1. Introduction

The liberalization of electricity markets worldwide has created one of the most volatile and complex commodity markets, characterized by unique features that challenge traditional financial modeling approaches. Unlike storable commodities, electricity must be produced and consumed instantaneously, creating price dynamics fundamentally different from traditional financial assets. The integration of renewable energy sources over the past decade has further transformed these dynamics, introducing unprecedented volatility and regularly driving prices negative when renewable generation exceeds demand.

This paper develops a comprehensive stochastic model for electricity spot prices that captures the extreme statistical properties observed in modern power markets. Through extensive empirical analysis of German electricity spot prices from the EPEX SPOT exchange covering 2015-2025, we document several striking features that necessitate departures from standard modeling approaches. The coefficient of variation exceeds 2.4, far surpassing typical commodity markets where values rarely exceed 0.5 [

104]. Prices regularly turn negative, occurring in 16.99% of 15-minute intervals, reflecting periods when generators pay consumers to take electricity due to inflexible baseload generation and high renewable output. Most critically, we find asymmetric heavy-tailed distributions with power-law indices of

for positive price excursions and

for negative excursions.

The empirical finding that has profound theoretical implications: it implies infinite variance for negative price movements, invalidating standard mean-variance approaches and requiring careful mathematical treatment through sigma-martingale theory. This heavy-tailed behavior is not merely a statistical curiosity but reflects fundamental market mechanics where oversupply conditions, constrained by must-run generation and limited storage, can create more extreme negative prices than scarcity creates positive prices.

Our contribution is threefold. First, we provide comprehensive empirical documentation of German electricity prices during a period of dramatic renewable expansion, revealing extreme statistical properties including tail indices approaching theoretical boundaries where moments become infinite. Second, we develop a semimartingale model combining mean-reverting diffusion with compound Poisson jumps following asymmetric Pareto distributions, demonstrating how this framework naturally accommodates negative prices and captures observed market dynamics. Third, we establish the mathematical foundations for pricing and risk management when classical assumptions fail, showing how sigma-martingale theory ensures arbitrage-free pricing even with infinite variance.

The model we propose belongs to the class of semimartingale processes and can be written as:

where

captures deterministic seasonality through Fourier decomposition,

follows an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process representing normal fluctuations, and

is a mean-reverting jump process with asymmetric Pareto-distributed jump sizes. This additive structure, aligned with recent advances by Aïd et al. [

1], naturally accommodates negative prices without requiring artificial transformations like shifting or logarithmic modifications.

Our calibration results reveal important asymmetries in electricity markets. While jump frequencies are nearly balanced between positive and negative events (), the tail behavior differs dramatically. The negative tail index indicates that extreme negative price events follow a distribution so heavy-tailed that variance becomes infinite, while the positive tail with maintains finite second moments. This asymmetry emerges from fundamental market characteristics: when supply exceeds demand, the inability to store electricity combined with must-run constraints can drive prices arbitrarily negative, whereas positive price spikes are ultimately limited by demand destruction and emergency imports.

The theoretical implications extend beyond model specification to fundamental questions about market operation and risk management. We show that futures prices remain well-defined despite infinite spot price variance, deriving explicit pricing formulas under appropriate equivalent martingale measures. However, the heavy-tailed nature fundamentally alters risk management: traditional measures like Value-at-Risk converge slowly, variance-based portfolio optimization becomes inapplicable, and hedging strategies must account for potentially infinite hedge error variance.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that electricity’s extreme volatility is not merely a risk to be hedged but a fundamental cost driver. Through mathematical analysis and empirical evidence, we show how volatility increases average prices through multiple channels: Jensen’s inequality effects from convex supply curves, risk premiums in forward contracts, expensive reserve requirements, and elevated hedging costs. These findings have important policy implications, suggesting that investments in storage, demand response, and grid flexibility could significantly reduce electricity costs by dampening volatility.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents our comprehensive empirical analysis of German electricity spot prices.

Section 3 develops the theoretical model and discusses its mathematical properties.

Section 4 addresses the embedding in a general semimartingale framework and derives futures pricing results.

Section 5 presents model calibration and validation through Monte Carlo simulation.

Section 6 analyzes how volatility drives electricity costs.

Section 7 concludes.

2. Empirical Analysis of German Electricity Spot Prices

The European electricity market represents one of the most complex and dynamic commodity markets globally, characterized by the unique non-storability of electricity and the requirement for instantaneous supply-demand balance [

46,

124]. Unlike traditional commodity markets, electricity markets operate through a sequence of interconnected trading venues, from long-term bilateral contracts to day-ahead auctions and real-time balancing markets [

62]. The fundamental constraint that supply must equal demand at every moment, combined with transmission network limitations and regulatory frameworks, creates a market structure fundamentally different from other commodities [

22].

The integration of renewable energy sources has dramatically transformed electricity market dynamics over the past decade [

79,

128]. Wind and solar generation, characterized by their intermittent and weather-dependent nature, introduce unprecedented volatility into the system [

59,

108]. This volatility manifests not only in price fluctuations but also in the frequency of extreme events, including negative prices when renewable generation exceeds demand and system flexibility [

48,

109]. The German market, with its aggressive renewable energy targets under the Energiewende policy, experiences particularly extreme price dynamics [

51,

57].

The interconnected nature of European electricity markets adds another layer of complexity through cross-border flows and market coupling mechanisms [

78,

101]. While market integration theoretically improves efficiency and security of supply, it also transmits volatility and extreme events across borders [

58]. Germany’s central position in the European grid and its high renewable penetration make it a critical node for understanding modern electricity market dynamics [

68].

We focus our empirical analysis on the German electricity market, specifically the EPEX SPOT exchange, which exhibits some of the most extreme price behavior globally [

80,

100]. The German market regularly experiences both extreme positive spikes and negative prices, making it an ideal laboratory for studying electricity price dynamics under high renewable penetration [

54,

99].

2.1. Data Description and Basic Statistics

Our dataset comprises spot prices from the German-Luxembourg bidding zone obtained through the ENTSO-E Transparency Platform API, covering the period from January 1, 2015, to June 1, 2025. The data represents day-ahead auction results from EPEX SPOT at 15-minute resolution. We obtain 15-minute EPEX SPOT day-ahead prices and resample to hourly means for the empirical analysis; let

T denote the resulting number of hourly observations over this sample period. This publicly available data captures the evolution of prices through significant structural changes in the German electricity system, including the phase-out of nuclear power and rapid expansion of renewable capacity [

71].

It is important to note that while current EPEX SPOT day-ahead markets operate with harmonized price bounds (floor of -500 EUR/MWh and cap of 5,000 EUR/MWh as of September 20, 2022), our dataset includes historical periods before these constraints were uniformly implemented. Prior to the harmonization of price caps across European markets, extreme price excursions beyond current limits were possible during exceptional market conditions. Additionally, data anomalies from the aggregation process or reporting errors may contribute to outliers that require careful treatment in the analysis.

From a modeling perspective, we deliberately choose not to incorporate price bounds in our theoretical framework. Price caps and floors, while important for market operations, distort the true interaction of supply and demand forces that drive electricity prices. To understand the fundamental market dynamics and extreme event probabilities, it is essential to model the unbounded price process that would emerge from physical and economic constraints alone. The presence of pre-harmonization data in our sample, where prices could exceed current bounds, provides valuable information about tail behavior under extreme market stress. This unconstrained data allows us to calibrate models that capture the true severity of supply-demand imbalances, which is crucial for risk management and understanding the economic value of flexibility resources. Artificial truncation at regulatory bounds would underestimate tail risks and obscure the underlying economic signals that prices convey about system scarcity.

Understanding the basic statistical properties of electricity prices is fundamental for model selection and risk management [

89]. The first two moments provide information about the central tendency and dispersion, while higher moments reveal the asymmetry and tail behavior crucial for extreme event modeling. For our hourly aggregated data, we calculate the sample moments as:

where

denotes the spot price at time

t, and

T is the total number of hourly observations.

The statistics in

Table 1 reveal several striking features. The coefficient of variation of 2.444 indicates volatility far exceeding typical commodity markets, where values rarely exceed 0.5 [

104]. The extreme skewness and kurtosis values indicate severe departures from normality, necessitating models that can capture both frequent small variations and occasional extreme events [

96]. However, it should be noted that these extreme values for higher-order moments are dominated by the rare extreme observations that exceed current market bounds, and robust estimation methods might yield more stable estimates.

The distinction between 15-minute and hourly negative price frequencies is particularly important: while 16.99% of 15-minute intervals show negative prices, only 8.47% of hourly averages are negative, demonstrating the impact of temporal aggregation on price statistics. The difference illustrates aggregation effects: averaging four quarter-hour prices materially lowers the frequency of negative hourly values. This high frequency of negative prices reflects periods when generators pay consumers to take electricity due to inflexible baseload generation and high renewable output [

21].

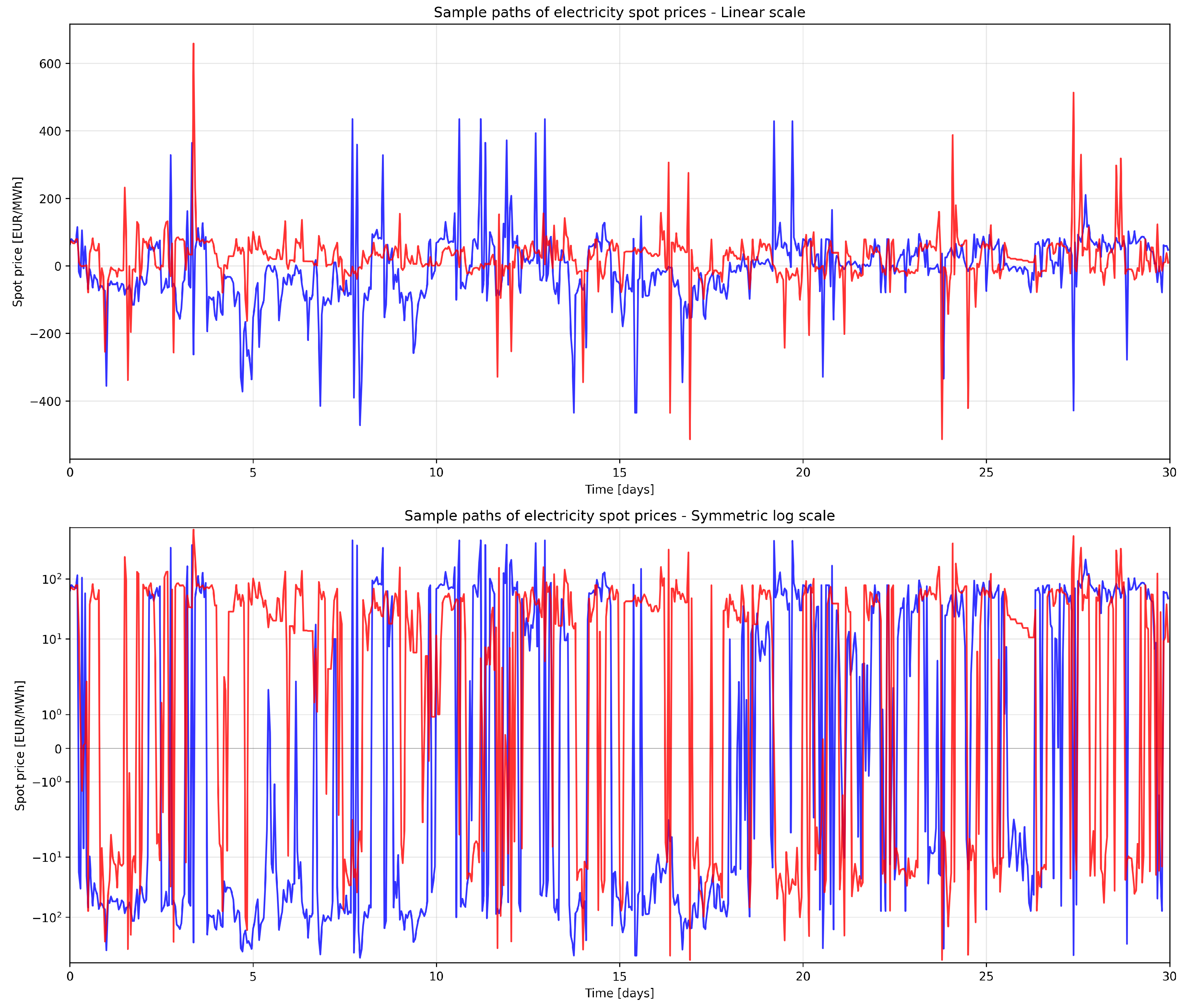

Figure 1 illustrates the characteristic behavior of electricity spot prices through three 30-day sample paths. The extreme volatility is immediately apparent, with prices ranging from negative values to spikes exceeding 2000 EUR/MWh. The zoomed view in the lower panel provides a comprehensive view of price dynamics, showing the mean-reverting nature of the price process, with excursions from the mean being followed by rapid returns to normal levels [

11].

