1. Introduction

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is one of the most common and debilitating inherited conditions in the US (~1 in 4,000 US births) [

1]. CF is an autosomal recessive multi-organ disease, caused by mutations in the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene [

1,

2]. The resulting dysfunction in CFTR protein leads to altered chloride transport across cell membranes. This causes less water to be attracted to the cell surface, causing the production of thick mucus in organs [

1]. In the lungs, this mucus blocks the airways, allowing bacteria to become trapped, inducing susceptibility to infections. Mucus buildup also causes pancreatic insufficiency, a condition where the pancreas’ ability to release digestive enzymes is attenuated. This causes diminished nutrient absorption, so babies fail to thrive. Some males with CF also suffer from infertility [

1]. Early treatment is critical to improve the quality of life and outcomes for CF patients.

The goal of the Iowa Newborn Screening Program (INSP) is to identify newborns at risk for inherited or congenital disorders to facilitate early interventions, so that the impact of these disorders is minimized. The INSP comprises 3 entities: (1) Iowa Health and Human Services (Iowa HHS) [

3], (2) The State Hygienic Lab at the University of Iowa (SHL) [

4] and (3) the University of Iowa Health Care Stead Family Department of Pediatrics (UIDP) [

5]. Iowa HHS has a memorandum of understanding with the SHL and UIDP. Together, these entities execute the goals of the INSP.

The SHL has stood at the front line of public health matters in Iowa (IA) since 1904. Blood spot screening is performed exclusively at SHL’s facility in Ankeny, IA, which runs a 365-day, two-shift operation. This means that the lab conducts testing on weekends, holidays and at night, making it the only public health lab with a dedicated night shift. In addition to IA, the SHL conducts NBS testing for the states of Alaska (AK), North Dakota (ND) and South Dakota (SD) which are all one-screen states. The INSP’s follow-up team, medical consultants and genetic counsellors are associated with the UIDP, which is in Iowa City, IA.

The INSP utilizes a 3-tier testing algorithm to screen for cystic fibrosis: (1) Immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) [

6,

7] with a fixed cutoff (≥58 ng/mL), (2) samples over this cutoff are reflexed to CFTR DNA screening [

6,

7] which is run by the day-shift staff only and (3) Sanger sequencing used only if 2

nd-tier results are inconclusive or require additional clarification (performed by the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene). Approximately ~130 samples/ month are reflexed to CFTR DNA analysis.

In 2022, the INSP, along with the state coordinators and pulmonologists of AK, ND and SD, agreed to the expansion of SHL’s CFTR panel. At that time, our “old test” was a lab developed, qualitative genotyping assay using custom microfluidic cards. The desired variants were selected and the “expanded” 42-variant panel was ordered from the vendor in July 2022, to replace our “limited” 25-variant panel.

We immediately observed issues with the expanded panel. There were noticeable differences in test performance between the limited and expanded panels, then we noticed physical anomalies in the expanded panel’s microfluidic cards. Workarounds for these problems became too numerous and unsustainable, so the new variant panel could not be validated in accordance with SHL standards. The vendor could not rectify the issue, and with the exhaustion of the limited panel looming, the SHL suddenly and unexpectedly lost our ability to perform in-house CFTR DNA analysis. This prompted us to send samples for CFTR DNA analysis to reference laboratories, while we sourced a new assay.

Our efforts to implement the new test however, faced unexpected setbacks related to logistical and technical issues and delays for quotes and contracts. The fallout from these delays affected many functional aspects of the INSP including a significant decrease in our timeliness, additional fees for reference labs, shipping fees, delayed reports, additional hours for staff, and staff frustration and stress. Below we describe the strategies taken to resume in-house CFTR DNA testing while also ensuring that CFTR screening for AK, IA, ND and SD babies was uninterrupted.

2. Methods

2.1. SHL Assured Uninterrupted CFTR DNA Testing in Two Phases

2.2. Phase 1: Ensuring Continued CFTR DNA Testing of NBS Samples

2.2.1. Decision to Change Vendor and Test

This extensive process began by contacting our vendor when issues with the old test’s expanded panel were discovered. Numerous troubleshooting exercises were performed by the lab and vendor. Unfortunately, the vendor could not offer a solution or the assurance that the problems would not reoccur. Our limited panel was nearly exhausted, so we were left without an operational CFTR DNA assay. The SHL then determined that the risk of the problems reoccurring was too high, so we made the decision to (1) shut down in-house testing, (2) send samples to a reference laboratory and (3) replace our CFTR DNA test.

