1. Introduction

Inborn Errors of Metabolism (IEM) represent a group of inherited disorders characterized by defects in various biochemical metabolic pathways. Many of these conditions manifest clinically during the early neonatal period, with signs and symptoms often resembling neonatal sepsis, making accurate diagnosis challenging. Failure to diagnose these conditions timely can lead to poor outcomes, including increased infant mortality and long-term disabilities.

Newborn screening (NBS) for IEM began with phenylketonuria (PKU), first reported by Dr. Robert Guthrie in 1961 [

1]. Since then, screening programs have expanded to include other IEMs and various other conditions. Today, expanded NBS for IEMs via tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is a powerful tool for early diagnosis, widely implemented in many developed countries.

In Thailand, NBS was first piloted in 1993 and became mandatory nationwide in 1996, covering two conditions: congenital hypothyroidism (CH) and PKU [

2]. In 2014, Liammongkolkul et al [

3]. piloted a study at Siriraj Hospital, introducing expanded NBS for 40 IEMs. This project screened 99,234 neonates born in 15 public hospitals in Bangkok and reported an incidence of 1 in 6,616 births (or 1 in 12,404 births if cases due to affected mothers were excluded).

In 2022, Thailand’s National Health Security Office (NHSO) approved a benefit package covering the diagnosis and treatment of 24 rare IEMs, providing universal health coverage for Thai citizens. Subsequently, seven Rare Disease (RD) centers were established, with six located in Bangkok metropolitan region and one at Srinagarind Hospital in Khon Kaen, northeastern Thailand. The Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) conducted an economic evaluation and feasibility study of expanded NBS using MS/MS. The results showed that early treatment, prior to the onset of symptoms, is cost-effective compared to late treatment, and recommended the NHSO include expanded NBS with MS/MS technology under the Universal Coverage Scheme [

4].

Following HITAP's recommendations, the expanded NBS program for all Thai neonates was launched in October 2022. Ten NBS centers were established, covering all 13 health regions across the country. Srinagarind Hospital serves as both a RD center and a NBS center, overseeing health regions (HR) 7 and 8 in northeastern Thailand, responsible for more than 50,000 births annually across 11 provinces.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Development and Validation

The Srinagarind Excellence Center Lab (SEL), the Genomics and Precision Medicine Laboratory, in collaboration with the Center of Excellence in Precision Medicine, and Division of Medical Genetics Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen University serves as the main unit responsible for the NBS service. The GSP Neonatal hTSH kit is used for TSH screening by DELFIA assay and NeoBase 2 Non-derivatized MSMS kit is used for IEMs screening through MS/MS. The target disorders for IEMs demonstrated in

Table 1.

