Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

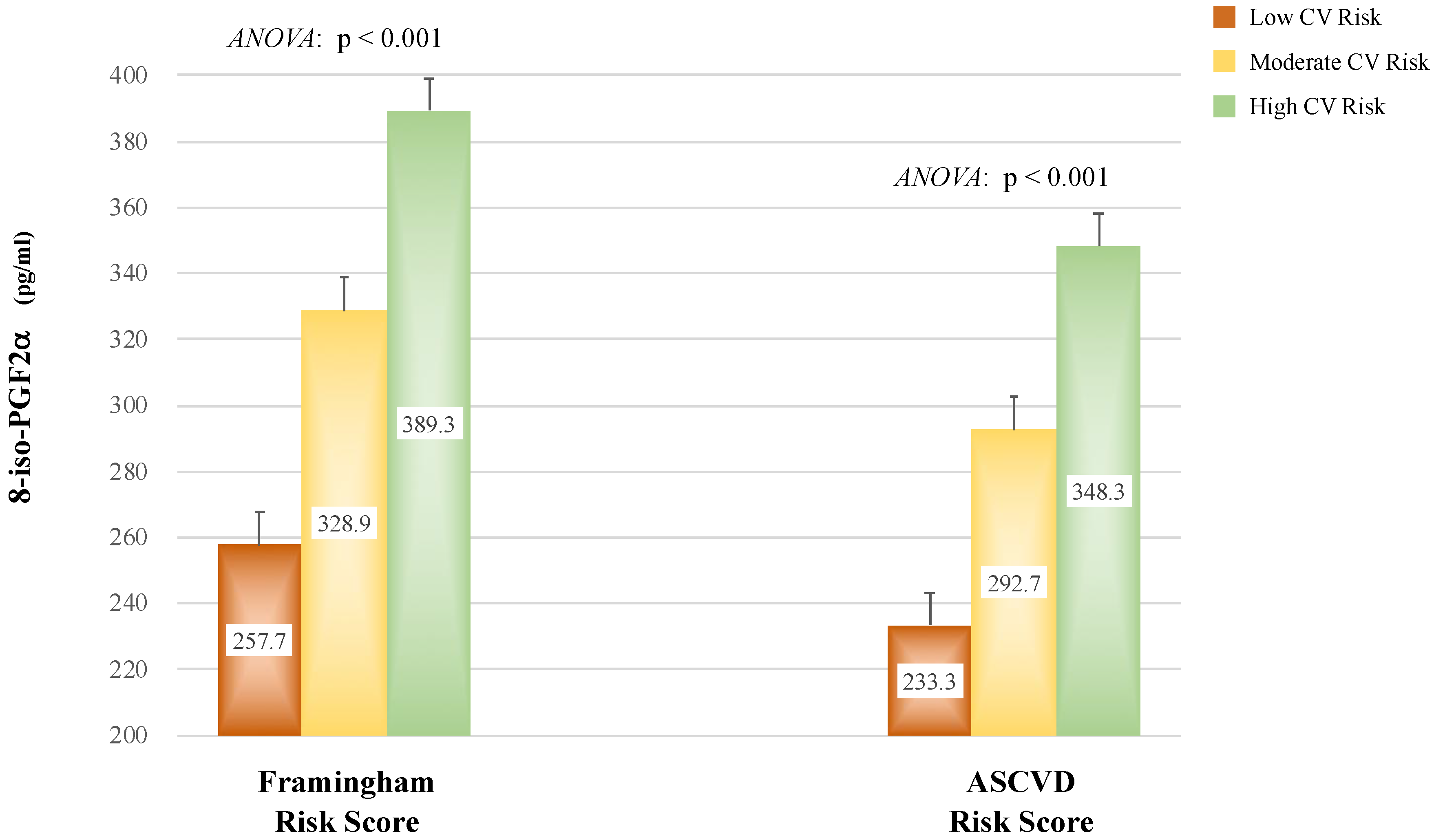

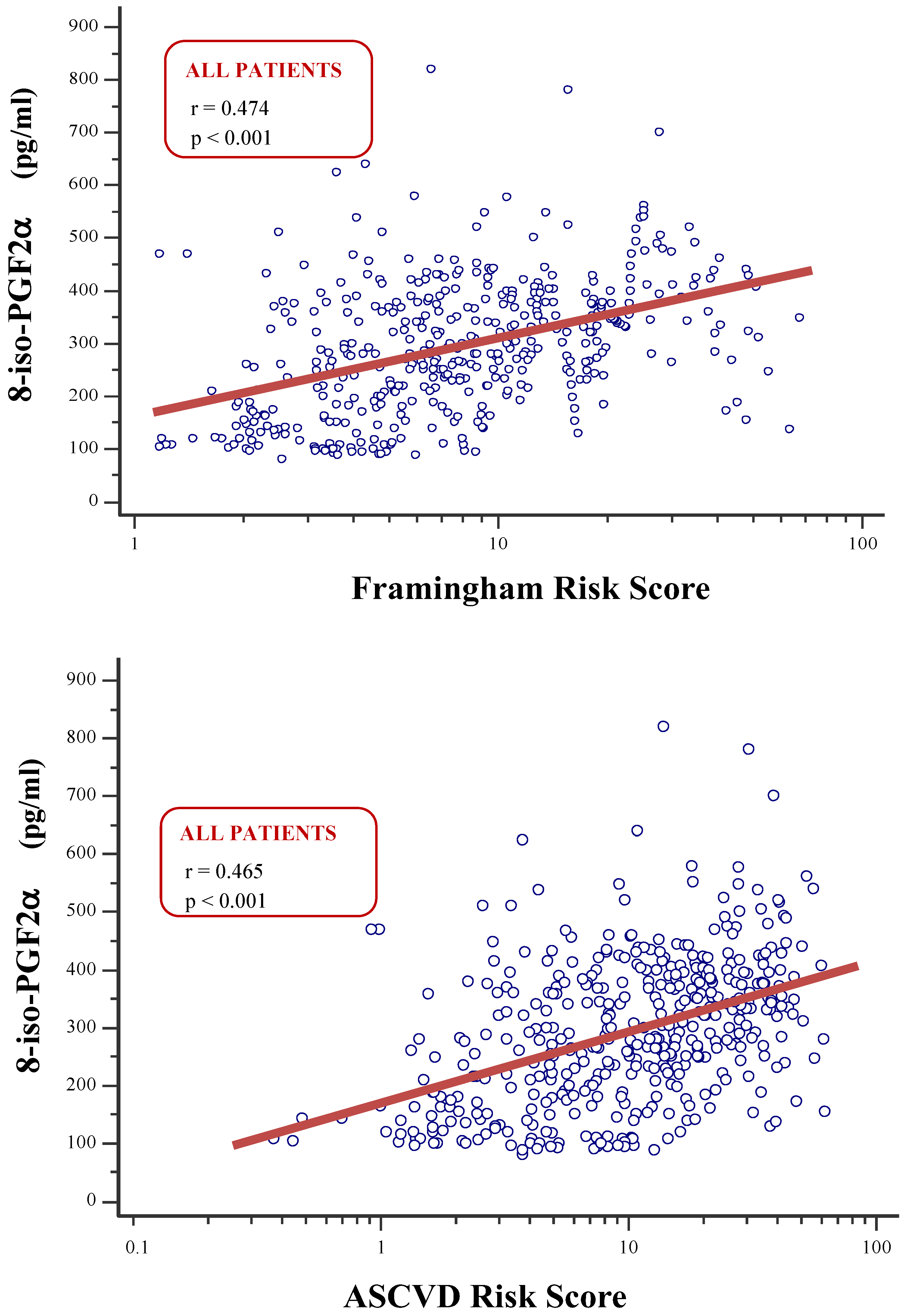

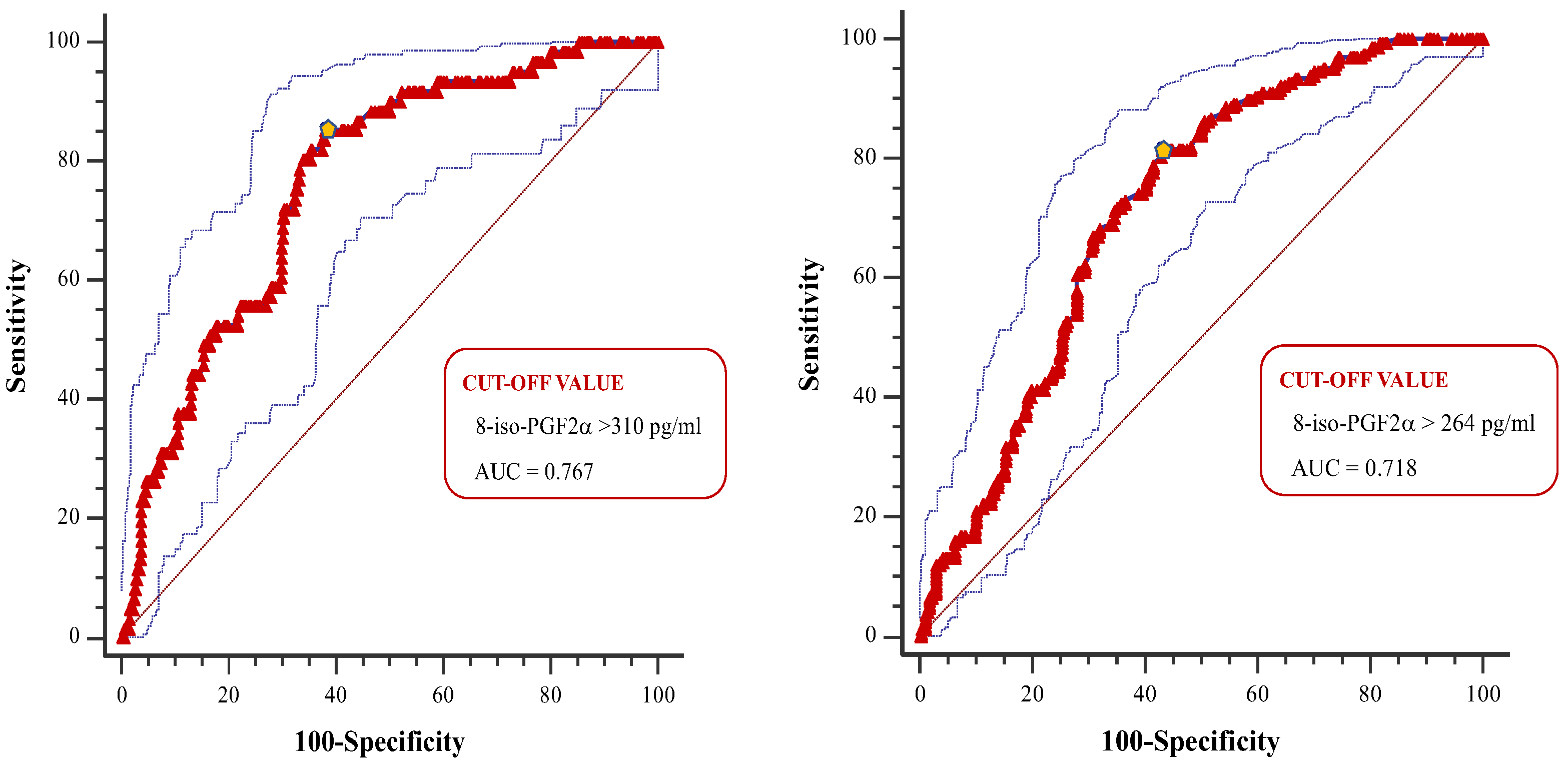

8-iso-prostaglandin-F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) is a recognized marker of oxidative stress. Previous studies suggested that 8-iso-PGF2α plays an important role in the pathogenesis of hypertension and cardiovascular (CV) diseases. However, limited data exist on the prognostic role of 8-iso-PGF2α in hypertensive patients undergoing primary prevention. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between 8-iso-PGF2α and 10-year CV risk, as predicted by validated equations in hypertension patients without CV diseases. Materials and methods. A total of 432 individuals aged 40-75 years were enrolled. Plasma 8-iso-PGF2α was assessed through ELISA method. CV risk was calculated by using the Framingham Risk Score (Fr-S) and the Atherosclerosis Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score (ASCVD-S). Low, moderate, or high CV risks were defined according to validated cutoffs. Results. Individuals with higher CV risk had significantly greater 8-iso-PGF2α values compared to those with low or moderate CV risk (p<0.001). 