1. Introduction

Black holes (BHs) provide a unique laboratory for testing theories of gravity in the strong-field regime, where quantum effects may become observable. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), using Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), has produced horizon-scale images of the supermassive black holes (SMBHs) Sgr A* and M87*, revealing features such as a central dark depression, a bright emission ring, and a base diameter [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These observations, with angular resolutions as fine as 19 µas, offer a unique opportunity to test GR against alternative gravity models, exotic compact objects (e.g., wormholes, naked singularities), and quantum gravity frameworks. The current literature uses EHT data to analyze shadow size, shape, and emission properties, constraining deviations from GR. It often combines this with GRMHD simulations to model accretion flows.

In this work, we re-examine the work by Marongwe [

12] in which the Nexus Paradigm (NP), a lattice gauge theory of quantum gravity in Clifford space, which models spacetime as a quantized crystal with

eigenstates [

12,

13,

14] claims a “99th percentile confidence interval” agreement with EHT data, but lacks detailed statistical analysis. The NP predicts distinct BH properties, including a halved Schwarzschild radius

and quantized orbital speeds

leading to specific angular diameters for SMBH features.

This paper conducts a Bayesian statistical analysis to rigorously test NP predictions against EHT observations for Sgr A* and M87*. We compute the posterior distribution for the angular scale parameter , assess goodness of fit using the statistic, and compare NP to GR. Our results quantify the NP’s consistency with observations in terms of sigma confidence levels, validating its claims and highlighting its advantages over GR.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sec. 1 we discuss the methodologies for testing gravity theories using the EHT observations. This section allows a broad understanding of testing gravity using EHT observations. We examine key studies in this regard taking into consideration their focus, findings and significance. We then investigate their limitations and challenges as well as future directions. In Sec. 2 we give an overview of the fundamental physics of the Nexus Paradigm (NP); its semi-classical version and in its full canonical quantized form. In Sec. 3 we outline the predictions of the Nexus paradigm. In Sec. 4 we discuss the data from the EHT observations. In Sec. 5 we implement the Bayesian analysis and in Sec. 6 we report the results of the analysis and draw concluding remarks and outline future directions.

1.1. Methodologies for Testing Gravity Theories

The primary methodology in the current literature involves comparing the observed black hole shadow size and shape with theoretical predictions from GR and alternative models. The shadow size is determined by the photon sphere, which depends on the spacetime metric, making it a sensitive probe for deviations from the Schwarzschild or Kerr solutions. Key approaches include:

Shadow Size Measurements: In which studies use the angular diameter of the shadow, calibrated by the mass-to-distance ratio of the black hole, to test theoretical models.

Parameterized Metrics: These are used to test deviations from GR. These include the Rezzolla-Zhidenko framework [

15] or the parameterized Schwarzschild metric (PSM) proposed by Tian & Zhu [

16]. These metrics introduce free parameters to model deviations from GR, which are then constrained by EHT data.

GRMHD Simulations: Since in GR the shadow is surrounded by emission from accreting matter, GRMHD simulations are used to model the observed ring and distinguish between gravitational and astrophysical effects[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

17]

Alternative Gravity Models and Exotic Objects: Here, studies test specific alternative theories (e.g., Einstein-Æther, quadratic gravity, mimetic gravity) and compact objects like wormholes or naked singularities by computing their shadow properties and comparing them to EHT observations[

17,

18]

1.2. Key Studies and Findings

The literature spans a range of gravity theories and compact objects, with EHT observations providing stringent constraints. In this section we summarise some pivotal studies. We examine their focus, findings and significance. One of the highly cited studies in this regard is the work by Vagnozzi et al. [

17]. This work focuses on a comprehensive study to test a broad array of deviations from GR using the EHT image of Sgr A*. It examines regular black holes (e.g., Bardeen, Hayward [

19,

20]), string-inspired spacetimes, violations of the no-hair theorem, and alternative gravity theories like beyond Horndeski models. It also tests black hole mimickers, such as the Damour-Solodukhin wormhole and naked singularities, using the shadow size and mass-to-distance ratio. The work finds that models predicting a shadow size larger than that of a Schwarzschild black hole are strongly constrained, with some constraints surpassing cosmological limits. However, certain mimickers, like wormholes, remain viable. A critique by Tsukamoto [

21] notes that the Damour-Solodukhin wormhole’s mass includes contributions from the parameter λ, challenging the study’s assumption of λ = 0. The significance of this study lies in that it highlights the power of EHT to probe a wide range of theoretical models, though its assumptions about mass parameters require careful consideration.

Another pivotal study is by Khodadi et al. [

18] which focuses on testing mimetic gravity, a modified theory related to GR via a non-invertible disformal transformation, using EHT images of M87* and Sgr A*. It examines naked singularities and black holes formed by non-trivial gluing procedures, computing their shadow properties. Khodadi et al. find that baseline mimetic gravity solutions (naked singularities and glued black holes) are inconsistent with EHT data, ruling them out. However, stealth Schwarzschild solutions with a trivial mimetic parameter (λ = 0) are allowed but cosmologically uninteresting. The study calls for exploring extensions of mimetic gravity. The importance of this work resides in that it demonstrates the complementarity of black hole imaging and cosmological tests in constraining modified gravity theories.

Marongwe [

12] focuses on testing the Nexus Paradigm, a quantum gravity model, against EHT images of Sgr A* and M87*. It compares the predicted angular diameter of the emission ring, central dark depression, and shadow base diameter with EHT data. The work finds that the Nexus Paradigm shows excellent agreement with EHT observations at the 99th percentile credibility interval, supporting its validity in the strong-field regime. More importantly, the work provides evidence for a quantum gravity framework. Unlike many theories that focus on general shadow size, the NP provides precise angular diameter predictions for the dark depression, emission ring, and base diameter, allowing for a more granular and unique comparison with EHT data.

J.Dass et al[

22] test Quadratic Gravity using the EHT observations. Quadratic Gravity is a perturbatively renormalizable quantum gravity theory. It constructs a phase space of static, spherically symmetric spacetimes, including horizonless objects and wormholes, and analyzes shadow size deviations from Schwarzschild predictions. It was found that Quadratic gravity solutions align with GR outside the photon sphere but deviate near the center. EHT data constrains these deviations, particularly through brightness within the shadow region. These findings highlight the sensitivity of shadow brightness to non-GR effects, offering a new avenue for testing quantum gravity.

Tian and Zhu [

16] proposes a Parametrized Schwarzschild Metric where the event horizon is located at

, with

n as a free parameter to test GR deviations. It uses M87* EHT data to explore whether the event horizon’s position differs from

. They find a value of n ≈ 2 could explain discrepancies in black hole mass measurements, suggesting possible deviations from GR in strong fields. Their work offers a simple framework for testing GR but requires further validation with Sgr A* data.

Khodadi et al. [

23] tests Einstein-Æther gravity, which allows Lorentz symmetry breaking, using M87* EHT data. It calculates the photon sphere radius and shadow size for two classes of black hole solutions. They find that the shadow size is sensitive to æther parameters, and EHT data constrains these parameters, providing insights into Lorentz-violating theories. Their work demonstrates EHT’s ability to test theories beyond GR that affect spacetime symmetries.

