1. Introduction

It is widely admitted that COVID-19 has engendered devastating consequences on worldwide economies (Maital and Barzani, 2020; Ahmad et al., 2020). The Nord Pool region has its part of the pie. As of October 1, 2020, Sweden reported 93,615 infections and 5,893 deaths from the COVID-19 epidemic, with 24 patients in intensive care. Sweden currently has fewer daily infections than Denmark, which has 27,998 infections and 650 deaths. Denmark has faced a second wave, with 678 new cases on September 25, exceeding the March peak, a reproduction rate over 1 (1.5 in Copenhagen), and a test positivity rate of 1% at month-end (compared to 0.1% in July). Norway reported 13,914 infections and 274 deaths by September 30, with no patients in intensive care. Finland had 9,992 cases, 344 deaths, and 4 patients in intensive care. The infection rate in Finland over the last fourteen days was the lowest in the Nordic countries, at around 20.4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Latvia recorded 843,070 cases and 5,862 deaths, while Estonia recorded 582,867 cases and 2,608 deaths (High Council of Public Health). Governments have assisted people with healthcare emergency programs, including isolation of infected people, social distancing, postponing events, and deleting all types of gatherings. One can wonder whether pandemic-related variables such as confirmed cases, mortalities, and government policies shaped the electricity market in the Nord Pool countries. If so, a pronounced impact on those markets should be observed when governments intervene to limit the spread of the virus. These features are relevant to the electricity market, distinguishing our study from others in its analysis of electricity price dynamics. As a consequence of the pandemic, changes in social behavior are detected. This includes a considerable reduction in electricity consumption and demand (Mastropietro et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2022a). With the arrival of the epidemic, the supply of electricity is also warranted with a higher emphasis and interest on energy policy. The development of renewable energy has shown the importance of wind energy specifically in the Nord Pool region (Pointel, 2016; Unger et al., 2018). Apart from being less expensive compared to other energy source such as nuclear power, it is widely acknowledged that wind energy is environment-friendly (Mertens, 2005; Nelson, 2009; Wang & Wang, 2015; Saidur et al., 2016; Solarin & Bello, 2022).

This study aims to investigate the role of COVID-19 news, containment, lockdown restrictions, economic support, and WEP in Local Electricity Prices (LEP) within the Nord Pool region. Prices can help individuals and businesses adjust for electricity consumption (Lindberg, 2023). Moreover, by including wind energy, we put the merit-order effect under test in the short and long run. While a plethora of studies have explored the merit-order effect in various countries, literature is scarce on this phenomenon in the Nord Pool region, particularly in the context of the extensive impact of COVID-19.

The salient feature of this paper is to emphasize the role of governments in terms of energy demand/supply and limiting the spread of the virus. Beyond addressing immediate public health concerns, this study emphasizes the broader responsibility of policymakers in managing energy use sustainably and fostering awareness of the environmental implications of shifting consumption patterns. The pandemic has altered energy demand dynamics, with some consumers adapting their behavior in response to evolving economic and social conditions. The novelty of the paper is, thus, to include specific COVID-19 and government intervention metrics. In examining the relationship between WEP and LEP, it is important to advance knowledge about inform policy. We argue that WEP can be a pathway for abating environmental degradation and is considered a clean energy. Meanwhile, there is a variation in how countries’ governments mobilize citizens and markets regulators to administer rules, thereby affecting the effectiveness of these rules. Compliance with the government’s restrictions is assessed through the degree of attentiveness to news about infected people and mortalities. Incorporating the COVID-19 variables assesses the severity of the epidemic and provides an implicit hint to people’s reactions and social engagement. Multiple announcements about mobility restrictions and containment measures put the efficient use of information under test (see Angeletos & Pavan, 2007). On the other hand, channels through which information is disseminated pose challenges to their transmission mechanisms. In such a special event, factors that lead to government are particularly relevant (Funke et al., 2023). This includes trust in media, in scientists or investors’ sentiments such as fear, greed, love, and intrinsic instinct (Allcott et al., 2020; Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020; Malmendier & Nadler, 2011; Simonov et al., 2020; Webster et al., 2020). Another concern raised when assessing the variables of interest is the time window between the governments’ announcements and the effective implementation of lockdown restrictions, containment, and economic assistance (Funke et al., 2023). We believe that Panel ARDL modeling is suitable for that purpose on the grounds of a battery of tests visa.

The paper has the following layout. A comprehensive assessment of the literature is provided in

Section 2.

Section 3 covers material and method. The empirical findings are shown and discussed in

Section 4.

Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Electricity Markets’ Performance During COVID-19 and the Role of Government

The COVID-19 crisis has spurred governmental development policies to cope with its dramatic health as well as economic consequences. With the slowdown of economic activity, unusual movements in electricity operations and prices are noticed. Pradhan et al. (2021) argued that variations in wholesale electricity prices hinged on a lower market concentration and a cleaner environment policy. Similarly, Bigerna et al. (2022) cheered the role of competitiveness in hard times such as COVID-19. In the European region, Deloitte’s report (2020) and Graf et al. (2021) recognized a decline in demand in the electricity markets, especially driven by the lockdown restrictions (see Zhong et al., 2020; Santiago et al., 2021; González-López et al., 2022; Sánchez-López et al., 2022). Similarly, Leach et al. (2020) noticed a demand fallout in the electricity markets of Canadian provinces. Shifts in behavior and sentiments are also depicted under exogenous shocks (Szczygielski et al., 2022). Norouzi et al. (2020) found out that the announcement of confirmed and death cases causes fear and insecurity for investors, explaining the adverse effects of that news on energy prices in Spain. In the same vein, US electricity consumption fell because of infected people, social distancing restrictions, and business project records (Ruan et al., 2020).

Both high wind penetration and the merit of scientific advice from the government stabilized the electricity prices in Germany (Halbrügge et al., 2021). Investing in renewable energy sources is also recommended from an African landscape (see Akrofi & Antwi, 2020). While fiscal and financial measures undertaken by the governments are provisory in those countries, the pandemic has the premise of a clean energy transition with a long-lasting positive effect on the sector. Bidding on renewable energies made of a combination of regulatory structure and climate state should reinforce electricity supply security (Bento et al., 2021). The Brazilian government has intervened financially with a loan-based policy to alleviate the effects of COVID-19 on the electricity market, without achieving an immune system (Costa et al., 2021). In Ibero-America, the government assisted citizens with delays and reductions in bills prices. This economic aid does not, however, reach all social categories (Lazo et al., 2022). To sum up:

Wind is a leading electricity generation technology during COVID-19.

There is no clear, direct, and sufficient assessment of COVID-19 effects on electricity markets, making our contribution unique in this respect, at least, in the Nord Pool countries to the best of our knowledge. In addition to the health news, protective measurements by governments in those countries should be explicitly identified and quantified.

We need to draw policy implications of using renewable energy to ensure sustainable development.

2.2. The Effect of WEP on LEP

The WEP-LEP nexus has been thoroughly investigated in the literature. According to Woo et al. (2013), rising wind power in the US Pacific Northwest caused a brief but notable decline in the wholesale market pricing. Likewise, Rana & Ansari (2013) showed that WEP can affect power market pricing using a genetic algorithm and a single auction market model. De La Nieta et al. (2014) demonstrated using a price maker optimization model that wind power providers can reduce LEPs in the near term by taking part in the day-ahead market without getting any premiums or assistance. Interestingly, Ketterer (2014) found that while wind power lowers prices, it also raises volatility in the short term but will likely decrease the wholesale electricity prices in Germany by 2023.

