1. Introduction

Infectious diseases pose a substantial challenge to global animal health, particularly in the context of intensive livestock farming [

1]. Among these, herpesvirus infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) represent significant public health concerns worldwide. These viruses are responsible for a wide range of conditions, from mild cold sores to severe complications such as encephalitis, organ failure, and cancer [

2]. Despite extensive research, current diagnostic and therapeutic strategies remain insufficient, largely due to the viruses’ ability to establish latency, evade immune responses, and, in some cases, develop resistance to antiviral treatments. This highlights the urgent need for innovative approaches to enhance detection, deepen our understanding of viral transmission, and identify novel therapeutic targets [

3,

4,

5].

In the context of veterinary medicine, herpesvirus-associated diseases like Marek’s Disease (MD) are particularly impactful. MD, caused by Marek’s disease virus (MDV), is a highly contagious and oncogenic alphaherpesvirus that affects poultry, especially chickens [

6,

7]. First described in the early 20th century by Hungarian veterinarian József Marek, the disease manifests in various forms, including paralysis, immunosuppression, and lymphomas, directly impairing weight gain and egg production [

7,

8]. Indirectly, it contributes to economic burdens through the costs of vaccination and biosecurity measures, with estimated global losses ranging from

$1 to

$2 billion annually [

9,

10]. Although the introduction of vaccines in the 1970s significantly reduced clinical incidence, MDV continues to evolve under vaccine-induced selection pressure, resulting in increasingly virulent strains, including very virulent plus (vv+MDV) pathotypes. These developments underscore the persistent challenge of controlling MDV and the need for adaptive, forward-looking disease management strategies [

11,

12].

Concurrently, the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has undergone rapid transformation, from theoretical computer science models to practical tools in medicine, finance, and agriculture [

13,

14,

15]. In healthcare, AI is now widely used for diagnostic imaging, predictive modeling, and drug discovery [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Encompassing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and data mining techniques, AI can analyze vast, complex datasets to detect patterns, generate predictions, and optimize decision-making [

18,

19]. In veterinary medicine, AI is beginning to redefine how diseases are diagnosed, monitored, and controlled. Applications include automated diagnostic systems, outbreak forecasting, genomic analysis, and optimization of breeding programs. As such, AI holds the potential to revolutionize infectious disease management in animals [

20].

This review explores the intersection of AI and veterinary infectious disease management, with a particular focus on MDV. We aim to provide a comprehensive overview of how AI technologies can enhance our understanding of MDV pathogenesis, enable early detection and outbreak control, and support the development of effective and sustainable intervention strategies. By enabling faster diagnostics, more accurate predictions, and improved resource allocation, AI can serve as a cornerstone in modern veterinary epidemiology.

2. Overview of Marek’s Disease Virus (MDV)

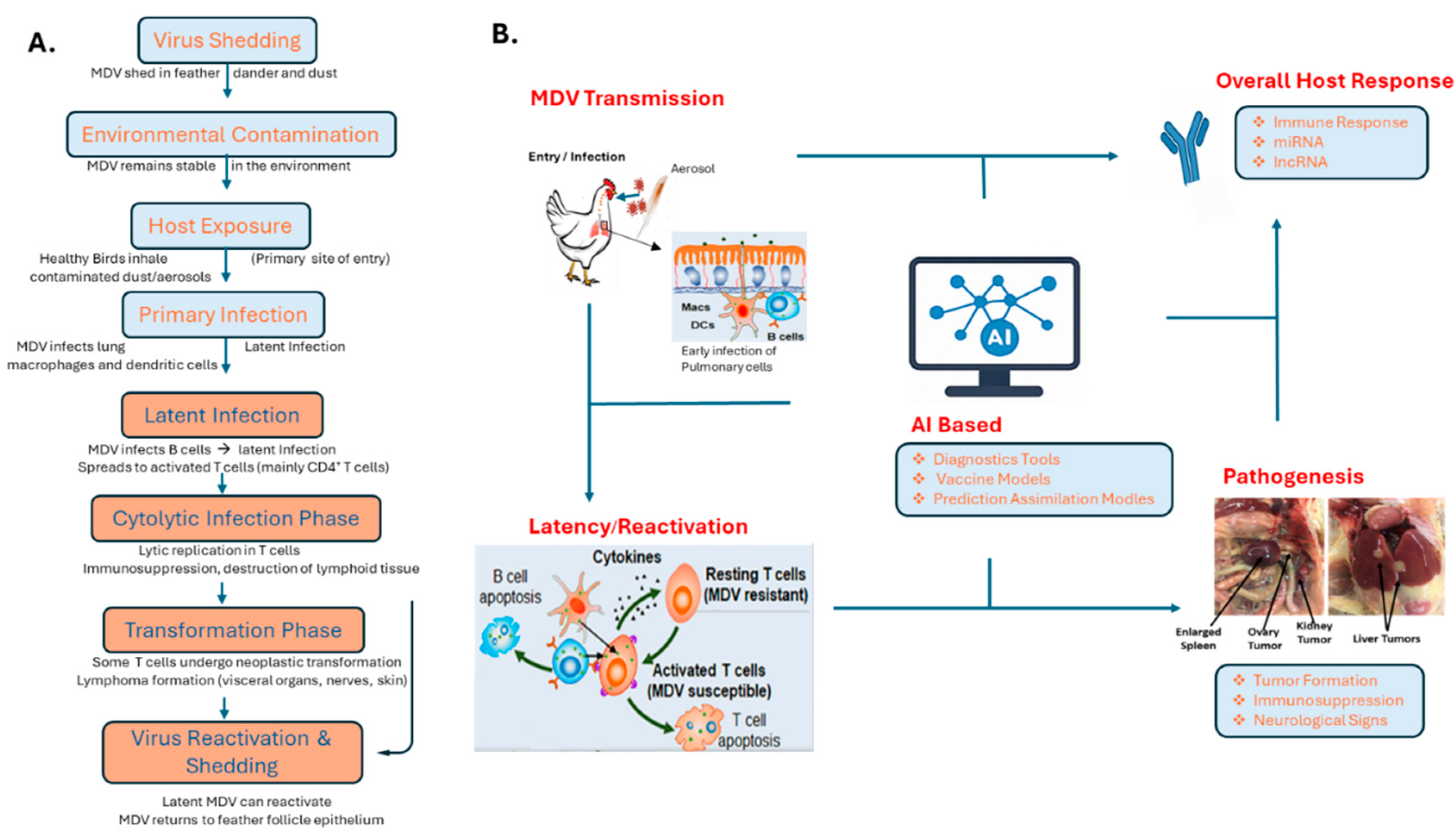

MDV is an alphaherpesvirus that primarily affects poultry, especially chickens, and is renowned for its oncogenic properties [

21,

22]. The virus spreads mainly through the respiratory route, either via direct bird-to-bird contact or indirectly through the inhalation of infectious dust and dander. Infection begins in the lungs, where pulmonary macrophages and B lymphocytes capture the virus and transport it to lymphoid organs. This leads to the activation of CD4+ T cells, which subsequently become the primary target cells during the productive lytic phase of infection (

Figure 1A) [

22,

23].

