Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition, Standards and Programmes for Monitoring the Intensity of Agricultural Land Use

2.1. Definition of A-LUI

2.2. Programmes for Monitoring A-LUI at National, European and Global Scale

- Land Register: The land register records the types of land and their use in Germany. It is maintained by the state surveying and land registry offices. Most countries have detailed land register records of land type and ownership, maintained by the state surveying and land registry offices.

- Agricultural Structure Survey: Regular surveys of agricultural land use, yields, livestock, etc. by National Statistical Offices.

- IACS (Integrated Administration and Control System for Management Aid): In agriculture, the IACS system plays a central role in monitoring and managing data such as information on the use of plant protection products, fertiliser data, soil and water data, and yield and production data, as well as environmental and health data. The monitoring and control of IACS data in agriculture is carried out by different institutions and authorities, mainly at regional, national and European level.

- Europe

- Corine: The European Environment Agency (EEA) coordinates various land use monitoring projects, including the production of Corine Land Cover maps.

- Lucas: LUCAS (Land Use/Cover Area Frame Survey) This is a regular statistical survey of land use and land cover in the EU.Copernicus data: Copernicus is the European Earth Observation Programme (ESA) and provides extensive data on land use from satellite data (Sentinel-1-3).

- Farm structure survey datasets (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Farm_structure_survey_(FSS))

- Agricultural census data (e.g. production, environmental indicators) at national levels and at sub-national levels (NUTS 1, NUTS 2, NUTS3). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/agriculture/information-data#Agricultural%20production.

- World

- Global Land Cover (GLC): Several international initiatives produce global land cover maps, including projects supported by FAO and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

- MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer): An instrument on NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites that provides global data on land cover and land use change.

- Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD): A University of Maryland project to monitor global land use using high-resolution satellite imagery.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations), OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and World Bank (World Bank) use indicators to monitor A-LUI worldwide.

3. Approaches to Monitoring of A-LUI

3.1. In Situ Approaches

3.2. Remote Sensing Approach

3.2.1. Principles of Recording A-LUI Using RS

3.2.2. Challenges of Recording A-LUI Using RS

4. Definition of A-LUI Using RS

- (I)

- The trait indicators of LUI, which represents the diversity of the biochemical-, physical, optical, morphological-, structural-, textural- and functional characteristics of LUI traits that affect, interact with or are influenced by their genese-, taxonomic-, structural- and functional LUI indicators;

- (II)

- The genesis indicators of LUI, which refers to the diversity of the length of evolutionary pathways associated with a particular set of LUI traits, taxa, structures and functions of LUI diversity. Therefore, groups of LUI traits, LUI taxa, LUI structures and LUI functions that maximise the accumulation of functional diversity of LUI diversity are identified;

- (III)

- The structural indicators of LUI, namely, the diversity of the composition and configuration of LUI characteristics;

- (IV)

- The taxonomic indicators of LUI, representing the diversity of LUI components that differ from a taxonomic perspective;

- (V)

- The functional indicators of LUI, which is the diversity of LUI functions and processes, as well as their intra- and interspecific interactions.