2.2.2. Reference Labs

To guarantee the seamless continuation of testing, reference lab testing was organized prior to the exhaustion of the limited panel. Over the course of 9.5 months, we utilized 3 different state labs (consecutively), as their capacity allowed (Minnesota: Oct-Nov 2022, Missouri: Nov-Feb 2023 and Indiana: Feb-Aug 2023). The following tasks were coordinated:

Enactment of existing memoranda of understanding (MOUs)/ contracts and the establishment of new agreements. This involved the legal teams of both entities, to determine the contract’s length (e.g. 1 year), renewal date, and the duration of testing.

Agreement on the price of testing per sample and whether repeat testing (to confirm detected variants) was an additional charge.

Obtained information on the reference lab’s assay and variant panel.

Decided on the sample type to be sent (whole blood spots vs. punches).

Ascertained the reference lab’s testing schedule, agreed on a preferred carrier and created a compatible shipping schedule (amended during holidays).

Organized the secure delivery of reports and the return of residual blood spots to the SHL.

Entities exchanged the email addresses of staff involved in testing to ensure redundancy in the receipt of samples, results and correspondence.

2.2.3. Internal SHL Preparations

A deliberate decision was made to ensure that all reference labs used the same test/ panel, to minimize the impact on our patient reports, database and standard operating procedures (SOPs).

SHL IT personnel updated our LIMS to reflect the variants on the reference lab’s panel.

We amended patient reports to indicate that CFTR DNA analysis was performed at a reference lab (address and CLIA number included).

Shipping SOPs were revised, and shipping fees were calculated.

Lab and follow-up SOPs were updated, and staff were trained accordingly.

2.2.4. Notifying Clients About Reference Labs (see Table 1).

The initial communication was sent in October 2022, to the state coordinators of AK, IA, ND, and SD, seeking approval for their samples to be tested by a non-SHL lab, as required contractually.

The second major communication was to birthing facilities in Jan 2023. Owing to the increased turnaround time (TAT) for CFTR DNA results, the timeliness of patient reporting was delayed, resulting in a significant increase in call volume. To address this, the SHL crafted a letter explaining the delays, that accompanied reports.

The last major communication was in Aug 2023 to inform clients of the resumption of SHL’s in-house CFTR testing.

In addition to these communiqués, CFTR assay challenges were routinely discussed among the four states at our monthly ‘Quad state’ meeting.

Table 1.

Core contents of SHL correspondence to clients.

Table 1.

Core contents of SHL correspondence to clients.

| Contents Of Communication |

Recipient(s) |

| A concise and straightforward explanation of the problem and that halting in-house testing was a necessary but temporary measure to ensure reliable test results |

All Clients |

| Reassurance that SHL would implement a stable, robust and reliable alternative |

All Clients |

| A request by SHL, for approval to send samples to reference lab(s) |

AK, IA, ND & SD state partners |

| Information on the use of a reference lab to perform CFTR DNA testing |

All Clients |

| A list of variants on the reference lab’s panel |

AK, IA, ND & SD state partners |

| An explanation of the decreased timeliness of patient reports awaiting CFTR DNA results |

Birthing Facilities |

| Assurance that critical result reporting remained unaffected |

Birthing Facilities |

| Explanation of SHL’s ongoing efforts to resolve issues |

All Clients |

| Resumption of in-house testing and SHL’s appreciation of clients’ patience and understanding |

AK, IA, ND & SD state partners |

2.3. Phase 2: Implementing the New Test.

2.3.1. The SHL Identified Four Main Attributes Required for the New CFTR DNA Test: Robustness, Reliability, a Good Track Record, and the Trust of Labs in the NBS Community

2.3.2. Networking and Market Research:

This began in Oct 2022 at the APHL NBS screening symposium and allowed the SHL to meet with vendors and state labs performing CFTR DNA analysis. This exercise yielded three viable options. After follow-up meetings with vendors and examining the feedback from various state labs, only one vendor met our requirements, and a demonstration of the test at an experienced state lab was conducted in Nov 2022.

