1. Introduction

Universities are influential actors and change agents in society [

1]. The role of higher education institutions in addressing global sustainability challenges has garnered increasing attention from both scientific and policy communities [

2]. Higher education institutions (HEI) have a key role to play in upskilling and reskilling for adult learners, focusing on green and digital transitions and collaboration between HEIs, industry and policymakers to develop offerings [

3], p.5. Several mechanisms for enhancing upskilling or reskilling in higher education have been described such as setting system-wide strategies, attracting and supporting learners, securing industry and employer engagement [

3], p.7. In this paper we address one of the mechanisms that builds on conscious transformative capacity building through tension situations that may be achieved with learning practice development and application in HEIs. Creating a common interdisciplinary sustainability courses in HEIs is a widely used measure to immerse all students in sustainability education [

4].

However, we suggest in our paper a capacity building opportunity for sustainability goals. We suggest a capacity building opportunity from engaging students together with the course facilitators and external stakeholders into the co-development process of sustainability related educational opportunities that universities offer, e.g. the micro-credential courses. The dynamic capacity building concept in the center of this paper outreaches the United Nations sustainability goals SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 11 (sustainable cities) and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) in communities. Capacities are dynamic states that need to be jointly built and enacted to keep them functional.

The innovation proposed by this paper is involving students in the key development role of codesigning the micro-credential course to build the sustainability capacity of the university and the learners. The research question of this paper was: How the co-designing of the micro-credential on circular bioeconomy course together with students enabled them to learn the sustainability competences from the tensions that this capacity building intervention offered, and thus build the sustainability capacities for the university?

We base our paper on the transformational model of capacity building that is described below, which we used for the course development and formatively for evaluating it. The concept of the capacity [

5,

6] and the concept of the sustainability competences [

7] were central for the course programme design. We posited that the sustainability competences should be developed in a way that contributes to the overall sustainability capacity that the university encapsulates. We asserted that through an interdisciplinary learning experiment of co-designing the micro-credential course of circular bioeconomy together with students the transformational capacity-building, could happen. Transformation [

8] is necessary in a dynamic environment of the universities situated in the wider societal settings to develop mutuality so that they could act responsively. Transformation in social ecosystems is related to specific tensions and critical reflections [

9,

10]. Different tensions may occur with educational innovation development and should be governed with the longer vision in mind [

11]. Transformative change means that change is pervasive and intentional, influences the institutional culture and impacts the members of the organisation in terms of how they view themselves and their practices [

12].

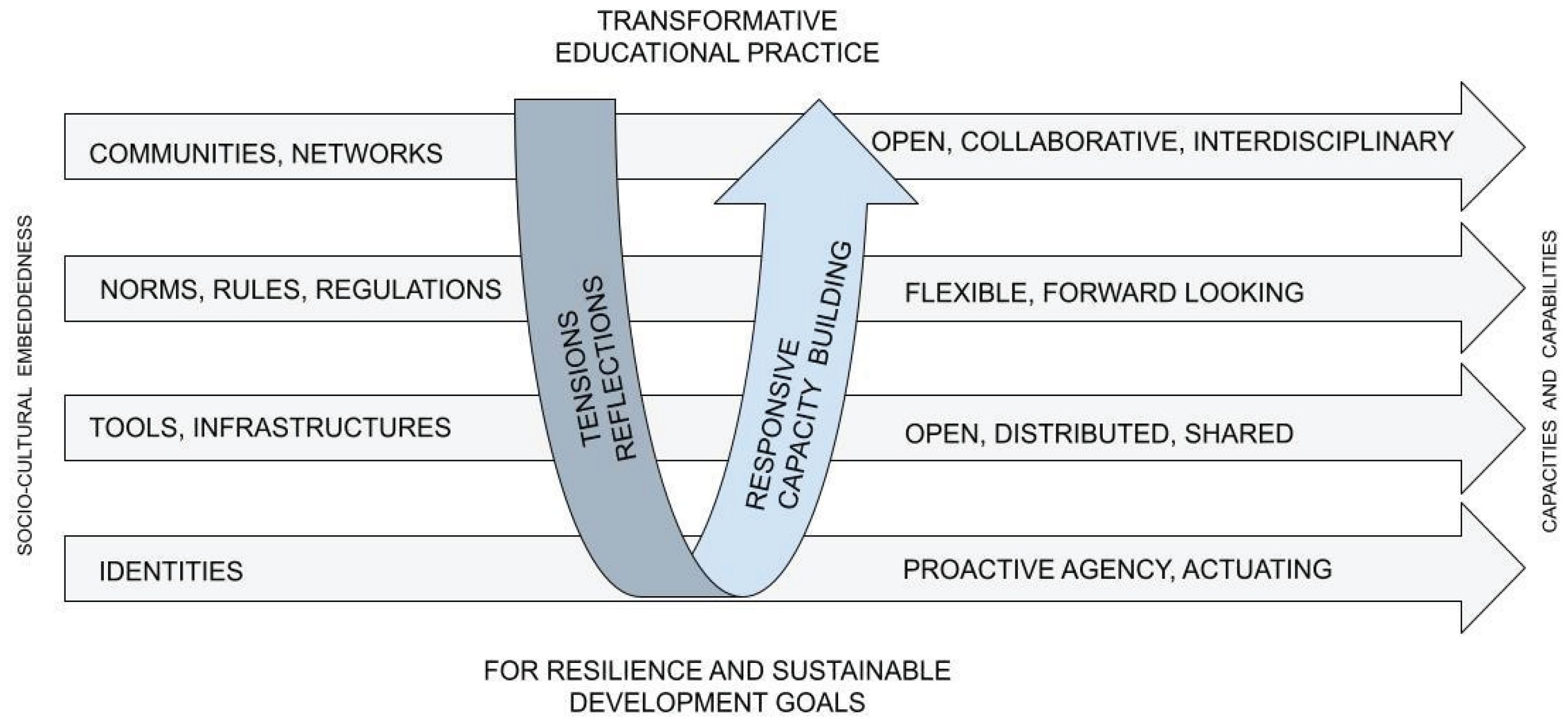

The transformational model of capacity building that we developed [

10] and advanced for this paper provides a framework that HEIs should consider to reach sustainable development goals at multiple levels when implementing educational practices (see