8-iso-PGF2α correlated strongly with Fr-S and ASCVD-S in the entire population and in patients with normal renal function (all p<0.001), but not in patients with eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73m2. These associations remained significant after adjustment for traditional factors included in the CV risk equations in the overall population and in patients with normal renal function. The 8-iso-PGF22α cutoffs that best distinguished patients with high CV risk were 310 pg/mL for Fr-S and 264 pg/mL for ASCVD-S in the overall population, with significant differences between the groups divided by eGFR (all p<0.001). Conclusion. 8-iso-PGF2α may have a prognostic role in primary prevention of CV events in hypertensive patients, particularly in those with normal renal function.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and population

- Age <40 and >75 years old;

- Renal replacement therapy (transplanted or dialysis patients);

- Pharmacological treatment for cardiac rhythm or conduction abnormalities;

- Use of nonsteroidal or steroidal anti-inflammatory medications within 4 weeks before the start of the study.

- History of cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease;

- Hospitalization for CV cause in the previous 6 months;

- Major non-cardiovascular diseases (history of liver cirrhosis, chronic obstructive lung disease, or neoplasms).

2.2. Clinical and laboratory evaluation

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

CONCLUSION

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morrow JD, Hill KE, Burk RF, Nammour TM, Badr KF, Roberts LJ. A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87(23):9383-9387. [CrossRef]

