1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is known as the most common primary liver cancer, accounting for over 90 % of cases, with an increasing prevalence worldwide[

1]. Despite this, the mechanisms underlying HCC progression still remains unclear[

2,

3,

4,

5]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of RNA molecules > 200 nucleotides in length that do not encode proteins[

6,

7]. Increasing evidence suggests that mutations and dysregulation of lncRNAs affect various aspects of genome function and critical biological processes[

8]. In many malignancies, lncRNAs are dysregulated and interact with a multitude of RNAs and proteins, influencing cancer progression[

9,

10,

11]. Typically, lncRNAs function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), competitively binding with miRNAs to decrease miRNAs regulation of their target mRNAs, as observed in HCC[

12]. However, the regulatory mechanisms of lncRNA-dependent gene expression in HCC require in-depth exploration to develop promising therapeutic targets and methods.

Utilizing sample data form The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, we analyzed differentially expressed (DE) lncRNAs involved in HCC tumorigenesis, with a particular focus on the lncRNA KCNQ1 overlapping transcript 1 (KCNQ1OT1) /miR-335-5p/cell division cycle 7 (CDC7) axis. Recent studies have indicated that overexpression of KCNQ1OT1 interacts with several tumor suppressor miRNAs (including miR-148a-3p, miR-149, miR-146a-5p, miR-506, miR-504, miR-424-3p, miR-136-3, miR-139-5p, miR-223-3p and miR-375-3p) to enhance HCC progression and is associated with poor prognosis in patients[

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, miR-335-5p has been identified to negatively regulate critical pathways involved in the transport and utilization of essential compounds that are crucial for the rapid proliferation of HCC cells[

16]. Research indicates that extracellular vesicles containing miR-335-5p have the potential to decrease HCC growth and invasion both in vitro and in vivo[

17]. Notably, the role of KCNQ1OT1 in targeting miR-335-5p has not been documented.

The CDC7 protein plays a pivotal role in initiating DNA replication, S-phase checkpoints, and M-phase completion[

18]. In cancer cells, the absence of CDC7 leads to defects in S-phase progression, resulting in p53-independent apoptotic cell death[

19]. CDC7 forms a complex with dumbbell former 4 (DBF4) to create DBF4-dependent kinase (DDK), which is crucial for tumor cell survival[

20]. Highly expressed in HCC, CDC7 is significantly correlated with the survival rate of HCC patients[

21]. Nevertheless, studies on the association between miR-335-5p and CDC7 remain inconclusive.

In this study, we found that KCNQ1OT1 increased the expression of CDC7 by acting as a ceRNA to attract miR-335-5p, thereby promoting the proliferation and migration of HCC cells. Primary risk factors for HCC include chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated foods, excessive alcohol intake, and obesity. Chronic HBV infection is a major contributor to HCC in high-risk areas[

22]. Based on this, our results showed that HBV and its encoded protein HBc significantly enhanced the expression of KCNQ1OT1 and CDC7 while reducing the expression of miR-335-5p. This study provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms of HBV infection in liver cancer progression. Therefore, the KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis may be a promising therapeutic target in patients with HBV-related primary liver cancer.

3. Discussion

HCC is the most prevalent form of primary liver cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally[

1]. Despite significant efforts, our understanding of the specific mechanisms underlying HCC progression remains limited. HBV infection, a major risk factor, affects the expression and function of specific genes, contributing to liver disorders[

26]. The complex alterations caused by HBV are considered primary contributors to malignant progression and poor prognosis in HCC patients[

2]. Thus, investigating the mechanisms of HBV-mediated HCC is a focal point for future research.

Viral persistence in HBV infection arises from the virus's ability to evade the host immune system and establish covalently closed circular double-stranded DNA (cccDNA) in the nucleus of infected cells[

3]. As a transcriptional template for HBV, cccDNA encodes four overlapping open reading frames (ORFs), producing proteins including HBV core/capsid protein (HBc), HBeAg, envelope proteins (S, M, and L), nonstructural X protein (HBx), and P protein (HBp). Current evidence suggests that HBx plays a pathogenetic role in HBV-induced malignant transformation[

4,

5]. The HBc protein, encoded by the C ORF, is involved in nearly every stage of the HBV life cycle, including genome release, capsid assembly and transport, reverse transcription, and RNA metabolism[

27,

28,

29]. Emerging evidence indicates that HBc promotes malignant progression of HCC through various mechanisms, including epigenetic alterations (e.g., miRNA), cellular metabolic disorders, and resistance to apoptosis[

2]. HBc has been reported to repress the expression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in HCC synergistically with HBx[

30]. Furthermore, HBc facilitates HCC metastasis via the miR-382-5p/DLC-1 axis and may inhibit TRAIL-induced hepatocyte apoptosis by obstructing DR5 expression, contributing to chronic hepatitis and HCC development[

31,

32]. However, previous studies have primarily focused on HBx’s role in HBV malignant transformation. In this study, we demonstrate that HBc induces the KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis and promotes malignant HCC progression, enhancing our understanding of HBV-related HCC.

Growing evidence indicates that lncRNAs play a wide range of roles in chromatin modification, transcription, and post-transcriptional regulation, acting as signals, decoys, guides, scaffolds, and ceRNAs. Recent studies suggest that lncRNA-miRNA interactions are crucial regulators in various biological processes and carcinogenesis in HCC[

33]. lncRNAs typically interact with miRNAs as molecular sponges, modulating miRNAs binding to target mRNAs[

33]. For instance, the highly expressed lncRNA NEAT1 functions as a ceRNA, attracting miR-362-3p to indirectly upregulate MIOX expression, promoting ferroptosis in HCC cells[

34]. Mechanistic studies reveal that lncRNA MIAT exerts an oncogenic function in HCC by sponging miR-22-3p to upregulate SIRT1 expression[

35]. MFI2-AS1 facilitates HCC progression through a positive feedback loop involving the MFI2-AS1/miR-134/FOXM1 axis[

36]. In this study, we constructed the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network and found that KCNQ1OT1 plays an essential role in HCC progression through interactions with miR-335-5p, subsequently regulating CDC7 signaling. Furthermore, our research demonstrates that the abnormal expression of this axis in HCC is regulated by HBc, which may be a significant contributor.

