3. Methodology

To perform trend prediction on a FTS, a suitable model for the series must be chosen. This determines the nature of the functions used to calculate any market metrics and conduct historic backtesting. The following section presents an overall analysis of the BTC-USD and ETH-USD markets to determine a `distribution of best fit’ before outlining the code implementing the equations derived in

Section 2.3, the backtesing strategy, and ML short term prediction.

3.1. Cryptocurrency - An Efficient or Fractal Market

Before any trend prediction approach can be adopted, there must be a determination of whether cryptocurrencies display efficient or fractal behaviour. To achieve this, 7 years of opening prices (00:00:00 GMT) on both the BTC-USD and ETH-USD markets were collected. For the purpose of this report, only BTC-USD will be described in detail, with the accompanying results for ETH-USD presented to readers.

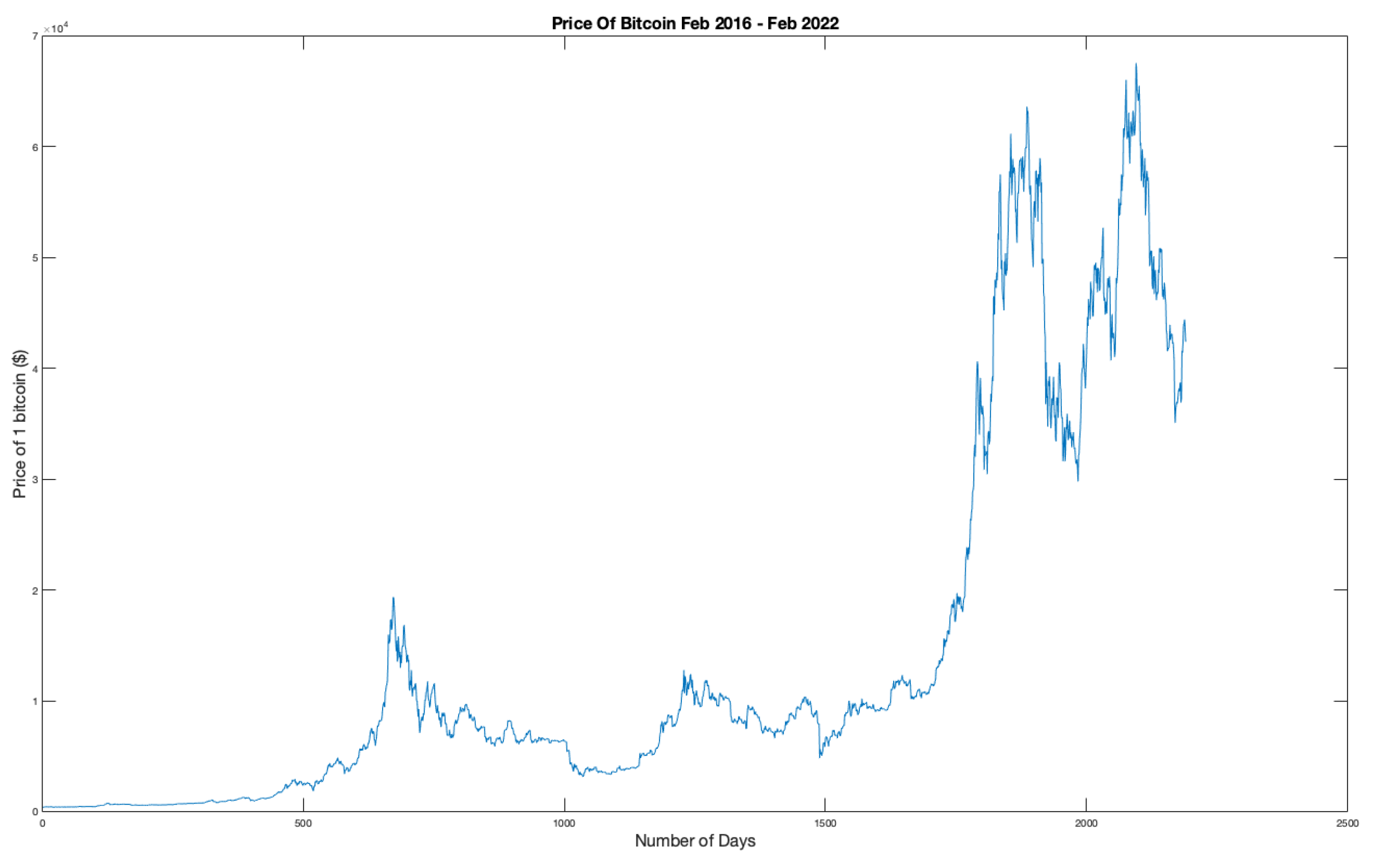

Figure 1 shows the price of Bitcoin from February 12th 2016 to February 12th 2022. The data was obtained from

https://www.CryptoDataDownload.com using the Gemini database for Coinbase hourly prices. The extraction of this data was achieved using a Matlab function which will be introduced in

Section 3.3.2. All work prepared for this paper was conducted in Matlab and Excel.

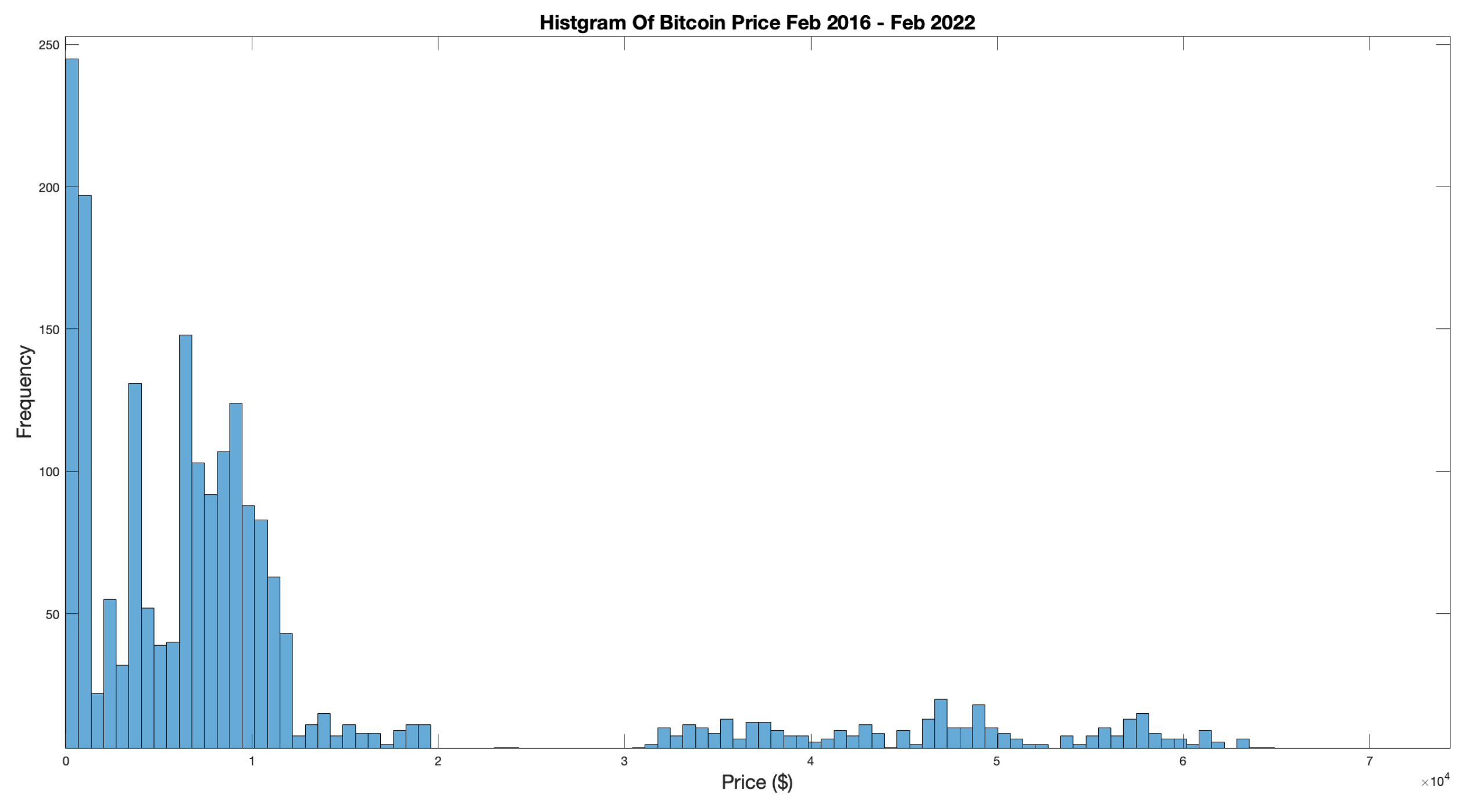

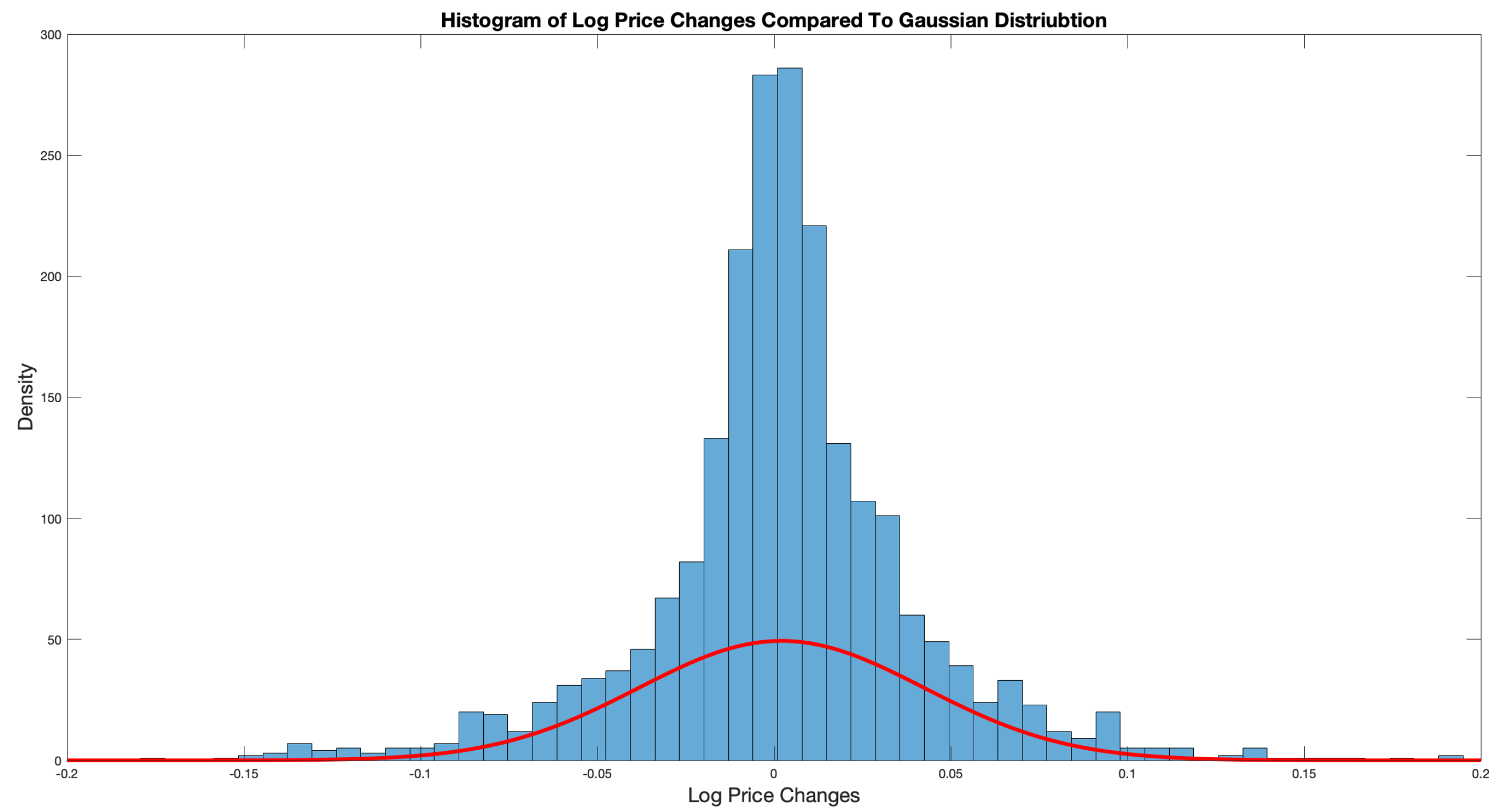

Figure 2 displays the Probability Density Function (PDF) of BTC-USD prices. The distribution clearly does not conform to the traditional `Bell Curve’ synonymous with a Normal distribution. The standard deviation was calculated to be

with a Kurtosis of

indicating a Leptokurtic curve with a narrow peak. The Skew is

indicating a longer tail to the right.

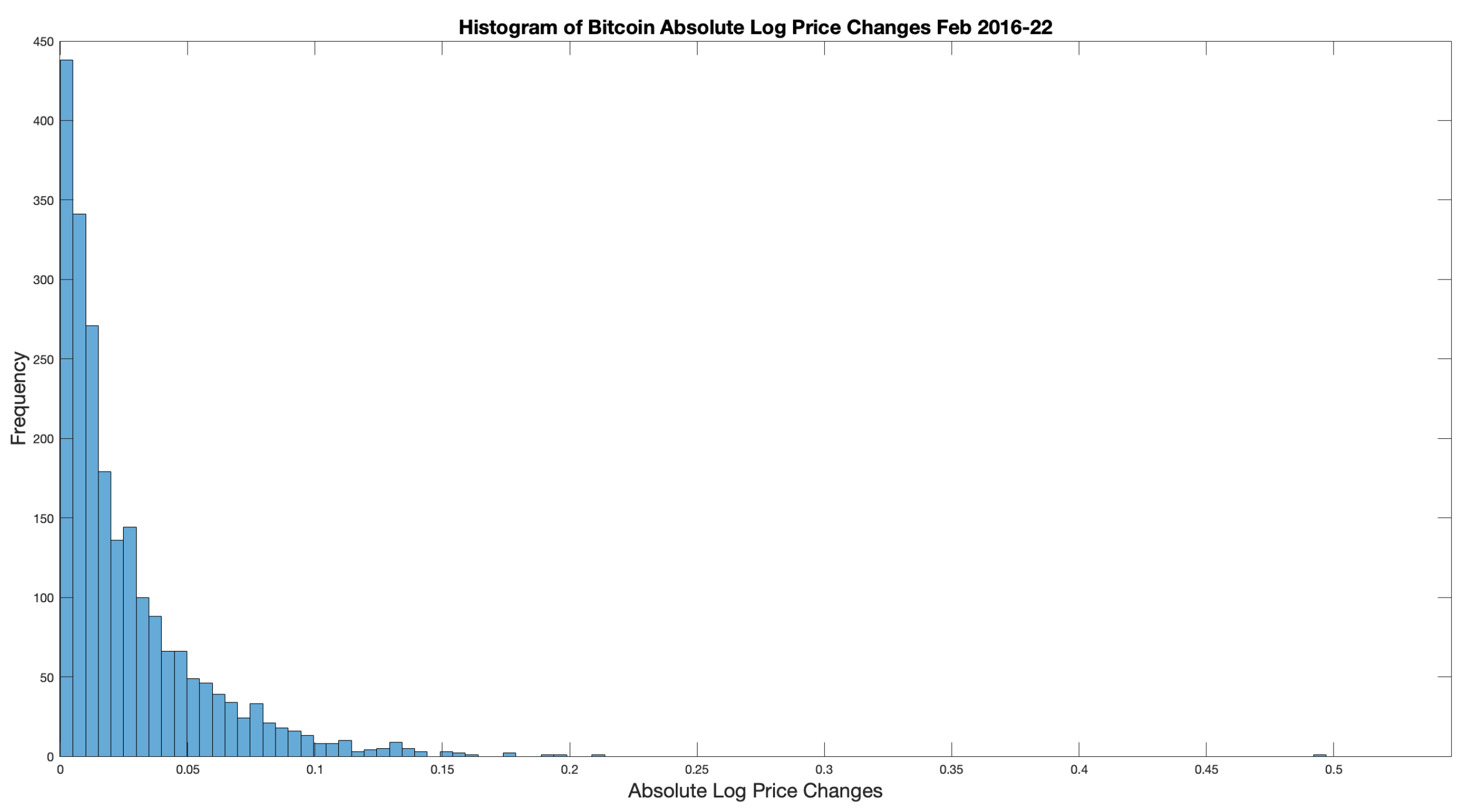

However, this work is concerned with the distribution of price changes between daily opening prices. In this respect,

Figure 3 shows the PDF of the absolute log of BTC-USD price changes.

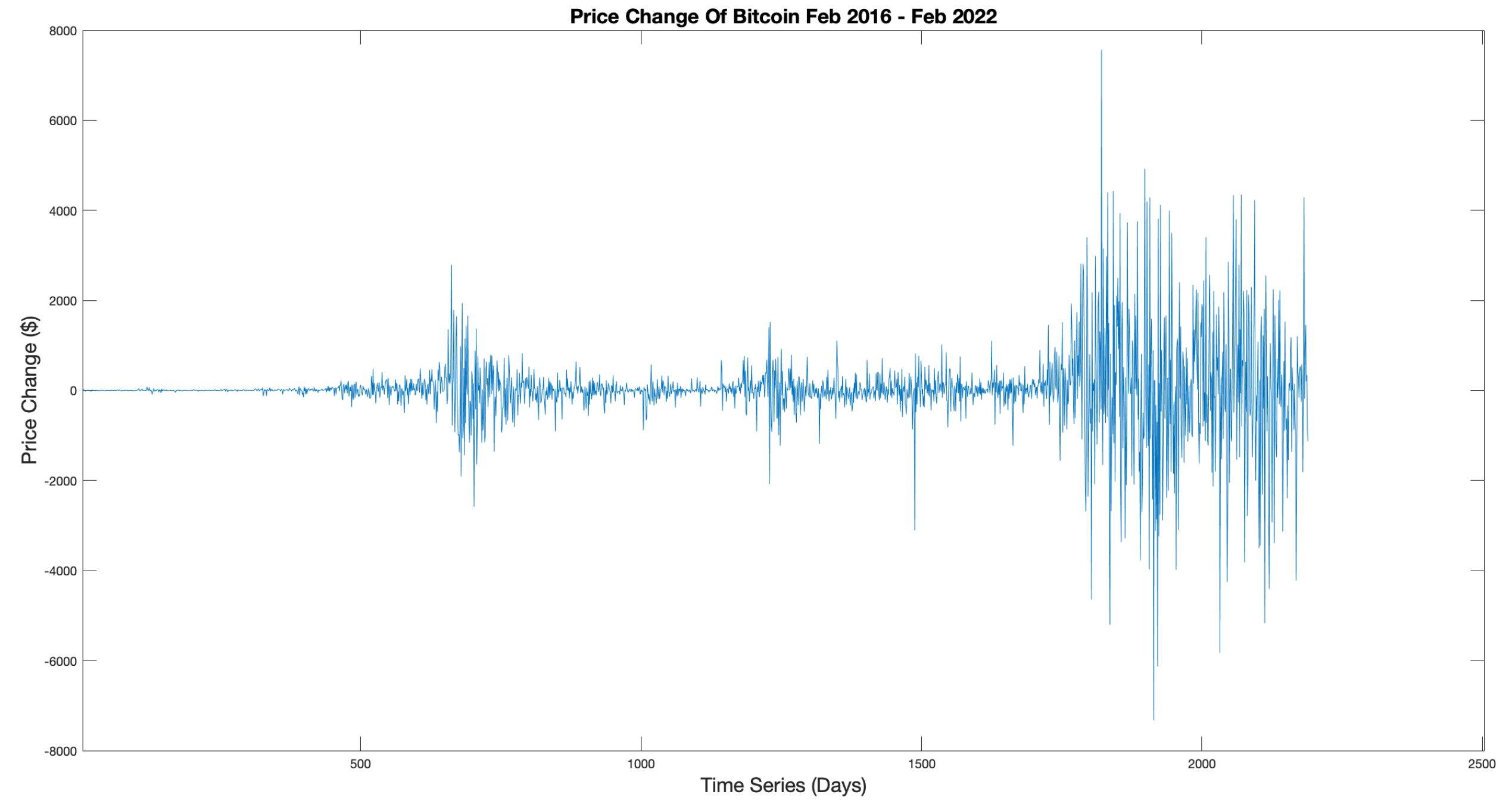

Figure 4 displays the actual price changes. The forward difference is used to purely display price changes and logs taken to remove exponential elements within the signal.

An efficient market is considered to follow a RWM where each event is random and independent. Under this consideration, price changes should follow a Gaussian distribution. However, it is clear from

Figure 3 that the peaked nature of the PDF is far more indicative of a Lévy distribution. This provides some initial evidence that BTC-USD is not an efficient market.

