Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

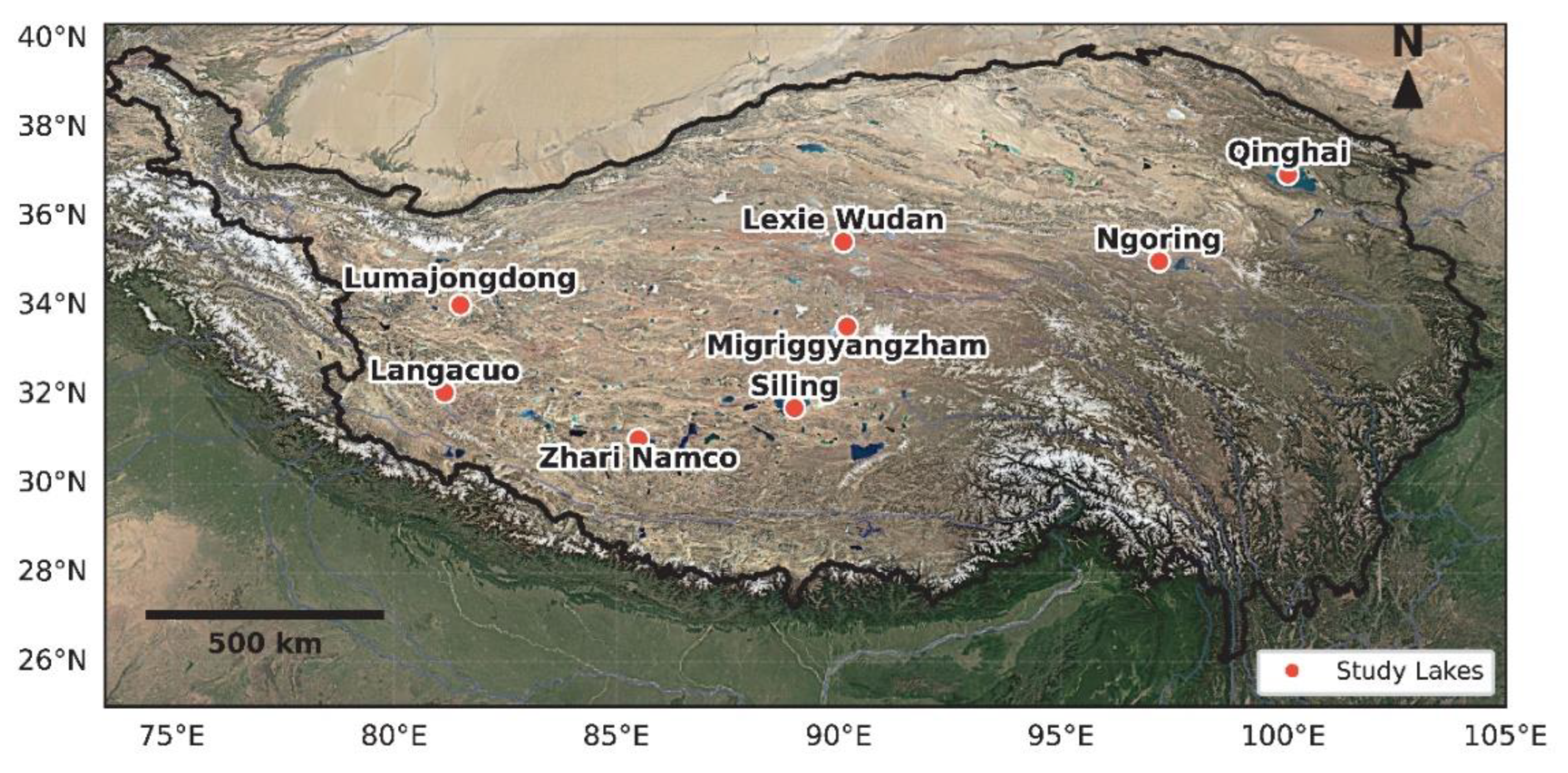

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.2. Deep Learning Framework

2.3. Model Validation and Interpretation

2.4. Mechanistic Attribution of Hydrological Trends Using Explainable AI

2.5. Scenario Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of CMIP6 Model Performance

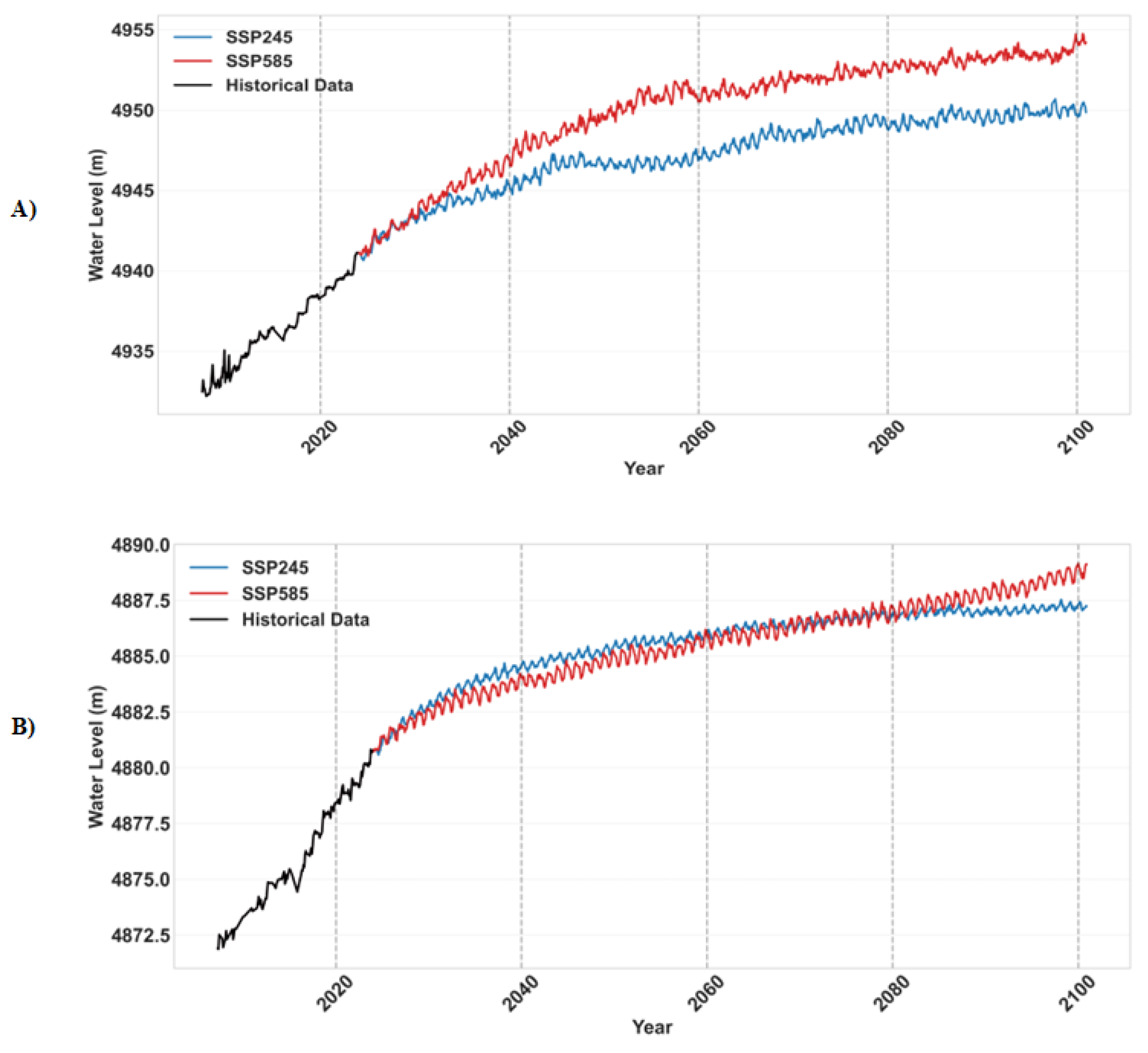

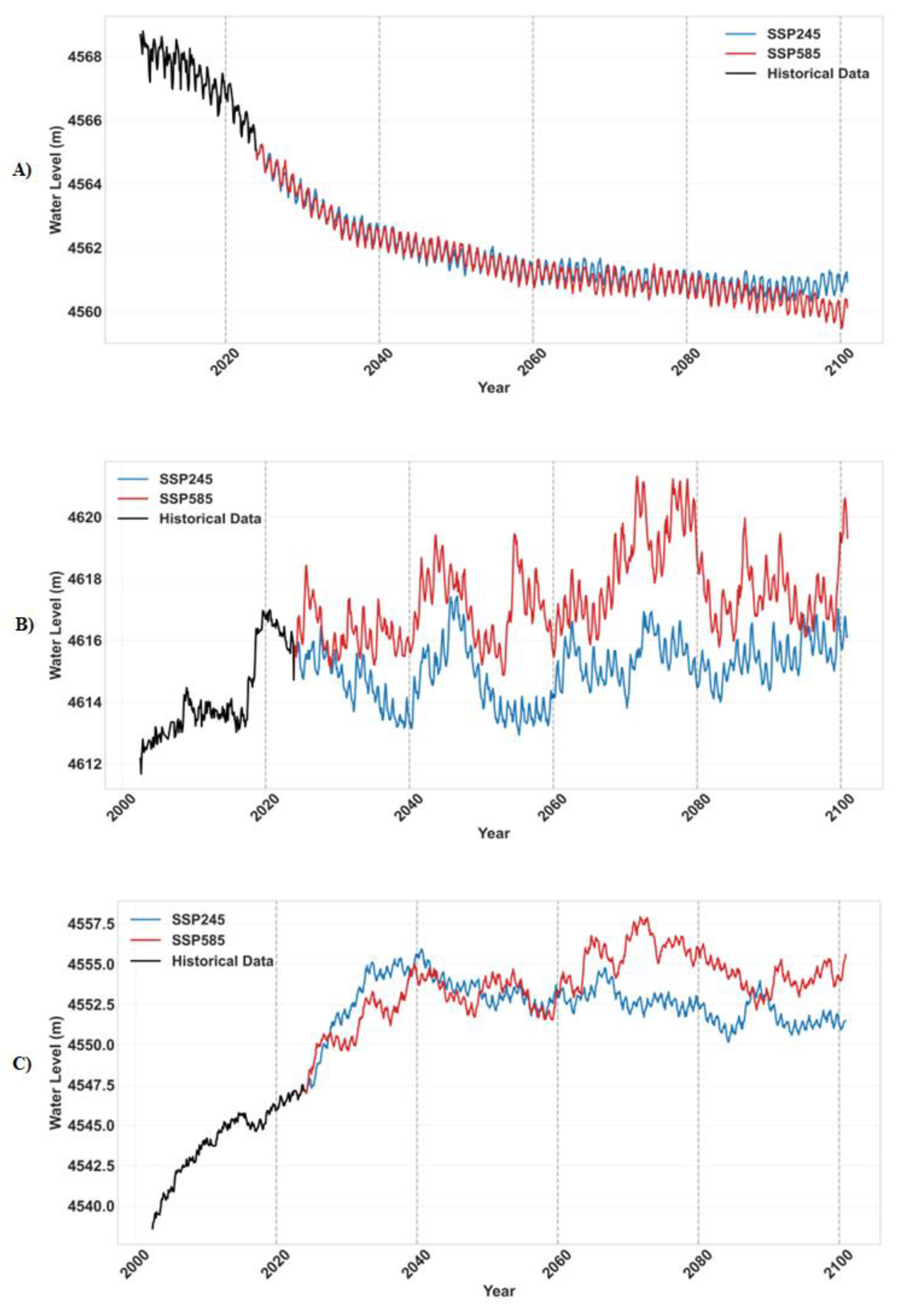

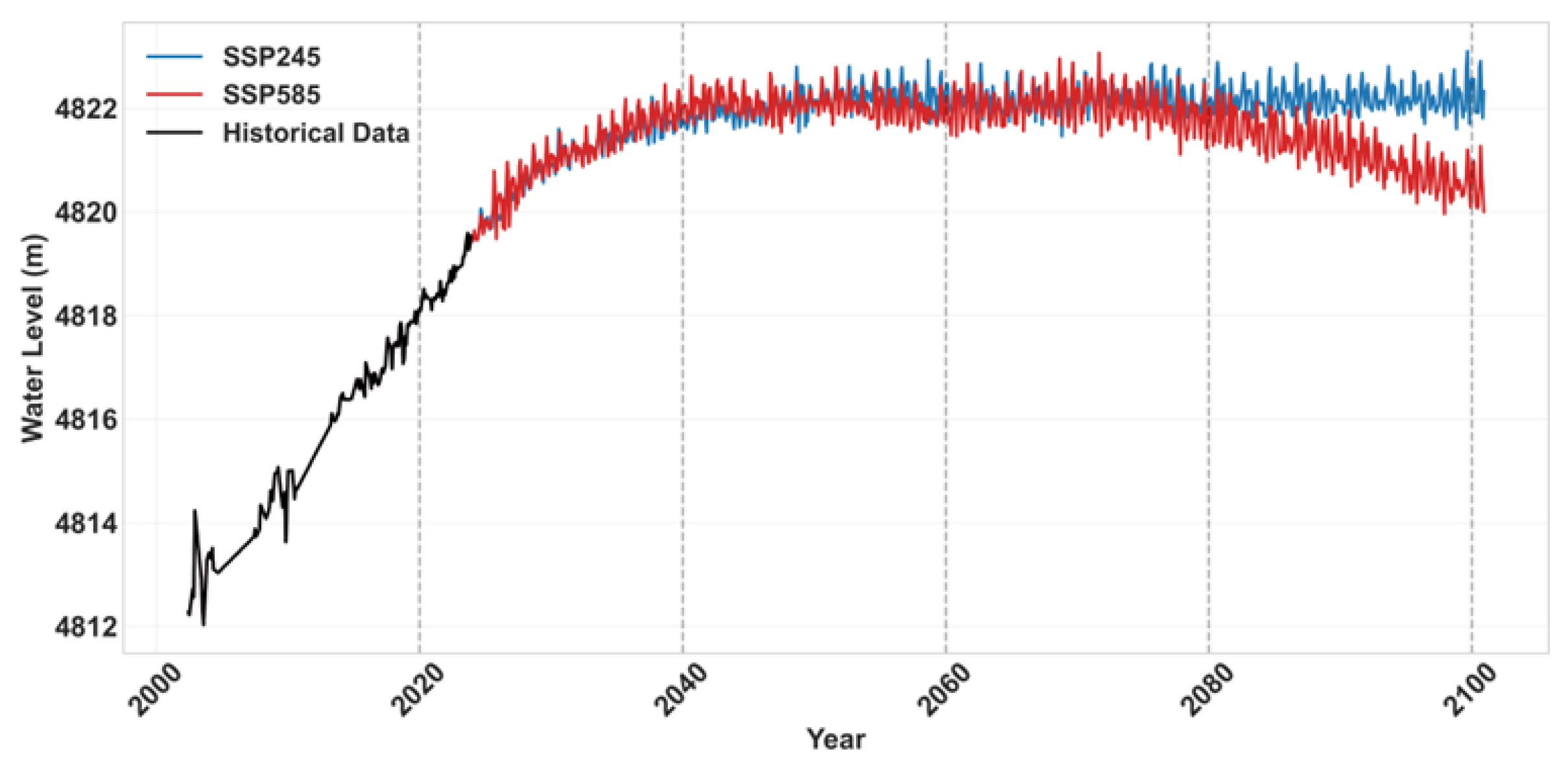

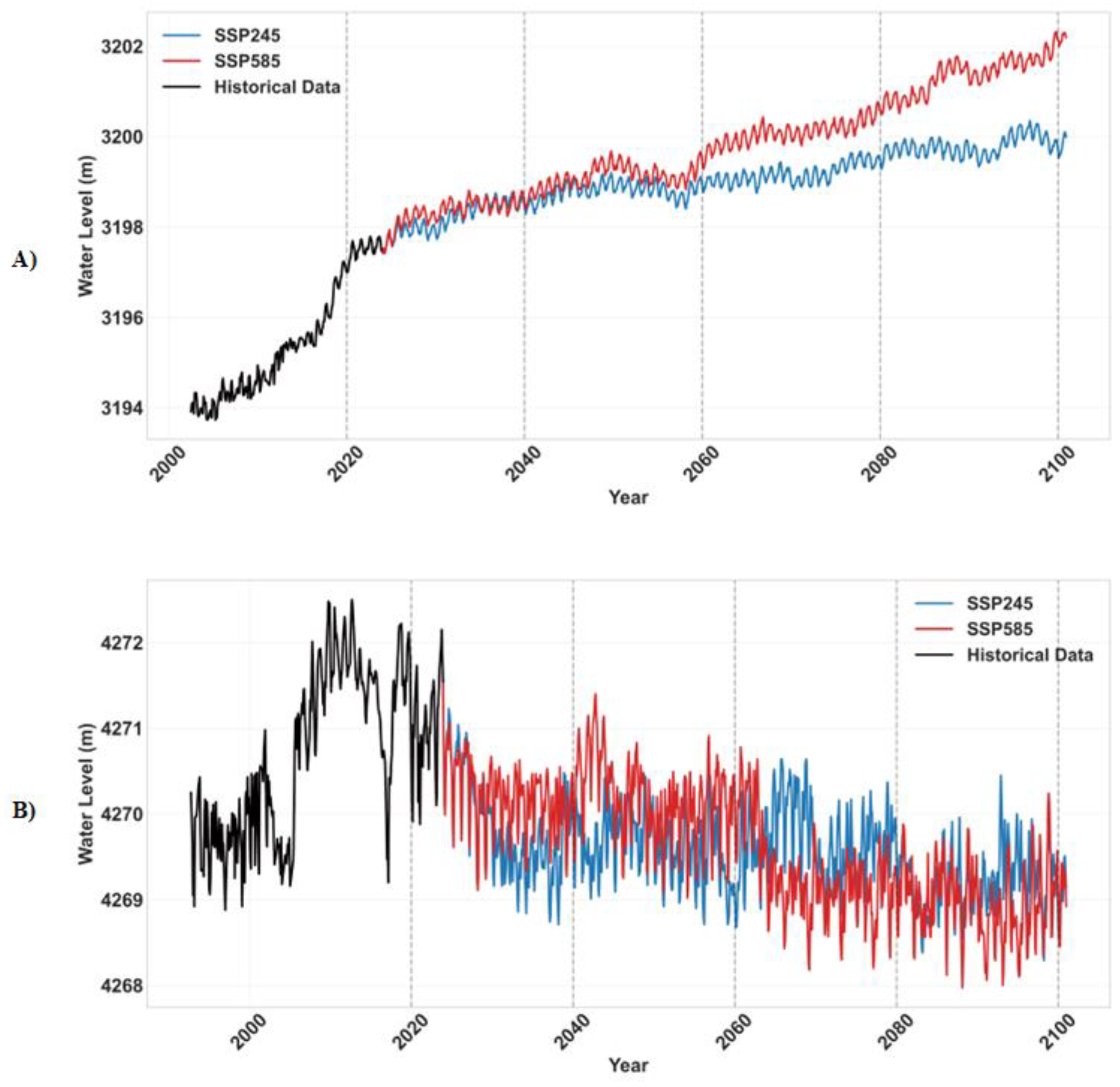

3.2. Hydrological Projections Under Climate Scenarios

4. Discussion

- Divergent Hydrological Regimes and Climatic Drivers

- (a) Northern Glacier-Fed Lakes

- (b) Southern Evaporation-Dominated Lakes

- (c) Western Transitional Lakes

- (d) Eastern Morphometry-Controlled Lakes

4.1. Implications for Ecosystems and Water Security

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Q. Land–Climate Interaction over the Tibetan Plateau. 2018.

