Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

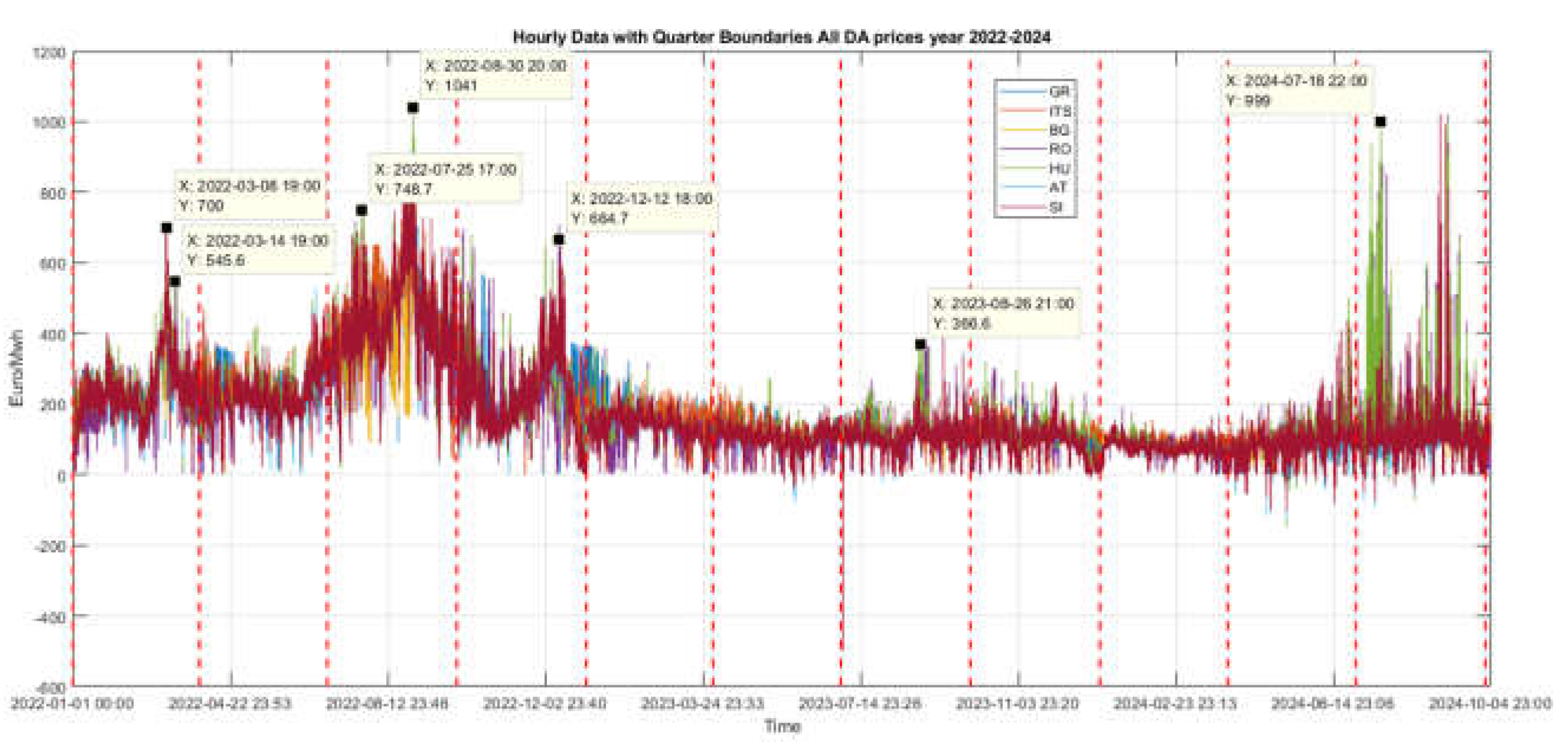

1.1. Price Disparity in Electricity Markets of Southeastern Europe (SEE) and Political Reactions

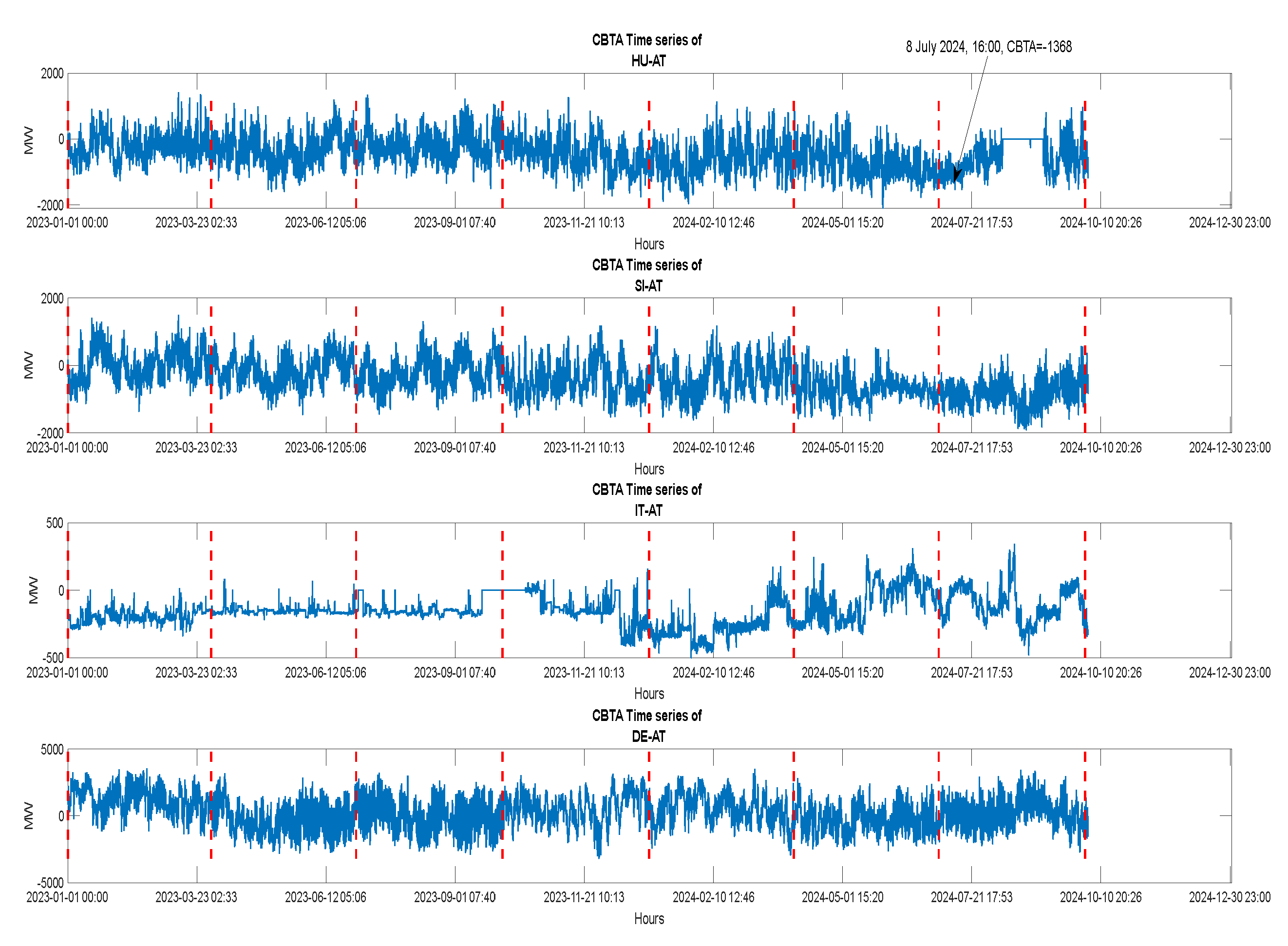

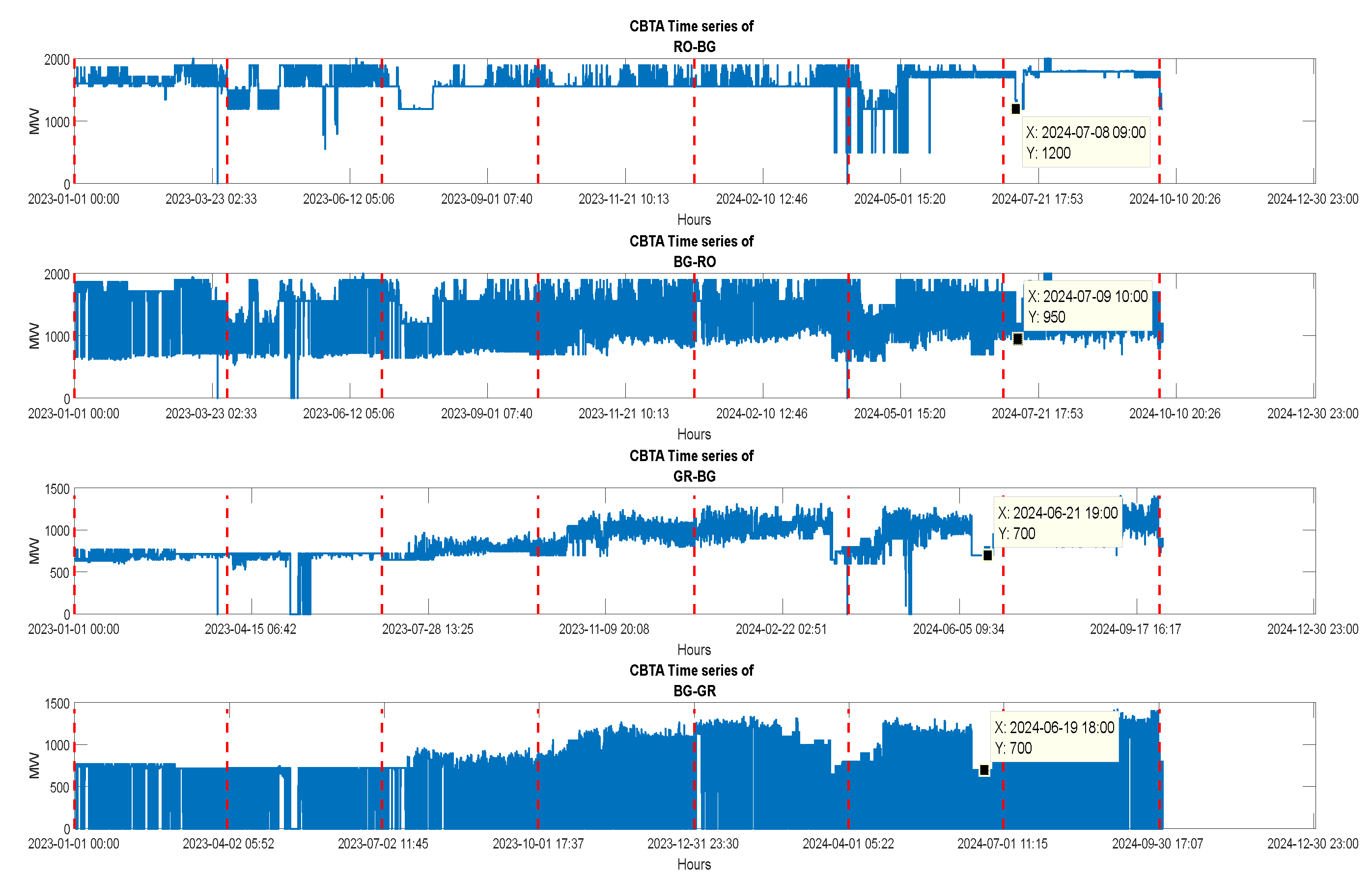

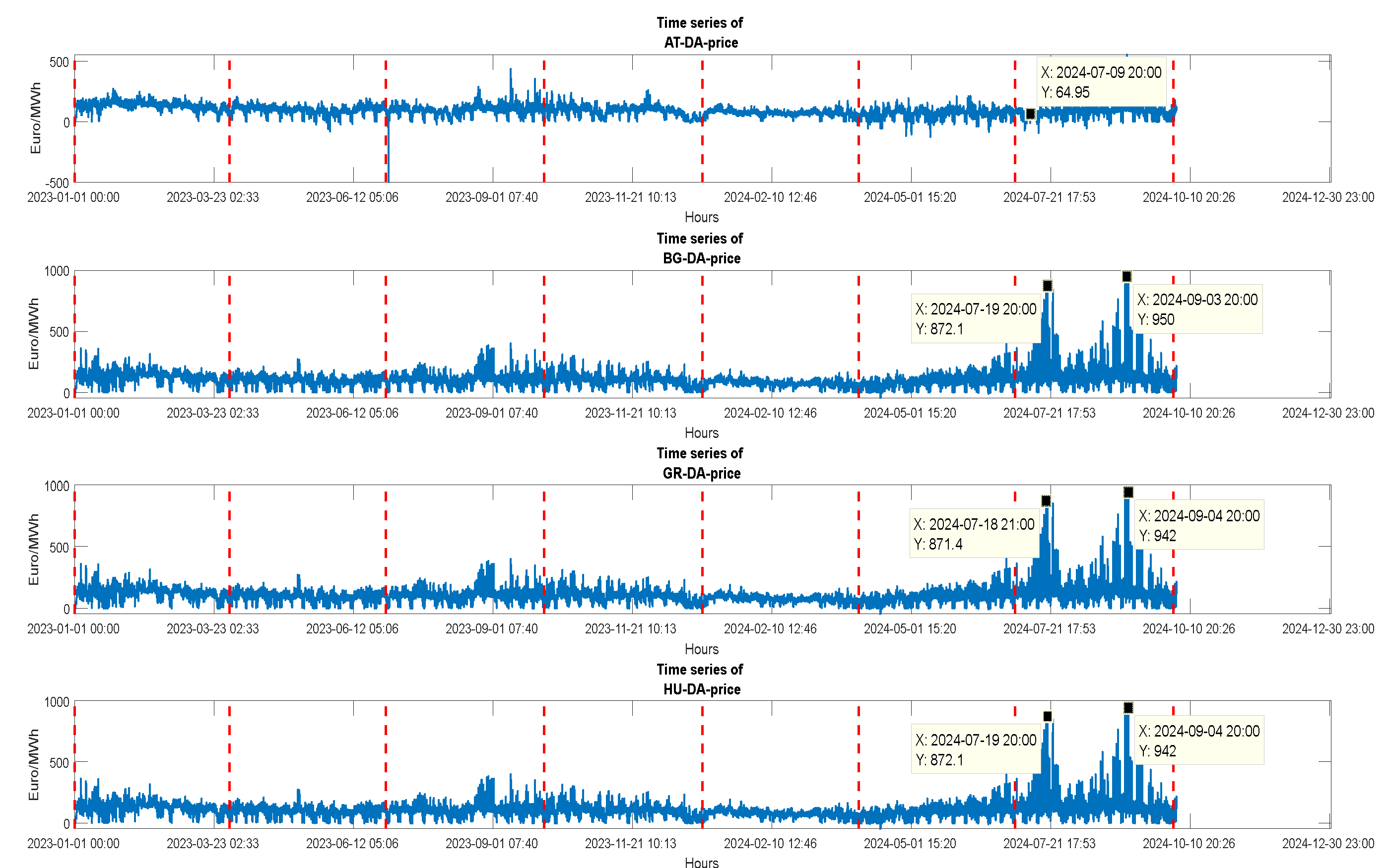

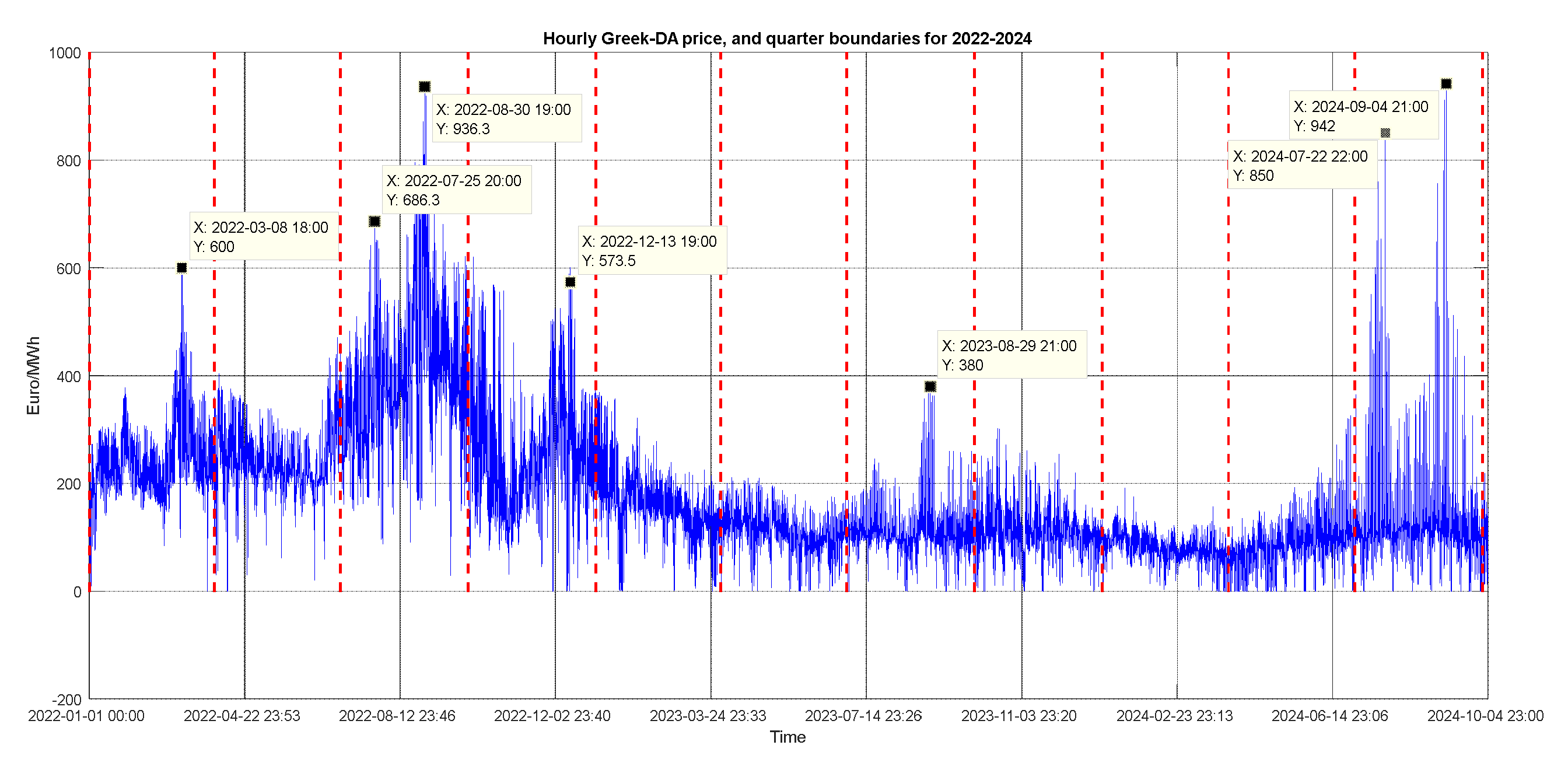

1.3. Characteristic Events in SEE CCR’s Markets, Core and Regional Structural Distortions

2. Literature Review on Markov Blanket-Based Causal Feature Selection

Application of Bayesian Analysis and Causality Structure Learning Approaches in Electricity Markets

3. Power Cross-Border Transfer Availability in Core and Southeast Europe Capacity Calculation Regions (CCRs) and Its Impact on the SEE Markets Spot in Prices

|

Capacity Calculation Region (CCR) |

Calculation approach |

Day Ahead | |

| Regulation* | Implementation Status | ||

| Core: AT, HU, SI, RO | FB Coupling | Capacity Allocation and Congestion Management (CACM) |

Mostly |

| GRIT: GR, IT | Coordinated net Transfer capacity CNTC |

Capacity Allocation and Congestion Management (CACM) |

Mostly |

| SEE: BG, GR | Coordinated net Transfer capacity CNTC |

Capacity Allocation and Congestion Management (CACM) |

Mostly |

| *Note: Article 34 of regulation (EU), 2015/1222 | |||

| Capacity Calculation. Region (CCR) |

As % of peak demand (2024) |

As % of peak Generation (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Core: AT, HU, SI, RO | 75, 102, 224, 47 | 53, 129, 273, 34 |

| GRIT: GR, IT | 11, 13 | 11, 4 |

| SEE: BG, GR | 32, 11 | 29, 11 |

Limited Cross-Border Capacity and Market Fragmentation

4. Data Sets, Preprocessing, Summary (Descriptive) Statistics, Correlation Analysis and Cross-Border Transfer Availability

| Node (Variable) | Name | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AT_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Austria | Euro/MWh |

| 2 | AT_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Austria | MW |

| 3 | AT_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Austria | MW |

| 4 | AT_actGas | Gas power production, Austria | MW |

| 5 | AT_Solar_Fct | Solar forecst. Power product. , Austria | MW |

| 6 | AT_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power Forecasted, Austria | MW |

| 7 | BG_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Bulgaria | Euro/MWh |

| 8 | BG_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Bulgaria | MW |

| 9 | BG_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Bulgaria | MW |

| 10 | BG_actGas | Gas power production, Bulgaria | MW |

| 11 | BG_Wind_Fct | Wind forecast generated power, Bulgaria | MW |

| 12 | BG_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power product., Bulgaria | MW |

| 13 | BG_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Bulgaria | MW |

| 14 | BG_actual_Lignite | Lignite act power production, Bulgaria | MW |

| 15 | GR_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Greece | Euro/MWh |

| 16 | GR_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Greece | MW |

| 17 | GR_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Greece | MW |

| 18 | GR_actGas | Gas power production, Greece | MW |

| 19 | GR_Wind_Fct | Wind forecast generated power, Greece | MW |

| 20 | GR_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power product., Greece | MW |

| 21 | GR_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Greece | MW |

| 22 | GR_Hydro_Storage_Actual | Hydro Power act consumption, Greece | MW |

| 23 | GR_actual_Lignite | Lignite act power production, Greece | MW |

| 24 | HU_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Hungary | Euro/MWh |

| 25 | HU_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Hungary | MW |

| 26 | HU_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Hungary | MW |

| 27 | HU_actGas | Gas act.power production, Hungary | MW |

| 28 | HU_Wind_Fct | Wind forecast generated power, Hungary | MW |

| 29 | HU_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power product., Hungary | MW |

| 30 | HU_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Hungary | MW |

| 31 | HU_actual_Lignite | Lignite act power production, Hungary | MW |

| 32 | ITS_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Italy (South) | Euro/MWh |

| 33 | IT_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Italy | MW |

| 34 | IT_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Italy | MW |

| 35 | IT_actGas | Gas power production, Italy | MW |

| 36 | IT_Wind_Fct | Wind forecast generated power, Italia | MW |

| 37 | IT_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power production., Italia | MW |

| 38 | IT_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Italia | MW |

