Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Population

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Neuroactive Steroid Assays

Analytic Methods

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Sex Steroid Levels in Male and Females with Hypertension and COVID-19 Infection

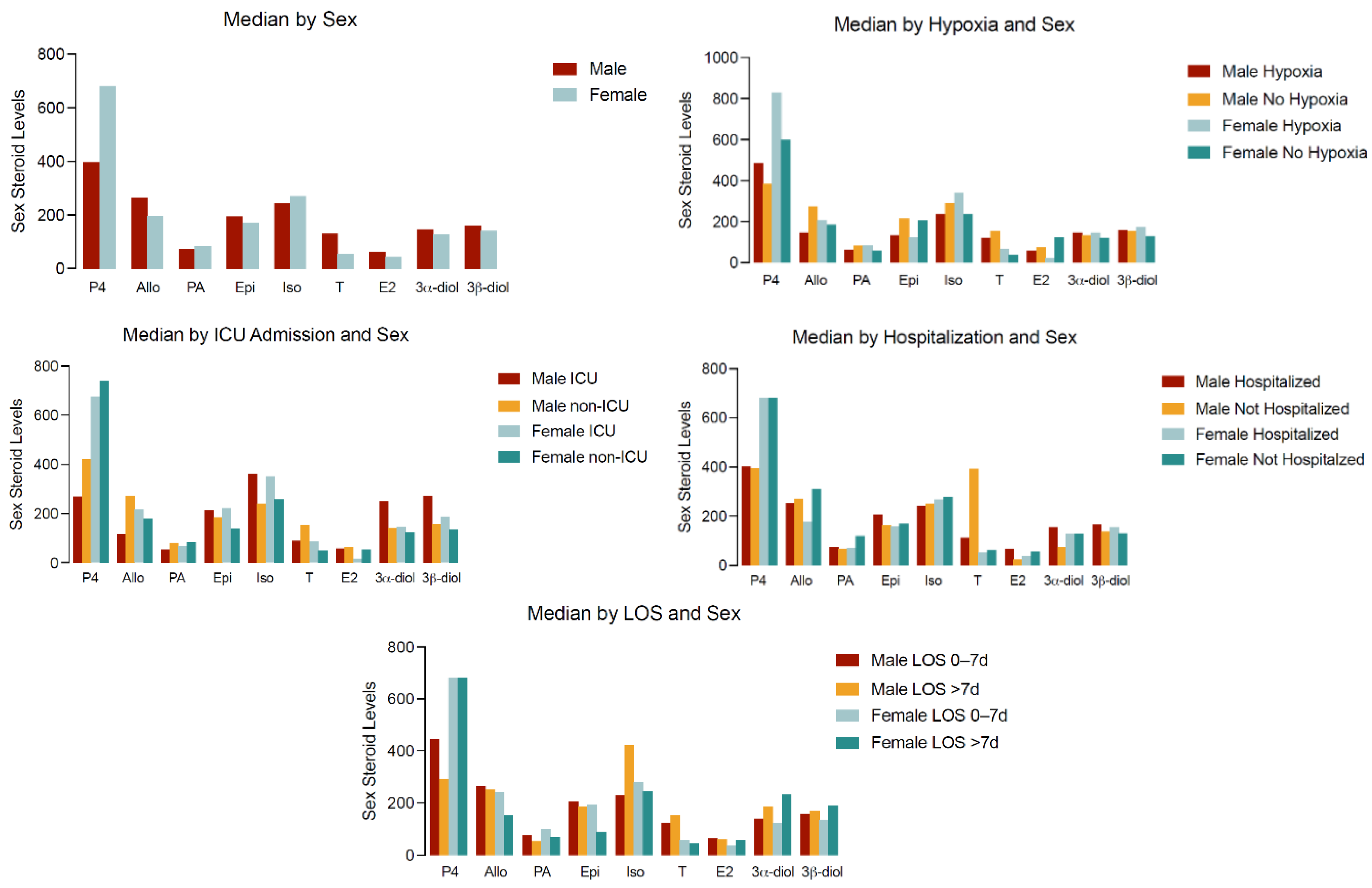

Sex Steroid Levels and Clinical Outcomes in Subjects with Hypertension and COVID-19 Infection

