Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

The NutriShed Study

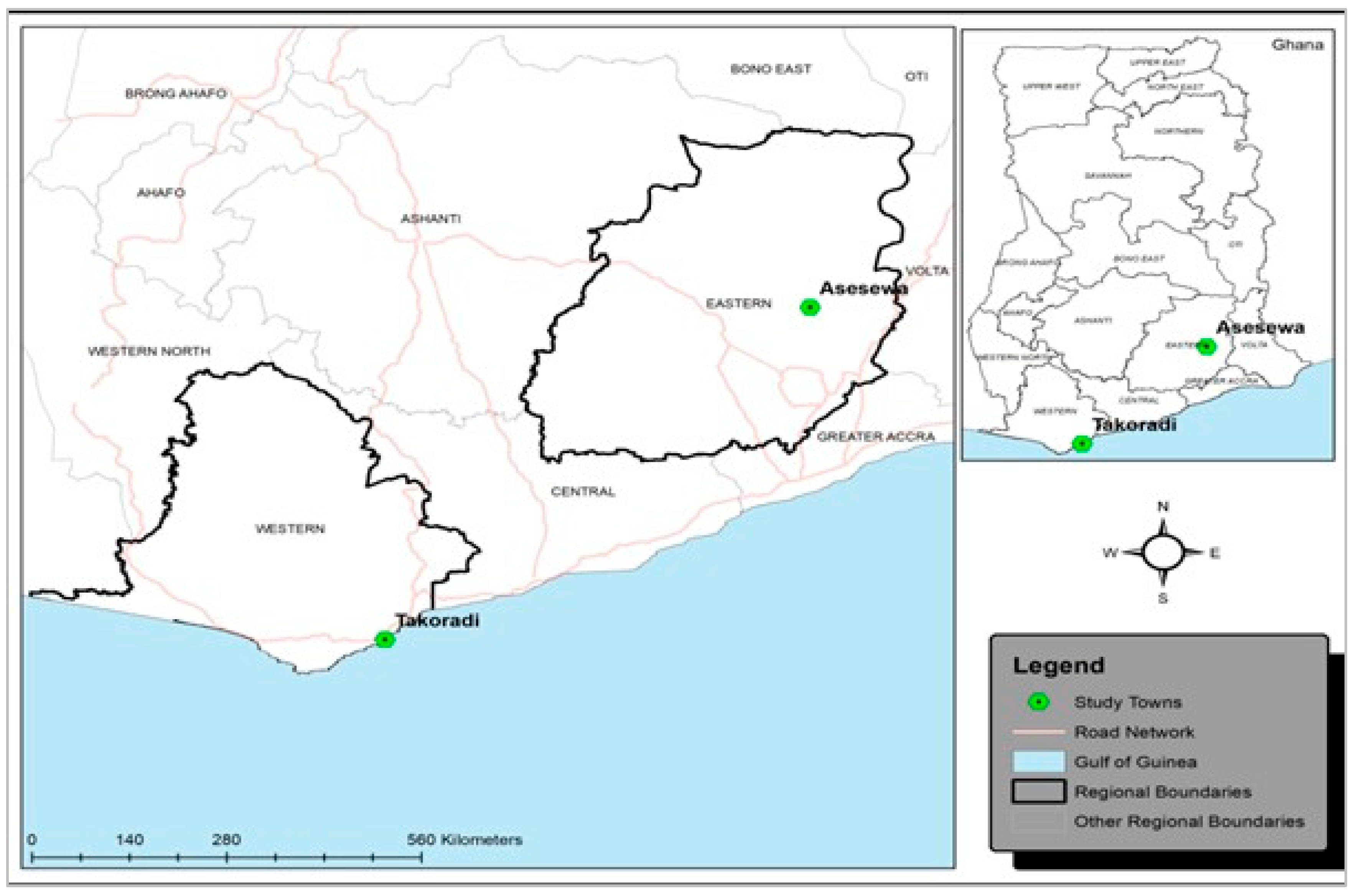

Study Settings

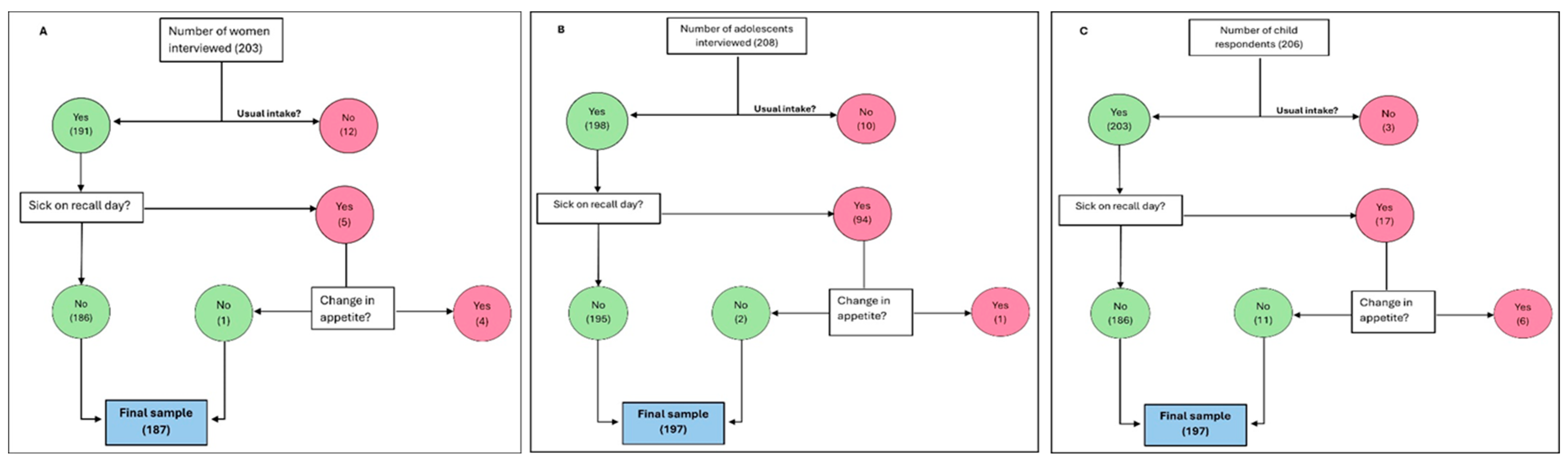

Study Participants & Sampling Procedure

Sampling Approach

Consent for participation

Data Collection

Data Analysis

Characteristics of the Study Sample

Nutrient Gap Analysis

Discussion

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Rodríguez-Mañas L, Murray R, Glencorse C, et al. (2023) Good nutrition across the lifespan is foundational for healthy aging and sustainable development. Front. Nutr. 9, 1–12.

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Schroeder DG, et al. (1995) The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 73, 443–448.

- Pelletier DL & Frongillo EA (2003) Changes in child survival are strongly associated with changes in malnutrition in developing countries. J. Nutr. 133, 107–119. American Society for Nutrition.

- World Health Organisation (2024) Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed November 2024).

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382, 427–451.

- Stevens GA, Beal T, Mbuya MNN, et al. (2022) Micronutrient deficiencies among preschool-aged children and women of reproductive age worldwide: a pooled analysis of individual-level data from population-representative surveys. Lancet Glob. Heal. 10, e1590–e1599.

- Ahmed F, Prendiville N & Narayan A (2016) Micronutrient deficiencies among children and women in Bangladesh: progress and challenges. J. Nutr. Sci. 5, e46. England.

- Ayal BG, Demilew YM, Derseh HA, et al. (2022) Micronutrient intake and associated factors among school adolescent girls in Meshenti Town, Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS One 17, 1–18. Public Library of Science.

