Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Study Design

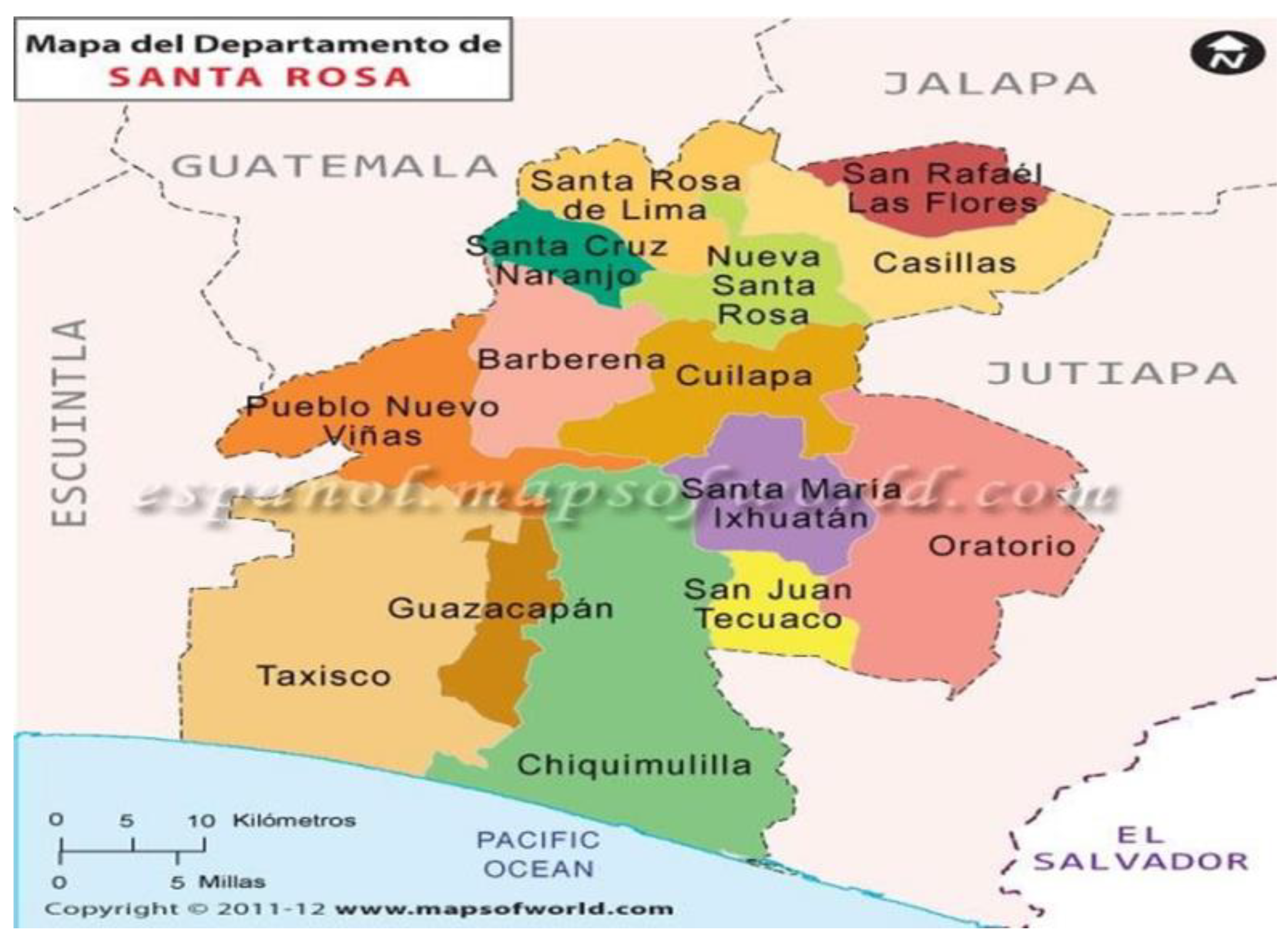

