1. Introduction

Primary liver cancer (PLC) is a significant health problem worldwide. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), there were approximately 870,000 new cases of liver cancer and 760,000 deaths globally in 2022 [

1]. PLC mainly comprises heterogeneous hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, 75 ~ 85%), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC, 10 ~ 15%), and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (CHC, 1 ~ 3%) [

2]. It is estimated that PLC will rank the fifth in cancer mortality among men and the seventh among women. Approximately 12.51% of deaths from PLC occur in young individuals. In recent years, the incidence of PLC has continued to rise at a faster rate than other cancers [

3,

4,

5]. Projections indicate that the number of PLC cases is estimated to exceed 1 million by 2025 [

5]. In addition, PLC typically has no symptoms in the early stage, and most cases are diagnosed at the intermediate or late stages [

6]. It not only causes severe damage to liver function but also lead to metastasis to distant organs [

7]. Therefore, there has been an ongoing effort to seek more effective screening, diagnostic and treatment strategies to improve the prognosis of this malignant tumor.

However, effective biomarkers for monitoring and identifying early-stage PLC are still lacking. Most serum biomarkers are proteins such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), demonstrate low sensitivity and specificity for the early detection of PLC [

8,

9]. The diagnosis of early-stage PLC remains challenging due to the presence of various complications associated with liver cancer, coupled with the limited efficacy of many biomarkers [

10]. To date, numerous biomarkers associated with PLC progression and aggressiveness have been proposed, but most have shown to be of little practical utility. Furthermore, the development and progression of liver cancer are influenced by various factors. Exploring the key molecular mechanisms that drive PLC development and identifying relevant therapeutic targets are equally important endeavors. Thus, enhancing our understanding of the interactions between liver cancer cells and their adjacent environment is not only crucial for the clinical diagnosis of PLC but also essential for developing more effective treatment strategies. This presents new challenges in the search for novel biomarker and molecular target with prognostic potential and therapeutic guidance [

11].

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the most abundant family of membrane proteins encoded by the human genome, playing a crucial role in eliciting cellular signaling and participating in virtually all physiological processes [

12]. GASP1 is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor associated sorting protein family, and its C-terminus contains a repetitive sequence composed of 15 amino acids, known as the GASP motif. The GASP motif directly binds to the intracellular domain of GPCRs, forming a stable complex. This binding may induce the conformation of GPCRs, thereby influencing its endocytosis, sorting, or signal transduction capacity. GASP1 plays a critical role in various cancers, exhibiting significant overexpression in brain, pancreatic, breast, thyroid, lung and prostate cancers. Importantly, GASP1 expression levels are strongly associated with increased tumor malignancy and poorer patient prognosis [

13,

14,

15]. Many studies have demonstrated that GASP1 has emerged as a crucial molecule in tumorigenesis and exhibits multifaceted roles in various malignant tumors. Mechanistic studies have revealed its involvement in promoting the proliferative and metastatic potential of tumor cells, particularly in breast cancer, where its activity appears to be regulated by MDM2-mediated regulatory pathways [

16,

17]. These joint findings position GASP1 as a promising dual biomarker -- demonstrating diagnostic potential in serum-based assays and emerging as a therapeutic target. There is limited information available regarding the clinical significance of GASP1 in PLC, highlighting the need for further research to explore its potential value the screening and treatment of PLC.

In this study, we aimed to explore the expression of GASP1 in PLC center tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues, and analyzed the clinicopathological associations between GASP1 and PLC. The findings of this study may provide a valuable research foundation and novel insights for future investigations into GASP1-related PLC diagnostics, as well as guidance for immunotherapy strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Specimens

This study was conducted in Beijing YouAn Hospital, Beijing, China. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing YouAn Hospital, Beijing, China and with written informed consent from all participants. It conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 2004 Declaration of Helsinki. Based on the surgical expertise at Xuanwu Hospital, the following inclusion criteria were defined: (1) The patient is generally in good condition, without organic diseases affecting the heart, lung, brain and kidney; (2) According to the Child-Pugh liver function classification standard, the liver function prior to the operation was grade A, or it was originally grade B but restored to grade A after medical treatment; (3) No large amounts of ascites and no abnormalities in coagulation function; (4) No tumor thrombosis in the portal vein or in the bile duct before surgery if the tumor is malignant. And the exclusion criteria are: (1) The patient had severe ascites, coagulation disorders or portal vein thrombosis; (2) Combined organ resection is required if the tumor had infiltrated adjacent organs or the patients were complicated with diseases of extrahepatic organs. A total of 12 patients with PLC were recruited from Xuanwu Hospital, Beijing, China between September, 2024 and April, 2025. Paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues (collected from more than 2 cm away from the cancer tissue) were preserved simultaneously. Fresh PLC tissue samples were processed within 15 min of surgical removal and placed into RNase Free tubes containing RNALater™ RNA Stabilization Reagent for Animal Tissue (Beyotime, China). These samples were then frozen and stored at -80℃ for reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction ( RT-qPCR ). All pathological reports were issued and validated by the Department of Pathology at Xuanwu Hospital, Beijing, China. Routine clinical and pathological data were collected and analyzed. The detailed clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are presented in

Table 1.

2.2. RNA Isolation

A tissue sample weighing 10-20 mg was placed in a grinding tube and processed using a grinder (Servicebio, China). The grinding conditions were set as follows: 60 seconds of grinding followed by a 15-second pause, repeated 8 times, while maintaining a temperature of 4°C. Total RNA was extracted from the center tissue and adjacent non-tumor tissue of tumors resected from patients with PLC, utilizing the RNAprep Pure Tissue kit (TIANGEN, Beijing) in according with the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration was measured using a quantitative nucleic acid meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The RNA concentration must exceed 20 ng/ul, exhibit an absorbance close to 0 at 230 nm, and have an A260/A280 ratio ranging from 1.8 to 2.1.