- Greffeuille V, Dass M, Fanou-Fogny N, et al. (2023) Micronutrient intake of children in Ghana and Benin: Estimated contribution of diet and nutrition programs. Matern. \& Child Nutr. 19, e13453.

- Wegmüller R, Bentil H, Wirth JP, et al. (2020) Anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, malaria, hemoglobinopathies and malnutrition in young children and non-pregnant women in Ghana: Findings from a national survey. PLoS One 15, 1–19.

- Prentice AM, Ward KA, Goldberg GR, et al. (2013) Critical windows for nutritional interventions against stunting. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 911–918. American Society for Nutrition.

- Benoist B de, McLean E, Iegli N, et al. (2008) Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005 : WHO global database on anaemia. World Health Organization.

- Molani Gol R, Kheirouri S & Alizadeh M (2022) Association of Dietary Diversity With Growth Outcomes in Infants and Children Aged Under 5 Years: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 54, 65–83. United States.

- Rah JH, Akhter N, Semba RD, et al. (2010) Low dietary diversity is a predictor of child stunting in rural Bangladesh. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 1393–1398.

- Modjadji P, Molokwane D & Ukegbu PO (2020) Dietary diversity and nutritional status of preschool children in north west province, south africa: A cross sectional study. Children 7, 1–14.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, et al. (2020) The State Of Food Security And Nutrition In The World 2020. Transforming Food Systems For Affordable Healthy Diets. State Food Secur. Nutr. World 2020.

- Akparibo R, Aryeetey R, Cooper G, et al. (2025) NutriShed: A Novel Methodological Framework for Nutrition Security Planning in Urban Communities. Preprints.