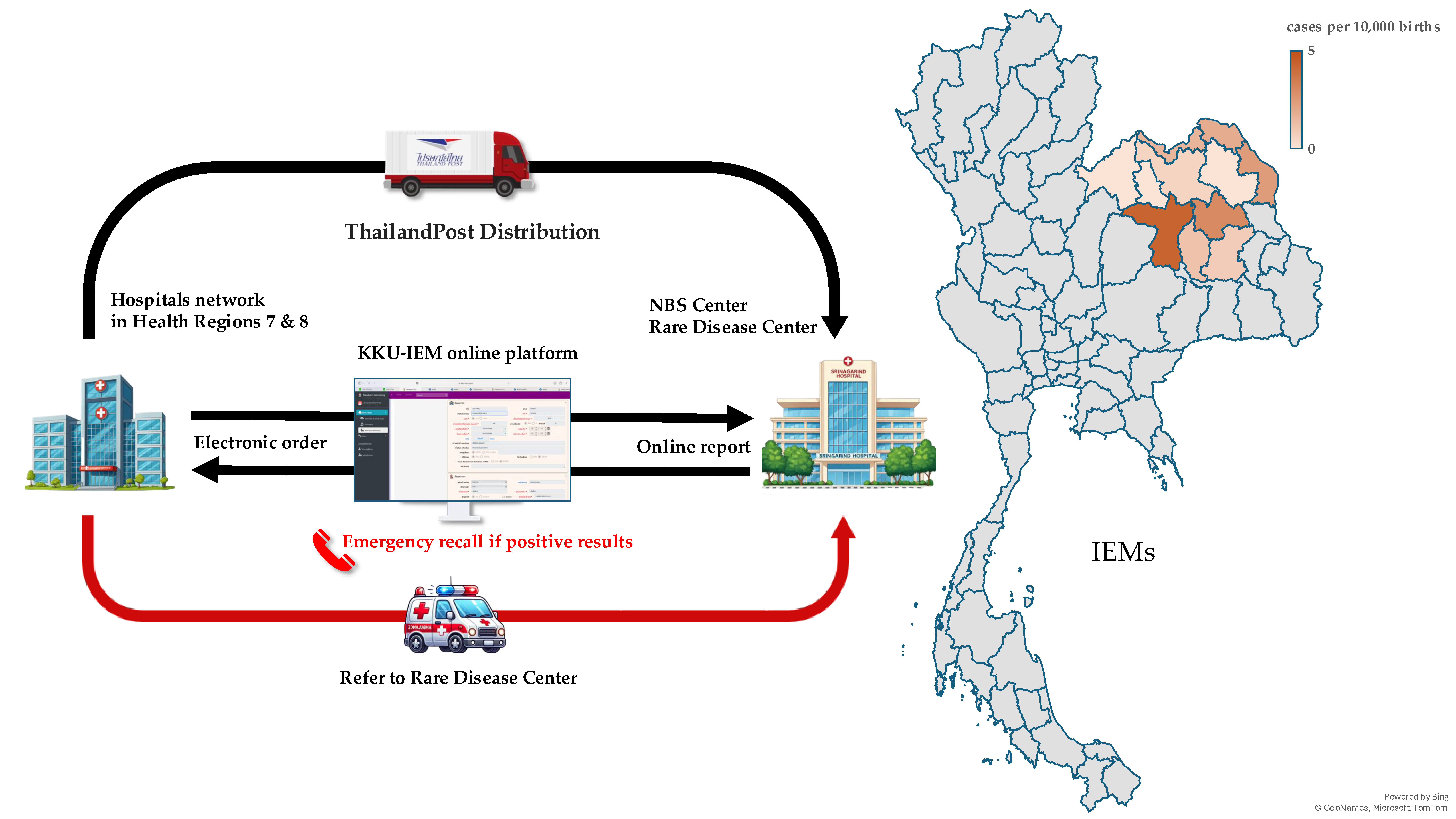

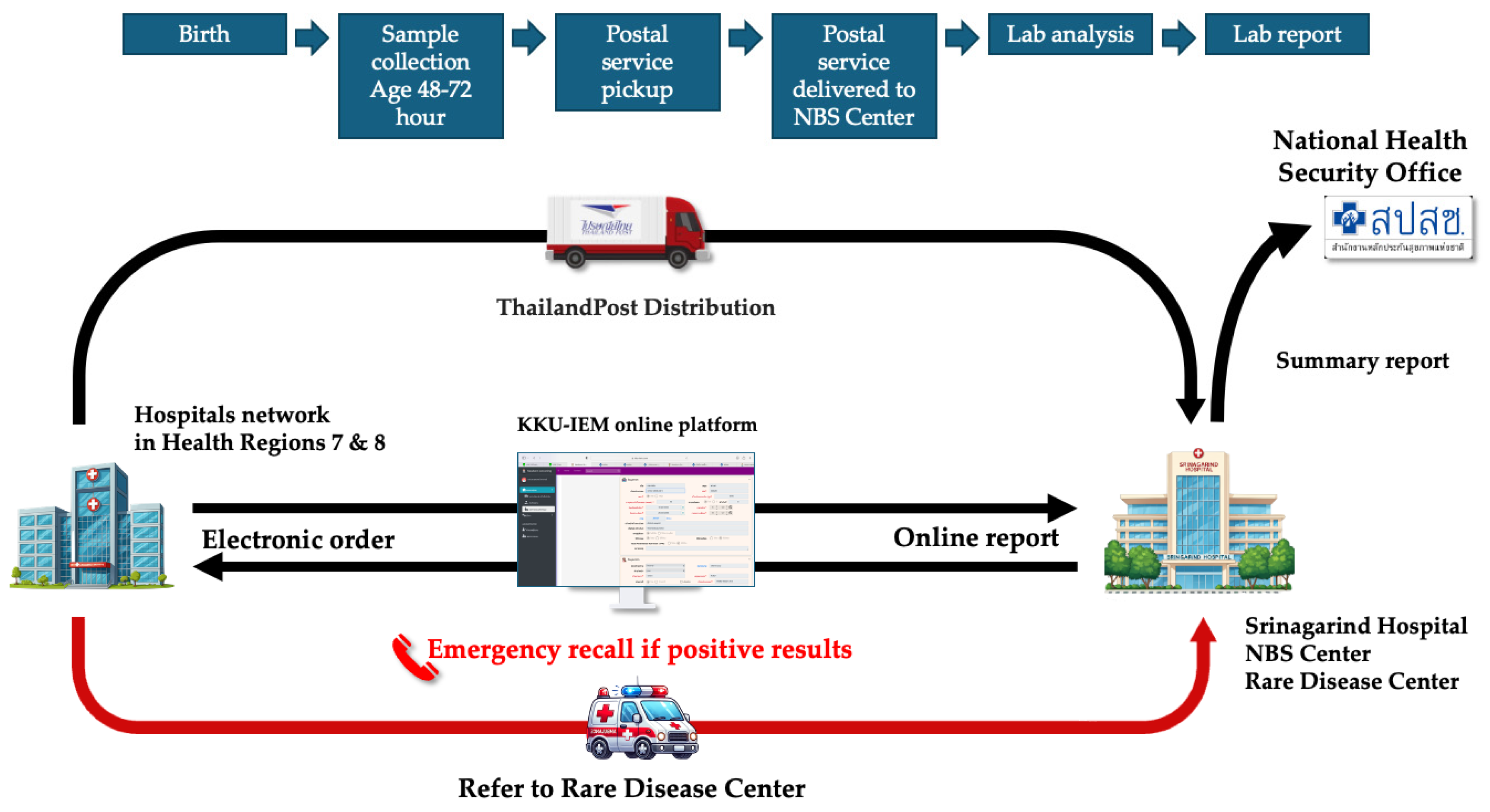

Over 2,000 blood spot samples were used for validation, and initial setting-up the cutoff values for TSH and MS/MS analysis. Simultaneously with process of validation, the workflow system was developed based on lean concept to minimize human error. The online platform was developed to facilitate through the process since registration, electronic ordering, logistics, interpretation and reporting. The workflow system was demonstrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Software and Logistics Preparation

