Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Eligibility Criteria, and Sample Size

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Socio-Demographic Data and Anthropometric Measurement

2.4. Nutritional Analysis

2.5. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Recommended Energy and Nutrient Intakes

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dukhi, N. Global prevalence of malnutrition: evidence from literature. Malnutrition. 2020, 1, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Azeez TA. Obesity in Africa: the challenges of a rising epidemic in the midst of dwindling resources. Obes Medicine. 2022, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Micronutrient deficiencies. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients. (Accessed on 10th June 2025).

- Liu, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Jiang, S.; Han, L.; Kang, Z.; Shan, L.; Liang, L.; Wu, Q. Evolving Patterns of Nutritional Deficiencies Burden in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Findings from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 9-31. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A.; Pasricha, S.R. Anemia: Worldwide Prevalence and Progress in Reduction in Nutritional Anemia. Springer. 2022, 3-17. [CrossRef]

- Rohner, F.; Tanumihardjo, S.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Williams, T. N.; Wirth, J. P.; Petry, N.; Woodruff, B.A. Revised Survey Protocol: Ghana Micronutrient Survey. 2017. (GMS 2017). Available online: https://osf.io/vk53j/download.

- Ofori-Asenso, R.; Agyeman, A. A.; Laar, A.; Boateng, D. Overweight and Obesity epidemic in Ghana - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016, 16, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Asosega, K.A.; Adebanji, A.O.; Abdul, I.W. Spatial analysis of the Prevalence of Obesity and Overweight among women in Ghana. BMJ Open. 2021, 11(1), 3-21. [CrossRef]

- Asosega, K. A.; Aidoo, E. N.; Adebanji, A. O.; Owusu-Dabo, E. (2023). Examining the risk factors for Overweight and Obesity among women in Ghana: A multilevel perspective. Heliyon. 2023, 9(5), 2-14. [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.K.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Bentil, H.J.; Rohner, F.; Wegmüller, R.; Petry, N.; Wirth, J.P.; Donkor, W.E.S.; Amoaful, E.F.; Adu-Afarwuah, S. Co-Occurrence of Overweight/Obesity, Anemia and Micronutrient Deficiencies among Non-Pregnant Women of Reproductive Age in Ghana: Results from a Nationally Representative Survey. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 1427. [CrossRef]

- Kushitor, S.B.; Owusu, L.; Kushitor, M.K. The prevalence and correlates of the double burden of malnutrition among women in Ghana. Plos one. 2022, 15(12), 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Arthur, F.; Situma, R.; Aballo, J.; Mahama, A.B.; Selenje, L.; Amoaful, E.; Adu-Afarwuah, S. Lessons learned from implementing the pilot Micronutrient Powder Initiative in four districts in Ghana. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Wegmüller, R.; Bentil, H.; Wirth, J.P.; Petry, N.; Tanumihardjo, S.A.; Allen, L.; Williams, T.N.; Selenje, L.; Mahama, A.; Amoaful, E.; Steiner-Asiedu, M. Anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, malaria, hemoglobinopathies and malnutrition in young children and non-pregnant women in Ghana: Findings from a national survey. PloS one. 2020, 15(1), p.e0228258. [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, S.A.; Antwi, M.H.; Ahenkorah, F.L.; Laing, E.F.; Ephraim, R.K.D.; Kwarteng, A.; Amoani, B.; Appiah, S.C.; Oppong Afranie, B.; Opoku, S. et al. Vitamin D deficiency is common in Ghana despite abundance of sunlight: a multicentre comparative cross-sectional study. J Nutr Metab. 2021, 1, 12-31. [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, M.A.; Apprey, C.; Annan, R.A. Dietary Diversity and Nutritional Status of Adolescents in Rural Ghana. Nutr Metab Insights. 2023, 16, 117-28. [CrossRef]