2.3. RT-qPCR

cDNA was synthesized from 1000 ng of RNA using Quantscript RT Kit (TIANGEN,Beijing). The reaction volume was 20 ul. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction ( qPCR ) was performed using an ABI ViiATM 7 Real-Time Fluorescence PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) and SYBR Green PCR Premix HS Taq (Real Time) (Genview, Beijing), with β-actin as an internal reference. The reaction volume was 25 ul. The optimized PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s (all products are less than 500 bp). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co. The primers used for the qPCR reaction were as follows: GASP1, forward: 5'-AGTACTGACAAGTGGAGAGGC-3’and reverse: 5'-AAGGCCAAGGCAATACCTGT-3’; β-actin, forward: 5'-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3’and reverse: 5'-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3’. The data were analyzed according to the 2-∆∆CT method and were normalized to β-actin expression in each sample. All of the experiments were performed in quadruplicate.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp.) and plots were performed using GraphPad prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Wilcoxons rank sum test employed to compare the GASP1 expression between PLC center tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues. Fisher's exact test was utilized to evaluate the variation between clinicopathological factors of PLC and GASP1 expression. Spearman's rank correlation analysis was employed to examine relationships between continuous clinicopathological factors and GASP1 expression levels, while Kendall's tau-b correlation analysis was utilized to assess associations between ordinal clinicopathological factors and GASP1 expression status. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of GASP1 mRNA Expression

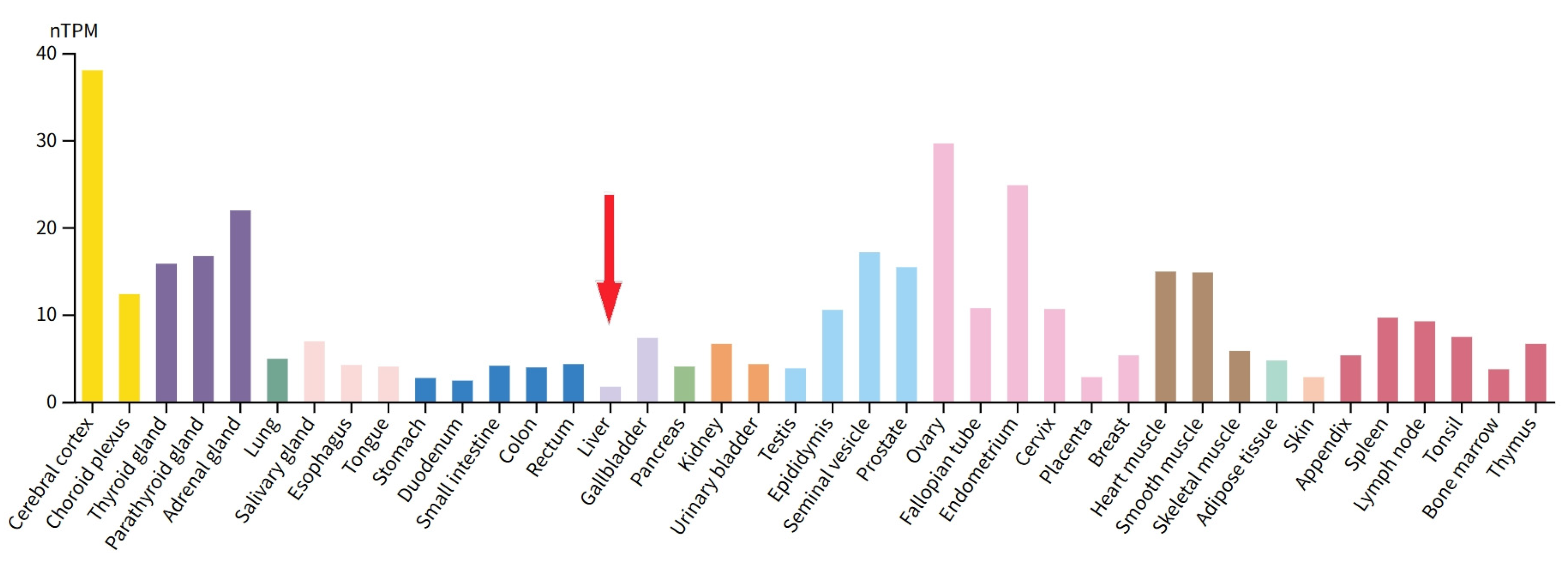

To verify the expression of GASP1 in PLC, we quantified it at the transcriptional level using RT-qPCR. Since GASP1 RNA levels are extremely low in liver tissue, it was difficult for us to perform RNA extraction (

