1. Introduction

Newborn screening (NBS) is a public health program aimed at preventing severe disabilities and reduced life expectancy caused by congenital diseases through early diagnosis; it has been implemented globally since the introduction of the Guthrie test in the 1960s. In Japan, after pilot studies, a publicly funded NBS was implemented in 1977 as a population-based screening initiative to improve national health, and all newborns were required to undergo the test. Currently, approximately 20 diseases are covered by NBS, including disorders of amino acids, organic acids, and fatty acid metabolism. In addition, an increasing number of municipalities offer optional screening (at the patient’s own expense) for conditions such as spinal muscular atrophy, severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome, and lysosomal diseases [

1]. With the widespread implementation of NBS, the diagnosis of rare diseases has become increasingly feasible. However, in recent years, the conditions included in NBS panels have expanded to encompass disorders that may not be fully amenable to effective treatment, along with cases involving false positives and variants of uncertain significance. These characteristics differ substantially from those of classical target conditions and have prompted ongoing debates regarding the appropriateness of screening for such disorders from medical, economic, and psychosocial perspectives [

2,

3].

Genetic counseling (GC) is the process of helping people understand and adapt to the medical, psychological and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease [

4]. In Japan, 1,964 clinical geneticists (approximately 15.8 per million population, as of 2025) and 428 certified genetic counselors (CGCs) (approximately 3.5 per million population, as of 2025) are recognized as genetic professionals who provide GC. Clinical geneticists are designated subspecialists in Japan’s medical specialist system. Certification requires the completion of a primary specialty, followed by three to five years of additional training and successful completion of a qualifying examination. Japanese certified genetic counselors (non-physicians) are certified by the Japanese Society of Human Genetics and the Japanese Society of Genetic Counseling after completing a designated graduate-level training program and passing a certification examination [

5,

6,

7]. One distinguishing feature of GC in Japan is that only physicians are legally permitted to provide it as a formal medical practice. As a result, CGCs cannot provide GC independently because their role is classified as medical assistance. Therefore, CGCs work in collaboration with clinical geneticists to supplement their workload and provide psychosocial support.

Many of the diseases identified through NBS are hereditary, and professional statements and guidelines recommend GC for individuals with positive results [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although the importance of GC in NBS is acknowledged in the Guidelines for Genetic Tests and Diagnosis in Medical Practice by the Japan Association of Medical Sciences [

5], no studies have examined the current status of GC in Japan. This study aimed to assess the current status of GC in the context of NBS in Japan and to explore recommendations for its future implementation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Methods

This survey was conducted using a web-based questionnaire to determine the status of GC implementation at Japanese referral center for NBS as of May 2024. In Japan, patients who screen positive through NBS are referred to the local referral center for NBS in each prefecture for diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, one person from each prefecture was selected for this survey based on a list of physicians designated as “pediatricians who play a central role in NBS programs in each municipality in Japan (metabolic specialist for diagnostic evaluation and treatment),” which is available upon approval from the Japanese Society of Neonatal Screening.

2.2. Data Collection Procedures

The survey used an internet response system, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDcap), to transmit and collect data. The content was developed based on input from several physicians and a CGC who are routinely involved in NBS and specialize in pediatrics, obstetrics, gynecology, and clinical genetics.

Attributes of respondents

Characteristics of their institutions (e.g., number of genetic professionals)

GC implementation status for patients who screen positive through NBS (*): conditions for implementation, people in charge, etc.

Necessity and issues of GC

* GC on the implementation of genetic testing (nucleic acid analysis) in infants.

