1. Introduction

In recent decades, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a major global health threat, contributing to high rates of morbidity and mortality, and highlighting the urgent need for innovative and effective containment strategies [

1]. Despite substantial efforts, overcoming antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains challenging, as the discovery and development of new antimicrobial agents are time-intensive, costly, and frequently hindered by issues of high toxicity and limited clinical efficacy [

2].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted the growing prevalence of multidrug-resistant microorganisms in water bodies, accelerating the spread of resistance [

3]. In Brazil alone, an estimated 34,000 annual deaths are directly linked to AMR, with an additional 138,000 associated with related complications. Poor waste management practices, particularly the improper discharge of domestic and hospital effluents, introduce pathogenic bacteria and antibiotics into aquatic environments, fostering an ecosystem for the selection and horizontal transfer of resistance genes [

4,

5,

6].

In this context, the development of safe and efficient water purification and microbial control technologies has become increasingly critical. Nanotechnology, especially the application of metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs), offers a promising strategy to combat AMR. These nanomaterials, characterized by their high surface area and nanoscale effects, operate via multiple mechanisms: (i) generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or metal ion release, leading to microbial DNA and protein damage; (ii) disruption of microbial cell membranes; and (iii) interference with electron transport across membranes, compromising vital cellular functions [

7].

Nevertheless, the clinical translation of conventional metallic NPs faces significant challenges. Gold nanoparticles are expensive, silver nanoparticles are unstable under light, and copper nanoparticles may exert toxicity by interfering with essential physiological processes [

8]. In contrast, zinc oxide (ZnO) and bismuth (Bi) nanoparticles have emerged as safer, more stable, and effective alternatives, demonstrating potent antimicrobial properties against resistant strains and biofilms, while maintaining low toxicity and high chemical stability [

9,

10,

11].

Zinc bismuthate-based materials have attracted increasing attention for their notable bactericidal activity [

12,

13] and promising applications in the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in aquatic environments [

14,

15]. Their nanostructures also offer high surface areas and excellent electrochemical performance [

16]. However, their antimicrobial potential remains largely unexplored.

Zinc oxide nanoparticles have been widely recognized for their antibacterial and antifungal activities against diverse Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. Their bactericidal effect is primarily attributed to the generation of oxidative stress via ROS [

17,

18,

19]. Recent evidence suggests that ROS generation can occur without light. The process is facilitated by structural defects such as oxygen vacancies (Vo) which distort the ZnO crystalline lattice and enhance electron transfer to adsorbed molecules, thus sustaining ROS production [

20].

While zinc bismuthate/zinc oxide nanocomposites have been investigated for their photocatalytic efficiency [

14,

21], no studies to date have evaluated their antimicrobial efficacy. In this study, we report the hydrothermal synthesis of these nanocomposites and assess, for the first time, their antimicrobial performance and toxicity.

The hydrothermal method offers significant advantages for nanoparticle synthesis, including excellent reproducibility, cost-effectiveness, simple operation, and environmental friendliness [

22,

23,

24]. It enables precise control over particle morphology and size, employing a high-pressure autoclave system typically composed of stainless steel with Teflon lining [

25,

26].

Thus, this work aims to synthesize, characterize, and evaluate the antibacterial and antifungal activities of zinc bismuthate/zinc oxide nanocomposites (ZB1 and ZB4) against Staphylococcus aureus, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Candida albicans, while also investigating their toxicity profiles to establish their potential as safe and innovative antimicrobial agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate (98%, Sigma-Aldrich), Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate (98%, Synth), Potassium Hydroxide (analytical purity, Dinâmica Química), Glacial Acetic Acid (99%, Neon). Additionally, other laboratory reagents such as Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth were used for the microbiological analyses. All reagents used in this work were obtained from commercial suppliers, and were used without additional purification, ensuring the reproducibility of the synthesis.

2.2. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nanocomposites

The zinc bismuthate-based nanocomposite was synthesized via a hydrothermal method, according to the methodology adapted from Dilly Rajan et al. [

27]. First, 2 mmol of Bi(NO

3)

3·5H

2O were dissolved in 3 mL of ultrapure water, to which 5 mL of glacial acetic acid (PA) were added, forming precursor solution A. Simultaneously, 1 mmol of Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O was dissolved in 5 mL of ultrapure water, yielding solution B.

The precursor solutions A and B were mixed under constant stirring. Then, a 10 mol·L-1 aqueous solution of KOH was slowly added dropwise until the pH of the reaction medium reached 13. The resulting suspension was kept under moderate stirring for 2 hours and then transferred to a Teflon bottle, which was sealed and placed in a hydrothermal reactor (Welljoin brand). The system was then subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 180 °C for 12 hours, using a muffle furnace (Jung brand) with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. After the process, the reactor was cooled to room temperature, and the material obtained was carefully collected and washed repeatedly with ultrapure water until the supernatant presented neutral pH. Finally, the sample was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 hours, deagglomerated and named ZB1.

2.3. Synthesis of Nanocomposites Using the Monowave 50 Reactor

The synthesis of zinc bismuthate-based nanocomposite was also performed using a more robust reactor, with better control of heating, pressure, time and temperature (Monowave 50, Anton Paar), where it was possible to optimize the synthesis method at 180 °C in only 1 hour. Thus, solution A was prepared by dissolving 2 mmol of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O in 3 mL of ultrapure water, followed by the addition of 5 mL of glacial acetic acid (P.A.).

Simultaneously, solution B was prepared from 1 mmol of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O in 6 mL of ultrapure water at room temperature. The precursor solutions (A and B) were then mixed under stirring and the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 13 by adding, dropwise, 10 mol·L-1 aqueous KOH solution. The suspension was transferred to the reaction tube of the Monowave 50 system, where it was subjected to programmed hydrothermal treatment. After cooling to room temperature, the material was collected and subjected to successive washings with ultrapure water until the supernatant presented neutral pH. The sample was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 hours, deagglomerated and labeled as ZB4.

2.4. Characterization

The crystal structure of the zinc bismuthate-based nanocomposites was investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer under copper kα1/kα2 radiation (λ = 1.540598/1.544426Å), at 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. The diffraction patterns were obtained in a scanning range of 2θ = 10–80°, with a step of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 2°/min. In order to complement the structural analyses, Raman spectroscopy spectra were acquired using a T64000 spectrometer (Horiba/Jobin Yvon) using a 532 nm laser at a power of 90 mW, covering the spectral range from 100 a 1000 cm⁻¹. The morphological and structural characterization of the samples was performed by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), using the MEI equipment, model Tecnai FEG G2F20, operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The microscope is equipped with EDS (Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy) and EELS (Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy) detectors, coupled to the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) system. For this analysis, samples ZB1 and ZB4 were dispersed in isopropyl alcohol and each solution was placed on a copper (Cu) grid with carbon film. The determination of the zeta potential was performed for the ZB4 sample, by means of the aqueous dispersion of 0.001 g of the powder in 10 mL of ultrapure water (pH 7), using the Zetasizer Nano ZS90 equipment (Malvern Instruments®). The suspension was sonicated for 2 minutes before the measurements, ensuring the adequate dispersion of the particles.

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity Assay

The microorganisms were cultured in Petri dishes with BHI (Brain Heart Infusion) agar and incubated at 37 °C ± 1 °C for 24 hours. The evaluation of the inhibition zones was performed in triplicate, with the measurement of the diameters in millimeters using a millimeter ruler, followed by the calculation of the arithmetic mean and standard deviation of the values obtained. ZB1 and ZB4 samples, in the amount of 10 mg, were dispersed in DMSO solution (10%, pH 7), and 50 μL of each solution was applied to 6 mm diameter wells in plates seeded with pathogenic bacteria and fungi. For the control test, only DMSO was used. The microbial suspension was standardized by the McFarland scale (1.5 x 10

8 CFU/mL for bacteria and 6 x 10

8 CFU/mL for fungi). The tests followed the disk diffusion method adapted from Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) [

28]. For this test, the strains tested were the bacteria

Corynebacterium diphtheriae (ATCC 36053),

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) and

Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 700603), as well as the fungi

Candida albicans (ATCC 14053) and

Cryptococcus neoformans (clinical isolate).

In addition, the antimicrobial activity of the nanoparticles was evaluated by determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), using an adaptation of the broth microdilution method performed in 96-well plates, according to the CLSI guidelines [

29]. All materials used in the microbiological assay, such as tips, plates and tubes, were previously autoclaved, and a 2000 μg/mL solution of the nanocomposites (ZB1 and ZB4) was prepared with 50% DMSO. In each well, 100 μL of BHI broth and 100 μL of the nanocomposite solution were added, followed by serial microdilutions. After that, 10 μL of bacterial or fungal inoculum (10⁵ CFU/mL) were added to the respective wells. As a positive control, only the culture medium and the microbial inoculum were used. The negative control consisted of the culture medium containing the microbial inoculum together with the drugs chloramphenicol (antibiotic) or amphotericin B (antifungal). Furthermore, a sterility control was performed to ensure the absence of contamination in the samples containing ZB1 and ZB4. All assays were performed in triplicate and incubated at 37 °C ± 1 °C for 24 hours.

