1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of social media and e-commerce platforms has underscored the significance of influencers as strategic tools for attracting new customers and enhancing brand visibility. Influencers are defined as individuals who significantly shape the decision-making processes and opinions of large audiences through their social media presence [

1]. They exert considerable influence on consumer purchasing behavior and often demonstrate greater efficiency and immediacy in promoting products or services compared to traditional marketing methods [

2].

Given the pivotal role influencers play in both business and consumer contexts, diverse categories of influencers have emerged. Notably, non-human influencers, including pets, fictional characters, and virtual entities, actively engage followers through social media content, maintaining influence despite lacking human identity. In particular, rapid advancements in computer graphics technology have enabled the creation of virtual influencers with visually appealing appearances and compelling narratives, facilitating effective communication with audiences. Although followers recognize virtual influencers as meticulously designed digital entities rather than real individuals, they continue perceiving and interacting with them as authentic. This behavior, in which social norms are applied to virtual characters, aligns with the social actor paradigm in human-computer interaction research [

3].

With the expansion of the influencer market, the virtual influencer sector has experienced rapid growth simultaneously. According to Virtual Humans, an information repository for virtual humans, approximately 200 virtual humans were registered as of 2025, representing a 20-fold increase compared to 2015 [

4]. Virtual influencers actively engage on social media platforms as influencers, performers, entrepreneurs, and in various other capacities, thus extending their influence across diverse domains.

While virtual influencers evolve to address consumer demands in media, entertainment, education, advertising, and distribution, certain challenges remain. Notably, consumer discomfort with virtual entities and their limited effectiveness within specific demographic groups persist. This research aims to examine how the content characteristics of virtual influencers influence consumer purchase intentions and provides insights from a user-centered perspective.

Furthermore, by analyzing the mediating role of shopping value and the moderating effects of gender and generation, this study intends to assist developers, suppliers, and content providers in entertainment, education, and marketing to better understand factors driving consumer purchase decisions. Additionally, it seeks to provide practical implications for enhancing content quality and diversity in virtual influencer business strategies, contributing to the development and differentiation of related markets.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Virtual Influencers

Virtual influencers represent a synthesis of the concepts "virtual," denoting entities that do not possess physical existence, and "influencer," which describes individuals who exert influence over the public through a substantial social media following. These entities are also known as Computer Graphics Influencers or Artificial Intelligence Influencers [

5]. Although virtual influencers lack physical form, they maintain identity and selfhood within social media platforms, exerting considerable cultural influence over their audience [

6].

As the influencer market continues to grow, associated negative risks have emerged, leading to public disengagement. Followers frequently distance themselves from influencers due to inauthentic content or deceptive advertising practices [

7]. The Fair Trade Commission reported that between April and December 2022, 21,037 instances of disguised advertising, presented as review content, were identified during major social media inspections, with 8.3% involving professional influencers. Despite this figure representing a notable decline compared to 2019, the commission underscored the necessity for self-regulation within the industry, given its significant impact on consumer purchasing behavior [

8].

Virtual influencers mitigate the risks of moral scandals or reputational damage that real-life celebrities may encounter. They are crafted with carefully constructed narratives and visually appealing appearances. Unlike human influencers, they are not bound by temporal or spatial constraints, enabling businesses to fully realize their desired image. From this perspective, the likelihood of virtual influencers making undesirable statements or actions is minimal. Furthermore, there is no substantial difference in the perception of values and beliefs between human and virtual influencers among followers [

9].

Virtual influencers are digital characters that inhabit social media, bridging the divide between the real world and virtual space. They surpass the physical limitations of human influencers, offering extensive content without temporal or spatial restrictions, and present innovative narratives that engage followers. Their influence is expanding, particularly among younger generations who are accustomed to digital communication. The MZ generation (Millennials and Generation Z) and the Alpha generation, who predominantly use social media for communication, are anticipated to further amplify this influence.

2.2. Virtual Influencer Content

Social media content is autonomously accessed via mobile devices, allowing users to engage with it effortlessly and frequently, irrespective of time and location. Users swiftly consume and disseminate substantial volumes of content that align with their preferences [

10]. As social media platforms increasingly transform into shopping environments, content generated by influencers with significant followings functions similarly to brand-produced media advertisements [

11]. Virtual influencers possess the capability to freely alter their appearance, background, and other attributes to suit diverse environments and contexts [

12]. Organizations have acknowledged the commercial effectiveness of virtual influencers and are expanding their use in the entertainment, fashion, beauty, and other promotional industries [

13].

In this study, virtual influencer content is defined as a medium through which virtual influencers articulate themselves by creating limitless narratives that transcend the boundaries between reality and virtual space. It also serves as a platform through which virtual influencers exert influence over their followers.