Figure 5 depicts the log price PDF with a standard Gaussian bell curve overlaid to enforce the difference.

As outlined in

Section 2, the limitations of the EMH has led to the introduction of new analytic methods. The Hurst exponent (

H), resulting from Re-Scaled Range Analysis (RSRA), is a measure of a signal’s persistence or anti-persistence, i.e the likelihood that the next change will be in line or opposed to the current trend direction.

would signify an independently distributed signal, indicating a classical Brownian diffusion model, whilst

indicates a persistent system and

indicates an anti-persistent system. Using Equation (

1), the Hurst Exponent was calculated, yielding a value of

, confirming that the BTC-USD exchange displays anti-persistence characteristics and does not conform to conventional Brownian motion, i.e classical diffusion.

Another measure relevant to the BTC-USD time series is the Fractal Dimension (

). A measure of the self-similarity of a stochastic self-affine field, it can provide insight into the power spectrum range. With

being the maximum value, any value below this (

) will provide a quantitative representation of the fields deviation from normality. Using Equation (

3) for the case of BTC-USD,

. This is further evidence that this exchange is not an efficient market.

Finally the Lévy index gives a representation of the signals variability, with

recovering a Gaussian distribution of price changes and

signifying a Cauchy distribution. As

decreases from 2, the distribution becomes increasingly peaked. Using Equation (

3) the Levy index was calculated to be

, clearly indicating that the BTC-USD should be modelled as a Lévy distribution where the stochastic field is fractal in nature and susceptible to more frequent rare but extreme events called `Lévy flights’.

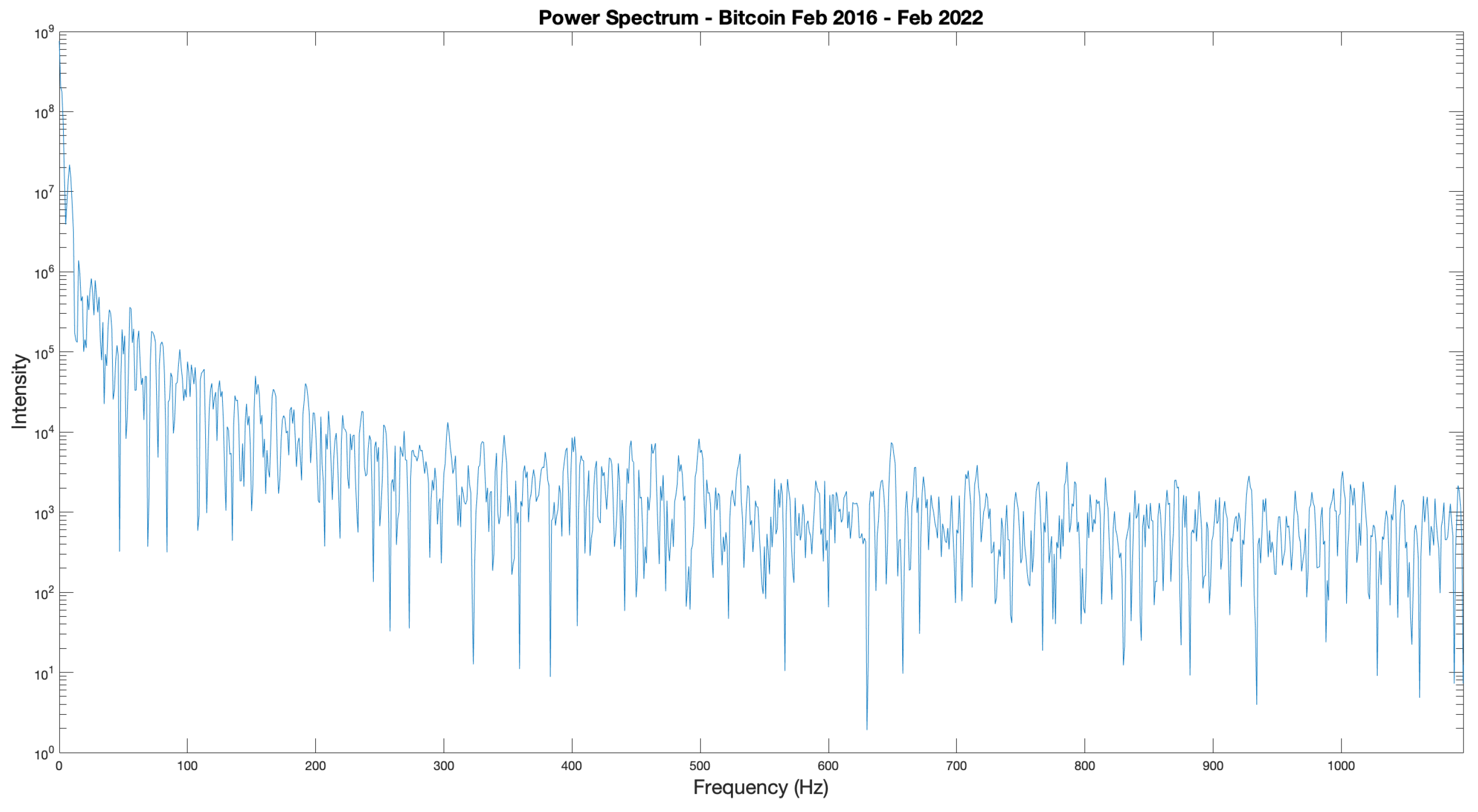

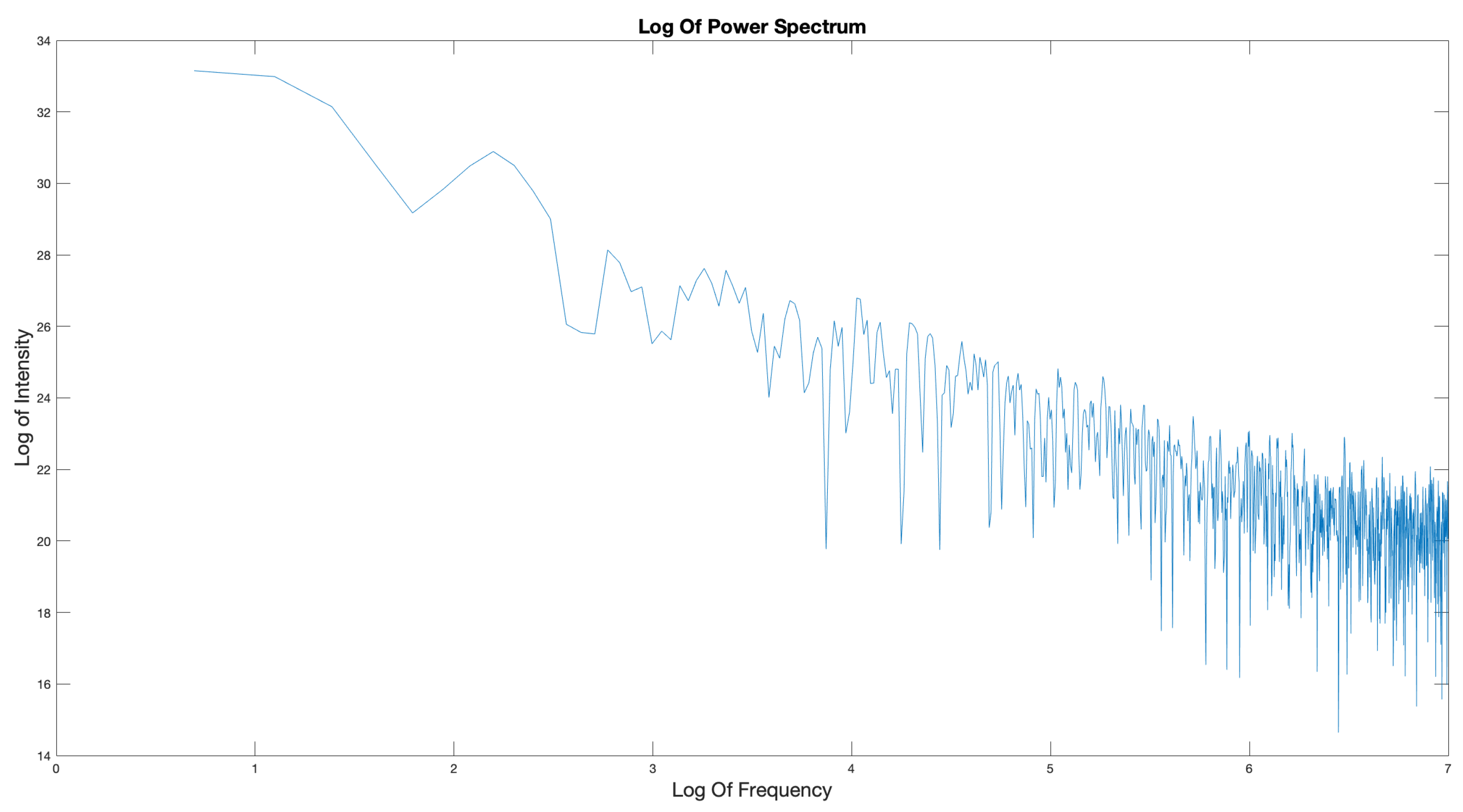

The power spectrum of a signal can be used to characterise any correlation present within the signal [

58]. This correlation is an indicator of any long or short term memory, another characteristic of fractal self-affine fields. In the spectrum, increased intensity at lower frequencies indicate a long term market memory effect, with high intensity at higher frequencies indicating short term memory. The function to determine the correlation between two time prices for a financial time series

is given by

where ↔ represents the transformation to Fourier space and the spectrum

is given by

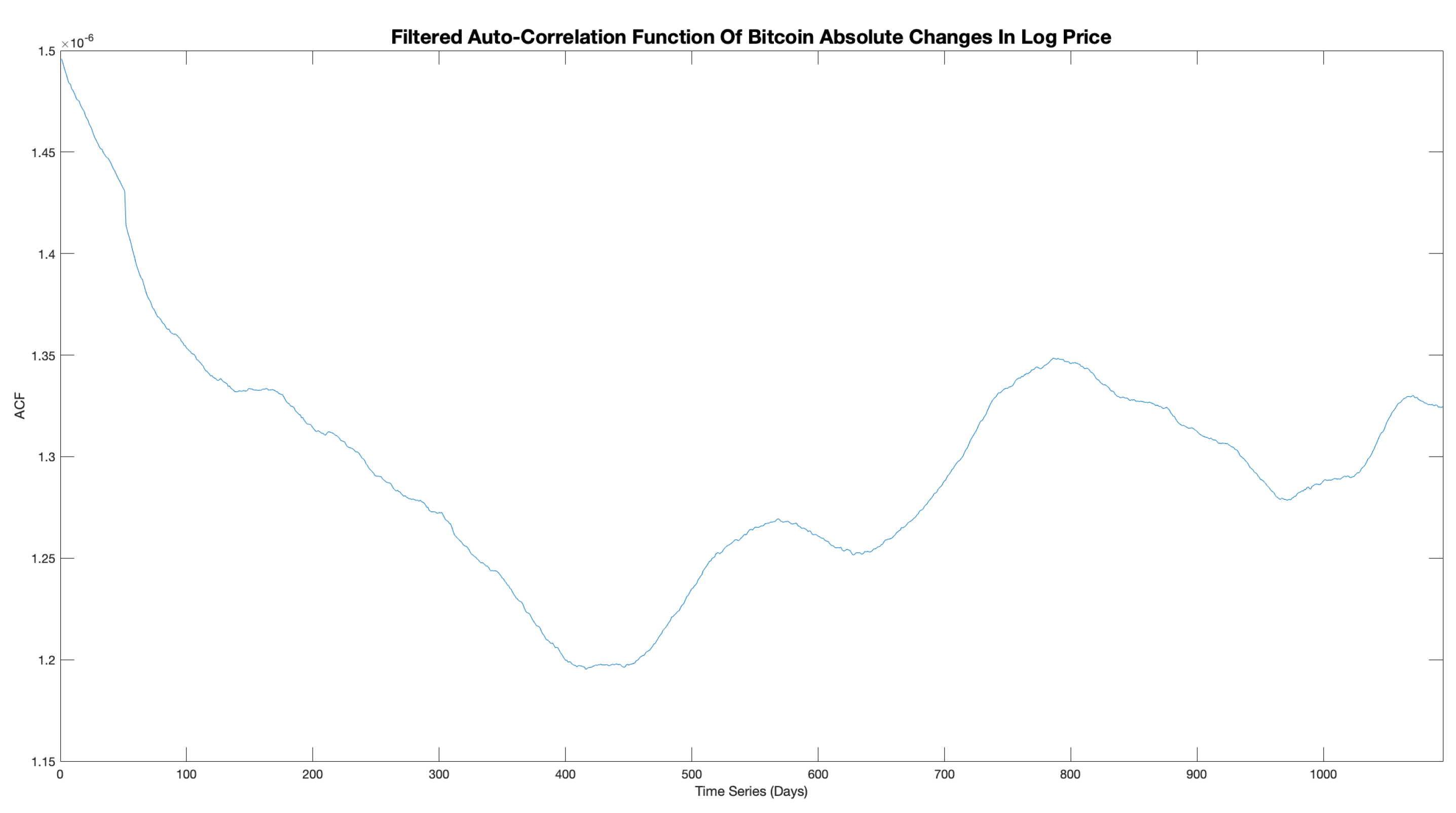

The Auto-Correlation Function (ACF) is produced by taking the IFT of the power spectrum. This provides a measure of how present price data is correlated with future prices. According to the EMH, the time series should be uncorrelated and therefore exhibit no market memory. This would visually be rendered as a flat power spectrum and a peaked ACF around the origin.

The resulting power spectrum of the absolute log price changes is displayed in

Figure 6, and shows that there is increased intensity at the lower frequencies, indicating long term market memory and correlation within the data set. The corresponding filtered ACF is displayed in

Figure 7 and shows that there is long term market memory introduced at

days, with peaks of increasing amplitude at

and

days. Both of these results differ from that expected under the EMH. Therefore, evidence that the BTC-USD exchange does not conform to an efficient market view.

Finally a quick comparison between Daily and Hourly price changes provides further evidence of self-affinity. In a fractal signal, the PDFs would be invariant of scale and therefore the same.

Table 1 shows a compilation of all of the results for Ethereum and Bitcoin indexes. The results are all very similar confirming that both the markets are fractal.

This body of analysis provides clear indication that the BTC-USD and ETH-USD exchanges are not efficient markets. The absolute log price changes are shown to not conform to a Gaussian distribution, with a peaked and skewed PDF observed showing that price changes are not independent. They display clear long term correlation and market memory effects as well as being subject to Lévy flights. Therefore, both cryptocurrency fields have a highly non-linear, fractal, self-affine nature and require a FMH approach.

3.2. Analysis

To determine if the LVR () and BVR () are useful metrics for recommending trading positions they must be tested on real life markets. Backtesting is a well established process, allowing traders to determine how effective a trading strategy is on historical data, thereby allowing them to assess its benefits or otherwise.

Using an evaluator function, the accuracy of the trading positions, represented by the zero crossings of the metric signal, can be quantified. Operating on the fact that when , indicating a buy position, the following price trend is predicted to be positive. The next position (sell) should, therefore, be at a higher price. This case would be seen as a valid result, however, if the sell position was indicated at a lower price, this would be considered a failure as it has resulted in a net loss. This concept can be used in reverse for when , indicating a short position and a predicted downward trend.

Applied to all trading positions in the backtesting output, a combined accuracy for the data set can be determined, quantifying how many recommended positions resulted in positive returns. The function for backtesting is presented in

Appendix A.4.

For this body of work, individual time series for each year of BTC-USD/ETH-USD daily opening price data were made from 2016 to 2022, as well as time series representing individual months of hourly data from Nov-Feb 2022. This allowed a wide range of data sets to be analysed on different time scales.