| 39 | RO_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Romania | Euro/MWh |

| 40 | RO_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Romania | MW |

| 41 | RO_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Romania | MW |

| 42 | RO_actGas | Gas power production, Romania | MW |

| 43 | RO_Wind_Fct | Wind forecast generated power, Romania | MW |

| 44 | RO_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power product., Romania | MW |

| 45 | RO_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Romania | MW |

| 46 | RO_actual_Lignite | Lignite act. power production, Romania | MW |

| 47 | SI_DA_price | DA Electricity price, Slovenia | Euro/MWh |

| 48 | SI_actTotal_Load | Actual Total Load, Slovenia | MW |

| 49 | SI_foreTotal_Load | Forecasted Total Load, Slovenia | MW |

| 50 | SI_actGas | Gas power production, Slovenia | MW |

| 51 | SI_Solar_Fct | Solar forecast. Power product., Slovenia | MW |

| 52 | SI_Hydro_Actual | Hydro Power production, actual, Slovenia | MW |

| 53 | SI_actual_Lignite | Lignite act power production, Slovenia | MW |

| 54 | GR_BG | Cross Border Transfer, GR-BG | MW |

| 55 | BG_GR | Cross Border Transfer, BG-GR | MW |

| 56 | IT_GR | Cross Border Transfer, IT-GR | MW |

| 57 | GR_IT | Cross Border Transfer, GR-IT | MW |

| 58 | RO_BG | Cross Border Transfer, RO-BG | MW |

| 59 | BG_RO | Cross Border Transfer, BG-RO | MW |

| 60 | SI_IT | Cross Border Transfer, SI-IT | MW |

| 61 | IT_SI | Cross Border Transfer, IT-SI | MW |

| 62 | AT-CH | Cross Border Transfer, AT-CH | MW |

| 63 | AT-CZ | Cross Border Transfer, AT-CZ | MW |

| 64 | AT-DELU | Cross Border Transfer, AT-DELU (Austria to Germany-Luxembourg) | MW |

| 65 | AT-ITNorth | Cross Border Transfer, AT-ITNorth | MW |

| 66 | AT-SI | Cross Border Transfer, AT-SI | MW |

| 67 | AT-HU | Cross Border Transfer, AT-HU | MW |

| 2022-Oct.2024 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | HU | RO | BG | GR | ITSouth | SI | AT |

| min | -500.0 | -106.30 | -45.00 | -1.02 | 0.00 | -500.00 | -500.00 |

| max | 1047.10 | 1021.60 | 950.00 | 942.00 | 870.00 | 1023.00 | 919.60 |

| mean | 161.89 | 159.40 | 154.75 | 170.61 | 180.85 | 159.71 | 151.06 |

| median | 120.96 | 119.74 | 119.28 | 130.63 | 134.06 | 117.90 | 111.30 |

| mode | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Std | 128.53 | 128.13 | 119.10 | 117.57 | 120.71 | 126.31 | 122.89 |

| prctile25 | 84.18 | 83.13 | 83.09 | 92.77 | 104.08 | 82.86 | 78.46 |

| prctile75 | 204.15 | 200.63 | 197.51 | 223.07 | 220.00 | 203.50 | 189.10 |

| iqr | 119.97 | 117.50 | 114.42 | 130.30 | 115.92 | 120.64 | 110.64 |

| 2022 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | HU | RO | BG | GR | ITSouth | SI | AT |

| min | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| max | 1047.10 | 964.20 | 936.30 | 936.30 | 870.00 | 879.30 | 919.60 |

| mean | 271.62 | 265.26 | 253.20 | 279.86 | 295.77 | 274.43 | 261.36 |

| median | 237.20 | 232.58 | 225.08 | 249.28 | 257.23 | 240.01 | 224.00 |

| mode | 138.41 | 138.41 | 138.41 | 200.00 | 650.00 | 220.00 | 190.00 |

| Std | 139.88 | 142.95 | 131.20 | 116.10 | 131.03 | 137.00 | 138.47 |

| prctile25 | 178.25 | 165.31 | 163.27 | 206.89 | 206.43 | 185.03 | 169.09 |

| prctile75 | 345.26 | 342.15 | 320.14 | 339.31 | 370.00 | 343.24 | 336.98 |

| iqr | 167.00 | 176.84 | 156.86 | 132.42 | 163.56 | 164.20 | 167.88 |

| 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | HU | RO | BG | GR | ITSouth | SI | AT |

| min | -500.0 | -23.18 | -1.10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -500.0 | -500.0 |

| max | 437.47 |

436.89 | 400.00 | 383.82 | 298.20 | 426.18 | 437.47 |

| mean | 106.79 | 103.71 | 103.82 | 119.09 | 125.03 | 104.30 | 102.11 |

| median | 104.48 |

102.72 | 102.74 | 112.47 | 120.94 | 103.38 | 101.91 |

| mode | 0.0 | 122 | 122 | 100 | 100 | 120 | 0.0 |

| Std | 48.43 | 50.78 | 50.33 | 50.18 | 37.69 | 45.33 | 44.40 |

| prctile25 | 83.75 | 79.26 | 79.20 | 93.00 | 103.47 | 83.21 | 82.09 |

| prctile75 | 133.56 | 132.56 | 132.54 | 141.33 | 145.30 | 130.95 | 128.84 |

| iqr | 49.81 | 53.30 | 53.34 | 48.33 |

41.83 | 47.74 | 46.75 |

| 2024 (up to 4th October) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | HU | RO | BG | GR | ITSouth | SI | AT |

| min | -149.98 | -106.36 | -45.00 | -1.02 | 0.0 | -105.88 | -426.42 |

| max | 999.0 | 1021.6 | 950.00 | 942.0 | 252.1 | 1022.3 | 555.7 |

| mean | 90.15 | 93.53 | 92.37 | 94.79 | 103.24 | 81.85 | 70.48 |

| median | 81.85 | 85.00 | 85.00 | 88.67 | 102.84 | 79.72 | 74.21 |

| mode | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.04 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Std | 78.91 | 78.66 | 74.06 | 64.93 | 31.22 | 56.02 | 37.19 |