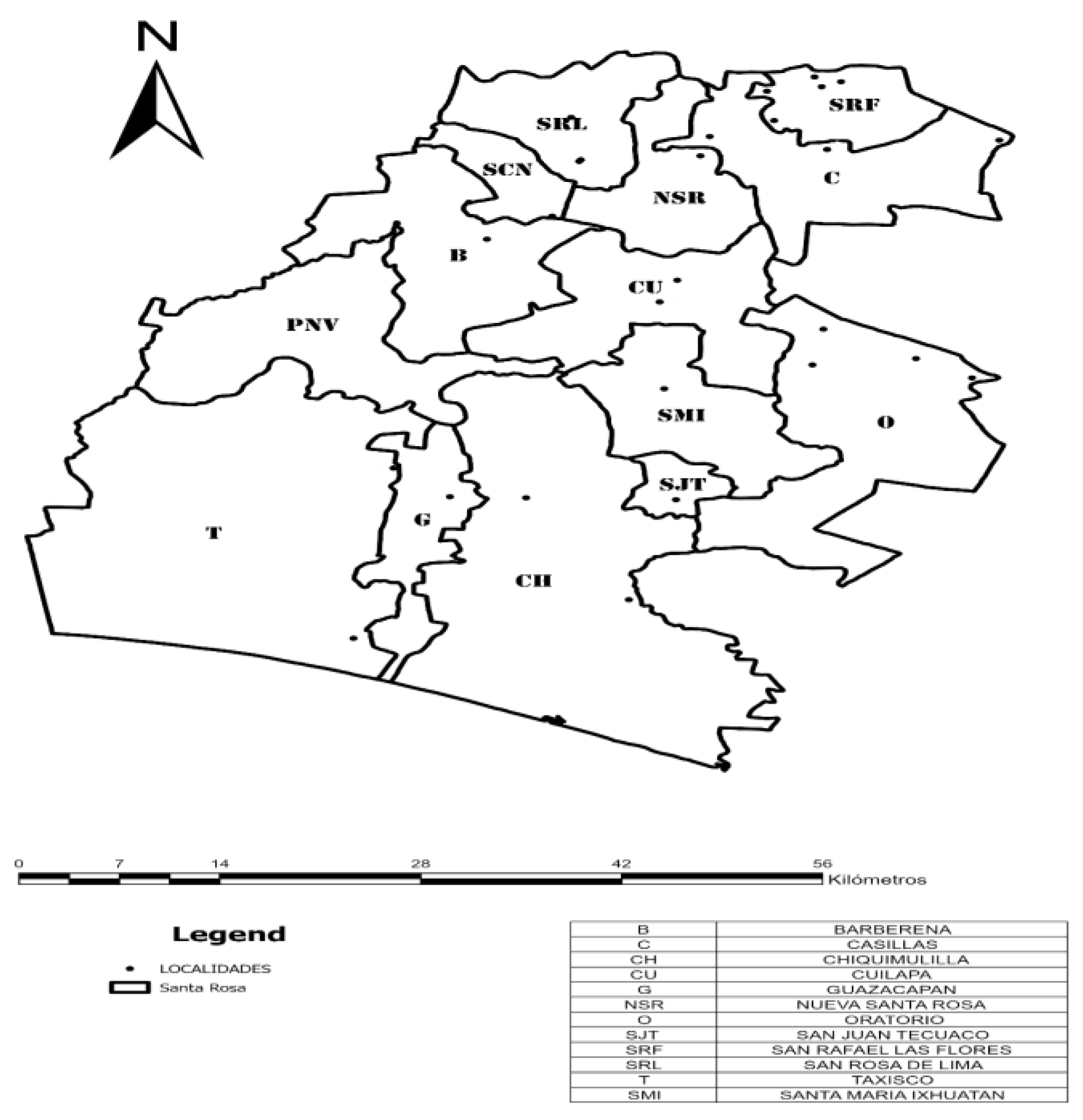

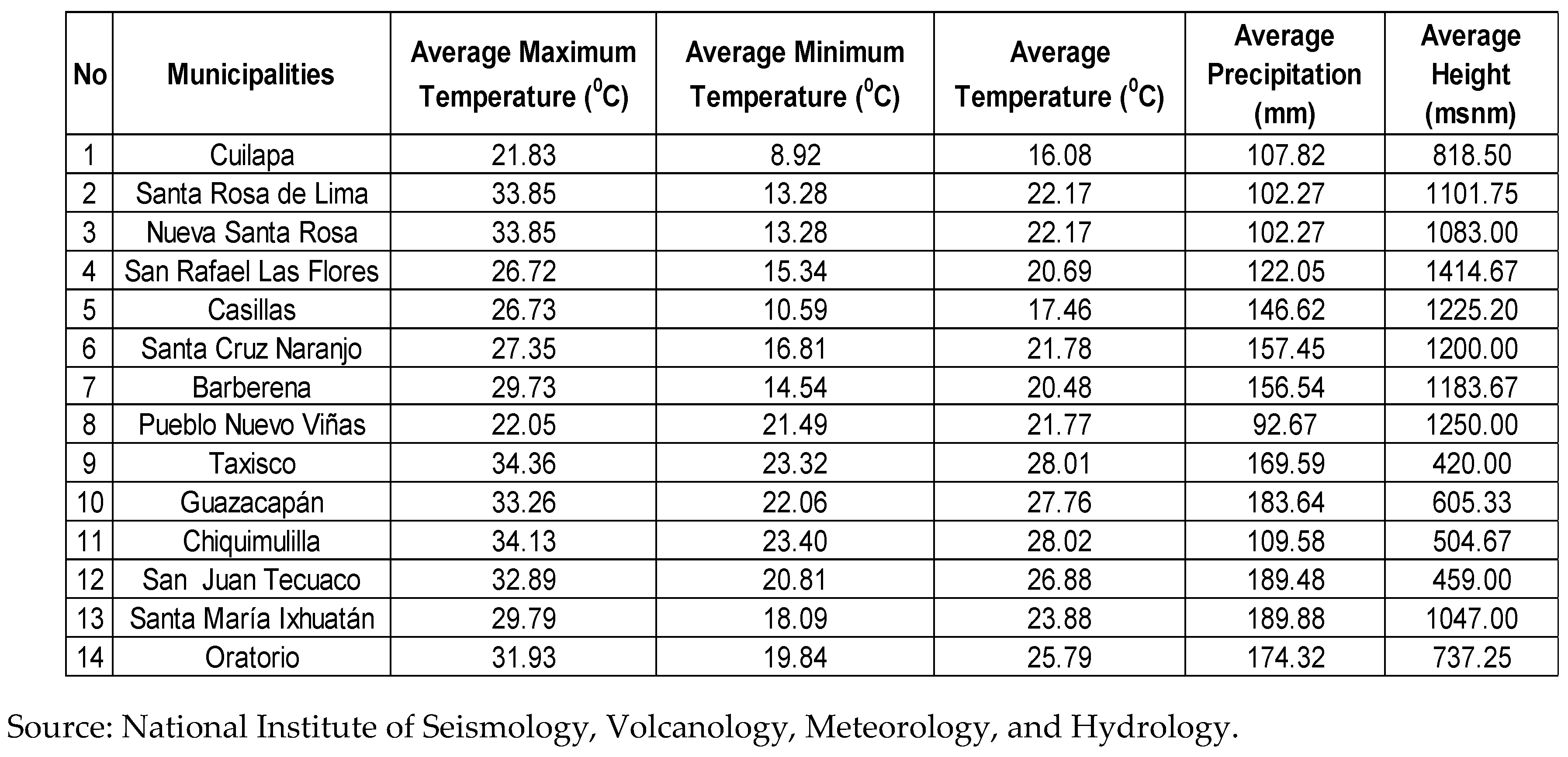

- Area of Study

- Household inspection, collection, and identification of Ae. albopictus larvae.