Since NBS requires collaboration with many hospitals, a software system was developed to facilitate data exchange and reporting. The KKU-IEM web-based online platform (

www.kku-iem.com) was created to record newborn and maternal data, sample information, and track sample status in real-time from data entry to sample shipment, laboratory receipt, and result reporting. The system generates lab numbers and barcodes for each sample, streamlining laboratory operations. Individual and hospital-specific reports can be printed, with access restricted via username and password for each coordinator in each hospital. Data retrieval and export for analysis or submission to the NHSO is also supported. In terms of logistics, the service partnered with Thailand Post Distribution (TPD) to collect samples from all hospitals daily. Once the KKU-IEM platform records a shipment, Thailand Post collects the samples and delivers them to the NBS center.

2.3. Training of Networks

Nurse, doctor and medical technologist coordinators from each network hospital are assigned for collaborate with the NBS lab in Srinagarind Hospital. Prior to the launch of services, workshops were conducted with hospitals network in HR 7 (Four provinces including Kalasin, Khon Kaen, Maha Sarakham and Roi-Et) and HR 8 (Seven provinces including Bueng Kan, Loei, Nakhon Phanom, Nong Bua Lamphu, Nong Khai, Sakon Nakhon and Udon Thani). These sessions provided training on sample collection, electronic registration through the KKU-IEM platform, sample tracking, recalling infants with positive results, evaluating the affected infants, and consulting the geneticist at Srinagarind Hospital (RD center) for further management in accordance with established guidelines. To ensure smooth operations, online meetings and site visits were organized to gather stakeholder feedback, address issues, and implement system improvements.

All newborns are recommended to undergo NBS with blood collection at 48–72 hours of age. For preterm or low-birth-weight infants, a second NBS is recommended at 2–3 weeks of age. If the results are positive, a nurse coordinator or medical geneticist will inform the network hospital coordinator for recalling the patient for evaluation.

The screened diseases were categorized into two groups based on urgency:

1. Very Urgent: Infants must be followed up for evaluation within 24 hours of receiving a positive result.

2. Urgent: Infants must be followed up for evaluation within 48 hours of receiving a positive result.

The classification of diseases is detailed in

Table 1.

To facilitate effective communication, multiple channels were established between network hospitals and the NBS center. A dedicated Line official account, NB Screening KKU, was created to handle inquiries, blood filter papers requests, and service updates. The account also features a menu with detailed program instructions and guidelines for proper blood sample handling.

Additionally, direct contact numbers for the pediatric geneticist and the NBS laboratory were provided, along with email communication channels to ensure accessibility. Comprehensive screening protocols and follow-up procedures for managing abnormal results were also established to streamline the process and ensure timely interventions.

2.4. Quality Control

The cut-off was reevaluated at 6 and 12 months after implementation with 10,000 and 50,000 samples, respectively. An inter-lab comparison project was established among three NBS centers: Srinagarind Hospital, Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health, and Siriraj Hospital. Furthermore, the center joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for proficiency testing and external quality control to ensure the quality of laboratory analyses. The lab also received international accreditation for ISO 15189 and ISO 15190 standards (currently accredited).

2.5. Re-Evaluation

We set up internal evaluation every quarter of year regularly and a comprehensive annual performance report. The report outlines the results of NBS throughout the fiscal year, reviews operational practices, reflects on issues encountered during implementation, and provides a platform for knowledge exchange with hospital network. It also includes listening to suggestions, conducting a satisfaction survey, and exploring opportunities for improvement, particularly in reducing the time it takes to report results so that infants can receive diagnoses faster.

An online video clip about the NBS system at Srinagarind Hospital was created to communicate the importance and procedures of NBS to the public. Continuous improvements were made to the KKU-IEM web program, and the results report form was revised to be more user-friendly, making the work easier for both service units and the screening laboratory. Knowledge management and sharing with other NBS centers was setting up as annual conference.