| prctile25 | 60.49 | 61.65 | 61.42 | 69.53 | 88.84 | 58.90 | 55.13 |

| prctile75 | 104.98 | 108.01 | 107.49 | 108.11 | 115.59 | 101.82 | 91.20 |

| iqr | 44.49 | 46.35 | 46.06 | 38.58 | 26.75 | 42.91 | 36.07 |

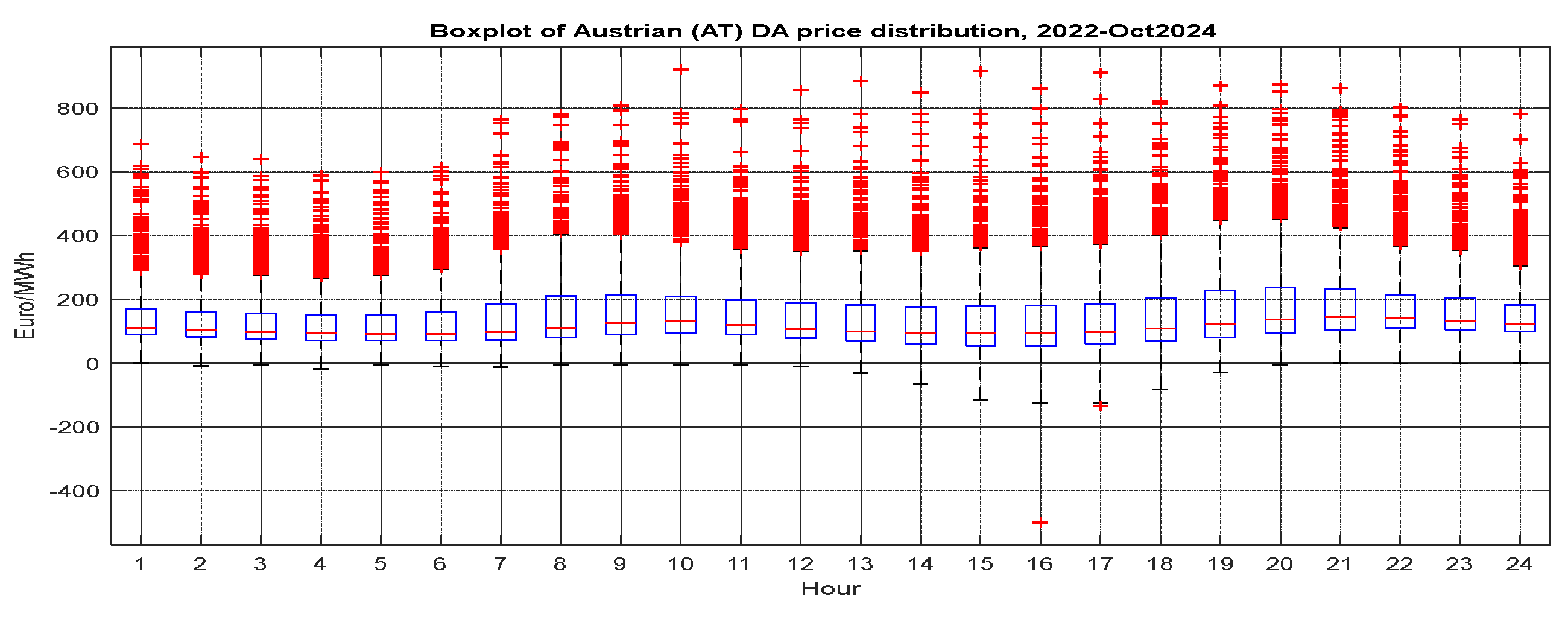

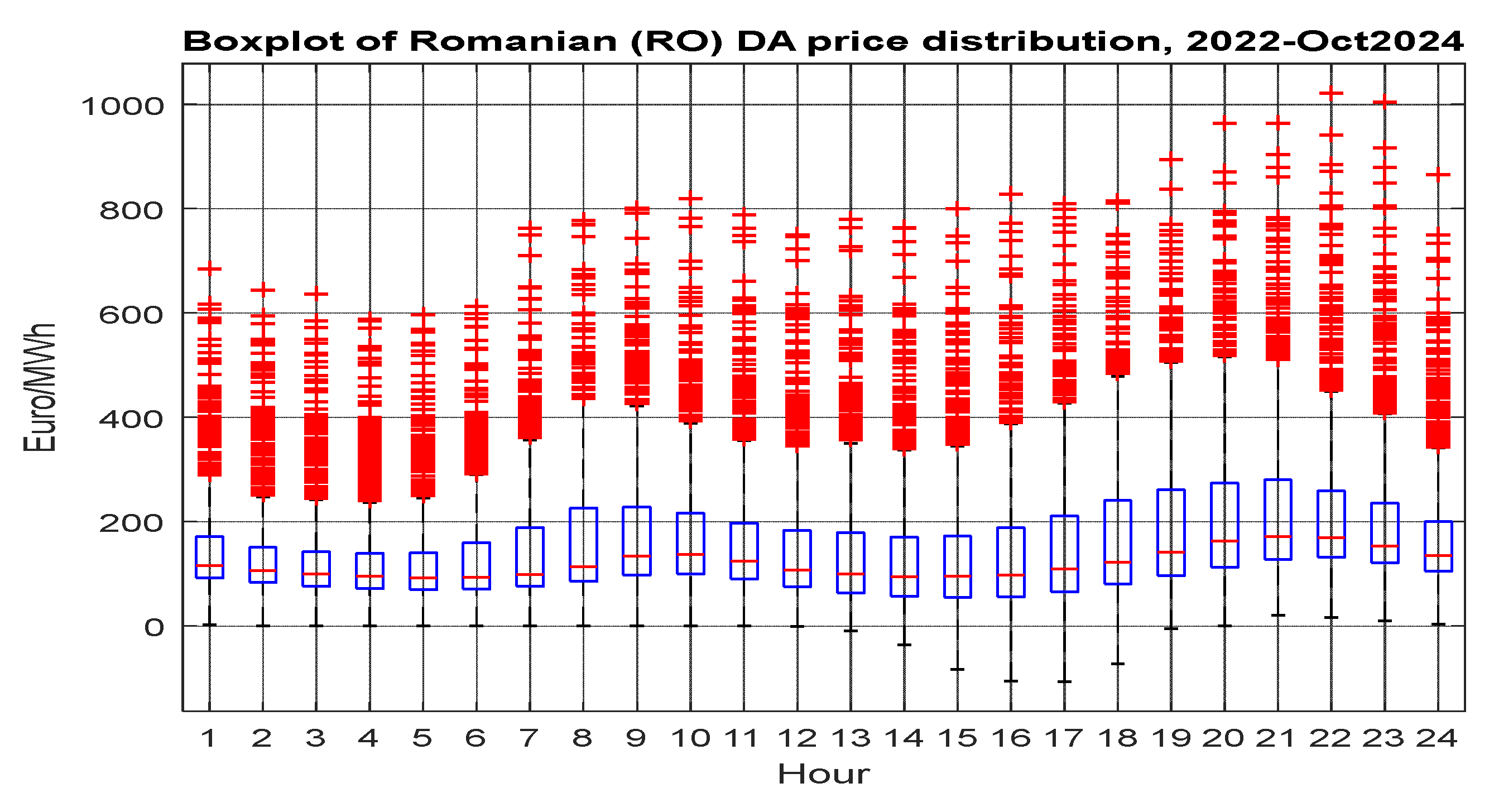

4.1. Boxplots, Aggregated and Hourly-Wised Summary Statistics of Spot Prices

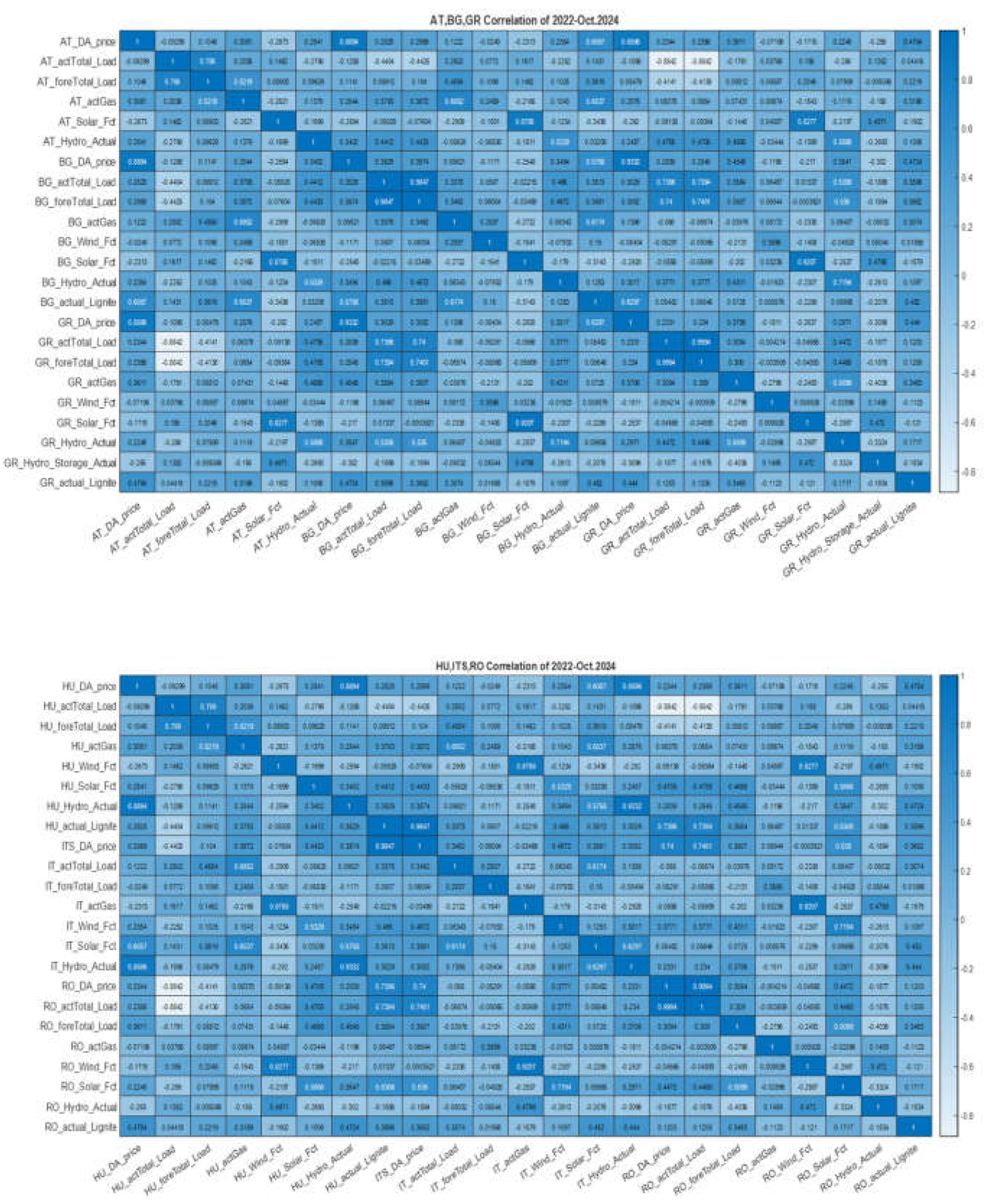

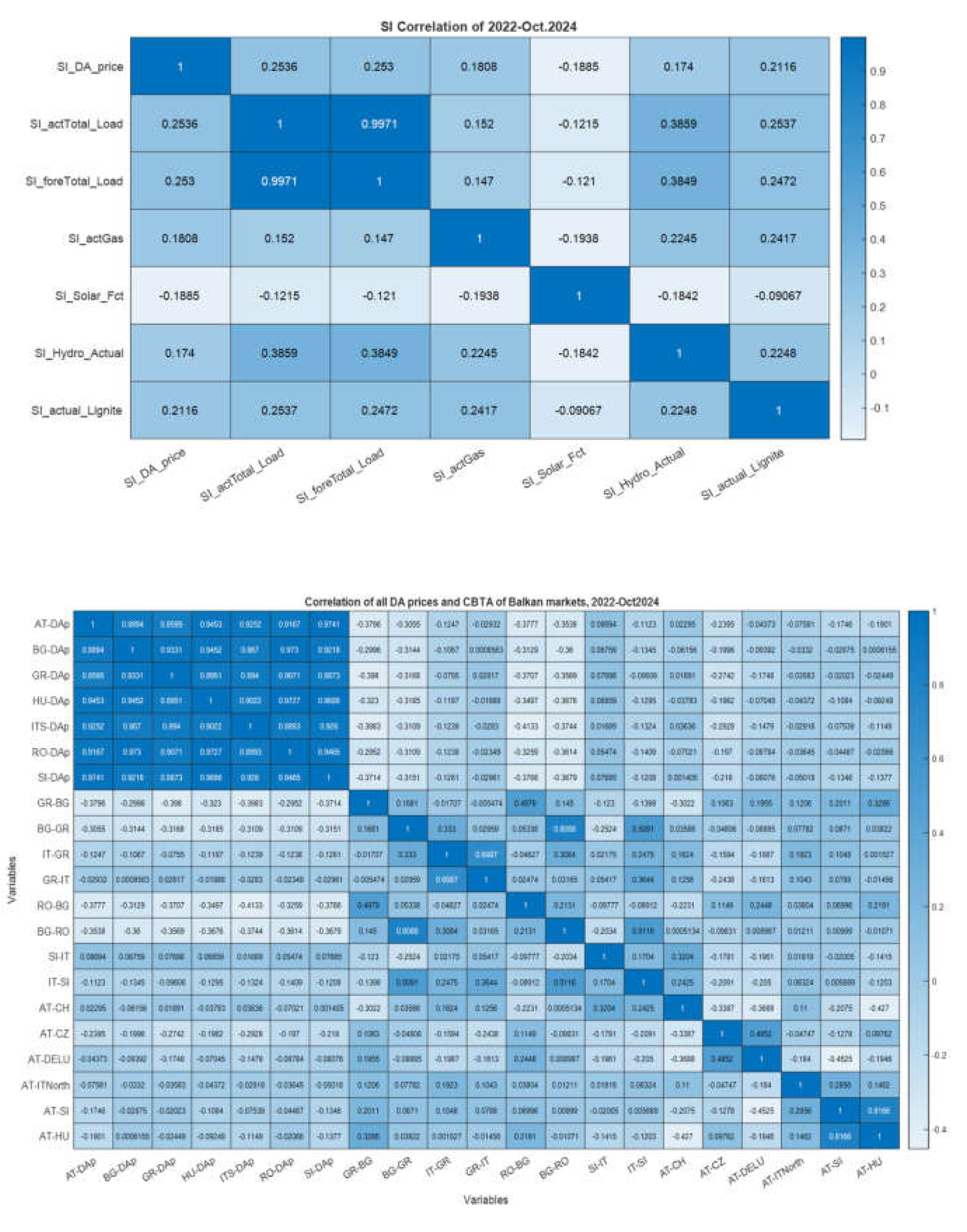

4.2. Correlation Analysis of All Raw DATA, 2022-Oct2024.

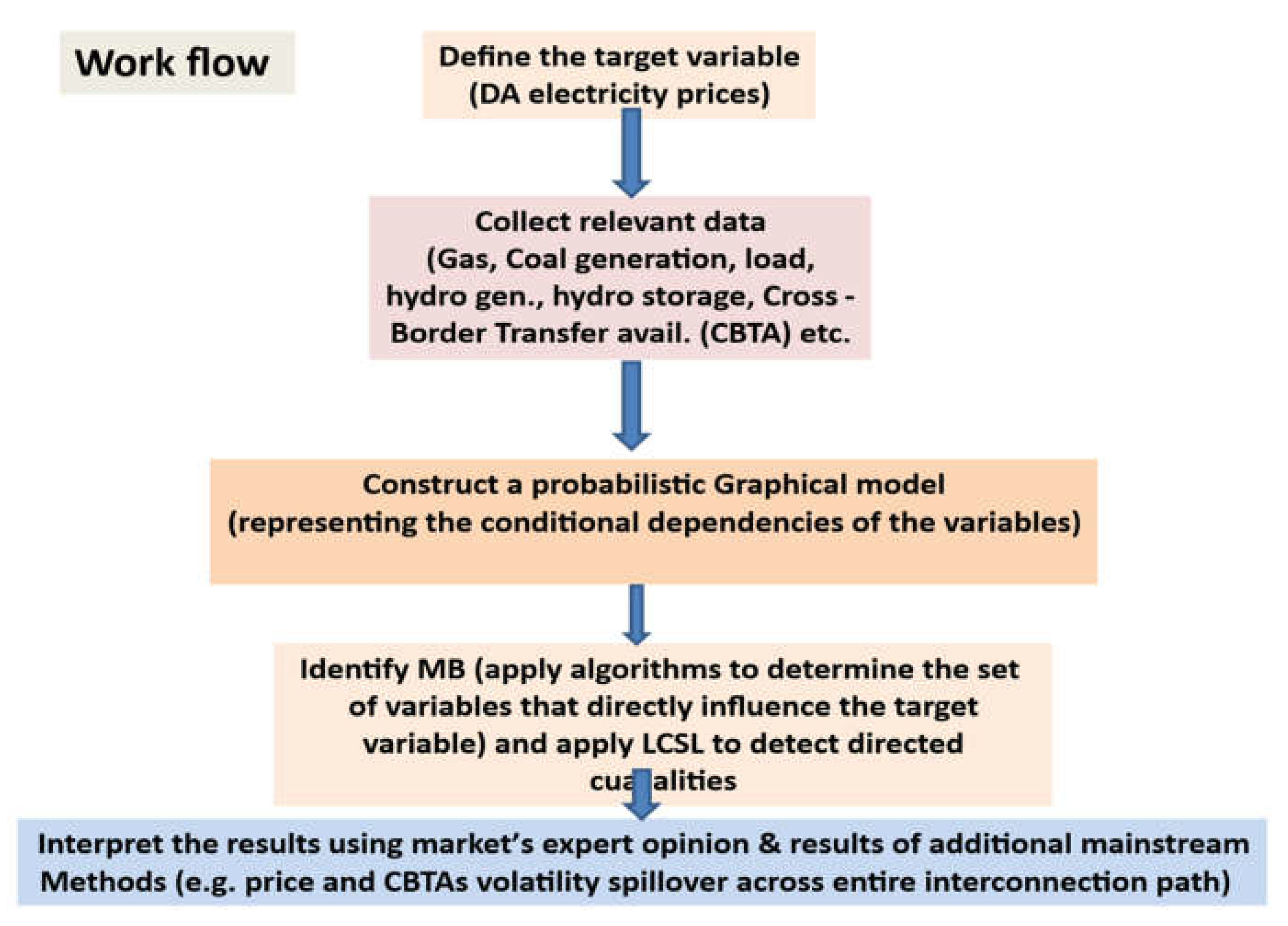

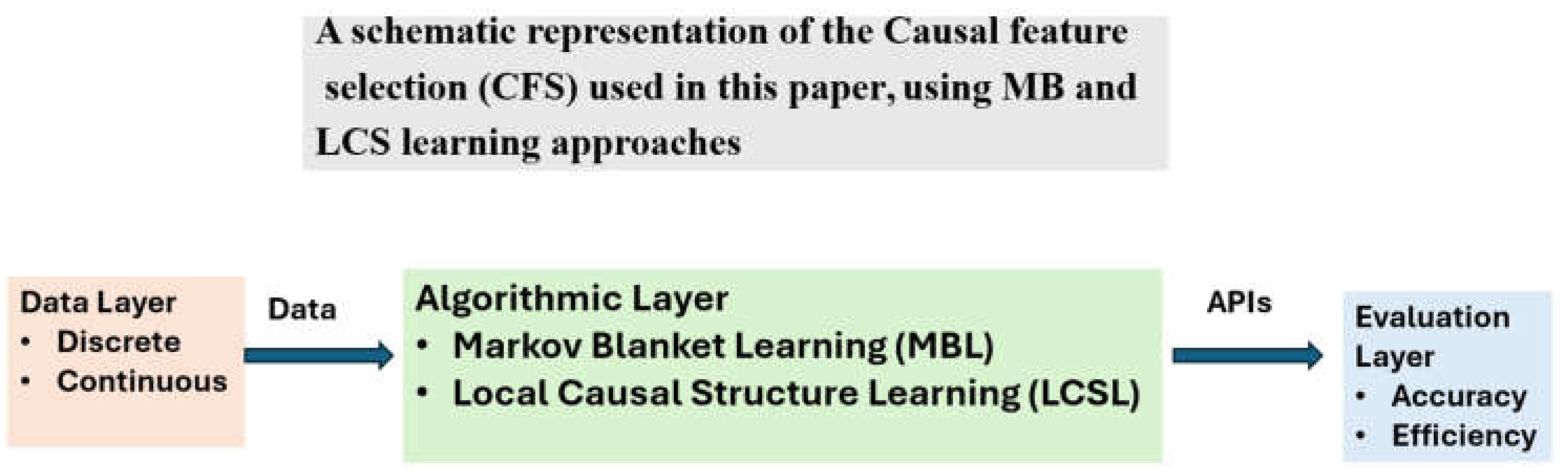

5. Methodology

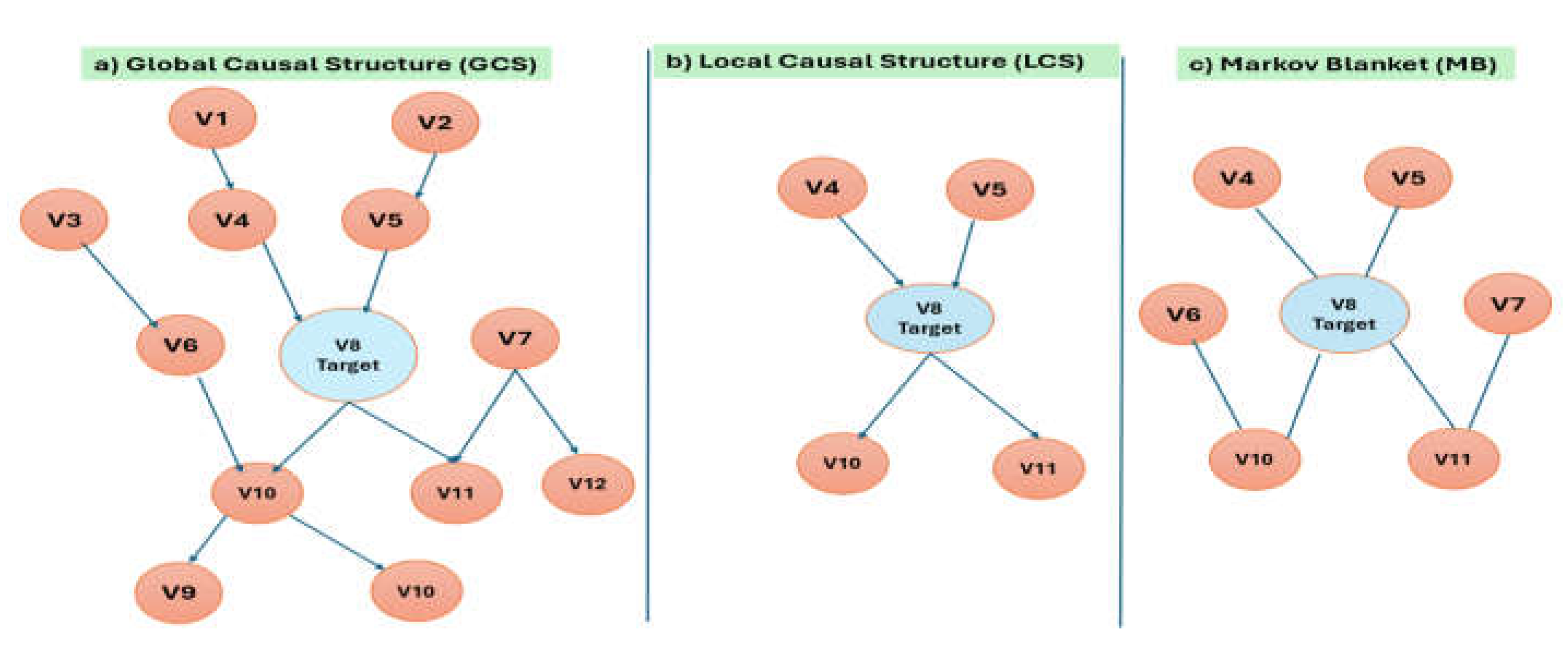

5.1. The Difference Between Global, Local Causal Structure Learning, and Markov Blanket Learning

5.2. A Short Mathematical Background in Bayesian network (BN), Markov blanket (MB) and Causal Feature Selection (CFS)

5.3. Bayesian Network, Markov Blanket, and Causal Feature Selection

5.4. The Objective Function of Optimal Feature Selection Problem, Based on the MI Concept

5.5. The Markov Blanket (MB), a Tool for Causal Feature Selection to Reveal the Strongest Factors Influencing DA Electricity Prices

5.6. Practical Aspects in Applying the MB CFS Approach to Understand Price Surges in SEE Electricity Markets and a Suggested Workflow.

- Define the Target Variable: in our case, electricity price surges in all seven markets.

- Collect Relevant Data: Gather data on potentially influencing factors, such as fuel prices, demand and supply metrics, policy changes, and geopolitical events.

- Construct a Probabilistic Graphical Model: Use the collected data to build a model that represents the conditional dependencies between variables.

- Identify the Markov Blanket MB: Apply algorithms to determine the set of variables that directly influence the target variable.

- Use LCSL methodology to identify the direct causalities between the member-variables of the MB

- Interpret the Results: Analyze the identified factors to understand their causal impact on electricity price surges, using results from volatility spillovers, and opinions form the market experts.

5.7. Justification of Using Causal Discovery and Feature Selection Approach Instead of a Typical Regression Model.

| Aspect | Markov Blanket | Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Causal relationships | Statistical associations |

| Feature Selection | Identifies causally relevant variables | May include spurious or redundant variables |

| Handling Multicollinearity | Resolves through conditional independence | Struggles without feature engineering |

| Model Complexity | Produces a minimal set of explanatory variables | Includes all statistically significant variables |

| Interpretability | Provides clear causal explanations | Explains variance but not causality |

| Assumptions | Requires conditional independence assumption | Assumes linearity (in linear regression) |

| Performance in High Dimensions | Effective for sparse causal structures | May be overfit without regularization |