- Ghana Statistical Service (2021) Ghana 2021 POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS GENERAL REPORT VOLUME 3A.

- Gibson RS & Ferguson EL (2008) Calculating intakes of nutrients and antinutrients. An Interact. 24-hour recall Assess. adequacy iron zinc intakes Dev. Ctries.

- of Medicine I (2006) Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. [Otten JJ, Hellwig JP, Meyers LD, editors]. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand Including Recommended Dietary Intakes | NHMRC. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nutrient-reference-values-australia-and-new-zealand-including-recommended-dietary-intakes (accessed July 2025).

- Akwaa Harrison O, Ifie I, Nkwonta C, et al. (2024) Knowledge, awareness, and use of folic acid among women of childbearing age living in a peri-urban community in Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 1–8.

- Apprey C, Addae HY, Boateng G, et al. (2025) Dietary diversity and nutrient adequacy among women in Bosomtwe District, Ghana. Matern. Child Nutr. 21, e13757. England.

- Puwanant M, Boonrusmee S, Jaruratanasirikul S, et al. (2022) Dietary diversity and micronutrient adequacy among women of reproductive age: a cross-sectional study in Southern Thailand. BMC Nutr. 8, 1–11. BioMed Central.

- Luthringer CL, Rowe LA, Vossenaar M, et al. (2015) Regulatory Monitoring of Fortified Foods: Identifying Barriers and Good Practices. Glob. Heal. Sci. Pract. 3, 446–461. United States.

- Das JK, Salam RA, Thornburg KL, et al. (2017) Nutrition in adolescents: physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1393, 21–33.

- Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, et al. (2016) The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos. Int. a J. Establ. as result Coop. between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 27, 1281–1386. England.

- World Health Organisation (2023) Micronutrients. https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients#tab=tab_1 (accessed June 2025).

- Cunha C de M, Costa PRF, de Oliveira LPM, et al. (2018) Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic risk factors among adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 119, 859–879. England.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Total Sample | Asesewa | Takoradi |

| A. Women (n) | 187 | 95 | 92 |

| Age in years (Grouped)* | |||

| 18 - 49 | 88.77 | 91.58 | 85.87 |

| 49 + | 10.70 | 7.37 | 14.13 |

| Level of education | |||

| No formal education | 6.42 | 3.16 | 9.78 |

| Primary/Junior High§ | 50.27 | 56.84 | 43.48 |

| Secondary | 31.55 | 25.26 | 38.04 |

| Tertiary | 11.76 | 14.74 | 8.70 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 35.83 | 32.63 | 39.13 |

| Married/Living together | 55.61 | 55.79 | 55.43 |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 8.56 | 11.58 | 5.43 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 68.98 | 54.74 | 83.70 |

| Unemployed | 31.02 | 45.26 | 16.30 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Pentecostal | 39.04 | 51.58 | 26.09 |

