Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Flatland Problem: How Scalar Redox Values Conceal the High-Dimensional Structure of Peptide Data

3.2. Conceptual Foundations of Information and Chaos Theory

3.3. Shannon Entropy: Quantifying Uncertainty in Redox Distributions

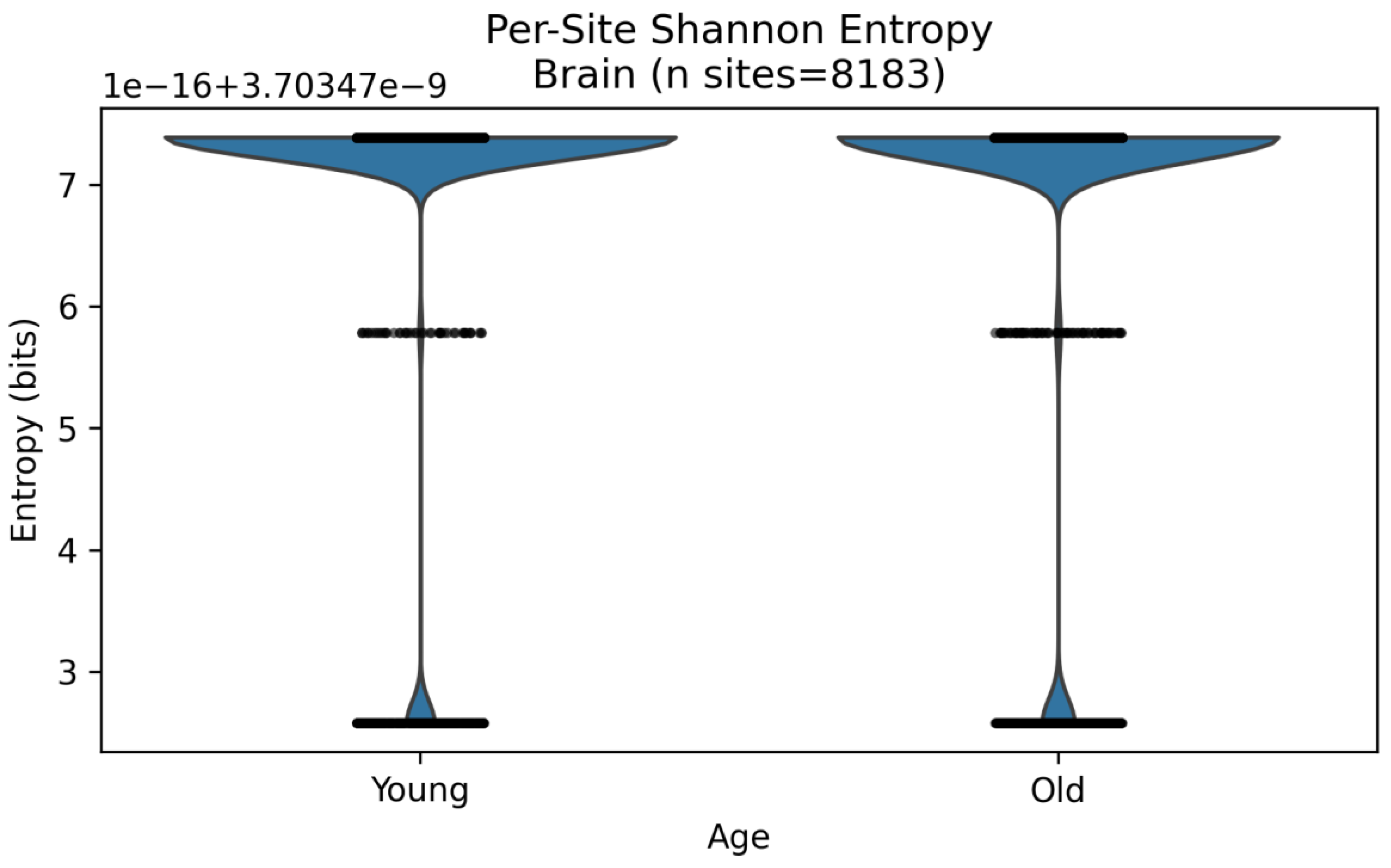

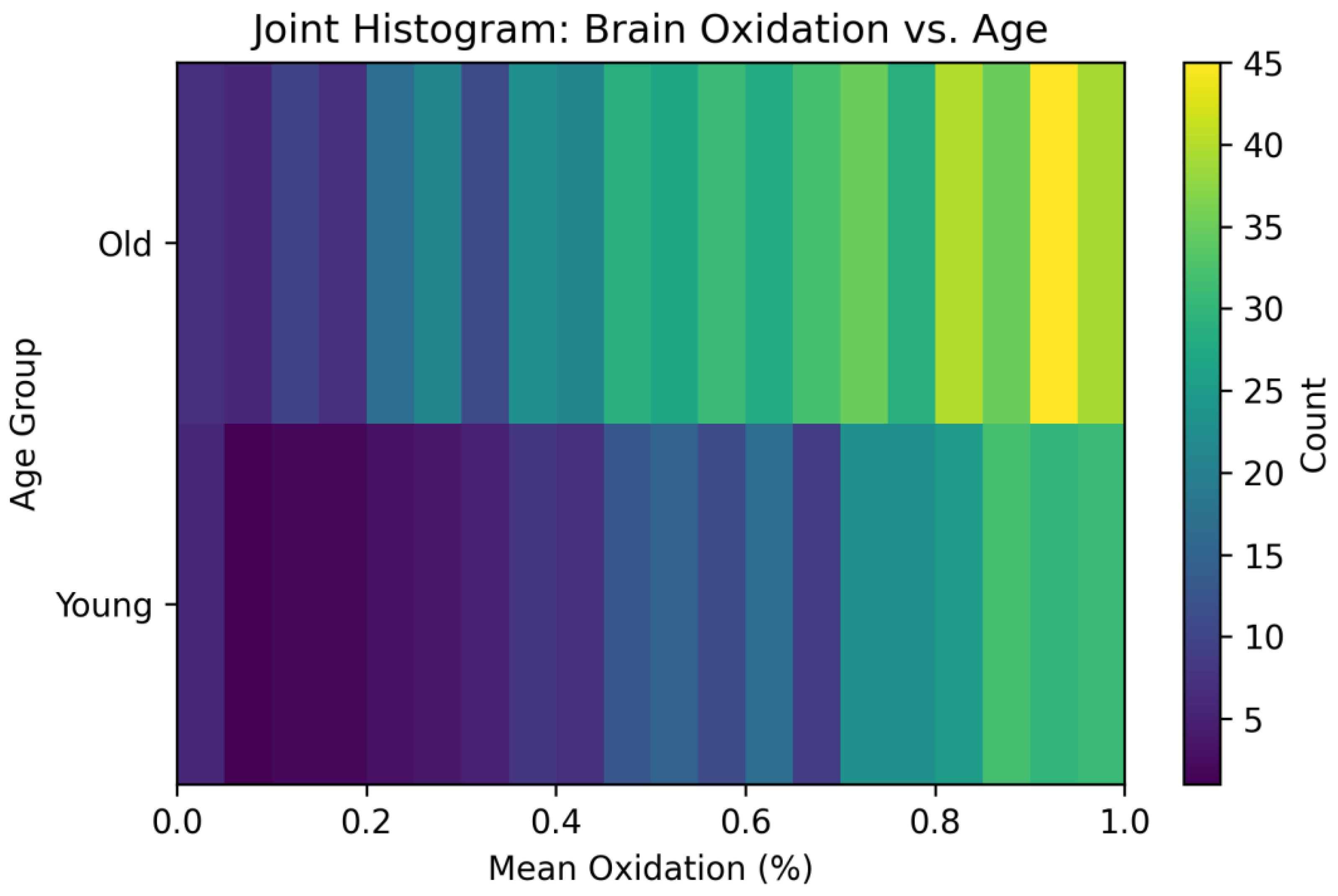

3.4. Mutual Information: Quantifying Shared Information Between Redox States

- (the minimum) bits if X and A are statistically independent—knowing oxidation gives no clue to age.

- (the maximum) bits if and only if oxidation perfectly predicts age (each bin occurs in only one age group).

