1. Introduction

Virtual influencers, computer-generated characters with a presence on social media (Moustakas et al., 2020; Arsenyan and Mirowska, 2021), exhibit behavioral patterns akin to those of human influencers, amassing and leveraging their social media influence through online interactions(Moustakas et al., 2020). With the burgeoning popularity of virtual influencers, major brands are increasingly exploring opportunities for collaboration to promote their products. Notably, global brands such as Prada, Samsung, Porsche, Unilever, and Calvin Klein have utilized virtual influencers in their global branding campaigns(Oliveira and Chimenti, 2021). According to a survey by iiMedia Research(iiMedia Research, 2023), the market size of China’s virtual person-driven industry was approximately 186.61 billion yuan in 2022, with a core market size of 12.08 billion yuan. Projections for 2025 estimate a market size of 640.27 billion yuan and a core market size of 48.06 billion yuan, indicating a robust growth trend. This data underscores the significant potential and expanding influence of virtual influencers in the marketing landscape.

In the face of the rich practice of virtual influencer marketing, a growing body of research has focused on its successful aspects, such as perceived credibility(Riedl et al., 2014), persuasiveness in the context of storytelling(Faddoul and Chatterjee, 2020), perceived authenticity(Moustakas et al., 2020; Oliveira and Chimenti, 2021), perceived novelty(Franke et al., 2023), as well as audience reactions to virtual influencers on social media have been examined (Arsenyan and Mirowska, 2021). These studies effectively illustrate that virtual influencers (vs. human influencers) have a positive impact on purchase intentions (Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández, 2019; Gerlich, 2023). However, reports of negative effects of virtual influencer marketing have also emerged in practice. For instance, the internationally popular virtual idol, Miquela, posted a photo on her Instagram account of “herself” enjoying a vegetable salad, captioned, “You wouldn’t want to know how a robot digests kale.” This led to a flurry of comments from netizens questioning how a virtual idol could eat, indicating that people find it difficult to imagine a virtual idol’s “taste experience” (Instagram, 2022). A similar case occurred with the domestic virtual internet celebrity, Ling, who shared a photo on social media of herself wearing Gucci lipstick and used touch to appeal for endorsements. The response from consumers was negative, with doubts about whether Ling truly had the ability to feel the “touch experience” of the lipstick (Zhou et al., 2023). These cases are not isolated and may even represent a common phenomenon. On the surface, this seems to be an issue of perceived credibility as mentioned by Riedl et al.(Riedl et al., 2014), but many studies suggest that virtual influencers can enhance perceived credibility(Gerlich, 2023; Lim and Lee, 2023). Therefore, a new theoretical explanation is needed for the negative effects produced by virtual influencer marketing.

According to the theory of active inference, perception is an active process, meaning that the intrinsic perception guiding consumers’ evaluation and selection of products is constantly updated through consumer behavior(Friston, 2018). For example, in offline scenarios, consumers naturally touch, move, and try out products before purchasing, generating sensory feedback that guides internal perception. In online scenarios, consumers also engage in mental simulation and self-association based on the subjective experiences and behaviors of the influencers. In addition, according to the dual cognitive control theory, consumers’ cognition of various aspects of a product, such as its appearance, functionality, and performance, is actually perceived through two modes of product control: proactive control and reactive control(Aguerre et al., 2021). Specifically, consumers actively collect and process product-related information before purchasing and actively adjust their perception and behavior after receiving product information, thereby forming a perception of product autonomy, i.e., perceived product control. Therefore, this paper hypothesizes that when Miquela and Ling share photos of eating vegetable salad and applying lipstick online, consumers firmly believe that they lack human taste and tactile perception. They find it difficult to self-associate based on their sensory descriptions, and thus cannot perceive product control (behavioral control and cognitive control), resulting in negative attitudes.

Based on the above analysis, this study aims to answer two questions: (1) What role does consumers’ perception of control play in the effectiveness of virtual influencer marketing? (2) Under product conditions that rely on different sensory experiences, do virtual influencers enhance consumers’ perception of control by having more dominant senses, which in turn influences the effect? This study will deepen the understanding of the mechanisms and boundary conditions that explain the effects of virtual (vs. human) influencer marketing and provide empirical evidence for the design of product selection and information presentation for virtual influencer marketing.

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Virtual Influencer Marketing

The emergence of virtual influencers can be traced back to the early 1990s, primarily characterized by cartoon figures, with the earliest virtual celebrities and idols launched in Japan. These early virtual idols were not generated by computer programs. It wasn’t until 2007 that the computer-program-generated virtual idol “Hatsune Miku” appeared, marking the advent of a new era for virtual influencers and paving the way for future virtual influencers(Gerlich, 2023). In 2016, Kizuna AI, a virtual YouTube user, made her debut, creating content and interacting with audiences on YouTube, quickly attracting a large number of subscribers. As a successful example, she demonstrated the significant influence of virtual influencers on audiences. Subsequently, it was found that virtual influencers are sometimes more appealing than human influencers, possibly because they can provide a unique interactive experience while avoiding certain limitations present in the human world, hence their increasing popularity (Sands et al., 2022).

In recent years, the impact of virtual influencers on consumer behavior has garnered widespread attention in academia. For instance, studies have shown that compared to human influencers, virtual influencers can enhance brand loyalty through personalized consumer experiences. Specifically, they can be designed to align with the expected image of different cultural, gender, or age groups, thereby better attracting and influencing these audiences(Sands et al., 2022). Furthermore, virtual influencers can help brands expand their influence and increase their visibility by providing authentic information, creating emotional connections, encouraging participation, and fostering relevance and trust(Gerlich, 2023; Kim and Park, 2023; Mirowska and Arsenyan, 2023). The explanatory mechanisms primarily focus on perceived credibility (Riedl et al., 2014), perceived novelty(Franke et al., 2023), perceived authenticity (Moustakas et al., 2020; Oliveira and Chimenti, 2021), and persuasiveness in the context of storytelling (Faddoul and Chatterjee, 2020).