4.1. Monitoring the Trait Indicators of A-LUI Using RS

4.1.1. Trait Indicators of A-LUI - Spectranometric Approach

4.1.2. Trait Indicators of A-LUI - Chlorophyll Content

4.1.3. Trait Indicators of A-LUI - Chlorophyll Fluorescence

4.1.4. Trait Indicators of A-LUI - Leaf Nitrogen Content

4.2. Monitoring the Genesis Indicators of A-LUI with RS

4.2.1. Genesis Indicators of A-LUI - Subsurface Drainage

4.2.2. Genesis Indicators of A-LUI - Terrace Mapping

4.2.3. Genesis Indicators of A-LUI - Allmenden

4.2.4. Genesis Indicators of A-LUI - Deforestation

4.3. Monitoring the Structural Indicators of A-LUI with RS

4.3.1. Structural A-LUI Indicators - Crop Composition and Configuration

4.3.2. Structural A-LUI Indicators - Surface Roughness of the Vegetation

4.3.3. Structural A-LUI Indicators - Soil Roughness

4.4. Monitoring the Taxonomic A-LUI Indicators with RS

4.4.1. Taxonomic A-LUI Indicators - Cropping Patterns

4.4.2. Taxonomic A-LUI Indicators - Crop Classifications

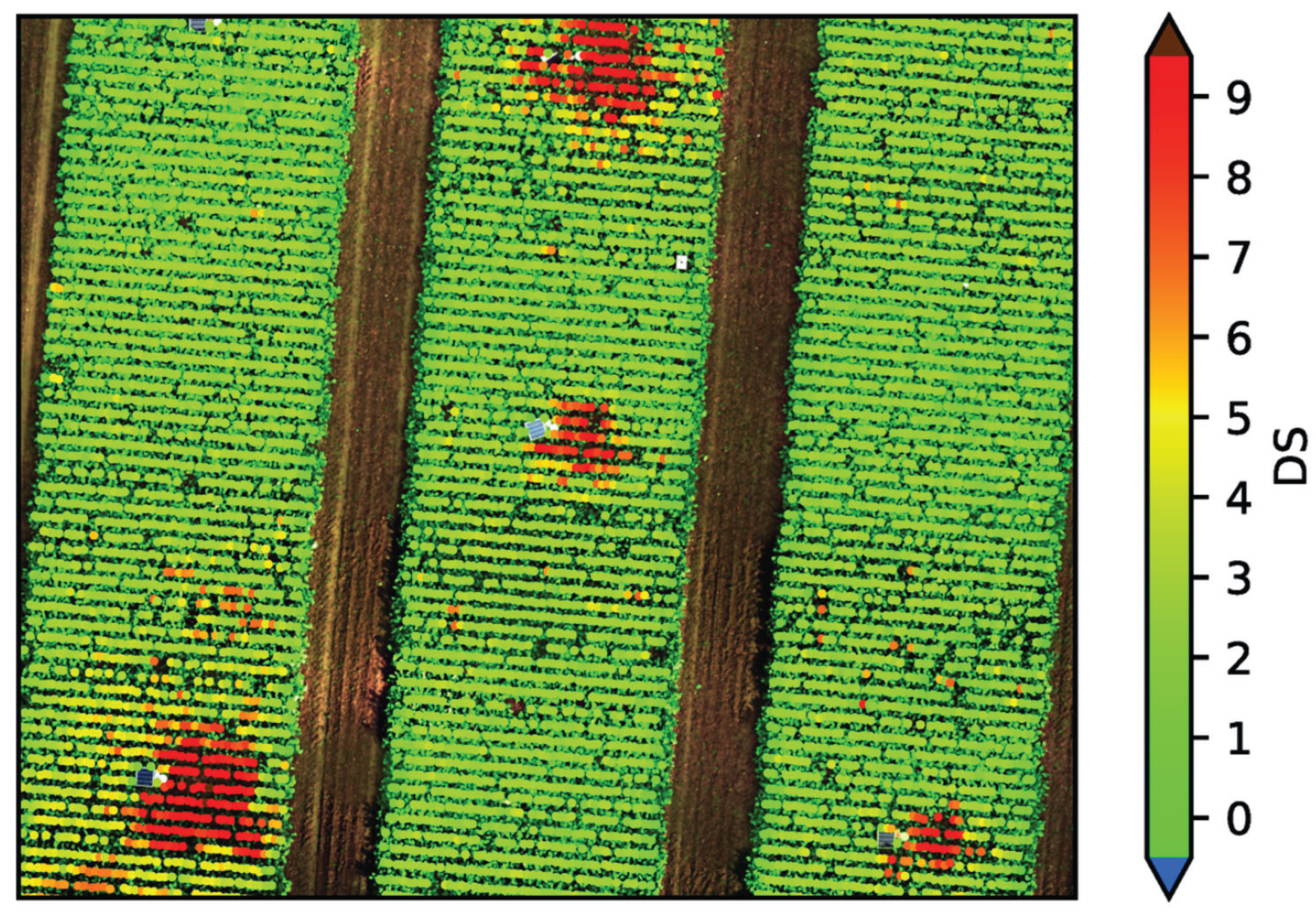

4.4.3. Taxonomic A-LUI Indicators - Intensification of Grassland

4.5. Monitoring the Functional A-LUI Indicators with RS

4.5.1. Functional A-LUI Indicators - Plant Density and Biomass Production

4.5.2. Functional A-LUI Indicators – Pesticide, Herbicide and Fungicide

4.5.3. Functional A-LUI Indicators - Fertilisation Intensity

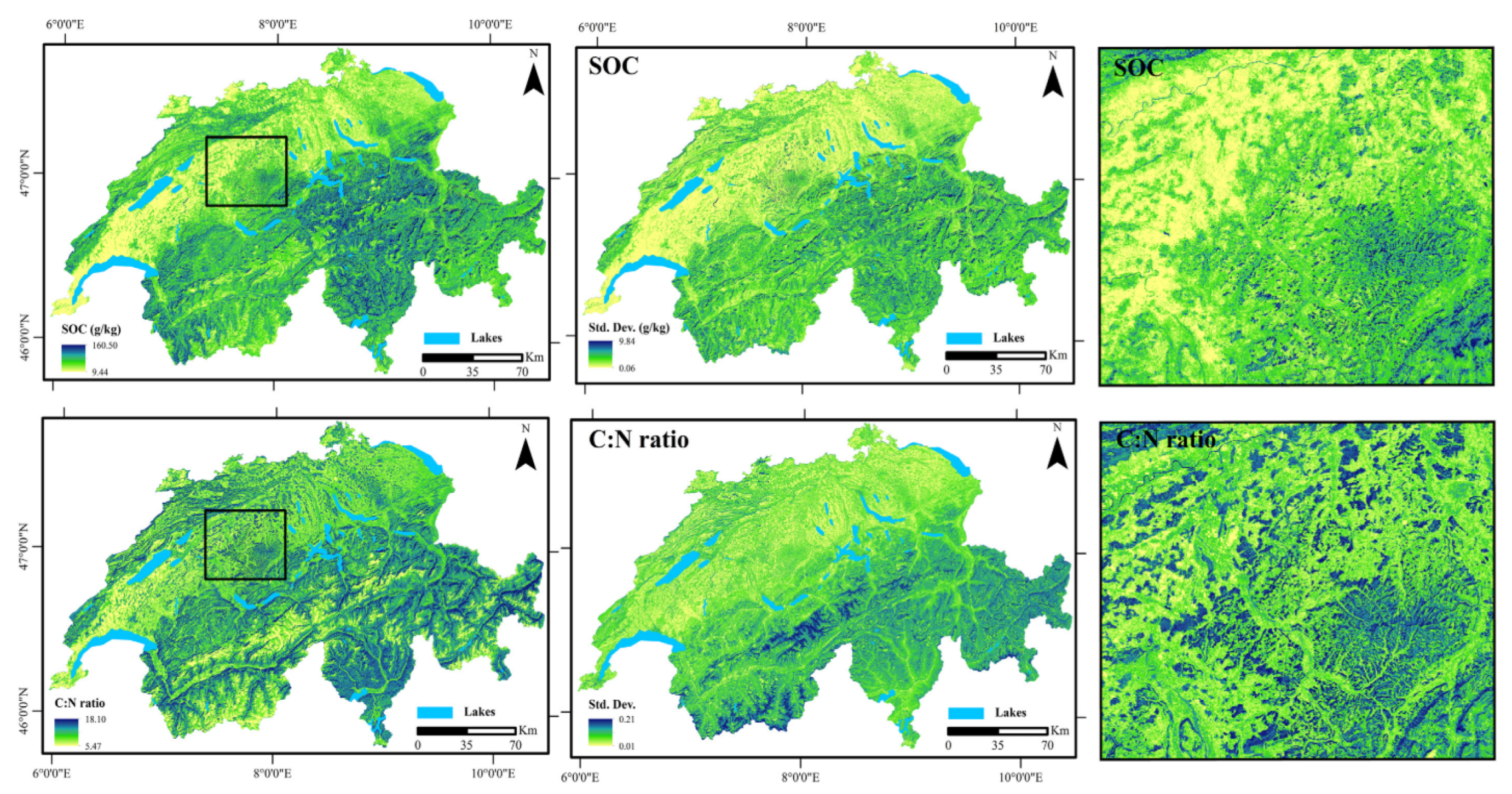

4.5.4. Functional A-LUI indicators - Soil Organic Carbon (SOC)

5. New Approaches for the Quantification and Evaluation of A-LUI Using RS

5.1. RS and AI for Recording A-LUI

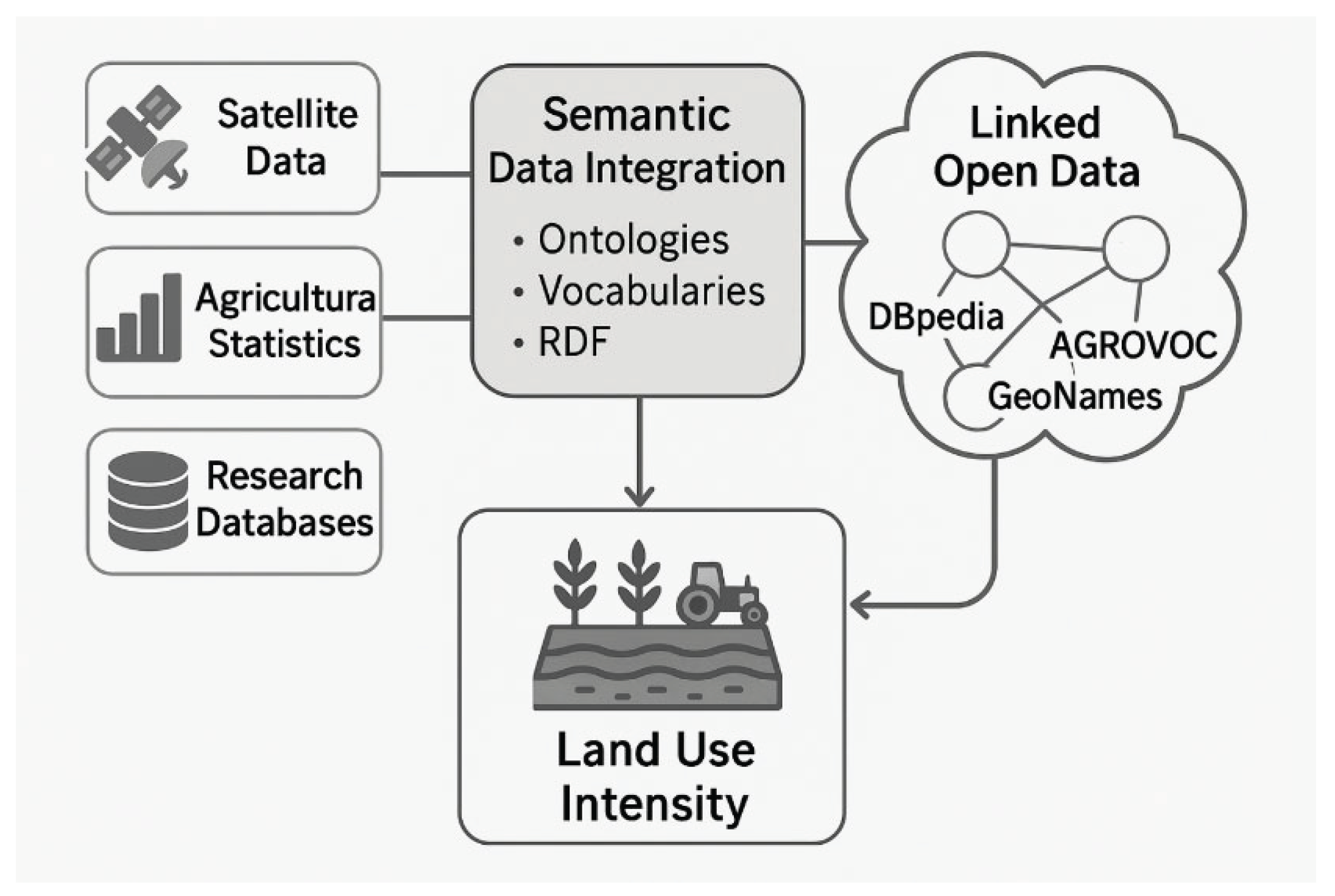

5.2. Semantic Web and Linked Open Data for the Monitoring of A-LUI

6. Conclusions and Further Research

- Integration of different RS technologies: Development of integrated multi-sensor approaches to capture specific management practices more precisely and map them in a spatially differentiated way.

- Hybrid modelling and AI-based approaches: Further development of hybrid models that combine physical radiative transfer models with data-driven methods to capture complex ecological and agricultural processes even more accurately.

- Standardisation and harmonisation: Promotion of international cooperation to standardise RS data and indicators in order to increase comparability and global applicability.

- Scaling strategies: Research into effective scaling approaches to link local, detailed in-situ data with large-scale RS data in order to develop robust models for large-scale applications.

- Sustainability assessment: Greater integration of RS-based indicators into environmental and socio-economic modelling to provide more comprehensive assessments of the sustainability and environmental impacts of agricultural intensification strategies.

- This considerably improves the informative value and practical applicability of RS-based LUI indicators and thus contributes significantly to the sustainable development of agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| FAO | OECD | World Bank | EUROSTAT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Geographical area of monitoring |

Worldwide coverage, with a special focus on developing countries | Primarily OECD member countries, focus on highly developed industrialised nations | Developing countries and emerging markets | European Union (EU) and some enlargement countries |

| Time availability of the indicators | Indicators of land use intensity have been available since the 1960s, Increased surveillance since the 1990s |

Data and analyses on land use intensity since the 1980s, Regular reports since the early 2000s. |

Data on land use intensity since the 1990s, Comprehensive database (WDI) since the 2000s. |

Harmonised data on agriculture and land use since the 1990s, Regular (every three to five years) surveys since the 1990s |

| Link | FAO database FAOSTAT https://www.fao.org/statistics/data-dissemination/agrifood-systems/en, (data access: 11.07.2024) |

OECD https://www.oecd.org/, (data access: 11.07.2024) |

World Development Indicators (WDI) https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-, (data access: 11.07.2024) |

Farm Structure Surveys (FSS) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/farm-structure-survey (data access: 11/07/2024) |

| Indicators (selective examples) | ||||

| Indicator | FAO | OECD | World Bank | Eurostat |

| Agricultural area | Total area for agriculture (arable land, permanent grassland, permanent crops) | Agricultural land, including arable land, permanent crops, and pastures | Agricultural land (sq. km) | Utilised agricultural area (UAA) |

| Arable land | Land for crops, including repeatedly cultivated soils and fallow land | Arable land, including temporary crops and fallow land | Arable land (hectares) | Arable land |

| Permanent grassland | Land for perennial grasses and forage plants | Permanent pastures and meadows | Permanent meadows and pastures (hectares) | Permanent grassland |

| Permanent crops | Land for perennial crops such as fruit trees and vineyards | Permanent crops, such as orchards and vineyards | Permanent crops (hectares) | Permanent crops |

| Harvest yields | Amount of crop per unit area | Crop yields, measured by specific crop outputs per hectare | Cereal yield (kg per hectare) | Crop production per unit area |

| Use of fertilisers | Amount of fertiliser per hectare | Fertiliser consumption (kg per hectare of arable land) | Fertiliser consumption (kg per hectare of arable land) | Consumption of fertilisers per unit area of agricultural land |

| Pesticide use | Amount of pesticides per hectare | Pesticide sales and usage | Pesticide consumption (kg per hectare of arable land) | Pesticide sales and consumption |

| Irrigated area | Proportion of artificially irrigated agricultural land | Area equipped for irrigation (hectares) | Irrigated land (% of total agricultural land) | Irrigated area |

| Machine inventory | Number and type of machines per unit area | Agricultural machinery, such as tractors per hectare | Agricultural machinery (tractors per 100 sq. km of arable land) | Number of tractors and other agricultural machinery per unit area of agricultural land |

| Labour input | Labour hours per unit area | Labour input in agriculture, measured by hours worked per hectare | Employment in agriculture (% of total employment) | Labour force in agriculture |

| Livestock density | Number of animals per unit area of pastureland | Livestock density, measured as livestock units per hectare of pasture land | Livestock production index | Livestock density per unit area of pasture land |

| Carbon sequestration in the soil | Amount of carbon sequestered in the soil | Soil organic carbon content | Soil organic carbon content | Soil organic carbon content |

| Ground cover | Type and extent of ground cover | Land cover types and changes | Land cover (% of land area) | Land cover and land use |

| Erosion risk | Risk of soil erosion due to water or wind | Soil erosion rates | Soil erosion rates | Soil erosion and degradation risk |

| Biodiversity | Diversity of plant and animal species on farmland land (eg. Farmland birds, pollinators, butterflies) | Farmland biodiversity indices (eg. Farmland birds, pollinators, butterflies) | Agricultural biodiversity indices (eg. Farmland birds, pollinators, butterflies) | Biodiversity indicators in agricultural landscapes (eg. Farmland birds, pollinators, butterflies) |

| Water consumption in agriculture | Amount of water used for irrigation | Agricultural water withdrawal | Agricultural water withdrawal (% of total water withdrawal) | Water use in agriculture |

| Agricultural production per unit of input | Efficiency of the means of production in agriculture | Total factor productivity in agriculture | Agricultural value added per worker | Output per hectare of agricultural land |

| Energy consumption in agriculture | Energy consumption in agriculture | Energy use in agriculture | Energy use in agriculture | Energy consumption in agriculture |