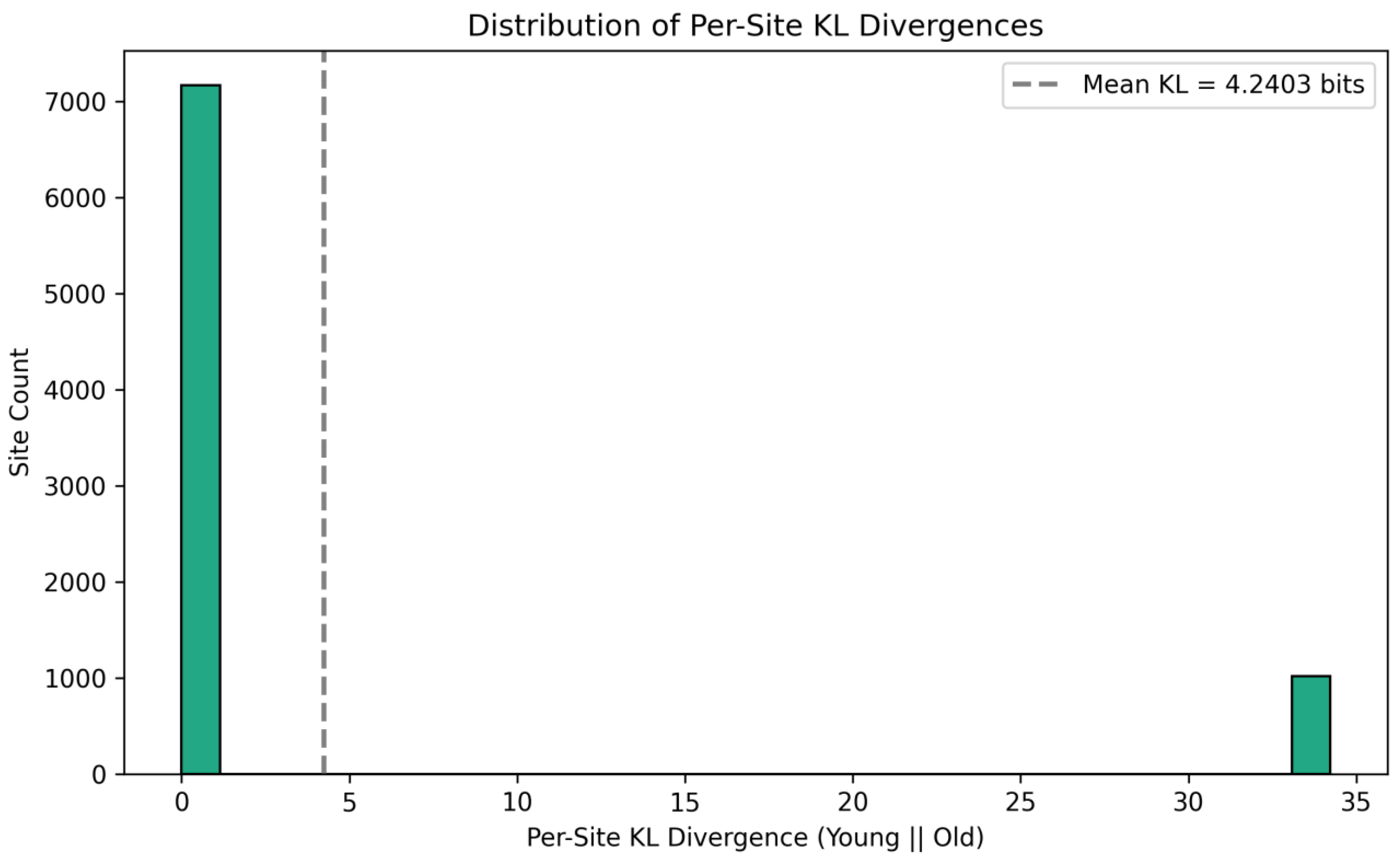

3.5. Kullback-Liebler Divergence: Quantifying the Geometric Difference Between Redox State Distributions in Information Space