2.6. Toxicity Analysis

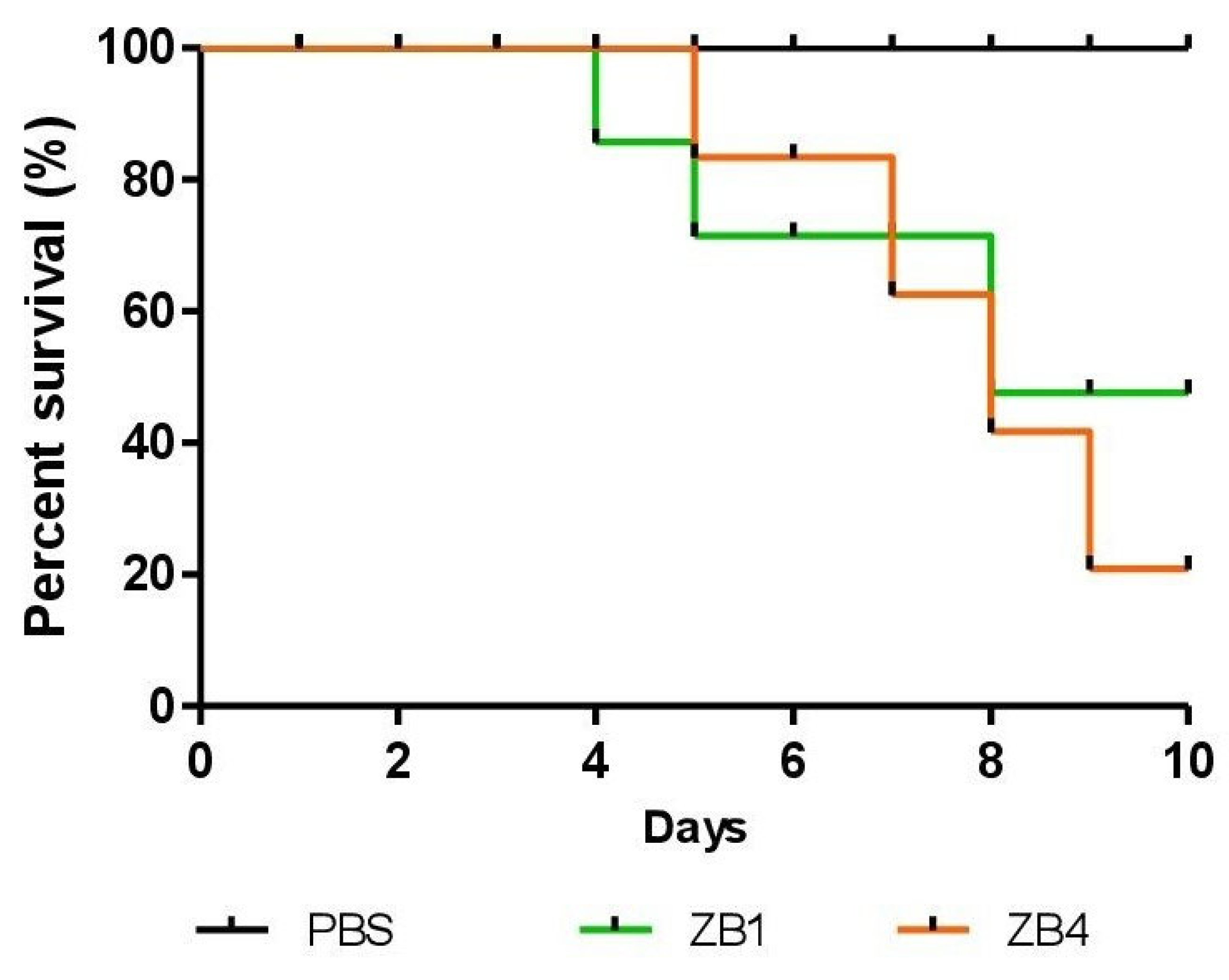

The toxicity test was performed with the aim of analyzing the possible toxic effects of zinc bismuthate nanocomposite samples on Tenebrio molitor larvae. The Petri dishes were identified with the sample data, with one dish for each sample and a control group using PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline).

The larvae were carefully selected, separated and subjected to an aseptic process, which consisted of rapid immersion in 70% ethanol for 30 seconds, followed by rinsing with sterile saline solution (PBS) and drying under aseptic conditions on sterile paper. After the procedure, the larvae were kept in sterile containers until the time of the experiments, ensuring that they were of similar size, weight and larval stage. Then, 10 larvae were placed on each plate and chilled on ice to induce a state of hibernation, which facilitated their handling. Using 1 mL disposable syringes and needles, 10 μL of the samples were injected into the third ring of each larva, forming groups of 10 larvae on each Petri dish. Subsequently, the plates with the larvae were kept at room temperature and monitored daily for a period of 10 days. The data obtained were organized and analyzed using the Origin software.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Statistical evaluation was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The data obtained fromthe toxicity assay using the synthetic compounds were first subjected to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the treatments with the positive control. The survival curve was plotted based on the Kaplan-Meier analysis and the results were analyzed by the log-rank test. In all tests, a significance level of 95% was considered a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

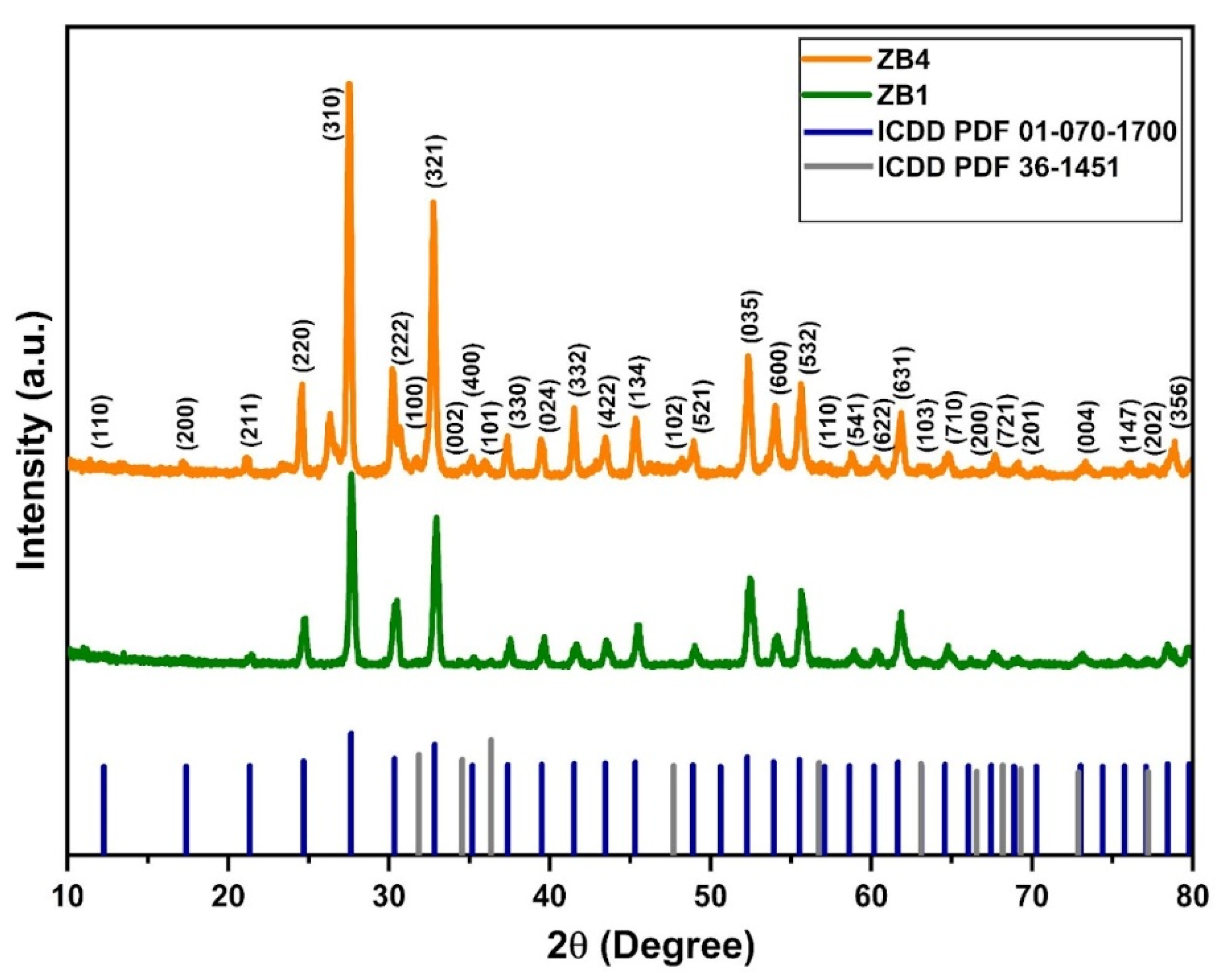

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Zinc Bismuthate-Based Nanocomposites

