Submitted:

12 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

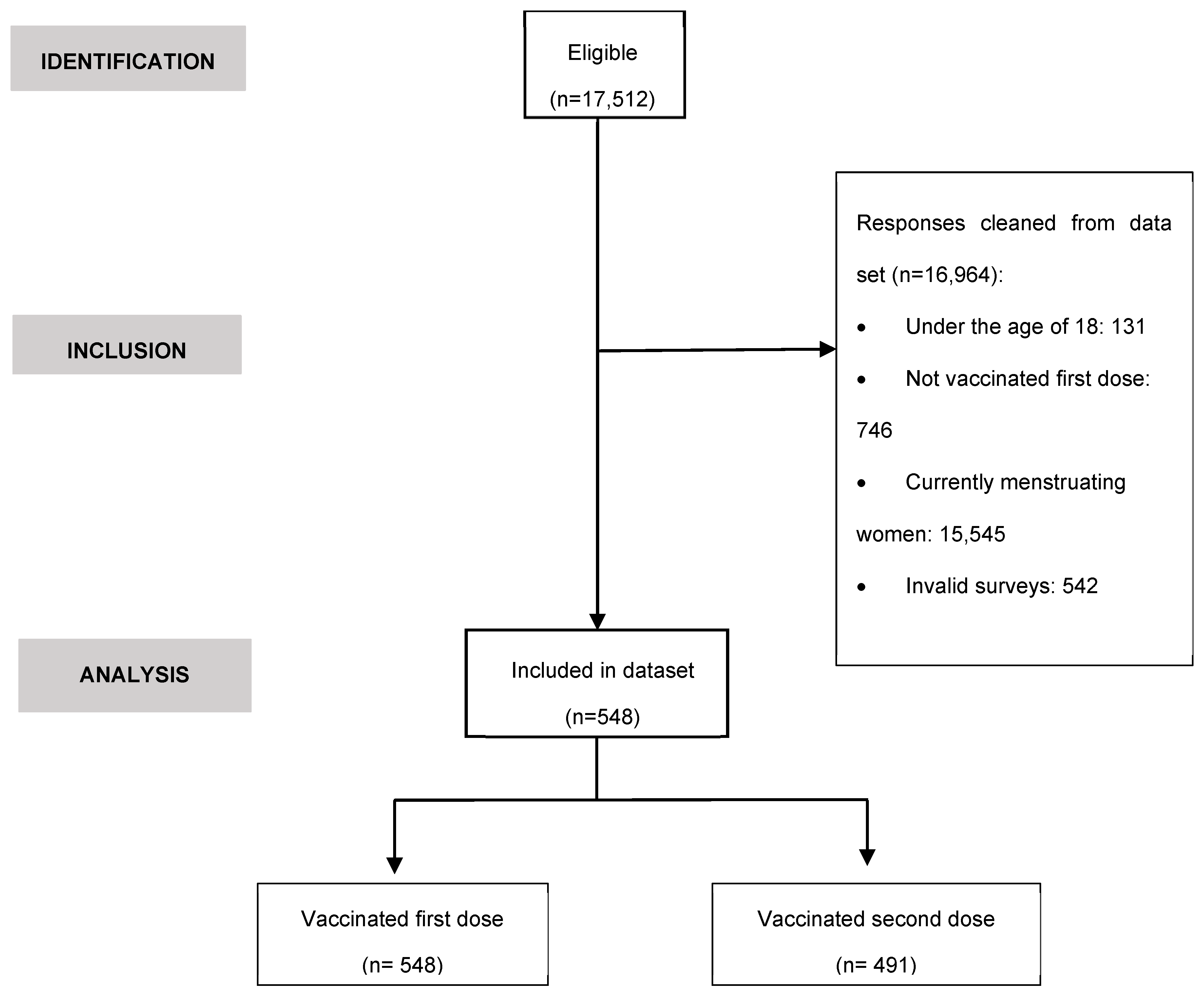

2.1. Experimental design

2.2. Recruitment, data collection and participants

2.3. Survey information

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthropometric characteristics and medical history