1.3. Synthesis of Findings

The literature collectively demonstrates that EHT observations are a powerful tool for testing gravity theories, particularly in the strong-field regime where GR predictions are most robust. The literature shows that models like baseline mimetic gravity and certain quadratic gravity solutions are ruled out or heavily constrained, while others, like the Nexus Paradigm , show promise. Exotic Objects that mimic black holes such as wormholes, remain viable in some cases but face challenges due to mass parameter dependencies . Findings from the literature also show that the shadow size and brightness are sensitive to spacetime geometry, but astrophysical effects (e.g., accretion) must be modelled carefully to isolate gravitational signals. In synthesis, the application of a comprehensive Bayesian analysis to evaluate the NP’s consistency with observational data is a modern and robust methodological novelty in this specific theoretical testing scenario.

1.4. Limitations and Challenges

Several limitations emerge across the literature. These include Mass-to-Distance Assumptions where many studies assume the mass-to-distance ratio is independent of the gravity theory, which may not hold for alternative models. This can lead to over-constrained or invalid conclusions. Astrophysical Uncertainties also present their challenges. GRMHD simulations rely on assumptions about accretion flows, which can obscure gravitational effects. Another limitation is that while EHT’s resolution is groundbreaking, subtle deviations from GR may require higher resolution or shorter-wavelength observations (e.g., 690 GHz).

1.5. Future Directions

The literature points to several avenues for future research. These include analysing time variability in EHT data that could probe accretion dynamics and further constrain gravity models. Including polarimetric EHT data can reveal magnetic field structures, providing additional constraints on non-GR spacetimes. Multi-Messenger Approaches which involve combining EHT data with gravitational wave observations (e.g., from LISA) could test gravity theories across different regimes . Finally, the next-generation EHT arrays or space-based VLBI could enhance sensitivity to subtle deviations from GR.

2. A synthesis of the Nexus Paradigm and its application to black hole physics

The Nexus Paradigm [

12,

13,

14] is a lattice gauge theory in Clifford space where space-time is represented as a space-time crystal with

eigenstates (see Ref.[

14] for the latest version). In theNP, locations in space-time are described using local coordinates rather than points in space. These localities are displacement vectors

characterized as quantized wave packets of space-time and can be expressed as Fourier integrals.

Here

are the Dirac matrices,

is the Hubble radius,

=

are Bloch energy eigenstate functions in which the four wave vectors assume the following quantized values

The quantized wave packets of spacetime have a minimum four-dimensional radius equivalent to the Planck 4-length and a maximum four-dimensional radius comparable to the Hubble 4-radius. The eigenstates emerge from the ratio of the Hubble four radius to the Planck four length. The Bloch functions in each eigenstate of spacetime generate an infinite Bravais four lattice.

The wave packet is a compact Einstein manifold, or a trivial Ricci soliton of positive Ricci curvature of the form.

Interestingly, there are two types of solitons; vacuum state solitons in which with a De Sitter topology and those associated with baryonic matter having an anti De Sitter topology with .The anti-De Sitter solitons are a family of concentric black hole like spherical surfaces of radii with corresponding orbital speeds of . The innermost marginally stable circular orbit occurs at half the Schwarzschild radius, implying that in the Nexus Paradigm, the event horizon is half the size predicted by GR. This distinctive characteristic should be observable with the Event Horizon Telescope. In contrast, the De Sitter soliton adopts low energy quantum states with an increasing radius, while the anti-De Sitter soliton adopts high energy quantum states with an increasing radius.

In the semi-classical version of the theory, Einstein’s field equations are modified to the form

This form satisfies Lovelock’s theorem and is formulated in De Sitter space.

The exact solution [

14] in the extreme weak field is

Here

is the value of the Hubble parameter as measured in the ground state of space-time. The metric for the vacuum state

, of the quantized space-time is of the form

The metric equation above describes curved worldlines in flat spacetime. A notable feature of this metric is the absence of singularities. At high energies, characterized by microscopic scale wavelengths of the Nexus graviton and elevated values of , the worldline becomes straight and the local coordinates are highly compact or localized. This characteristic also indicates asymptotic freedom in quantum gravity, as gravity (worldline curvature) diminishes asymptotically at high values of . Consequently, at high energies, graviton-graviton interactions cease due to the lack of curvature. The worldline begins to deviate significantly from a rectilinear trajectory at low energies, where uncertainties in its location are considerable, and the associated graviton wavelengths are at macroscopic scales. In the ground state of spacetime we notice that the metric signature of Eqn. (7) becomes negative and that the worldline is straight.

2.1. A Covariant Canonical Quantization of GR and a Speed of Entanglement

In the full quantum theory, GR is translated into QFT by expressing the metric coefficients in terms of the Bloch energy eigenstate functions as follows:

This means that the metric (geometry of spacetime), a foundational concept in GR, emerges as a composite object built from entangled Dirac spinor fields, rather than being a fundamental entity. The presence of Dirac spinors implies that spin structure (SU(2) symmetry) is built into spacetime at the most basic level. This links the quantum properties of fermions to the topology and connectivity of spacetime, offering a deeper origin for curvature and torsion. Thus geometry is quantum entanglement of spinorial modes.

From Eqn.(8) we can now express the Ricci flow for the vacuum equations as follows (note

)

The term on the right suggests a covariant and a contravariant derivative operating on the metric coefficient such that the Ricci flow when expressed in terms of the Bloch functions becomes

where

The derivative operators on the RHS are entangled, and the coupling/diffusion coefficient, is an areal speed which is the speed of entanglement with a numerical value of approximately 5.2 square parsecs per second.

The Ricci flow in the presence of baryonic matter is expressed as

where

Baryonic matter serves as a heat sink, while the vacuum state of space-time functions as a heat source. As a result, gravitational attraction can be described as a transfer of space-time analogous to the process by which heat moves from a source to a sink. A test particle comprised of baryonic matter (local excitations of Dirac matter fields) moves along with the space-time towards the gravitating mass.

2.2. Quantum Spatio-Temporal Dynamics

We apply Eqn. (12) to understand the behavior of space-time within the deep gravitational potential of a BH. In other words, we seek to find the quantum dynamical behavior of a reference frame in a gravitational field with reference to a stationary reference frame in the absence of gravitational field. To this end we start by reducing Eqn. (12) to the form

in which the metric coefficients are expressed as follows

This expression allows Eqn.(14) to be expressed in the following form after factoring out the Minkowski metric coefficient and multiplying by

.

Here the vacuum potential energy in the

-th quantum state is

where

is the reduced Planck constant and

Here

is the graviton mass implying that the graviton is a virtual particle with a range equal to the Hubble 4-radius. Equation (16) is a four-dimensional Schrödinger equation. In the absence of baryonic matter, it is analogous to the wave equation for the propagation of electromagnetic waves in a conducting medium. This analogy suggests that gravity is attenuated by the conductance of space-time, with increased attenuation at higher frequencies and energies. Additionally, Equation (17) establishes connections between macroscopic and microscopic scales, as well as between classical and quantum domains. The D'Alembertian of Equation (16) is expressed in spherical coordinates as follows:

We then apply the method of separation of variables to solve Eqn.(16) in spherical coordinates by first expressing the function

as follows

Under steady state conditions in which

and

, this methods yields the following

where

and

are constants arising from the separation of variables.