Figure 1 shows the diffractograms of samples ZB1 and ZB4, synthesized by hydrothermal method. For sample ZB1, the diffraction patterns indicated the predominant formation of the cubic crystal structure of zinc bismuthate (Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40) with intense peaks at 2θ = 27.6°, 32.8° and 52.2° corresponding to the planes (310), (321) and (035), according to the ICDD PDF reference standard no. 01-070-1700. Similarly, sample ZB4 exhibited diffraction peaks that were also indexed according to the same pattern, corroborating the presence of the same cubic crystalline phase characteristic of zinc bismuthate. However, secondary peaks were also detected at 2θ = 31.8°, 34.5° and 36.3°, corresponding to the (100), (002) and (101) planes, characteristic of the hexagonal phase of wurtzite-type zinc oxide (ZnO), according to the ICDD PDF standard nº 36-1451 [

30]. These results suggest the presence of a secondary ZnO phase in the ZB4 sample, indicating the formation of the Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40/ZnO nanocomposites, which can significantly impact the structural and functional properties of the material.

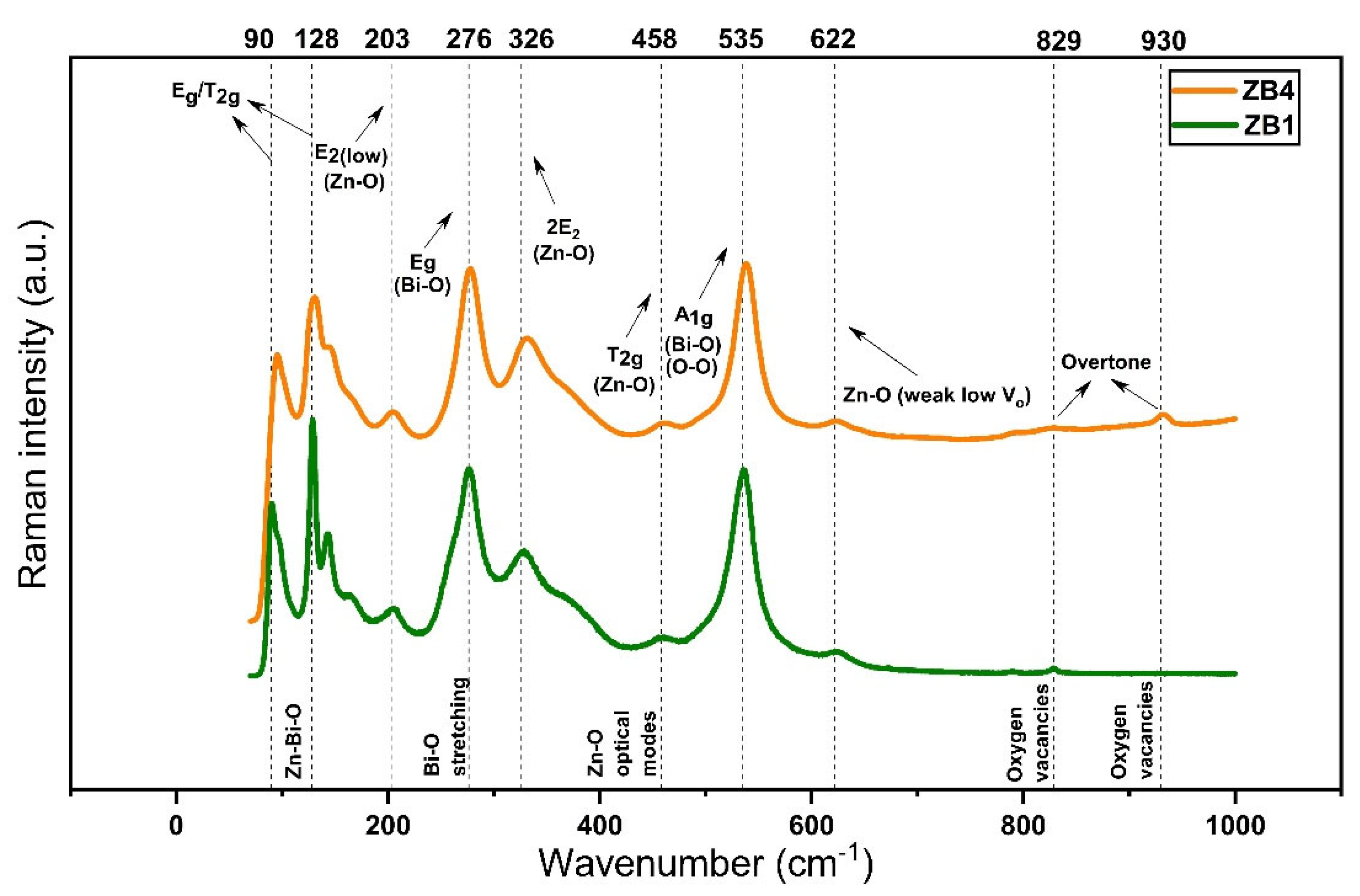

3.2. Vibrational Analysis by Raman Spectroscopy: Structural Confirmation and Effects Induced by ZnO e Bi³⁺

Figure 2 illustrates the Raman spectra of samples ZB1 and ZB4, allowing the investigation of the vibrational characteristics of the nanocomposites. The results of the factor group analysis performed for both structures, based on factor group, are presented in

Table S1 (see Supplementary Material,

Table S1), which shows the contribution of each type of atom to the total vibrational degree of freedom of each crystallographic structure. The reducible symmetry equations for both phases are presented below: i) Zn₀.₆₆₇Bi₂₅.₃₃₃O₄₀ (cubic structure, Fd-3m), Γoptical = A

1g + E

g + 3T

2g (Raman) + 4T

1u (IR) + T

1u + 2A

2u + 2E

u + 2T

2u (inactive); ii) ZnO (wurtzite-like hexagonal structure, P6₃mc), Γoptical = A

1 + 2B

1 + E

1 + 2E

2, where modes A

1 and E

1 are active in both Raman and infrared (IR), E₂ is exclusively Raman active and B

1 is inactive under ideal symmetry [

31]. In

Figure 2, the peaks located at 90 cm

-1 and 128 cm

-1 were related to the E

g and T

2g modes, characteristic of the cubic zinc bismuthate matrix, reflecting coordinated displacements of the metal atoms in Zn–Bi–O [

32,

33]. The presence of ZnO with wurtzite structure was confirmed by the peaks at 203 cm

-1 and 326 cm

-1, associated with the E

2(low) and 2E

2 modes, respectively, attributed to the vibrations of the Zn–O subarray [

34]. The mode at 276 cm

-1 was attributed to the stretching of the Bi–O bond, while the modes at 458 cm

-1 and 535 cm

-1 corresponded, respectively, to the degenerate triple bending T

2g due to the symmetric stretching (A

1g) of Bi–O and O–O [

35,

36,

37]. The lower intensity peaks observed at 622 cm

-1, 829 cm

-1 and 930 cm

-1 indicated the presence of structural defects associated with oxygen vacancies and harmonic vibrational modes [

38].

These oxygen vacancies may contribute to the non-stoichiometry of the compounds and justify the formation of ZnO. The presence of ZnO in the zinc bismuthate matrix suggests induction of structural micro deformations, evidenced by the broadening and shifting of the Raman peaks, especially in the T

2g and A

1g modes [

39] and calculated by the Williamson Hall method based on the XRD data of ZB1 and ZB4, with average microstrain densities of 2.204 and 1.68 µ.nm

-2, respectively (see Supplementary Material,

Table S2) [

40]. These more expressive microstrain density data in sample ZB1, which decrease with increasing hydrothermal treatment temperature, were attributed to the partial replacement of Bi

3+ by Zn

2+, resulting in local stresses and symmetry breaking in the crystal lattice and allowing the spectroscopic activation of modes that would supposedly be inactive [

41].

