Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Samples

Design of Validation Plates

DNA Extraction

tNGS Panel Design and Sequencing

Bioinformatic Analysis

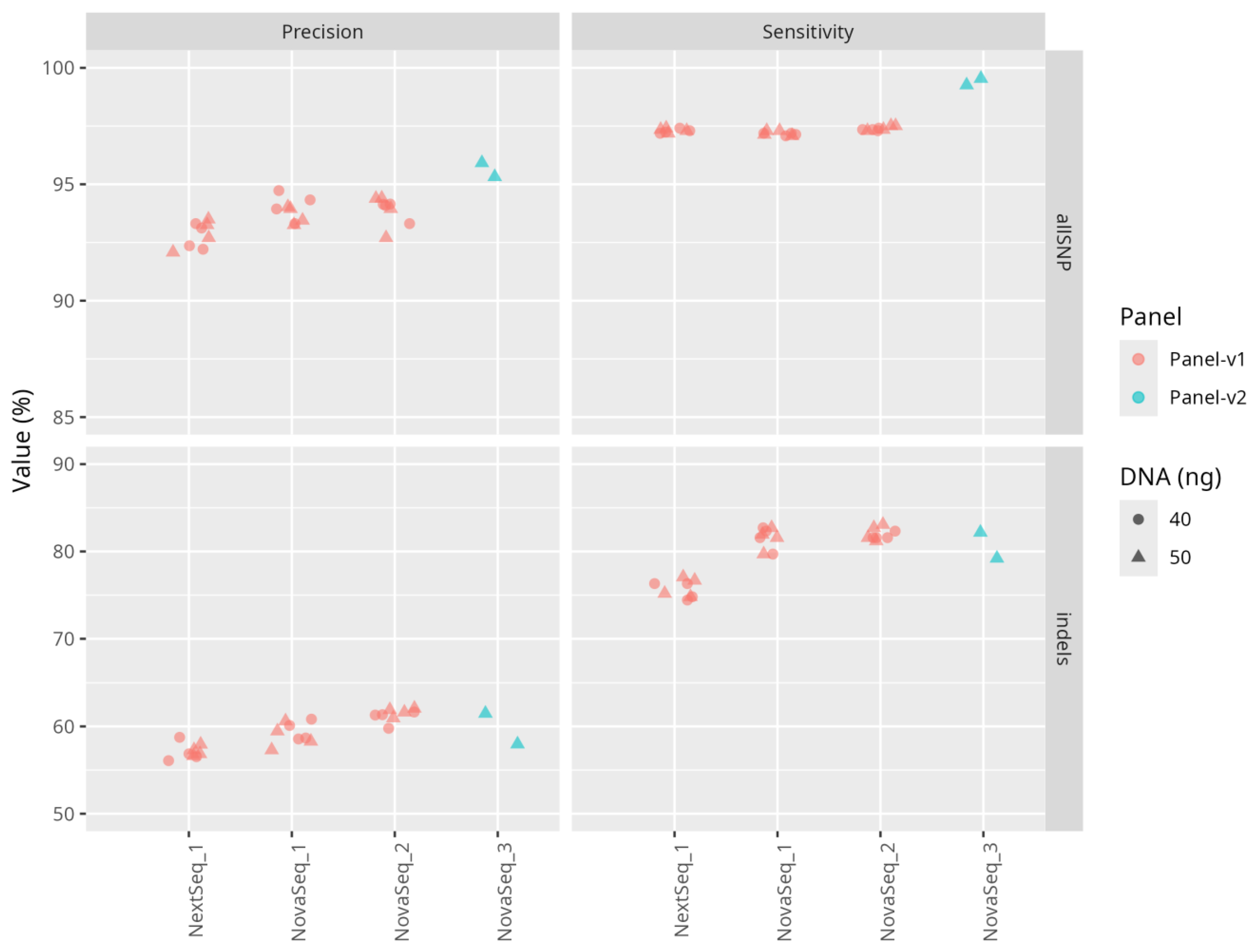

Sensitivity and Precision of Sequencing

Reproducibility of the Results

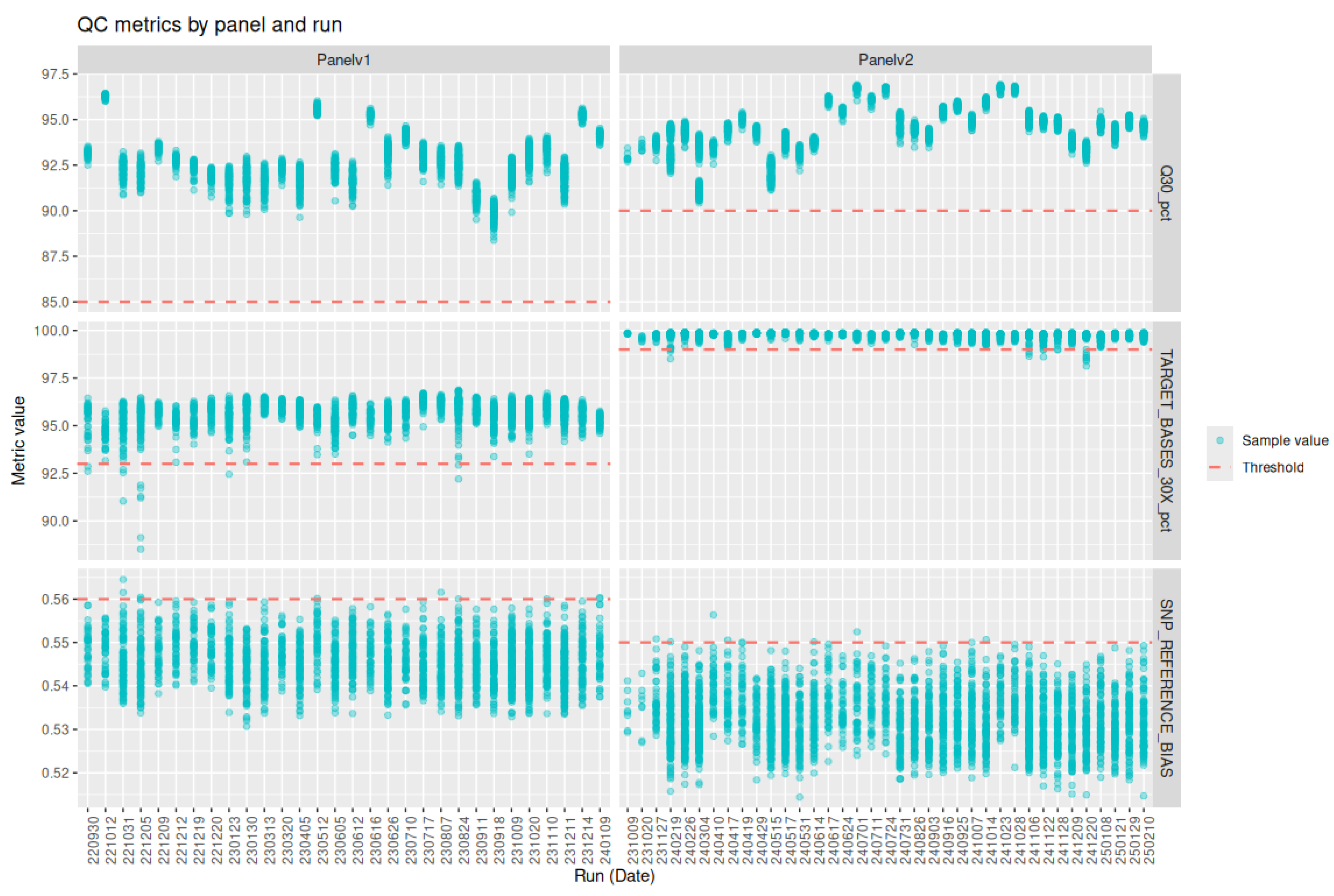

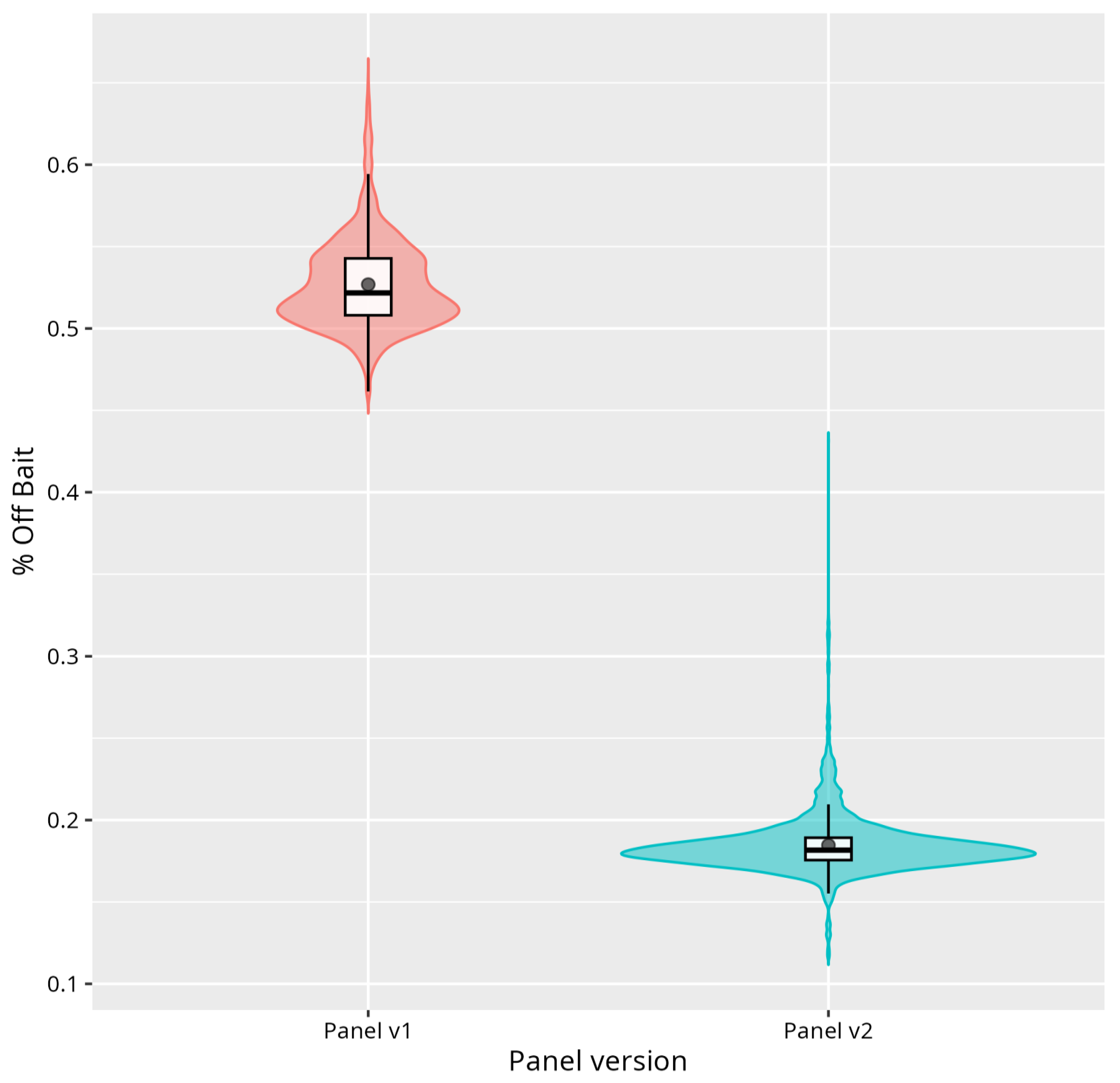

Definition and Selection of Quality Metrics

Sequencing

Threshold Setting

Variant Interpretation Pipeline

3. Results

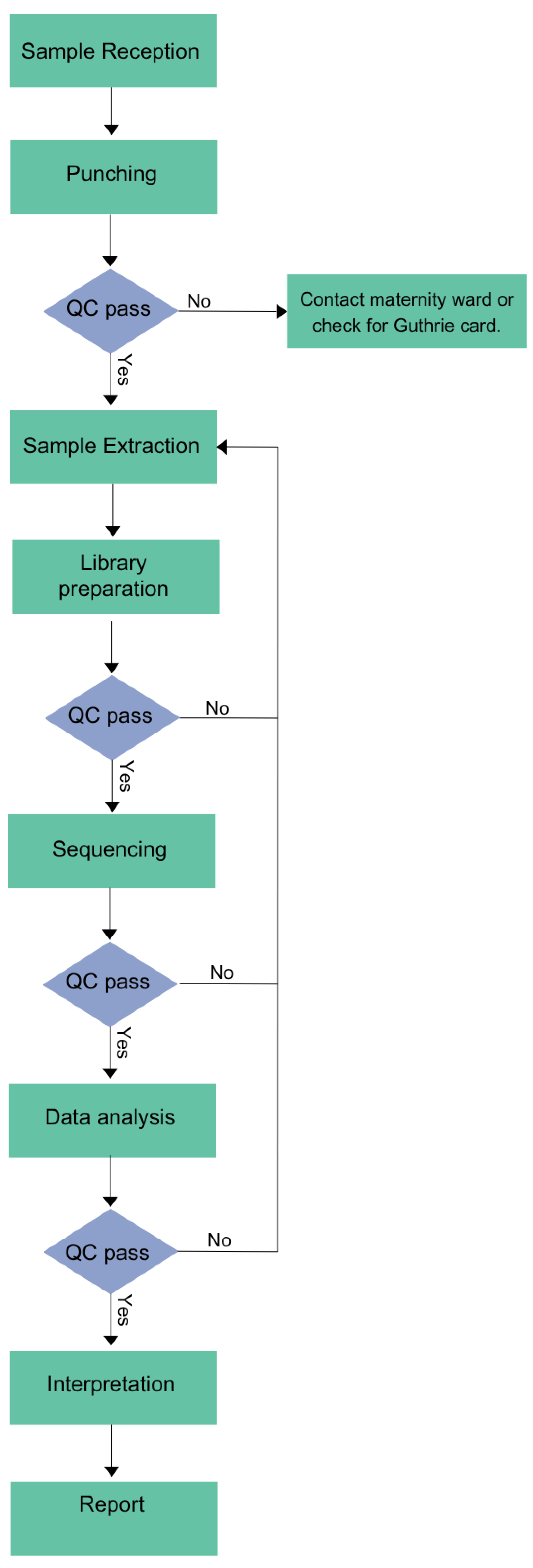

Workflow

Variant Interpretation Pipeline

Validation Samples

Performance of the Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability and Publication Ethics

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andermann, A. Revisting wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: a review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull. World Health Organ. 86, 317–319 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Fernhoff, P. M. Newborn Screening for Genetic Disorder. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. olume 56, Pages 505-513 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Engel, A. G. Congenital Myasthenic Syndromes. Rosenb. Mol. Genet. Basis Neurol. Psychiatr. Dis. Fifth Ed. Acad. Press, Pages 1191-1208 