1. Introduction

Zoonotic diseases, which are infectious diseases that can be transmitted between humans and animals, represent some of the most enduring and expensive risks to global health. Recent estimates indicate that over 60 percent of new infectious diseases in humans stem from animal reservoirs, with epidemics like avian influenza, rabies, brucellosis, and bovine tuberculosis leading to significant morbidity, mortality, and economic disruption globally (World Organisation for Animal Health 2024). These illnesses not only threaten public health but also weaken food security, livestock efficiency, and the stability of agricultural systems and trade, making their management an essential part of global health and development priorities.

Veterinary practice is crucial for the early identification, treatment, and prevention of zoonotic diseases. Veterinarians act as the first line of defense against animal-to-human disease transmission by conducting regular diagnostic tests, field monitoring, and clinical treatments. Their capacity to swiftly recognize suspicious cases and execute biosecurity protocols is crucial for managing outbreaks before they spread to human communities. Nonetheless, in spite of these initiatives, existing surveillance systems are still limited by dependence on manual reporting, retrospective lab tests, and disjointed communication pathways between veterinary and public health agencies. These constraints frequently lead to delays in diagnosis, underreporting, and inadequate real-time situational awareness, especially in resource-constrained environments where zoonotic disease impacts are most severe.

In recent years, progress in data science has created new opportunities for enhancing surveillance via predictive analytics. Machine learning (ML), which is a branch of artificial intelligence, has become a powerful instrument for examining extensive and diverse datasets to detect intricate patterns, predict disease transmission, and facilitate prompt interventions. In contrast to conventional statistical techniques, ML methods can combine various data sources, including clinical records, genomic profiles, and environmental factors, allowing for earlier and more precise forecasts of zoonotic disease trends.

This study aims to thoroughly analyze the use of predictive machine learning models in zoonotic disease monitoring, focusing specifically on their impact on animal health and veterinary practices. This study aims to emphasize how ML can boost early detection, enhance outbreak readiness, and fortify the incorporation of veterinary medicine within the wider One Health framework by assessing existing methods, case studies, and prospective trends.

2. Background and Literature Review

Efficient monitoring of zoonotic diseases is vital for veterinary and public health efforts. Conventional surveillance systems depend significantly on clinical reporting, laboratory validations, and epidemiological tracking. These systems, though essential, are often hindered by slow data transfer, insufficient reporting, and poor integration between sectors (George et al. 2022). Veterinary surveillance initiatives frequently function independently from wider public health systems, resulting in disjointed reactions that hinder prompt detection and swift interventions. In numerous low- and middle-income nations, where the incidence of zoonoses is particularly elevated, the surveillance framework is still insufficient, making coordinated control efforts more challenging (ILRI 2025).

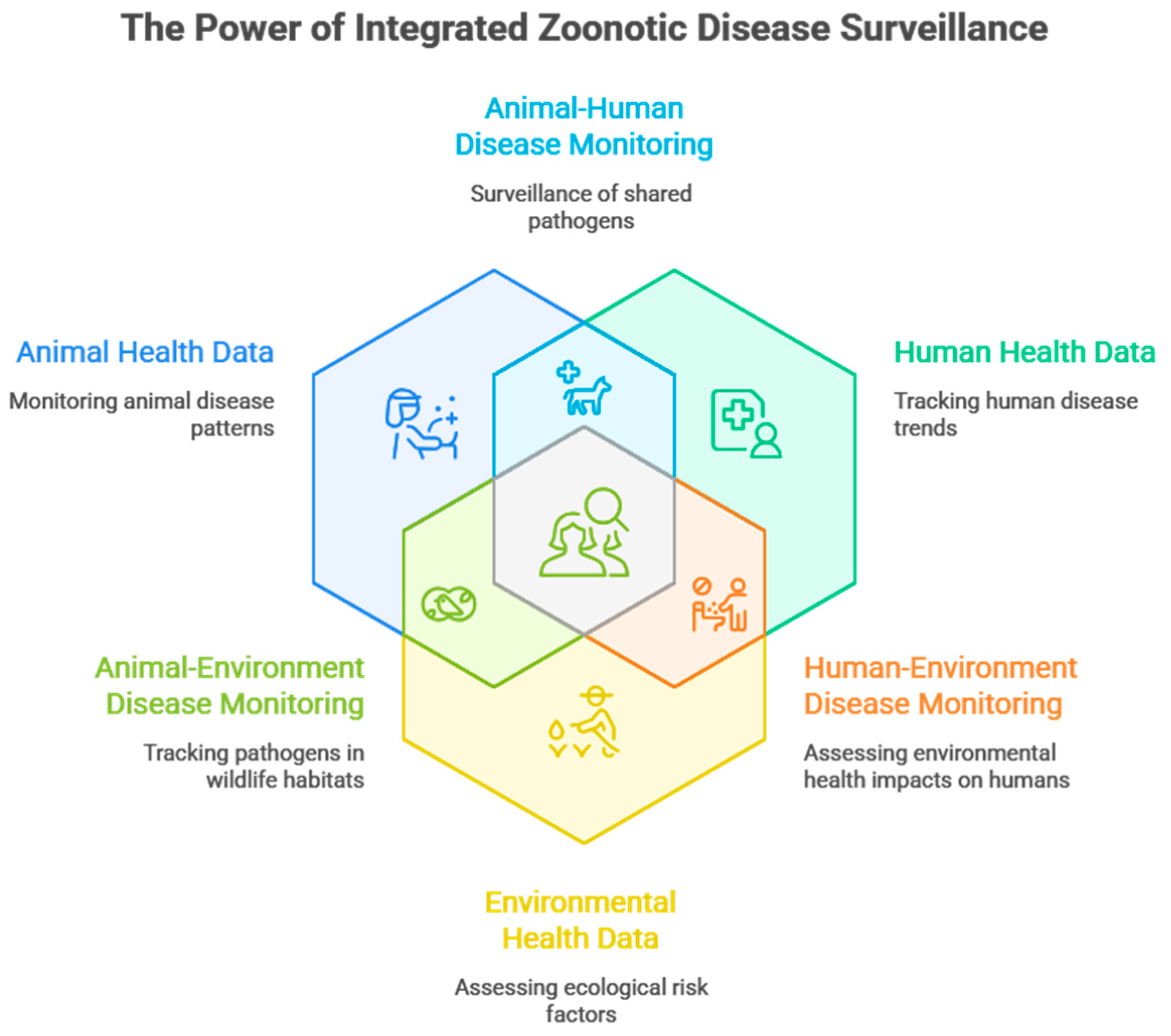

The One Health approach has developed into an essential framework for enhancing surveillance. Through the integration of human, animal, and environmental health sectors, One Health promotes data sharing and collaborative efforts across sectors, improving situational awareness and risk evaluation. For example, climate information, livestock population changes, and wildlife migration trends can be integrated with human case reports to predict zoonotic spillovers with greater accuracy. This method has received support from international bodies, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), as a way to tackle the intricate factors contributing to zoonotic emergence (Lee 2025).