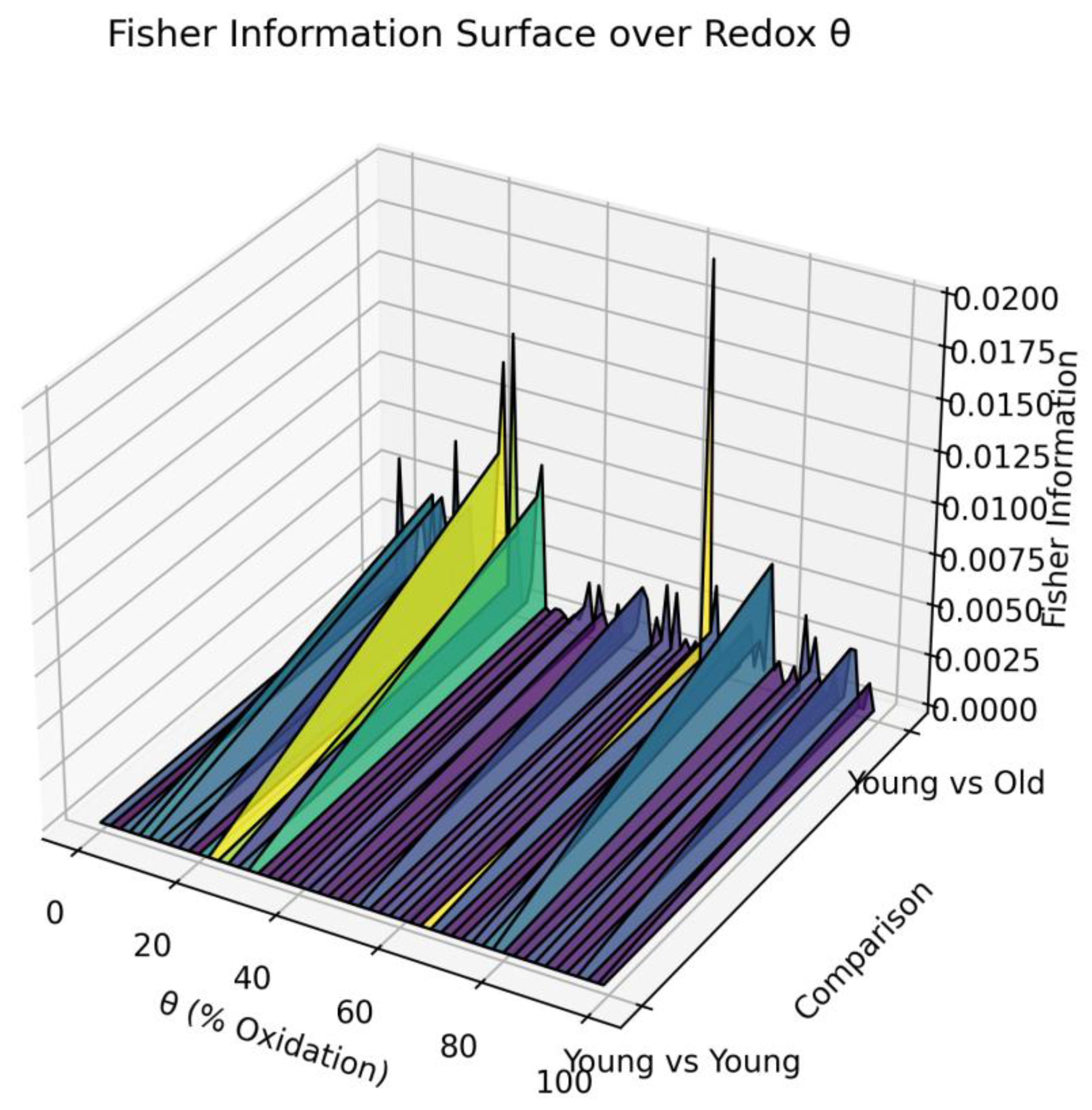

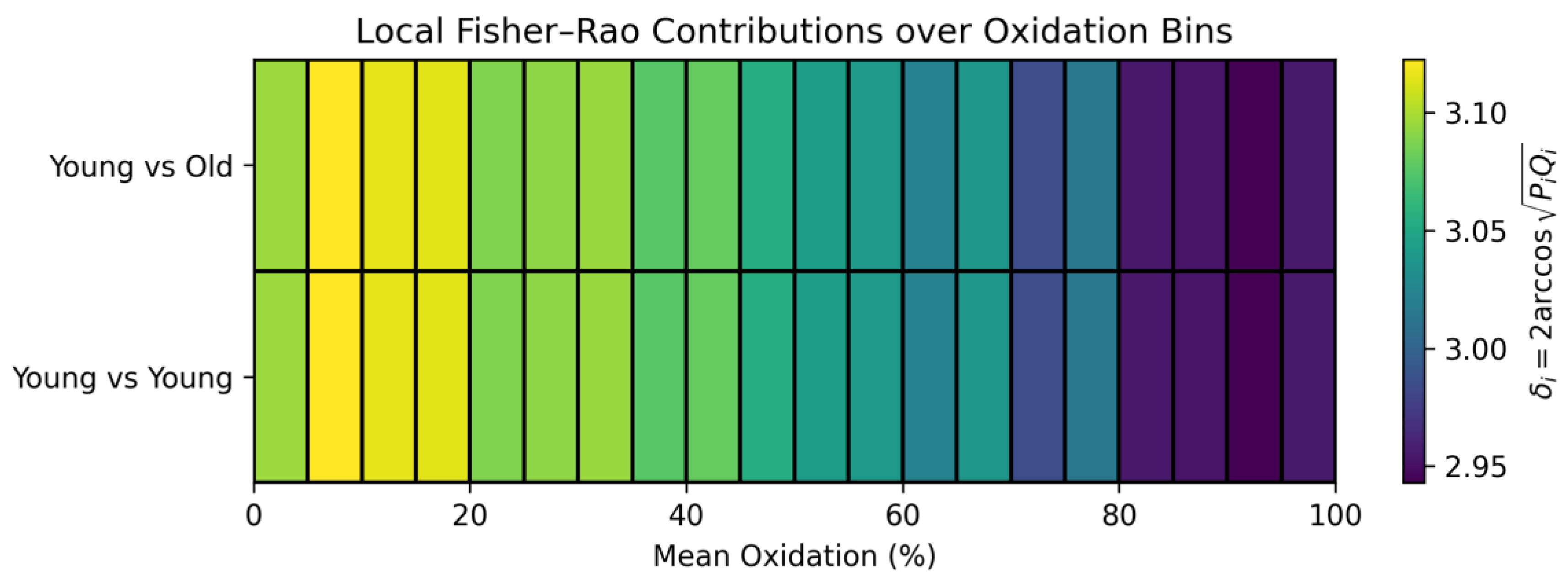

3.6. Fisher Information Metric: Quantifying the Geometry of Curved Redox State Manifolds

3.7. Fisher-Rao Distance: Quantifying the Distance Between Curved Redox Manifolds

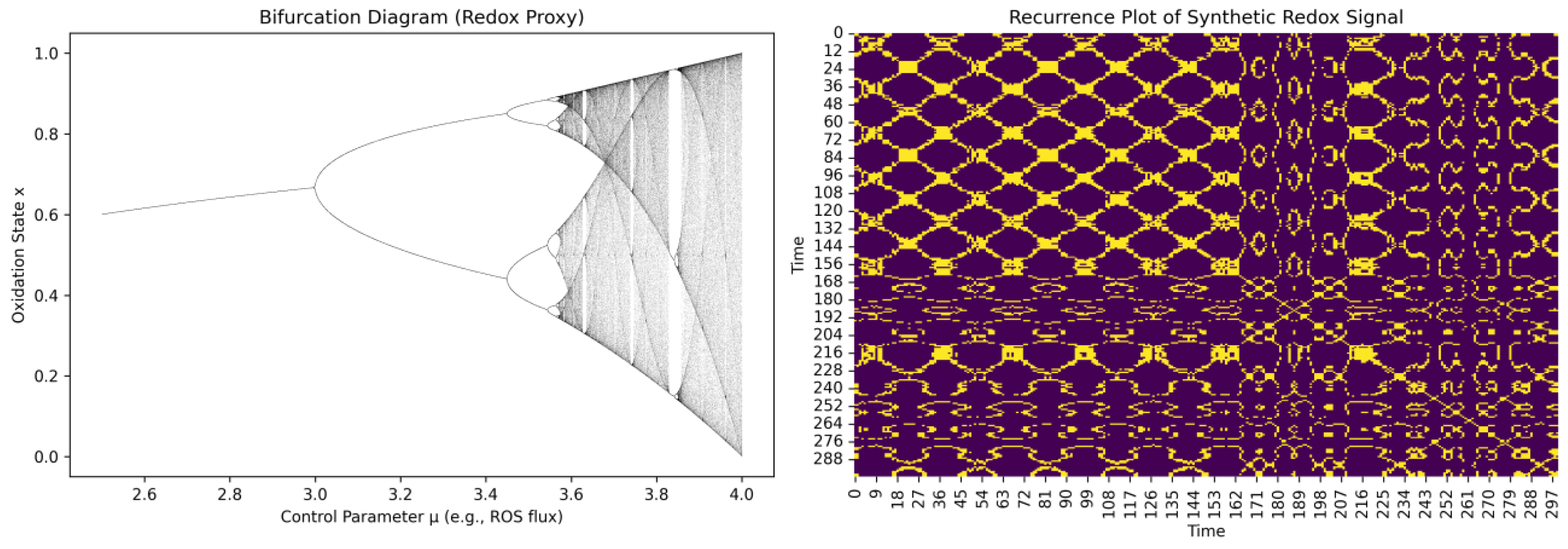

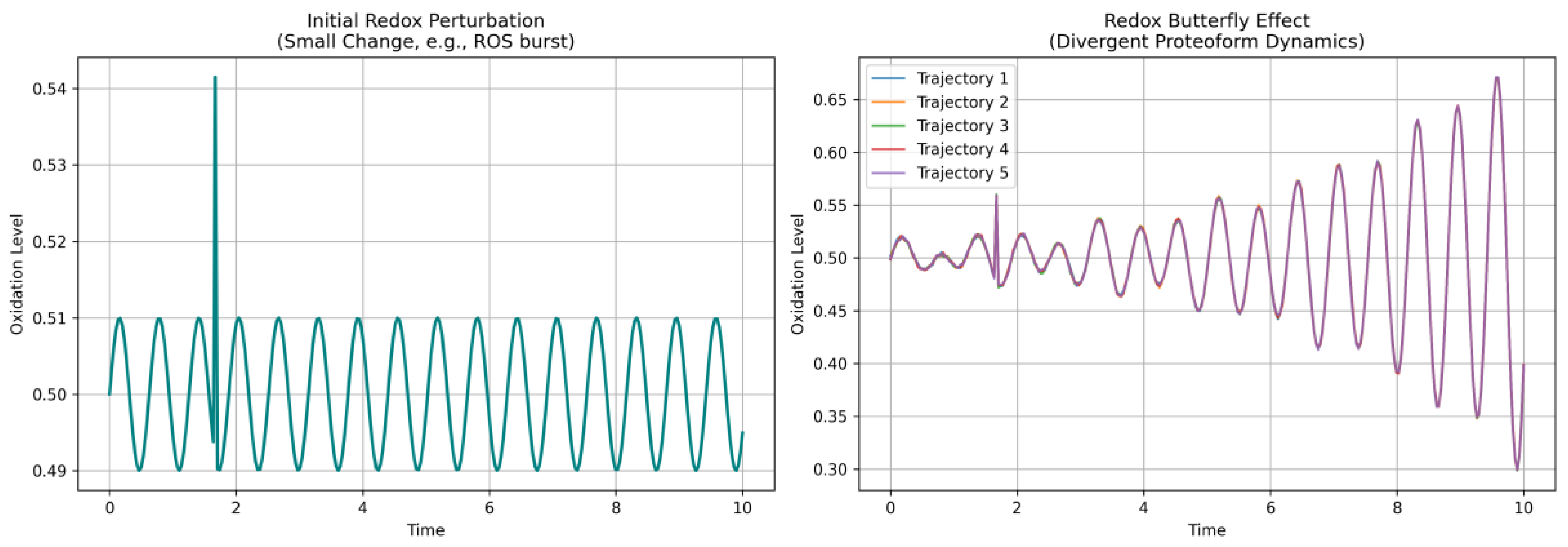

3.8. Distinguishing Order from Chaos in Time-Resolved Redox Dynamics

- Ordered—following predictable or quasi-linear dynamics.

- Chaotic—diverging over time due to small differences in the initial conditions.

- Hybrid—a cysteine redox system where orderly and chaotic behaviors coexist either across different subsystems, within different time windows, or as structured chaos near low-dimensional attractors.

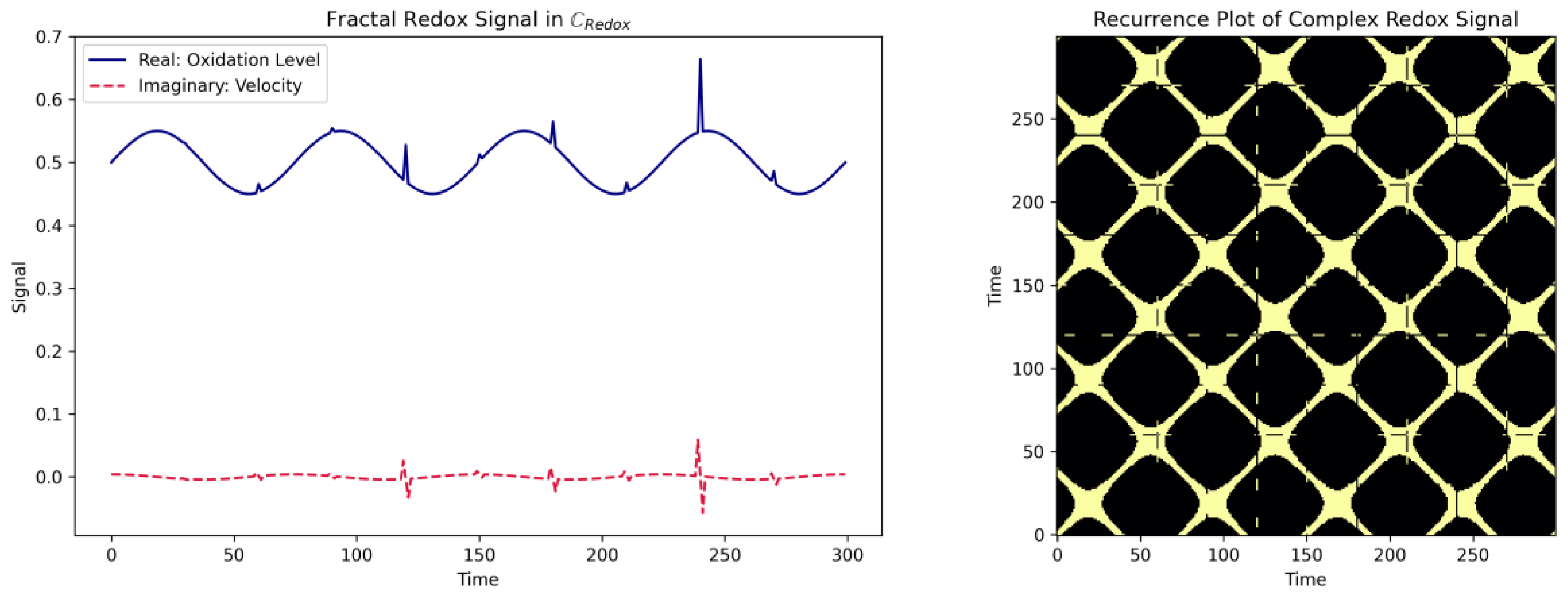

3.9. Fractal Geometry: Quantifying Scale-Invariant Self-Similar Cysteine Redox State Patterns

4. Discussion

- Information theory enables the oxidation state of a peptide to be analyzed and interpreted as an encoded signal, compressible or not, with measurable entropy. The more irregular, the less compressible—and paradoxically, the more information it may carry. By quantifying these dynamics across timepoints and conditions, one can begin to see that redox states are not random variables—they are deterministic signals with memory, unfolding on a nonlinear manifold.

- Chaos theory offers the interpretive lens. Small redox changes can produce outsized shifts in oxidation of peptides. This sensitivity to initial conditions defines the redox butterfly effect. Peptide-level oxidation patterns form trajectories—not just in time, but across a complex redox phase space, where certain states act as strange oxi-attractor. With tools like approximate entropy, recurrence quantification, and fractal dimension analysis, these structures are now computationally accessible, even at the peptide level.