- Sample Selection

- Classification of the deposits

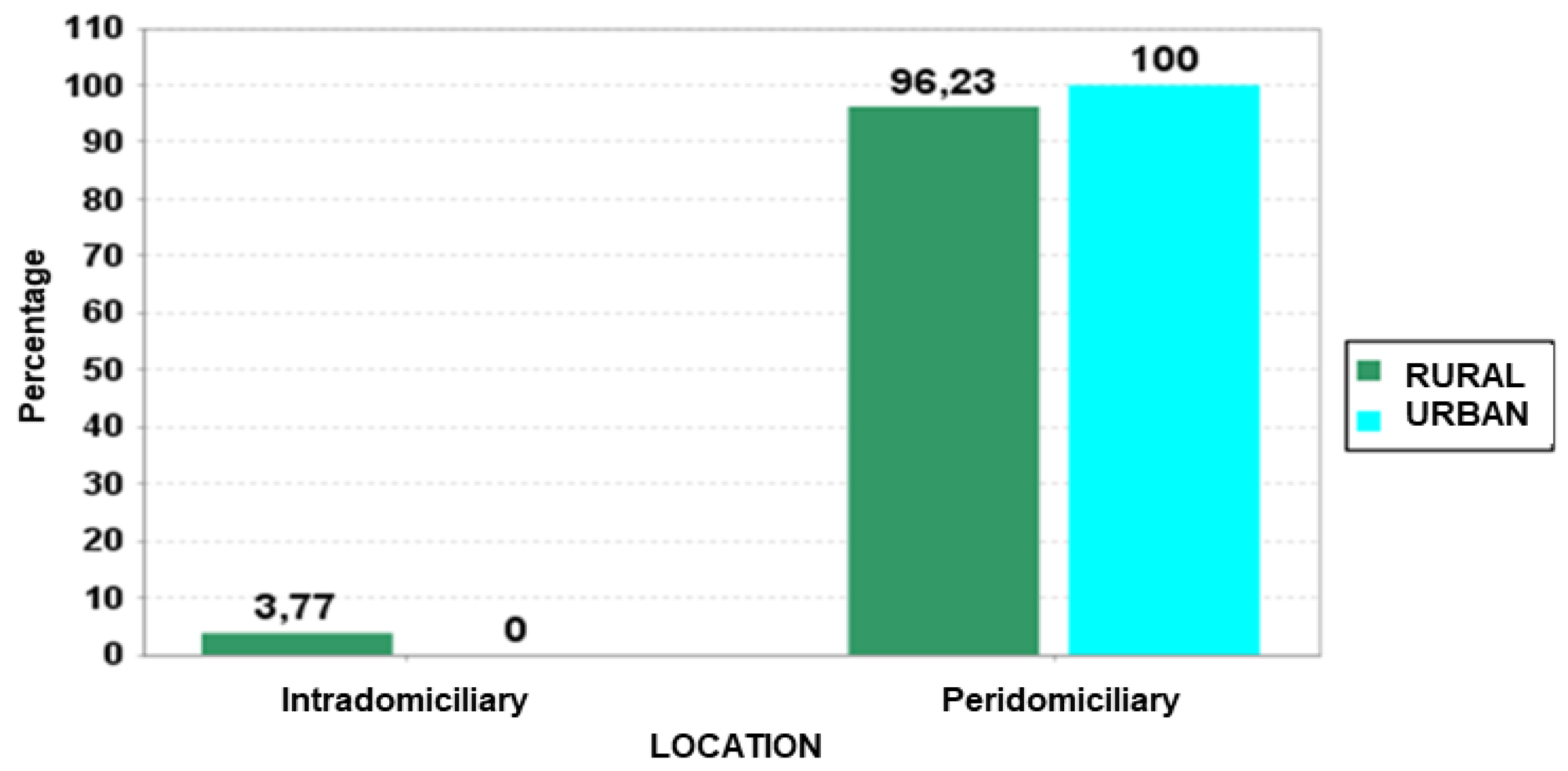

- Classification according to the area

- Data Analysis

- Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| CHIKV | Chikungunya virus |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

| YEV | Yellow fever virus |

| MOVCVEG | Operational Manual on Vector Surveillance and Control for Guatemala |

| LED | Departmental Entomology Laboratory |

| MSPAS | Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance of Guatemala |

| UAD | Useful Artificial Deposits |

| NUAD | Non-Useful Artificial Deposits |

| ND | Natural Deposits |

| DDRISS | Departmental Directorate of Integrated Health Services Networks of the Department of Santa Rosa. |

| DVCRS | Department of Surveillance and Control of Sanitary Regulations |

References

- Beleri, S.; Balatsos, G.; Tegos, N.; Papachristos, D.; Mouchtouri, V.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; et al. Winter survival of adults of two geographically distant populations of Aedes albopictus in a microclimatic environment of Athens, Greece. Acta Trop. [Internet] 2023 [cited on January 20 of 2025]; 240: 106847. [CrossRef]