- Asare, J.; Lim, J.J.; Amoah, J. Low Dietary Diversity and Low Haemoglobin Status in Ghanaian Female Boarding and Day Senior High School Students: a cross-sectional study. Medicina. 2024, 60(7), 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Abizari, A.R.; Ali, Z. Dietary patterns and associated factors of schooling Ghanaian adolescents. J Health Popul Nutr. 2019, 38(1), 105-13. [CrossRef]

- Galbete, C.; Nicolaou, M.; Meeks, K.A.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Addo, J.; Amoah, S.K.; Smeeth, L.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Bahendeka, S. et al. Food consumption, nutrient intake, and dietary patterns in Ghanaian migrants in Europe and their compatriots in Ghana. Food and Nutr Res. 2017, 12-23. [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A.; Nwabuikwu, O.; Bannerman, B.; Ador, G.; Atadze, V.; Asante, M.; Bempong, S.; McCloskey, P.; Nguyen, P.H.; Hughes, D. et al. Computer vision–assisted dietary assessment through mobile phones in female youth in urban Ghana: validity against weighed records and comparison with 24-h recalls. Am J of Clin Nutr. 2024, 120(5), 1105-13. [CrossRef]

- Folson, G.K., Bannerman, B., Atadze, V., Ador, G., Kolt, B., McCloskey, P., Gangupantulu, R., Arrieta, A., Braga, B.C., Arsenault, J. et al. Validation of mobile artificial intelligence technology–assisted dietary assessment tool against weighed records and 24-hour recall in adolescent females in Ghana. J of Nutr. 2023, 153(8), 2328-38. [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Slowinska, M.A.; Slowinski, D.; Dlugosz, A.; Niedzwiedzka, E.; Wadolowska, L. Comparison of a Full Food-Frequency Questionnaire with the Three-Day Unweighted Food Records in Young Polish Adult Women: Implications for Dietary Assessment. Nutrients. 2013, 5, 2747-2776. [CrossRef]

- Human Energy Requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y5686e/y5686e00.htm (Accessed on 12th January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241546123. (Accessed on 12th January 2025).

- Jobarteh, M.L.; McCrory, M.A.; Lo, B.; Sun, M.; Sazonov, E.; Anderson, A.K.; Jia, W.; Maitland, K.; Qiu, J.; Steiner-Asiedu, M. et al. Development and validation of an objective, passive dietary assessment method for estimating food and nutrient intake in households in low-and middle-income countries: A study protocol. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020, 4(2), 3-19. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. (Accessed on 11th April 2025).

- Ghosh, T.; McCrory, M.A.; Marden, T.; Higgins, J.; Anderson, A.K.; Domfe, C.A.; Jia, W.; Lo, B.; Frost, G.; Steiner-Asiedu, M. et al. I2N: image to nutrients, a sensor-guided semi-automated tool for annotation of images for nutrition analysis of eating episodes. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 3-21. [CrossRef]

- Domfe, C.A.; McCrory, M.A.; Sazonov, E.; Ghosh, T.; Raju, V.; Frost, G.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Sun, M.; Jia, W.; Baranowski, T. et al. Objective assessment of shared plate eating using a wearable camera in urban and rural households in Ghana. Front Nutr. 2024, 11, 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.A.; Adolph, A.L.; Butte, N.F. Nutrient Adequacy and Diet Quality in Non-Overweight and Overweight Hispanic Children of Low Socioeconomic Status: The Viva la Familia Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009, 109(6), 1012-21. [CrossRef]

- Ghana Steps Report. Nationwide Non-Communicable Diseases Risk Factors Assessment Using the World Health Organization’s Stepwise Approach in Ghana. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2024-11/ghana%20steps%20report%202023. (Accessed on 12th February 2025).