3. Results

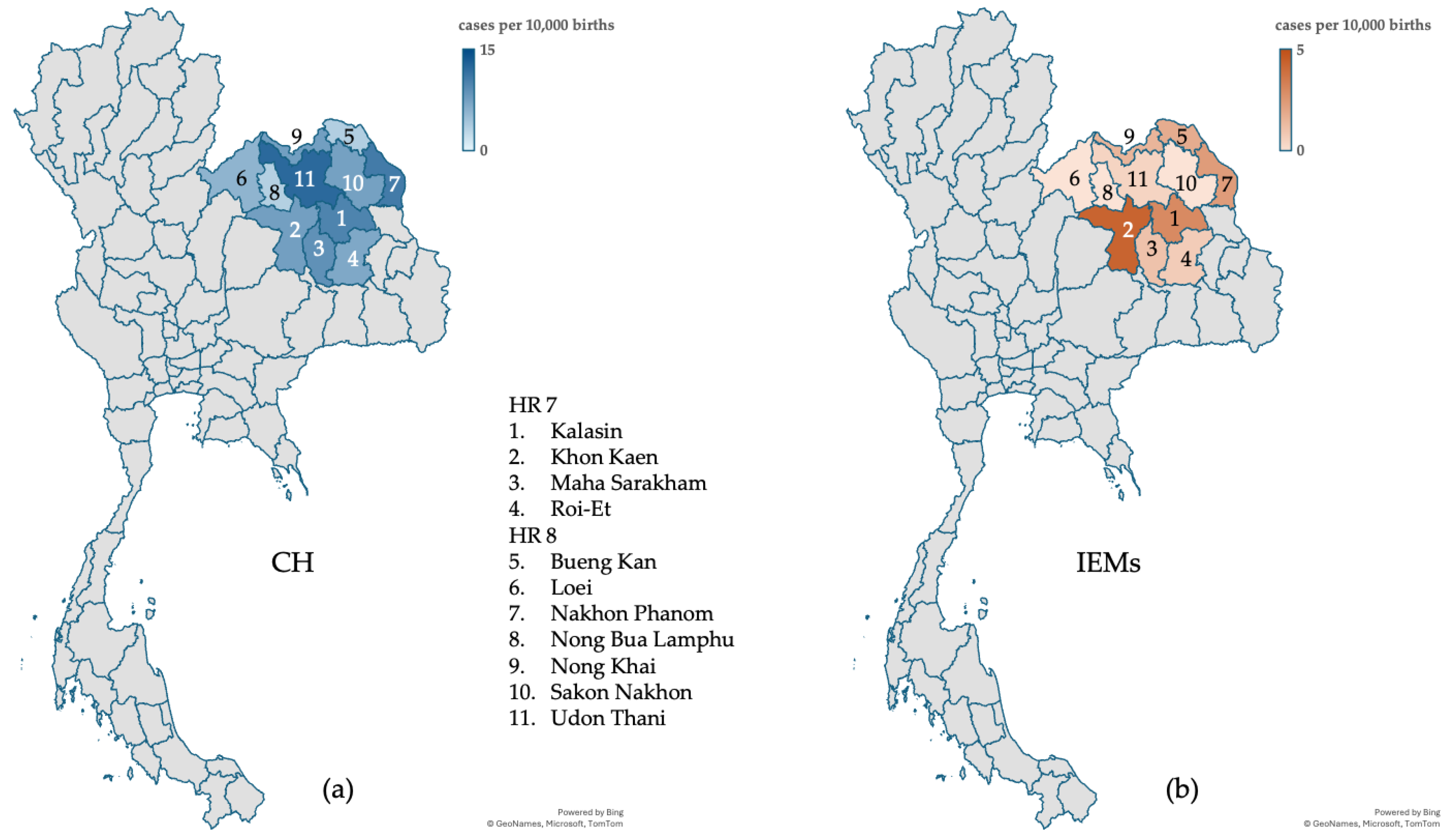

The NBS network comprised 169 hospitals (79 in HR 7 and 90 in HR 8). All network hospitals utilized the KKU-IEM web-based platform for electronic online ordering. From October 2022 to September 2024, there were 123,692 live births in these regions (12.4% of a whole country), of which 122,004 newborns (98.6%) underwent screening. Among them, 12,164 were preterm, and 13,179 were low birth weight newborns. Second NBS was performed on 11,138 infants (9.1%).