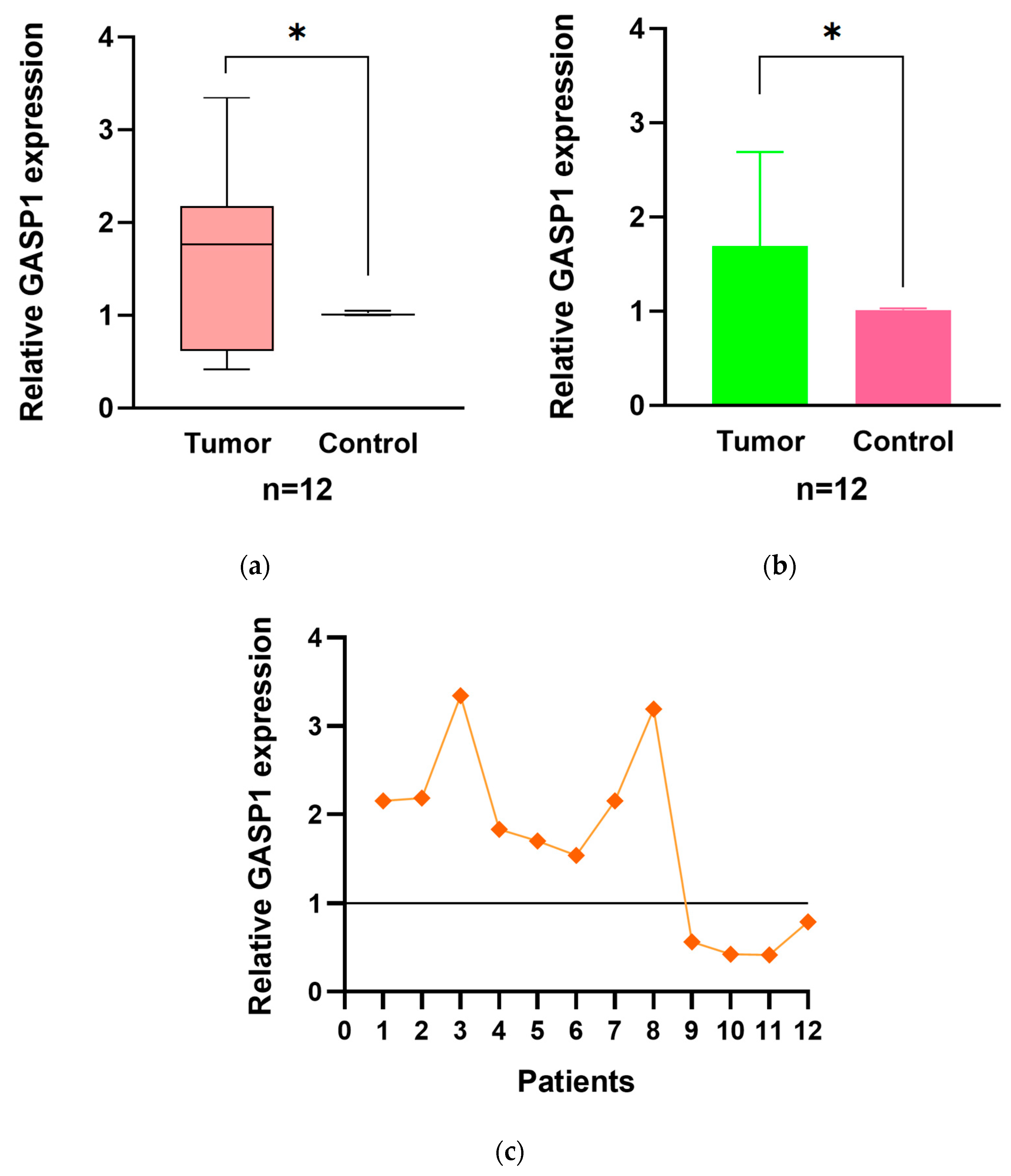

Figure 1). The mRNA levels of GASP1 were analyzed in 12 PLC tumor center tissue samples along with their paired adjacent non-tumor tissue samples. We found that GASP1 mRNA in the tumor center was higher than those in the adjacent non-tumor tissue in 8 out of 12 patients (66.7 %; P<0.05;

Figure 2).