2.3. Content Characteristics of Virtual Influencers

Given the limited scope of existing research on virtual influencers, the specific attributes of their content remain insufficiently defined. Nevertheless, drawing from related studies, this research identifies six principal characteristics:

Attractiveness: While criteria for attractiveness differ across cultures and historical periods, it remains a fundamental component in various domains. It significantly contributes to value creation in relationships, whether through everyday interactions or media exposure to celebrities [

14]. Influencers share aspects of their daily lives via social media content, inherently promoting products and exerting influence through perceived intimacy, thereby making attractiveness a crucial characteristic in related studies.

Authenticity: Authenticity pertains to the sincere expression of one's beliefs. Virtual influencers, characterized by their anthropomorphic appearance, expressions, personality, and social traits [

15], produce vivid content that enhances followers’ perceptions of authenticity [

16]. Consistently sharing and maintaining these traits through storytelling positively influences evaluations of influencers' authenticity, a vital factor in marketing effectiveness [

17].

Expertise: Expertise denotes the ability of an information source to persuade consumers or provide accurate judgments [

18]. The greater the perception of an influencer's experience or professional knowledge regarding a product, the more likely they are to elicit favorable responses from consumers [

19].

Playfulness: Playfulness involves elements that attract users through enjoyable content, distinguishing sites and enhancing user satisfaction [

20]. Individuals seeking playfulness value immersive experiences and exhibit positive attitudes toward digital environments. They derive enjoyment from e-commerce, rendering playfulness a significant characteristic [

21].

Informativeness: Informativeness involves effectively conveying product information to consumers. Online consumers value information similarly to offline advertising [

22]. Influencers, as public figures, disseminate information and foster relationships through online communities, thereby enhancing the credibility of their information compared to anonymous sources [

23].

Interactivity: Interactivity refers to users' direct engagement and communication with content provided in online environments [

24]. Virtual influencers employ social media content, comments, and messages to share their daily lives, introduce products, and engage in various interactions with followers. In online environments, interactivity significantly influences user behavioral intentions [

25].

2.4. Shopping Value

Research on consumer shopping has progressed from an exclusive focus on the cognitive dimensions of decision-making to an acknowledgment of the intrinsic value inherent in objects or experiences. Traditional information-processing perspectives assess products or services based on their effectiveness in fulfilling intended purposes or functions. In contrast, experiential perspectives emphasize satisfaction with the product or service itself, considering both utilitarian and hedonic criteria [

26].

Consumers recognize utilitarian shopping value when their shopping objectives are successfully achieved. Those with high utilitarian shopping value perceive shopping as a task and engage in rational, purposeful shopping behaviors [

27]. Consequently, utilitarian value conceptualizes shopping as a task or errand to be completed once specific objectives are met, resulting in deliberate and efficient product purchases [

28].

Conversely, as consumers seek to enhance their quality of life, material abundance, and diverse desires, they have become increasingly interested in the hedonic aspects of products that contribute to more enjoyable and pleasurable experiences [

29]. Particularly in e-commerce, where consumers cannot physically interact with or evaluate products, it is essential to provide shopping experiences that offer both utilitarian and hedonic values, such as enjoyment, usefulness, pleasure, and convenience [

30]. This indicates that both cognitive (utilitarian) and emotional (hedonic) elements play significant roles in elucidating purchasing and consumption behaviors [

31].

2.5. Purchase Intention

Intention is defined as the cognitive process involved in planning or attempting to execute an action, while purchase intention specifically refers to the likelihood that a consumer's planned or intended future action to acquire a product will translate into actual behavior, influenced by beliefs and attitudes [

32]. Consumer intention serves as an indicator of the probability that a particular behavior will be enacted. Online purchase intention pertains to the degree to which consumers plan to purchase products via online platforms [

33]. Purchase intention is a crucial metric for forecasting consumer purchasing behavior. Therefore, this study examines the impact of virtual influencers' content characteristics on purchase intention, considering the mediating role of shopping value, which includes both utilitarian and hedonic value.