From the above, while existing research acknowledges the numerous positive impacts brought about by virtual influencers, the emergence of virtual influencers is a result of breakthroughs in computer technology. This implies that their application is inevitably limited by the technology itself, and the use of virtual influencer marketing inherently has its limitations (Moustakas et al., 2020). Numerous practical cases corroborate this viewpoint. For example, the negative reactions of consumers to the behaviors of the aforementioned virtual influencers, Miquela and Ling, serve as clear evidence. At present, this limitation has not been given sufficient attention in academia. Only a handful of studies have explored the positive impact of virtual (vs. human) influencers on purchase intentions (Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández, 2019; Gerlich, 2023), but the underlying explanatory mechanisms and boundary conditions have yet to be addressed. This highlights the need for further research in this area.

According to the theory of active inference, the intrinsic perception that guides consumers in evaluating and selecting products is continually updated through consumer behavior(Friston, 2018). In offline scenarios, consumers use their own senses to perceive products, while online, consumers empathize with influencers, mentally simulating and self-associating with their subjective experiences and behaviors, thereby achieving the goal of perceiving product control. Evidently, consumers are well aware that virtual influencers are not “of the same kind” after all, and currently, there is no scientific evidence to show that “they” have exactly the same sensory experience as “we” do. This inevitably leads consumers to be unable to empathize with them, only able to perceive a lower level of product control (behavioral control and cognitive control), resulting in negative attitudes. Therefore, this paper aims to discuss how consumers’ perception of control differs due to the sensory differences between virtual (vs. human) influencers, leading to different purchase intentions.

2.2. Consumer Perceived Control

With the advancement of new media technology, consumers are actively participating in value creation and delivery. This active participation enhances consumers’ control over their experiences with products and services(Esmark et al., 2016). Classical literature suggests that there are three types of control: behavioral control, cognitive control, and decision control(Averill, 1973).

Behavioral control is defined as direct action on the environment and refers to consumers’ perceptions of what they can do to influence a specific situation(Averill, 1973). In new media research, behavioral control reflects consumers’ views on the ease or difficulty of behavior in specific situations(Sembada and Koay, 2021). For example, during the process of watching a live broadcast, consumers decide when to start watching, when to end, and whether to interact, all of which are direct controls of their own behavior. Existing literature shows that giving consumers a higher level of autonomy (i.e., behavioral control) in certain processes and situations can improve their satisfaction and reduce their negative feelings(Mills and Krantz, 1979; Dabholkar, 1996). Cognitive control refers to consumers’ evaluation and integration of given information to predict and explain the next action in a specific situation(Averill, 1973; Kim et al., 2019). For example, during the process of watching a live broadcast, consumers need to process and filter a large amount of information, determining which products they need and which they do not. This process requires consumers to utilize their cognitive resources to process information and make decisions. The live broadcast scenario not only allows for human-time interaction but also personalized recommendations, which help them understand the situation more easily, thereby perceiving a higher level of cognitive control(Kim et al., 2019). In addition, richer visual information about a product can help consumers understand and predict a situation, and access to such information also enhances cognitive control(Fennis and Bakker, 2001). Decision control is the extent to which consumers believe that they are able to choose between alternatives or multiple options(Mcmillan, 2002). For example, consumers need to make a purchase decision based on factors such as their needs and budget, a process that constitutes decision control.

According to the ego depletion theory, the control-like resources possessed by an individual are essential for the individual to perform self-control-like activities. If an individual depletes control-type resources during a previous self-control-type activity, the control-type resources cannot be recovered within a short period of time, thus impairing the completion of the subsequent self-control-type task(Bratslavsky et al., 1998). In this study, because consumers are convinced that virtual (vs. human) influencers do not have sensory experiences similar to their own, the lack of sensory experience of virtual influencers can reduce or “deprive” consumers of their perceived control, forcing the process of product perception to be interrupted, and naturally, they will not generate purchase intentions. Moreover, this paper only discusses purchase intentions and does not involve factors such as budget in purchase decisions, so decision control is not included in the research scope. The main focus is on the impact of behavioral control and cognitive control on consumer behavior.

2.3. Virtual Influencer Marketing and Consumer Perceived Control

A wealth of research has demonstrated that influencers can significantly impact others’ behaviors and enhance consumers’ purchase intentions (Lajnef, 2023). However, recently, with the frequent failures of human influencers and the continuous breakthroughs in computer technology, virtual influencers are increasingly being introduced into the marketing field, and academic attention to virtual influencers is growing(Oliveira and Chimenti, 2021). Studies show that customers are increasingly attracted to virtual influencers, who are considered more trustworthy, credible, and in line with customer preferences compared to human influencers, leading to an increase in purchase intentions(Gerlich, 2023). However, there is scant research on the intrinsic mechanisms of how virtual influencers enhance consumers’ purchase intentions in the consumption environment. This paper proposes that, compared to human influencer marketing, the increasingly popular virtual influencer marketing may make consumers perceive a higher level of behavioral control ability, mainly for the following reasons.