| Sustainability indicators | Sustainability of agricultural practices | Sustainable agriculture practices indicators | Sustainable land management indicators | Sustainable farming practices |

| Climate impact of agriculture | Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture | Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture | Agricultural methane emissions (kt of CO2 equivalent) | Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture |

| Nutrient balance in the soil | Balance of nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil | Nitrogen and phosphorus balance | Soil nutrient balance | Nutrient balance in agricultural soils |

| Bioproductivity | Productivity of biological systems on agricultural land | Biological productivity of agricultural systems | Agricultural productivity indexes | Biological productivity of agricultural lands |

| Plant protection measures | Measures to combat pests and diseases | Pest and disease control practices | Pest and disease control indicators | Plant protection measures and their impact |

| Energy efficiency in agriculture | Efficiency of energy consumption in agriculture | Energy efficiency in agricultural practices | Energy productivity in agriculture | Energy efficiency indicators in farming |

| Utilisation of genetic resources | Utilisation and conservation of genetic resources in agriculture | Use and conservation of genetic resources | Genetic resource management indicators | Conservation and use of agricultural genetic resources |

| Landscape diversity | Diversity of landscapes and agroecosystems | Landscape diversity and heterogeneity | Landscape diversity indicators | Landscape heterogeneity and diversity in agricultural areas |

| Soil compaction | Degree of soil compaction caused by agricultural machinery | Soil compaction indicators | Soil compaction risk | Soil compaction due to agricultural practices |

| Waste management in agriculture | Handling agricultural waste | Agricultural waste management practices | Waste management in agriculture | Management and recycling of agricultural waste |

| Soil moisture | Moisture content of the soil | Soil moisture levels | Soil moisture content indicators | Soil moisture monitoring in agricultural lands |

| Landscape fragmentation | Fragmentation of natural and agricultural landscapes | Landscape fragmentation and its impact on agriculture | Landscape fragmentation indexes | Impact of landscape fragmentation on agriculture |

| Sustainable land use practices | Spreading sustainable agricultural practices | Adoption of sustainable agricultural practices | Sustainable land management practices | Implementation of sustainable farming practices |

| Water utilisation efficiency | Efficiency of water utilisation in agriculture | Water use efficiency in agricultural practices | Agricultural water productivity | Water use efficiency in irrigated agriculture |

| Agroecological indicators | Indicators for the assessment of agroecological systems | Agro-ecological assessment indicators | Agro-ecological practices | Assessment of agro-ecological systems |

| Erosion due to wind | Loss of topsoil due to wind erosion | Wind erosion rates | Wind erosion indicators | Impact of wind erosion on agricultural land |

| Soil fertility | Level of soil fertility and its changes | Soil fertility levels | Soil fertility indicators | Changes in soil fertility |

| Land use changes | Changes in the utilisation of agricultural land | Changes in agricultural land use | Land use change indicators | Agricultural land use changes |

| Irrigation efficiency | Efficiency of irrigation methods | Irrigation efficiency | Efficiency of irrigation systems | Efficiency of water use in irrigation systems |

| Climate adaptation measures | Measures to adapt to climate change | Climate adaptation practices in agriculture | Climate resilience indicators | Implementation of climate adaptation measures in agriculture |

| Resource utilisation efficiency | Efficient use of natural resources | Resource use efficiency in agriculture | Resource productivity indicators | Efficiency of resource use in agriculture |

| Soil acidification | Degree of soil acidification and its causes | Soil acidification levels | Soil pH indicators | Impact of acidification on agricultural soils |

| Soil salinisation | Level of soil salinisation and its effects | Soil salinisation rates | Soil salinity indicators | Effects of salinisation on agricultural productivity |

| Utilisation of renewable energies | Share of renewable energies in agriculture | Renewable energy use in agricultural practices | Share of renewable energy in agriculture | Use of renewable energy sources in farming |

| Environmentally friendly cultivation methods | Spreading environmentally friendly cultivation methods | Adoption of eco-friendly farming practices | Eco-friendly agricultural practices | Implementation of environmentally friendly farming methods |

| Economic sustainability | Economic viability of farms | Economic sustainability of agricultural holdings | Economic viability indicators | Economic sustainability of farms |

| Social sustainability | Social aspects of agricultural practice | Social sustainability in agriculture | Social indicators in rural areas | Social impacts of agricultural practices |

| Productivity per unit area | Productivity of agricultural land | Land productivity indicators | Productivity of agricultural land | Output per unit of agricultural area |

| Water quality indicators | Impact of agriculture on water quality | Impact of agriculture on water quality | Water quality in agricultural areas | Effects of agricultural runoff on water quality |

| Infrastructure for agriculture | Availability and quality of agricultural infrastructure | Agricultural infrastructure development | Infrastructure investment in agriculture | Quality and accessibility of agricultural infrastructure |

| Innovation in agriculture | Implementation of new technologies and processes | Agricultural innovation and technology adoption | Innovation indicators in agriculture | Adoption of new agricultural techn |

| Satellit / Mission | Sensor / Typ | Spatial resolution | Spectral bands / Sensor typ | Availability | Start date |

Operator of the satellite mission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WorldView-3 | Visible (PAN+MS+SWIR) | 0,31 m (PAN), 1,24 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral SWIR |

Commercial | 2014 | Maxar |

| WorldView-2 | Optically | 0,46 m (PAN), 1,84 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral |

Commercial | 2009 | Maxar |

| GeoEye-1 | Optically | 0,41 m (PAN), 1,65 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral |

Commercial | 2008 | Maxar |

| Pleiades Neo | Optically | 0,3 m (PAN), 1,2 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral |

Commercial | 2021+ | Airbus |

| Pleiades 1A/1B | Optically | 0,5 m (PAN), 2,0 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral |

Commercial | 2011/2012 | Airbus |

| SkySat | Optically + Video | 0,5–0,8 m (PAN), 1–2 m (MS) | RGB, NIR, Video | Commercial | 2013+ | Planet |

| BJ-3B (SuperView-2) | Optically | 0,3 m (PAN), 1,2 m (MS) | Panchromatic Multispectral |

Commercial | 2022 | 21AT (China) |

| Capella Space | RADAR (X-Band SAR) | 0,3–0,5 m (Spotlight) | SAR | Commercial | 2018+ | Capella Space (USA) |

| ICEYE | RADAR (X-Band SAR) | 0,25–1 m | SAR | Commercial | 2018+ | ICEYE (Finnland) |

| TerraSAR-X | RADAR (X-Band SAR) | bis 1 m (Spotlight-Modus) | SAR | Commercial / Scientifically free | 2007 | DLR / Airbus |

| PAZ | RADAR (SAR) | 1 m | SAR (X-Band) | Commercial | 2018 | Hisdesat (Spain) |

| Sentinel-1A/B | RADAR (C-Band SAR) | 10 m | SAR | Freely available | 2014/2016 | ESA / Copernicus |

| Drohnen / UAV | Optically + Multispectral | < 0,1 m | RGB, Multispectral, Hyperspectral, LiDAR |

Own operation | User-based | |

| Aerial photos | Optically | 0,20cm | Orthophotos (DOP) True Orthophotos, RGB, CIR |

Commercial / Authorities and partly scientific free | Federal states, Federal Agency for Cartography and Geodesy |

| Indikator | Satelliten | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Trait diversity of LUI | ||

| Chlorophyll-a/b Content Leaf chlorophyll content (LCC) Chlorophyllgehalt (Cab) Canopy Chlorophyll Content (CCC) Carotinoide, anthocyanin Anthocyanin reflectance index (ARI) Carotenoid reflectance index (CRI) |

Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, Landsat 81, CRIME1, , EnMAP1, Airborne hyperspectral CASI2, Airborne Visible/ Infrared Imaging Spectrometer AVIRIS2, Airborne HyMap2, UAV-(HSP,MSP)3, Handheld portable hyperspectral camera (Specim IQ) ASD4, Laboratory spectroscopy5 |

[87,88,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,94,97,110,247,248,249,250,251] |

| Foliar Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium - NPK | UAV (LiDAR, MSP) 3, SVC HR-1024i spectrometer ASD4 | [87,260,261] |

|

Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF), Photosynthesis activity |

Sentinel-31, GOSIF data1, AS-SpecFOM (Ground based)6, FluoSpec2 system (Ground based) | [72,99,262,263,264,265] |

| Leaf nitrogen content (LNC) Nitrogen use efficiency, Nitrogen nutrition index |

Sentinel-21, CRIME1, PRISMA1,Airborne micro-hyperspec NIR-100 camera2, UAV | [87,88,90,111,112,266,267] |

| Plant water content Leaf water content Plant water stress Cropland water-use efficiency Crop Water Productivity |

GLASS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, UAV (MSP, HSP)3, mmWave RADAR (Tower)6, Cropland ecosystem flux sites6, Local TIR Sensor6, |

[268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276] |

| Land Surface Temperature Crop surface temperature |

Landsat1, High Spatio-Temporal Resolution Land Surface Temperature Monitoring (LSTM) Mission1, UAV (TIR, RGB, MSP)3 |

[272,277,278,279,280,281] |

| Evapotranspriration (ET) Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) |

MODIS1, DEIMOS-1 is a commercial tasking EO satellit1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, SuperDove satellites (PlanetScope)1, UAV-(RGB, MSP, TIR)3 | [282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290] |

| Soil moisture | MODIS-Terra1, Landsat1,AMSR-21,AMSR-E1, NISAR1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, SMAP1, Airborne hyperspectral (DAIS)2, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk) 2 | [291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299] |

| Irrigation Irrigation Efficiency Water Productivity and Efficiency Irrigation patterns Water-Ferilizer use efficency Water Stress Soil Water Deficit Soil water stress |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, UAV (MSP)3, ASD4, |