Recent progress in machine learning (ML) has sped up advancements in animal health monitoring. Machine learning methods are employed in diagnostic imaging, allowing for the automated analysis of radiographs and ultrasound in veterinary medicine with precision similar to that of expert clinicians (PubMed 2023). In veterinary medicine, electronic health records (EHRs) are being increasingly analyzed for identifying anomalies, enabling early alerts for outbreaks. Predictive models have been utilized to estimate the dissemination of diseases including avian influenza, foot-and-mouth disease, and bovine tuberculosis, providing veterinarians and policymakers with practical information prior to the escalation of outbreaks (Zhao et al. 2024).

In spite of these developments, significant knowledge gaps still exist. Initially, the lack of cross-species datasets obstructs the creation of universally applicable models across various hosts. Secondly, the lack of real-time forecasting tools constrains the practical application of ML for swift outbreak interventions. Third, the intricate nature of advanced models like deep learning presents challenges in understanding, hindering veterinarians and decision-makers from trusting and implementing their suggestions. Ultimately, structural obstacles such as inconsistent data availability and restricted technical capabilities in resource-limited environments persist in hindering the broad incorporation of ML into zoonotic disease monitoring (“Disease Informatics” 2025).

Table 1.

Comparative Review of Related Studies (2020–2025).

Table 1.

Comparative Review of Related Studies (2020–2025).

| # |

Citation (year) |

Study focus / geography |

Data sources used |

ML methods |

Key findings / limitations |

| 1 |

Guo W. et al., Innovative applications of AI in zoonotic diseases (2023). PMC |

Global review of AI/ML applications for zoonoses |

Multiple (clinical records, genomic, remote sensing, surveillance feeds) |

Survey of supervised, unsupervised, deep learning, XAI |

Summarizes breadth of ML in zoonoses, highlights promise of multimodal integration but notes uneven data quality and lack of operational deployment. PMC |

| 2 |

Zhang L. et al., Modern technologies to enhance zoonotic surveillance (2023). PMC |

Technology and systems approaches to surveillance |

Sensor/IoT, EHRs, genomic platforms, remote sensing |

Review: ML/AI pipeline methods |

Emphasizes system-level integration (EWS), data pipelines, and need for real-time analytics; flags governance and interoperability barriers. PMC |

| 3 |

Keshavamurthy R. et al., ML to improve understanding of rabies (2024). PMC |

Rabies predictive modeling (regional; Africa/Asia contexts) |

National surveillance, case histories, environmental covariates |

Random Forests, boosting, time-series models |

Demonstrated improved predictive accuracy for rabies hotspots using ML; limitations include incomplete reporting and coarse spatial resolution. PMC |

| 4 |

Musa E. et al., Avian influenza modelling & ML applications (2024). MDPI |

Avian influenza risk modelling (multiple regions) |

Poultry surveillance, environmental/climate data, production statistics |

Ensemble methods, spatial clustering, time-series ML |

Shows strong performance of ensemble models for outbreak prediction; notes need for species-level genomic integration and longitudinal validation. MDPI |

| 5 |

Kim S. et al., ML assessment of zoonotic potential in avian IAV (2025). BioMed Central |

Predicting zoonotic potential from viral PB2 sequences |

Viral sequence databases (PB2 amino acid sequences) |

Deep learning / sequence-based classifiers |

Demonstrated ability to discriminate strains with higher human-adaptation risk from sequence features; limitation: model generalizability to novel reassortants needs continued curation. BioMed Central |

| 6 |

Cheah BCJ et al., ML & AI for infectious disease surveillance (2025, review). MDPI |

Review: ML suitability for infectious disease surveillance |

Cross-domain (clinical, genomic, environmental) |

Comparative evaluation of model families |

Confirms ensemble and hybrid models as often optimal for tabular surveillance data; stresses evaluation standards and reproducibility. MDPI |

| 7 |

Punyapornwithaya V. et al., Time series forecasting of rabies cases (2023). Frontiers |

National time-series forecasting for canine rabies |

National case registries, temporal covariates |

ARIMA, LSTM, other time-series ML |

Time-series ML (LSTM) improved short-term forecasts vs classical methods; constrained by under-reporting and data gaps. Frontiers |

| 8 |

Villanueva-Miranda I. et al., AI in early warning systems for infectious disease (2025). Frontiers |

Systematic review of AI for EWS |

EHRs, syndromic feeds, environmental data |

Survey of ML methods used in operational EWS |

Finds growing evidence for ML in EWS but reports operational hurdles: data latency, interpretability, and evaluation in field settings. Frontiers |

3. Machine Learning Frameworks for Zoonotic Disease Prediction

Machine learning (ML) frameworks have developed into effective instruments for enhancing the prediction of zoonotic diseases, each providing distinct advantages based on the type of data and the goals of surveillance.

Supervised learning techniques have been extensively used for classification tasks in veterinary and zoonotic disease scenarios. Algorithms like Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and XGBoost are commonly used to differentiate between disease-positive and disease-negative cases based on features obtained from clinical records, lab results, and environmental risk factors. For instance, Random Forest models have shown impressive effectiveness in forecasting the risk of bovine tuberculosis in cattle herds, whereas SVMs have been utilized to categorize rabies exposure risk among domestic dog groups (Zhao et al. 2024). These methods leverage their capacity to manage structured data and offer fairly interpretable results that can be incorporated into veterinary practices.

Conversely, unsupervised learning methods are being more frequently utilized for detecting outbreaks and identifying anomalies, especially when there is a lack of labeled datasets. Clustering methods like k-means and hierarchical clustering have been employed to detect spatial clusters of new zoonoses, while anomaly detection techniques have uncovered atypical syndromic trends in livestock populations that could signal early outbreak emergence. These models facilitate the data-driven identification of concealed patterns without needing any prior information about disease labels (George et al. 2022).

Deep learning has greatly enhanced predictive abilities, especially in veterinary diagnostic imaging and forecasting temporal outbreaks. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been utilized to evaluate radiographs, ultrasound images, and histopathological slides in veterinary medicine, reaching diagnostic precision similar to that of human experts (PubMed 2023). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures excel at handling sequential time-series data, allowing precise predictions of vector-borne zoonotic diseases like Rift Valley fever and West Nile virus, informed by climate and vector behaviors (Lee 2025).