2.3. Data Analysis

After calculating totals and proportions using descriptive statistics, we analyzed the collaboration between metabolic specialists and genetic professionals. Cases in which a clinical geneticist or CGC was involved in GC were categorized as “collaboration,” and those without collaboration were grouped as “no collaboration.” However, if the clinical geneticist involved in GC was also the metabolic specialist responsible for childcare, the case was classified as “no collaboration.” First, a chi-square test was conducted using EZR to assess the presence of collaboration with each genetic professionals, the number of genetic professionals employed, and the presence of a genetic department. The same test was then used to compare collaborations involving clinical geneticists and CGC. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Attribution

All participants responded to the survey. The respondents were affiliated with the following institutions: university hospitals (39/47, 83.0%); other general hospitals (4/47, 8.5%); perinatal medical centers other than university hospitals (3/47, 6.4%); and other institutions (1/47, 2.1%). All respondents were pediatricians, with 44 (94.0%) affiliated with pediatrics departments and 3 (6.0%) with the Division of Clinical Genetics primarily. Fifteen respondents (15/47, 32.0%) were clinical geneticists. All respondents were familiar with GC; over 90% reported routinely treating genetic disorders and having experience referring patients to GC, while 81% stated they had personal experience in GC (

Table 1). These findings indicate that metabolic specialists, who are also pediatricians, possess extensive experience in genetic medicine.

3.2. Genetic care system in Referral center for NBS.

Approximately 90% of the centers had a clinical genetics division (41/47, 87.2%). Although 31 centers (66.0%) had at least five clinical geneticists, the most common response indicated that no clinical geneticists where primarily assigned to the Division of Clinical Genetics (21/46, 45.7%). The number of genetic counselors varied across institutions (

Supplementary Table 1). Although most centers had a genetic department, both the number of personnel and the quality of services varied. In particular, a relatively high proportion of clinical geneticists were assigned not only to genetics departments but also to other clinical departments.

3.3. Response to Positive Newborn Screening Cases

3.3.1. Implementation of genetic counseling in child genetic testing

Forty-five centers performing genetic testing in children were asked about the implementation status of GC. GC was routinely performed in 21 centers (46.7%), conditionally performed in 22 (48.9%), and not performed in 2 (4.4%). GC was performed in 25 pediatric departments (58.1 %) and 18 Divisions of Clinical Genetics (41.9 %). The most frequently selected personnel for GC were 31 metabolic specialists (72.1 %), of whom 16 (51.6%) were clinical geneticists. Clinical geneticists, who were not metabolic specialists, were selected by the majority, while CGC were selected by less than half of the respondents (multiple responses allowed) (

Table 2). As shown above, most referral center for NBS in Japan provided GC for patients who screen positive through NBS, although it is not routinely implemented in approximately half of them. The results also showed that the majority of GC was provided by metabolic specialists (> 70%), regardless of whether they were clinical geneticists. Conversely, over 60% of the facilities had clinical geneticists, other than metabolic specialists, participating in GC.

Respondents were asked about the implementation of GC for individuals who screen positive through NBS. Forty-three of the 45 facilities provided GC. The most frequently selected GC providers were, in descending order, metabolic specialists and clinical geneticists other than metabolic specialists. Among the metabolic specialists selected as GC providers, 16 (51.6%) qualified as clinical geneticists.

