Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: The rapid onset of COVID-19 placed immense strain on many already overstretched healthcare systems. The unique physiological changes of pregnancy, amplified by the complex effects of COVID-19 in pregnant women, rendered prioritization of infected expectant mothers more challenging. This work aims to use state-of-the-art machine learning techniques to predict whether a COVID-19-infected pregnant woman will be admitted to ICU (Intensive Care Unit). Methods: A retrospective study using data from COVID-19 infected women admitted to 2 hospital 1 in Astana and 1 in Shymkent, Kazakhstan, from May to July 2021. The developed machine learning platform implements and compares the performance of eight binary classifiers including Gaussian naïve Bayes, K-nearest neighbors, logistic regression with L2 regularization, random forest, AdaBoost, gradient boosting, eXtreme gradient boosting, and linear discriminant analysis. Results: Data from 1168 pregnant women with COVID-19 was analyzed. From them, 9.4% were admitted to ICU. Logistic regression with L2 regularization achieved the highest F1-score during the model selection phase while achieving an AUC of 0.84 on the test set during the evaluation stage. Furthermore, the feature importance analysis conducted by calculating Shapley Additive Explanation values points to leucocyte counts, C-reactive protein, pregnancy week, and eGFR and hemoglobin as the most important features for predicting ICU admission. Conclusion: The predictive model here obtained may be an efficient support tool for prioritizing care of COVID-19 infected pregnant women in clinical practice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Pre-processing