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sies, H.; Mailloux, R.J.; Jakob, U. Fundamentals of Redox Regulation in Biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, L.J.; Perkins, M.V.; Chalker, J.M. Chemical Methods for Mapping Cysteine Oxidation. Chem Soc Rev 2017, 47, 231–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, C.E.; Carroll, K.S. Cysteine-Mediated Redox Signaling: Chemistry, Biology, and Tools for Discovery. Chem Rev 2013, 113, 4633–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, N.S.; Evans, P.; Martínez-Acedo, P.; Marino, S.M.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Carroll, K.S.; Ischiropoulos, H. Site-Specific Proteomic Mapping Identifies Selectively Modified Regulatory Cysteine Residues in Functionally Distinct Protein Networks. Chem Biol 2015, 22, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensien, M.; Pappenheim, F.R. von; Funk, L.-M.; Kloskowski, P.; Curth, U.; Diederichsen, U.; Uranga, J.; Ye, J.; Fang, P.; Pan, K.-T.; et al. A Lysine–Cysteine Redox Switch with an NOS Bridge Regulates Enzyme Function. Nature 2021, 593, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Z.-H.; Chen, Z.-N.; Bian, H.; Yang, X.; Lu, H.-Y.; Lin, P.; Chen, X.; et al. Cysteine Carboxyethylation Generates Neoantigens to Induce HLA-Restricted Autoimmunity. Science 2023, 379, eabg2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.; Zou, Y.; Zhai, X.; Xiao, N.; Liu, W.; et al. ROS Regulated Reversible Protein Phase Separation Synchronizes Plant Flowering. Nat Chem Biol 2021, 17, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox Metabolism: ROS as Specific Molecular Regulators of Cell Signaling and Function. Mol Cell 2021, 81, 3691–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, S.; Long, M.J.C.; Poganik, J.R.; Aye, Y. Redox Signaling by Reactive Electrophiles and Oxidants. Chem Rev 2018, 118, 8798–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P.; Sies, H. The Redox Code. Antioxid Redox Sign 2015, 23, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P. Redox Organization of Living Systems. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 217, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feelisch, M.; Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Santolini, J.; Wootton, S.A.; Jackson, A.A. Systems Redox Biology in Health and Disease. EXCLI J. 2022, 21, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.J.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Qian, W.-J. Stoichiometric Thiol Redox Proteomics for Quantifying Cellular Responses to Perturbations. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gluth, A.; Zhang, T.; Qian, W. Thiol Redox Proteomics: Characterization of Thiol-based Post-translational Modifications. Proteomics 2023, e2200194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Sakellariou, G.K.; Husi, H.; McDonagh, B. Proteomic Strategies to Unravel Age-Related Redox Signalling Defects in Skeletal Muscle. Free Radical Bio Med 2019, 132, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ha, S.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, K. ROSics: Chemistry and Proteomics of Cysteine Modifications in Redox Biology. Mass Spectrom Rev 2015, 34, 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, N.; Chouchani, E.T. A New Era of Cysteine Proteomics – Technological Advances in Thiol Biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 79, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Schweppe, D.K.; Huttlin, E.L.; Yu, Q.; Heppner, D.E.; Li, J.; Long, J.; Mills, E.L.; Szpyt, J.; et al. A Quantitative Tissue-Specific Landscape of Protein Redox Regulation during Aging. Cell 2020, 180, 968–983.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Day, N.J.; Feng, S.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Lin, T.-D.; Paurus, V.L.; Monroe, M.E.; Moore, R.J.; Yang, B.; Xian, M.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Direct Detection of Multiple Types of Protein Thiol Modifications in Pancreatic Beta Cells under Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Redox Biol 2021, 46, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.J.; Kelly, S.S.; Lui, L.; Mansfield, T.A.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Trejo, J.B.; Sagendorf, T.J.; Attah, I.K.; Moore, R.J.; Douglas, C.M.; et al. Signatures of Cysteine Oxidation on Muscle Structural and Contractile Proteins Are Associated with Physical Performance and Muscle Function in Older Adults: Study of Muscle, Mobility and Aging (SOMMA). Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Staes, A.; Impens, F.; Demichev, V.; Breusegem, F.V.; Gevaert, K.; Willems, P. CysQuant: Simultaneous Quantification of Cysteine Oxidation and Protein Abundance Using Data Dependent or Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjo, S.I.; Melo, M.N.; Loureiro, L.R.; Sabala, L.; Castanheira, P.; Grãos, M.; Manadas, B. OxSWATH: An Integrative Method for a Comprehensive Redox-Centered Analysis Combined with a Generic Differential Proteomics Screening. Redox Biol. 2019, 22, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behring, J.B.; Post, S. van der; Mooradian, A.D.; Egan, M.J.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Clements, J.L.; Bowman, G.R.; Held, J.M. Spatial and Temporal Alterations in Protein Structure by EGF Regulate Cryptic Cysteine Oxidation. Sci Signal 2020, 13, eaay7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, J.M. Redox Systems Biology: Harnessing the Sentinels of the Cysteine Redoxome. Antioxid Redox Sign 2020, 32, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, J.M.; Danielson, S.R.; Behring, J.B.; Atsriku, C.; Britton, D.J.; Puckett, R.L.; Schilling, B.; Campisi, J.; Benz, C.C.; Gibson, B.W. Targeted Quantitation of Site-Specific Cysteine Oxidation in Endogenous Proteins Using a Differential Alkylation and Multiple Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry Approach. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010, 9, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.C. Bioenergetic Myths of Energy Transduction in Eukaryotic Cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1402910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N. 50 Shades of Oxidative Stress: A State-Specific Cysteine Redox Pattern Hypothesis. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Cochemé, H.M. Redox Regulation of the Insulin Signalling Pathway. Redox Biol 2021, 42, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Eustress: On Constant Alert for Redox Homeostasis. Redox Biol 2021, 41, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devant, P.; Boršić, E.; Ngwa, E.M.; Xiao, H.; Chouchani, E.T.; Thiagarajah, J.R.; Hafner-Bratkovič, I.; Evavold, C.L.; Kagan, J.C. Gasdermin D Pore-Forming Activity Is Redox-Sensitive. Cell Reports 2023, 42, 112008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N.; Fiorello, M.L.; Bailey, D.M. 13 Reasons Why the Brain Is Susceptible to Oxidative Stress. Redox Biol 2018, 15, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Dynamics of Intracellular and Intercellular Redox Communication. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M.B. ROS as Signalling Molecules: Mechanisms That Generate Specificity in ROS Homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Hampton, M.B. Thiol Chemistry and Specificity in Redox Signaling. Free Radical Bio Med 2008, 45, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; 2015; Vol. 5th Edition.