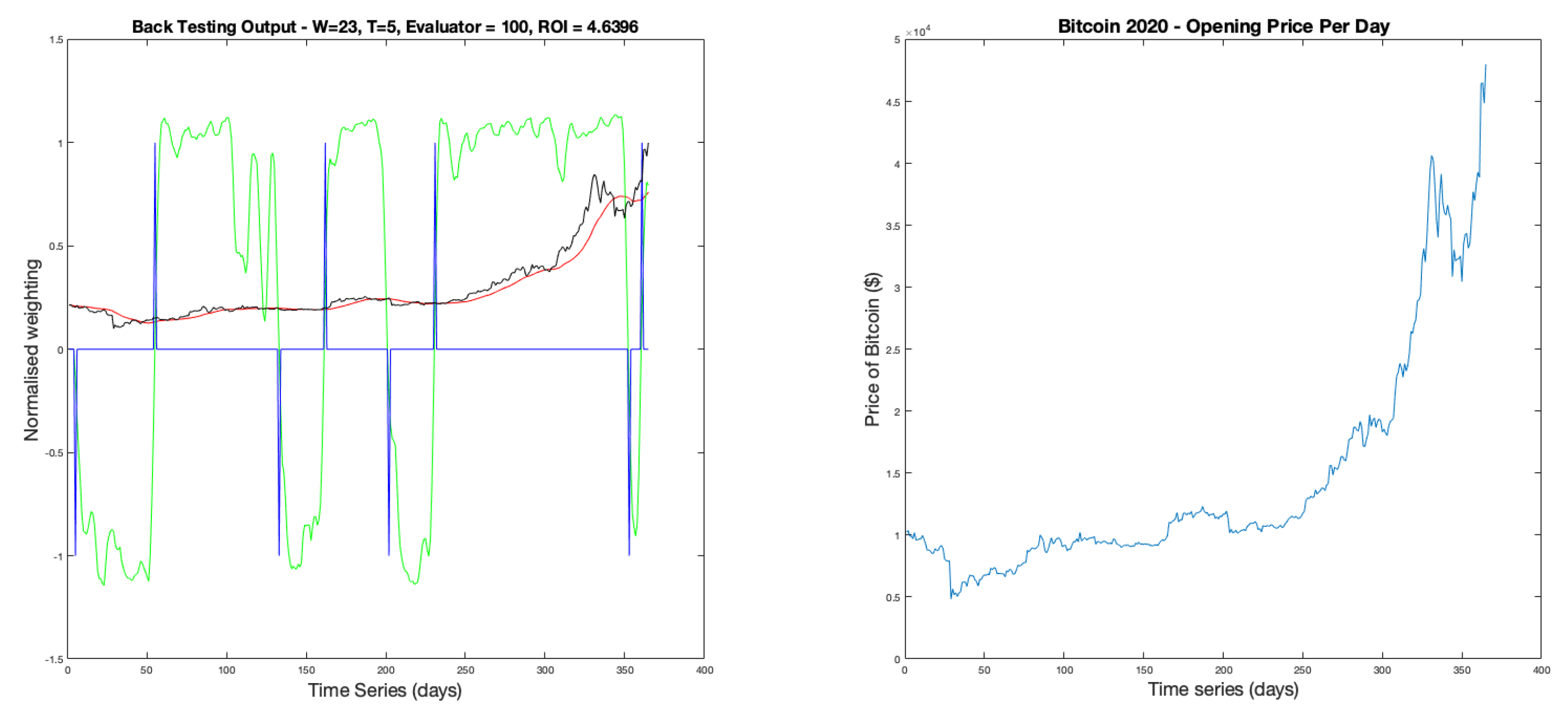

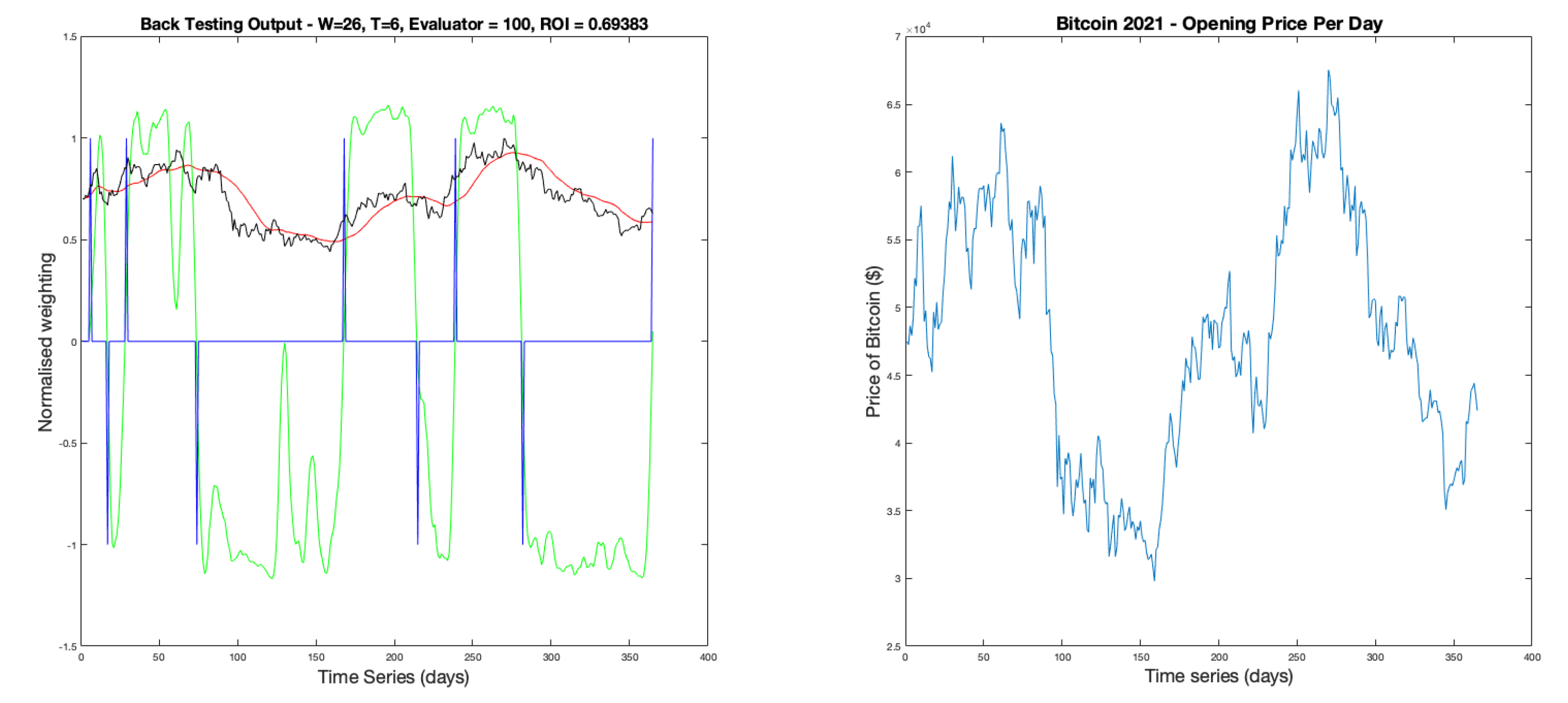

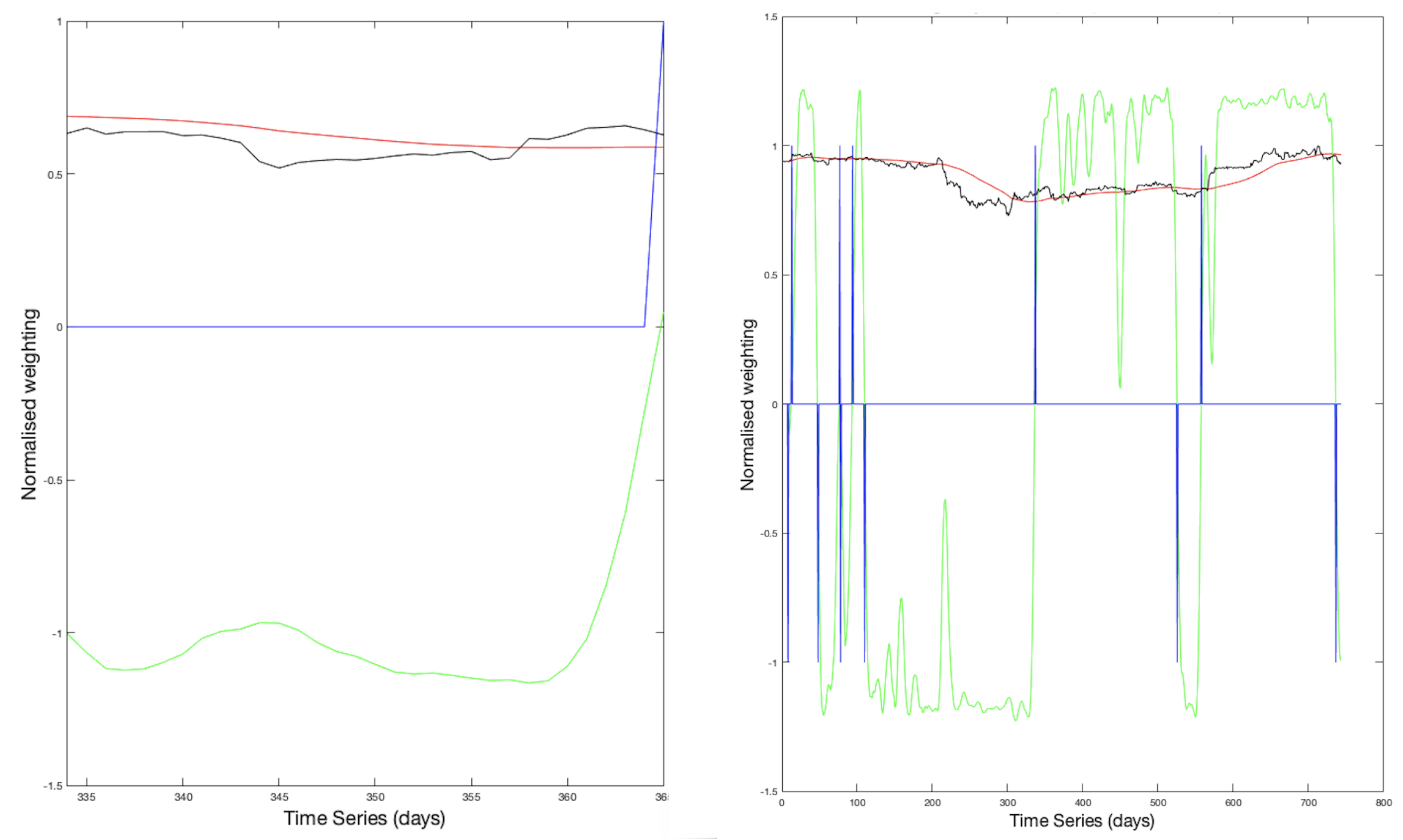

The backtesting function receives parameters

W, filtering window width, and

T, the financial index calculation window. It also normalises the raw price data so that it can be displayed on the same scale as the resulting metric signal. Finally, the function produces a split graphic displaying the metric signal

(LVR), the filtered/unfiltered price data and

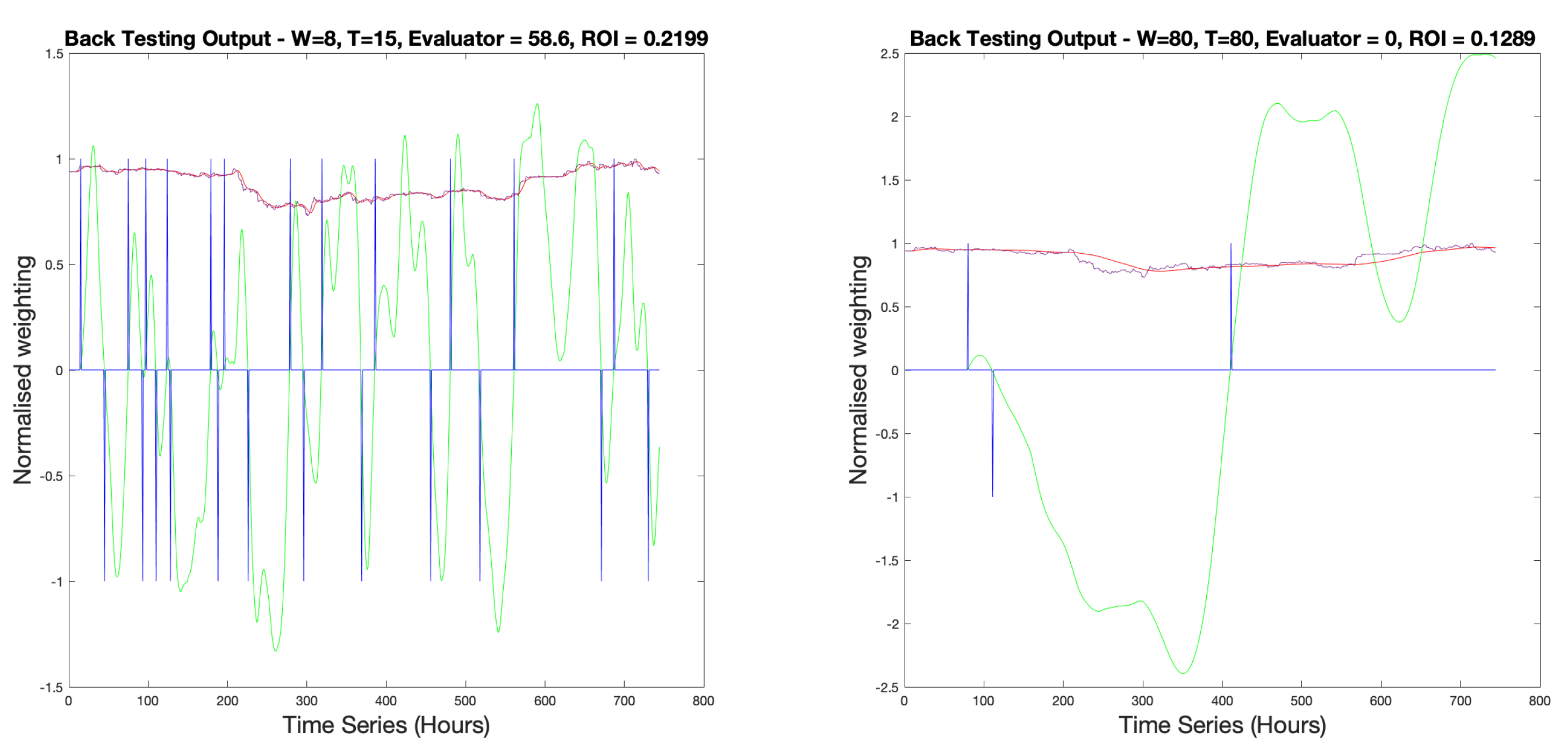

(left plot), and the non-normalised FTS (right plot). An example of which is displayed in

Figure 8.

This example uses parameters of and . It shows 8 trades in total resulting in positive returns with a total ROI of .

Another advantage of backtesting is the freedom to perform parameter analysis to find the optimum range that provides the greatest accuracy and returns. As eluded to in

Section 2.3.3, the trading delay caused by pre-filtering coupled with micro-trends can cause errors in the recommended trading positions. Therefore, logically, there will be a `sweet spot’ of parameters where the delay doesn’t heavily effect the system output and still adequately reduces the noise present in the signal.

Using the function

, presented in

Appendix A.5, backtesting was performed on an iterative basis, where each iteration increments the parameters

W and

T. The function produces two mesh representations of parameter combinations against evaluator results and returns, allowing comparison between parameters that achieve optimum accuracy and profit to determine if the two are correlated in any way. Due to possible micro-trends and over filtering,

position accuracy can result in a loss, as the evaluator operates using the filtered data set, not the real time series.

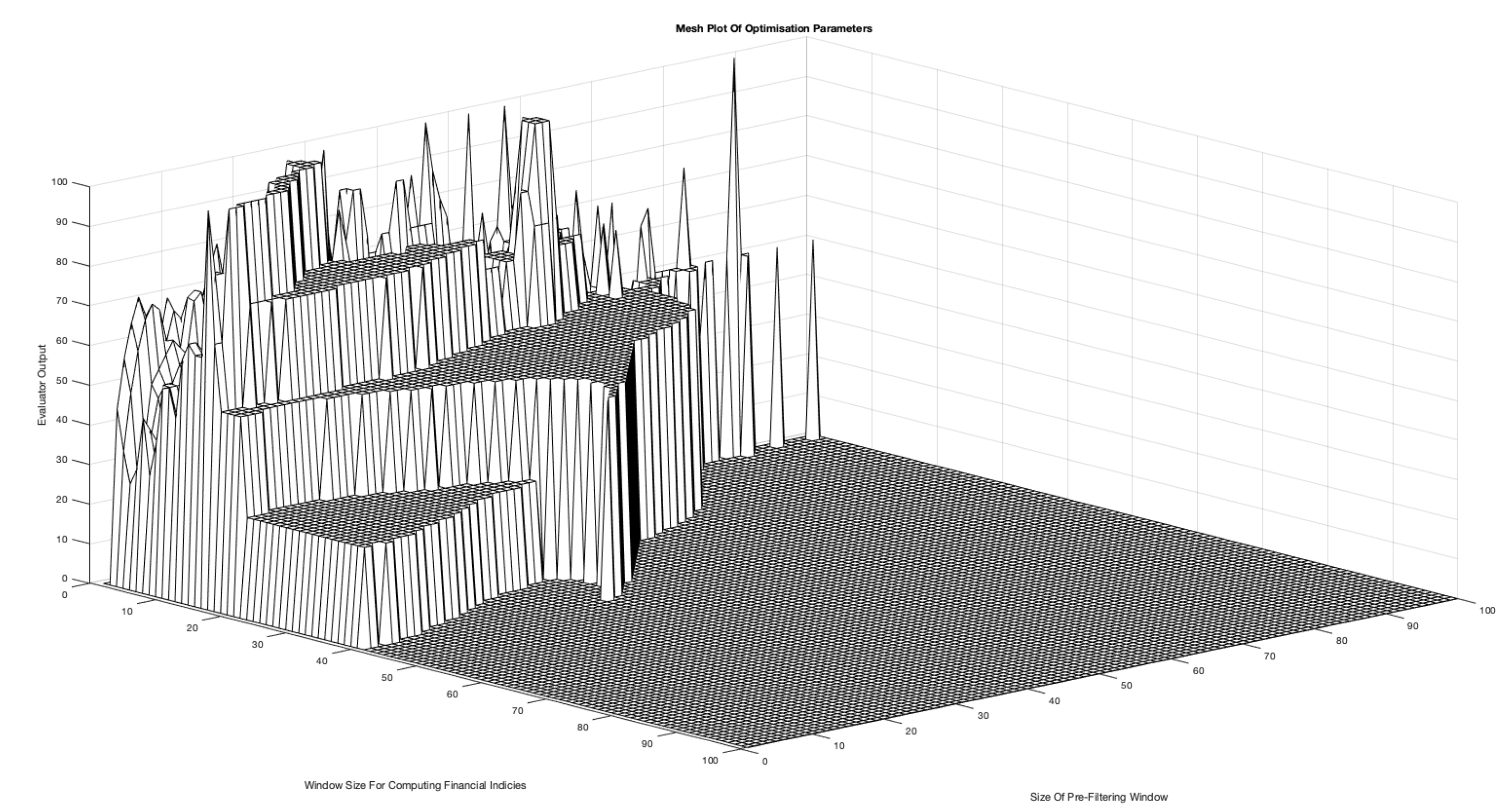

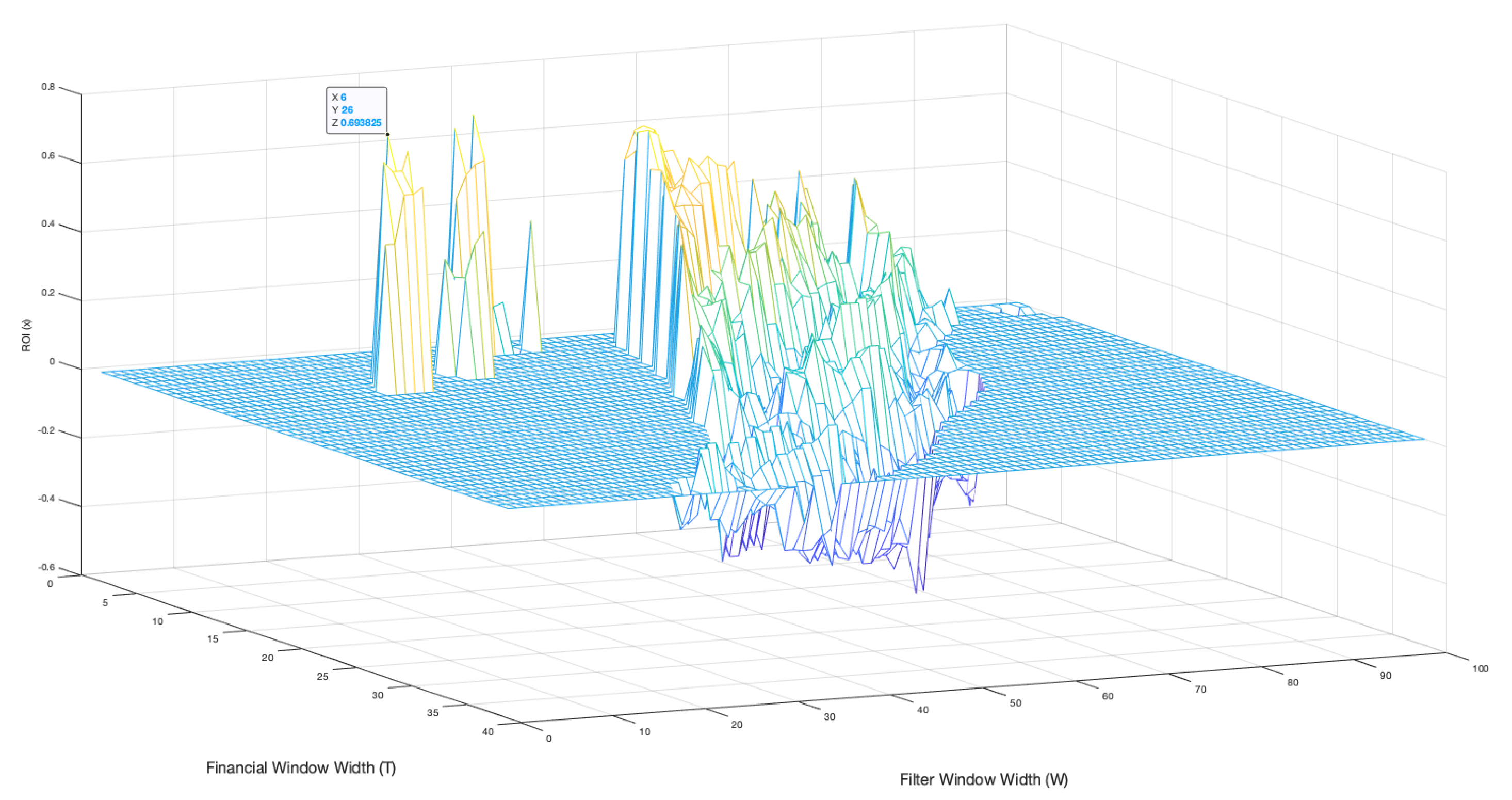

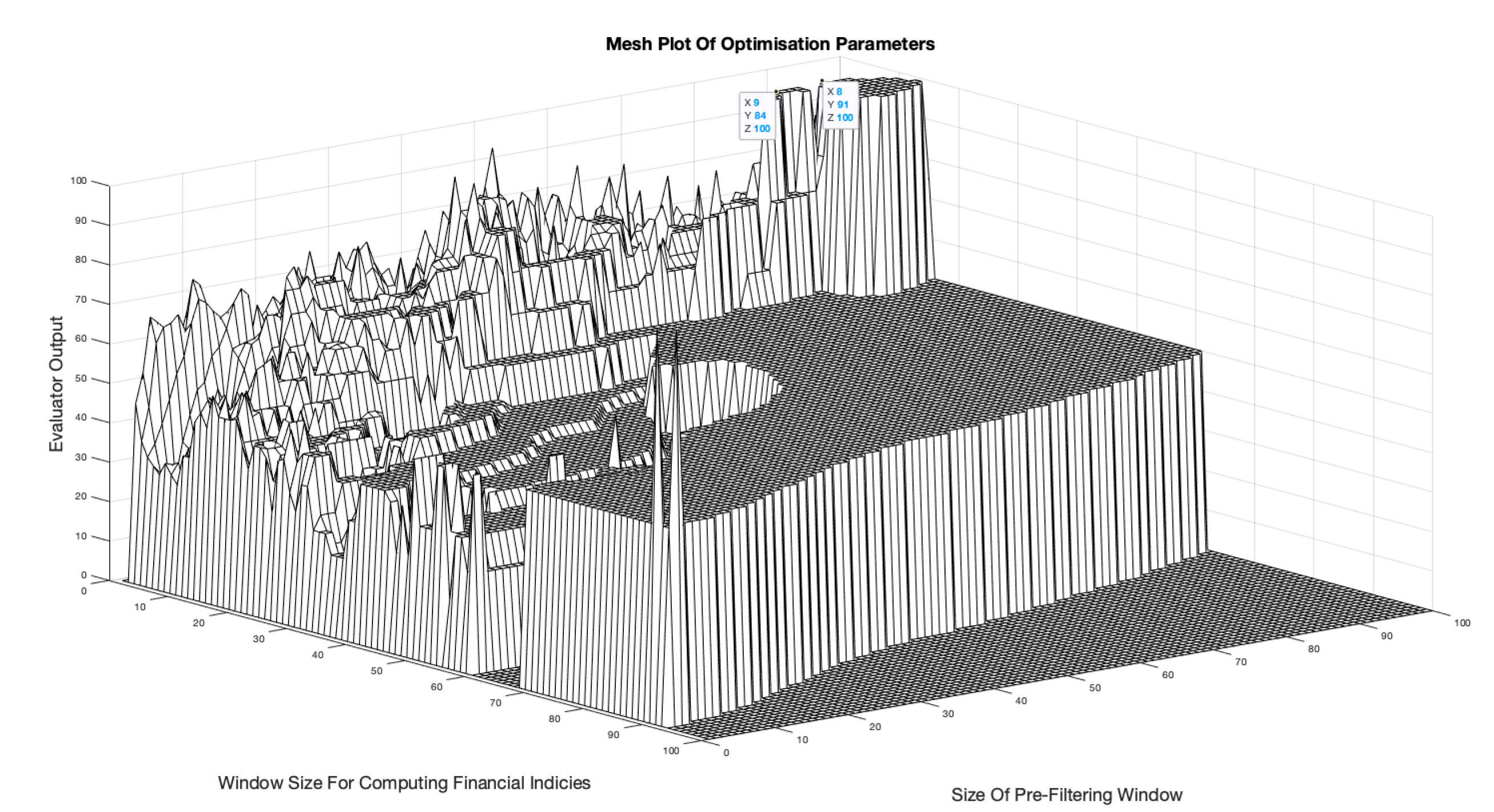

Figure 9 shows an example evaluator mesh for the BTC-USD 2020-21 time series, where the

x and

z axis’ represent the parameter combinations and the

y axis represents the accuracy percentage.

