Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Traps

2.2. Design

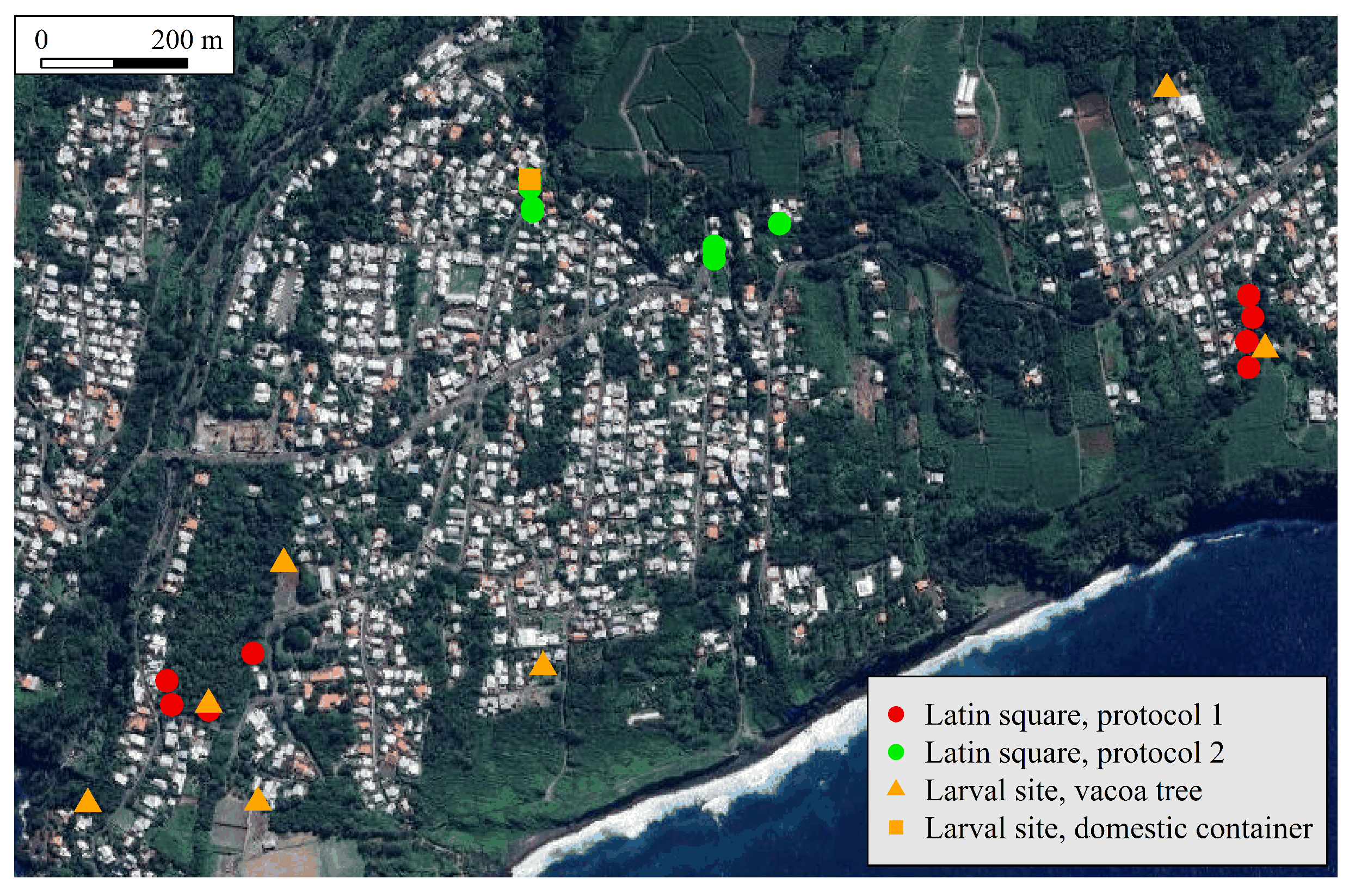

- Protocol 1: a ravine located in the eastern part of the study site, and an orchard located in its western part;

- Protocol 2: two close sets located in an urban area located in the northern part of the study site.