A Monte Carlo study by Lynch and Curtis (2016) supported reduced production costs and less price volatility due to greater wind capacity. Zamani-Dehkordi et al. (2016) demonstrated that, in the short term, higher wind output lowers wholesale market prices by a marginal but economically significant amount. This observation is shared by Brancucci Martinez-Anido et al. (2016) and complemented by a rise in price volatility in the near term. Benhmad and Percebois (2016) demonstrated that increasing wind power contributes to lower levels of electricity spot prices but higher volatility. The WEP-LEP relationship is also sensitive to seasonal effects (Badyda & Dylik, 2017). Wirdemo (2017) and Makalska et al. (2018) asserted that higher WEP has a significant, especially short-term, impact on LEP volatility. Csereklyei et al. (2019) showed that daily and monthly impacts are substantial while short-term price swings in gasoline markets have minimal effect on LEPs in Germany. Veraart (2015), Pereira and Rodrigues (2015), Pineau et al. (2020), and Meng et al. (2021) contended that wind power causes downward prices.

Technological advancements in wind turbine efficiency have been outweighed by higher indirect costs associated with grid integration. In light of this, WEP has been a prominent catalyst of LEPs (see Ulm et al., 2020; Dorrell and Lee, 2021). Nonetheless, Doering et al. (2021) discovered that inadequacies in wind power generation systems, particularly in times of elevated electricity demand, resulted in increased US spot prices in both low- and high-price scenarios. During the dry season, higher wind generation increases price variation and decreases nodal prices (Wen et al., 2022b). While tracking changes in price levels and volatility, Ederer (2015) and Hosius et al. (2023) advocated for offshore over onshore wind energy.

2.3. The Short-Term and Long-Term Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy

Based on the studies in sub-section 2.2, the distinction between the short-term and long-term impact of wind energy is warranted, especially its role in sustainable development. In the short term, wind energy can reduce wholesale electricity prices by replacing more expensive generators, as identified by Hirth (2013). Such a situation breaks down to what is called the merit-order effect. This price reduction not only benefits consumers but also incentivizes a cleaner energy mix, aligning with global sustainability goals. De Miera et al. (2008), Azofra et al. (2014), and Escribano & Ortega (2021) recognized the presence of a merit-order effect triggered by increases in wind generation for the case of Spain. Similarly, Bell et al. (2017) noticed a decrease in the wholesale electricity prices in Australia due to high wind generation capacities by establishing different scenarios. Renewable energy sourced from wind power leads to lower electricity prices in Sweden with a stable daily merit-order effect (Macedo et al., 2021). Figueiredo & da Silva (2019) discussed rather the determinants of the merit-order effect in the Iberian electricity market and found that the effect is more pronounced with high penetration of both wind and solar power as well as with demand. Further empirical studies support the merit-order effect in other countries (e.g., Clò et al., 2015; Lopez et al., 2018; Acar et al., 2019).

Once the merit-order effect is evidenced, it is essential to account for the distributional effects in the policy design (see Sensfuß et al., 2008; De Miera et al., 2008; Cludius et al., 2015).

Yet, the long-term merit-order effect is more ambiguous (Borenstein and Bushnell, 2018). An intriguing and extensive contribution is made by Antweiler and Muesgen (2021) wherein they considered different situations. They developed a theoretical model and simulations were conducted to depict prices’ sensitivity to the share of renewable energy in Germany. The merit-order effect is undoubtfully identified in the short horizon, while such an effect arises only when Antweiler & Muesgen (2021) established a “monopolistic base load” scenario. Earlier work by Acemoglu & Kahhbod (2017) considered a setting with incomplete information and showed that the merit-order effect diminishes once they accounted for diversified electricity portfolios, a result that is already achieved by Green & Vasilakos (2011) using a dispatch model for Great Britain electricity market.

1

Except for Macedo et al. (2021) for the Swedish case, we do not record studies about the merit-order effect in the Nord Pool region. Further, no investigation about that phenomenon coupled with the COVID-19 impact has been done, distinguishing again our work from previous literature. Furthermore, Wind energy is a cornerstone of sustainable development by mitigating price volatility and decreasing reliance on fossil fuels. The expansion of wind power contributes to economic efficiency in electricity markets and supports global climate action by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These findings emphasize the necessity of policies that promote investment in renewable energy infrastructure, ensuring a resilient, low-carbon future.

3. Material and Method

3.1. Data

We gathered data on LEP in Euro and WEP in MWh from the Nord Pool database while the COVID-19 metrics were collected from Our World in Data (see

Table 1). The sample spans from 01/01/2020 until 31/12/2020 across seven countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) and 15 regions.