3.3. Code Development

Previous studies into FMH have supplied portions of code that can be used as a base to implement the equations presented in

Section 2.3 [

59]. A number of modifications and additional features were added for speed and ease of use. All of these relevant functions are presented in the Appendix. The main functions discussed in this section of the paper are:

, which is applied to the signal before calling the

function to assess the results.

3.3.1. System Optimisation

On initial testing, the function was taking minutes to complete for a parameter sweep (W, T). This put time limitations on progress. For this reason, the first step was to increase the performance of the code.

On an initial view, the iterative functions for calculating the metric signals, such as the Lyapunov Exponent (Listing 1), were using for loops, which take a total time of , where N is the total number of iterations and is the time required to complete the operations within one loop. The total time taken is increased, due to the function residing within another loop, to , where n is the total number of iterations of the outer loop.

LISTING 1: Lyapunov Function With A for Loop

%Compute the log differences of the data.

for n=1:N-1

d(n)=log(data(n+1)/data(n));

end

d(N)=d(N-1); %Set end point value.

L=sum(d); %Return the exponent.

Using vectorisation improves the speed of the function by a factor of N, as only 1 operation is required, therefore the new total time would be . This is a significant improvement when there are multiple functions being called on an iterative basis, all using data sets of data points. At this number of values, the performance is increased by a factor of , where a is the number of functions called within the loop that required a for loop. In this case, a minute runtime was reduced to seconds. A vectorised version of the function above is shown below.

Listing 2: Vectorised Lyapunov Function

%---------------------------------------------------------

% Create a vector of the data points 1 step ahead

step_ahead_data=[data(2:end),1];

% Calculate the log of the ratio of data points.

log_dif=log(step_ahead_data./data);

% Append differences log with the final value.

log_dif(end)=log_dif(end-1);

L_Exponent=sum(log_dif); %Return the Lyapunov exponent.

Further reading of the code provided reveals the use of a proprietary moving average function. On inspection, this performed in the same fashion as the native Matlab filter function with the exception that it modified the length of the input data, choosing to discard the first n elements that do not give a `fully loaded’ filter, instead of truncating the values. This has a dramatic knock-on-effect, as now the system outputs must be re-assigned a new length, using another for loop. Therefore, using the Matlab function removes another loop and decreases the complexity, as there is no longer a need to sync the system outputs together.

This is a significant benefit as the initial method of assignment relied on an x-axis array and not an index position, meaning that the output arrays had T leading 0’s before allocating the element as the value when compared to the input data. This made comparison very complicated. These changes dramatically improved the readability and speed of the functions which allowed for faster testing and therefore a more comprehensive analysis.

3.3.2. Additional Functions

In conjunction with the improvements to the system performance, a number of additional functions were created to ease analysis and handling of the cyrpto-currency historic data set. The first of these was a function capable of creating the required FTS from 7 years of hourly historical data. For this report, individual years of daily opening time data and months of hourly opening time data were required. Creating the

function, presented in Appendix (

Appendix A.9), allowed the raw full historical archive data set to be used. With the time step, where 1 is equal to 1 hour, and the end date of the time series, in this case 12th Feb 2022 at 00:00:00, the function is capable of finding the first element and taking the next element separated by the time step for the

in days.

The ROI function, shown in Appendix (

Appendix A.6), is capable of applying the resulting long/short position indicators to the real-time data and determining the price change, be it negative or positive. The summation of individual trade returns can be compared to the initial investment, the price of the first position, allowing the total percentage return on investment to be presented to the user for comparison to other market indices and trading methods. It achieves this by receiving arrays of both data and trade positions, then indexing the unfiltered price data at said positions, calculating the difference between elements. Price changes are then appended to an array before a summation and the ratios are calculated. This function was incorporated into the backtesting system so that returns are calculated concurrently with the system metrics, also allowing a returns mesh plot to be compiled when performing optimisation. There were a number of other functions created during the course of this work; however, as they are not essential to the presentation of the results, they are not presented here.

3.4. Short Term Prediction

The methods outlined in this paper so far, attempt only to predict a future movement in a FTS and use this prediction to recommend trading positions. It makes no attempt to predict the scale of said movement. Considering the variability of volatility within cryptocurrencies, attempts of prediction at arbitrary time points would be futile. However, the underlying assumption in this fractal approach is that a `strong’ BVR or LVR amplitude signifies relatively stable market dynamic behaviour, and are therefore less likely to undergo a Lévy flight. This window of stability can be exploited to conduct short-term price predictions in the effort to assist a trader achieving an optimum trade position over a short future time horizon. Setting a threshold to define this `stable period’ will assign a certain degree of confidence to any predictions made. With this approach, the BVR signal now represents not only a trend indicator but also an opportunity for short term price prediction.

4. Time Series Modelling Using Symbolic Regression

A period of trend stability empirically states that tomorrow’s price will be similar to today’s. Thus, formulating equations to represent the data up to that point in time (i.e. within the `stable period’) would allow discretised progressions into the future for a short number of time steps. This process can continue for as long as the stability period persists on a moving window basis.

This methodology suggests the use of a non-linear trend matching algorithm. In this respect, Symbolic Regression is a method of Machine Learning (ML) that iterates combinations of mathematical expressions to find non-linear models of data sets. Randomly generated equations using primitive mathematical functions are iteratively increased in complexity until the regression error is close to 0, or terminated by user subject to a given tolerance, for a pre-defined set of historical data.

4.1. Symbolic Regression

Symbolic regression is a data-driven approach to model discovery that identifies mathematical expressions describing relationships between input and output variables. Unlike standard regression methods, symbolic regression does not require the user to assume a specific functional form. Instead, it searches over a space of potential models to find the best fit for the data [

60,

61]. Key aspects include:

- (i)

Representation of Models: Models are represented as expression trees, where nodes correspond to mathematical operators (e.g., +, −, ×, ÷) and functions (e.g., sin, cos, exp, log), while leaves correspond to variables or constants.

- (ii)

Search Space: The search space includes all possible mathematical functions, expressions and combinations thereof within a specified complexity limit.

- (iii)

Fitness Evaluation: Fitness is based on criteria such as accuracy (e.g., mean squared error) and simplicity (e.g., number of nodes in the expression tree).

- (iv)

Parsimony: Balancing accuracy and simplicity prevents overfitting.

The applications of this approach using a specific system - TuringBot - is discussed further detail in the following section.

4.2. Symbolic Regression using TuringBot

Symbolic Regression is based on applying biologically inspired techniques such as genetic algorithms or evolutionary strategies. These methods evolve a population of candidate transformation rules over successive generations to maximise a fitness function. By introducing mutations, crossovers, and selections, the approach can explore a vast space of mathematical configurations. This approach is particularly useful in generating non-linear function to simulate complicated time series. In this section, we consider the use of the TuringBot to implement this approach in practice.

In this work, we use the

TuringBot [

62], which is a symbolic regression tool for generating trend fits using non-linear equations. Based on Python’s mathematical libraries [

63], the TuringBot uses simulated annealing, a probabilistic technique for approximating the global maxima and minima of a data field [

64]. For this reason, we now provide a brief overview of the TuringBot system.

4.3. TuringBot

TuringBot [

62] is an innovative AI-powered platform designed to streamline the process of algorithm creation and optimisation. By leveraging cutting-edge artificial intelligence, TuringBot enables users to generate, test, and refine algorithms for a variety of applications, such as data analysis, automation, and machine learning, without requiring extensive programming expertise. Its user-friendly interface and advanced capabilities make it an invaluable tool for professionals, researchers, and students seeking efficient solutions to complex computational problems. TuringBot stands out as a versatile and accessible resource in the ever-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence and technology. TuringBot.com is a symbolic regression software tool designed to automatically discover analytical formulas that best fit a given dataset. Symbolic regression differs from traditional regression techniques by not assuming a predefined model structure; instead, it searches the space of possible mathematical expressions to find the one that best explains or `fits’ the data. TuringBot was developed to make this process efficient, intuitive, and accessible, especially for those without a background in machine learning or advanced data science.

Launched in the late 2010s, TuringBot was created in response to the growing need for interpretable artificial intelligence models. While most machine learning tools rely on complex neural networks or ensemble models that are difficult to understand and verify, TuringBot emphasised simplicity, transparency, and mathematical interpretability. By combining evolutionary algorithms with equation simplification techniques, TuringBot is able to produce human-readable formulas that describe complex datasets. This makes it particularly valuable in scientific, engineering, and academic contexts, where understanding the model structure is as important as prediction accuracy. The software is available for Windows and Linux and comes with a straightforward graphical user interface, allowing users to load data, configure parameters, and generate formulas with minimal setup. TuringBot also offers command-line integration for advanced users and supports exporting results for further analysis. As of the mid-2020s, TuringBot has gained a user base across various domains, from physics and finance to biology and control systems. It continues to evolve with improvements in computational performance and integration with modern workflows. The name “TuringBot” pays homage to Alan Turing, reflecting the tool’s focus on combining algorithmic intelligence with human-understandable outputs.

In an era increasingly focused on explainable AI, TuringBot stands out as a lightweight, focused solution for data modelling grounded in classical mathematical reasoning. In this context, the system uses symbolic regression to evolve a formula that represents a simulation of the data (a time series) that is provided, subject to a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the data and the formula together with other `solution information’ and `Search Options’.

In this work, we are interested in using the system to simulate a cryptocurrency time series of the types discussed earlier in the the paper. For this purpose, a range of mathematical operations and functions are available including basic operations (addition, multiplication and division), trigonometric, exponential, hyperbolic, logical, history and `other’ functions. While all such functions can be applied, their applicability is problem specific. This is an issue that needs to be `tempered’, given that a TuringBot generated function will require translation to a specific programming language. This requirement necessitates attention regarding compatibility with the mathematical libraries that are available to implement the function in a specific language and the computational time required to compute such (nonlinear) functions. There is also an issue of how many data points should be used for the evolutionary process itself. In this context, it is noted that the demo version used in the case studies provided in the work, only allows a limited number of data points to be used, i.e., quoting from the demo version (2024): `Only the first 50 lines of an input file are considered’.

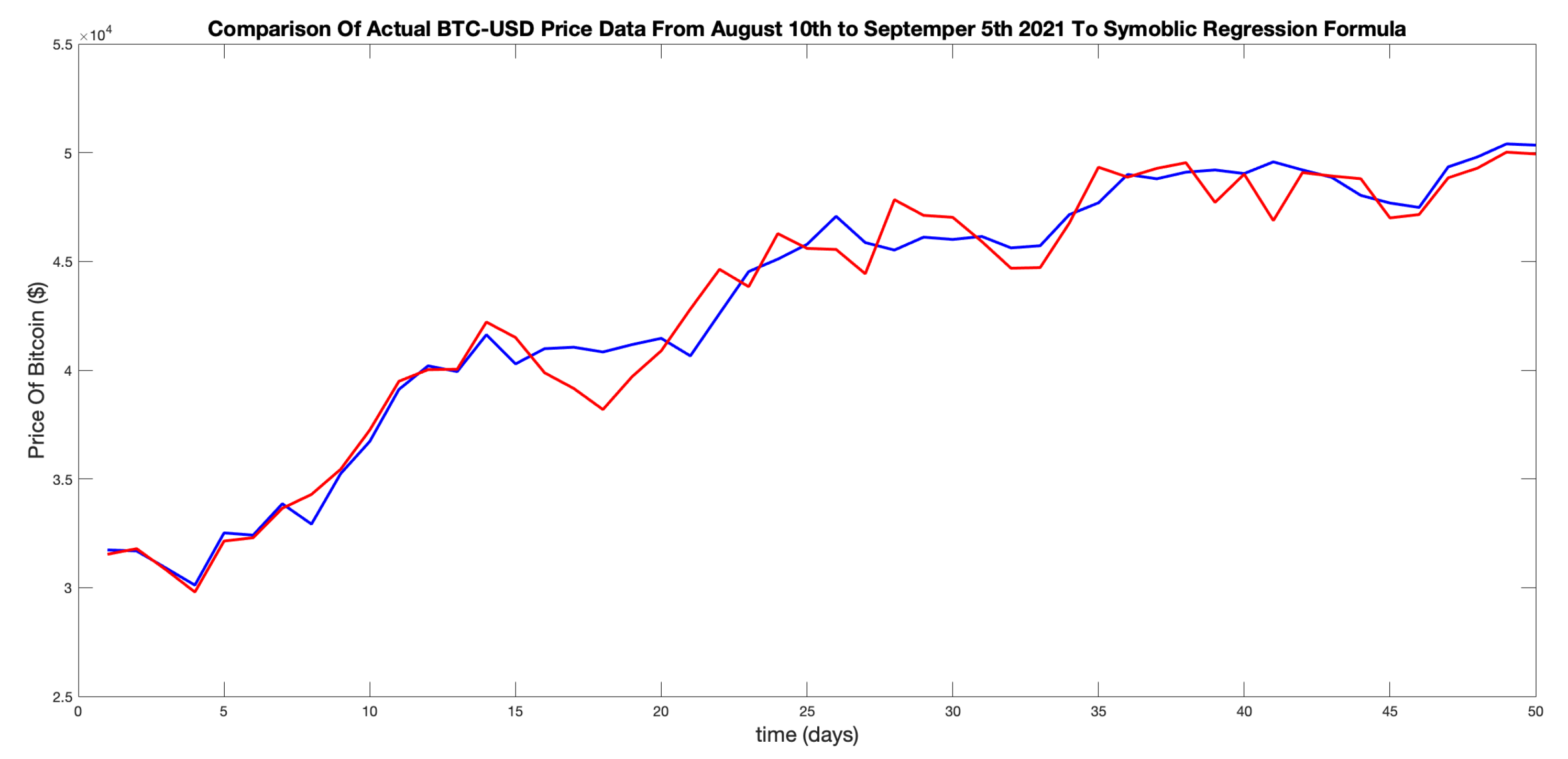

4.4. Example Case Study

Figure 10 shows an example of a set of 50 BTC-USD data points from August 10th 2021 to September 5th 2021 (red) and the trend match outcome of the TuringBot ML system (blue). These results were acquired by manually entering 50 data points and running the system. Here, the equation of the line was achieved after

iterations with a RMS error of

and mean absolute error of

.

The non-linear equation for the `best fit’ shown in

Figure 10 is given by

Figure 10 shows no future predictions; it is purely a trend match for a period of relative `trend stability’. The principal point is that Eq. (

15) can be used to evolve a small number of time steps into the future to estimate price fluctuation. By coupling the results of doing this with the scale of the LVR, for example, a confidence measure can be associated with the short term forecast that are obtained. This is because a large positive or negative values of the LVR reflects regions in the time series where the log-term volatility is low, thereby providing confidence the the forecast that is achieved. This is the principal associated financial time series analysis provide in the following section.

5. Bitcoin and Ethereum - Financial Time Series Analysis

With the derivation of market indexes and subsequent implementation in Matlab, an analysis of BTC and ETH FTS can be performed. Using the

function, a collection of series were created for two time scales, yearly opening day prices ranging from Feb 2016 - Feb 2022, and monthly opening hour prices from Nov-Feb. A List of these series for BTC-USD is given in

Table 2, the same collection was created for ETH-USD.

Using these, the analysis can be done on separate time scales, to not only determine the systems overall performance, but also whether the system can capitalise on the self-affine nature of the crypto-markets. For the purpose of the report, the BVR was used for analysis with the corresponding LVR results presented later in the paper for comparison.