3.3.2. Cooperation between metabolic specialists and genetic professionals

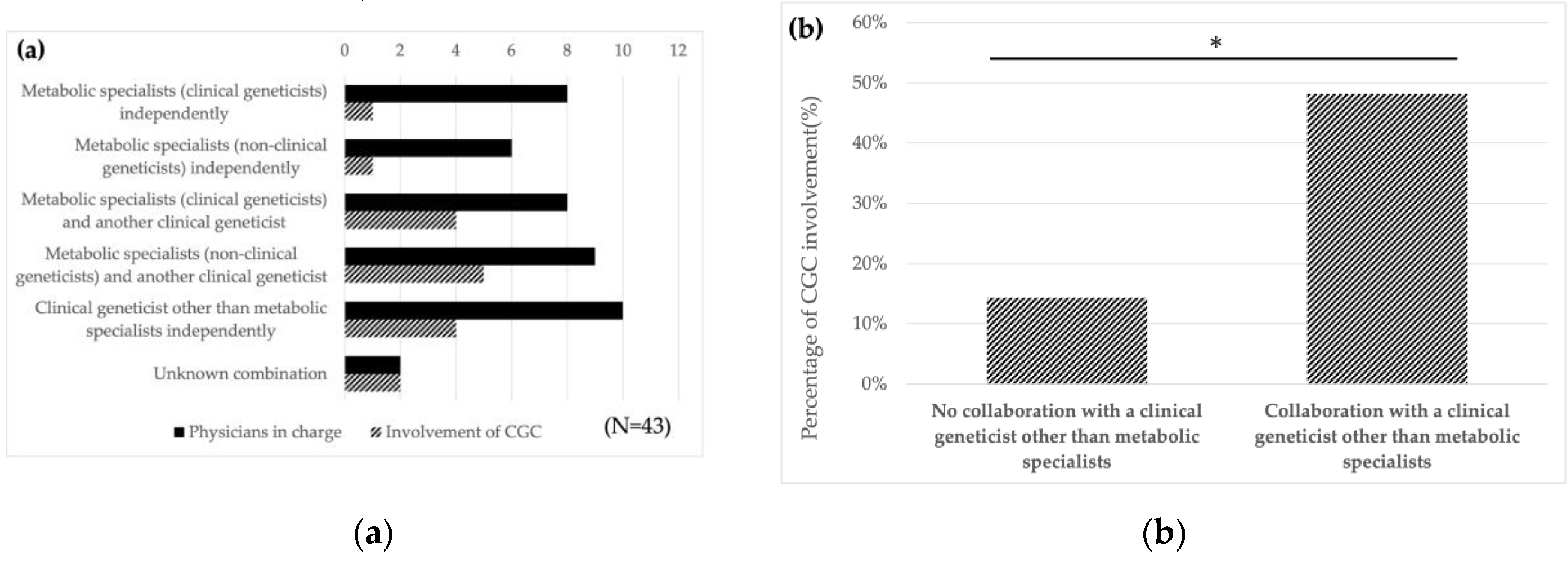

We examined the status of collaboration between metabolic specialists and genetic professionals in the provision of GC. First, using the data on GC personnel in

Table 2, we identified the combinations of physicians selected at each facility and the involvement of CGC (

Figure 1-a). These combinations were further classified into two groups based on whether clinical geneticists other than metabolic specialists were involved: 14 centers (34.1%) and 27 centers (65.9% ). In these two groups, CGC involvement was reported in 2 of 14 centers (14.3%) and 13 of 27 centers (48.1%), respectively.

Data analysis showed that the proportion of CGC involvement was significantly higher (p=0.044) in facilities where clinical geneticists other than metabolic specialists were involved (

Figure 1-b). The results indicate that both clinical geneticists and the CGC tend to be involved when metabolic specialists collaborate with other clinical geneticists. Collaboration between metabolic specialists and genetic professionals in NBS did not always occur, even when the number of genetic professionals at a facility increased.

3.4. Opinions of metabolic specialists regarding GC

Respondents were asked to provide their opinions regarding GC for individuals who tested positive through NBS. All 46 respondents except one reported that “GC is useful for follow-up of the child (initiation and continuation of treatment)” and “useful for follow-up of the parents (consideration of future pregnancies and health care)” while one respondent stated “I am not sure about the usefulness of GC. The most frequently cited expectations for GC for individuals who screen positive through NBS were “consultation regarding future pregnancies (89.4%),” “providing and organizing genetic information (85.1%),” and “listening to patient and family anxiety and conflicts (78.7%)” (