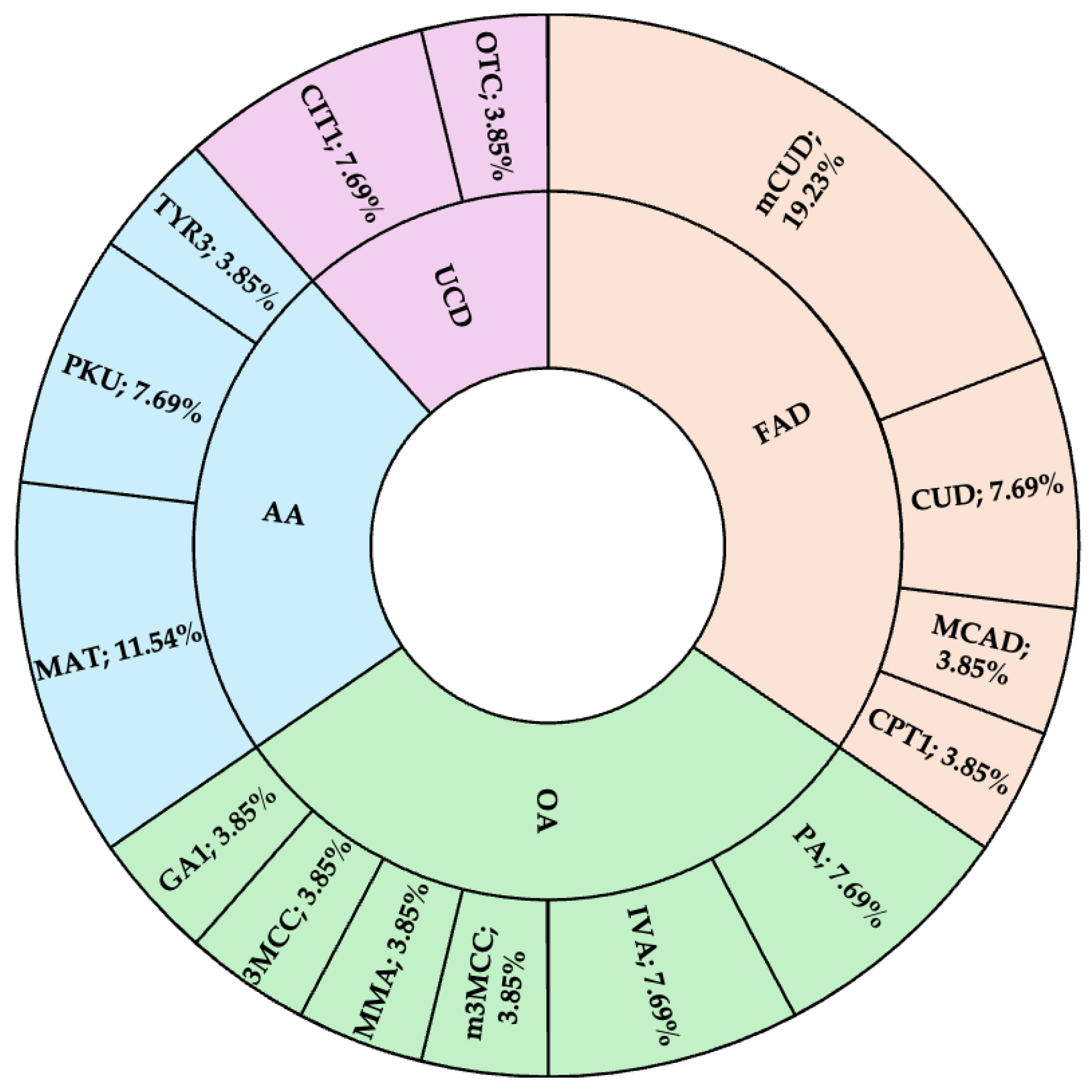

Abnormal screening results included 287 newborns positive for TSH and 529 newborns positive for IEMs. The recall rates were 1 in 425.1 for TSH and 1 in 230.6 for IEMs. The successful follow-up rates for confirmatory testing were 99.0% for newborns with positive TSH results and 96.0% for those with positive IEM results. A total of 101 neonates were confirmed to CH by abnormal

thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) or free

thyroxine (T4) in serum, with an incidence of 1 in 1,208 live births. Additionally, 20 neonates were diagnosed with IEMs, corresponding to an incidence of 1 in 6,100 live births (or 1 in 4,692 births if cases due to affected mothers were included). Maternal conditions (maternal carnitine uptake defect and maternal 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency) affecting NBS results were identified in 6 neonates with positive results. These findings are summarized in

Table 2. The incidence rates were display on the geographic maps in

Figure 2. The IEMs found in the NBS program demonstrated in

Figure 3.

In the fiscal year 2024 (October 1st, 2023, to September 30th, 2024), the expanded NBS program for IEMs achieved nationwide coverage in Thailand. Data collected from all Rare Disease Centers revealed an incidence rate of 1 in 7,433 live births among a total of 475,744 newborns. A total of 64 cases were confirmed with a diagnosis of any one of IEMs. Ten of these cases resulted in mortality, with diagnoses including tyrosinemia type 1 (1 case), citrullinemia type 1 (3 cases), isovaleric aciduria (1 case), carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency (3 cases), very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency (1 case), and multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (1 case). The overall mortality rate across the country was 15.6% of confirmed cases, compared to 8.3% observed in HR 7 and 8 (1 case with citrullinemia type 1).