- Pastorino, P.; Elia, A.C.; Pizzul, E.; Bertoli, M.; Renzi, M.; Prearo, M. The old and the new on threats to high-mountain lakes in the Alps: A comprehensive examination with future research directions. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Kraemer, B.M.; Lenters, J.D.; Merchant, C.J.; O’rEilly, C.M.; Sharma, S. Global lake responses to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kurbaniyazov, A.; Kirillin, G. Changing Pattern of Water Level Trends in Eurasian Endorheic Lakes as a Response to the Recent Climate Variability. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Mengmeng, W.; Tao, Z.; Wenfeng, C. Progress in Remote Sensing Monitoring of Lake Area, Water Level, and Volume Changes on the Tibetan Plateau. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2022, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Shum, C.K.; Yi, S.; Yang, K.; Xie, H.; Feng, W.; Bolch, T.; Wang, L.; Behrangi, A.; et al. Lake volume and groundwater storage variations in Tibetan Plateau's endorheic basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5550–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Change in Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau Projected by Weighted CMIP6 Models. Adv. Atmospheric Sci. 2022, 39, 1133–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ye, A.; Wang, Y. Enhanced Spatial Dry–Wet Contrast in the Future of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Hydrological Processes 2025, 39, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; You, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Kang, S.; Zhai, P. Integrated warm-wet trends over the Tibetan Plateau in recent decades. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancamaria, S.; Frappart, F.; Leleu, A.-S.; Marieu, V.; Blumstein, D.; Desjonquères, J.-D.; Boy, F.; Sottolichio, A.; Valle-Levinson, A. Satellite radar altimetry water elevations performance over a 200 m wide river: Evaluation over the Garonne River. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 59, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Nielsen, K.; Andersen, O.B.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Monitoring recent lake level variations on the Tibetan Plateau using CryoSat-2 SARIn mode data. J. Hydrol. 2017, 544, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xie, H.; Duan, S.; Tian, M.; Yi, D. Water level variation of Lake Qinghai from satellite and in situ measurements under climate change. J. Appl. Remote. Sens. 2011, 5, 053532–053532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Huang, B.; Ke, L.; Richards, K.S. Seasonal and abrupt changes in the water level of closed lakes on the Tibetan Plateau and implications for climate impacts. J. Hydrol. 2014, 514, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Duan, Z. Monitoring Spatial-Temporal Variations of Lake Level in Western China Using ICESat-1 and CryoSat-2 Satellite Altimetry. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Zhang, W. High Altitude Hydrology: The Impacts of Climate Change on Tibetan Plateau Water Levels Using Satellite Altimetry and ERA5 Data. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Y.; Yang, S. Evaluation of CMIP6 for historical temperature and precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau and its comparison with CMIP5. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2020, 11, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Li, C.; Tian, F. Evaluation of Temperature and Precipitation Simulations in CMIP6 Models Over the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, A.L.; Brunner, L.; Lorenz, R.; Humphrey, V.; Knutti, R. Climate model Selection by Independence, Performance, and Spread (ClimSIPS v1.0.1) for regional applications. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 4715–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv:1705.07874 2017.

- Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-915788-9. [Google Scholar]

- Linking Global to Regional Climate Change. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-915788-9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, G.; Woolway, R.I.; Yang, K.; Wada, Y.; Wang, J.; Crétaux, J.-F. Widespread societal and ecological impacts from projected Tibetan Plateau lake expansion. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-J.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.-F.; Wu, X.-C.; Wang, P.; Lin, H.; Zhang, G.-H.; Miao, C.-Y. Evapotranspiration and its dominant controls along an elevation gradient in the Qinghai Lake watershed, northeast Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Luo, Z.; Nazli, S.; Shi, L. Hydrologic response and prediction of future water level changes in Qinghai Lake of Tibet Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, X.; Pi, X.; Xu, W.; Woolway, R.I. Global lakes are warming slower than surface air temperature due to accelerated evaporation. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.-J.; He, J.-S.; Yang, R.-H.; Wu, H.-J.; Wang, X.-L.; Jiao, L.; Tang, Z.; Yao, Y.-J. Range shifts in response to climate change of Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a fungus endemic to the Tibetan Plateau. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Teng, H.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, D.; Shi, Z. Future Habitat Shifts and Economic Implications for Ophiocordyceps sinensis Under Climate Change. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lake | Variable | RMSE Reduction (%) | Extreme Event Improvement (95th %ile, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexie Wudan | Runoff | 11.4% | 90.3% |

| Precipitation | 17.7% | 97% | |

| Temperature | 34.6% | 90.6% | |

| Evaporation | 38.0% | 98.30% | |

| Lumajang Dong | Runoff | 47.89% | 88.5% |

| Precipitation | 13.6% | 64.5% | |

| Temperature | 26.94% | 66.7% | |

| Evaporation | 0.81% | 81.8% | |

| Zhari Namco | Precipitation | 30.5% | 96.5 |

| temperature | 26.6% | 95.2% | |

| evaporation | 19.0% | 98.6% | |

| Runoff | 17.1% | 85.9% | |

| Langacuo | Precipitation | 10.3% | 87.5% |

| temperature | 19.6% | 74.5% | |

| evaporation | 14.3% | 11.2% | |

| Runoff | 20.8% | 99.3% | |

| Ngoring | precipitation | 4.8% | 79.2% |

| temperature | 12.9% | 98.8% | |

| evaporation | 13.4% | 98.3% | |

| Runoff | 1.1% | 93.4% | |

| Siling | precipitation | 49.0% | 94.8% |

| temperature | 30.4% | 96.3% | |

| evaporation | 43.0% | 100.0% | |

| Runoff | 0.6% | 78.9% | |

| Qinghai | precipitation | 7.1% | 96.2% |

| temperature | 47.2% | 91.0% | |

| evaporation | 2.6% | 98.9% | |

| Runoff | 19.7% | 96.2% | |

| Migriggyangzham | precipitation | 15.2% | 84.3% |

| temperature | 6.6% | 89.3% | |

| evaporation | 1.8% | 100.0% | |

| Runoff | 3.8% | 94.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).