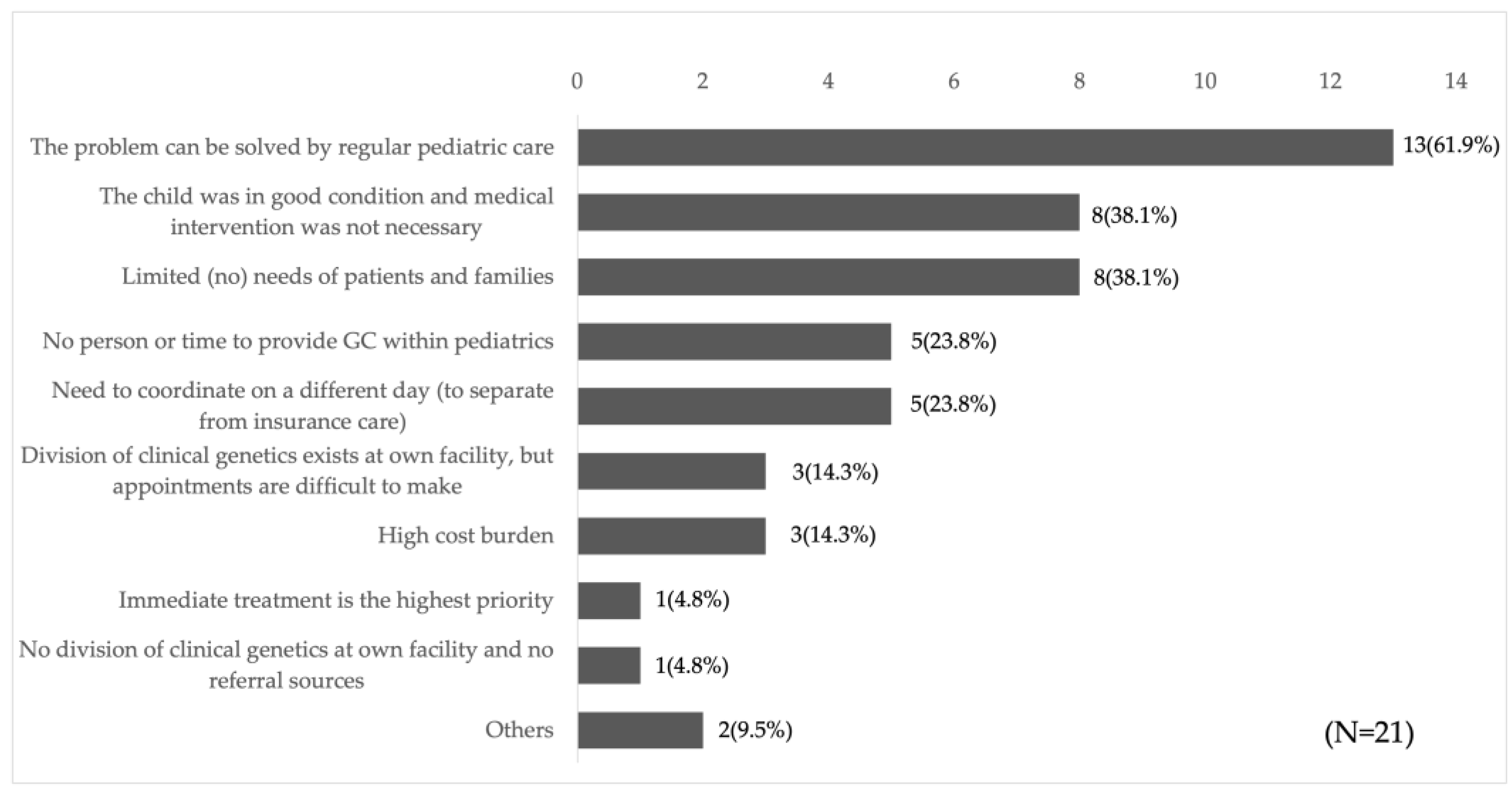

Supplementary Figure 1). Conversely, 21 respondents indicated that they “sometimes do not perform GC on individuals who screen positive through NBS”. The most common reasons cited were “the problem can be addressed through regular pediatric care” (13/21, 61.9%) and “the child was in good condition and did not require medical intervention” (8/21, 38.1%). Approximately 76.2% (16/21) of respondents cited one of these two reasons (

Figure 2). These findings suggest that some metabolic specialists perceived an overlap between the roles of GC and pediatric care, viewing GC as an extension of pediatric care in certain cases.

4. Discussion

This study clarified the current status of GC among NBS-positive cases across Japan and examined the perceptions of metabolic specialists. Based on these findings, the current challenges and the ideal future of GC are discussed.