Firstly, interactivity. Virtual influencers can provide 24-hour, uninterrupted service and interact with consumers in human time. Consumers can decide when to start watching, when to end, and whether to interact, etc.(Arsenyan and Mirowska, 2021), all of which greatly enhance consumers’ direct control over their own behavior. Secondly, personalization. A brand may rapidly develop an endless number of virtual influencers, even completely personalized influencers (custom-made for each customer, with virtual influencers targeted at them). These personalized influencers offer hyper-personalized products or services that may take into account customer preferences and may even show them the corresponding ideal image(Sands et al., 2022). Undoubtedly, according to the ego depletion theory, this personalized recommendation and interaction can save resources and energy for consumers when they feel tired and at a loss in the face of many choices, gaining more behavioral control(Kim et al., 2019). Thirdly, reliability and predictability. Compared with human influencers, virtual influencers are considered to have a high degree of reliability and predictability, which is one of the main reasons why they are attractive(Gerlich, 2023). For example, since virtual influencers will not have scandals or negative news, consumers do not need to worry about being negatively affected by following a certain influencer, which may make consumers feel more at ease and have a greater sense of control over their own behavior(Gerlich, 2023). Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis.

H1. Compared with human influencers, virtual influencers will make consumers perceive a higher level of behavioral control.

From the above, virtual (vs. human) influencers may lead consumers to perceive higher levels of behavioral control in terms of interactivity, personalization, reliability, and predictability. Research has shown that consumers generate more positive purchase decisions when they perceive higher levels of behavioral control(Esmark et al., 2016), and that virtual influencers with higher personalization strengthen consumers’ attachment to the brand, which in turn affects continuous purchase intentions(Kim and Park, 2023). Therefore, this study hypothesizes that virtual influencers may enhance consumers’ perceived behavioral control, thereby positively influencing their continuous purchase intentions. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2. Behavioral control mediates the relationship between virtual influencers and continuous purchase intentions.

In consumer behavior research, cognitive control is considered a crucial factor influencing consumers’ purchase decisions. Cognitive control implies an individual’s ability to predict the next step and understand the situation while performing a task. This ability can assist consumers in better processing information during the purchasing process, thereby making more rational and satisfactory purchase decisions(Averill, 1973; Kim et al., 2019). According to the literature, the engagement of virtual influencers is almost three times that of human influencers(Mirowska and Arsenyan, 2023), and compared to human influencers, virtual influencers have higher controllability and flexibility. They can provide a richer and more personalized shopping experience, thereby helping consumers better understand products and purchasing situations(Sands et al., 2022; Gerlich, 2023). This provision of rich information may enhance consumers’ cognitive control. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis.

H3. Compared with human influencers, virtual influencers will make consumers perceive a higher level of cognitive control.

Research indicates that cognitive control has a positive impact on online and mobile shopping (Unni and Harmon, 2007). Specifically, when consumers obtain information that helps them understand a situation, they find it easier to make purchase decisions(Fennis and Bakker, 2001). Therefore, virtual influencers, by enhancing consumers’ perceived cognitive control, may further influence consumers’ continuous purchase intentions. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4. Cognitive control mediates the relationship between virtual influencers and continuous purchase intentions.

2.4. Regulatory Role of Sensory Experience

From the above, the virtual influencers’ negative reactions are mainly due to the lack of “sensory experience”, which is an important criterion for product categorization. Based on this, this study hypothesizes that product types based on different senses may moderate the effectiveness of virtual influencers. According to the dependence on sensory experience, products can be divided into two categories: one is products with geometric attributes. The characteristics of these products can be well conveyed through language. For example, televisions, mobile phones, or laptops. The size, shape, color, etc., of these products can be understood by consumers through information processing. The second is products with material attributes. These products need to be physically inspected through our sense of touch and smell. For example, the scent of a perfume, the taste of a piece of chocolate, or the texture of a piece of clothing(Degeratu et al., 2000; McCabe and Nowlis, 2003; Grohmann et al., 2007).

Compared to products with geometric attributes, sensory perceptions play a more significant role in products with material attributes(McCabe and Nowlis, 2003). This suggests that different types of influencers may have varying effects when promoting different types of products. For instance, when the product or service endorsed by a virtual (vs. human) influencer focuses on distal (vs. proximal) sensory experiences, consumers have a higher purchase intention for the endorsed product or service(Zhou et al., 2023). It is evident that, compared to human influencers, virtual influencers can take advantage of the rapid information processing and geometric shape presentation in the digital environment to perfectly display the geometric attributes of the product(Sanak-Kosmowska and Wiktor, 2020). In contrast, human influencers, compared to virtual influencers, can utilize their tactile and olfactory experiences to describe and evaluate the material attributes of the product. Therefore, in conjunction with hypotheses H1-H4, this study speculates that human influencers may be better at handling material attributes, while virtual influencers may be better at handling geometric attributes, thereby enabling consumers to perceive a higher level of behavioral control and cognitive control, and influencing their continuous purchase intention. In summary, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

H5. In terms of material attributes, human influencers are more capable of stimulating behavioral control and cognitive control, thereby influencing continuous purchase intention.

H6. In terms of geometric attributes, virtual influencers are more capable of stimulating behavioral control and cognitive control, thereby influencing continuous purchase intention.