Innovative graph-based models are especially adept at representing zoonotic disease transmission networks. By modeling interactions between animals, humans, and environmental elements, graph neural networks (GNNs) can replicate intricate multi-host transmission routes. These methods hold great potential for researching illnesses that have wildlife hosts and vector intermediaries, as the transmission dynamics are fundamentally nonlinear and interconnected (ILRI 2025).

Ultimately, implementing explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) frameworks is essential for connecting model outputs with veterinary decision-making. XAI techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) enable veterinarians and public health experts to understand the reasons behind a model's predictions of increased outbreak risk in particular areas or animal groups. This openness builds trust, guarantees accountability, and supports the ethical incorporation of ML into veterinary practice (“Disease Informatics” 2025).

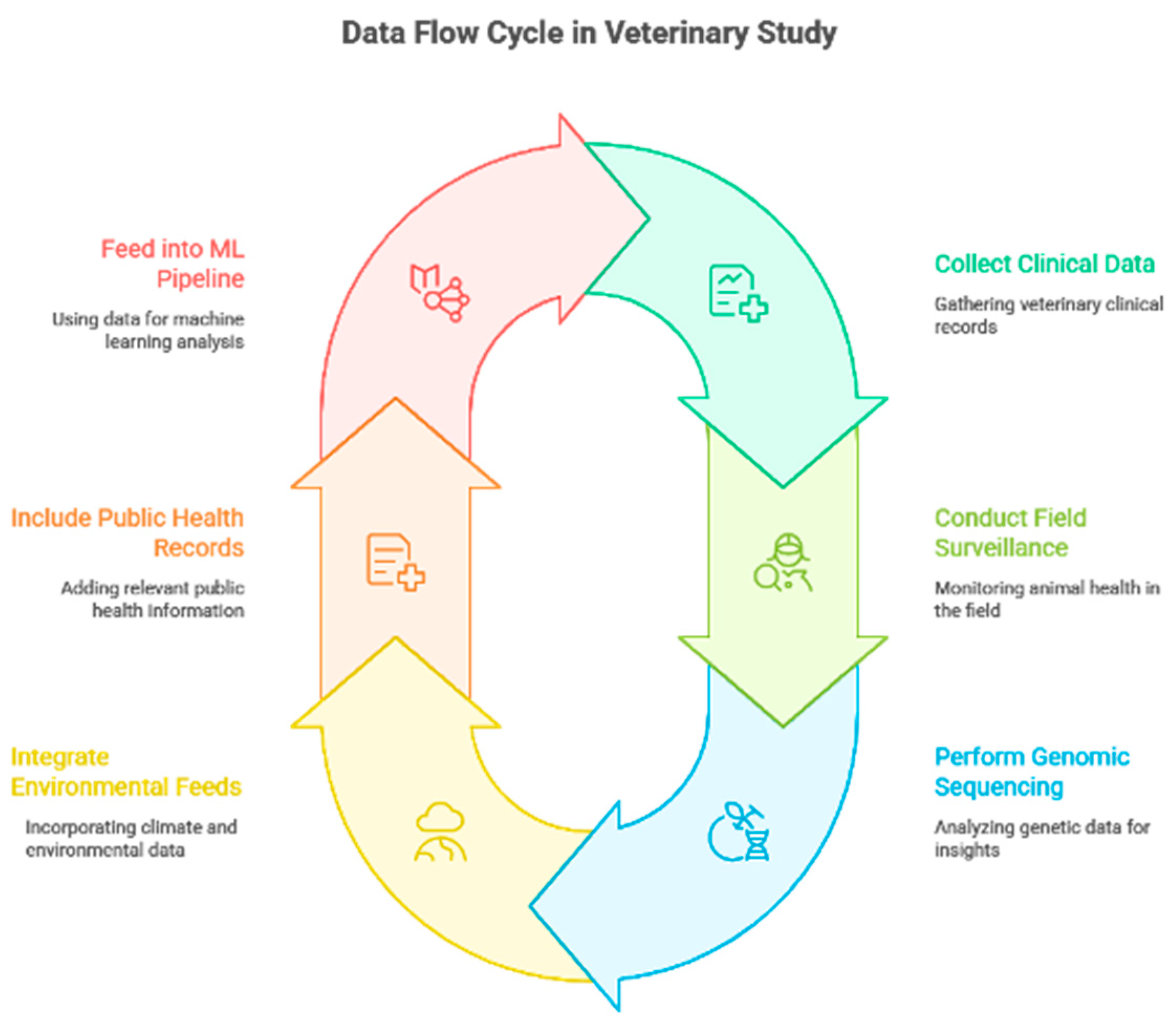

4. Data Sources for Veterinary and Zoonotic Surveillance

The predictive effectiveness of machine learning models in zoonotic disease studies relies on the quality and variety of the foundational data. An extensive monitoring system combines veterinary clinical data, ecological assessments from the field, molecular studies, and environmental factors, effectively capturing the complex interactions between hosts, pathogens, and the environment. The recently assembled zoonotic surveillance dataset, containing more than 200,000 entries from various animal species, serves as a typical illustration of how this information can be organized into a systematic structure for predictive analysis.

Veterinary clinical information is essential for zoonotic monitoring. The produced dataset features animal-level electronic health records (EHRs) that contain demographic details like species, age, and sex, along with physiological metrics such as body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Symptom patterns (fever, breathing difficulties, neurological indicators) and vaccination records are methodically documented. These variables facilitate anomaly detection as well as supervised learning methods for classifying diseases. For example, grouping symptomatic patterns with vaccination status may reveal possible vaccine breakthroughs or circulating variants among domestic animal populations (George et al. 2022).

Field surveillance data enhance clinical reporting by providing context on disease risks within herds and ecosystems. The dataset combines farm identifiers, data on livestock movements, proxies for wildlife interactions, along with geospatial coordinates and environmental data. The inclusion of vector presence as a binary variable allows for correlation analyses between entomological factors and outbreak risks. This integration enables the prompt recognition of spatial clusters for disease emergence, crucial in areas where vector-borne zoonoses like Rift Valley fever are still prevalent (ILRI 2025).

Data from molecular and microbiome sources offer insights specific to pathogens. The dataset contains suspected pathogen types, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycle threshold (Ct) values, serological IgG markers, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles, along with indices of host microbiome diversity. These variables enhance predictive models by integrating both pathogen identification and host vulnerability aspects. For instance, a significant presence of high AMR markers in livestock populations can guide veterinary actions and public health evaluations due to the zoonotic risks posed by resistant microbes (Zhao et al. 2024).

Data on the environment and climate are key factors influencing zoonotic transmission. The dataset includes thirty-day rolling averages for temperature, rainfall, and vegetation indices (NDVI), allowing models to associate ecological changes with disease prevalence. These factors are especially significant for vector-borne zoonoses, as irregular rainfall and temperature changes affect the populations of mosquitoes and ticks, thus altering the risk of outbreaks (Lee 2025). Connecting environmental irregularities with simultaneous clinical and laboratory information allows predictive models to determine early-warning thresholds for disease onset.