KCNQ1OT1, located on chromosome 11p15.5 and spanning 91 kb[

37], is highly expressed in various malignancies and is associated with tumor growth, lymph node metastasis, survival cycle, and recurrence rate[

38]. Increasing evidence suggests that KCNQ1OT1 expression is significantly higher in HCC tissues and cell lines compared to adjacent non-carcinoma tissues and normal cell lines[

39,

40]. Cheng et al. discovered that KCNQ1OT1 acts as a molecular sponge for miR-149, regulating S1PR1 expression and influencing HCC invasion and migration[

39]. Additionally, KCNQ1OT1 regulates cyclin-dependent kinase 16 (CDK16) expression, mediating HCC progression as a ceRNA for miR-504[

41]. Dysregulation of the KCNQ1OT1/miR-148a-3p/IGF1R axis also contributes to HCC[

42].

Previous studies show that miR-335-5p negatively regulates rapid HCC cell proliferation, and extracellular vesicles carrying this miRNA can reduce cancer growth and invasion[

16,

17]. Moreover, miR-335-5p plays a role in the process by which circ_0064288 and circ_0009910 promote ROCK1 expression, facilitating HCC cell growth and migration[

43,

44]. Our research shows for the first time that KCNQ1OT1 inhibits miR-335-5p to regulate CDC7 expression.

CDC7, a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase, initiates DNA replication and is activated through its interaction with regulatory subunit DBF4[

45]. Cancer cells exhibit heightened replicative stress and may be especially sensitive to CDC7 inhibition[

45]. Elevated CDC7 expression is well recognized in a wide range of cancers (including HCC, breast cancer, and colon cancer), and is strongly associated with tumor malignancy, invasiveness, and poor prognosis[

46,

47,

48]. One study indicates that combining CDC7 inhibition with ATR-CHK1 inhibition probably shows striking synergy in suppressing HCC cell proliferation[

18]. Similarly, the synergistic inhibition of CDC7 and cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) enhances the antitumor efficacy of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in suppressing HCC cells[

49]. These studies demonstrate that CDC7 plays an integral role in HCC treatment; however, the specific mechanisms by which HBc modulates CDC7 activation and promotes HCC progression require further investigation.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the specific mechanisms by which lncRNAs contribute to HBV-related HCC progression. Key findings indicate that HBc enhances KCNQ1OT1 expression, which suppresses miR-335-5p, leading to CDC7 upregulation. We verified that HBc plays a pivotal role in promoting malignant progression in HCC by modulating the KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 signaling axis. Our findings provide novel insights into the roles of KCNQ1OT1 and CDC7, potentially aiding in the exploration of treatments for HBV-related HCC. Future studies should aim to develop specific inhibitors for this axis and assess their efficacy in clinical settings, potentially improving outcomes for patients with HBV-related HCC.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. TCGA data collection and ceRNA network construction

A total of 374 HCC tissue samples and 50 normal tissue samples were downloaded from TCGA database (

https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The DESeq2 package was used to identify DE genes. The GDCRNATools package was utilized to classify these genes into the lncRNA, miRNA, and mRNA categories. The RNA interaction network and binding sites were predicted using the ENCORI/starBase database (v2.0,

https://rnasysu.com/encori/) and the RNAhybrid software (

https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid). The final lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network was visualized using the Cytoscape software (

http://cytoscape.github.io/). Volcano plots and heatmaps were generated using the ggplot2 package. Genome Ontology (GO) annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses for DE mRNAs were conducted using the clusterProfiler package[

50]. The GEPIA 2 database (

http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) was used for survival analysis, and the UALCAN database (

https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) was used for the expression analysis of DE RNAs.

4.2. Cell culture and transfection

Human HCC cell lines, HepG2 and HepG2.215 (stably transfected HBV virus HepG2 cells), were purchased from iCell Bioscience (China). All cells in this study were cultured in high glucose DMEM (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10 % FBS (Gibco, USA), 100 μg/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco, USA). For cell transfection, cells were inoculated in plates and incubated for 16-24 h. When the cell density to reach 60-70 %, siRNA, miRNA mimics, miRNA inhibitors, or plasmids were transfected into cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo, USA).

The sequences of si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1, si-CDC7, miR-NC, miR-335-5p mimics, miR-335-5p inhibitors, and NC inhibitors were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (China). Si-NC served as a negative control for si-KCNQ1OT1 and si-CDC7. MiR-NC functioned as a negative control for miR-335-5p mimics, while NC inhibitors served as the negative control for miR-335-5p inhibitors. Plasmids were obtained from MiaoLing Bio (China), including pcDNA3.1-CDC7 (oe-CDC7) and negative control (oe-NC), HBV 1.3-mer WT replicon and its negative control pGEM-4Z, HBx-pmCherry, HBp-pmCherry, HBc-pmCherry and negative control (NC). All the related sequences are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.3. Luciferase reporter assay

The sequences containing the mutated site were inserted into the luciferase reporter gene vector pmirGLO, and mutant vectors MUT-KCNQ1OT1 and MUT-CDC7 were constructed. SMMC-7721 cells were transfected with WT-KCNQ1OT1, MUT-KCNQ1OT1, WT-CDC7, or MUT-CDC7 in combination with miR-355-5p mimics or miR-NC. After 48 h of incubation, the relative luciferase activity in each group measured. The Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay System (Beyotime, China) was used to measure luciferase activity.

4.4. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Thermo, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. High-quality total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Prime Script™ RT Master Mix Kit (TaKaRa, China). Then qRT-PCR was performed using TB Green

® Premix Ex Taq™ II (TaKaRa, China). Relative expression was calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCT method and transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression levels. Reverse transcription of miRNA was performed using the miRNA 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (Stem-loop) (Accurate Biology, China). QPCR was performed with the same kit as above, and the relative expression of miRNAs was normalized to U6. The primer sequences are listed in

Supplementary Table S2.

4.5. CCK-8 assay

After transfection, 5×103 cells per well were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Before testing, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo, Japan) was added to the each well and cells were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the light absorbance at 450 nm was measured. Cell proliferation ability in different groups was analyzed using the CCK-8 assay, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

4.6. Cell colony formation assay

Different groups of transfected HCC cells were seeded in six-well plates at 1000 cells per well. After 2 weeks, 4 % paraformaldehyde was used to fix cell colonies, then, fixed colonies were stained with crystal violet for 10-30 min. After staining, the plates were washed with distilled water and air-dried. Colonies were counted for statistical analysis.

4.7. Wound healing assay

The transfected cells were distributed in a 6-well plate and allowed to grow until reaching 80 %-90 % confluence. Scratches were created in the cell monolayer with 10 µL sterilized pipette tips. By capturing images, the width of the scratched area was measured at 0, 24, and 48 h. Image J software was used to analyze the migration distance.