[300,301,310,311,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309] |

| LAI (Leaf Area Index) | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, UAV-(HSP, TIR, LiDAR)3, Ocean Optics USB2000 (Tower)6 | [255,256,312,313,314] |

| Genese Trait Diversity of LUI | ||

| Subsurface drainage systems, Drainage density |

RADAR (SAR)1, Landsat1, Senitnel-21, Airborne LiDAR2, Airborne data2, UAV – RGB, CIR, TIR3 | [124,125,126,127,128,315,316] |

| Terrace mapping | Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, GF-2 satellite image1, WorldView-11, WorldView-31, Airborne LiDAR2, UAV-LiDAR3 | [129,130,131,136,137,138] |

| Allmenden | Airborne LiDAR3 | [139,140] |

| Deforestation | MODIS1, ALOS PALSAR data1, RADARSAT-21, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, UAV (RGB, NIR, IRT)3 | [143,144,145,146,147,317,318,319,320] |

| Polder and single-polder systems | Google Earth RS data1, Corona spy satellite imagery1 | [321,322] |

| DEM (Digital Elevation Model) DSM (Digital Surface Model) |

SRTM1, TerraSAR-X1, TanDEM-X1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-31, ALOS-2 PALSAR-21, ALOS PRISM1, Terra ASTER1, ICESat GLAS1, Airborne LiDAR2, UAV (SAR, RGB)3 | [61,323,332,333,334,335,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331] |

| Soil Topography Farmland microtopography feature |

Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, CORONA KH-4B1, Gaofen-7 satellite1, Airborne LiDAR2 | [166,336,337,338,339,340] |

| Soil metagenomics data | UAV (MSP, LiDAR)3 | [341] |

| Structural traits of LUI | ||

| Soil, crop vegetation composition and configuration (e.g. Patch-size, distribution Field size, Interspersion and Juxtaposition Index, Proximity Index, Edge Density, Edge Contrast Index, Contagion Index, Core Area Index, Shape Index, Cropland Extent, Fragmentation,Homogenity, Isolation, Landuse intensity patterns, Canopy structure Farmland Boundary Extraction, Cropland extent, Cropland area, Harvested Area Fraction, Structural Connectivity Index, Vegetation Coherence Index, Crop Richness, Crop Evenness, Crop Simpson's Diversity Index, Fractal Dimension Index, Entropy Index, Clumping Index, Grassland plant species diversity Plant density |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Spot1, Sentinel-21, WorldView-2/-31, QuickBird1, Pleiades1, GeoEye1, GF-21, RapidEye1, PlanetScope1, Airborne Hyperspectral AVIRIS and HYDICE2, Airborne data2, UAV (RGB, MSP, HSP)3 | [31,33,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,67,354,355,356,148,149,156,157,266,342,343] |

| Vertical Vegetation Structure, Vegetation Height, Plant heigh 3D-structures, 3D mapping |

GEDI LiDAR1, ICESat-21, UAV (RGB, LiDAR) Phenotyping robot “MARS-PhenoBot”6, 6-DOT robot6, RGB-Camera6, Terrestrial LiDAR6 |

[357,358,359,360,361,362] |

| Surface roughness Cnopy roughness |

Sentinel-11, MODIS1, UAV (RGB)3 | [162,163,164] |

| Spektraler Heterogenität, Rao's Q diversity index, Plant Species Richness Spatiotemporal variability |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21 | [160,161,363] |

| Homogeneity Index, Grasland Homogeneity Index Crop homoneneity |

Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, GF-21 | [364,365,366] |

| Soil Roughness, Soil texture, Farmland microtopography |

Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, AHSI/ZY1-02D satellite1, SRTM1, Airborne LiDAR2, ASD Handspectometer4, Smartphone-captured digital images6 | [166,167,374,375,340,367,368,369,370,371,372,373] |

| Taxonomic LUI | ||

| Cropping patterns (single cropping, multiple cropping, sequential cropping, intercropping) |

MODIS1, Spot1, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel 21, IRS1, WiFS1, Airborne AVIRIS2, RADARSAT-21, Airborne LiDAR2 | [150,168,177,178,181,376,377,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176] |

| Crop classification, Crop type classification Crop type mapping |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, Sentinel-31, Airborne AVIRIS2, UAV (HSP)3 | [135,151,182,378,379,380,381,382,383,384] |

| Classification of grassland community types | Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21 | [385,386,387] |

| Cropping frequency (single cropping/double cropping/triple cropping) Crop-rotation Multi-cropping frequency (MCF) Croping intensity Cropping intensity index Change Detection crops |

MODIS1, Gaofen-11, GF-11, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21 | [169,183,394,395,396,397,349,377,388,389,390,391,392,393] |

| Crop residue cover mapping | Landsat1, Sentinel-21, Google Earth Engine1, UAV3, FieldSpec Pro4, Photo analysis surveys6 |

[398,399,400,401,402,403] |

| Crop burning residue | MODIS1, AVHRR1, LISS-III1, LISS-IV1, UAV3 | [404,405,406] |

| Classification between cultivated and fallow fields |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21 | [376,388,407,408,409] |

| Organic, conventional farming Organic and non-organic farming |

Landsat1, Spot1, Sentinel-21, KOMPSAT-21, WorldView-21, UAV (RGB)3, Hyperspectral ASD4 | [410,411,412,413] |

| Phenotyping, Phenology, Phenology-Stadien (BBCH-Scale) |

UAV (RGB, MSP, HSP, TIR, LiDAR)3, UAV (RGB, VIS, NIR, TIR, LiDAR)3, Labor-Hyperspectral – AISA-EAGLE5 | [252,312,335,414,415,416,417,418,419] |

| Crop growth duration (GDa), | MODIS1, Landsat1, Gaofen-11, Sentinel-21, RapidEye1, UAV (SAR)2 | [394,420,421,422,423] |

| Hedgerow map classifications, Hedgerows and field margins |

TerraSAR-X1, Spot1, IKONOS1, Airborne MSP2, Aerial photographs2, UAV (RGB, MSP)3 | [424,425,426,427,428,429] |

| Flower strip mapping Flower Mapping |

Airborne Hyperspectral (HySPEX, RGB, TIR)2, Airborne Hyperspectral (AISA-Eagle)2, Airborne MSP2, UAV (MSP, HSP)3 | [429,430,431,432,433,434] |

| Buffer Zone Efficiency Agricultural Pesticides Drift zones |

Landsat1, Sentinel-21 | [435] |

| Classification of agroforestry systems | RapidEye1, PlantetScope1, LISS IV1, Sentinel-21 | [436,437,438,439,440] |

| Plastic-covered greenhouses Plasticulture detection Plastic greenhouses (PGs) and Plastic-mulched farmland (PMF) |

Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, GF-2 | [441,442,443,444,445] |

| Crop yield predictions Grain Yield, Protein estimation |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, UAV – (MSP, HSP)3 | [266,446,455,447,448,449,450,451,452,453,454] |

| Hop cultivation classification | UAV (MSP)3, Mobile phone camera6 | [456,457] |

| Functional traits of LUI | ||

| Crop biomass, Aboveground biomass (AGB), Relative biomass potential (rel. BMP) |

MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, PlanetScope1, UAV (MSP, RGB)3, Smartphone6 | [188,189,190,191,192,193,194,301,458] |

|

Plant Nitrogen Concentration (PNC) Leaf Nitrogen Content Fertilization Gradient |

Sentinel-21, UAV (MSP, TIR)3 | [94,203,204,205,459,460,461] |

| Soil organic carbon (SOC) Soil organic matter (SOM) |

ALOS-21, PALSAR-21, Landsat1, Spot 4/51, GF-11, RADAR (PLAS)1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, Sentinel-31, Airborne hyperspectral (DAIS)2, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2, Hyperspectral APEX2, UAV (SAR)3, VIS–NIR spectroscopy (Field)1, | [208,213,465,466,467,468,469,470,471,472,473,474,214,219,221,222,299,462,463,464] |

| Clay content | Landsat1, Aster1, Sentinel-21, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2 | [375,475,476,477,478,479,480,481] |

| Soil total nitrogen (TN) N-Monitoring Total soil nitrogen (TSN) Nutritional Status Soil Total Nitrogen Soil Nutrients Contents |

Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, GF-11, UAV (HSP, MSP, TIR)3, ASD (Field)4 | [206,213,488,469,480,482,483,484,485,486,487] |

| C:N Ratio Soil | Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, Sentinel-31 | [222,468,489,490,491,492] |

| Carbon use efficiency (CUE) | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21 | [493,494,495,496] |

| Silt content | GF-11, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2, | [375,497] |

| Sand content | Landsat1, Sentinel-21, Aster1, GF-11, Planet/NICFI1, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2 | [375,481,497,498,499,500,501] |

| Potassium content | PRISMA1, UAV (MSP)3 | [484,485] |

| Phosphorus content (P) | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, PRISMA1, UAV (MSP, LiDAR)3, ASD4 | [341,484,485,486,487,502] |

|

Pestizide, Herbizide, Fungizide Pest management |

Sentinel-21, UAV3, Local hyperspectral camera6, ASD - LeafSpec hyperspectral images4 | [195,196,197,198,199,200,503,504] |

| Plant Disease Detection, Crop vegetation health Plant health |

Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, UAV (RGB, MSP, VIS, NIR, TIR, LiDAR)3, ASD FieldSpec Pro FR4 | [97,202,511,512,513,514,515,516,411,416,505,506,507,508,509,510] |

| CSR-Plant Strategie Types Plant functional groups (PFGs) Ellenberg Indicator Species |

Landsat1, Sentinel-21, Airborne hyperspectral data (AISA dual)2, Airborne AISA Fenix2, Airborne imaging spectrometer APEX2, Airborne hyperspectral HySpex2 | [517,518,519,520,521,522,523,524] |

| Gross Primary Production (GPP) Dynamic of carbon emissions, Carbon Fluxes |

MODIS1, Meris1, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, Sentinel-31, Hyperspectral Ocean Optics USB2000 (Tower)6, LEDAPS-Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET)6 | [254,493,525,526,527,528,529,530,531,532] |

| Cropland NPP | MODIS1, Landsat1, UAV (MSP)3 | [149,314,493,533,534,535,536,537,538] |

| HANPP (Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production) | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21 | [539,540,541,542,543] |

| Water use efficiency (WUE) | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21 | [493,544,545,546,547,548] |

| Yield and Quality | Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, UAV (MSP)3 | [193,531,549,550,551,552,553,554,555,556] |

| Harvest Index | MODIS1, HJ-1 satellite1, Sentinel-21, UAV (HSP)3, FieldSpec HandHeld Spectroradiometer (ASD)4 | [557,558,559,560] |

| Soil quality index (SQI) | Landsat1, Sentinel-21, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA)2 | [338,561,562] |

| Soil productivity potential | MODIS1, Landsat1, Sentinel-21, ASD FieldSpec4 | [310,480,563,564,565] |

| Soil Crust | KOMPSAT-2 satellite1, Airborne hyperspectral (DAIS)2, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2, UAV (RGB, MSP, HSP)3, ASD Fieldspec4 | [299,566,567,568,569,570,571,572] |

| Soil infiltration | Airborne hyperspectral (DAIS)2, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2, Airborne CASI-15002, SASI-6002, Airborne TASI-600 hyperspectral sensors2, UAV (HSP, Cubert UHD-185)3 | [299,573,574] |

| Soil-pH value | PALSAR-1/21, SRTM1, Landsat1, PlantetScope1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, UAV (MSP)3, ASD FieldSpec4 | [298,368,582,583,584,585,555,575,576,577,578,579,580,581] |

| Soil salinity Soil salinization |

Landsat1, RADAR1, Airborne LiDAR2, HJ-1 Hyperspectral Imager Data2 | [298,586,587,588,589,590,591,592,593] |

| Land degradation, Soil degradation, Soil erosion Desertification |

Landsat1, SRTM1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, RapidEye1, Airborne hyperspectral (DAIS)2, Airborne hyperspectral (AISA Eagle, Hawk)2, UAV (RGB)3 | [299,594,595,596,597,598,599] |

| Soil compaction Soil Compaction Index Soil aggregation Soil penetration resistance |

Landsat1, GoogleEarth aerial imagery1, Sentinel-21, RapidEye1, Airborne hyperspectral (CASI)2, UAV (RGB, SAR, LiDAR, MSP, TIR)3 | [595,600,601,602,603,604,605,606,607] |

| Cattle intensification, Spatial distribution of cattle |

Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21 | [608] |

| Grassland-use intensity Grassland management intensity |

Landsat1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, RapidEye1, | [184,187,609,610,611,612,613] |

| Grasland fire | MODIS1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21, GF-6 WFV1, UAV3 | [614,615,616,617,618] |

| Grassland cut detection | SAR1, Sentinel-11, Sentinel-21 | [619,620,621] |

| Different Water quality indicators | All RS Sensors with all RS characteristics (MSP, HSP, TIR, RADAR, LiDAR) | [63] |

References

- Diogo, V.; Helfenstein, J.; Mohr, F.; Varghese, V.; Debonne, N.; Levers, C.; Swart, R.; Sonderegger, G.; Nemecek, T.; Schader, C.; et al. Developing context-specific frameworks for integrated sustainability assessment of agricultural intensity change: An application for Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Srivastava, P.; Devi, R.S.; Bhadouria, R. Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 25–54.