4.1. Current status of GC in Japan - genetic consultation by metabolic specialists-

This survey revealed that, within the Japanese NBS system, metabolic specialists were relatively more likely to provide GC (

Table 2). This tendency may be attributed to the historical and cultural context in which the NBS developed in Japan. In the 1970s, when NBS was first launched, there were no specialists in Japan trained in GC, such as clinical geneticists or CGC, and GC— then referred to as “genetic consultation”— was provided by physicians as part of routine patient care. In the context of NBS, metabolic specialists had already established trusting relationships with patients and their families and possessed in-depth knowledge of the natural history and genetics of relevant disorders. Therefore, it was considered standard practice at that time for metabolic specialists to provide GC as part of pediatric care. In the 21st century, training programs for genetic professionals and the development of a genetic medicine system have progressed rapidly in Japan. However, the practice of metabolic specialists providing GC as an extension of general medical care remains deeply embedded in the NBS system.

4.2. Metabolic specialists tend to understand only the limited role of GC

While most respondents acknowledged the usefulness of GC for individuals who screen positive through NBS, some perceived its role as overlapping with that of standard medical care (

Figure 2). Individuals who screen positive through NBS may face a range of psychosocial challenges, including anxiety and confusion due to unexpected results, decisions about future reproduction, carrier status, and concerns regarding the genetics of blood relatives. These concerns are difficult to address within the constraints of time-limited pediatric care, and affected individuals and their families often experience ongoing conflict [

12]. Previous studies have demonstrated that GC benefits for individuals who tested positive through NBS include reduced parental anxiety, more efficient diagnosis of the child, improved parental understanding of results, provision of future reproductive options, enhanced patient-family communication, and diagnosis of relatives [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In other words, GC enables parents to “accept the results and adapt to the child’s diagnosis and treatment,” or to use the information provided to “prepare for future challenges,” even if the child is healthy, highlighting a quality of care that differs from conventional medical practice. Thus, these perceptions among metabolic specialists may be inappropriate, suggesting a limited understanding of the scope of GC. It is also important to note that the challenges faced by pediatric patients and their families—and their severity—are not always predictable based on disease severity [

18,

19,

20]. Therefore, metabolic specialists should recognize that all individuals who screen positive through NBS are eligible for GC.

4.3. Involvement of clinical geneticists in GC results in increased involvement of the CGC

The results of the data analysis showed that the proportion of CGCs involved in GC was significantly higher in facilities where metabolic specialists collaborated with other clinical geneticists (

Figure 1). As mentioned previously, in Japan, only physicians are legally permitted to provide GC as a medical practice; however, it is difficult for physicians alone to manage all tasks, and a cooperative system between clinical geneticists and CGCs is considered ideal. Given the current situation, the analysis suggests that the involvement of clinical geneticists may facilitate support from CGCs and promote multidisciplinary collaboration. A GC system with a multidisciplinary team is extremely important for NBS and requires flexible support for patients with positive results.

However, several factors hinder collaboration among genetics professionals. The first factor involves the perceptions of metabolic specialists. The previous results indicate a lack of understanding of the significance of GC. It is necessary to conduct educational campaigns targeting metabolic specialists and other pediatricians. Second, there is a shortage of genetics professionals. The number of clinical geneticists in Japan is not low compared to Western countries when adjusted for population size [

6,

21]. However, unlike the United States, where clinical genetics is recognized as a primary specialty (American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics), in Japan, it is a subspecialty pursued after obtaining certification in a primary field. Therefore, clinical geneticists are often required to practice concurrently in both the primary specialty and the clinical genetics division, which can easily limit their efforts. In addition, the shortage of CGC remains a challenge due to persistent understaffing [

22]. Finally, there is an institutional challenge. The placement of genetic professionals may be more likely to be prioritized in areas where GC is institutionally mandated (e.g., cancer genome medicine and prenatal testing). Therefore, it is necessary to improve the NBS implementation system to mandate the development of GC systems. Furthermore, the current GC fee structure in Japan adds charges only at the time of disclosing limited test results; however, the system should allow reimbursement at the time of GC implementation involving genetic professionals.

