1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus has resulted not only in millions of cases and deaths worldwide, but has also exposed hidden vulnerabilities in reproductive healthcare, particularly for women [

1]. While initial attention was focused on the respiratory system, it soon became evident that the infection has systemic effects on the body, including the endocrine, vascular, and reproductive systems [

2,

3,

4].

According to the World Health Organization, women of reproductive age represent a particularly vulnerable group, as COVID-19 can disrupt menstrual cycles, alter hormonal balance, and cause inflammatory changes in the pelvic organs and mammary glands [

5]. These disturbances may persist for months after recovery and potentially affect fertility, quality of life, and the need for specialized medical care.

Of particular concern is the fact that most post-COVID changes in women are identified at later stages—either incidentally or during routine examinations. To date, it remains poorly understood how frequently such structural changes occur, what they are associated with, and what mechanisms underlie their development [

6]. Data obtained through objective instrumental methods—such as ultrasound examination (US), laboratory diagnostics, and hormonal screening—are especially limited.

Key terms in the context of this study include:

Structural changes — anatomical and morphological abnormalities detected by ultrasound in the pelvic organs and mammary glands.

Women of reproductive age — as defined by the WHO, women aged 15 to 49 years [

7].

Post-COVID changes — symptoms or clinical manifestations that persist or emerge after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, including those affecting non-respiratory organs [

8].

Therefore, the problem addressed in this study is the insufficient exploration of the long-term effects of COVID-19 in women, particularly in terms of structural abnormalities in organs critical for reproductive and overall health. Timely detection and evaluation of such changes are essential for developing clinical guidelines and planning post-COVID rehabilitation programs.

The focus of our study is to identify and analyze possible morphological changes in the pelvic organs and mammary glands of women who have recovered from COVID-19 using objective diagnostic methods, including ultrasound imaging and laboratory testing.

To date, there is a limited number of studies in the global scientific literature that focus on the impact of COVID-19 on the female reproductive system, particularly in the long term. Most of these studies are either reviews or descriptive in nature and rely primarily on patient self-reports or data from medical registries [

9,

10].

According to published systematic reviews, COVID-19 may be accompanied by menstrual irregularities, decreased ovarian reserve, exacerbation of chronic gynecological conditions, and fibrocystic breast disease [

11,

12]. Some authors have reported an increased incidence of follicular cysts, uterine fibroids, and endometrial hyperplasia in women after COVID-19 [

13]. However, these studies typically lack a standardized approach to instrumental and laboratory diagnostics.

Our own study, conducted in 2023, confirmed that a number of women with post-COVID syndrome report persistent reproductive issues, including structural changes in the pelvic and breast organs. However, these observations require objective verification through ultrasound imaging and laboratory testing [

3,

8].

Among the few original studies, the work by Ermakova D. et al. (2022) deserves attention. It demonstrated altered expression of reproductive hormones in women who had recovered from COVID-19, including reduced anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and increased follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels [

14]. Another study by Demir et al. (2021) documented statistically significant changes in endometrial thickness among women post-COVID [

17]. Despite these findings, comprehensive studies covering the full range—from clinical manifestations to ultrasound and biochemical characteristics—remain rare.

Thus, literature analysis reveals the presence of some clinical observations, yet a substantial gap exists in objective data derived from standardized ultrasound and laboratory evaluations. This is the gap the present study aims to fill through the application of a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

Despite the existence of several clinical observations and descriptive reviews on women’s reproductive health after COVID-19, several unresolved questions remain. Most existing publications are based on subjective patient complaints, surveys, or general epidemiological data without objective assessment of the reproductive organs.

It is also worth noting that many studies are based on small sample sizes, predominantly retrospective in design, with heterogeneous patient groups and a lack of properly structured control comparisons. This significantly limits the generalizability of the findings to a broader population.

Furthermore, most studies fail to account for the time elapsed since infection—analyses are often conducted either immediately after recovery or long afterward, complicating the establishment of causal relationships. Only a few studies focus on structural changes in the pelvic and breast organs, and ultrasound and laboratory diagnostics are rarely used as standardized assessment tools.