2.3. Larval Habitat

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

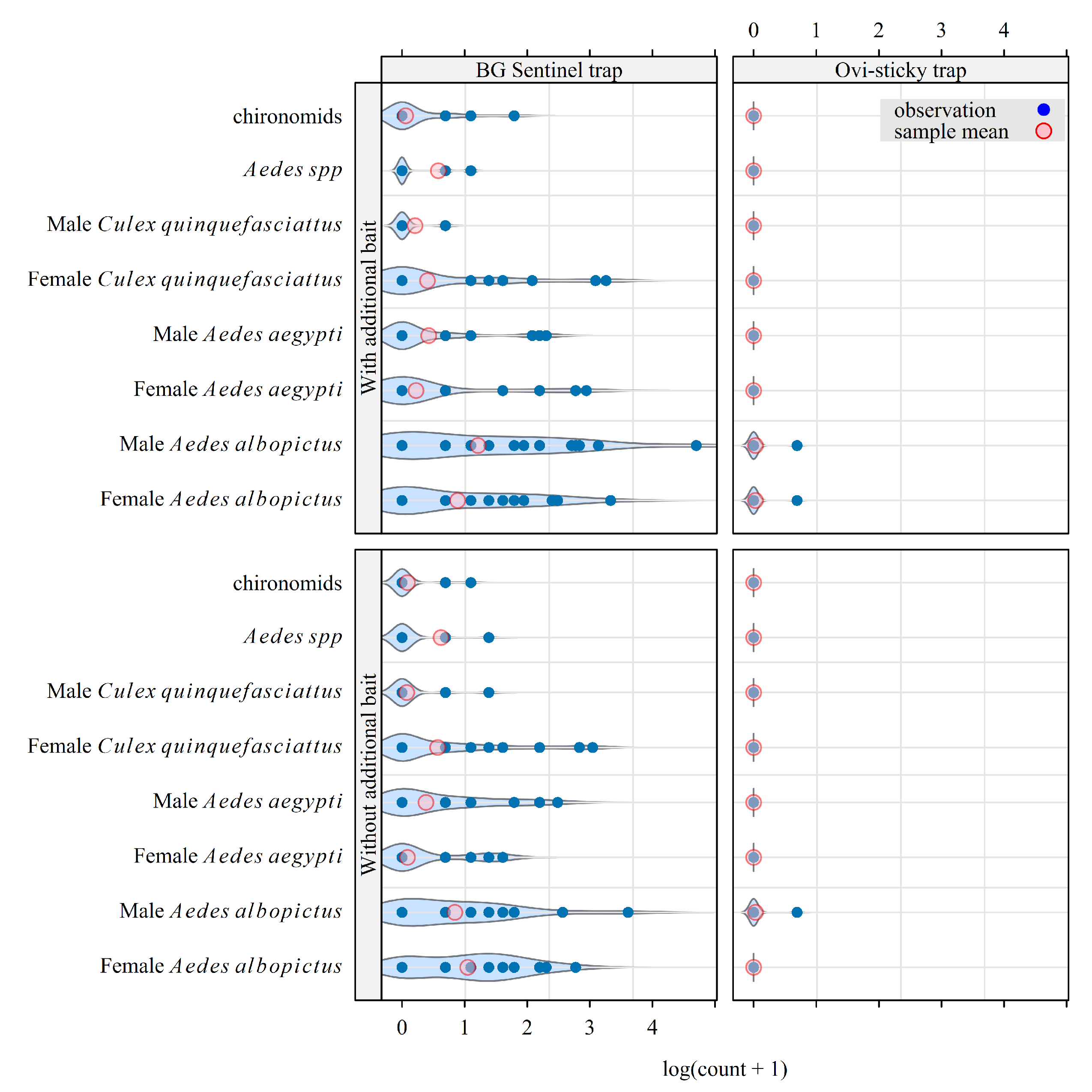

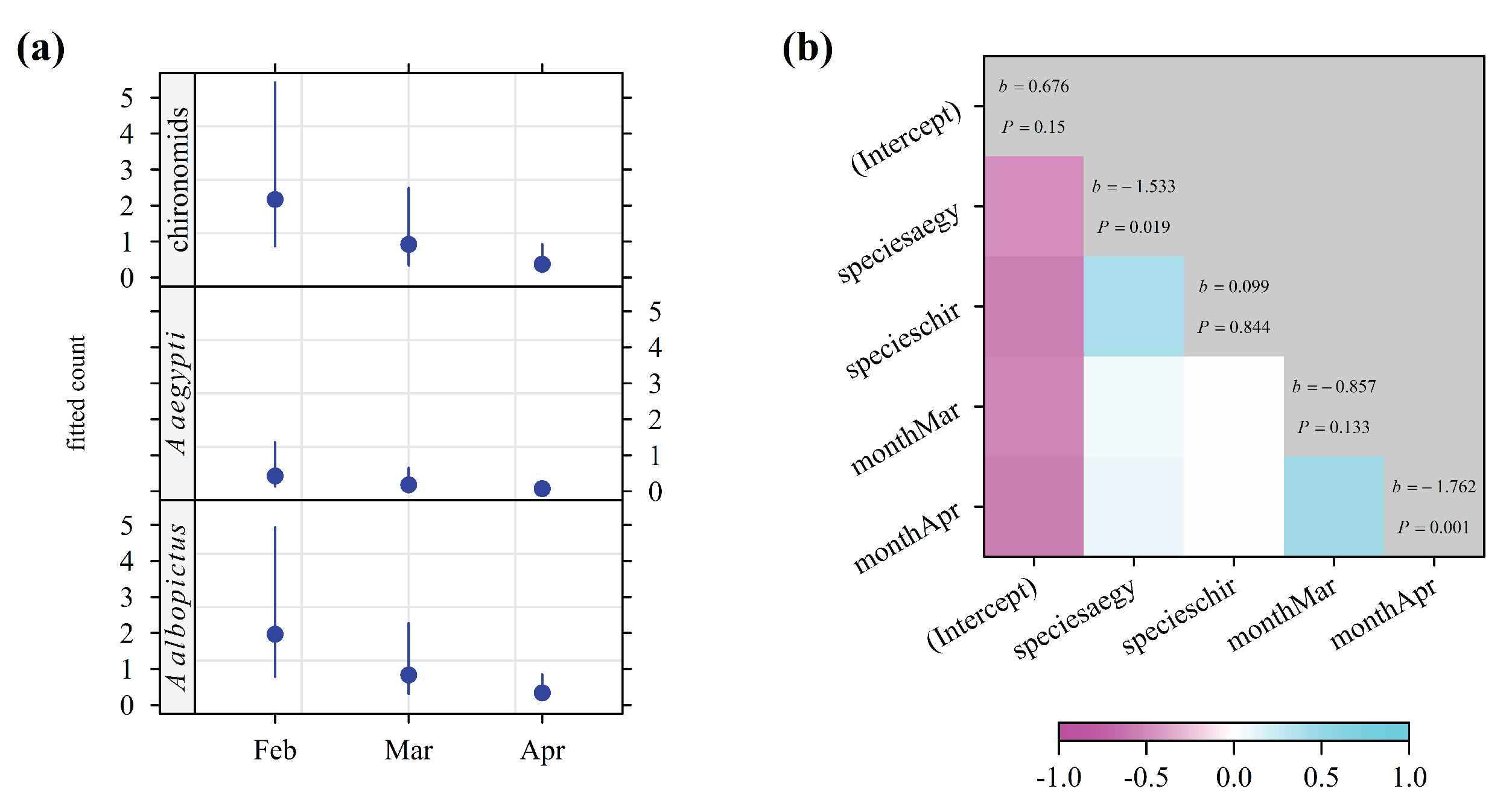

3.1. Insect Catches

3.2. Effect of Lure on CO2-Baited Traps Attractiveness

