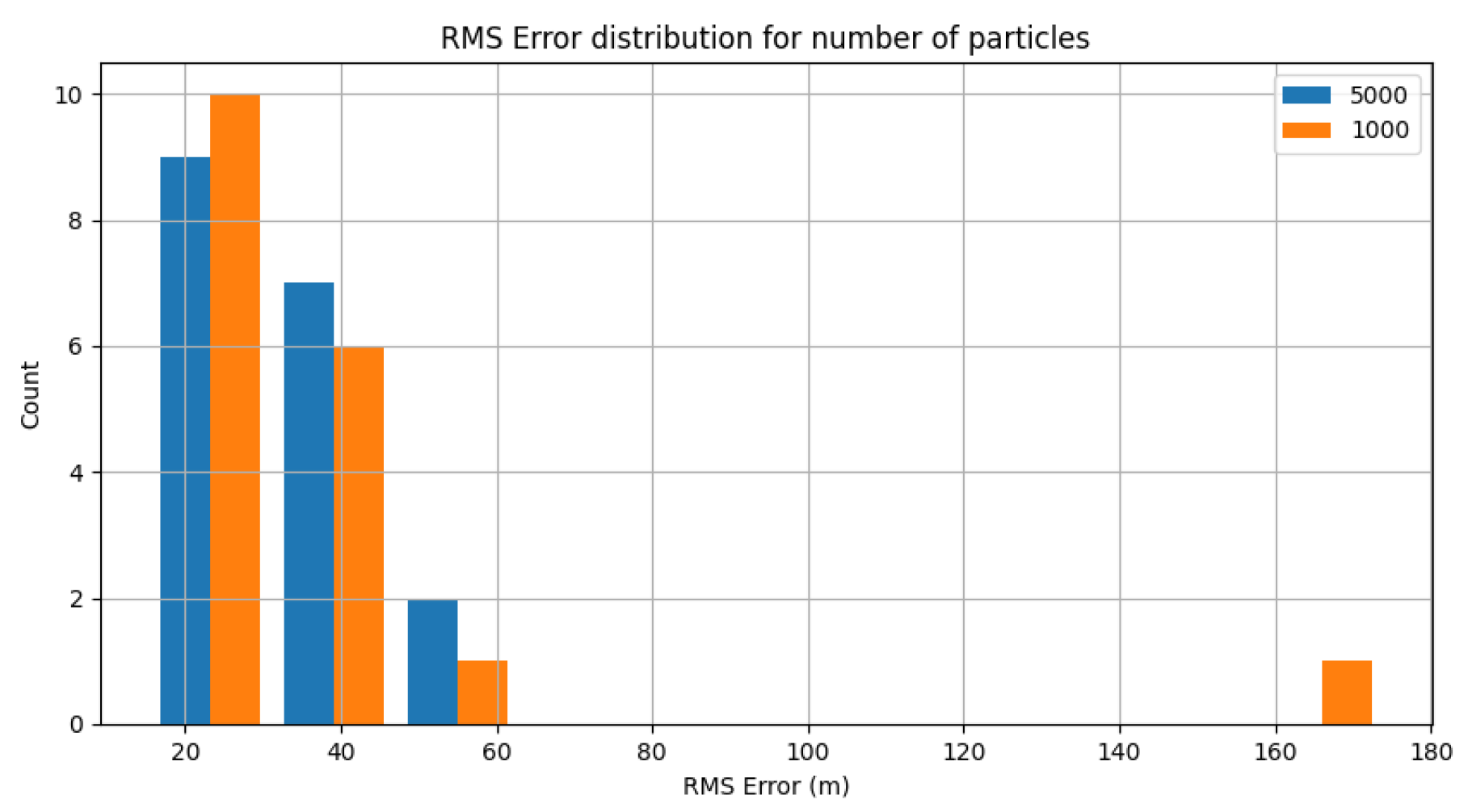

5.3. Tests

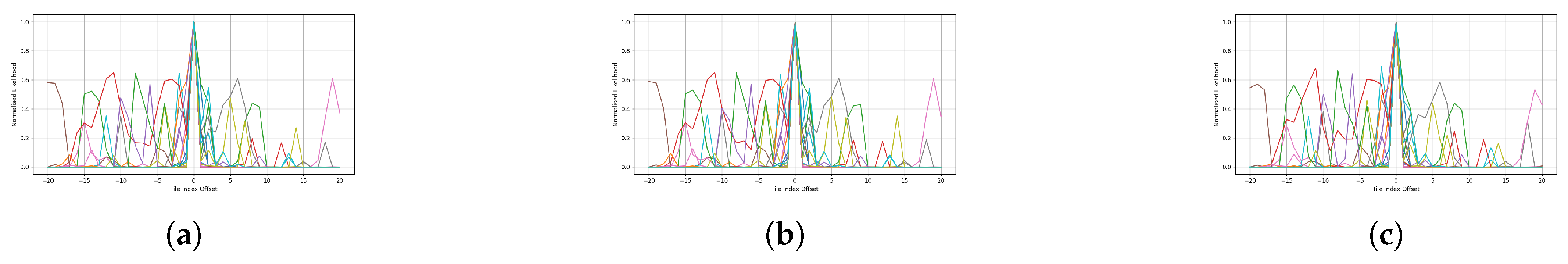

5.4. Likelihood Performance

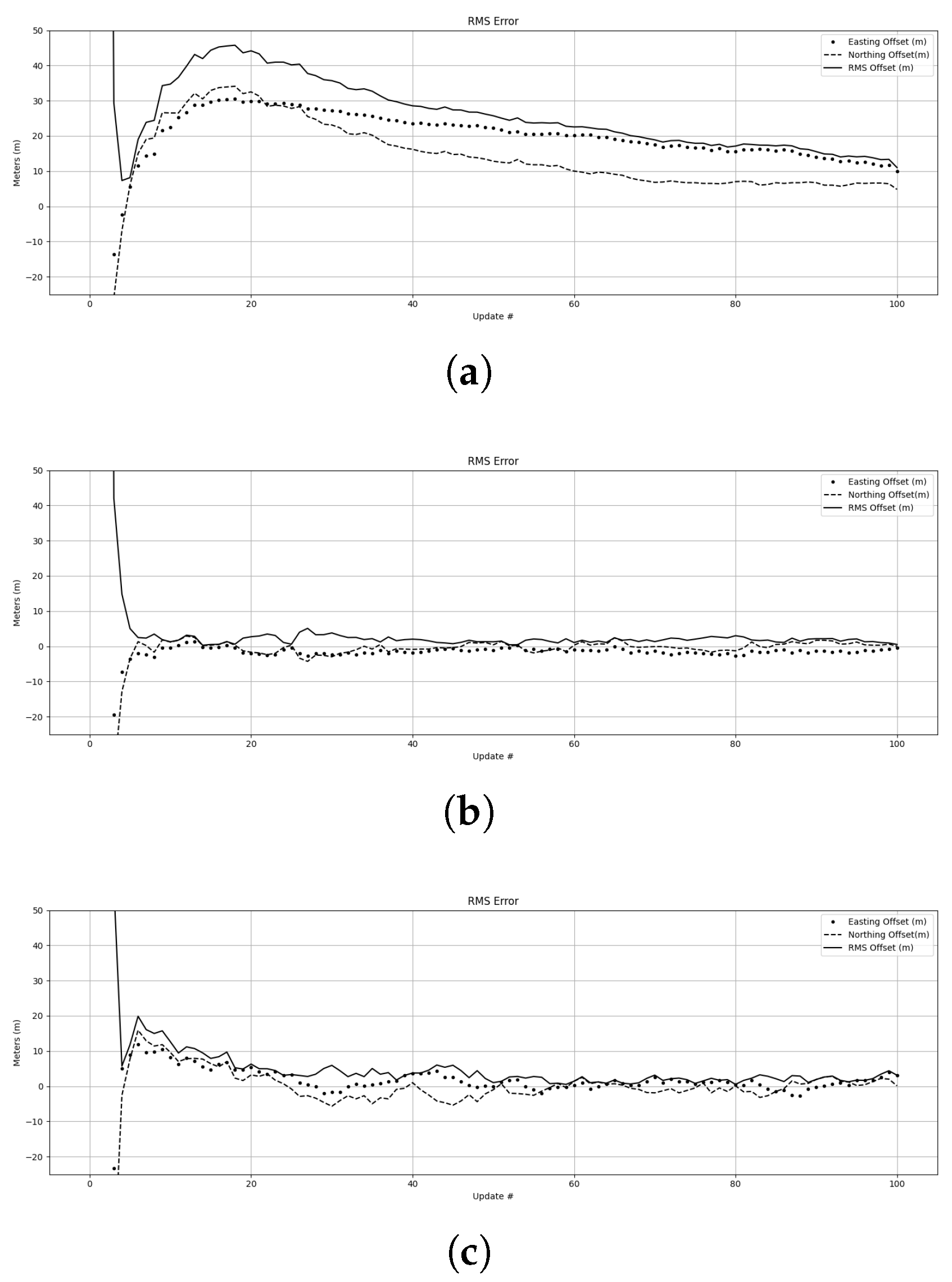

5.5. Control Results

5.6. Trial Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Work

References

- M. V. Jakuba, C. N. Roman, H. Singh, C. Murphy, C. Kunz, C. Willis, T. Sato, R. A. Sohn, Long-baseline acoustic navigation for under-ice autonomous underwater vehicle operations, Journal of Field Robotics 25 (11-12) (2008) 861–879. [CrossRef]

- P. King, A. Vardy, A. L. Forrest, Teach-and-repeat path following for an autonomous underwater vehicle, Journal of Field Robotics 35 (5) (2018) 748–763. [CrossRef]

- L. Paull, S. Saeedi, M. Seto, H. Li, Auv navigation and localization: A review, IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 39 (1) (2014) 131–149. [CrossRef]

- R. McEwen, H. Thomas, D. Weber, F. Psota, Performance of an auv navigation system at arctic latitudes, IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 30 (2) (2005) 443–454. [CrossRef]

- A. Tal, I. Klein, R. Katz, Inertial navigation system/doppler velocity log (ins) fusion with partial dvl measurements, Sensors 17 (2) (2017) 415.

- Phins surface (Dec 2022). https://www.ixblue.com/store/phins-surface/.