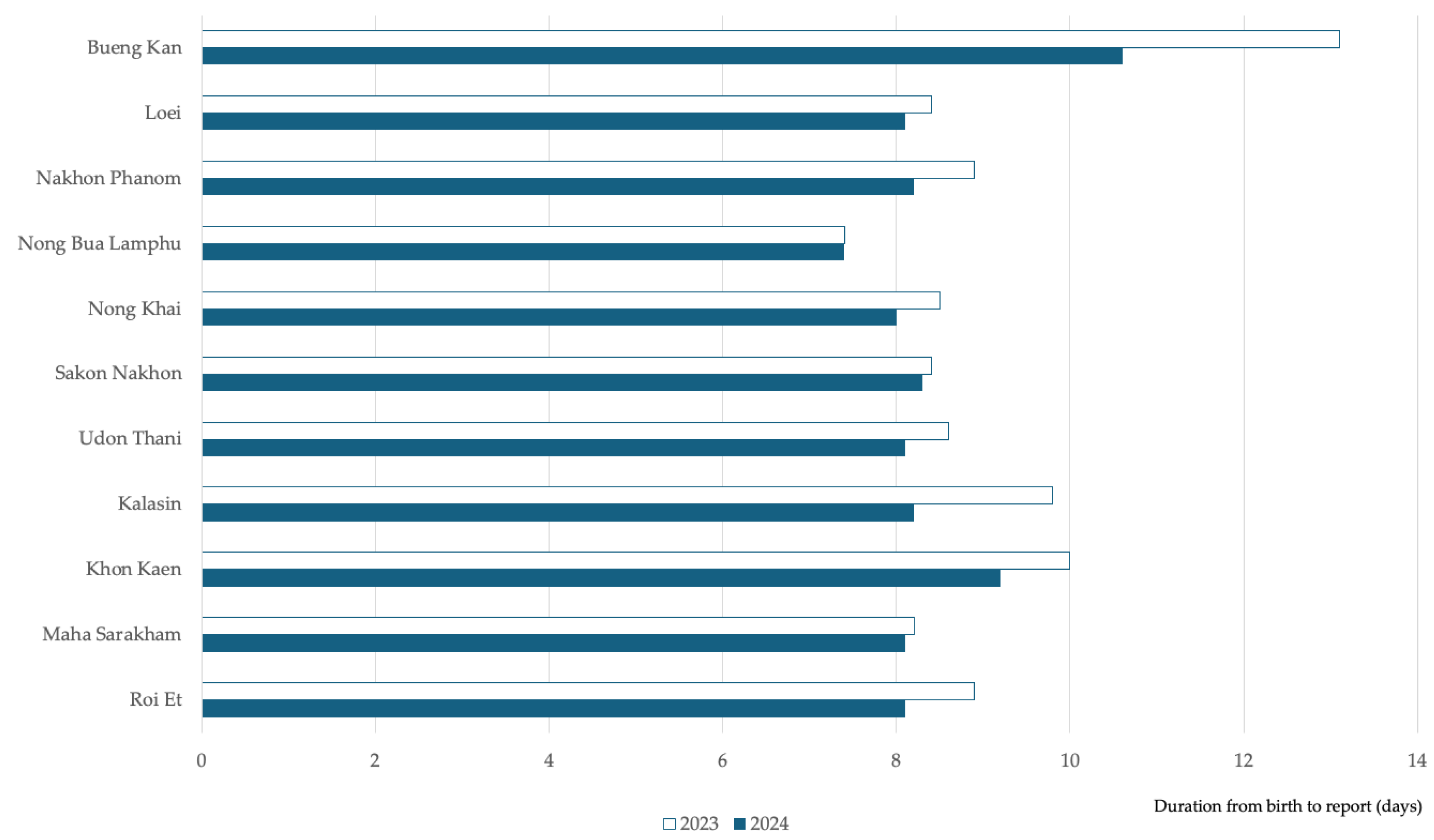

The Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) set by the Department of Medical Science, Ministry of Public Health, specify that laboratory processing should be completed within 3–5 days, and the duration from birth to report should not exceed 14 days. The NBS laboratory at Srinagarind Hospital exceeded these benchmarks, achieving an average laboratory processing time of 1.4 days. The process outcomes showed improvement, with the average duration from birth to reporting reduced from 9.13 days in 2023 to 8.4 days in 2024. The birth-to-report duration improved across all 11 provinces from 2023 to 2024, with Bueng Kan province achieving the highest reduction at 19.1%. (

Figure 4.) This improvement followed the presentation of performance reports at a conference and subsequent workflow adjustments in collaboration with network hospitals.

4. Discussion

NBS is an important tool in advancing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: Good Health and Well-Being. By enabling early detection of congenital and metabolic disorders, NBS significantly improves health outcomes through timely intervention and treatment. Many countries have developed tailored NBS programs, each designed to address their specific public health needs and target disorders. The expanded NBS program in Thailand has transitioned to a decentralized model, with Srinagarind Hospital uniquely positioned as one of 10 NBS centers. Before decentralization, the NBS program was primarily managed by the Department of Medical Science, Ministry of Public Health, located in Bangkok Metropolitan Region. Srinagarind Hospital is strategically located and optimally placed to serve HR 7 and 8 in northeastern Thailand. Furthermore, it is the only RD Center located outside the Bangkok metropolitan area, providing a distinct advantage in facilitating collaboration with network hospitals. Srinagarind Hospital functions as a one-stop service center for screening, confirmatory testing, and treatment, making it a reliable hub for network hospitals. Its integrated services ensure timely and expert support, including consultations for positive NBS results, initial management recommendations, and rapid patient transfers when necessary.

Its strategic location significantly reduces logistical challenges for the region. For instance, the farthest province in its catchment area, Bueng Kan in HR 8, is approximately 270 km (a little over a 4-hour drive) from Srinagarind Hospital in Khon Kaen. If a baby born in Bueng Kan receives a positive result, the referral to Srinagarind Hospital is far more feasible compared to a referral to Bangkok, which is over 720 km away a journey that would take more than 11 hours by car. This proximity ensures more timely access to confirmatory testing and specialized care, which is critical for conditions requiring immediate intervention.

This disparity highlights a strategic gap in the national NBS program. The Srinagarind model demonstrates the critical importance of aligning NBS and RD Centers within the same catchment area. Such integration shortens processes, ensures timely care, and could significantly improve outcomes for time-sensitive conditions such as IEMs, where delays in diagnosis and treatment can be life-threatening. This model serves as a model for optimizing NBS programs in other regions.

The expanded NBS program in HR 7 and 8 of Thailand has proven to be a valuable model for implementing such initiatives in rural areas of developing countries. This program achieved a screening coverage rate of 98.6%, which is comparable to or exceeds rates reported in many developing countries in Asia [

5].

The NBS coverage rate stands at 98%. However, several factors may contribute to the remaining gap to reach 100% coverage, even after implementing the service across both regions. One key factor is the flexibility of birth registration, which can be completed within 15 days after birth. This flexibility contrasts with NBS, which is conducted at 48 hours of age. Additionally, birth registration can be carried out at any civil registration office, regardless of the baby’s place of birth. Population movement also plays a role, as pregnant women may relocate due to work or be referred to tertiary care hospitals in different areas for delivery. After giving birth, these mothers may register their newborns at a registration office in a different location from the birth hospital. These factors can lead to slight discrepancies between the number of screenings conducted in each region and the number of births reported. To address this, compiling data from all NBS centers nationwide is essential for providing the most accurate representation of screening coverage of Thailand.