- Ivanescu, L.M.; Bodale, I.; Grigore-Hristodorescu, S.; Martinescu, G.; Andronic, B.; Matiut, S.; Azoicai et al. The risk of emerging of dengue fever in Romania, in the context of global warming. Trop Med Infect Dis. [Internet] 2023 [cited on January 20 of 2025]; 8:65. [CrossRef]

- Canizales, C.C.; Carranza, J.C.; Vallejo, G.A.; Urrea, D.A. Distribution of Aedes albopictus in Ibagué: potential risk of arbovirosis outbreaks. Biomédica. [Internet] 2023 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 43:506-19. [CrossRef]

- Figuerola, J.; Martínez-de la Puente, J. Methodological procedures explain observed differences in the competence of European populations of Aedes albopictus for the transmission of Zika virus. Acta Trop. [Internet] 2023 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 237: 106724. [CrossRef]

- Kubacki, J.; Flacio, E.; Qi, W.; Guidi, V.; Tonolla, M.; Fraefel, C.; Viral metagenomic analysis of Aedes albopictus mosquitos from Southern Switzerland. Viruses. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 12:929. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B.A.; Wilson, A.E.; Zohdy, S. Aedes albopictus is a competent vector of Zika virus: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. [Internet] 2019 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 14(5): e0216794. [CrossRef]

- La Ruche, G.; Souarès, Y.; Armengaud, A.; Peloux-Petiot, F.; Delaunay, P.; Desprès, P.; et al. First two autochthonous dengue virus infections in metropolitan France. Eurosurveillance. [Internet] 2010 [cited on February 5 of 2025] ;15(39):19676. Available online: https://www.eurosurveillance.org.

- Lazzarini, L.; Barzon, L.; Foglia, F.; Manfrin, V.; Pacenti, M.; Pavan, G.; et al. First autochthonous dengue outbreak in Italy, August 2020. Eurosurveillance. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 25(36):2001606. [CrossRef]

- Monge, S.; García-Ortúzar, V.; Hernández, B.L.; Pérez, M.Á.L.; Delacour-Estrella, S.; Sánchez-Seco, M.P.; et al. Characterization of the first outbreak of autochthonous dengue in Spain (August-September 2018). Acta Trop. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 205:105402. [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.R.; Philip, L. Ecology of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in the Americas and disease transmission. Biomédica. [Internet] 2015 [cited on February 5, 2025]; 35(2):177-185. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rejon, J.E.; Navarro, J.C.; Cigarroa-Toledo, N.; Baak-Baak, C.M. An Updated Review of the Invasive Aedes albopictus in the Americas; Geographical Distribution, Host Feeding Patterns, Arbovirus Infection, and the Potential for Vertical Transmission of Dengue Virus. Insects. [Internet] 2021 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 12(11):967. /. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-de-Lima, V.H.; dos Santos Andrade, P.; Thomazelli, L.M.; Marrelli, M.T.; Urbinatti, P.R.; de Sá Almeida, R.M.M.; et al. Silent circulation of dengue virus in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) resulting from natural vertical transmission. Sci Rep. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 10(1): 3855. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, J.; Ferreira de Mello, C.; Brisola, C.; Érico, A.; Toma, H.K.; Queiroz, A.; et al. Natural Infection and Vertical Transmission of Zika Virus in Sylvatic Mosquitoes Aedes albopictus and Haemagogus leucocelaenus from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. [Internet] 2021 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 6(2): 99. [CrossRef]

- Ogata, K. & Lopez, S.A. Discovery of Aedes albopictus in Guatemala. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. [Internet] 1996 [cited on February 5 of 2025];12(3 Pt 1):503-506. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8887235/.

- Lepe, M.; Dávila, M.; Canet, M.; López, Y.; Flores, E.; Dávila, A.; et al. Distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Guatemala. Ciencia, Tecnología y Salud [Internet] 2017 [cited on February 5 of 2025]; 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Köppen, W. Climate Classification. Meteo Navarra. [Internet] [cited on February 11 of 2025]. [CrossRef]

- Operational Manual for Surveillance and Entomological Control of Aedes aegypti vector of Dengue and Chikungunya in Guatemala. [Internet] 2015 [Cited on February 11 of 2025]. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/54945.