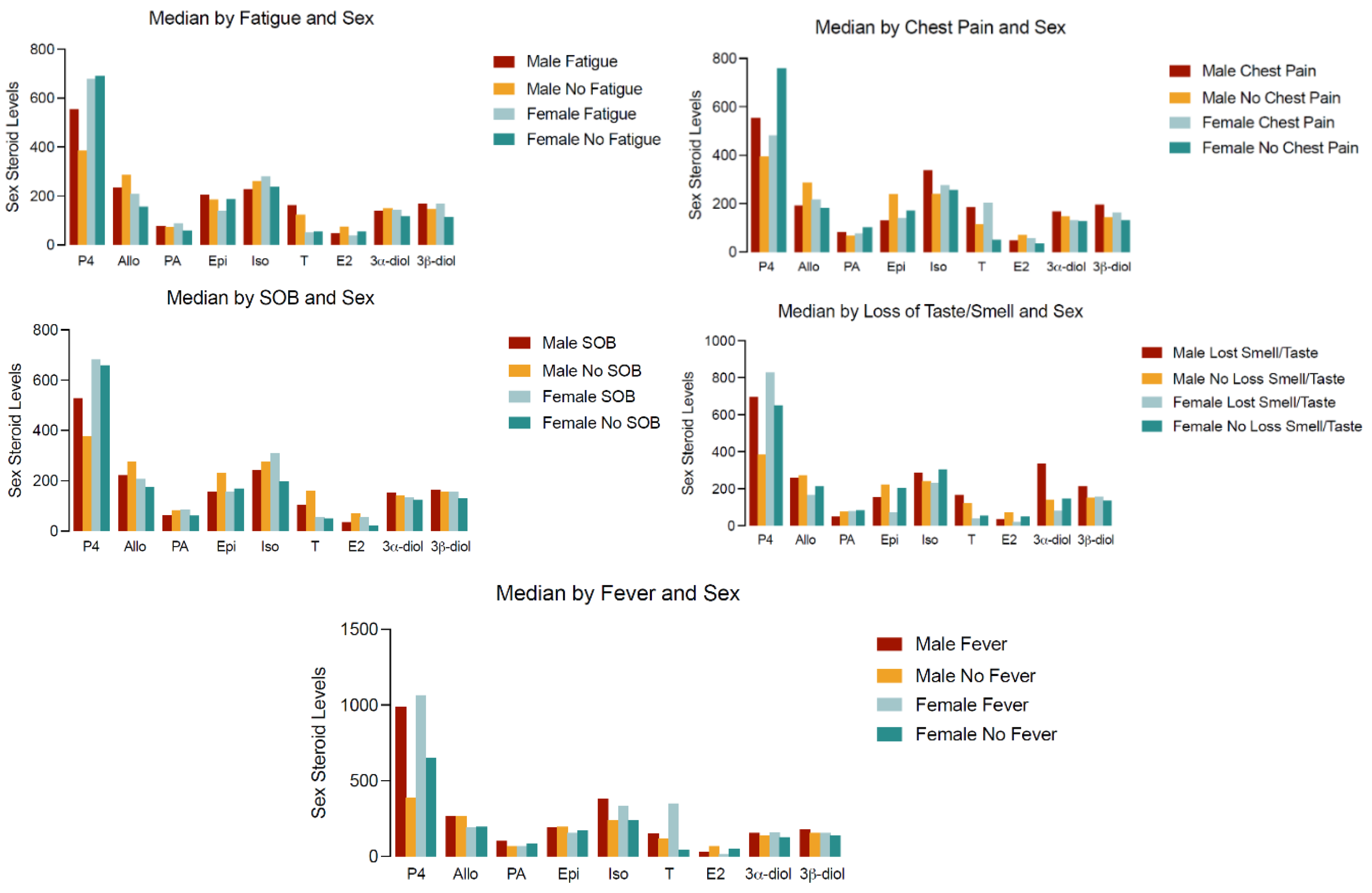

Sex Steroid Concentrations and Symptoms in Male and Females with Hypertension and COVID-19 Infection

Sex Dimorphism in Steroid Levels and Hospitalization and ICU Admission

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

References

- Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED. Sex Differences in Mortality from COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Men Vulnerable and Women Protected? JACC Case Rep. 2020:10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027. [CrossRef]

