Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Altimetry Data Acquisition

2.3. DAHITI and Hydroweb Data:

2.4. ERA5 Data Integration:

2.5. Fundamentals of Satellite Radar Altimetry and Subwaveform Retracking

2.6. Fitting the Model and Outlier Rejection

2.7. Validation Approach

2.8. Bias Correction of ERA5 Data

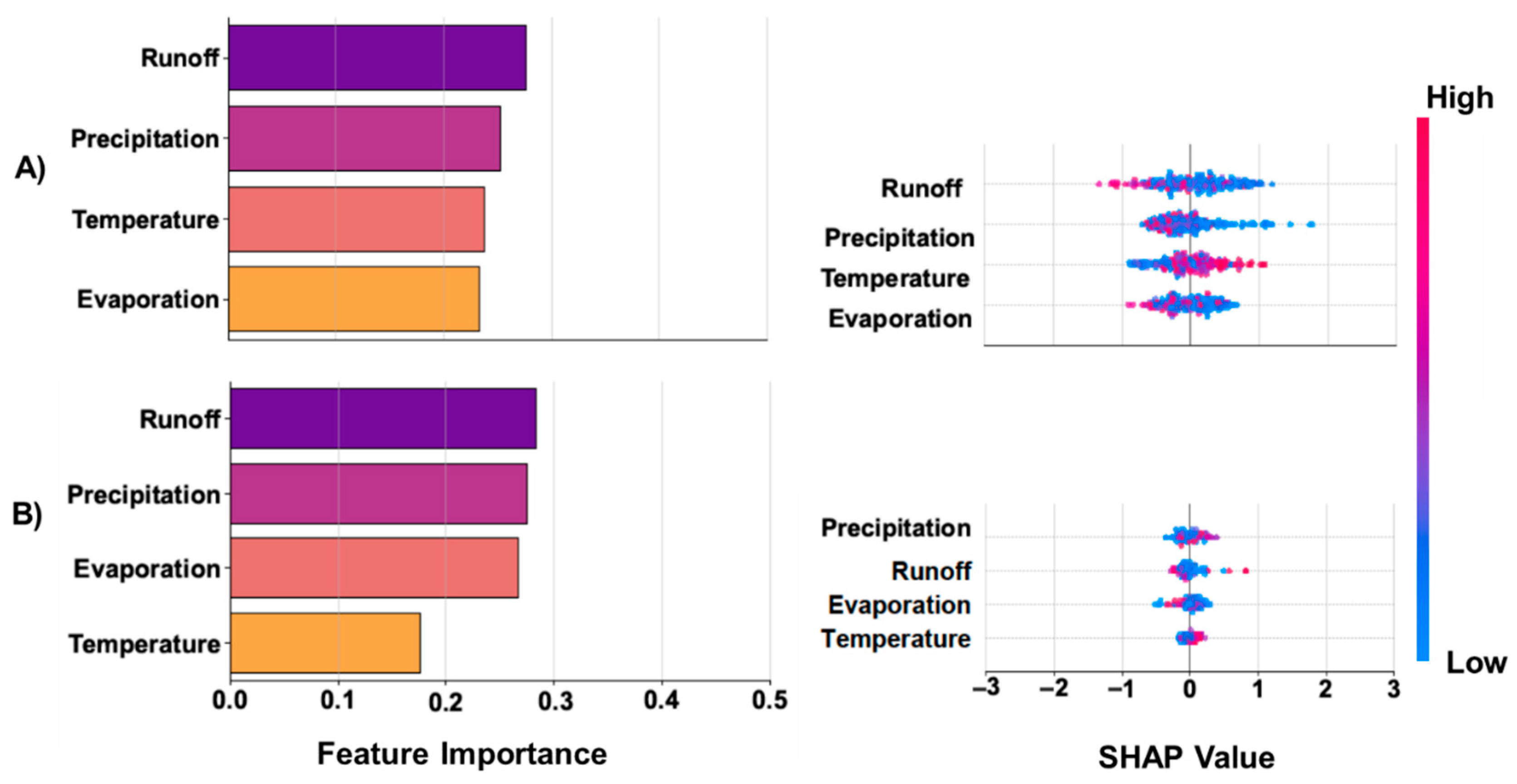

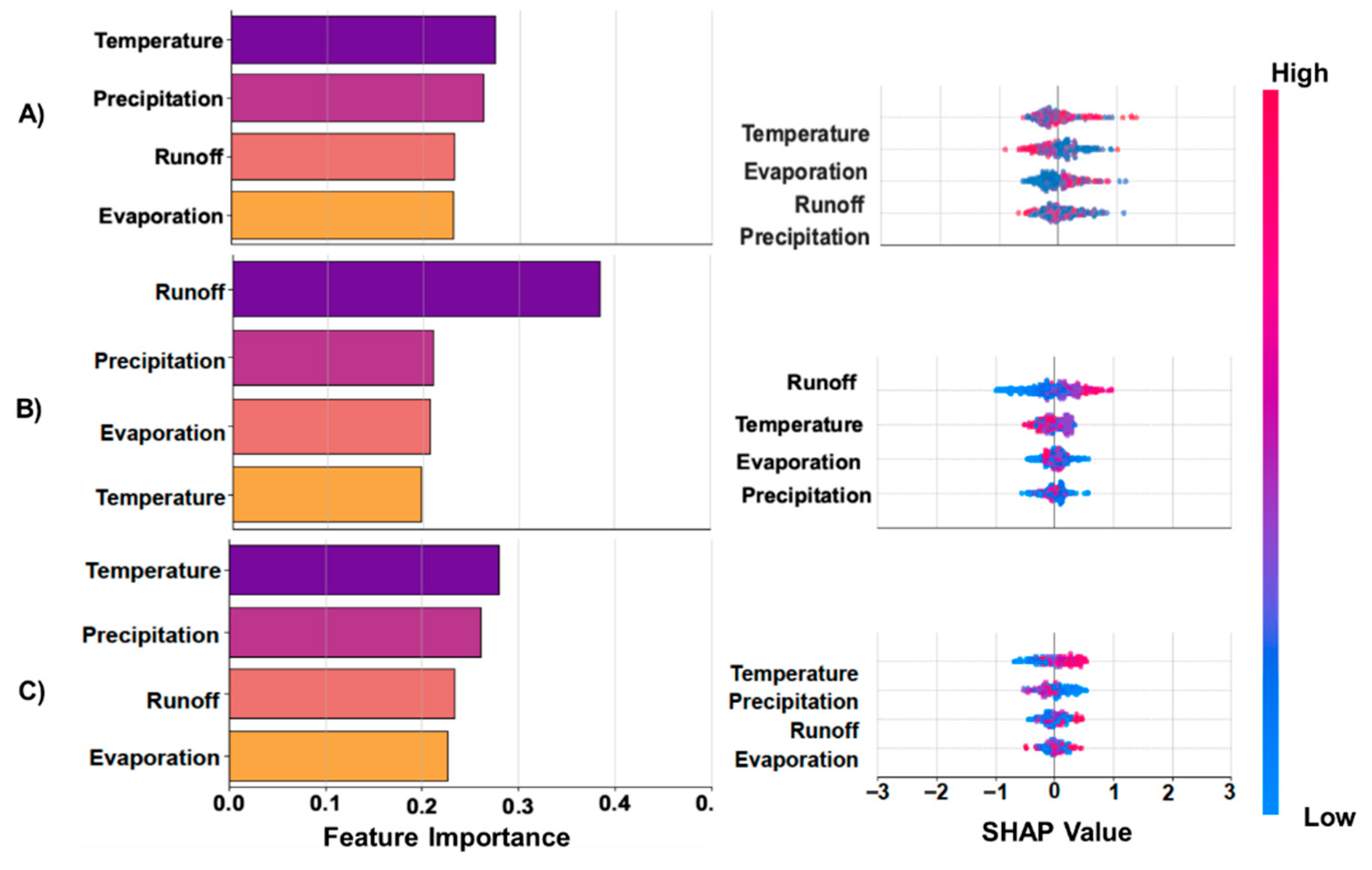

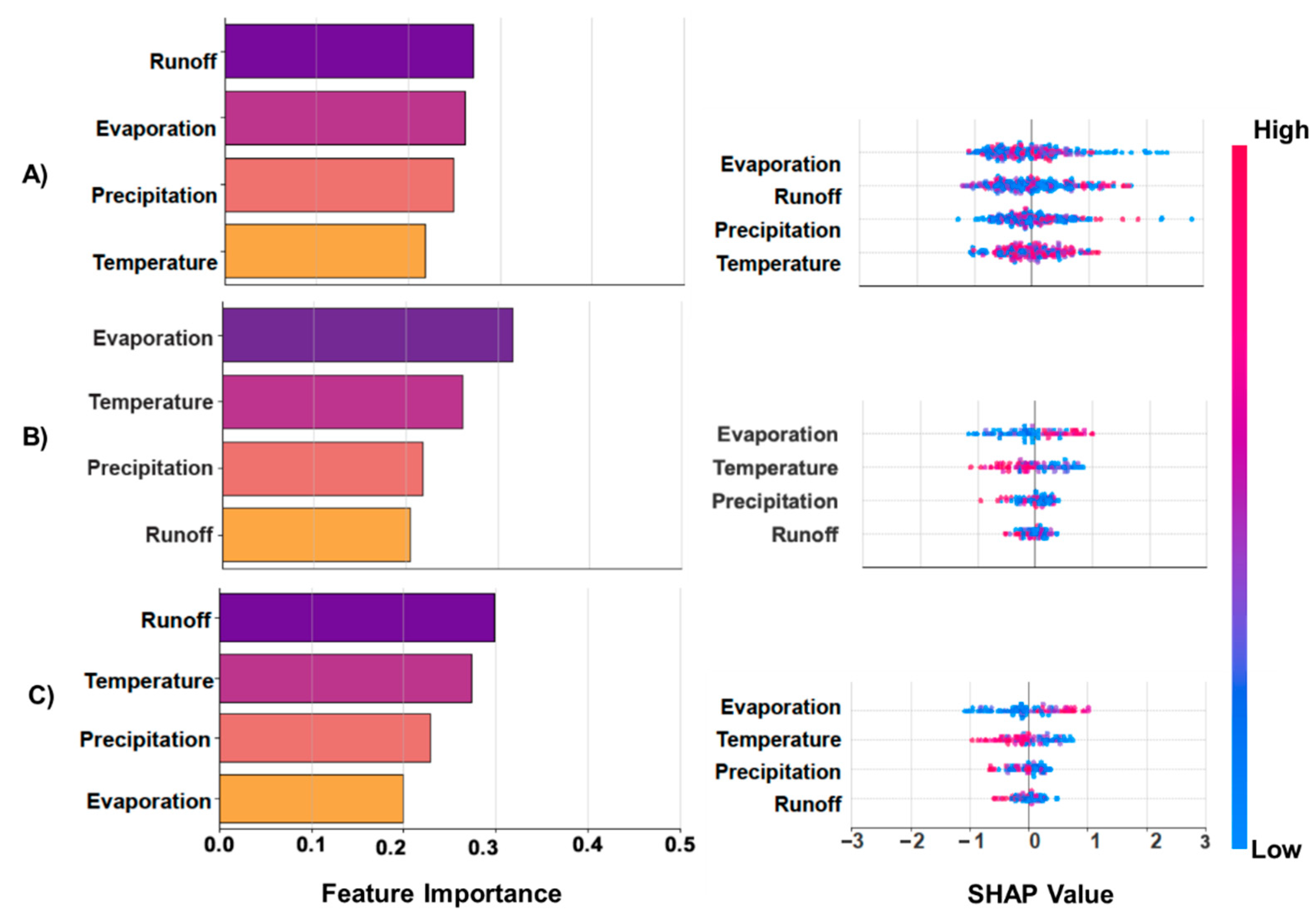

2.9. Feature Importance and SHAP Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Sentinel-3A Water Level Estimates: Comparison of Level-2 Retracking Methods and Threshold-Based Subwaveform Retracking on Level-1 Data

3.2. Water Level Trends Across the TP (2016–2024)

3.3. Geographic Grouping and Hydrological Dynamics of TP Lakes and Climate Influence

3.3.1. Eastern Lakes (Ngoring, Qinghai)

3.3.2. Western Lakes (Lumajang Dong, Jieze)

3.3.3. Southern Lakes (Zhari Namco, Siling, Langacuo)

3.3.4. Northern Lakes (Lexie Wudan, Hoh Xil, Migriggyangzham)

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Hydrological Drivers

4.2. Validation and Methodological Limitations

4.3. Research Gaps and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pastorino, P.; Elia, A.C.; Pizzul, E.; Bertoli, M.; Renzi, M.; Prearo, M. The Old and the New on Threats to High-Mountain Lakes in the Alps: A Comprehensive Examination with Future Research Directions. Ecological Indicators 2024, 160, 111812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Q. Land–Climate Interaction over the Tibetan Plateau. 2018.