In Dec 2022, SHL selected a 39-variant CFTR DNA test, with patented technology that utilizes PCR & flow cytometry.

The SHL relayed the urgency of test implementation to the vendor of the new test. Both parties agreed on a Feb 2023 completion deadline and developed a plan of action for: (1) quotes and contracts, (2) instrument procurement and service contracts, (3) purchase of auxiliary equipment and consumables, (4) reconfiguration of lab space, (5) instrument installation, (6) test validation and (7) staff training. The SHL also requested that these documents be given priority by University of Iowa departments (legal, accounting, procurement services), for expedited document reviews.

2.3.3. Resolving the Issues Resulting from Delayed Test Implementation:

Despite our extensive planning, test implementation was not completed within the expected timeframe due to delays in: quotes and contracts, logistics (instrument procurement/ shipment), and technical issues.

After equipment installation and training, the lab experienced technical problems that delayed test implementation, so we requested technical assistance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) National Centers for Environmental Health, Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch [

8] and other public health labs.

3. Results

Various strategies were employed to mitigate the impact of CFTR assay challenges.

Effective Communication with Clients and Vendors

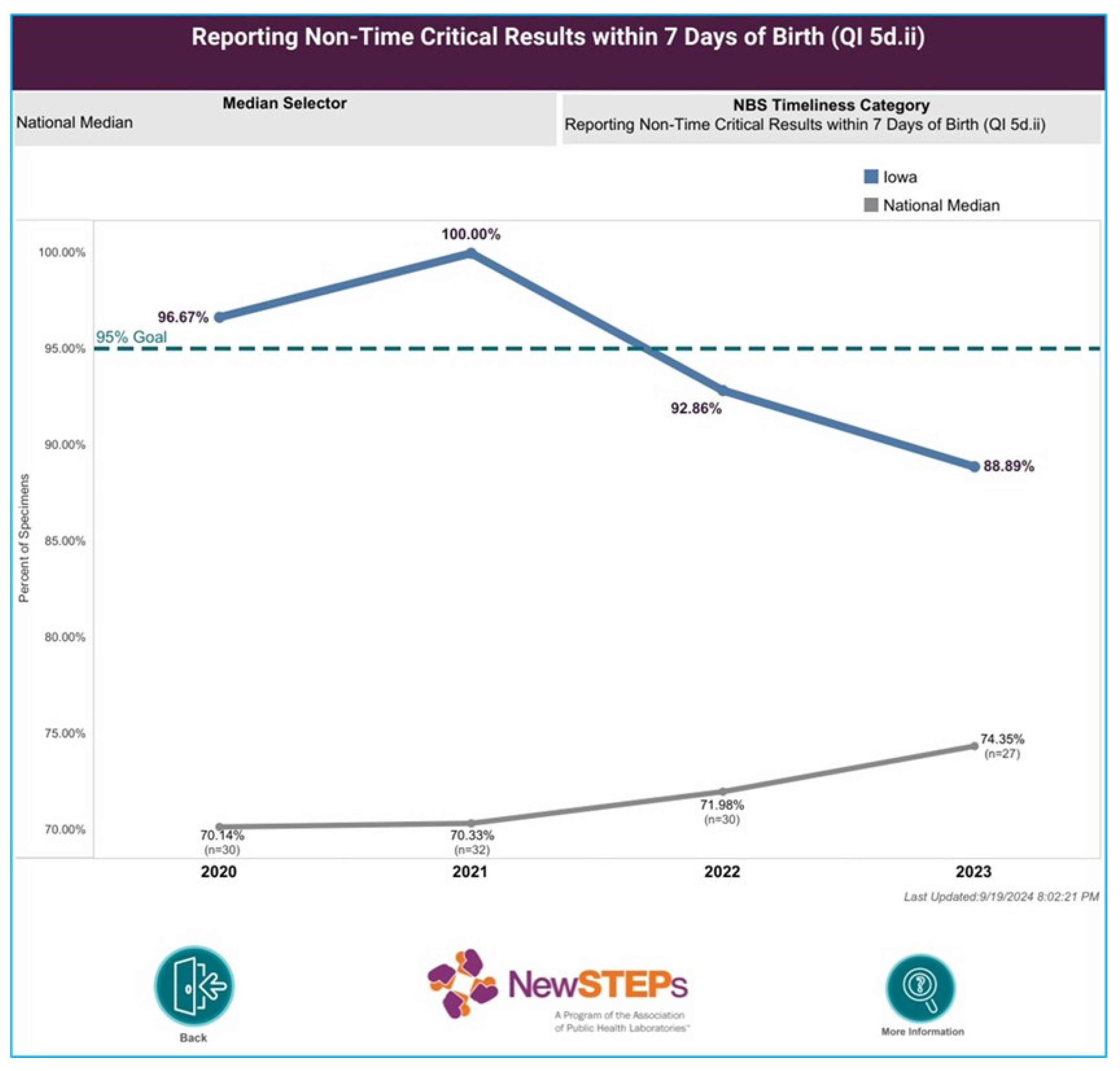

The most consequential outcome of paused in-house testing, was a significant decrease in our timeliness, as reflected in Iowa’s NewSTEPs [

9] report for non-time critical results (

Figure 1). This necessitated continuous communication with our clients.

While a necessary process, shipping samples to referral labs became a limiting factor, because it influenced when samples could be tested by the reference lab, according to its testing schedule. In many cases, thanks to the next-day delivery service, samples would be tested on the day of delivery or the following day. However, this could be affected by various factors such as delayed delivery, holiday/ long weekends, instrument issues or the referral lab’s workload etc. Sample logistics added approximately 2-4 days onto our TAT in 2022 to 2023 compared to previous years, and the average TAT for CFTR results from birth to reporting (non-critical results) was 9 days in 2023.