Figure 1). The model builds on the socio-cultural aspects of transformation in which specific tensions may arise when new learning practice is applied. For supporting the cross-university-society capacity for sustainable development through courses the universities require to make certain transformations. Such tensions must be holistically balanced to build capacity for acting for resilience and sustainable development goals at the university and beyond. There is the need that the academics in teaching, and the external stakeholders would be more ready for open, interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches of learning and joint problem solving for sustainability goals. The open and tailored to societal needs learning opportunities require from the university different institutional approach, where norms and regulations to the courses are more flexible. For example, the flexibility in learning environments, using external from the university contexts and resources for learning, flexible timing of learning, and shortened size of learning periods such as micro-credential based learning paths are approaches that support capacity building readiness. The changes must also take place in considering how the academics, the students and the external stakeholders see their roles and responsibilities in the learning activities that focus on sustainability problem solving. Open and complex problem-solving situations create the need to have competences that sustainability competencies framework comprises.

The following aspects are important to describe transformations that coincide with new learning practices implementation for pursuing the sustainable development goals:

The community and network aspect of transformation, stressed by many authors [

13,

14], the interpersonal capabilities promoting openness and interdisciplinarity in collaborations among academics, students and stakeholders external to the university within capacity building contexts so that alliances and partnerships could be developed, and shared values could be grounded [

15] and sustained for future collaborations;

The norms, regulations and rules aspect of transformation [

5,

14,

16] the capability of being forward looking and flexible in maintaining and sustaining innovative changes that require balancing between centralization and control intents for executing or implementing a certain standard, while nourishing new specialisation and differentiation opportunities within the change to create future innovation niches;

The tools and infrastructures aspect of transformation capitalises on the capability to generate development results together within cross-university and beyond-university social ecosystems by developing storing, maintaining and sharing resources, infrastructures [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and creating interoperable distributed resources [

22];

The professional identity development aspect of transformation advances the capability of students and academics to develop a proactive agency as a strategic intent to act, actuate and adopt situations deliberately, while consciously self-reflecting, adapting and configuring themselves and developing their identities as they confront dramatic shocks, going through collective and personal discovery [

5,

8,

9,

10,

15,

23];

The transformation goal towards sustainable development should pervasively guide the transformations that emerge in communities, at regulative and infrastructural spaces, and with professional identities [

14,

24,

25].

In the center of this paper is the design and evaluation of an educational intervention with students which we introduce in this case study as a transformational tool for capacity building for sustainability goals. The intervention had many layers. The students were invited to take part of the problem-solving course LIFE in Tallinn University

, that enables students to solve various problems from life. We used LIFE course as a potential carrier of transformations. In our LIFE course we engaged the students into the process of codesigning the micro-credential course according to the European approach [

26,

27]. The topic of the codesigned microcredential course was circular bioeconomy. The theoretical background for the microcredential course development was based on the regional roadmapping methodology for the circular bio-economy, developed as a framework in 2022-2023 in Estonia [

28]. The roadmapping methodology invites various organisations (e.g. county development centres, businesses, local governments and their unions, community initiatives) to map their common potential for circular bioeconomy and jointly developing the dynamic roadmap for the region. The students had to engage with societal stakeholders (potential learners) to develop the codesigned microcredential course according to their needs. The framework for sustainability competences, called the GreeComp [

7] was used as one of the frames to define the learning outcomes of the students at the learning practice. The learning process was intentionally student-driven, with the authors assuming facilitating roles.

The goal to codesign the microcredential course for the university on circular bioeconomy roadmapping topic was highly interdisciplinary, and required students to combine both social science and science knowledge and various competences. The learning practice we describe in this paper provided many opportunities for tensions to emerge and transformations to happen that we describe in this paper through students’ perspectives. We intend to demonstrate with this paper how the capacity building model to build sustainability for the university worked in practice from the students’ perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

In the methodology section, we first describe the course design methodology.