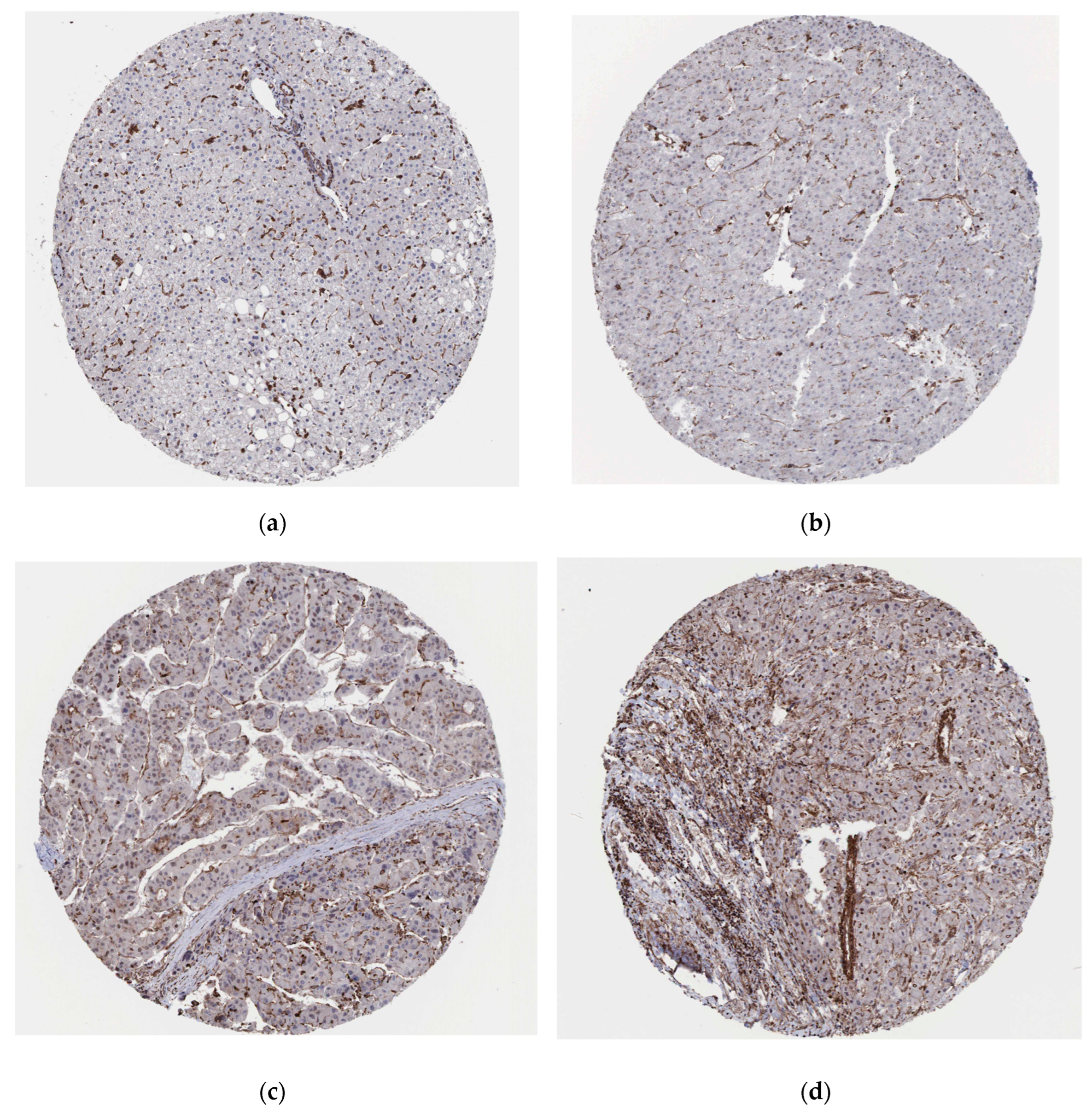

We explored the expression of GASP1 in normal liver tissues and liver cancer tissues on the Human Protein Atlas website (

www.proteinatlas.org). GASP1 expression is not detected in hepatocytes of normal liver tissue (

Figure 3 (a)). The protein expression of GASP1 varied in liver cancer tissues from different patients or at different sites in the same patient. In some patients, the tumor cells of liver cancer tissues were undetectable for GASP1 expression and their test results were negative (

Figure 3 (b)). Some patients have weak or moderate expression of GASP1 in tumor cells of liver cancer tissues (

Figure 3 (c), (d)). This is consistent with our findings.

3.2. Relationship Between GASP1 Expression and Clinicopathological Characteristics

To elucidate the role of GASP1 in PLC, we investigated the correlation between GASP1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics in PLC patients. Using the GASP1 expression levels in each patient's own adjacent non-tumor tissue as a baseline, we categorized tumor center tissue GASP1 expression into high and low expression groups, with 8 cases in the high expression group and 4 cases in the low expression group. Fisher's exact test showed that the expression of GASP1 was significantly associated with lymphocyte infiltration (P<0.05;