5.8. Algorithms Associated with Causal Discovery and Feature Selection (CFS) and MB

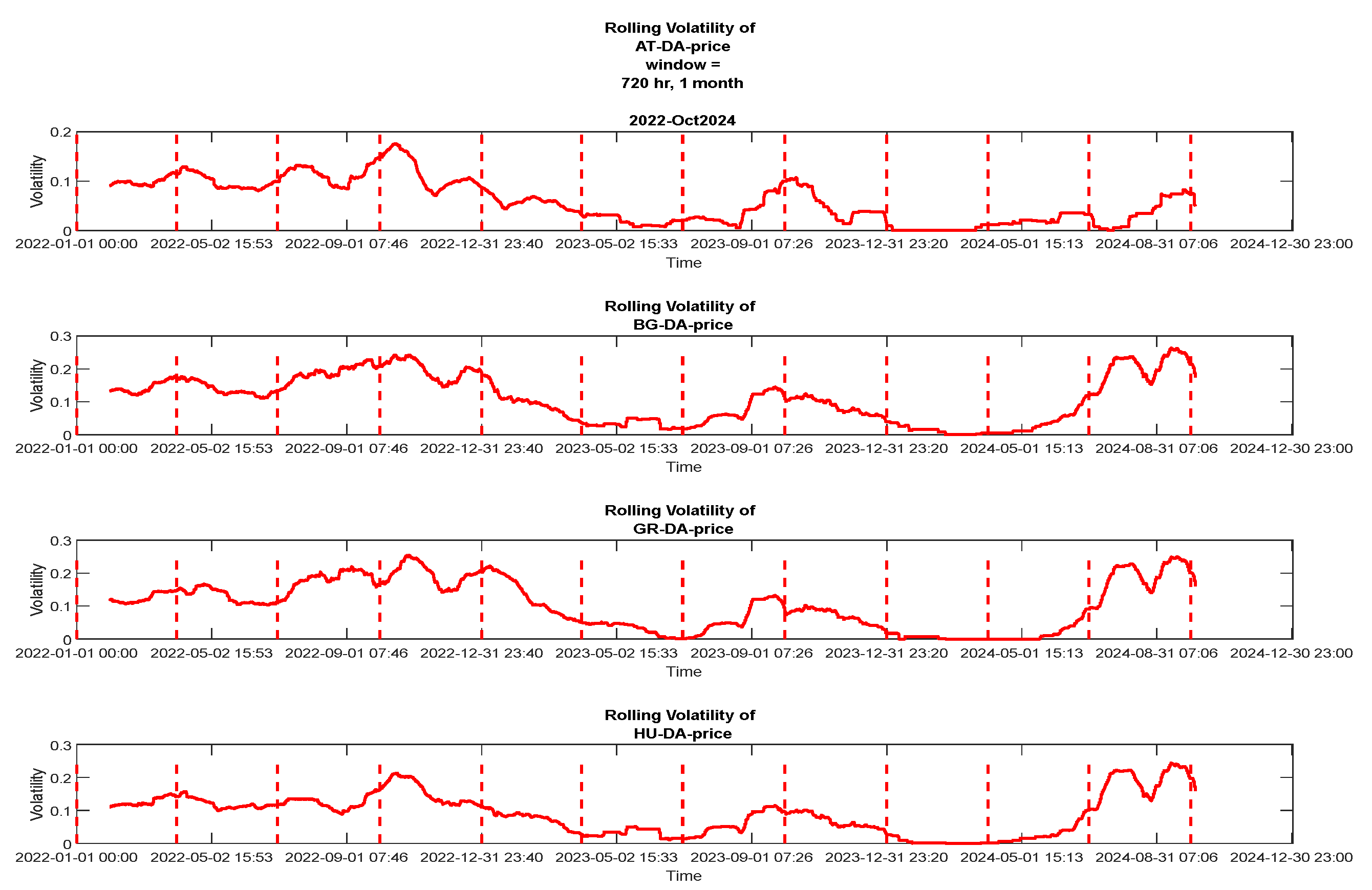

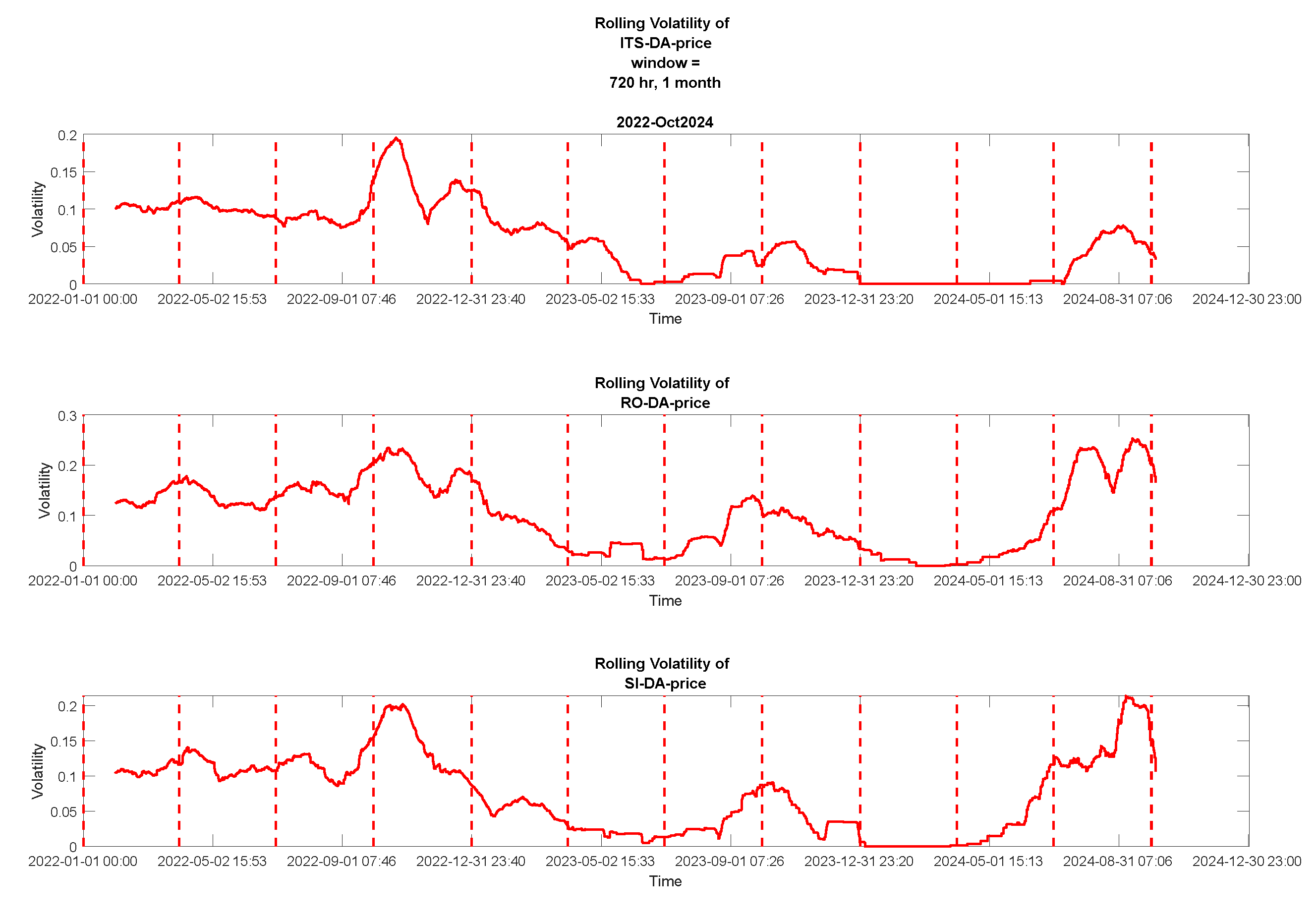

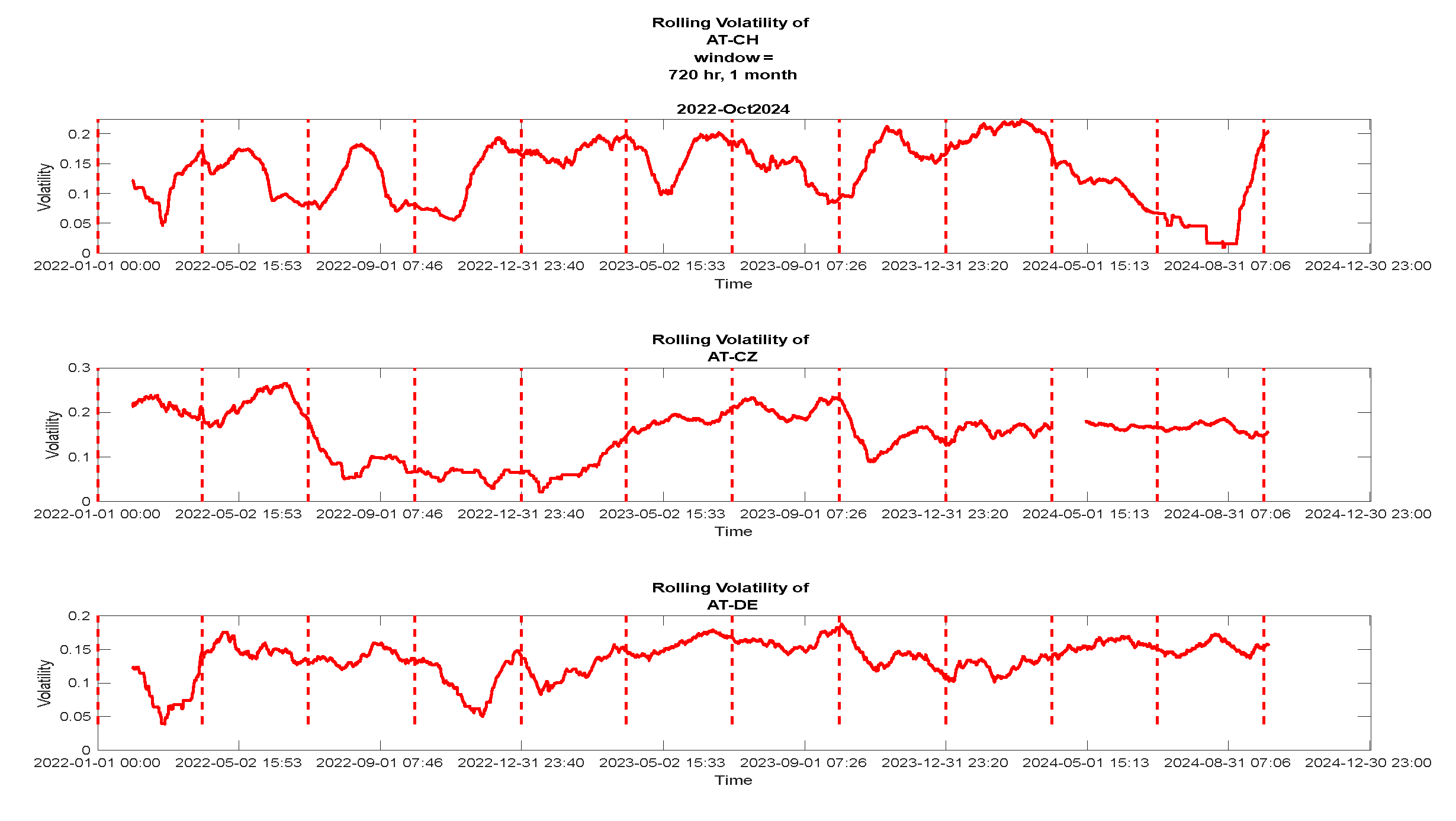

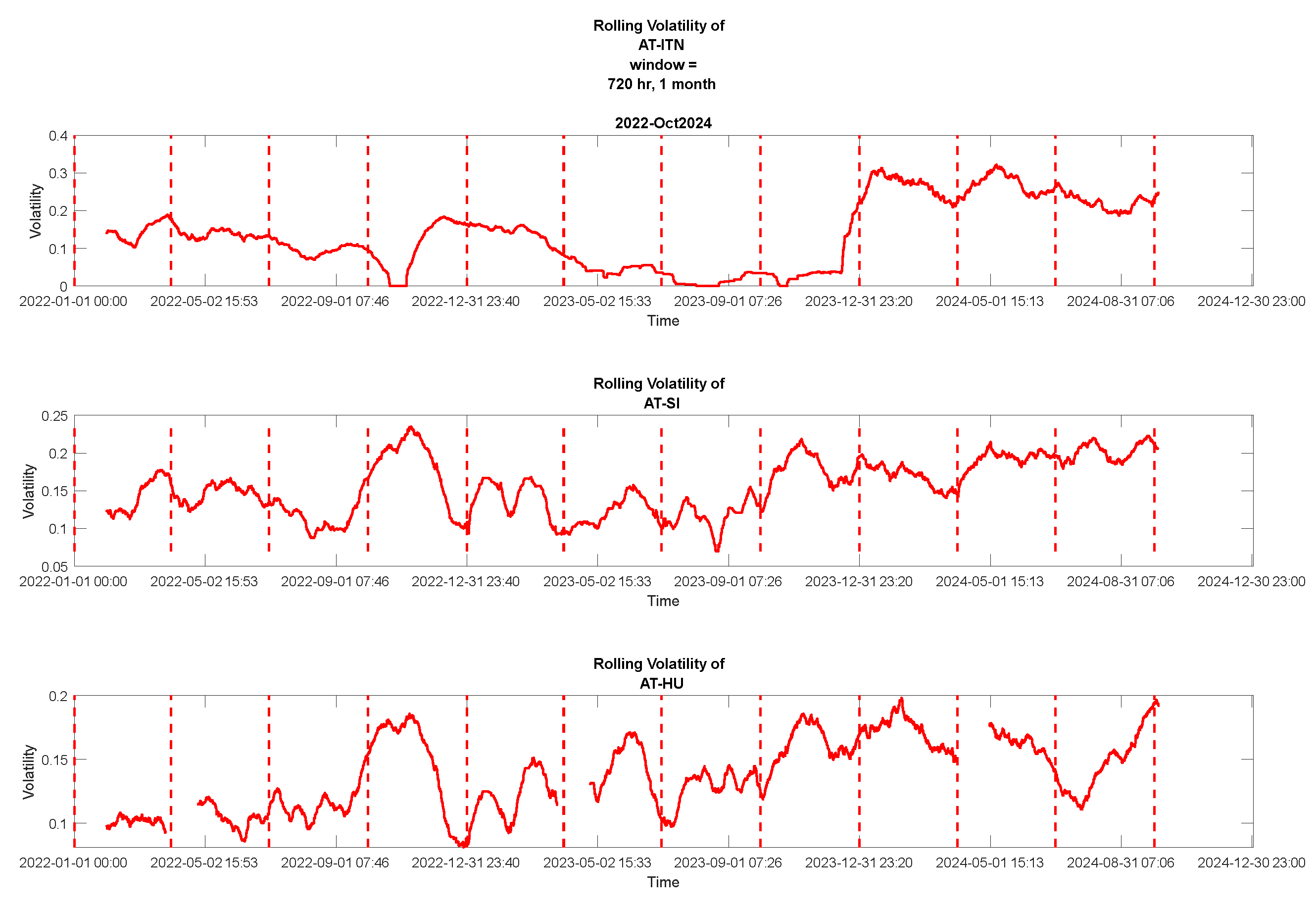

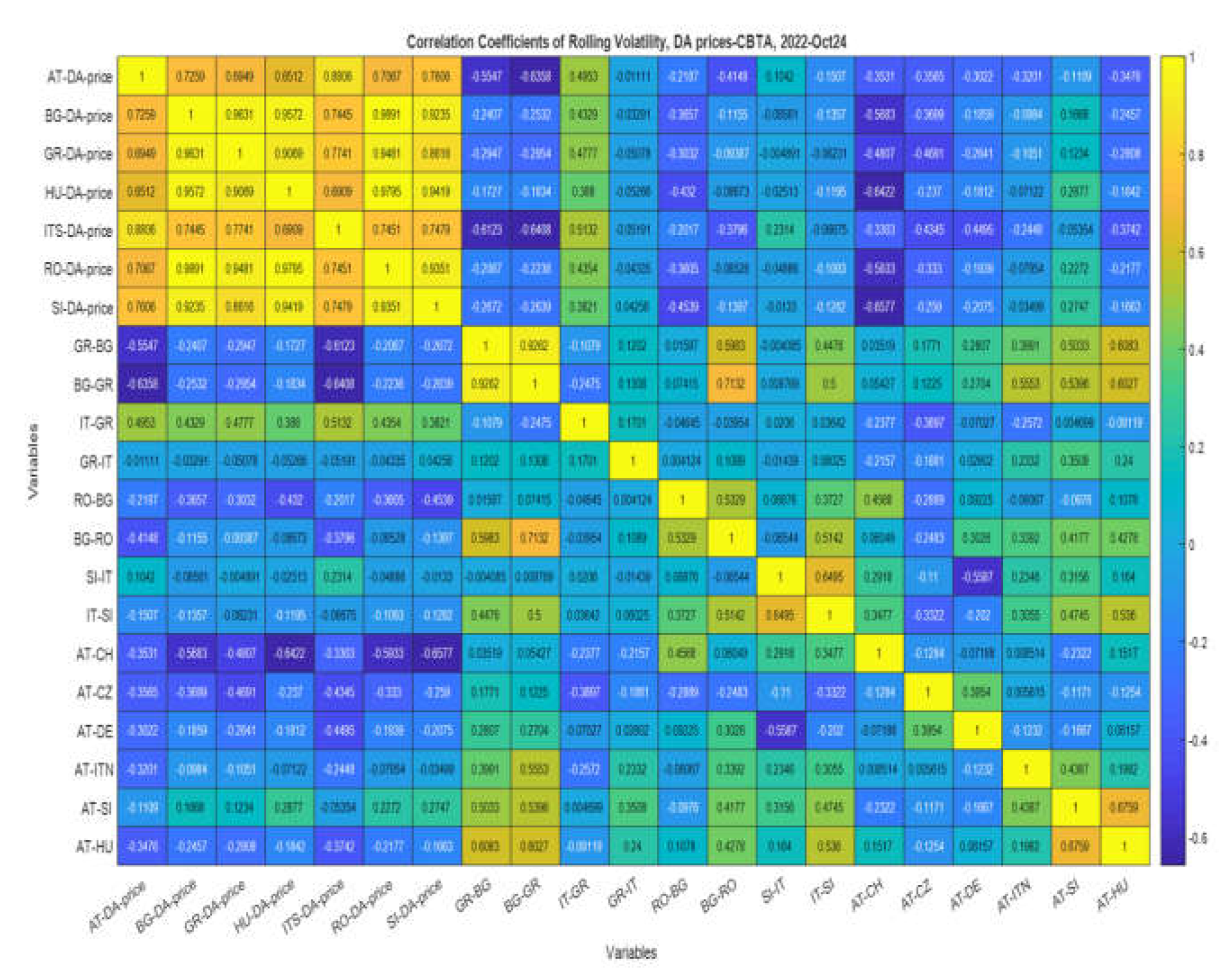

6. Rolling Volatility of DA prices and Their Correlation to ‘Grasp’ Spillover Effects

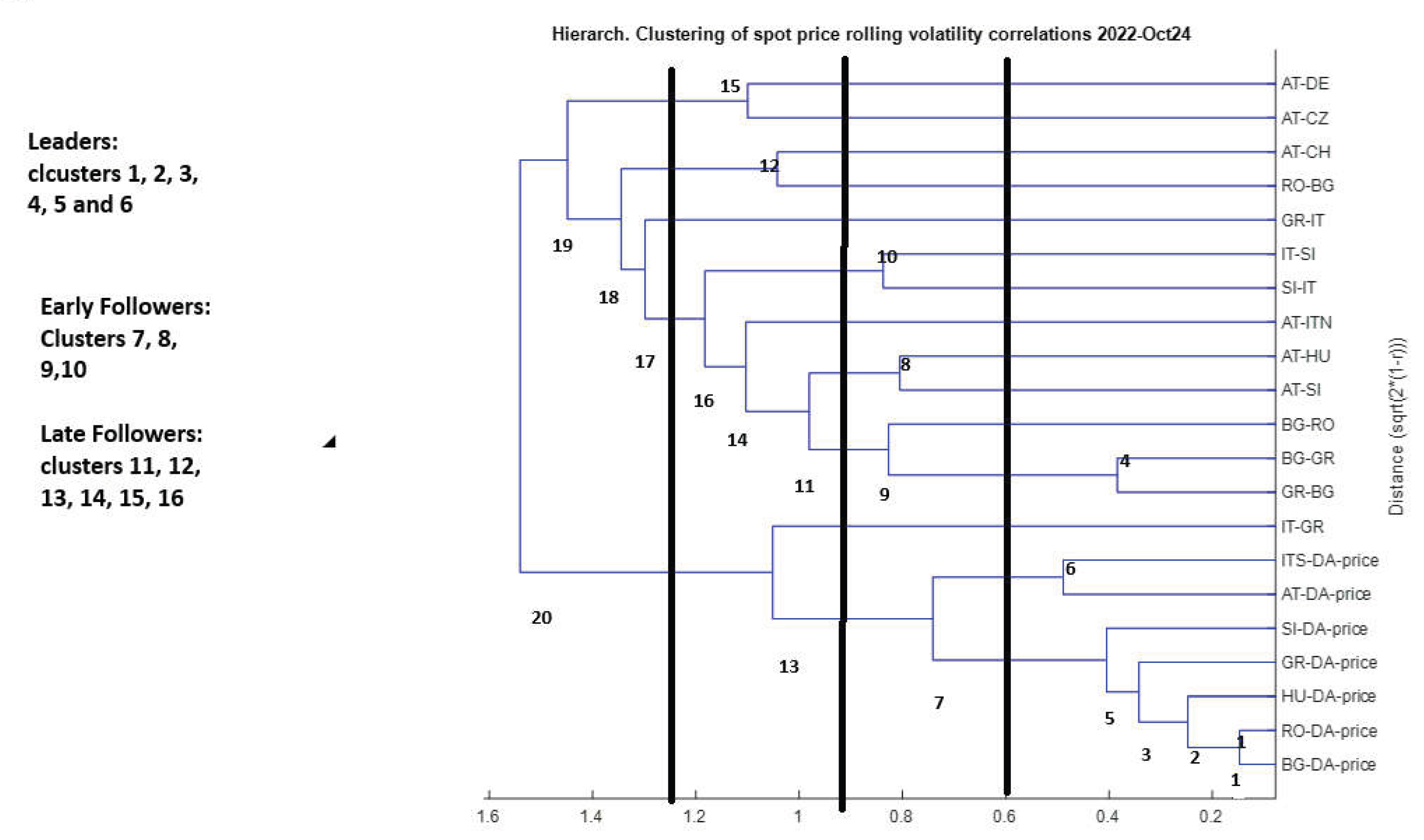

The Clustering Tool Dendrogram, in Our Context

7. Empirical Results

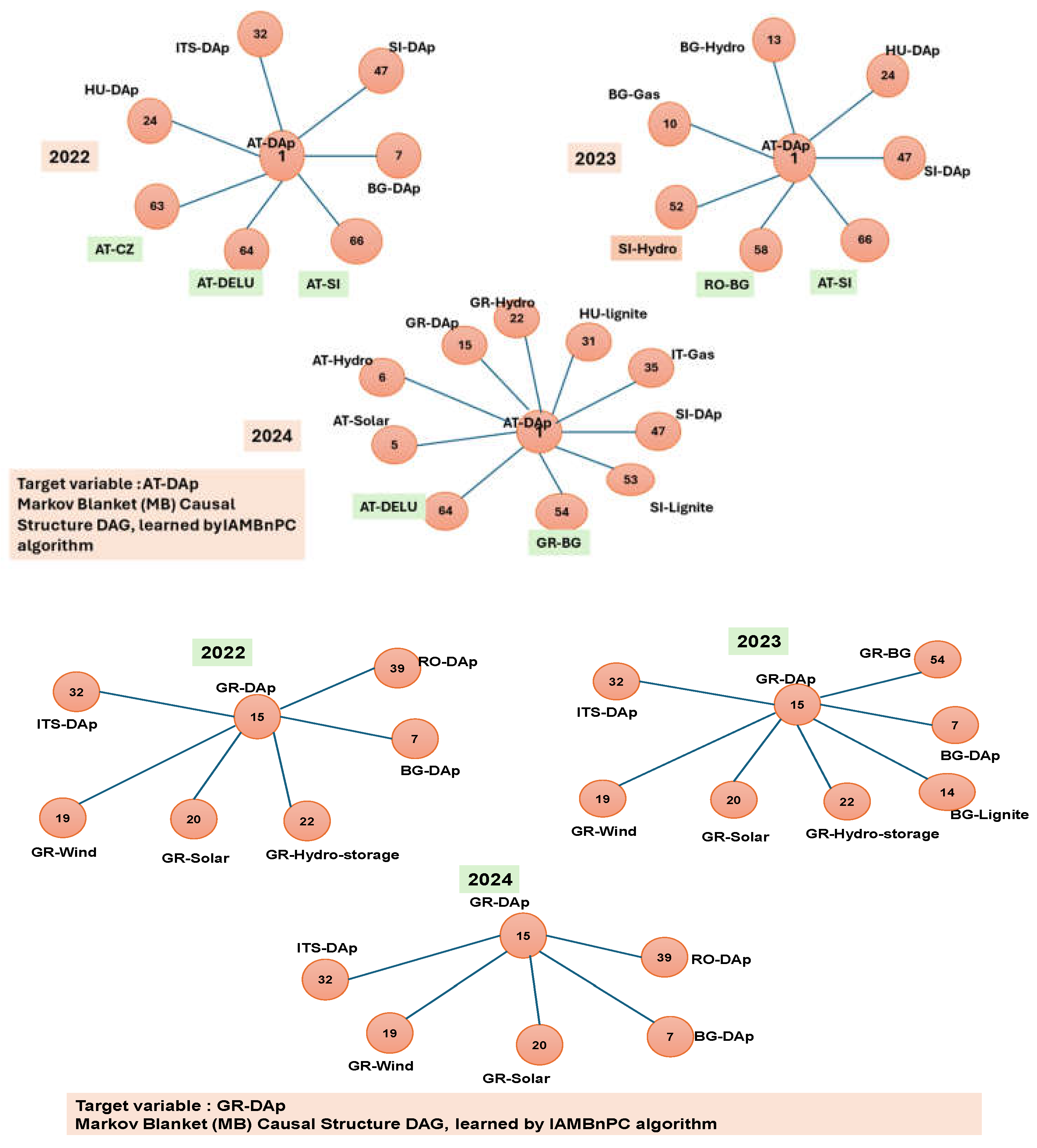

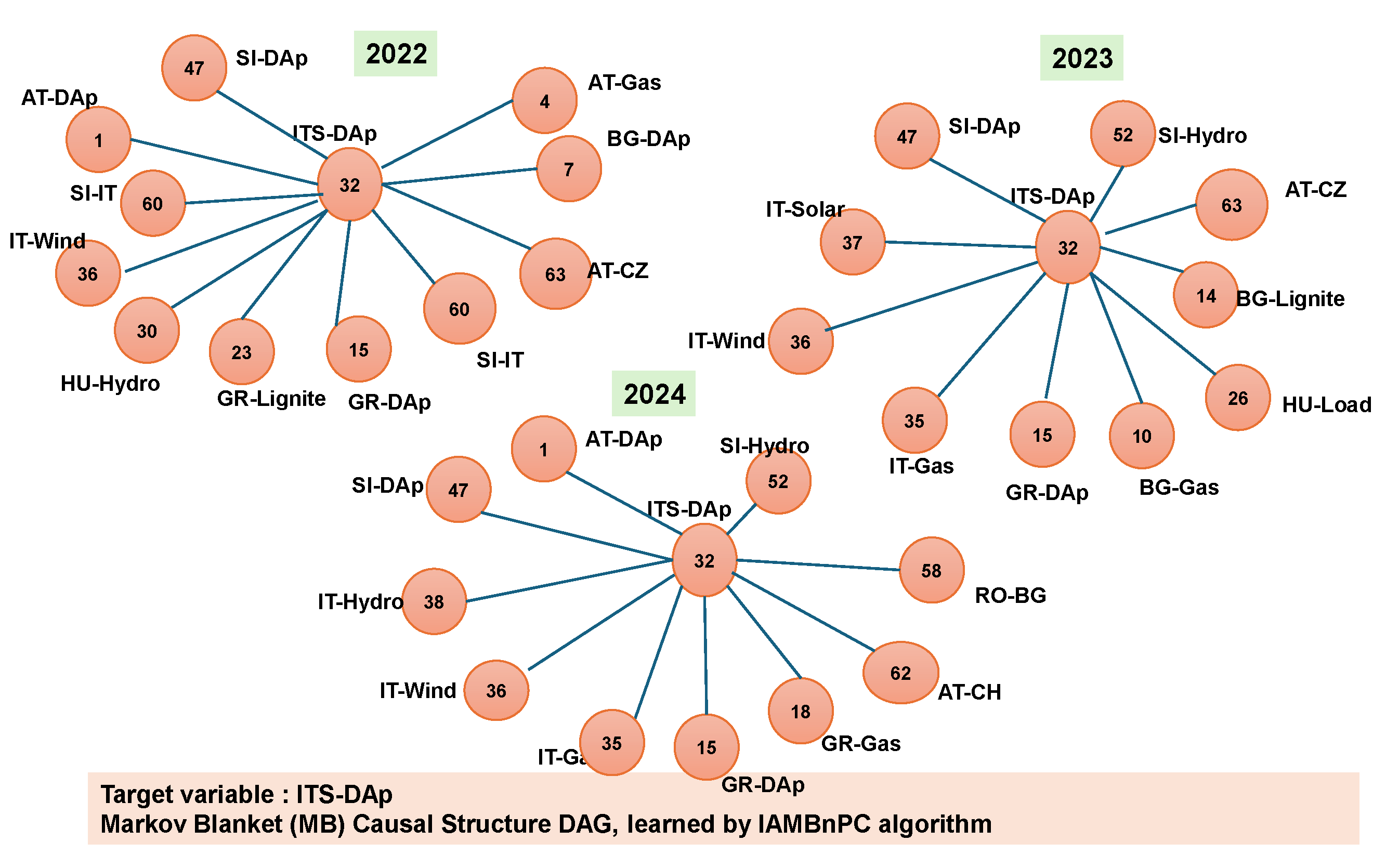

7.1. Markov Blanket Learning

7.1.1. MB analysis of DA Prices as Target Variable

| Causal structure learning by Markov Blanket (MB) (IAMBnPC algorithm) | ||||

| Target Variable: AT-DA-p (1*) | ||||

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2022-2024 |

| Nodes (Comp. of MB) | 24,32,47,63,64,66 | 10,13,24,47,52,58,66 | 5,6,15,22,31,35,45,47,53,54,64 | 4,32,47,50,66 |