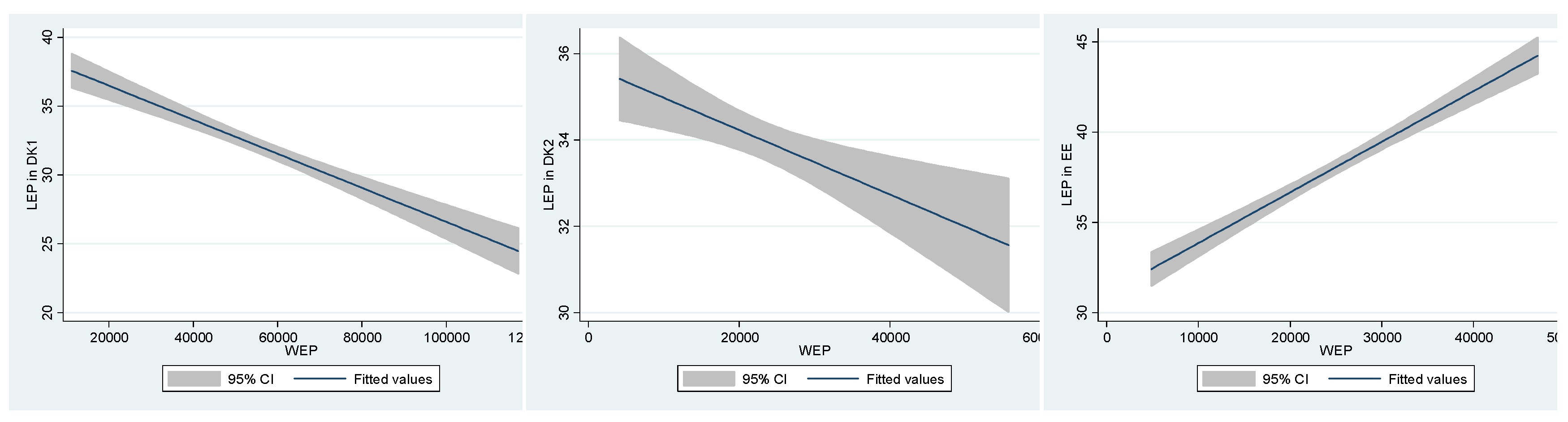

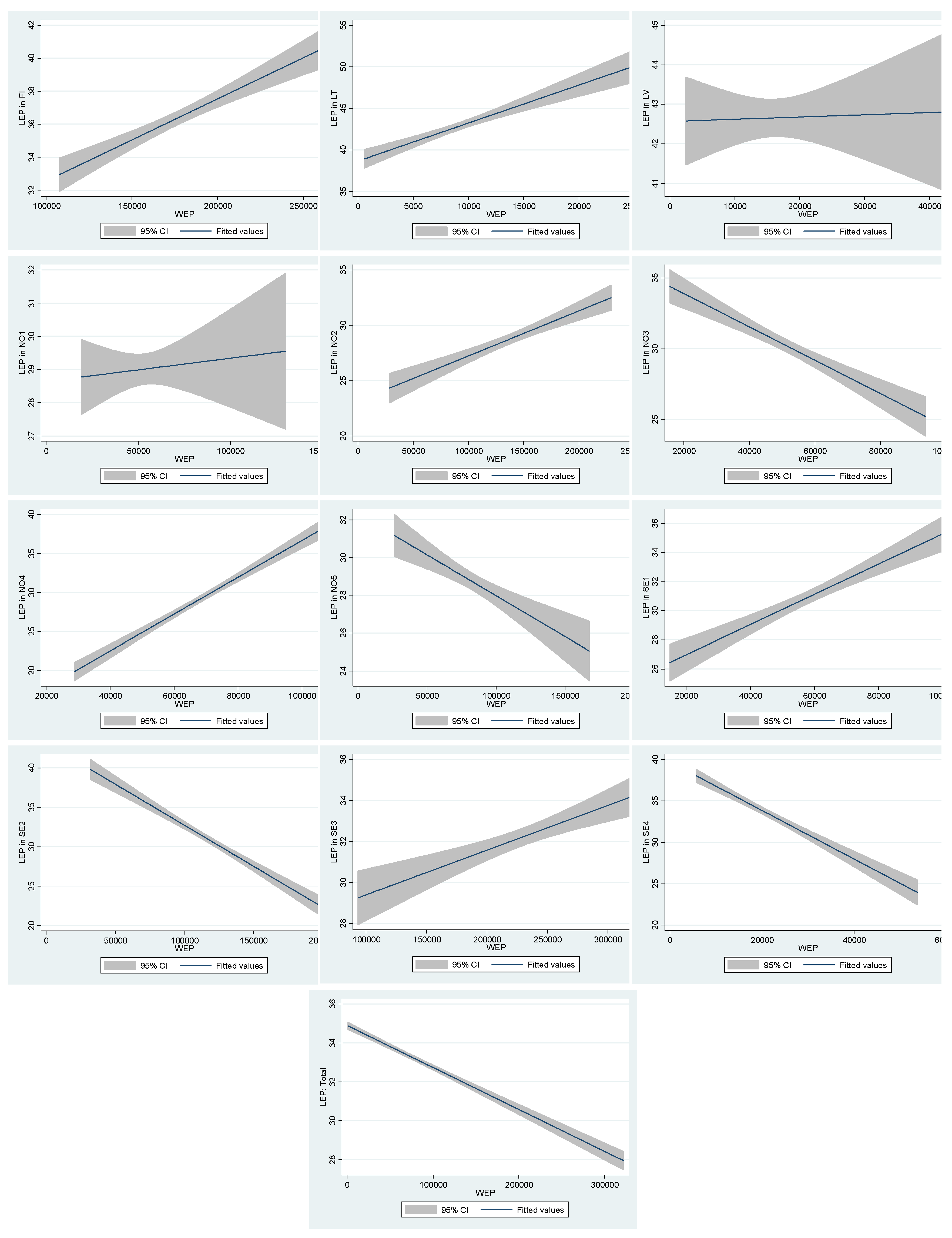

Figure 1 tracks the average effect of WEP on LEP by country and region. The horizontal axis stems from renewable energy sourced by wind production flow. The vertical axis pertains to electricity prices expressed in €/ MWh. The visual inspection of

Figure 1 indicates that five out of the 15 regions support the merit-order effect, that is an increase in WEP leads to lower levels of LEP. Taken all regions together, there is a downward pattern of LEP following the high flow of wind penetration.

3.2. Summary Statistics

In 2020, the mean of LEP is €20.34, with a €15.20 standard deviation and a €17.74 median (

Table 2). We also note a positively skewed distribution of prices. There are considerable price swings as the range of extreme boundaries is €-14.37 to €107.42. Data for WEP indicates a skewed distribution, with a mean and standard deviation of 75,944.61 MWh and 63,686.25 MWh, respectively. The production range of 2,431 MWh to 307,951 MWh indicates a significant disparity in the pandemic’s impact on government policy metrics. The CHI has an average of 40.01 with a standard deviation of 23.19, whereas the GSI has a mean of 43.50 with a standard deviation of 18.86. A mean of 43.26 and a standard deviation of 27.83 are reported for the EPI. The health situation is dominated by infected more than dead people (Mean of 8912.5 versus 255). Overall, WEP’s stability can be attributed to its renewable nature as well as stimulus initiatives designed to avert a financial disaster. Although government controlling measures shift energy demand, contracted markets, and incentive programs guarantee WEP’s resilience (Juergensen et al., 2020).

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients among the different variables and illustrates their relationships. The Government Stringency Index (GSI), Containment Health Index (CHI), and Economic Policy Index (EPI) are highly significantly and mutually correlated. Hence, we include these variables separately to avoid biased results.

WEP and LEP have a mild negative association (r = -0.231703), meaning that a change in one variable leads to a decline in the other variable. Conversely, there is a marginally positive weak connection (r = 0.146751) between CCC-19 and WEP. A small negative association (r = -0.102315) between GSI and LEP indicates that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, LEP somewhat decreased in response to stricter GSI. Viral containment strategies are shown to have no association LEP, with a negligible negative correlation with CHI and WEP (r = -0.008198). Finally, a positive correlation of r = 0.284449 between EPI and LEP indicates that a more accommodating economic policy results in the moderate rise in LEP.

It is noteworthy that the number of confirmed cases declines within seven days lag window (see Askitas et al., 2021). Simple panel regressions are not adequate for such analyses and distinguishing short/long-term impacts becomes appealing.

2

3.3. Preliminary Tests

3.3.1. Panel Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

The cross-section dependence test determines whether there is a correlation between the regions where LEP and WEP are measured.

Table 4 displays the results of three different cross-sectional dependence tests: the Breusch-Pagan LM test, the Pesaran scaled LM test, and the bias-corrected scaled LM test. For all of these tests, the null hypothesis assumes that there is no cross-sectional dependence between regions. LEP and WEP test statistics are presented, along with their accompanying p-values. In each case, the p-values are less than 0.05, rejecting the null hypothesis and confirming cross-sectional dependence.

3.3.2. The Second Generation of Panel Unit Root Tests

When data shows cross-sectional dependence, the second generation of panel unit root tests is applied (Bai, 2009; Moon et al., 2004; Pesaran, 2007).

Table 5 shows that certain variables have a unit root. Nonetheless, all variables reject the unit root at the first difference (refer to

Table 6). The Cross-sectional Augmented IPS (CIPS) test adds additional regressors to the IPS test, which was created by Im, Pesaran, and Shin (Im et al., 2003) and is based on the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test. The truncated CIPS (TCIPS) copes with panels with large cross-sectional units. Based on CIPS and TCIPS tests, LEP, WEP, GSI, CHI, and EPI reach stationarity in their first differences, minimizing the likelihood of erroneous regressions. The CCC-19 variable is I(1), and CCD-19 alternates between I(0) and I(1) using TCIPS with a constant and trend.