4.8. Western blotting (WB)

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo, USA) supplemented with PMSF Protease Inhibitor (Thermo, USA). Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA protein quantification kit (Beyotime, China). Equal amounts of protein extract were loaded onto gels for SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA), blocked with 5 % non-fat milk for 2 h at 37 °C. The membrane was incubated with indicated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, including anti-CDC7 (Abcam, #ab229187, 1:1000) and anti-GAPDH (ZSGB-BIO, #TA-08, 1:1000). Subsequently, secondary antibody against mouse (ZSGB-BIO, #ZB-2305, 1:1000) or rabbit (ZSGB-BIO, #ZB-2301, 1:1000) was incubated for 1 h at room temperate. After washing with TBST, the membranes were visualized using ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo, USA). Data were obtained and calculated using Image Lab and ImageJ software. All blots including all replicates with clear membrane edges were provided in

Supplementary Figure S3-S9.

4.9. Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded on coverslips and grown until reaching 50 %-60 % confluence. Next, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 15 min and incubated with 0.5 % Triton X-100 for 20 min. After blocking with 5 % BSA for 45 min and incubating with anti-CDC7 (Cell Signaling Technology, #3603S, 1:100) overnight at 4 ℃, cells were then incubated with secondary fluorescence-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) (Abcam, #ab150080, 1:1000) and subsequently counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, #P0131, China). Images were captured using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (ZEISS LSM880, Germany).

4.10. Immunohistochemistry

HCC tissue samples and adjacent normal tissue samples were post fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde and prepared as 4-μm-thick sections in PBS. The slides were then placed in an oven, baked at a temperature of 60 °C for a duration of 1 h. Afterward, they were deparaffinized, and rehydrated. Heat mediated antigen retrieval was performed in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a microwave oven. After cooling to room temperature, endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating the sections with 3 % hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. Next, the sections were permeabilized in 0.5 % Triton X-100 for 20 min and blocked in 5 % BSA for 1 h. And then sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-CDC7 (Abcam, #ab229187, 1:100). After washing with PBS, each section was incubated with a mouse anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz, #sc-2357, 1:1000) secondary antibody for 45 min. Each section was washed with PBST and developed with DAB solution for 5 min. Sections were restained with hematoxylin and then fixed on slides. CDC7 expression was analyzed using ImageJ software.

4.11. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (version 10.0). Each experiment was repeated at least thrice. Student's t-test was applied to compare differences between two groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons among the different groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.K. and Ya.L.; methodology, X.Y.; software, J.Q. and K.Y.; validation, X.K., Ya.L. and X.Y.; formal analysis, Z.L., Y.W. and W.L.; investigation, Yu.L., Yi.L. and Y.Z.; resources, C.B. and A.Z.; data curation, X.K.; writing—original draft preparation, X.K.; writing—review and editing, X.K. and A.Z.; visualization, X.K., Ya.L. and X.Y.; supervision, C.B. and A.Z.; project administration, C.B. and A.Z.; funding acquisition, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

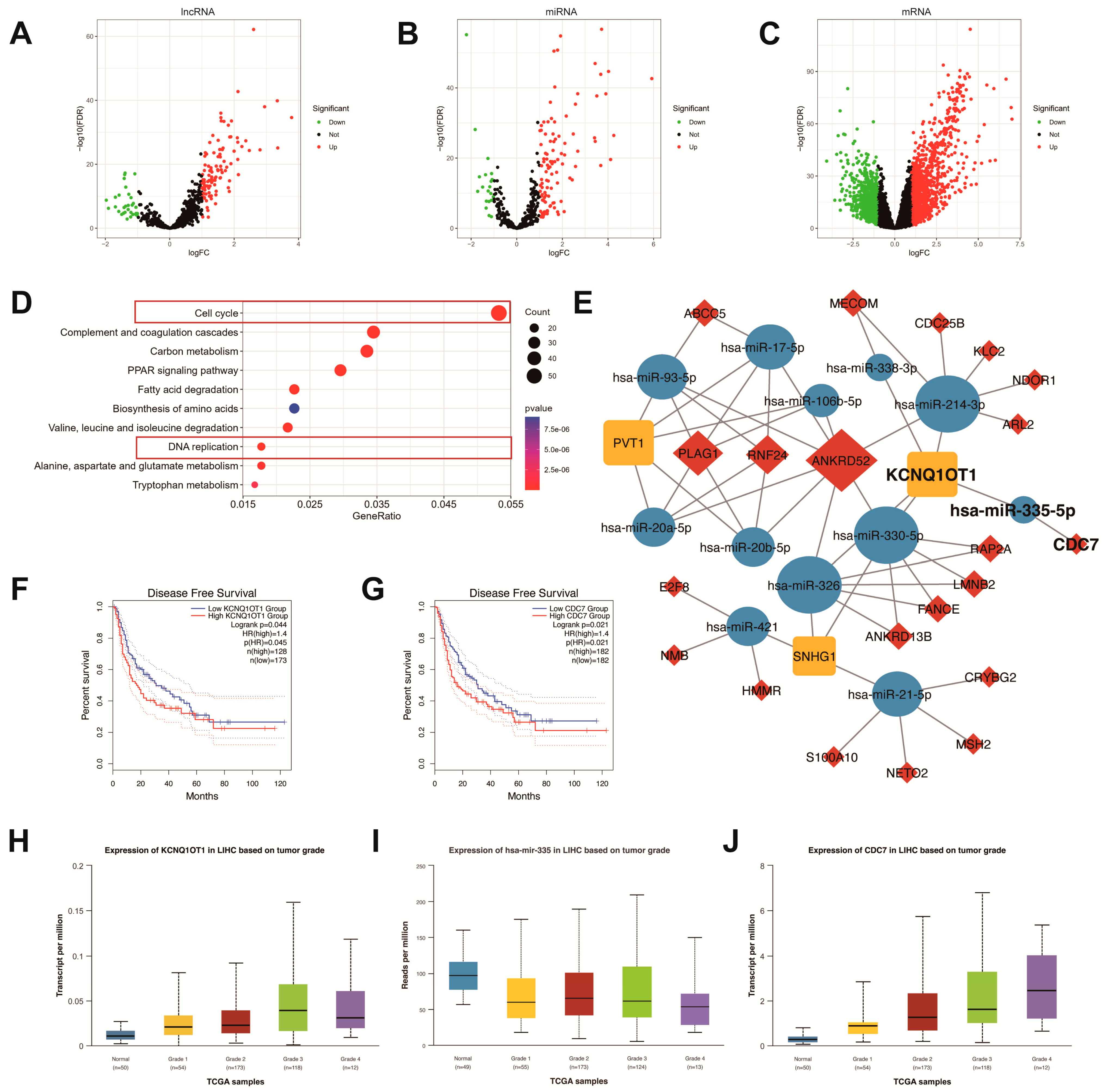

Figure 1.