Around 10–14 days post-infection, following a robust immune response, MDV establishes a lifelong latent infection in T cells. Some of these latently infected T cells can undergo malignant transformation, leading to cancer, although this transformation represents a dead end for viral transmission [

21,

22]. For successful spread within a population, MDV is transported by infected immune cells to feather follicle epithelial (FFE) skin cells, where full viral replication occurs (

Figure 1A,B). This results in the assembly of infectious virus particles and their release into the environment [

23]. Clinically, MDV infection presents with a range of symptoms including paralysis, ocular changes, immunosuppression, and the development of T-cell lymphomas. Its ability to cause lymphoproliferative disorders and immune dysfunction underscores its significance in poultry health and veterinary medicine [

21,

22,

23,

24].

The economic impact of MD is substantial and global. Recent reports estimate that annual losses due to MDV exceed US

$1–2 billion worldwide. These losses stem from direct mortality, reduced growth rates, decreased egg production, increased carcass condemnation at slaughter, and the financial burden of vaccination and biosecurity measures [

9,

10]. The emergence of increasingly virulent MDV pathotypes such as very virulent (vvMDV) and very virulent plus (vv+MDV), has further complicated control efforts, as these strains can evade the immunity conferred by current vaccines [

11,

12].

Despite the widespread implementation of vaccination strategies since the 1970s, MDV continues to pose a significant threat [

25,

26,

27]. Existing vaccines, including HVT (herpesvirus of turkeys), Rispens (CVI988), and MD-Vac (monovalent live virus), provide clinical protection but do not prevent infection or viral shedding [

28]. This non-sterilizing immunity creates conditions favorable to the evolution of more virulent strains, a concern highlighted by Read et al. (2015) [

27]. The use of such vaccines has altered the virus–host dynamic and raised questions about the long-term sustainability of current control measures [

28].

Recent surveillance data show regional variability in MDV prevalence. In developed poultry production systems with strict vaccination and biosecurity protocols, the incidence of clinical MD has declined but not been eradicated. In contrast, areas with poor vaccination coverage or inadequate administration techniques continue to report higher rates of infection [

29,

30,

31]. Additionally, diagnosing MDV remains a challenge due to its clinical similarities with other lymphoproliferative diseases such as avian leukosis and reticuloendotheliosis [

33,

34]. Molecular diagnostic tools, including real-time PCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS), have become crucial for accurate detection and surveillance; however, their application remains limited in low-resource settings [

34,

35].

Given these challenges, it is firmly established that controlling MDV requires a multi-faceted approach, encompassing robust surveillance, improved diagnostics, and innovative technologies. Among these, AI holds significant promise [

36,

37]. By integrating complex datasets, recognizing patterns, and predicting outbreaks or vaccine failures, AI could become a powerful tool in the ongoing battle against MDV.

3. Role of AI in Infectious Disease Research

3.1. Disease Surveillance and Outbreak Prediction

Understanding the transmission dynamics of herpesviruses remains a significant challenge due to their latent nature and asymptomatic shedding [

38]. AI-driven epidemiological models, such as agent-based simulations and ML classifiers, offer valuable insights into how herpesviruses spread within populations [

39,

40]. These models can incorporate a wide range of variables, including environmental conditions, host behavior, and genetic predispositions, to predict outbreaks and identify at-risk populations [

40].

AI also plays a crucial role in modeling the effects of interventions such as vaccination programs and antiviral treatments [

39,

41]. By simulating various scenarios, these models can provide evidence-based guidance on how public health strategies may reduce herpesvirus transmission, particularly in high-risk groups such as immunocompromised individuals [

41,

42]. One of the most transformative applications of AI in infectious disease management is its capacity for real-time disease surveillance and outbreak prediction [

43]. Supervised ML algorithms, including random forests, support vector machines (SVM), and gradient boosting, have been employed to analyze large datasets encompassing climatic, environmental, geographic, and host-specific variables. For instance, features such as temperature, humidity, flock density, and movement patterns can serve as predictive indicators [

43,

44]. Musa et al. (2024) demonstrated the use of mathematical and AI Model techniques in predicting avian influenza outbreaks using key factors demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and ecological variables [

46]. These methodologies can be adapted for MDV surveillance using farm-level data, including vaccination schedules, bird mortality rates, and biosensor outputs.

In poultry farming, sensors continuously collect real-time data on parameters such as temperature, humidity, ammonia levels, and feeding behavior [

47]. AI models can process these data streams to detect deviations from normal patterns, which may signal the early onset of an outbreak. Time-series models such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are particularly effective for this purpose [

48]. For example, Cuan et al. (2022) proposed a new method called “the Deep Poultry Vocalization Network (DPVN)” for the early detection of Newcastle disease based on poultry vocalizations [

49]. The method combines multi-window spectral subtraction and high-pass filtering to reduce noise interference and achieved high prediction accuracy within days post-infection. Similar approaches can also be applied to MDV, given appropriate training data.

Another promising advancement is the integration of AI with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for spatial disease modeling. Predictive mapping powered by AI can identify high-risk zones and inform targeted control measures. This spatial intelligence supports the implementation of focused vaccination efforts and the enhancement of biosecurity protocols in vulnerable areas. For instance, GIS-based reinforcement learning approaches have been utilized to predict disease transmission patterns, aiding in the development of effective intervention strategies [

50].

3.2. AI for Diagnostic Imaging, Molecular Analysis and Pattern Recognition

AI is rapidly transforming the landscape of diagnostic imaging and molecular analysis, particularly in the detection and monitoring of herpesvirus infections. With advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS), AI algorithms can now analyze viral genomes to detect herpesvirus strains and mutations that may influence treatment response [

51,

52]. By evaluating genetic sequences, AI can identify novel variants and track viral evolution, providing insights into changes that may impact pathogenicity or antiviral resistance [

53,

54].

Traditional diagnostic methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological assays are widely used for herpesvirus detection. However, these approaches can be time-consuming and may miss infections in latent or asymptomatic stages [

55]. AI-driven tools, particularly ML models, enhance the sensitivity and speed of diagnostics by integrating and analyzing molecular and imaging data [

53,

54]. In addition, AI algorithms can analyze clinical and diagnostic images such as skin lesions or neurological scans (e.g., MRI and CT) to detect herpesvirus-induced tissue damage. DL models, a subset of AI, are particularly effective at processing large datasets of medical images to identify patterns indicative of viral infection [

57]. Similarly, AI-based interpretation of blood samples, genomic sequences, and PCR data can support earlier and more accurate diagnoses, even in cases with minimal clinical symptoms [

52].