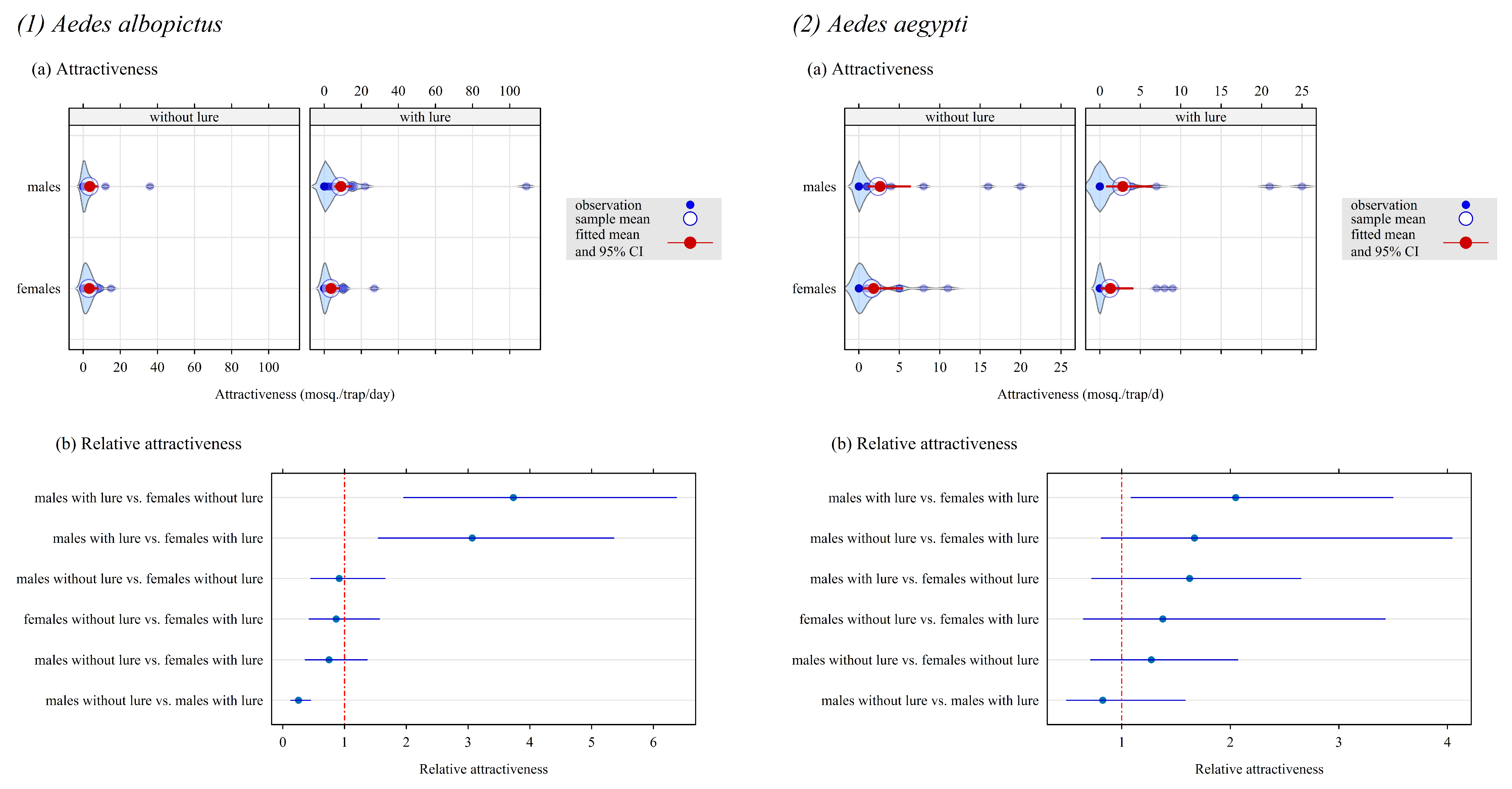

- Without lure, the attractiveness of the CO2-baited trap was the same for the females and the males.

- With lure, the attractiveness of the CO2-baited trap was unchanged for the females. In contrast, it was 3 times higher for male than for female Ae. albopictus: relative attractiveness , 95% credible interval [1.6; 5.5], and 2 times higher for male than for female Ae. aegypti: [1.1; 3.5].