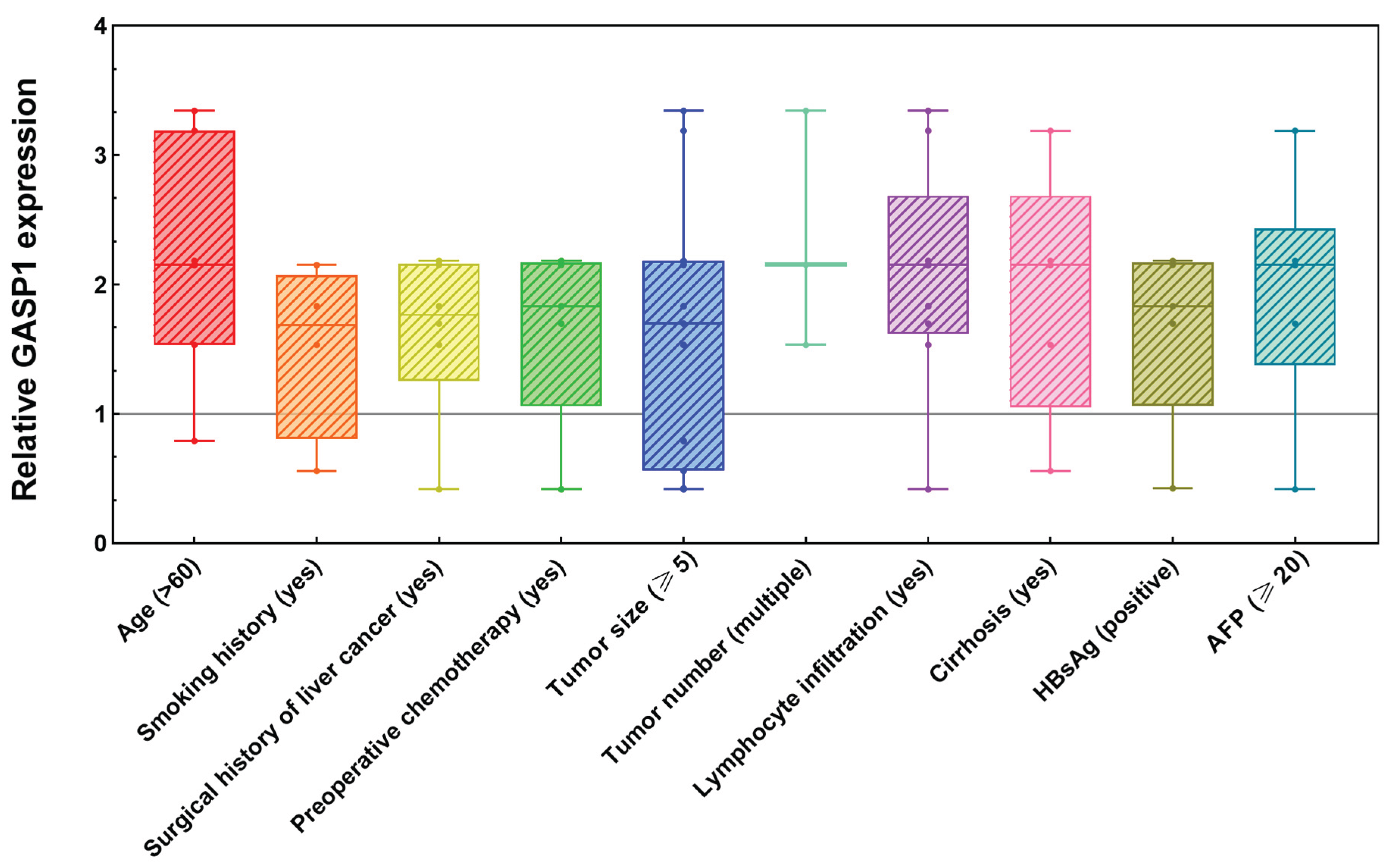

Table 1). By contrast, other clinicopathological characteristics including age, gender, tumor size, differentiation grade, microvascular invasion, and AFP levels were not found to be associated with GASP1 expression. Moreover, we conducted a comparative analysis of GASP1 mRNA expression in tumor core tissues versus adjacent non-tumor liver tissues (normalized to 1) across various clinicopathological factors. Notably, the cohort exhibited elevated GASP1 expression in patients with the following characteristics: age >60 years, smoking history, surgical history of liver cancer, preoperative chemotherapy, tumor size ≥5 cm, multiple tumors, lymphocyte infiltration, liver cirrhosis, HBsAg positivity, or serum AFP levels ≥20 ng/ml (

Figure 4). This widespread up-regulation suggests a potential pathophysiological role for GASP1 in hepatocarcinogenesis under these clinical conditions. Additionally, among the 9 PLC patients with lymphocyte infiltration, 6 were hepatitis B virus (HBV) patients or HBV carriers (

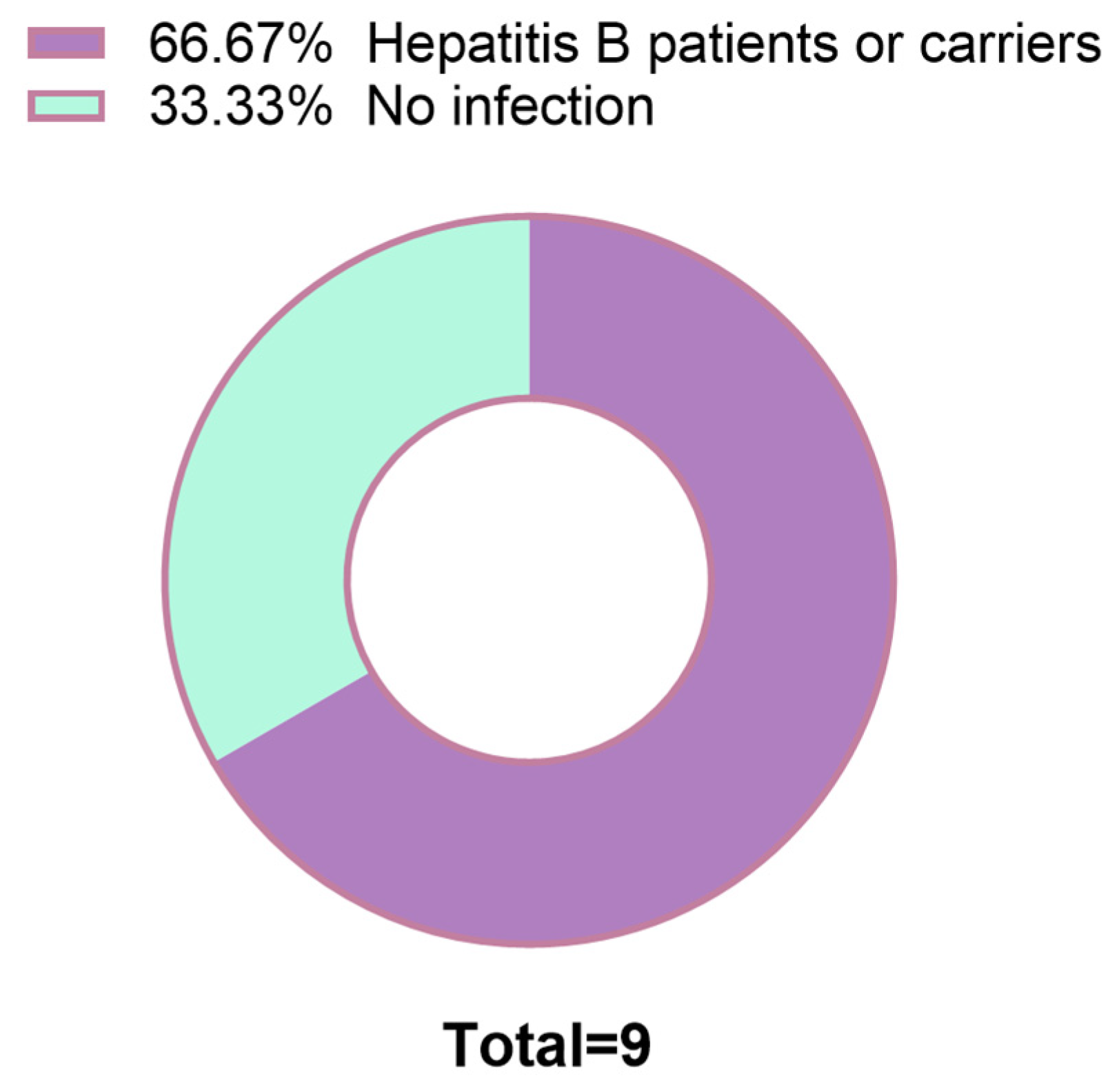

Figure 5). These findings suggest that GASP1 expression may be specifically linked to lymphocyte infiltration in PLC, particularly in patients with HBV infection.