In infectious disease diagnostics, image-based evaluations such as gross pathology, histopathology, and radiography remain fundamental. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), a DL technique, have shown exceptional performance in medical and veterinary image analysis [

58,

59]. These models can be trained to identify subtle yet clinically significant differences between infected and healthy tissue. For MDV, which often manifests as peripheral nerve enlargement and lymphoproliferative lesions in visceral organs [

21], AI-assisted image analysis can greatly enhance diagnostic accuracy (

Figure 2). For example, digital histopathological slides can be processed by CNNs to quantify lesion severity and distribution. Such as Liu et al. (2019) investigated histologic findings and viral antigen distribution in layer hens naturally coinfected with J avian leukosis virus (ALV-J), MDV, and reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV). Their study utilized fluorescence multiplex immunohistochemistry staining to reveal co-expression of viral antigens in the same tissues and even the same cells, highlighting the complexity of such infections and the potential utility of advanced image analysis techniques in diagnosis [

60]. This suggests that AI-driven image analysis, such as CNNs, could be instrumental in quantifying lesion severity and distribution in MDV, enhancing diagnostic accuracy (

Figure 2).

Additionally, AI-enhanced video analytics is emerging as a valuable tool for poultry health monitoring. Video data from flocks can be analyzed to detect subtle changes in behavior or locomotion, such as reduced movement or abnormal gait, which may precede visible clinical symptoms. Recently, Zarrat Ehsan and Mohtavipour (2024) introduced

Broiler-Net, a deep convolutional framework designed for real-time analysis of broiler behavior in cage-free poultry houses [

61]. The system detects abnormalities such as inactivity and huddling behavior, enabling timely interventions to maintain flock health and productivity. These algorithms support early identification of at-risk birds and contribute to both disease surveillance and animal welfare management.

3.3. Genomic and Pathogen Evolution Studies

Genomics is a field where AI has had a particularly transformative impact. NGS-technologies produce vast datasets that require advanced analytical tools for meaningful interpretation [

51,

62]. AI models particularly unsupervised clustering algorithms and deep autoencoders are capable of detecting patterns in MDV genomic sequences that correlate with virulence, immune evasion, and vaccine resistance [

63,

64]. ML techniques have been employed to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with pathogenicity. For example, DL tools such as DeepVariant and TensorFlow-based frameworks have been used to annotate viral genomes and predict the functional consequences of genetic variations [

65,

66]. In the context of MDV, these tools hold promise for detecting the emergence of virulent strains earlier than traditional surveillance methods [

67]. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques also play a significant role in genomic and pathogen evolution studies (

Figure 2). NLP can extract structured data from unstructured sources, including research articles, diagnostic reports, and epidemiological records [

68]. Tools such as BioBERT and SciSpacy enable automated literature mining, accelerating the development of hypotheses related to MDV pathogenesis and control strategies [

69,

70].

4. AI Applications Specific to Marek’s Disease Virus

AI applications tailored specifically to MDV are beginning to emerge in both research and commercial poultry operations. These applications aim to provide early disease detection, improve vaccine strategies, enhance breeding programs, and ultimately reduce the economic and animal health burden associated with MDV [

67,

71].

4.1. Predictive Modeling of Virulence and Vaccine Breaks

AI-driven predictive models are increasingly being used to forecast the emergence of more virulent MDV strains and potential vaccine escape events. One notable example is the application of ML algorithms to analyze viral genome sequences from field isolates. For instance, a study by You et al. (2020) used random forest classifiers trained on MDV genomic data to predict virulence levels with over 90% accuracy. The model incorporated genomic markers linked to the Meq oncogene and polymorphisms in the ICP4 gene, both of which are associated with virulence and immune evasion [

72].

These models can also incorporate field data such as outbreak reports, vaccine strain usage, and farm-level mortality records, to flag regions or farms at risk for vaccine breaks. Tools like XGBoost and LightGBM are used due to their capacity to handle heterogeneous data inputs and highlight key predictive features [

73,

74]. These insights support regulatory agencies and vaccine producers in adapting immunization strategies and updating vaccine strains in real-time [

75].

4.2. Early Detection Using Behavioral Data

Behavioral monitoring through AI is gaining traction in commercial poultry settings. Real-time video analytics and wearable sensors track parameters like locomotion, feeding frequency, vocalizations, and thermal imaging data. AI models, particularly CNNs and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, process these data streams to detect early deviations from baseline behavior [

76]. In a case study by Lee et al. (2022), researchers used a DL framework to analyze gait patterns in broiler chickens infected with MDV. The system achieved an 87% accuracy in identifying subclinical infections three days before clinical signs were evident. Early detection allowed farm managers to isolate affected birds, adjust biosecurity protocols, and limit within-flock transmission [

77]. These systems not only support disease surveillance but also enhance animal welfare monitoring by enabling real-time intervention in response to stress or discomfort, which often precede overt clinical signs [

78].

4.3. AI in Understanding MDV Pathogenesis

MDV exhibits several features that make their pathogenesis unique, including their ability to establish lifelong latency and periodically reactivate in response to various stimuli. These properties present significant obstacles to controlling MDV transmission. AI offers an unprecedented opportunity to explore the intricate mechanisms of infection, latency, and reactivation through large-scale data analysis, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling.

Viral Entry and Replication: AI techniques, particularly deep learning, are increasingly being applied to study the interactions between herpesviruses and host cells. Herpesviruses, including MDV, enter host cells through surface receptor binding, followed by membrane fusion and nuclear genome replication [

79]. Understanding these processes is essential for identifying effective therapeutic targets.

AI-based models can analyze high-throughput drug screening data to identify compounds that inhibit viral entry or replication by targeting specific viral or host proteins. By leveraging large-scale experimental datasets, AI facilitates the discovery of novel antiviral candidates that act at early stages of infection to reduce viral load. Such as AI-powered imaging systems have been developed to detect and classify cytopathic effects caused by various viruses, enabling diagnosis without the need for specific staining [

80]. Similar approaches could be adapted to investigate MDV entry and replication mechanisms, supporting the development of targeted antiviral therapies.