2.2. Annual Seasonality Removal

Before analyzing the structural properties of electricity prices, it is essential to remove long-term seasonal patterns that could confound the estimation of mean reversion, jump dynamics, and other structural parameters. We employ STL (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess) decomposition to extract the annual seasonal component:

where

represents the long-term trend,

is the annual seasonal component, and

contains the remaining dynamics including intraday patterns, jumps, and stochastic variations.

We estimate the annual component via STL with period 8760 (hours in a non-leap year) and subtract it from the hourly series to obtain deseasonalized prices:

This approach is robust to outliers and missing values, using the iterative loess smoothing inherent in the STL algorithm. The method effectively separates annual patterns from shorter-term dynamics while preserving the essential statistical properties of the price series.

The decomposition results shown in

Figure 2 reveal a modest annual seasonal pattern with a range of approximately 42.24 EUR/MWh. The seasonal strength metric of 0.001 indicates that annual seasonality explains only 0.1% of the total variance, confirming that short-term volatility dominates the price dynamics. This weak annual seasonality is characteristic of electricity markets where weather-dependent demand and supply patterns are overlaid with substantial noise from market dynamics, fuel price variations, and renewable generation variability [

122].

The deseasonalized data retains the essential statistical properties: mean of 58.76 EUR per MWh (compared to 58.16 for raw data) and standard deviation of 142.04 EUR/MWh (compared to 142.12). For context, in the underlying quarter-hour series, the negative price frequency changes marginally from 16.99% to 17.76% after deseasonalization, while the hourly aggregated series shows a similar modest change. The minimal impact on these statistics confirms that annual seasonality removal does not distort the fundamental price dynamics while providing cleaner estimates of structural parameters.

2.3. Fourier Decomposition of Intraday and Weekly Patterns

To capture the regular intraday and weekly patterns in electricity prices, we apply Fourier decomposition to the deseasonalized data. Following Geman and Roncoroni [

53], we model the deterministic seasonal component as:

where

is the base level,

denotes the hour of day,

and

are the number of harmonics for daily and weekly patterns respectively, and the coefficients are estimated using least squares on the deseasonalized data aggregated to hourly resolution.

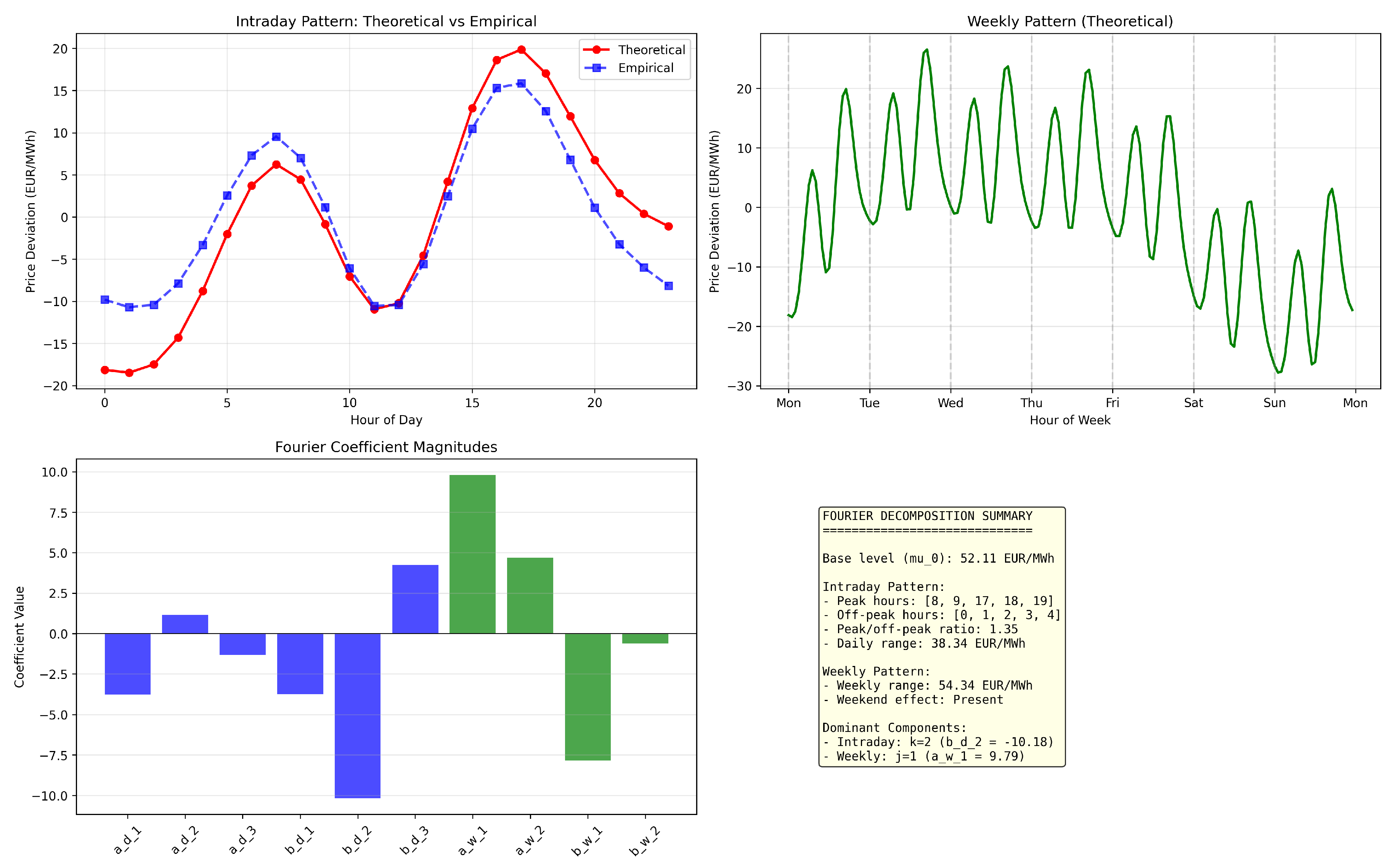

The Fourier decomposition shown in

Figure 3 successfully captures the periodic patterns with high fidelity. The intraday pattern exhibits the characteristic double-peak structure with morning peaks around 8-9 AM and evening peaks around 6-8 PM, with a peak/off-peak ratio of 1.35. The R² of 0.943 for the intraday fit confirms that three harmonics adequately capture the daily variation. The weekly pattern shows lower prices on weekends, with Sunday having the lowest average prices. The estimated Fourier coefficients are presented in

Table 2.

2.4. Log Returns Analysis

The analysis of price changes through log returns provides insights into the dynamic behavior of electricity prices and is essential for volatility modeling and derivative pricing [

125]. For positive prices, log returns are defined as:

However, the presence of negative prices in electricity markets requires a modification to the standard approach. Following [

109], we employ the generalized logarithm transformation:

This transformation preserves the sign of prices while maintaining the desirable properties of log returns for large price movements.

The distributional analysis of returns is crucial for understanding price dynamics and selecting appropriate stochastic models. We test for normality using the Jarque-Bera statistic:

where

represents the null hypothesis of normality. For the hourly log returns with

T observations, the computed skewness of 0.020 and excess kurtosis of 4.451 yield a Jarque-Bera statistic that decisively rejects normality, providing evidence of heavy-tailed behavior in electricity returns.

The log returns analysis in

Figure 4 reveals several important stylized facts. The distribution exhibits significant excess kurtosis (4.451) indicating heavy tails, while maintaining near-zero skewness (0.020). The Jarque-Bera test strongly rejects normality (p-value < 0.001), consistent with findings in electricity price literature [

96]. The QQ-plot shows systematic deviations from normality, particularly in the tails, suggesting the presence of jumps or extreme events that cannot be captured by continuous diffusion models [

27].

The autocorrelation function (ACF) of log returns shows rapid decay, indicating limited linear dependence. However, this does not imply independence, as evidenced by the significant autocorrelation in squared returns shown in

Figure 5. This pattern is characteristic of GARCH-type effects and motivates the use of stochastic volatility models [

83].