| Charismatic | 27.27 | 17.89 | 36.96 |

| Orthodox/Protestant | 30.48 | 29.47 | 31.52 |

| Muslim | 3.21 | 1.05 | 5.43 |

| B. Adolescents (n) | 197 | 99 | 98 |

| Age group | |||

| 10 - 14 | 62.94 | 68.69 | 57.14 |

| 15 - 19 | 37.06 | 31.31 | 42.86 |

| Highest level of education | |||

| No formal education | 2.54 | 3.03 | 2.04 |

| Incomplete primary | 29.95 | 38.38 | 21.43 |

| Completed primary | 23.35 | 37.37 | 9.18 |

| Incomplete junior high school | 12.18 | 2.02 | 22.45 |

| Complete junior high school | 19.80 | 18.18 | 21.43 |

| Incomplete senior high | 12.18 | 1.01 | 23.47 |

| Type of school** | |||

| Public | 88.54 | 85.42 | 91.67 |

| Private | 11.46 | 14.58 | 8.33 |

| Fed at school** | |||

| Yes | 28.13 | 18.75 | 37.50 |

| No | 71.88 | 81.25 | 62.50 |

| Currently employed | |||

| Yes | 2.54 | 2.02 | 3.06 |

| No | 97.46 | 97.98 | 96.94 |

| Main source of income | |||

| Monthly salary | 21.32 | 14.14 | 28.57 |

| Self-employed | 76.14 | 81.82 | 70.41 |

| Pensions | 1.52 | 3.03 | - |

| Other | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 |

| C. Young Children (2 - 5 years) (n) | 197 | 100 | 97 |

| Age in years | |||

| 2 | 23.86 | 24.00 | 23.71 |

| 3 | 29.95 | 33.00 | 26.80 |

| 4 | 24.87 | 26.00 | 23.71 |

| 5 | 21.32 | 17.00 | 25.77 |

| Ever attended school | |||

| Yes | 81.22 | 79.00 | 83.51 |

| No | 18.78 | 21.00 | 16.49 |

| Type of school | |||

| Public | 34.38 | 26.58 | 41.98 |

| Private | 65.63 | 73.42 | 58.02 |

| Fed at school*** | |||

| Yes | 90.63 | 84.81 | 96.30 |

| No | 9.38 | 15.19 | 3.70 |

| Who feeds the child at school? | |||

| Child | 28.43 | 10.00 | 47.42 |

| Teacher | 40.10 | 47.00 | 32.99 |

| School cook | 4.57 | 9.00 | - |

| Older sibling | 0.51 | 1.00 | - |

| Don’t know | 26.40 | 33.00 | 19.59 |

| Type of Nutrient | Reference EAR/day | Total Sample (n = 187) | Asesewa (n = 95) | Takoradi (n = 92) | |||

| Median intake | Inadequate intake (%) | Median intake | Inadequate intake (%) | Median intake | Inadequate intake (%) | ||

| Macronutrients | |||||||

| Energy (kcals) | 2200 | 2337.2 | 42.7 | 2240.2 | 47.37 | 2517.1 | 38.04 |

| Protein (g) | 37 | 70.0 | 15.0 | 68.7 | 15.8 | 74.7 | 14.1 |

| Fat* (mg) | 90 | 78.6 | 55.1 | 73.9 | 61.1 | 91.5 | 48.9 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 100 | 267.2 | 6.4 | 270.6 | 8.4 | 258.2 | 4.4 |

| Fibre (g) | 25 | 36.8 | 24.6 | 37.7 | 23.2 | 35.2 | 26.1 |

| Micronutrients | |||||||

| Calcium (mg) | 840 | 570.3 | 72.7 | 552.1 | 72.6 | 579.2 | 72.8 |

| Iron (mg) | 8 | 18.7 | 6.4 | 18.4 | 7.4 | 18.9 | 5.4 |

| Folic acid (µg) | 320 | 257.2 | 59.4 | 240.3 | 64.2 | 291.8 | 54.4 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | 11 | 23.1 | 15.0 | 22.7 | 12.6 | 23.6 | 17.4 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 0.9 | 0.8 | 63.6 | 0.7 | 72.6 | 0.8 | 54.4 |

| Thiamine (B1) (mg) | 0.9 | 1.2 | 29.4 | 1.1 | 29.5 | 1.2 | 29.4 |

| Pyridoxine (B6) (mg) | 1.1 | 2.3 | 13.4 | 2.4 | 13.7 | 2.2 | 13.0 |

| Cobalamin (B12) (ug) | 2.0 | 3.6 | 25.1 | 3.8 | 27.4 | 3.6 | 22.8 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 30 | 121.8 | 4.3 | 131.8 | 5.3 | 113.0 | 3.3 |

| Zinc (mg) | 6.5 | 9.0 | 29.4 | 8.2 | 27.4 | 9.7 | 31.5 |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 500 | 797.9 | 28.3 | 770.0 | 31.6 | 817.5 | 25.0 |

| Nutrients/Age | Males | Females | ||||||

| Reference EAR | Median Intake | Reference EAR | Median Intake | |||||

| Total | Asesewa | Takoradi | Total | Asesewa | Takoradi | |||

| Macronutrients | ||||||||

| Energy (kcals) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 1053 | 1492.0 | 1256.6 | 2078.8 | 1005 | 1451.7 | 1375.6 | 1779.5 |

| 3 years | 813 | 1724.1 | 1607.4 | 2494.2 | 766 | 1780.9 | 1010.0 | 3147.2 |

| 4 years | 861 | 1915.8 | 1619.2 | 3563.1 | 813 | 1666.5 | 1333.7 | 1845.6 |

| 5 years | 909 | 2242.9 | 2001.0 | 2436.4 | 861 | 2145.5 | 2125.8 | 2165.2 |

| Protein (g) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 12 | 37.8 | 37.8 | 36.7 | 12 | 44.6 | 31.0 | 45.5 |

| 3 years | 12 | 47.3 | 45.2 | 51.0 | 12 | 44.7 | 27.9 | 82.9 |

| 4 years | 16 | 44.3 | 39.3 | 65.3 | 16 | 48.6 | 45.3 | 51.8 |

| 5 years | 16 | 44.7 | 38.8 | 55.9 | 16 | 49.4 | 57.2 | 43.9 |

| Fat (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 40 | 52.4 | 35.9 | 105.7 | 40 | 61.5 | 58.0 | 63.1 |