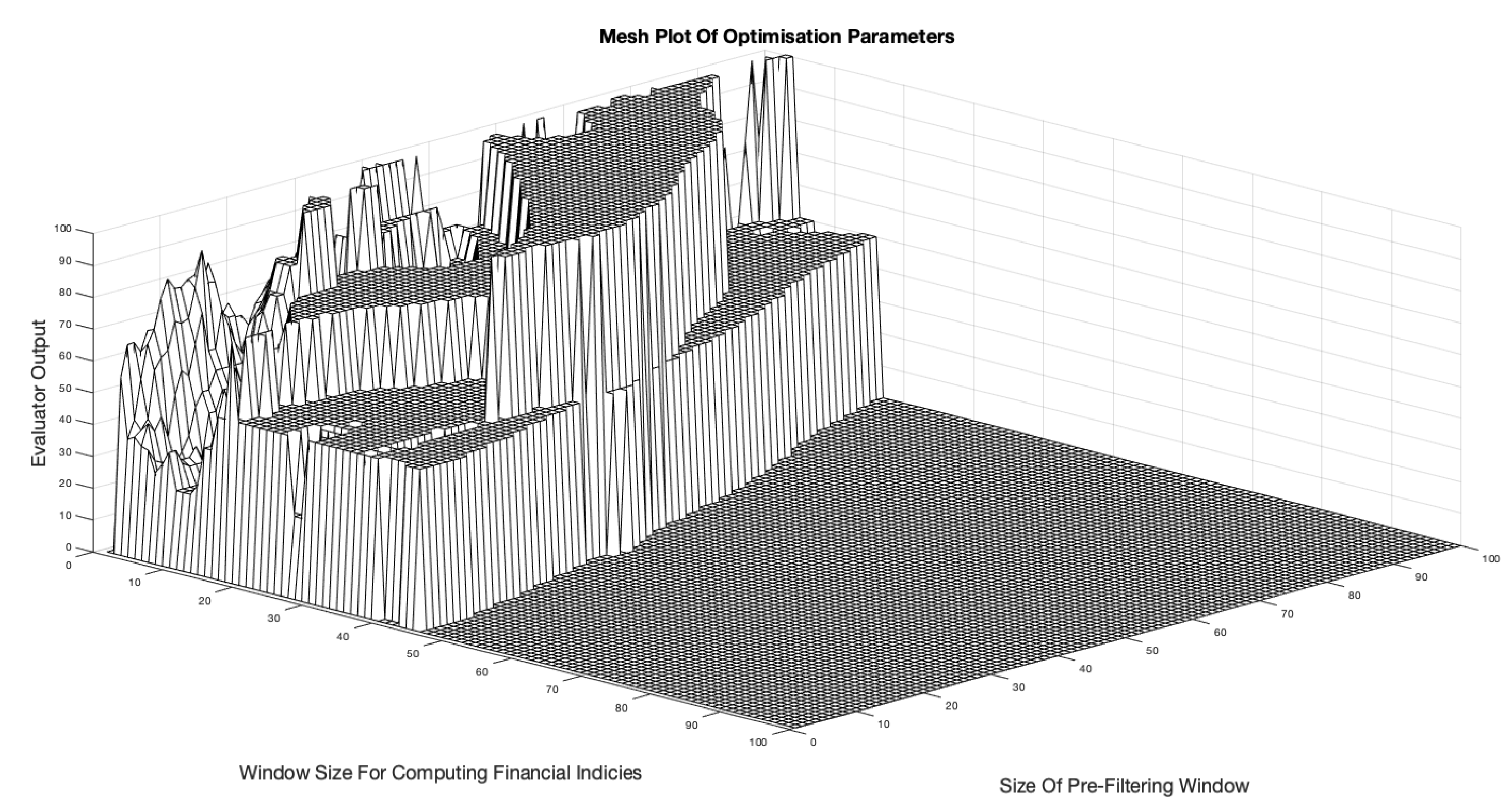

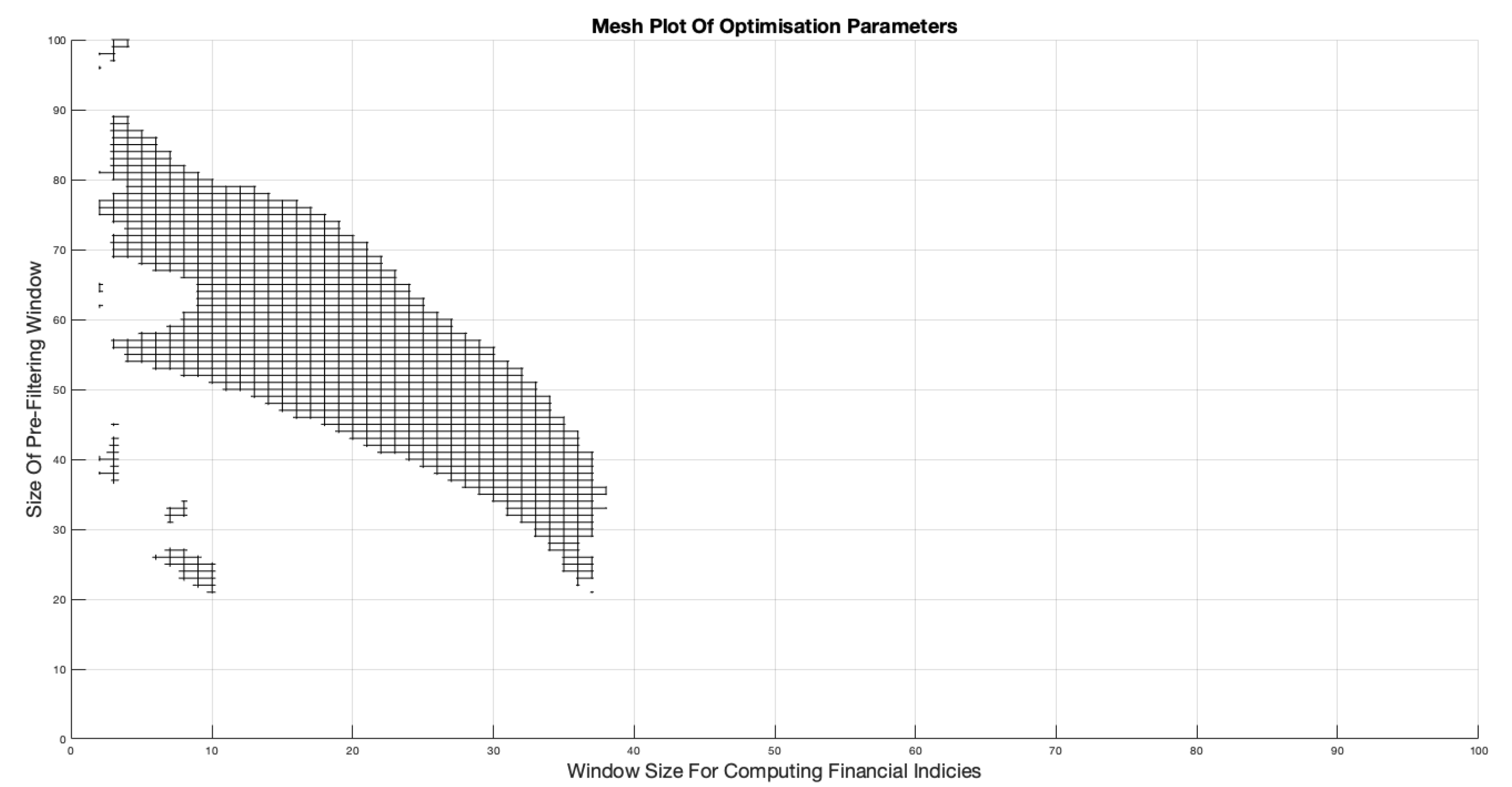

5.1. Daily Backtesting and Optimsiation

The first step in the analysis was to not only find the optimum parameter combinations for highest accuracy and profit, but to define a rule for selecting these parameters from a set range. Starting by running the optimisation function for the BTCUSD2021 time series, the range of parameter combinations that resulted in a 100% evaluator accuracy was observed in a three dimensional mesh plot. For the remainder of this section, the Filtering Window Width and Financial Calculation Window will be referred to as

W and

T respectively.

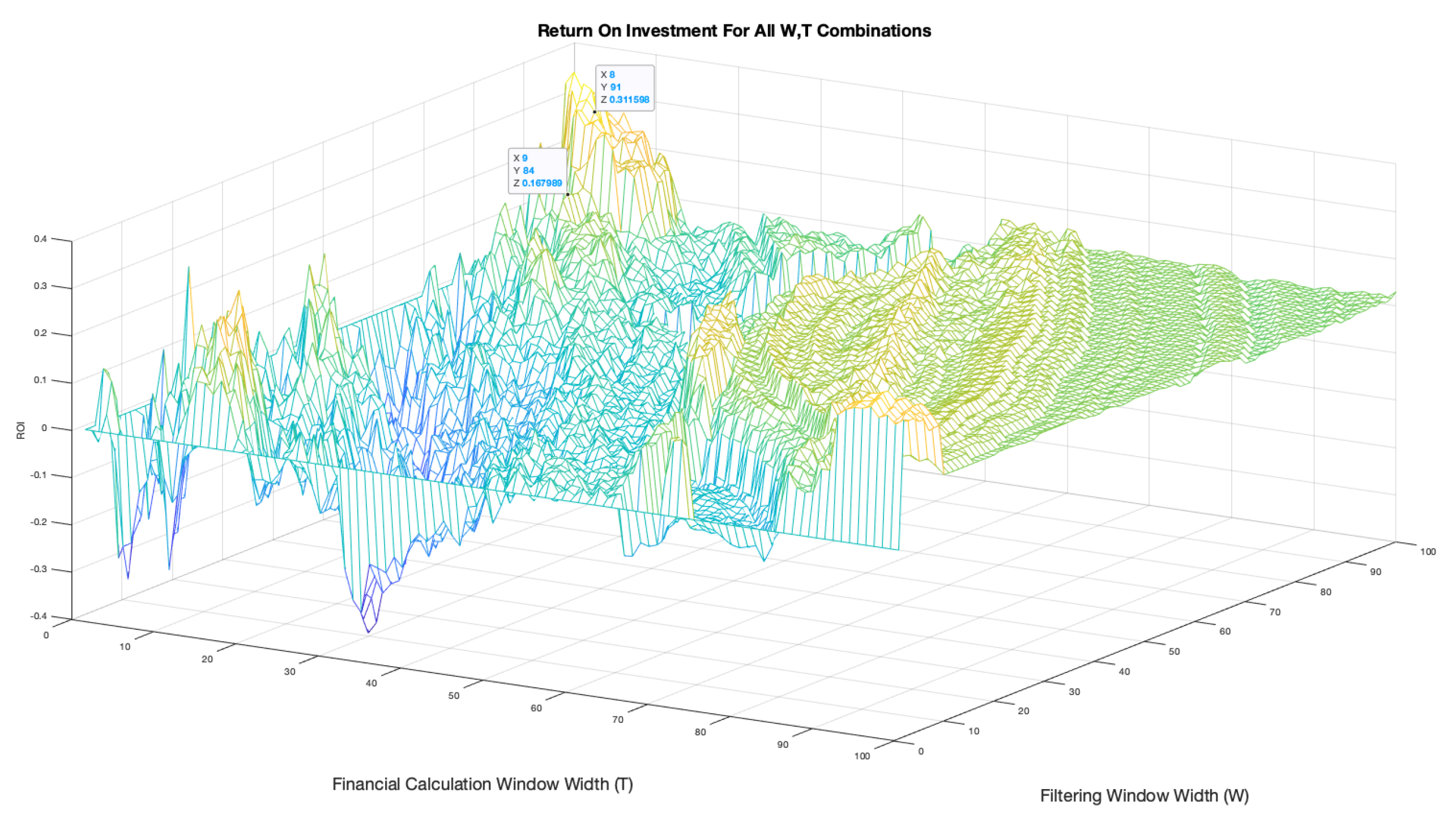

Figure 11 shows the resulting mesh graphic produced by the backtesting system.

It displays a broad range of W, T combinations. Due to the delay caused by the filtering process, it is logical to choose low values of W. From the mesh there are W values in excess of 90 data points, which is equivalent to over 3 months of delay in the analysis. However, small values (i.e. ) may not smooth the data enough to make the system perform well. This is confirmed by the lack of a accuracy result with .

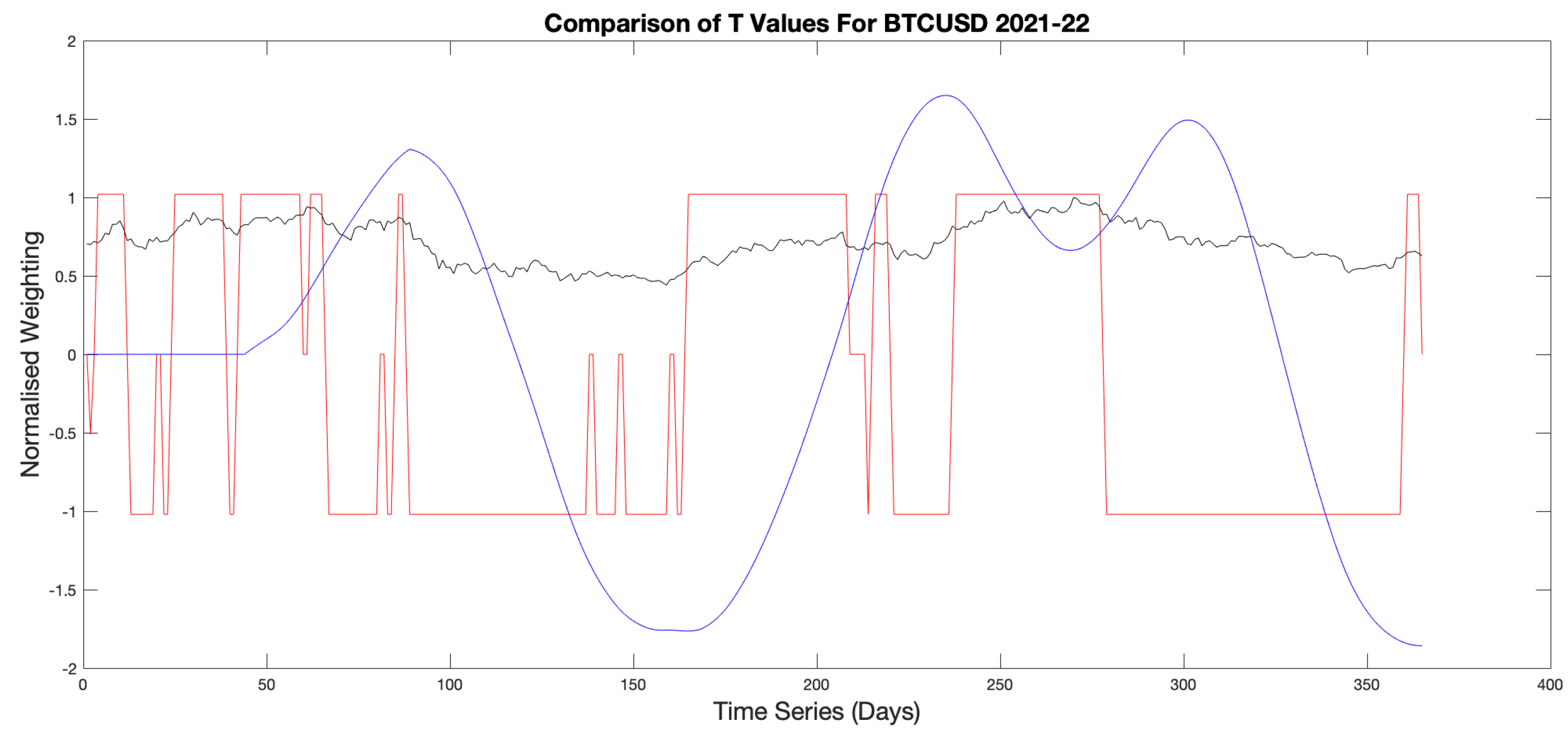

The effect of different sizes of

T, however, is not yet fully clear. Backtesting for two

combinations, one with a low

T value and one with a high value, is presented in

Figure 12 for BTCUSD2021. It shows that for

the metric signal becomes a binary representation, alternating between

. This gives the trader no indication of a fluctuation in

leading to a trade position.

High

T values result in sinusoidal fluctuations in

making it hard to define periods of high stability and fast movements in trends. This is due to the assumption of stationarity within the windowed data, used to approximate the convolution integral in Equation (

9), not being feasible for such a large value of

T. Given that

W values should minimise delay whilst providing enough filtering to reduce noise, a suitable limit for the values of

T would be

.

From this comparison, T values should aim to be . W values should aim to be small enough to reduce system delay whilst maintaining a smooth enough price signal for good system performance.

To further study the optimum

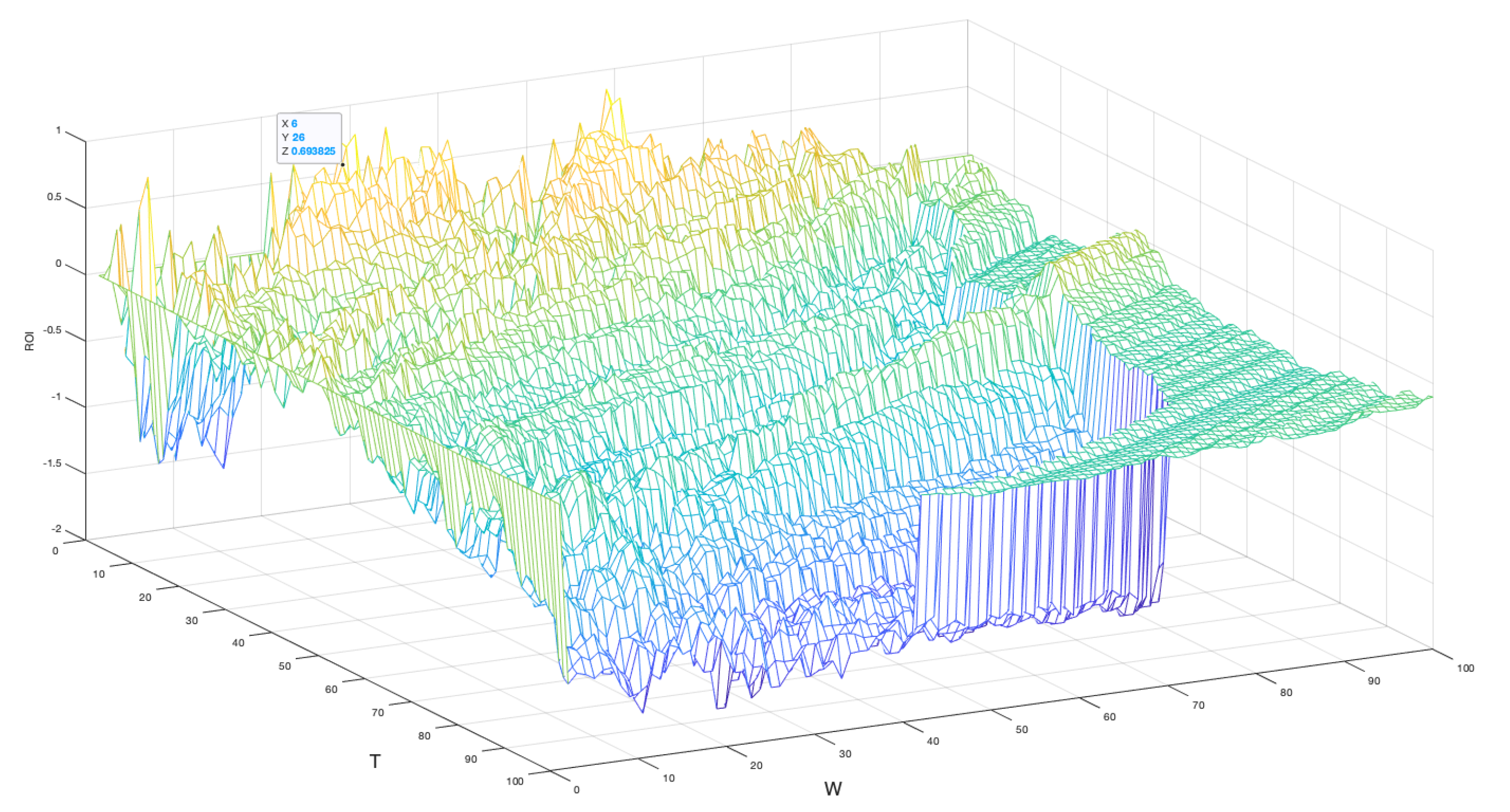

range, the array of

combinations that returned 100% accuracy (

) from the

function can be used to generate a new mesh plot of ROIs. As presented in

Figure 13, this proves that not all optimum positions result in profitable trade positions. High value combinations of

generally result in a loss over the year. However, from the topology in

Figure 13, it is clear that low values of

result in profitable trades irrespective of

W.

This provides evidence to suggest that the highest returns are achieved when a low value of

T is chosen for the smallest

W value, in this instance

(For

combinations only). To see how the returns for

positions compare to non-optimum positions, i.e.

combinations that produced less than 100% accuracy, a separate mesh plot was generated where all combinations are considered. This is presented in

Figure 14, where yellow represents high ROIs and dark blue low (negative). For the mesh topology, this mesh provides evidence that the

combinations do create high returns relative to all combinations. Interestingly, it also displays that very small

W,

T values create large losses and parameter sets where

also create losses.

A significant discovery extracted from this mesh plot is that the highest possible returns do not occur at the optimum positions. The highest ROI from

Figure 14 is selected and the surrounding peaks do rise higher. This can be interpreted as the result of micro-trends in the time series where non-optimum parameters have fortuitously recommended trades during a local peak or trough that has yet to influence the windowed data. The aim of the system is to ensure accuracy and confidence in the trading strategy, therefore, optimum evaluator parameter combinations are preferred to highest profit achieving combinations. This priority definition warrants another evaluation of the optimum positions.

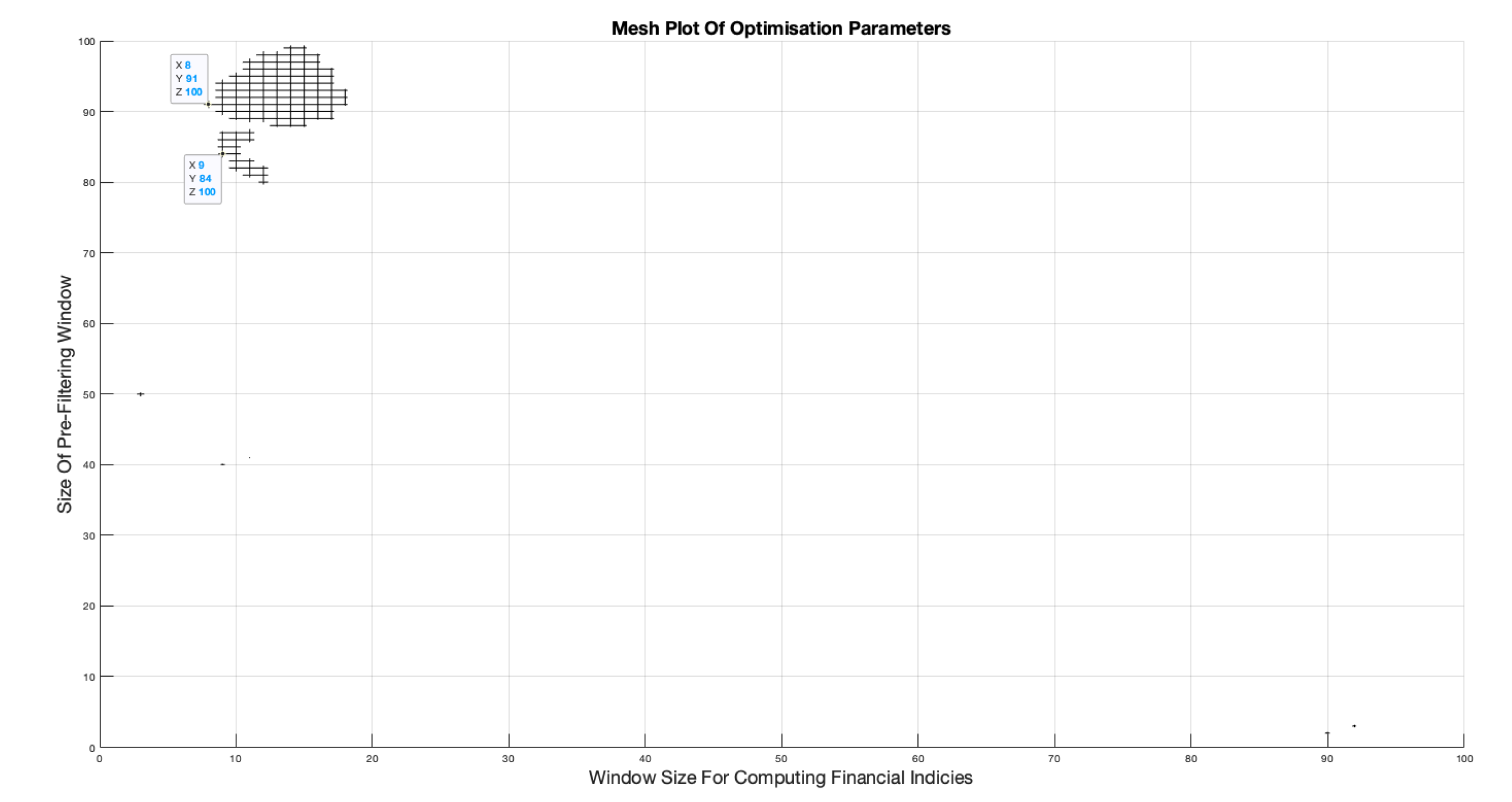

Figure 15 presents a different perspective of the data displayed in

Figure 11 where only the 100% accuracy combination are displayed on a two dimensional `Top Down’ view.