Therefore, there remains a significant gap in objective, clinically-instrumental data based on comparative analysis between women who had COVID-19 and healthy controls.

It remains unknown whether the observed changes are transient or persistent, and to what extent they are associated with the severity of the disease, the presence of post-COVID syndrome, or hormonal dysregulation [

15,

16].

The present study aims to fill the gap in objective data on structural changes in the pelvic organs and mammary glands of women of reproductive age following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Unlike previous research, our study employed a standardized diagnostic protocol, including ultrasound imaging and laboratory assessment of hormonal and metabolic markers, ensuring high reproducibility and reliability of the collected data. [

17,

18].

In addition, to enhance scientific rigor, a control group matched by age and other relevant characteristics was established, allowing for an objective comparison between women who had recovered from COVID-19 and those who had never been infected [

19].

The study’s hypothesis is that women of reproductive age who have recovered from COVID-19 exhibit a higher frequency of morphological abnormalities in the pelvic and breast organs compared to conditionally healthy women. This may be a consequence of systemic inflammation, microcirculatory disturbances, and hormonal imbalance caused by the infection [

20]. The past COVID-19 infection in pregnant women have long-term consequences in the form of placenta abnormal development and oligohydramnios, and as a result, the development of adverse perinatal outcomes [

21].

It is expected that the findings of this study will help clarify the spectrum of structural changes occurring in the pelvic organs and mammary glands during the post-COVID period, establish a potential link between previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and reproductive disorders, and provide a basis for developing recommendations for clinical monitoring, early detection, and complication prevention [

22,

23].

Thus, the present work is not only aimed at describing clinical and instrumental changes but also at creating a scientific foundation for improving healthcare and developing rehabilitation strategies for women of reproductive age who have recovered from COVID-19 amid an ongoing global epidemiological challenge [

24].

This article presents an original prospective study, the objective of which was to conduct a comprehensive assessment of structural abnormalities in the pelvic organs and mammary glands of women of reproductive age who had recovered from COVID-19, in comparison to women with no history of the disease.

The study included 300 women aged 18 to 45 years, of whom 150 had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 (main group), and 150 had never had the infection (control group). All participants underwent a standardized clinical and laboratory examination, including hormone level assessment, biochemical analysis, and ultrasound imaging of the pelvic organs and mammary glands [

26].

The study was conducted at a specialized medical facility in the Republic of Kazakhstan in 2023, in accordance with all ethical guidelines and protocols. The collected data were subjected to statistical analysis to identify significant differences between the groups and to determine possible associations between previous infection and the observed changes [27].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted involving 150 women of reproductive age, divided into two groups. The main group (post-COVID) included 75 women who had recovered from PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection between 2021 and 2022. The control group comprised 75 women with no history of COVID-19 and no chronic reproductive health conditions.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Post-COVID group: Data were collected from 110 women who had been hospitalized in Almaty with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during 2021–2022. Of these, 75 agreed to participate in the full clinical and laboratory assessment.

Control group: A digital questionnaire was distributed via WhatsApp messenger, yielding 1,170 responses. After excluding individuals who reported a history of COVID-19, we randomly selected 75 women who met the inclusion criteria (18–45 years old, no chronic reproductive diseases, living in Almaty, and signed informed consent).

Given the constraints imposed by the pandemic and the need for rapid and cost-effective outreach, WhatsApp Messenger was selected as a primary platform for participant recruitment. This application is widely used in Kazakhstan and allowed direct access to a diverse population of women of reproductive age residing in Almaty. The method enabled efficient distribution of the digital screening questionnaire while maintaining participant anonymity at the initial stage. To minimize selection bias, all respondents were screened based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only those who explicitly consented to participate and met the eligibility requirements were contacted for further clinical evaluation. Ethical considerations were strictly adhered to, and the recruitment process was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. IRB-253-2024).