| 3 years | 40 | 60.0 | 53.4 | 109.3 | 40 | 73.5 | 17.3 | 168.5 |

| 4 years | 55 | 77.7 | 59.3 | 189.5 | 55 | 59.5 | 37.6 | 74.7 |

| 5 years | 55 | 58.6 | 53.2 | 94.2 | 55 | 88.8 | 87.0 | 90.9 |

| Fibre (g) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 14 | 20.3 | 22.3 | 19.6 | 14 | 24.8 | 24.0 | 25.3 |

| 3 years | 14 | 25.4 | 25.2 | 26.0 | 14 | 23.6 | 19.0 | 33.9 |

| 4 years | 18 | 28.0 | 25.0 | 34.2 | 18 | 22.5 | 13.5 | 22.7 |

| 5 years | 18 | 26.8 | 21.6 | 26.8 | 18 | 25.5 | 36.2 | 21.5 |

| Micronutrients | ||||||||

| Calcium (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 360 | 379.7 | 417.3 | 357.8 | 360 | 457.1 | 367.8 | 504.4 |

| 3 years | 360 | 470.1 | 456.9 | 535.3 | 360 | 559.6 | 357.4 | 646.2 |

| 4 years | 520 | 530.9 | 441.3 | 633.1 | 520 | 406.6 | 356.9 | 475.6 |

| 5 years | 520 | 507.2 | 486.1 | 507.2 | 520 | 542.6 | 838.4 | 361.9 |

| Iron (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 4 | 10.9 | 12.1 | 9.6 | 4 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 16.4 |

| 3 years | 4 | 14.0 | 12.9 | 16.1 | 4 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 19.4 |

| 4 years | 4 | 14.5 | 11.0 | 16.4 | 4 | 13.7 | 12.7 | 14.7 |

| 5 years | 4 | 13.0 | 10.5 | 15.1 | 4 | 13.2 | 19.1 | 12.3 |

| Folic acid (μg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 120 | 166.2 | 212.5 | 127.0 | 120 | 230.0 | 167.7 | 242.6 |

| 3 years | 120 | 240.8 | 186.3 | 277.6 | 120 | 281.2 | 105.2 | 380.3 |

| 4 years | 160 | 203.9 | 179.5 | 227.8 | 160 | 152.6 | 132.4 | 157.9 |

| 5 years | 160 | 230.7 | 170.3 | 268.0 | 160 | 219.5 | 292.7 | 182.7 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 5 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 5 | 13.1 | 11.3 | 15.2 |

| 3 years | 5 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 16.2 | 5 | 12.3 | 8.4 | 25.2 |

| 4 years | 6 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 18.5 | 6 | 12.6 | 13.9 | 10.5 |

| 5 years | 6 | 15.2 | 13.2 | 17.1 | 6 | 13.6 | 17.7 | 12.8 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.47 |

| 3 years | 0.4 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.4 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 1.21 |

| 4 years | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.82 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.53 |

| 5 years | 0.5 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.5 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Thiamine (B1) (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 0.4 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.4 | 0.90 | 0.69 | 1.12 |

| 3 years | 0.4 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.13 | 0.4 | 1.05 | 0.67 | 1.63 |

| 4 years | 0.5 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 1.61 | 0.5 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.84 |

| 5 years | 0.5 | 1.09 | 0.82 | 1.10 | 0.5 | 1.18 | 1.36 | 1.10 |

| Pyridoxine (B6) (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 0.4 | 1.48 | 1.38 | 1.65 | 0.4 | 1.53 | 1.48 | 1.58 |

| 3 years | 0.4 | 1.88 | 1.88 | 1.83 | 0.4 | 1.54 | 0.76 | 2.43 |

| 4 years | 0.5 | 2.32 | 2.27 | 2.61 | 0.5 | 1.59 | 1.53 | 1.65 |

| 5 years | 0.5 | 1.97 | 2.02 | 1.97 | 0.5 | 2.00 | 2.84 | 1.58 |

| Cobalamin (B12) (μg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 0.7 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 1.81 | 0.7 | 1.30 | 0.94 | 1.90 |

| 3 years | 0.7 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.50 | 0.7 | 1.35 | 0.64 | 4.61 |

| 4 years | 1.0 | 1.92 | 1.56 | 3.04 | 1.0 | 1.54 | 2.92 | 1.43 |

| 5 years | 1.0 | 2.67 | 1.93 | 3.44 | 1.0 | 2.67 | 1.93 | 3.44 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 25 | 78.58 | 67.35 | 81.50 | 25 | 74.11 | 69.41 | 78.80 |

| 3 years | 25 | 106.78 | 111.88 | 96.00 | 25 | 77.26 | 55.94 | 101.50 |

| 4 years | 25 | 125.05 | 125.05 | 129.40 | 25 | 98.51 | 80.86 | 104.51 |

| 5 years | 25 | 109.34 | 135.80 | 97.71 | 25 | 113.14 | 168.94 | 90.40 |

| Zinc (mg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 2.5 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 7.0 |