Understanding Viral Latency and Reactivation: One of the most critical aspects of MDV pathogenesis is its ability to establish latency within the host, during which the virus remains dormant and evades immune detection. This latent state allows the virus to persist for extended periods and reactivate under certain conditions, such as stress or immune suppression, leading to recurrent infections. AI can be employed to unravel the genetic, epigenetic, and molecular mechanisms underlying viral latency and reactivation. ML algorithms, for example, can analyze transcriptomic and epigenomic datasets to identify key genes and regulatory elements involved in maintaining latency and initiating reactivation [

81]. Additionally, AI-driven models can simulate how environmental or immunological factors influence the likelihood of viral reactivation. Recent studies have underscored the importance of chromatin modifications in the latency of herpesviruses, suggesting that targeting specific histone demethylases may offer therapeutic potential [

82]. By identifying molecular signatures associated with latency, AI can facilitate the development of novel strategies to prevent viral reactivation and reduce the frequency of recurrent outbreaks, providing a promising approach to identify key regulatory elements controlling MDV latency, providing insights for therapeutic interventions.

4.4. AI in Immune Evasion and Viral Persistence

Herpesviruses including MDV have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade host immunity, allowing for lifelong persistence within the host. Understanding these immune evasion strategies is essential for developing more effective vaccines and antiviral treatments.

AI in Immune Evasion Mechanisms: MDV employs multiple immune evasion strategies, including the inhibition of antigen presentation, disruption of cytokine signaling, and modulation of host cell apoptosis pathways [

83]. AI offers a powerful tool for accelerating the identification and characterization of these mechanisms. By analyzing large-scale proteomic, genomic, and immune response datasets, AI models can predict critical interactions between viral and host proteins involved in immune evasion. For example, prior studies on gamma-herpesviruses have outlined various immune evasion strategies, providing a valuable foundation for AI-based modeling of virus–host interactions [

84].

Furthermore, AI can simulate and analyze how MDV proteins interact with host immune cells, enabling the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Such analyses may inform the development of antiviral compounds designed to disrupt these interactions, thereby enhancing the host immune response and improving disease control strategies.

Predicting Viral Persistence and Reactivation Triggers: AI models can also predict what conditions might trigger the reactivation of latent herpesvirus infections. Through the analysis of vast datasets, including infection histories, environmental factors, immune profiles, and genetic predispositions, ML models can identify key patterns that correlate with the risk of reactivation [

81]. This predictive power could be used in clinical settings to anticipate when a chicken is at higher risk of MDV reactivation and to implement preventive measures, such as antiviral treatment or immune system modulation, to reduce the chances of reactivation.

4.5. Enhancing Breeding Programs

Genomic selection for MDV resistance has traditionally relied on quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and pedigree analysis. However, AI has transformed this field by enabling the integration of multi-omic datasets to identify novel resistance-associated biomarkers. AI models can analyze large-scale proteomic and genomic data to predict interactions between viral proteins and host immune components. In one comprehensive study, researchers used deep neural networks to combine transcriptomic and epigenetic data, successfully identifying key gene networks linked to MDV resistance. Their model highlighted candidate genes such as CD8α and TAP1, both of which are critical in antiviral immune responses [

85]. Additionally, the integration of AI-driven genomic evaluations in poultry breeding has been explored as a promising approach to enhance disease resistance traits [

86]. Incorporating these insights into breeding programs through AI-assisted selection has led to the development of genetically resilient chicken lines with improved resistance to both MDV infection and tumor development [

87]. These advancements highlight the potential of AI to drive precision breeding strategies that not only strengthen flock resilience but also maintain productivity and desirable growth characteristics.

5. Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

The integration of AI into MDV research in poultry offers significant promise for improving disease surveillance, diagnosis, and vaccine development. However, several ethical and regulatory issues must be carefully addressed to ensure responsible and sustainable implementation.

From an ethical standpoint, the collection and use of data from poultry farms, such as genomic data, production records, and health monitoring information, raise concerns about data privacy, ownership, and informed consent, especially when commercial interests are involved. Ensuring transparency in how farm-level data is collected, shared, and used in AI model training is essential to build trust among poultry producers and stakeholders [

88,

89,

90].

Algorithmic bias is another important consideration. AI models trained on data from specific breeds, production systems, or geographic regions may not perform accurately across diverse poultry populations. To avoid biased outcomes and ensure generalizability, it is crucial that AI systems are trained on comprehensive and representative datasets that capture the variability in genetic backgrounds, farm practices, and environmental conditions [

91,

92,

93].

On the regulatory side, there is currently a lack of standardized frameworks for the validation and approval of AI-based tools in poultry health. Regulatory authorities and veterinary oversight bodies must develop guidelines to evaluate the accuracy, reliability, and safety of AI applications in MDV diagnosis, outbreak prediction, and vaccine optimization. These frameworks should include requirements for validation in real-world farm settings and continuous post-deployment monitoring to detect unintended consequences [

94,

95].

Overall, the responsible deployment of AI in MDV research will depend on proactive ethical practices, transparent data governance, and robust regulatory oversight to ensure the technology benefits poultry health and supports sustainable farming practices.

6. Challenges and Limitation in Applying AI to MDV Management

Despite the promising potential of AI in managing MDV and other veterinary pathogens, several challenges limit its widespread application. One major hurdle is the availability and quality of data. AI models depend on large,

high-quality datasets for accurate training and validation; however, such datasets are often limited or inconsistent in veterinary medicine. Standardized protocols for data collection and sharing are urgently needed to ensure reproducibility and scalability of AI tools [

96]. Another critical issue is the

interpretability of AI models. Many advanced models, particularly deep learning algorithms, operate as ‘black boxes,’ offering limited insight into how predictions are generated. This lack of transparency can undermine trust among veterinarians, farmers, and other stakeholders, hindering adoption in real-world settings. Implementing explainable AI (XAI) techniques can enhance understanding and trust in AI-driven decisions [

97].

Infrastructure and technical expertise also present significant barriers. The deployment of AI solutions often requires robust digital infrastructure and specialized skills, which may be lacking in certain regions, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. This disparity could widen the digital divide in animal health care [

98]. Furthermore, the use of AI in veterinary contexts raises

ethical and regulatory concerns. Issues related to data privacy, accountability in decision-making, and algorithmic bias must be addressed to ensure responsible and equitable implementation. Establishing clear guidelines and regulatory frameworks is essential for the ethical deployment of AI in veterinary medicine [

99].