- Block, G.; Hartman, A.M. Dietary assessment methods. In Nutrition and Cancer Prevention. CRC Press. 2021, 1, 159-180. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.S.; Charrondiere, U.R.; Bell, W. Measurement errors in dietary assessment using self-reported 24-hour recalls in low-income countries and strategies for their prevention. Advances in Nutr. 2017, 8(6), 980-91. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Guenther, P.M.; Durward, C.; Douglass, D.; Zimmerman, T.P.; Kahle, L.L.; Atoloye, A.T.; Marcinow, M.L.; Savoie-Roskos, M.R., Herrick, K.A. et al. The accuracy of portion size reporting on self-administered online 24-hour dietary recalls among women with low incomes. J of the Aca of Nutr and Dietetics. 2022, 122(12), 2243-2256. [CrossRef]

- Rossato, S.L.; Fuchs, S.C. Handling random errors and biases in methods used for short-term dietary assessment. Revista de saude publica. 2014, 845-50. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K. Nutritional quality of meals and snacks assessed by the Food Standards Agency nutrient profiling system in relation to overall diet quality, body mass index, and waist circumference in British adults. Nutr J. 2017, 16, 101-22. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.K.; Roberts, S.B.; Howarth, N.C.; McCrory, M.A. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Res. 2005, 13(7), 1205-17. [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, C.; Kushitor, S.B.; Afrifa-Anane, G.F. Obesity in Africa: A Silent Public Health Crisis. Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Textbook: Springer. 2024, 47-64. [CrossRef]

- Owoo, N.S.; Lambon-Quayefio, M.P. Mixed methods exploration of Ghanaian women’s domestic work, childcare and effects on their mental health. PLoS One. 2021, 16(2), 2-19. [CrossRef]

- de Jager, I.; van de Ven, G.W.J.; Giller, K.E. Seasonality and nutrition-sensitive farming in rural Northern Ghana. Food Secur. 2023, 15(2), 381-94. [CrossRef]

- Rousham, E.K.; Pradeilles, R.; Akparibo, R.; Aryeetey, R.; Bash, K.; Booth, A.; Muthuri, S.K.; Osei-Kwasi, H.; Marr, C.M.; Norris, T. Dietary behaviours in the context of nutrition transition: a systematic review and meta-analyses in two African countries. Public Health Nutr 2020, 23(11), 1948-64. [CrossRef]

- Niyi, J.L.; Li, Z.; Zumah, F. Association between Gestational Weight Gain and Maternal and Birth Outcomes in Northern Ghana. BioMed Res Int. 2024, 11-29. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Trends in cardiovascular diseases and associated risks in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the evidence for Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, and Tanzania. The aging male. 2019, 22(3), 169-76. [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, K.; Nyamari, J.M.; Ganu, D.; Appiah, S.; Pan, X.; Kaminga, A.; Liu, A. Predictors of hypertension among adult female population in Kpone-Katamanso District, Ghana. Int J of hypertension. 2019, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Appiah, C.A.; Samwini, A.M.; Brown, P.K.; Hayford, F.E.A.; Asamoah-Boakye, O. Proximate composition and serving sizes of selected composite Ghanaian soups. Afr J Food, Agric Nutr Dev. 2020, 20(3), 22-43. [CrossRef]

- Eyeson, K.; Ankrah, E. Composition of foods commonly used in Ghana: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). Food Res. 2001, 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Waddell, I.S.; Orfila, C. Dietary fiber in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases: From epidemiological evidence to potential molecular mechanisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Nti CA (2008) Household dietary practices and family nutritional status in rural Ghana. Nutr Res Pract. 2008, 2(1), 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Osei, P.K.; McCrory, M.A.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Sazonov, E.; Sun, M.; Jia, W.; Baranowski, T.; Frost, G.; Lo, B.; Anderson, A.K. Food-related behaviors of rural (Asaase Kooko) and peri-urban (Kaadjanor) households in Ghana. Frontiers in Nutr. 2025, 12, 2-13. [CrossRef]