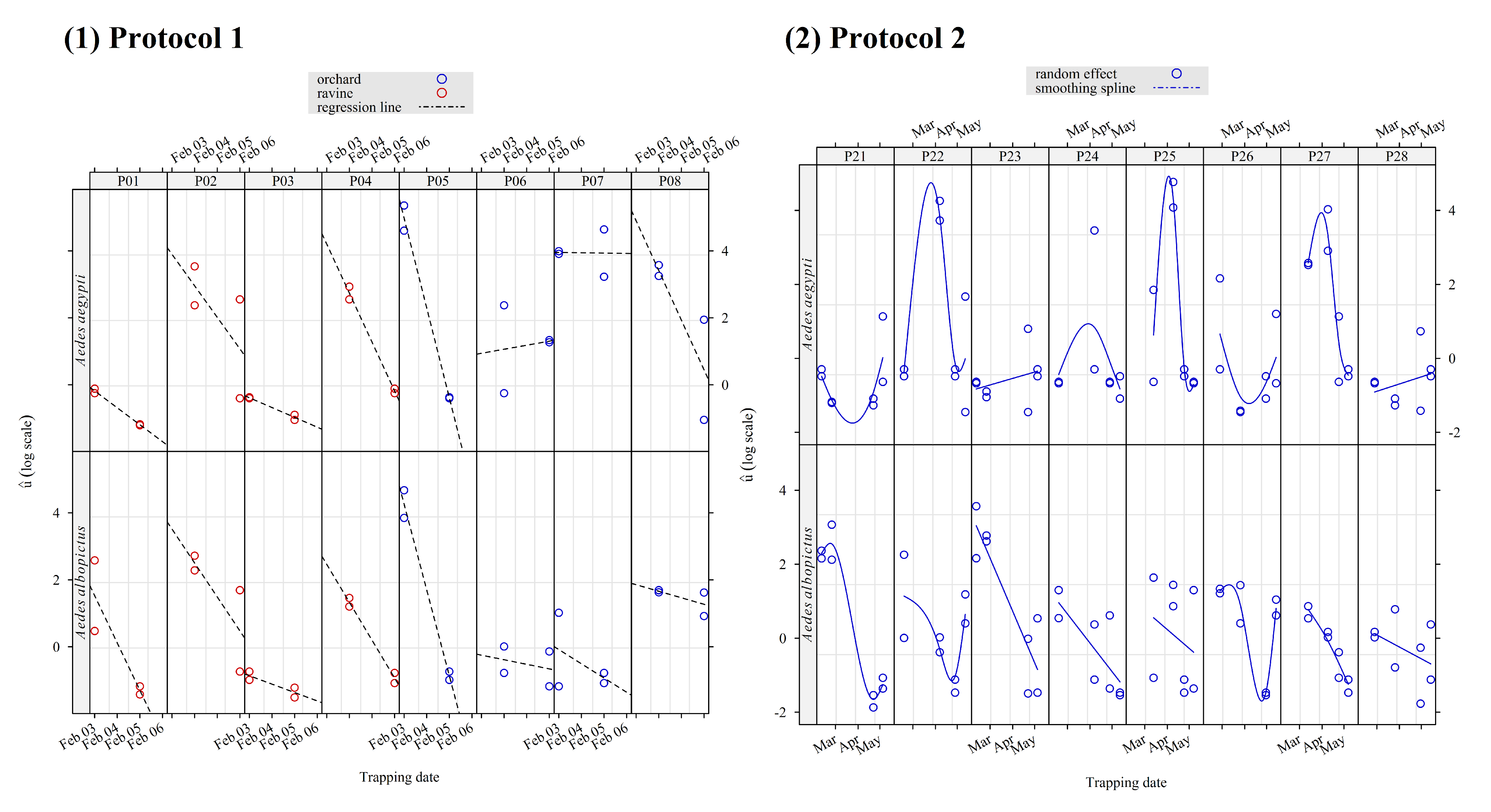

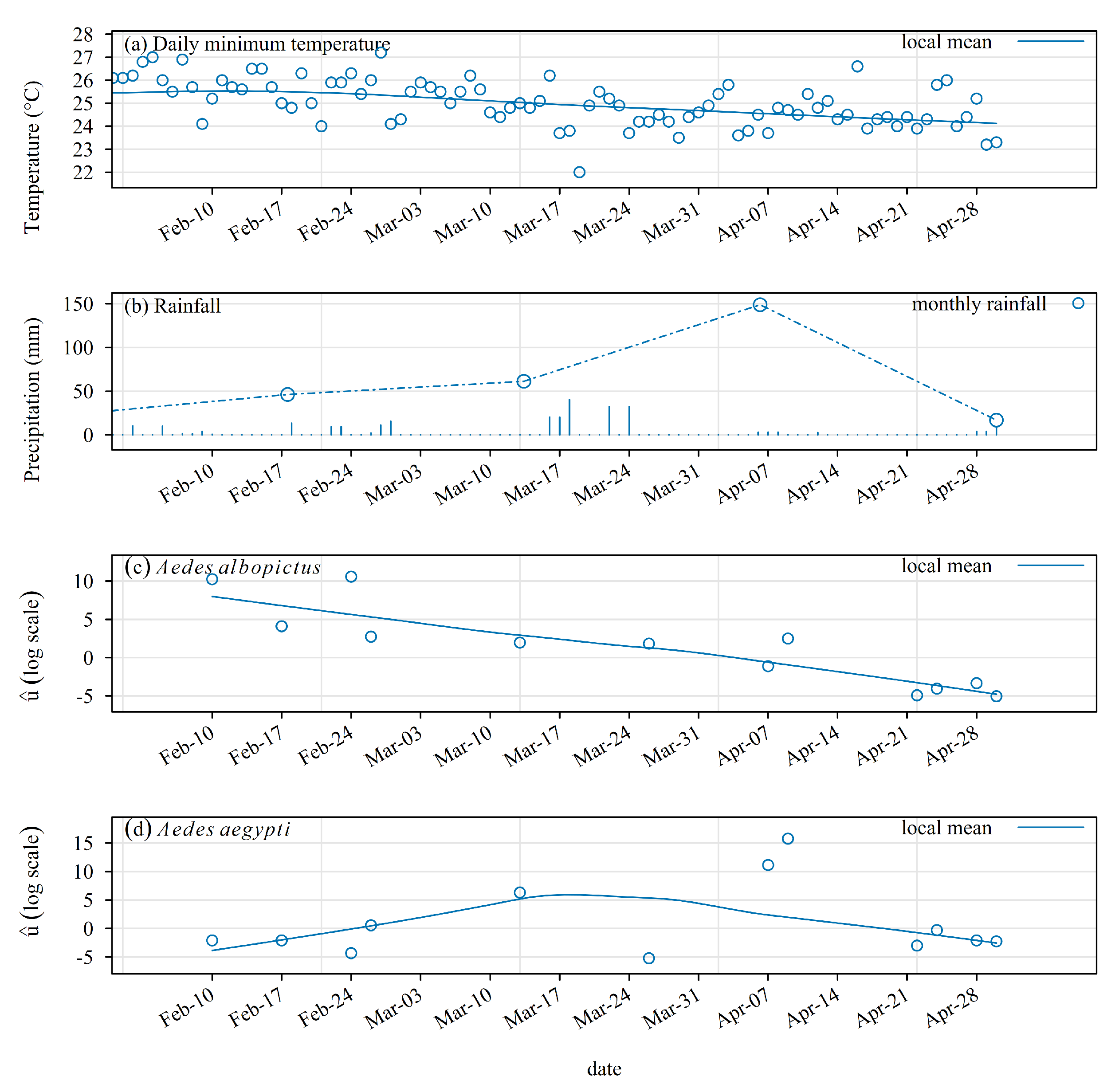

3.3. Variation in Space and Time

3.4. Larvae

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ae. aegypti | Aedes aegypti |

| Ae. albopictus | Aedes albopictus |

| BG | Biogents, Germany |

| BGS | Biogents Sentinel, Germany |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| FEDER | Fonds Européen de Développement Régional |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| OpTIS | Opérationalisation de la technique de l’insecte stérile |

| SIT | Sterile Insect Technique |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