3.3.3. Panel ARDL Cointegration Test

Second-generation panel cointegration tests outperform the traditional first-generation tests of Pedroni (1999) and Kao (1999) in the presence of cross-sectional dependence. The Westerlund (2007) test employs the residual augmented least squares (RALS) estimator, which makes it more resistant to many types of cross-sectional dependence, including spatial correlation and common components. Westerlund and Edgerton (2008) proposed the Durbin Hausman group mean cointegration test, which is used in this work. This specialized test has significant advantages. It does not rely extensively on prior knowledge of the order of integration and can account for cross-sectional dependencies. Moreover, the test of Westerlund & Edgerton (2008) permits the distinction of stability ranking between explanatory factors. We, therefore use the Panel tests (Pt and Pa) and Group-mean tests (Gt and Ga) of Persyn et al. (2008).

P-values of the cointegration test indicate a long-term link between the variables (<0.01) (

Table 7). It is noteworthy that test robustness varies depending on the model and included variables. Among all models, the one that displays the GSI and WEP, for instance, has substantial statistical values, suggesting a very strong cointegration relationship. On the other hand, the WEP and EPI model exhibits somewhat weaker cointegration interactions. Overall, we establish that the variables throughout the COVID-19 period have long-term associations.

3.4. Econometric Strategy: Panel PMG ARDL

The study examines the speed of equilibrium return and the short- and long-term relationships between WEP and LEP using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model and the pooled mean group (PMG) estimator by Pesaran et al. (1999) (see Sohag et al., 2015; Osman et al., 2016; Wolde-Rufael & Weldemeskel, 2020). In the long run, the homogeneity restriction makes it reasonable for the study to focus on average elasticities across nations. We can express Eq.(1) as

where i = 1, 2,….., N stands for the cross-sectional unit (regions), t = 1, 2, 3, ….., T represents time (daily), and j is the number of time lag. is the vector of the explanatory variables, is the fixed effect, and is the error term.

The error correction form pertains to

where defines the long-run or equilibrium relationship among and . The parameters and are the short-run coefficients relating price to its past values and other determinants like . Δ is the lag operator. Finally, the error-correction coefficient measures the speed of adjustment of toward its long-run equilibrium following a change in . The condition < 0 ensures that a long-run relationship exists. In total, we have estimated five variants of Eq. (2).

4. Results

We rely on conventional information criteria such as Akaike to select the optimal lags for p and q in Equations (1)-(2).

4.1. Long-Run Results

According to

Table 8, The Nord pool countries have established healthcare emergency programs wherein vaccination campaigns, mask-wearing, and hand hygiene are reinforced, causing a decline in Gas House emissions and a better quality of water. This means that containment health measures (CHI) are a vehicle for enhancing the quality of the environment, resulting in lower electricity prices (Model 1). Interestingly, we have evidence that the governmental responses to the pandemic indexed through GSI, exert downward pressure on LEP (Model 2) — these stringencies, including movement restrictions and public space closures, lower economic activity, and energy demand. The reduced demand, coupled with a rise in renewable energy contributions, tends to exert a downward pressure on electricity prices. Model 3 depicts a significantly downward pattern in electricity prices following an increase in economic support by governments (ESI). With the economic downturn and the shutdown of commercial activity causing high energy costs, measures include a reduction in the cost of fuel for individuals and businesses, a flat-rate increase in social benefits for the most disadvantaged households, and particularly compensation for electricity bills for households.

The findings in Table 8 consistently indicate a substantial inverse relationship between WEP and LEP in the long run. Models 1-5 reveal that an increase in WEP leads to a decline from 0.0051% to 0.0091% in LEP. Our results align with previous studies such as Nieuwenhout & Brand (2011), Jaraite et al. (2019), and Pineau et al. (2020) despite different methodologies. Our observations contradict, however, Dorrell & Lee (2021) for the US electricity market. Our result is consistent with the theoretical prediction that the merit-order effect does not disappear in an oligopoly electricity market. The production coefficient turns out to be statistically insignificant in Model 5, while mortality rates from COVID-19 are significant and positively associated with LEP, suggesting that COVID-19 fatalities have a dominant impact on LEP. The announcement of infected and dead people indicates the severity of the epidemic in the countries. Fear and panic among individuals in addition to the stringency measures including telecommuting will induce them to stay more at home, increasing home electricity consumption. While people who are attenuated need treatment and equipment in hospitals, resulting in upward electricity use and demand.

The analysis highlights how important it is for government actions and the ongoing epidemic to shape long-term variations in LEP. The study finds that strict government regulations, measured using a variety of indicators, have a net deflationary effect on electricity prices, which vary between 151 and 208 €. On the other hand, when the pandemic becomes more severe as shown by confirmed cases and mortality rates, the cost of electricity rises and can range from 0.07€ to 2.44€. It is also important to note that, although strict government measures cause an instantaneous interruption in the energy supply, which lowers LEP, the long-term impacts could be different depending on how quickly the economy recovers and how well it adapts to renewable energy sources. Increased industrial activity might drive up demand for electricity as the economy recovers, possibly offsetting some price declines due to WEP and governmental stringencies.

To guarantee energy affordability and sustainability, policymakers should strike a balance between economic policies and containment measures connected to health. As death rates and verified COVID-19 cases drive up LEP, governments must manage public health imperatives while limiting negative economic effects. The results may be used to create multifaceted plans that stabilize or even lower electricity costs while also limiting the virus’s ability to spread.

4.2. Short-Run Results

The results in

Table 9 show that there were no significant short-term impacts on LEP related to government action portrayed by GSI, CHI, and EPI, as well as the death cases (CCD-19). We, however, observe a fairly significant effect of confirmed cases (CCC-19) on electricity prices. These findings raise issues of trust and confidence of citizens towards disclosed information at the beginning of the pandemic. The accuracy of information is especially questioned when COVID-19-related news is covered by the media.

Table 9 also documents that the one-lag period WEP has a favorable impact on the current LEP, albeit this influence decreases over the next several days. Notably, because WEP cannot be scheduled in the day-ahead market, immediate WEP levels have no short-term substantial impact on LEP. Rather, it is anticipated that WEP manufacturers will take part in market bidding. Moreover, the current power supply may be impacted by WEP levels from earlier periods, which may have a favorable or unfavorable effect on LEP. The previous period’s elevated WEP most certainly increased the supply of electricity, which decreased LEP but increased present electricity demand. On the other hand, lower WEP in the past would have resulted in a reduction in the amount of electricity available, which would have increased lagged LEP and perhaps decreased present LEP. We, thus, identify a day-ahead merit-order effect in the short horizon.

Models 4 and 5 shed important light on the mean reversion propensity of LEP. According to both models, LEP corrects for short-term deviations by adjusting towards its long-term equilibrium. Even with little model differences, current LEP is strongly influenced by WEP from earlier periods. Because of the merit-order structure in the electrical markets and weather-dependent WEP variability, the effect of instantaneous WEP on LEP is less clear. These findings support Mauritzen’s (2012) contention that short-term LEP may not be greatly impacted by immediate WEP.

4.3. Ganger Causality Test

Using the Dumiterscu-Hurlin method, we do the Panel Granger Causality test to look for further relationships. Except for LEP, which does not affect GSI, we find a statistically significant binary association for most of the variable pairs. LEP is not much impacted by the CHI. WEP is likewise unaffected by the CCC-19. Similarly, EPI is unaffected by CCD-19 (see

Table 10). At the 10% significance level, there is a fair unidirectional association between GSI and LEP.