The solutions to the angular equations within the spherically symmetric confinement system are

and

where

is restricted to the range

and the associated Legendre function is

. Here

is the

Legendre polynomial. The product of

and

is the spherical harmonic

where

for

and

for

. The spherical harmonic is orthonormal

The equation for

can be further simplified by substituting

in Eqn.(22) yielding

This equation describes a bound quantum of space-time or a local coordinate system in an energy state inside a potential and experiencing a “centrifugal potential” .

2.3. Stasis and time evolution

We briefly discuss time evolution on a black hole like surface

. On such an orbit, the kinetic energy of the system and the potential energy are in equilibrium. This yields a total energy

simplifying Eqn.(27) to the form

This generates a static state characterized by the absence of temporal evolution and baryonic matter remains in stasis. The absence of time in quantum gravity has been highlighted as one of the most difficult problems in the field [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In the NP the problem of time is resolved by introducing some instability at

which generates a lifetime

at the BH like surface determined by the uncertainty principle

before the system transitions to the next low energy BH like surface. The uncertainty in energy yields an uncertainty in

such that the surface acquires a thickness arising from

. When

, the BH like surface has its closest approach to a contiguous BH like surface of lower energy located at

. This allows baryonic matter to quantum tunnel from one BH like surface to the contiguous surface of lower vacuum energy state. It is now clear that metric of Eqn.(7) is describing the space-time within the thickness of a BH like surface characterized by the quantum number

. This is a semi-classical Schwarzschild like space-time and can be alternatively expressed as.

At high energies, the Schwarzschild space is flat and the lifetime and range within a BH like surface is short.

The quantized space is described by a series of concentric BH like surfaces or AdS Ricci solitons of radius on which no time evolution occurs as described by Eqn.(28).

Having gained insights on stasis and time evolution, we can now further simplify Eqn.(28) by making the following additional substitutions

Since

on a BH like surface then (30) reduces to

The above expression implies

where

The substitutions reduce Eqn.(28) to the form

Thus as the constant term in brackets dominates or , which satisfies the solution . The second term is irregular as implying which implies as.

Similarly, in the reverse scenario, as the centrifugal potential term dominates which leads to . This condition leads to a solution . Since the second term is irregular as therefore this implies as .

2.4. Hydrogen like solutions

We aim to find a solution that meets both asymptotic behaviors. We consider the ansatz

. A solution of this form has been solved for the simple hydrogen atom. Taking hints from Eqn.(33) and Eqn.(34), we propose that the solution to the radial equation of the quantum gravity system

is identical to the radial equation for the hydrogen atom. We test this proposition by comparing the expression in the quantized space for the BH like surfaces

with that obtained from a radial function identical to that of the hydrogen atom. In this case, the radial probability distribution function is

where

and will peak at a value of

determined by

That is at

. This solution implies that

for the quantum gravity system characterized by an AdS Ricci soliton. Thus

is of the form

where

and

is the

Laguerre polynomial. Therefore the steady state quantum gravity system can be written as

where

In synthesis, the function

describes the quantum dynamical behavior of a local coordinate system

in a gravitational potential with reference to a stationary coordinates system

in flat space-time. From a quantum gravity perspective, the value of

is not definite but uncertain relative to a stationary reference frame. The most probable value being

as computed in Eqn.(36). The expectation value

is calculated from

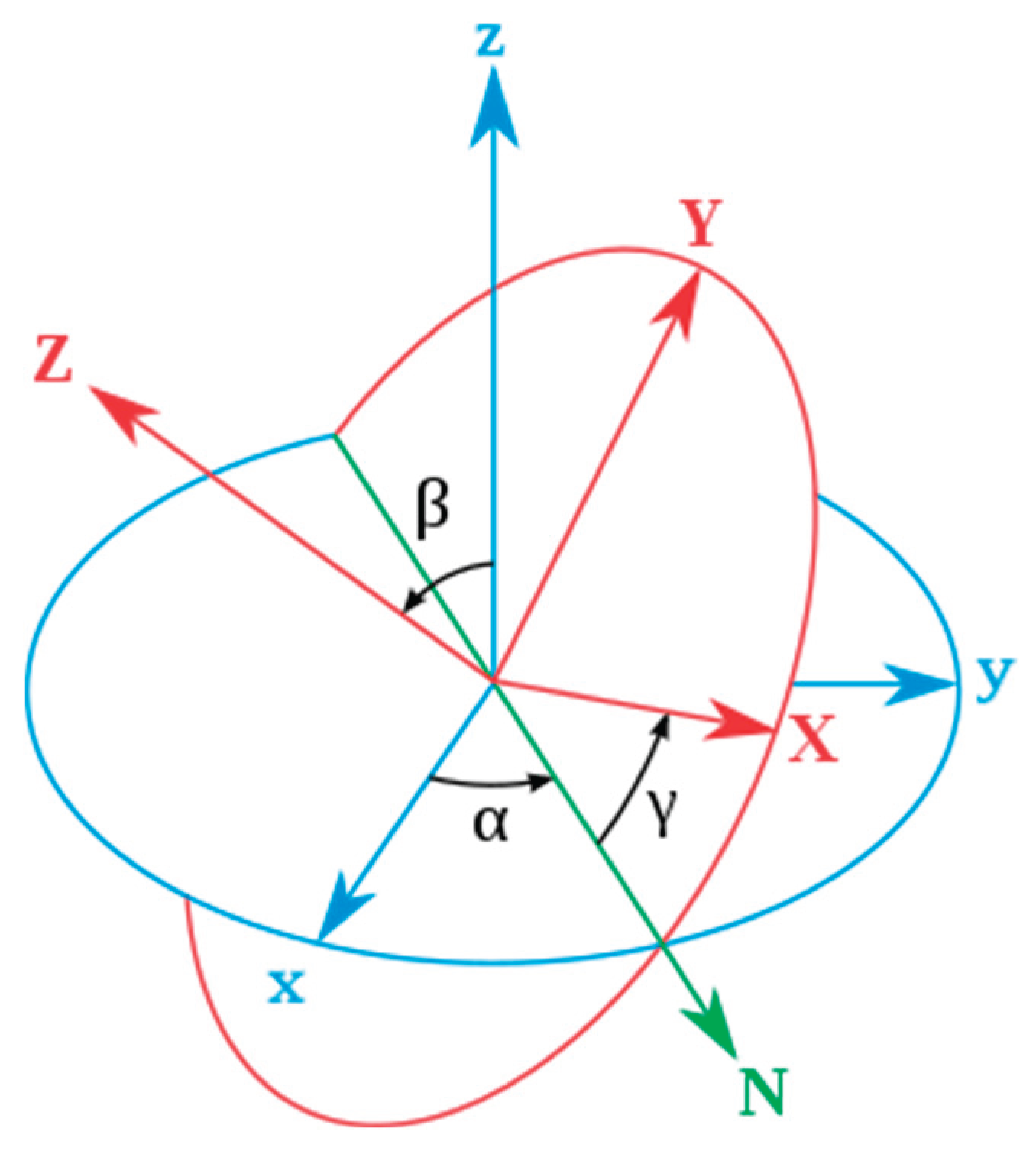

The function

, describes the precession of

with reference to

with an uncertainty in the angle of nutation (See

Figure 1). This results in a fuzzy reference frame with uncertain Lorentz boosts, where only the expectation and most probable values can be calculated. It is also noted that for large distances or high energies, the wave function rapidly diminishes, indicating no discernible spatio-temporal dynamical behavior at high energies and large distances. This wobbling reference frame results in hollow conical or helicoidal astrophysical jets emerging from BHs. However, for De Sitter type Ricci solitons, the spatio-temporal dynamical behavior should be observable at large radii and low energies. Undulations in the trajectories of stars at the edges of galaxies and the enigmatic galactic planes of satellites could serve as potential indicators.