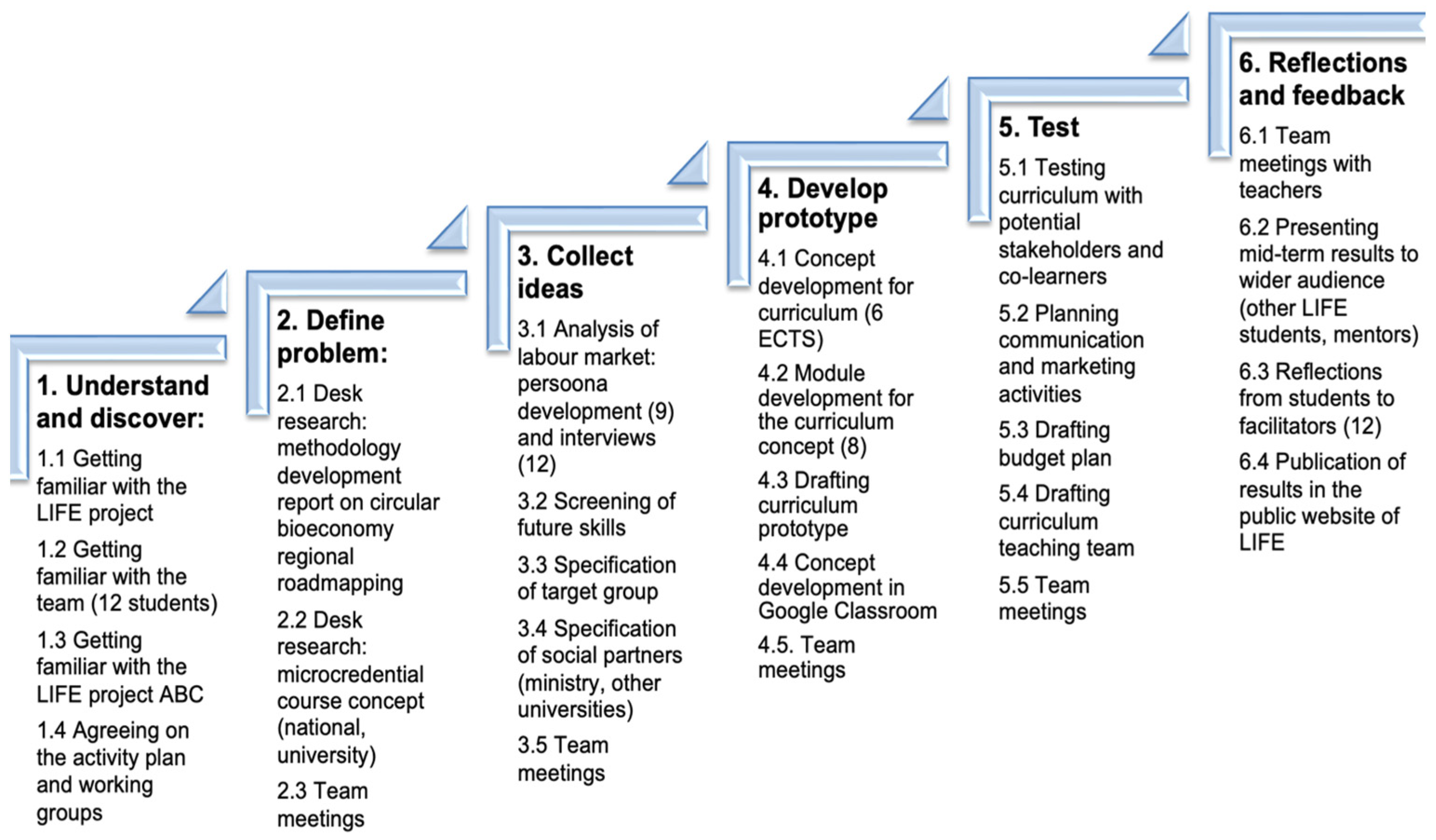

Figure 2 summarises all phases of the LIFE course, presenting it as an interactive tool for experimenting with transformation through the learning process (as described above).

Students were invited to participate in the LIFE project titled "Circular Bioeconomy – Development of a Micro-Degree Programme" [

29]. Interested students were required to submit motivation letters. The course was launched through the LIFE matchmaking system, forming an interdisciplinary student group of 12 participants from bachelor's and master's programmes in psychology, environmental management, molecular biochemistry and ecology, administration and business, andragogy, sociology, organisational management, and contemporary media. Working within such a diverse group presented both challenges and opportunities for creating a shared understanding of goals and deepening knowledge in the field.