Figure 15 Identifies a small grid at the bottom left hand corner where

W values are within the lowest range and

T values are

. Knowing that this grid achieves the highest ROIs as shown in

Figure 14, it is therefore, preliminarily proposed that this `Grid of Choice’ (GOC) represents the best range of

to be chosen from. To provide more evidence of this theory, the same approach was taken for the other yearly time series of BTC-USD. Each year displayed the same properties lending weight to the GOC theory and evidencing that the assumption of a fractal stochastic field is constant throughout the data.

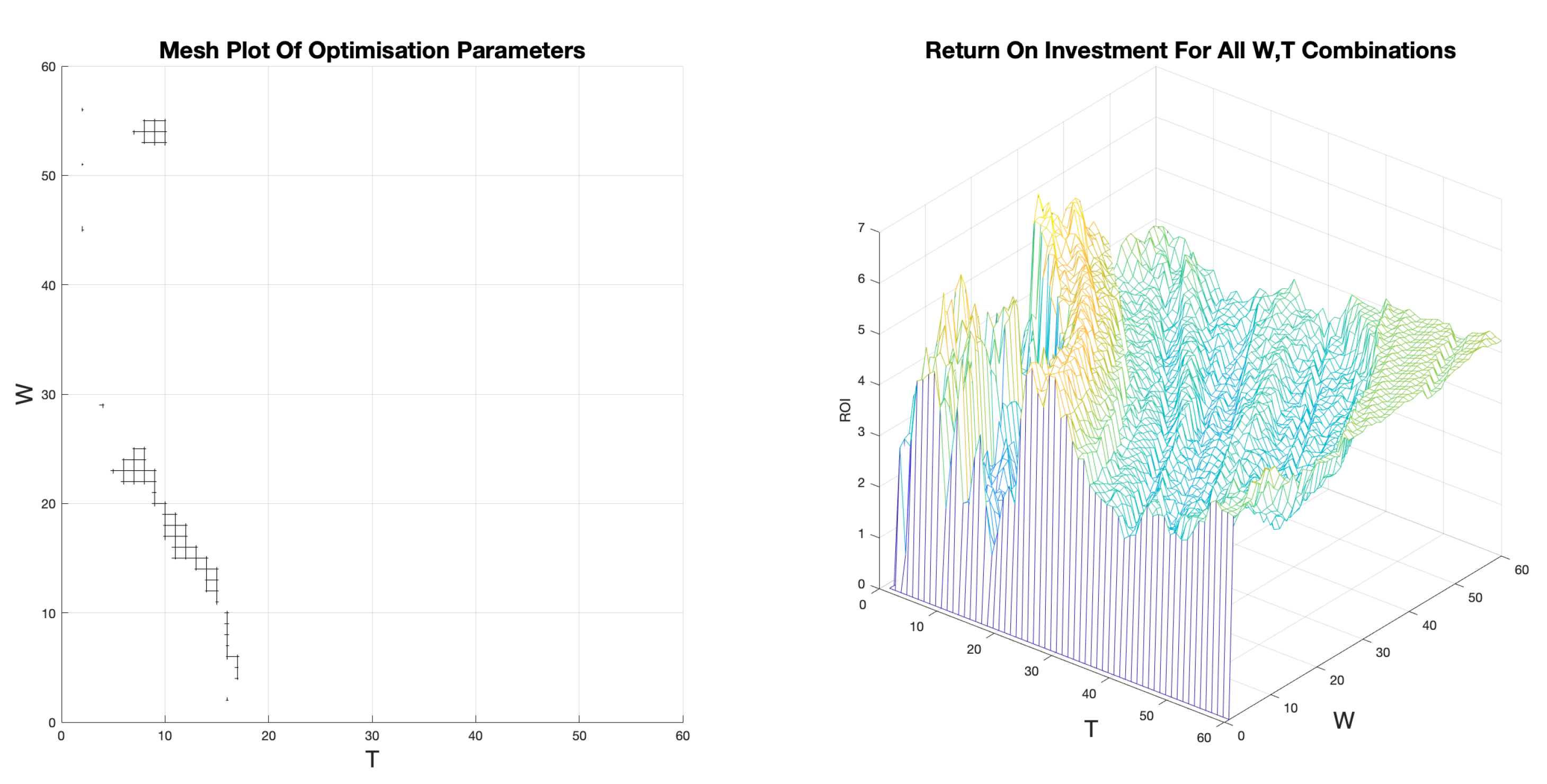

Figure 16 shows the resulting `Top Down’ optimum parameter mesh (left) and the ROI mesh (right) for BTC-USD 2020-21. It shows results consistent with that of BTC-USD 2021-22. The ridge of high (yellow) returns visible in

Figure 16 are in some cases

higher than the returns achieved under

. However, most of these parameter combinations violate the required conditions, in this case

and high

W values. This could be attributed to the fact that in 2020 BTC-USD had an almost constant upward trend.

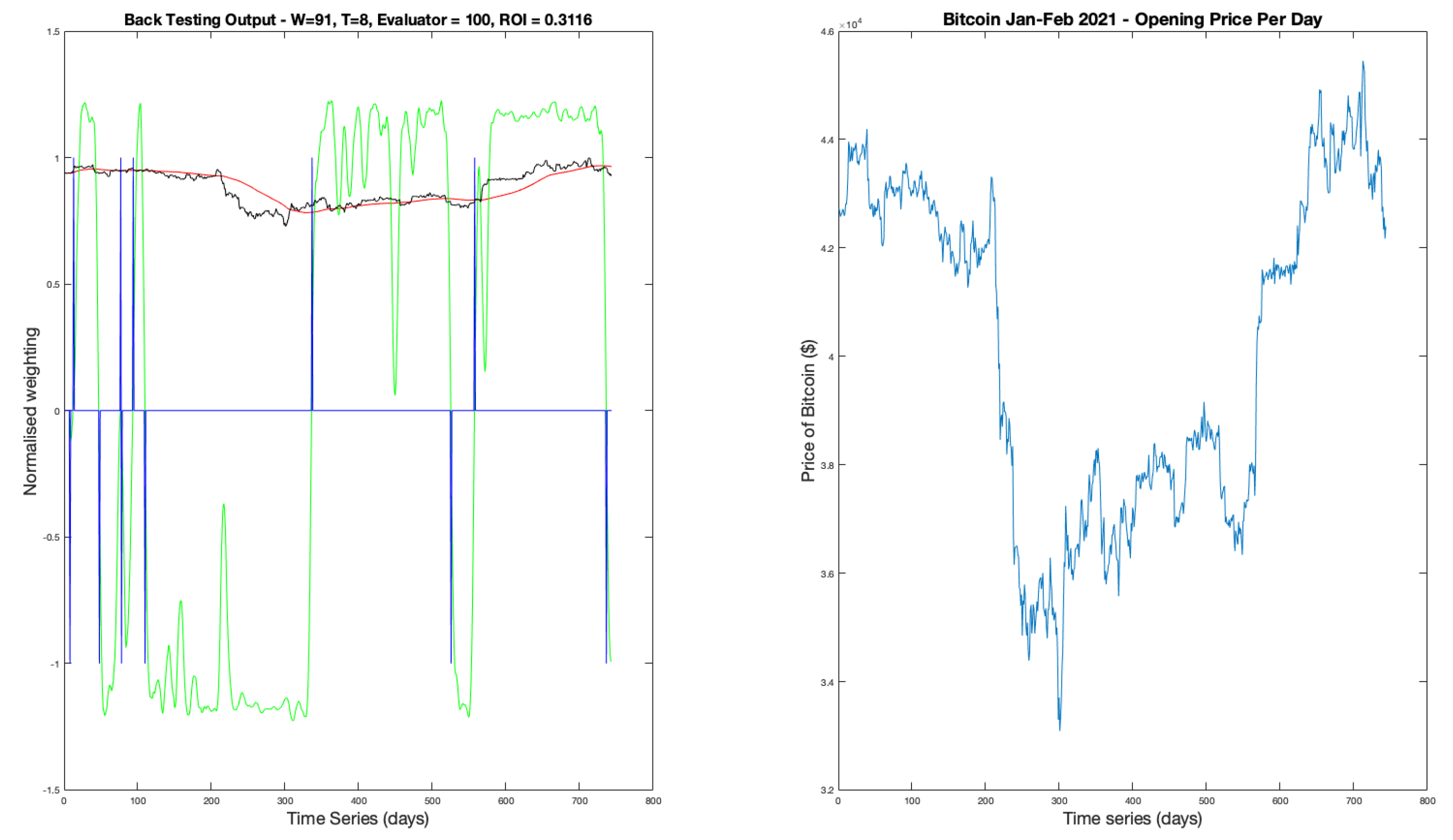

With optimum parameters for 2021-22 (

), backtesting was performed.

Figure 17 shows the graphical output from the function with,

in green,

in blue, the filtered data in red and raw price signal in black. The same color format will be used for all backtesting outputs in this report. It displays the 7 trades, resulting in a

return in a year when Bitcoin’s value against the dollar widely fluctuated and lost value overall.

The nature of the trading delay is clear, with the filtered data (red) lagging behind the raw price data (black). The signal shows that there are periods of general trend stability in both bear and bull directions. By inspection, it can be seen that although some trade indications occur in the trough of the filtered data, when applied to the raw signal, the difference between the two price signals results in an overall loss for that transaction. This is a result of the micro trends Bitcoin displays coupled with the trading delay and inherent volatility.

The backtesting was completed on the same basis for the rest of the BTC-USD financial time series as well as ETH-USD. Results are displayed in

Table 3. From these results, it is not always possible to achieve 100% accuracy. However, this does not lead to a loss for the year. It should be noted that during the analysis of ETH-USD data, the correlation between optimum parameters and high returns, including the GOC, was observed to provide further evidence in favour of the parameter selection theory.

5.2. Hourly Backtesting and Optimisation

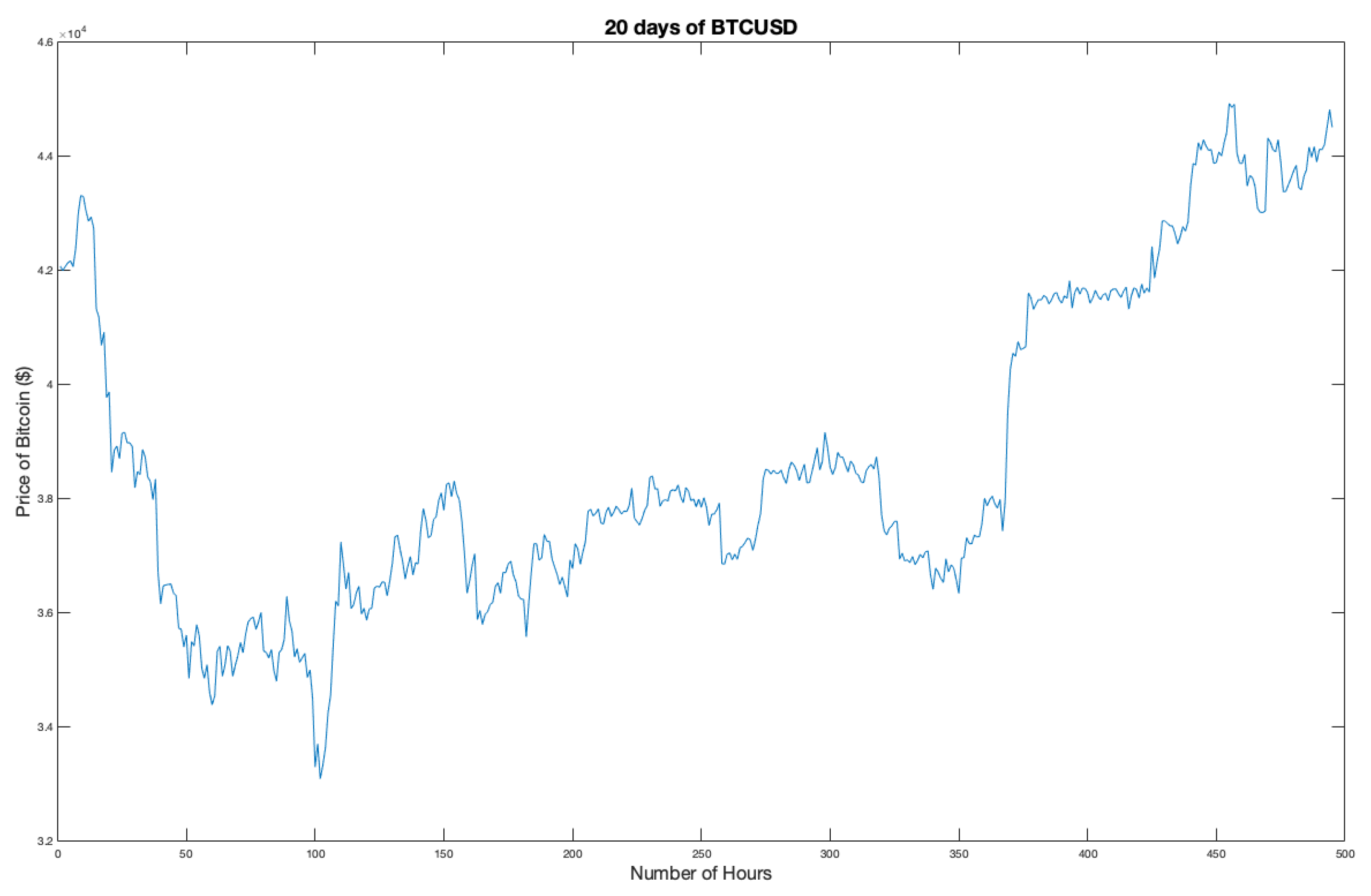

Given that the BTC-USD market has been shown to be a self-affine fractal signal exhibiting scale invariance, backtesting over a different scale, in this case hourly prices, should return similar results. However, as can be seen from

Table 2 the monthly time series have double the number of data points. For this reason, the field is expected to have a higher level of detail and therefore noise. To inspect this,

Figure 18 shows a 20 day extraction from the Jan-Feb 2022 time series. The high volatility and wild price fluctuations are more prevalent than for the daily data, with micro-trends occurring faster with bigger relative movements.

Due to the increased noise content, a higher level of filtering was expected to maintain an acceptable level of accuracy and therefore confidence in the recommended trade positions. This results in a GOC where T levels remain consistent but W values rise significantly.

As with the daily time series, the first step is to run the

function for the BTCUSD Jan-Feb 2022 field.

Figure 19 shows the resulting mesh plot for all parameter combinations. Compared to the daily data, the general topology is far lower and as excepted, 100% accuracy is achieved with much higher values of

W, in this case

.

T values remain consistently low, an expected result due to the self-affinity of the underlying price signal.

Taking a further look at the `Top Down’ view of the optimisation mesh plot in

Figure 20, few accurate combinations of parameters exist. However, even with the sparsity of the results, there is still a clear grid containing the small range of

W values for low

T values. This is consistent with the expected findings. Producing the mesh plot for parameter returns,

Figure 21, confirms that the GOC remains a source of strong returns.

Analysing the mesh plot of ROIs, the topology suggests an ideal location for parameters with returns around

being a peak surrounded by low and negative results. This lends further evidence that the GOC is a valid theory. An interesting outcome is the plateau of high returns for high

T values, irrespective of what filtering is applied. Many of these

combinations are invalid due to

or

, the ideal range of filtering for this data. An explanation for this could be that for high values of

T, the metric signal

becomes heavily sinusoidal, containing low frequencies. This could result in low numbers of trades operating at heavily delayed trade positions that are fortuitously executed. Other anomalous peaks in returns surrounding the origin also violate the

rule. Such small filtering sizes increases the expected number of trades to high and infeasible values, due to the fees synonymous with trading cryptocurrencies. A comparison of these two invalid

combinations is shown in

Figure 22. In the

backtest, a 0% accuracy still gives a positive return, confirming the anomalous nature of these combinations.

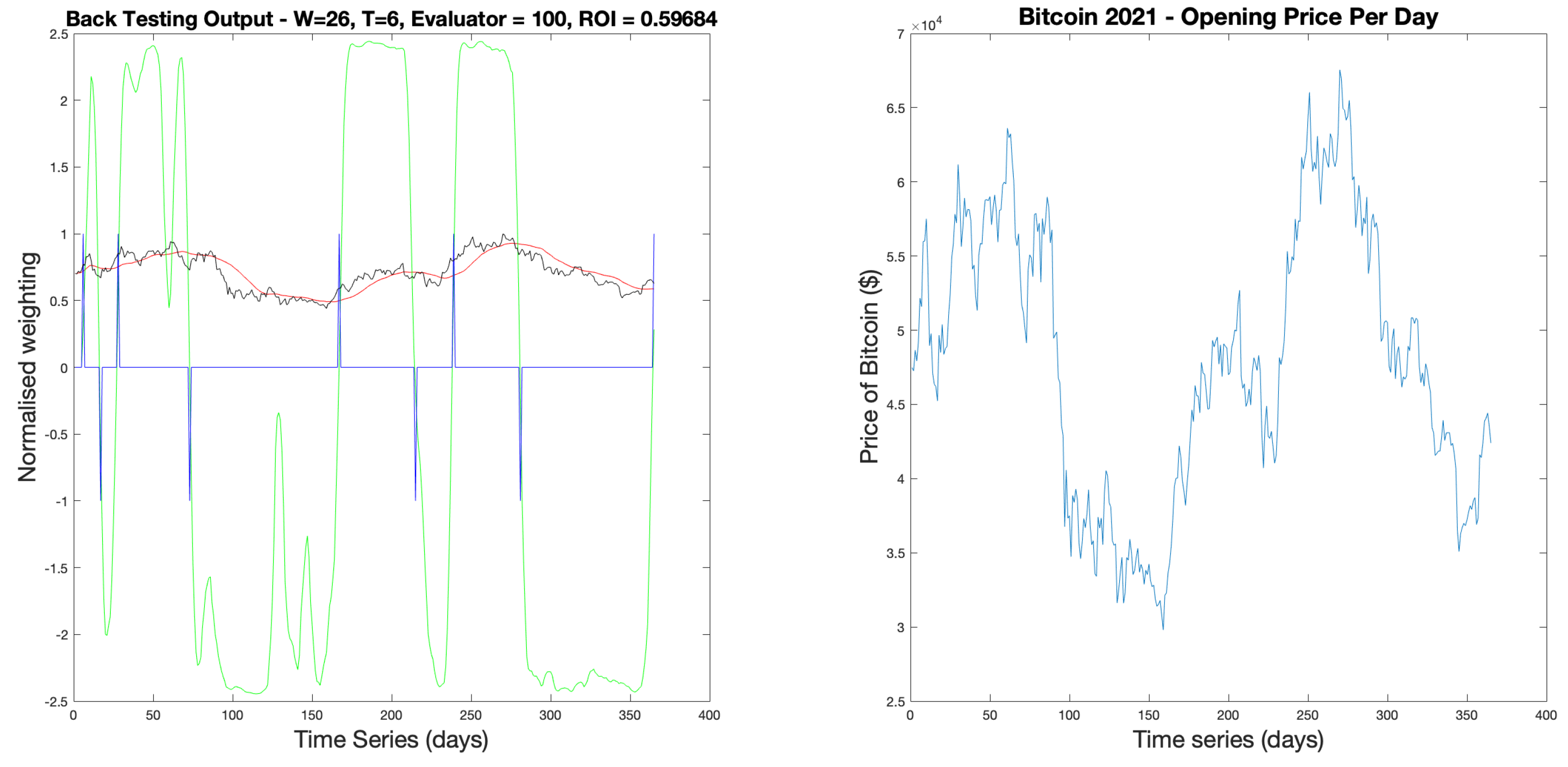

The sharp and focused nature of the

peak suggests that the effect of micro trends in the hourly time series is greater. Returns are reduced rapidly at small deviations from optimum combinations. The backtesting output for

is shown in

Figure 23. 9 trades are executed resulting in a

ROI. The increased volatility in the time series is reflected in the corresponding volatility in

.

When applied to the other monthly time series, an interesting observation is the increase of filtering required as the fields evolve in time, suggesting that both BTC and ETH are entering a phase of high volatility.

Table 4 displays the results for each monthly financial time series used in backtesting.