7. Strategic Directions for Advancing AI in MDV Research and Control

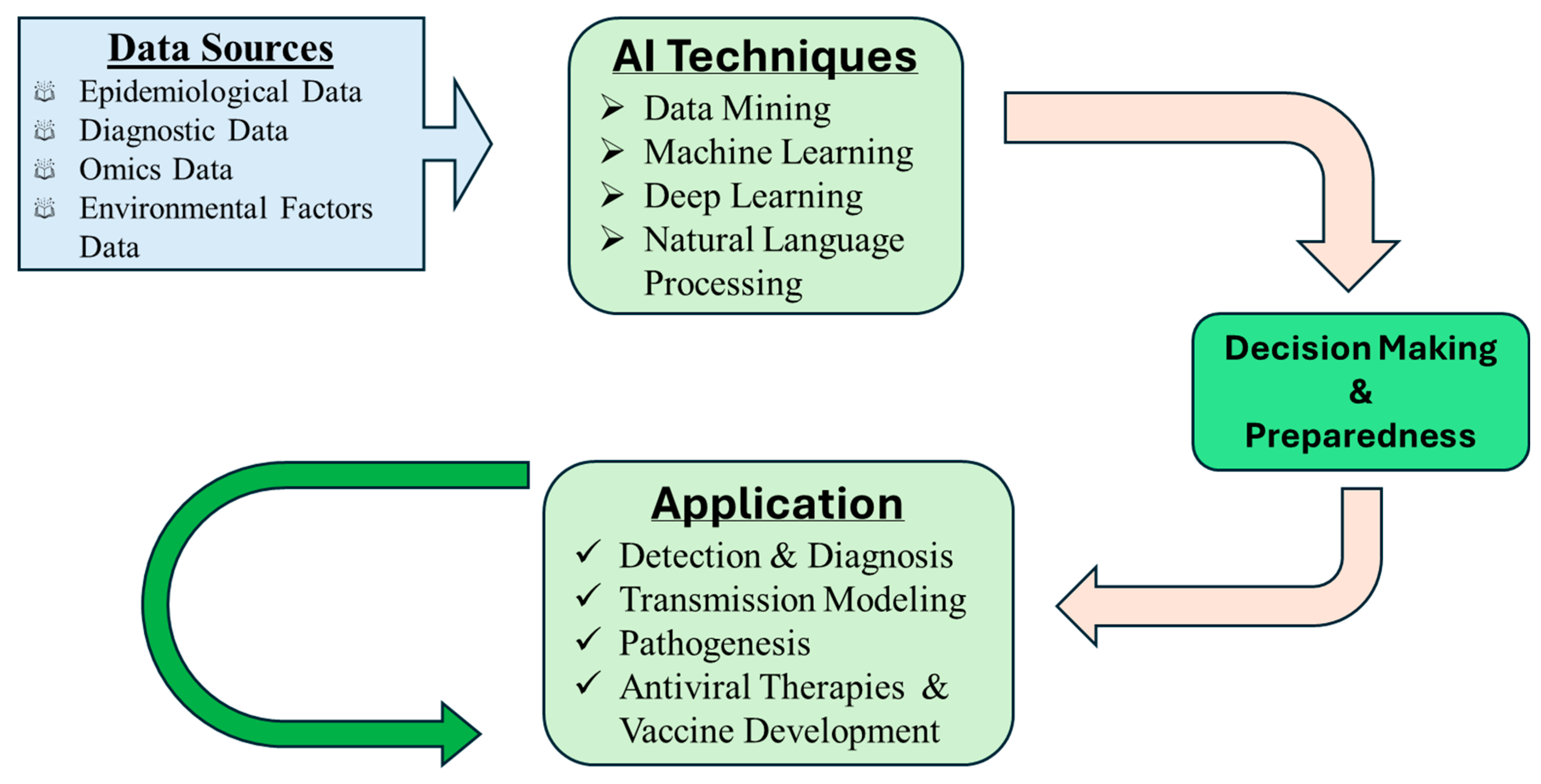

To overcome these challenges and fully harness the potential of AI in MDV research and control, several strategic directions should be pursued. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the integration of AI into herpesvirus and MDV management follows a multi-step process, beginning with data acquisition and culminating in actionable decision-making. The flowchart outlines key stages including data collection, AI model training, applications in prediction and diagnostics, informed decision-making, and model refinement through feedback.

Developing open-source, MDV-specific datasets would be instrumental in facilitating AI research and enhancing model performance. These datasets would also foster collaboration and reproducibility across institutions and disciplines. In veterinary medicine, efforts have demonstrated that standardized and accessible data resources improve the quality of medical records and support integrated research across species and institutions [

100].

Integrating AI with Internet of Things (IoT) technologies could enable real-time disease monitoring and automated responses, improving early detection and outbreak management. For example, combining AI-powered analytics with on-farm sensors may provide continuous surveillance of flock health and environmental conditions [

101]. Advancing AI applications in veterinary medicine will also require close collaboration among veterinarians, data scientists, engineers, and policy-makers. Such multidisciplinary efforts can ensure that AI tools are not only scientifically sound but also practically implementable and ethically grounded. Studies have demonstrated the value of collaborative approaches in enhancing disease identification and preventive care in veterinary contexts [

102].

Additionally, the development of explainable AI (XAI) approaches will be crucial for improving transparency and building user trust. By providing interpretable outputs, XAI can help stakeholders better understand and validate model predictions. In clinical decision support systems, explainability allows professionals to comprehend and verify how machine-based decisions are made, thereby augmenting their decision-making processes [

103,

104]. Finally, continuous updating and validation of AI models using real-world, field-derived data is essential to maintain accuracy and relevance over time. Adaptive models that learn from new data inputs will be better equipped to respond to the evolving nature of MDV and similar pathogens. Retraining AI models with updated data has been shown to enhance their accuracy and effectiveness in dynamic settings [

105].

8. Conclusions

AI holds transformative potential in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of herpesvirus infections, including MDV. It enables improved detection, transmission forecasting, drug discovery, and vaccine development. However, significant challenges remain, including data limitations, model transparency, and the need for real-world validation. Future research should focus on optimizing AI algorithms for veterinary use, enhancing data quality, and expanding datasets to improve model generalizability. AI-powered surveillance and prediction platforms could become vital tools in disease management. Overall, AI offers a promising pathway toward smarter, more resilient approaches to MDV control. With continued innovation, collaboration, and investment, AI can significantly enhance poultry health, productivity, and disease resilience.