- P. King, G. Williams, R. Coleman, K. Zürcher, I. Bowden-Floyd, A. Ronan, C. Kaminski, J.-M. Laframboise, S. McPhail, J. Wilkinson, A. Bowen, P. Dutrieux, N. Bose, A. Wahlin, J. Andersson, P. Boxall, M. Sherlock, T. Maki, Deploying an auv beneath the sørsdal ice shelf: Recommendations from an expert-panel workshop, in: 2018 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Workshop (AUV), 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- P. King, K. Zürcher, I. Bowden-Floyd, A risk-averse approach to mission planning: nupiri muka at the thwaites glacier, in: 2020 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Symposium (AUV), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- F. Maurelli, S. Krupiński, X. Xiang, Y. Petillot, Auv localisation: a review of passive and active techniques, International Journal of Intelligent Robotics and Applications (2021) 1–24.

- P. King, B. Anstey, A. Vardy, Sonar image registration for localization of an underwater vehicle, The Journal of Ocean Technology 12 (3) (2017) 68–90.

- G. Salavasidis, A. Munafò, C. A. Harris, T. Prampart, R. Templeton, M. Smart, D. T. Roper, M. Pebody, S. D. McPhail, E. Rogers, et al., Terrain-aided navigation for long-endurance and deep-rated autonomous underwater vehicles, Journal of Field Robotics 36 (2) (2019) 447–474.