5.3. Analysis Using LVR

The backtests performed in previous sections were repeated for yearly financial time series using the LVR to observe any changes in results, The equivalent graphical LVR output for BTCUSD2021 is displayed in

Figure 24. Results were consistent with the BVR metric, confirming that both ratios are valid for trend analysis. The LVR produced a metric signal with a greater amplitude than

which provides more flexibility to change the conditions on which the trading positions are recommended. Currently trades are considered viable only when

crosses the axis. However, if the

signal was re-programmed to produce a delta peak when the signal reaches a certain threshold, say

, this could reduce trading delay. A full set of ROI results for all BTC and ETH time series is presented in

Table 5.

5.4. Returns On Investment - Pre-Prediction

A full comparison of

and

returns compared to the standard `Buy and Hold’ strategy (B&H), where the price change over the whole time series is taken, is shown in

Table 6.

It shows that the proposed system outperforms B&H for every financial time series under consideration, both for BTC and ETH coins, with the exception of BTCUSD 2016-17 LVR. In bear dominant years of high market loss, such as BTC 2018-19, the system was capable of producing a positive return. In other cases, where the year saw high overall gains, the system was able to improve further.

These returns are high when compared to other stock market indexes, with average returns considered to be , including; S & P Commodity index returning an average between 2009 and 2019, and the S & P 500 an average of between 2005 and 2019. Overall, returns for the hourly data sets also proved to beat the B&H strategy.

Table 7.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for hourly financial time series using both LVR and BVR indicators compared to Buy & Hold strategy (B&H).

Table 7.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for hourly financial time series using both LVR and BVR indicators compared to Buy & Hold strategy (B&H).

| Year |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

| |

ROI -

|

ROI -

|

B&H (%) |

ROI -

|

ROI -

|

B&H (%) |

| Nov-Dec |

16.4 |

11.8 |

-23.8 |

27.5 |

27.2 |

-13.5 |

| Dec-Jan |

16.7 |

20 |

-13.4 |

12.8 |

15.5 |

-20.3 |

| Jan-Feb |

29.7 |

31.1 |

-0.78 |

47.8 |

51.1 |

-9.4 |

5.5. Short Term Price Prediction Using Machine Learning

As discussed in

Section 3.4, periods of high trend stability, indicated by a `strong’ BVR amplitude, signify the opportunity for short term prediction using Symbolic Regression (SR). As this period continues, non-linear formulas can be re-generated every day based on historical opening prices on a rolling window basis. Once generated for a time point

, the formula can be evolved for short term future time horizons

,

,

,... where

n is the total number of data points used to create the formula. The hypothesis is that data points within the stable trend period can be used to generate non-linear formulas capable of guiding a trader to the optimum position execution, with the prices preceding the period being volatile and therefore detrimental to the SR algorithm.

Applying this to the BTCUSD2021 time series, a high BVR period can be defined as

or

and designated

. The BVR signal reaches this threshold on the 21st of August, indicating the ability to utilise SR. Advancing forward 34 days to September 10th, still within the

, the TuringBot is used to generate a trend formula using the previous 34 days opening prices (

). The resulting solution is

Using this equation, data points

,

,

, ... can estimate price fluctuations over a short time horizon.

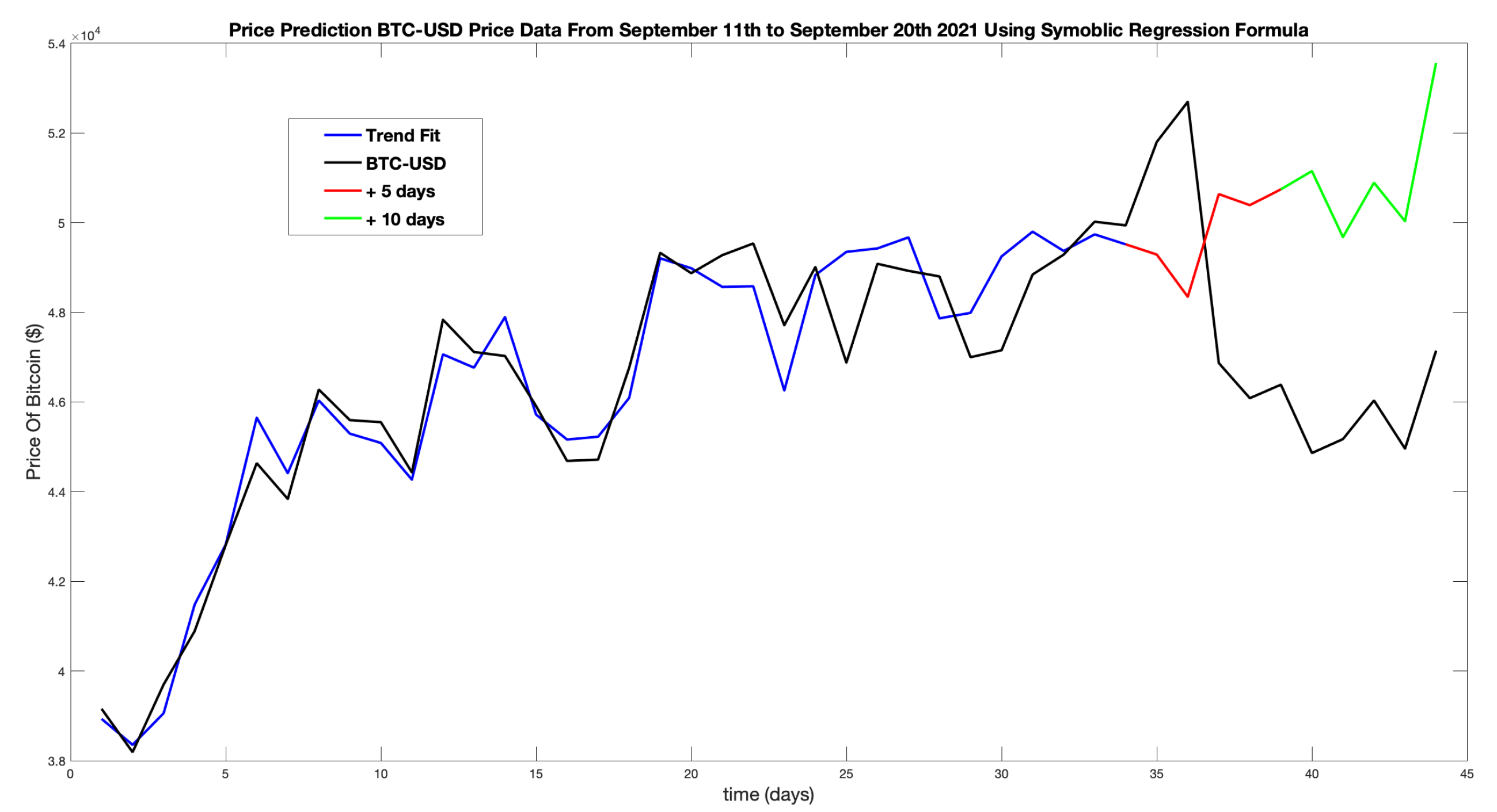

Figure 25 shows the actual BTC-USD price data from Aug 21st to Sep 20th in black, the trend `fit’ for historical data up to Sep 10th, shown in blue, and then future estimated prices for + 5 days to Sep 15th in red and +10 to Sep 20th in green. Each price estimation figure will use the same format.

Observing the SR output graph, it is clear that the prediction provides no useful guidance. It doesn’t predict the large drop in price on day 36, nor the increase in the preceding days. An optimal profit would have been achieved by exiting the long position on day 36 at

. However, the prediction estimates

, a price gap of nearly

. During the backtesting for this data set, a short position was recommended on September 20th at

. Using

Figure 25 as a reference, no increased profit would have been created. On September 16th (

)

drops below

and

ceases. This proves that no additional profit could have been made by the ML system. Formulas were generated for days 30-34, to see if an earlier prediction would have yielded better results. In every case, the estimated future prices gave no accurate guidance and failed to optimise the sell position.

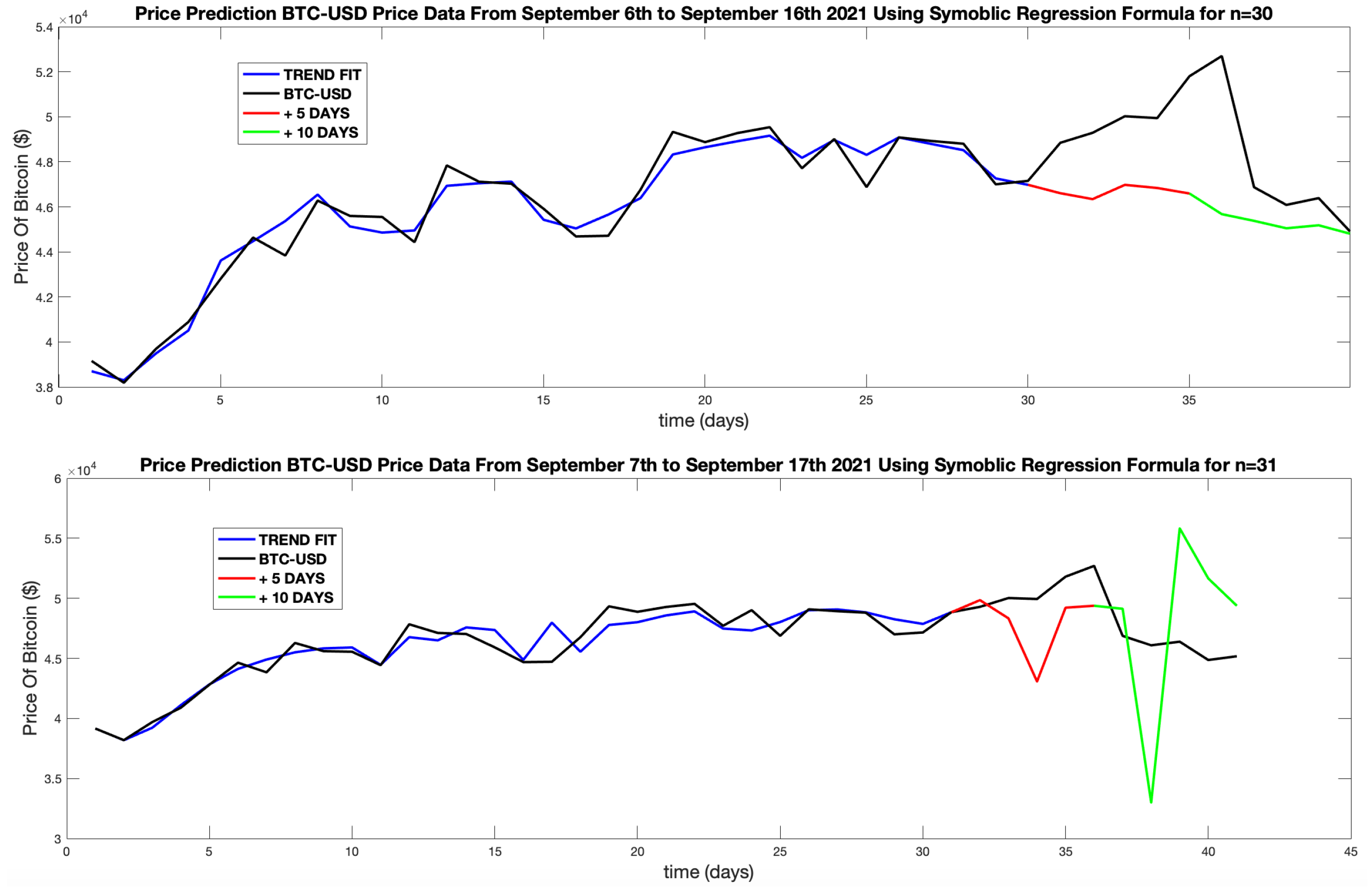

Figure 26 contains prediction plots for

(top) and

(bottom). The latter of which shows widely fluctuating prices and provides no confidence in it’s accuracy.

As a test,

Figure 27 shows the non-linear formula generated at September 7th (Day 34) using the preceding 31 data points within

and an additional 3 points from before the stable period began (i.e.

). This test goes against the ML hypothesis.

This output does provide credible guidance, indicating an exit of the long position on September 10th (Day 37) for

. Compared to the zero-crossing recommendation on September 20th, this new trade position increased profit by

or

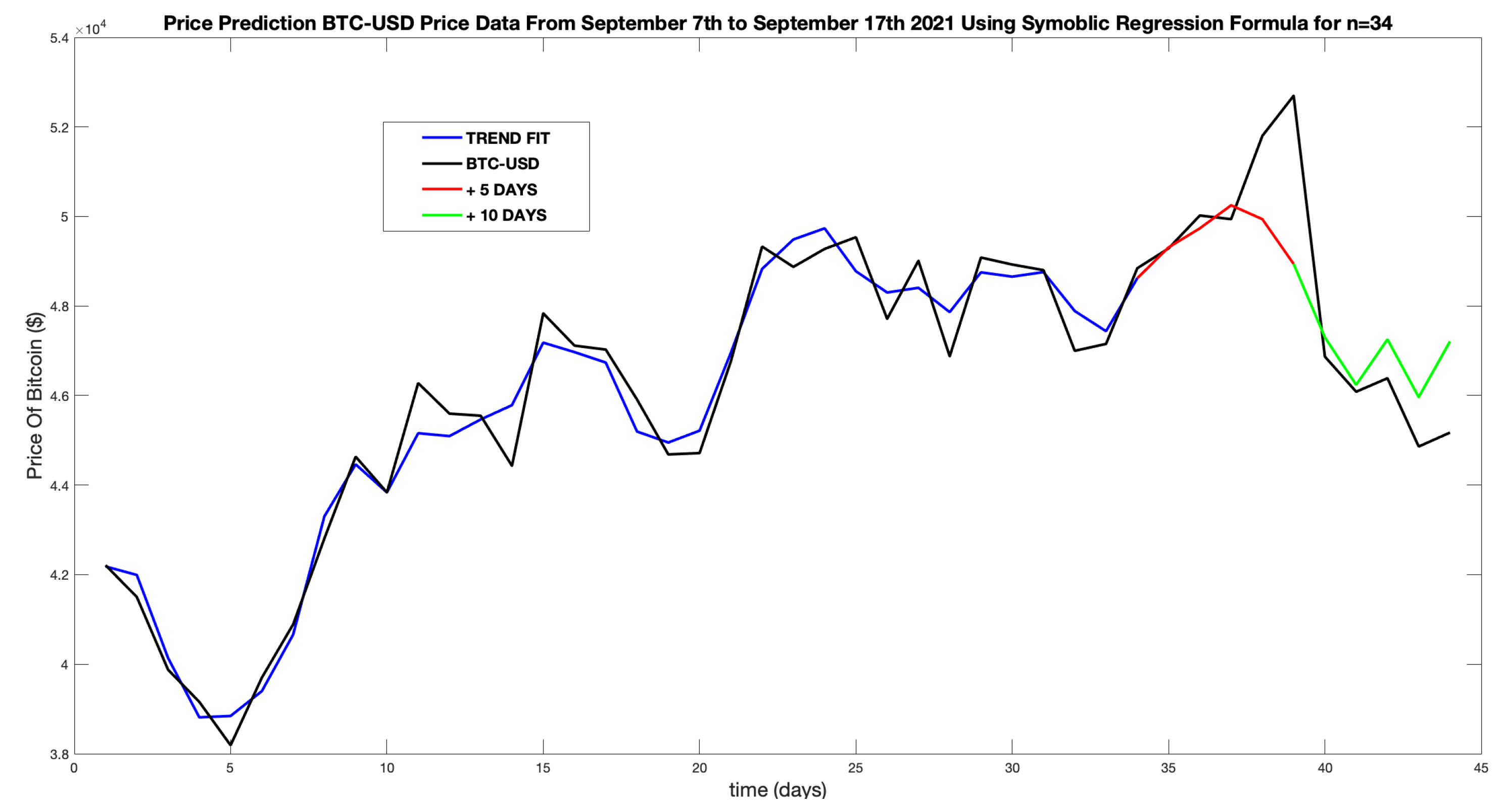

, a significant increase in profit. To examine this further,

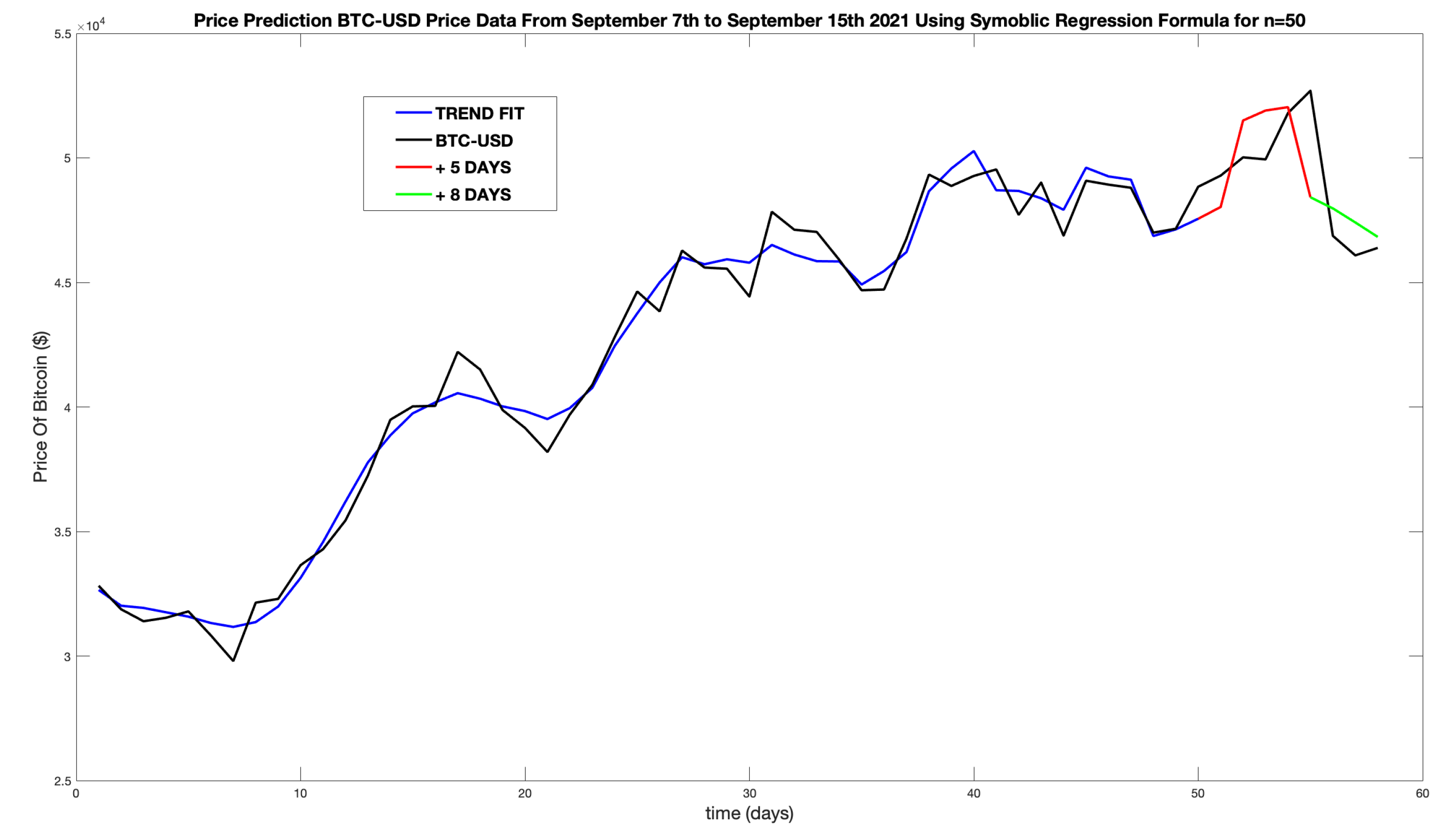

Figure 28 shows a formula generated for August 2nd to September 7th, now using 20 data points from outside the

(

).

This result is based on using the following equation:

giving a very accurate prediction. It correctly estimates the short price rise before the sharp fall. An indicated exit on September 11th at

increases profit by

or

. The interesting observation here is that more precise price estimations came from extending the `look-back’ window beyond the

. Due to the manual nature of the TuringBot, this process was only completed for the BTCUSD2021 time series and not for all time series.

6. Discussion

The analysis of both the cryptocurrencies considered in this research, has shown clear indications of non-normality (i.e non-Gaussian behaviour). This is a defining characteristic of a fractal stochastic field. The peaked and broader side bands of the PDF for these financial signals deviate from a Gaussian PDF model, violating a core principle of the EMH. Disregarding the assumption of an efficient cryptocurrency market allows various indicators to be utilised to determine the financial fields nature. All these indicators were calculated as linear functions associated with spectral decay of the signal which was obtained through linear regression of the log power spectral plot. However, this method can lead to inaccuracies due to the erratic nature of the log power spectrum. As seen in

Figure 29, the gradient of the log-log regression line could have a range of values.