We conclude that in the day-ahead electricity market during the COVID-19 era, there existed a causal relationship between WEP and LEP, meaning that changes in WEP affect price variations and vice versa.

5. Discussion

We supplement the literature with newfangled findings. First, we establish the merit-order effect at the short and long horizons. We assert that the production of wind energy stabilizes electricity markets aligning with the theoretical views of Antweiler & Muesgen (2021) and this consequently helps bring off a sustainable environment. Our results suggest that wind energy owes to a decarbonized world within our sample. Empirical studies have repeatedly contended that energy consumption, especially renewable, is a friendly endeavor of environmental sustainability (Opoku et al., 2024). However, the relationship is not static, and more tangled factors might perturb the relationship between WEP and LEP. This includes weather, seasons, geopolitics, balance between energy demand and supply (Shimomura et al., 2024).

Second, we have augmented the panel ARDL equation with confirmed cases and the number of deaths, both of which portray the severity of the virus and provoke positive spikes in local electricity prices as well. A compelling result emerges as follows. In an uncertain climate induced by the health crisis, investors’ behavior reflects insecurity, panic, and fear. Literature considering game theory is replete with overreaction to (bad) public news and its social coordinating loss value (e.g., Morris & Shin, 2002; Amato et al., 2002). Nevertheless, hard times are a premise for harnessing skills and developing portfolio tactics to manage risks and boost energy security (Kareem et al., 2022). Adaptability and reactivity to an evolving environment are also vital for the market’s maturity (Roques et al., 2005). This involves active stakeholders for a flexible transition that responds to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Heffron et al., 2021). However, adaptive investors respond differently to investment in productive technologies according to risk aversion (Yang & Johansson, 2024). Risk-averse investors respond less than those who are risk-seeking.

Third, government intervention metrics undoubtedly lead to a decline in LEP. Except for Sweden adopting less restrictive actions but should not be viewed as an outlier (Alfano et al., 2022), all Nord countries were seriously engaged in fighting the virus. The finding emphasizes the importance of how information is transmitted. A consensus opinion recognizes that people adhere to rules depending on the source of information, the degree of trust, and the credibility of conveyed information (see Elgar et al., 2020; Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020; Funke et al., 2023) and levels of corruption (see Ezeibe et al., 2020; Attila, 2020; Gebka et al., 2024). It should be noted that any of the government’s action is effective only when it is wisely implemented. Strategies to combat the virus including quarantine, facial covering, vaccination campaigns, social distancing, etc. should be based on experts’ advice. A survey carried out by the Swedish non-profit organization Vetenskap och Allmänhet revealed that 93% of Swedish citizens are attentive to the Coronavirus updates by professionals of health. The emergency containment program and financial impulse to handle the crisis have adverse effects on local electricity prices. The result informs us that accuracy and efficient use of information play a critical part in guiding investors’ behavior (Angeletos & Pavan, 2007). Importantly, announcements related to tax rates eases in credit payment should be jointly made clear and transparent by central banks and regulators to push public trust.

Fourth, government action should be leveraged to incorporate incentives for flexibility investments into economic recovery measures, as it was during the last COVID-19 episode. Aligning these incentives with global or national objectives and values—such as refraining from discriminating against particular flexibility technologies—is problematic but tempting (Heffron et al., 2021).

Fifth, the pandemic and health campaigns have shifted human and institutional behavior leading to CO2 curtailment. Since climate risks can disrupt the supply of wind energy, green investments seem to provide a solution to mitigate climate change as well as stabilize energy prices, and ensure the supply of energy (Belaïed et al., 2023). Tackling both objectives is possible through renewable energy mutual funds on the grounds of improved social and corporate governance (Ballester, 2022).

Sixth, to achieve sustainable development and environmental sustainability, policymakers must adopt a multidimensional approach that balances economic growth, resource conservation, and social equity. This requires comprehensive policy frameworks that integrate wind energy expansion, efficient resource management, and environmental protection measures (Aidukienė & Skaistė, 2013).

One key policy implication is the need for stronger regulatory frameworks to incentivize the transition toward clean energy sources. Governments should implement carbon pricing mechanisms, subsidies for renewable energy projects, and stringent environmental regulations to encourage industries to adopt greener practices. Moreover, investing in smart grids and energy storage solutions can enhance the efficiency and reliability of renewable energy integration into national grids (Lindström et al., 2015).

Another crucial aspect is sustainable land use planning. Policymakers should promote urbanization strategies that minimize environmental degradation, such as green infrastructure development, sustainable public transportation systems, and strict zoning laws to prevent deforestation and habitat loss. Encouraging circular economy models—where waste is minimized, and materials are reused—can also contribute to reducing environmental footprints (Stanciu & Mitu, 2025).

International cooperation is essential for addressing transboundary environmental challenges. Countries must engage in global climate agreements, share technological advancements, and establish cross-border policies to tackle issues such as air pollution, water scarcity, and biodiversity loss. Additionally, fostering public-private partnerships can accelerate the adoption of sustainable innovations and finance large-scale environmental projects. Norway is a good example of taking initiatives to strengthen the European Union/European Economic Area Agreements (EU/EEA) (see Cyndecka, 2020).

Finally, education and awareness campaigns are vital to ensuring the long-term sustainability of wind energy in the Nord region (Hueska et al., 2022). Governments should integrate environmental literacy into educational curricula and support community-based initiatives that promote sustainable consumption behaviors. Empowering citizens with knowledge and resources can foster a culture of environmental responsibility and active participation in sustainability efforts.

Nevertheless, some issues may appear when investing in wind energy. The primary environmental concerns associated with the use of wind turbines include the safety of wildlife, disruption of ecological systems, noise pollution, visual impact, electromagnetic disturbance, and alterations to the local climate (Dai et al., 2015).

6. Conclusion

The merit-order effect plus the government’s commitment to combat COVID-19 have implications on policy strategies. Both objectives should overlap with SDGs.

Grasping health and economic issues of the epidemic in addition to energy use poses challenges to governments, requiring urgent recommendations and to investors, responding to news, and making decisions. Our analysis which has employed a rigorous method has gauged the response of seven Nord countries located in 15 regions.

Considering a cross-country perspective has both advantages and drawbacks. Response to the crisis signals some resilience but flexibility to transition should be settled within the political agenda. Our findings should be complemented by unfolding the outcomes of government interventions through an individual lens (within a country), the use of high-frequency (e.g., hourly) data, and innovative techniques (see Thiaw et al., 2014; Marugán et al., 2018).