- Murphy, M.P.; Bayir, H.; Belousov, V.; Chang, C.J.; Davies, K.J.A.; Davies, M.J.; Dick, T.P.; Finkel, T.; Forman, H.J.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.; et al. Guidelines for Measuring Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Damage in Cells and in Vivo. Nat Metabolism 2022, 4, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Understanding Mechanisms of Antioxidant Action in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; Holmgren, A.; Larsson, N.-G.; Halliwell, B.; Chang, C.J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Rhee, S.G.; Thornalley, P.J.; Partridge, L.; Gems, D.; et al. Unraveling the Biological Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Metab 2011, 13, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Belousov, V.V.; Chandel, N.S.; Davies, M.J.; Jones, D.P.; Mann, G.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Winterbourn, C. Defining Roles of Specific Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Cell Biology and Physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as Pleiotropic Physiological Signalling Agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Hydrogen Peroxide as a Central Redox Signaling Molecule in Physiological Oxidative Stress: Oxidative Eustress. Redox Biol 2017, 11, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosmann, B.; Hajieva, P. Probing the Role of Cysteine Thiyl Radicals in Biology: Eminently Dangerous, Difficult to Scavenge. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Cobley, J.N.; Paschalis, V.; Veskoukis, A.S.; Theodorou, A.A.; Kyparos, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Going Retro: Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Modern Redox Biology. Free Radical Bio Med 2016, 98, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Husi, H. Immunological Techniques to Assess Protein Thiol Redox State: Opportunities, Challenges and Solutions. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial ROS Production in Assisted Reproduction: The Known, the Unknown, and the Intriguing. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Cobley, J.N.; Paschalis, V.; Veskoukis, A.S.; Theodorou, A.A.; Kyparos, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Principles for Integrating Reactive Species into in Vivo Biological Processes: Examples from Exercise Physiology. Cell Signal 2016, 28, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Davison, G.W. Ten “Cheat Codes” for Measuring Oxidative Stress in Humans. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.; Foster, K.R.; Uphoff, S. Chaos in a Bacterial Stress Response. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 5404–5414.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N. Oxiforms: Unique Cysteine Residue- and Chemotype-specified Chemical Combinations Can Produce Functionally-distinct Proteoforms. Bioessays 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Schmidt, C.A. Computational Analysis of Human Cysteine Redox Proteoforms Reveals Novel Insights. [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, P.J.; Bórquez, D.A. Expanded Bioinformatic Analysis of Oximouse Dataset Reveals Key Putative Processes Involved in Brain Aging and Cognitive Decline. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 207, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ming, H.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Dong, J.; Du, Z.; Huang, C. Redox Regulation: Mechanisms, Biology and Therapeutic Targets in Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, H.; Andrews, K.H.; Bergersen, K.V.; Ofori, S.; Yu, F.; Shikwana, F.; Arbing, M.A.; Boatner, L.M.; Villanueva, M.; Ung, N.; et al. Chemoproteogenomic Stratification of the Missense Variant Cysteinome. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Boatner, L.M.; Cui, L.; Tontonoz, P.J.; Backus, K.M. Defining the Cell Surface Cysteinome Using Two-Step Enrichment Proteomics. JACS Au 2023, 3, 3506–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, N.R.; Polasky, D.A.; Shikwana, F.; Ofori, S.; Yan, T.; Geiszler, D.J.; Leprevost, F. da V.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Backus, K.M. Solid-Phase Compatible Silane-Based Cleavable Linker Enables Custom Isobaric Quantitative Chemoproteomics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21303–21318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, H.S.; Yan, T.; Yu, F.; Sun, A.W.; Villanueva, M.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Backus, K.M. SP3-Enabled Rapid and High Coverage Chemoproteomic Identification of Cell-State–Dependent Redox-Sensitive Cysteines. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2022, 21, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Desai, H.S.; Boatner, L.M.; Yen, S.L.; Cao, J.; Palafox, M.F.; Jami-Alahmadi, Y.; Backus, K.M. SP3-FAIMS Chemoproteomics for High-Coverage Profiling of the Human Cysteinome**. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatner, L.M.; Palafox, M.F.; Schweppe, D.K.; Backus, K.M. CysDB: A Human Cysteine Database Based on Experimental Quantitative Chemoproteomics. Cell Chem Biol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Palmer, A.B.; Geiszler, D.J.; Polasky, D.A.; Boatner, L.M.; Burton, N.R.; Armenta, E.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Backus, K.M. Enhancing Cysteine Chemoproteomic Coverage through Systematic Assessment of Click Chemistry Product Fragmentation. Anal Chem 2022, 94, 3800–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Petersen, M.H.; Ibañez-Vea, M.; Lassen, P.S.; Larsen, M.R.; Palmisano, G. Simultaneous Enrichment of Cysteine-Containing Peptides and Phosphopeptides Using a Cysteine-Specific Phosphonate Adaptable Tag (CysPAT) in Combination with Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Chromatography*. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 15, 3282–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichert, L.I.; Gehrke, F.; Gudiseva, H.V.; Blackwell, T.; Ilbert, M.; Walker, A.K.; Strahler, J.R.; Andrews, P.C.; Jakob, U. Quantifying Changes in the Thiol Redox Proteome upon Oxidative Stress in Vivo. Proc National Acad Sci 2008, 105, 8197–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Methner, C.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Logan, A.; Pell, V.R.; Ding, S.; James, A.M.; Cochemé, H.M.; Reinhold, J.; Lilley, K.S.; et al. Cardioprotection by S-Nitrosation of a Cysteine Switch on Mitochondrial Complex I. Nat Med 2013, 19, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; James, A.M.; Fearnley, I.M.; Lilley, K.S.; Murphy, M.P. Proteomic Approaches to the Characterization of Protein Thiol Modification. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2011, 15, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Mann, M. A Beginner’s Guide to Mass Spectrometry–Based Proteomics. Biochem. 2020, 42, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Nature 2003, 422, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, H.; Mann, M. The Abc’s (and Xyz’s) of Peptide Sequencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2004, 5, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Aebersold, R.; Baker, M.S.; Bian, X.; Bo, X.; Chan, D.W.; Chang, C.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.-J.; et al. π-HuB: The Proteomic Navigator of the Human Body. Nature 2024, 636, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Steen, J.A.; Mann, M. Mass-Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: From Single Cells to Clinical Applications. Nature 2025, 638, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass-Spectrometric Exploration of Proteome Structure and Function. Nature 2016, 537, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized p.p.b.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: Neural Networks and Interference Correction Enable Deep Proteome Coverage in High Throughput. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, R.; Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Lang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shui, W. Benchmarking Commonly Used Software Suites and Analysis Workflows for DIA Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, C.S.; Eagling, B.D.; Driscoll, S.R.E.; Rohwer, J.M. Quantitative Measures for Redox Signaling. Free Radical Bio Med 2016, 96, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, G.R.; Wagner, B.A.; Rodgers, V.G.J. Quantitative Redox Biology: An Approach to Understand the Role of Reactive Species in Defining the Cellular Redox Environment. Cell Biochem Biophys 2013, 67, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Moult, P.R.; Burniston, J.G.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. Exercise Improves Mitochondrial and Redox-Regulated Stress Responses in the Elderly: Better Late than Never! Biogerontology 2015, 16, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Sakellariou, G.K.; Owens, D.J.; Murray, S.; Waldron, S.; Gregson, W.; Fraser, W.D.; Burniston, J.G.; Iwanejko, L.A.; McArdle, A.; et al. Lifelong Training Preserves Some Redox-Regulated Adaptive Responses after an Acute Exercise Stimulus in Aged Human Skeletal Muscle. Free Radical Bio Med 2014, 70, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stretton, C.; Pugh, J.N.; McDonagh, B.; McArdle, A.; Close, G.L.; Jackson, M.J. 2-Cys Peroxiredoxin Oxidation in Response to Hydrogen Peroxide and Contractile Activity in Skeletal Muscle: A Novel Insight into Exercise-Induced Redox Signalling? Free Radical Bio Med 2020, 160, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, J.N.; Stretton, C.; McDonagh, B.; Brownridge, P.; McArdle, A.; Jackson, M.J.; Close, G.L. Exercise Stress Leads to an Acute Loss of Mitochondrial Proteins and Disruption of Redox Control in Skeletal Muscle of Older Subjects: An Underlying Decrease in Resilience with Aging? Free Radical Bio Med 2021, 177, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, B.; Sakellariou, G.K.; Smith, N.T.; Brownridge, P.; Jackson, M.J. Differential Cysteine Labeling and Global Label-Free Proteomics Reveals an Altered Metabolic State in Skeletal Muscle Aging. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5008–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinn, M. Phantom Oscillations in Principal Component Analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2311420120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H. Computational Systems Biology. Nature 2002, 420, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, L.H.; Hopfield, J.J.; Leibler, S.; Murray, A.W. From Molecular to Modular Cell Biology. Nature 1999, 402, C47–C52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Kelleher, N.L.; Linial, M.; Goodlett, D.; Langridge-Smith, P.; Goo, Y.A.; Safford, G.; Bonilla*, L.; Kruppa, G.; Zubarev, R.; et al. Proteoform: A Single Term Describing Protein Complexity. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Kelleher, N.L. Proteoforms as the next Proteomics Currency. Science 2018, 359, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, K.; Andonovski, M.; Coorssen, J.R. Proteomes Are of Proteoforms: Embracing the Complexity. Proteomes 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coorssen, J.R.; Padula, M.P. Proteomics—The State of the Field: The Definition and Analysis of Proteomes Should Be Based in Reality, Not Convenience. Proteomes 2024, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, J.A.; Bohländer, P.; Dai, M.; Filius, M.; Howard, C.J.; Kooten, X.F. van; Ohayon, S.; Pomorski, A.; Schmid, S.; Aksimentiev, A.; et al. The Emerging Landscape of Single-Molecule Protein Sequencing Technologies. Nat Methods 2021, 18, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N. Exploring the Unmapped Cysteine Redox Proteoform Landscape. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkies, S.L.; Lind, D.J.; Pillay, C.S. Emerging Trends for the Regulation of Thiol-Based Redox Transcription Factor Pathways. Biochemistry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquel, B.; Kavčič, B.; Aspert, T.; Matifas, A.; Kuehn, A.; Zhuravlev, A.; Byckov, E.; Morgan, B.; Julou, T.; Charvin, G. A Trade-off between Stress Resistance and Tolerance Underlies the Adaptive Response to Hydrogen Peroxide. Cell Syst. 2025, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, D.J.; Naidoo, K.C.; Tomalin, L.E.; Rohwer, J.M.; Veal, E.A.; Pillay, C.S. Quantifying Redox Transcription Factor Dynamics as a Tool to Investigate Redox Signalling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 218, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Thomas, P.M.; Shortreed, M.R.; Schaffer, L.V.; Fellers, R.T.; LeDuc, R.D.; Tucholski, T.; Ge, Y.; Agar, J.N.; Anderson, L.C.; et al. A Five-Level Classification System for Proteoform Identifications. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 939–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, C.; Martínez-Bartolomé, S.; Montgomery, M.; Pankow, S.; Hulleman, J.D.; Kelly, J.W.; Yates, J.R. Deducing the Presence of Proteins and Proteoforms in Quantitative Proteomics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Agar, J.N.; Amster, I.J.; Baker, M.S.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Boja, E.S.; Costello, C.E.; Cravatt, B.F.; Fenselau, C.; Garcia, B.A.; et al. How Many Human Proteoforms Are There? Nat Chem Biol 2018, 14, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V. Inside the Chase after Those Elusive Proteoforms. Nat. Methods 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bludau, I.; Aebersold, R. Proteomic and Interactomic Insights into the Molecular Basis of Cell Functional Diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Schmidt, C.A. The Nonlinear Cysteine Redox Dynamics in the I-Space: A Proteoform-Centric Theory of Redox Regulation. Redox Biol. 2025, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, R.E.; Roth, D.; Winther, J.R. Quantifying the Global Cellular Thiol–Disulfide Status. Proc National Acad Sci 2009, 106, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Noble, A.; Guille, M. Cleland Immunoblotting Unmasks Unexpected Cysteine Redox Proteoforms. [CrossRef]

- Melani, R.D.; Gerbasi, V.R.; Anderson, L.C.; Sikora, J.W.; Toby, T.K.; Hutton, J.E.; Butcher, D.S.; Negrão, F.; Seckler, H.S.; Srzentić, K.; et al. The Blood Proteoform Atlas: A Reference Map of Proteoforms in Human Hematopoietic Cells. Science 2022, 375, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.M.; Agar, J.N.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Danis, P.O.; Ge, Y.; Loo, J.A.; Paša-Tolić, L.; Tsybin, Y.O.; Kelleher, N.L.; Proteomics, T.C. for T.-D. The Human Proteoform Project: Defining the Human Proteome. Sci Adv 2021, 7, eabk0734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.S.; Loo, J.A.; Tsybin, Y.O.; Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Agar, J.N.; Paša-Tolić, L.; Smith, L.M.; Ge, Y. Top-down Proteomics. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnum-Johnson, K.E.; Conrads, T.P.; Drake, R.R.; Herr, A.E.; Iyengar, R.; Kelly, R.T.; Lundberg, E.; MacCoss, M.J.; Naba, A.; Nolan, G.P.; et al. New Views of Old Proteins: Clarifying the Enigmatic Proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 2022, 21, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Hollas, M.A.R.; Pla, I.; Rubakhin, S.; Butun, F.A.; Greer, J.B.; Early, B.P.; Fellers, R.T.; Caldwell, M.A.; Sweedler, J.V.; et al. Proteoform Profiling of Endogenous Single Cells from Rat Hippocampus at Scale. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plubell, D.L.; Käll, L.; Webb-Robertson, B.-J.; Bramer, L.M.; Ives, A.; Kelleher, N.L.; Smith, L.M.; Montine, T.J.; Wu, C.C.; MacCoss, M.J. Putting Humpty Dumpty Back Together Again: What Does Protein Quantification Mean in Bottom-Up Proteomics? J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, P.E.; Fu, L.; Hampton, M.B.; Winterbourn, C.C. Redox Proteomic Analysis of H2O2 -Treated Jurkat Cells and Effects of Bicarbonate and Knockout of Peroxiredoxins 1 and 2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 227, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivancevic, V.G.; Ivancevic, T.T. Ricci Flow and Nonlinear Reaction–Diffusion Systems in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2011, 65, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, D.E.; Dustin, C.M.; Liao, C.; Hristova, M.; Veith, C.; Little, A.C.; Ahlers, B.A.; White, S.L.; Deng, B.; Lam, Y.-W.; et al. Direct Cysteine Sulfenylation Drives Activation of the Src Kinase. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, R.; Qian, J.; Yin, L.; Bechtold, E.; King, S.B.; Poole, L.B.; Paek, E.; Tsang, A.W.; Furdui, C.M. Isoform-Specific Regulation of Akt by PDGF-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species. Proc National Acad Sci 2011, 108, 10550–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Burchfield, J.G.; Yang, P.; Humphrey, S.J.; Yang, G.; Francis, D.; Yasmin, S.; Shin, S.-Y.; Norris, D.M.; Kearney, A.L.; et al. Global Redox Proteome and Phosphoproteome Analysis Reveals Redox Switch in Akt. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ali, M.Y.; Chong, H.B.; Tien, P.-C.; Woods, J.; Noble, C.; Vornbäumen, T.; Ordulu, Z.; Possemato, A.P.; Harry, S.; et al. Oxidation of Retromer Complex Controls Mitochondrial Translation. Nature 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Co, H.K.; Lee, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, S. Multistability Maintains Redox Homeostasis in Human Cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021, 17, e10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A. A New Basic Theorem of Information Theory. Trans. IRE Prof. Group Inf. Theory 1954, 4, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, A.V.W.; Guy, G.W.; Bell, J.D. The Quantum Mitochondrion and Optimal Health. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltermann, C.; Klipp, E. Information Theory Based Approaches to Cellular Signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 2011, 1810, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.R.; Tian, X.; Sinclair, D.A. The Information Theory of Aging. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakoff, D. Bayes Offers a “New” Way to Make Sense of Numbers. Science 1999, 286, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, J.P.; Young, K. Inferring Statistical Complexity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 63, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, J. Chaos: Making the New Science; Penguin Books, 2008; ISBN 9780143113454.