- Kushitor, S.B.; Alangea, D.O.; Aryeetey, R.; de-Graft Aikins, A. Dietary patterns among adults in three low-income urban communities in Accra, Ghana. Plos one. 2023, 18(11), p.e0293726. [CrossRef]

- Hiamey, S.E.; Hiamey, G.A. Street food consumption in a Ghanaian Metropolis: the concerns determining consumption and non-consumption. Food Control. 2018, 92, 121-7. [CrossRef]

- Ayensu, J.; Annan, R.; Lutterodt, H.; Edusei, A.; Peng, L.S. Prevalence of anaemia and low intake of dietary nutrients in pregnant women living in rural and urban areas in the Ashanti region of Ghana. PLoS One. 2020, 15(1), 2-16. [CrossRef]

- Dass, M.; Nyako, J.; Tortoe, C.; Fanou-Fogny, N.; Nago, E.; Hounhouigan, J.; Berger, J.; Wieringa, F.; Greffeuille, V. Comparison of micronutrient intervention strategies in Ghana and Benin to cover micronutrient needs: simulation of benefits and risks in women of reproductive age. Nutrients. 2021, 13(7), 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Imbard, A.; Benoist, J-F.; Blom, H.J. Neural tube defects, folic acid, and methylation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013, 10(9), 10-26. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Kuizon, S.; Junaid, M.A. Folic acid supplementation in pregnancy and implications in health and disease. J Biomed Sci. 2014, 21, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.; Adam, A.; Nangkuu, D. Prevalence of neural tube defect and hydrocephalus in Northern Ghana. J Med Biomed Sci. 2017, 6(1), 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Ankwah, Y.K.; Larbie, C.; Genfi, A.K.A. Assessing the prevalence and risk factors of neural tube defects at a tertiary hospital in Ghana. Int J Child Health Hum Dev. 2022, 15(2), 193-203. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/assessing-prevalence-risk-factors-neural-tube/docview/2779948796/se-2?accountid=14537. (Accessed on 10th January 2025).

| Outcome variables | Rural (n = 26) | Urban (n = 28) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