2.3. Ethical Approval

All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion. The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Kazakhstan Medical University “Higher School of Public Health” (Protocol Number: IRB-253-2024), and the investigations were carried out following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The use of digital recruitment tools, including WhatsApp Messenger, was approved as part of the ethical review.

2.4. Ultrasound Examinations

All participants underwent standardized ultrasound examinations of the pelvic organs and mammary glands using a Samsung WS80A diagnostic ultrasound system. Scans were performed by certified sonographers in a clinical setting using a 3.5 MHz transabdominal probe for pelvic imaging and a 7.5–10 MHz linear probe for breast imaging. All ultrasound procedures followed international protocols and classification systems to ensure diagnostic consistency and reproducibility.

Pelvic scan: Transabdominal scans were performed with participants maintaining a full bladder to optimize visualization. Assessment included uterine size and position, endometrial thickness, ovarian morphology, and the presence of structural abnormalities such as ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, pelvic varicosities, and suspected endometriosis. The classification of abnormalities was based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system for uterine disorders, and the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) simple rules were applied where relevant.

Breast scan: Bilateral breast ultrasound was conducted in a supine-oblique position using a high-frequency linear probe. Structural changes such as simple or complex cysts, fibrocystic changes, and solid masses were evaluated and categorized according to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) developed by the American College of Radiology. Suspicious findings were documented in detail, and BI-RADS category 3 or above was considered clinically relevant.

2.5. Laboratory Assessments

Blood samples were collected from all participants under standardized conditions by trained medical staff. For the control group, venous blood was drawn on days 3 to 7 of the menstrual cycle to ensure hormonal stability; in the post-COVID group, sampling was performed irrespective of cycle phase due to menstrual irregularities reported after infection. All laboratory analyses were carried out at the “Sapa” Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory (Almaty, Kazakhstan), a certified and ISO-compliant facility accredited for clinical biochemical and immunological diagnostics. The following biomarkers were analyzed: reproductive hormones including estradiol (pg/mL), progesterone (ng/mL), prolactin (ng/mL), and anti-müllerian hormone (AMH, ng/mL), measured using chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA, Beckman Coulter Access 2); thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, mIU/L), assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, DRG Instruments GmbH); and inflammatory and coagulation markers, including ferritin (µg/L), fibrinogen (g/L), D-dimer (ng/mL), and C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/L), analyzed using automated immunoturbidimetric and photometric assays (Abbott Architect and Sysmex CS-2500). All tests were performed in duplicate to ensure accuracy and internal validity, with inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation maintained below 10%. Quality control procedures included daily verification using calibrators and control samples provided by the assay manufacturers.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 20.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. As most variables were non-normally distributed, data are presented as median values with interquartile ranges (Q1–Q3), and group comparisons were conducted using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Ultrasound Examination of the Pelvic Organs

The mean age of participants in both groups was 33.5 ± 12.8 years. Among the 150 women assessed (75 with a confirmed history of COVID-19 and 75 controls), structural abnormalities in pelvic organs were significantly more prevalent in the post-COVID group (53.5%) compared to the control group (12.0%, p < 0.001).