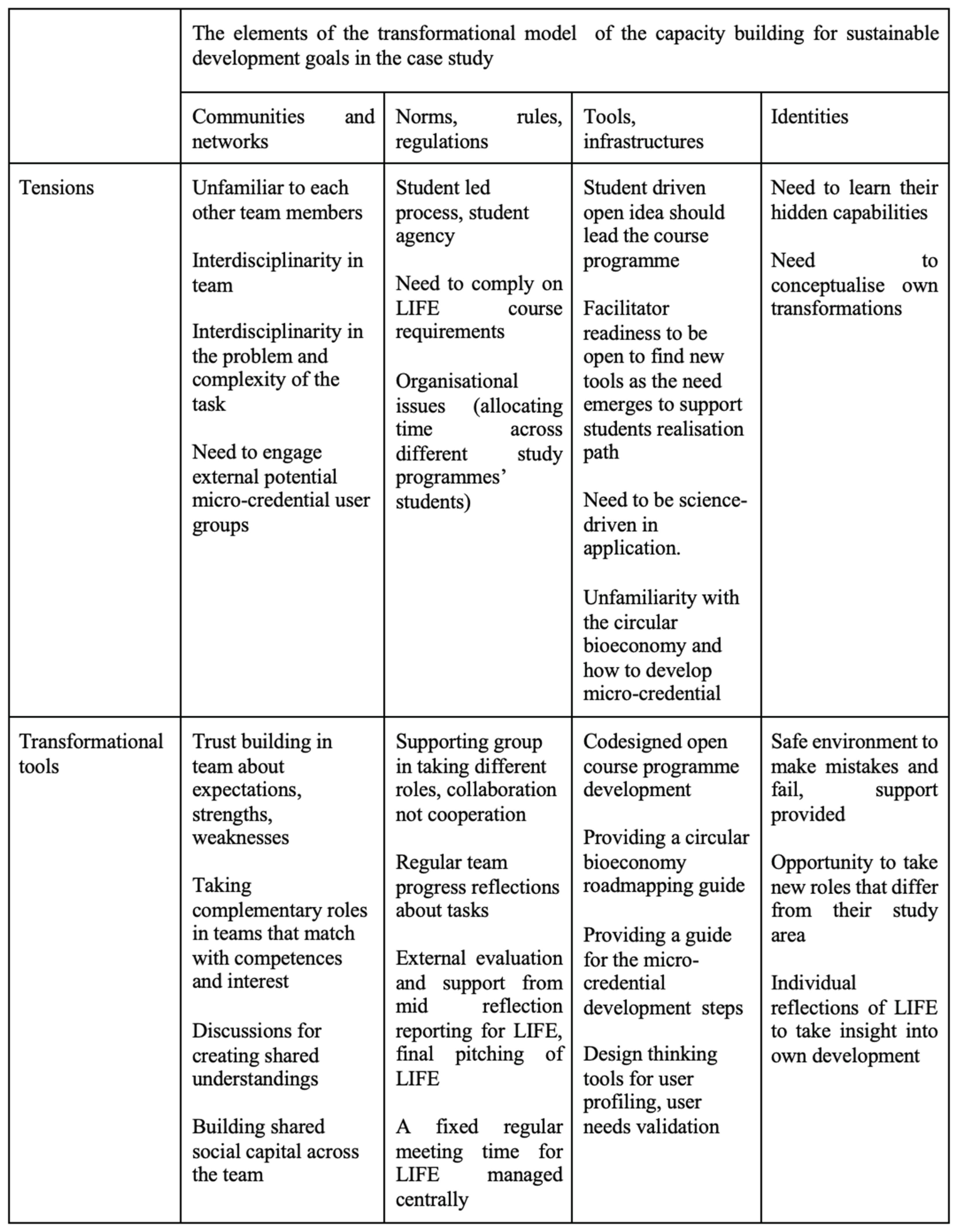

We based our application case of the transformational model of capacity building for sustainable development goals, aiming to support students in their sustainable development journey.

Table 1 below highlights some of the main tensions and the transformational tools we applied.

The structure of the LIFE course programme was not fully predefined, allowing it to remain open and student-led. Facilitators were prepared to introduce various approaches and steps as needed. To ensure meaningful student involvement in the development process, we agreed in advance on the following key aspects: Firstly, we adopted a co-design approach, incorporating elements of the design thinking process, such as persona analysis and beneficiary pathway roadmaps. Secondly, the Circular Bioeconomy Report [

28] served as a foundational resource for designing the course, outlining key theoretical and practical steps that the micro-credential course should include. Additionally, we adapted an approach developed for the Modernising ICT Education for Harvesting Innovation project [

30]. The task focus was placed on micro-credential course development, an emerging field with limited established practices for addressing stakeholder needs. European Union (EU) and OECD sources provided guidelines and helped frame the complex challenges involved. Various target groups needed to be identified and engaged throughout the process, including:

Learners (professionals, students, individuals with disabilities, and others);

Educational institutions (higher education, vocational training, and representative bodies);

National and regional authorities (ministries, municipalities, agencies); and

Employers, social partners, and civil society organizations [

31].

The LIFE course was conducted over a full semester. Students met biweekly for regular sessions and organised ad hoc meetings for group work and specific tasks. Reflection sessions took place within the co-design team, allowing for continuous feedback and adaptation. In the final stage, students were asked to write self-reflections, providing insights into their personal learning experiences and offering feedback to both the LIFE team and university facilitators.

The course was formatively evaluated using student motivation letters, self-reflections, and facilitator diaries. As a final deliverable, students submitted the LIFE project portfolio, showcasing their results and confirming their contributions. We used in this paper these anonymous reflections to look back at how the students conceptualised transformative learning in this course. The aspects of tensions and learning were marked in students’ reflections and related with the transformational capacity building model (see

Figure 1) elements.

3. Results

The results present the aspects of transformation experienced during the LIFE course. The students' reflections that identify their key learning perspectives during transformation were synthesised according to the transformational capacity building model elements (see

Figure 1). We emphasise the tensions that arose and must be holistically balanced to build the students’ capacities for resilience and sustainable development. The results demonstrate the students views on how the transformation model of capacity building for sustainable development goals operated through rising tensions throughout the learning process. The following chapters highlight the perceived benefits and challenges for students, but address also university facilitation, and stakeholder engagement.

3.1. Responsive Capacity Building from the Community and Network Aspect of Transformation

The students’ self-reflections could be categorised according to the specified tensions and transformations related to learning group, community and network aspects.

Overcoming disciplinary differences for a common goal:

“Despite the fact that we were all different people, from different professions and completely different backgrounds, and that none of us was involved in any way in the circular economy, I think we achieved a good result.”

“It was interesting to see and experience the creation of something with so many different people from different backgrounds.”

Exploring teamwork and project complexity:

“The project taught me a lot about team dynamics, and I think the biggest challenge was how all the smaller activities contribute to the end result.”

"I had the opportunity to work with people from different backgrounds, which broadened my perspective on the need for collaboration, its different forms and gave me new ideas on how different disciplines can be brought together for sustainability.”

Understanding of stakeholder engagement:

“I work in local government and it is important to me that there is a common understanding at the local level of what circular bioeconomy means and how it can be developed step-by-step.”

“There is still quite a lot of resistance in society to the 'green transitions' because more sustainable and responsible behavior requires breaking old habits, but on the other hand, there is too little knowledge about how to achieve this more sustainable way of life.”

“I found this project particularly interesting because, through my work in local government, I understand that people need more support and guidance in changing their behavior. At the same time, local governments often lack the necessary knowledge to effectively guide them.”

Awareness rising and communication with external user groups:

“I realised how important it is for all parties involved to be aware of and understand the concept of the circular economy. Without this understanding, meaningful change cannot happen.”

“If the target audience is unaware of its need for this micro-credential, how can it recognise its value?”

The students' reflections emphasised team dynamics, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the complexities of working toward a shared goal in a diverse group. Learners presented the critical need for a shared understanding of the circular bioeconomy, noting that a lack of awareness hinders progress. The collaborative development of the micro-credential programme deepened their knowledge and allowed active participation in curriculum creation, showcasing the value of different perspectives and effective social capital building to bridge knowledge gaps.