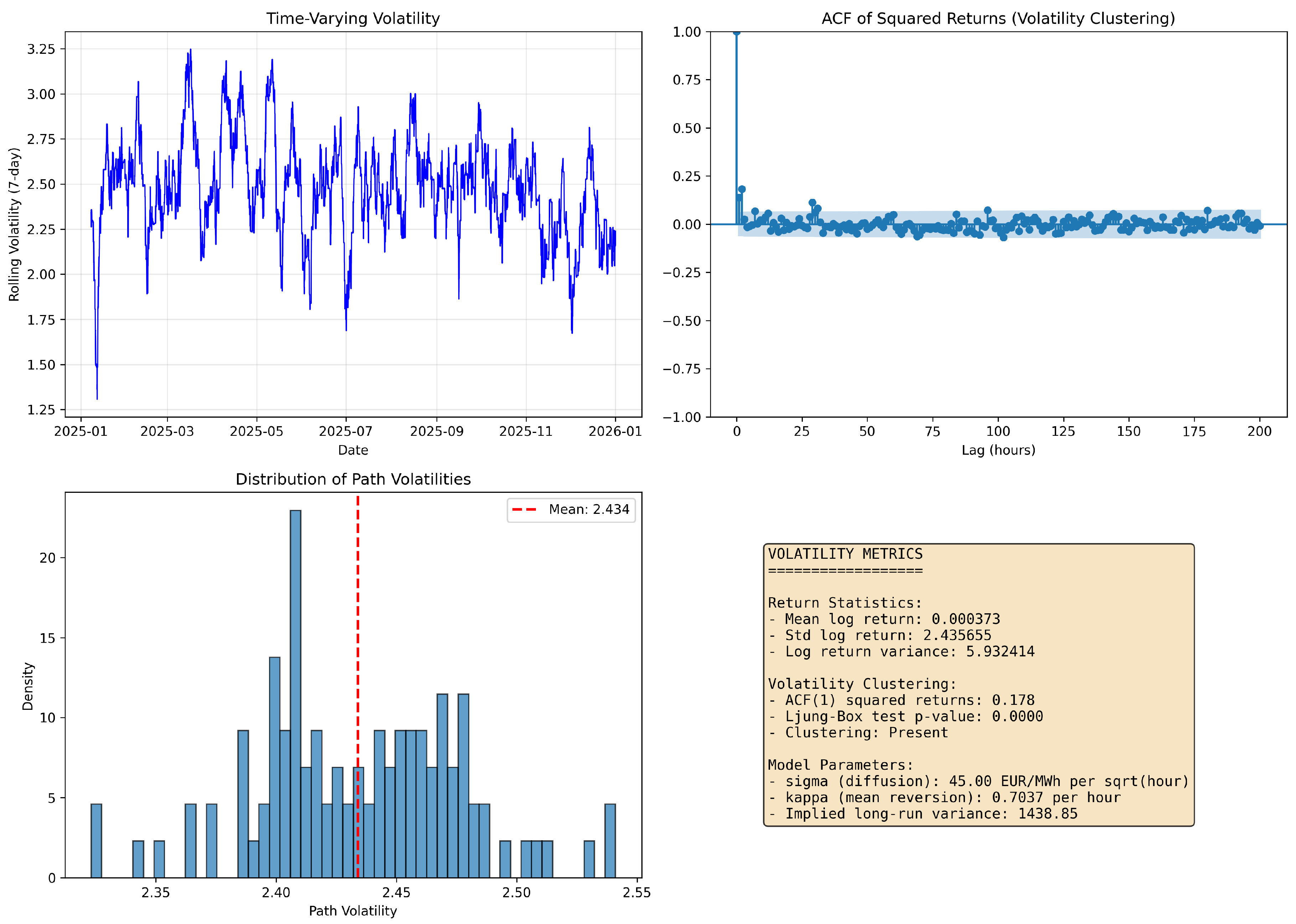

2.5. Volatility Clustering Analysis

Volatility clustering, where large price changes tend to be followed by large changes of either sign, is a ubiquitous feature of commodity markets [

90]. For electricity prices, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced due to the interaction between weather-dependent supply and demand, planned maintenance, and unexpected outages [

77].

We analyze volatility clustering through the autocorrelation function of squared returns:

Additionally, we compute time-varying volatility using a rolling window approach:

with

hours (one week) to capture weekly patterns while maintaining sufficient responsiveness.

Figure 5 demonstrates strong evidence of volatility clustering. The ACF of squared returns shows significant autocorrelation with slow decay (Ljung-Box test p-value < 0.001 for lags up to 200), indicating that volatility shocks persist for extended periods. The autocorrelation at lag 1 is approximately 0.31, indicating that volatility shocks have a persistence measure corresponding to roughly 31% correlation after one hour. This persistence of volatility - distinct from the mean reversion of price levels - reflects the physical constraints and operational characteristics of electricity systems [

53]. The time-varying volatility plot reveals distinct regimes, with particularly elevated volatility during 2021-2022 corresponding to the European energy crisis. The volatility ranges from below 1 during calm periods to over 5 during crisis periods, representing a five-fold increase that has important implications for risk management and derivative pricing [

10].

2.6. Structural Parameter Estimation

To estimate the structural parameters of electricity price dynamics, we analyze the deseasonalized data to separate the effects of mean reversion, jumps, and stochastic volatility from seasonal patterns. This approach provides cleaner estimates of the fundamental price dynamics.

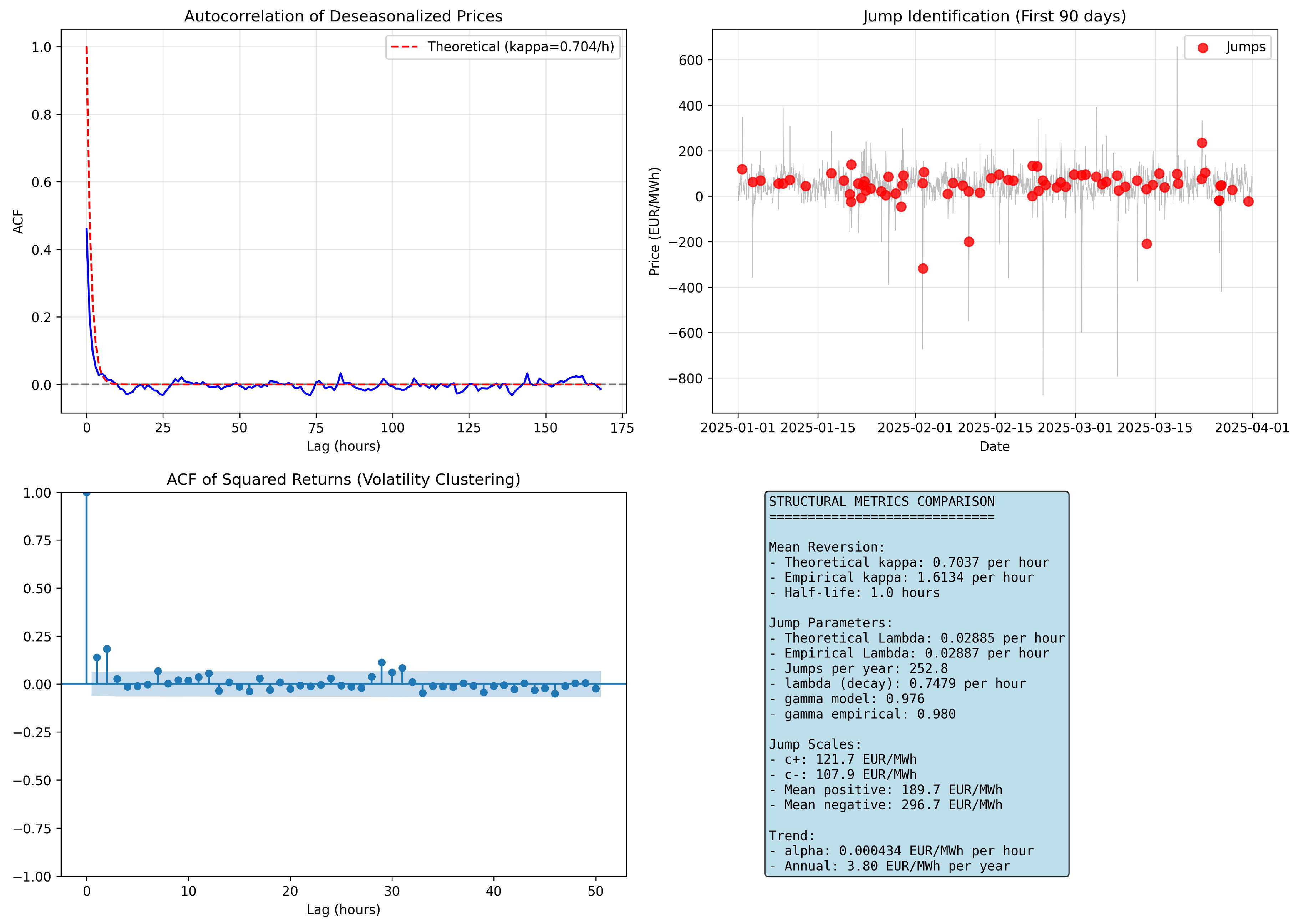

2.6.1. Mean Reversion

The mean reversion rate

is estimated from the autocorrelation function of deseasonalized prices aggregated to hourly resolution:

where ACF(1) denotes the first-order autocorrelation. For the deseasonalized hourly data, we obtain

per hour, corresponding to a half-life of

hours. Because jumps add short-lag dependence,

should be read as an OU-equivalent mean-reversion speed - the rate that would generate the same first-order autocorrelation in a pure Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. This rapid mean reversion reflects the inability to store electricity and the requirement for continuous supply-demand balance.

2.6.2. Jump Parameters

Jump detection on deseasonalized data uses a rolling window approach to identify extreme deviations:

where

and

are the rolling mean and standard deviation over a weekly window (168 hours for hourly data). The analysis on hourly aggregated data identifies 3,908 jumps over the sample period, yielding a jump intensity of

. The ratio of negative to positive jumps is

, indicating a slight bias toward negative jumps, consistent with the asymmetric response of electricity systems to supply and demand shocks.

Figure 6.

Structural parameter estimation results. Top left: ACF of deseasonalized prices with exponential decay fit. Top right: Jump detection on deseasonalized data. Bottom left: ACF of squared returns showing volatility clustering. Bottom right: Summary of structural parameter estimates.

Figure 6.

Structural parameter estimation results. Top left: ACF of deseasonalized prices with exponential decay fit. Top right: Jump detection on deseasonalized data. Bottom left: ACF of squared returns showing volatility clustering. Bottom right: Summary of structural parameter estimates.

2.6.3. Trend Analysis

Long-term trends in electricity prices reflect fundamental changes in the generation mix, fuel costs, environmental regulations, and market structure [

113]. We estimate the trend parameter

using linear regression on deseasonalized data:

The estimated trend is EUR/MWh per hour, or 3.46 EUR/MWh per year. The Kendall rank correlation test confirms the statistical significance of this trend (, p-value < 0.001).

2.7. Periodicity and Spectral Analysis

Electricity demand, and consequently prices, exhibit strong periodic patterns driven by human activity cycles [

33]. Understanding these patterns is crucial for forecasting and operational planning. We analyze periodicity using spectral methods, which decompose the price series into frequency components.

The periodogram provides a non-parametric estimate of the power spectral density:

where

is the centered price series and

are the Fourier frequencies.

For improved estimates, we employ Welch’s method [

120], which averages periodograms of overlapping segments:

where

is the periodogram of the

k-th windowed segment.

The spectral analysis in

Figure 7 reveals a rich periodic structure. The power spectrum exhibits clear peaks at frequencies corresponding to 24-hour (daily) and 168-hour (weekly) cycles, with the daily frequency showing the strongest signal. The spectrum shows strong peaks at daily and weekly cycles. The low-frequency slope indicates persistent correlation at multi-day scales, while the high-frequency decay (

with

) reflects short-horizon roughness characteristic of electricity prices [

8]. Additional peaks at harmonics of the fundamental frequencies (12 hours, 8 hours, 6 hours) reflect the multi-peaked nature of daily demand patterns.

The autocorrelation function provides complementary evidence, with significant correlations at lags of 24, 48, and 168 hours persisting even after 7 days. This persistent correlation structure has important implications for time series modeling, suggesting that models must incorporate both short-term dynamics and long-term periodic components [

122].

2.8. Daily Seasonal Decomposition

To analyze the short-term seasonal patterns in detail, we apply STL (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess) [

32] with a daily period. This decomposition separates the intraday patterns from longer-term dynamics:

where

is the trend component,

is the 24-hour seasonal component, and

is the remainder. The decomposition uses locally weighted regression (loess) to extract components iteratively.

The strength of the daily seasonality can be quantified as:

The STL decomposition in

Figure 8 successfully separates the different price components on a daily basis. The seasonal component exhibits a clear 24-hour pattern with amplitude of approximately ±15 EUR/MWh, representing about 25% of the mean price. The visualization shows 30 days of the seasonal pattern to better illustrate its consistency across multiple weeks. The seasonal strength metric

indicates that daily seasonality explains 73% of the detrended variance, confirming its importance in price formation. The residual component contains the irregular price movements, including spikes and drops, which require separate modeling approaches [

72].