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Research Model

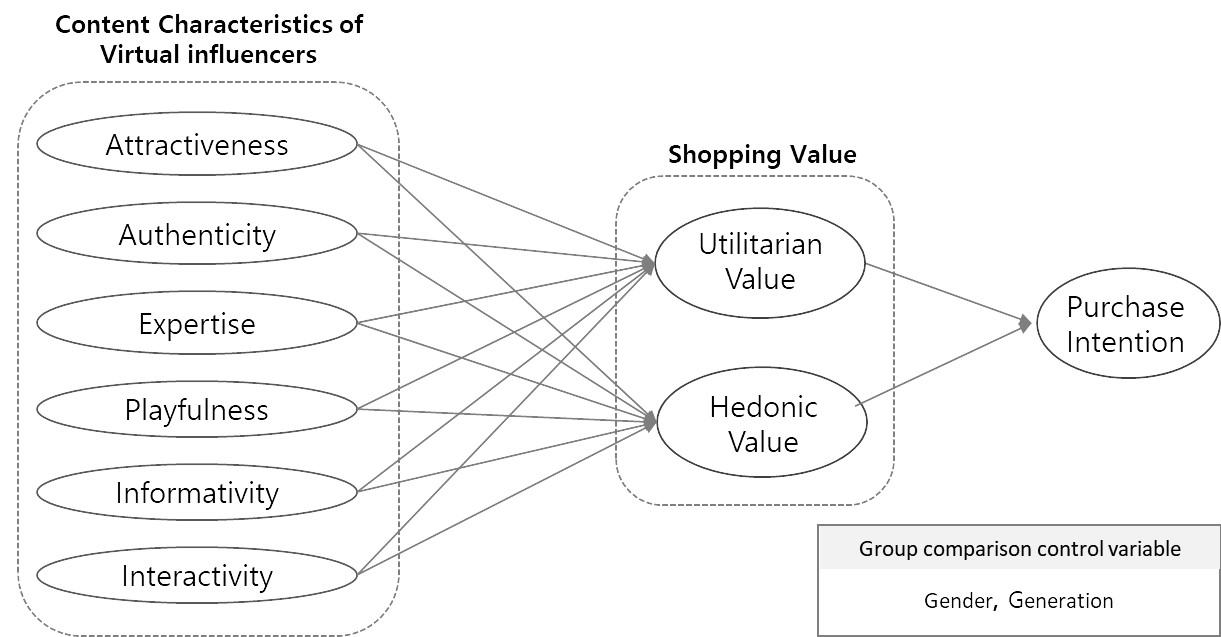

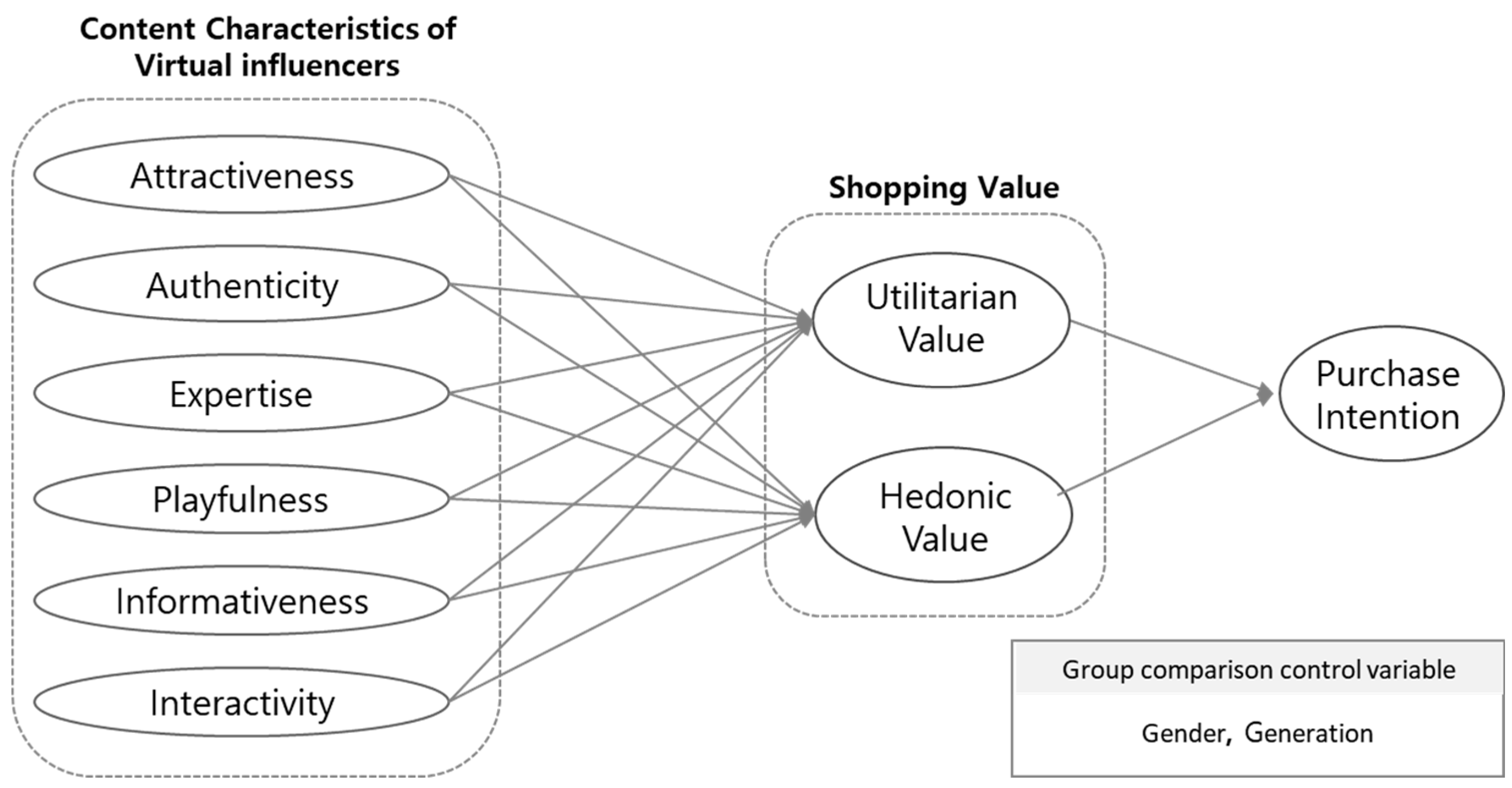

This study explored the determinants of consumer purchase intentions with respect to the content characteristics of virtual influencers, as depicted in