To further elucidate the relationships between clinicopathological factors and GASP1 expression, we conducted correlation analyses. Spearman's rank correlation analysis revealed that among continuous clinicopathological variables, GASP1 expression levels exhibited significant negative correlations with HBsAb, TBIL, DBIL, and IBIL (all P<0.05;

Table 2). Conversely, no significant correlations were identified between GASP1 expression and other continuous factors including age, tumor number, HBsAg, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBcAb, CEA, AFP, GGT, CA 19-9, ALT, AST, and albumin levels (all P>0.05;

Table 2). Kendall's tau-b correlation analysis demonstrated that GASP1 expression status exhibited a significant positive correlation with lymphocyte infiltration (all P<0.05;

Table 3). However, no statistically significant associations were observed between GASP1 expression and other categorical variables, including gender, smoking history, surgical history of liver cancer, preoperative chemotherapy, tumor differentiation grade, tumor size, microvascular invasion, and liver cirrhosis (all P>0.05;

Table 3).

4. Discussion

GPCRs represent one of the most abundant receptor networks encoded by nearly 4% of the human genome [

18]. These GPCRs regulate a wide range of physiological processes including cellular proliferation, immune response, hormone signaling and nerve conduction [

19]. GPCRs play a crucial role in the migration and activation of immune cells and have been extensively targeted pharmacologically in many pathologies such as cancer [

19,

20]. There are over 800 proteins belonging to this receptor superfamily, and these GPCRs are tightly regulated by a large number of GPCR-interacting proteins. One such interacting protein is GASP1, which encodes a member of the G protein-coupled receptor-associated sorting protein family [

21]. GASP1 encodes a member of the G protein-coupled receptor-associated sorting protein family. It has been reported that this family is primarily expressed in tumor epithelium and glioma cells transformed by brain tumors, where it regulates lysosomal sorting, receptor recycling, and the functional down-regulation of various GPCRs [

22]. Recent clinical research has shown that GASP1 enhanced signal transduction by targeted degradation of cell surface receptors or promotion of endosome formation, showing significant signal amplification. It has been observed that the serum concentration of GASP1 in patients with liver cancer, breast cancer and lung cancer is 4-7 times higher than that in healthy individuals. This indicates that GASP1 may have potential clinical value as a broad-spectrum tumor biomarker [

13].

PLC is a major malignant tumor with high mortality rate. Although the treatment has made progress, its 5-year survival rate remains very low. The main challenges include limited early detection, immunosuppression microenvironment and so on. Therefore, identifying reliable biomarkers is crucial for enhancing early diagnosis, prognosis and personalized intervention. Easily detectable liver cancer biomarkers with high specificity and sensitivity could improve disease diagnosis and prognosis. More importantly, biomarkers involved in tumor development may become critical therapeutic targets for anti-tumor therapy [

23]. Consequently, the discovery and validation of novel dual biomarkers for PLC is of utmost importance.

Our study focused on the expression levels of GASP1 mRNA in PLC tumor center tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues, aiming to elucidate its potential role as a biomarker. The results demonstrated a significant up-regulation of GASP1 mRNA in PLC tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues (P<0.05), suggesting its involvement in PLC tumorigenesis. Clinically, we assessed GASP1 expression among 12 patients with PLC. The results revealed that a high GASP1 expression was strongly associated with lymphocyte infiltration (P<0.05). Lymphocyte infiltration is a common immune response of the body's immune system to tumors, infections, or injuries, referring to the process by which lymphocytes such as T-cells, B-cells, and NK-cells, migrate from the bloodstream to affected tissues. In cancer, the intensity, type, and functional status of lymphocyte infiltration significantly influence tumor progression, treatment response, and prognosis [

24]. Lymphocyte infiltration and the tumor microenvironment (TME) are engaged in a dynamic interplay, jointly determining the immune phenotype of the tumor and its therapeutic response. Therefore, the high expression of GASP1 suggests a close association with TME [

25]. G protein-coupled chemokine receptors and their ligands, namely chemokines and their receptors are critical for the recruitment of anti-tumor immune effector cells by regulating the migration of immune cells to the TME. It was found that multiple chemokine mRNA levels were significantly up-regulated in high GASP1 subtypes and positively correlated with the expression of GASP1 [

26]. GASP1 may promote the formation of immune-activated TME through up-regulation of these molecules to enhance the recruitment of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs), thus having a positive impact on the anti-tumor immune response of PLC [

27]. Further analysis showed that the abundance of TILs was higher in the GASP1 high expression group, and GASP1 expression was positively correlated with these immune cells, emphasizing its potential as a possible immunotherapeutic target [

26]. In contrast, other clinicopathological characteristics including age, gender, tumor size, differentiation grade, microvascular invasion and AFP levels were not associated with GASP1 expression. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that GASP1 is widely upregulated in PLC patientswith combined risk factors such as age ≥60 years, smoking history, surgical history of liver cancer, preoperative chemotherapy, tumor size ≥5 cm, multifocal lesions, lymphocytic infiltration, liver cirrhosis, HBsAg positivity, or serum AFP levels ≥20 ng/ml. This comprehensive profile of clinical and pathological parameters suggests a potential prognostic significance for GASP1 overexpression in high-risk PLC cohorts. So far, since AFP was introduced as a diagnostic biomarker for PLC, its practicability has been challenged. Its specificity is weakened by its increase in other diseases, which make this biomarker conflict with the purpose of liver cancer screening [

8]. As the specificity of AFP increases with the change of critical value, it is easy to have false-negative or false-positive, which is not conducive to the early diagnosis and efficacy assessment of PLC [

28]. Therefore, it is particularly important to find more PLC-related biomarkers, especially those that can be detected in combination with AFP. GASP1, as a novel tumor-related gene discovered in recent years, deserves further in-depth study and exploration for its expression in PLC and its value of combined detection with AFP.