- Basu S. Fatty acid oxidation and isoprostanes: oxidative strain and oxidative stress. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 2010;82(4-6):219-225. [CrossRef]

- Cottone S, Mulè G, Nardi E, et al. Relation of C-reactive protein to oxidative stress and to endothelial activation in essential hypertension. American journal of hypertension. 2006;19(3):313-318. [CrossRef]

- Minuz P, Patrignani P, Gaino S, et al. Increased Oxidative Stress and Platelet Activation in Patients With Hypertension and Renovascular Disease. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2800-2805. [CrossRef]

- Basu S. Bioactive eicosanoids: Role of prostaglandin F2α and F2-isoprostanes in inflammation and oxidative stress related pathology. Molecules and Cells. 2010;30(5):383-391. [CrossRef]

- Basu S. F 2 -Isoprostanes in Human Health and Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2008;10(8):1405-1434. [CrossRef]

- Godreau A, Lee K, Klein B, Shankar A, Tsai M, Klein R. Association of oxidative stress with mortality: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Oxidants and Antioxidants in Medical Science. 2012;1(3):161. [CrossRef]

- Xuan Y, Gào X, Holleczek B, Brenner H, Schöttker B. Prediction of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular mortality with urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress: Results from a large cohort study. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;273:223-229. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z-J. Systematic review on the association between F2-isoprostanes and cardiovascular disease. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 2013;50(2):108-114. [CrossRef]

- Patrono C, FitzGerald GA. Isoprostanes: Potential Markers of Oxidant Stress in Atherothrombotic Disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1997;17(11):2309-2315. [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli P, Menichelli D, Pastori D, Violi F. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease: new insights. Kardiologia Polska. 2018;76(4):713-722. [CrossRef]

- Shokr H, Dias IHK, Gherghel D. Microvascular function and oxidative stress in adult individuals with early onset of cardiovascular disease. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):4881. [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino RB, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P, CHD Risk Prediction Group. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286(2):180-187. [CrossRef]

- Damen JA, Pajouheshnia R, Heus P, et al. Performance of the Framingham risk models and pooled cohort equations for predicting 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2019;17(1):109. [CrossRef]

- Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935-2959. [CrossRef]