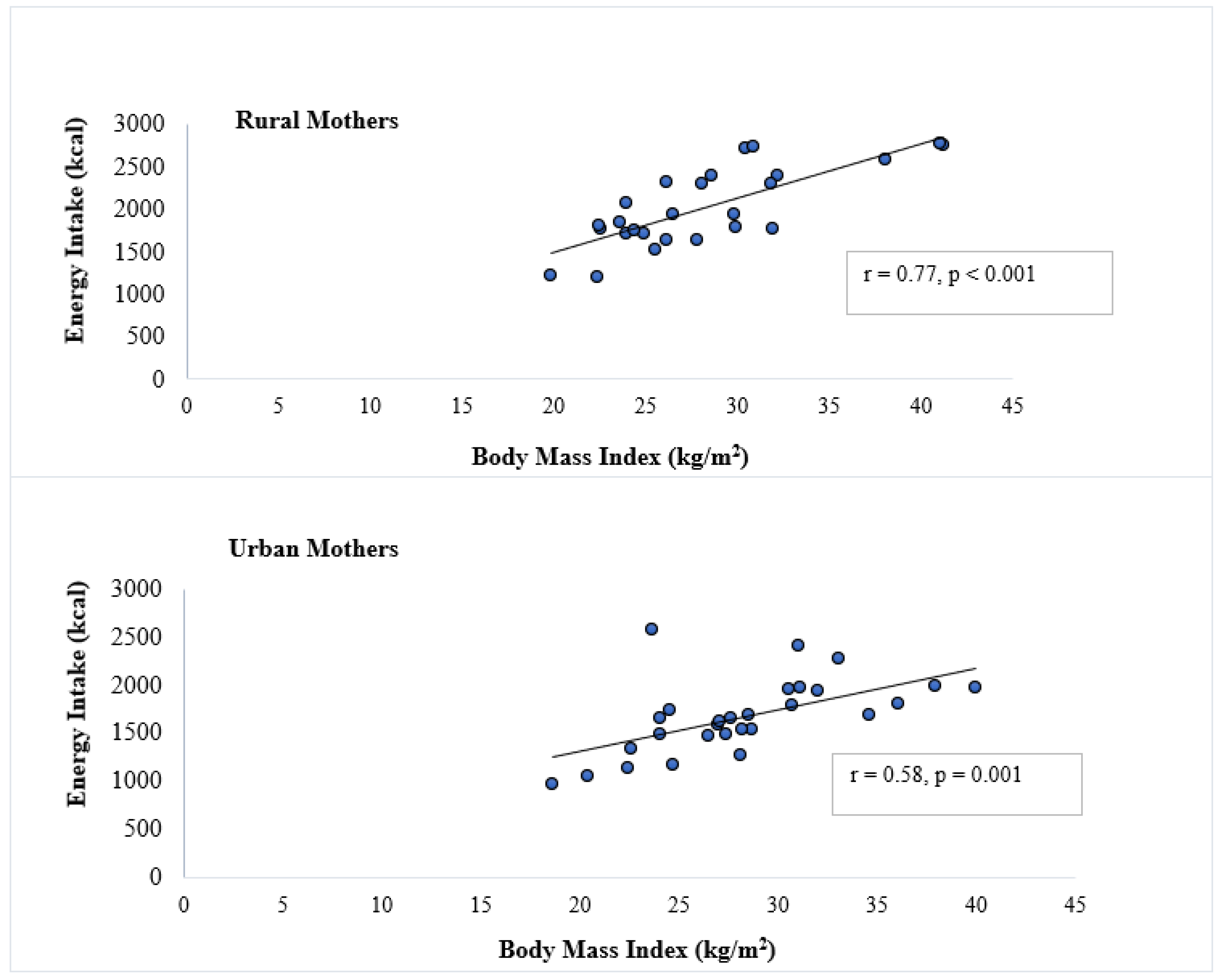

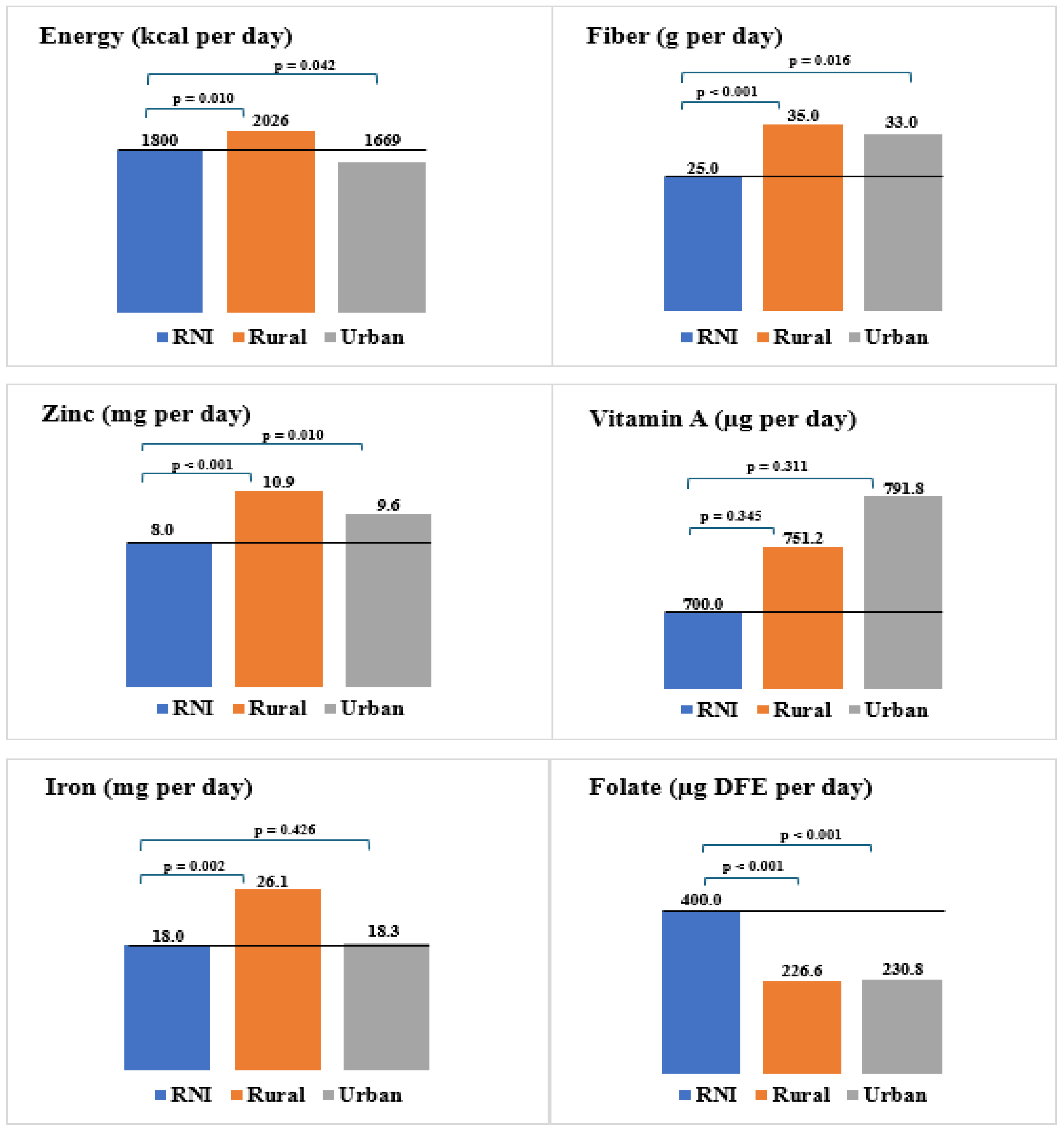

| Energy (kcal) | 2026 ± 461 | 1669 ± 385 | 0.002 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 325.8 ± 43.6 | 249.6 ± 42.2 | < 0.001 |

| Protein (g) | 66.6 ± 21.4 | 57.5 ± 12.3 | 0.040 |

| Fat (g) | 51.0 ± 10.6 | 49.1 ± 9.7 | 0.431 |

| Fiber (g) | 35.0 ± 11.5 | 33.0 ± 18.7 | 0.317 |

| Zinc (mg) | 10.9 ± 3.6 | 9.6 ± 3.4 | 0.089 |

| Iron (mg) | 26.1 ± 13.1 | 18.3 ± 7.4 | 0.004 |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 751.2 ± 126.5 | 791.8 ± 184.3 | 0.429 |

| Folate (µg DFE) | 226.6 ± 95.1 | 230.8 ± 122.6 | 0.444 |

| Outcome Variables | Below RNIs % (n) | Met RNIs % (n) | Exceeded RNIs % (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | |

| Energy (kcal) | 7.7 (2) | 21.4 (6) | 42.3(14) | 67.9 (20) | 38.5 (10) | 7.1 (2) |

| Fiber (g) | 3.8 (1) | 7.1 (2) | 84.6 (22) | 82.1 (23) | 11.5 (3) | 10.7 (3) |

| Zinc (mg) | 7.7 (2) | 10.7 (3) | 80.8 (21) | 78.6 (22) | 11.5 (3) | 10.7 (3) |

| Iron (mg) | 0.0 (0) | 14.3 (4) | 76.9 (20) | 82.1 (23) | 23.1 (6) | 3.6 (1) |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 92.3 (24) | 92.9 (26) | 7.7 (2) | 7.1 (2) |

| Folate (µg DFE) | 46.2 (12) | 53.6 (15) | 53.8 (14) | 46.4 (13) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).