Such structural effects, especially local micro deformations and degeneracy of vibrational modes, are phenomena discussed in the literature on doped oxides that can favor the generation of oxidative radicals (ROS) [

42]. Although no ZnO phase was detected in ZB1 sample by X-ray diffraction (XRD), possibly due to its concentration being below the detection limit of the technique, its presence was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, which showed greater sensitivity in identifying this minority phase.

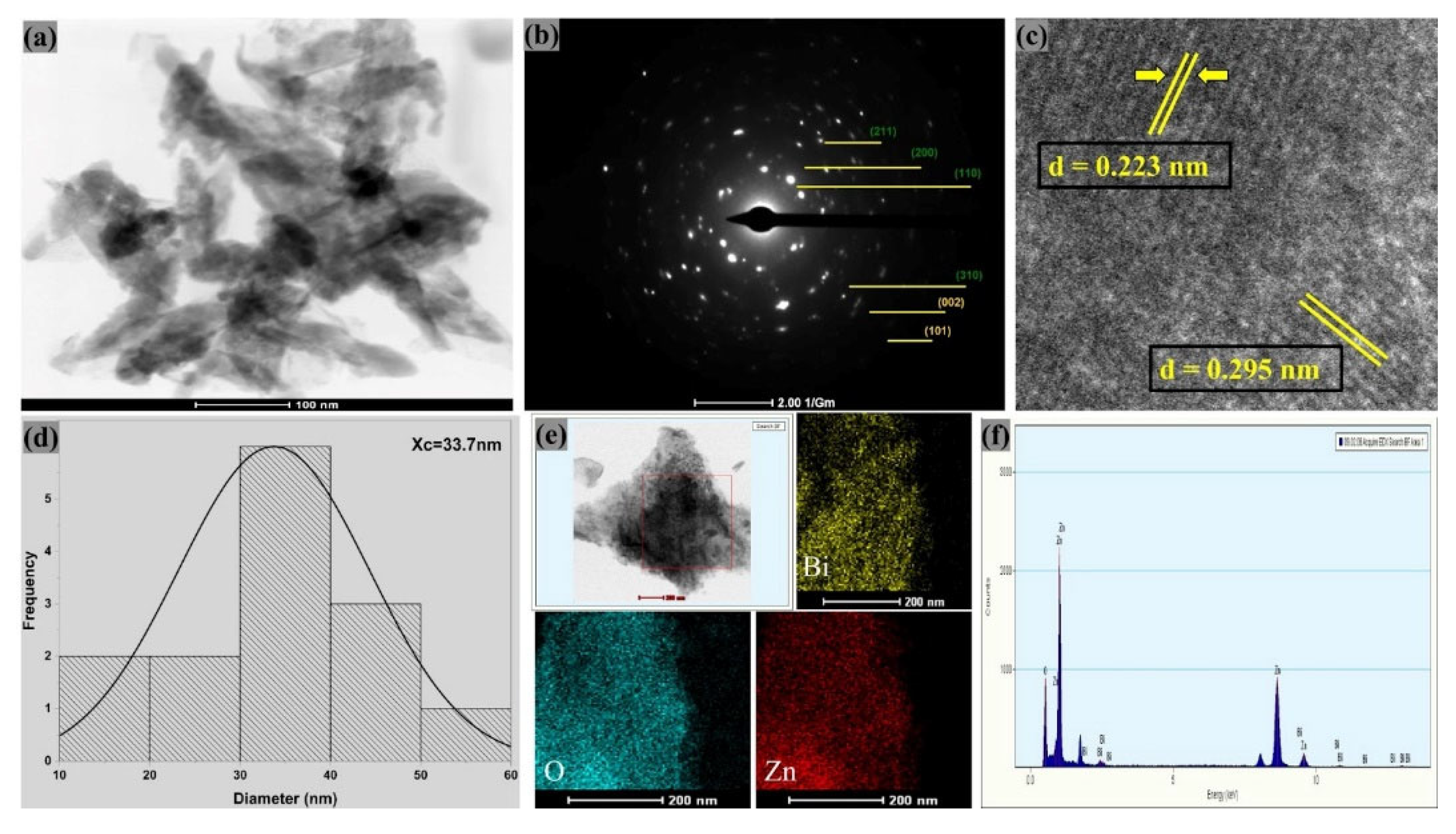

3.3. Morphological Analysis Versus Structural Defects of Nanocomposites

Spectroscopic and microscopic analyses of samples ZB1 and ZB4 revealed the presence of oxygen vacancies (Vo), among other structural defects, which play an important role in the physicochemical and functional properties of the nanocomposites (Zn₀.₆₆₇Bi₂₅.₃₃₃O₄₀/ZnO), as will be detailed below.

To complement these observations, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) analysis was conducted to more accurately evaluate the morphology and crystal structure of the nanoparticles. HR-TEM images and selected electron diffraction (SAED) patterns allowed the investigation of the crystal organization of the samples, while the mean particle size distribution and elemental mapping provided additional information on the homogeneity and composition of the nanocomposites, as illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

The TEM micrographs of both materials, as shown in

Figure 3 (a) and

Figure 4 (a), confirm the presence of agglomerated nanoparticles, mixed morphology and lamellar structures, which are consistent with materials containing ZnO and zinc bismuthate, as they can present anisotropic growth [

43]. Smaller particles have a larger surface area due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, resulting in a greater number of exposed atoms and, consequently, more dangling bonds. As a result, the surface atoms of these particles tend to interact with each other, promoting the formation of agglomerations [

44].

Figure 3 (a) shows the presence of nearly spherical nanoparticles, associated with ZnO, and elongated or lamellar structures, possibly attributed to Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40, in sample ZB1. As for ZB4, as illustrated in

Figure 4 (a), lamellar structures are also observed. These structures have promising potential for application as antimicrobial materials, since they can favor the interaction with microorganisms. Furthermore, the presence of these distinct forms suggests that nanocomposites may offer different mechanisms of interaction with bacteria and fungi, increasing their antimicrobial efficacy [

14,

17]. It is known that the synthesis process significantly influences the size and morphology of nanomaterials. Therefore, specific synthesis conditions, such as greater control of temperature, pressure and reaction time, can interfere with morphological changes [

45].

The crystalline nature of the Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40/ZnO samples is confirmed by HR-TEM images. In

Figure 3 (c), interplanar spacings of 0.184 nm and 0.351 nm are observed for ZB1, attributed to the (102) planes of the hexagonal structure of wurtzite ZnO and (220) of the cubic phase of Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40, respectively.

Figure 4 (c) reveals spacings of 0.295 nm and 0.223 nm for ZB4, corresponding to the (100) planes of wurtzite ZnO and (024) of the cubic phase of Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40. These results indicate a strong interaction between the materials in the produced nanocomposites. In the case of ZB4, the data suggest a layered growth, similar to lamellae, associated with the (310) crystal plane, as evidenced by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique.

The electron diffraction patterns obtained by SAED demonstrate the crystalline structure of the ZB1 and ZB4 samples, as illustrated in

Figure 3 (b) and

Figure 4 (b), revealing continuous diffraction rings and bright spots. The continuous rings are a clear sign of high crystallinity. This pronounced crystallinity, together with the polycrystalline characteristic of the material, indicates an organized atomic structure [

45].

Figure 3 (d) and

Figure 4 (d) also show the average particle size (analysis by ImageJ software) being 41.4 nm for ZB1 and 33.7 nm for ZB4. These results confirm that both materials are formed by nanoparticles. This observation is consistent with the calculated average crystallite sizes, being 21.58 nm for sample ZB1 and 25.93 nm for ZB4 (see Supplementary Material,

Table S2). Furthermore, only Zn, Bi and O peaks were observed in the elemental mapping analysis (EDX), thus, no impurities were detected, as shown in

Figure 3 (f) and

Figure 4 (f).

Based on zeta potential analysis, the solution containing Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40/ZnO (ZB4) nanoparticles was stable, since the zeta potential value was between -30 mV and 30 mV. According to the Malvern Instruments manual [

46], zeta potential values between +30 mV and -30 mV facilitate electrostatic interactions between particles and microorganisms. This range of zeta potential values leads to the formation of stable suspensions, due to the intense repulsive forces between particles in a liquid medium, which considerably reduces particle agglomeration [

47].

3.3.1. Spectroscopic Evidence of Oxygen Vacancies

The Raman spectra of samples ZB1 and ZB4 (section 3.2) showed additional bands at 622 cm

-1, 829 cm

-1 and 930 cm

-1, attributed to vibrations associated with structural defects, including oxygen vacancies (V

o). In this context, the presence of oxygen vacancies can activate additional vibrational modes in the Raman spectrum, which under ideal crystal symmetry conditions would be inactive [

48]. In support of this evidence, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) images (

Figure 3C and

Figure 4C) showed regions with imperfect stacking of crystal planes, indicating the presence of structural flaws and grain boundaries. These features are consistent with the existence of oxygen vacancies, which can cause local micro deformations in the crystal structure. Furthermore, partial replacement of Bi

3+ ions by Zn

2+ (section 3.2) may introduce lattice strains, promoting the formation of oxygen vacancies to compensate for the charge difference [

49,

50].