| 3 years | 2.5 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 9.9 |

| 4 years | 3.0 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 7.9 |

| 5 years | 3.0 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 6.7 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | ||||||||

| 2 years | 210 | 710.3 | 389.1 | 1002.9 | 210 | 500.8 | 334.8 | 585.4 |

| 3 years | 210 | 750.7 | 668.4 | 1087.4 | 210 | 420.0 | 189.9 | 1448.4 |

| 4 years | 275 | 843.3 | 745.5 | 1933.6 | 275 | 680.6 | 424.1 | 691.1 |

| 5 years | 275 | 812.1 | 669.3 | 981.9 | 275 | 894.0 | 900.6 | 887.3 |

| Nutrients/Age | Males | Females | ||||||

| Reference EAR | Median Intake | Reference EAR | Median Intake | |||||

| Total | Asesewa | Takoradi | Total | Asesewa | Takoradi | |||

| Macronutrients | ||||||||

| Energy (kcals) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 1388 | 2073.1 | 1991.7 | 2450.5 | 1244 | 2370.6 | 1942.1 | 2719.0 |

| 13 years | 1483 | 2638.5 | 2120.4 | 3766.7 | 1244 | 2241.7 | 2147.2 | 2590.6 |

| 14 years | 1579 | 2670.1 | 2173.2 | 3985.7 | 1364 | 2800.7 | 2513.1 | 3138.9 |

| 15 years | 1675 | 2245.0 | 1550.4 | 3632.2 | 1388 | 2902.5 | 1597.0 | 3354.5 |

| 16 years | 1746 | 2435.4 | 2396.7 | 2981.1 | 1411 | 2063.3 | 2016.3 | 2110.2 |

| 17 years | 1818 | 2734.6 | 2750.3 | 2734.6 | 1411 | 2078.9 | 1233.3 | 2542.3 |

| 18 years | 1842 | 2423.7 | 2423.7 | n/a | 1435 | 1896.5 | 1838.4 | 1954.6 |

| Protein (g) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 31 | 57.8 | 54.0 | 63.5 | 24 | 52.6 | 44.7 | 70.4 |

| 13 years | 31 | 61.1 | 43.0 | 86.6 | 24 | 66.2 | 58.0 | 68.3 |

| 14 years | 49 | 62.7 | 60.1 | 100.9 | 35 | 64.2 | 58.9 | 86.6 |

| 15 years | 49 | 55.7 | 31.8 | 87.6 | 35 | 66.5 | 57.6 | 83.6 |

| 16 years | 49 | 99.0 | 54.1 | 102.1 | 35 | 58.4 | 64.8 | 48.5 |

| 17 years | 49 | 69.1 | 75.9 | 58.5 | 35 | 53.8 | 41.4 | 60.6 |

| 18 years | 49 | 56.5 | 56.5 | n/a | 35 | 47.9 | 31.6 | 79.1 |

| Fat (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 70 | 68.6 | 65.5 | 68.6 | 70 | 93.3 | 71.4 | 141.1 |

| 13 years | 70 | 114.8 | 85.1 | 246.7 | 70 | 71.8 | 68.9 | 90.4 |

| 14 years | 125 | 115.2 | 67.4 | 195.5 | 85 | 89.9 | 89.9 | 82.9 |

| 15 years | 125 | 95.0 | 95.0 | 184.1 | 85 | 97.6 | 20.5 | 155.5 |

| 16 years | 125 | 64.1 | 58.0 | 82.6 | 85 | 71.2 | 60.1 | 74.9 |

| 17 years | 125 | 67.4 | 51.2 | 93.2 | 85 | 81.6 | 29.7 | 100.6 |

| 18 years | 125 | 97.1 | 97.1 | n/a | 85 | 71.9 | 48.4 | 95.4 |

| Fibre (g) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 24 | 38.7 | 36.4 | 38.7 | 20 | 30.2 | 24.6 | 48.8 |

| 13 years | 24 | 36.2 | 22.8 | 41.8 | 20 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 34.4 |

| 14 years | 28 | 52.2 | 52.2 | 63.7 | 22 | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.6 |

| 15 years | 28 | 26.4 | 14.5 | 34.1 | 22 | 48.4 | 26.6 | 66.2 |

| 16 years | 28 | 41.3 | 37.1 | 72.9 | 22 | 33.0 | 34.7 | 33.0 |

| 17 years | 28 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 43.1 | 22 | 41.2 | 29.4 | 44.3 |