Furthermore, we observed that in patients with PLC, lymphocytic infiltration was most commonly seen in those infected with or carriers of HBV. HBV is globally recognized as the leading cause of PLC and poses a significant risk, especially in patients with non-end-stage liver disease [

29,

30]. Liver inflammation accelerates lymphocyte migration through the sinusoidal endothelium, and it is this massive infiltration of T cells that is typical of chronic hepatitis [

31]. Therefore, we proposed that in HBV-related liver cancer, the up-regulation of GASP1 expression may be intricately linked to HBV-induced immune responses and subsequent inflammatory processes. Given the significant association between GASP1 and lymphocyte infiltration, as well as its potential link to HBV infection, we hypothesize that targeted therapies against GASP1 could effectively regulate lymphocyte infiltration, thereby modulating the progression of PLC. Moreover, in most HBsAg-positive patients, there is a high expression of GASP1, suggesting that GASP1 has dual potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. Future studies could further explore the mechanism of interaction between GASP1 and HBV infection and how this interaction affects the onset, progression and prognosis of PLC.

Among the 12 patients analyzed, a statistically significant negative correlation was observed between GASP1 expression levels and HBsAb concentrations. Specifically, elevated GASP1 expression was associated with reduced HBsAb levels, suggesting an inverse relationship where increasing GASP1 corresponds to declining HBsAb. This finding implies a potential novel regulatory mechanism involving GASP1 in the context of HBV infection. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the precise molecular interactions between GASP1 and HBsAb, as well as to clarify how this dynamic influences disease progression, clinical outcomes, and therapeutic responsiveness in affected patients. Furthermore, GASP1 expression levels showed a significant inverse association with TBIL, DBIL, and IBIL concentrations. The mechanisms underlying these correlations remain elusive, highlighting a critical gap in knowledge. Future studies should prioritize elucidating the molecular pathways connecting GASP1 to bilirubin metabolism and investigating their clinical implications in hepatobiliary disorders. Consistent with expectations, GASP1 expression levels exhibited a significant positive correlation with lymphocyte infiltration, notably reinforcing its pivotal role in immune response modulation and inflammatory processes.

In summary, our study contributes to the understanding of the role of GASP1 in PLC and emphasizes the need for further investigation into its potential as a biomarker for early diagnosis and personalized treatment of PLC. By modulating GASP1 expression, it may be possible to optimize the TME, thereby enhancing more robust anti-tumor immune responses. This approach may also inform the development of advanced immunotherapeutic strategies, ultimately opening up novel therapeutic avenues and providing essential theoretical support for the creation of innovative therapeutic drugs tailored to cancer patients. Due to the very small sample size of this study, the conclusions drawn should be interpreted with caution. Future studies are necessary to validate our findings in larger populations and to explore the efficacy and safety of GASP1 as a biomarker and therapeutic target for PLC. Additionally, it is essential to explore the specific mechanisms of action of GASP1 in the TME, as well as its detailed relationship with HBV-induced immune responses. Such insights will facilitate the development of more precise and personalized immunotherapy strategies for PLC patients, ultimately leading to improved treatment efficacy and extended patient survival.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our research revealed that GASP1 was highly expressed in PLC tissues, and its expression was significantly associated with lymphocyte infiltration. Secondly, we speculate that the high expression of GASP1 may be related to factors such as age, smoking history, surgical history of liver cancer, preoperative chemotherapy, tumor size, tumor number, liver cirrhosis, HBsAg content or AFP content. Thirdly, we propose a potential association between HBV infection status and immune infiltration in PLC. Finally, we observed that GASP1 expression levels exhibited a positive correlation with lymphocyte infiltration, while demonstrating negative correlations with HBsAb, TBIL, DBIL, and IBIL levels.

These findings suggest that GASP1 could serve as a valuable addition to the current biomarkers used for the diagnosis of PLC. And they could pave the way for new approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of PLC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Q. (Wenna Qi), X.H. (Xiaodong Huang) and Y.Y. (Yang Yao); methodology, W.Q., X.H. and H.W. (Haoxuan Wang); software, W.Q., X.H. and S.Y. (Shiqi Yang); validation, W.Q. and X.H.; formal analysis, W.Q., X.H. and C.W. (Cailing Wei); investigation, W.Q., X.H. and H.W.; resources, X.W. (Xiaojun Wang), D.L. (Dongdong Lin), A.Z. (Aiying Zhang); data curation, W.Q. and X.H.; writing-original draft, W.Q. and X.H.; writing—review and editing, W.Q., X.H. and A.Z.; visualization, W.Q. and X.H.; supervision, X.W. and A.Z.; project administration, X.W. and A.Z.; funding acquisition, X.W., D.L. and A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine High-level Chinese Medicine Key Discipline Construction Project (ZNZDXK-2023002) and the Clinical Technology Innovation Project of “Yangfan” Program of Beijing Hospital Management Center (ZLRK202332).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing YouAn Hospital IRB (#LL-2022-060-K and Month 5, 2022. of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The study took a huge heart. Each of us into one, through meticulous observation and scientific analysis, concluded the clinical significance of related GASP1 gene expression and have clear understanding of this. In this, we thank all the participants and the patients and families. It has made an important contribution to the development of medical research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GASP1 |

G-protein coupled receptor-associated sorting protein 1 |

| PLC |

primary liver cancer |

| HBV |

hepatitis B virus |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| IARC |

International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| HCC |

heterogeneous hepatocellular carcinoma |

| ICC |

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

| CHC |

combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma |

| AFP |

alpha-fetoprotein |

| DCP |

des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin |

| GPCRs |

G protein-coupled receptors |

| RT-qPCR |

reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| qPCR |

quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| TME |

tumor microenvironment |

| TILs |

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes |

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–63.