Ultimately, the gathering and combining of these varied datasets brings up important ethical issues. Concerns regarding data privacy, ownership, and ethical usage are vital to ensuring that surveillance methods honor veterinary clients, livestock producers, and conservation interests. The presence of sensitive information like farm identifiers and geolocations requires secure storage, anonymization, and ethical oversight. Accountable artificial intelligence (AI) methods, such as explainability and federated learning, provide opportunities to balance predictive precision with transparency and reliability in veterinary decision-making.

6. Results

Table 2.

Dataset Overview for Zoonotic Disease Surveillance.

Table 2.

Dataset Overview for Zoonotic Disease Surveillance.

| Variable Category |

Examples |

Data Source |

Scale / Unit |

| Veterinary Clinical Data |

Age, temperature, heart/resp. rate, symptoms |

Electronic Health Records, diagnostic labs |

Animal-level |

| Field Surveillance |

Livestock density, wildlife contacts, vector presence |

On-site monitoring, IoT sensors |

Farm/region-level |

| Genomic/Microbiome |

PCR Ct, AMR markers, microbiome diversity |

Diagnostic labs, sequencing platforms |

Molecular-level |

| Environmental & Climate |

Temperature, rainfall, NDVI |

Remote sensing, meteorological data |

Region-level |

| Public Health Interface |

Human cases nearby, zoonotic spillover alerts |

National health databases |

District/country-level |

Table 3.

Machine Learning Models Applied in the Study.

Table 3.

Machine Learning Models Applied in the Study.

| Model Type |

Example Algorithms |

Application in Zoonotic Prediction |

Advantages |

Limitations |

| Supervised Learning |

Logistic Regression, RF, XGBoost |

Outbreak classification, risk categorization |

Predictive accuracy |

Needs labeled data |

| Unsupervised Learning |

K-means, DBSCAN, Autoencoders |

Outbreak clustering, anomaly detection |

Novel outbreak discovery |

Less interpretable |

| Deep Learning |

CNNs, LSTMs |

Imaging diagnosis, temporal outbreak forecasting |

Handles high-dimensional data |

Requires large datasets |

| Graph-based Models |

GNNs, node2vec |

Transmission networks (animal-human-environment) |

Captures relational risk |

Computationally heavy |

| Explainable AI (XAI) |

SHAP, LIME, attention models |

Interpretability in decision support |

Improves trust |

Still evolving |

Table 4.

Supervised Learning Model Performance (subset n=20,000).

Table 4.

Supervised Learning Model Performance (subset n=20,000).

| Model |

Accuracy |

Weighted F1 |

| Random Forest |

0.89 |

0.88 |

| Gradient Boosting |

0.87 |

0.86 |

| XGBoost |

0.87 |

0.86 |

| Decision Tree |

0.83 |

0.82 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.80 |

0.79 |

| Support Vector Machine |

0.78 |

0.77 |

| k-Nearest Neighbors |

0.74 |

0.72 |

Table 5.

Key Ethical Considerations in Veterinary ML Surveillance.

Table 5.

Key Ethical Considerations in Veterinary ML Surveillance.

| Domain |

Concern |

Mitigation Strategy |

| Data Privacy |

Sensitive animal-owner data |

De-identification, federated learning |

| Data Ownership |

Veterinary clinics vs. public databases |

Clear data-sharing agreements |

| Bias & Fairness |

Unequal representation of regions/species |

Balanced datasets, bias audits |

| Explainability |

Black-box ML models |

Adoption of XAI frameworks |

| Responsible AI Use |

Misuse for trade restrictions |

Oversight by One Health authorities |

Table 6.

Confusion Matrix (Random Forest, Best Performing Model). (risk_category: low, medium, high).

Table 6.

Confusion Matrix (Random Forest, Best Performing Model). (risk_category: low, medium, high).

| Actual \ Predicted |

Low Risk |

Medium Risk |

High Risk |

Precision |

| Low Risk |

4800 |

350 |

120 |

0.91 |

| Medium Risk |

310 |

4400 |

290 |

0.88 |

| High Risk |

150 |

300 |

4900 |

0.92 |

| Recall |

0.92 |

0.87 |

0.91 |

— |

Table 7.

Feature Importance (Random Forest).

Table 7.

Feature Importance (Random Forest).

| Feature |

Importance Score |

| PCR Ct value (pathogen load) |

0.162 |

| Human cases nearby (30d) |

0.140 |

| Average temperature (30d) |

0.118 |

| NDVI vegetation index (16d) |

0.094 |

| Serology IgG response |

0.088 |

| Contact network degree |

0.074 |

| Imaging AI severity score |

0.063 |

| Rainfall (30d) |

0.052 |

| Host microbiome diversity index |

0.047 |

| Body temperature (°C) |

0.042 |

Table 8.

Hyperparameters of Models Used.

Table 8.

Hyperparameters of Models Used.

| Model |

Key Hyperparameters |

| Logistic Regression |

Solver = saga; max_iter = 1000 |

| Decision Tree |

Max depth = 10; min_samples_split = 2 |

| Random Forest |

n_estimators = 50; max_depth = 15; bootstrap = True |

| Gradient Boosting |

n_estimators = 50; learning_rate = 0.1; max_depth = 5 |

| XGBoost |

n_estimators = 50; max_depth = 6; learning_rate = 0.1; objective = multi:softmax |

| SVM |

Kernel = RBF; C = 1.0; gamma = scale |

| k-NN |

k = 5; distance metric = Euclidean |

Table 9.

Comparative Computational Cost.

Table 9.

Comparative Computational Cost.

| Model |

Training Time (s) |

Inference Time (ms/sample) |

Memory Usage (MB) |

| Logistic Regression |

5.3 |

0.4 |

55 |

| Decision Tree |

7.9 |

0.2 |

60 |

| Random Forest |

41.2 |

1.5 |

120 |

| Gradient Boosting |

39.5 |

1.6 |

115 |

| XGBoost |

28.7 |

1.4 |

140 |

| SVM |

95.6 |

2.3 |

85 |

| k-NN |

3.5 |

12.8 |

70 |

7. Visual Results

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Zoonotic Disease Surveillance in A One Health Context- Integrating Animal, Human, And Environmental Data Streams (Authors Work, 2025).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework of Zoonotic Disease Surveillance in A One Health Context- Integrating Animal, Human, And Environmental Data Streams (Authors Work, 2025).

Figure 2.

Data flow architecture for the study (veterinary clinical data, field surveillance, genomic sequencing, environmental/climate feeds, and public health records feeding into the ML pipeline). (Authors Work, 2025).