- National Research Council Himalayan Glaciers: Climate Change, Water Resources, and Water Security; National Academies Press, 2012; ISBN 0-309-26099-X.

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Xie, H.; Yang, K.; Zhu, L.; Shum, C.K.; Bolch, T.; Yi, S.; Allen, S.; Jiang, L.; et al. Response of Tibetan Plateau Lakes to Climate Change: Trends, Patterns, and Mechanisms. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 208, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang GuoQing, Z.G.; Yao TanDong, Y.T.; Chen WenFeng, C.W.; Zheng GuoXiong, Z.G.; Shum, C.; Yang Kun, Y.K.; Piao ShiLong, P.S.; Sheng YongWei, S.Y.; Yi Shuang, Y.S.; Li JunLi, L.J. Regional Differences of Lake Evolution across China during 1960s-2015 and Its Natural and Anthropogenic Causes. 2019.

- Woolway, R.I.; Kraemer, B.M.; Lenters, J.D.; Merchant, C.J.; O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S. Global Lake Responses to Climate Change. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2020, 1, 388–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Kurbaniyazov, A.; Kirillin, G. Changing Pattern of Water Level Trends in Eurasian Endorheic Lakes as a Response to the Recent Climate Variability. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.T. Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change: Contribution of Working Group I to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, 1996; Vol. 2; ISBN 0-521-56436-0.

- Pepin, N.; Arnone, E.; Gobiet, A.; Haslinger, K.; Kotlarski, S.; Notarnicola, C.; Palazzi, E.; Seibert, P.; Serafin, S.; Schöner, W. Climate Changes and Their Elevational Patterns in the Mountains of the World. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60, e2020RG000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Jiao, J.J. Review on Climate Change on the Tibetan Plateau during the Last Half Century. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2016, 121, 3979–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.P.; Barlow, M.; Byrne, M.P.; Cherchi, A.; Douville, H.; Fowler, H.J.; Gan, T.Y.; Pendergrass, A.G.; Rosenfeld, D.; Swann, A.L. Advances in Understanding Large-scale Responses of the Water Cycle to Climate Change. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2020, 1472, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancamaria, S.; Andreadis, K.M.; Durand, M.; Clark, E.A.; Rodriguez, E.; Mognard, N.M.; Alsdorf, D.E.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Oudin, Y. Preliminary Characterization of SWOT Hydrology Error Budget and Global Capabilities. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2009, 3, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiklomanov, A.I.; Lammers, R.B.; Vörösmarty, C.J. Widespread Decline in Hydrological Monitoring Threatens pan-Arctic Research. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 2002, 83, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Durand, M.; Jung, H.C.; Alsdorf, D.; Shum, C.; Sheng, Y. Characterization of Surface Water Storage Changes in Arctic Lakes Using Simulated SWOT Measurements. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2010, 31, 3931–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, P.; Roohi, S.; Voosoghi, B.; Amini, A.; Poreh, D. Sea Surface Height Estimation from Improved Modified, and Decontaminated Sub-Waveform Retracking Methods over Coastal Areas. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzenhofer, M.; Shum, C.; Rentsh, M. Coastal Altimetry and Applications. Ohio State University Geodetic Science and Surveying Tech. Rep 1999, 464, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Jinyum, G.; Cheiway, H.; Xiaotao, C.; Yuting, L. Improved Threshold Retracker for Satellite Altimeter Waveform Retracking over Coastal Sea. Progress in Natural Science 2006, 16, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, D.; Chander, S.; Desai, S.; Chauhan, P. A Subwaveform-Based Retracker for Multipeak Waveforms: A Case Study over Ukai Dam/Reservoir. Marine Geodesy 2015, 38, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chang, X.; Gao, Y.; Sun, J.; Hwang, C. Lake Level Variations Monitored with Satellite Altimetry Waveform Retracking. IEEE journal of selected topics in applied earth observations and remote sensing 2009, 2, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian Sorkhabi, O.; Asgari, J.; Amiri-Simkooei, A. Wavelet Decomposition and Deep Learning of Altimetry Waveform Retracking for Lake Urmia Water Level Survey. Marine Georesources & Geotechnology 2022, 40, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, B.; Sheng, Y.; Bird, B.W.; Zhang, G.; Tian, L. Response of Inland Lake Dynamics over the Tibetan Plateau to Climate Change. Climatic Change 2014, 125, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xie, H.; Duan, S.; Tian, M.; Yi, D. Water Level Variation of Lake Qinghai from Satellite and in Situ Measurements under Climate Change. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2011, 5, 053532–053532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, F.P.; Heizmann, M. Strategies to Detect Non-Linear Similarities by Means of Correlation Methods. Intelligent Robots and Computer Vision XX: Algorithms, Techniques, and Active Vision 2001, 4572, 513–524. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Sun, J.; Yang, K.; Pepin, N.; Xu, Y. Revisiting Recent Elevation-dependent Warming on the Tibetan Plateau Using Satellite-based Data Sets. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2019, 124, 8511–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, N.; Deng, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Kang, S.; Yao, T. An Examination of Temperature Trends at High Elevations across the Tibetan Plateau: The Use of MODIS LST to Understand Patterns of Elevation-dependent Warming. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2019, 124, 5738–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, F.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Gong, X.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of the Weighted Mean Temperature over China Using Multiple Reanalysis Data and Radiosonde. Atmospheric Research 2023, 285, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. China’s Tibet; CICC, 2004; ISBN 7-5085-0608-1.