3.2. Impact of vaccination on the menstrual health of formerly menstruating women

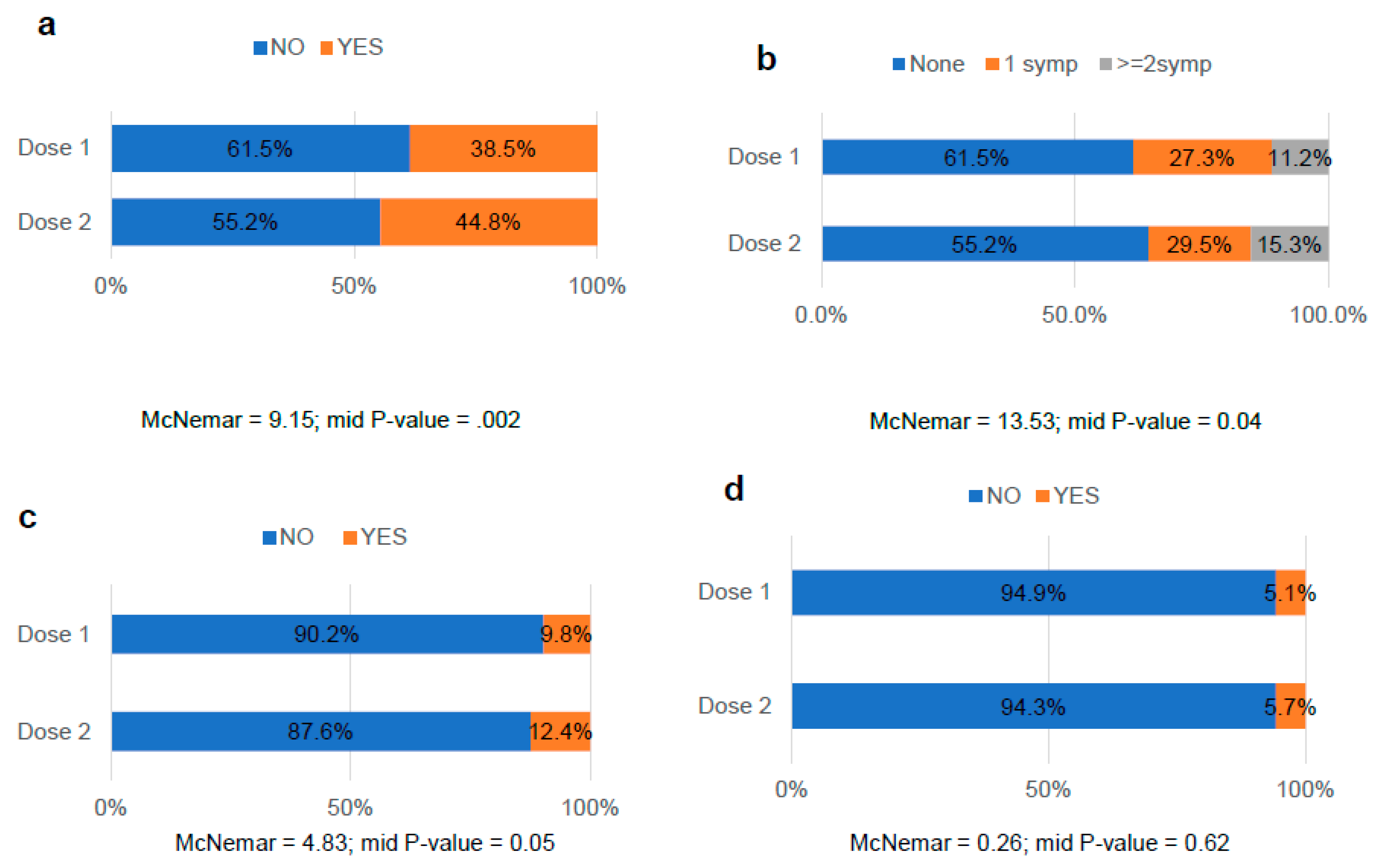

3.3. Comparative analysis of the occurrence of MRD after COVID-19 vaccination

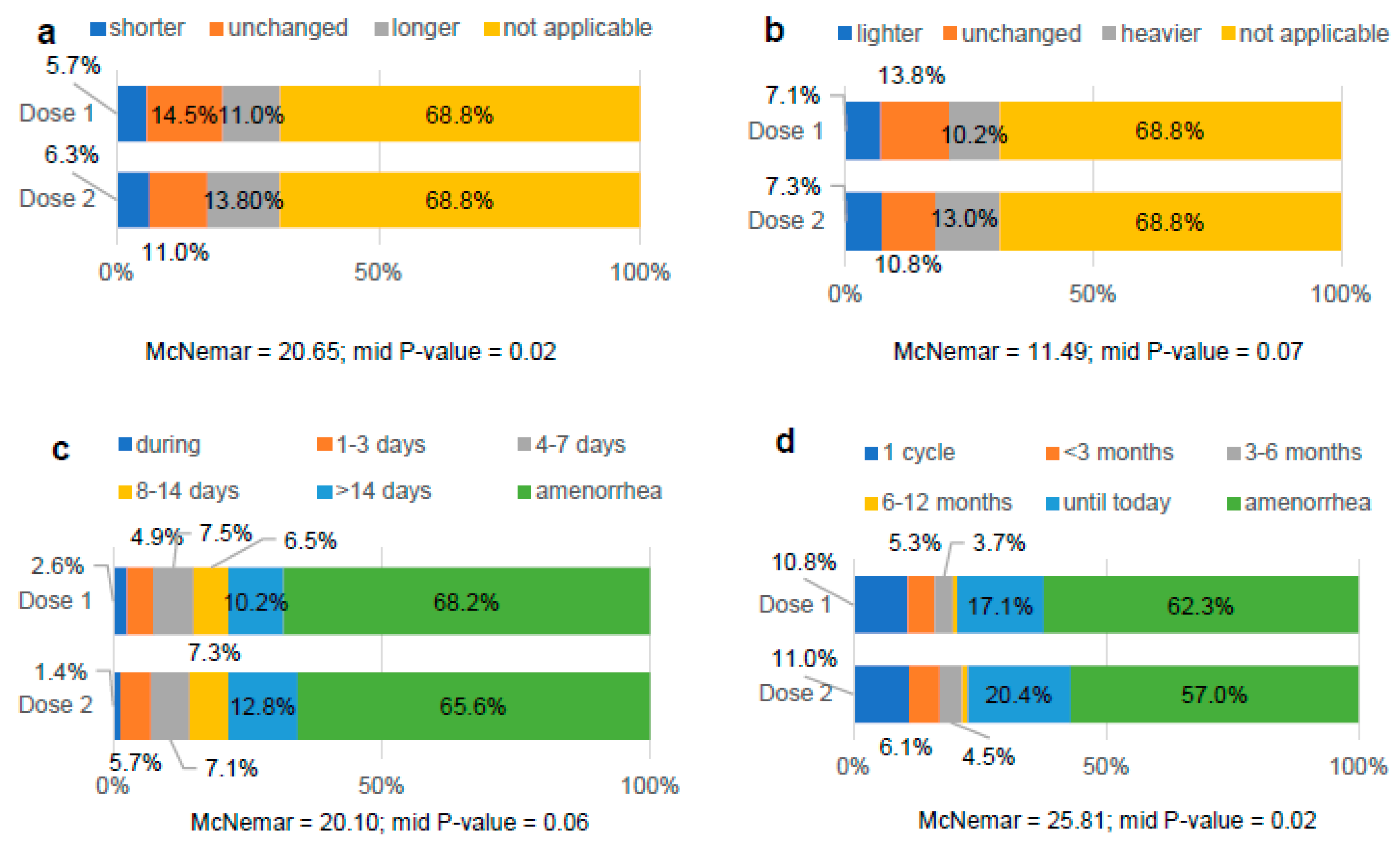

3.4. Comparative analysis of menstrual bleeding changes after COVID-19 vaccination

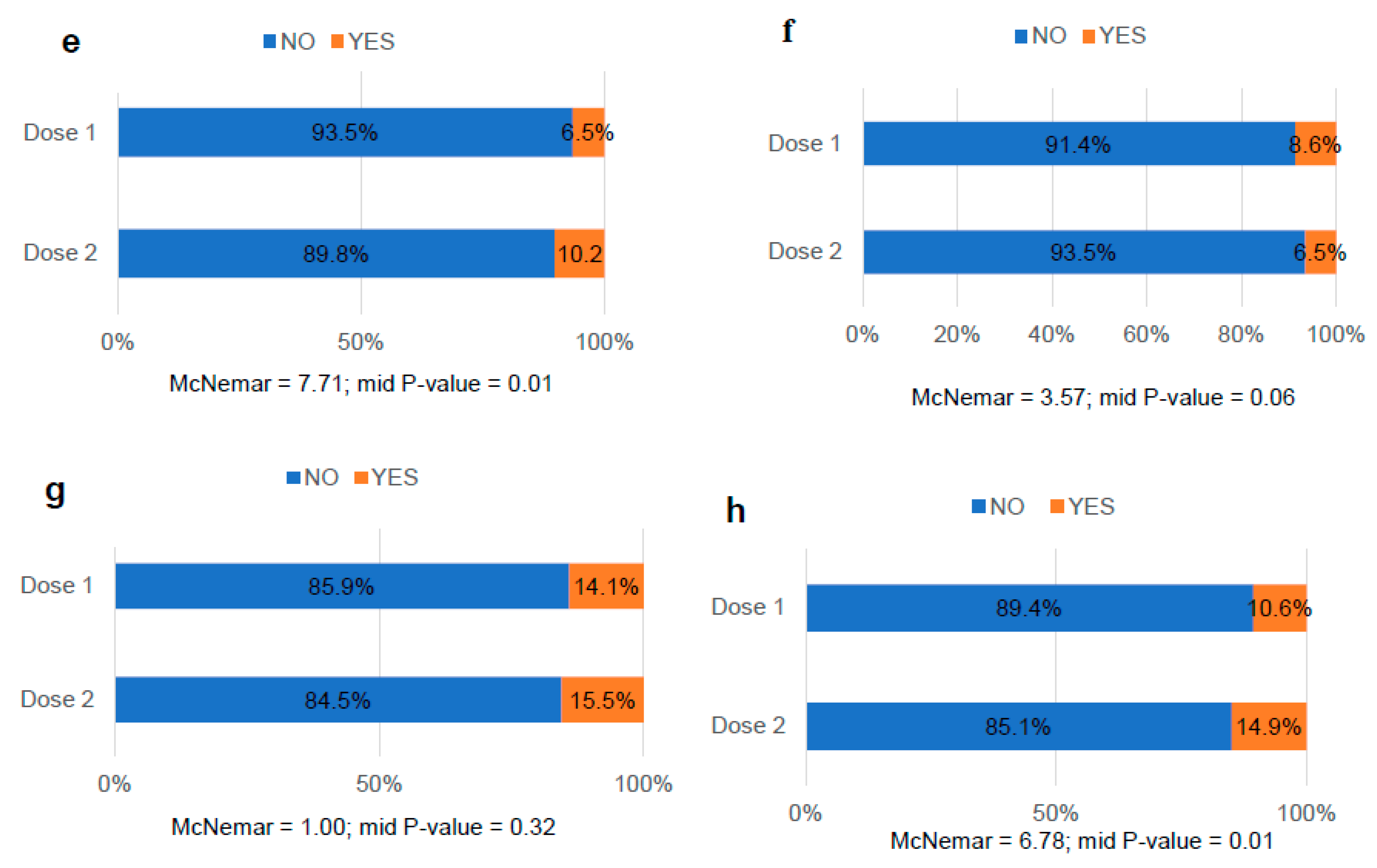

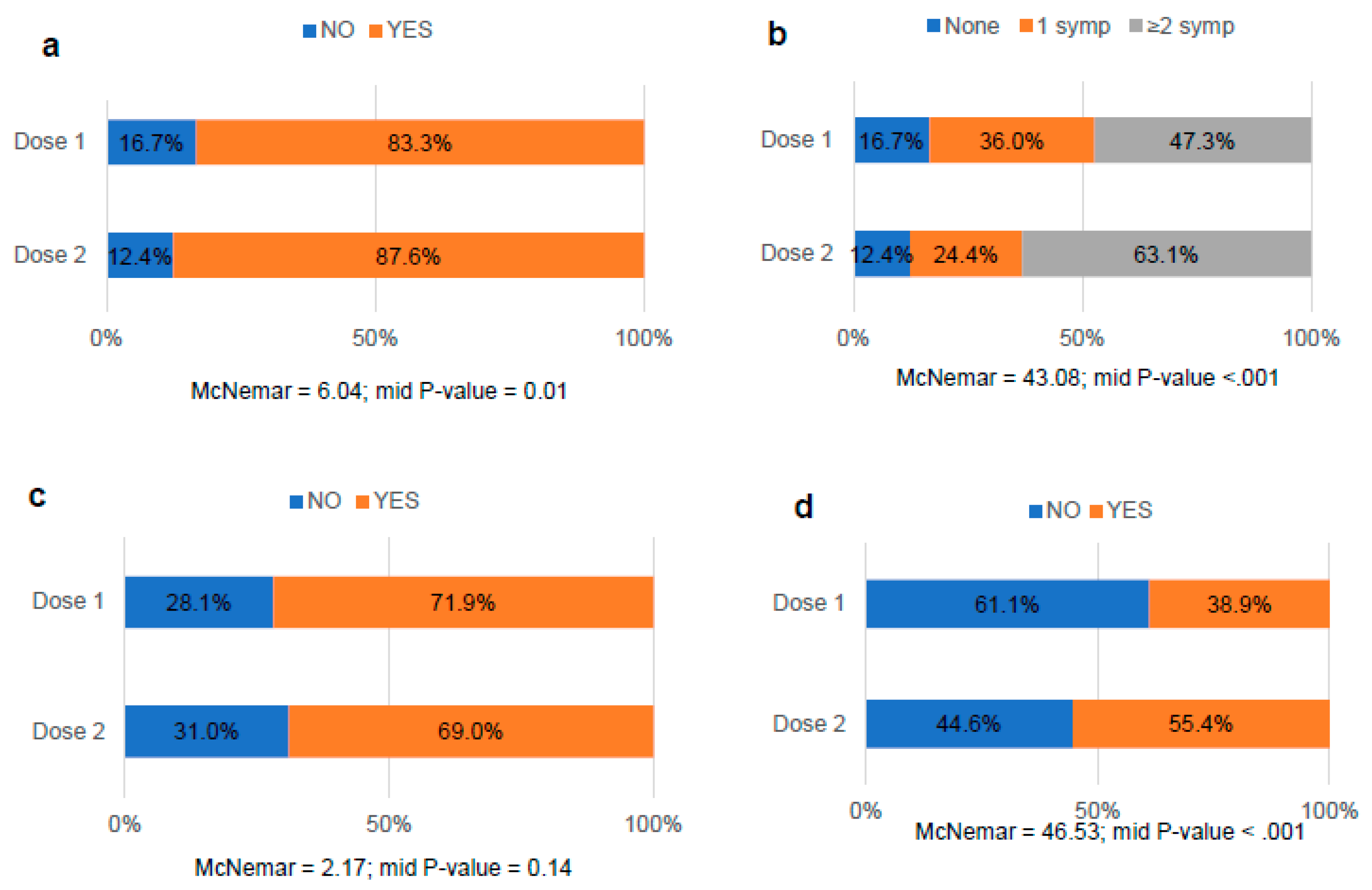

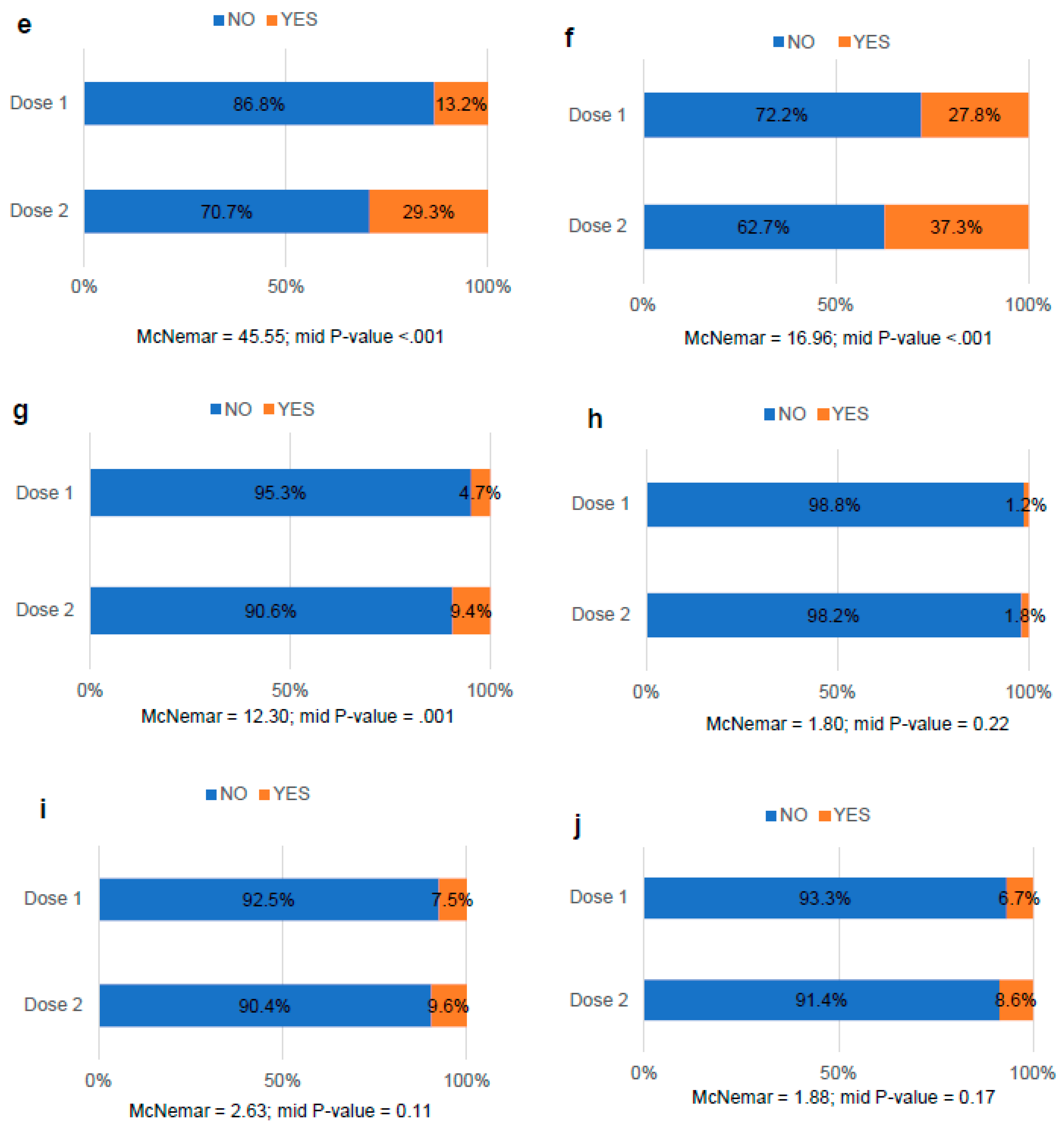

3.5. Comparative analysis of the side effects after COVID-19 vaccination

3.6. Factors associated with the occurrence or not of MRD after COVID-19 vaccination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silveira MM, Garcia Moreia GMS, Mendonça M. DNA vaccines against COVID-19: Perspectives and challenges. Life Sci 2021; 267. [CrossRef]

- Sharma O, Sultan AA, Ding H, et al. A Review of the Progress and Challenges of Developing a Vaccine for COVID-19. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 585354. [CrossRef]

- Mostaghimi D, Valdez CN, Larson HT, et al. Prevention of host-to-host transmission by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22(2): e52–e58. [CrossRef]

- Puhach O, Adea K, Hulo H, et al. Infectious viral load in unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals infected with ancestral, Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 2022; 28(7): 1491–1500. [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam A, Hakki S, Dunning J, et al. ATACCC Study Investigators. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22(2): 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N Engl J Med 2021;385(7):585-594. [CrossRef]