- González, R. Culícidos de Cuba (Diptera:Culicidae). La Habana: Editorial Científico Técnica; 2006. p. 184.

- Chapter 4. Processes in Surveillance and Vector Control. In: Manual de normas y procedimientos en vigilancia y lucha antivectorial. Ministry of Public Health: Calle 23, Esquina Plaza de la Revolución, La Habana, Cuba; 2012.

- Chapter 2. General. In: Manual de normas y procedimientos en vigilancia y lucha antivectorial. Ministry of Public Health: Calle 23, Esquina Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, Cuba; 2012.

- Gil; G.; Keller, A.; Sourou, A.; Mahouton, D.; Ossè, R.; Sovi, A. Distribution and Abundance of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Benin, West Africa. Trop Med Infect Dis. [Internet] 2023 [cited on February 11 of 2025]; 8(9): 439. [CrossRef]

- Monroy, C.; Yuichiro, T.; Rodas, A.; Mejía, M.; Pichilla, R.; Mauricio, H. Distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidad) in Guatemala, follow-up to a 1995 colonization. Revista Científica. [Internet] 1999 [cited on February 15 of 2025]; 12(1), 29-32. Available online: https://rcientifica.usac.edu.gt/index.php/revista/article/view/346/489.

- SIGSA Web, Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance of the Republic of Guatemala. [Internet], Guatemala City [Cited on February 11 of 2025]. Available online: https://swsantarosa.mspas.gob.gt.

- Pérez, M.; Mendizábal, M.E.; Peraza, I.; Molina, R.E.; Marquetti, M.C. Spatial and temporal distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera:Culicidae) breeding sites in Havana, Cuba. Rev Cubana Med Trop. [Internet] 2014 [Cited on February 15 of 2025]; 66(2):252-262. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mtr/v66n2/mtr10214.pdf.

- Juliano, S.A.; O'Meara, G.F.; Morrill, J.R.; Cutwa, M.M. Desiccation and thermal tolerance of eggs and the coexistence of competing mosquitoes. Oecología [Internet] 2002 [cited on February 15 of 2025]; 130 (3):458–469. [CrossRef]

- Valdés, V.; Marquetti, M.C.; Pérez, K.; González, R.; Sánchez, L. Spatial distribution of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding sites in Boyeros, Havana City, Cuba. Rev Biomed. [Internet] 2009 [Cited on February 15 of 2025]; 20:72-80. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6061249.

- Carvajal, J.J.; Moncada, L.I.; Rodríguez, M.H.; Pérez, L.P.; Olano, V.A. Preliminary characterization of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse, 1894) (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding sites in the municipality of Leticia, Amazonas, Colombia. Biomédica [Internet] 2009 [cited on February 15, 2025]; 29(3). [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Canamejoy, K.; Carolina, A. First evidence of Aedes albopictus in the department of Putumayo, Colombia. MEDUNAB [Internet] 2018 [Cited on February 18 of 2025];21(1):10-15. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.A.; Diéguez, L.; Borge de Prada, M.; Vásquez, Y.E.; Alarcón-Elbal, P. Mª. Breeding sites of Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) in the domestic environment in Jarabacoa, Dominican Republic. Chilean Journal of Entomology. [Internet] 2019 [Cited on February 18 of 2025];45 (3): 403-410. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.A.; Kamgang, B.; Lenga, A.; Wondji, C.H.S. Larval ecology and infestation indices of two major arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae), in Brazzaville, the capital city of the Republic of Congo. Parasites & Vectors. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 13(1):492. [CrossRef]

- Tedjou, A.N.; Kamgang, B.; Yougang, A.P.; Wilson-Bahun, T.A.; Njiokou, F.; Wondji, C.H.S. Patterns of Ecological Adaptation of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus and Stegomyia Indices Highlight the Potential Risk of Arbovirus Transmission in Yaoundé, the Capital City of Cameroon. Pathogens. [Internet] 2020 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 9(6): 491. [CrossRef]