- Yang, Q.; Zheng, D. Tibetan Geography; CICC, 2004; ISBN 7-5085-0665-0.

- Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, L.; Shangguan, D.; Yao, X.; Wei, J.; Bao, W.; Yu, P.; Liu, Q. The Second Chinese Glacier Inventory: Data, Methods and Results. Journal of Glaciology 2015, 61, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, F.; Berthier, E.; Wagnon, P.; Kääb, A.; Treichler, D. A Spatially Resolved Estimate of High Mountain Asia Glacier Mass Balances from 2000 to 2016. Nature geoscience 2017, 10, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Weidman, R.P.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Gao, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, H. Recent Water-Level Fluctuations, Future Trends and Their Eco-Environmental Impacts on Lake Qinghai. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 333, 117461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xie, C.; Wu, T.; Wu, X.; Yang, G.; Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Pang, Q.; Liu, G.; et al. Permafrost Characteristics and Potential Influencing Factors in the Lake Regions of Hoh Xil, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.; Gao, D.; An, F. Radiocarbon and Luminescence Dating of Lacustrine Sediments in Zhari Namco, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9, 640172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yao, T.; Sheng, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y. Unprecedented Lake Expansion in 2017–2018 on the Tibetan Plateau: Processes and Environmental Impacts. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 619, 129333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatke, C.; Dettmering, D.; Bosch, W.; Seitz, F. DAHITI–an Innovative Approach for Estimating Water Level Time Series over Inland Waters Using Multi-Mission Satellite Altimetry. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2015, 19, 4345–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J. Dynamic Change and Spatial Analysis of Great Lakes in China Based on Hydroweb and Landsat Data. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2021, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.; Ries, J.; Haines, B.; Fu, L.; Callahan, P. Satellite Altimetry and Earth Sciences. (L.-L. Fu & A. Cazenave, Eds.). Academic Press, International Geophysics series 2001, 69, 1–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.-L.; Cazenave, A. Satellite Altimetry and Earth Sciences: A Handbook of Techniques and Applications; Elsevier, 2000; ISBN 0-08-051658-0.

- Arabsahebi, R.; Voosoghi, B.; Tourian, M.J. The Inflection-Point Retracking Algorithm: Improved Jason-2 Sea Surface Heights in the Strait of Hormuz. Marine Geodesy 2018, 41, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.J.; Lázaro, C. Independent Assessment of Sentinel-3A Wet Tropospheric Correction over the Open and Coastal Ocean. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.H. The Effect of Sub-Surface Volume Scattering on the Accuracy of Ice-Sheet Altimeter Retracking Algorithms.; IEEE, 1993; pp. 1053–1057.