- Lorenz, E.N. Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set off a Tornado in Texas. In Proceedings of the merican Association for the Advancement of Science; Washington DC; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum, M.J. Quantitative Universality for a Class of Nonlinear Transformations. J. Stat. Phys. 1978, 19, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals in Physics: Squig Clusters, Diffusions, Fractal Measures, and the Unicity of Fractal Dimensionality. J. Stat. Phys. 1984, 34, 895–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractal Geometry: What Is It, and What Does It Do? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 423, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C.; Halliwell, B. Mini-Review: Oxidative Stress, Redox Stress or Redox Success? Biochem Bioph Res Co 2018, 502, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Biochemistry of Oxidative Stress. Biochemical Society Transactions 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, C.E.; Truong, T.H.; Garcia, F.J.; Homann, A.; Gupta, V.; Leonard, S.E.; Carroll, K.S. Peroxide-Dependent Sulfenylation of the EGFR Catalytic Site Enhances Kinase Activity. Nat Chem Biol 2012, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.-M.; Chandler, J.D.; Jones, D.P. The Cysteine Proteome. Free Radical Bio Med 2015, 84, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.-M.; Roede, J.R.; Walker, D.I.; Duong, D.M.; Seyfried, N.T.; Orr, M.; Liang, Y.; Pennell, K.D.; Jones, D.P. Selective Targeting of the Cysteine Proteome by Thioredoxin and Glutathione Redox Systems*. Mol Cell Proteomics 2013, 12, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moan, N.L.; Clement, G.; Maout, S.L.; Tacnet, F.; Toledano, M.B. The Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Proteome of Oxidized Protein Thiols CONTRASTED FUNCTIONS FOR THE THIOREDOXIN AND GLUTATHIONE PATHWAYS*. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 10420–10430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reest, J. van der; Lilla, S.; Zheng, L.; Zanivan, S.; Gottlieb, E. Proteome-Wide Analysis of Cysteine Oxidation Reveals Metabolic Sensitivity to Redox Stress. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Close, G.L.; Bailey, D.M.; Davison, G.W. Exercise Redox Biochemistry: Conceptual, Methodological and Technical Recommendations. Redox Biol 2017, 12, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N. Oxidative Stress. 2020, 447–462. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Davison, G.W. Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology. 2022, 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, James.N.; Davison, G.W. Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology; CRC Press, 2022; ISBN 9781003051619.