References

- Salvan, M.; Mouchet, J. Aedes albopictus et Aedes aegypti à l’Ile de La Réunion [Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti at Ile de la Réunion]. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 1994, 74, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delatte, H.; Dehecq, J.S.; Thiria, J.; Domerg, C.; Paupy, C.; Fontenille, D. Geographic Distribution and Developmental Sites of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) During a Chikungunya Epidemic Event. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Larrieu, S.; Vilain, P.; Etienne, A.; Solet, J.L.; François, C.; Roquebert, B.; Bandjee, M.C.J.; Filleul, L.; Menudier, L. From the threat to the large outbreak: dengue on Reunion Island, 2015 to 2018. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Paty, M.C.; Gerardin, P.; Balleydier, E.; Etienne, A.; Daoudi, J.; Thouillot, F.; Jaffar-Bandjee, M.C.; Menudier, L. From dengue outbreaks to endemicity: Reunion Island, France, 2018 to 2021. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumahoro, M.K.; Boelle, P.Y.; Gaüzere, B.A.; Atsou, K.; Pelat, C.; Lambert, B.; La Ruche, G.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, M.; Renault, P.; Sarazin, M.; et al. The Chikungunya epidemic on La Réunion Island in 2005-2006: a cost-of-illness study. PLoS Neglect.Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumence, E.; Piorkowski, G.; Traversier, N.; Amaral, R.; Vincent, M.; Mercier, A.; Ayhan, N.; Souply, L.; Pezzi, L.; Lier, C.; et al. Genomic insights into the re-emergence of chikungunya virus on Réunion Island, France, 2024 to 2025. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, J. Current status of the sterile insect technique for the suppression of mosquito populations on a global scale. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyer, J.; Lefrançois, T. Boosting the sterile insect technique to control mosquitoes. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, M.; Lancelot, R.; Diouf, G.; Malfacini, M.; Marquereau, L.; Gouagna, L.C.; Rossignol, M.; Chandre, F.; Baldet, T.; Bouyer, J. Comparison of the standard and boosted sterile insect techniques for the suppression of Aedes albopictus populations under semi-field conditions. Parasites 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyer, J.; Almenar Gil, D.; Pla Mora, I.; Dalmau Sorli, V.; Maïga, H.; Mamai, W.; Claudel, I.; Brouazin, R.; Yamada, H.; Gouagna, L.C.; et al. Suppression of Aedes mosquito populations with the boosted sterile insect technique in tropical and Mediterranean urban areas. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudel, I.; Brouazin, R.; Lancelot, R.; Gouagna, L.C.; Dupraz, M.; Baldet, T.; Bouyer, J. Optimization of adult mosquito trap settings to monitor populations of Aedes and Culex mosquitoes, vectors of arboviruses in La Reunion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.H.; Lim, J.T.; Ong, J.; Hapuarachchi, H.C.; Sim, S.; Ng, L.C. Singapore’s 5 decades of dengue prevention and control-Implications for global dengue control. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2023, 17, e0011400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; Lim, J.T.; Chong, C.S.; Dickens, B.; Ng, Y.; Deng, L.; Lee, C.; Tan, L.Y.; Kakani, E.G.; Yoong, Y.; et al. Effectiveness of Wolbachia-mediated sterility coupled with sterile insect technique to suppress adult Aedes aegypti populations in Singapore: a synthetic control study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2024, 8, e617–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouazin, R.; Claudel, I.; Lancelot, R.; Dupuy, G.; Gouagna, L.C.; Dupraz, M.; Baldet, T.; Bouyer, J. Optimization of oviposition trap settings to monitor populations of Aedes mosquitoes, vectors of arboviruses in La Reunion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARS Réunion. Clé d’identification des moustiques de La Réunion aux stades adulte et larvaires. Technical report, ARS Réunion, 2025.

- Harrison, X.A. Using observation-level random effects to model overdispersion in count data in ecology and evolution. PeerJ 2014, 2, e616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rue, H.; Riebler, A.I.; Sørbye, S.H.; Illian, J.B.; Simpson, D.P.; Lindgren, F.K. Bayesian computing with INLA: A review. Annual Reviews of Statistics and Its Applications 2017, 4, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. In R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Burnham, K.; Anderson, D. Kullback-Leibler information as a basis for strong inference in ecological studies. Wildlife Research 2001, 28, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, A.B.B.; Carvajal, A.; Medina, J.; Anderson, M.; Nieves, V.J.; Ramirez, M.; Vasquez, C.; Petrie, W.; Cardenas, G.; Beier, J.C. Assessment of the effectiveness of BG-Sentinel traps baited with CO2 and BG-Lure for the surveillance of vector mosquitoes in Miami-Dade County, Florida. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0212688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatte, H.; Toty, C.; Boyer, S.; Bouetard, A.; Bastien, F.; Fontenille, D. Evidence of habitat structuring Aedes albopictus populations in Réunion Island. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2013, 7, e2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, E.; Bernard, C.; Lecollinet, S.; Rakotoharinome, V.; Ravaomanana, J.; Roger, M.; Olive, M.; Meenowa, D.; Jaumally, M.; Melanie, J.; et al. West Nile virus infection in horses, Indian Ocean. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2017, 53, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagny, L.; Delatte, H.; Quilici, S.; Fontenille, D. Progressive Decrease in Aedes aegypti Distribution in Reunion Island Since the 1900s. J. Med. Entomol. 2009, 46, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyaloo, D.P.; Bouyer, J.; Facknath, S.; Bheecarry, A. Pilot Suppression trial of Aedes albopictus mosquitoes through an Integrated Vector Management strategy including the Sterile Insect Technique in Mauritius. bioRxiv 2020, 2020, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomard, Y.; Lebon, C.; Mavingui, P.; Atyame, C.M. Contrasted transmission efficiency of Zika virus strains by mosquito species Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus from Reunion Island. Parasite. Vector. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidlingmayer, W.L. A comparison of trapping methods for adult mosquitoes: species response and environmental influence. Journal of medical entomology 1967, 4, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).