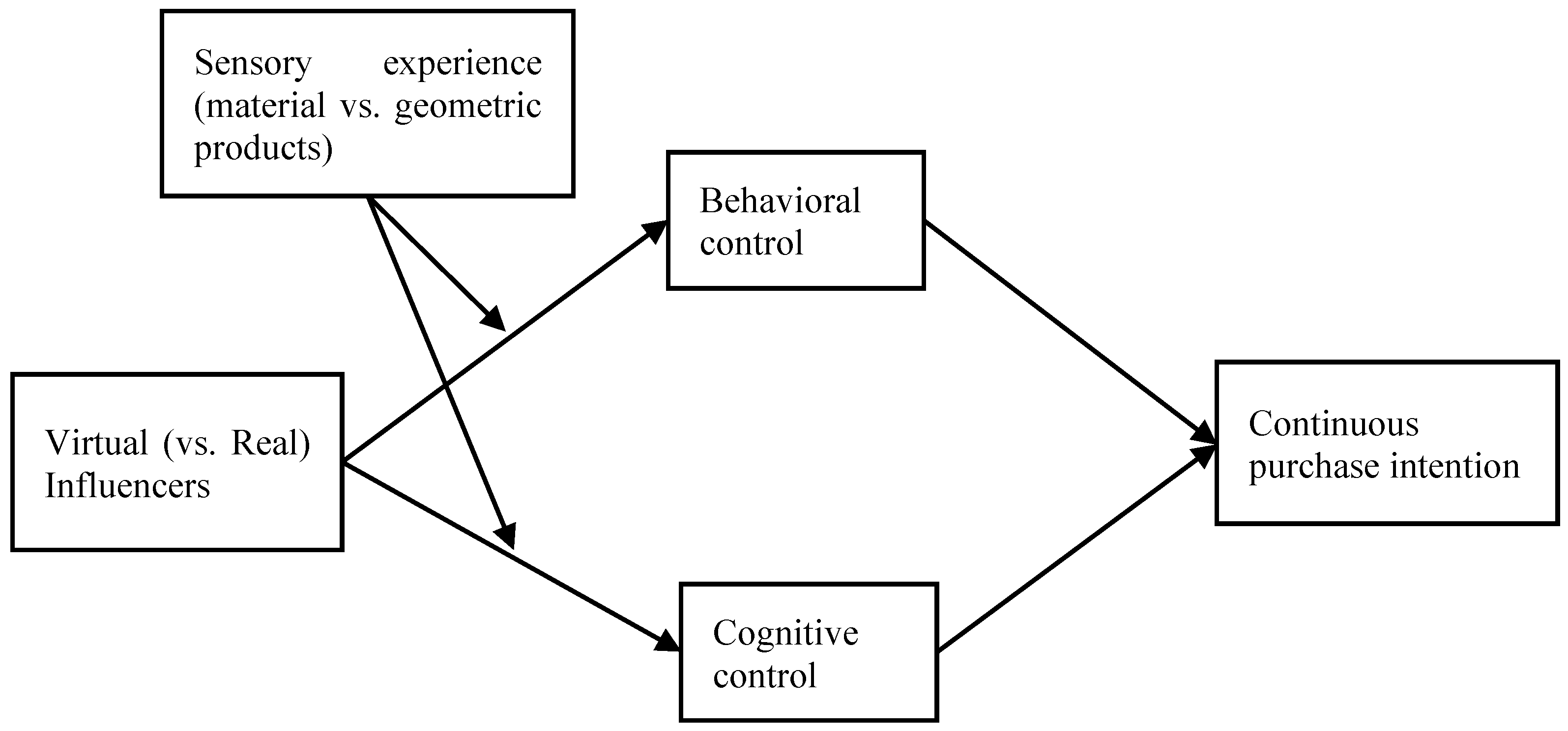

Combining hypotheses H1-H6, the research framework of the study is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Study 1

Study 1 adopts a single-factor (influencer type: virtual vs. human) between-group experimental design. The purpose is to explore the influence of influencer type (virtual vs. human) on consumer control (behavioral control and cognitive control), to validate H1 and H3, and to demonstrate that the influence of influencer type (virtual vs. human) on continuous purchase intention is achieved through consumers’ cognitive control and behavioral control, validating H2 and H4.

3.1.1. Method

All respondents were randomly assigned to one of the groups (virtual influencer group vs. human influencer group). First, respondents would see a fictitious influencer profile created for this study: “Rico is a (virtual) influencer who debuted this year. Rico, also known as Coco, was born on March 21, 2001, in a coastal city. She joined Maxi Entertainment Company in 2019 and debuted as a (virtual) singing and dancing idol in May 2020. Her representative music works include ‘Youth Waltz’, ‘Dream Ferris Wheel’, ‘Ready’, etc. Since her debut, Rico has attracted many fans. She has her own style of dressing and always keeps up with fashion trends. Rico also shares her daily life on social media. Rico is curious about everything. She likes all objects in the shape of a cat. Her favorite entertainment project is roller coasters.”

In both sets of materials, apart from Rico being described as a virtual or human influencer, the other content is basically similar. This profile refers to successful past research(Zhou et al., 2023). To ensure that respondents truly understand that Rico is a “virtual person”, in the virtual influencer group, respondents were also informed that “Virtual influencers (internet celebrities) are digital characters created in computer graphics software, not human people. They adopt a first-person perspective and have influence on social media.” After reading this profile, respondents need to fill in a seven-point scale about continued purchase intention, behavioral control, and cognitive control. This study made appropriate adaptations to the continuous purchase intention(Koo and Ju, 2010), behavioral control, and cognitive control(Mcmillan, 2002; Whang et al., 2021). Respondents need to report personal information such as age, gender, etc.

3.1.2. Results

1. Demographic Variables Statistics and Manipulation Check

The experiment was conducted on the Questionnaire Star platform in October 2023, with a total of 200 participants recruited. After excluding unqualified samples such as those with too short response times, a total of 192 valid samples were obtained. The specific sample characteristics are shown in

Table 1. There were no significant differences in various demographic information on the research variables.

2. Reliability and validity analysis

The reliability of each scale was tested using Cronbach’s α coefficient. The results showed that the Cronbach’s α values for behavioral control, cognitive control, and continued purchase intention were 0.855, 0.858, and 0.859, respectively, all of which are higher than 0.7, indicating that each scale has a good level of reliability. In addition, validity was tested. In terms of convergent validity, the AVE values for the scales of behavioral control, cognitive control, and continued purchase intention were 0.656, 0.671, and 0.675, respectively, all of which are higher than the threshold value of 0.5, indicating that the scales used all have good convergent validity. In terms of content validity, all research variables come from mature literature, thus, they also have good content validity. The specific measurement values are shown in

Table 2.