| Target Variable: BG-DA-p (7) | ||||

| Nodes (Comp. of MB) | 15,19,21,39,42,46 | 15,28,31,39,53,66 | 15,39,47,50,62 | 15,19,21,35,39,64 |

| Target Variable: GR-DA-p (15) | ||||

| Nodes (Comp. of MB) | 7, 19, 20,22,32,39 | 7,14,19,20,22,32,54 | 7,19,20,32,39 | 1,7,14,19,20,32 |

| Target Variable: HU-DA-p (24) | ||||

| Nodes(Comp. Of MB) |

1,35,39,43,47 | 1,13,27,39,47,52 | 7, 27, 39, 47 | 1,27,38,39,43,47,66 |

| Target Variable: ITS-DA-p (32) | ||||

| Nodes(Comp. Of MB) |

1,4,7,15,23,30,36,47 60, 63 |

10,15,26,35,36,37,47 52, 63 |

1,15,18,35,36,38,47,58, 62 |

1,7,15,27,36,47,58 59 |

| Target Variable: RO-DA-p (39) | ||||

| Nodes(Comp. Of MB) |

7,15,24,43,56,62 | 7,12,24,43 | 7,15,23,24,47 | 7,23,24,32,43 |

| Target Variable: SI-DA-p (47) | ||||

| Nodes(Comp. Of MB) |

1,5,24,64 | 1, 24, 35, 65 | 1, 7, 24, 32, 50 | 1,7,24,32,46,50 |

| Note: for the full name of nodes & description, see Table 1. * Indicate the number of the variable in the Table 1 | ||||