Figure 1. The research model evaluates empirical relationships among these variables. While prior research has predominantly concentrated on the personal attributes of both human and virtual influencers, this study highlights the content characteristics of virtual influencers, who disseminate information and exert influence via social media platforms. Furthermore, shopping value is categorized into utilitarian and hedonic dimensions to evaluate their respective effects on consumer purchase intentions.

3.2. Hypothesis Development

3.2.1. Relationship Between Virtual Influencer Content Characteristics and Utilitarian Value

Understanding the roles of quality and value within shopping contexts allows organizations to enhance brand positioning through precise market analysis, strategic planning, promotion, and pricing. These insights offer significant competitive advantages, although consumers may find them challenging to discern clearly [

34]. Utilitarian value can be defined as the satisfaction derived from successfully achieving intended outcomes through a purchase. It reflects previous successes in acquiring products or information and can influence subsequent consumer shopping behaviors [

35]. Consequently, based on previous research regarding attractiveness, authenticity, expertise, playfulness, informativeness, and interactivity, this study posits that these content characteristics positively influence utilitarian shopping value.

H1. The content characteristics of virtual influencers have a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-1. Attractiveness has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-2. Authenticity has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-3. Expertise has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-4. Playfulness has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-5. Informativeness has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value.

H1-6. Interactivity has a positive (+) effect on utilitarian value

3.2.2. Relationship Between Virtual Influencer Content Characteristics and Hedonic Value

Shopping experiences can evoke significant emotional responses that transcend the mere acquisition of products, with satisfaction closely linked to these emotions. Consequently, hedonic value exhibits a stronger correlation with emotional responses than utilitarian value [

35]. Evaluating consumer behavior solely from a rational perspective presents notable limitations. While cognitive factors such as quality and price are fundamental, experiential assessments are critical determinants of post-purchase satisfaction and loyalty. Emotional factors, in particular, significantly influence purchasing and consumption experiences, as well as consumers' social interactions and environment [

31]. Based on prior research, hedonic value can be conceptualized as the value derived from pleasurable emotions experienced during and after the shopping process. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that the content characteristics of virtual influencers positively influence hedonic shopping value.

H2. The content characteristics of virtual influencers have a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-1. Attractiveness has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-2. Authenticity has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-3. Expertise has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-4. Playfulness has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-5. Informativeness has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

H2-6. Interactivity has a positive (+) effect on hedonic value.

3.2.3. Relationship Between Shopping Value and Purchase Intention

This study examined the impact of utilitarian and hedonic shopping values on consumer purchase intentions, with a particular emphasis on the content characteristics of virtual influencers. Jones et al. (2006) demonstrated that both hedonic and utilitarian shopping values influence purchase outcomes and moderate the relationships among shopping satisfaction, word-of-mouth, purchase intention, and repurchase expectations [

35]. Sweeney & Soutar (2001) proposed that retail strategies incorporating both utilitarian and hedonic values acknowledge the multidimensional nature of product value as perceived by consumers, thereby playing critical roles in purchasing decisions [

26]. Building on these previous findings, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

3.2.4. Relationship with Gender and Generation as Moderating Variables

Moderating variables exert an influence on the strength or direction of the relationships between independent and dependent variables [

36]. Various methodologies have been developed to investigate these effects. In this study, demographic variables, specifically gender and generation, are considered as potential moderators to evaluate their impact on the relationships among research variables [

37].

Gender differences have frequently been examined as fundamental moderators in consumer behavior research [

38]. Son et al. (2021) reported that the MZ generation demonstrates greater proficiency in new digital technologies and exhibits preferences for novel and innovative content compared to older generations [

39]. Consequently, this study examines the moderating effects of gender and generation on the relationships between virtual influencer content characteristics and shopping value, as well as between shopping value and purchase intention.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Data Collection and Analysis Method

Data for this study was obtained via an online survey conducted among social media users from May 17 to May 20, 2024. Out of 1,541 total responses, 400 valid responses were selected for analysis after excluding entries that were incomplete, unsuitable, or insincere. To ensure an accurate understanding of virtual influencer content and to mitigate potential bias, the final sample comprised only adults with experience in consuming virtual influencer content, with equal representation in terms of gender and age.