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). “Coronavirus vaccine—summary of yellow card reporting” (United Kingdom, 2022; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting).

- Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS). “17th COVID-19 vaccines pharmacovigilance report” (Government of Spain, 2022; https://www.aemps.gob.es/informa/17o-informe-de-farmacovigilancia-sobre-vacunascovid-19/).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). “COVID-19 vaccine safety report” (Australia Government, 2022; https://www.tga.gov.au/news/covid-19-vaccine-safety-reports/covid-19-vaccine-safety-report-06-10-2022).

- Male V. Menstrual changes after covid-19 vaccination. BMJ. 2021;374:n2211. [CrossRef]

- Morgan EP. “Periods: why women’s menstrual cycles have gone haywire”. The Guardian, March 25, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/mar/25/pandemic-periods-why-womens-menstrual-cycles-have-gone-haywire.

- Brumfiel G. “Why reports of menstrual changes after COVID vaccine are tough to study”. National Public Radio, August 9, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/08/09/1024190379/covid-vaccine-period-menstrual-cycle-research.

- Robinson O, Schraer R. “Covid vaccine: Period changes could be a short-term side effect”. British Broadcasting Corporation, May 13, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-56901353.

- Trogstad L, Laake I, Robertson AH, et al. “Increased incidence of menstrual changes among young women after coronavirus vaccination” (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, 2021; www.fhi.no/en/studies/ungvoksen/increased-incidence-of-menstrual-changes-among-young-women/).