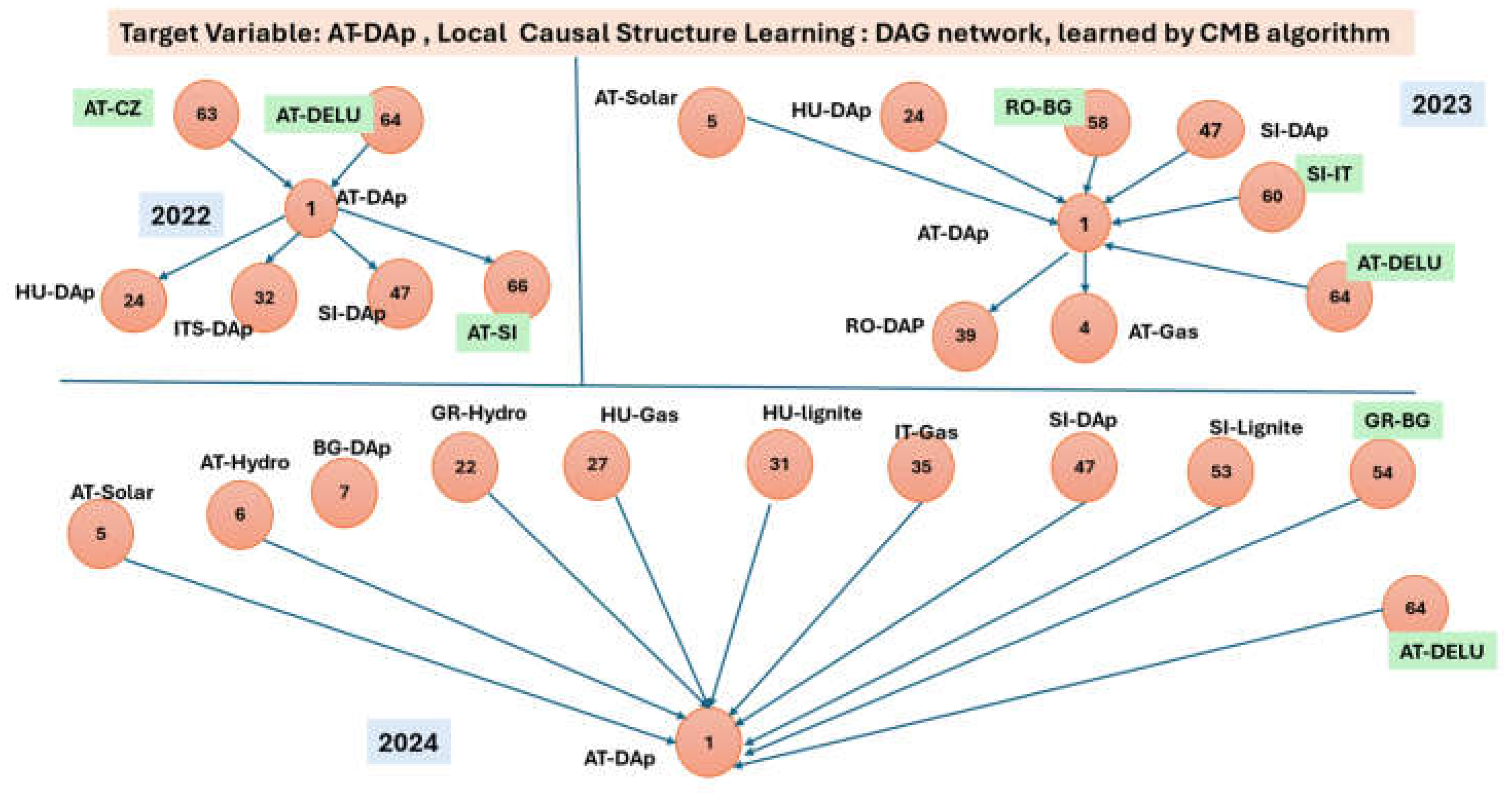

7.2. Local Causal Structure Learning LCSL Results

7.3. Results of Rolling Price Volatility Correlation and Cluster Analysis for Studying Spillover Effects.

7.3.1. Correlation of Rolling Volatility Curves and Their Clustering Process

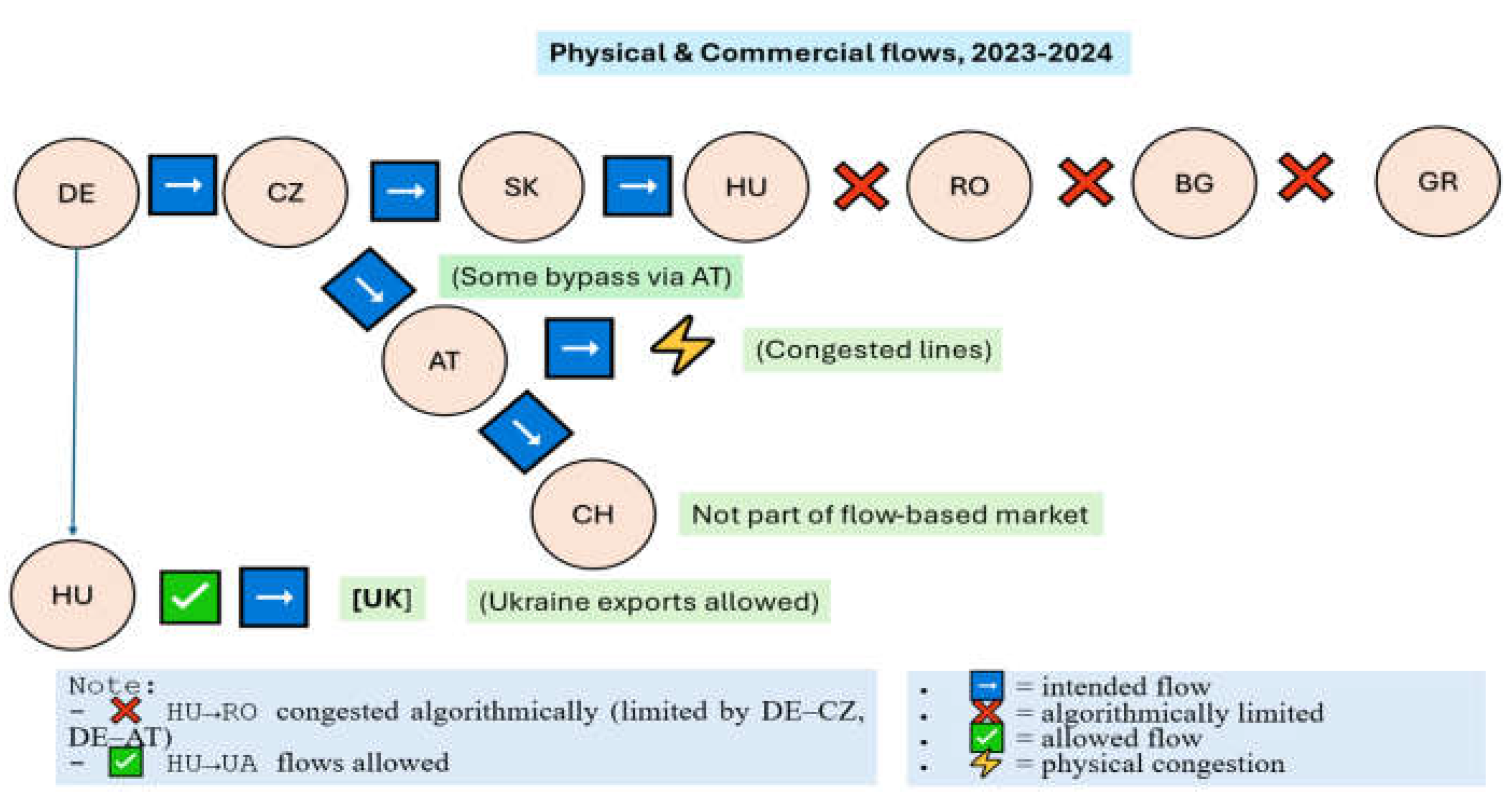

- When interconnection is “algorithmically blocked”, SEE CCR market prices surge, but DE/AT/HU can export at higher prices via different paths (or even import cheap and export expensive).

- If cross-zonal capacities are not allocated efficiently, this can create rent-seeking arbitrage opportunities, especially for dominant players (e.g., traders, utilities) in the core.

7.3.2. The Dendrogram of the Clustering Process

|

Cluster hierarchy |

Market fundamentals |

Cluster hierarchy |

Market fundamentals |

| 1st cluster | ROp-BGp | 9th cluster | BG-RO cbta with cluster 4 |

| 2nd cluster | HUp with cluster 1 | 10th cluster | IT-SI cbta with SI-IT |

| 3rd cluster | GRp with cluster 2 | 11th cluster | cluster 8 with 9 |

| 4th cluster | BG-GR cbta with GR-BG cbta | 12th cluster | RO-BG with GR-IT |

| 5th cluster | SIp with cluster 3 | 13th cluster | IT-GR cbta with cluster 7 |

| 6th cluster | ITSp with ATp | 14th cluster | AT-ITNorth cbta with cluster 11 |

| 7th cluster | cluster 6 with 5 | 15th cluster | AT-DE with AT-CZ cbta |

| 8th cluster | AT-HU cbta with AT-SI cbta | 16th cluster | cluster 10 with 14 |

7.3.3. The Behavior of the Target Model in the Issue of SEE Markets’ Price Surge

8. Discussion - Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

8.1. Policy Issues and Future Directions

8.2. Need for an EU-Wide Systemic Approach in Decision Making

8.3. Potential limitations, Challenges & How to Overcome Them

Supplementary Materials

| 1 | Biding zone: the largest geographical area where energy exchange can take place between players without capacity calculation. |

| 2 | Full:<1 Euro/MWh, Moderate: 1-10 Euro/MWh, Low: >10 Euro/MWh) |

| 3 | Two possible methods the EU rules allow for TSOs to calculate the capacity made available for trade between EU bidding zones in a coordinated manner: the coordinated net transfer capacity (CNTC) approach and the flow-based (FB) approach. The CNTC approach, can be applied in regions where cross-zonal exchanges are less interdependent, therefore no significant added value is expected to be gained from adopting the FB approach. The FB approach is defined as the default in areas of the transmission grid where the exchanges across bidding zone borders are highly interdependent, and models only a subset of network constraints, the so-called critical network elements with contingency (CNECs) (a line or transformer either within a bidding zone or between bidding zones). An optimized allocation of cross-zonal capacities at the level of the capacity calculation region is therefore allowed, by the price coupling mechanism that can allocate the capacity made available on each CNEC to the electricity exchanges that generate the largest ‘added social value’. |

| 4 | Commercial flows are redirected (e.g. to Ukraine) because of different impact factors, PTDFs (Power Transfer Distribution Factors) determine how much a MW transfer from A to B uses each line. RAM (Remaining Available Margin) is the headroom left on a line. If a transfer Germany → Romania "uses" too much of a congested line in Austria or Czechia, it's limited. Export Germany → Ukraine (via Slovakia) might "use" less congested lines (or different ones) → so it's allowed. The core flow-based domain thus shapes what trades can happen. |

References

- PMKM, 2024 (Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis letter to EC, 2024). (https://www.primeminister.gr/en/2024/09/13/34887). Downloaded 23 Dec. 2024.

- ACER, 2024. Transmission capacities for cross-zonal trade of electricity and congestion management in the EU, 2024 Market Monitoring Report, 3 July 2024.

- Draghi, M. (2024). The future of European competitiveness: A competitiveness strategy for Europe. European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/97e481fd-2dc3-412d-be4c-f152a8232961_en.

- Pellet, J.P.; Elisseeff, A. Using Markov Blankets for Causal Structure Learning (2008). Journal of Machine Learning Research 2008, 9, 1295–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Aliferis, C.F.; Statnikov, A.; Tsamardinos, I.; Mani, S.; Koutsoukos, X.D. . 2010. Local causal and Markov blanket induction for causal discovery and feature selection for classification part I: Algorithms and empirical evaluation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2010, 11, 171–234. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Liu, L.; Li, J. A unified view of causal and non-causal feature selection. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data 2021, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Hao, Z.; Mai, G.; Huang, H. Causal Feature Selection Method Based on Extended Markov Blanket. International Journal of Wireless and Mobile Computing (IJWMC) 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băncioiu, C.; Brad, R. Accelerating Causal Inference and Feature Selection Methods. (2021). Entropy 2021, 23, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Desmarais, M.C. Markov Blanket Based Feature Selection: A Review of Past Decade. Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2010 Vol I WCE 2010, June 30 - July 2, 2010, London, U.K.