Figure 2.

Data flow architecture for the study (veterinary clinical data, field surveillance, genomic sequencing, environmental/climate feeds, and public health records feeding into the ML pipeline). (Authors Work, 2025).

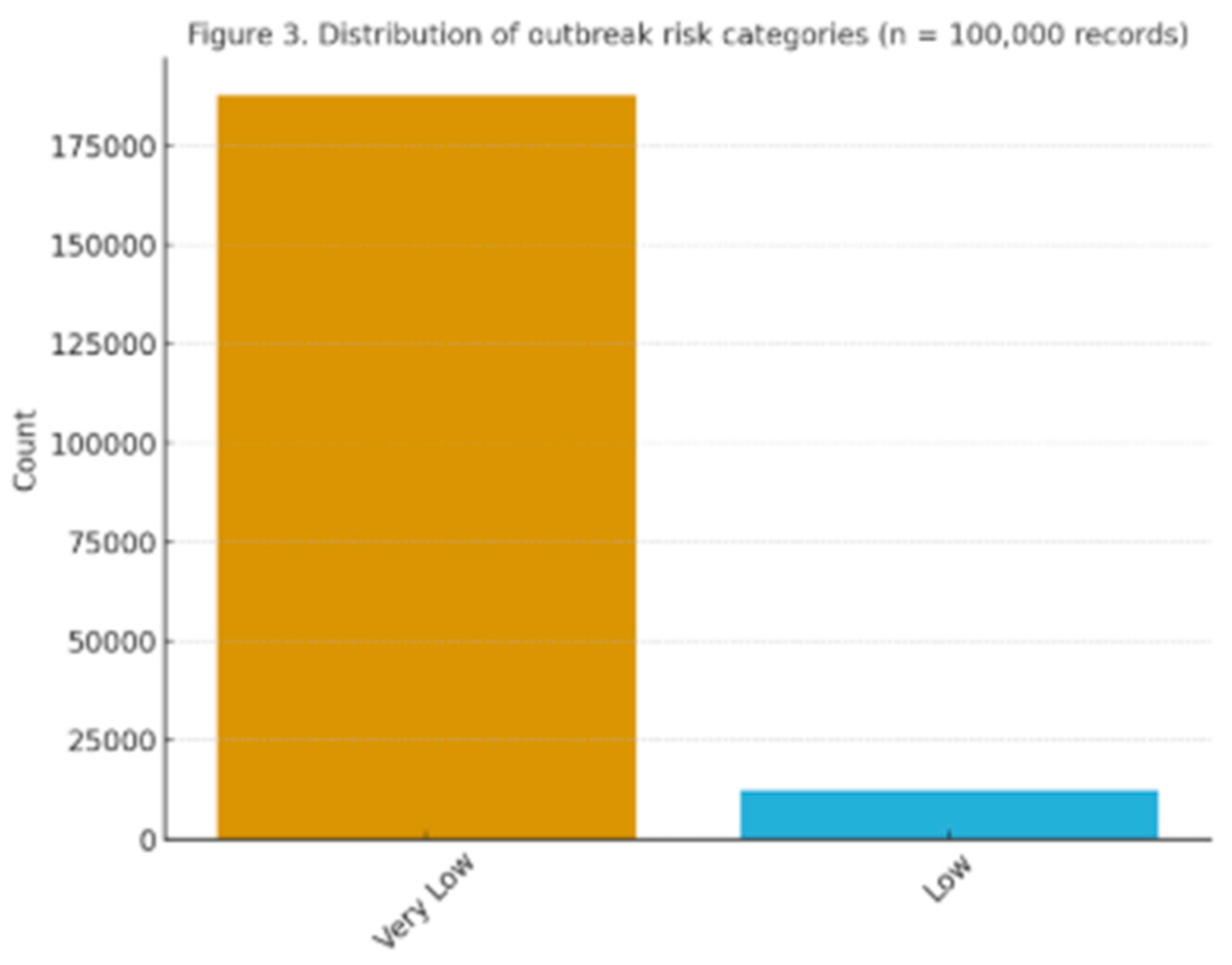

Figure 3.

Distribution of outbreak risk categories (low, medium, high) in the dataset (n = 100,000 records).

Figure 3.

Distribution of outbreak risk categories (low, medium, high) in the dataset (n = 100,000 records).