3. Nexus Paradigm Predictions of the BH environment

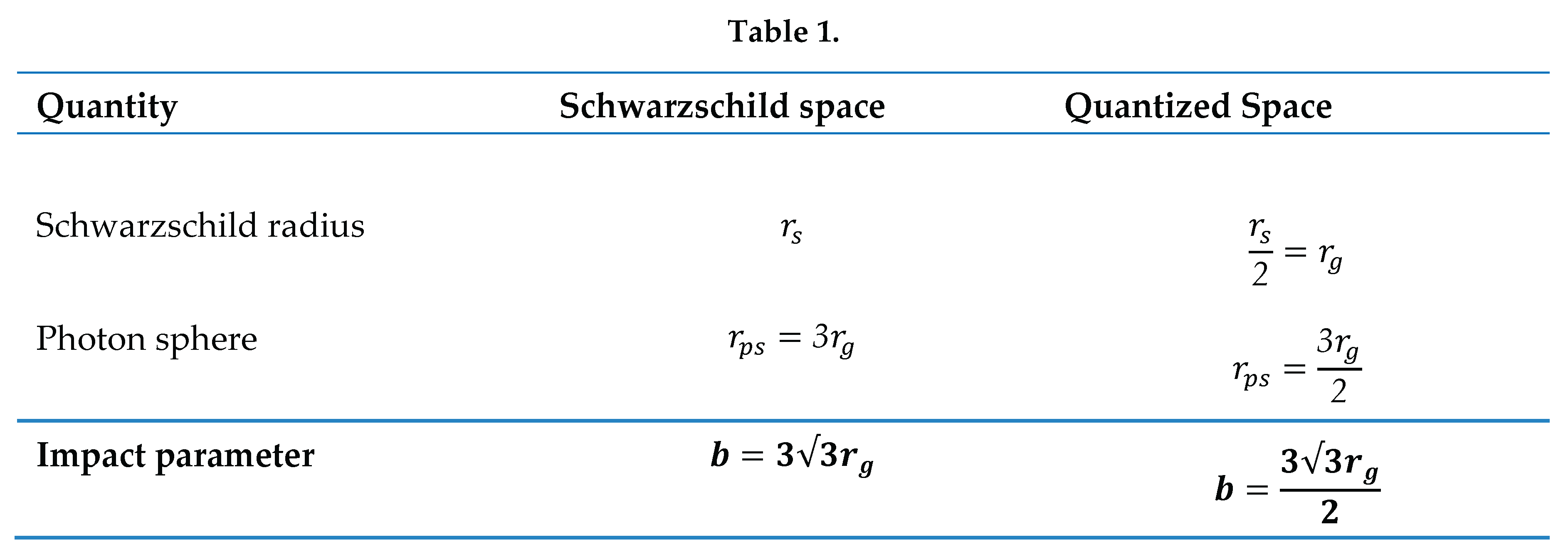

Having derived the equations governing the quantum dynamical behavior of a reference frame in a gravitational potential, we aim to predict the expected observations at horizon scales. It is essential to emphasize the key distinction between a black hole in Schwarzschild space and one in quantized space. A BH in quantized space will behave as a BH in Schwarzschild space but with half the mass. Table 1 shows how this aspect changes some important quantities associated with BHs.

It is interesting to note that the photon sphere in quantized space is the expectation value of the ISCO of

in quantized space. That is

The innermost marginally bound orbital is computed from which for n=2 yields .The expectation value for the orbital is computed as . The same value is obtained in GR through geometric computations, however in quantum gravity there are two sets of values. The other involves the p orbital ( which yields . Thus, in quantum gravity the innermost stable circular orbit can be closer than for a Schwarzschild black hole in GR.