- B. Claus, R. Bachmayer, Terrain-aided navigation for an underwater glider, Journal of Field Robotics 32 (7) (2015) 935–951. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Williams, O. Pizarro, M. V. Jakuba, I. Mahon, S. D. Ling, C. R. Johnson, Repeated auv surveying of urchin barrens in north eastern tasmania, in: 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2010, pp. 293–299. [CrossRef]

- I. Mahon, S. B. Williams, O. Pizarro, M. Johnson-Roberson, Efficient view-based slam using visual loop closures, IEEE Transactions on Robotics 24 (5) (2008) 1002–1014.

- P. Furgale, T. D. Barfoot, Visual teach and repeat for long-range rover autonomy, Journal of field robotics 27 (5) (2010) 534–560. [CrossRef]

- T. Krajník, F. Majer, L. Halodová, T. Vintr, Navigation without localisation: reliable teach and repeat based on the convergence theorem, in: 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2018, pp. 1657–1664. [CrossRef]

- T. Nguyen, G. K. Mann, R. G. Gosine, A. Vardy, Appearance-based visual-teach-and-repeat navigation technique for micro aerial vehicle, Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 84 (2016) 217–240. [CrossRef]

- R. Möller, A. Vardy, Local visual homing by matched-filter descent in image distances, Biological cybernetics 95 (5) (2006) 413–430. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, C. Pradalier, F. Pomerleau, R. Siegwart, Scale-only visual homing from an omnidirectional camera, in: 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE, 2012, pp. 3944–3949.