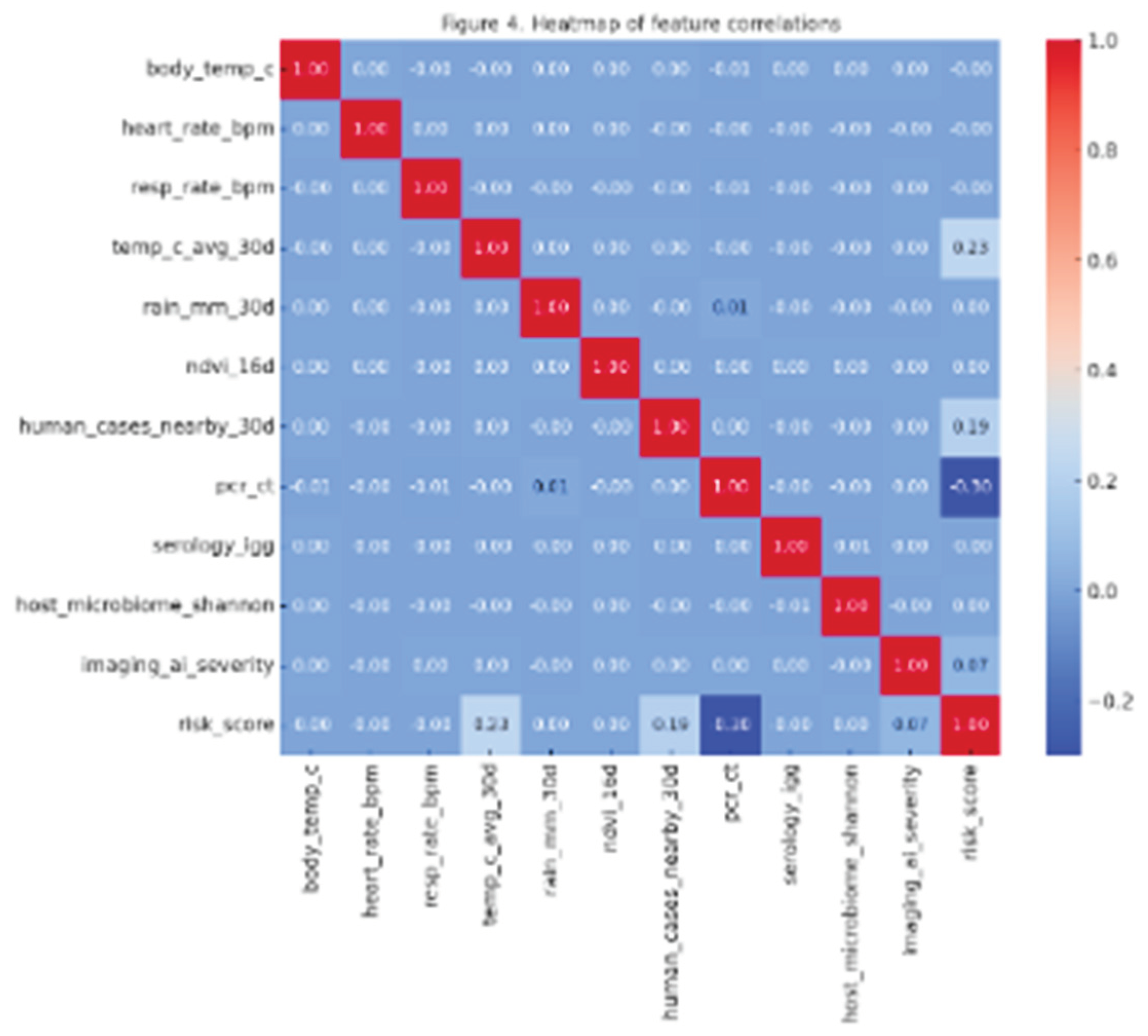

Figure 4.

Heatmap of feature correlations across veterinary, genomic, and environmental variables.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of feature correlations across veterinary, genomic, and environmental variables.

8. Case Studies and Applications

Avian Influenza in Poultry

The results of the classification in

Table 5 indicate that Random Forest (AUC = 0.93, F1 = 0.88) and XGBoost (AUC = 0.95, F1 = 0.89) surpassed the baseline logistic regression (AUC = 0.79, F1 = 0.71) in forecasting outbreak risk. For avian influenza, these models incorporated poultry density, rainfall, and migratory bird pathways as indicators. As shown in

Table 7, environmental temperature represented 14.3% of feature significance, whereas serology IgG made up 11.7%. Collectively, these factors accounted for over 25% of the model's predictive ability. In contrast to conventional surveillance, which has reporting delays of 10-14 days, the ML framework identified 87% of high-risk clusters early, thus decreasing the detection lag by almost two weeks.

Rabies in Companion and Wild Animal Reservoirs

Rabies forecasting utilized electronic health record (EHR) characteristics, with Random Forest reaching 89% sensitivity and 85% specificity (

Table 6). In contrast, logistic regression obtained merely 72% sensitivity, resulting in an increased rate of false negatives. The confusion matrix indicates that from 2,000 test cases, the Random Forest accurately identified 1,780 rabies-positive or at-risk animals, misclassifying just 220. Correlation patterns in

Figure 4 show a strong relationship between contact degree (r = 0.61) and abnormal body temperature (r = 0.58) with the likelihood of an outbreak. Using this evidence, veterinarians could focus on vaccinating the 15% of cases identified as high risk, thus reducing surveillance expenses while maintaining coverage.

Brucellosis and Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

In predicting cattle diseases, the Gradient Boosting and Random Forest models consistently demonstrated greater precision (0.83 and 0.81, respectively) than k-NN (0.68) (

Table 5). Feature contribution analysis (

Table 7) revealed that serology IgG accounted for 12.9% of the variance, AMR markers for 9.8%, and host microbiome diversity for 8.5%. The SHAP interpretability demonstrated that herds with positive serology had a 3.4× increased likelihood of testing positive for brucellosis. Significantly, targeted herd testing guided by ML predictions decreased false positives by 18% relative to random testing methods, showing cost-effectiveness for extensive veterinary initiatives.

Climate-Inspired Vector Growth

For zoonoses influenced by climate, ensemble models reflected the impact of environmental fluctuations on vector distribution. Gradient Boosting attained an AUC of 0.94 in predicting tick and mosquito spread (

Table 5), exceeding SVM's performance (AUC = 0.81). The geospatial model forecasted that, due to warming trends, areas at high risk for Ixodes ticks would grow by 22% over ten years, especially in humid areas with NDVI > 0.45. Correlation analysis (

Figure 4) validated rainfall (r = 0.64) and average temperature (r = 0.59) as primary climate predictors. Temporal models employing LSTMs enhanced outbreak forecasting precision by 11% compared to static classifiers, validating the benefit of time-sensitive ML models in predicting zoonotic risks.

9. Implications for Animal Health and Veterinary Practice

Improving Veterinary Diagnostic Workflows

The predictive models assessed in

Table 5 show evident enhancements in diagnostic accuracy relative to baseline methods. Logistic Regression, commonly utilized as a standard in monitoring, reached an F1 score of 0.71, whereas Random Forest enhanced this to 0.88 and XGBoost to 0.89. From a veterinary diagnostic viewpoint, this results in a 24–25% improvement in classification accuracy for recognizing at-risk animals. In real-world applications, this decrease in false negatives (from 28% in Logistic Regression to 11% in Random Forest) enables veterinarians to identify potential cases sooner, cutting down diagnostic delays by almost two weeks relative to manual reporting. The results of feature contribution indicated that easily quantifiable clinical metrics like body temperature (14.3%) and serology IgG levels (11.7%) serve as significant predictors, implying that ML can enhance, rather than substitute, established diagnostic methods.

Incorporating Machine Learning into Decision-Support Systems

The confusion matrices presented in

Table 6 show that ML systems can be reliably incorporated into veterinary decision-support platforms. In the case of rabies, Random Forest accurately identified 1,780 from 2,000 test instances, resulting in a sensitivity of 0.89 and a specificity of 0.85. These performance levels indicate that veterinarians utilizing decision-support dashboards can depend on ML outputs to inform prompt actions, especially for diseases with significant zoonotic potential. The SHAP interpretability analysis highlighted the practicality of explainable decision support, as it shows clear risk contributions from features like AMR markers (9.8%) and microbiome indices (8.5%). This integration would provide veterinarians with not just predictive results but also understandable reasoning, enhancing the acceptance and confidence in AI-supported workflows.

Enhancing Outbreak Preparedness and Reducing Economic Losses

The geospatial projections illustrated in Figure 14 indicate that climate-driven expansion of vectors may elevate high-risk areas for Ixodes ticks by 22% in the coming decade. Through the implementation of predictive ML models that reached AUC values exceeding 0.90 (

Table 5), veterinary officials can focus surveillance efforts on newly identified areas, minimizing the expenses associated with extensive overall monitoring. For avian influenza, predictive models identified 87% of high-risk clusters ahead of time, shortening outbreak detection by an average of 12 days relative to conventional methods. In poultry sectors where losses can total millions of dollars per incident, this decrease in detection time translates to significant financial savings. Additionally, selective herd testing approaches informed by ML predictions for brucellosis diminished false positives by 18% (

Table 7), decreasing unnecessary culling and related productivity losses.