- YAHAYA, S.M.; MAHMUD, A.A.; ABDULLAHI, M.; HARUNA, A. Recent advances in the chemistry of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as fertilizers in soil: A review. Pedosphere 2023, 33, 385–406. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Shahzad, B.; Yang, G.; Fahad, S.; Ali, S.; Bukhari, M.A.; Tung, S.A.; Hafeez, A.; Souliyanonh, B. Soil compaction effects on soil health and cropproductivity: an overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 10056–10067. [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water scarcity in agriculture: An overview of causes, impacts and approaches for reducing the risks. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18507. [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Jolly, I.; Sophocleous, M.; Zhang, L. Global impacts of conversions from natural to agricultural ecosystems on water resources: Quantity versus quality. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Rajan, S.; Nayak, S.K. Water pollution: Primary sources and associated human health hazards with special emphasis on rural areas. In Water Resources Management for Rural Development; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 3–14.

- Pannard, A.; Souchu, P.; Chauvin, C.; Delabuis, M.; Gascuel-Odoux, C.; Jeppesen, E.; Le Moal, M.; Ménesguen, A.; Pinay, G.; Rabalais, N.N.; et al. Why are there so many definitions of eutrophication? Ecol. Monogr. 2024, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Zabel, F.; Delzeit, R.; Schneider, J.M.; Seppelt, R.; Mauser, W.; Václavík, T. Global impacts of future cropland expansion and intensification on agricultural markets and biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mupepele, A.C.; Bruelheide, H.; Brühl, C.; Dauber, J.; Fenske, M.; Freibauer, A.; Gerowitt, B.; Krüß, A.; Lakner, S.; Plieninger, T.; et al. Biodiversity in European agricultural landscapes: transformative societal changes needed. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 1067–1070. [CrossRef]

- Burian, A.; Kremen, C.; Wu, J.S.T.; Beckmann, M.; Bulling, M.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Krisztin, T.; Mehrabi, Z.; Ramankutty, N.; Seppelt, R. Biodiversity–production feedback effects lead to intensification traps in agricultural landscapes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 752–760. [CrossRef]

- Le Provost, G.; Thiele, J.; Westphal, C.; Penone, C.; Allan, E.; Neyret, M.; van der Plas, F.; Ayasse, M.; Bardgett, R.D.; Birkhofer, K.; et al. Contrasting responses of above- and belowground diversity to multiple components of land-use intensity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3918. [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Gerstner, K.; Akin-Fajiye, M.; Ceaușu, S.; Kambach, S.; Kinlock, N.L.; Phillips, H.R.P.; Verhagen, W.; Gurevitch, J.; Klotz, S.; et al. Conventional land-use intensification reduces species richness and increases production: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 25, 1941–1956. [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Soliveres, S.; Penone, C.; Fischer, M.; Ammer, C.; Boch, S.; Boeddinghaus, R.S.; Bonkowski, M.; Buscot, F.; Fiore-Donno, A.M.; et al. Land-use intensity alters networks between biodiversity, ecosystem functions, and services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 28140–28149. [CrossRef]

- Gossner, M.M.; Lewinsohn, T.M.; Kahl, T.; Grassein, F.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Birkhofer, K.; Renner, S.C.; Sikorski, J.; Wubet, T.; et al. Land-use intensification causes multitrophic homogenization of grassland communities. Nature 2016. [CrossRef]

- Millard, J.; Outhwaite, C.L.; Kinnersley, R.; Freeman, R.; Gregory, R.D.; Adedoja, O.; Gavini, S.; Kioko, E.; Kuhlmann, M.; Ollerton, J.; et al. Global effects of land-use intensity on local pollinator biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2902. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.; Gwozdz, W. On the relation between monocultures and ecosystem services in the Global South: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 278, 109870. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, Z.; Song, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; van Kleunen, M.; Wu, J. Biodiversity increases resistance of grasslands against plant invasions under multiple environmental changes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Scanes, C.G. Human Activity and Habitat Loss: Destruction, Fragmentation, and Degradation. In Animals and Human Society; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 451–482 ISBN 9780128052471.

- Oliver, T.H.; Marshall, H.H.; Morecroft, M.D.; Brereton, T.; Prudhomme, C.; Huntingford, C. Interacting effects of climate change and habitat fragmentation on drought-sensitive butterflies. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 941–946. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.K.; Hemp, A.; Appelhans, T.; Becker, J.N.; Behler, C.; Classen, A.; Detsch, F.; Ensslin, A.; Ferger, S.W.; Frederiksen, S.B.; et al. Climate–land-use interactions shape tropical mountain biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Nature 2019, 568, 88–92. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.M.; Delzeit, R.; Neumann, C.; Heimann, T.; Seppelt, R.; Schuenemann, F.; Söder, M.; Mauser, W.; Zabel, F. Effects of profit-driven cropland expansion and conservation policies. Nat. Sustain. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [CrossRef]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Lupia, C.; Poerio, G.; Liguori, G.; Lombardi, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Mercuri, C.; Bulotta, R.M.; Britti, D.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock: A Serious Threat to Public Health. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khmaissa, M.; Zouari-Mechichi, H.; Sciara, G.; Record, E.; Mechichi, T. Pollution from livestock farming antibiotics an emerging environmental and human health concern: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Doolittle, W.E. THE CONCEPT AND MEASURE OF AGRICULTURAL INTENSITY. Prof. Geogr. 1978, 30, 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Herzog, F.; Steiner, B.; Bailey, D.; Baudry, J.; Billeter, R.; Bukácek, R.; De Blust, G.; De Cock, R.; Dirksen, J.; Dormann, C.F.; et al. Assessing the intensity of temperate European agriculture at the landscape scale. Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 24, 165–181. [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, G.; Jeanneret, P.; Schneider, M.K.; Turnbull, L.A.; Arndorfer, M.; Balázs, K.; Báldi, A.; Bailey, D.; Bernhardt, K.G.; Choisis, J.P.; et al. Responses of plants, earthworms, spiders and bees to geographic location, agricultural management and surrounding landscape in European arable fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 186, 124–134. [CrossRef]

- Helfenstein, J.; Hepner, S.; Kreuzer, A.; Achermann, G.; Williams, T.; Bürgi, M.; Debonne, N.; Dimopoulos, T.; Diogo, V.; Fjellstad, W.; et al. Divergent agricultural development pathways across farm and landscape scales in Europe: Implications for sustainability and farmer satisfaction. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2024, 86, 102855. [CrossRef]

- Canisius, F.; Turral, H.; Molden, D. Fourier analysis of historical NOAA time series data to estimate bimodal agriculture. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 5503–5522. [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Hostert, P.; St-Louis, V.; Radeloff, V.C. Using image texture to map farmland field size: A case study in Eastern Europe. J. Land Use Sci. 2009, 4, 85–107. [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Neumann, K.; Nol, L. Challenges in using land use and land cover data for global change studies. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 974–989. [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Erb, K.; Meyfroidt, P.; Müller, D.; Verburg, P.H.; Estel, S.; Haberl, H.; Hostert, P.; Jepsen, M.R.; Kastner, T.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in mapping land use intensity globally. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 484–493. [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Salbach, C.; Selsam, P.; Lausch, A. Urban land use intensity assessment: The potential of spatio-temporal spectral traits with remote sensing. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 190–203. [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.; Schwieder, M.; Ritter, L.; Koch, T.; Psomas, A.; Huber, N.; Ginzler, C.; Boch, S. Grassland-use intensity maps for Switzerland based on satellite time series: Challenges and opportunities for ecological applications. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 10, 312–327. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wen, Q.; Chen, J.; Kojima, S. Spatiotemporal Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Impact on Urban Thermal Environments: Analyzing Cool Island Intensity Variations. Sustain. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Liu, B.; Tang, Z.; Dong, J.; Xu, W.; Liang, J.; Chen, N.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. National-scale 10-m maps of cropland use intensity in China during 2018-2023. Sci. data 2024, 11, 691. [CrossRef]

- Hank, T.B.; Berger, K.; Bach, H.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Gitelson, A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.; Mauser, W. Spaceborne Imaging Spectroscopy for Sustainable Agriculture: Contributions and Challenges; Springer Netherlands, 2019; Vol. 40; ISBN 0123456789.

- Wulder, M.A.; Coops, N.C. Make Earth observations open access. Nature 2014, 513, 30–31. [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; Roy, D.P.; Radeloff, V.C.; Loveland, T.R.; Anderson, M.C.; Johnson, D.M.; Healey, S.; Zhu, Z.; Scambos, T.A.; Pahlevan, N.; et al. Fifty years of Landsat science and impacts. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 280, 113195. [CrossRef]

- Malenovský, Z.; Rott, H.; Cihlar, J.; Schaepman, M.E.; García-Santos, G.; Fernandes, R.; Berger, M. Sentinels for science: Potential of Sentinel-1, -2, and -3 missions for scientific observations of ocean, cryosphere, and land. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Guanter, L.; Kaufmann, H.; Segl, K.; Foerster, S.; Rogass, C.; Chabrillat, S.; Kuester, T.; Hollstein, A.; Rossner, G.; Chlebek, C.; et al. The EnMAP Spaceborne Imaging Spectroscopy Mission for Earth Observation. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 8830–8857. [CrossRef]

- Nieke, J.; Rast, M. Towards the Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission For The Environment (CHIME). In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2018 - 2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE, 2018; pp. 157–159.