- Gaziano TA, Abrahams-Gessel S, Alam S, et al. Comparison of Nonblood-Based and Blood-Based Total CV Risk Scores in Global Populations. Global Heart. 2016;11(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Mancia G, Kreutz R, et al. [2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH)]. J Hypertens. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ruef J, März W, Winkelmann BR. Markers for endothelial dysfunction, but not markers for oxidative stress correlate with classical risk factors and the severity of coronary artery disease. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. 2006;40(5):274-279. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Mulè G, Paladino G, et al. Relationship between kidney findings and systemic vascular damage in elderly hypertensive patients without overt cardiovascular disease. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2017;19(12). [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Mule G, Costanza G, Mogavero M, Geraci C, Cottone S. Relationship Between Carotid Atherosclerosis and Pulse Pressure with Renal Hemodynamics in Hypertensive Patients. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(4):519-527. [CrossRef]

- Villines TC, Taylor AJ. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis arterial age versus framingham 10-year or lifetime cardiovascular risk. The American journal of cardiology. 2012;110(11):1627-1630. [CrossRef]

- Cottone S, Mule G, Guarneri M, et al. Endothelin-1 and F2-isoprostane relate to and predict renal dysfunction in hypertensive patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2008;24(2):497-503. [CrossRef]

- Ravarotto V, Simioni F, Pagnin E, Davis PA, Calò LA. Oxidative stress – chronic kidney disease – cardiovascular disease: A vicious circle. Life Sciences. 2018;210:125-131. [CrossRef]

- Minuz P, Patrignani P, Gaino S, et al. Determinants of Platelet Activation in Human Essential Hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43(1):64-70. [CrossRef]

- Keaney JF, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Obesity and Systemic Oxidative Stress. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2003;23(3):434-439. [CrossRef]

- Roest M, Voorbij HAM, van der Schouw YT, Peeters PHM, Teerlink T, Scheffer PG. High levels of urinary F2-isoprostanes predict cardiovascular mortality in postmenopausal women. Journal of clinical lipidology. 2008;2(4):298-303. [CrossRef]

- Schwedhelm E, Bartling A, Lenzen H, et al. Urinary 8-iso-Prostaglandin F 2α as a Risk Marker in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation. 2004;109(7):843-848. [CrossRef]

- Kaysen GA, Eiserich JP. The role of oxidative stress-altered lipoprotein structure and function and microinflammation on cardiovascular risk in patients with minor renal dysfunction. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004;15(3):538-548. [CrossRef]

- Morrow JD, Roberts LJ. Mass spectrometric quantification of F2-isoprostanes in biological fluids and tissues as measure of oxidant stress. Methods in enzymology. 1999;300:3-12. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Mule G, Mogavero M, et al. Renal haemodynamics and severity of carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive patients with and without impaired renal function. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(2):160-166. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Mulè G, Morreale M, et al. Association between uric acid and renal function in hypertensive patients: which role for systemic vascular involvement? Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 2016;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Mulè G, Castiglia A, Cusumano C, et al. Subclinical Kidney Damage in Hypertensive Patients: A Renal Window Opened on the Cardiovascular System. Focus on Microalbuminuria. Vol 956.; 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mathur S, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Accelerated atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia, and oxidative stress in end-stage renal disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2002;11(2):141-147. [CrossRef]

- Campean V, Neureiter D, Varga I, et al. Atherosclerosis and Vascular Calcification in Chronic Renal Failure. Kidney and Blood Pressure Research. 2005;28(5-6):280-289. [CrossRef]

- Ruilope LM, Bakris GL. Renal function and target organ damage in hypertension. European Heart Journal. 2011;32(13):1599-1604. [CrossRef]

- Nardi E, Mulè G, Nardi C, et al. Is echocardiography mandatory for patients with chronic kidney disease? Internal and emergency medicine. 2019;14(6):923-929. [CrossRef]

- Namikoshi T, Fujimoto S, Yorimitsu D, et al. Relationship between vascular function indexes, renal arteriolosclerosis, and renal clinical outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2015;20(9):585-590. [CrossRef]