2.9. Intraday and Weekly Patterns

The regular patterns in electricity prices reflect the underlying patterns in electricity demand and supply availability. We analyze these patterns by computing conditional statistics:

for hourly patterns, and similarly for day-of-week effects.

The seasonal analysis in

Figure 9 reveals several important patterns. The intraday profile shows the characteristic double-peak structure, with morning peaks around 8-9 AM (mean price 65 EUR/MWh) and evening peaks around 6-8 PM (mean price 70 EUR/MWh). Off-peak hours (2-5 AM) average 45 EUR/MWh, creating a peak/off-peak ratio of approximately 1.35. The standard deviation also varies systematically, being highest during peak hours when system constraints are most likely to bind.

Weekly patterns show significantly lower prices on weekends (average 48 EUR/MWh) compared to weekdays (average 62 EUR/MWh), reflecting reduced industrial demand. The hour-day heatmap reveals that Sunday nights have the lowest prices, while Wednesday and Thursday evenings show the highest prices, consistent with industrial production patterns in Germany [

68].

Particularly revealing is the distribution of negative prices by hour, calculated from our 15-minute data. Negative prices occur most frequently during night hours (1-5 AM) with frequencies exceeding 20% of 15-minute intervals, and during midday hours (11 AM - 3 PM) with frequencies around 18%. This bimodal pattern reflects two different mechanisms: nighttime negative prices result from inflexible baseload generation during low demand, while midday negative prices occur during high solar production [

99].

2.10. Spike Analysis

Price spikes represent extreme deviations from normal price levels and pose significant risks for market participants [

30]. We define spikes as extreme price levels identified using a dynamic threshold approach based on rolling statistics:

where

and

are rolling mean and standard deviation over window

hours, and

is the threshold parameter.

The spike analysis in

Figure 10 identifies 3,405 spike events (extreme price levels) over the sample period (approximately 10.4 years), split between 1,529 positive spikes and 1,876 negative spikes. This corresponds to approximately 327 spikes per year or 0.89 spikes per day, indicating that extreme price levels are a regular feature of the German electricity market rather than rare occurrences.

The spike magnitude distribution follows a power law in the tails:

with estimated tail index

for both positive and negative spikes. The inter-arrival time analysis reveals that spikes do not occur uniformly in time. The distribution of waiting times between spikes follows approximately an exponential distribution with rate parameter

days

, but with excess probability at short intervals indicating clustering. This clustering effect reflects the persistence of system stress conditions [

53].

2.11. Jump Analysis

While spikes represent extreme price levels, jumps capture rapid price changes that may indicate system shocks or information arrival [

20]. We now analyze each of the three discontinuity metrics from the definition box:

Standardized jumps: Identified on deseasonalized data using a rolling window approach:

where

and

are the rolling mean and standard deviation over a weekly window (168 hours). This method identifies 3,908 standardized jumps over the sample period, yielding a jump intensity of

(approximately 119 jumps per year).

Relative price jumps: Identified using the relative price change criterion:

where

is the daily price range and

is the threshold parameter.

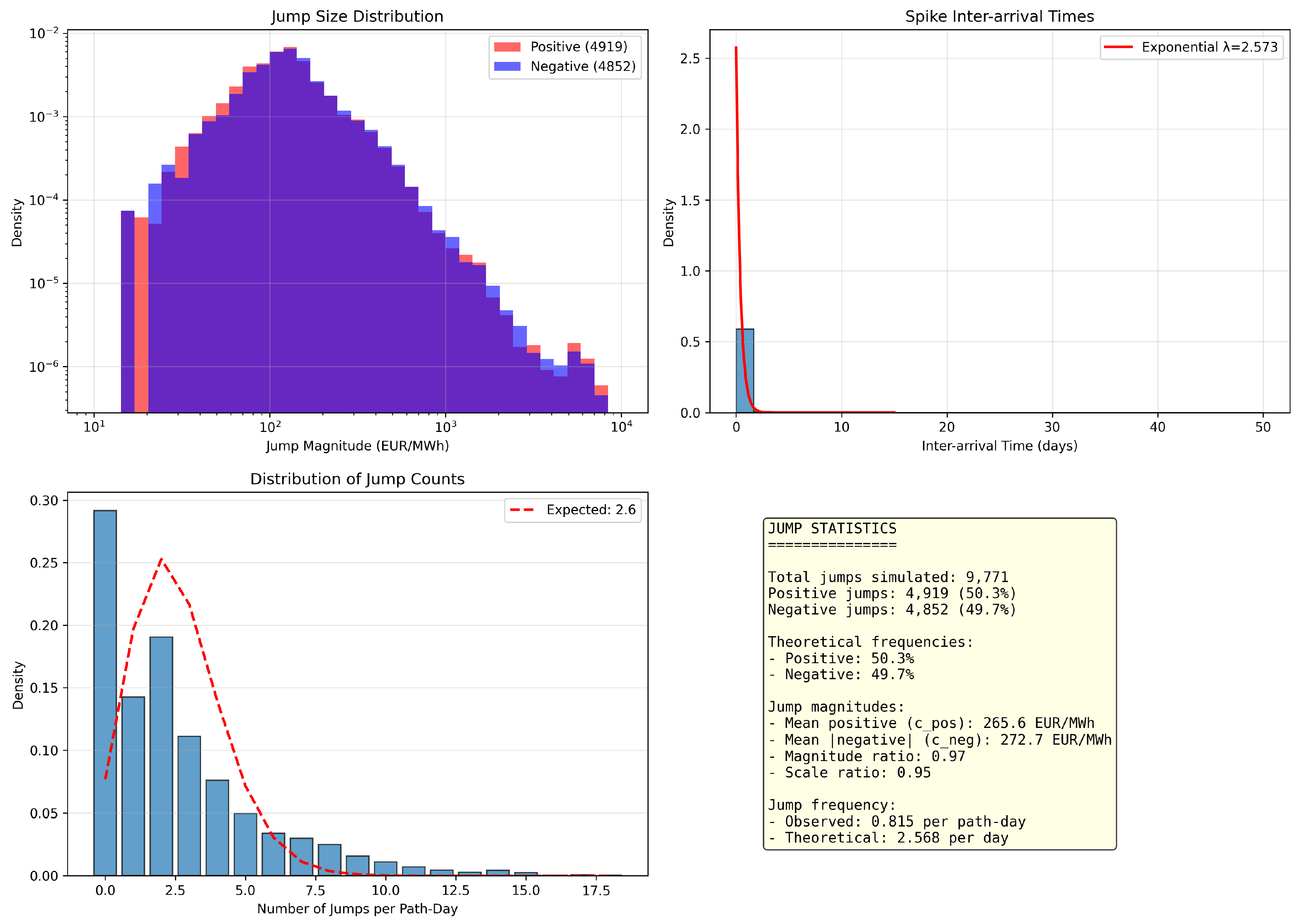

The relative jump analysis in

Figure 11 identifies 9,771 significant price changes over the sample period, with a remarkably balanced distribution between positive (50.3%) and negative (49.7%) jumps. This corresponds to approximately 2.56 relative jumps per day, reflecting rapid hour-to-hour price adjustments. The average jump magnitudes are 265.6 EUR/MWh for positive jumps and 272.7 EUR/MWh for negative jumps, with standard deviations exceeding the means, confirming the heavy-tailed nature of jump sizes.

The distinction between standardized jumps (119 per year) and relative price jumps (2.56 per day) reflects different aspects of price dynamics: standardized jumps capture departures from the rolling mean (level outliers), while relative jumps capture large hour-to-hour changes regardless of the prevailing price level. Both metrics provide important calibration targets for jump models.

Crucially, our jump-scale metrics reveal important calibration parameters for theoretical models:

The near-unity jump magnitude ratio of 0.97 indicates that positive and negative jumps have remarkably similar average sizes, despite their different underlying causes. This symmetry in jump magnitudes, combined with the slight asymmetry in frequency ( for standardized jumps), provides key calibration targets for jump models. The values of and EUR/MWh represent the characteristic scale of extreme price movements and can be interpreted as the minimum jump sizes in Pareto-based jump models. We use Pareto Type-I tails above thresholds ; setting would make the Lévy measure non-integrable.

Table 3.

Jump-Scale Metrics

Table 3.

Jump-Scale Metrics

| Parameter |

Value |

|

(mean positive jump) [] |

265.65 |

|

(mean negative jump) [] |

272.73 |

| Jump magnitude ratio |

0.97 |

The distribution of daily jump counts deviates from the Poisson model, showing excess probability for days with multiple jumps. This clustering of jumps within days reflects the fact that system stress conditions often persist for several hours, leading to multiple price adjustments [

60].

2.12. Extreme Value Analysis

Understanding the tail behavior of electricity prices is crucial for risk management and system reliability assessment. We employ extreme value theory to characterize the distribution of extreme prices, with particular focus on the asymmetry between positive and negative tails.

For tail analysis, we employ both the Hill estimator and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) as a fallback for robust estimation of the tail index. The tail behavior is characterized by the Pareto distribution:

where

u is the threshold and

is the tail index.