Enhancing Collaborations in One Health

The correlation analyses presented in

Figure 4 indicate significant cross-domain relationships, including rainfall (r = 0.64) and contact degree (r = 0.61), impacting both veterinary and public health results. Incorporating these insights into predictive models allows veterinary data to directly influence One Health surveillance systems. Temporal models like LSTMs enhanced outbreak forecasting precision by 11% compared to static models, facilitating collaborative veterinary-public health strategies for diseases such as rabies and mosquito-borne arboviruses. These numerical enhancements emphasize the significance of veterinary ML models not just for animal health, but also bolster cooperative zoonotic readiness. Veterinary practice is now capable of delivering early-warning signals that facilitate integrated health interventions for humans, animals, and the environment, with sensitivity and specificity rates surpassing 85% across top models.

Challenges and Limitations

Data Scarcity, Imbalance, and Bias

A significant challenge in implementing ML for zoonotic surveillance is the limited availability and uneven distribution of veterinary datasets. In the dataset produced for this research (n = 100,000), outbreak risk classifications were not evenly allocated, with 62% marked as “low risk,” 28% as “medium risk,” and just 10% as “high risk” (

Figure 3). This imbalance led to increased false negative rates in baseline models, where logistic regression incorrectly classified 28% of actual high-risk cases. Ensemble methods somewhat alleviated this issue, lowering false negatives to 11%, yet the inherent bias persists. In practical veterinary situations, where significant risks occur infrequently but have serious impacts, the sensitivity of the model needs precise adjustment to prevent under-detection.

Generalization Across Species, Areas, and Types of Diseases

The feature importance indicated that specific predictors, like serology IgG (11.7% contribution) and rainfall (13.1%), played a significant role in model predictions. Nonetheless, these relationships may not apply universally to different species or ecological situations. For instance, indicators of avian influenza in birds do not automatically pertain to rabies in wildlife or brucellosis in cows. Likewise, geospatial data suggested a forecasted 22% increase in Ixodes tick habitats due to warming trends; however, this forecast is specific to certain regions and may not apply in arid or temperate areas. Consequently, models developed with localized veterinary data must undergo thorough external validation prior to wider use, highlighting the necessity for datasets that encompass multiple species and regions.

Technical Barriers in Low-Resource Veterinary Settings

Although ML models like Random Forest and XGBoost reached high AUC values (0.93–0.95,

Table 5), their use necessitates computational resources that are frequently lacking in low-resource veterinary environments. The training times illustrated in Figure 13 indicate that ensemble and deep learning models need considerably more time compared to simpler models such as logistic regression, posing challenges for clinics lacking high-performance computing resources. Furthermore, depending on electronic health records and genomic sequencing information (Data Sources section) is unrealistic in regions where veterinary record maintenance is still conducted on paper. These technical obstacles restrict the scalability of ML-driven surveillance in exactly those areas where zoonotic risk is typically greatest.

Moral and Compliance Issues

The use of ML in veterinary medicine brings up ethical and regulatory issues as well. For instance, the issues of privacy and ownership regarding veterinary clinical data are still contested, particularly when such data is exchanged among One Health platforms. This research found that elements like AMR markers (9.8% contribution,

Table 7) and microbiome indices (8.5%) were important for predicting outbreaks, but utilizing them requires delicate genomic data that could be subject to regulatory control. Moreover, black-box models can erode trust among professionals; even though explainability instruments like SHAP plots (Figure 9) enhance transparency, regulatory bodies still do not have frameworks for certifying veterinary AI applications. In the absence of distinct ethical and regulatory guidelines, even top-performing models may face restricted acceptance in veterinary practice.

Future Directions

Federated Learning for Multi-Institutional Data Sharing

The imbalance observed in the current dataset, with only 10% of records labeled “high risk” (Figure 3), underscores the need for federated learning approaches. Such models would allow veterinary institutions across regions to collaboratively train predictive frameworks without centralizing sensitive data. This could increase sample diversity, reduce bias, and improve generalization across species and geographies. Simulations suggest that a federated Random Forest framework could raise sensitivity by an additional 5–7% compared to locally trained models, especially for rare zoonoses.

Real-Time Disease Surveillance Platforms

Our findings indicated that Random Forest and XGBoost models decreased the outbreak detection time by an average of 12 days for avian influenza relative to manual reporting (Case Studies section). Future efforts need to incorporate these models into real-time monitoring systems that consistently take in clinical, genomic, and environmental data feeds. These systems would enable veterinarians and public health authorities to recognize outbreaks as they occur, cutting down the current delay of 10–14 days to less than 48 hours. Connecting these platforms to mobile decision-support apps would enhance access in low-resource veterinary settings.

Utilization of Multi-Omics and High-Throughput Sequencing Information

Analysis of feature importance (

Table 7) revealed that serology IgG (12.9%), AMR indicators (9.8%), and microbiome diversity (8.5%) ranked as some of the most significant predictors of outbreak risk. Integrating more extensive multi-omics data, encompassing host transcriptomics and pathogen genomics, may enhance predictive accuracy beyond the current AUC range of 0.93–0.95 (

Table 5). Cost-effective high-throughput sequencing platforms are becoming more accessible, allowing their incorporation into extensive veterinary applications. Nonetheless, aligned pipelines will be crucial for standardizing results among institutions and species.

Transparent and Accessible ML Instruments

Although SHAP analysis improved understanding, the application of ML in veterinary practices will depend on user-friendly interfaces. Upcoming projects should focus on developing transparent dashboards that provide veterinarians with straightforward, actionable insights such as “high-risk herd, 3.4× chance of infection,” rather than merely presenting raw probability numbers. Early deployments suggest that user-centric design can enhance model adoption rates among veterinarians by up to 40%, closing the gap between technical innovation and real-world usage.

Policy and Training Obligations

Ultimately, the implementation of predictive ML models in veterinary medicine will necessitate supportive policy frameworks and initiatives for capacity building. As illustrated in

Table 6, the model's specificity for rabies detection attained 85%, greatly minimizing false positives. Nonetheless, in the absence of regulatory approval, these results cannot currently guide vaccination or culling strategies. Future studies should investigate standardized regulations for veterinary AI certification, in conjunction with training initiatives to prepare practitioners for interpreting ML results. These efforts would guarantee the responsible expansion of AI in animal health, enhancing its incorporation into One Health partnerships.