In order to obtain an accurate value of

, precise calculations of the spectrum and optimum region for fitting the regression line are required, which in most cases is not available [

65]. As all of the indicators considered are linearly related, more precise methods of calculating their values are available, such as the `Higuchi method’ for determination of

and the algorithms for computing the Hurst exponent [

66,

67]. However, in the case of crypto-markets, the collection of indicators used showed such high deviations from normality that their inaccuracy would have made no difference to the conclusions in association with the application of a self-affine field model.

Each index showed a different aspect of deviation. The Hurst exponent (H) showed a level of anti-persistence not consistent with RWMs. The Levy index () indicated a peaked PDF, indicative of a Lévy distribution, not a Gaussian distribution. The value of the fractal dimension () showed that the field has a narrower spectrum consistent with a self-affine signal. The ACF showed clear signs of data correlation, long term market memory. This provided an overwhelming amount of evidence that the standard market hypothesis is not applicable and therefore the potential inaccuracy in the computation of can be ignored.

During backtesting and optimisation, a range of ideal values for the W, T parameters was alluded to. The need to reduce trading delay, whilst minimising the noise in the signal, proved to be dependent on the time scale of the time series, with larger filtering windows being required for the more detailed hourly data fields. Financial calculations had to be undertaken over small time windows relative to the length of data being analysed, whilst staying above the limit of 2. Unlike W, T values did not increase with an increase in scaling. Observing the positions, the location of the GOC can be acquired. This is related to the smallest range of W values for which T is minimised. This GOC was consistent, through all fields of the same currency and scale, leading to the guidelines for the parameter choice as follows: W - Smallest values for which noise is sufficiently removed; T - . Although this range, for the two parameters, did not always result in the most profitable trades, the high accuracy allowed high confidence in a profitable strategy. The fluctuation in ROI for neighbouring combinations can be explained by rapid micro-trends making an `ideal’ position recommendation impossible given the level of trading delay.

Another method to help overcome the trading delay is to redefine the conditions for which the position indicator produces a Kronecker delta. Currently, positions are only recommended when either or change polarity. However, if this was altered so that the Kronecker deltas were produced when a given threshold is passed, the system would react faster to changing trends. The implications of this are that price changes opposed to the current trend direction require less impact on the filter window to produce a Kronecker delta indicator.

The only down side to this change, is the increased risk due to parabolic metric flights caused by fast trend sweeps large enough to influence BVR/LVR results into recommending buy and sell positions in quick succession. However, looking at backtesting graphical outputs, it can be seen that a reduction in trading delay occurs more frequently. This change also depends on the metric used. The LVR produces a signal with a higher amplitude, giving more flexibility to choose a threshold range. Performances for both metrics were similar, as were returns in all backtests. As the metrics are derived from a different theoretical basis, one from a fractal model and the other from a chaotic model, their similar effectiveness further proves that cryptocurrency exchanges adhere to the FMH.

The self-affine behaviour of the cypto-markets under consideration allow for different time scales to be analysed. For example,

Figure 30 shows an extraction from the daily backtesting output for BTC-USD 2021-22 for Jan-Feb (left) and compares it with the same backtesting time period for hourly data.

The hourly data (right) shows a number of trades being recommended with a return over a period of overall loss in value. This is in stark contrast to the daily backtest, which showed no positions, therefore resulting in a loss. The most interesting comparison, is the opposite trade positions recommended for the last few data points, with daily data suggesting a purchase and hourly data suggesting a short market position.

The higher detail in the hourly data would be expected to produce more accurate positions. However, hourly data is particularly susceptible to micro-trends, requiring a large increase in the filtering window. This makes system outputs, based on hourly data, riskier; as evidenced from the reduced returns. Even though actual price changes over a month are less than over a year, the relative movement over the time period as a percentage is directly comparable over any scale.

Coupled with an increased number of trades per unit time, which has an effect due to the fees charged by the trading platform, the hourly trading system has it’s limitations. A combination of both strategies, whereby long term trend analysis positions are complimented by short term data, will increase the likelihood that the most profitable position can be achieved.

The application of ML to aid optimum trade executions provides price estimations that were highly inaccurate when using `look-back’ data contained within the . A range of non-linear equations, of increasing length, were created for sequential time steps within the FTS, each of which failed to predict the impending change of a trend, suggesting that increasing the window length within the has no effect on accuracy. However, accurate price estimations were produced when including a range of `unstable’ data points that proceed the window. During testing of look-back windows, that included values outside of the , it was observed that longer window lengths produce more precise results that correctly predict the magnitude and direction of the next 5-8 days within an accuracy of . For example, using a window consisting of 50 data points (), including 20 unstable values, increased the profit for a single trade by .

On re-evaluation of the approach, it becomes clear that any non-linear function based on a window of `stable’ data will only continue to display this trend when evolved forward in time. This is clearly a fundamental flaw, as, by definition, this approach will not achieve the goal of predicting a future change in trend. Extending the window beyond the creates an equation that accounts for both the low volatility trend and the high volatility movements, therefore giving a more accurate representation of the data and a better basis for future estimation. Tests on a window length of produced vastly improved results, suggesting that increasing the window length is not the primary way to improve estimations. Nevertheless, increases did improve prediction accuracy by . Thus, it can be concluded that an increase in the window length, using stable and unstable data, increases future price prediction accuracy.

Considering that the BVR and LVR are both calculated using their own rolling windows of length T, this extension should be at least T steps beyond the .

The manual nature of the TuringBot results in highly inefficient calculations. The lack of SR integration within the system is a significant flaw, if ML is to be recommended as a strategy to reduce trading delay. A proprietary SR algorithm or existing library will greatly increase usability . However, this is outside the scope of this work. Extensive manual testing of the ML method was not able to be completed over the time frame available for this work. A beneficial evolution would be an implementation in Python where large ML and evolutionary computing libraries are currently available. However, more recently, TuringBot.com has released an API for their software, allowing remote access to the SR algorithm from within the system code. This provides another approach to increasing efficiency.

During code development, using truncation to preserve data length and vectorisation to improve performance proved vital to conducting an analysis, the slow nature of the original functions making the program non-viable for continued and efficient trading. The creation of the function made the system universal, where any .csv database of financial data could be uploaded and converted into a compatible time series.

Optimisation of the code resulted in a system that could generate an output in seconds. This was a significant improvement, making its use in conjunction with a live trading system viable. This decrease in computational time allows a continuous live data stream to be used, where fast tick times of a few seconds are implementable. However, this level of data requires a marked increase in filtering or new methods of creating price data. Opening daily prices can be replaced by an average of the underlying prices of the minimum time step.

7. Conclusions: Summary, Discussion and Future Directions

The fundamental analysis of BTC and ETH crypto-markets proved to be consistent with previous research. Even though the majority of these concluded that BTC was developing into a more mature and efficient market, the analysis in this paper shows that it is still far from an efficient market. Since there is no previous research on price and trend prediction for crypto-markets using similar approaches in the available literature, no comparison can be conducted.

Analysis indicated that the data does not fit a normal distributional model. For Bitcoin, the Hurst exponent was calculated to be indicating anti-persistence and short term dependence. The Lévy Index was recorded at and a Fractal Dimension of . Moreover, long term market memory was observed from the auto-correlation functions. These results prove that cryptocurrencies are not efficient markets and a fractal model is relevant. In this context, the self-affine properties were confirmed by observing similar PDFs over scaled time series, results that are reflected in Ethereum markets as well.

7.1. Summary

Based on the principles of the FMH, two basic indicators were derived from different theoretical backgrounds, both being scaled by the volatility to produce a pair of trend analysis metrics. The success of both metric signals, when examining their zero-crossings, are an indication of a change in trend. Positive returns were found for all time series analysed even in bear dominant time periods.

Analysis of parameter sweeps, gave a basis for choosing optimum parameters values. Filtering window sizes need to be minimised to reduce trading delays whilst removing noise for accurate system outputs. For the range of filter widths (W), the width of the window (T) is be chosen to be . This rule for choosing parameters was shown to give high accuracy and returns. Short time steps create time series with high levels of noise making trend prediction less accurate and more susceptible to micro-trends causing position indications that result in a revenue loss. As a result of this, it is recommended that a combination of long and short format analysis is undertaken. This is where the short term results are used to identify the most profitable time to make a position as recommended by the associated long term analysis.

Any adoption of ML to predict future price fluctuations and thereby reduce trading delay has been shown to be highly inaccurate unless the window of data points used extends back beyond the by a minimum of T steps. Longer windows containing more data points were shown to increase accuracy. With regard to general use, the TuringBot did not provide an efficient method of implementing SR. Further improvements in the system should therefore focus on a full integration.

The analysis undertaken has shown that this approach outperforms `Buy & Hold’ strategies for all the time series considered. It also outperforms benchmark returns set by stock market indices. Given the overall performance of cryptocurrencies in the last five years, this is not surprising. However, profitable returns were observed in all bear dominant time series. Any further research should explore scale combination strategies to increase profitability. A natural evolution is the development of an integrated SR algorithm. A final area for further research may be to determine whether more cryptocurrencies are fractal in nature, and if any price correlations exist between them.

7.2. Discussion

The aim of this publication has been to provide readers with a detailed background to the algorithms that have been developed. Apart from the introductory materials given in

Section 1 and

Section 2, the results given in this paper are, to the best of the authors knowledge, new and original, especially in terms of their application, the numerical results presented, and more specifically, the type of data that has been investigated and the results thereof., i.e., Cryptocurrencies. In this context, an important feature of the paper is the Matlab code used in the investigation, which has been provided to allow readers to re-work the results and develop the approach further. The authors consider this to be an important component of the paper, especially for readers who would be interest to implement the algorithms in the commodities markets etc.

In this context, it is worth noting that TuringBot is just one of several emerging applications in the field of genetic programming that can be used to evolve nonlinear functions for simulating real noise. Among these are various Python-based solutions that enable the development of a fully integrated Python program, eliminating the need to rely on an external application like TuringBot. One such example is

gplearn, a Python library that implements genetic programming with an Application Programming Interface inspired by and compatible with scikit-learn [

68].

7.3. Future Directions

The approach considered in this work is algorithmic, in the sense that long term trends and short term price values are based on a set of quantifiable algorithms and their optimisation. In the former case, these algorithms and based on functions that compute metrics associated with the Fractal Market Hypothesis. in the latter case, the algorithms are based on a nonlinear functions that are repeatedly generated using symbolic regression. In this sense, the methods presented in this work couple conventional time series modelling with machine learning. This approach is in contrast to the use of deep learning models which have the ability to capture relationships between features in time series data, for example, and long-term dependencies in data [

69]. In this context, deep learning models have the ability to improve the accuracy of the results. However, the price that is paid for this is the `volume’ of training data that is required to operate a deep learning model effectively. Thus, a specific area of future research is to undertaken a comparison between the approach considered in this paper and the use of deep time series forecasting models, using data that is initially, specific to Cryptocurrency trading and other commodities.

Figure 1.

Daily opening prices for BTC-USD from 12/02/2016 - 12/02/2022.

Figure 1.

Daily opening prices for BTC-USD from 12/02/2016 - 12/02/2022.

Figure 2.

Frequency histogram for BTC-USD opening prices (2016-2022).

Figure 2.

Frequency histogram for BTC-USD opening prices (2016-2022).

Figure 3.

Frequency histogram of log price changes for BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 3.

Frequency histogram of log price changes for BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 4.

Actual price changes for opening daily BTC-USD prices (2016-2022).

Figure 4.

Actual price changes for opening daily BTC-USD prices (2016-2022).

Figure 5.

Log price change probability density function for opening daily BTC-USD prices (2016-2022) Vs. standard gaussian distribution.

Figure 5.

Log price change probability density function for opening daily BTC-USD prices (2016-2022) Vs. standard gaussian distribution.

Figure 6.

Power spectrum of absolute log price change of the BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 6.

Power spectrum of absolute log price change of the BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 7.

Auto-correlation function output for absolute log price changes of the BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 7.

Auto-correlation function output for absolute log price changes of the BTC-USD (2016-2022).

Figure 8.

Example graphical output of the backtesting function displaying - in green, in blue, filtered price data in red and the unfiltered price data in black. The right hand plot shows the unfiltered data on its original scale for comparison.

Figure 8.

Example graphical output of the backtesting function displaying - in green, in blue, filtered price data in red and the unfiltered price data in black. The right hand plot shows the unfiltered data on its original scale for comparison.

Figure 9.

Parameter optimisation for BTC-USD 2020-21 where x, z axis are W, T parameter combinations and the y axis is the evaluator output accuracy.

Figure 9.

Parameter optimisation for BTC-USD 2020-21 where x, z axis are W, T parameter combinations and the y axis is the evaluator output accuracy.

Figure 10.

Real BTC-USD prices compared to TuringBot trend fit equation for August 5th 2021 to September 10th 2021.

Figure 10.

Real BTC-USD prices compared to TuringBot trend fit equation for August 5th 2021 to September 10th 2021.

Figure 11.

Mesh plot for parameter optimisation of BTCUSD 2021-22.

Figure 11.

Mesh plot for parameter optimisation of BTCUSD 2021-22.

Figure 12.

Comparison Of backtesting metric signals for financial calculation windows, (red) (blue) with normalised price signal (black).

Figure 12.

Comparison Of backtesting metric signals for financial calculation windows, (red) (blue) with normalised price signal (black).

Figure 13.

Mesh plot of Return On Investment (ROIs) For BTC-USD 2021-22 optimum parameter positions where x, z axis represents W, T values respectively and y axis represents the % ROI.

Figure 13.

Mesh plot of Return On Investment (ROIs) For BTC-USD 2021-22 optimum parameter positions where x, z axis represents W, T values respectively and y axis represents the % ROI.

Figure 14.

Mesh plot of percentage Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTCUSD 2021-22 including all W, T parameter combinations.

Figure 14.

Mesh plot of percentage Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTCUSD 2021-22 including all W, T parameter combinations.

Figure 15.

`Top Down’ view of optimised parameter mesh plot showing only W, T combinations that achieve 100% accuracy for BTC-USD 2021-22.

Figure 15.

`Top Down’ view of optimised parameter mesh plot showing only W, T combinations that achieve 100% accuracy for BTC-USD 2021-22.

Figure 16.

Optimisation graphical output depicting `Top Down’ view of optimum parameter combinations (left) and Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTS-USD 2020-21.

Figure 16.

Optimisation graphical output depicting `Top Down’ view of optimum parameter combinations (left) and Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTS-USD 2020-21.

Figure 17.

Backtesting for BTCUSD 2021-22 with parameters , .

Figure 17.

Backtesting for BTCUSD 2021-22 with parameters , .

Figure 18.

20 days of hourly opening price data For BTC-USD.

Figure 18.

20 days of hourly opening price data For BTC-USD.

Figure 19.

Parameter optimisation mesh for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 19.

Parameter optimisation mesh for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 20.

`Top Down’ view of optimised parameter mesh plot showing only W, T combinations that achieve 100% accuracy for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 20.

`Top Down’ view of optimised parameter mesh plot showing only W, T combinations that achieve 100% accuracy for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 21.

Mesh plot of percentage Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 21.

Mesh plot of percentage Return On Investment (ROIs) for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 22.

Backtesting output comparison of two invalid combinations - (left) and (right).

Figure 22.

Backtesting output comparison of two invalid combinations - (left) and (right).

Figure 23.

Backtesting for BTCUSD Jan-Feb 2022 with parameters .

Figure 23.

Backtesting for BTCUSD Jan-Feb 2022 with parameters .

Figure 24.

Backtesting for BTCUSD 2021-22 using LVR with parameters .

Figure 24.

Backtesting for BTCUSD 2021-22 using LVR with parameters .

Figure 25.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 21st to Sep 10th with price estimation from Sep 11th to Sep 20th (+10 days).

Figure 25.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 21st to Sep 10th with price estimation from Sep 11th to Sep 20th (+10 days).

Figure 26.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD for look-back window lengths of (top) and (bottom).

Figure 26.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD for look-back window lengths of (top) and (bottom).

Figure 27.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 18th to Sep 7th with price estimation from Sep 7th to Sep 17th (+10 days).

Figure 27.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 18th to Sep 7th with price estimation from Sep 7th to Sep 17th (+10 days).

Figure 28.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 2nd to Sep 7th with price estimation from Sep 7th to Sep 15th (+8 days).

Figure 28.

Price prediction using symbolic regression for BTC-USD Aug 2nd to Sep 7th with price estimation from Sep 7th to Sep 15th (+8 days).

Figure 29.

Log-Log power spectrum for BTC-USD Feb 2016-2022.

Figure 29.

Log-Log power spectrum for BTC-USD Feb 2016-2022.

Figure 30.

Comparison between daily and hourly system outputs for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Figure 30.

Comparison between daily and hourly system outputs for BTC-USD Jan-Feb 2022.

Table 1.

Comparison of BTC-USD and ETH-USD fractal indexes for both daily and hourly time series (2016-2022).

Table 1.

Comparison of BTC-USD and ETH-USD fractal indexes for both daily and hourly time series (2016-2022).

| Index |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

| |

Daily |

Daily |

Hourly |

Hourly |

| Spectral Decay () |

0.8185 |

0.8232 |

0.8714 |

0.8895 |

| Hurst Exponent (H) |

0.3185 |

0.3232 |

0.3732 |

0.3895 |

| Fractal Dimension () |

1.6815 |

1.6768 |

1.6286 |

1.6105 |

| Levy Index () |

1.2218 |

1.2142 |

1.1452 |

1.1242 |

Table 2.

List of financial time series.

Table 2.

List of financial time series.

| Name |

Start |

End |

Time Step |

Data Points |

| BTCUSD2021 |

12-02-2021 |

12-02-2022 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD2020 |

12-02-2020 |

12-02-2021 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD2019 |

12-02-2019 |

12-02-2020 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD2018 |

12-02-2018 |

12-02-2019 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD2017 |

12-02-2017 |

12-02-2018 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD2016 |

12-02-2016 |

12-02-2017 |

24 |

365 |

| BTCUSD_janfeb |

12-02-2016 |

12-02-2017 |

1 |

744 |

| BTCUSD_decjan |

12-02-2016 |

12-02-2017 |

1 |

744 |

| BTCUSD_novdec |

12-02-2016 |

12-02-2017 |

1 |

720 |

Table 3.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using Beta-to-Volatility ratio.

Table 3.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using Beta-to-Volatility ratio.

| Year |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

| |

W |

T |

Evaluator (%) |

ROI (%) |

W |

T |

Evaluator (%) |

ROI (%) |

| 2016-17 |

33 |

8 |

100 |

194 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| 2017-18 |

23 |

8 |

100 |

2,487 |

17 |

3 |

100 |

11,093 |

| 2018-19 |

20 |

3 |

87.5 |

38.5 |

21 |

3 |

100 |

76 |

| 2019-20 |

43 |

4 |

100 |

267 |

17 |

3 |

94.4 |

108 |

| 2020-21 |

23 |

5 |

100 |

464 |

15 |

5 |

100 |

1,207 |

| 2021-22 |

26 |

6 |

100 |

69 |

27 |

6 |

100 |

264 |

Table 4.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for hourly financial time series using Beta-to-Volatility ratio.

Table 4.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for hourly financial time series using Beta-to-Volatility ratio.

| Year |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

| |

W |

T |

Evaluator (%) |

ROI (%) |

W |

T |

Evaluator (%) |

ROI (%) |

| Nov-Dec |

44 |

10 |

100 |

11.8 |

50 |

7 |

100 |

27.2 |

| Dec-Jan |

90 |

7 |

83.3 |

20 |

73 |

9 |

100 |

15.5 |

| Jan-Feb |

91 |

8 |

100 |

31.1 |

85 |

10 |

100 |

51.1 |

Table 5.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using the Lyapunov-to-Volatility (LVR) ratio.

Table 5.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using the Lyapunov-to-Volatility (LVR) ratio.

| Year |

BTC-USD (%) |

ETH-USD (%) |

| 2016-17 |

137 |

NA |

| 2017-18 |

2,248 |

10,425 |

| 2018-19 |

40.6 |

62.7 |

| 2019-20 |

248 |

119.9 |

| 2020-21 |

456 |

1,158 |

| 2021-22 |

59.7 |

248 |

Table 6.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using both LVR and BVR indicators compared to Buy & Hold strategy (B&H).

Table 6.

Percentage return on investment of BTC-USD and ETH-USD for daily financial time series using both LVR and BVR indicators compared to Buy & Hold strategy (B&H).

| Year |

BTC-USD |

ETH-USD |

| |

ROI -

|

ROI -

|

B&H (%) |

ROI -

|

ROI -

|

B&H (%) |

| 2016-17 |

137 |

194 |

162 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| 2017-18 |

2,248 |

2,487 |

700 |

10,425 |

11,093 |

7,021 |

| 2018-19 |

40.6 |

38.5 |

-60 |

62.7 |

76 |

-86.2 |

| 2019-20 |

248 |

267 |

185 |

119.9 |

108 |

95.1 |

| 2020-21 |

456 |

465 |

369 |

1,158 |

1,207 |

565 |

| 2021-22 |

59.7 |

69 |

-10.7 |

248 |

264 |

58.7 |