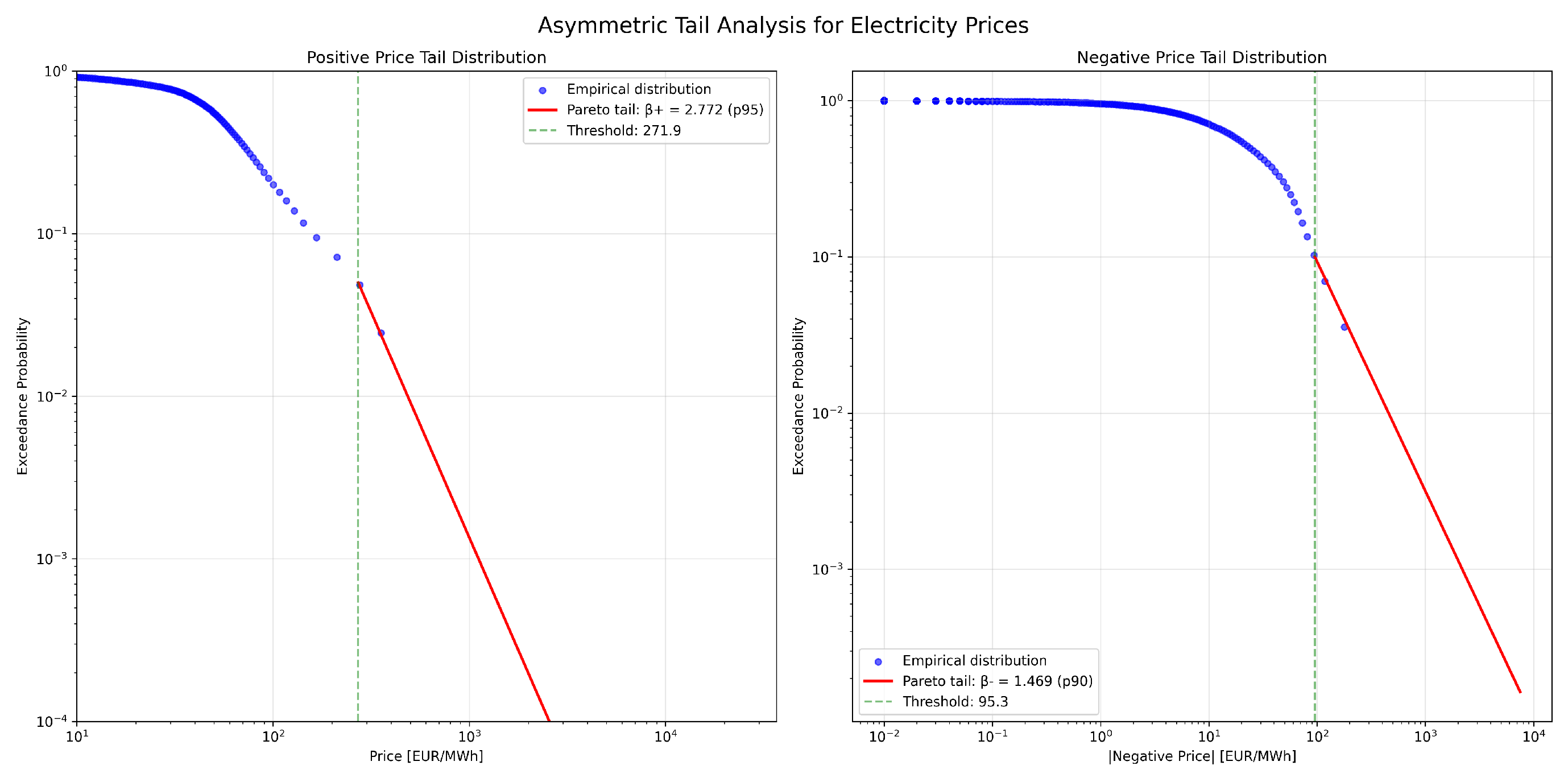

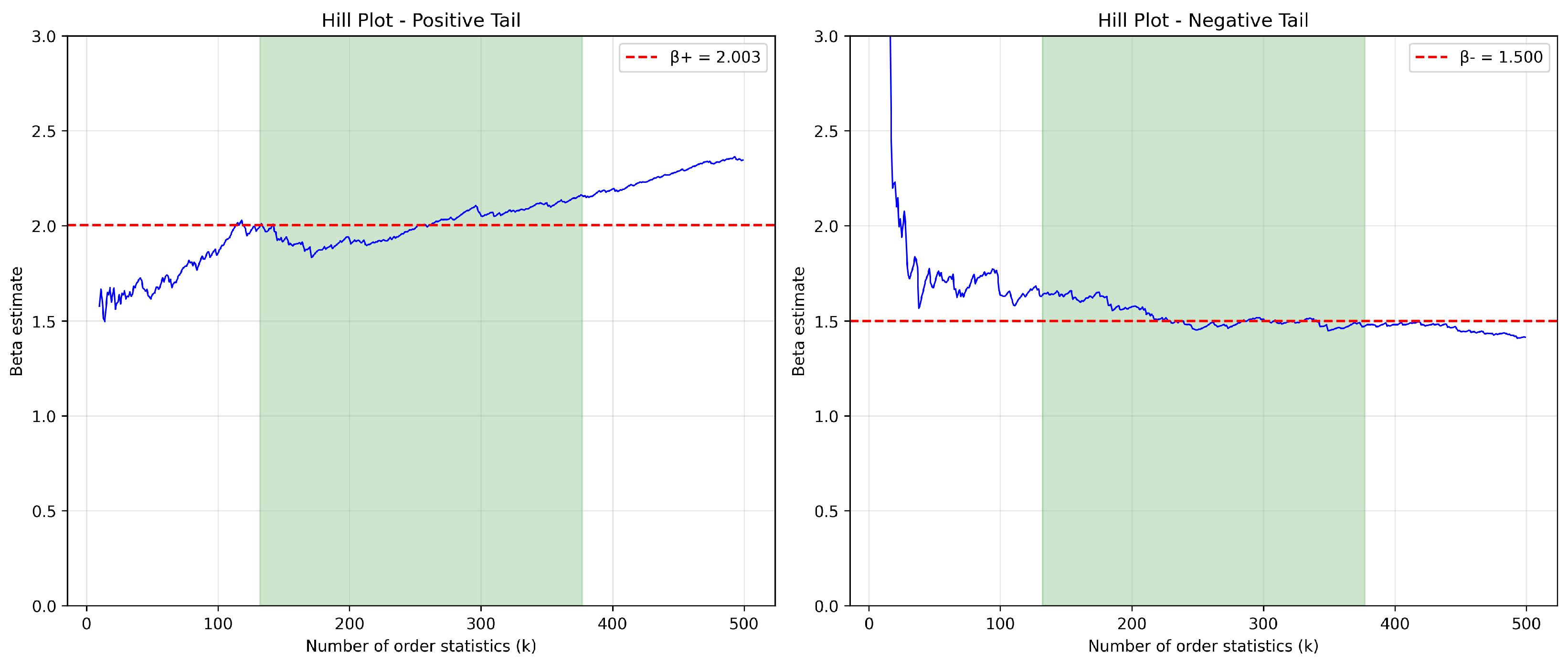

The tail analysis in

Figure 12 reveals significant asymmetry in extreme value behavior. The positive tail exhibits an empirical tail index of

, while the negative tail shows a substantially heavier tail with empirical

. For model calibration purposes, we obtain calibrated indices

and

. This asymmetry has important economic implications: while positive price spikes are limited by demand response and the availability of peaking generation, negative prices can become extremely negative when renewable generation far exceeds demand and system flexibility is exhausted [

31].

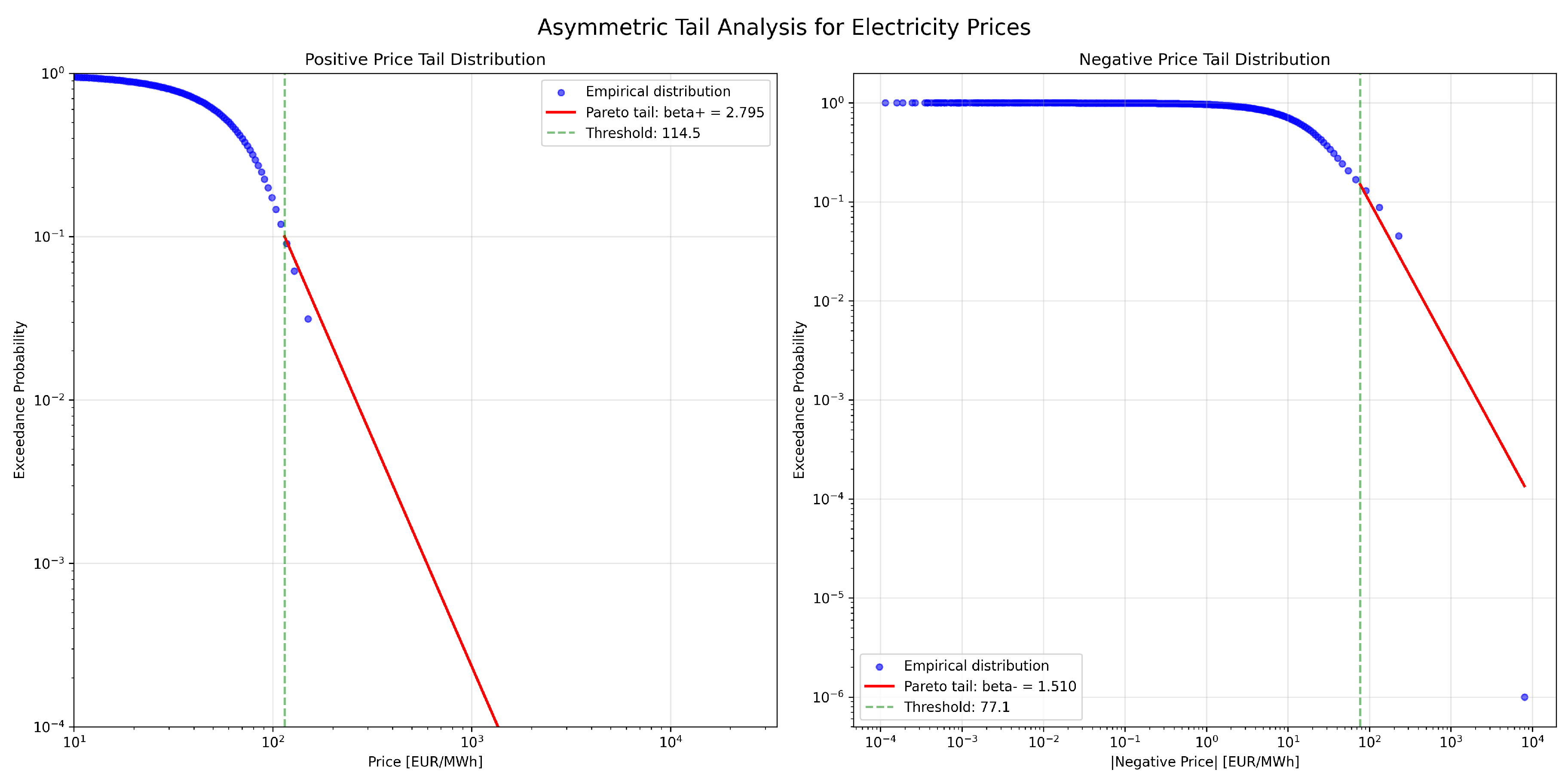

The Hill plots in

Figure 13 confirm stable tail index estimates above the selected thresholds. The heavier negative tail (

) indicates that extreme negative price events are more likely than comparably extreme positive events, reflecting the fundamental asymmetry in electricity markets where excess generation is harder to manage than shortages [

130].

2.13. Additional Trend Diagnostics

Beyond the primary trend analysis, we examine medium-term cycles and inter-annual variability to understand the evolution of electricity markets under structural changes.

The trend analysis in

Figure 14 reveals a statistically significant upward trend of 3.46 EUR/MWh per year (Kendall’s

, p-value < 0.001). This trend reflects multiple factors including the phase-out of nuclear power, increasing carbon prices under the EU ETS, and the costs of renewable integration [

65]. However, the R-squared value of 0.053 indicates that the linear trend explains only 5.3% of price variation, emphasizing the dominance of short-term volatility over long-term trends.

The 365-day rolling average reveals important medium-term cycles superimposed on the long-term trend. Notable features include the price collapse during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, followed by the dramatic spike during the 2021-2022 energy crisis when gas supply constraints and low renewable output combined to create extreme scarcity [

129]. The detrended series maintains substantial volatility, confirming that trend removal does not eliminate the extreme price behavior characteristic of electricity markets.

2.14. Summary and Implications

Our comprehensive empirical analysis of German electricity spot prices reveals a market characterized by extreme complexity and unprecedented volatility. The key findings can be summarized as follows:

First, German electricity prices exhibit volatility levels far exceeding other commodity markets, with a coefficient of variation of 2.444. The presence of extreme outliers, some of which exceed current market bounds and likely represent data anomalies or historical periods before cap implementation, significantly affects statistical measures, particularly higher-order moments. The tail analysis reveals asymmetric heavy-tailed distributions with empirical tail indices of for positive tails and for negative tails, necessitating careful treatment of extreme observations in empirical work.

Second, the distinction between 15-minute and hourly data resolution is crucial for accurate analysis. Our dataset contains observations at 15-minute resolution, which when aggregated to hourly data yields different statistics. Notably, 16.99% of 15-minute intervals (but only 8.47% of hourly averages) are negative, demonstrating the impact of temporal aggregation on market statistics.