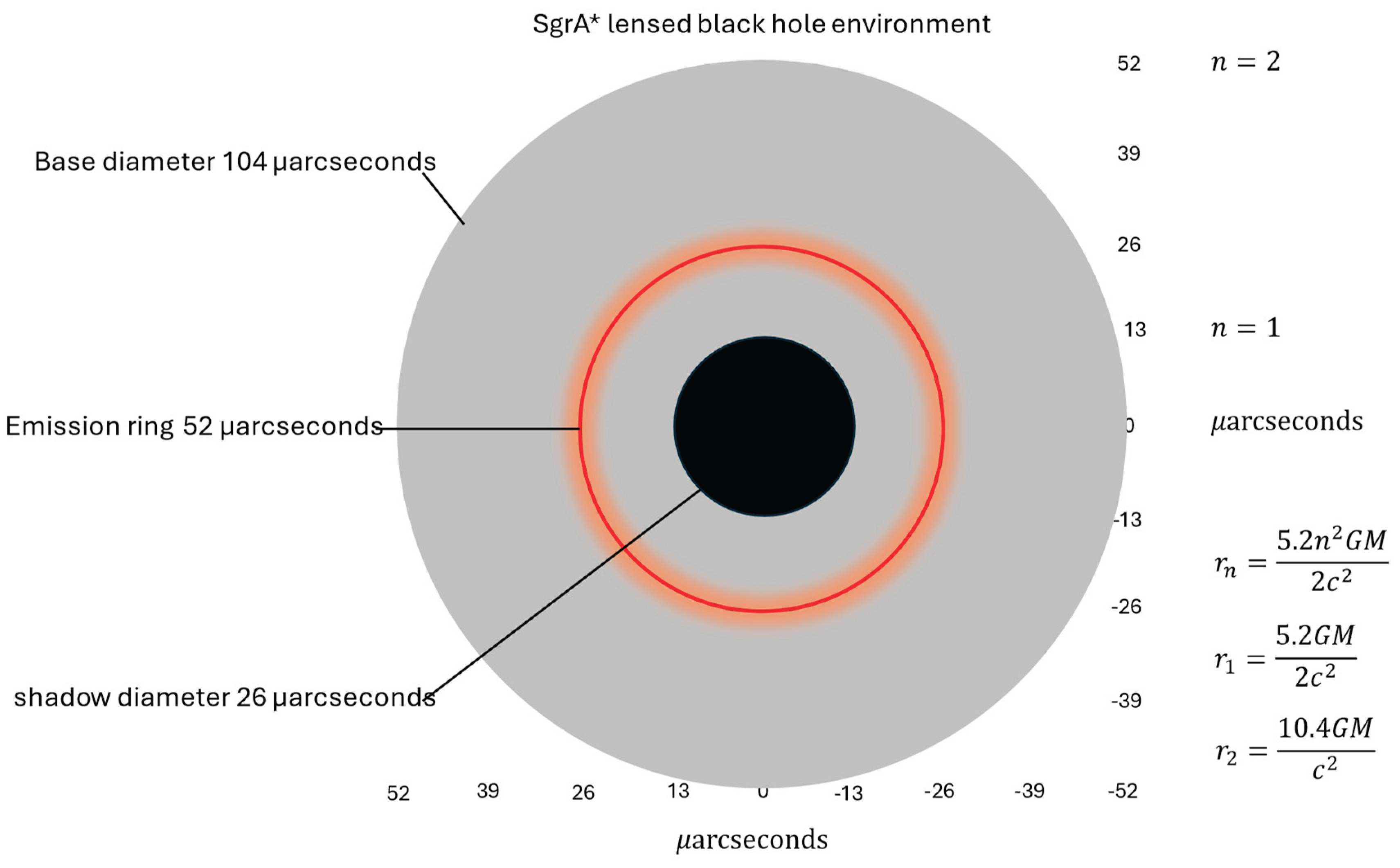

3.1. Ray tracing

The ray tracing in quantized space follows the same procedure as in the Schwarzschild space as computed in the literature [

30,

31] but having half the value of the impact parameter. Since the rays emanate from the event horizon, the rays follow a path that magnifies the image of the BH by a factor of

such that the gravitationally lensed values for the orbits

and

will show as depicted in

Figure 2. A dark central depression of angular diameter

is to be expected. Thus for SgrA* we expect a value for the dark depression of

and for M87* a value of

.

4. Data and Mode

4.1. EHT Observations

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) observations in 2017, and prior observations from 2013, provided groundbreaking horizon-scale images of supermassive black holes (SMBHs), focusing on Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) and M87*. Early EHT campaigns, including 2013, targeted Sgr A* using a smaller VLBI network at 1.3 mm wavelength [

11,

32]. The 2013 observations

detected a compact source with an angular size of ~25 ± 2

as for the central dark depression, an emission ring of ~52 ± 2

as and a base diameter of ~104

as [

11,

32]. The significance of the 2013 observations resides in that they

provided initial evidence of a BH shadow, though limited by sparse baseline coverage and lower resolution. These observations were confirmed by Cho et al. [

32]. The 2013 campaign faced limitations due to long-exposure-like data lacking dynamic details, and the imaging of M87* being less advanced.

The 2017 campaign expanded the EHT array to eight telescopes which included telescopes such as ALMA and SMA for improved resolution and sensitivity at 1.3 mm [

2,

32]. For Sgr A* the 2017 campaign, the EHT measured a dark depression of 26 ± 2

as compared to 25 ± 2

as in 2013. For the emission ring, the EHT measured 51.8 ± 2.6

as (2017) compared to 52 ± 2

as in 2013 and a base diameter of 104

as (±3

as). The 2019 campaign measured for M87* a dark depression of 20 μas (±2

as), an emission ring of 40

as (±3

as) and a base diameter 80

as (±3

as).