3.2. Responsive Capacity Building from the Norms, Regulations and Rules Aspect of Transformation

The students’ self-reflections revealed the specified tensions and transformations related to norms, regulations and rules.

Encouraging student led process, creativity and ownership:

"We were given a great deal of freedom and allowed to design the programme ourselves. While this made the task more challenging, it also enabled us to develop our creativity and create something entirely new."

"In practice, all members took responsibility and contributed effectively. The main drawback was that it took us a long time to establish our direction and clarify individual responsibilities."

Challenges in role assignment and coordination:

"Unfortunately, our small group initially struggled to assign roles and responsibilities, which turned out to be a mistake. However, with guidance from the facilitator, we gained a clearer sense of direction."

"In practice, all members took responsibility and contributed effectively. The main drawback was that it took us a long time to establish our direction and clarify individual responsibilities."

“During the project, I learned that the larger the group, the harder it is to reach agreements. Meetings tend to be longer, and conflicts can arise when roles and expectations are not clearly defined.”

Communication gaps and leadership:

"In hindsight, it might have been beneficial for the team leaders of both groups to have regular (weekly) discussions on work progress and provide quick feedback, possibly with the supervisors."

"Additionally, it may be worth considering that the role of team leaders should focus solely on management, team coordination, and communication. Currently, the team leader's role is often split between content-related tasks and management, which negatively impacts overall leadership effectiveness."

“I understand that discussion and compromise are essential aspects of the course.”

Struggling with time limitations

“The biggest obstacle was time, but thanks to good teamwork we were able to complete a project that could be implemented by Tallinn University in the future.”

“Personally, I would have preferred the project to have been the only subject at the time it took place, and to have been held more frequently as lectures during the day.”

“The most challenging part of the project was probably balancing work, private and study commitments.”

The biggest challenge of the LIFE project was the overlap of meeting times with other lectures and seminars. And to be honest, it also gave me a sense of abandonment in between, that I just couldn't be in two places at once.

Students reported initial tensions stemming from the freedom to self-design the programme, leading to challenges in role assignment and reaching agreements in larger groups. This highlighted the importance of clearly defined roles and expectations to prevent conflicts and facilitate quicker decision-making in the LIFE project. Despite these hurdles, students valued the opportunity for creativity and ultimately succeeded through effective teamwork, even overcoming time constraints. The feedback reflected that even more structured university support for organization and leaderships could have encouraged progress.

3.3. Responsive Capacity Building from the Tools and Infrastructures Aspect of Transformation

The students’ self-reflections revealed the specified tensions and transformations related to tools and infrastructures.

Practical insights into the contents - course development:

“I believe the most important aspect is experiencing and participating in all phases of setting up a programme. In the future, if I create training courses or programmes myself, I will know how to tailor them to specific target audiences.”

“I have learned that not only is the content of the programme important, but also the delivery method, the target audience, and the pricing strategy.”

“In the context of the project as a whole, it was very interesting to see the skeleton of the programme development, the smaller tasks that make up the outline of one programme”

Practicing working tools and methods

“Planning and conducting interviews was an important experience, as was working with personas, which seems a simple and surprisingly effective way of working.”

“The most challenging part of the whole programme was the collection of the interviews in a temporal context, where I had to take into account my own work schedule and private life, as well as the schedule of the interviewees.”

“I had the experience of conducting an interview with an expert on a subject I was not familiar with. It developed my ability to approach things creatively.”

“The hardest part for the programme at the moment seems to be the preparation of the presentation and the portfolio, as the exam period is about to start and very few members of the project came to the last meeting.”

“It was difficult at first to get out of the theme of the roadmap. I would count as a victory the moment we added ESG and financing separately to the plan, because these two themes will determine the success of future circular bioeconomy ventures and projects”

I contributed to the creation of the learning material - a process that required a lot of thought and a clear vision of the situation so that learners could actually take something away from the course.

“My input was decent (I did most of the personas, conducted two interviews with both the municipality and the company, drafted the interview schedule, dealt with the sub-topic of target group and market needs, and added aspects of SWOT analysis and other bits and pieces).”

“I contributed to the creation of the learning material - a process that required a lot of thought and a clear vision of the situation so that learners could actually take something away from the course.”

Availability of external stakeholders

“When I was looking for partners, I realised that in reality very few people want to reply to my letters. Even though I briefly outlined in my appeal why this micro-credential is necessary. Later, one of the partners described that he himself did not understand this area, so he was not too keen to offer himself as a cooperation partner.”

“In the future, I would certainly do differently in the aspect that the target group needs to be defined as a matter of urgency and then we can think about what to do next. We were unclear for a long time in the group about the target group and there were arguments about it, which is why the work stalled at the beginning.”

Balancing facilitators’ support and individual initiative:

"It would have been nice to have had more time to meet with the group and discuss, even without the tutors. The time with the tutors felt a bit too limited."

“In the future, it would be reasonable to give more specific guidance to project participants as this would help to make faster decisions and start producing content more quickly. At the same time, I understand that discussion and compromise-building might also be part of the course.”

"I found the supervisors to be nice people and supportive in doing the work and at the same time not too overbearing.

“After some guidance from the instructor, we got a clearer sense of where someone should go.”

The tutors were excellent and I am so glad that this programme was not just a monotonous lecture. The tutors were very helpful and you could see that they were both genuinely very interested in this programme and in achieving its goal, which certainly motivated us all to try harder.

I would like to praise the tutors for always finding the time for us and for their expertise. We were given a “free hand” and were allowed to build the programme ourselves, which made the task more difficult, but at the same time we were able to develop our creativity and do something completely new ourselves. It was a worthwhile experience and it's great to have the LIFE programme in the curriculum.