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Brennenstuhl, H. , Jung-Klawitter, S., Assmann, B. & Opladen, T. Inherited Disorders of Neurotransmitters: Classification and Practical Approaches for Diagnosis and Treatment. Neuropediatrics, 50, 002–014 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. & Prasad, A. Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Epilepsy: Current Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1384 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Amir, F.; et al. The Clinical Journey of Patients with Riboflavin Transporter Deficiency Type 2. J. Child Neurol. 35, 283–290 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E. A. & Schilsky, M. L. Current and Emerging Issues in Wilson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 922–938 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Van Der Burg, M. , Mahlaoui, N., Gaspar, H. B. & Pai, S.-Y. Universal Newborn Screening for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID). Front. Pediatr. 7, 373 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Boemer, F.; et al. Three years pilot of spinal muscular atrophy newborn screening turned into official program in Southern Belgium. Sci. Rep. 11, 19922 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Müller-Felber, W.; et al. Newbornscreening SMA – From Pilot Project to Nationwide Screening in Germany. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10, 55–65 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Servais, L. , Dangouloff, T., Muntoni, F., Scoto, M. & Baranello, G. Spinal muscular atrophy in the UK: the human toll of slow decisions. The Lancet, 405, 619–620. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; et al. Expanded Newborn Screening Using Genome Sequencing for Early Actionable Conditions. JAMA, 333, 232 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; et al. Genomic Sequencing as a First-Tier Screening Test and Outcomes of Newborn Screening. JAMA Netw. Open, 6, e2331162 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Boemer, F.; et al. Population-based, first-tier genomic newborn screening in the maternity ward. Nat. Med. ( 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The BabySeq Project, Team; et al. The BabySeq project: implementing genomic sequencing in newborns. BMC Pediatr. 18, 225 (2018).

- Kingsmore, S. F.; et al. Genome-based newborn screening for severe childhood genetic diseases has high positive predictive value and sensitivity in a NICU pilot trial. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 111, 2643–2667 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M. E. , Klein, A. W., Buitenhuis, E. C., Rodenburg, W. & Cornel, M. C. Expanded Neonatal Bloodspot Screening Programmes: An Evaluation Framework to Discuss New Conditions With Stakeholders. Front. Pediatr. 9, 635353 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Minten, T.; et al. Data-driven consideration of genetic disorders for global genomic newborn screening programs. Genet. Med. 27, 101443 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dangouloff, T.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Newborn Screening Program Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing in One Maternity Hospital in Southern Belgium. Children, 11, 926 (2024). [CrossRef]

- CHARLOTEAUX, B.; et al. Humanomics. GitLab. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; et al. Benchmarking challenging small variants with linked and long reads. Cell Genomics, 2, 100128 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Picard toolkit. Picard toolkit. Broad Inst. GitHub Repos, (2019) doi:https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/.

- Tawari, N. R.; et al. ChronQC: a quality control monitoring system for clinical next generation sequencing. Bioinformatics, 34, 1799–1800 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 17, 405–424 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Kopanos, C.; et al. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics, 35, 1978–1980 (2019).