The sample characteristics were as follows: 200 males (50.0%) and 200 females (50.0%). The age distribution was as follows: 30-39 years (32.0%), 40-49 years (28.5%), 20-29 years (18.0%), 50-59 years (15.0%), and 60 years and older (6.5%). Regarding generational cohorts, Millennials (born 1980–1994) constituted the largest group (43.2%), followed by Generation X (1965–1979, 32.2%), Generation Z (born after 1995, 18.0%), and Baby Boomers (1950–1964, 6.5%). The combined proportion of Millennials and Generation Z (collectively, the MZ generation) accounted for 61.2% of the sample, while older generations comprised 38.7%.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Respondents.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Respondents.

| Category |

Frequency |

% |

Group |

| Gender |

Male |

200 |

50.0 |

Male |

| Female |

200 |

50.0 |

Female |

| Total |

400 |

100.0 |

|

| Age |

20∼29 |

72 |

18.0% |

|

| 30∼39 |

128 |

32.0% |

|

| 40∼49 |

114 |

28.5% |

|

| 50∼59 |

60 |

15.0% |

|

| Over 60 |

26 |

6.5% |

|

| Total |

400 |

100.0% |

|

| Generation |

Generation Z |

72 |

18.0% |

MZ

generation |

| Millennials |

173 |

43.2% |

| Generation X |

129 |

32.2% |

Older generation |

| baby Boomer |

26 |

6.5% |

| Total |

400 |

100.0 |

|

4.2. Reliability and Validity Assessment

4.2.1. Reliability Assessment

Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach's α, with values exceeding 0.7 indicating satisfactory reliability [

40]. In the analysis of the partial least squares (PLS) model, composite reliability (DG.rho) values greater than 0.7 were also deemed reliable [

41]. Furthermore, eigenvalues above 1 were considered acceptable. In this study, Cronbach's α values for all latent variables surpassed the threshold of 0.7, and DG.rho values similarly exceeded 0.7, thereby confirming reliable measurement across all constructs.

Table 2.

Reliability Assessment Results.

Table 2.

Reliability Assessment Results.

| |

MVs |

C.alpha |

DG.rho |

eig.value |

| Attractiveness |

5 |

0.899 |

0.925 |

3.565 |

| Authenticity |

5 |

0.904 |

0.929 |

3.621 |

| Expertise |

5 |

0.916 |

0.937 |

3.739 |

| Playfulness |

5 |

0.919 |

0.939 |

3.778 |

| Informativeness |

5 |

0.895 |

0.923 |

3.524 |

| Interactivity |

5 |

0.886 |

0.916 |

3.434 |

| Utilitarian Value |

5 |

0.910 |

0.933 |

3.686 |

| Hedonic Value |

5 |

0.916 |

0.937 |

3.747 |

| Purchase Intention |

5 |

0.923 |

0.942 |

3.832 |

4.2.2. Validity Assessment

Convergent validity was evaluated through the average variance extracted (AVE), with values surpassing 0.5, signifying acceptable validity [

42]. All latent variables in this study demonstrated AVE values exceeding 0.5, thus confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity was established by ensuring that the square root of the AVE for each latent variable exceeded its correlation with other latent variables.

Table 3.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity Assessment Results.

Table 3.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity Assessment Results.

| |

AT |

AU |

EX |

PL |

IN |

IT |

UV |

HV |

PI |

AVE |

| AT |

0.844 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.713 |

| AU |

0.718 |

0.851 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.724 |

| EX |

0.696 |

0.752 |

0.865 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.748 |

| PL |

0.835 |

0.686 |

0.657 |

0.869 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.755 |

| IN |

0.742 |

0.707 |

0.801 |

0.747 |

0.839 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.705 |

| IT |

0.706 |

0.754 |

0.741 |

0.726 |

0.762 |

0.829 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.687 |

| UV |

0.774 |

0.749 |

0.773 |

0.768 |

0.818 |

0.816 |

0.859 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.737 |

| HV |

0.755 |

0.722 |

0.636 |

0.763 |

0.694 |

0.730 |

0.777 |

0.865 |

0.000 |

0.749 |

| PI |

0.756 |

0.773 |

0.685 |

0.745 |

0.724 |

0.755 |

0.828 |

0.844 |

0.875 |

0.766 |

4.2.3. Path Analysis Results

Structural equation modeling was performed utilizing the PLSPM Package in R, employing 2,000 bootstrapping resamples to ascertain the significance of the path coefficients. The hypotheses were assessed at a 5% significance level (t-value = 1.96).

Path analysis examining the relationship between virtual influencer content characteristics and utilitarian value indicated that attractiveness (t=3.250, p=0.001), expertise (t=2.856, p=0.005), playfulness (t=2.504, p=0.013), informativeness (t=5.455, p=0.000), and interactivity (t=6.901, p=0.000) exerted positive effects on utilitarian value, whereas authenticity was not supported.

The path analysis concerning virtual influencer content characteristics and hedonic value revealed that attractiveness (t=3.897, p=0.000), authenticity (t=4.666, p=0.000), playfulness (t=4.770, p=0.000), and interactivity (t=4.115, p=0.000) positively influenced hedonic value, while expertise and informativeness were not supported.