4.4. Other: issues related to GC of NBS

In addition, some issues remain concerning GC in NBS. First, obstetricians, gynecologists, and midwives need further education on GC. These health care providers should understand the prevalence of congenital diseases and the importance of NBS. In recent years, opportunities to provide parental testing information early in pregnancy have increased, making it feasible to raise public awareness of NBS during these encounters [

23,

24]. Second, information about GC and NBS must be disseminated to the public. A survey of parents of children who screen positive through NBS reported that many were unaware of the availability of GCs [

25]. Third, GC must be adapted over time [

26]. GC opportunities should align with parents’ life stages and the child’s developmental milestones. Finally, regional disparities in GC access persist. Clinical geneticists and CGC tend to be concentrated in urban centers, creating a lack of access for people in rural areas [

22]. There are validated cases and recommended guidelines for remote GC in NBS-positive patients overseas, which should be further discussed in Japan [

11,

27].

4.5. Limitations and Perspectives of the Study

The survey targeted Japanese metabolic specialist. A survey targeting professionals involved in NBS (pediatricians other than metabolic specialists, obstetricians/gynecologists, midwives, genetic counselors) is required to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the current situation. In addition, this survey does not consider differences in the number of births by prefecture and fails to reflect differences in the situation at each facility. The survey focused on the current status of population-based screening for all births; however, a separate survey is needed to assess the status of optional screening conducted by individual municipalities.

5. Conclusions

In Japan, GC for individuals who screen positive through NBS is currently provided by metabolic specialists and/or clinical geneticists, with CGC detected in fewer than half of the cases. Furthermore, it has been revealed that some metabolic specialists may be reluctant to provide GC due to an insufficient understanding. Improving the GC system requires enhanced collaboration between metabolic specialists and genetic professionals to provide comprehensive support for individuals who screen positive through NBS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions is required. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, E.S., T.Y., T.H., and T.S.; methodology, E.S., T.Y., T.H., and T.S.; validation, E.S., T.Y., T.H., and T.S; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, E.S. and T.H.; data curation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S., T.Y., T.H., and T.S.; visualization, E.S., T.Y., T.H., and T.S.; supervision, T.Y., T.H., G.T., and T.S..; funding acquisition, E.S., T.Y., T.H., G.T., and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by the Children and Families Agency Program, Government of Japan (Grant Number 23DA0801), and the Japanese Association of Certified Genetic Counselors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Medical Research and Other Research of Osaka Public University in April 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the pediatricians who took the time to respond to our survey.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NBS |

Newborn screening |

| GC |

Genetic counselor |

| CGC |

Certified genetic counselor |

References

- Japanese society for neonatal screening. Newborn screening and its target diseases. Available online: https://www.jsms.gr.jp/contents04-02.html (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Nicholls, S.G.; Wilson, B.J.; Etchegary, H.; Brehaut, J.C.; Potter, B.K.; Hayeems, R.; Chakraborty, P.; Milburn, J.; Pullman, D.; Turner, L.; et al. Benefits and burdens of newborn screening: public understanding and decision-making. Per Med 2014, 11, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andermann, A.; Blancquaert, I.; Beauchamp, S.; Déry, V. Revisiting Wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: a review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull World Health Organ 2008, 86, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Definition Task Force; Resta, R.; Biesecker, B.B.; Bennett, R.L.; Blum, S.; Hahn, S.E.; Strecker, M.N.; Williams, J.L. A new definition of Genetic Counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Task Force report [National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Task Force report]. J Genet Couns 2006, 15, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Japanese Association of Medical Sciences. Guidelines for genetic tests and diagnosis in medical practice. Available online: https://jams.med.or.jp/guideline/genetics-diagnosis_e_2022.pdf (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Japanese Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics, Clinical Genetics. List of clinical geneticists. Available online: https://www.jbmg.jp/senmon/ (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Japanese Board of Certified Genetic Counselors. List of certified genetic counselors. Available online: https://plaza.umin.ac.jp/~GC/About.html (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Ross, L.F.; Saal, H.M.; David, K.L.; Anderson, R.R.; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics [Technical report]. Technical report: Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Genet Med 2013, 15, 234–245. DOI:10.1038/gim.2012.176 [published correction appears in Ross, Laine Friedman [corrected to Ross, Lainie Friedman]. Genet Med 2013, 15, 321]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Bodamer, O.A.; Watson, M.S.; Wilcox, W.R.; ACMG Work Group on Diagnostic Confirmation of Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Lysosomal storage diseases: diagnostic confirmation and management of presymptomatic individuals. Genet Med 2011, 13, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borte, S.; von Döbeln, U.; Hammarström, L. Guidelines for newborn screening of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Curr Opin Hematol 2013, 20, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder-Schwind, E.; Raraigh, K.S.; CF Newborn Screening Genetic Counseling Workgroup; Parad, R.B. Genetic counseling access for parents of newborns who screen positive for cystic fibrosis: consensus guidelines. Pediatr Pulmonol 2022, 57, 894–902. [CrossRef]