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). “NOT-HD-21-035: notice of special interest (NOSI) to encourage administrative supplement applications to investigate COVID-19 vaccination and menstruation (admin supp clinical trial optional)” (United States Government, 2021; https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-HD-21-035.html).

- Edelman A, Boniface ER, Benhar E, et al. Association Between Menstrual Cycle Length and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination: A U.S. Cohort. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139(4):481-489. [CrossRef]

- Baena-García L, Aparicio VA, Molina-López A, et al. Premenstrual and menstrual changes reported after COVID-19 vaccination: The EVA project. Womens Health (Lond) 2022; 18:17455057221112237. [CrossRef]

- Critchley HOD, Babayev E, Bulun SE, et al. Menstruation: science and society. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223(5):624-664. [CrossRef]

- Sharp GC, Fraser A, Sawyer G, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the menstrual cycle: research gaps and opportunities. Int J Epidemiol 2022;51(3):691-700. [CrossRef]

- Muhaidat N, Alshrouf MA, Azzam MI, et al. Menstrual Symptoms After COVID-19 Vaccine: A Cross-Sectional Investigation in the MENA Region. Int J Womens Health 2022; 14:395-404. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Quejada L, Toro Wills MF, Martínez-Ávila MC, et al AF. Menstrual cycle disturbances after COVID-19 vaccination. Womens Health (Lond) 2022; 18:17455057221109375. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Mortazavi J, Hart JE, et al. A prospective study of the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination with changes in usual menstrual cycle characteristics. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(5): 739.e1–739.e11. [CrossRef]