Our decreased timeliness in turn, caused a significant uptick in call volume from clinics and community providers. Accustomed to timely reports, clients called to inquire about delayed reports and were informed that CFTR results were still pending. Between the follow-up team and the lab’s client services team, there were approximately 4-6 such enquiries per week. The lab’s letter to birthing facilities (

Table 1), calls and emails with clients alleviated the situation. However, a return to normal call volumes was only achieved when in-house testing resumed, which improved our TAT for CFTR results (5 days on average in 2024).

Another effective communicating medium was our monthly “Quad state” meeting that is held virtually, to discuss topics that affect the four states. Attendees included the AK, IA, ND and SD NBS state coordinators, SHL leadership, lab and IT personnel, follow up, the INSP Medical Director and other NBS personnel on an ad hoc basis. This medium allowed SHL to provide answers and updates on CFTR assay challenges, to a broad range of clients all at once.

In addition to clients, SHL staff regularly liaised with vendors to report testing issues, seek updates and work towards swift resolutions. During troubleshooting of the problems with the old test and during delays in new test implementation, SHL staff reiterated the matter’s urgency and that it was causing the lab to incur additional costs for reference lab fees and shipping. This ensured that issues remained a primary focus of the vendors.

SHL Utilized in-House and External Technical Expertise to Resolve CFTR Assay Issues

While the SHL performed vendor- recommended troubleshooting exercises to resolve assay issues (old and new test), they did not always resolve the problems we experienced. Therefore, the lab enacted two concurrent strategies. Firstly, we conducted our own controlled troubleshooting experiments. Secondly, we consulted external experts for technical assistance who provided an invaluable injection of fresh ideas, assay SOPs, QC samples, assay experience and guidance.

These two strategies were vital, especially during new test implementation, as we overcame the many hurdles that caused the delay and successfully launched the new test which met our needs (

Table 2). Immediately after the launch of our new CFTR DNA assay, the SHL received a Molecular Assessment Program (MAP) visit [

10] from the CDC, which provided invaluable quality assurance oversight.