- Dubayah, R.; Blair, J.B.; Goetz, S.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.; Healey, S.; Hofton, M.; Hurtt, G.; Kellner, J.; Luthcke, S.; et al. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation: High-resolution laser ranging of the Earth’s forests and topography. Sci. Remote Sens. 2020, 1, 100002.

- Lee, C.M.; Cable, M.L.; Hook, S.J.; Green, R.O.; Ustin, S.L.; Mandl, D.J.; Middleton, E.M. An introduction to the NASA Hyperspectral InfraRed Imager (HyspIRI) mission and preparatory activities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 167, 6–19.

- Kraft, S.; Del Bello, U.; Bouvet, M.; Drusch, M.; Moreno, J. FLEX: ESA’s Earth Explorer 8 candidate mission. Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2012, 7125–7128.

- Omia, E.; Bae, H.; Park, E.; Kim, M.S.; Baek, I.; Kabenge, I.; Cho, B.K. Remote Sensing in Field Crop Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review of Sensor Systems, Data Analyses and Recent Advances. Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Sethy, P.K.; Pandey, C.; Sahu, Y.K.; Behera, S.K. Hyperspectral imagery applications for precision agriculture - a systemic survey; Springer US, 2022; Vol. 81; ISBN 0123456789.

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for Remote Sensing with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Precision Agriculture. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 152–164. [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Fulton, J.; Shearer, S. An overview of current and potential applications of thermal remote sensing in precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 139, 22–32. [CrossRef]

- Segarra, J.; Buchaillot, M.L.; Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Remote Sensing for Precision Agriculture: Sentinel-2 Improved Features and Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 641. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Júnior, M.R.; Moreira, B.R. de A.; Carreira, V. dos S.; Brito Filho, A.L. de; Trentin, C.; Souza, F.L.P. de; Tedesco, D.; Setiyono, T.; Flores, J.P.; Ampatzidis, Y.; et al. Precision agriculture in the United States: A comprehensive meta-review inspiring further research, innovation, and adoption. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108993. [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Pádua, L.; Sousa, J.J.; Fernandes-Silva, A. Advancements in Remote Sensing Imagery Applications for Precision Management in Olive Growing: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1324. [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, J.; Langridge, J.; Avadí Ef, A.; Casajus, N.; Chaudhary, A.; Damour Hi, G.; Estrada-Carmona, N.; Jones, S.K.; Makowski, D.; Mitchell, M.; et al. Global review of meta-analyses reveals key data gaps in agricultural impact studies on biodiversity in croplands. BioRxiv 2024, 0–22.

- Khanal, S.; Kushal, K.C.; Fulton, J.P.; Shearer, S.; Ozkan, E. Remote sensing in agriculture—accomplishments, limitations, and opportunities. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1–29.

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Selsam, P.; Pause, M.; Bumberger, J. Monitoring vegetation- and geodiversity with remote sensing and traits. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2024, 382. [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Townsend, P.A. Remote Sensing of Plant Biodiversity; Cavender-Bares, J., Gamon, J.A., Townsend, P.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-33156-6.

- Lausch, A.; Bastian, O.; Klotz, S.; Leitão, P.J.; Jung, A.; Rocchini, D.; Schaepman, M.E.; Skidmore, A.K.; Tischendorf, L.; Knapp, S. Understanding and assessing vegetation health by in situ species and remote-sensing approaches. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1799–1809. [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Baade, J.; Bannehr, L.; Borg, E.; Bumberger, J.; Chabrilliat, S.; Dietrich, P.; Gerighausen, H.; Glässer, C.; Hacker, J.; et al. Linking Remote Sensing and Geodiversity and Their Traits Relevant to Biodiversity—Part I: Soil Characteristics. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2356. [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Schaepman, M.E.; Skidmore, A.K.; Truckenbrodt, S.C.; Hacker, J.M.; Baade, J.; Bannehr, L.; Borg, E.; Bumberger, J.; Dietrich, P.; et al. Linking the Remote Sensing of Geodiversity and Traits Relevant to Biodiversity—Part II: Geomorphology, Terrain and Surfaces. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3690. [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Schaepman, M.E.; Skidmore, A.K.; Catana, E.; Bannehr, L.; Bastian, O.; Borg, E.; Bumberger, J.; Dietrich, P.; Glässer, C.; et al. Remote Sensing of Geomorphodiversity Linked to Biodiversity—Part III: Traits, Processes and Remote Sensing Characteristics. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2279.

- Lausch, A.; Bannehr, L.; Berger, S.A.; Borg, E.; Bumberger, J. Monitoring Water Diversity and Water Quality with Remote Sensing and Traits. Remote Sens. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Haase, D.; Anderson, P.; Cortinovis, C.; Goodness, J.; Kendal, D.; Lausch, A.; McPhearson, T.; Sikorska, D.; Wellmann, T. What are the traits of a social-ecological system: towards a framework in support of urban sustainability. npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T.; Lausch, A.; Andersson, E.; Knapp, S.; Cortinovis, C.; Jache, J.; Scheuer, S.; Kremer, P.; Mascarenhas, A.; Kraemer, R.; et al. Remote sensing in urban planning: Contributions towards ecologically sound policies? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103921. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, J.; Haase, D.; Wellmann, T.; Lausch, A. Measuring spatio-temporal heterogeneity and interior characteristics of green spaces in urban neighborhoods: A new approach using gray level co-occurrence matrix. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158608. [CrossRef]

- Roilo, S.; Paulus, A.; Alarcón-Segura, V.; Kock, L.; Beckmann, M.; Klein, N.; Cord, A.F. Quantifying agricultural land-use intensity for spatial biodiversity modelling: implications of different metrics and spatial aggregation methods. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 55. [CrossRef]

- Erb, K.H.; Haberl, H.; Jepsen, M.R.; Kuemmerle, T.; Lindner, M.; Müller, D.; Verburg, P.H.; Reenberg, A. A conceptual framework for analysing and measuring land-use intensity. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Diogo, V.; Helfenstein, J.; Mohr, F.; Varghese, V.; Debonne, N.; Levers, C.; Swart, R.; Sonderegger, G.; Nemecek, T.; Schader, C.; et al. Developing context-specific frameworks for integrated sustainability assessment of agricultural intensity change: An application for Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Dullinger, I.; Essl, F.; Moser, D.; Erb, K.; Haberl, H.; Dullinger, S. Biodiversity models need to represent land-use intensity more comprehensively. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 924–932. [CrossRef]

- Rascher, U.; Alonso, L.; Burkart, A.; Cilia, C.; Cogliati, S.; Colombo, R.; Damm, A.; Drusch, M.; Guanter, L.; Hanus, J.; et al. Sun-induced fluorescence - a new probe of photosynthesis: First maps from the imaging spectrometer HyPlant. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 4673–4684. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.H.; Colombo, R.; Middleton, E.M.; Rascher, U.; van der Tol, C.; Nedbal, L.; Goulas, Y.; Pérez-Priego, O.; Damm, A.; Meroni, M.; et al. Remote sensing of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) in vegetation: 50 years of progress. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111177. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Hardy, E.E.; Roach, J.T.; Witmer, R.E. A Land Use And Land Cover Classification System For Use With Remote Sensor Data; vVASHINGTON, 1976; Vol. 964;.

- Adewumi, J.R.; Akomolafe, J.K.; Ajibade, F.O.; Fabeku, B.B. Application of GIS and Remote Sensing Technique to Change Detection in Land Use/Land Cover Mapping of Igbokoda, Ondo State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Process Eng. 1970, 3. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E. Global Vegetation and Land Use: New High-Resolution Data Bases for Climate Studies. J. Clim. Appl. Meteorol. 1983, 22, 474–487. [CrossRef]

- Masek, J.G.; Wulder, M.A.; Markham, B.; McCorkel, J.; Crawford, C.J.; Storey, J.; Jenstrom, D.T. Landsat 9: Empowering open science and applications through continuity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 248, 111968. [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Copernicus the European Union’s Earth observation programme. https://www.copernicus.eu. Accessed 02. 08 2024.

- Rocchini, D.; Santos, M.J.; Ustin, S.L.; Féret, J.; Asner, G.P.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Dalponte, M.; Feilhauer, H.; Foody, G.M.; Geller, G.N.; et al. The Spectral Species Concept in Living Color. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2022, 127, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Maudet, S.; Brusse, T.; Poss, B.; Caro, G.; Marrec, R. Estimating landscape intensity through farming practices: An integrative and flexible approach to modelling farming intensity from field to landscape. Ecol. Modell. 2025, 501, 110975. [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A. Menz, G. Bedeutung der Integration linearer Elemente in Fernerkundungsdaten zur Berechnung von Landschaftsstrukturmaßen. Photogramm. Fernerkundung Geoinf. 1999, 3, 185–194.

- Lausch, A.; Herzog, F. Applicability of landscape metrics for the monitoring of landscape change: Issues of scale, resolution and interpretability. Ecol. Indic. 2002, 2.

- Billeter, R.; Liira, J.; Bailey, D.; Bugter, R.; Arens, P.; Augenstein, I.; Aviron, S.; Baudry, J.; Bukacek, R.; Burel, F.; et al. Indicators for biodiversity in agricultural landscapes: A pan-European study. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 45. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, F.; Diogo, V.; Helfenstein, J.; Debonne, N.; Dimopoulos, T.; Dramstad, W.; García-Martín, M.; Hernik, J.; Herzog, F.; Kizos, T.; et al. Why has farming in Europe changed? A farmers’ perspective on the development since the 1960s. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2023, 23, 156. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.E.; Collins, S.J.; Crowe, S.; Girard, J.; Naujokaitis-Lewis, I.; Smith, A.C.; Lindsay, K.; Mitchell, S.; Fahrig, L. Effects of farmland heterogeneity on biodiversity are similar to—or even larger than—the effects of farming practices. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 288, 106698. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Kattge, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Wright, I.J.; Lavorel, S.; Dray, S.; Reu, B.; Kleyer, M.; Wirth, C.; Colin Prentice, I.; et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 2016, 529, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Joswig, J.S.; Wirth, C.; Schuman, M.C.; Kattge, J.; Reu, B.; Wright, I.J.; Sippel, S.D.; Rüger, N.; Richter, R.; Schaepman, M.E.; et al. Climatic and soil factors explain the two-dimensional spectrum of global plant trait variation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 36–50. [CrossRef]

- Picado, E.F.; Romero, K.F. Mapping Spatial Variability of Sugarcane Foliar Nitrogen , Phosphorus , Potassium and Chlorophyll Concentrations Using Remote Sensing. Geomatics 2025, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Candiani, G.; Tagliabue, G.; Panigada, C.; Verrelst, J.; Picchi, V.; Rivera Caicedo, J.P.; Boschetti, M. Evaluation of Hybrid Models to Estimate Chlorophyll and Nitrogen Content of Maize Crops in the Framework of the Future CHIME Mission. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1792. [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Rivera, J.P.; Veroustraete, F.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Camps-Valls, G.; Moreno, J. Experimental Sentinel-2 LAI estimation using parametric, non-parametric and physical retrieval methods - A comparison. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 108, 260–272.