- Alvergne A, Woon EV, Male V. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the timing and flow of menstrual periods in two cohorts. Front Reprod Health 2022; 4:952976. [CrossRef]

- Edelman A, Boniface ER, Male V, et al. Association between menstrual cycle length and covid-19 vaccination: global, retrospective cohort study of prospectively collected data. BMJ Med 2022;1(1): e000297. [CrossRef]

- Lee KMN, Junkins EJ, Luo C, et al. Investigating trends in those who experience menstrual bleeding changes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Sci Adv 2022;8(28): eabm7201. [CrossRef]

- Dabbousi AA, El Masri J, El Ayoubi LM, et al. Menstrual abnormalities post-COVID vaccination: a cross-sectional study on adult Lebanese women. Ir J Med Sci 2022; 26:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Laganà AS, Veronesi G, Ghezzi F, et al. Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: Results of the MECOVAC survey. Open Med (Wars) 2022;17(1):475-484. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi A, Naseh I, Kalroozi F, et al. Comparison of Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccines: Sinopharm, AstraZeneca, Sputnik V, and Covaxin in Women in Terms of Menstruation Disturbances, Hirsutism, and Metrorrhagia: A Descriptive-Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Fertil Steril 2022;16(3):237-243. [CrossRef]

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), “Amenorrhea” (United States Government, 2021; https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/amenorrhea).