Construction of DE lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network for HCC. Volcano plots of DE lncRNAs (A), miRNAs (B), and mRNAs (C) in HCC and normal tissues from the TCGA database. Red dots: upregulated (log2FC > 0.5, FDR < 0.05); green dots: downregulated (log2FC < -0.5, FDR < 0.05). FC, fold change. FDR, false discovery rate. (D) Top 10 KEGG enrichment terms for DE mRNAs. (E) Visualization of the ceRNA network for DE lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA using the Cytoscape. LncRNA: rectangles; miRNA: ellipses; mRNA: diamonds. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for KCNQ1OT1 (F) and CDC7 (G) expression using GEPIA 2 (p < 0.05). Analyses of KCNQ1OT1 (H), miR-335 (I), and CDC7 (J) expression in different tumor grades using UALCAN. Grade 1: well-differentiated; Grade 2: moderately differentiated; Grade 3: poorly differentiated; Grade 4: undifferentiated.

Figure 1.

Construction of DE lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network for HCC. Volcano plots of DE lncRNAs (A), miRNAs (B), and mRNAs (C) in HCC and normal tissues from the TCGA database. Red dots: upregulated (log2FC > 0.5, FDR < 0.05); green dots: downregulated (log2FC < -0.5, FDR < 0.05). FC, fold change. FDR, false discovery rate. (D) Top 10 KEGG enrichment terms for DE mRNAs. (E) Visualization of the ceRNA network for DE lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA using the Cytoscape. LncRNA: rectangles; miRNA: ellipses; mRNA: diamonds. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for KCNQ1OT1 (F) and CDC7 (G) expression using GEPIA 2 (p < 0.05). Analyses of KCNQ1OT1 (H), miR-335 (I), and CDC7 (J) expression in different tumor grades using UALCAN. Grade 1: well-differentiated; Grade 2: moderately differentiated; Grade 3: poorly differentiated; Grade 4: undifferentiated.

Figure 1.

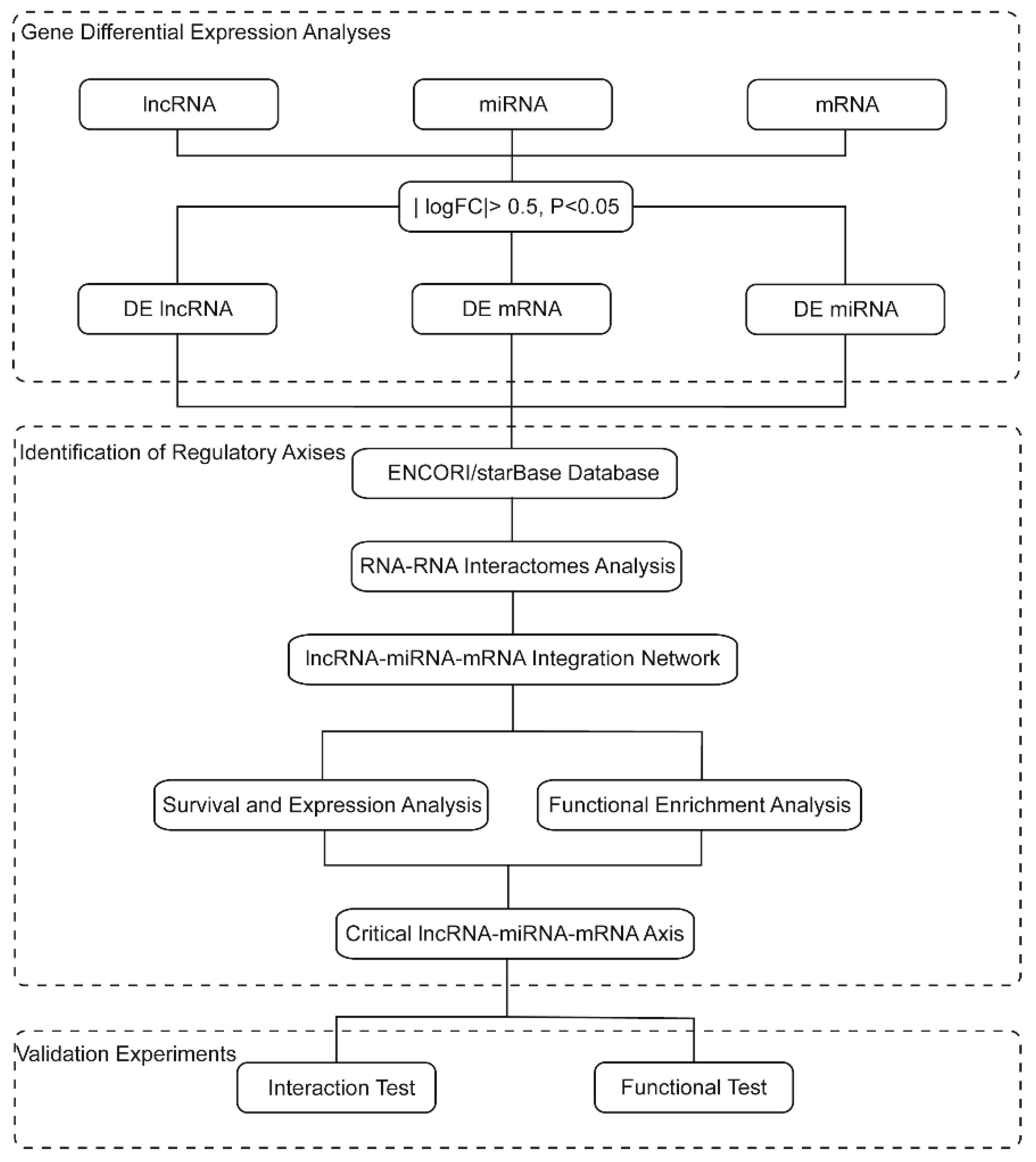

Roadmap of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory axis construction and validation.

Figure 1.

Roadmap of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory axis construction and validation.