Political rhetoric during crisis times is a serious concern in this context (see Montiel et al., 2021; Lilleker et al., 2021; Anderouli & Brice, 2022). Governments and market regulators should advocate coherent communication and stand firm against misleading behavior. Social interaction modes such as word of mouth and social media are a path for rumor transmission. While this issue is not apparent in the case of our sample, it should be warranted in other countries and regions. Future research in this direction is welcomed. Nord countries and the European zone as a whole still have to worry about the surge of energy prices with the upcoming Ukraine crisis. The current exercise showed unsuccessful reforms and efforts to renovate electricity markets are appealing. Those hinge on more efficient production and consumption in the short run under a transparent energy market and wise investment choices offering fair profit margins for investors through a series of auctions for long-term contracts supported by regulators (Fabra, 2023). Those issues are left for further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Seifeddine Guerdally and Emna Trabelsi; methodology, Emna Trabelsi; software, Emna Trabelsi; validationEmna Trabelsi; formal analysis, First author.; investigation, Seifeddine Guerdally and Emna Trabelsi; resources, Seifeddine Guerdally ; data curation, Seifeddine Guerdally; writing—original draft preparation, Seifeddine Guerdally and Emna Trabelsi; writing—review and editing, Emna Trabelsi; visualization, Emna Trabelsi; supervision, Emna Trabelsi; project administration, Seifeddine Guerdally and Emna Trabelsi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled: Impact of Wind Energy Production on Nord Pool Electricity Market Prices pre and during Covid-19 by Guerdalli and Trabelsi (2023), which was presented at CISAI-2023, Sousse, Tunisia, July 10-11.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WEP |

Wind Energy Production |

| LEP |

Local Electricity Price |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Infectious Disease |

| CHI |

Containment Health Index |

| EPI |

Economic Policy Index |

| GSI |

Government Stringency Index |

| CCC-19 |

COVID-19 cases |

| CCV-19 |

Death cases |

| US |

United States |

| LM |

Lagrange Multiplier |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| EU |

European Union |

| EEA |

European Economic Area Agreement |

| IPS |

IM, Pesaran, and Shin |

| CIPS |

Cross-sectional augmented of Im, Pesaran, and Shin |

| TCIPS |

Truncated Cross-sectional augmented of Im, Pesaran, and Shin |

| PMG |

Pooled Mean Group |

| ADF |

Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| ARDL |

Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| DK |

Denmark |

| EE |

Estonia |

| LT |

Latvia |

| FI |

Finland |

| NW |

Norway |

| LV |

Latvia |

| SE |

Sweden |

| 1 |

For a comprehensive survey of the merit-order effect from different sources of renewable energy, we recommend Bublitz et al. (2017). |

| 2 |

Using pooled OLS in our case may lead to biased estimations (see Baltagi, 2009; Okui and Wang, 2021). |

References

- Acar, B., Selcuk, O., & Dastan, S. A. (2019). The merit order effect of wind and river type hydroelectricity generation on Turkish electricity prices. Energy Policy, 132, 1298-1319. [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., Kakhbod, A., & Ozdaglar, A. (2017). Competition in electricity markets with renewable energy sources. The Energy Journal, 38(1_suppl), 137-156. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T., Baig, M., & Hui, J. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and economic impact. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 36(COVID19-S4), S73.https://doiorg/ 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2638.

- Aidukienė, L., & Skaistė, G. (2013). Sustainable development of Lithuanian electricity energy sector. Journal of Economics and Development Studies, 1(3).

- Akrofi, M. M., & Antwi, S. H. (2020). COVID-19 energy sector responses in Africa: A review of preliminary government interventions. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, 101681. [CrossRef]

- Amato, J. D., Morris, S., & Shin, H. S. (2002). Communication and monetary policy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 18(4), 495-503. [CrossRef]

- Angeletos, G. M., & Pavan, A. (2007). Efficient use of information and social value of information. Econometrica, 75(4), 1103-1142. [CrossRef]

- Andreouli, E., & Brice, E. (2022). Citizenship under COVID-19: An analysis of UK political rhetoric during the first wave of the 2020 pandemic. Journal of community & applied social psychology, 32(3), 555-572. [CrossRef]

- Alfano, V., Ercolano, S., & Pinto, M. (2022). Fighting the COVID pandemic: National policy choices in non-pharmaceutical interventions. Journal of Policy Modeling, 44(1), 22-40. [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American economic review, 110(3), 629-676. [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, W., & Muesgens, F. (2021). On the long-term merit order effect of renewable energies. Energy Economics, 99, 105275. [CrossRef]

- Askitas, N., Tatsiramos, K., & Verheyden, B. (2021). Estimating worldwide effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 incidence and population mobility patterns using a multiple-event study. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1972. [CrossRef]

- Azofra, D., Jiménez, E., Martínez, E., Blanco, J., & Saenz-Díez, J. C. (2014). Wind power merit-order and feed-in-tariffs effect: A variability analysis of the Spanish electricity market. Energy Conversion and Management, 83, 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Badyda, K., & Dylik, M. (2017). Analysis of the Impact of Wind on Electricity Prices Based on Selected European Countries. Energy Procedia, 105, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. (2009). Panel Data Models With Interactive Fixed Effects. Econometrica, 77(4), 1229–1279. [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. (Badi H., & Baltagi, B. H. (Badi H. (2009). A companion to Econometric analysis of panel data. 295. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/A+Companion+to+Econometric+Analysis+of+Panel+Data-p-9780470744031.

- Bargain, O., & Aminjonov, U. (2020). Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. Journal of public economics, 192, 104316. [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F., Al-Sarihi, A., & Al-Mestneer, R. (2023). Balancing climate mitigation and energy security goals amid converging global energy crises: The role of green investments. Renewable Energy, 205, 534-542. [CrossRef]

- Bell, W. P., Wild, P., Foster, J., & Hewson, M. (2017). Revitalising the wind power induced merit order effect to reduce wholesale and retail electricity prices in Australia. Energy Economics, 67, 224-241. [CrossRef]

- Benhmad, F., & Percebois, J. (2016). Wind power feed-in impact on electricity prices in Germany 2009-2013. European Journal of Comparative Economics.

- Bento, P. M. R., Mariano, S. J. P. S., Calado, M. R. A., & Pombo, J. A. N. (2021). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on electric energy load and pricing in the Iberian electricity market. Energy Reports, 7, 4833-4849. [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S., Bollino, C. A., D’Errico, M. C., & Polinori, P. (2022). COVID-19 lockdown and market power in the Italian electricity market. Energy Policy, 161, 112700. [CrossRef]

- Brancucci Martinez-Anido, C., Brinkman, G., & Hodge, B. M. (2016). The impact of wind power on electricity prices. Renewable Energy, 94, 474–487. [CrossRef]

- Bublitz, A., Keles, D., & Fichtner, W. (2017). An analysis of the decline of electricity spot prices in Europe: Who is to blame?. Energy Policy, 107, 323-336.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.04.034.

- Costa, V. B., Bonatto, B. D., Pereira, L. C., & Silva, P. F. (2021). Analysis of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the Brazilian distribution electricity market based on a socioeconomic regulatory model. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 132, 107172. [CrossRef]

- Cludius, J., Hermann, H., Matthes, F. C., & Graichen, V. (2014). The merit order effect of wind and photovoltaic electricity generation in Germany 2008–2016: Estimation and distributional implications. Energy economics, 44, 302-313. [CrossRef]

- Csereklyei, Z., Qu, S., & Ancev, T. (2019). The effect of wind and solar power generation on wholesale electricity prices in Australia. Energy Policy, 131, 358–369. [CrossRef]

- Cyndecka, M. A. (2020). EEA Law and the Climate Change. The Case of Norway. Polish Rev. Int’l & Eur. L., 9, 107. [CrossRef]

- Dai, K., Bergot, A., Liang, C., Xiang, W. N., & Huang, Z. (2015). Environmental issues associated with wind energy–A review. Renewable energy, 75, 911-921. [CrossRef]

- De La Nieta, A. A. S., Contreras, J., Munoz, J. I., & O’Malley, M. (2014). Modeling the Impact of a Wind Power Producer as a Price-Maker. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 29(6), 2723–2732. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on European power markets. https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/energy-and-resources/articles/the-impact-of-covid19-on-european-power-markets.html.