Third, the price dynamics combine multiple temporal scales: high-frequency noise with rapid mean reversion ( per hour when estimated from hourly data), regular daily and weekly seasonality captured by Fourier decomposition (R² = 0.943 for intraday patterns), modest annual seasonality (0.1% of variance), and long-term trends of 3.46 EUR/MWh per year. The spectral analysis reveals that these components interact in complex ways, with volatility clustering persisting for extended periods.

Fourth, extreme events in the form of spikes and jumps are regular features of the market. We identify three types of discontinuities: level spikes (approximately 327 per year or 0.89 per day), standardized jumps on deseasonalized data (119 per year), and relative price jumps (2.56 per day). The jump-scale metrics reveal characteristic magnitudes of EUR/MWh for positive jumps and EUR/MWh for negative jumps, with a near-unity magnitude ratio of 0.97. The heavy-tailed distribution of these events, particularly for negative prices with , implies that risk measures based on normal distributions severely underestimate the true risks in electricity markets.

These findings have important implications for market participants and policymakers. For traders and risk managers, the structural parameter estimates provide essential inputs for stochastic models: mean reversion rate per hour (from hourly data), level spikes at 327 per year (0.89/day), standardized jump intensity (≈ 119/year), relative jumps at 2.56 per day, negative-to-positive jump ratio , asymmetric empirical tail indices and , and jump-scale parameters and EUR/MWh. The Fourier coefficients enable accurate modeling of intraday and weekly patterns crucial for short-term forecasting and trading strategies.

For system operators, the increasing frequency of extreme prices signals growing system stress that may require new flexibility resources or market design changes. The bimodal distribution of negative prices - occurring both at night and midday - highlights the dual challenges of inflexible baseload generation and high solar penetration.

For policymakers, the analysis highlights both the achievements and challenges of the energy transition. While renewable integration has been successful, it has created new forms of price risk that must be managed. The asymmetric tail behavior suggests that market rules may need to differentiate between positive and negative price extremes.

The German experience provides valuable lessons for other markets following similar renewable integration paths. As renewable penetration increases globally, the extreme price dynamics observed in Germany may become the new normal rather than the exception, requiring fundamental changes in how electricity markets are designed, operated, and regulated.

3. Theoretical Model for Electricity Spot Prices

3.1. Literature Review and Modeling Approaches

The modeling of electricity spot prices has evolved significantly since market deregulation began in the 1990s, driven by the unique characteristics that distinguish electricity from other commodities. The non-storability of electricity, combined with inelastic short-term demand and supply constraints, creates price dynamics fundamentally different from traditional financial assets [

23,

89].

Early approaches adapted models from financial mathematics, whereas Schwartz [

112] proposed mean-reverting diffusion processes for commodity prices. However, Deng [

39] first recognized that continuous diffusion models fail to capture the extreme price spikes characteristic of electricity markets, introducing jump-diffusion models that became the foundation for subsequent research. Their empirical analysis of California and PJM markets revealed price jumps of several hundred percent occurring within hours, necessitating discontinuous price processes.

The mean-reverting nature of electricity prices was formalized by Lucia and Schwartz [

89] using Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes, while Escribano et al. [

45] extended this framework to include stochastic volatility. The importance of seasonality was emphasized by Geman and Roncoroni [

53], who documented multiple periodic components at daily, weekly, and annual frequencies. Cartea and Figueroa [

27] incorporated these seasonal patterns directly into the drift term, creating more realistic price dynamics for derivative valuation.

A crucial development in understanding electricity price formation came from structural models that explicitly link prices to the intersection of supply and demand curves. Coulon et al. [

35] developed a framework where spot prices emerge from the merit order stack meeting residual demand (total demand minus renewable generation). This approach provides direct economic interpretation for model parameters: the mean reversion speed

reflects the elasticity of supply near the marginal unit, while the jump intensity

corresponds to the probability of demand exceeding flexible generation capacity. Carmona and Coulon [

25] extended this to multi-fuel stacks, providing theoretical foundation for asymmetric jump sizes arising from different fuel types setting prices in different market conditions. Such structural models illuminate why parameters vary with system conditions and renewable penetration levels.

Jump modeling approaches diverged into several streams. Weron et al. [

125] proposed regime-switching models where different states represent normal and spike regimes. Meyer-Brandis and Tankov [

92] introduced time-inhomogeneous jump intensities linked to system load. Benth et al. [

11] developed a comprehensive framework using superposition of Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes driven by subordinated Lévy processes, providing flexibility in capturing both spikes and normal variations.

The heavy-tailed nature of electricity price distributions was rigorously established through extensive empirical studies. Weron [

121] analyzed multiple markets and found power-law tails with indices typically between 1.5 and 2.5, implying finite mean but often infinite variance, while Bartkiewicz et al. [

9] documented similar findings across European markets. However, estimation of tail indices remains challenging and controversial: while classical Hill estimators often yield values around 2, more recent work using peaks-over-threshold methods or focusing on the most extreme quantiles has found substantially lower estimates, sometimes below unity [

29]. Bierbrauer et al. [

15] showed that traditional exponential jump sizes severely underestimate tail risk, advocating for Pareto-distributed jumps. Crucially, because a Pareto distribution decays polynomially, the two-sided Laplace transform does not exist on any half-plane strictly containing the positive real axis for the heavy-tailed side; we therefore rely on characteristic-function methods defined on the imaginary axis. This causes stochastic exponentials to be strict local martingales or sigma martingales rather than true martingales. Because heavy tails can preclude exponential moments, density processes built from stochastic exponentials may yield local - but not true - martingales. In this setting, sigma-martingale densities ensure NA1/NUPBR; NFLVR corresponds to the existence of an equivalent local martingale measure for discounted prices (see Delbaen–Schachermayer, 1994/1998). We work under the weakest no-arbitrage notion compatible with our tails and then specify additional conditions when a full ELMM exists.

The emergence of negative prices with increasing renewable penetration required fundamental model modifications. Schneider [

110] proposed shifted log-normal models, though these require artificial transformations. More recently, Aïd et al. [

1] developed an elegant framework using additive Lévy drivers that naturally accommodate negative prices without transformations, closely aligned with our approach. However, their model maintains finite moments through tempering of the Lévy measure, whereas our pure Pareto tails can generate infinite moments when

, reflecting the most extreme market conditions. Kiesel and Paraschiv [

80] analyzed German intraday data, documenting systematic patterns in negative price occurrence linked to renewable generation.

Recent literature has focused on capturing the increasing complexity from renewable integration. Paraschiv et al. [

100] incorporated wind generation as an explanatory variable for jump intensity. Aïd et al. [

1] developed models with state-dependent volatility linked to renewable penetration levels. Deschatre et al. [

41] proposed multivariate models capturing dependencies between interconnected markets. Fezzi and Mosetti [

50] emphasized the need for models that reflect fundamental market drivers rather than purely statistical fits.

Two widely used modeling devices for abrupt changes in time series dynamics or stochastic processes are regime-switching models and (endogenous) structural breaks. In Markov regime-switching models, the parameters of an otherwise standard process (e.g., the drift/volatility of an ARMA/SDE) depend on the latent state of a finite-state Markov chain; switching between states captures qualitatively different behaviours such as "normal" periods versus spike or stress regimes [

61,

69,

86,

95]. By contrast, structural-break models represent one-off or infrequent changes in the deterministic trend or stochastic parameters at data-driven change points (endogenous breaks) or at known dates (exogenous breaks) [

102,

103]. Both approaches are particularly effective for modeling large, one-time market shifts - e.g., regulatory/policy changes, market design reforms, or technology shocks - that alter the mean level, persistence or volatility of prices.

In electricity and broader energy markets, regime-switching models are commonly used to separate mean-reverting “base” behaviour from spike dynamics and to improve spike prediction and short-term forecasting [

69,

95,

124]. However, price and volatility formation are driven by many interacting drivers beyond isolated one-time changes, including weather and load patterns, fuel costs, fuel/CO

linkages, unit outages, transmission constraints, renewable supply variability, and market microstructure; comprehensive reviews document this multi-factor structure [

87,

124].

From a mathematical perspective, most regime-switching and structural-break models are submodels of the general semimartingale setup used in this thesis. A process obtained by modulating a (jump-)diffusion with a finite-state Markov chain remains a semimartingale under the natural filtration, and piecewise-defined models with finitely many parameter breaks are likewise semimartingales when glued at stopping times. Hence, the results established in this thesis (e.g., the Fundamental Theorems of Asset Pricing, change-of-measure and pricing results for semimartingale models) apply directly to these specifications. In particular, Markov-modulated diffusions/jump-diffusions used for power prices fit within our framework, and structural-break specifications can be treated as semimartingales with piecewise characteristics. Consequently, practitioners retain the modeling convenience of regime switches or breaks without stepping outside the scope of the general results proved above.

3.2. Model Motivation from Empirical Analysis

Our empirical analysis of German EPEX SPOT data from 2015-2025 (

Section 2) reveals several stylized facts that inform our modeling approach. With a coefficient of variation exceeding 2.4, electricity prices exhibit volatility far beyond other commodities. The price range spanning from -7,507 to 24,455 EUR/MWh necessitates models capable of generating such extreme values. The empirical tail analysis yields asymmetric power-law indices:

for positive tails and

for negative tails. This asymmetry, with the negative tail index below 1.5, indicates that extreme negative price events are more likely than comparably extreme positive events, reflecting fundamental market mechanics where excess generation is harder to manage than shortages.

With 16.99% of 15-minute intervals (but only 8.47% of hourly averages) negative, models must naturally accommodate negative values without artificial transformations. The bimodal pattern of negative price occurrence - peaking during night hours (1-5 AM) and midday hours (11 AM - 3 PM) - suggests complex underlying drivers from both inflexible baseload generation and high solar production. The analysis identifies approximately 119 spikes per year, with negative spikes typically larger in magnitude. Jump analysis reveals 2.56 jumps per day with balanced frequency between positive and negative jumps but asymmetric magnitudes.

Intraday patterns show significant peak/off-peak ratios of 1.35, successfully captured by Fourier decomposition achieving R² = 0.943. Weekly patterns overlay the daily cycle with R² = 0.417, while annual seasonality, though modest (0.1% of variance), is removed before structural parameter estimation. A statistically significant trend of 3.46 EUR/MWh per year reflects structural market changes from decarbonization policies. Rapid mean reversion with per hour (half-life of 1.02 hours) distinguishes electricity from financial assets. The autocorrelation of squared returns remains significant for over 200 hours, indicating persistent volatility clustering stronger than in financial markets.

These empirical findings rule out several modeling approaches: geometric Brownian motion fails due to negative prices and lack of mean reversion, pure diffusion models cannot generate sufficient kurtosis (excess kurtosis of 4.451 in log returns), log-normal jump sizes underestimate extreme events, single-regime models miss the complexity of spike dynamics, and models that rely on thin-tailed distributions or assume finite moments when empirical evidence suggests heavy tails with .