- Lord M, Sahni M. “Secondary Amenorrhea” in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431055.

- Male V. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on menstrual periods in a retrospectively recruited cohort. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. “COVID-19 vaccination strategy” (Government of Spain, 2022; https://www.vacunacovid.gob.es).

- MM Al-Mehaisen L, A Mahfouz I, Khamaiseh K, et al. Short Term Effect of Corona Virus Diseases Vaccine on the Menstrual Cycles. Int J Womens Health 2022; 14:1385-1394. [CrossRef]

- Sualeh M, Uddin MR, Junaid N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Menstrual Cycle: A Cross-Sectional Study From Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus 2022;14(8): e28630. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Chen G, Hou H, et al. Analysis of sex hormones and menstruation in COVID-19 women of child-bearing age. Reprod Biomed Online 2021;42(1):260-267. [CrossRef]

- Perricone C, Ceccarelli F, Nesher G, et al. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) associated with vaccinations: a review of reported cases. Immunol Res 2014;60(2-3):226-35. [CrossRef]

- Merchant H. CoViD-19 post-vaccine menorrhagia, metrorrhagia or postmenopausal bleeding and potential risk of vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia in women. BMJ 2021;18.

- Kurmanova AM, Kurmanova GM, Lokshin VN. Reproductive dysfunctions in viral hepatitis. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016;32(sup2):37-40. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Updated Recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 Vaccine After Reports of Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Among Vaccine Recipients — United States, April 2021” (United States Government, 2021; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7017e4.htm?s_cid=mm7017e4_w).

- Long B, Bridwell R, Gottlieb M. Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome associated with COVID-19 vaccines. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 49:58-61. [CrossRef]

- Islam A, Bashir MS, Joyce K, et al. An Update on COVID-19 Vaccine Induced Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Syndrome and Some Management Recommendations. Molecules 2021;26(16):5004. [CrossRef]

- Schoenbaum EE, Hartel D, Lo Y, et al. HIV infection, drug use, and onset of natural menopause. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(10):1517-24. [CrossRef]

- Liaquat A, Huda Z, Azeem S, et al. Post-COVID-19 vaccine-associated menstrual cycle changes: A multifaceted problem for Pakistan. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022; 78:103774. [CrossRef]

- Popkin BM, Du S, Green WD, et al. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: A global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes Rev; 21(11):e13128. Epub 2020 Aug 26. Erratum in: Obes Rev 2021;22(10): e13305. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy M, Raval AP. The peri-menopause in a woman's life: a systemic inflammatory phase that enables later neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation 2020;17(1):317. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Total (N=548) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | - | 40.4±10.7 | |

| Weight (kg) a | - | 67.3±15.3 | |

| Height (cm)a | - | 164.2±6.3 | |

| BMI a,b | - | 25.0±5.5 | |

| Underweight | 32 (5.8) | ||

| Normal weight | 295 (53.8) | ||

| Pre-obesity/overweight | 118 (21.5) | ||

| Obesity I | 67 (12.2) | ||

| Obesity II | 21 (3.8) | ||

| Obesity III | 9 (1.6) | ||

| Medical history a,b | |||

| Autoimmune diseases | Diagnosis | Yes | 68 (12.4) |

| No | 480 (87.6) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 5 (7.4) | |

| No | 63 (92.6) | ||

| Types | Thyroid | 31 (5.4) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 14 (2.4) | ||

| Dermatological | 11 (1.9) | ||

| Rheumatic/articular | 7 (1.2) | ||

| None of the above | 7 (1.2) | ||

| Other clinical conditions | Diagnosis | Yes | 136 (25.0) |

| No | 407 (75.0) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 39 (27.7) | |

| No | 102 (72.3) | ||

| Types | Gynecological | 30 (22.1) | |

| Cancer | 19 (14.0) | ||

| Neurological/mental | 17 (12.5) | ||

| Rheumatic/articular | 16 (11.8) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 14 (10.3) | ||

| Respiratory | 14 (10.3) | ||

| Thyroid | 13 (9.6) | ||

| Dermatological | 6 (4.4) | ||

| HPV | 8 (5.9) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 7 (5.1) | ||

| None of the above | 37 (27.2) | ||

| Allergies | Diagnosis | Yes | 190 (34.7) |

| No | 358 (63.3) | ||

| COVID-19 | Diagnosis | Yes | 72 (13.1) |

| No | 476 (86.9) | ||

| Gynecological history a,b | |||

| Menarcheal age | 12.6±1.5 | ||

| Amenorrhea | Causes | Contraceptives | 162 (29.6) |

| Postmenopause | 95 (17.3) | ||

| Perimenopause | 92 (17.3) | ||

| Breastfeeding | 81 (14.8) | ||

| Hysterectomy | 7 (1.3) | ||

| None of the above | 111 (1.3) | ||

| Current/past use of contraceptives | Time of use | < 10 years | 161 (79.3) |

| > 10 years | 42 (20.7) | ||

| Types | None | 341 (62.2) | |

| Hormonal | 150 (27.4) | ||

| IUD (nonhormonal) | 57 (10.4) | ||

| Reproduction | Have you been pregnant? | Yes | 330 (60.2) |

| No | 218 (39.8) | ||

| Nº pregnancies | 0-2 | 470 (86.1) | |

| >2 | 76 (13.1) | ||

| Nº children | 0-2 | 523 (95.4) | |

| >2 | 25 (4.6) | ||

| Diseases | Diagnosis | Yes | 298 (54.4) |

| No | 250 (45.6) | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 70 (23.4) | |

| No | 229 (76.6) | ||

| Types | PCOS | 110 (36.8) | |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 105 (35.1) | ||