- De Miera, G. S., del Río González, P., & Vizcaíno, I. (2008). Analysing the impact of renewable electricity support schemes on power prices: The case of wind electricity in Spain. Energy policy, 36(9), 3345-3359. [CrossRef]

- Doering, K., Sendelbach, L., Steinschneider, S. & Anderson, C. Lindsay (2021).The effects of wind generation and other market determinants on price spikes, Applied Energy, 300, 117316. [CrossRef]

- Dorrell, J., & Lee, K. (2021). The Price of Wind: An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Wind Energy and Electricity Price across the Residential, Commercial, and Industrial Sectors. Energies, 14(12). [CrossRef]

- Ederer, N. (2015). The market value and impact of offshore wind on the electricity spot market: Evidence from Germany. Applied Energy, 154, 805-814. [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F. J., Stefaniak, A., & Wohl, M. J. (2020). The trouble with trust: Time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Social science & medicine, 263, 113365. [CrossRef]

- Attila, J. (2020). Corruption, Globalization and the Outbreak of COVID-19. Available at SSRN 3742347. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3742347.

- Escribano, Á., & Ortega, Á. (2021). A structural analysis of the merit-order effect in the Spanish day-ahead power market. http://hdl.handle.net/10016/33298.

- Fabra, N. (2023). Reforming European electricity markets: Lessons from the energy crisis. Energy Economics, 126, 106963. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, N. C., & da Silva, P. P. (2019). The “Merit-order effect” of wind and solar power: Volatility and determinants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 102, 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Funke, M., Ho, T. K., & Tsang, A. (2023). Containment measures during the COVID pandemic: The role of non-pharmaceutical health policies. Journal of Policy Modeling, 45(1), 90-102. [CrossRef]

- Gebka, B., Kanungo, R. P., & Wildman, J. (2024). The transition from COVID-19 infections to deaths: Do governance quality and corruption affect it?. Journal of Policy Modeling. [CrossRef]

- González-López, R., & Ortiz-Guerrero, N. (2022). Integrated analysis of the Mexican electricity sector: Changes during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Electricity Journal, 35(6), 107142. [CrossRef]

- Green, R., & Vasilakos, N. V. (2011). The long-term impact of wind power on electricity prices and generating power. ESRC Centre for Competition Policy Working Paper Series. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1851311.

- Guerdalli, S. & Trabelsi, E. (2023). Impact of Wind Energy Production on Nord Pool Electricity Market Prices pre and during Covid-19. Conférence Internationale sur les Sciences Appliquées et l’Innovation (CISAI-2023), Proceedings of Engineering & Technology-PET-Vol 77, 10-11 July, Sousse, Tunisia.

- Halbrügge, S., Schott, P., Weibelzahl, M., Buhl, H. U., Fridgen, G., & Schöpf, M. (2021). How did the German and other European electricity systems react to the COVID-19 pandemic?. Applied Energy, 285, 116370. [CrossRef]

- Heffron, R. J., Körner, M. F., Schöpf, M., Wagner, J., & Weibelzahl, M. (2021). The role of flexibility in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Contributing to a sustainable and resilient energy future in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 140, 110743.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110743.

- Hirth, L. (2013). The market value of variable renewables. The effect of solar wind power variability on their relative price. Energy Economics, 38, 218–236. [CrossRef]

- Hosius, E., Seebaß, J. V., Wacker, B., & Schlüter, J. C. (2023). The impact of offshore wind energy on Northern European wholesale electricity prices. Applied Energy, 341, 120910. [CrossRef]

- Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115(1), 53–74. [CrossRef]

- Jaraite, J., Kažukauskas, A., Brännlund, R., Chandra, K., & Kriström, B. (2019). Intermittency and Pricing Flexibility in Electricity Markets. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Juergensen, J., Guimón, J., & Narula, R. (2020). European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: assessing impact and policy responses. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 47(3), 499–510. [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. (1999). Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 90(1), 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Karim, S., & Naeem, M. A. (2022). Clean energy, Australian electricity markets, and information transmission. Energy Research Letters, 3(3). [CrossRef]

- Ketterer, J. C. (2014). The impact of wind power generation on the electricity price in Germany. Energy Economics, 44, 270–280. [CrossRef]

- Krohn, S., Morthorst, P. E., & Awerbuch, S. (2009). The economics of wind energy. European Wind Energy Association, 3. https://www.unioviedo.es/ate/manuel/seasturlab/EWEA.pdf.

- Kumar, A., Priya, B., & Srivastava, S. K. (2021). Response to the COVID-19: Understanding implications of government lockdown policies. Journal of policy modeling, 43(1), 76-94. [CrossRef]

- Lazo, J., Aguirre, G., & Watts, D. (2022). An impact study of COVID-19 on the electricity sector: A comprehensive literature review and Ibero-American survey. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 158, 112135. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on electricity consumption in Sweden. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1809315.

- Lilleker, D., Coman, I. A., Gregor, M., & Novelli, E. (2021). Political communication and COVID-19: Governance and rhetoric in global comparative perspective. In Political Communication and COVID-19 (pp. 333-350). Routledge. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/63306/9781003120254_webpdf.pdf?sequence=1#page=356.

- Lindström, E., Norén, V., & Madsen, H. (2015). Consumption management in the Nord Pool region: A stability analysis. Applied Energy, 146, 239-246. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F., Sá, J., & Santana, J. (2018). Renewable generation, support policies and the merit order effect: a comprehensive overview and the case of wind power in Portugal. Electricity Markets with Increasing Levels of Renewable Generation: Structure, Operation, Agent-Based Simulation, and Emerging Designs, 227-263. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-74263-2_9.

- Lynch, M., & Curtis, J. (2016). The effects of wind generation capacity on electricity prices and generation costs: a Monte Carlo analysis. Applied Economics, 48(2), 133–151. [CrossRef]

- Maital, S., & Barzani, E. (2020). The global economic impact of COVID-19: A summary of research. Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research, 2020, 1-12. https://www.neaman.org.il/EN/Files/Global%20Economic%20Impact%20of%20COVID-19_20200322163553.399.pdf.

- Makalska, T., Varfolomejeva, R., & Oleksijs, R. (2018). The Impact of Wind Generation on the Spot Market Electricity Pricing. Proceedings—2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe 2018. [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U., & Nagel, S. (2011). Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking?. The quarterly journal of economics, 126(1), 373-416. [CrossRef]

- Martí-Ballester, C. P. (2022). Do renewable energy mutual funds advance towards clean energy-related sustainable development goals?. Renewable Energy, 195, 1155-1164. [CrossRef]

- Marugán, A. P., Márquez, F. P. G., Perez, J. M. P., & Ruiz-Hernández, D. (2018). A survey of artificial neural network in wind energy systems. Applied energy, 228, 1822-1836. [CrossRef]

- Mastropietro, P., Rodilla, P., & Batlle, C. (2020). Emergency measures to protect energy consumers during the Covid-19 pandemic: A global review and critical analysis. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, 101678. [CrossRef]

- Mauritzen, J. (2012). What Happens When it’s Windy in Denmark? An Empirical Analysis of Wind Power on Price Variability in the Nordic Electricity Market. SSRN Electronic Journal, 889. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S., Sun, R., & Guo, F. (2021). Impact of renewable energy power generation share on Germany’s electricity prices. 资源科学, 43(8), 1562–1573. [CrossRef]

- Mertens, S. (2005). Wind energy in the built environment. Brentwood, UK: Multi Science Publishing Company.