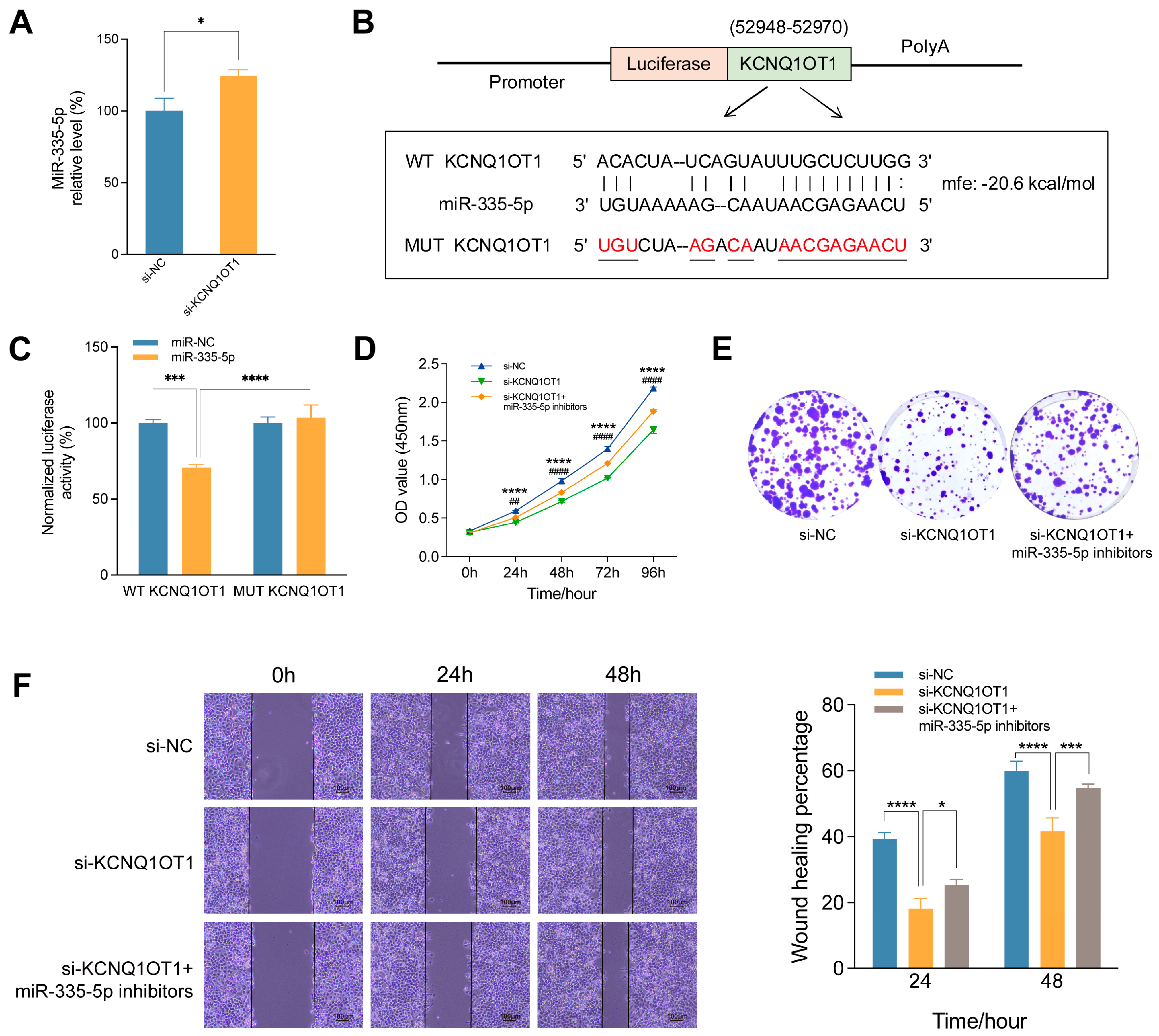

Figure 3.

KCNQ1OT1 promotes proliferation and migration of HCC cells by negatively regulating miR-335-5p. (A) The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells after KCNQ1OT1 knockdown by RT-qPCR. (B) The binding sites of KCNQ1OT1 to miR-335-5p predicted by RNAhybrid. mfe: minimum free energy. (C) Luciferase reporter assay was used to verify the targeted binding effect between miR-335-5p and WT-KCNQ1OT1 or MUT-KCNQ1OT1 in SMMC-7721 cells. (D) CCK-8 assay of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1, or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. *p: si-KCNQ1OT1 vs. si-NC; #p: si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors vs. si-KCNQ1OT1. Colony formation assay (E) and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1, or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. *p<0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ## p < 0.01, #### p <0.0001.

Figure 3.

KCNQ1OT1 promotes proliferation and migration of HCC cells by negatively regulating miR-335-5p. (A) The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells after KCNQ1OT1 knockdown by RT-qPCR. (B) The binding sites of KCNQ1OT1 to miR-335-5p predicted by RNAhybrid. mfe: minimum free energy. (C) Luciferase reporter assay was used to verify the targeted binding effect between miR-335-5p and WT-KCNQ1OT1 or MUT-KCNQ1OT1 in SMMC-7721 cells. (D) CCK-8 assay of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1, or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. *p: si-KCNQ1OT1 vs. si-NC; #p: si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors vs. si-KCNQ1OT1. Colony formation assay (E) and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1, or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. *p<0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ## p < 0.01, #### p <0.0001.