- Villadsen, H.; Deng, X.; Andersen, O.B.; Stenseng, L.; Nielsen, K.; Knudsen, P. Improved Inland Water Levels from SAR Altimetry Using Novel Empirical and Physical Retrackers. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 537, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, S. Performance Evaluation of Different Satellite Radar Altimetry Missions for Monitoring Inland Water Bodies. 2017.

- Roohi, S. Capability of Pulse-Limited Satellite Radar Altimetry to Monitor Inland Water Bodies. 2015.

- Chen, J.; Duan, Z. Monitoring Spatial-Temporal Variations of Lake Level in Western China Using ICESat-1 and CryoSat-2 Satellite Altimetry. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Bastiaanssen, W. Estimating Water Volume Variations in Lakes and Reservoirs from Four Operational Satellite Altimetry Databases and Satellite Imagery Data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2013, 134, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ye, Q.; Sheng, Y.; Gong, T. Combined ICESat and CryoSat-2 Altimetry for Accessing Water Level Dynamics of Tibetan Lakes over 2003–2014. Water 2015, 7, 4685–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busker, T.; de Roo, A.; Gelati, E.; Schwatke, C.; Adamovic, M.; Bisselink, B.; Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A. A Global Lake and Reservoir Volume Analysis Using a Surface Water Dataset and Satellite Altimetry. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2019, 23, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wang, R. Evaluation and Validation of CryoSat-2-Derived Water Levels Using in Situ Lake Data from China. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Guo, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Detecting Lake Level Change from 1992 to 2019 of Zhari Namco in Tibet Using Altimetry Data of TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason-1/2/3 Missions. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9, 640553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Duan, Z. Monitoring Spatial-Temporal Variations of Lake Level in Western China Using ICESat-1 and CryoSat-2 Satellite Altimetry. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:, arXiv:1705.07874 2017.

- Iglewicz, B.; Hoaglin, D.C. Volume 16: How to Detect and Handle Outliers; Quality Press, 1993; ISBN 0-87389-260-7.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Wingham, D.; Rapley, C.; Griffiths, H. New Techniques in Satellite Altimeter Tracking Systems.; 1986; Vol. 86, pp. 1339–1344.

- Frappart, F.; Calmant, S.; Cauhopé, M.; Seyler, F.; Cazenave, A. Preliminary Results of ENVISAT RA-2-Derived Water Levels Validation over the Amazon Basin. Remote Sensing of Environment 2006, 100, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Makhoul, E.; Escorihuela, M.J.; Zribi, M.; Quintana Seguí, P.; García, P.; Roca, M. Analysis of Retrackers’ Performances and Water Level Retrieval over the Ebro River Basin Using Sentinel-3. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitskaya, Y.I.; Rybushkina, G.; Soustova, I.; Balandina, G.; Lebedev, S.; Kostyanoi, A.; Panyutin, A.; Filina, L. Satellite Altimetry of Inland Water Bodies. Water Resources 2012, 39, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Nielsen, K.; Andersen, O.B.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Monitoring Recent Lake Level Variations on the Tibetan Plateau Using CryoSat-2 SARIn Mode Data. Journal of Hydrology 2017, 544, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Bao, A. Changes in Inland Lakes on the Tibetan Plateau over the Past 40 Years. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2016, 26, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Song, C.; Xue, B.; Wu, H.; Ji, Z.; Dong, L. Exploring the Potential Factors on the Striking Water Level Variation of the Two Largest Semi-Arid-Region Lakes in Northeastern Asia. Catena 2021, 198, 105037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xie, M.; Wu, Y. Quantitative Analysis of Lake Area Variations and the Influence Factors from 1971 to 2004 in the Nam Co Basin of the Tibetan Plateau. Chinese Science Bulletin 2010, 55, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, Z.; Guoqing, Z.; Ruimin, Y.; Chong, L.; Kun, Y.; Baojin, Q.; Boping, H. Lake Variations on Tibetan Plateau of Recent 40 Years and Future Changing Tendency. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chinese Version) 2019, 34, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-915788-9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Long, D.; Scanlon, B.R.; Mann, M.E.; Li, X.; Tian, F.; Sun, Z.; Wang, G. Climate Change Threatens Terrestrial Water Storage over the Tibetan Plateau. Nature Climate Change 2022, 12, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Xie, H.; Yang, K.; Zhu, L.; Shum, C.K.; Bolch, T.; Yi, S.; Allen, S.; Jiang, L.; et al. Response of Tibetan Plateau Lakes to Climate Change: Trends, Patterns, and Mechanisms. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 208, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, O.; Bhattacharya, A.; Bolch, T. The Presence and Influence of Glacier Surging around the Geladandong Ice Caps, North East Tibetan Plateau. Advances in Climate Change Research 2021, 12, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhu, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yao, T. Drivers of the Extreme Early Spring Glacier Melt of 2022 on the Central Tibetan Plateau. Earth and Space Science 2024, 11, e2023EA003297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altés, A.; Cornara, F.; Renard, M. Next Generation Gravity Mission (NGGM): Mission Analysis Report; Tech. rep., NGGM-DEM-TEC-TNO-01, Deimos, 2010.