| Endometriosis | 57 (19.1) | ||

| Fibroids | 30 (10.1) | ||

| Menorrhagia | 21 (7.0) | ||

| Adenomyosis | 10 (3.3) | ||

| Uterine bleeding | 9 (3.0) | ||

| None of the above | 53 (17.7) |

| Variable | Category | Dose 1 (n=548) | Dose 2 (n=491) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | Yes | 517 (94.6) | 491 (89.6) |

| No | 31 (5.4) | 57 (10.4) | |

| Brand | Pfizer-BioNTech | 373 (68.1) | 352 (71.7) |

| Moderna | 95 (17.3) | 89 (18.1) | |

| Oxford-AstraZeneca | 54 (9.9) | 48 (9.8) | |

| None of the above | 26 (4.7) | 2 (0.4) |

| Dose1 | Dose2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | n-MRD (n=335) | MRD (n=213) | X2 | P-value | n-MRD (n=271) | MRD (n=220) | X2 | P-value | |

| Age (years)a | - | 40.6±11.1 | 40.0±9.9 | - | 0.66 | 40.4±11.6 | 40.2±9.7 | - | 0.91 | |

| Weight (kg)a | - | 65.4±24.5 | 70.3±15.9* | - | <.001 | 65.9±15.1 | 69.5±15.6• | - | 0.01 | |

| Height (cm)a | - | 163.9±6.2 | 164.6±6.3 | - | 0.18 | 164.0±6.0 | 164.4±6.5 | - | 0.78 | |

| BMI a,b | - | 24.3±5.2 | 26.0±5.8* | - | <.001 | 24.4±5.4 | 25.8±5.7• | - | 0.00 | |

| Underweight | 26 (7.8) | 6 (2.8)† | 13.96 | 0.03 | 18 (6.6) | 10 (4.5) | 7.46 | 0.28 | ||

| Normal weight | 190 (56.7) | 105 (49.3) | 153 (56.5) | 105 (47.7) | ||||||

| Pre-obesity /overweight | 66 (19.7) | 52 (24.4) | 55 (20.3) | 54 (24.5) | ||||||

| Obesity I | 37 (11.0) | 30 (14.1) | 28 (10.3) | 34 (15.5) | ||||||

| Obesity II | 10 (3.0) | 11 (5.2) | 9 (3.3) | 11 (5.0) | ||||||

| Obesity III | 3 (0.9) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.8) | ||||||

| Medical history b | ||||||||||

| Autoimmune diseases | Types | Thyroid | 14 (4.2) | 17 (8.0) | 0.08 | 0.77 | 14 (5.2) | 15 (6.8) | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Dermatological | 5 (1.5) | 6 (2.8) | 0.01 | 0.91 | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.7) | 0.96 | 0.33 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (1.5) | 9 (4.2) | 0.91 | 0.34 | 6 (2.2) | 7 (3.2) | 0.03 | 0.86 | ||

| Rheumatic / articular | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.9) | 0.06 | 0.81 | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.8) | 0.60 | 0.44 | ||

| None of the above | 4 (1.2) | 3 (1.4) | 0.32 | 0.57 | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 0.24 | 0.62 | ||

| Other clinical conditions | Types | Gynecological | 21 (6.3) | 9 (4.2) | 1.05 | 0.31 | 15 (5.5) | 13 (5.9) | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Cancer | 13 (3.9) | 6 (2.8) | 0.44 | 0.51 | 11 (4.1) | 7 (3.2) | 0.27 | 0.61 | ||

| Neurological / mental | 8 (2.4) | 9 (4.2) | 1.46 | 0.23 | 5 (1.8) | 12 (5.5)† | 4.73 | 0.03 | ||

| Thyroid | 8 (2.4) | 5 (2.3) | .001 | 0.98 | 6 (2.2) | 5 (2.3) | 0.00 | 0.97 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (2.1) | 8 (3.8) | 1.36 | 0.24 | 7 (2.6) | 5 (2.3) | 0.05 | 0.83 | ||

| Respiratory | 7 (2.1) | 7 (3.3) | 0.75 | 0.39 | 5 (1.8) | 6 (2.7) | 0.43 | 0.51 | ||

| Dermatological | 6 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | 0.66 | 0.42 | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.8) | 0.09 | 0.77 | ||

| Cardiovascular | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0.66 | 0.42 | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.8) | 0.09 | 0.77 | ||

| Rheumatic / articular | 5 (1.5) | 12 (5.6)• | 7.43 | 0.01 | 4 (1.5) | 12 (5.5)• | 6.10 | 0.01 | ||

| HPV | 5 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | .006 | 0.94 | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.4) | 0.47 | 0.49 | ||

| None of the above | 20 (6.0) | 18 (8.5) | 1.24 | 0.27 | 11 (4.1) | 21 (9.5)• | 6.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Allergies | - | 106 (31.6) | 84 (39.4) | 3.49 | 0.06 | 94 (34.7) | 74 (33.6) | 0.06 | 0.81 | |

| COVID-19 | - | 43 (12.8) | 29 (13.6) | 0.07 | 0.79 | 19 (7.0) | 13 (5.9) | 0.24 | 0.62 | |

| Gynecological history a,b | ||||||||||

| Menarcheal age | - | 12.7±1.4 | 12.5±1.7 | - | 0.18 | 12.6±1.5 | 12.6±1.6 | - | 0.69 | |

| Current/past use of contraceptives | Time of use | < 10 years | 88 (26.3) | 73 (34.3) | 0.32 | 0.57 | 61 (22.5) | 87 (39.5) | 3.43 | 0.06 |

| >10 years | 25 (7.5) | 17 (8.0) | 21 (7.7) | 15 (6.8) | ||||||

| Types | None | 219 (65.4) | 122 (57.3) | 3.63 | 0.16 | 186 (68.6) | 117 (53.2)• | 12.68 | .002 | |