| 18 years | 28 | 53.2 | 53.2 | n/a | 22 | 22.4 | 19.0 | 26.3 |

| Micronutrients | ||||||||

| Calcium (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 1050 | 676.6 | 685.8 | 676.6 | 1050 | 637.4 | 418.0 | 1053.9 |

| 13 years | 1050 | 592.1 | 435.6 | 960.6 | 1050 | 575.6 | 575.6 | 735.1 |

| 14 years | 1050 | 747.2 | 747.2 | 814.6 | 1050 | 503.6 | 591.1 | 466.0 |

| 15 years | 1050 | 779.1 | 342.5 | 876.8 | 1050 | 782.4 | 394.9 | 1148.6 |

| 16 years | 1050 | 628.8 | 589.7 | 635.2 | 1050 | 593.3 | 522.0 | 623.8 |

| 17 years | 1050 | 725.8 | 995.2 | 525.0 | 1050 | 685.0 | 596.3 | 721.1 |

| 18 years | 1050 | 1178.2 | 1178.2 | n/a | 1050 | 445.7 | 232.5 | 658.8 |

| Iron (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 6 | 20.1 | 19.8 | 20.1 | 6 | 20.9 | 15.1 | 28.8 |

| 13 years | 6 | 17.4 | 16.6 | 22.1 | 6 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 32.6 |

| 14 years | 8 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 17.8 | 8 | 16.1 | 7.2 | 21.5 |

| 15 years | 8 | 16.1 | 7.2 | 21.5 | 8 | 20.4 | 14.8 | 24.8 |

| 16 years | 8 | 24.9 | 19.3 | 36.2 | 8 | 16.8 | 19.1 | 15.9 |

| 17 years | 8 | 22.0 | 29.8 | 16.0 | 8 | 20.0 | 15.1 | 20.0 |

| 18 years | 8 | 27.0 | 27.0 | n/a | 8 | 14.1 | 13.0 | 15.2 |

| Folic acid (μg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 250 | 455.7 | 504.9 | 354.7 | 250 | 327.8 | 208.5 | 635.9 |

| 13 years | 250 | 288.5 | 166.1 | 433.8 | 250 | 238.5 | 234.4 | 409.1 |

| 14 years | 330 | 421.0 | 421.0 | 464.3 | 330 | 138.1 | 134.0 | 174.8 |

| 15 years | 330 | 261.1 | 129.6 | 279.9 | 330 | 337.9 | 147.2 | 639.3 |

| 16 years | 330 | 316.0 | 243.5 | 1052.7 | 330 | 272.7 | 282.1 | 263.4 |

| 17 years | 330 | 288.3 | 347.7 | 282.6 | 330 | 471.3 | 422.7 | 471.3 |

| 18 years | 330 | 686.6 | 686.6 | n/a | 330 | 116.1 | 97.2 | 307.5 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 9 | 16.3 | 17.7 | 15.0 | 9 | 19.1 | 16.3 | 21.0 |

| 13 years | 9 | 18.2 | 16.8 | 23.6 | 9 | 18.1 | 17.7 | 18.2 |

| 14 years | 12 | 21.0 | 18.8 | 33.5 | 11 | 18.7 | 18.7 | 18.5 |

| 15 years | 12 | 17.9 | 11.1 | 23.0 | 11 | 25.9 | 15.4 | 29.9 |

| 16 years | 12 | 28.4 | 23.5 | 36.0 | 11 | 17.1 | 16.2 | 18.1 |

| 17 years | 12 | 20.6 | 19.3 | 22.8 | 11 | 17.7 | 13.6 | 18.3 |

| 18 years | 12 | 20.7 | 20.7 | n/a | 11 | 13.2 | 8.7 | 24.7 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 0.8 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.65 |

| 13 years | 0.8 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.97 | 0.8 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.70 |

| 14 years | 1.1 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.9 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.99 |

| 15 years | 1.1 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 1.14 | 0.9 | 0.90 | 0.49 | 0.92 |

| 16 years | 1.1 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.98 | 0.9 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.65 |

| 17 years | 1.1 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.9 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.57 |

| 18 years | 1.1 | 0.74 | 0.74 | n/a | 0.9 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.82 |

| Thiamine (B1) (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 0.7 | 1.58 | 1.55 | 1.58 | 0.7 | 1.49 | 0.92 | 2.17 |

| 13 years | 0.7 | 1.53 | 1.27 | 2.69 | 0.7 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.95 |

| 14 years | 1.0 | 1.86 | 1.85 | 2.97 | 0.9 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.65 |