- Cobley, J.N.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Malone, J.K. The Basic Chemistry of Exercise-Induced DNA Oxidation: Oxidative Damage, Redox Signaling, and Their Interplay. Front Physiol 2015, 6, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, M.G.; Margaritelis, N.V. Free Radicals and Antioxidants: Appealing to Magic. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, M.; Margaritelis, N.; Matsakas, A. Quantitative Redox Biology of Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Chatzinikolaou, A.N.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Vrabas, I.S.; Kyparos, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. The Redox Signal: A Physiological Perspective. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Cobley, J.N.; Nastos, G.G.; Papanikolaou, K.; Bailey, S.J.; Kritsiligkou, P.; Nikolaidis, M.G. “Unlocking Athletic Potential: Exploring Exercise Physiology from Mechanisms to Performance”: Evidence-Based Sports Supplements: A Redox Analysis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M.; Forman, H.J. Redox Homeostasis: The Golden Mean of Healthy Living. Redox Biol 2016, 8, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, H.S.; Real, C.; Cyrne, L.; Soares, H.; Antunes, F. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing, Signaling and Regulation of Transcription Factors. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F.; Brito, P.M. Quantitative Biology of Hydrogen Peroxide Signaling. Redox Biol 2017, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Lv, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Identification of the Redox-Stress Signaling Threshold (RST): Increased RST Helps to Delay Aging in C. Elegans. Free Radical Bio Med 2021, 178, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative Stress. Annu Rev Biochem 2016, 86, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: A Concept in Redox Biology and Medicine. Redox Biol 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: Concept and Some Practical Aspects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.; Aon, M.A.; Cortassa, S. Why Homeodynamics, Not Homeostasis? Sci. World J. 2001, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Disease: Promise and Limitations of Antioxidant Therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, E.L.; Gawel, J.M.; Aksentijević, D.; Cochemé, H.M.; Stewart, T.S.; Shchepinova, M.M.; Qiang, H.; Prime, T.A.; Bright, T.P.; James, A.M.; et al. Selective Superoxide Generation within Mitochondria by the Targeted Redox Cycler MitoParaquat. Free Radical Bio Med 2015, 89, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booty, L.M.; Gawel, J.M.; Cvetko, F.; Caldwell, S.T.; Hall, A.R.; Mulvey, J.F.; James, A.M.; Hinchy, E.C.; Prime, T.A.; Arndt, S.; et al. Selective Disruption of Mitochondrial Thiol Redox State in Cells and In Vivo. Cell Chem Biol 2019, 26, 449–461.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidlauskaite, E.; Gibson, J.W.; Megson, I.L.; Whitfield, P.D.; Tovmasyan, A.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Murphy, M.P.; Moult, P.R.; Cobley, J.N. Mitochondrial ROS Cause Motor Deficits Induced by Synaptic Inactivity: Implications for Synapse Pruning. Redox Biol 2018, 16, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How Mitochondria Produce Reactive Oxygen Species. Biochem J 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-S.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Woo, H.A.; Rhee, S.G. Circadian Rhythm of Hyperoxidized Peroxiredoxin II Is Determined by Hemoglobin Autoxidation and the 20S Proteasome in Red Blood Cells. Proc National Acad Sci 2014, 111, 12043–12048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.S.; Ooijen, G. van; Dixon, L.E.; Troein, C.; Corellou, F.; Bouget, F.-Y.; Reddy, A.B.; Millar, A.J. Circadian Rhythms Persist without Transcription in a Eukaryote. Nature 2011, 469, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.-F.; Li, X.-K.; Li, W.-Q.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Fu, J.-Q.; Cui, S.-S.; Qu, J.-H.; Zhao, X.; et al. Diurnal Oscillations of Endogenous H2O2 Sustained by P66Shc Regulate Circadian Clocks. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, P.S.; Yahya, G.; Zimmermann, J.; Mai, M.; Mergel, S.; Mühlhaus, T.; Storchova, Z.; Morgan, B. Peroxiredoxins Couple Metabolism and Cell Division in an Ultradian Cycle. Nat Chem Biol 2021, 17, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazopoulou, D.; Knoefler, D.; Zheng, Y.; Ulrich, K.; Oleson, B.J.; Xie, L.; Kim, M.; Kaufmann, A.; Lee, Y.-T.; Dou, Y.; et al. Developmental ROS Individualizes Organismal Stress Resistance and Lifespan. Nature 2019, 576, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N. Synapse Pruning: Mitochondrial ROS with Their Hands on the Shears. Bioessays 2018, 40, 1800031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Wilson, M.H.; Wright, M.H. Redox Regulation of Cell Proliferation: Bioinformatics and Redox Proteomics Approaches to Identify Redox-Sensitive Cell Cycle Regulators. Free Radical Bio Med 2018, 122, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henau, S.D.; Pagès-Gallego, M.; Pannekoek, W.-J.; Dansen, T.B. Mitochondria-Derived H2O2 Promotes Symmetry Breaking of the C. Elegans Zygote. Dev Cell 2020, 53, 263–271.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.; Noble, A.; Bessell, R.; Guille, M.; Husi, H. Reversible Thiol Oxidation Inhibits the Mitochondrial ATP Synthase in Xenopus Laevis Oocytes. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LYAPUNOV, A.M. The General Problem of the Stability of Motion. Int. J. Control 1992, 55, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.; Swift, J.B.; Swinney, H.L.; Vastano, J.A. Determining Lyapunov Exponents from a Time Series. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 16, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, J.-P.; Ruelle, D. Ergodic Theory of Chaos and Strange Attractors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1985, 57, 617–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, S.M. Approximate Entropy as a Measure of System Complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991, 88, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, P.; Procaccia, I. Characterization of Strange Attractors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 50, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, N.; Romano, M.C.; Thiel, M.; Kurths, J. Recurrence Plots for the Analysis of Complex Systems. Phys. Rep. 2007, 438, 237–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirova, D.G.; Judasova, K.; Vorhauser, J.; Zerjatke, T.; Leung, J.K.; Glauche, I.; Mansfeld, J. A ROS-Dependent Mechanism Promotes CDK2 Phosphorylation to Drive Progression through S Phase. Dev Cell 2022, 57, 1712–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorhauser, J.; Roumeliotis, T.I.; Leung, J.K.; Coupe, D.; Yu, L.; Böhlig, K.; Nadler, A.; Choudhary, J.S.; Mansfeld, J. Cell Cycle-Dependent S-Sulfenyl Proteomics Uncover a Redox Switch in P21-CDK Feedback Governing the Proliferation-Senescence Decision. bioRxiv, 2024; 2024.09.14.613007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez-Olguín, C.; Gallero, S.; Reddy, A.; Persson, K.W.; Schlabs, F.L.; Voldstedlund, C.T.; Valentinaviciute, G.; Meneses-Valdés, R.; Sigvardsen, C.M.; Kiens, B.; et al. Revisiting Insulin-Stimulated Hydrogen Peroxide Dynamics Reveals a Cytosolic Reductive Shift in Skeletal Muscle. Redox Biol. 2025, 82, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterbourn, C.C. Reconciling the Chemistry and Biology of Reactive Oxygen Species. Nat Chem Biol 2008, 4, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Peskin, A.V.; Kleffmann, T.; Radi, R.; Pace, P.E. Carbon Dioxide/Bicarbonate Is Required for Sensitive Inactivation of Mammalian Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase by Hydrogen Peroxide. Proc National Acad Sci 2023, 120, e2221047120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, B.C.; Chang, C.J. Chemistry and Biology of Reactive Oxygen Species in Signaling or Stress Responses. Nat Chem Biol 2011, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. Dissipative Structures, Dynamics and Entropy. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1975, 9, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manford, A.G.; Rodríguez-Pérez, F.; Shih, K.Y.; Shi, Z.; Berdan, C.A.; Choe, M.; Titov, D.V.; Nomura, D.K.; Rape, M. A Cellular Mechanism to Detect and Alleviate Reductive Stress. Cell 2020, 183, 46–61.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, N.; Saito, Y.; Niki, E. Actions of Thiols, Persulfides, and Polysulfides as Free Radical Scavenging Antioxidants. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2022, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, D.P.; Shrestha, S.; Galler, M.; Cao, M.; Daly, L.A.; Campbell, A.E.; Eyers, C.E.; Veal, E.A.; Kannan, N.; Eyers, P.A. Aurora A Regulation by Reversible Cysteine Oxidation Reveals Evolutionarily Conserved Redox Control of Ser/Thr Protein Kinase Activity. Sci Signal 2020, 13, eaax2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinichenko, A.L.; Jappy, D.; Solius, G.M.; Maltsev, D.I.; Bogdanova, Y.A.; Mukhametshina, L.F.; Sokolov, R.A.; Moshchenko, A.A.; Shaydurov, V.A.; Rozov, A.V.; et al. Chemogenetic Emulation of Intraneuronal Oxidative Stress Affects Synaptic Plasticity. Redox Biol 2023, 60, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Fu, L.; Jung, Y.; Conte, M.L.; Lawson, J.R.; Lowther, W.T.; Sun, R.; Liu, K.; Yang, J.; Carroll, K.S. Chemical Proteomics Reveals New Targets of Cysteine Sulfinic Acid Reductase. Nat Chem Biol 2018, 14, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, L.; Okraine, Y.V.; Orlowski, J.; Matzkin, S.; Scarponi, I.; Miranda, M.V.; Nusblat, A.; Gottifredi, V.; Alonso, L.G. Conserved Cysteine-Switches for Redox Sensing Operate in the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor P21(CIP/KIP) Protein Family. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.L.; Harmon, C.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Xiao, H.; Gruszczyk, A.V.; Bradshaw, G.A.; Tran, N.; Garrity, R.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Szpyt, J.; et al. Cysteine 253 of UCP1 Regulates Energy Expenditure and Sex-Dependent Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Cell Metab 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.G.; Sandoval-Perez, A.; Rangarajan, A.V.; Gunderson, E.L.; Jacobson, M.P. Cysteine Oxidation in Proteins: Structure, Biophysics, and Simulation. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbl, C.; Morris, V.K.; Dam, L. van; Visscher, M.; Polderman, P.E.; Hartlmüller, C.; Ruiter, H. de; Hora, M.; Liesinger, L.; Birner-Gruenberger, R.; et al. Cysteine Oxidation Triggers Amyloid Fibril Formation of the Tumor Suppressor P16INK4A. Redox Biol 2020, 28, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, J.R.; Madhani, M.; Cuello, F.; Charles, R.L.; Brennan, J.P.; Schröder, E.; Browning, D.D.; Eaton, P. Cysteine Redox Sensor in PKGIa Enables Oxidant-Induced Activation. Science 2007, 317, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, Y.; Lillig, C.H. Cysteinyl and Methionyl Redox Switches: Structural Prerequisites and Consequences. Redox Biol. 2023, 65, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Newberry, M. Fractal Scaling and the Aesthetics of Trees. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannink, T.; Buhrman, H. Quantum Pascal’s Triangle and Sierpinski’s Carpet. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: A Theory Based on Free Radical and Radiation Chemistry. J Gerontology 1956, 11, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Origin and Evolution of the Free Radical Theory of Aging: A Brief Personal History, 1954–2009. Biogerontology 2009, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.D.; Venditti, P. Evolution of the Knowledge of Free Radicals and Other Oxidants. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 9829176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, V.N. The Free Radical Theory of Aging Is Dead. Long Live the Damage Theory! Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, Oxidative Stress and the Biology of Ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.; Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Schmidt, C.A. Non-Linear Cysteine Redox Proteoform Dynamics in the I-Space: A Novel Theory of Redox Regulation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C.; Halliwell, B. Antioxidants: Molecules, Medicines, and Myths. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2010, 393, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reflections of an Aging Free Radical. Free Radic Biology Medicine 2020, 161, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P. Antioxidants as Therapies: Can We Improve on Nature? Free Radical Bio Med 2014, 66, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frijhoff, J.; Winyard, P.G.; Zarkovic, N.; Davies, S.S.; Stocker, R.; Cheng, D.; Knight, A.R.; Taylor, E.L.; Oettrich, J.; Ruskovska, T.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1144–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.; Hughes, C.M.; Cobley, J.N.; Davison, G.W. The Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant MitoQ, Attenuates Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial DNA Damage. Redox Biol 2020, 36, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; McHardy, H.; Morton, J.P.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Close, G.L. Influence of Vitamin C and Vitamin E on Redox Signaling: Implications for Exercise Adaptations. Free Radical Bio Med 2015, 84, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Oxygen Species and the Central Nervous System. J. Neurochem. 1992, 59, 1609–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegeneration: Where Are We Now? J. Neurochem. 2006, 97, 1634–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Dor, Y.K.; Nambara, K.; Pollina, E.A.; Lin, C.; Greenberg, M.E.; Rogulja, D. Sleep Loss Can Cause Death through Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Gut. Cell 2020, 181, 1307–1328.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorsman, H.O.; Müller, M.A.; Liu, P.Z.; Sanchez, L.G.; Kempf, A.; Gerbig, S.; Spengler, B.; Miesenböck, G. Sleep Pressure Accumulates in a Voltage-Gated Lipid Peroxidation Memory. Nature 2025, 641, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Song, S.M.; Talbot, C.B.; Miesenböck, G. A Potassium Channel β-Subunit Couples Mitochondrial Electron Transport to Sleep. Nature 2019, 568, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Noble, A.; Jimenez-Fernandez, E.; Moya, M.-T.V.; Guille, M.; Husi, H. Catalyst-Free Click PEGylation Reveals Substantial Mitochondrial ATP Synthase Sub-Unit Alpha Oxidation before and after Fertilisation. Redox Biol 2019, 26, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncay, A.; Noble, A.; Guille, M.; Cobley, J.N. RedoxiFluor: A Microplate Technique to Quantify Target-Specific Protein Thiol Redox State in Relative Percentage and Molar Terms. Free Radical Bio Med 2022, 181, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, A.; Crabtree, D.R.; Muggeridge, D.J.; Husi, H.; Cobley, J.N. Performance Benchmarking Microplate-Immunoassays for Quantifying Target-Specific Cysteine Oxidation Reveals Their Potential for Understanding Redox-Regulation and Oxidative Stress. Free Radical Bio Med 2023, 204, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Po, A.; Eyers, C.E. Top-Down Proteomics and the Challenges of True Proteoform Characterization. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 3663–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Day, A.M.; Galler, M.; Latimer, H.R.; Byrne, D.P.; Foy, T.W.; Dwyer, E.; Bennett, E.; Palmer, J.; Morgan, B.A.; et al. A Peroxiredoxin-P38 MAPK Scaffold Increases MAPK Activity by MAP3K-Independent Mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3140–3154.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, D.P.; Rawlins, C.M.; DeHart, C.J.; Fornelli, L.; Schachner, L.F.; Lin, Z.; Lippens, J.L.; Aluri, K.C.; Sarin, R.; Chen, B.; et al. Best Practices and Benchmarks for Intact Protein Analysis for Top-down Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timp, W.; Timp, G. Beyond Mass Spectrometry, the next Step in Proteomics. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaax8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuti, N.; Kelleher, N.L. Decoding Protein Modifications Using Top-down Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tentori, A.M.; Yamauchi, K.A.; Herr, A.E. Detection of Isoforms Differing by a Single Charge Unit in Individual Cells. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed 2016, 55, 12431–12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Melby, J.A.; Roberts, D.S.; Ge, Y. Top-down Proteomics: Challenges, Innovations, and Applications in Basic and Clinical Research. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2020, 17, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Brown, K.A.; Lin, Z.; Ge, Y. Top-Down Proteomics: Ready for Prime Time? Anal Chem 2018, 90, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong, C.; Wu, S.; Meng, D.; Liu, X.; Brewer, H.M.; Kaiser, B.L.D.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Cort, J.R.; Pevzner, P.; Smith, R.D.; et al. Top-down Proteomics Reveals a Unique Protein S-Thiolation Switch in Salmonella Typhimurium in Response to Infection-like Conditions. Proc National Acad Sci 2013, 110, 10153–10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, N.L.; Lin, H.Y.; Valaskovic, G.A.; Aaserud, D.J.; Fridriksson, E.K.; McLafferty, F.W. Top Down versus Bottom Up Protein Characterization by Tandem High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A. Oxidative Stress: What Is It? Can It Be Measured? Where Is It Located? Can It Be Good or Bad? Can It Be Prevented? Can It Be Cured? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N.; Bartlett, J.D.; Kayani, A.; Murray, S.W.; Louhelainen, J.; Donovan, T.; Waldron, S.; Gregson, W.; Burniston, J.G.; Morton, J.P.; et al. PGC-1α Transcriptional Response and Mitochondrial Adaptation to Acute Exercise Is Maintained in Skeletal Muscle of Sedentary Elderly Males. Biogerontology 2012, 13, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Sakellariou, G.K.; Murray, S.; Waldron, S.; Gregson, W.; Burniston, J.G.; Morton, J.P.; Iwanejko, L.A.; Close, G.L. Lifelong Endurance Training Attenuates Age-Related Genotoxic Stress in Human Skeletal Muscle. Longev Heal 2013, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L.; Traustadóttir, T. Aerobic Exercise Training Partially Reverses the Impairment of Nrf2 Activation in Older Humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A.; Guille, M.; Cobley, J.N. ALISA: A Microplate Assay to Measure Protein Thiol Redox State. Free Radical Bio Med 2021, 174, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muggeridge, D.J.; Crabtree, D.R.; Tuncay, A.; Megson, I.L.; Davison, G.; Cobley, J.N. Exercise Decreases PP2A-Specific Reversible Thiol Oxidation in Human Erythrocytes: Implications for Redox Biomarkers. Free Radical Bio Med 2022, 182, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, P.A.; Duan, J.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Shukla, A.K.; Wang, L.; Bammler, T.K.; Qian, W.-J.; Marcinek, D.J. Fatiguing Contractions Increase Protein S-Glutathionylation Occupancy in Mouse Skeletal Muscle. Redox Biol. 2018, 17, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.J.A. Adaptive Homeostasis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2016, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Meneses-Valdes, R.; Jensen, T.E. Compartmentalized Muscle Redox Signals Controlling Exercise Metabolism – Current State, Future Challenges. Redox Biol 2020, 35, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez-Olguin, C.; Knudsen, J.R.; Raun, S.H.; Li, Z.; Dalbram, E.; Treebak, J.T.; Sylow, L.; Holmdahl, R.; Richter, E.A.; Jaimovich, E.; et al. Cytosolic ROS Production by NADPH Oxidase 2 Regulates Muscle Glucose Uptake during Exercise. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Meneses-Valdes, R.; Kritsiligkou, P.; Fuentes-Lemus, E. From Workout to Molecular Switches: How Does Skeletal Muscle Produce, Sense, and Transduce Subcellular Redox Signals? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 209, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V. Personalized Redox Biology: Designs and Concepts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Casas-Martinez, J.C.; Zarzuela, E.; Muñoz, J.; Miranda-Vizuete, A.; Goljanek-Whysall, K.; McDonagh, B. Peroxiredoxin 2 Is Required for the Redox Mediated Adaptation to Exercise. Redox Biol 2023, 60, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaritelis, N.V.; Kyparos, A.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Panayiotou, G.; Zafeiridis, A.; Dipla, K.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Vrabas, I.S. Reductive Stress after Exercise: The Issue of Redox Individuality. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulev, Y.; Morlot, S.; Matifas, A.; Huang, B.; Molin, M.; Toledano, M.B.; Charvin, G. Nonlinear Feedback Drives Homeostatic Plasticity in H2O2 Stress Response. eLife 2017, 6, e23971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, C.S.; Rohwer, J.M. Computational Models as Catalysts for Investigating Redoxin Systems. Essays Biochem. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.K.; Sikes, H.D. Quantifying Intracellular Hydrogen Peroxide Perturbations in Terms of Concentration. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, C.; Schessner, J.P.; Willems, S.; Michaelis, A.C.; Mann, M. Accurate Label-Free Quantification by DirectLFQ to Compare Unlimited Numbers of Proteomes. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picotti, P.; Aebersold, R. Selected Reaction Monitoring–Based Proteomics: Workflows, Potential, Pitfalls and Future Directions. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burniston, J.G.; Kenyani, J.; Gray, D.; Guadagnin, E.; Jarman, I.H.; Cobley, J.N.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wastling, J.M.; Lisboa, P.J.; et al. Conditional Independence Mapping of DIGE Data Reveals PDIA3 Protein Species as Key Nodes Associated with Muscle Aerobic Capacity. J Proteomics 2014, 106, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.A.; Cobley, J.N.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L.; Edwards, B.J.; Koch, L.G.; Britton, S.L.; Burniston, J.G. Label-Free LC-MS Profiling of Skeletal Muscle Reveals Heart-Type Fatty Acid Binding Protein as a Candidate Biomarker of Aerobic Capacity. Proteomes 2013, 1, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobley, J.N.; Malik, Z.Ab.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L.; Edwards, B.J.; Burniston, J.G. Age- and Activity-Related Differences in the Abundance of Myosin Essential and Regulatory Light Chains in Human Muscle. Proteomes 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, N.; Mittenbühler, M.J.; Xiao, H.; Shin, S.; Wei, S.M.; Henze, E.K.; Schindler, S.; Mehravar, S.; Wood, D.M.; Petrocelli, J.J.; et al. The Human Zinc-Binding Cysteine Proteome. Cell 2025, 188, 832–850.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, K.M.; Correia, B.E.; Lum, K.M.; Forli, S.; Horning, B.D.; González-Páez, G.E.; Chatterjee, S.; Lanning, B.R.; Teijaro, J.R.; Olson, A.J.; et al. Proteome-Wide Covalent Ligand Discovery in Native Biological Systems. Nature 2016, 534, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerapana, E.; Wang, C.; Simon, G.M.; Richter, F.; Khare, S.; Dillon, M.B.D.; Bachovchin, D.A.; Mowen, K.; Baker, D.; Cravatt, B.F. Quantitative Reactivity Profiling Predicts Functional Cysteines in Proteomes. Nature 2010, 468, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cravatt, B.F.; Simon, G.M.; III, J.R.Y. The Biological Impact of Mass-Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Nature 2007, 450, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, E.K.; Zhang, Y.; Dix, M.M.; Cravatt, B.F. Global Profiling of Phosphorylation-Dependent Changes in Cysteine Reactivity. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suskiewicz, M.J. The Logic of Protein Post-translational Modifications (PTMs): Chemistry, Mechanisms and Evolution of Protein Regulation through Covalent Attachments. BioEssays 2024, 46, e2300178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, N.M.; Sinitcyn, P.; Forny, P.; Peters-Clarke, T.M.; Fecher, C.; Smith, A.J.; Shishkova, E.; Arrey, T.N.; Pashkova, A.; Robinson, M.L.; et al. Fast and Deep Phosphoproteome Analysis with the Orbitrap Astral Mass Spectrometer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. Methionine Oxidation Products as Biomarkers of Oxidative Damage to Proteins and Modulators of Cellular Metabolism and Toxicity. Redox Biochem. Chem. 2025, 12, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. Protein Oxidation and Peroxidation. Biochem J 2016, 473, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Feng, H.; Sundberg, B.; Yang, J.; Powers, J.; Christian, A.H.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Monnin, C.; Avizonis, D.; Thomas, C.J.; et al. Methionine Oxidation Activates Pyruvate Kinase M2 to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Mol Cell 2022, 82, 3045–3060.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yang, X.; Jia, S.; Weeks, A.M.; Hornsby, M.; Lee, P.S.; Nichiporuk, R.V.; Iavarone, A.T.; Wells, J.A.; Toste, F.D.; et al. Redox-Based Reagents for Chemoselective Methionine Bioconjugation. Science 2017, 355, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi, S.; Radi, R. Fundamentals on the Biochemistry of Peroxynitrite and Protein Tyrosine Nitration. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, R. Interplay of Carbon Dioxide and Peroxide Metabolism in Mammalian Cells. J Biol Chem 2022, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R. Oxygen Radicals, Nitric Oxide, and Peroxynitrite: Redox Pathways in Molecular Medicine. Proc National Acad Sci 2018, 115, 5839–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Butterfield, D.A. Identification of the Oxidative Stress Proteome in the Brain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative Stress, Dysfunctional Glucose Metabolism and Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative Modification of Brain Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease: Perspective on Future Studies Based on Results of Redox Proteomics Studies. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 33, S243–S251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, J.Q.; Simon, M.; Korotkov, A.; Welle, K.A.; Hryhorenko, J.R.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V.; Ghaemmaghami, S. Accurate Proteomewide Measurement of Methionine Oxidation in Aging Mouse Brains. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledo, J.C.; Aledo, P. Susceptibility of Protein Methionine Oxidation in Response to Hydrogen Peroxide Treatment–Ex Vivo versus In Vitro: A Computational Insight. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Pfeuffer, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, P.; Käll, L.; Sachsenberg, T.; Demichev, V.; Bai, M.; Kohlbacher, O.; Perez-Riverol, Y. Quantms: A Cloud-Based Pipeline for Quantitative Proteomics Enables the Reanalysis of Public Proteomics Data. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1603–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metric | Mathematical tool | Equation (peptide level) | Biological interpretation |