Students found the LIFE course open and flexible and student driven norms and regulations appropriate for achieving the expected results of the current project — developing a prototype of the circular bioeconomy micro-credential programme. They appreciated the facilitators' support but recognized that their own initiative would be crucial for further success and this should more encouraged during the learning process. The design-based canvases as tools that capture design states and enable transformations during design phases enabled them to structure the findings. Key learnings included the comprehensive nature of programme development, encompassing not just content but also delivery methods, target groups, and pricing strategy. The co-designed open course and provided guides for circular bioeconomy road-mapping and micro-credential development were instrumental in helping students navigate this complex process.

3.4. Responsive Capacity Building from the Professional Identity Development Aspect of Transformation

The students’ self-reflections revealed the specified tensions and transformations related to professional identity development.

Student expectations and expanding perspectives:

"I joined the LIFE project of the circular bioeconomy micro-credential programme because I believe that promoting green thinking is essential for the future. The programme allowed me to gain an in-depth understanding of the concept of circular bioeconomy, helping me to gain new insights into the field in different contexts."

“My expectations were to gain knowledge on how to start researching something from scratch and to understand the work involved in preparing a microdegree.”

"I joined the LIFE project because I wanted to get experience in making a micro-credential curriculum. Moreover, circular bioeconomy is a topic that everyone should be familiar with. The most important thing for me is to see and participate in all the stages of setting up a programme."

"My personal expectations were related to the opportunity to learn the content of circular bioeconomy and to apply it in a practical project."

I would be quicker to take the initiative to manage the situation and at the same time try to bring in the best knowhow from all of them to achieve the best result.

Deepening knowledge and hands-on experience

I felt that I really learnt more about circular bioeconomy (because planning the course content requires a good overview of the topic). I would perhaps have liked a slightly more ambitious target setting for our group, as I think we could have covered all the modules in this time. At the same time, however, the project added a number of valuable topics such as legislation and funding opportunities to complement the content of the microcredit.

“I will certainly take with me the knowledge that is perhaps one step ahead of other Estonians on this topic. As I know a lot of people from the public sector in my circle, it is nice to discuss with them about the issues.”

I could have taken more time to study/understand the concept of circular bioeconomy in the beginning, could have looked at more foreign language links. As a team, I could have invested more time in testing and gathering feedback in order to better identify and respond to potential challenges at an early stage.

“During the project, I learned more about circular bioeconomy and gained a general understanding of what it takes to create a microcredential. I'm a bit surprised by the amount of work, investment, and effort required, which makes it clear why they are so expensive—and certainly, most are worth the money.”

“During the process, I learned that there is an important link between the waste streams from the blue economy and other bioeconomy sectors in order to raise the profile of the sector.”

“The creation of the framework for the micro-credential programme provided an excellent opportunity to take a deeper look into this topic. It gave me the opportunity not only to deepen my knowledge of circular bioeconomy but also to actively participate in the process of creating the curriculum, which was a new and exciting experience for me.”

“I explored the concept of the circular bioeconomy and how it could be better organised.”

Connecting learning to future career opportunities:

"During the process, I learnt that there is an important link between the waste streams from the blue economy and other bioeconomy sectors in order to raise the profile of the sector. As there are a lot of bio-resources in Estonia, the project gave me new ideas for future jobs."

"In the future, I may want to set up a training course or programme myself, in which case I know that I can use personas to target the training, and that it is not only the content of the training programme that is important, but also how, for whom and at what cost."

Call for practical implementation of the project:

Students' responses highlighted their motivations for joining the LIFE course, primarily to understand the green transition and the micro-credential course development process from inception. The course created a safe environment to learn through mistakes, allowing participants to get new knowledge and practices, explore new roles and apply their learning. This practical engagement, combined with opportunities for individual reflection, helped students grasp the links between different bioeconomy sectors, recognise the comprehensive effort required for programme development, and appreciate the value of diverse perspectives. The learning experience broadened their understanding of collaboration and inspired future career ideas.

4. Discussion

We address in the discussion part the transformations that occurred due to specific tensions that were created at different levels of the capacity building process.

We asserted in this paper that the universities should consciously offer certain key tensions during the course development, to trigger transformational changes among students as well as to support the transformational capacity building at the university level for sustainability goals:

Interdisciplinarity at teams, topics, solving complex problems;

Student led learning, student agency, students’ motivation-based engagement;

Bringing transformational tools to support general designing and problem solving approaches (e.g. canvases) and tools that help to translate scientific approaches to practical life;

Enabling to learn beyond your own discipline to discover the borders of professional identity.

The LIFE project on developing circular bioeconomy microcredential programme served as a learning experiment where students from diverse backgrounds engaged in the co-design process, highlighting key challenges and opportunities in interdisciplinary collaboration for sustainable development. The LIFE project demonstrated that through responsive capacity building and interdisciplinary learning, even a highly diverse group can navigate complex sustainability challenges and co-create meaningful, practical solutions. Future initiatives of the university should continue to leverage co-design approaches, interdisciplinary collaboration, and stakeholder engagement to foster sustainable transformation.

The reflections confirm that learning through experimentation is a challenging yet necessary process for achieving the expected goals. University facilitators considered the students' starting positions, including their existing knowledge and practices in the field, while also acknowledged their motivations for joining the LIFE team in this particular programme development. The key challenge of facilitators was balancing control, trust, and flexibility for students. Facilitators chose to grant students a degree of freedom while ensuring adherence to the LIFE format’s quality criteria. We found that despite of providing openness and student led practice, the clear mentorship can enhance the efficiency of the co-design process. An interdisciplinary team proved advantageous, as it enabled a better understanding of sectoral linkages and regulatory frameworks. Designing innovative educational programmes requires a holistic approach that considers content, delivery, target audience, and financial feasibility. University facilitators emphasised the importance of effective and open teamwork, noting that it took about a month for participants to become familiar with each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Establishing well-defined roles, clear expectations, and fluent communication was essential to preventing conflicts and managing time constraints effectively.