Globally, expanded NBS programs in developed countries often report confirmatory rates of over 95% for positive cases, similar to the results achieved for both TSH and IEMs in this study. However, the 96.0% follow-up rate for IEMs was lower than the TSH indicates room for improvement in rural Thailand. Factors such as healthcare access disparities and limited public awareness of metabolic disorders might contribute to this difference.

The recall rates observed in this study were 1 in 425.1 for TSH, with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.35, and 1 in 221.0 for IEMs, with a PPV of 0.05. While the recall rate and PPV for TSH fall within acceptable ranges, the recall rate for IEMs indicates a higher burden. This disparity may be attributed to the broader spectrum of disorders included in the screening panel, as well as several potential interferences such as extremely preterm infant, low birth weight, birth asphyxia, and the use of total parenteral nutrition. Additionally, the lower threshold for positive findings in our program may contribute to the higher recall rate for IEMs. These findings highlight the need for ongoing evaluation and refinement of screening protocols to balance sensitivity and specificity, particularly for IEMs, to minimize unnecessary recalls while maintaining effective detection of true positives. Enhanced data collection and analysis regarding the causes of false positives could further optimize the screening process and reduce the burden on families and healthcare systems.

The program identified 101 confirmed cases of CH and 20 confirmed cases of IEMs among the 122,004 newborns screened. The incidence rate of CH was 1 in 1,208 live births, slightly higher than the global average of 1 in 2,000–4,000 births [

6] and Thailand of 1 in 1,708 births [

7]. Further analysis found that Udon Thani province has highest incidence of 1 in 816 births. This finding suggests potential regional or ethnic predispositions. Another factor contributing to the higher CH incidence in this study compared to earlier reports in Thailand may be related to the NBS methodology. The current NBS program for TSH screening may include cases of transient CH, which accounts for approximately 29% of CH diagnoses [

8]. This is likely due to the limited availability of long-term systematic follow-up data for infants diagnosed with CH, which would be necessary to distinguish transient cases from permanent CH. These results emphasize the need for comprehensive follow-up systems to ensure accurate classification and better understanding of CH incidence trends.

The incidence of IEMs in this study was 1 in 6,100 live births, which is twice as high as the rate reported in previous pilot studies conducted in Bangkok, Thailand [

3]. Further investigations revealed regional genetic variations that contribute to this difference. For example, a founder mutation, c.1534C>T (p.Arg512Cys) in the

PCCB gene, associated with propionic aciduria, was identified in Nakhon Phanom province. Additionally, the c.51C>G (p.Phe17Leu) mutation in the

SLC22A5 gene, linked to carnitine uptake deficiency, was found to have a higher prevalence in the Thai population [

9], consistent with its increased allele frequency in East Asian populations, with the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) aggregated allele frequency of 0.001662 [

10]. These findings highlight the influence of genetic diversity on the incidence of IEMs and highlight the importance of region-specific genetic studies to tailor screening and second-tier diagnostic strategies.

Maternal conditions affecting NBS results, such as maternal carnitine deficiency, were identified in six cases. Although these conditions are often asymptomatic in mothers, their detection through NBS can provide significant benefits. Early identification allows for interventions that may prevent or mitigate potential health issues in both childhood and adulthood, such as muscle weakness, fatigue, or more severe metabolic complications. Moreover, detecting maternal conditions highlights an added value of NBS programs: the potential to uncover undiagnosed health issues in mothers. Addressing these conditions not only improves maternal health but also reduces the risk of adverse outcomes in future pregnancies. This highlight the importance of systematic follow-up and family health evaluations when abnormal results are detected, as well as the value of integrating maternal assessments into NBS protocols for comprehensive care.

Our study demonstrated the effectiveness of utilizing technology to streamline the entire NBS process, from sample collection to reporting. The use of electronic ordering by 100% of network hospitals significantly reduced human errors and labor hours in the laboratory process. The coordinators at network hospitals can monitor the real-time status of their samples through the KKU-IEM platform, ensuring transparency and efficiency. The program is continuously developed and updated based on user feedback, ensuring it remains user-friendly and responsive to the needs of the coordinators. This collaborative and iterative approach encourages widespread adoption and ease of use among stakeholders. The reduction in the average time from birth to reporting (from 9.13 days in 2023 to 8.4 days in 2024) highlights the program's commitment to continuous improvement. These enhancements were driven by performance feedback shared at conferences and subsequent workflow adjustments made in collaboration with network hospitals. Faster turnaround times are critical, particularly for conditions such as IEMs, where delays in diagnosis and treatment can result in irreversible developmental delays or even mortality.

Given the program's strong performance, it has been shared with other NBS centers across Thailand to help improve the overall NBS process nationwide. This initiative not only enhances service quality at a regional level but also contributes to a more efficient national NBS system, ensuring better outcomes for affected infants and their families.

The program's geographic analysis revealed variations in the duration from birth to report across provinces, with Bueng Kan demonstrating longer times compared to others. This variability could reflect differences in hospital infrastructure, sample transportation logistics, or personnel training levels. Following the implementation of a knowledge management process in 2024, significant improvements were observed in Bueng Kan province. Adjustments made to the processes in network hospitals resulted in a notable 19.1% reduction in reporting time. This improvement highlights the effectiveness of data-driven interventions and collaborative problem-solving in enhancing service delivery and ensuring more timely care for affected newborns.