- Bellizio, F.; Cremer, J.L.; Sun, M.; Strbac, G. A causality-based feature selection approach for data-driven dynamic security assessment. Electric power systems research 2021, 201, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonnave, M.; Delbianco, F.; Tohme, F.; Millios, E.; Maguitman, A. Learning causality structures from electricity demand data. Energy Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahara, J.; Hariadi, T.K. Improved Feature Selection Algorithm of Electricity Price Forecasting using SVM. Published in2022 2nd International Conference on Electronic and Electrical Engineering and Intelligent System (ICE3IS). [CrossRef]

- Mitridati, L.; Pinson, P. (2017). A Bayesian Inference Approach to Unveil Supply Curves in Electricity Markets. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. [CrossRef]

- Maticka, M.; Mahmoud, T. (2016). Bayesian Belief Networks: Redefining wholesale electricity price modelling in high penetration non-firm renewable generation power systems. [CrossRef]

- Nickelsen, D.; Muller, G. Bayesian Hierarchical Probabilistic Forecasting of Intraday Electricity Prices. arXiv:2403.05441v1 [stat.AP] 8 Mar 2024.

- Zholdasbayeva, M.; Zarikas, V. and Poulopoulos, S. Bayesian Networks based Policy Making in the Renewable Energy Sector. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2020) - Volume 2, pages 453-462 ISBN: 978-989-758-395-7; ISSN: 2184-433X. [CrossRef]

- Borunda, M.; Ballestros, A.R.; Jaramillo Ibarguegoytia, P. (2016). Bayesian networks in renewable energy systems: A bibliographical survey. Article in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. September 2016. [CrossRef]

- Guo Ying, (.B.).; Ni Yang Wang Yuan Zhao Jing Liu Liwei Research on Power Marketing Decision-Making Algorithm Based on Bayesian Network In, S.H.B.D.M. Zailani et al. (Eds.): ICMSEM 2023, 259, pp. 1245–1253, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Yu, K.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Wu, X. 2020. Using feature selection for local causal structure learning. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Topics Comput. Intell. [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. 2014. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Spirtes, P.; Clark; Glymour, N.; Scheines, R. 2000. Causation, Prediction, and Search. Vol. 81. MIT Press.

- Bell, D.; Wang, H. A formalism for relevance and its application in feature subset selection. Machine Learning 2000, 41, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Pocock, A.; Zhao, M.-J.; Lujan, M. Conditional likelihood maximization: A unifying framework for information theoretic feature selection. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2012, 13, 27–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, J.; Estevez, P.A. A review of feature selection methods based on mutual information. Neural Computing and Applications 2014, 24, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Ling, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Feature Selection for Efficient Local-to-Global Bayesian Network Structure Learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology.arXiv:2112.10369v1 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, K. 2013. Introduction to Statistical Pattern Recognition. Academic Press.

- Fano, R.M. 1961. Transmission of Information: A Statistical Theory of Communications. MIT Press.

- Hellman, M.E.; Raviv, J. Probability of error, equivocation and the chernoff bound. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1970, 16, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbe, D.; Dwyer, S. Uncertainty and the probability of error (Corresp.). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1968, 14, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review 2001, 5, 3–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R.; John, G.H. Wrappers for feature subset selection. Artificial Intelligence 1997, 97, 273–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamardinos, I.; Aliferis, C.F. 2003. Towards principled feature selection: Relevancy, filters and wrappers. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Koller, D.; Sahami, M. 1995. Toward optimal feature selection. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning. 284–292.

- Guyon, I. Constantin Aliferis Andre Elisseeff 2007 Causal feature selection Computational Methods of Feature Selection, H. Liu and H. Motoda (Eds.). CRC Press.

- Margaritis, D. and Sebastian Thrun. 2000. Bayesian network induction via local neighborhoods. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 505–511.

- Tsamardinos, I.; Constantin, F. Aliferis, Alexander R. Statnikov, and Er Statnikov. 2003b. Algorithms for large scale Markov blanket discovery. In Proceedings of the FLAIRS Conference. Vol. 2. 376–380.

- Yaramakala, S. and Dimitris Margaritis. 2005. Speculative Markov blanket discovery for optimal feature selection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM’05). IEEE, 4–9.

- Cevic, S.; Zhao, Y. Shocked: Electricity Price Volatility Spillover in Europe. IMF working paper 25/7 (2025).

- Diebold, F.; Yilmaz, K. Measuring Financial Asset Return and Volatility Spillovers, with Application to Global Equity Markets. Economic Journal 2009, 119, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.; Yilmaz, K. Better to Give Than to Receive: Predictive Directional Measurement of Volatility Spillovers. International Journal of Forecasting 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.; Yilmaz, K. On the Network Topology of Variance Decompositions: Measuring the Connectedness of Financial Firms. Journal of Econometrics 2014, 182, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; He, P.; Zheng, C.; Geng, Z. 2008. Partial orientation and local structural learning of causal networks for prediction. In Causation and Prediction Challenge. 93–105.

- Colombo, D.; Maathuis, M.H. Order-independent constraint based causal structure learning. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 3741–3782. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. , Ling, Z.; Yu, K.; Wu, X. Towards efficient and effective discovery of Markov blankets for feature selection. Inf. Sci. 2020, 509, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamardinos, I.; Aliferis, C.F.; Statnikov, A. 2003. Time and sample efficient discovery of Markov blankets and direct causal relations. In Proceedings of the Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD’03). ACM, 673–678.

- Borboudakis, G.; Tsamardinos, I. 2019. Forward-backward selection with early dropping. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 276–314. [Google Scholar]

- Aliferis, C.F.; Statnikov, A.; Tsamardinos, I.; Mani, S.; Koutsoukos, X.D. Local causal and markov blanket induction for causal discovery and feature selection for classifificationpart i: Algorithms and empirical evaluation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2010, 11, 171–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pena Roland Nilsson Johan Björkegren Jesper Tegnér 2007 Towards scalable data efficient learning of Markov boundaries Int, J. Approx. Reas. 2007, 45, 211–232.

- Rodrigues, S. De Morais and Alex Aussem. 2008. A novel scalable and data efficient feature subset selection algorithm. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML-PKDD’08). Springer, 298–312.

- Gao, T.; Ji, Q. Efficient Markov blanket discovery and its application. IEEE Trans. Cyber. 2017, 47, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Yu, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Ding, W.; Wu, X. BAMB: A balanced Markov blanket discovery approach to feature selection. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENTSO-E Main Report, Bidding Zone Review of the 2025 Target Year, www.entsoe.eu.

| Aspect | Austria (AT) | Romania (RO) |

|---|---|---|

| Median Prices | Lower (~100–200 EUR/MWh) | Higher (~200–300+ EUR/MWh) |

| Volatility | Lower | Higher |

| Outliers | Present but moderate | Frequent and extreme (>1000 EUR/MWh) |

| Negative Prices | Occasionally present | None observed |

| Peak Price Hours | Mornings and evenings | Spikes during mornings and especially evenings |

| Market Behavior | More stable and flexible | Higher stress and supply volatility |

| Market | avgPrice | medianPrice | St.Dev | IQR | minPrice | maxPrice | CV | Peak-Off-Peak Spread (PoPS) |

Extreme-FreqPct | skewness | kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 151.067 | 111.315 | 122.897 | 110.645 | -500.000 | 919.640 | 0.814 | 59.608 | 9.995 | 1.841 | 7.233 |

| BG | 154.763 | 119.295 | 119.108 | 114.435 | -45.000 | 950.010 | 0.770 | 94.164 | 9.995 | 1.802 | 7.339 |

| GR | 170.618 | 130.650 | 117.579 | 130.290 | -1.020 | 942.000 | 0.689 | 76.433 | 9.999 | 1.604 | 6.496 |

| HU | 161.898 | 120.970 | 128.535 | 119.975 | -500.000 | 1047.100 | 0.794 | 86.169 | 9.999 | 1.811 | 7.179 |

| ITS | 180.862 | 134.070 | 120.720 | 115.925 | 0.000 | 870.000 | 0.667 | 59.204 | 9.999 | 1.842 | 6.816 |

| RO | 159.411 | 119.750 | 128.138 | 117.520 | -106.360 | 1021.610 | 0.804 | 95.312 | 9.999 | 1.849 | 7.267 |

| SL | 159.725 | 117.910 | 126.317 | 120.660 | -500.000 | 1022.270 | 0.791 | 74.068 | 9.999 | 1.757 | 6.853 |

| Note: IQR : interquartile range, CV: Coefficient of Variation=std/mean, PoPS: Peak-off-peak spread i.e. avg price (7-10pm) - avg price (2-5am), Extreme-Freq Pct : frequency of extreme prices (%>90th percentile) | |||||||||||

| Market | Average Number of Outliers |

Total Number of Outliers |

|---|---|---|

| AT | 20.13 | 483 |

| BG | 26 | 630 |

| GR | 31 | 767 |

| HU | 27.1 | 651 |

| ITS | 30.5 | 733 |

| RO | 28 | 672 |

| SI | 24.6 | 592 |

| Global Causal Structure Learning (GCS) algorithms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acronym | Title of algorithm | Reference |

| GSBN | Grow/Shrink Bayesian network | [35] |

| GES | Greedy Equivalence Search | [53] |

| PC | PC | [21] |

| MMHC | Max-Min Hill-Climbing | [32] |

| PCstable | PC-stable | [43] |

| F2SL_c | Feature Selection-based Structure Learning using independence tests | [6] |

| F2SL_s | Feature Selection-based Structure Learning using score functions | [6] |

| Local Causal Structure (LCS) learning algorithms | ||

| PCDbyPCD | PCD-by-PCD | [42] |

| MBbyMB | MB-by-MB | [44] |

| CMB | Causal Markov Blanket | [18] |

| LCSFS | Local Causal Structure Learning by Feature Selection | [19] |

| Markov blanket (MB) learning algorithms | ||

| GS | Grow/Shrink algorithm | [35] |

| IAMB | Incremental Association-Based Markov Blanket | [45] |

| InterIAMB | Inter-IAMB | [36] |

| InterIAMBnPC | Inter-IAMBnPC | [32] |

| FastIAMB | Fast-IAMB | [37] |

| FBED | Forward-Backward selection with Early Dropping | [46] |

| MMMB | Min-Max MB | [45] |

| HITONMB | HITON-MB | [47] |

| PCMB | Parents and children-based MB | [48] |

| IPCMB | Iterative Parent-Child based search of MB | [9] |

| MBOR | MB search using the OR condition | [49] |

| STMB | Simultaneous MB discovery | [50] |

| BAMB | Balanced MB discovery | [51] |

| EEMB | Efficient and Effective MB | [52] |

| MBFS | MB by Feature Selection | [51] |

| Conditions* | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Markets share weather patterns | Likely weather-driven common volatility (hydro/wind output variability) |

| Markets are strongly interconnected | Likely volatility transmission via power flows/coupling mechanisms |

| Markets have similar generation mixes | Fuel-driven spillovers (e.g., gas price shocks affect both) |

| *Note: Real examples of market conditions are the results in Figure 24 and Table 13, in the results section. | |

| Scenario | Implication |

|---|---|

| Market A has persistent high volatility, and others show delayed rise | A is likely a volatility transmitter |

| Market A is small but strongly correlated with a larger hub | Possibly price-taking market with imported volatility |

| Markets with weak coupling show weak correlation | Physical/market coupling is crucial for volatility transmission |

| Local Causal structure learning LCSL: algorithm CMB | |||

| Target Variable: AT-DA-p (1*) | |||

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| Parents Children Spouses |

63, 64 24, 32, 47, 66 - |

5, 24, 47, 58, 60, 64 4, 39 - |

5, 6, 7, 22, 27, 31, 35, 47, 53, 54, 64 - - |

| Target Variable: BG-DA-p (7) | |||

| Parents Children Spouses |

1, 6, 15, 19, 35, 39, 42 46 - - |

5, 15, 31, 52, 60, 66 28, 39 - |

24, 39 15, 21, 50 - |

| Target Variable: GR-DA-p (15) | |||

| Parents Children Spouses |

7, 19, 32, 39,47 22, 44 - |

7, 10, 14, 19,22,32,37,54 - - |

7, 19, 20, 32, 39, 45, 46 5 - |

| Target Variable: HU-DA-p (24) | |||

| Parents Children Spouses |

1, 18, 39, 43 47 - |

1, 13, 22, 25, 29, 39, 47,52 - |

39 7, 27,29,43,47, 55 - |

| Target Variable: ITS-DAp (32) | |||

| Parents Children Spouses |

7, 61 1,10,15,23,30,36,47,56,60,63 - |

5, 7,15,29,35,36,47,52,63 25 - |

1,15, 18,36,38,47 35, 58, 62 - |

| Target Variable: RO-DAp (39) | |||

| Parents Children Spouses |

7,15,24,43,56 62, 67 - |

1,5,7,35 24 - |

7,15,24,47 23, 43 - |

| Target Variable: SI-DAp (47) | |||

| Parents Children Spouces |

1,12,38 24, 32, 64 |

31, 35 1, 24, 39, 65 - |

32, 38 1, 7, 24, 37, 50 |

| Notes: for the full name of nodes & description, see Table 1. Numbers in bold indicate variables included in the Markov Blanket (MB) but now equipped with direction arrows. * Indicate the number of the variable in Table 1. | |||

| From | To | Flow Status | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| DE → CZ → HU → RO | BG | Limited (❌) | Congestion upstream (DE–CZ, AT) |

| HU → UA (Ukraine) | Allowed (✅) | Lower congestion impact | |

| DE/AT → CH | No market coupling (⚡) | Switzerland outside EU market |

| Aspect | Result in 2023–24 | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Price convergence | ❌ Failed | Prices in SEE diverged strongly from Core (DE/AT/CZ) |

| Grid physical realism | ✅ Worked | FBMC realistically modeled grid congestions |

| Market integration | ❌ Partially failed | SEE countries were semi-isolated |

| Security of supply | ✅ Generally OK | No blackouts, but expensive |

| Efficient capacity use | ❌ Not optimal | Some capacities underused (especially HU→RO) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).