- de Mello Barros Pimentel MV, Bertolami A, Fernandes LP, Barroso LP, Castro IA. Could a lipid oxidative biomarker be applied to improve risk stratification in the prevention of cardiovascular disease? Biomed Pharmacother. 2023 Apr;160:114345. Epub 2023 Feb 6. PMID: 36753953. [CrossRef]

- Ho E, Karimi Galougahi K, Liu CC, Bhindi R, Figtree GA. Biological markers of oxidative stress: Applications to cardiovascular research and practice. Redox Biol. 2013 Oct 8;1(1):483-91. PMID: 24251116; PMCID: PMC3830063. [CrossRef]

| Variable * |

Overall population (n=432) |

eGFR ≥60 (n=279) |

eGFR <60 (n=153) |

p-value ^ | ||||||

| Age (years) | 60 | ± | 10 | 57 | ± | 10 | 65 | ± | 8 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 255 (59) | 173 (64.0) | 82 (53,6) | NS | ||||||

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 109 (25.3) | 59 (21.15) | 50 (32.8) | NS | ||||||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 111 (25.7) | 63 (22.6) | 48 (31.4) | NS | ||||||

| Antihypertensive therapy, n (%) | 415 (96.1) | 270 (96.8) | 145 (94.8) | NS | ||||||

| Clinic systolic BP (mmHg) | 142 | ± | 21 | 143 | ± | 21 | 140 | ± | 20 | NS |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mmHg) | 84 | ± | 13 | 86 | ± | 14 | 80 | ± | 11 | <0.001 |

| Clinic mean BP (mmHg) | 103 | ± | 14 | 105 | ± | 15 | 100 | ± | 12 | 0.001 |

| Clinic pulse pressure (mmHg) | 58 | ± | 16 | 57 | ± | 15 | 60 | ± | 18 | NS |

| Clinic heart rate (bpm) | 73 | ± | 10 | 73 | ± | 10 | 72 | ± | 11 | NS |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||||||||

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 110.1 | ± | 36.1 | 108.6 | ± | 31.7 | 112.8 | ± | 42.9 | NS |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.43 | ± | 1.65 | 6.39 | ± | 1.70 | 6.48 | ± | 1.59 | <0.001 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 191.5 | ± | 43.6 | 193.6 | ± | 40.3 | 187.6 | ± | 48.9 | NS |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 119.06 | ± | 38.80 | 121.69 | ± | 37.65 | 114.27 | ± | 40.32 | NS |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 46.11 | ± | 12.44 | 47.22 | ± | 11.79 | 44.10 | ± | 13.35 | <0.05 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dL) | 118 (86–161) | 105 (81–152) | 136 (104–177) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.43 | ± | 1.14 | 0.92 | ± | 0.16 | 2.36 | ± | 1.53 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 65.9 | ± | 27.5 | 83.5 | ± | 12.8 | 33.8 | ± | 16.1 | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 139 | ± | 3 | 140 | ± | 3 | 139 | ± | 3 | NS |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.35 | ± | 0.40 | 4.33 | ± | 0.38 | 4.37 | ± | 0.43 | NS |

| Endothelial disfunctions and cardiovascular risk | ||||||||||

| 8-iso-PGF2α (pg/mL) | 292.6 | ± | 125.7 | 247.2 | ± | 104.7 | 375.4 | ± | 118.7 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.40 (1.60–3.30) | 2.00 (1.39–2.70) | 3.17 (2.40–3.80) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Framingham Risk Score (%) | 7.46 (4.17–14.06) | 6.49 (3.60–11.76) | 9.44 (6.00–17.83) | 0.001 | ||||||

| Framingham Risk Score < 10%, n (%) | 272 (63.0) | 193 (69.2) | 79 (51.6) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Framingham Risk Score ≥ 20%, n (%) | 61 (14.1) | 36 (12.9) | 25 (16.3) | NS | ||||||

| ASCVD Risk Score (%) | 10.92 (4.92–21.43) | 8.25 (4.24–17.28) | 15.83 (9.59–28.27) | <0.001 | ||||||

| ASCVD Risk Score < 7.5 %, n (%) | 157 (36.3) | 129 (46.2) | 28 (18.3) | <0.001 | ||||||