References

- Mcelwain TF, Thumbi SM. Animal pathogens and their impact on animal health, the economy, food security, food safety and public health. Rev Sci Tech. 2017, 36, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Šudomová M, Hassan STS. Herpesvirus Diseases in Humans and Animals: Recent Developments, Challenges, and Charting Future Paths. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Branch-Elliman W, Sundermann AJ, Wiens J, Shenoy ES. The future of automated infection detection: Innovation to transform practice (Part III/III). Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2023, 3, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pavlin JA, Mostashari F, Kortepeter MG, Hynes NA, Chotani RA, Mikol YB, Ryan MA, Neville JS, Gantz DT, Writer JV, Florance JE, Culpepper RC, Henretig FM, Kelley PW. Innovative surveillance methods for rapid detection of disease outbreaks and bioterrorism: results of an interagency workshop on health indicator surveillance. Am J Public Health. 2003, 93, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Godfred Yawson Scott, Abdullahi Tunde Aborode, Ridwan Olamilekan Adesola, Emmanuel Ebuka Elebesunu, Joseph Agyapong, Adamu Muhammad Ibrahim, ANGYIBA Serge Andigema, Samuel Kwarteng, Isreal Ayobami Onifade, Adekunle Fatai Adeoye, Babatunde Akinola Aluko, Taiwo Bakare-Abidola, Lateef Olawale Fatai, Osasere Jude-Kelly Osayawe, Modupe Oladayo, Abraham Osinuga, Zainab Olapade, Anthony Ifeanyi Osu, Peter Ofuje Obidi. Transforming early microbial detection: Investigating innovative biosensors for emerging infectious diseases. Advances in Biomarker Sciences and Technology 2024, 6, 59–71. [CrossRef]

- D. Gatherer, D.P. Depledge, C.A. Hartley, M.L. Szpara, P.K. Vaz, M. Benko, C.R. Brandt, N.A. Bryant, A. Dastjerdi, A. Doszpoly, U.A. Gompels, N. Inoue, K.W. Jarosinski, R. Kaul, V. Lacoste, P. Norberg, F.C. Origgi, R.J. Orton, P.E. Pellett, D.S. Schmid, S.J. Spatz, J.P. Stewart, J. Trimpert, T.B. Waltzek, A.J. Davison, ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Herpesviridae. J Gen Virol 2021, 102. [Google Scholar]

- J. Marek, Multiple Nervenentzündung (Polyneuritis) bei Hühnern. Deutsche Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 1907, 15, 417–421.

- N. Osterrieder, J.P. Kamil, D. Schumacher, B.K. Tischer, S. Trapp, Marek’s disease virus: from miasma to model, Nature reviews. Microbiology 2006, 4, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Morrow, F. C. Morrow, F. Fehler, Marek’s disease, in: F. Davison, V. Nair (Eds.), Marek’s Disease, Institute for Animal Health, Compton Laboratory, UK, 2004; pp. 49–61.

- Akbar H, Fasick JJ, Ponnuraj N, Jarosinski KW. Purinergic signaling during Marek’s disease in chickens. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R. L. Witter, The changing landscape of Marek’s disease. Avian Pathology 1998, 27 (Suppl. 1), S46–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. F. Read, S.J. Baigent, C. Powers, L.B. Kgosana, L. Blackwell, L.P. Smith, D.A. Kennedy, S.W. Walkden-Brown, V.K. Nair, Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens. PLoS biology 2015, 13, e1002198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Shao, Ruoyan Zhao, Sha Yuan, Ming Ding, and Yongli Wang. Tracing the evolution of AI in the past decade and forecasting the emerging trends. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, John A. The Evolution of AI: From Foundations to Future Prospects. AI Research Insights 2023.

- Lee, Chen, and Ying Zhang. "AI 2000: A Decade of Artificial Intelligence." TechVision Reports, 2020, WebSci ‘20: Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Web Science: Pages 345 – 354. https://www.techvisionreports.org/ai-2000. [CrossRef]

- Faiyazuddin M, Rahman SJQ, Anand G, Siddiqui RK, Mehta R, Khatib MN, Gaidhane S, Zahiruddin QS, Hussain A, Sah R. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare: A Comprehensive Review of Advancements in Diagnostics, Treatment, and Operational Efficiency. Health Sci Rep. 2025, 8, e70312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mohamed Khalifa, Mona Albadawy. AI in diagnostic imaging: Revolutionising accuracy and efficiency. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update. 2024, 5, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Coelho, L. How Artificial Intelligence Is Shaping Medical Imaging Technology: A Survey of Innovations and Applications. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maniaci A, Lavalle S, Gagliano C, Lentini M, Masiello E, Parisi F, Iannella G, Cilia ND, Salerno V, Cusumano G, La Via L. The Integration of Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence in Modern Medicine. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- kinsulie OC, Idris I, Aliyu VA, Shahzad S, Banwo OG, Ogunleye SC, Olorunshola M, Okedoyin DO, Ugwu C, Oladapo IP, Gbadegoye JO, Akande QA, Babawale P, Rostami S, Soetan KO. The potential application of artificial intelligence in veterinary clinical practice and biomedical research. Front Vet Sci. 2024, 11, 1347550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jarosinski KW, Tischer BK, Trapp S, Osterrieder N. Marek’s disease virus: Lytic replication, oncogenesis and control. Exp. Rev. Vaccin. 2006, 5, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosinski, KW. Interindividual spread of herpesviruses. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2017, 223, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodhoo N, Gurung A, Sharif S, Behboudi S. Marek’s disease in chickens: A review with focus on immunology. Vet. Res. 2016, 47, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schat, K.A. , & Skinner, M.A. (2014). Avian immunosuppressive diseases and immunoevasion. In K. A. Schat, B. Kaspers, & P. Kaiser (Eds.), Avian immunology (2nd ed., pp. 275–297). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Nair, V. Evolution of Marek’s disease – a paradigm for incessant race between the pathogen and the host. Veterinary Journal 2005, 170, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schat, K. A. , & Nair, V. (2013). Marek’s disease. In D. E. Swayne (Ed.), Diseases of Poultry (13th ed., pp. 515–552). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Read AF, Baigent SJ, Powers C, Kgosana LB, Blackwell L, Smith LP, Kennedy DA, Walkden-Brown SW, Nair VK. Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Hulten MCW, Cruz-Coy J, Gergen L, Pouwels H, Ten Dam GB, Verstegen I, de Groof A, Morsey M, Tarpey I. Efficacy of a turkey herpesvirus double construct vaccine (HVT-ND-IBD) against challenge with different strains of Newcastle disease, infectious bursal disease and Marek’s disease viruses. Avian Pathol. 2021, 50, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D. A. , Dunn, P. A., & Read, A.F. Industry-Wide Surveillance of Marek’s Disease Virus on Commercial Poultry Farms. Avian Diseases 2017, 61, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufer, B. B. , & Osterrieder, N. Latest Insights into Marek’s Disease Virus Pathogenesis and Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2017, 12, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, S. J. , Katz, M. E., Renz, K. G., & Walkden-Brown, S. W. Prevalence of Marek’s Disease Virus in Different Chicken Populations in Iraq and Indicative Virulence Based on Sequence Variation in the EcoRI-Q (meq) Gene. Avian Diseases 2013, 57, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). "Marek’s Disease." Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, 2023, Chapter 3.3.13. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahm/3.03.13_MAREK_DIS.pdf.