Path analysis between utilitarian value, hedonic value, and purchase intention demonstrated that both utilitarian value (t=11.800, p=0.000) and hedonic value (t=13.767, p=0.000) exhibited strong positive effects on purchase intention, with hedonic value showing a slightly stronger impact.

In summary, interactivity had the most substantial influence on utilitarian value, followed by informativeness, attractiveness, expertise, and playfulness. Playfulness exerted the strongest influence on hedonic value, followed by authenticity, interactivity, and attractiveness.

Table 4.

Path Analysis Results.

Table 4.

Path Analysis Results.

| |

Hypothesis path |

Estimate |

Std.Error |

t-value |

p-value |

Result |

| H1-1 |

Attractiveness |

|

Utilitarian

Value |

0.149 |

0.046 |

3.250 |

0.001 |

** |

Accept |

| H1-2 |

Authenticity |

0.078 |

0.040 |

1.938 |

0.053 |

|

Reject |

| H1-3 |

Expertise |

0.124 |

0.043 |

2.856 |

0.005 |

** |

Accept |

| H1-4 |

Playfulness |

→ |

0.114 |

0.046 |

2.504 |

0.013 |

* |

Accept |

| H1-5 |

Informativeness |

0.248 |

0.045 |

5.455 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H1-6 |

Interactivity |

0.289 |

0.042 |

6.901 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H2-1 |

Attractiveness |

→ |

Hedonic

Value |

0.220 |

0.056 |

3.897 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H2-2 |

Authenticity |

0.232 |

0.050 |

4.666 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H2-3 |

Expertise |

-0.080 |

0.053 |

-1.501 |

0.134 |

|

Reject |

| H2-4 |

Playfulness |

|

0.267 |

0.056 |

4.770 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H2-5 |

Informativeness |

0.069 |

0.056 |

1.240 |

0.216 |

|

Reject |

| H2-6 |

Interactivity |

0.212 |

0.051 |

4.115 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H3-1 |

Utilitarian

Value |

→ |

Purchase

Intention |

0.434 |

0.037 |

11.800 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

| H3-2 |

Hedonic

Value |

0.507 |

0.037 |

13.767 |

0.000 |

*** |

Accept |

4.2.4. Group Comparison Analysis.

This study conducted a comparative group analysis to investigate whether variations in path analysis outcomes were influenced by demographic factors, such as gender and generation. The analysis utilized a parametric approach, specifically employing a modified t-test method [

43].

Gender-Based Group Comparison

The study conducted a comparative analysis of male (n=200) and female (n=200) groups. Statistically significant differences were identified in two pathways: interactivity → utilitarian value (t=2.034, p=0.021), and authenticity → hedonic value (t=1.911, p=0.028). Male participants exhibited a heightened perception of utilitarian value in response to increased interactivity, whereas female participants demonstrated an enhanced perception of hedonic value in response to elevated authenticity.

Table 5.

Gender-Based Group Comparison Results.

Table 5.

Gender-Based Group Comparison Results.

| |

Hypothesis path |

Male |

Female |

diff.abs |

t-value |

p-value |

| (n=200) |

(n=200) |

| H1-6 |

Informativeness |

→ |

Utilitarian Value |

0.407 |

0.178 |

0.229 |

2.034 |

0.021 |

* |

| H2-2 |

Authenticity |

→ |

Hedonic Value |

0.094 |

0.340 |

0.246 |

1.911 |

0.028 |

* |

Generation -Based Group Comparison

The study conducted a comparative analysis between the MZ generation (n=245) and older generations (n=155), revealing significant differences across five pathways: expertise → utilitarian value (t=3.633, p=0.000), informativeness → utilitarian value (t=3.111, p=0.001), attractiveness → hedonic value (t=2.936, p=0.002), utilitarian value → purchase intention (t=3.376, p=0.000), and hedonic value → purchase intention (t=3.795, p=0.000).

The MZ generation demonstrated a heightened perception of utilitarian value when expertise was enhanced, whereas older generations exhibited a greater perception of utilitarian value when informativeness was increased. Furthermore, the MZ generation perceived a higher hedonic value in response to increased attractiveness, while older generations showed a negative response to attractiveness. The purchase intention of the MZ generation was more significantly influenced by hedonic value, in contrast to older generations, whose purchase intention was more strongly influenced by utilitarian value.

Table 6.

Generation-Based Group Comparison Results.

Table 6.

Generation-Based Group Comparison Results.

| |

Hypothesis path |

MZ |

Older |

diff.abs |

t-value |

p-value |

| (n=245) |

(n=155) |

| H1-3 |

Expertise |

→ |

Utilitarian Value |

0.278 |

-0.118 |

0.396 |

3.633 |

0.000 |

*** |

| H1-5 |

Informativeness |

→ |

Utilitarian Value |

0.130 |

0.434 |

0.304 |

3.111 |

0.001 |

** |

| H2-1 |

Attractiveness |

→ |

Hedonic Value |

0.322 |

-0.080 |

0.403 |

2.936 |

0.002 |

** |

| H3-1 |

Utilitarian Value |

→ |

Purchase

Intention |

0.342 |

0.624 |

0.282 |

3.376 |

0.000 |

*** |

| H3-2 |

Hedonic Value |

→ |

Purchase

Intention |

0.607 |

0.289 |

0.318 |

3.795 |

0.000 |

*** |

5. Conclusions

This study empirically examined the relationships between six content characteristics of virtual influencers and consumer purchase intention, with utilitarian and hedonic shopping values serving as mediating variables. The findings offer valuable insights for future developments in virtual influencer marketing.