3.3.2. Functional Implications: Potential for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

The presence of oxygen vacancies (V

o) can significantly influence the electronic and optical properties of nanocomposites. In particular, V

o can act as regions capable of capturing and retaining electrons or holes, directly interfering with the mobility of charge carriers and the functional performance of the material, affecting the electrical conductivity, optical properties, photocatalytic and antimicrobial response of the materials. Studies also report that ZnO nanostructures containing V

o can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) on their surface even in the absence of light [

51]. Furthermore, local distortions associated with V

o can impact structural stability and interaction with adsorbed molecules, important aspects for applications in pharmaceutical devices and sensors [

52,

53].

The surface charge of metal oxide particles and, consequently, their stability are influenced by pH and the point of zero charge (PZC), and changes in these characteristics have a direct impact on the biological activity of the particles. PZC is the pH at which the surface charge and zeta potential are equal to zero [

54]. For sample ZB4, PZC was determined at pH 7.6, indicating that its surface is electrically neutral at this value. At pHs below 7.6, the sample surface showed a positive charge, while at higher values, it showed a negative charge.

3.4. Evaluation of the Disk Diffusion Test

According to the methodology used, the presence or absence of inhibition zones against the studied pathogens is shown in

Table 1.

The analyzed samples were active against the microorganisms Corynebacterium diphtheriae (CD), Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and Cryptococcus neoformans (CN). Among them, ZB4 was the most promising with halos ≥ 11.3 mm. It is possible to verify that sample ZB4 caused an inhibition halo of 11.7 mm for CN.

Determining the mechanism responsible for antimicrobial activity is challenging, as it involves several interconnected factors, such as particle size, surface charge, interaction with the bacterial cell wall and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by metal ions [

55,

56].

The results show that the bactericidal activity of zinc bismuthate nanocomposites, represented by samples ZB1 and ZB4 against Gram-positive

C. diphtheriae (CD) and

S. aureus (SA), is strongly associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as OH

•, H

2O

2, O

2•- e O

2, even in the absence of light. This ROS generation by the nanocomposites can be attributed to the previously discussed structural and surface defects, representing a key mechanism for the inhibition of bacterial activity. Cell membrane damage is commonly reported as a result of an increase in ROS generation [

57,

58,

59].

The ZB1 and ZB4 strains also demonstrated antifungal activity against

C. neoformans (CN). One possible explanation for this efficacy is the effect generated by ROS that damage the cellular structures of the fungus, inhibit the biological functions of macromolecules and block DNA replication. In general, these species are effective in disrupting the functioning of efflux pumps, which reduces the ability of microorganisms to eliminate toxins and waste products from the cell [

47,

60].

The presence of lamellar structures, more evident in ZB4, contributes to greater adhesion to the cell surfaces of microorganisms, increasing the chance of direct interaction with the cell wall and favoring the penetration of generated ROS, which is in line with the superior performance observed in tests with

C. neoformans [

61].

Bacterial cells have a negative charge due to the abundant number of carboxyl groups that dissociate, resulting in a negatively charged cell surface. This is also observed in the fungus

C. neoformans, which has a negatively charged polysaccharide capsule. In contrast, the ZB4 nanoparticles have a positive charge band, as mentioned above, with a PZC of 7.6. Therefore, at pH 7, the positive charge of the sample may have caused a strong electrostatic interaction with the bacteria

C. diphtheriae and

S. aureus, and with the fungus

C. neoformans, resulting in damage to the cell membrane and preventing microbial growth [

62,

63,

64,

65].

ZB1 and ZB4 did not demonstrate inhibition of the Gram-negative bacterium

K. pneumoniae (KP), as shown in

Table 1. This may be attributed to the fact that unlike Gram-positive bacteria, the cell wall structure of Gram-negative bacteria is formed by lipids, proteins and lipopolysaccharides, which offers effective protection against biocides, thus hindering the action of ROS from the nanocomposites ZB1 and ZB4. Furthermore, when compared to the other Gram-positive pathogen

S. aureus (SA), KP has a greater negative charge, which is due to the difference in the polarity of the cell membranes between these bacteria. Thus, this would allow a more intense penetration of negatively charged free radicals, such as peroxide ions, which cause damage and cell death in

SA [

66,

67,

68].

It was also possible to observe the absence of inhibition zone for ZB1 and ZB4 against the fungus

Candida albicans (CA). This can be attributed to the intrinsic resistance of this microorganism, since there may be changes in its morphology that consequently disable the fungal lysis process. Furthermore, the fungus Candida can demonstrate resistance mediated by efflux pumps, a process that leads to a decrease in the concentration of the antifungal agent within the fungal cell [

69,

70].

Furthermore, as observed in

Table 1, sample ZB4 demonstrated greater efficiency in both bactericidal and fungicidal inhibition, presenting slightly superior results. This greater efficiency may be related to its average particle size of 33.7 nm. Although both samples (ZB1 and ZB4) are nanometric and have proven effective in the tests, the smaller particle size of ZB4 may have favored greater interaction with microorganisms, intensifying its antimicrobial activity.

3.5. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC)

To investigate the antimicrobial capacity of the particles, tests were also performed to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC) for the microorganisms that presented the greatest inhibition in the disk diffusion test.

Table 2 shows the results of the tests performed with the bacterium

Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Gram-positive) and the fungus

Cryptococcus neoformans.

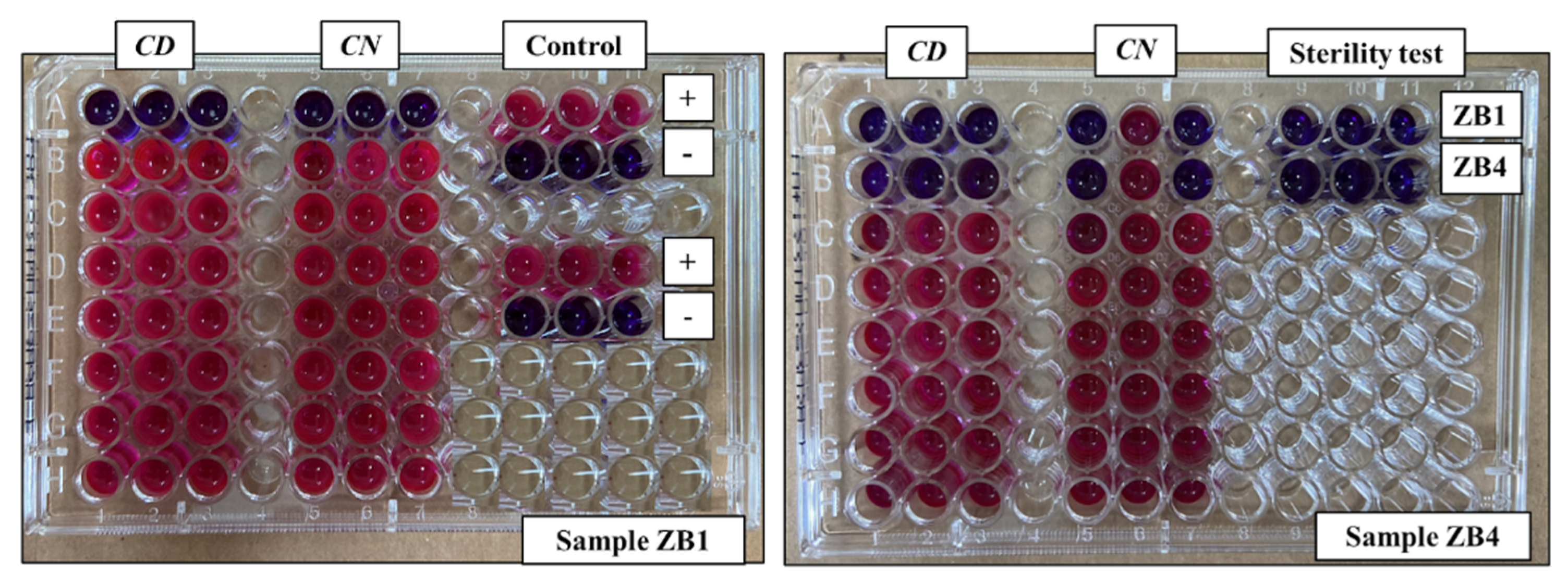

The ZB1 particles showed antimicrobial activity only at a concentration of up to 1000 μg/mL against the bacterium C. diphtheriae (CD) and the fungus C. neoformans (CN). These two microorganisms also showed sensitivity to ZB4, but at a concentration of up to 500 μg/mL.