- Hiromoto, K.; Nishigaki, M.; Kosugi, S.; Yamada, T. Reproductive decision-making following the diagnosis of an inherited metabolic disorder via newborn screening in Japan: a qualitative study. Front Reprod Health 2023, 5, 1098464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kladny, B.; Williams, A.; Gupta, A.; Gettig, E.A.; Krishnamurti, L. Genetic counseling following the detection of hemoglobinopathy trait on the newborn screen is well received, improves knowledge, and relieves anxiety. Genet Med 2011, 13, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder-Schwind, E.; Raraigh, K.S.; Parad, R.B. Practice variation of genetic counselor engagement in the cystic fibrosis newborn screen-positive diagnostic resolution process. J Genet Couns 2019, 28, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noke, M.; Wearden, A.; Peters, S.; Ulph, F. Disparities in current and future childhood and newborn carrier identification. J Genet Couns 2014, 23, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.L.; Flume, P.A. Pediatric and adult recommendations vary for sibling testing in cystic fibrosis. J Genet Couns 2018, 27, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foil, K.; Christon, L.; Kerrigan, C.; Flume, P.A.; Drinkwater, J.; Szentpetery, S. Experiences of cystic fibrosis newborn screening and genetic counseling. J Community Genet 2023, 14, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchbinder, M.; Timmermans, S. Newborn screening for metabolic disorders: parental perceptions of the initial communication of results. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012, 51, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loonen, H.J.; Derkx, B.H.; Griffiths, A.M. Pediatricians overestimate importance of physical symptoms upon children’s health concerns. Med Care 2002, 40, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesecker, B.B.; Erby, L. Adaptation to living with a genetic condition or risk: a mini-review. Clin Genet 2008, 74, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Government Accountability Office. Genetic services: information on genetic counselor and medical geneticist workforces. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-593?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Aizawa, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Kato, K. Institutional and social issues surrounding genetic counselors in Japan: current challenges and implications for the global community. Front Genet 2021, 12, 646177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report on the Establish-Ment of a System for Providing Information to Pregnant Women Including the Government; Scientific and Technical Committee of Health Science Council/Expert Committee on NIPT and OtherPrenatal Tests, 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000783387.pdf (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Japanese Association of Medical Sciences; Committee on the Certification System for Prenatal Testing. Guidelines on information provision for NIPT and certification of facilities (medical institutions and testing laboratories), 2022. Available online: https://jams-prenatal.jp/file/2_2.pdf (accessed on 6 Jul 2025).

- Hiromoto, K.; Yamada, T.; Kosugi, S. Parental emotions faced with the newborn screening diagnosis of inherited disorders in their baby: informing their chances of being carriers and the recurrence rate. Jpn J Genet Couns 2020.

- Schnabel-Besson, E.; Garbade, S.F.; Gleich, F.; Grünert, S.C.; Krämer, J.; Thimm, E.; Hennermann, J.B.; Freisinger, P.; Burgard, P.; Gramer, G.; et al. Parental and child’s psychosocial and financial burden living with an inherited metabolic disease identified by newborn screening. J Inherit Metab Dis 2025, 48, e12784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalker, H.J.; Jonasson, A.R.; Hopfer, S.M.; Collins, M.S. Improvement in cystic fibrosis newborn screening program outcomes with genetic counseling via telemedicine. Pediatr Pulmonol 2023, 58, 3478–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).