Transformational tools established at the university and facilitated by educators encouraged engagement with various stakeholders to identify a specific target group for the forthcoming micro-credential programme. These tools included persona development and mapping learner pathways throughout the learning curve, leading to the expected learning outcomes. Students participated in fieldwork by conducting interviews, which helped define knowledge and skill gaps while experimenting with preliminary ideas for the programme. Interviews were conducted with stakeholders from both the public and private sectors. The pre-defined content proposal for the programme was then validated and updated based on the insights gathered. Fieldwork, following desk research, was one of the most exciting parts of the co-design process. It fostered new perspectives, strengthened teamwork among students, and deepened collaboration with university facilitators. It was one of the most important turning points for the codesign process to ensure further clear steps towards completion of the learning practice. Based on students’ reflections they all benefited individually through personal efforts and responsibilities but especially through teamwork.

Effective capacity building in flexible tools and open infrastructures, enables cross-university and beyond-university ecosystems to collaborate, develop, and sustain shared resources. The LIFE project demonstrated how co-designing a micro-credential course required not only knowledge sharing but also the structured coordination, infrastructure accessibility, and efficient resource management. Ensuring clear role distribution, feedback loops, and balanced autonomy was crucial for generating meaningful development results.

The co-design process, involving an interdisciplinary team and stakeholders from both the public and private sectors, facilitated knowledge exchange and collaboration. It created opportunities for students and university teachers to learn from each other by sharing diverse perspectives, materials, and ideas. Both students and potential learners identified a lack of awareness about the circular bioeconomy and sustainable practices as a key barrier, emphasising the need for greater support from local governments and institutions. The co-designed micro-credential programme was recognised as a valuable training tool by both students and its final beneficiaries. Fostering behavioral change requires both knowledge and motivation. Responsive capacity building — aligned with norms, regulations, and institutional frameworks — is essential for enabling flexibility and forward-thinking approaches throughout the co-design process. The LIFE project illustrated how students engaged with governance structures to balance innovation with institutional requirements, ensuring sustainability while adapting to emerging challenges. A key tension identified was the need to balance centralisation and control with the flexibility required for sustaining innovation. The LIFE project fostered identity development by encouraging students and facilitators to take proactive agency, allowing them to act, reflect, and adapt in shaping real-world sustainability solutions. Engaging in the co-design process empowered participants to configure learning experiences, apply interdisciplinary knowledge, and envision future roles in sustainability-driven fields.

The reflections highlight various practical challenges that could be avoided in future projects. University support was perceived as well-organised and provided as a grant to help students explore the process. From the university facilitators’ perspective, both physical and virtual working tools were promoted and applied in preparing pilot learning materials for specific curriculum modules. These skills and additional knowledge were imparted by mentors. To give students a stronger starting position, group formation and overall process design were facilitated by the university, which emerged as a key factor in the project's success. Regular check-ins between team leaders, members, and facilitators helped maintain progress. Facilitators should provide guidance without micromanagement, allowing students to develop autonomy while ensuring accountability. Universities should also foster cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral learning by investing in digital and physical infrastructure, enhancing the long-term sustainability of both individuals and organisations.

Despite the limited time frame and the challenge of working with new people, most students participating in the four-month co-design process were satisfied and even benefited more than expected. University facilitators also faced difficulties in maintaining group synergy and ensuring tasks were completed on time but ultimately found effective solutions. This required flexibility and an understanding of students’ personal commitments, balancing studies and work. For future experiments, it is essential to strengthen students’ sense of ownership and responsibility in sustainability efforts. Practical engagement in sustainability projects enables students jointly with the external stakeholders to translate learning into real-world applications and job opportunities.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we applied a transformational capacity building model for course development and demonstrated how it supported students to achieve sustainability competences and the universities to develop its capacities as the sustainability agent. While each student-led sustainability driven capacity building project may generate small scale solutions, long-term success of universities to act as a driver for sustainability in the society depends on institutional commitment and university leadership, and the approaches how universities build the dynamic capacity with the society through its activities. Our model suggests it is important to follow openness and sharedness in the tools and infrastructures to promote cross-university and society interdisciplinary collaboration across the stakeholders to be more relevant for their needs; flexibility in applying norms for providing learning practices to help universities to be more agile in grasping the opportunities to solve problems in collaboration with students, researchers and the external stakeholders; and promoting in course design and assessment requirements student-driven proactive agency and responsibility in actuating the new sustainable states in the society. Overall this case study demonstrated how the university can act as a proactive agent, promoting educational practices for capacity building that drive long-term sustainable transformations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: K.M. and K.P; formal analysis, K.M.; resources, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.P.; visualization, K.M., K.P.; funding acquisition, K.M., K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was done in the PROJECT SustainERA NUMBER 101186958 funded by the European Union HORIZON-WIDERA-2023-TALENTS-01.” Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

AI support - SCOPUS AI is very minor in searching for materials and integrating to the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hyytinen, H.; Laakso, S.; Pietikäinen, J.; Ratvio. R.; Ruippo, L.; Tuononen, T.; Vainio, A. Perceived interest in learning sustainability competences among higher education students. International Journal of Sustainability of Higher Education 2023, Vol. 24, No 9, pp. 118-137. [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Barbosa Franco, J; Franco Junior, A; Battistelle, R.A.G; Bezerra, B.S. Dynamic Capabilities: Unveiling Key Resources for Environmental Sustainability and Economic Sustainability, and Corporate Social Responsibility towards Sustainable Development Goals 2024, Resources, 13(2), 22. [CrossRef]

- Promoting green and digital innovation: the role of upskilling and reskilling in higher education. OECD Education Policy Perspectives. Directorate for Education and Skills. 2024, No 103. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/promoting-green-and-digital-innovation_986b39b4/feb029df-en.pdf (Accessed: 30 June 2025).