Staff Initiative and Collaboration with the NBS Community Helped Resume in-House Testing

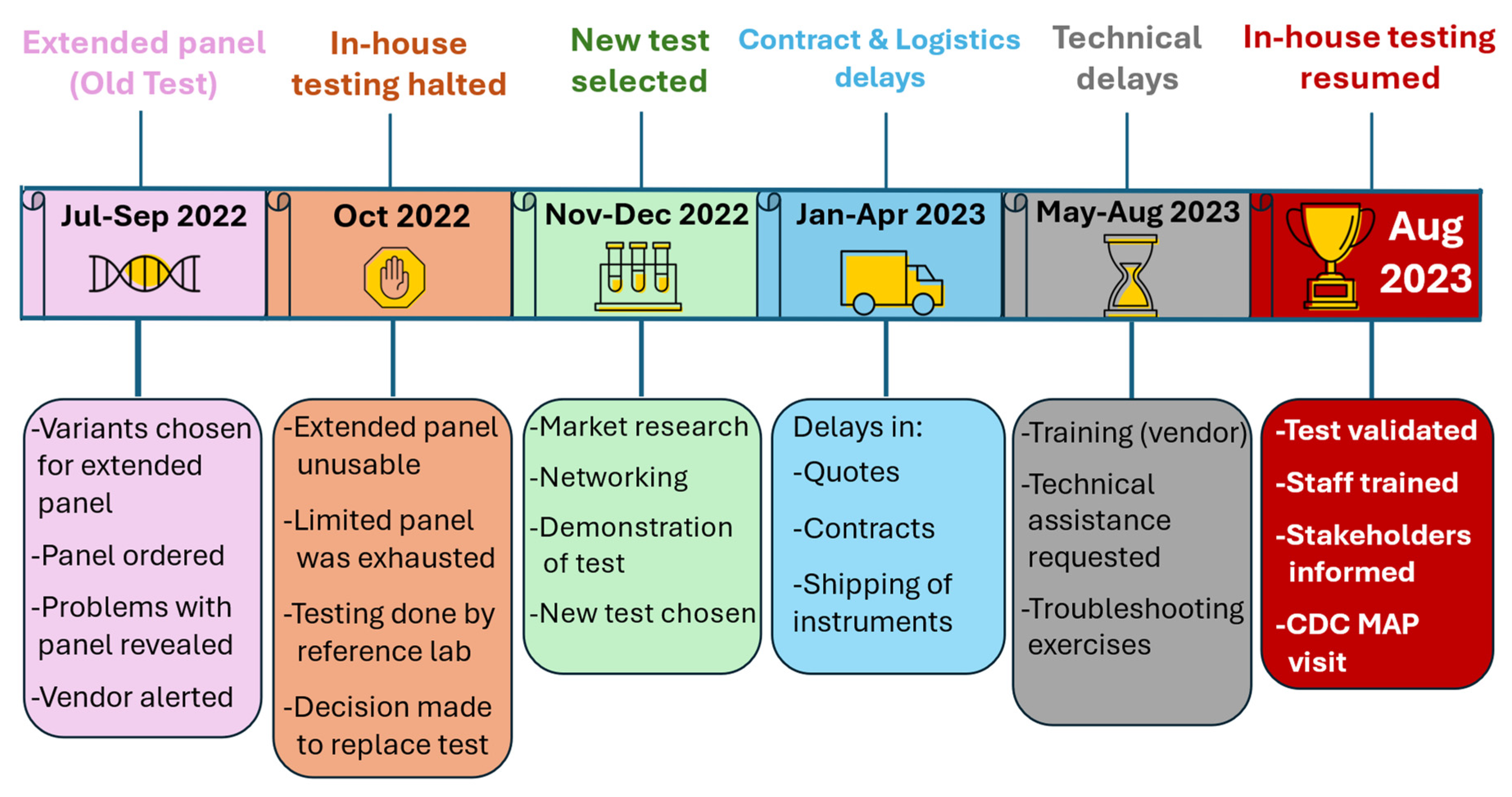

INSP staff (lab staff, follow-up, genetic counsellors and Medical Director) regularly went above and beyond when solving problems and providing excellent customer service. SHL staff, who bore the responsibility of test implementation, were committed, creative, persistent, resilient and calm when facing challenges. Thanks to these combined efforts, in Aug 2023, in-house testing resumed after 9.5 months (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Two major events affected CFTR DNA testing at the SHL from 2022-2023: the nonperformance of our lab-developed testing (LDT) and the prolonged implementation of its replacement. However, we also experienced triumphs, unforeseen benefits and learned many valuable lessons.