| ASCVD Risk Score ≥ 15%, n (%) | 167 (38.7) | 87 (31.2) | 80 (52.3) | <0.001 | ||||||

|

* Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range, depending on their distribution. ^ Comparison between eGFR-based groups; non-significant (NS): p > 0.05 Abbreviations: eGFR: estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; BP: Blood Pressure; LDL-c: Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; 8-iso-PGF2α: 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ASCVD: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. | ||||||||||

| 8-iso-PGF2α | Framingham Risk Score |

ASCVD Risk Score |

|

| r | r | r | |

| Age (years) | 0.383*** | 0.778 *** | 0.859*** |

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 0.202*** | 0.377*** | 0.345*** |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | -0.051NS | 0.234*** | 0.273*** |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) | -0.131** | -0.301 *** | -0.160 *** |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | -0.165*** | -0.090 * | -0.156** |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | -0.027NS | -0.288*** | -0.256*** |

| Serum tryglicerides (mg/dL) | 0.090NS | 0.088NS | 0.147** |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.466*** | 0.127** | 0.177 *** |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | -0.520*** | -0.254 *** | -0.338 *** |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | -0.024NS | -0.085NS | -0.009NS |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 0.086NS | 0.088NS | 0.084NS |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 0.188*** | 0.236 *** | 0.156*** |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | -0.015NS | -0.163*** | -0.247*** |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 0.083NS | 0.014NS | -0.076NS |

| Pulse Pressure (mmHg) | 0.250*** | 0.430*** | 0.395*** |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | -0.046NS | -0.074NS | -0.094* |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.717*** | 0.407*** | 0.404*** |

|

***: p ≤ 0.001; **: p ≤ 0.01; *: p ≤ 0.05; NS: p > 0.05 Abbreviations: ASCVD: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease; LDL-c: Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; eGFR: estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; BP: Blood Pressure; 8-iso-PGF2α: 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α; CRP: C-Reactive Protein | |||

|

[A] Outcome variable: Framingham Risk Score |

Regression coefficients | ||||

| Standardized | |||||

| Β | β | t | p-value | ||

| Model (R2 = 0.938) | |||||

| Age | 0.024 | 0.683 | 45.810 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 0.274 | 0.326 | 24.988 | < 0.001 | |

| Systolic BP | 0.005 | 0.277 | 21.928 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex (male) | 0.178 | 0.240 | 18.354 | < 0.001 | |

| Smoking habit | 0.166 | 0.165 | 12.780 | < 0.001 | |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.002 | 0.079 | 5.844 | < 0.001 | |

| Serum total cholesterol | 0.001 | -0.059 | -4.357 | 0.001 | |

| eGFR | <0.001 | 0.066 | 4.128 | 0.001 | |

| 8-iso-PGF2α | <0.001 | 0.052 | 3.236 | 0.001 | |

| Constant | -1.582 | - | -27.712 | < 0.001 | |

|

[B] Outcome variable: ASCVD risk score |

Regression coefficients | ||||

| Standardized | |||||

| Β | β | t | p-value | ||

| Model (R2 = 0.969) | |||||

| Age | 0.038 | 0.891 | 82.357 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 0.245 | 0.244 | 26.431 | <0.001 | |

| Sex (male) | 0.207 | 0.232 | 25.019 | <0.001 | |

| Systolic BP | 0.005 | 0.216 | 24.131 | <0.001 | |

| Serum total cholesterol | 0.002 | 0.177 | 18.455 | <0.001 | |

| HDL cholesterol | -0.006 | -0.168 | -17.513 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking habit | 0.072 | 0.060 | 6.562 | <0.001 | |

| Antihypertensive therapy | 0.129 | 0.057 | 6.482 | <0.001 | |

| eGFR | <0.001 | 0.036 | 3.150 | 0.002 | |

| 8-iso-PGF2α | <0.001 | 0.026 | 2.285 | 0.023 | |

| Constant | -2.384 | - | -43.679 | <0.001 | |

| Abbreviations: BP: Blood Pressure; HDL: High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; eGFR: estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; 8-iso-PGF2α: 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α; ASCVD: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).