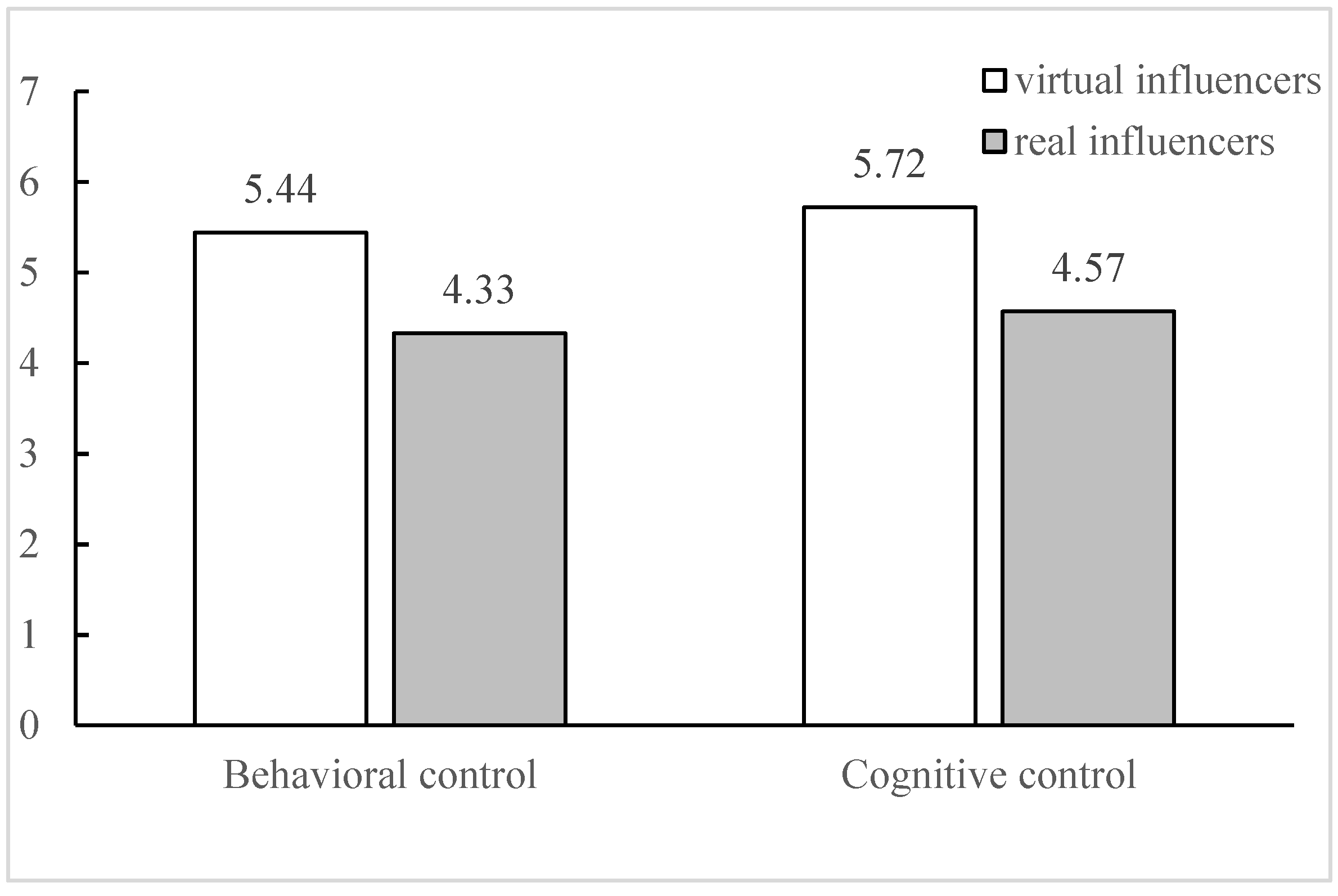

3. Independent samples t-test

To examine the effect of influencer type (virtual vs. human) on behavioral control and cognitive control, this study conducted an independent samples t-test. The data analysis results showed that compared with the respondents in the human group (M

human influencer=4.33, SD=1.09), the perceived behavioral control of the respondents in the virtual group (M

virtual influencer=5.44, SD=0.93) was higher (t=7.607, p<0.001); compared with the respondents in the human group (M

human influencer=4.57, SD=1.04), the perceived cognitive control of the respondents in the virtual group (M

virtual influencer=5.72, SD=0.7) was higher (t=8.970, p<0.001). Therefore, hypotheses H1 and H3 are supported; that is, compared with human influencers, virtual influencers can make consumers perceive a higher level of behavioral control and cognitive control capabilities when promoting products, the results are shown in

Figure 2.

4. Mediation Test

To verify the mediating role of behavioral control and cognitive control in the influence of influencer type on continued purchase intention, this study will use the Bootstrap test method for analysis, drawing on existing literature(Zhao et al., 2010; Hayes, 2013). The analysis steps are as follows: First, in SPSS 26.0, select PROCESS in regression analysis, choose influencer type as the independent variable, continued purchase intention as the dependent variable, and select behavioral control and cognitive control as mediating variables. Then, select model 4, set the sample size to 5000, and set the confidence interval to 95%. Through analysis, the results show that the mediating path of “influencer type - behavioral control - continued purchase intention” is significant (effect = -0.615, 95%CI, LLCI= -0.359, ULCI=-0.204, does not include 0); the mediating path of “influencer type - cognitive control - continued purchase intention” is significant (effect = -0.440, 95%CI, LLCI= -0.276, ULCI=-0.137, does not include 0); and both paths are complete mediations, indicating that influencer type will influence continued purchase intention entirely through the mediating variables (behavioral control and cognitive control). Therefore, hypotheses H2 and H4 are supported.