| 15 years | 1.0 | 0.96 | 0.51 | 1.66 | 0.9 | 1.38 | 0.77 | 2.18 |

| 16 years | 1.0 | 1.51 | 1.18 | 3.32 | 0.9 | 1.39 | 1.52 | 1.38 |

| 17 years | 1.0 | 1.43 | 1.84 | 1.10 | 0.9 | 1.41 | 1.16 | 1.46 |

| 18 years | 1.0 | 2.02 | 2.02 | n/a | 0.9 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 1.13 |

| Pyridoxine (B6) (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 0.8 | 2.42 | 2.26 | 2.70 | 0.8 | 2.61 | 1.85 | 3.33 |

| 13 years | 0.8 | 2.28 | 1.78 | 2.66 | 0.8 | 2.51 | 2.57 | 2.42 |

| 14 years | 1.1 | 3.33 | 3.21 | 3.76 | 1.0 | 1.71 | 1.71 | 1.72 |

| 15 years | 1.1 | 2.51 | 1.65 | 2.76 | 1.0 | 3.70 | 1.90 | 4.09 |

| 16 years | 1.1 | 3.40 | 3.14 | 3.46 | 1.0 | 2.53 | 1.19 | 2.68 |

| 17 years | 1.1 | 3.20 | 3.20 | 2.86 | 1.0 | 2.18 | 1.90 | 2.49 |

| 18 years | 1.1 | 3.76 | 3.76 | n/a | 1.0 | 1.26 | 0.95 | 2.87 |

| Cobalamin (B12) (μg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 1.5 | 1.95 | 1.71 | 2.78 | 1.5 | 2.15 | 2.07 | 2.50 |

| 13 years | 1.5 | 1.81 | 1.67 | 2.40 | 1.5 | 2.25 | 2.25 | 2.43 |

| 14 years | 2.0 | 1.77 | 1.14 | 2.26 | 2.0 | 2.09 | 1.93 | 2.41 |

| 15 years | 2.0 | 2.08 | 1.03 | 4.32 | 2.0 | 1.31 | 1.27 | 1.35 |

| 16 years | 2.0 | 2.75 | 1.76 | 2.86 | 2.0 | 2.03 | 1.05 | 3.70 |

| 17 years | 2.0 | 1.22 | 2.66 | 1.03 | 2.0 | 2.10 | 0.97 | 2.59 |

| 18 years | 2.0 | 1.24 | 1.24 | n/a | 2.0 | 2.39 | 2.71 | 2.07 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 28 | 131.8 | 158.0 | 131.8 | 28 | 182.7 | 177.6 | 182.7 |

| 13 years | 28 | 134.3 | 129.4 | 139.2 | 28 | 155.6 | 156.6 | 152.9 |

| 14 years | 28 | 175.6 | 224.9 | 151.9 | 28 | 101.9 | 107.3 | 96.0 |

| 15 years | 28 | 138.2 | 126.5 | 147.3 | 28 | 173.7 | 92.5 | 214.6 |

| 16 years | 28 | 215.0 | 221.4 | 215.0 | 28 | 125.8 | 185.2 | 125.3 |

| 17 years | 28 | 174.7 | 174.8 | 149.7 | 28 | 132.7 | 129.1 | 132.7 |

| 18 years | 28 | 332.2 | 332.2 | n/a | 28 | 136.5 | 127.5 | 152.3 |

| Zinc (mg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 5 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 5 | 8.1 | 6.1 | 9.9 |

| 13 years | 5 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 13.3 | 5 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 9.5 |

| 14 years | 11 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 14.6 | 6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 10.2 |

| 15 years | 11 | 8.6 | 4.8 | 10.1 | 6 | 10.1 | 6.2 | 12.0 |

| 16 years | 11 | 12.4 | 7.8 | 14.3 | 6 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 6.9 |

| 17 years | 11 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 10.9 | 6 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 8.9 |

| 18 years | 11 | 9.2 | 9.2 | n/a | 6 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 11.2 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | ||||||||

| 12 years | 445 | 882.6 | 839.2 | 898.5 | 420 | 1200.1 | 785.0 | 1539.0 |

| 13 years | 445 | 1173.1 | 856.7 | 1599.8 | 420 | 882.9 | 855.9 | 882.9 |

| 14 years | 630 | 1164.4 | 1060.9 | 1225.7 | 485 | 888.7 | 747.4 | 1209.6 |

| 15 years | 630 | 1053.9 | 1053.9 | 1501.7 | 485 | 1141.5 | 621.6 | 1747.7 |

| 16 years | 630 | 732.3 | 748.6 | 679.1 | 485 | 1071.1 | 1111.4 | 1056.8 |

| 17 years | 630 | 861.5 | 744.7 | 863.6 | 485 | 1167.1 | 590.8 | 1210.8 |

| 18 years | 630 | 1271.2 | 1271.2 | n/a | 485 | 715.9 | 310.8 | 1121.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).