- Ding, Y.; et al. Scalable, high quality, whole genome sequencing from archived, newborn, dried blood spots. Npj Genomic Med. 8, 5 (2023).

- Fang, H.; et al. Reducing INDEL calling errors in whole genome and exome sequencing data. Genome Med. 6, 89 (2014).

- Goldfeder, R. L.; et al. Medical implications of technical accuracy in genome sequencing. Genome Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR BioResource—Rare, Disease; et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals that genetic conditions are frequent in intensively ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. C.; et al. Factors influencing success of clinical genome sequencing across a broad spectrum of disorders. Nat. Genet. 47, 717–726 (2015).

- Royer-Bertrand, B.; et al. CNV Detection from Exome Sequencing Data in Routine Diagnostics of Rare Genetic Disorders: Opportunities and Limitations. Genes, 12, 1427 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jegathisawaran, J. , Tsiplova, K., Hayeems, R. & Ungar, W. J. Determining accurate costs for genomic sequencing technologies—a necessary prerequisite. J. Community Genet. 11, 235–238 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, K. , Buchanan, J., Taylor, J. C. & Wordsworth, S. Are whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing approaches cost-effective? A systematic review of the literature. Genet. Med. 1122–1130 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Nurchis, M. C.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Whole-Genome vs Whole-Exome Sequencing Among Children With Suspected Genetic Disorders. JAMA Netw. Open, 7, e2353514 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Green, R. C.; et al. Correction: Corrigendum: ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet. Med. 19, 606 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. R. , Ahmed, M. U., Barua, S. & Begum, S. A Systematic Review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Terms of Different Application Domains and Tasks. Appl. Sci. 12, 1353 (2022). [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, F.; et al. Digenic variant interpretation with hypothesis-driven explainable AI. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 7, lqaf029 (2025).

- Wratten, L. , Wilm, A. & Göke, J. Reproducible, scalable, and shareable analysis pipelines with bioinformatics workflow managers. Nat. Methods, 18, 1161–1168 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, P.; et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 316–319, (2017).

- Mölder, F.; et al. Sustainable data analysis with Snakemake. F1000Research, 10, 33 (2021).

- Kurtzer, G. M.; et al. hpcng/singularity: Singularity 3.7.3. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Kurtzer, G. M. , Sochat, V. & Bauer, M. W. Singularity: Scientific containers for mobility of compute. PLOS ONE, 12, e0177459 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Merkel, D. Docker: lightweight Linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux J. 2014, 2 (2014).

| sample ID | disease | Gene | variant 1 | variant 2 | method of confirmation | Validation panel-v1 |

| NBPOS-1 | Phenylketonuria (PKU) | PAH | c.1066-11G>A | c.1315+1G>A | Conventional NBS and panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-2 | Phenylketonuria (PKU) | PAH | c.1169A>G | c.898G>T | Conventional NBS and panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-3 | Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADCD) | DDC | c.823G>A | c.1037A>G | WGS and biochemical testing | |

| NBPOS-4 | Cystic fibrosis (CF) | CFTR | c.1521_1523delCTT | c.1521_1523delCTT | Conventional NBS and phenotyping CFTR | |

| NBPOS-5 | Medium-Chain-Acyl- CoA-Déshydrogénase (MCAD) | ACADM | c.948+2T>C | c.1045-2A>C | Sanger Sequencing | |

| NBPOS-6 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) | G6PD | c.466A>G | c.292G>A | Conventional NBS and panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-7 | Medium-Chain-Acyl- CoA-Déshydrogénase (MCAD) | ACADM | c.1084A>G | c.1084A>G | Conventional NBS and phenotyping ACADM | |

| NBPOS-8 | Cystic fibrosis (CF) | CFTR | c.3752G>A | c.3752G>A | Conventional NBS and phenotyping CFTR | |

| NBPOS-9 | Hemophilia B | F9 | c.1024A>G | panel-sequencing | Validation panel-v2 | |

| NBPOS-10 | Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) deficiency | ACADS | c.1147C>T | c.596C>T | panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-11 | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency | G6PD | c.466A>G | c.292G>A | panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-12 | Cystic fibrosis | CFTR | c.1865G>A | c.1865G>A | panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-13 | Cystic fibrosis | CFTR | c.1397C>G | c.3209G>A | panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-14 | Wilson disease | ATP7B | c.3207C>A | c.1877G>C | panel-sequencing | |

| NBPOS-15 | glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency | G6PD | c.1437G>C | panel-sequencing | ||

| NBPOS-16 | very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency | ACADVL | c.325G>A | c.601_603delGAG | panel-sequencing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).