Figure 5 illustrates how these results were obtained through broth microdilution tests using resazurin. This reagent undergoes a redox reaction when exposed to substances produced by the cellular respiration of microorganisms and is transformed into resorufin. As a results, its color changes from blue to pink, indicating microbial growth [

71].

The smaller average particle size of ZB4 (33.7 nm) compared to ZB1 (41.4 nm) results in higher specific surface area, enhancing contact with microorganisms and, consequently, favoring antimicrobial action, as evidenced by the higher inhibition halos and lower MIC observed [

72].

It is worth mentioning that both synthesized samples (ZB1 and ZB4) presented sterility, with a bluish coloration, as can be observed in the sterility test performed in columns 9 to 11 of

Figure 5. This attests that these samples remained free of contamination throughout the entire procedure.

These findings align well with previous literature. For instance, Geoffrion et al. [

57] highlighted the antibacterial effects of bismuth oxide nanoparticles, attributing their efficacy to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS oxidize polyunsaturated fatty acids in bacterial membranes, promoting lipid peroxidation that leads to significant damage to bacterial cells and membranes [

73]. ROS-mediated oxidative stress is a key mechanism behind the antimicrobial properties of bismuth oxide, and it supports the activity observed in the ZB1 and ZB4 samples.

Campos et al. [

74] also demonstrated antimicrobial potential of bismuth oxide particles against common bacterial pathogens

S. aureus and

E. coli, reinforcing the significance of bismuth compounds in overcoming microbial resistance. Bismuth compounds are known to exhibit both antibacterial and antifungal properties, sometimes exceeding the efficacy of traditional antibiotics [

10,

75]. Despite this potential, their antifungal activity has not been extensively explored [

75]. In comparison, studies on zinc oxide nanoparticles, such as that of Yuan et al. [

76] and Alshahrani et al. [

77], confirm antimicrobial (

Corynebacterium diphtheriae) and antifungal effects (

Cryptococcus neoformans), respectively. The promising results obtained with the zinc bismuthate particles emphasize their potential as effective antimicrobial and antifungal agents with broad-spectrum applications.

3.6. Evaluation of Toxicity Test in Alternative Model

The test and control analyses were performed using an alternative model to evaluate the toxicity of the samples on the larvae of

Tenebrio molitor insect. These analyses produced a survival curve over a period of 10 days, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The samples ZB1 and ZB4 presented a survival rate of 70% and 60%, respectively. When a Log-Rank test was performed comparing the treated groups to the control, a p-value of 0.156 was obtained, indicating that there was no statistically significant difference in toxicity between the samples and the control.

In the study of Rankic et al. [

78], ZnO microparticles resulted in a mortality rate of approximately 33% in Tenebrio molitor larvae. Under certain circumstances, this larvicidal effect can be triggered by inorganic particles, even when they are not formulated for pesticide purposes, as in the case with metals or metal oxides in their pure form. Furthermore, it is widely recognized that the biocompatibility of many materials, especially those at the nano or micro scale, can be limited, requiring rigorous safety assessments for biomedical applications [

78,

79].

The toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles was investigated by Kamaraj et al. [

80]. In this study, 100% larval toxicity was observed in

Aedes aegypti and

Anopheles stephensi. This indicates that ZnO nanoparticles can be used in vector control and prevention of several human diseases.

Given the observed results, a possible explanation for the sublethal effects of sample ZB1 is that the particles may have caused damage to epidermal and dermal cells, leading to signs of dehydration and darkening in some larvae [

78]. However, these effects did not translate into high mortality, as evidenced by the 70% survival rate. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there are still no reports in the scientific literature on toxicity testing specifically involving Zn

0.667Bi

25.333O

40/ZnO nanoparticles. Therefore, this work would be the first with this approach.

4. Conclusions

The synthesis of zinc bismuthate nanocomposites by hydrothermal route was shown to be feasible both in a synthesis reactor with improved temperature and pressure control and in a conventional reactor with resistive heating. In both systems, it was possible to obtain the nanocomposites under mild conditions, such as 180 °C for 1 hour and 180 °C for 12 hours, without the need for an additional calcination step. The ZB1 and ZB4 samples showed inhibitory action against Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Staphylococcus aureus and Cryptococcus neoformans, with emphasis on the latter, the fungus, presenting halos of 10.7 mm and 11.7 mm, respectively. No antimicrobial activity was observed against Candida albicans and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The ZB1 particles exhibited antimicrobial efficacy against C. diphtheriae and C. neoformans only at the concentration of 1000 μg/mL. These two microorganisms were also sensitive to ZB4, limited to a concentration of 500 μg/mL. Furthermore, toxicity analysis performed with Tenebrio molitor larvae revealed that samples ZB1 and ZB4 presented survival rates of 70% and 60%, respectively, after 10 days of exposure. Despite these differences, the Log-Rank test indicated no statistical significance in relation to the control (PBS), with p = 0.156. These results suggest that ZB4 presents a moderate toxicity profile, making it a promising material for biomedical applications due to its effective antimicrobial activity and relative safety.

Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of ZB4 as a promising antimicrobial agent with a moderate toxicity profile, suitable for biomedical applications. The selective antimicrobial performance and favorable biocompatibility suggest that these nanocomposites could serve as effective alternatives against antibiotic-resistant pathogens, particularly C. neoformans and C. diphtheriae. Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of antimicrobial action and to fine-tune synthesis parameters, aiming to expand the antimicrobial spectrum and foster future applications in biomedical and environmental fields.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Vibrational modes identified in the Raman spectra of Zn0.667Bi25.333O40 and ZnO nanocomposites. Table S2: Structural and microstrain parameters of ZB1 and ZB4 nanocomposites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S., E.d.J. and M.S.; data curation, F.S. and E.d.J.; formal analysis, M.S., G.d.S., A.M., C.d.S.; R.d.M. and U.N.; funding acquisition, G.d.S. and E.d.J.; investigation, R.R., E.C., J.R., A.P. and T.S.; methodology, M.D., R.R. and E.C.; validation, resources, visualization, supervision, project administration E.d.J., G.d.S., E.d.S and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.S., E.d.J., M.S. and M.D. All authors read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received funding from the Maranhão Research Foundation (FAPEMA) - BM-01740/23. Master’s scholarship (BM QUOTA IFMA - AGREEMENT No. 01/2022 FAPEMA/IFMA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations used in the manuscript:

| AMR |

Antimicrobial Resistance |

| CD |

Corynebacterium diphtheriae |

| CN |

Cryptococcus neoformans |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| MFC |

Minimum Fungicide Concentration |

| MIC |

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| NPs |

Nanoparticles |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SA |

Staphylococcus aureus |

| ZB1 |

Zn0,667Bi25,333O40/ZnO nanocomposite obtained by conventional hydrothermal synthesis |

| ZB4 |

Zn0,667Bi25,333O40/ZnO nanocomposite obtained by Monowave 50 reactor |

References

- Al Azzam, S.; Ullah, Z.; Azmi, S.; Islam, M.; Ahmad, I.; Hussain, M.K. Tricyclic microwave-assisted synthesis of gold nanoparticles for biomedical applications: combatting multidrug-resistant bacteria and fungus. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 13(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, P. F. de, Porsch, R. F., Rolão, D. L. J., Dantas, F. G. da S., & Oliveira, K. M. P. de. (2024). Desafios e alternativas promissoras na luta contra a resistência antimicrobiana. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde, 24(5), e15237. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Leaders and Experts Call for Action to Protect the Environment from Anti-microbial Pollution. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-world-leaders-and-experts-call-for-action-to-protect-the-environment-from-antimicrobial-pollution (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde. Resistência antimicrobiana no Brasil: impacto, desafios e perspectivas. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/177332-relat%C3%B3rio-alerta-para-risco-de-superbact%C3%A9rias-em-%C3%A1gua-sem-tratamento (accessed on February 2025).

- Nações Unidas Brasil. Relatório alerta para risco de superbactérias em água sem tratamento. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/177332-relat%C3%B3rio-alerta-para-risco-de-superbact%C3%A9rias-em-%C3%A1gua-sem-tratamento (accessed on February 2025).

- Nações Unidas Brasil. O relatório aponta maior resistência de bactérias à ação de antibióticos. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/211154-relat%C3%B3rio-aponta-maior-resist%C3%AAncia-de-bact%C3%A9rias-a%C3%A7%C3%A3o-de-antibi%C3%B3ticos (accessed on February 2025).