Firstly, the content characteristics—attractiveness, expertise, playfulness, informativeness, and interactivity—were found to positively influence utilitarian value, with interactivity exerting the strongest effect, followed by informativeness, attractiveness, expertise, and playfulness. Authenticity did not demonstrate a significant effect on utilitarian value, likely because users recognize virtual influencers as artificial entities constructed through carefully crafted narratives.

Secondly, attractiveness, authenticity, playfulness, and interactivity positively influenced hedonic value, with playfulness being the most influential factor, followed by authenticity, interactivity, and attractiveness. In contrast, informativeness and expertise did not significantly impact hedonic value, as this type of value is more closely associated with pleasurable emotions during and after the shopping experience.

Thirdly, both utilitarian and hedonic values had significant positive effects on purchase intention, with hedonic value exhibiting a slightly stronger influence. This suggests that enjoyment plays a crucial role in satisfying social media users exposed to virtual influencer content, while practical value also contributes meaningfully to their purchase intentions.

Fourthly, gender differences revealed that males perceived higher utilitarian value when interactivity was emphasized, whereas females exhibited higher hedonic value when authenticity was prominent. These findings suggest that content strategies should be tailored according to gender-specific preferences.

Fifthly, generational differences indicated that the MZ generation (Millennials and Gen Z) perceived higher utilitarian value when expertise was emphasized, whereas older generations perceived higher utilitarian value when informativeness was emphasized. Furthermore, hedonic value had a stronger influence on the purchase intentions of the MZ generation, while utilitarian value was more influential for older generations. These findings underscore the necessity of adopting generationally differentiated content strategies.

Previous studies have primarily focused on human influencers or have limited their scope to the MZ generation, often emphasizing personal traits. This study expands upon prior research by including a more diverse demographic and conducting an empirical analysis on content-based factors, thereby providing deeper insights into virtual influencer effectiveness. The identification of gender and generational differences further supports the development of customized marketing strategies.

Despite these contributions, the study has certain limitations and proposes directions for future research. Currently, virtual influencers primarily operate on platforms such as Instagram and YouTube, which may limit the generalizability of content analysis. Future studies could investigate a broader range of content characteristics and extend the analysis to other behavioral outcomes such as purchase behavior or continued usage intention. Additionally, although virtual influencers are gaining traction, public skepticism and demographic limitations remain barriers to widespread acceptance. Further research from multidisciplinary perspectives is needed to enhance the public perception of virtual influencers and contribute to the long-term growth and maturity of this emerging industry.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. M.D. initiated this study and mainly contributed to data collection and statistical analysis. J.C. designed the research framework and evaluated final outcomes. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the 'Declaration of Helsinki' and involved collecting data through a questionnaire survey of participants, in accordance with 'Article 1 of the Bioethics and Safety Act of Korea.' However, ethical review and approval were not required for this study, as it qualifies as academic research without external funding. Even when participants are directly involved, they are not individually identified, and no sensitive information, as defined in Article 23 of the Personal Information Protection Act of Korea, is collected. This complies with the University's exception rule to IRB Screening.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van den Bulte, C.; Joshi, Y.V. New product diffusion with influentials and imitators. Marketing Science 2007, 26, 400–421. [CrossRef]

- Kadekova, Z.; Holienčinova, M. Influencer marketing as a modern phenomenon creating a new frontier of virtual opportunities. Communication Today 2018, 9, 90–104.

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y. Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues 2000, 56, 81–103. [CrossRef]

- Virtual Humans from. https://www.virtualhumans.org/#influencers. (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Moustakas, E.; Lamba, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Ranganathan, C. Blurring lines between fiction and reality: Perspectives of experts on marketing effectiveness of virtual influencers. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security); IEEE: 2020; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. Toward an ontology and ethics of virtual influencers. Australasian Journal of Information Systems 2020, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Kuanr, A.; Pahi, S.A.; Akram, M.S. Influencer marketing: When and why Gen Z consumers avoid influencers and endorsed brands. Psychology & Marketing 2023, 40, 27–47. [CrossRef]

- Fair Trade Commission, Republic of KOREA, 2022. Social Network Service (SNS) Unrevealed Monitoring Results of Unfair Advertising, Consumer Safety Information Division. http://www.ftc.go.kr/www/selectReportUserView.do?key=10&rpttype=1&report_data_no=9936 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Robinson, B. Toward an ontology and ethics of virtual influencers. Australasian Journal of Information Systems 2020, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. M.; Park, H. A.; Lim, S. Y. Attention behavior to mobile content: Focusing on exposure and involvement of pikicast content. Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2017, 17, 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. A.; Hong, S. S.; Park, Y. R. Virtual influencers’ impacts on brand attitudes and purchasing intention of services and products. Information Society and Media 2021, 22, 55–79.