- Capuano A, Rossi F, Paolisso G. Covid-19 Kills More Men Than Women: An Overview of Possible Reasons. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:131-131. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan A, Olsson P-E. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: are males more vulnerable? Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):53-53. [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. The Lancet. 2020;396(10250):565-582. [CrossRef]

- Giagulli VA, Guastamacchia E, Magrone T, et al. Worse progression of COVID-19 in men: Is testosterone a key factor? Andrology. Jan 2021;9(1):53-64. [CrossRef]

- Stasi VD, Rastrelli G. The Role of Sex Hormones in the Disparity of COVID-19 Outcomes Based on Gender. J Sex Med. Dec 2021;18(12):1950-1954. [CrossRef]

- Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(7):442-447. [CrossRef]

- Mauvais-Jarvis F. Do Anti-androgens Have Potential as Therapeutics for COVID-19? Endocrinology. Aug 1 2021;162(8)doi:10.1210/endocr/bqab114.

- Lanser L, Burkert FR, Thommes L, et al. Testosterone Deficiency Is a Risk Factor for Severe COVID-19. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2021;12:694083. [CrossRef]

- Cinislioglu AE, Cinislioglu N, Demirdogen SO, et al. The relationship of serum testosterone levels with the clinical course and prognosis of COVID-19 disease in male patients: A prospective study. Andrology. Jul 19 2021;doi:10.1111/andr.13081.

- Pinna G. Sex and COVID-19: A Protective Role for Reproductive Steroids. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021/01/01/ 2021;32(1):3-6. [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa S, Zhang N, McPhaul MJ, et al. Association of Circulating Sex Hormones With Inflammation and Disease Severity in Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. May 3 2021;4(5):e2111398. [CrossRef]

- Gubbels Bupp MR, Potluri T, Fink AL, Klein SL. The Confluence of Sex Hormones and Aging on Immunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2018;9:1269. [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa S, Reddy A, Karam JS, et al. Prevalence of subnormal testosterone concentrations in men with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(3):359-366. [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa S, Ghanim H, Batra M, Dandona P. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in men with diabesity. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1516-1525. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian V, Naing S. Hypogonadism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence and effects. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18(2):112-117. [CrossRef]

- Rastrelli G, Di Stasi V, Inglese F, et al. Low testosterone levels predict clinical adverse outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia patients. Andrology. 2021;9(1):88-98. [CrossRef]

- Çayan S, Uğuz M, Saylam B, Akbay E. Effect of serum total testosterone and its relationship with other laboratory parameters on the prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in SARS-CoV-2 infected male patients: a cohort study. Aging Male. 2020;1-11. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi T, Iwasaki A. Sex differences in immune responses. Science. 2021;371(6527):347. [CrossRef]

- Di Florio DN, Sin J, Coronado MJ, Atwal PS, Fairweather D. Sex differences in inflammation, redox biology, mitochondria and autoimmunity. Redox Biology. 2020/04/01/ 2020;31:101482. [CrossRef]

- Peng M, He J, Xue Y, Yang X, Liu S, Gong Z. Role of Hypertension on the Severity of COVID-19: A Review. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2021 Nov 1;78(5):e648-e655. PMID: 34321401; PMCID: PMC8562915 . [CrossRef]

- Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2001;37:1199–208. [CrossRef]

- Caulin-Glaser T, Garcia-Cardena G, Sarrel P, et al. 17 beta-estradiol regulation of human endothelial cell basal nitric oxide release, independent of cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization. Circ Res. 1997;81:885–92. [CrossRef]

- Schror K, Morinelli TA, Masuda A, et al. Testosterone treatment enhances thromboxane A2 mimetic induced coronary artery vasoconstriction in guinea pigs. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24 (Suppl 1):50–2. [CrossRef]

- Chou TM, Sudhir K, Hutchison SJ, et al. Testosterone induces dilation of canine coronary conductance and resistance arteries in vivo. Circulation. 1996;94:2614–9. [CrossRef]

- Hughes GS, Mathur RS, Margolius HS. Sex steroid hormones are altered in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1989;7:181–7.

- Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman RP, Matthews KA, et al. Sex-hormone-binding globulin and the free androgen index are related to cardiovascular risk factors in multiethnic premenopausal and perimenopausal women enrolled in the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN) Circulation. 2005;111:1242–9. [CrossRef]

- Phillips GB, Jing TY, Laragh JH. Serum sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women with hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11:523–6. [CrossRef]

- Prendergast HM, Kotini-Shah P, Pobee R, Richardson M, Ardati A, Darbar D, Khosla S. Association of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Phenotypes and Polymorphisms with Clinical Outcomes in SARS-CoV2 Patients with Hypertension in an Urban Emergency Department. Current Hypertension Reviews. 2024 Oct 15. s.

- Pinna G, Uzunova V, Matsumoto K, Puia G, Mienville JM, Costa E, Guidotti A. Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABA(A) receptor agonist muscimol. Neuropharmacology. 2000 Jan 28;39(3):440-8. PMID: 10698010 . [CrossRef]

- Osborne LM, Etyemez S, Pinna G, Alemani R, Standeven LR, Wang XQ, Payne JL. Neuroactive steroid biosynthesis during pregnancy predicts future postpartum depression: a role for the 3α and/or 3β-HSD neurosteroidogenic enzymes? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2025 May;50(6):904-912. Epub 2025 Jan 30. Erratum in: Neuropsychopharmacology. 2025 May;50(6):1021. doi: 10.1038/s41386-025-02109-z. PMID: 39885361; PMCID: PMC12032070 . [CrossRef]

- Wagner AK, McCullough EH, Niyonkuru C, et al. Acute serum hormone levels: characterization and prognosis after severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2011;28:871–88.

- Wagner, J., Dusick, J. R., McArthur, D. L., Cohan, P., Wang, C., Swerdloff, R., Boscardin, W. J., and Kelly, D. F. (2010). Acute gonadotroph and somatotroph hormonal suppression after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 27, 1007–1019.

- Dossett, L.A., Swenson, B.R., Evans, H.L., Bonatti, H., and Sawyer, R.G. (2008a). Serum estradiol concentration as a predictor of death in critically ill and injured adults. Surg. Infect. 9, 41–48.

- Dossett, L.A., Swenson, B.R., Heffernan, D., Bonatti, H., Metzger, R., Sawyer, R.G., and May, A.K. (2008b). High levels of endogenous estrogens are associated with death in the critically injured adult. J. Trauma 64, 580–585.

- Christeff N, Benassayag C, Carli-Vielle C, Carli A, Nunez EA. Elevated oestrogen and reduced testosterone levels in the serum of male septic shock patients. Journal of steroid biochemistry. Apr 1988;29(4):435-40. [CrossRef]

- Gee A, Sawai R, Differding J, Muller P, Underwood S, Schreiber M. The influence of sex hormone on coagulation and inflammation in the trauma patients. Shock (Augusta, Ga). 03/01 2008;29:334-41. [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, V., Rastrelli, G., Inglese, F. et al. Higher testosterone is associated with increased inflammatory markers in women with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: preliminary results from an observational study. J Endocrinol Invest 45, 639–648 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, G., Weekers, F., Baxter, R.C., Wouters, P., Iranmanesh, A.., Bouillon, R., and Veldhuis, J.D. (2001). Fiveday pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone administration unveils combined hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal defects underlying profound hypoandrogenism in men with prolongedcritical illness. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 3217–3226.

- Kalantaridou, S.N., Makrigiannakis, A., Zoumakis, E., and Chrousos, G.P. (2004). Stress and the female reproductive system. J. Reprod. Immunol. 62, 61–68.

- Mastorakos, G., and Pavlatou, M. (2005). Exercise as a stress model and the interplay between the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal and the hypothalamus–pituitary–thyroid axes. Horm. Metab. Res. 37, 577–584.