- Aktas, C. B.; Whelan, R.; Stoffer, H.; Todd, E.; Kern, C. L. Developing a university-wide course on sustainability: A critical evaluation of planning and implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 106, pp. 216-221. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. The concept of capacity. European Centre for Development Policy Management 2006, 1(19), pp. 826-840.

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competences in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science 2011, 6(2), pp. 203-218.

- Bianchi, G.; Pisiotis, U.; Cabrera, M.; editors: Punie, Y.; Bacigalupo, M. GreenComp. The European sustainability competence framework. European Commission. JRC Science for Policy Report. 2022. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC128040 (Accessed: 30 June 2025).

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practise. New directions for adult and continuing education, 1997 (74), pp. 5-12.

- Gillespie, A. The social basis of self-reflection. In The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural Psychology, Valsiner J.; Rosa A. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY US, 2007, pp. 678-691.

- Pata, K.; Ümarik, M.; Jõgi, L. Paths of Professional Transformation in the Context of a Changing Teaching Culture at University. In Teaching and learning at the university. Practices and transformations, (Eds. Jõgi et al.) Cambridge Scholars Publishers: 2020, pp. 151-165).

- Wang, L; Liu, H. Comprehensive evaluation of regional resources and environmental carrying capacity using a PS-DR-DP theoretical model. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2019, 29(3), pp. 363-376. [CrossRef]

- Holley, K. A. Interdisciplinary Strategies as Transformative Change in Higher Education. Innovative Higher Education 2009, 34, pp. 331-344. [CrossRef]

- Boreham, N. A theory of collective competence: challenging the neo-liberal individualisation of performance at work. British Journal of Educational Studies 2004, 52(1), pp. 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community resilience: toward an integrated approach. Society & natural resources 2013, 26(1), pp. 5-20. [CrossRef]

- Bollig, M. Resilience — Analytical Tool, Bridging Concept or Development Goal? Anthropological Perspectives on the Use of a Border Object. Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie 2014, 139(2), pp. 253–279.

- Scott, R. Institutions and Organisations: Ideas and Interests, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, 2008.

- Eccles, K.; Schroeder, R.; Meyer, E. T.; Kertcher, Z.; Barjak, F.; Huesing, T.; Robinson, S. The future of e-research infrastructures. In Proceedings of NCeSS International Conference on e-Social Science, Cologne, 24-26 June 2009.

- Baldry, C.; Barnes, A. The open-plan academy: Space, control and the undermining of professional identity. Work, Employment and Society 2012, 26(2): pp. 228–245. [CrossRef]

- Odling-Smee F.J.; Laland K.N.; Feldman M.W. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2003.

- Sannino, A.; Engeström, Y. Cultural-historical activity theory: founding insights and new challenges, Cultural-Historical Psychologyn 2018, 14 (3), pp. 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Nordbäck, E.; Hakonen, M.; Tienari, J. Academic identities and sense of place: A collaborative autoethnography in the neoliberal university. Management Learning 2021, 53(3). [CrossRef]

- Bos, N.; Zimmerman, A.; Olson, J.; Yew, J.; Yerkie, J.; Dahl, E.; Olson, G. From shared databases to communities of practice: A taxonomy of collaboratories. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2007, 12(2), pp. 652-672.

- Emirbayer, M.; Mische, A. What is agency? American Journal of Sociology 1998, 103(4), pp. 962-1023.

- Maclean, K.; Cuthill, M.; Ross, H. Six attributes of social resilience. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2014, 57(1), pp. 144-156. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S. Skilling for sustainable futures: To SDG 8 and beyond. TESF Background Paper Series 2020. Bristol, TESF. Available online: https://tesf.network/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/TESF-BACKGROUND-PAPER-Skilling-for-Sustainable-Futures-to-SDG-8-and-beyond.pdf (Accessed 30 June 2025).

- Proposal for a COUNCIL RECOMMENDATION on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability. Brussels, 10.12.2021 COM(2021) 770 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52021DC0770 (Accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Carțiș, A.; Leoste, J.; Iucu, R.; Kikkas, K.; Tammemäe, K.; Männik, K. Conceptualising Micro-Credentials in the Higher Education Research Landscape. A Literature Review. In Proceedings of Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies: SLERD 2022: 7th International Conference on Smart Learning Ecosystem and Regional Development, Bucharest, Romania, 5-6 July 2022. Springer, pp. 191−203. [CrossRef]

- Pikner, T.; Pata, K.; Teder, L.; Plaan, J.; Kapanen, G.; Tuisk, T., Arro, G. Methodological framework for developing a regional circular bioeconomy roadmap, 2023. Tallinn University in cooperation with the Ministry of Regional Affairs and Agriculture. Tallinn, 44 p. Available online: https://www.ester.ee/record=b5718832 (Accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ringbiomajandus - mikrokraadiprogrammi arendamine (2023/2024). Available online: https://elu.tlu.ee/et/projektid/ringbiomajandus-mikrokraadiprogrammi-arendamine (Accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Project ICT-INOV “Modernising ICT Education for Harvesting Innovation”. Available online http://ictinov-project.eu (Accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Public policies for effective micro-credential learning. OECD Education Policy Perspectives 2023. 14 December. Available online https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/public-policies-for-effective-micro-credential-learning_a41f148b-en.html (Accessed on 30 June 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).