- Revathi, G.; Sangari, N.U.; Keerthana, C. Converging microwave and thermal heating to evolve ZnO mazes from nanosheets: Potent solar–photocatalytic and antimicrobial agent. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1330, 141439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Khan, S.A.; Walsh, L.J.; Seneviratne, C.J.; Ziora, Z.M. Characteristics of Metallic Nanoparticles (Especially Silver Nanoparticles) as Anti-Biofilm Agents. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathanarayan, J.B.; Vittal, R.R. Antimicrobial, Biofilm Inhibitory and Anti-infective Activity of Metallic Nanoparticles Against Pathogens MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2017, 5, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Munoz, R.; Arellano-Jimenez, M.J.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Bismuth Nanoparticles Obtained by a Facile Synthesis Method Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans. BMC Biomed. Eng. 2020, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakian, F.; Arasteh, N.; Mirzaei, E.; Motamedifar, M. Study of MIC of Silver and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles, Strong and Cost-Effective Antibacterial against Biofilm-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Shiraz, Southwest of Iran. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nithya, R.; Ayyappan, S. Novel exfoliated graphitic-C₃N₄ hybridised ZnBi₂O₄ (g-C₃N₄/ZnBi₂O₄) nanorods for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol and its antibacterial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 398, 112591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, N.T.T.; Khanh, D.N.N.; Vy, N.T.T.; Khoa, L.H.; Nghia, N.N.; Phuong, N.T.K. Box–Behnken design to optimize herbicide decomposition using an eco-friendly photocatalyst based on carbon dots from coffee waste combined with ZnBi₂O₄ and its antibacterial application. Top. Catal. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi-Yangjeh, A.; Pirhashemi, M.; Ghosh, S. ZnO/ZnBi₂O₄ nanocomposites with p-n heterojunction as durable visible-light-activated photocatalysts for efficient removal of organic pollutants. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 826, 154229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaloudj, O.; Amir Assadi, A.; Azizi, M.; Kenfoud, H.; Trari, M.; Amrane, A.; Assadi, A.A.; Nasrallah, N. Synthesis and characterization of ZnBi₂O₄ nanoparticles: Photocatalytic performance for antibiotic removal under different light sources. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Yu, C.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, Y. A review on ternary bismuthate nanoscale materials. Recent Pat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15(2), 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmal, H.M.S.; Muneer, R.; Saeed, A.; Tanveer, M.; Saeed, M.A. Synergistic role of green-synthesized zinc oxide nanomaterials in biomedicine applications. Chem. Select 2024, 9(36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tameemi, A.I.; Masarudin, M.J.; Rahim, R.A.; Mizzi, R.; Timms, V.J.; Isa, N.M.; Neilan, B.A. Eco-friendly zinc oxide nanoparticle biosynthesis powered by probiotic bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, R.O.; Oliveira, J.M.; Perini, H.F.; Travaglini, U.; Rezende, T.K.L.; dos Santos, F.R.A.; Floresta, L.R.S.; Borges, A.L.S.; Ruiz, L.C.; Silva, L.E.A.; Marinho, J.Z.; Fonseca, F.M.; Oliveira, C.J.F.; Júnior, V.R.; Silva, M.V.; Anhezini, L.; Silva, A.C.A. Enhanced antibacterial efficacy of biocompatible Ag-doped ZnO/AgO/TiO₂ nanocomposites against multiresistant bacteria. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Kar, U.; Jana, N.R. Cytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles under dark conditions via oxygen vacancy dependent reactive oxygen species generation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 13965–13975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, G.; Zinatloo-Ajabshir, S.; Yousefi, A. Innovative synthesis of a novel ZnO/ZnBi₂O₄/graphene ternary heterojunction nanocomposite photocatalyst in the presence of tragacanth mucilage as natural surfactant. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48(5), 6078–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; Tan, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanorods in the presence of sodium citrate and its aqueous colloidal stability evaluation in neutral pH. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 443, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anujency, M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Vinoth, S.; Ganesh, V.; Ade, R. Enhancing the properties of ZnO nanorods by Ni doping via the hydrothermal method for photosensor applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 449, 115379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamuni-Badiger, P.; Ghare, V.; Nikam, C.; Patil, N. The fungal infections and their inhibition by zinc oxide nanoparticles: An alternative approach to encounter drug resistance. Nucleus (India) 2024, 67(2), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Samriti; Cho, J.; Prakash, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of TiO₂ nanorods: formation chemistry, growth mechanism, and tailoring of surface properties for photocatalytic activities. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 20, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalkreem, T.M.; Swart, H.C.; Kroon, R.E. Comparison of Y₂O₃ nanoparticles synthesized by precipitation, hydrothermal and microwave-assisted hydrothermal methods using urea. Nano Struct. Nano Objects 2023, 35, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilly Rajan, K.; Srinivasan, D.; Gotipamul, P.P.; Khanna, S.; Chidambaram, S.; Rathinam, M. Design of a novel ZnBi₂O₄/Bi₂O₃ type-II photo-catalyst via short term hydrothermal for enhanced degradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2022, 285, 115929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-First Informational Supplement, CLSI document M100-S21; 2011; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA.

-

CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—4th ed.; CLSI Standard M27, 2017, 37(10).