Our greatest success, however, was preventing mass panic across four states. During any tumultuous period, the tone and contents of correspondence are vital factors in relaying a message adeptly, while maintaining calm. SHL’s correspondence with clients was clear, concise, honest, and informative, while retaining an appreciative and optimistic tone (

Table 1). Conversely, when pursuing resolutions to problems, the lab’s correspondence with vendors was cordial and respectful, but was also persistent and always highlighted the impact of delays on our TAT and the fees associated with protracted use of reference labs.

The feedback received from clients was positive, making this approach successful. Clients reported that they were appreciative of regular updates, prompt responses to questions, the SHL’s decisive decision making and supplemental progress report updates. Another vital factor was the relationship between the SHL and its ‘Quad State’ partners. This special and close-knit alliance often resembles that of a family, more than that of contractor and contractee. The impact of the compassion, understanding and empathy extended to SHL staff was profound and of immeasurable value.

The new test’s delay also provided a silver lining. By utilizing referral labs running the same test we laterer adopt, the SHL was afforded a bird’s eye view of the test’s capabilities, data analysis procedures and other features. Moreover, SOPs from state labs gave us insight into how different labs resolved test- specific issues. This gave us an advantage when formulating our own SOPs and test workflows. For instance, we observed a rare testing event experienced by some reference labs, that caused inconclusive results, so we introduced Sanger sequencing as a 3rd- tier test (done by the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene) to prevent potential delays to our TAT, should it occur in-house.

Another strength was our ability to trust our own expertise and seek external assistance/ oversight. In particular, the CDC [

8] was an intermediary during SHL’s outreach with reference labs and together they provided invaluable technical knowledge during our troubleshooting efforts. Furthermore, days after launching the new test, the CDC provided further technical oversight of both the new test and the SHL’s NBS Molecular section via a MAP visit [

10]. This exercise highlighted continuous quality improvement opportunities and reassured the lab and its stakeholders, of good test performance and the quality of results. The role of partnership and collaboration within various NBS entities is a theme of this work that cannot be overstated. The NBS community is very collaborative, and because of this, the SHL did not hesitate to seek assistance.

Nevertheless, despite our best efforts, there were issues that we could not resolve. The slower TAT while in-house testing was paused, and the expense of reference lab fees were unavoidable. With the benefit of hindsight, the SHL examined many of its processes, identified areas for improvement and learned many beneficial lessons. Firstly, our established MOU with the MN state lab allowed prompt coordination of testing, so the SHL has built upon this, by maintaining the MOUs with the other reference labs. Secondly, the SHL’s emergency preparedness policies and procedures are under review.

While our second-tier CFTR DNA test was paused, first-tier IRT testing remained unaffected, so it was not a triggering event for the INSP’s Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP) [

11]. Also, this scenario was not specifically outlined in the SHL’s Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) plan. Subsequently, unlike other SHL partners, birthing facilities were not immediately alerted in Oct 2022 when in-house CFTR DNA testing was paused. To address this oversight, the SHL has expanded its COOP team to include personnel involved in resolving CFTR testing issues, to gain fresh perspectives and identify additional blind spots in existing policies.

Lastly, the importance of good vendor relationships to emergency preparedness was highlighted. SHL has revamped its strategies for handling vendor-related issues, so that they are swiftly escalated to SHL administration, who can intervene faster to advocate for the lab and staff.

The NBS landscape is on the cusp of major metamorphosis. Advancements in therapies and testing methodologies have resulted in the addition of more tests to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) [

12] now more than at any time previously. Also, the utility of next generation sequencing in NBS is already being examined [

13,

14]. For CF screening specifically, guidelines and initiatives like those supported by the Cystic Fibrosis foundation may be an impetus for NBS programs to incorporate sequencing into their algorithms, to expand the number of CFTR variants identified [

15,

16]. In conclusion, we have outlined how best laid plans can be derailed by unforeseen obstacles. The strategies employed and lessons learned by the SHL can serve as a useful roadmap on how to prepare for and navigate rough waters amidst an unexpected ‘storm’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; methodology, J.A. and K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, C.C., K.N.P., and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Per the Human Subjects Office of the University of Iowa, the project does not meet the regulatory definition of human subjects research and does not require review by the IRB, because there is no access to identifiable patient information as part of this project, and no generation of generalizable knowledge.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author Jerusalem Alleyne at jerusalem-alleyne@uiowa.edu.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge SHL staff for their efforts to restore in-house CFTR DNA testing. We would also like to thank INSP staff and the NBS state coordinators of AK, ND and SD. We also acknowledge the INSP’s former follow-up program coordinator Carol Johnson, for her guidance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

Intro to CF | Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. https://www.cff.org/intro-cf (accessed 2025-06-19).