The success of the expanded NBS program in rural Thailand emphasizes the feasibility of implementing such initiatives in resource-limited settings. The integration of digital tools, such as the KKU-IEM online platform, played a critical role in streamlining processes from registration to result reporting. Collaboration with TPD for sample logistics ensured timely and efficient transportation, even in remote areas. These innovations can serve as a model for other developing countries seeking to establish or scale up their own NBS programs.

Our NBS program also benefited from a robust quality control system, including participation in international proficiency testing and inter-laboratory comparisons. These measures not only ensured high standards but also aligned the program with global benchmarks, bolstering its credibility and sustainability.

Moving forward, the program should focus on further reducing reporting times, particularly for very urgent conditions, by utilizing real-time data analytics and automated result reporting systems. Expanding public education campaigns on the importance of NBS and involving community health workers in follow-up care could enhance parental compliance and reduce missed follow-ups.

Additionally, conducting long-term outcome studies on affected infants would provide critical insights into the efficacy of early interventions and help shape future policy decisions. Another important step would be to develop second-tier tests for positive results, enhancing diagnostic specificity. The program should also consider including additional diseases that pose significant regional challenges but are preventable or treatable, further broadening its impact.

5. Conclusions

The expanded NBS program in HR 7 and 8 of Thailand demonstrates a successful model for rural implementation, achieving 98.6% coverage and reducing reporting times to 8.4 days in 2024. The integration of the KKU-IEM platform and collaboration with network hospitals ensured operational efficiency and timely management. This model emphasizes the value of data-driven improvements, region-specific strategies, and comprehensive follow-up systems in enhancing NBS programs, serving as a model for similar initiatives in resource-limited settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W., N.S. and P.P.; methodology, K.W., N.S. and P.P.; investigation, K.W., N.S., A.P., K.S., N.C., S.Te., P.W., S.D., C.P., J.R., S.Th. and A.R.; validation, K.W. and N.S.; data curation, K.W. and N.S.; formal analysis, K.W. and N.S; writing—original draft preparation, K.W.; writing—review and editing, K.W., N.S. and A.R.; visualization, K.W.; project administration, K.W.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research, Khon Kaen University (HE661317, 1st July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Thailand NHSO for approving universal health coverage for expanded NBS for Thai citizens and 169 network hospitals in HR 7 and 8 for their collaboration in implementing the NBS program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CH |

Congenital hypothyroidism |

| HITAP |

Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program |

| HR |

Health Regions |

| IEMs |

Inborn errors of metabolism |

| MS/MS |

Tandem mass spectrometry |

| NBS |

Newborn screening |

| NHSO |

National Health Security Office |

| TPD |

Thailand Post Distribution |

| RD |

Rare Disease |

References

- Guthrie, R. Blood Screening for Phenylketonuria. JAMA 1961, 178, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensiriwatana, W.; Janejai, N.; Boonwanich, W.; Krasao, P.; Chaisomchit, S.; Waiyasilp, S. Neonatal Screening Program in Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2003, 34 Suppl 3, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liammongkolkul, S.; Sanomcham, K.; Vatanavicharn, N.; Sathienkijkanchai, A.; Ranieri, E.; Wasant, P. Expanded newborn screening program in Thailand. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5 Suppl 2, AB133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampang, R.; Angkab, P.; Leelahavarong, P.; Saengsri, W.; Vatanavicharn, N. Feasibility Study of Newborn Screening for Inborn Errors of Metabolism by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Health Syst. Res. 2024, 18, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Therrell, B.L.; Padilla, C.D.; Borrajo, G.J.C.; Khneisser, I.; Schielen, P.C.J.I.; Knight-Madden, J.; Malherbe, H.L.; Kase, M. Current Status of Newborn Bloodspot Screening Worldwide 2024: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Activities (2020–2023). Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; He, W.; Zhu, J.; Deng, K.; Tan, H.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, M.; Guo, Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Congenital Hypothyroidism among Neonates from 1969 to 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 2957–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaisri, H.; Puangtabtim, W.; Krasao, P.; Thongngao, P.; Auttarawanit, S.; Innark, P.; Pankanjanato, R.; Dhepakson, P.; Mahasirimongkol, S. The recall prevalence in congenital hypothyroidism screening due to thyroid stimulating hormone levels among newborns using dried blood spot samples in Thailand from 2015 to 2022. Dis. Control J. 2024, 50, 526–538. [Google Scholar]

- Jaruratanasirikul, S.; Piriyaphan, J.; Saengkaew, T.; Janjindamai, W.; Sriplung, H. The Etiologies and Incidences of Congenital Hypothyroidism before and after Neonatal TSH Screening Program Implementation: A Study in Southern Thailand. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. JPEM 2018, 31, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liammongkolkul, S.; Boonyawat, B.; Vijarnsorn, C.; Tim-Aroon, T.; Wasant, P.; Vatanavicharn, N. Phenotypic and Molecular Features of Thai Patients with Primary Carnitine Deficiency. Pediatr. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Pediatr. Soc. 2023, 65, e15404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, J.F.T.; Yu, M.H.C.; Chui, M.M.C.; Yeung, C.C.W.; Kwok, A.W.C.; Zhuang, X.; Lee, R.; Fung, J.L.F.; Lee, M.; Mak, C.C.Y.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Recessive Carrier Status Using Exome and Genome Sequencing Data in 1543 Southern Chinese. NPJ Genomic Med. 2022, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).