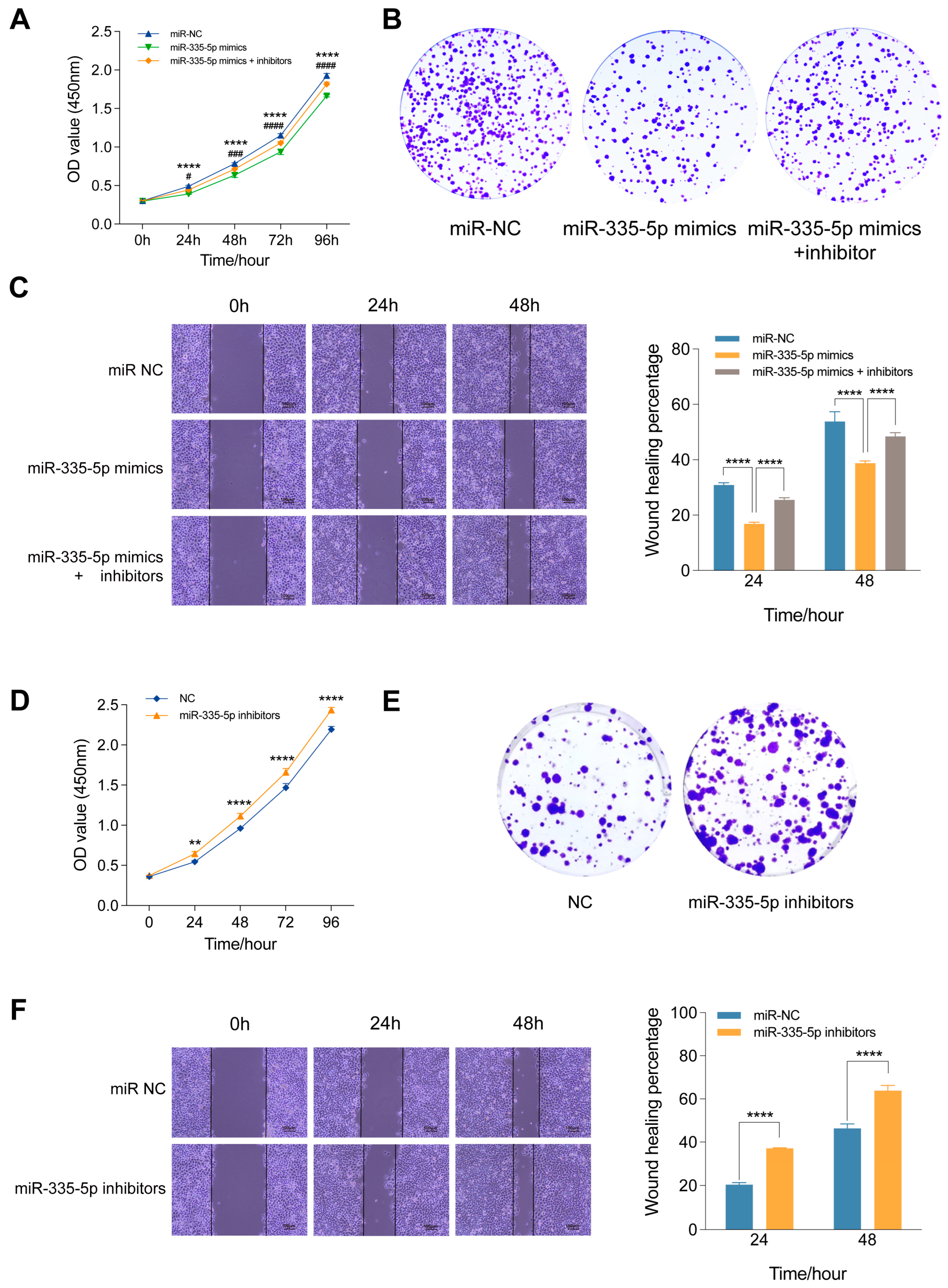

Figure 4.

MiR-335-5p inhibits proliferation and migration of HCC cells. CCK-8 assay (A), cell colony formation assay (B), and wound healing assay (C) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-NC, miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors. *p: miR-335-5p mimics vs. miR-NC; #p: miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors vs. miR-335-5p mimics. CCK-8 assay (D), cell colony formation assay (E), and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-NC and miR-335-5p inhibitors. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001, ####p <0.0001.

Figure 4.

MiR-335-5p inhibits proliferation and migration of HCC cells. CCK-8 assay (A), cell colony formation assay (B), and wound healing assay (C) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-NC, miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors. *p: miR-335-5p mimics vs. miR-NC; #p: miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors vs. miR-335-5p mimics. CCK-8 assay (D), cell colony formation assay (E), and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-NC and miR-335-5p inhibitors. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001, ####p <0.0001.

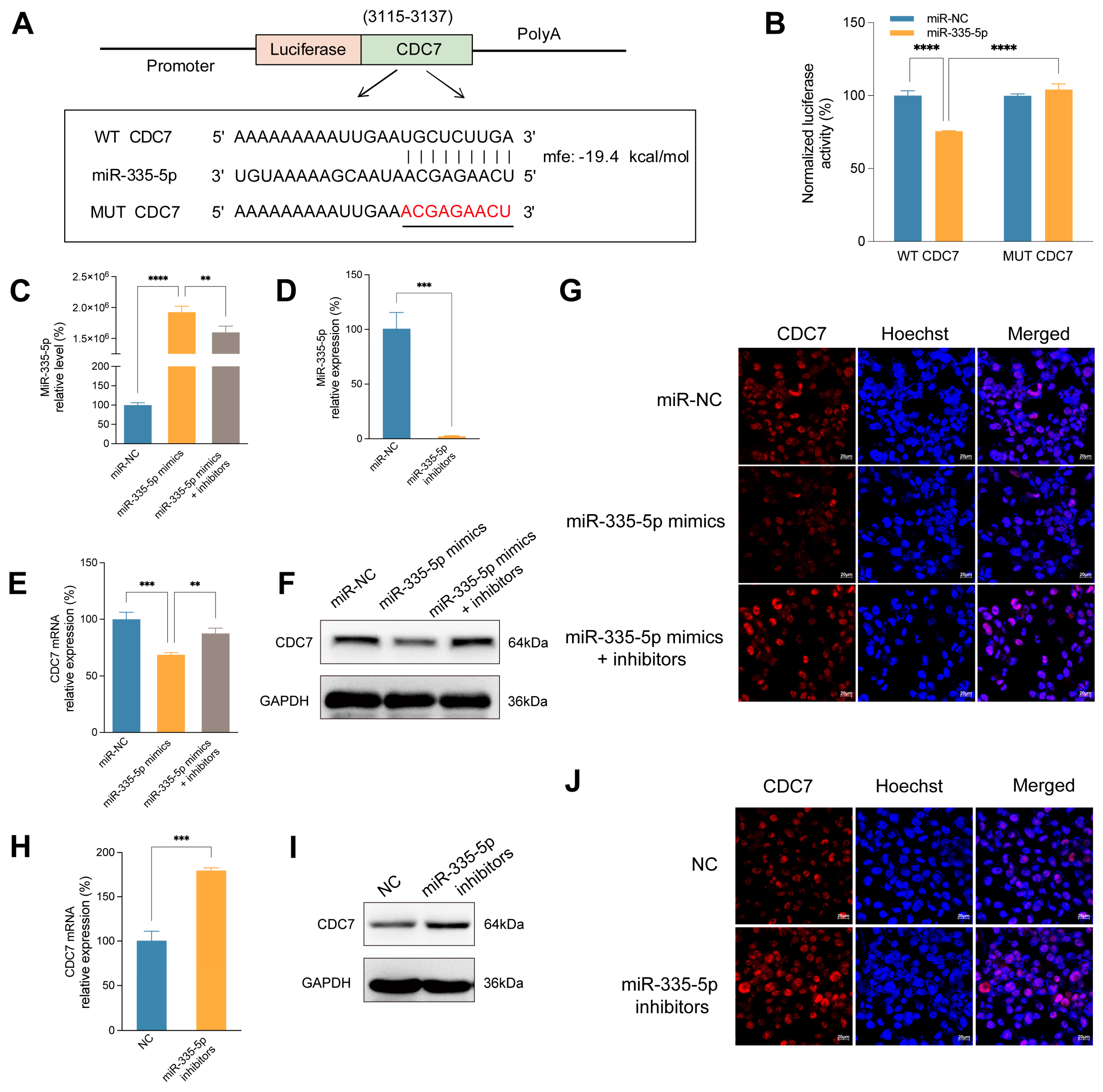

Figure 5.