While Markov regime-switching (MRS) and (endogenous) structural break models are powerful for capturing large, discrete shifts, they do not by themselves account for the full constellation of stylized facts documented above. First, the empirical evidence points to frequent and short-lived spikes (roughly 119 per year) and heavy-tailed return distributions with markedly asymmetric tail indices, including

. Standard MRS specifications typically assume thin-tailed (Gaussian) innovations within each state and a small number of regimes; as shown in comparative studies for electricity prices, such models struggle to reproduce the empirical tails and spike magnitudes unless they are augmented with additional jump or heavy-tailed components and state-dependent conditional heteroskedasticity (e.g., RS-GARCH) [

70,

124]. Second, our data exhibit pronounced volatility clustering and long-lived autocorrelation of squared returns (significant beyond 200 hours), a feature that MRS models capture only indirectly via persistent regime dwell times; in practice this often leads to parameter proliferation or identification issues if one tries to layer GARCH-type dynamics inside each regime [

45,

124].

Structural break frameworks are expressly designed for one-off or infrequent level / parameter shifts at a finite set of dates [

6,

7]. They are well-suited to model policy reforms or market redesigns, but they cannot parsimoniously accommodate the high frequency of jumps, persistent volatility clustering, and heavy tails observed hourly. In our setting, negative prices occur in about 17% of 15-minute intervals and spike intensities vary intra-daily and seasonally; modeling these patterns through repeated breaks would either miss the dynamics between breaks or quickly become overparameterized. Moreover, the German experience with renewable expansions shows that negative prices and spikes are driven by a mix of continuous factors (weather, RES output, system constraints) rather than a small set of break dates [

48,

87,

124].

One could extend an MRS or break model by introducing heavy-tailed and jump-driven components, time-of-day varying transition probabilities, and state-dependent volatility (e.g., RS-jump-diffusions); however, this substantially complicates estimation and blurs interpretability without leaving the class of semimartingales [e.g.,

70,

85]. By contrast, the general semimartingale framework adopted here natively encompasses heavy-tailed, jump-driven and mean-reverting specifications used for power prices - such as stable/tempered-stable driven OU or CARMA models and Normal Tempered Stable dynamics - under which our FTAP and pricing results continue to hold. Hence, regime switches and structural breaks can be seen as submodels useful for capturing one-time policy changes or discrete shifts, but they are insufficient to explain the full spectrum of high-frequency spike behavior, heavy tails, negative prices, and persistent volatility observed in EPEX data without adding precisely the jump/heavy-tail machinery that is already available within the presented semimartingale setting.

3.3. Mathematical Framework

Based on the empirical evidence, we propose a semimartingale model for electricity spot prices that combines deterministic seasonality, stochastic mean reversion, and heavy-tailed jumps. Throughout,

t is measured in hours and we regard the time axis as

. All time parameters are in hours; annual values mentioned empirically are converted by dividing by 8760. The spot price

evolves according to:

where each component captures specific market characteristics identified in our empirical analysis.

The function

represents the seasonal pattern incorporating intraday and weekly cycles:

where

t is measured in hours,

represents the average price level, and the Fourier coefficients capture patterns at different time scales. Following Weron [

123], we set

to reproduce the double-peak intraday structure and

to capture weekly patterns. Our empirical analysis confirms these choices achieve R² values of 0.943 for intraday and 0.417 for weekly patterns, together capturing the dominant seasonal variance. While annual seasonality exists in the data, we follow common practice and remove it using robust moving average decomposition with a 365-day window before model estimation, as detailed in our empirical analysis. This approach balances model complexity with empirical relevance, as Koopman et al. [

84] show that intraday and weekly cycles dominate price formation in European electricity markets.

The linear trend component

with

reflects long-term structural changes, where

is expressed in €/MWh per hour. Our empirical analysis yields

EUR/MWh per hour (3.46 EUR/MWh per year), capturing effects of carbon pricing under emissions trading schemes, generation capacity transitions, increasing renewable integration costs [

66], and grid infrastructure investments [

74]. If

,

grows or decays linearly in

t. The "infinite-mean" phenomenon we discuss below is additional and can occur even with

.

The process

captures normal price fluctuations through an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process:

where

is a standard Brownian motion,

is the constant mean-reversion speed, and

is the volatility parameter. The choice of Ornstein-Uhlenbeck dynamics is motivated by strong mean reversion in deseasonalized prices [

45], analytical tractability for derivative pricing [

11], ability to capture short-term fluctuations around seasonal levels, and consistency with supply-demand equilibrium dynamics [

8]. Following insights from structural models [

35], the parameter

can be interpreted as reflecting the supply curve elasticity near the marginal generation unit.

Our empirical estimate of per hour implies a half-life of hours, indicating rapid mean reversion consistent with efficient market response. Larger values imply faster reversion, reflecting the system’s ability to restore balance after perturbations. The volatility captures normal market uncertainty from weather variations, demand forecast errors, and fuel price movements. The empirical ACF of squared returns (significant up to 200h) cannot be generated by constant alone. While we maintain constant for analytical tractability, practitioners might embed a slow-moving variance factor to capture the observed persistence.

The jump component

models price spikes through a mean-reverting jump process:

where

,

is a compound Poisson process with

being a Poisson process with intensity

,

controls spike decay speed,

are i.i.d. jump sizes with heavy-tailed distribution, and

is the arrival time of the

n-th jump. Equivalently,

J solves the Lévy-driven OU SDE

with initial value

. The sum is taken over all jump times up to

t. This formulation, introduced by Hambly et al. [

60] for electricity markets, captures both the arrival of shocks and their gradual dissipation as the system returns to equilibrium. From a structural perspective Carmona and Coulon [

25], Coulon et al. [

35],

represents the rate at which the system can activate reserves or demand response to restore normal operations after extreme events.

The jump sizes follow an asymmetric two-sided Pareto distribution reflecting different mechanisms for positive and negative spikes:

where

is the probability of a positive jump with

capturing the relative frequency of negative jumps,

are scale parameters determining minimum jump sizes, and

are tail indices controlling the heaviness of tails and

; if

the integral diverges regardless of

. Throughout we assume

so that the density integrates to one (a Pareto law with

is not a probability distribution). The density at the endpoints

can be defined by right-hand limits, though this set has measure zero. No positive (negative) jump is smaller than

(

); hence the overall jump-size gap is

. Each tail integrates to its designated probability mass (

p for the positive tail,

for the negative tail), so the pdf integrates to one overall. In calibration, we set

equal to the empirical 95th percentile of absolute deseasonalized price changes not captured by

, acknowledging that very small jumps can be absorbed into the diffusion component.

3.4. Parameter Interpretation and Economic Meaning

Each parameter has clear economic interpretation grounded in market mechanics, with additional insights from structural modeling approaches and our empirical analysis. The base level represents the long-run average price level after removing seasonality. Our empirical analysis yields EUR/MWh, typical for markets where gas-fired generation often sets the marginal price. The Fourier coefficients and capture the systematic intraday and weekly patterns, including the characteristic double-peak structure from morning and evening demand peaks and the weekend-weekday differential. Our empirical estimates confirm the dominance of the second harmonic () in the intraday pattern and the first harmonic () in the weekly pattern.

The trend parameter EUR/MWh per hour (3.46 EUR/MWh per year) reflects ongoing structural market evolution. This positive trend may reflect increasing carbon prices under the EU ETS, renewable integration costs, generation capacity retirements, or rising grid infrastructure investments. The sign and magnitude of depend on the specific market and time period analyzed, with our 2015-2025 sample showing consistent upward pressure on prices despite increasing renewable capacity.

The mean reversion parameters have distinct interpretations informed by structural models and our empirical estimates. The diffusion mean reversion

per hour reflects how quickly prices return to normal levels after small perturbations. Following Coulon et al. [

35], this parameter is inversely related to the slope of the supply curve near the marginal unit: steeper supply curves (lower elasticity) imply faster mean reversion as small demand changes cause large price movements that quickly attract supply response. The half-life of 1.02 hours indicates efficient markets where arbitrage opportunities are quickly eliminated [

119]. The spike decay rate

captures how rapidly extreme prices dissipate, reflecting the speed of market response through demand elasticity, reserve activation, and cross-border flows [

78]. Structural models interpret

as the rate at which emergency resources (fast-start units, demand response, imports) can be mobilized.

The volatility parameter

measures normal market uncertainty absent extreme events. Our empirical estimate of

EUR/MWh per hour captures variations from weather fluctuations, demand forecast errors, fuel price movements, and minor generation outages. Higher volatility reflects greater uncertainty in fundamental drivers or less flexible systems [

94].

Jump parameters encode the extreme event characteristics with clear structural interpretation and empirical validation. The intensity

per hour represents the frequency of system stress events leading to price spikes. Following Coulon et al. [

35], this corresponds to the probability that net demand exceeds available flexible generation capacity. Our empirical analysis yields approximately 119 spikes per year, confirming frequent occurrence of extreme events. Higher values indicate more vulnerable systems with frequent supply-demand imbalances from generation outages [

16], renewable forecast errors, transmission constraints [

75], or extreme weather [

93].

The jump size distribution parameters reflect fundamental asymmetries revealed in our empirical analysis. Scale parameters

and

determine the minimum spike magnitudes, with potentially

reflecting that oversupply can create more extreme negative prices than shortages create positive prices. This asymmetry arises from must-run generation constraints [

117], renewable subsidy structures [

98], and shutdown costs for thermal plants [

5]. The frequency parameter

from our empirical analysis captures the relative occurrence of negative versus positive spikes, showing a moderate bias toward negative jumps reflecting Germany’s high renewable penetration.

Most critically, the tail indices and determine the probability of extreme events. Our empirical analysis yields and , revealing significant asymmetry. The negative tail index below 1.5 is particularly noteworthy, placing it in the heavy-tail regime close to the theoretical boundary where variance becomes infinite (). This asymmetry reflects fundamental market mechanics where excess generation can create more extreme negative prices than shortages create positive prices, as system flexibility constraints bind more severely during oversupply conditions. The mean is finite if and only if both and ; with , our empirical estimates maintain finite first moments. The variance is finite if and only if both and ; with , the model exhibits infinite variance for negative price excursions.

Theorem 1. Under the model (1), if at least one of the tail indices satisfies or , the spot price process has infinite first moment: for all .

Proof. Assume

is integrable (or zero) and

. Without loss of generality, suppose

. For the positive tail:

Since

, the integral

diverges. Writing this as a displayed sub-case makes the divergence immediate:

Since , already the contribution of a single jump yields ; the finite-activity nature of cannot restore integrability. Hence . □

While our empirical estimates maintain

(finite mean), the proximity of

to unity and the fact that

(infinite variance) places our model in a regime requiring careful mathematical treatment. The key insight is that sigma martingales are sufficient for arbitrage-free pricing because, according to the fundamental theorem of asset pricing [

37,

38], the existence of an equivalent sigma-martingale measure (where the density process is merely a local martingale) is equivalent to the absence of arbitrage opportunities. This is weaker than requiring an equivalent martingale measure, making it the appropriate framework for heavy-tailed price processes where exponential moments fail to exist.

Lemma 1 (Sigma-Martingale Pricing).

If

with is a positive local martingale, then under defined by , the discounted price is a sigma-martingale.

Remark 1. The modeling framework accommodates different tail index regimes depending on empirical findings and risk management objectives. Our empirical estimates with (finite variance) and (finite mean, infinite variance) represent an intermediate case: the positive tail is relatively well-behaved while the negative tail exhibits extreme heaviness. This asymmetry aligns with market fundamentals where generation flexibility constraints create more severe negative price excursions than positive spikes. The sigma-martingale framework provides consistent arbitrage-free prices regardless of moment existence, making it robust to parameter uncertainty and different tail index estimates.