- Schat, Karel A., and Michael A. Skinner. 2014. "Avian Immunosuppressive Diseases and Immunoevasion." In Avian Immunology, 2nd ed., edited by Karel A. Schat, Bernd Kaspers, and Pete Kaiser, 275–297. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- The Poultry Site. (n.d.). Marek’s disease control in broiler breeds. Retrieved , from https://www.thepoultrysite. 11 May.

- Real-time PCR for the Detection of Marek’s Disease Virus." Iowa State University Digital Repository, Iowa State University. https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/9f5fb6ec-afa4-432d-88e1-d7a02eac7d29/content.

- Kalita, A. J. , Subba, M., Adil, S., Wani, M. A., Beigh, Y. A., & Shafi, M. Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in poultry disease detection and diagnosis: A review: AI and Machine learning in poultry disease diagnosis. Letters In Animal Biology 2025, 5, 01–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, Rasheed O. , Anuoluwapo O. Ajayi, Hakeem A. Owolabi, Lukumon O. Oyedele, and Lukman A. Akanbi. Internet of Things and Machine Learning Techniques in Poultry Health and Welfare Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 200, 107266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhankani V, Kutz JN, Schiffer JT. Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Genital Tract Shedding Is Not Predictable over Months or Years in Infected Persons. PLoS Comput Biol 2014, 10, e1003922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. , Pandey, A., Bawden, C. et al. Integrating artificial intelligence with mechanistic epidemiological modeling: a scoping review of opportunities and challenges. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.U.G. , Tsui, J.LH., Chang, S.Y. et al. Artificial intelligence for modelling infectious disease epidemics. Nature 2025, 638, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicknall, I. H. , Looker, K. J., Gottlieb, S. L., Chesson, H. W., Schiffer, J. T., Elmes, J., & Boily, M.-C. Review of mathematical models of HSV-2 vaccination: Implications for vaccine development. Vaccine 2019, 37, 7007–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Santiago M, León-Velasco DA, Maldonado-Sifuentes CE, Chanona-Hernandez L. A State-of-the-Art Review of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applications in Healthcare: Advances in Diabetes, Cancer, Epidemiology, and Mortality Prediction. Computers. 2025, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh DP, Ma TF, Ip HS, Zhu J. Artificial intelligence and avian influenza: Using machine learning to enhance active surveillance for avian influenza viruses. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019, 66, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Morr C, Ozdemir D, Asdaah Y, Saab A, El-Lahib Y, Sokhn ES. AI-based epidemic and pandemic early warning systems: A systematic scoping review. Health Informatics Journal 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Herrick KA, Huettmann F, Lindgren MA. A global model of avian influenza prediction in wild birds: the importance of northern regions. Vet Res. 2013, 44, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Musa E, Nia ZM, Bragazzi NL, Leung D, Lee N, Kong JD. Avian Influenza: Lessons from Past Outbreaks and an Inventory of Data Sources, Mathematical and AI Models, and Early Warning Systems for Forecasting and Hotspot Detection to Tackle Ongoing Outbreaks. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Yajie, Md Gapar Md Johar, and Asif Iqbal Hajamydeen. "Poultry Disease Early Detection Methods Using Deep Learning Technology." Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2023, 32, 1712–1723. [CrossRef]

- Taleb, Hassan M., Khalid Mahrose, Amal A. Abdel-Halim, Hebatallah Kasem, Gomaa S. Ramadan, Ahmed M. Fouad, Asmaa F. Khafaga, Norhan E. Khalifa, Mahmoud Kamal, Heba M. Salem, Abdulmohsen H. Alqhtani, Ayman A. Swelum, Anna Arczewska-Włosek, Sylwester Świątkiewicz, and Mohamed E. Abd El-Hack. "Using Artificial Intelligence to Improve Poultry Productivity – A Review." . Annals of Animal Science 2024, 25, 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Cuan, K. , Zhang, T., Li, Z., Huang, J., Ding, Y., & Fang, C. Automatic Newcastle disease detection using sound technology and deep learning method. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 194, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, Aristeidis, Christos Karras, Spyros Sioutas, Christos Makris, George Katselis, Ioannis Hatzilygeroudis, John A. Theodorou, and Dimitrios Tsolis. An Integrated GIS-Based Reinforcement Learning Approach for Efficient Prediction of Disease Transmission in Aquaculture. Information 2023, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardui, S. , Ameur, A., Vermeesch, J. R., & Hestand, M.S. Single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing comes of age: Applications and utilities for medical diagnostics. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A. I. , da Silva, A. C., & Ramos, R.T.J. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in viral genomics and precision medicine. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A. , Robicquet, A., Ramsundar, B., Kuleshov, V., DePristo, M., Chou, K.,... & Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R. J. , & Roizman, B. (2001). Herpes simplex viruses. In D. M. Knipe & P. M. Howley (Eds.), Fields Virology (4th ed., pp. 2461–2509). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Liu, Y. , Chen, P. H. C., Krause, J., & Peng, L. How to read articles that use machine learning: Users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA 2020, 322, 1806–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G. , Kooi, T., Bejnordi, B. E., Setio, A. A. A., Ciompi, F., Ghafoorian, M.,... & Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. , Phung, D., Tran, T., Gupta, S., Rana, S., Karmakar, C.,... & Venkatesh, S. Guidelines for developing and reporting machine learning predictive models in biomedical research: A multidisciplinary view. npj Digital Medicine 2022, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, A. , Arnaout, R., Mofrad, M., & Arnaout, R. Fast and accurate view classification of echocardiograms using deep learning. NPJ Digital Medicine 2018, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Wang W, Chen B. Leukocyte recognition with convolutional neural network. Journal of Algorithms & Computational Technology 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrat Ehsan, & Mohtavipour, S. Broiler-Net: A Deep Convolutional Framework for Broiler Behavior Recognition in Cage-Free Poultry Houses. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12176.