- Gambetti, R. C.; Kozinets, R. V. From killer bunnies to talking cupcakes: theorizing the diverse universe of virtual influencers. European Journal of Marketing.; 2024; 58, 205-251. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y.; Heo, J. Y. Additional elements for delivering story context in virtual influencer content. In Proceedings of the Academic Presentation Conference of the Korean Design Society; 2023; No. 5, 250–251.

- Kim, J. R. Role of celebrity attractiveness in the formation of personal brand equity. Ph.D. Thesis, Dankook University Graduate School, 2016.

- Park, G.; Nan, D.; Park, E.; Kim, K.J.; Han, J.; Del Pobil, A.P. Computers as social actors? Examining how users perceive and interact with virtual influencers on social media. In Proceedings of the 2021 15th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM); IEEE: 2021; 1–6. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9377397.

- Molin, V.; Nordgren, S. Robot or human? The marketing phenomenon of virtual influencers: A case study about virtual influencers’ parasocial interaction on Instagram. Department of Business Studies, Uppsala University, 2019.

- Park, Y. B.; Kim, E. S. How perceived interactivity between virtual influencers and their followers and advertising type impacts the advertising effectiveness: Mediating role of authenticity. Journal of Advertising and Public Relations Korea 2022, 24, 5–42.

- Ohanian, R. Construction, and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising 1990, 19, 39–52. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J. H. The effect of influencers’ characteristics and consumer need satisfaction on attachment to influencer, contents flow and purchase intention Ph.D. Thesis, Keimyung University Graduate School, 2020.

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Seydel, J. B2C e-commerce web site quality: an empirical examination. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2005, 105, 645–661. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Ryu, S.; Han, I. The impact of Web quality and playfulness on user acceptance of online retailing. Information & Management 2007, 44, 263–275. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Koufaris, M. Perceptual antecedents of user attitude in electronic commerce. ACM SIGMIS Database: The Database for Advances in Information Systems 2006, 37, 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Watts-Sussman, S. Donkeys travel the world: Knowledge management in online communities of practice. In Proceedings of the Eighth Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS); 2002; pp. 2116–2127.

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J. Interactive advertising and presence: A framework. Journal of Interactive Advertising 2001, 1, 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Seol, S. C.; Shin, J. H. A The effects of interactivity, trust and perceived value on repurchase intention in internet shopping mall. Daehan Journal of business 2005, 18, 1457–1482.

- Sweeney, J. C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing 2001, 77, 203–220. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. S.; Cushion, B. The effect of shopping value on online purchase intention: the importance of product attributes as a parameter. Marketing Research 2004, 19, 41–69.

- Ahn, K. H.; Lim, B. H.; Jeong, S. T. The study of the effect of shopping value on customer satisfaction, and actual purchase behavior. Korean journal of marketing 2008, 10.2, 99-123.

- Park, J. H.; Jin, E. H. The influence of hedonic value in tourism shopping behavior. Korean Journal of Tourism Research 2007, 21, 121–138.

- Moon, Y. J.; Lee, J. H. A study on the effects of shopping value on trust and repurchase intention in open market : An analysis of moderating effects of social presence. Management Education Research 2010, 611, 227–248.

- Sánchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tourism Management 2006, 27, 394–409. [CrossRef]

- Park, K. R. The effect of information characteristics of agricultural product in mobile shopping on purchase intentions: focused on the mediation effect of consumer attitude and moderating effect of SNS WOM-behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Hoseo University Graduate School of Venture, 2020.

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Siqueira-Junior, J. R. Purchase intention and purchase behavior online: A cross-cultural approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04284.

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 1988, 52, 2–22. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Arnold, M.J. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating differential effects on retail outcomes. Journal of Business Research 2006, 59, 974–981. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1986, 51, 1173. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. H. A study on the intention to continuous use of self -driving cars based on advanced driver assistance system : Focused on highway driving assistant system. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Soongsil University, 2020.

- Dubé, L.; Morgan, M.S. Trend effects and gender differences in retrospective judgments of consumption emotions. Journal of Consumer Research 1996, 23, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Son, J. H.; Kim, C. S.; Lee, H. S. A study on the response of each generation to the communication characteristics of the MZ generation: Focusing on generation MZ, Generation X, and baby boomers. A Study in Communication Design 2021, 77, 202–215.

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 1988, 16, 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of marketing research, 1981, 18(3), 382-388. [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Tan, B.C.; Wei, K.K.; Saarinen, T.; Tuunainen, V.; Wassenaar, A. A cross-cultural study on escalation of commitment behavior in software projects. MIS Quarterly 2000, 24, 299–325. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).