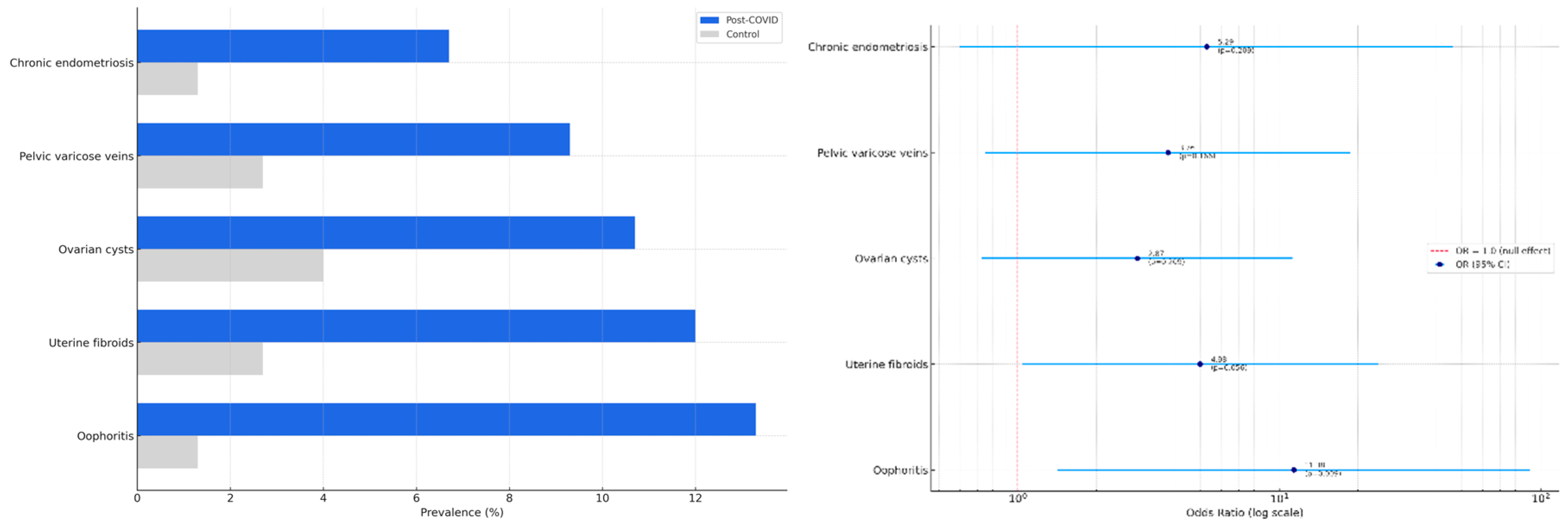

Ultrasound examination revealed that oophoritis was significantly more frequent in the post-COVID group (13.3%) than in controls (1.3%), with an odds ratio (OR) of 11.38 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.42–91.36, p = 0.009). Other abnormalities were also observed more commonly in the post-COVID group: uterine fibroids (12.0% vs. 2.7%; OR = 4.98, 95% CI: 1.04–23.88; p = 0.056), ovarian cysts (10.7% vs. 4.0%; OR = 2.87, p = 0.209), pelvic varicose veins (9.3% vs. 2.7%; OR = 3.76, p = 0.166), and chronic endometriosis (6.7% vs. 1.3%; OR = 5.29, p = 0.209). However, these differences did not reach statistical significance, although the trend for uterine fibroids was borderline.

These findings are summarized in

Table 1, and visualized in

Figure 1A, which displays the comparative prevalence of abnormalities in each group, and

Figure 1B, which shows the corresponding odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