- Berger, K.; Verrelst, J.; Féret, J.-B.; Hank, T.; Wocher, M.; Mauser, W.; Camps-Valls, G. Retrieval of aboveground crop nitrogen content with a hybrid machine learning method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 92, 102174. [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, R.; Daraio, M.; Guarini, R.; Longo, F.; Lorusso, R.; Dini, L.; Lopinto, E. Prisma Mission Status and Perspective. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE, 2019; pp. 4503–4506.

- Matsunaga, T.; Iwasaki, A.; Tachikawa, T.; Tanii, J.; Kashimura, O.; Mouri, K.; Inada, H.; Tsuchida, S.; Nakamura, R.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Hyperspectral Imager Suite (HISUI): Its Launch and Current Status. Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2020, 3272–3273.

- Feingersh, T.; Dor, E. Ben SHALOM – A Commercial Hyperspectral Space Mission. In Optical Payloads for Space Missions; Wiley, 2015; pp. 247–263.

- Delloye, C.; Weiss, M.; Defourny, P. Retrieval of the canopy chlorophyll content from Sentinel-2 spectral bands to estimate nitrogen uptake in intensive winter wheat cropping systems. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 245–261. [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Verhoef, W.; Baret, F.; Bacour, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Asner, G.P.; François, C.; Ustin, S.L. PROSPECT + SAIL models: A review of use for vegetation characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S56–S66. [CrossRef]

- Lhotáková, Z.; Neuwirthová, E.; Potůčková, M.; Červená, L.; Hunt, L.; Kupková, L.; Lukeš, P.; Campbell, P.; Albrechtová, J. Mind the leaf anatomy while taking ground truth with portable chlorophyll meters. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1855. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, K.; Clulow, A.; Sibanda, M.; Gokool, S.; Naiken, V.; Mabhaudhi, T. Predicting the Chlorophyll Content of Maize over Phenotyping as a Proxy for Crop Health in Smallholder Farming Systems. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 518. [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Moreno, J.; Del Bello, U.; Franco, R.; Goulas, Y.; Huth, A.; Kraft, S.; Middleton, E.M.; Miglietta, F.; Mohammed, G.; et al. The FLuorescence EXplorer Mission Concept-ESA’s Earth Explorer 8. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 1273–1284.

- De Grave, C.; Verrelst, J.; Morcillo-Pallarés, P.; Pipia, L.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Amin, E.; Belda, S.; Moreno, J. Quantifying vegetation biophysical variables from the Sentinel-3/FLEX tandem mission: Evaluation of the synergy of OLCI and FLORIS data sources. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112101.

- Ač, A.; Malenovský, Z.; Olejníčková, J.; Gallé, A.; Rascher, U.; Mohammed, G. Meta-analysis assessing potential of steady-state chlorophyll fluorescence for remote sensing detection of plant water, temperature and nitrogen stress. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 168, 420–436. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.F.; Goulas, Y.; Huth, A.; Middleton, E.; Miglietta, F.; Mohammed, G.; Nedbal, L.; Rascher, U.; Verhoef, W.; Drusch, M. Very high spectral resolution imaging spectroscopy: The Fluorescence Explorer (FLEX) mission. Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2016, 2016-Novem, 264–267.

- Dong, N.; Prentice, I.C.; Wright, I.J.; Wang, H.; Atkin, O.K.; Bloomfield, K.J.; Domingues, T.F.; Gleason, S.M.; Maire, V.; Onoda, Y.; et al. Leaf nitrogen from the perspective of optimal plant function. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2585–2602. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Song, X.; Yang, G.; Du, X.; Mei, X.; Yang, X. Remote Sensing Monitoring of Rice and Wheat Canopy Nitrogen: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Conceição, L.A.; Lidon, F.C.; Maçãs, B. Remote Monitoring of Crop Nitrogen Nutrition to Adjust Crop Models: A Review. Agric. 2023, 13, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Arogoundade, A.M.; Mutanga, O.; Odindi, J.; Naicker, R. The role of remote sensing in tropical grassland nutrient estimation: a review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195. [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Z. Nitrogen monitoring and inversion algorithms of fruit trees based on spectral remote sensing: a deep review. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, F.; Fue, K.G.; Yu, K. Meta-Analysis Assessing Potential of Drone Remote Sensing in Estimating Plant Traits Related to Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Remote Sens. 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, S.; Vellingiri, G.; Sellaperumal, P.; Pandian, K.; Sivasankar, A.; Sangchul, H. Real-time nitrogen monitoring and management to augment N use efficiency and ecosystem sustainability–A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100466. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Kumar Khura, T.; Ahmad Parray, R.; Kushwaha, H.L.; Upadhyay, P.K.; Jha, A.; Patra, K.; Kushwah, A.; Kumar Prajapati, V. The use of destructive and nondestructive techniques in concrete nitrogen assessment in plants. J. Plant Nutr. 2024, 47, 2271–2294. [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, M.; Simic, A.; Verrelst, J.; Tian, Q.; Soleil, A.; Poku, H.; Rahman, A.; Processing, I.; Científic, P.; Val, U. De Optimizing Empirical and Hybrid Modeling for Advanced Canopy Chlorophyll and Nitrogen Retrieval Technique Using EnMAP Data. Environ. Challenges 2025, 18, 101114.

- Verrelst, J.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Reyes-Muñoz, P.; Morata, M.; Amin, E.; Tagliabue, G.; Panigada, C.; Hank, T.; Berger, K. Mapping landscape canopy nitrogen content from space using PRISMA data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 382–395. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Suarez, L.; Hornero, A.; Poblete, T.; Ryu, D.; Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Assessing plant traits derived from Sentinel-2 to characterize leaf nitrogen variability in almond orchards: modeling and validation with airborne hyperspectral imagery. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, L.; Sobeih, T.; Lappin, L.; Lee, M.A.; Howard, A.; Kisdi, A. The Self-Supervised Spectral–Spatial Vision Transformer Network for Accurate Prediction of Wheat Nitrogen Status from UAV Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xu, X.; Blacker, C.; Gaulton, R.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, M.; Yang, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. Estimation of Leaf Nitrogen Content in Rice Using Vegetation Indices and Feature Variable Optimization with Information Fusion of Multiple-Sensor Images from UAV. Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; King, K.W.; Johnson, L.; Francesconi, W.; Richards, P.; Baker, D.; Sharpley, A.N. Surface Runoff and Tile Drainage Transport of Phosphorus in the Midwestern United States. J. Environ. Qual. 2015, 44, 495–502. [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Krasilnikof, J.; Yannopoulos, S.; Kumar, R.; Deng, J.; Roccaro, P.; Mays, L.; Grismer, M.E.; Angelakis, A.N. The evolution of agricultural drainage from the earliest times to the present. Sustain. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, M.R.; Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Erb, K.; Verburg, P.H.; Haberl, H.; Vesterager, J.P.; Andrič, M.; Antrop, M.; Austrheim, G.; et al. Transitions in European land-management regimes between 1800 and 2010. Land use policy 2015, 49, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C. How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2014, 65, 934–941. [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Elsgaard, L.; Greve, M.H.; Gyldenkærne, S.; Hermansen, C.; Levin, G.; Wu, S.; Stisen, S. Water-table-driven greenhouse gas emission estimates guide peatland restoration at national scale. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 2387–2403. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.N., Dobrowolski, E.G.; Meyer, S.M.; Frey, J.W.; Allred, B.J. Delineation of tile-drain networks using thermal and multispectral imagery—Implications for water quantity and quality differences from paired edge- of-field sites. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 74, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, A.H.; Fensholt, R.; Looms, M.C.; Gominski, D.; Stisen, S.; Jepsen, M.R. Systematic review of the detection of subsurface drainage systems in agricultural fields using remote sensing systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 299, 108892. [CrossRef]

- Karbs, H.H. Subsurface Drainage Mapping By Airborne Infrared.; Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science, 1970; Vol. 18, pp. 10–18.

- Gökkaya, K.; Budhathoki, M.; Christopher, S.F.; Hanrahan, B.R.; Tank, J.L. Subsurface tile drained area detection using GIS and remote sensing in an agricultural watershed. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 108, 370–379. [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Jacobs, J.M.; Jia, X.; Kraatz, S. Identifying Subsurface Drainage using Satellite Big Data and Machine Learning via Google Earth Engine. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 8028–8045. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Xin, Q.; Tian, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, R. Structural Analysis and 3D Reconstruction of Underground Pipeline Systems Based on LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.K.; Ji, J.; Song, H. Subsurface drainage pipe detection using an ensemble learning approach and aerial images. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108455. [CrossRef]

- Allred, B.; Eash, N.; Freeland, R.; Martinez, L.; Wishart, D.B. Effective and efficient agricultural drainage pipe mapping with UAS thermal infrared imagery: A case study. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 197, 132–137. [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.M.; Becker, R.H.; Doro, K.O. Locating Drainage Tiles at a Wetland Restoration Site within the Oak Openings Region of Ohio, United States Using UAV and Land Based Geophysical Techniques. Wetlands 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, G.K.; Tang, B.; Wen, Q.; Tan, R.; Huang, Y. Regional scale terrace mapping in fragmented mountainous areas using multi-source remote sensing data and sample purification strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 925, 171366. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Song, H.; Wang, X. Mapping the terraces on the Loess Plateau based on a deep learning-based model at 1.89 m resolution. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Rui, X.; Xie, W.; Xu, X.; Wei, W. Research on Automatic Identification Method of Terraces on the Loess Plateau Based on Deep Transfer Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Na, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, K.; Fu, Y.; Li, F. Evaluation of three different machine learning methods for object-based artificial terrace mapping—a case study of the loess plateau, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xiong, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Wei, H.; Tang, G. Terraces mapping by using deep learning approach from remote sensing images and digital elevation models. Trans. GIS 2021, 25, 2438–2454. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Dong, J.; Cadisch, G.; Wang, M.; Kou, W.; Xu, J.; Xiao, X.; Abbas, S. Comparison of pixel- and object-based approaches in phenology-based rubber plantation mapping in fragmented landscapes. Remote Sens. 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Blickensdörfer, L.; Schwieder, M.; Pflugmacher, D.; Nendel, C.; Erasmi, S.; Hostert, P. Mapping of crop types and crop sequences with combined time series of Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 data for Germany. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269. [CrossRef]

- Godone, D.; Giordan, D.; Baldo, M. Rapid mapping application of vegetated terraces based on high resolution airborne lidar. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk 2018, 9, 970–985. [CrossRef]