3.2. Study 2

Study 2 adopts a 2 (influencer type: virtual vs. human) × 2 (product type: material attributes vs. geometric attributes) two-factor between-group experimental design. The purpose is to demonstrate that the influence of influencer type (virtual vs. human) on continuous purchase intention is moderated by product type, thereby validating H5 and H6.

3.2.1. Method

Respondents were randomly assigned to different experimental groups. Each group of respondents first read the virtual (vs. human) influencer profile presented in Experiment 1, and then saw the material (vs. geometric) attribute product promoted by the virtual (vs. human) influencer. The product design refers to successful past experiments, and the selected product is a home styling product. Because this type of product is more practical and can arouse the interest of each respondent(McCabe and Nowlis, 2003). The experimental product for material attributes is a leisure chair, because its material softness and touch are very important when evaluating the product, as shown in

Figure 3. The experimental product for geometric attributes is a design sense vase. Consumers only need to observe the product to identify its shape and other attributes, as shown in

Figure 4. After understanding the influencer profile and product type, respondents were asked to fill in the scales of continuous purchase intention, behavioral control, and cognitive control, as well as personal information such as age and gender.

3.2.2. Results

1. Demographic Variables Statistics and Manipulation Check

In October 2023, the experimenter recruited 400 respondents on the Questionnaire Star platform to participate in the experiment. After excluding unqualified samples such as those with too short response times, a total of 388 valid samples were obtained. The specific sample characteristics are shown in

Table 3. There were no significant differences in various demographic information on the research variables.

2. Moderation Effect Test

(1) To test the moderating role of product type in the influence of influencer type on behavioral control, a two-way ANOVA was conducted with influencer type and product type as independent variables and behavioral control as the dependent variable. The results showed that the interaction between influencer type and product type had a significant effect on behavioral control (F(1,385)=10310.51, p<0.001). To more intuitively judge the moderating effect, the experiment also conducted a simple effect test of behavioral control at each level of influencer type and product type. The data results showed that when respondents were under material attribute products, there was a significant difference in the influence of influencer type on behavioral control (F=10.535, p<0.001). Compared with virtual influencers (M material attribute product-virtual influencer=5.13, SD=0.96), human influencers (M material attribute product-human influencer=5.55, SD=0.82) made respondents perceive higher behavioral control. When respondents were under geometric attribute products, there was also a significant difference in the influence of influencer type on behavioral control (F=55.332, p<0.001). Compared with human influencers (M geometric attribute product-human influencer=4.18, SD=1.15), virtual influencers (M geometric attribute product-virtual influencer=5.27, SD=0.89) made respondents perceive higher behavioral control. In summary, product type moderates the influence of influencer type on perceived behavioral control.

(2) To test the moderating role of product type in the influence of influencer type on cognitive control, a two-factor analysis of variance was conducted with influencer type and product type as independent variables and cognitive control as the dependent variable. The results showed that the interaction between influencer type and product type had a significant effect on cognitive control (F(1,385)=11743.177, p<0.001). To more intuitively judge the moderating effect, the experiment also conducted a simple effect test of cognitive control at each level of influencer type and product type. The data results showed that when respondents were under material attribute products, there was a significant difference in the influence of influencer type on cognitive control (F=8.672, p<0.01). Compared with virtual influencers (M material attribute product-virtual influencer=5.53, SD=0.77), human influencers (M material attribute product-human influencer=5.83, SD=0.66) made respondents perceive higher cognitive control. When respondents were under geometric attribute products, there was also a significant difference in the influence of influencer type on cognitive control (F=78.178, p<0.001). Compared with human influencers (M geometric attribute product-human influencer=4.24, SD=1.13), virtual influencers (M geometric attribute product-virtual influencer=5.52, SD=0.87) made respondents perceive higher cognitive control. In summary, product type moderates the influence of influencer type on perceived cognitive control.

3. Moderated mediation test

Based on the hypotheses, this study posits that perceived behavioral control and cognitive control mediate the interaction effect of influencer type and product type on continuous purchase intention. Therefore, following the mediation effect analysis procedure proposed by Zhao et al.(2010), and using the Bootstrap method proposed by Hayes(2013), the PROCESS plugin in SPSS 26.0 is used to test the mediation effect. In actual operation, model 7 is selected, the sample size is set to 5000, and the confidence interval is set to 95% for analysis. Continuous purchase intention is taken as the dependent variable, influencer type as the independent variable, product type as the moderating variable, and behavioral control and cognitive control as the mediating variables.

The results of the data analysis indicate that when behavioral control and cognitive control are used as mediating variables for moderated mediation effect analysis, the data results are significant (index of behavioral control = 0.815, 95% CI, LLCI = 0.548, ULCI = 1.131; index of cognitive control = 0.244, 95% CI, LLCI = 0.088, ULCI = 0.415). Specifically, when the product type is a geometric attribute (effect = -0.592, 95% CI, LLCI = -0.809, ULCI = -0.403, does not include 0) and a material attribute (effect = 0.225, 95% CI, LLCI = 0.084, ULCI = 0.390, does not include 0), the indirect effects are significant but the signs are opposite, indicating that the product type plays a moderating role. Similarly, when the product type is a geometric attribute (effect = -0.534, 95% CI, LLCI = -0.734, ULCI = -0.354, does not include 0) and a material attribute (effect = 0.126, 95% CI, LLCI = 0.039, ULCI = 0.227, does not include 0), the indirect effects are significant but the signs are opposite, indicating that the product type plays a moderating role.

As shown in

Table 4, geometric attribute products are positively correlated with virtual influencers, while material attribute products are positively correlated with human influencers. This suggests that for geometric attribute (material attribute) products, the behavioral control and cognitive control stimulated by virtual influencers (human influencers) are stronger, leading to a higher continuous purchase intention.