- Zhou PY, Zhou C, Gan W, Tang Z, Sun BY, Huang JL, et al. Single-cell and spatial architecture of primary liver cancer. Commun Biol. 2023, 6, 1181.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34.

- Sia D, Villanueva A, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Liver Cancer Cell of Origin, Molecular Class, and Effects on Patient Prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2017, 152, 745–61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danpanichkul P, Aboona MB, Sukphutanan B, Kongarin S, Duangsonk K, Ng CH, et al. Incidence of liver cancer in young adults according to the Global Burden of Disease database 2019. Hepatology. 2024, 80, 828–43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Wang H, Li T, Wang L, Wu X, Liu J, et al. Circulating tumor DNA/circulating tumor cells and the applicability in different causes induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2020, 44, 100516. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V, Singh R. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020, 1873, 188314.

- Piñero F, Dirchwolf M, Pessôa MG. Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Response Assessment. Cells. 2020, 9(6).

- Anuntakarun S, Khamjerm J, Tangkijvanich P, Chuaypen N. Classification of Long Non-Coding RNAs s Between Early and Late Stage of Liver Cancers From Non-coding RNA Profiles Using Machine-Learning Approach. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2024, 18, 11779322241258586.

- Mansouri V, Razzaghi M, Nikzamir A, Ahmadzadeh A, Iranshahi M, Haghazali M, et al. Assessment of liver cancer biomarkers. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2020, 13 (Suppl1), S29–s39.

- Scaggiante B, Kazemi M, Pozzato G, Dapas B, Farra R, Grassi M, et al. Novel hepatocellular carcinoma molecules with prognostic and therapeutic potentials. World J Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 1268–88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhudia N, Desai S, King N, Ancellin N, Grillot D, Barnes AA, et al. Author Correction: G Protein-Coupling of Adhesion GPCRs ADGRE2/EMR2 and ADGRE5/CD97, and Activation of G Protein Signalling by an Anti-EMR2 Antibody. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 5097. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng X, Chang F, Zhang X, Rothman VL, Tuszynski GP. G-protein coupled receptor-associated sorting protein 1 (GASP-1), a ubiquitous tumor marker. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012, 93, 111–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong Y, Torres-Luna C, Tuszynski G, Siderits R, Chang FN. Differentiating Thyroid Follicular Adenoma from Follicular Carcinoma via G-Protein Coupled Receptor-Associated Sorting Protein 1 (GASP-1). Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15(13).

- Torres-Luna C, Wei S, Bhattiprolu S, Tuszynski G, Rothman VL, McNulty D, et al. G-Protein-Coupled Receptor-Associated Sorting Protein 1 Overexpression Is Involved in the Progression of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, Early-Stage Prostatic Malignant Diseases, and Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16(21).

- Zheng X, Chang F, Rong Y, Tuszynski GP. G-protein coupled receptor-associated sorting protein 1 (GASP-1), a ubiquitous tumor marker, promotes proliferation and invasion of triple negative breast cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2022, 125, 104751. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Meng D, Wang J, Cao H, Feng P, Wu S, et al. GASP1 enhances malignant phenotypes of breast cancer cells and decreases their response to paclitaxel by forming a vicious cycle with IGF1/IGF1R signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 751. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockaert J, Dumuis A, Fagni L, Marin P. GPCR-GIP networks: a first step in the discovery of new therapeutic drugs? Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2004, 7, 649–57.

- Regan-Komito D, Valaris S, Kapellos TS, Recio C, Taylor L, Greaves DR, et al. Absence of the Non-Signalling Chemerin Receptor CCRL2 Exacerbates Acute Inflammatory Responses In Vivo. Front Immunol. 2017, 8, 1621. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007, 7, 79–94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuszynski GP, Rothman VL, Zheng X, Gutu M, Zhang X, Chang F. G-protein coupled receptor-associated sorting protein 1 (GASP-1), a potential biomarker in breast cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011, 91, 608–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whistler JL, Enquist J, Marley A, Fong J, Gladher F, Tsuruda P, et al. Modulation of postendocytic sorting of G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 2002, 297, 615–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Niu C, Yang N, Liu C, Zou SS, Zhu S. Biomarker discovery and application-An opportunity to resolve the challenge of liver cancer diagnosis and treatment. Pharmacol Res. 2023, 189, 106674.

- Whiteside TL. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Their Role in Solid Tumor Progression. Exp Suppl. 2022, 113, 89–106.

- Zhong X, He X, Wang Y, Hu Z, Huang H, Zhao S, et al. Warburg effect in colorectal cancer: the emerging roles in tumor microenvironment and therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2022, 15, 160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang T, Liu G, Zhang J, Chen S, Deng Z, Xie M. GPRASP1 is a candidate anti-oncogene and correlates with immune microenvironment and immunotherapeutic efficiency in head and neck cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2023, 52, 232–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu Y, Zeng D, Ou Q, Liu S, Li A, Chen Y, et al. Association of Survival and Immune-Related Biomarkers With Immunotherapy in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis and Individual Patient-Level Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019, 2, e196879.

- Trevisani F, D'Intino PE, Morselli-Labate AM, Mazzella G, Accogli E, Caraceni P, et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: influence of HBsAg and anti-HCV status. J Hepatol. 2001, 34, 570–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringelhan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017, 372(1732).

- Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014, 384, 2053–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oo YH, Adams DH. The role of chemokines in the recruitment of lymphocytes to the liver. J Autoimmun. 2010, 34, 45–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).