- R. Brooks, Visual map making for a mobile robot, in: Proceedings. 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Vol. 2, IEEE, 1985, pp. 824–829.

- Y. Matsumoto, M. Inaba, H. Inoue, Visual navigation using view-sequenced route representation, in: Proceedings of IEEE International conference on Robotics and Automation, Vol. 1, IEEE, 1996, pp. 83–88.

- S. Simhon, G. Dudek, A global topological map formed by local metric maps, in: Proceedings. 1998 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Innovations in Theory, Practice and Applications (Cat. No.98CH36190), Vol. 3, 1998, pp. 1708–1714 vol.3. [CrossRef]

- Nomenclature for treating the motion of a submerged body through a fluid, The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, Technical and Research Bulletin (1950) (1950) 1–5.

- P. Virtanen, R. Gommers, T. E. Oliphant, M. Haberland, T. Reddy, D. Cournapeau, E. Burovski, P. Peterson, W. Weckesser, J. Bright, S. J. van der Walt, M. Brett, J. Wilson, K. J. Millman, N. Mayorov, A. R. J. Nelson, E. Jones, R. Kern, E. Larson, C. J. Carey, İ. Polat, Y. Feng, E. W. Moore, J. VanderPlas, D. Laxalde, J. Perktold, R. Cimrman, I. Henriksen, E. A. Quintero, C. R. Harris, A. M. Archibald, A. H. Ribeiro, F. Pedregosa, P. van Mulbregt, SciPy 1.0 Contributors, SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python, Nature Methods 17 (2020) 261–272. [CrossRef]

- S. Barkby, S. Williams, O. Pizarro, M. Jakuba, An efficient approach to bathymetric slam, in: 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2009, pp. 219–224. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Iterative point matching for registration of free-form curves and surfaces, International journal of computer vision 13 (2) (1994) 119–152. [CrossRef]

- S. Thrun, W. Burgard, D. Fox, Probabilistic Robotics (Intelligent Robotics and Autonomous Agents), The MIT Press, 2005.

- S. P. Engelson, D. V. McDermott, Error correction in mobile robot map learning, in: Proceedings 1992 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE Computer Society, 1992, pp. 2555–2556.

- H. Choset, K. Lynch, S. Hutchinson, G. Kantor, W. Burgard, L. Kavraki, S. Thrun, Principles of robot motion: Theory, algorithms, and implementation errata!!!! (2007).

- Explorer auv (Feb 2018). https://ise.bc.ca/product/explorer/.

- Imagenex, 837B Delta T 6000 m Profiling, revised May 2017 (2023).

| Symbol | Name | Frame | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | North | NED | meters |