- Dalpadado, R.; Amarasinghe, D.; Gunathilaka, N.; Ariyaratne, N. Bionomic aspects of dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus at domestic settings in urban, suburban and rural areas in Gampaha District, Western Province of Sri Lanka. Parasites & Vectors. [Internet] 2022 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 15:148. [CrossRef]

- Obame-Nkoghe, J.; Roiz, D.; Ngangue, M.F.; Costantini, C.; Nil Rahola, N., Jiolle, D.; et al. Towards the invasion of wild and rural forested areas in Gabon (Central Africa) by the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus: Potential risks from the one health perspective. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. [Internet] 2023 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 17(8): E0011501. [CrossRef]

- Marquetti, M.C.; Bisset, J.; Leyva, M.; García, A.; Rodríguez, M. Seasonal and temporal behavior of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Havana, Cuba. Rev Cubana Med Trop. [Internet] 2008 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 60:62-7. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mtr/v60n1/mtr09108.pdf.

- De Lima-Tamara, T.N.; Honório, N.A.; Lourenco-de-Oliveira, R. Frequency and spatial distribution of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Díptera, Culicidae) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública. [Internet] 2006 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 22: 2079-84. [CrossRef]

- Ablio, A.P.; Abudasse, G.; Luciano, J.; Kampango, A.; Candrinho, B.; Luciano, J. Distribution and breeding sites of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in 32 urban/peri urban districts of Mozambique: implication for assessing the risk of arbovirus outbreaks. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. [Internet] 2018 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 12(9): E0006692. [CrossRef]

- Egida, B.R.; Coulibalyb, M.; Dadziec, S.K.; Kamgangd, B.; McCalla, P.J.; Seddae, L.; et al. Review of the ecology and behaviour of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Western Africa and implications for vector control. CRPVBD. [Internet] 2022 [cited on February 18 of 2025]; 2, 100074. [CrossRef]

| Municipalities | Absolute frequency |

Relative Frequency (%) |

Sector* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban (%) |

Rural (%) |

|||

| Santa Rosa de Lima | 11 | 16,42 | 18 | 82(2)** |

| Chiquimulilla | 10 | 14,93 | 35 | 65(7) |

| Casillas | 9 | 13,43 | 31 | 69(6) |

| San Rafael de Flores | 8 | 11,94 | 29 | 71(4) |

| San Juan de Tecuaco | 6 | 8,96 | 30 | 70(5) |

| Guazacapán | 5 | 7,46 | 65 | 35(9) |

| Oratorio | 5 | 7,46 | 40 | 60(8) |

| Barberena | 4 | 5,97 | 81 | 19(10) |

| Nueva Santa Rosa | 3 | 4,48 | 37 | 63(8) |

| Taxisco | 3 | 4,48 | 31 | 69(6) |

| Cuilapa | 2 | 2,99 | 95 | 5(11) |

| Santa María de Ixhuatán | 1 | 1,49 | 19 | 81(3) |

| Pueblo Nuevo de Viña | 0 | 0,00 | 15 | 85(1) |

| Santa Cruz Naranjo | 0 | 0,00 | 35 | 65(7) |

| Total | 67 | 100,00 | ||

| Municipality | Samples collected during the dry season (Nov-Apr.) |

Sampled collected during the rainy season (May- Oct.) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Rosa de Lima | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Chiquimulilla | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Casillas | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| San Rafael de Flores | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| San Juan de Tecuaco | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Guazacapán | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Oratorio | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Barberena | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Nueva Santa Rosa | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Taxisco | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Cuilapa | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Santa María de Ixhuatán | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 46 | 67 |

| Deposits | Rainy period (Nov- Apr.) |

Dry season (May- Oct.) |

Type of deposit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tires | 14 | 9 | 23DANU |

| Barrels | 9 | 3 | 12DAU |

| Cans | 5 | 6 | 11DANU |

| Bottles | 7 | 0 | 7DANU |

| Pila | 4 | 0 | 4DAU |

| Coconut shell | 3 | 1 | 4DN |

| Basin | 3 | 0 | 3DAU |

| Three hole | 1 | 0 | 1DN |

| Vase | 0 | 1 | 1DAU |

| Tank | 0 | 1 | 1DAU |

| Total | 46 | 21 | 67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).