3.2. Breast Ultrasound

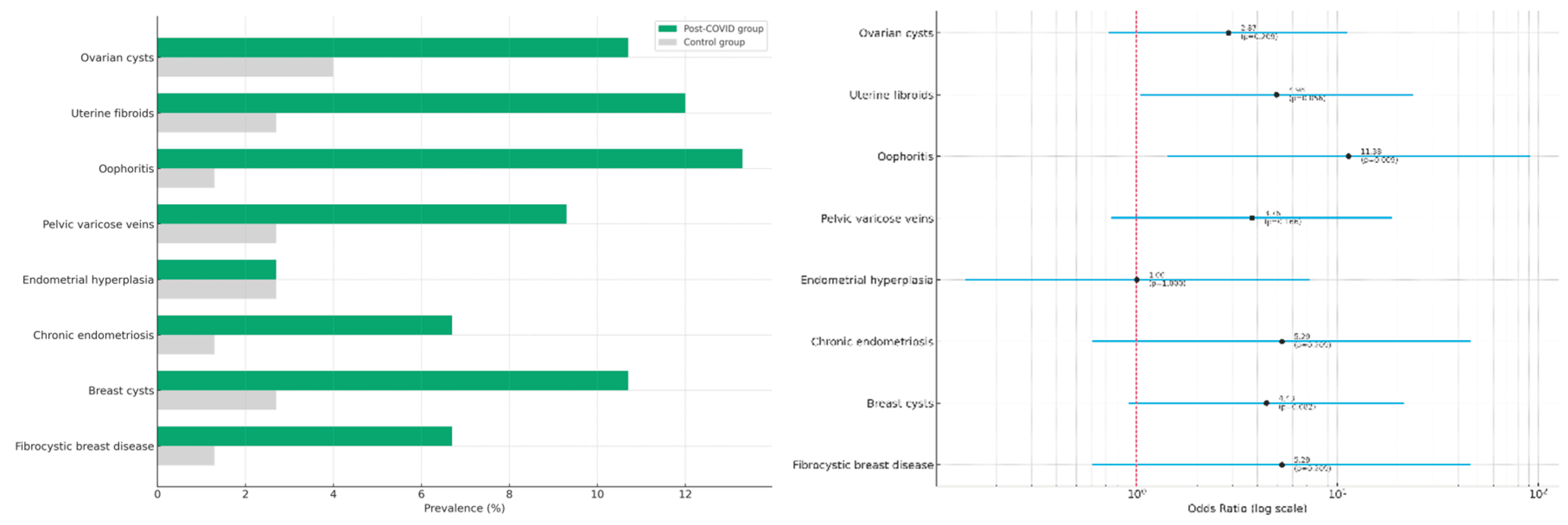

In addition to pelvic organ abnormalities, the study evaluated potential structural changes in the breast tissue of women with and without a history of COVID-19. This was motivated by increasing clinical reports of post-infectious mastopathy and breast cyst formation following viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2.

Ultrasound assessment of the mammary glands revealed a higher frequency of structural abnormalities in the post-COVID group. Specifically, breast cysts were detected in 10.7% of women with a history of COVID-19 compared to 2.7% in the control group (OR = 4.43; 95% CI: 0.91–21.53; p = 0.082). Fibrocystic breast disease was observed in 6.7% of post-COVID participants versus 1.3% in controls (OR = 5.29; 95% CI: 0.60–46.38; p = 0.209). Although these differences did not reach statistical significance, they reflect a consistent trend similar to the pelvic findings.

A comparative summary of all structural abnormalities identified in both pelvic and breast tissues is presented in

Table 2. Visual representations are shown in

Figure 2A (prevalence by group) and

Figure 2B (odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals).

These findings suggest that women of reproductive age who have recovered from COVID-19 may be at increased risk of developing structural abnormalities in both pelvic and breast tissues. While only oophoritis demonstrated a statistically significant association, the observed trends point toward a potentially greater inflammatory or hormonal burden in the post-COVID group. These results highlight the importance of integrated gynecological and breast health surveillance in women after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In addition to structural abnormalities, we examined potential biochemical and hormonal alterations associated with COVID-19. A panel of reproductive hormones and inflammatory markers was analyzed in both groups to explore possible endocrine and metabolic effects of the virus.

The results are summarized in

Table 3, with corresponding non-parametric comparisons using the Mann–Whitney U-test shown in

Table 4.

Descriptive analysis of hormonal and inflammatory markers revealed several notable differences between the post-COVID and control groups (

Table 3). Women with a history of COVID-19 had higher levels of serum ferritin (median 420.0 μg/L vs. 311.0 μg/L) and estradiol (57.0 pg/mL vs. 11.2 pg/mL), while TSH levels were lower (3.30 mIU/L vs. 3.70 mIU/L). Progesterone and AMH levels were also slightly reduced in the post-COVID group, suggesting possible alterations in ovarian reserve and luteal function. Inflammatory markers such as fibrinogen were elevated post-COVID, which may reflect residual subclinical inflammation. These findings provide pre liminary evidence of post-infectious endocrine disruption in women of reproductive age. Statistical comparison using the Mann–Whitney U-test is presented in

Table 4 to assess the significance of observed biomarker shifts between groups.