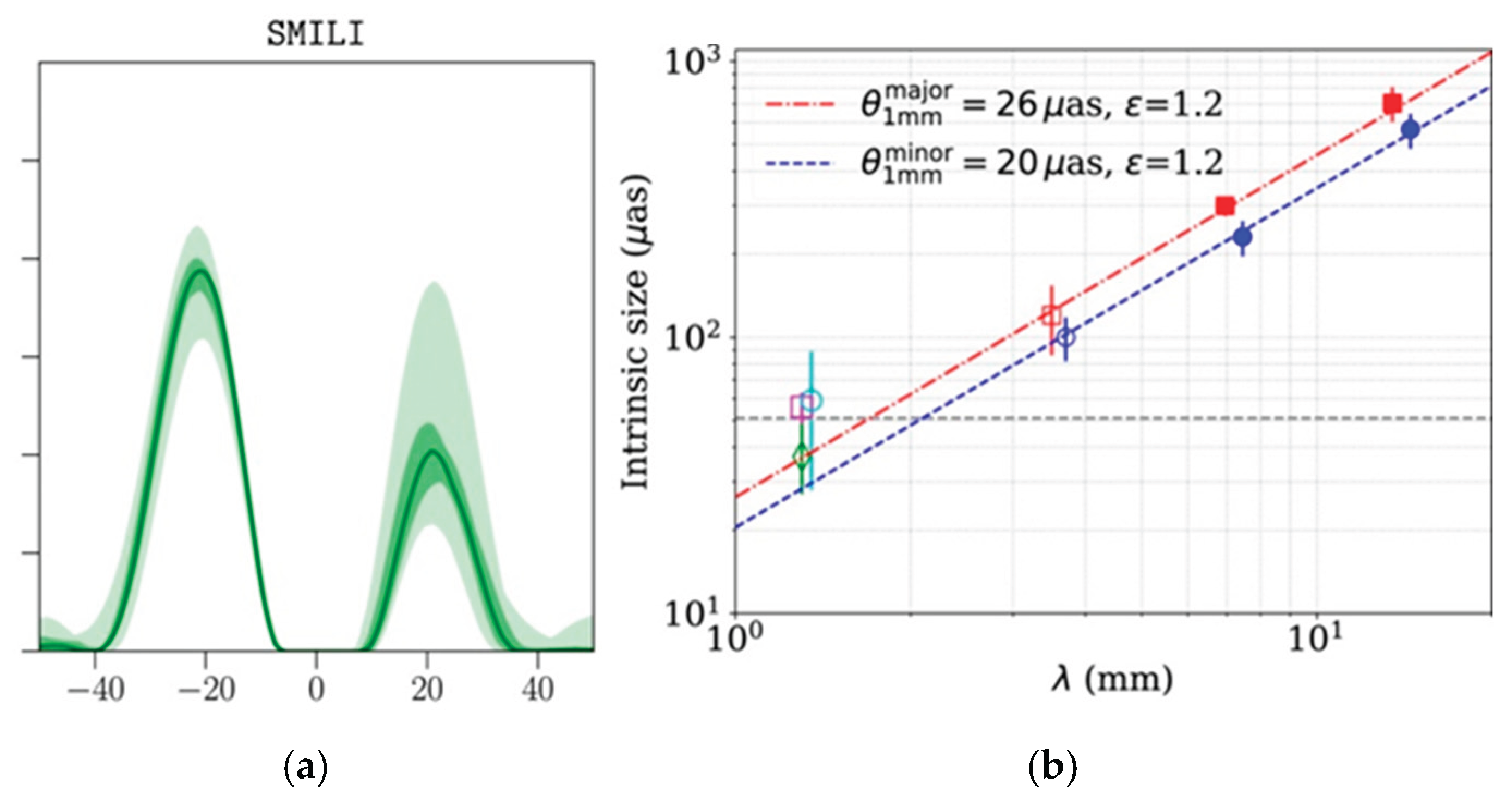

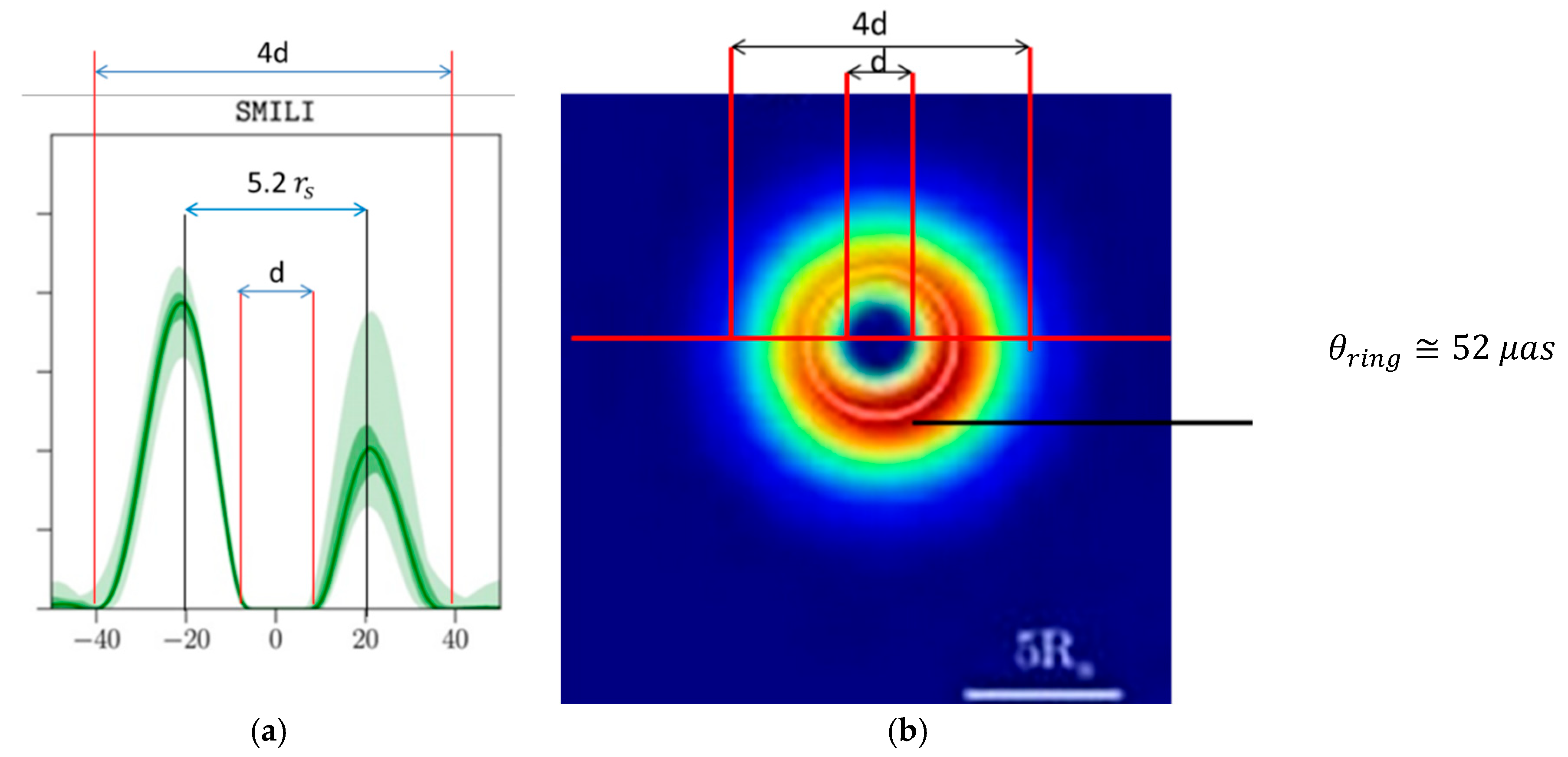

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b shows the luminosity profile of M87* and the dark depression measurements of SgrA*.

4.2. EHT Imaging uncertainties

The observational uncertainties in the EHT 2017 (M87*) and 2019 (Sgr A*) images stem from calibration errors (gain, polarization leakage, atmospheric phase), sparse baseline coverage, algorithmic reconstruction choices, source variability (especially for Sgr A*), and astrophysical model assumptions (accretion, spin, inclination). While M87* benefited from stability and a larger angular size, Sgr A* faced challenges from rapid variability and Galactic Center interference. Ongoing improvements in telescope array size, bandwidth, and algorithms aim to reduce these uncertainties in future observations. The EHT employs 5 imaging software ,which are DIFMAP, EHT imaging, SIMILI, THEMIS and Comrade. The first 3 favour an emission ring of

and later 2 favour

for the 2017 campaign. We choose the size from the first three imaging software, as they are consistent with

Figure 1a compared to the last two.

4.3. Nexus Paradigm Predictions

The NP predicts angular diameters based on the gravitational radius angular scale,

, where (M) is the BH mass, (D) is the distance. The angular size of the dark depression is predicted as

in the NP. The emission ring is predicted as having an angular dimension of

and the base diameter an angular diameter of

. Thus for Sgr A*(

as based on

,

kpc [

33] ) the NP predictions for the dark depression is

as, for the emission ring

as and for the base diameter

as. For M87*(

as based on

,

Mpc [

34]) the dark depression is

as, for the emission ring

as and for the base diameter

as. In contrast to classical General Relativity, the NP predicts that horizon scale images of black holes will appear blurry even if the EHT had infinite resolution capabilities due to significant uncertainties in location (delocalization) within regions of strong gravity [

13,

14]. Within the framework of the NP,the ring feature dominating BH images arises from baryonic matter quantum tunneling into the

orbital from the

orbital accompanied by radiation emission. The tunneling process peaks at a radius

,(where

) which for the

orbital is

. A gravitational lensing of the associated ring yields an angular diameter of

for Sgr A*and

for M87*. Here

is the angular measurement of

which is equivalent to

.