The expression of CDC7 was regulated by miR-335-5p negatively. (A) The binding sites of miR-335-5p to CDC7 predicted by RNAhybrid. (B) Luciferase reporter assay was used to verify the targeted binding effect between miR-335-5p and WT-CDC7 or MUT-CDC7 in SMMC-7721 cells. (C)The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors using RT-qPCR analysis. (D) The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p inhibitors using RT-qPCR analysis. The RT-qPCR (E), WB (F), and immunofluorescence assay (G) of CDC7 level in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors. The RT-qPCR (H), WB (I), and immunofluorescence assay (J) of CDC7 level in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p inhibitors. **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

The expression of CDC7 was regulated by miR-335-5p negatively. (A) The binding sites of miR-335-5p to CDC7 predicted by RNAhybrid. (B) Luciferase reporter assay was used to verify the targeted binding effect between miR-335-5p and WT-CDC7 or MUT-CDC7 in SMMC-7721 cells. (C)The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors using RT-qPCR analysis. (D) The expression of miR-335-5p in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p inhibitors using RT-qPCR analysis. The RT-qPCR (E), WB (F), and immunofluorescence assay (G) of CDC7 level in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p mimics or co-transfected with miR-335-5p mimics and inhibitors. The RT-qPCR (H), WB (I), and immunofluorescence assay (J) of CDC7 level in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with miR-335-5p inhibitors. **p<0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

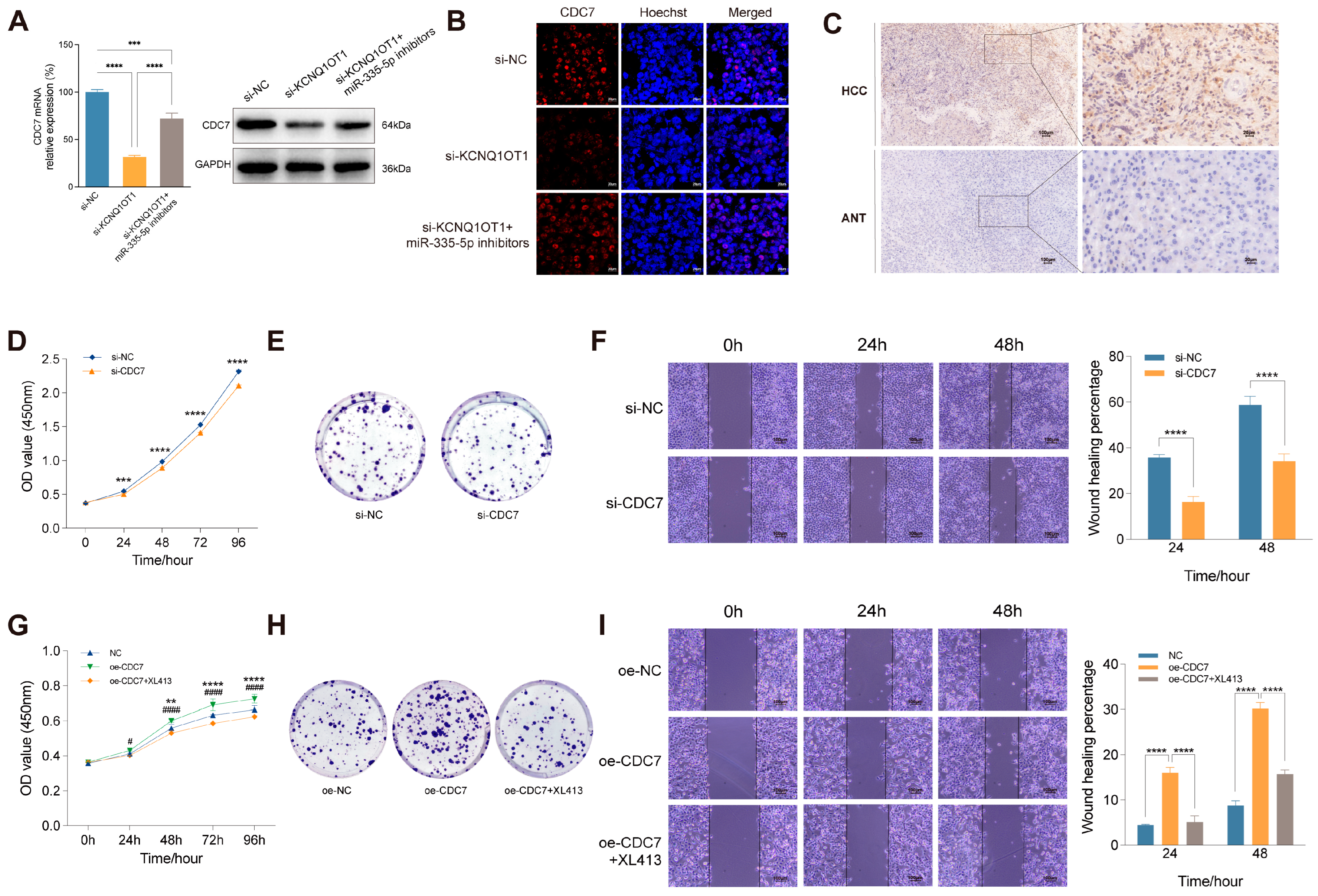

Figure 6.

KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis mediates proliferation and migration of HCC cells. RT-qPCR, WB (A), and immunofluorescence assay (B) of CDC7 expression in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1 or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. (C) Immunohistochemistry of CDC7 expression in HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues (ANT). CCK-8 assay (D), cell colony formation assay (E), and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells after CDC7 knockdown. CCK-8 assay (G), cell colony formation assay (H), and wound healing assay (I) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with oe-NC, oe-CDC7, or co-transfected with oe-CDC7 and XL413. *p: oe-CDC7 vs. oe-NC; #p: co-transfection with oe-CDC7 and XL413 vs. oe-CDC7. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, ####p <0.0001.