4. Discussion

In the increasingly fierce market competition, virtual influencers have gradually become an effective tool for influencer marketing. This study shows through two experimental studies that virtual influencers and human influencers can make consumers perceive different levels of control, thereby affecting purchase intentions. The perception of control also comes from consumers’ perception of similarity between themselves and the virtual (vs. human) influencer. Under the regulation of different sensory-dominant product types, virtual (vs. human) influencers have different intensities of control perception for different types, ultimately affecting continuous purchase intention. Specifically, the main conclusions are in the following two aspects.

First, virtual (vs. human) influencers make consumers have a stronger sense of control. Compared with human influencers, because virtual (vs. human) influencers have stronger attributes such as interactivity, personalization, reliability, and predictability, they make consumers perceive higher behavioral control and cognitive control, making consumers have a stronger sense of control over purchase choices, such as stronger service responsiveness, better meeting their personalized needs, lower risk perception, etc. This theoretically partially explains the reason for the rapid rise of virtual (vs. human) influencers.

Second, the level of control perception is limited by sensory experience. The control perception provided by virtual (vs. human) influencers has limitations. When they endorse some experience products that require human senses to provide, their provided control perception is greatly discounted because consumers believe that virtual influencers still cannot have sensory experiences similar to humans. This study shows that because geometric attribute products need to describe their appearance and function through vision and information processing, virtual influencers can use their advantages in quickly processing information and presenting geometric shapes in the digital environment to perfectly display such products, thereby enhancing consumers’ control perception and positively affecting continuous purchase intention. And material attribute products need actual inspection of smell or touch, human influencers are better able to use tactile and olfactory experiences to describe and evaluate material attribute products, thereby enhancing consumers’ control perception and positively affecting continuous purchase intention. This not only explains the reason why virtual influencers “overturned” in some situations, but also predicts the use of virtual influencers from the perspective of control theory.

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The theoretical contributions of this paper are mainly reflected in the following two aspects:

First, it expands the mechanism of the influencer type’s impact on consumers. Existing research focuses on how virtual influencers (vs. human influencers) help brands expand their influence and increase their popularity(Gerlich, 2023; Kim and Park, 2023; Mirowska and Arsenyan, 2023), and enhance brand loyalty through personalized consumer experiences(Sands et al., 2022). The main explanation mechanisms focus on perceived credibility(Riedl et al., 2014), perceived novelty (Franke et al., 2023), perceived authenticity, etc.(Moustakas et al., 2020; Oliveira and Chimenti, 2021), but when these factors can play a role has not been theoretically answered. This study answers this question well through the perception of control. Due to the different characteristics of different types of influencers (virtual influencers vs. human influencers), such as interactivity, personalization, reliability, and predictability, they bring about vastly different perceptions of control over purchasing behavior for consumers, thereby generating different purchase intentions. This to some extent responds to the issues of explanatory mechanisms and boundary conditions proposed by Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández(2019) and Gerlich(2023).

Second, it verifies the moderating mechanism of influencer type and control. To better verify the impact of control perception, this study uses product types that rely on different sensory experiences as moderating variables to verify the impact of influencer type on the level of control perception. The results show that when virtual influencers sell material attribute products that rely on smell and touch experiences, consumers have a low level of control perception and thus produce negative reactions. This perfectly explains the negative reactions of consumers to Miquela and Ling’s online sharing of vegetable salad and lipstick photos. However, when presenting geometric attribute products that rely on vision and information processing, the advantages of virtual influencers are obvious, enhancing consumers’ perception of control and leading to higher continuous purchase intention. These conclusions not only support the view of Zhou et al.(2023), that close sensory cues may cause consumers to have negative attitudes towards virtual celebrity endorsements of products and services, but also more deeply explain when factors such as perceived credibility(Riedl et al., 2014) can enhance the marketing effect of virtual (vs. human) influencers.

4.2. Managerial Implications

Enhancing the perception of consumer control can improve the marketing effectiveness of virtual influencers. As an emerging marketing tool, virtual influencers have many advantages, such as adapting to the needs of different groups, no time and space constraints, no scandals, etc. Therefore, companies can perfectly design their information presentation, appearance, voice tone, etc. They will not incur travel expenses; they can easily customize, providing a wide range of adaptability(Moustakas et al., 2020). Companies should use these advantages to enhance the perception of consumer control, such as providing 7×24 hours of service, information interaction and tracking reports in the purchase process, more accurate and comprehensive product information, more personalized services, more scientific evidence, etc., to help consumers save resources, such as time, energy, etc., reduce the loss of consumer control resources, enhance the perception of consumer control, enhance consumer recognition of virtual influencers, and increase purchase intention.

Using consumer sensory experience to select the product category of virtual influencers. When choosing products, people rely heavily on sensory experience to collect information and make judgments(Jusiuk, 2023). Although virtual influencers surpass human senses in some aspects, they cannot yet have a similar human sensory experience. When selling geometric products, companies should make more use of the advantages of virtual influencers in processing information and presenting geometric shapes in the digital environment, display and explain products, enhance consumer perception control and purchase intention; when endorsing material attribute products, they should use the advantages of human influencers in smell and touch, etc., to enhance consumer control. In fact, more products are difficult to distinguish with geometric attributes and material attributes. Companies should carefully design the information presentation of different types of influencers, cooperate with each other, complement each other, develop a new mode of “human anchor + virtual anchor” linkage live broadcast, comprehensively enhance the perception of consumer control, and achieve satisfactory marketing results. This also predicts the future direction of efforts for virtual influencer developers, that is, to try to narrow the sensory experience gap between virtual influencers and human influencers.