- Peng, Y.; Duan, A.; Zhang, C.; Tang, B.; Zhao, X. Evaluation of the Surface Air Temperature over the Tibetan Plateau among Different Reanalysis Datasets. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11, 1152129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yuan, W. Evaluation of ERA5 Precipitation over the Eastern Periphery of the Tibetan Plateau from the Perspective of Regional Rainfall Events. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 2625–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavers, D.A.; Simmons, A.; Vamborg, F.; Rodwell, M.J. An Evaluation of ERA5 Precipitation for Climate Monitoring. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2022, 148, 3152–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun de Torrez, E.C.; Frock, C.F.; Boone IV, W.W.; Sovie, A.R.; McCleery, R.A. Seasick: Why Value Ecosystems Severely Threatened by Sea-Level Rise? Estuaries and Coasts 2021, 44, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lake Name | Method | R |

Retrieved Trend (m yr-1) |

Difference in Trend (m yr-1) between DAHITI and Our Estimation |

Combined Score |

| Qinghai | Threshold_20 | 0.9983 | 0.3201 | 0.0003 | 0.9980 |

| OCOG | 0.9892 | 0.3136 | 0.0065 | 0.9827 | |

| Lexie Wudan | Threshold_10 | 0.9839 | 0.5153 | 0.0092 | 0.9747 |

| OCOG | 0.8980 | 0.5020 | 0.0225 | 0.8755 | |

| Lumajang dong | Threshold_60 | 0.9210 | 0.3028 | 0.0005 | 0.9205 |

| OCOG | 0.9110 | 0.2894 | 0.0139 | 0.8971 | |

| Zhari Namco | Threshold_30 | 0.9953 | 0.3774 | 0.0013 | 0.9940 |

| Ocean | 0.9891 | 0.3811 | 0.0178 | 0.9713 | |

| Ngoring | Threshold_60 | 0.9357 | 0.0277 | 0.0187 | 0.9170 |

| OCOG | 0.6854 | 0.0195 | 0.0105 | 0.6749 | |

| Hohxil | Threshold_40 | 0.9826 | 0.3577 | 0.0141 | 0.9685 |

| OCOG | 0.9879 | 0.3690 | 0.0254 | 0.9625 | |

| Jieze | Threshold_30 | 0.9780 | 0.2954 | 0.0060 | 0.9720 |

| OCOG | 0.9670 | 0.2788 | 0.0226 | 0.9444 | |

| Migriggyangzham | Threshold_90 | 0.9940 | 0.5259 | 0.0155 | 0.9785 |

| OCOG | 0.9928 | 0.4961 | 0.0453 | 0.9475 | |

| Langacuo | Threshold_30 | 0.9801 | -0.2423 | 0.0104 | 0.9697 |

| OCOG | 0.9642 | -0.2432 | 0.0113 | 0.9529 | |

| Siling | Threshold_20 | 0.9962 | 0.3529 | 0.0005 | 0.9957 |

| OCOG | 0.9954 | 0.3561 | 0.0026 | 0.9928 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).