2.3. Model selection

2.4. Model evaluation

2.5. SHAP analysis

2.8. Software and Packages

3. Results

3.1. Data Description

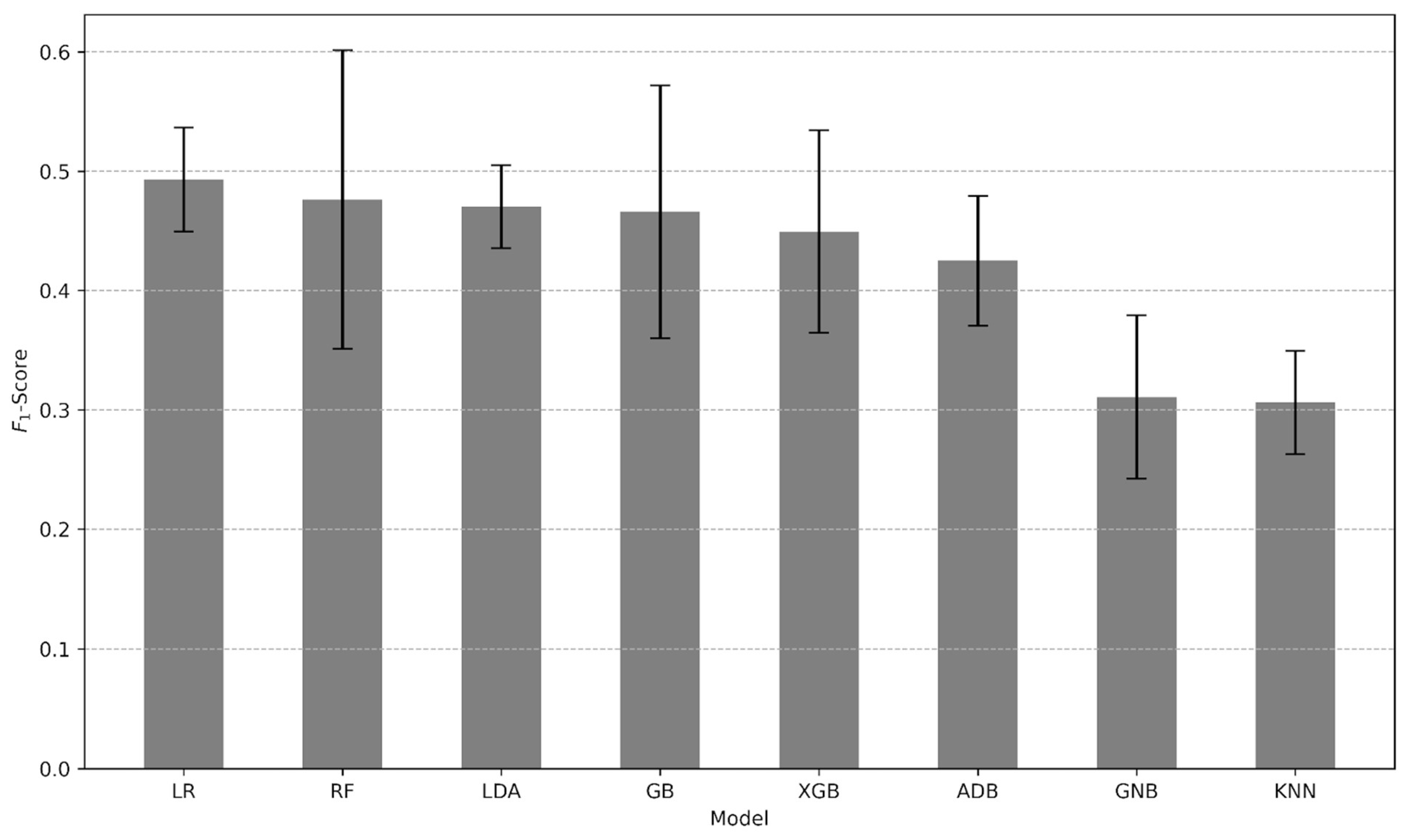

3.2. Predictive Performance

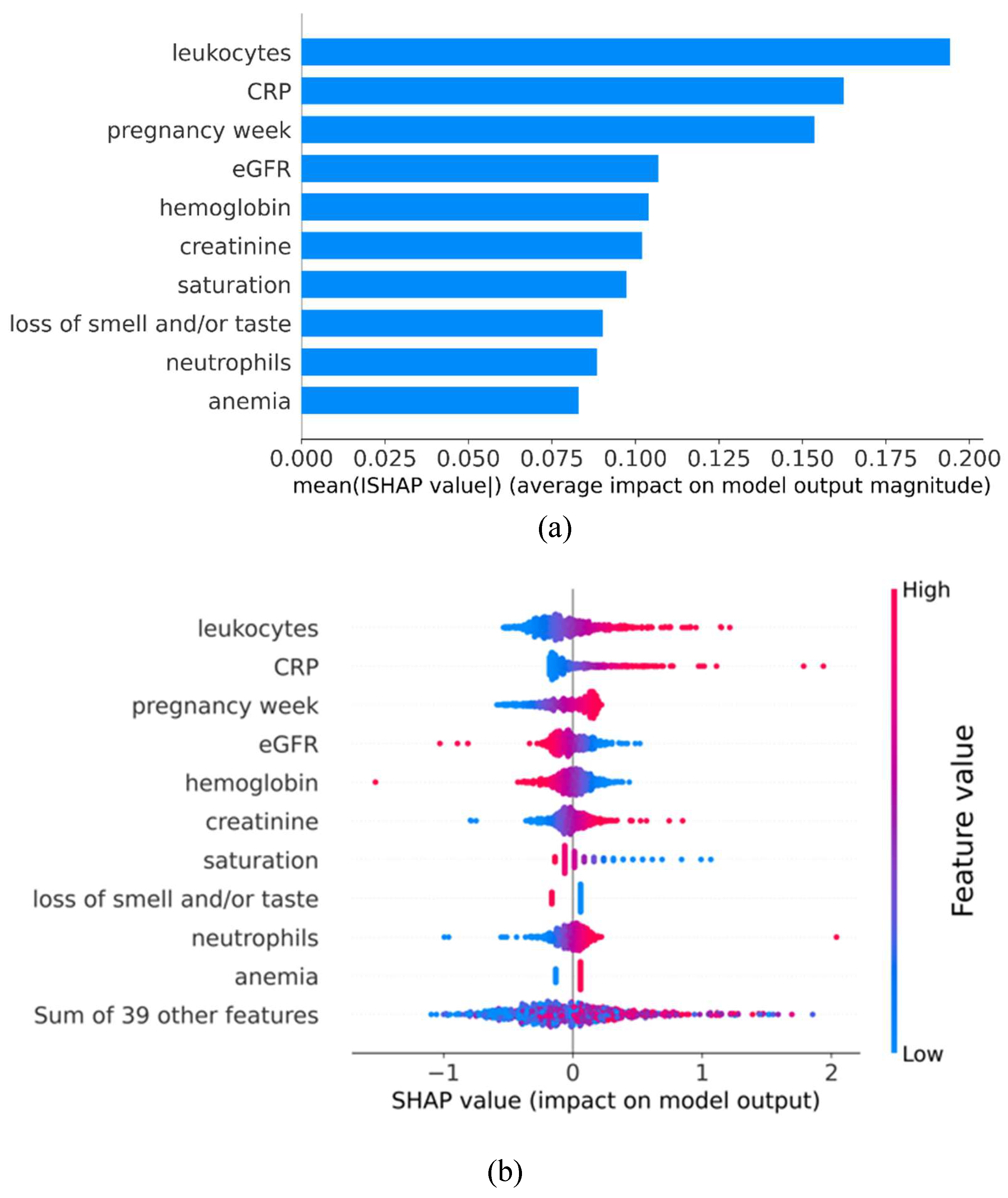

3.3. Impact Direction and Importance of Each Feature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Shevlin, M.; Gibson-Miller, J.; Hartman, T.K.; Hyland, P.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; et al. Monitoring the psychological, social, and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the population: Context, design and conduct of the longitudinal COVID-19 psychological research consortium (C19PRC) study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 30, e1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, P.; Murdoch, D.R. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. 395, 2020; 395, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, D.A.; Mattern, J.; Carlin, A.; Cordier, A.-G.; Maillart, E.; El Hachem, L.; El Kenz, H.; Andronikof, M.; De Bels, D.; Damoisel, C.; et al. Are clinical outcomes worse for pregnant women at ≥20 weeks’ gestation infected with coronavirus disease 2019? A multicenter case-control study with propensity score matching. 2020, 223, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Mappa, I.; Maqina, P.; Bitsadze, V.; Khizroeva, J.; Makatsarya, A.; D’antonio, F. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second half of pregnancy on fetal growth and hemodynamics: A prospective study. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwangbo, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.; Oh, B.; Moon, M.K.; Kim, S.-W.; Park, T. Machine learning models to predict the maximum severity of COVID-19 based on initial hospitalization record. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 1007205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga-Sainz, L.M.; Sarria-Santamera, A.; Martínez-Alés, G.; Quintana-Díaz, M. New Approach to Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Complex Tertiary Care Medical Center in Madrid, Spain. Disaster Med. Public Heal. Prep. 2021, 16, 2097–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Sabitova), A.K.; Ortega, M.-A.; Ntegwa, M.J.; Sarria-Santamera, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to and delivery of maternal and child healthcare services in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1346268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laatifi, M.; Douzi, S.; Bouklouz, A.; Ezzine, H.; Jaafari, J.; Zaid, Y.; El Ouahidi, B.; Naciri, M. Machine learning approaches in Covid-19 severity risk prediction in Morocco. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ruan, L.; Li, D.; Lu, C.; Huang, L.; the National Traditional Chinese Medicine Medical Team. Comparing different machine learning techniques for predicting COVID-19 severity. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2022, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, P.; Schmitt, V.; Zimmermann, J.; Häger, L.; Göpel, S.; Schenkel-Häger, C.; Kschischo, M. Machine learning models for predicting severe COVID-19 outcomes in hospitals. Informatics Med. Unlocked 2023, 37, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda RO, Hart PE, Stork DG. Pattern Classification. New York: Wiley; 2001.

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH, The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer Series in Statistics; 2009.

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Decision-Theoretic Generalization of On-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the KDD ’16: 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.W. Classification by multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, SM, Lee, SI. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017;30.