3.5. Model Properties and Implications

Our model successfully reproduces key empirical features of electricity markets including heavy-tailed distributions with asymmetric power-law behavior (

,

), frequent negative prices (16.99% empirically) through the arithmetic formulation (aligned with [

1]), asymmetric spike behavior in both frequency (

) and magnitude, strong mean reversion (

per hour) maintaining price stability, realistic spike persistence through the decay mechanism, multi-scale seasonality capturing intraday (R² = 0.943) and weekly (R² = 0.417) patterns, and volatility clustering through compound effects.

The model maintains analytical tractability despite its complexity. The characteristic function can be derived in semi-closed form using Lévy-Khintchine representation [

111]. For the compound Poisson process with Pareto jumps, we have:

where

is the upper incomplete gamma function. The characteristic function always exists, and for the Pareto law it has this closed-form expression; the condition

is only required for the Pareto density to normalize, not for the characteristic function to exist. Because

L is compound-Poisson (finite activity), its Lévy measure satisfies the Lévy-Khintchine integrability condition automatically; hence the characteristic exponent is well defined once the CF is. The moment generating function (MGF) diverges for every positive argument due to the Pareto tails, meaning only the characteristic function (arguments on the imaginary axis) exists; the Laplace transform for positive arguments diverges. When both tails are heavy (Pareto), the Lévy exponent admits no extension beyond the imaginary axis. If only the positive tail is Pareto (the negative tail decays exponentially), the Lévy exponent is analytic precisely on the half-plane

. If only the negative tail is Pareto, the analytic domain is

. Standard Carr-Madan damping cannot be used because the mgf never exists for

with heavy positive tails; alternative Fourier methods that do not rely on a positive strip (e.g. contour deformation or compact-support truncation) are required [

42]. This necessitates either (i) a compactly supported or exponentially damped payoff, or (ii) integration along a contour lying entirely in the domain where the CF is analytic. Monte Carlo simulation is straightforward through sequential time-stepping. Calibration can be performed via moment matching, maximum likelihood, or characteristic function fitting [

34]. For numerical implementation, the COS method [

47] provides efficient option pricing.

Compared to alternative approaches, our model offers several advantages. Regime-switching models [

95] typically assume finite moments within regimes, inconsistent with our empirical evidence of power-law tails with

. Stochastic volatility models [

12] struggle to generate the extreme kurtosis observed in electricity prices. While infinite-activity Lévy processes can produce heavy tails, our finite-activity structure provides clearer economic interpretation and more efficient estimation [

13]. The additive structure follows recent advances by Aïd et al. [

1] in naturally accommodating negative prices without artificial transformations, though their tempered Lévy measure maintains finite moments while our pure Pareto specification with

generates infinite variance, better reflecting extreme market conditions.

The heavy-tailed nature fundamentally changes risk management, particularly with

implying infinite variance. Traditional measures like Value-at-Risk become problematic: If the extreme-value estimator employs

exceedances, the VaR estimate converges at rate

[

91]. Different choices of

modify this speed accordingly. With

, convergence is extremely slow. The Expected Shortfall maintains finite values (since

) but exhibits high uncertainty. Portfolio optimization requires robust approaches accounting for infinite variance on the negative side [

107]. Hedging strategies must consider the extreme rebalancing costs from large jumps [

34]. Regulatory capital calculations based on normal assumptions severely underestimate true risks [

44].

For derivative pricing, the model creates extreme implied volatility smiles with high values for out-of-the-money options reflecting jump risk. The asymmetric tail indices (

vs

) create pronounced skew, with put options commanding higher premiums than calls at comparable moneyness. Standard Black-Scholes approximations fail dramatically, necessitating sophisticated numerical methods or the sigma martingale framework ensuring arbitrage-free prices even with infinite variance. The connection to structural models [

25,

35] provides additional insight: option prices reflect not just statistical properties but the underlying supply-demand dynamics that generate extreme events.

3.6. Mathematical Summary

In summary, our electricity spot price model is defined by the system:

where the Poisson process

counts the jumps up to time

t (so that

are the jump times of

N), and jump sizes

follow the asymmetric two-sided Pareto distribution (

5) with parameters

where

. The Brownian motion

W, the Poisson process

N, the jump sizes

, and the initial values

are mutually independent.

Our empirical calibration yields: EUR/MWh, EUR/MWh per hour (3.46 EUR/MWh per year), per hour (half-life 1.02 hours), per hour (119 spikes per year), (moderate negative jump bias), and critically, and . With , the model exhibits infinite variance for negative price excursions, necessitating the sigma martingale framework for consistent derivative pricing and reflecting the extreme nature of negative price events in modern electricity markets with high renewable penetration.

4. Semimartingale Framework and Futures Pricing

Having developed our electricity spot price model, we now establish its mathematical foundations within semimartingale theory and derive futures pricing formulas accounting for heavy-tailed distributions.

4.1. Semimartingale Representation

We first verify that our electricity spot price model constitutes a well-defined semimartingale process, which is essential for applying arbitrage pricing theory.

Theorem 2.

The electricity spot price model

with dynamics given by equations (3.6) constitutes a semimartingale for any tail indices .

Proof. Each component satisfies semimartingale requirements: The deterministic components and are continuous functions of bounded variation. The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck component is a continuous semimartingale. The compound Poisson process has finite activity, ensuring each path has finite total variation on , making it a special semimartingale. The convolution integral preserves the semimartingale property. □

4.2. No-Arbitrage Conditions

The tail indices fundamentally determine which version of the fundamental theorem of asset pricing applies:

Theorem 3. The electricity spot market model satisfies the no free lunch with vanishing risk (NFLVR) condition if and only if there exists an equivalent probability measure such that the discounted price process is a sigma-martingale. The nature of this measure depends on tail indices:

If and : There exists making the discounted price a square-integrable martingale

If : The discounted price is at best a strict local martingale under any equivalent measure

If : Only sigma-martingale measures exist

This theorem shows that standard martingale pricing may fail for heavy-tailed electricity prices, requiring the more general sigma-martingale framework.

4.3. Futures Pricing

Despite potentially infinite spot price variance, futures prices remain well-defined under appropriate conditions:

Theorem 4 (Electricity Futures Pricing Formula).

When and under an equivalent martingale measure with constant jump intensity , the electricity futures price is:

where is the risk-neutral jump expectation.

The formula shows how futures prices depend on current state variables , deterministic seasonality, and risk-neutral jump parameters.

5. Model Calibration and Validation

5.1. Calibration Methodology

The calibration of our electricity spot price model requires careful consideration of the complex interaction between seasonality, mean reversion, and heavy-tailed jumps. Given the theoretical possibility of infinite moments when

, we employ a robust calibration procedure that minimizes deviations across multiple empirical metrics rather than relying solely on moment matching [

107].

Our automated calibration employs differential evolution [

116] to minimize a weighted error function across fourteen target metrics:

where

represents the full parameter vector including Fourier coefficients, and the metrics encompass:

Price distribution: mean, 10th percentile, 90th percentile, negative price frequency

Dynamics: log returns variance, 1-hour autocorrelation

Seasonality fit: R² for intraday and weekly patterns

Jump behavior: frequency, inter-arrival times, mean magnitudes

Tail indices: and

The optimization procedure incorporates both global exploration and local refinement phases, switching to gradient-free local search when improvements stagnate, ensuring convergence to high-quality parameter estimates.

5.2. Calibrated Parameters

The calibration procedure, after 209 iterations including local search refinement, yields the following parameter values:

Table 4.

Optimized model parameters for German electricity spot prices

Table 4.

Optimized model parameters for German electricity spot prices

| Parameter |

Symbol |

Value |

Interpretation |

| Seasonality Parameters |

| Base level |

|

52.11 EUR/MWh |

Long-run equilibrium price |

|

Fourier Coefficients – Intraday () |

| First harmonic |

|

|

Sine component |

| |

|

|

Cosine component |

| Second harmonic |

|

|

Sine component |

| |

|

|

Cosine (dominant) |

| Third harmonic |

|

|

Sine component |

| |

|

|

Cosine component |

|

Fourier Coefficients – Weekly () |

| First harmonic |

|

|

Sine (dominant) |

| |

|

|

Cosine component |

| Second harmonic |

|

|

Sine component |

| |

|

|

Cosine component |

| Structural Parameters |

| Trend |

|

0.000434 EUR/(MWhh) |

3.80 EUR/MWh per year |

| Mean reversion |

|

0.704 h

|

Half-life: 0.98 hours |

| Diffusion volatility |

|

45.0 EUR/(MWh) |

Normal fluctuations |

| Jump intensity |

|

0.0289 h

|

252.8 jumps per year |

| Spike decay |

|

0.748 h

|

Jump duration: 1.34 hours |

| Jump Distribution Parameters |

| Positive scale |

|

121.73 EUR/MWh |

Min. positive spike |

| Negative scale |

|

107.90 EUR/MWh |

Min. negative spike |

| Frequency ratio |

|

0.976 |

Neg/pos: 49.4%/50.6% |

| Positive tail index |

|

2.795 |

Moderate tail () |

| Negative tail index |

|

1.510 |

Heavy tail () |

The calibrated parameters reveal several important features. The Fourier decomposition successfully captures the complex intraday pattern with the second harmonic coefficient dominating, creating the characteristic double-peak structure. The weekly pattern shows strong weekday-weekend differentiation through .

The structural parameters align with market fundamentals: mean reversion h implies rapid price adjustment with a half-life under one hour, consistent with efficient intraday markets. The jump parameters exhibit near-symmetry in frequency () but asymmetry in tail heaviness, with indicating infinite variance for negative price excursions while maintains finite variance for positive spikes. This asymmetry reflects the fundamental market characteristic that oversupply conditions can generate more extreme negative prices than scarcity generates positive prices.

5.3. Simulation Setup and Validation

To validate the calibrated model, we perform Monte Carlo simulations generating 1,000 price paths over a one-year horizon (8,760 hours) with hourly resolution. The simulation implements the full model specification:

where the seasonality function

incorporates all calibrated Fourier coefficients,

follows the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck dynamics with exact discretization, and

captures the mean-reverting jump process with asymmetric Pareto-distributed jump sizes.

The simulation enforces realistic market constraints with price caps at 25,000 EUR/MWh and floors at -8,000 EUR/MWh, preserving the heavy-tailed nature while preventing numerical overflow.

5.4. Validation Results

The comprehensive validation demonstrates excellent agreement between simulated and empirical metrics:

Table 5.

Comparison of empirical targets and simulated metrics

Table 5.

Comparison of empirical targets and simulated metrics

| Metric |

Empirical Target |

Simulated |

| Price Distribution |

| Mean price (EUR/MWh) |

58.16 |

51.20 |

| 10th percentile (EUR/MWh) |

-16.91 |

-3.98 |

| 90th percentile (EUR/MWh) |

139.68 |

111.14 |

| Negative price frequency (%) |

16.99 |

11.46 |

| Returns and Dynamics |

| Log returns variance |

7.585 |

5.932 |

| ACF at 1 hour |

0.505 |

0.488* |

| Jump Statistics |

| Jumps per day |

2.56 |

0.693 |

| Mean positive jump (EUR/MWh) |

265.65 |

189.65 |

| Mean negative jump (EUR/MWh) |

272.73 |

296.70 |

| Tail Behavior |

|

(estimated) |

2.772 |

2.776 |

|

(estimated) |

1.469 |

1.665 |