- Rock, M. J.; Baker, M.; Antos, N.; Farrell, P. M. Refinement of Newborn Screening for Cystic Fibrosis with next Generation Sequencing. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58 (3), 778–787. [CrossRef]

-

Iowa Newborn Screening Program | Health & Human Services. https://hhs.iowa.gov/programs-and-services/family-health/congenital-inherited-disorders/iowa-newborn-screening-program (accessed 2025-06-19).

-

State Hygienic Laboratory | The University of Iowa. https://shl.uiowa.edu/ (accessed 2025-06-19).

-

Stead Family Department of Pediatrics | Carver College of Medicine | The University of Iowa. https://pediatrics.medicine.uiowa.edu/ (accessed 2025-06-19).

- Castellani, C.; Massie, J.; Sontag, M.; Southern, K. W. Newborn Screening for Cystic Fibrosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4 (8), 653–661. [CrossRef]

- ravert, G.; Heeley, M.; Heeley, A. History of Newborn Screening for Cystic Fibrosis—The Early Years. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6 (1), 8. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Newborn Screening Home. Newborn Screening. https://www.cdc.gov/newborn-screening/index.html (accessed 2025-06-19).

-

Home | NewSTEPs. https://www.newsteps.org/ (accessed 2025-06-19).

-

APHL. APHL. http://www.aphl.org (accessed 2025-06-19).

- Olney, R. S.; Bonham, J. R.; Schielen, P. C. J. I.; Slavin, D.; Ojodu, J. 2023 APHL/ISNS Newborn Screening Symposium. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9 (4), 54. [CrossRef]

-

Recommended Uniform Screening Panel | HRSA. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/rusp (accessed 2025-06-19).

- Jeanne, M.; Chung, W. K. DNA Sequencing in Newborn Screening: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71 (1), 77–86. [CrossRef]

- iegler, A.; Koval-Burt, C.; Kay, D. M.; Suchy, S. F.; Begtrup, A.; Langley, K. G.; Hernan, R.; Amendola, L. M.; Boyd, B. M.; Bradley, J.; Brandt, T.; Cohen, L. L.; Coffey, A. J.; Devaney, J. M.; Dygulska, B.; Friedman, B.; Fuleihan, R. L.; Gyimah, A.; Hahn, S.; Hofherr, S.; Hruska, K. S.; Hu, Z.; Jeanne, M.; Jin, G.; Johnson, D. A.; Kavus, H.; Leibel, R. L.; Lobritto, S. J.; McGee, S.; Milner, J. D.; McWalter, K.; Monaghan, K. G.; Orange, J. S.; Pimentel Soler, N.; Quevedo, Y.; Ratner, S.; Retterer, K.; Shah, A.; Shapiro, N.; Sicko, R. J.; Silver, E. S.; Strom, S.; Torene, R. I.; Williams, O.; Ustach, V. D.; Wynn, J.; Taft, R. J.; Kruszka, P.; Caggana, M.; Chung, W. K. Expanded Newborn Screening Using Genome Sequencing for Early Actionable Conditions. JAMA 2025, 333 (3), 232. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, M. E.; Raraigh, K. S.; Farrell, P.; Shropshire, F.; Padding, K.; White, C.; Dorley, M. C.; Hicks, S.; Ren, C. L.; Tullis, K.; Freedenberg, D.; Wafford, Q. E.; Hempstead, S. E.; Taylor, M. A.; Faro, A.; Sontag, M. K.; McColley, S. A. Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening: A Systematic Review-Driven Consensus Guideline from the United States Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11 (2), 24. [CrossRef]

- Dwight, M.; Faro, A. It Takes All of Us: How the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Is Supporting States in Advancing Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11 (2), 39. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).