- El-Kady, A.M.; Aldakheel, F.M.; Allemailem, K.S.; Almatroudi, A.; Alharbi, R.D.; Al Hamed, H.; Alsulami, M.; A Alshehri, W.; El-Ashram, S.; Kreys, E.; et al. Clinical Characteristics, Outcomes and Prognostic Factors for Critical Illness in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, ume 15, 6945–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Cheng, Y. Blood Test Results of Pregnant COVID-19 Patients: An Updated Case-Control Study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 560899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendra, S. Spectrum of hematological changes in COVID-19. . 2022, 12, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Kovalic, A.J.; Graber, C.J. Prognostic Value of Leukocytosis and Lymphopenia for Coronavirus Disease Severity. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1839–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.N.; Abdi, A.; Velpuri, P.; Patel, P.; DeMarco, N.; Agrawal, D.K.; Rai, V. A Review of Hematological Complications and Treatment in COVID-19. Hematol. Rep. 2023, 15, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wool, G.D.; Miller, J.L. The Impact of COVID-19 Disease on Platelets and Coagulation. Pathobiology 2020, 88, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannis, D.; Ziogas, I.A.; Gianni, P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. 127, 1043; 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; He, M.; Zhou, M.; Lai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Association of C-reactive protein with mortality in Covid-19 patients: a secondary analysis of a cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeagwulonu RC, Ugwu NI, Ezeonu CT, Ikeagwulonu ZC, Uro-Chukwu HC, Asiegbu UV, Obu DC, Briggs DC. C-Reactive Protein and Covid-19 Severity: A Systematic Review. West Afr J Med. 2021;38(10):1011-1023.