| E | East | NED | meters |

| Z | depth | NED | meters |

| Heading | NED | degrees | |

| x | x-position | Body | meters |

| y | y-position | Body | meters |

| z | range | Body | meters |

| u | forward speed | Body | meters-per-second |

| v | transverse speed | Body | meters-per-second |

| p | roll | Body | degrees |

| q | pitch | Body | degrees |

| r | yaw | Body | degrees |

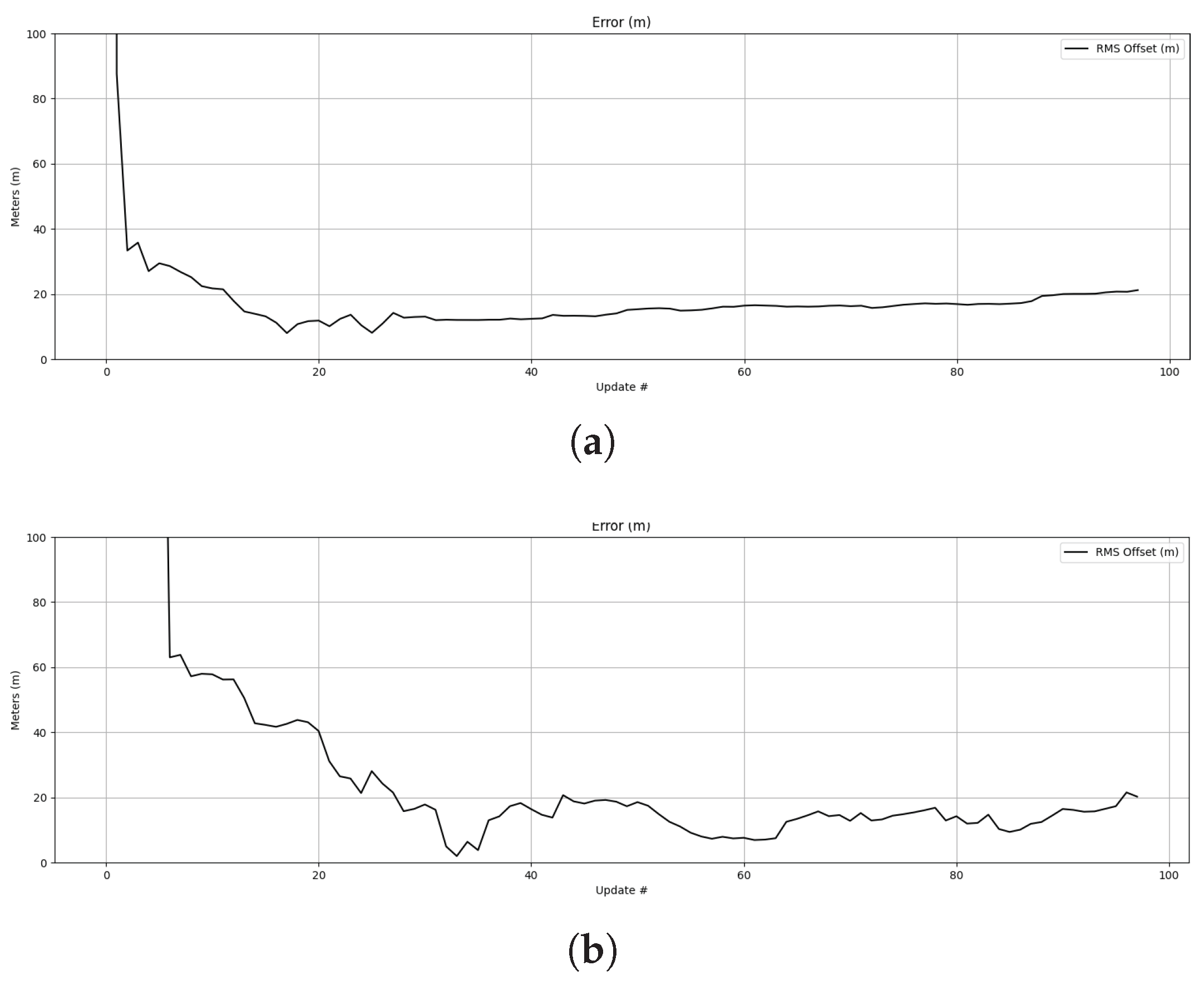

| Particles | Jitter (m) | Sub-sample | N to converge | Error (m) | Maintained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 34.6 | Y |

| 10 | 4 | 51.6 | Y | ||

| 100 | 4 | 26.6 | Y | ||

| 1 | 1 | 4.5 | 72.7 | Y | |

| 10 | 4 | 36.4 | Y | ||

| 100 | Y | ||||

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 4.5 | Y | |

| 10 | 4.5 | 22.1 | Y | ||

| 100 | 5 | 8.6 | Y | ||

| 1000 | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 24.9 | Y |

| 10 | 3 | 23.4 | Y | ||

| 100 | 4 | 18.0 | Y | ||

| 1 | 1 | 3.5 | 12.6 | Y | |

| 10 | 3 | 15.6 | Y | ||

| 100 | 3.5 | 18.6 | Y | ||

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 5.2 | Y | |

| 10 | 4 | 12.2 | Y | ||

| 100 | 3 | 7.9 | Y | ||

| 5000 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 6.4 | Y |

| 10 | 4 | 3.6 | Y | ||

| 100 | 4 | 8.2 | Y | ||

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 5.2 | Y | |

| 10 | 3.5 | 11.4 | Y | ||

| 100 | 3.5 | 10.0 | Y | ||

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 4.2 | Y | |

| 10 | 4 | 2.7 | Y | ||

| 100 | 4 | 3.7 | Y |

| Particles | Jitter (m) | Sub-sample | N to converge | error (m) | Maintained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000.0 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 3.5 | 16.0 | Y |

| 1.0 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 101.2 | Y | |

| 5.0 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 31.9 | Y | |

| 5000.0 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 3.5 | 26.4 | Y |

| 1.0 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 24.8 | Y | |

| 5.0 | 10.0 | 3.5 | 37.5 | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).