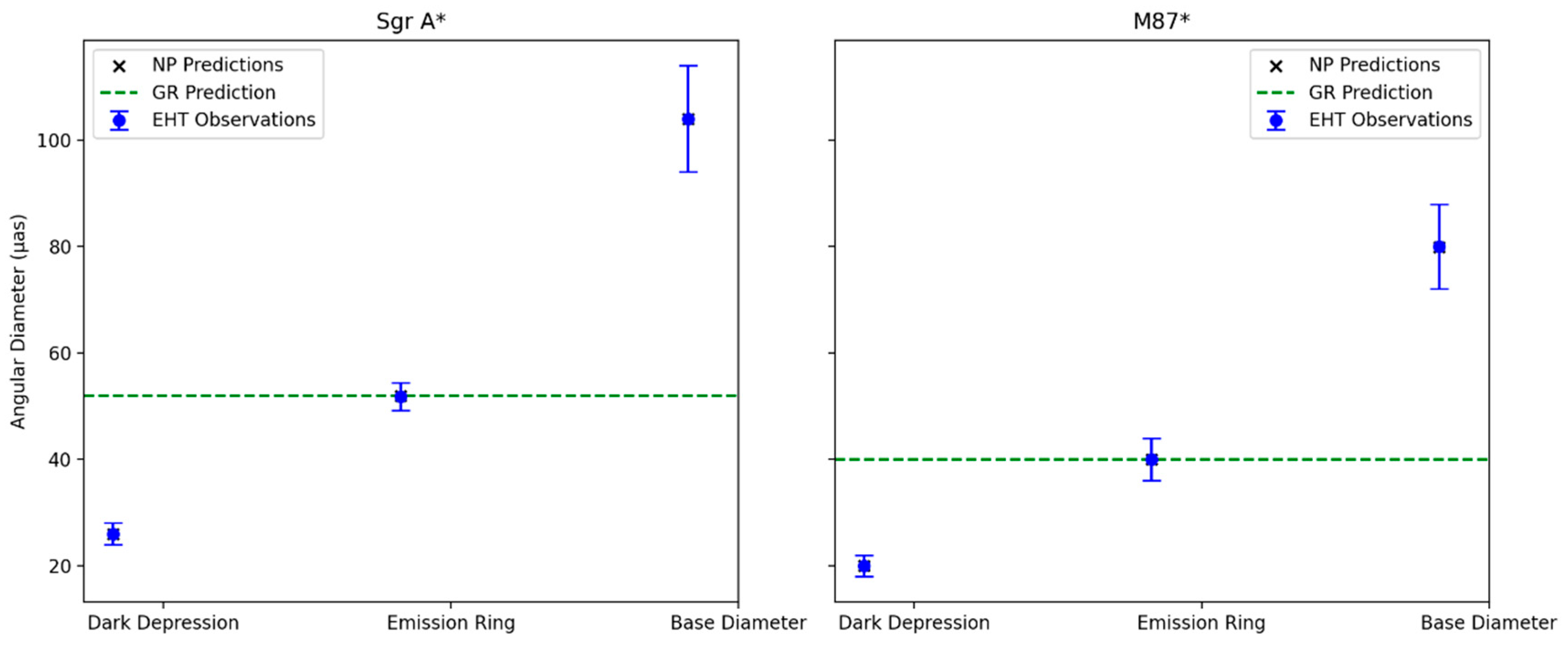

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b show the predicted base diameter, emission ring and dark depression for M87* and SgrA* by the NP.

4.4. GR predictions

GR predicts a BH shadow diameter of

as for SgrA*,

as for M87* which aligns with the emission ring but not the dark depression [

35]. In the EHT image of M87 of 2019 or Sgr A* of 2022, the bright ring-like structure is mostly the emission ring from the accretion disk, with its brightness enhanced by gravitational lensing and Doppler effects (e.g., brighter on one side due to material moving toward the observer). There is no single, exact formula for the emission ring’s size in GR because it depends on the accretion disk’s physical properties, unlike the photon ring or shadow, which have well-defined sizes based on the black hole’s mass and distance. The emission ring’s angular size is approximately

where

, but its breadth and exact size require numerical modeling of the accretion flow. In the EHT images, the emission ring appears as a broader, brighter feature than the photon ring, typically comparable to or slightly larger than the shadow’s angular size. For comparison to the EHT observations, some images are cherry picked from tens of thousands of simulated GRMHD images to find the best fit. In contrast, the emission ring diameter in the NP has an exact formula of

as for SgrA*,

as for M87* and the shadow size is 3

and no simulations are required beyond

Figure 2. Also, the NP reveals BH features that classical GR cannot predict such as the base diameter. The important features that are used to test GR are the photon ring and the shadow diameter. The EHT images do not show the photon ring only a dark depression which is assumed to be the shadow. The dark depression, which has maintained its angular size in all the EHT imaging throughout the years, is the only feature we can use to test GR.

5. Bayesian Methodology

We employ a Bayesian framework to compare NP predictions with EHT observations, computing the posterior distribution for and assessing model consistency.

5.1. Likelihood

The likelihood for each feature (i) (dark depression, emission ring, base diameter) is:

where

is the observed angular diameter,

, and

is the observational uncertainty. The combined likelihood is:

5.2. Priors

The prior for is informed by mass and distance measurements. Thus for SgrA* , kpc with the variance being yielding as. Prior as. For M87*, and the variance being yielding as with a prior as.

5.3. Posterior

We maximize the log-likelihood to find the best-fit

and compute the

statistics as

Degrees of freedom (dof) = number of data points minus fitted parameters. We also compute 99% credible intervals for

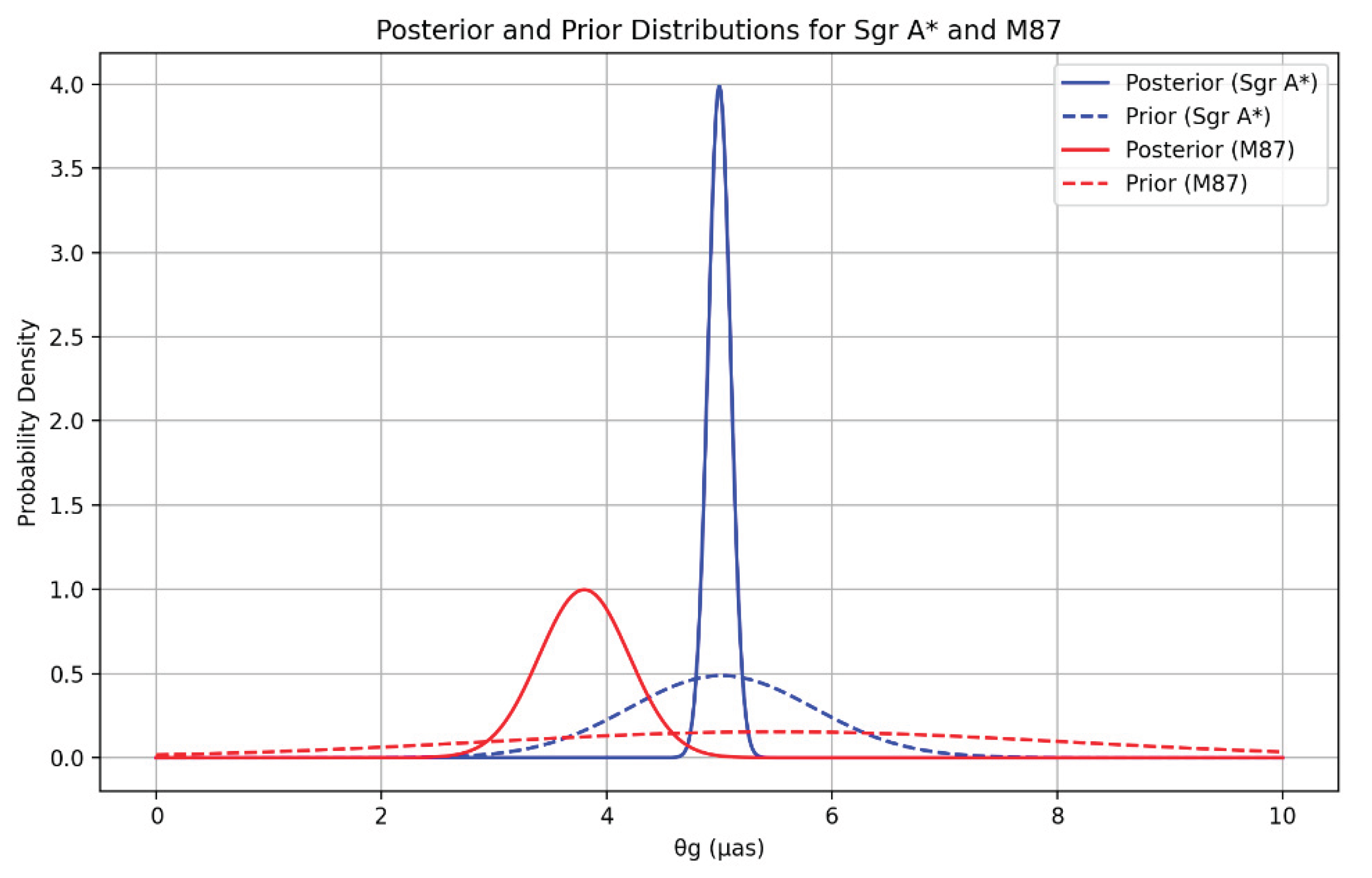

. The posterior and prior distributions for SgrA* and M87* are displayed in

Figure 5

5.4. Model Comparison

We compare NP to GR using the Bayes factor:

6. Results

For SgrA*, we have EHT 2017 campaign observations for the three angular diameters for the key image features such as dark depression, emission ring and base diameter

as with

as, we find best-fit

as , yielding predictions

as. Thus

With and reduced . This yields a confidence level for , corresponding to 3.04 (99.73% confidence). Thus for the confidence per feature, we have for the dark depression a deviation of as corresponding to a to 0.02 deviation, for the emission ring a deviation of as corresponding to a to 0.06 deviation and finally for the base diameter a deviation of as corresponding to a to 0.008 deviation, Each feature agrees at >99% confidence (<1 ). We compute the posterior for as as. This corresponds to a 99% credible interval of [4.74, 5.26] as, encompassing the prior mean (5.02 as) within .

For M87*, we have for the EHT 2017 campaign observations of the three angular diameters for the key image features

as with

as, we find best-fit

as , yielding predictions

as. Therefore

With

and reduced

. This yields a confidence level for

, corresponding to 2.88

(99.80% confidence). Thus for the confidence per feature, we have for the dark depression a deviation of

as corresponding to a to 0.015

deviation, for the emission ring, a deviation of

as corresponding to a to 0.015

deviation and finally for the base diameter, a deviation of

as corresponding to a to 0.015

deviation, Each feature agrees at >99.9% confidence (<1

). We compute the posterior for

as

as. This corresponds to a 99% credible interval of [3.47, 4.25]

as, within

of the prior mean of 3.85

as. The predictions of each feature by GR and NP are displayed in

Figure 6.

6.1. Combined Fit

The combined fit yields a , dof=4, (6 data points and 2 parameters). This yields a confidence level for , corresponding to 4.37 (99.9972% confidence). The reduced , indicating an excellent fit.

6.2. GR Comparison

For the SgrA* dark depression

as, GR predicts

as. Thus

This deviation yields , corresponding to 12.97 indicating extreme inconsistency. The NP is favoured at.

7. Discussion

The Bayesian analysis confirms the NP’s excellent agreement with EHT observations, with a combined fit at 4.37 (99.9972% confidence), exceeding the 99th percentile (~2.326 ) claimed by Marongwe (2023). Individual features deviate by <0.1σ, supporting the NP’s predictions for the dark depression, emission ring, and base diameter. The posterior θg values align with prior expectations within ~0.2 , reinforcing consistency.

Compared to GR, which mis predicts the dark depression at ~12.97

, the NP’s ability to fit multiple features is a significant advantage. The Bayes factor

strongly favours NP, though GR aligns with the emission ring, suggesting plasma dynamics may complement GR’s shadow prediction [

36].

The NP’s quantized spacetime, with a halved Schwarzschild radius and quantum tunnelling for emission rings, offers a compelling alternative to GR, addressing observed stable orbits below the ISCO [

13]. Its predictions of hollow conical jets, confirmed in M87* and Centaurus A*, further support its astrophysical relevance [

37].

8. Conclusion

Our Bayesian analysis validates the Nexus Paradigm’s predictions for Sgr A* and M87* at a 4.37σ (99.9972%) confidence level, with individual features agreeing at >99% confidence. The NP outperforms GR by >10σ for the dark depression, supporting its potential as a quantum gravity framework. Future work should incorporate precise EHT uncertainties, compare NP with other gravity models, and test additional observables (e.g., polarimetric data). These results underscore the power of EHT observations to probe quantum gravity, paving the way for deeper investigations into spacetime’s fundamental nature.

Funding Statement

We gratefully acknowledge publication funding from the Office of Research and Development of the University of Botswana.

Data availability statement

The data employed in the article is available from the cited articles.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully appreciate the discussions, suggestions and constructive criticism from members of the Physics Department and the Department of Mathematics of the University of Botswana.

Conflict of interest

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L1 (2019).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L2 (2019).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L3 (2019).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L3 (2019).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L5 (2019).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L12 (2022).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L13 (2022).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L14 (2022).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L15 (2022).

- EHT Collaboration, K. Akiyama et al., Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L16 (2022).

- R.-S. Lu et al., Astrophys. J. 859, 60 (2018).

- S. Marongwe, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 32, 2350047 (2023).

- S.Marongwe, Int. J. Geo. Mtd. Mod .Phys.12, 1550042 (2015).

- S.Marongwe, Phys. Scr. 99 025306 (2024).

- L. Rezzolla and A. Zhidenko, Phys. Rev. D. 90, 084009 (2014).

- S.X.Tian and Z-H. Zhu , Phys. Rev. D. 100, 064011 (2019) : arXiv:1908.11794.

- S.Vagnozzi et al., Class. Quantum Grav. 40 165007 (2023).

- M.Khodadi, S.Vagnozzi, and J.T. Firouzjaee, Sci Rep 14, 26932 (2024).

- S. A. Hayward, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 031103(2006)[gr-qc/0506126].

- J. M. Bardeen, in Conference Proceedings of GR5 (Tbilisi,USSR,1968),p.174.

- N.Tsukamoto arXiv:2307.11303.

- J.Dass et al. A&A 673, A53 (2023).

- M.Khodadi, and E.N. Saridakis,. Physics of the Dark Universe, 32, 100835. (2020).

- C. Kiefer, Quantum Gravity (Clarendon, Oxford 2004).

- C. Rovelli, Quantum Gravity (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004).

- E. Anderson arXiv:1009.2157 [gr-qc].

- J.A. Wheeler, in Battelle Rencontres (Benjamin, New York 1968).

- K.V. Kuchař, in The Arguments of Time ed. J. Butterfield (Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999).

- L. Smolin, Problem of Time Course (2008).

- V.Bozza, S.Capozziello, et al, Relativ. Gravit. 2001, 33, 1535–1548.

- K.S.Virbhadra, Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 083004.

- Cho et al., Astrophys. J. 926, 108 (2022).

- M.Ghez et al., Astrophys. J. 689, 1044 (2008).

- K. Gebhardt et al., Astrophys. J. 729, 119 (2011).

- S. E. Gralla et al., Phys. Rev. D 101, 044031 (2020).

- D. Psaltis, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 51, 137 (2019).

- M. Janssen et al., Nat. Astron. 5, 1017 (2021).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).