- Vasileva, D.; Badawi, A. C-reactive protein as a biomarker of severe H1N1 influenza. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 68, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plebani, M. Why C-reactive protein is one of the most requested tests in clinical laboratories? cclm 2023, 61, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, R.; Asano, H.; Umazume, T.; Takaoka, M.; Noshiro, K.; Saito, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Chiba, K.; Nakakubo, S.; Nasuhara, Y.; et al. C-reactive protein level predicts need for medical intervention in pregnant women with SARS-CoV2 infection: A retrospective study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.R.; Oakley, E.; Grandner, G.W.; Rukundo, G.; Farooq, F.; Ferguson, K.; Baumann, S.; Waldorf, K.M.A.; Afshar, Y.; Ahlberg, M.; et al. Clinical risk factors of adverse outcomes among women with COVID-19 in the pregnancy and postpartum period: a sequential, prospective meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 228, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, G.; Gao, Y.; Liao, J.; Yu, J.; Luo, X.; Qi, H. Changes in physiology and immune system during pregnancy and coronavirus infection: A review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 255, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ismail, L.; Taha, M.J.J.; Abuawwad, M.T.; Al-Bustanji, Y.; Al-Shami, K.; Nashwan, A.; Yassin, M. COVID-19 and Anemia: What Do We Know So Far? Hemoglobin 2023, 47, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Goyal, H.; Haghbin, H.; Lee-Smith, W.M.; Gajendran, M.; Perisetti, A. The Association of “Loss of Smell” to COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Med Sci. 2020, 361, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purja, S.; Shin, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, E. Is loss of smell an early predictor of COVID-19 severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2021, 44, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berumen-Lechuga, M.G.; Leaños-Miranda, A.; Molina-Pérez, C.J.; García-Cortes, L.R.; Palomo-Piñón, S. Risk Factors for Severe–Critical COVID-19 in Pregnant Women. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafat, E.; Prasad, S.; Birol, P.; Tekin, A.B.; Kunt, A.; Di Fabrizio, C.; Alatas, C.; Celik, E.; Bagci, H.; Binder, J.; et al. An internally validated prediction model for critical COVID-19 infection and intensive care unit admission in symptomatic pregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 226, 403.e1–403.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmola, A.; Albasheer, O.; Kariri, A.; Akkam, F.M.; Hakami, R.; Essa, S.; Jali, F.M. Characteristics and Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease- 2019 Among Pregnant Women in Saudi Arabia; a Retrospective Study. Int. J. Women's Heal. 16. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.S.; Garg, S.; Fink, R.V.; Russell, M.L.; Regan, A.K.; A Katz, M.; Booth, S.; Chung, H.; Klein, N.P.; Kwong, J.C.; et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalizations for Acute Respiratory or Febrile Illness and Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Among Pregnant Women During Six Influenza Seasons, 2010–2016. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 221, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vouga, M.; Favre, G.; Martinez-Perez, O.; Pomar, L.; Acebal, L.F.; Abascal-Saiz, A.; Hernandez, M.R.V.; Hcini, N.; Lambert, V.; Carles, G.; et al. Maternal outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 severity among pregnant women. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, K.; Tsuzuki, S.; Akiyama, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Asai, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Iwamoto, N.; Funaki, T.; Yamada, M.; Ozawa, N.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Pregnant Women: A Propensity Score–Matched Analysis of Data From the COVID-19 Registry Japan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e397–e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R.; Ghosh, R.; Gutierrez, J.P.; Gutierrez, J.P.; Ascencio-Montiel, I.d.J.; Ascencio-Montiel, I.d.J.; Juárez-Flores, A.; Juárez-Flores, A.; Bertozzi, S.M.; Bertozzi, S.M. SARS-CoV-2 infection by trimester of pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes: a Mexican retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e075928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, T.; Hasegawa, J.; Sekizawa, A.; Ikeda, T.; Ishiwata, I.; Kinoshita, K. Risk factors for severe disease and impact of severity on pregnant women with COVID-19: a case–control study based on data from a nationwide survey of maternity services in Japan. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e068575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffl, H.; Lang, S.M. Long-term interplay between COVID-19 and chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cei, F.; Chiarugi, L.; Brancati, S.; Montini, M.S.; Dolenti, S.; Di Stefano, D.; Beatrice, S.; Sellerio, I.; Messiniti, V.; Gucci, M.M.; et al. Early reduction of estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) predicts poor outcome in acutely ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients firstly admitted to medical regular wards (eGFR-COV19 study). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113454–113454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirijello, A.; Piscitelli, P.; de Matthaeis, A.; Inglese, M.; D’errico, M.M.; Massa, V.; Greco, A.; Fontana, A.; Copetti, M.; Florio, L.; et al. Low eGFR Is a Strong Predictor of Worse Outcome in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-X.; Xu, W.; Huang, C.-L.; Fei, L.; Xie, X.-D.; Li, Q.; Chen, L. Acute cardiac injury and acute kidney injury associated with severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19. 25, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, T.; Miyashita, H.; Yamada, T.; Harrington, M.; Steinberg, D.; Dunn, A.; Siau, E. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 36, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Navarro, A.; Mittmann, L.; Thieme, C.J.; Anft, M.; Paniskaki, K.; Doevelaar, A.; Seibert, F.S.; Hoelzer, B.; Konik, M.J.; Berger, M.M.; et al. Impact of low eGFR on the immune response against COVID-19. J. Nephrol. 2022, 36, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossetta, G.; Fantone, S.; Muti, N.D.; Balercia, G.; Ciavattini, A.; Giannubilo, S.R.; Marzioni, D. Preeclampsia and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a systematic review. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaeepour, N.; Ganio, E.A.; Mcilwain, D.; Tsai, A.S.; Tingle, M.; Van Gassen, S.; Gaudilliere, D.K.; Baca, Q.; McNeil, L.; Okada, R.; et al. An immune clock of human pregnancy. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinder, J.M.; Turner, L.H.; Stelzer, I.A.; Miller-Handley, H.; Burg, A.; Shao, T.-Y.; Pham, G.; Way, S.S. CD8+ T Cell Functional Exhaustion Overrides Pregnancy-Induced Fetal Antigen Alloimmunization. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107784–107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, W.; Farooqui, N.; Zahid, N.; Ahmed, K.; Anwar, M.F.; Rizwan-Ul-Hasan, S.; Hussain, A.R.; Sarría-Santamera, A.; Abidi, S.H. Association of Interferon Lambda 3 and 4 Gene SNPs and Their Expression with COVID-19 Disease Severity: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, ume 16, 6619–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, L.A.S.; Eldesouki, R.E.; Sachithanandham, J.; Yin, A.; Fall, A.; Morris, C.P.; Norton, J.M.; Abdullah, O.; Dhakal, S.; Barranta, C.; et al. Reduced control of SARS-CoV-2 infection associates with lower mucosal antibody responses in pregnancy. mSphere 2024, 9, e0081223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