- Min, S. , Lee, B., & Yoon, S. Deep learning in bioinformatics. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, H. , Alkan, C., & Bilgen, T. Unsupervised deep learning approaches for clustering and visualizing single-cell transcriptomic data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22, bbaa318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamaneh, D. , Boyle, B., & Belzile, F. Efficient genome-wide genotyping strategies and data integration pipelines for crop research. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22, bbab060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R. , Chang, P. C., Alexander, D., Schwartz, S., Colthurst, T., Ku, A.,... & DePristo, M.A. A universal SNP and small-indel variant caller using deep neural networks. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J. , Jung, H., & Kim, Y. Artificial intelligence in genome interpretation: A brief overview. Genomics & Informatics 2021, 19, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, D. , Tischer, B. K., Fuchs, W., Osterrieder, N., & Rautenschlein, S. New insights into the pathogenesis and control of Marek’s disease virus. Veterinary Microbiology 2021, 255, 108975. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , Yoon, W., Kim, S., Kim, D., Kim, S., So, C. H., & Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M. , King, D., Beltagy, I., & Ammar, W.. ScispaCy: Fast and robust models for biomedical natural language processing. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I. , Lo, K., & Cohan, A. SciSpacy: Fast and robust models for biomedical natural language processing. Proceedings of the 18th BioNLP Workshop and Shared Task 2019, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkden-Brown, S. W. , Islam, A. F. M. F., Reddy, S. M., & Renz, K.G. Marek’s disease: Still a significant threat to the poultry industry. Poultry Science 2019, 98, 5286–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y. , Kim, T. J., & Reddy, S.M. Machine learning-based prediction of Marek’s Disease Virus virulence using genomic data. Avian Pathology 2020, 49, 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. , & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2013, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G. , Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W.,... & Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Rout, M. , Borchardt, G. J., & Reddy, S.M. Machine learning in poultry disease forecasting: Integration of omics and epidemiological data. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022, 9, 853478. [Google Scholar]

- Nasirahmadi, A. , Gonzalez, J., Sturm, B., & Hensel, O. AI applications for behavior-based monitoring in animal production systems: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 196, 106889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. , Kim, M. J., Choi, H., & Cho, K.H. Early detection of Marek’s Disease in poultry using deep learning-based gait analysis. Poultry Science 2022, 101, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, R. , Zulkifli, I., & Alimon, A.R. Welfare assessment in poultry through automated behavior monitoring: Recent advances and future perspectives. Animals 2023, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer KM, Manton JD, Soh TK, Mascheroni L, Connor V, Crump CM, Kaminski CF. A fluorescent reporter system enables spatiotemporal analysis of host cell modification during herpes simplex virus-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 2021, 296, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akkutay-Yoldar, Z. , Yoldar, M.T., Akkaş, Y.B. et al. A web-based artificial intelligence system for label-free virus classification and detection of cytopathic effects. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves IJ, Jackson SE, Poole EL, Nachshon A, Rozman B, Schwartz M, Prinjha RK, Tough DF, Sinclair JH, Wills MR. Bromodomain proteins regulate human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation allowing epigenetic therapeutic intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118, e2023025118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schang LM, Hu M, Cortes EF, Sun K. Chromatin-mediated epigenetic regulation of HSV-1 transcription as a potential target in antiviral therapy. Antiviral Res. 2021, 192, 105103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vider-Shalit T, Fishbain V, Raffaeli S, Louzoun Y. Phase-dependent immune evasion of herpesviruses. J Virol. 2007, 81, 9536–9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sorel O, Dewals BG. The Critical Role of Genome Maintenance Proteins in Immune Evasion During Gammaherpesvirus Latency. Front Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lipkin E, Smith J, Soller M, Burt DW, Fulton JE. Mapping quantitative trait loci regions associated with Marek’s disease on chicken autosomes by means of selective DNA pooling. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 31896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caldas-Cueva JP, Mauromoustakos A, Sun X, Owens CM. Use of image analysis to identify woody breast characteristics in 8-week-old broiler carcasses. Poult Sci. 2021, 100, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gul H, Habib G, Khan IM, Rahman SU, Khan NM, Wang H, Khan NU, Liu Y. Genetic resilience in chickens against bacterial, viral and protozoal pathogens. Front Vet Sci. 2022, 9, 1032983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Floridi, L. , Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chiarello, F., Chatila, R., Dignum, V.,... & Vayena, E. AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines 2018, 28, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B. D. , Allo, P., Taddeo, M., Wachter, S., & Floridi, L. The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society 2016, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambon-Thomsen, A. , Rial-Sebbag, E., & Knoppers, B. M. Trends in ethical and legal frameworks for the use of human biobanks. European Respiratory Journal 2007, 30, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N. , Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., & Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z. , Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, N. M. , & King, J.H. Big data ethics. Wake Forest Law Review 2014, 49, 393–432. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200.

- Vokinger, K. N. , Feuerriegel, S., & Kesselheim, A.S. Mitigating bias in machine learning for medicine. Communications Medicine 2021, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsulie OC, Idris I, Aliyu VA, Shahzad S, Banwo OG, Ogunleye SC, Olorunshola M, Okedoyin DO, Ugwu C, Oladapo IP, Gbadegoye JO, Akande QA, Babawale P, Rostami S, Soetan KO. The potential application of artificial intelligence in veterinary clinical practice and biomedical research. Front Vet Sci. 2024, 11, 1347550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiao S, Dhand NK, Wang Z, Hu K, Thomson PC, House JK, Khatkar MS. Review of applications of deep learning in veterinary diagnostics and animal health. Front Vet Sci. 2025, 12, 1511522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oduoye MO, Fatima E, Muzammil MA, Dave T, Irfan H, Fariha FNU, Marbell A, Ubechu SC, Scott GY, Elebesunu EE. Impacts of the advancement in artificial intelligence on laboratory medicine in low- and middle-income countries: Challenges and recommendations-A literature review. Health Sci Rep. 2024, 7, e1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coghlan, S. , Quinn, T. Ethics of using artificial intelligence (AI) in veterinary medicine. AI & Soc 2024, 39, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguslav, M. R. , Kiehl, A., Kott, D., Strecker, G. J., Webb, T., Saklou, N., Ward, T., & Kirby, M. Fine-tuning foundational models to code diagnoses from veterinary health records. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.15186. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410, 15186. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Q. , Wang, J., Yang, W., Wu, S., Zhang, W., Sun, C., & Xu, K. Edge AI-enabled chicken health detection based on enhanced FCOS-Lite and knowledge distillation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.09562. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407, 09562. [Google Scholar]

- Szlosek, D. , Coyne, M., Riggot, J., Knight, K., McCrann, D. J., & Kincaid, D. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm for clinical wellness visit classification in cats and dogs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10314. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406, 10314. [Google Scholar]

- Luca Longo, Mario Brcic, Federico Cabitza, Jaesik Choi, Roberto Confalonieri, Javier Del Ser, Riccardo Guidotti, Yoichi Hayashi, Francisco Herrera, Andreas Holzinger, Richard Jiang, Hassan Khosravi, Freddy Lecue, Gianclaudio Malgieri, Andrés Páez, Wojciech Samek, Johannes Schneider, Timo Speith, Simone Stumpf. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) 2.0: A manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Information Fusion. 2024, 106, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadi, A. M. , Du, Y., Guendouz, Y., Wei, L., Mazo, C., Becker, B. A., & Mooney, C. Current Challenges and Future Opportunities for XAI in Machine Learning-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.C. (2021, August 16). This AI helps detect wildlife health issues in real time. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/this-ai-helps-detect-wildlife-health-issues-in-real-time/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).