The results of this study demonstrate that women of reproductive age with a history of COVID-19 exhibit a higher prevalence of structural abnormalities in both the pelvic organs and mammary glands compared to non-infected controls. The only statistically significant association was observed for oophoritis (OR = 11.38, p = 0.009), while other abnormalities, including uterine fibroids, breast cysts, and fibrocystic disease, showed non-significant but consistent upward trends in the post-COVID group.

In addition to anatomical findings, the post-COVID group demonstrated altered profiles of reproductive hormones and inflammatory markers, notably elevated serum ferritin, estradiol, and fibrinogen levels, and reduced TSH and AMH levels. These results may indicate a lingering inflammatory or endocrine imbalance following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Together, these observations underscore the potential long-term reproductive and hormonal effects of COVID-19 and highlight the need for ongoing gynecological and endocrine monitoring in affected women.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the potential structural, hormonal, and inflammatory changes in women of reproductive age following COVID-19 infection. Among the 150 participants, women with a history of COVID-19 demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of pelvic abnormalities compared to the control group (53.5% vs. 12.0%; p < 0.001), with oophoritis being the only statistically significant abnormality identified (OR = 11.38; p = 0.009). Although other structural abnormalities—including ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, and breast cysts—did not reach statistical significance, they showed consistent upward trends in the post-COVID group.

These findings support the hypothesis of a possible post-viral impact of SARS-CoV-2 on female reproductive organs. The observed pelvic and breast abnormalities may be related to viral-induced inflammation, immune dysregulation, or hormonal disturbances, which is in line with other reports on long COVID effects in women [

8,

9,

13]. A recent review also pointed to the growing evidence of fibrocystic mastopathy and ovarian cysts post-COVID, mirroring our findings [

6,

14]. Moreover, population-level data from Kazakhstan highlighted rising trends in breast disease burden, underlining the importance of integrated reproductive health surveillance.

From a biochemical perspective, we found elevated levels of serum ferritin, estradiol, and fibrinogen in the post-COVID group. These markers are commonly associated with systemic inflammation and coagulopathies, which have been well documented in COVID-19 pathophysiology [2–4, 23]. Fibrinogen elevation, in particular, is a known contributor to hypercoagulability and thrombotic risk in SARS-CoV-2 infection [

25]. Decreased TSH levels observed in our study may reflect post-viral thyroid dysfunction, a condition previously reported in COVID-19 survivors [10, 12, 19].

Our results are consistent with other studies documenting menstrual irregularities, altered hormonal profiles, and diminished ovarian reserve following SARS-CoV-2 infection [5, 11, 14]. For example, Li et al. reported significant disruptions in estradiol and AMH levels in women with COVID-19 [

10], while Ranjbar et al. observed changes in menstrual cycles in over 40% of Iranian women during the pandemic [

11]. These hormonal disruptions may stem from direct viral effects on endocrine organs or from hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis dysregulation [12, 13, 17].

The only statistically significant structural abnormality in our cohort—oophoritis—could represent a localized inflammatory response or immune-mediated ovarian damage. This aligns with findings from Ermakova et al., who also noted impaired ovarian reserve and increased antral follicle loss in post-COVID women [

14].

Based on our results, we recommend individualized monitoring for women post-COVID-19, especially those with menstrual disturbances or unexplained pelvic symptoms. Routine ultrasound screening, in combination with hormonal profiling, could help detect subclinical reproductive alterations. These findings may also inform preconception care programs for COVID-19 survivors [

16].

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, limiting statistical power to detect differences in less common conditions. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Additionally, hormonal sampling in the post-COVID group was not standardized to the menstrual cycle due to reported irregularities, which may have introduced variability.

Our findings suggest that COVID-19 may exert long-term effects on female reproductive and endocrine health. The combination of structural abnormalities, altered hormone levels, and systemic inflammatory markers supports the need for longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms underlying post-COVID reproductive dysfunction and developing evidence-based clinical guidelines for screening and management.