i Chinn J, Sedighim S, Kirby KA, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Women With COVID-19 Giving Birth at US Academic Centers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2120456. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20456 |

| Trimester of gestation | ||||

| Characteristic |

1st trimester (n=73) |

2nd trimester (n=309) |

3rd trimester (n=770) |

ICU Admission (n=138) |

| Feature | ||||

| Age | 30.1 | 29.9 | 29.6 | 31 |

| Blood type | ||||

| A | 13 | 73 | 252 | 39 |

| AB | 5 | 27 | 67 | 9 |

| B | 20 | 96 | 225 | 34 |

| O | 28 | 106 | 251 | 31 |

| Rh factor | ||||

| - | 4 | 16 | 29 | 5 |

| + | 62 | 286 | 765 | 108 |

| BMI | 23.69 | 25.09 | 26.78 | 29.06 |

| Days of admission after symptoms onset | 4.22 | 4.43 | 4.70 | 5.86 |

| Length of hospital stay | 7.88 | 8.40 | 6.74 | 9.00 |

| Obstetric history | ||||

| Number of children | 1.42 | 1.20 | 1.76 | 1.96 |

| Number of pregnancies | 2.69 | 2.65 | 2.81 | 2.97 |

| Number of deliveries | 1.28 | 1.21 | 1.74 | 2.04 |

| Multiple gestation | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| Haemoglobin | 11.9 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 9.9 |

| Leucocytes | 6.89 | 8.44 | 9.18 | 12.5 |

| Neutrophils | 71.85 | 78.38 | 79.00 | 85 |

| Lymphocytes | 22.77 | 16.59 | 17.12 | 13.1 |

| Platelets | 202.8 | 213.7 | 220.6 | 247.5 |

| APTT | 29.20 | 31.57 | 31.91 | 35.99 |

| ALT | 29.37 | 38.30 | 22.92 | 36.00 |

| ACT | 27.40 | 35.98 | 29.57 | 42.00 |

| Comorbidities and complications | ||||

| Preeclampsia | 0 | 4 | 27 | 12 |

| Small for gestational age | 0 | 2 | 17 | 2 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 0 | 0 | 17 | 3 |

| Hypertension | 1 | 20 | 76 | 25 |

| Hyperglycaemia | 3 | 58 | 116 | 29 |

| Gestational diabetes | 1 | 11 | 33 | 13 |

| Anaemia | 17 | 184 | 636 | 108 |

| Pneumonia | 35 | 168 | 499 | 89 |

| Clinical symptoms and severity of COVID-19 | ||||

| Fever | 39 | 140 | 274 | 47 |

| Cough | 64 | 292 | 689 | 102 |

| Weakness | 71 | 307 | 802 | 124 |

| Sore throat | 35 | 205 | 480 | 55 |

| Shortness of breath | 16 | 69 | 183 | 45 |

| Myalgia | 20 | 116 | 259 | 48 |

| Loss of smell and/or taste | 38 | 116 | 218 | 32 |

| Runny nose | 53 | 239 | 607 | 77 |

| Diarrhoea | 6 | 13 | 12 | 0 |

| Chest discomfort | 14 | 75 | 185 | 37 |

| Sweating | 3 | 10 | 34 | 7 |

| ICU Admission | 0 | 14 | 121 | |

| Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | Specificity | G-mean | F1-score | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.866 | 0.389 | 0.600 | 0.896 | 0.733 | 0.472 | 0.845 |

| Predicted | |||

| Actual | Negative | Positive | |

| Negative | True Negative: 283 | False Positive: 33 | |

| Positive | False Negative: 14 | True Positive: 21 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).