- Le Vot, T.; Cohen, M.; Nowak, M.; Passy, P.; Sumera, F. Resilience of Terraced Landscapes to Human and Natural Impacts: A GIS-Based Reconstruction of Land Use Evolution in a Mediterranean Mountain Valley. Land 2024, 13, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Oechsle, A.; Johanson, E.; Nagarajan, S.; Martínez, V. In between the Sites: Understanding Late Holocene Manteño Agricultural Contexts in the Chongón-Colonche Mountains of Coastal Ecuador through UAV-Lidar and Excavation. J. F. Archaeol. 2025, 50, 42–59. [CrossRef]

- Lozić, E. Application of airborne lidar data to the archaeology of agrarian land use. The case study of the early medieval microregion of bled (Slovenia). Remote Sens. 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Masini, N.; Gizzi, F.T.; Biscione, M.; Fundone, V.; Sedile, M.; Sileo, M.; Pecci, A.; Lacovara, B.; Lasaponara, R. Medieval archaeology under the canopy with LiDAR. the (Re)discovery of a medieval fortified settlement in southern Italy. Remote Sens. 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Baker, J.C.A.; Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 2023, 615, 270–275. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P. V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S. V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science (80-. ). 2013, 342, 850–853. [CrossRef]

- Ponvert-Delisles Batista, D.R.; Estrada-Medina, H.; Gijón-Yescas, G.N.; Álvarez-Rivera, O.O. Land covers analyses during slash and burn agriculture by using multispectral imagery obtained with Unattended Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2021, 24. [CrossRef]

- Lechner, A.M.; Foody, G.M.; Boyd, D.S. Applications in Remote Sensing to Forest Ecology and Management. One Earth 2020, 2, 405–412. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, E.A.; Caccetta, P.; Lowell, K.; Mitchell, A.; Zhou, Z.S.; Held, A.; Milne, T.; Tapley, I. SAR and optical remote sensing: Assessment of complementarity and interoperability in the context of a large-scale operational forest monitoring system. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 156, 335–348. [CrossRef]

- Ballère, M.; Bouvet, A.; Mermoz, S.; Le Toan, T.; Koleck, T.; Bedeau, C.; André, M.; Forestier, E.; Frison, P.L.; Lardeux, C. SAR data for tropical forest disturbance alerts in French Guiana: Benefit over optical imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252. [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, Y.; Mantas, V.M.; Pereira, A.J.S.C. Improving tropical deforestation detection through using photosynthetic vegetation time series – (PVts-β). Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shu, L.; Han, R.; Yang, F.; Gordon, T.; Wang, X.; Xu, H. A Survey of Farmland Boundary Extraction Technology Based on Remote Sensing Images. Electron. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Tyukavina, A.; Zalles, V.; Khan, A.; Song, X.P.; Pickens, A.; Shen, Q.; Cortez, J. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 19–28. [CrossRef]

- Bégué, A.; Arvor, D.; Bellon, B.; Betbeder, J.; de Abelleyra, D.; Ferraz, R.P.D.; Lebourgeois, V.; Lelong, C.; Simões, M.; Verón, S.R. Remote sensing and cropping practices: A review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Preidl, S.; Lange, M.; Doktor, D. Introducing APiC for regionalised land cover mapping on the national scale using Sentinel-2A imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111673. [CrossRef]

- Baessler, C.; Klotz, S. Effects of changes in agricultural land-use on landscape structure and arable weed vegetation over the last 50 years. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 115, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, T. Calculating the Interspersion and Juxtaposition Rates for Saint Clair Flats State Wildlife Area by, 2022.

- Uuemaa, E.; Antrop, M.; Roosaare, J.; Marja, R.; Mander, Ü. Landscape metrics and indices: An overview of their use in landscape research. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2009, 3, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, T. Shape-describing indices for agricultural field plots and their relationship to operational efficiency. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 98, 252–259. [CrossRef]

- Griffel, L.M.; Vazhnik, V.; Hartley, D.S.; Hansen, J.K.; Roni, M. Agricultural field shape descriptors as predictors of field efficiency for perennial grass harvesting: An empirical proof. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168. [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.A.L.; Subburayalu, S.K. Correction: Modified shape index for object-based random forest image classification of agricultural systems using airborne hyperspectral datasets. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0222474. [CrossRef]

- Blüthgen, N.; Dormann, C.F.; Prati, D.; Klaus, V.H.; Kleinebecker, T.; Hölzel, N.; Alt, F.; Boch, S.; Gockel, S.; Hemp, A.; et al. A quantitative index of land-use intensity in grasslands: Integrating mowing, grazing and fertilization. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2012, 13, 207–220. [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Balkenhol, N.; Carter, G.A.; Foody, G.M.; Gillespie, T.W.; He, K.S.; Kark, S.; Levin, N.; Lucas, K.; Luoto, M.; et al. Remotely sensed spectral heterogeneity as a proxy of species diversity: Recent advances and open challenges. Ecol. Inform. 2010, 5, 318–329. [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Marcantonio, M.; Ricotta, C. Measuring Rao’s Q diversity index from remote sensing: An open source solution. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 72, 234–238. [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Bacaro, G.; Chirici, G.; Da Re, D.; Feilhauer, H.; Foody, G.M.; Galluzzi, M.; Garzon-Lopez, C.X.; Gillespie, T.W.; He, K.S.; et al. Remotely sensed spatial heterogeneity as an exploratory tool for taxonomic and functional diversity study. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 983–990. [CrossRef]

- Steele-Dunne, S.C.; McNairn, H.; Monsivais-Huertero, A.; Judge, J.; Liu, P.W.; Papathanassiou, K. Radar Remote Sensing of Agricultural Canopies: A Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 2249–2273. [CrossRef]

- Howison, R.A.; Piersma, T.; Kentie, R.; Hooijmeijer, J.C.E.W.; Olff, H. Quantifying landscape-level land-use intensity patterns through radar-based remote sensing. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 1276–1287.

- Herrero-Huerta, M.; Bucksch, A.; Puttonen, E.; Rainey, K.M. Canopy roughness: A new phenotypic trait to estimate aboveground biomass from unmanned aerial system. Plant Phenomics 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, J.G.; Kustas, W.P.; Nieto, H.; Prueger, J.H.; Hipps, L.E.; McKee, L.G.; Gao, F.; Los, S. Influence of wind direction on the surface roughness of vineyards. Irrig. Sci. 2019, 37, 359–373. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gaurav, K.; Rai, A.K.; Beg, Z. Machine learning to estimate surface roughness from satellite images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Panciera, R.; Tanase, M.A.; Lowell, K.; Hacker, J.M.; Walker, J.P. Estimation of soil surface roughness of agricultural soils using airborne LiDAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Mahlayeye, M.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Nelson, A. Cropping Patterns of Annual Crops: A Remote Sensing Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Hu, X.; Chen, C.; Tang, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhu, X.; Yan, C.; Jian, Z. Maps of cropping patterns in China during 2015–2021. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M.; Bégué, A.; Guillaume, S.; Martiné, J.F. Integrating SPOT-5 time series, crop growth modeling and expert knowledge for monitoring agricultural practices - The case of sugarcane harvest on Reunion Island. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2052–2061.

- Maponya, M.G.; van Niekerk, A.; Mashimbye, Z.E. Pre-harvest classification of crop types using a Sentinel-2 time-series and machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105164. [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, I.; Sheoran, H.S.; Roohi; Dahiya, G.; Sihag, P. Analysis of sentinel-1 data for regional crop classification: a multi-data approach for rabi crops of district Hisar (Haryana). J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2020, 12, 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Orynbaikyzy, A.; Gessner, U.; Conrad, C. Crop type classification using a combination of optical and radar remote sensing data: a review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 6553–6595. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, X.; Wei, L.; Zhang, L. A robust spectral-spatial approach to identifying heterogeneous crops using remote sensing imagery with high spectral and spatial resolutions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 239, 111605. [CrossRef]

- Nigam, R.; Tripathy, R.; Dutta, S.; Bhagia, N.; Nagori, R.; Chandrasekar, K.; Kot, R.; Bhattacharya, B.K.; Ustin, S. Crop type discrimination and health assessment using hyperspectral imaging. Curr. Sci. 2019, 116, 1108–1123. [CrossRef]

- Prins, A.J.; Van Niekerk, A. Crop type mapping using LiDAR, Sentinel-2 and aerial imagery with machine learning algorithms. Geo-Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, 24, 1–13.

- He, T.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, W.; Zhai, G.; Fang, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C. Terend and potential enhancement of cropping intensity. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109777. [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Han, L.; Yao, L.; Faye, B. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Evolution of Grain Cropping Patterns in Northeast China: Insights from Remote Sensing and Spatial Overlay Analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1443. [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, K.R.; Kundu, N.; Ray, S.S.; Panigrahy, S.; Parihar, J.S. Cropping Systems Dynamics in the Lower Gangetic Plains of India using Geospatial Technologies. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXVIII-8/, 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, K.R.; More, R.S.; Jain, N.K.; Panigrahy, S.; Parihar, J.S. Mapping of rice-cropping pattern and cultural type using remote-sensing and ancillary data: a case study for South and Southeast Asian countries. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 6008–6030. [CrossRef]

- Aduvukha, G.R.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Sichangi, A.W.; Makokha, G.O.; Landmann, T.; Mudereri, B.T.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Dubois, T. Cropping pattern mapping in an agro-natural heterogeneous landscape using sentinel-2 and sentinel-1 satellite datasets. Agric. 2021, 11, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Nendel, C.; Hostert, P. Intra-annual reflectance composites from Sentinel-2 and Landsat for national-scale crop and land cover mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 220, 135–151. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, B.; Zeng, H.; He, G.; Liu, C.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Nabil, M.; Tian, F.; Bofana, J.; et al. GCI30: A global dataset of 30m cropping intensity using multisource remote sensing imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4799–4817. [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Feilhauer, H.; Kühn, I.; Doktor, D. Mapping land-use intensity of grasslands in Germany with machine learning and Sentinel-2 time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 277, 112888. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Nendel, C.; Pickert, J.; Hostert, P. Towards national-scale characterization of grassland use intensity from integrated Sentinel-2 and Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 238, 111124. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Bossdorf, O.; Gockel, S.; Hänsel, F.; Hemp, A.; Hessenmöller, D.; Korte, G.; Nieschulze, J.; Pfeiffer, S.; Prati, D.; et al. Implementing large-scale and long-term functional biodiversity research: The Biodiversity Exploratories. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2010, 11, 473–485. [CrossRef]

- Bartold, M.; Kluczek, M.; Wróblewski, K.; Dąbrowska-Zielińska, K.; Goliński, P.; Golińska, B. Mapping management intensity types in grasslands with synergistic use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellite images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Sousa Júnior, V. de P.; Sparacino, J.; Espindola, G.M. de; Assis, R.J.S. de Carbon Biomass Estimation Using Vegetation Indices in Agriculture–Pasture Mosaics in the Brazilian Caatinga Dry Tropical Forest. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2023, 12, 354. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Remote sensing of above-ground biomass. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1–8. [CrossRef]