| Hormonal | 84 (25.1) | 66 (31.0) | 60 (22.1) | 77 (35.0)• | ||||||

| IUD (nonhormonal) | 32 (9.6) | 25 (11.7) | 25 (9.2) | 26 (11.8) | ||||||

| Reproduction | Have you ever been pregnant? | Yes | 204 (60.9) | 126 (59.2) | 0.165 | 0.69 | 156 (57.6) | 134 (60.9) | 0.562 | 0.45 |

| No | 131 (39.1) | 87 (40.8) | 115 (42.4) | 86 (39.1) | ||||||

| Nº pregnancies | 0-2 | 290 (86.6) | 180 (84.5) | 0.399 | 0.53 | 234 (86.3) | 189 (85.9) | 0.014 | 0.91 | |

| >2 | 44 (13.1) | 32 (15.0) | 36 (13.3) | 6 (2.7) | ||||||

| Nº children | 0-2 | 314 (93.7) | 209 (98.1)• | 5.765 | 0.02 | 255 (94.1) | 214 (97.3) | 2.863 | 0.09 | |

| >2 | 21 (6.3) | 4 (1.9) | 16 (5.9) | 6 (2.7) | ||||||

| Amenorrhea | Types | Perimenopause | 41 (12.2) | 51 (23.9)* | 17.054 | <0.001 | 33 (12.2) | 47 (21.4)• | 10.596 | 0.01 |

| Postmenopause | 70 (20.9) | 25 (11.7)* | 57 (21.0) | 29 (13.2)• | ||||||

| None of the above | 224 (66.9) | 137 (64.3) | 181 (66.8) | 144 (65.5)• | ||||||

| Diseases | Types | Adenomyosis | 7 (2.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0.337 | 0.56 | 5 (1.8) | 5 (2.3) | 0.111 | 0.74 |

| PCOS | 67 (20.0) | 43 (20.2) | 0.003 | 0.96 | 61 (22.5) | 40 (18.2) | 1.392 | 0.24 | ||

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 57 (17.0) | 48 (22.5) | 2.562 | 0.11 | 44 (16.2) | 53 (24.1)† | 4.726 | 0.03 | ||

| Endometriosis | 30 (9.0) | 27 (12.7) | 1.934 | 0.16 | 21 (7.7) | 29 (13.2)† | 3.918 | 0.05 | ||

| Fibroids | 20 (6.0) | 10 (4.7) | 0.420 | 0.52 | 16 (5.9) | 13 (5.9) | 0.000 | 0.99 | ||

| Menorrhagia | 14 (4.2) | 7 (3.3) | 0.282 | 0.60 | 13 (4.8) | 7 (3.2) | 0.811 | 0.37 | ||

| Uterine bleeding | 7 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | 1.067 | 0.30 | 7 (2.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1.891 | 0.17 | ||

| None of the above | 37 (11.0) | 16 (7.5) | 1.860 | 0.17 | 28 (10.3) | 20 (9.1) | 0.212 | 0.65 | ||

| Side effects b | Types | Arm pain | 231 (69.0) | 167 (78.4)† | 5.847 | 0.02 | 180 (66.4) | 159 (72.3) | 1.946 | 0.16 |

| Fatigue | 126 (37.6) | 101 (47.4)† | 5.160 | 0.02 | 139 (51.3) | 133 (60.5)† | 4.126 | 0.04 | ||

| Headache | 78 (23.3) | 81 (38.0)* | 13.863 | <0.001 | 88 (32.4) | 95 (43.4)† | 5.957 | 0.02 | ||

| Fever | 41 (12.2) | 33 (15.5) | 1.181 | 0.28 | 76 (28.0) | 68 (30.9) | 0.481 | 0.49 | ||

| Swollen glands | 15 (4.5) | 27 (12.7)* | 12.367 | <0.001 | 18 (6.6) | 29 (13.2)• | 6.000 | 0.01 | ||

| Nauseas | 8 (2.4) | 20 (9.4)* | 13.166 | <0.001 | 20 (7.4) | 26 (11.9) | 2.817 | 0.09 | ||

| Breast lumps | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.3)* | 11.125 | 0.001 | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.1)* | 11.293 | 0.001 | ||

| None of the above | 19 (5.7) | 19 (8.9) | 2.129 | 0.15 | 22 (8.1) | 20 (9.1) | 0.147 | 0.70 | ||

| Dose 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | MRD (n=213) AOR (CI 95%) | P-value |

| Weight | - | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | <.001 |

| OCC rheumatic/articular | No | 0.31 (0.10-1.00) | 0.05 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Nº children | ≥ 2 | 0.25 (0.07-0.82) | 0.02 |

| 0-2 | 1 | ||

| Amenorrhea | Perimenopause | 2.28 (1.37-3.77) | .001 |

| Postmenopause | 0.74 (0.43-1.28) | 0.28 | |

| None of the above | 1 | ||

| Side effects | |||

| Arm pain | No | 0.61 (0.39-0.95) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Headache | No | 0.53 (0.35-0.80) | .003 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Swollen glands | No | 0.29 (0.15-0.59) | .001 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Nauseas | No | 0.35 (0.14-0.86) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Dose 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | MRD (n=220) AOR (CI 95%) | P-value |

| Alterations dose 1 | Yes | 13.88 (8.66-22.08) | <.001 |

| No | 1 | ||

| Contraceptives | Hormonal | 2.70 (1.54-4.76) | .001 |

| IUD | 1.85 (0.86-3.99) | 0.12 | |

| None | 1 | ||

| Amenorrhea | Perimenopause | 2.07 (1.06-4.06) | 0.03 |

| Postmenopause | 1.17 (0.60-2.29) | 0.64 | |

| None of the above | 1 | ||

| Arm pain | No | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).