| Lyapunov exponent (λ) | Exponential divergence of nearby trajectories. | Positive values denote redox shifts diverging over time. Negative values denote converging or stable trajectories. | |

| Attractor geometry | Correlation dimension (D2) via Grassberger-Proaccia algorithm. | Redox states oscillate about nonlinear basins with fractal, self-similar structure. | |

| Entropy production | Kolmogorov-Sinai (KS) or approximate Entropy (ApEn). | The dynamic generation of information reflects continually redox remodeling of the peptide oxidation state. | |

| State recurrence | Recurrence quantification analysis (RQA), Poincaré maps. | Where is the Heaviside function | Detects long-range memory, hidden periodicity, and/or structured noise in cysteine oxidation datasets |

| Bifurcation detection | Delay-coordinate bifurcation diagram with control parameter. | , scan over (e.g., ROS flux) | Can reveal whether small redox changes trigger shape transitions in cysteine oxidation—phase space shifts. |

| Phase-space remodeling | Delay embedding with topological analysis. | Can reveal the stretching and folding that is characteristic of chaotic attractors. |

| Metric | Mathematical tool | Equation (peptide level) | Biological interpretation |

| Box-Counting Dimension (D(B)) | Estimates geometric complexity by covering the trajectory in -sized boxes. | Measures how fully the redox trajectory fills its phase space. A High DB suggests a recursive filling of the available space—the [0,100] interval. | |

| Curvature entropy | Quantifies the entropy (S) of trajectory curvature fluctuations. | Where ki is local curvature. | Measures dynamic inflections in redox trajectories—capturing looping, spiraling, or sharp transition behavior. |

| Fractal recurrence score | Assesses self-similarity in recurrence plots. | Diagonal line structures in 2D recurrence plots of Z(t); compute fractal dimension of recurrences. | Measures multi-scale repetition in cysteine oxidation patterns, with the ability to capture periodic cycles. |

| Spectral fractality | Power-law scaling of the trajectory frequency domain. | Power spectrum , where quantifies long-range memory | Measures cysteine oxidation dynamics across timescales with the ability to capture nested cycles or autocorrelation behavior. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).