5. Directions for Future Research

Consumer perception has many dimensions, and control is just one of them. Future research can further explore other dimensions of consumer perception to enrich the mechanism of virtual influencers’ impact on purchase intention, to adapt to the humanity of different product classification methods, such as hedonic products and utilitarian products, because hedonic products are more likely to bring a higher level of perceived ownership(Dhar and Wertenbroch, 2000). The current study classifies products into material attribute products and geometric attribute products, but many products are difficult to distinguish between material attributes and geometric attributes, such as clothing(Vonkeman et al., 2017). Future research can focus on the interaction of the characteristics of virtual influencers and human influencers on marketing effects, such as the impact of information presentation, image design, product type, and other factors. The current study mainly uses online surveys, and future studies can also use laboratory experiments and field experiments to further verify the reliability of the conclusions of this study.

Author Contributions

Min Tian played a lead role in the conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology design, and writing of the original draft. Peng Chen provided essential support during the research and writing of the original draft. Professor Sigen Song played a key role in conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing review. Professor Meimei Chen played an equal role in conceptualization, supervision, and writing the review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Donghua University. All participants provided informed consent prior to their participation. They were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their involvement, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Measures were taken to ensure participant anonymity and confidentiality throughout the study. No personally identifiable information was collected, and all data were anonymized during analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguerre, N.V.; Bajo, M.T.; Gómez-Ariza, C.J. Dual mechanisms of cognitive control in mindful individuals. Psychol. Res. 2020, 85, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenyan, J.; Mirowska, A. Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2021, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, J.R. Personal control over aversive stimuli and its relationship to stress. Psychol. Bull. 1973, 80, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratslavsky, E. , Muraven, M., and Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74, 1252–1265.

- A Dabholkar, P. Consumer evaluations of new technology-based self-service options: An investigation of alternative models of service quality. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeratu, A.M.; Rangaswamy, A.; Wu, J. Consumer choice behavior in online and traditional supermarkets: The effects of brand name, price, and other search attributes. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2000, 17, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Wertenbroch, K. Consumer Choice between Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmark, C.L.; Noble, S.M.; Bell, J.E.; Griffith, D.A. The effects of behavioral, cognitive, and decisional control in co-production service experiences. Mark. Lett. 2015, 27, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faddoul, G.; Chatterjee, S. A Quantitative Measurement Model for Persuasive Technologies Using Storytelling via a Virtual Narrator. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2020, 36, 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, B.M.; Bakker, A.B. “Stay Tuned—We Will Be Back Right after these Messages”: Need to Evaluate Moderates the Transfer of Irritation in Advertising. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Müller, K. Consumers’ Responses to Virtual Influencers as Advertising Endorsers: Novel and Effective or Uncanny and Deceiving? J. Advert. 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J. Active Inference and Cognitive Consistency. Psychol. Inq. 2018, 29, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlich, M. The Power of Virtual Influencers: Impact on Consumer Behaviour and Attitudes in the Age of AI. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, B.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Sprott, D.E. The influence of tactile input on the evaluation of retail product offerings. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach 1, 20.

- iiMedia Research (2023). China Virtual Idol Industry Development Research Report 2023. Available at: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/92516.html [Accessed , 2023]. 27 November.

- Instagram (2022). You don’t wanna know how robots digest kale. Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CiVxBRUP3g1/ [Accessed , 2023]. 27 November.

- Jiménez-Castillo, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, R. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusiuk, P. Influence of Pro-Environmental Attitudes on the Choice between Tangible and Virtual Product Forms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. Virtual influencers’ attractiveness effect on purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of the Product–Endorser fit with the brand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Song, J.H.; Lee, J.-H. When are personalized promotions effective? The role of consumer control. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.-M.; Ju, S.-H. The interactional effects of atmospherics and perceptual curiosity on emotions and online shopping intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajnef, K. The effect of social media influencers' on teenagers Behavior: an empirical study using cognitive map technique. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19364–19377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, S.Y. “You are a virtual influencer!”: Understanding the impact of origin disclosure and emotional narratives on parasocial relationships and virtual influencer credibility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, D.B.; Nowlis, S.M. The Effect of Examining Actual Products or Product Descriptions on Consumer Preference. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmillan, S.J. A four-part model of cyber-interactivity: Some cyber-places are more interactive than others. New Media Soc. 2002, 4, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.T.; Krantz, D.S. Information, choice, and reactions to stress: A field experiment in a blood bank with laboratory analogue. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowska, A.; Arsenyan, J. Sweet escape: The role of empathy in social media engagement with human versus virtual influencers. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2023, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, E.; Lamba, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Ranganathan, C. Blurring lines between fiction and reality: Perspectives of experts on marketing effectiveness of virtual influencers. 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IrelandDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Oliveira, A.B.d.S.; Chimenti, P. "Humanized Robots": A Proposition of Categories to Understand Virtual Influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, R.; Mohr, P.N.C.; Kenning, P.H.; Davis, F.D.; Heekeren, H.R. Trusting Humans and Avatars: A Brain Imaging Study Based on Evolution Theory. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 30, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanak-Kosmowska, K.; Wiktor, J.W. Empirical Identification of Latent Classes in the Assessment of Information Asymmetry and Manipulation in Online Advertising. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, S.; Campbell, C.L.; Plangger, K.; Ferraro, C. Unreal influence: leveraging AI in influencer marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1721–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembada, A.Y.; Koay, K.Y. How perceived behavioral control affects trust to purchase in social media stores. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, R.; Harmon, R. Perceived Effectiveness of Push vs. Pull Mobile Location Based Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2007, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonkeman, C.; Verhagen, T.; van Dolen, W. Role of local presence in online impulse buying. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Whang, J.; Song, J.H.; Choi, B.; Lee, J.-H. The effect of Augmented Reality on purchase intention of beauty products: The roles of consumers’ control. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. , Lynch Jr, J. G., and Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of consumer research 37, 197–206.

- Zhou, X.; Yan, X.; Jiang, Y. Making Sense? The Sensory-Specific Nature of Virtual Influencer Effectiveness. J. Mark. 2023, 88, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).