- Locci A, Pinna G. Neurosteroid biosynthesis down-regulation and changes in GABAA receptor subunit composition: a biomarker axis in stress-induced cognitive and emotional impairment. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 Oct;174(19):3226-3241. Epub 2017 Jun 14. PMID: 28456011; PMCID: PMC5595768 . [CrossRef]

- Dichtel LE, Lawson EA, Schorr M, Meenaghan E, Paskal ML, Eddy KT, Pinna G, Nelson M, Rasmusson AM, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Neuroactive Steroids and Affective Symptoms in Women Across the Weight Spectrum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 May;43(6):1436-1444. Epub 2017 Nov 1. PMID: 29090684; PMCID: PMC5916351 . [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson AM, King MW, Valovski I, Gregor K, Scioli-Salter E, Pineles SL, Hamouda M, Nillni YI, Anderson GM, Pinna G. Relationships between cerebrospinal fluid GABAergic neurosteroid levels and symptom severity in men with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 Apr;102:95-104. Epub 2018 Nov 22. PMID: 30529908; PMCID: PMC6584957 . [CrossRef]

- Pinna G. Allopregnanolone (1938-2019): A trajectory of 80 years of outstanding scientific achievements. Neurobiol Stress. 2020 Aug 5;13:100246. PMID: 32875009; PMCID: PMC7451447 . [CrossRef]

- Balan I, Beattie MC, O’Buckley TK, Aurelian L, Morrow AL. Endogenous Neurosteroid (3α,5α)3-Hydroxypregnan-20-one Inhibits Toll-like-4 Receptor Activation and Pro-inflammatory Signaling in Macrophages and Brain. Sci Rep. 2019 Feb 4;9(1):1220. PMID: 30718548; PMCID: PMC6362084 . [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Overall 123456789N=116 | Female123456789N=53 | Male123456789N=63 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age; Mean (SD) | 62.1 (13.1) | 64.3 (10.1) | 60.3 (15.0) | |

| Age group | >=65 | 55 (47.4%) | 28 (52.8%) | 27 (42.9%) |

| <65 | 61 (52.6%) | 25 (47.2%) | 36 (57.1%) | |

| Sex | Male | 63 (54.3%) | - | 63 (100%) |

| Female | 53 (45.7%) | 53 (100%) | - | |

| Race | NH-Black | 64 (55.2%) | 32 (60.4%) | 32 (50.8%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 40 (34.5%) | 17 (32.1%) | 23 (36.5%) | |

| NH-White | 6 (5.2%) | |||

| Other* | 6 (5.2%) | |||

| Fever** | Yes | 22 (19.0%) | 9 (17.0%) | 13 (20.6%) |

| No | 94 (81.0%) | 44 (83.0%) | 50 (79.4%) | |

| Shortness of Breath | Yes | 64 (55.2%) | 32 (60.4%) | 32 (50.8%) |

| No | 52 (44.8%) | 21 (39.6%) | 31 (49.2%) | |

| Chest Pain/tightness | Yes | 46 (39.7%) | 20 (37.7%) | 26 (41.3%) |

| No | 70 (60.3%) | 33 (62.3%) | 37 (58.7%) | |

| Loss of smell/taste | Yes | 35 (30.2%) | 18 (34.0%) | 17 (27.0%) |

| No | 81 (69.8%) | 35 (66.0%) | 46 (73.0%) | |

| Fatigue | Yes | 62 (53.4%) | 31 (58.5%) | 31 (49.2%) |

| No | 54 (46.6%) | 22 (41.5%) | 32 (50.8%) | |

| Hospitalized | Yes | 97 (83.6%) | 44 (83.0%) | 53 (84.1%) |

| No | 19 (16.4%) | 9 (17.0%) | 10 (15.9%) | |

| ICU admit | Yes | 18 (15.5%) | 8 (15.1%) | 10 (15.9%) |

| No | 98 (84.5%) | 45 (84.9%) | 53 (84.1%) | |

| Length of Stay | >7 days | 33 (28.4%) | 16 (30.2%) | 17 (27.0%) |

| 0-7 days | 83 (71.6%) | 37 (69.8%) | 46 (73.0%) | |

| Ventilator support | Yes | 4 (3.5%) | ||

| No | 111 (96.5%) | |||

| Hypoxia | Yes | 48 (41.7%) | 26 (49.1%) | 22 (35.5%) |

| No | 67 (58.3%) | 27 (50.9%) | 40 (64.5%) | |

| Vasopressor use | Yes | 6 (5.2%) | ||

| No | 110 (94.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).