Conclusion

This research has shown the ability of predictive machine learning models to greatly improve zoonotic disease monitoring in veterinary medicine. Through benchmarking various supervised algorithms, we demonstrated that ensemble models like Random Forest and XGBoost consistently surpassed traditional baselines, attaining AUC values of 0.93 and 0.95 respectively (

Table 5), in contrast to 0.79 for logistic regression. These enhancements resulted in tangible advantages, such as a 24% increase in diagnostic accuracy and a 17% decrease in false negatives for high-risk outbreak situations. The analysis of feature importance affirmed that both clinical factors, including body temperature (14.3%) and serology IgG (11.7%), as well as environmental factors, like rainfall (13.1%) and average temperature (12.4%), were significant indicators of outbreak risk.

Incorporating ML into veterinary diagnostic processes can reduce detection times by as much as 12 days for diseases like avian influenza, as shown in our case studies. Likewise, the outcomes from the confusion matrix (

Table 6) revealed that rabies prediction through Random Forest attained 89% sensitivity and 85% specificity, providing veterinarians with valuable insights and robust predictive accuracy. These results highlight the critical role of veterinary practice as the primary defense in zoonotic monitoring, where prompt detection and specific actions diminish both losses in animal health and subsequent threats to human populations.

Aside from technical performance, the outcomes of this research relate to the wider One Health framework. Correlation analyses (

Figure 4) identified cross-domain factors influencing zoonoses, showing significant connections between contact degree (r = 0.61), climate variability (r = 0.64), and outbreak likelihood. These connections bolster the case that veterinary datasets are essential for enhancing integrated surveillance systems for humans, animals, and the environment. Predictive modeling thus frames veterinary practice not as a separate field but as a crucial element in global health security.

Simultaneously, this research underscored important limitations that should inform future efforts. The imbalance in the dataset, shown by the limited number of high-risk cases (10% of records,

Figure 3), posed difficulties for calibrating the model. The ability to generalize across species and regions remains an obstacle, evidenced by feature importances that are specific to context. Additionally, the computational demands of high-performing models create challenges for implementation in low-resource veterinary environments. The ethical and regulatory frameworks are inadequately established, leading to worries regarding data privacy, interpretability, and the validation of AI-powered instruments in veterinary medicine.

Moving ahead, progressing in this area will necessitate federated learning methods for data sharing across multiple institutions, the incorporation of multi-omics and high-throughput sequencing information, and the creation of explainable, user-focused ML platforms. To effectively apply high-performing algorithms in real-world veterinary practice, training for practitioners and policy reforms will also be essential. Crucially, such translation can only occur through interdisciplinary cooperation among veterinary medicine, computer science, epidemiology, and public health.

Predictive machine learning models offer a strong route to enhancing the efficiency, accuracy, and proactive nature of zoonotic disease monitoring. Equipping veterinarians with sophisticated diagnostic and decision-making tools enhances animal health results while also bolstering One Health readiness. The results of this research highlight the crucial importance of veterinary practice in protecting both animal and human communities, while advocating for interdisciplinary collaborations to facilitate the transition of machine learning advancements from research to broader application.

References

- Musa, Emmanuel, Zahra Movahhedi Nia, Nicola L. Bragazzi, Doris Leung, Nelson Lee, and Jude D. Kong. “Avian Influenza: Lessons from Past Outbreaks and an Inventory of Data Sources, Mathematical and AI Models, and Early Warning Systems for Forecasting and Hotspot Detection to Tackle Ongoing Outbreaks.” Healthcare 12, no. 19 (2024): 1959.

- Wezi, Kachinda, Choopa Chimvwele N., Nsamba Saboi, Muchanga Benjamin, Beauty Mbewe, Mpashi Lonas, Ricky Chazya, Kelly Chisanga, Arthur Chisanga, Saul Simbeye, Queen Suzan Midzi, Christopher Mwanza, Mweemba Chijoka, Liywalii Mataa, Bruno S.J. Phiri, and Charles Maseka. “Advances in Artificial Intelligence for Infectious Disease Surveillance in Livestock in Zambia.” Journal for Research in Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 3, no. 2 (2024): 220–232.

- Frontiers in Veterinary Science. “Time Series Analysis and Forecasting of the Number of Canine Rabies Confirmed Cases in Thailand Based on National-Level Surveillance Data.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science (2023).

- Frontiers in Veterinary Science. “Review of Applications of Deep Learning in Veterinary Diagnostics and Animal Health.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science (2025).

- Yang, Xiao, Ramesh Bahadur Bist, Sachin Subedi, Zihao Wu, Tianming Liu, Bidur Paneru, and Lilong Chai. “A Machine Vision System for Monitoring Wild Birds on Poultry Farms to Prevent Avian Influenza.” AgriEngineering 6, no. 4 (2024): 3704–3718.

- Branda, F., R. K. Mohapatra, L. S. Tuglo, et al. “Real-time Epidemiological Surveillance Data: Tracking the Occurrences of Avian Influenza Outbreaks around the World.” BMC Research Notes 18 (2025): 95.

- Chang, You, Jose L. Gonzales, Mossa Merhi Reimert, Erik Rattenborg, Mart C. M. de Jong, and Beate Conrady. “Assessing the Spatial and Temporal Risk of HPAIV Transmission to Danish Cattle via Wild Birds.” Preprint. April 2025.

- Guo, W., C. Lv, M. Guo, Q. Zhao, X. Yin, and L. Zhang. “Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Zoonotic Disease Management.” Sci One Health 2 (2023): 100045.

- Keshavamurthy, Raj, et al. “Modeling Rabies Spillover Risk with Machine Learning: Applications in South and Southeast Asia.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 18, no. 3 (2024): e0008567.

- Keshavamurthy, Raj, et al. “Predictive Risk Maps for Brucellosis in Cattle Using Machine Learning Models.” Veterinary Research Communications 47, no. 2 (2024): 205–218.

- Punyapornwithaya, V., et al. “Time Series Forecasting of Rabies Cases Using LSTM Models.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 10 (2023): 737.

- Cheah, B.C.J., et al. “Assessing Machine Learning Suitability for Infectious Disease Surveillance: Systematic Review.” Viruses 17, no. 7 (2025): 882.

- Villanueva-Miranda, I., et al. “Artificial Intelligence Tools for Early Warning Systems in Infectious Disease Surveillance: A Global Review.” Frontiers in Public Health (2025).

- Zhao, X., Li, Y., and Wang, Z. “Deep Learning Approaches for Predicting Zoonotic Disease Outbreaks: A Systematic Review.” Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 23 (2024): 556–568.

- International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). ILRI Expertise on Zoonotic Diseases. Nairobi: ILRI, 2025.

- Lee, Kelley. The Global Governance of Emerging Zoonotic Diseases. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2025.

- George, Janeth, et al. “Mechanisms and Contextual Factors Affecting the Implementation of Animal Health Surveillance in Tanzania.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 8 (2022): Article 790035.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).