- Farhat, O.F.; Halim, M.M.; Abdullah, M.J.; Ali, M.K.M.; Allam, N.K. Morphological and structural characterization of single-crystal ZnO nanorod arrays on flexible and non-flexible substrates. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramike, M.P.; Ndungu, P.G.; Mamo, M.A. Exploration of the Different Dimensions of Wurtzite ZnO Structure Nanomaterials as Gas Sensors at Room Temperature. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanaban, A.; Dhanasekaran, T.; Manigandan, R.; Kumar, S.P.; Gnanamoorthy, G.; Stephen, A.; Narayanan, V. Facile solvothermal decomposition synthesis of single phase ZnBi₃₈O₆₀ nanobundles for sensitive detection of 4-nitrophenol. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 7020–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, P.; Deshagani, S.; Yimer, W.M.; Kumar, R.; Sampath, S. Zn Makes a Difference: Cubic ZnBi₃₈O₆₀ as a Durable and High-Rate Anode for Rechargeable Na-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, Y.; Paramasivam, K.; Franklin, M.C.; Nallathambi, S.; Elayappan, V.; Kuzhandaivel, H. Invasion of Zinc in BiFeO₃/Bi₂₅FeO₄₀ Perovskite-Structured Material as an Efficient Electrode for Symmetric Supercapacitor. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 5418–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narangat, S.N.; Patelav, N.D.; Karthab, V.B. MOLECULAR STRUCTURE Infrared and Raman spectral studies Cu-B&O₃* and normal modes of. J. Mol. Struct. 1994, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Aytac, Y.; Turkten, N.; Kaya, D. From cigarette filters to photocatalysts: Self-carbon-doped ZnO for effective water remediation. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tuan, P.; Hung, N.D.; Ha, L.T. Effect of rGO on the microstructure, electrical, optical, and photocatalytic properties of ZnO/rGO nanorods. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, G.A.R.; et al. Aperfeiçoamento da produção de partículas de óxido de zinco para aplicação em células solares. Cerâmica 2016, 62(361), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.L.S.E.; Franco, A. Raman Spectroscopy Study of Structural Disorder Degree of ZnO Ceramics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 119, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Jabbar, S.S.; Harbbi, K.H. Studying the relationship between the number of unit cells and the dislocation density of a crystal through the X-ray diffraction pattern of barium oxide nanoparticles. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 3018, 040003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzaiene, E.; Rhouma, F.I.H.; Haouas, A.; Khirouni, K.; Dhahri, J. Bi-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles: Enhanced Structural and Dielectric Properties for Device Applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Dohčević-Mitrović, Z.D.; Araújo, V.D.; Radović, M.; Aškrabić, S.; Costa, G.R.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Djokić, D.M.; Stojadinović, B.; Nikolić, M.G. Influence of Oxygen Vacancy Defects and Cobalt Doping on Optical, Electronic and Photocatalytic Properties of Ultrafine SnO₂–δ Nanocrystals. Process. Appl. Ceram. 2020, 14, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Jan, S.; Shah, I.A.; Khan, I. Growth Parameters for Films of Hydrothermally Synthesized One-Dimensional Nanocrystals of Zinc Oxide. Int. J. Photoenergy 2016, 2016, 3153170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.R.; Kamoun, E.A.; Shehata, A.; El-Moslamy, S.H.; Abdel-Rahman, A.A.H. Biosynthesized ZnO NPs loaded-electrospun PVA/sodium alginate/glycine nanofibers: synthesis, spinning optimization and antimicrobial activity evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15(1), 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosaiah, P.; Harikrishnan, L.; Radhalayam, D.; Karim, M.R.; Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Guru Prakash, N.; Ko, T.J. Hierarchical construction of ZnBi₂O₄ anchored on flower-like Bi₂WO₆ heterojunction photocatalyst for removal of alizarin red S. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 58, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvern Instruments. Zeta potential – An introduction in 30 minutes. Available online: https://www.research.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ZetaPotential-Introduction-in-30min-Malvern.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Nxumalo, K.A.; Adeyemi, J.O.; Leta, T.B.; Pfukwa, T.M.; Okafor, S.N.; Fawole, O.A. Antifungal properties and molecular docking of ZnO NPs mediated using medicinal plant extracts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 68979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, H.; Oka, H.; Moriwake, H.; Uchida, H.; Funakubo, H.; Nishida, K. Probing oxygen vacancies in BaTiO₃ powders and single crystals by micro-Raman scattering. In da Silva, L.F.M. (Ed.), Materials Design and Applications 2017, 65, 57–65., Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Mei, Z.; Tang, A.; Azarov, A.; Kuznetsov, A.; Xue, Q.-K.; Du, X. Oxygen vacancies: The origin of n-type conductivity in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 235305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, J.; Ooi, P.C.; Goh, B.T.; Lee, M.K.; Razip Wee, M.F.M.; Shafura A Karim, S.; Ali Raza, S.R.; Mohamed, M.A. Bi-doping improves the magnetic properties of zinc oxide nanowires. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 23297–23311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Xiang, L.; Komarneni, S. Synthesis, properties and applications of ZnO nanomaterials with oxygen vacancies: A review. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 7357–7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Shen, Z.; Peng, F.; Lu, Y.; Ge, M.; Fu, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Dai, N. Improving gas sensing performance by oxygen vacancies in sub-stoichiometric WO₃₋ₓ. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 7723–7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa, S.; Prasanna Kumari, K.; Thomas, B. Contribution of oxygen-vacancy defect-types in enhanced CO₂ sensing of nanoparticulate Zn-doped SnO₂ films. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 17128–17141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizochenko, N.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Syzochenko, M.; Puzyn, T.; Leszczynski, J. Zeta potentials (ζ) of metal oxide nanoparticles: A meta-analysis of experimental data and a predictive neural networks modeling. NanoImpact 2021, 22, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicácio, T.C.N.; Castro, M.A.M.; Melo, M.C.N.; Silva, T.A.; Teodoro, M.D.; Bomio, M.R.D.; Motta, F.V. Zn and Ni doped hydroxyapatite: Study of the influence of the type of energy source on the photocatalytic activity and antimicrobial properties. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50(15), 27540–27552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameen, A.S.; Undre, S.B.; Undre, P.B. Synthesis, dispersion, functionalization, biological and antioxidant activity of metal oxide nanoparticles: Review. Nano Struct. Nano Objects 2024, 39, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffrion, L.D.; Medina-Cruz, D.; Kusper, M.; Elsaidi, S.; Watanabe, F.; Parajuli, P.; Ponce, A.; Hoang, T.B.; Brintlinger, T.; Webster, T.J.; Guisbiers, G. Bi₂O₃ nano-flakes as a cost-effective antibacterial agent. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3(14), 4106–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.-E.; Jin, H.-E. Antimicrobial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nano/Microparticles and Their Combinations against Pathogenic Microorganisms for Biomedical Applications: From Physicochemical Characteristics to Pharmacological Aspects. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, G.N.; Moreira, A.J.; Nóbrega, E.T.D.; Braga, S.; Argentin, M.N.; Camargo, I.L.B.C.; Azevedo, E.; Pereira, E.C.; Bernardi, M.I.B.; Mascaro, L.H. Selective inhibitory activity of multidrug-resistant bacteria by zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12(1), 111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, N.H.; Covington, M.B.; Nguyen, K.; Chandrasekaran, S. Increase of reactive oxygen species contributes to growth inhibition by fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- el Battioui, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Wacha, A.; Molnár, D.; Quemé-Peña, M.; Szigyártó, I.C.; Szabó, C.L.; Bodor, A.; Horváti, K.; Gyulai, G.; Bősze, S.; Mihály, J.; Jezsó, B.; Románszki, L.; Tóth, J.; Varga, Z.; Mándity, I.; Juhász, T.; Beke-Somfai, T. In situ captured antibacterial action of membrane-incising peptide lamellae. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yan, D.; Yin, G.; Liao, X.; Kang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, D.; Hao, B. Toxicological effect of ZnO nanoparticles based on bacteria. Langmuir 2008, 24, 4140–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; He, Y.; Irwin, P.L.; Jin, T.; Shi, X. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Campylobacter jejuni. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.J.; Wear, M.P.; Smith, D.F.Q.; McConnell, S.A.; Casadevall, A.; Oscarson, S. A glycan FRET assay for detection and characterization of catalytic antibodies to the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA n.d., in press. [CrossRef]

- Riahi, S.; Ben Moussa, N.; Lajnef, M.; Jebari, N.; Dabek, A.; Chtourou, R.; Guisbiers, G.; Vimont, S.; Herth, E. Bactericidal activity of ZnO nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 387, 122596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonohara, R.; Muramatsu, N.; Ohshima, H.; Kondo, T. Difference in surface properties between Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus as revealed by electrophoretic mobility measurements. Biophys. Chem. 1995, 55, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianăși, C.; Nemeş, N.S.; Pascu, B.; Lazău, R.; Negrea, A.; Negrea, P.; Duteanu, N.; Ciopec, M.; Plocek, J.; Alexandru, P.; Bădescu, B.; Duda-Seiman, D.M.; Muntean, D. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Multiple Morphologies of Gold/Platinum Doped Bismuth Oxide Nanostructures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amenu, B.; Taddesse, A.M.; Kebede, T.; Mengesha, E.T.; Bezu, Z. Polyaniline-supported MWCNTs/ZnO/Ag₂CO₃ composite with enhanced photocatalytic and antimicrobial applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2024, 21, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; dos Santos Fontenelle, R.O.; de Brito, E.H.S.; de Morais, S.M. Biofilm of Candida albicans: Formation, Regulation and Resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, W.R.V. da; Nunes, L.E.; Neves, M.L.R.; Ximenes, E.C.P.A.; Albuquerque, M.C.P.A. Gênero Candida – Fatores de virulência, Epidemiologia, Candidíase e Mecanismos de resistência. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e43910414283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Roca, B.; Rodrigues Poester, V.; Souza Mattei, A.; Klafke, G.B.; Ramis, I.B.; Xavier, M.O. Avaliação do uso da resazurina em teste de suscetibilidade in vitro frente a Sporothrix brasiliensis. Vittalle 2019, 31(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, A.; Mavridi-Printezi, A.; Mordini, D.; Montalti, M. Effect of size, shape and surface functionalization on the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mane, V.; Dake, D.; Raskar, N.; Sonpir, R.; Stathatos, E.; Dole, B. A review on Bi₂O₃ nanomaterial for photocatalytic and antibacterial applications. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 8, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, V.; Almaguer-Flores, A.; Velasco-Aria, D.; Díaz, D.; Rodil, S.E. Bismuth and Silver Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agent over Subgingival Bacterial and Nosocomial Strains. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, J.S.; Moreira, F.H.; Rosa, L.H.F.; Guerra, W.; Silva-Caldeira, P.P. Biological Activities of Bismuth Compounds: An Overview of the New Findings and the Old Challenges Not Yet Overcome. Molecules 2023, 28(15). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, K.; Lu, H.; Wu, D.; Chen, Z.; Lu, C. Antibacterial Properties and Mechanism of Lysozyme-Modified ZnO Nanoparticles. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 762255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Khafagy, E.S.; Riadi, Y.; Al Saqr, A.; Alfadhel, M.M.; Hegazy, W.A.H. Amphotericin B–PEG Conjugates of ZnO Nanoparticles: Enhancement Antifungal Activity with Minimal Toxicity. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14(8), 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankic, I.; Zelinka, R.; Ridoskova, A.; Gagic, M.; Pelcova, P.; Huska, D. Nano/microparticles in conjunction with microalgae extract as novel insecticides against Mealworm beetles, Tenebrio molitor. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignesh, K.; Sivaganesh, D.; Saravanakumar, S.; Prema Rani, M. Synthesis and characterisation of yittrium doped cerium oxide nanoparticles and their efficient antibacterial application in vitro against gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaraj, C.; Naveenkumar, S.; Satish Kumar, R.C.; Al-Ghanim, K.A.; Natesan, K.; Priyadharsan, A. Ice apple fruit peel assisted bio-synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs): An anticancer, antimicrobial, and larvicidal applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 105, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).