Figure 6.

KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis mediates proliferation and migration of HCC cells. RT-qPCR, WB (A), and immunofluorescence assay (B) of CDC7 expression in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with si-NC, si-KCNQ1OT1 or co-transfected with si-KCNQ1OT1 and miR-335-5p inhibitors. (C) Immunohistochemistry of CDC7 expression in HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues (ANT). CCK-8 assay (D), cell colony formation assay (E), and wound healing assay (F) of SMMC-7721 cells after CDC7 knockdown. CCK-8 assay (G), cell colony formation assay (H), and wound healing assay (I) of SMMC-7721 cells transfected with oe-NC, oe-CDC7, or co-transfected with oe-CDC7 and XL413. *p: oe-CDC7 vs. oe-NC; #p: co-transfection with oe-CDC7 and XL413 vs. oe-CDC7. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, ####p <0.0001.

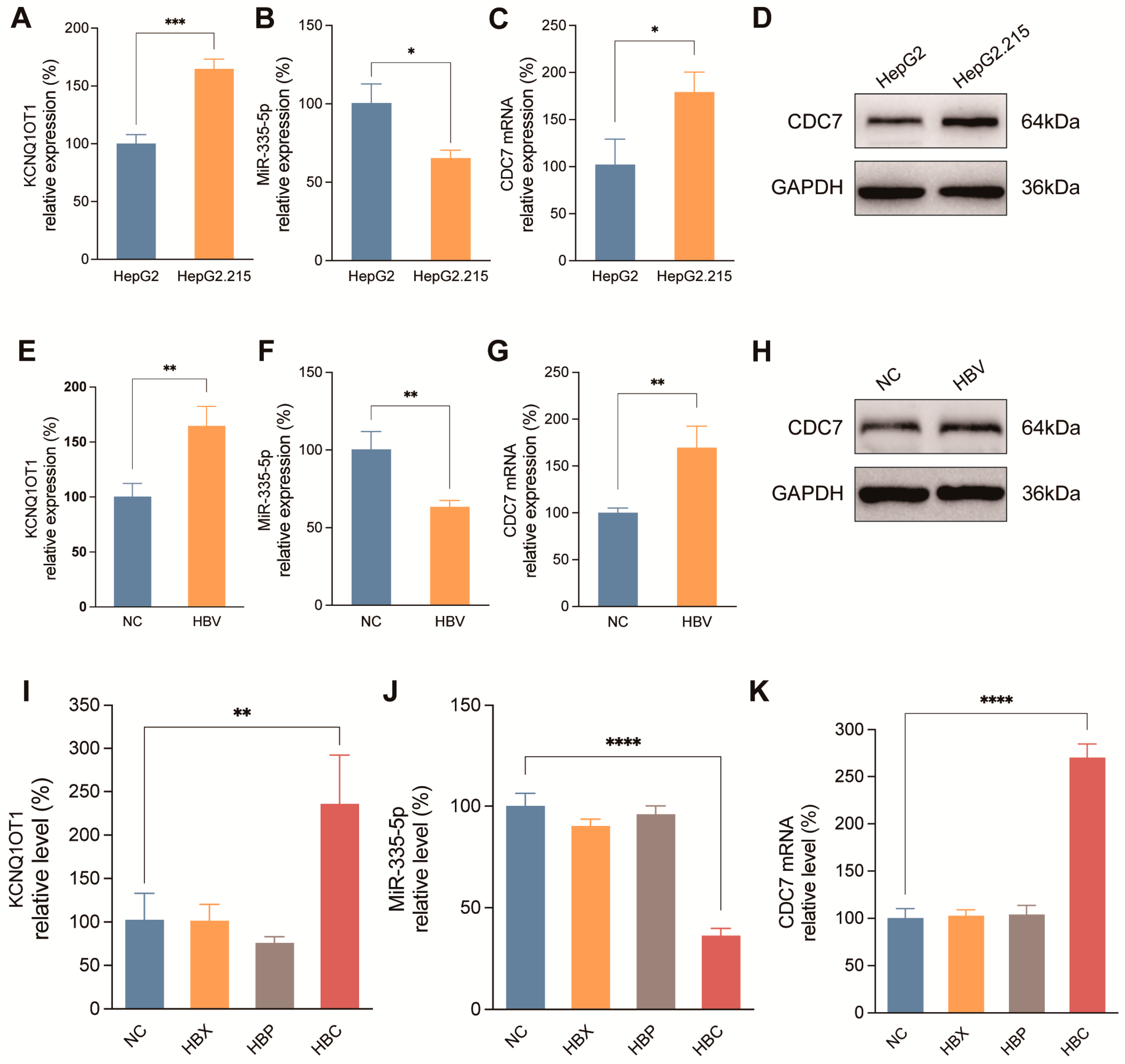

Figure 7.

Regulatory effect of HBV and its encoded proteins on the KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis. RNA levels of KCNQ1OT1 (A), miR-335-5p (B) and CDC7 (C) in HepG2 and HepG2.215 cells. (D) WB of CDC7 protein expression in HepG2 and HepG2.215 cells. RNA levels of KCNQ1OT1 (E), miR-335-5p (F) and CDC7 (G) in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with a 1.3-fold HBV whole genome plasmid. (H) WB of CDC7 protein expression in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with a 1.3-fold HBV whole genome plasmid. Expression of KCNQ1OT1 (I), miR-335-5p (J) and CDC7 (K) in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with NC, HBx, HBp, and HBc recombinant plasmids. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

Regulatory effect of HBV and its encoded proteins on the KCNQ1OT1/miR-335-5p/CDC7 axis. RNA levels of KCNQ1OT1 (A), miR-335-5p (B) and CDC7 (C) in HepG2 and HepG2.215 cells. (D) WB of CDC7 protein expression in HepG2 and HepG2.215 cells. RNA levels of KCNQ1OT1 (E), miR-335-5p (F) and CDC7 (G) in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with a 1.3-fold HBV whole genome plasmid. (H) WB of CDC7 protein expression in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with a 1.3-fold HBV whole genome plasmid. Expression of KCNQ1OT1 (I), miR-335-5p (J) and CDC7 (K) in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with NC, HBx, HBp, and HBc recombinant plasmids. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.