- Montiel, C. J., Uyheng, J., & Dela Paz, E. (2021). The language of pandemic leaderships: Mapping political rhetoric during the COVID-19 outbreak. Political psychology, 42(5), 747-766. [CrossRef]

- Moon, H., Perron, B., Moon, H., & Perron, B. (2004). Testing for a unit root in panels with dynamic factors. Journal of Econometrics, 122(1), 81–126. [CrossRef]

- Morris, S., & Shin, H. S. (2002). Social value of public information. American economic review, 92(5), 1521-1534. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, V. (2009). Wind energy: renewable energy and the environment. CRC press. [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, M., & Fürsch, M. (2009). The impact of an increasing share of RES-E on the Conventional Power Market — The Example of Germany. Zeitschrift Für Energiewirtschaft 2009 33:3, 33(3), 246–254. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhout, F., & Brand, A. (2011). The impact of wind power on day-ahead electricity prices in the Netherlands. 2011 8th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), 226–230. [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N., Zarazua de Rubens, G. Z., Enevoldsen, P., & Behzadi Forough, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the electricity sector in Spain: an econometric approach based on prices. International Journal of Energy Research, 45(4), 6320-6332.https://doi.org/10.1002/er.6259.

- Okui, R., & Wang, W. (2021). Heterogeneous structural breaks in panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 220(2), 447–473. [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E. E. O., Acheampong, A. O., & Aluko, O. A. (2024). Impact of rural-urban energy equality on environmental sustainability and the role of governance. Journal of Policy Modeling. [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E. E. O., & Acheampong, A. O. (2023). Energy justice and economic growth: Does democracy matter. Journal of Policy Modeling, 45(1), 160-186. [CrossRef]

- Osman, M., Gachino, G., & Hoque, A. (2016). Electricity consumption and economic growth in the GCC countries: Panel data analysis. Energy Policy, 98, 318–327. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Izquierdo, M., & del Río, P. (2020). An analysis of the socioeconomic and environmental benefits of wind energy deployment in Europe. Renewable Energy, 160, 1067-1080. [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. (1999). Critical Values for Cointegration Tests in Heterogeneous Panels with Multiple Regressors. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(S1), 653–670. [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P., Pedroni, & Peter. (2004). Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J. P., & Rodrigues, P. M. M. (2015). The impact of wind generation on the mean and volatility of electricity prices in Portugal. 2015 12th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), 2015-August. [CrossRef]

- Persyn, D., Westerlund, J., Persyn, D., & Westerlund, J. (2008). Error-correction–based cointegration tests for panel data. Stata Journal, 8(2), 232–241. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:tsj:stataj:v:8:y:2008:i:2:p:232-241. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(2), 265–312. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1999). Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(446), 621. [CrossRef]

- Pineau, P.-O., Nasseri, Y., & Rafizadeh, N. (2020). The Effects of Wind Power Generation on the Electricity Price: High Frequency Evidence from New York. Social Science Research Network. [CrossRef]

- Pointel, J. B. (2016). La réglementation économique dans les pays scandinaves de l’Union européenne. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01794518/document.

- Pradhan, A. K., Rout, S., & Khan, I. A. (2021). Does market concentration affect wholesale electricity prices? An analysis of the Indian electricity sector in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Utilities Policy, 73, 101305. [CrossRef]

- Rana, V., & Ansari, M. A. (2013). Wind farm integration effect on electricity market price. 2013 International Conference on Energy Efficient Technologies for Sustainability, ICEETS 2013, 349–354. [CrossRef]

- Roques, F. A., Newbery, D. M., & Nuttall, W. J. (2005). Investment incentives and electricity market design: the British experience. Review of Network Economics, 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G., Wu, J., Zhong, H., Xia, Q., & Xie, L. (2021). Quantitative assessment of US bulk power systems and market operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Energy, 286, 116354.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116354.

- Saidur, R., Rahim, N. A., Islam, M. R., & Solangi, K. H. (2011). Environmental impact of wind energy. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 15(5), 2423-2430. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, M., Moreno, R., Alvarado, D., Suazo-Martínez, C., Negrete-Pincetic, M., Olivares, D., .. & Basso, L. J. (2022). The diverse impacts of COVID-19 on electricity demand: the case of Chile. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 138, 107883. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, I., Moreno-Munoz, A., Quintero-Jiménez, P., Garcia-Torres, F., & Gonzalez-Redondo, M. J. (2021). Electricity demand during pandemic times: The case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy policy, 148, 111964.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111964.

- Sensfuß, F., Ragwitz, M., & Genoese, M. (2008). The merit-order effect: A detailed analysis of the price effect of renewable electricity generation on spot market prices in Germany. Energy policy, 36(8), 3086-3094.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.03.035.

- Simonov, A., Sacher, S., Dubé, J. P., & Biswas, S. (2022). Frontiers: the persuasive effect of Fox News: noncompliance with social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Marketing Science, 41(2), 230-242. [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, M., Keeley, A. R., Matsumoto, K. I., Tanaka, K., & Managi, S. (2024). Beyond the merit order effect: Impact of the rapid expansion of renewable energy on electricity market price. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 114037. [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K., Begum, R. A., Syed Abdullah, S. M., & Jaafar, M. (2015). Dynamics of energy use, technological innovation, economic growth and trade openness in Malaysia. Energy, 90, 1497–1507. [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S. A., & Bello, M. O. (2022). Wind energy and sustainable electricity generation: evidence from Germany. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(7), 9185-9198. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B. K. (2013). The avian benefits of wind energy: A 2009 update. Renewable Energy, 49, 19-24. [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, C. V., & Mitu, N. E. (2025). Price Behavior and Market Integration in European Union Electricity Markets: A VECM Analysis. Energies, 18(4), 770. [CrossRef]

- Szczygielski, J. J., Brzeszczyński, J., Charteris, A., & Bwanya, P. R. (2022). The COVID-19 storm and the energy sector: The impact and role of uncertainty. Energy Economics, 109, 105258. [CrossRef]

- Thiaw, L., Sow, G., & Fall, S. (2014). Application of neural networks technique in renewable energy systems. https://ijssst.info/Vol-15/No-5/data/5198a006.pdf.

- Ulm, L., Koduvere, H., & Palu, I. (2020). ’Discount’-the renewable energy production impact on electricity price. 2020 IEEE 61st Annual International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University, RTUCON 2020—Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Unger, E. A., Ulfarsson, G. F., Gardarsson, S. M., & Matthiasson, T. (2018). The effect of wind energy production on cross-border electricity pricing: The case of western Denmark in the Nord Pool market. Economic Analysis and Policy, 58, 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Veraart, A. (2015). Modelling the Impact of Wind Power Production on Electricity Prices by Regime-Switching Levy Semistationary Processes. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Wang, S. (2015). Impacts of wind energy on environment: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 49, 437-443. [CrossRef]

- Webster, R. K., Brooks, S. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). How to improve adherence with quarantine: rapid review of the evidence. Public health, 182, 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L., Suomalainen, K., Sharp, B., Yi, M., & Sheng, M. S. (2022a). Impact of wind-hydro dynamics on electricity price: A seasonal spatial econometric analysis. Energy, 238, 122076. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L., Sharp, B., Suomalainen, K., Sheng, M. S., & Guang, F. (2022b). The impact of COVID-19 containment measures on changes in electricity demand. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, 29, 100571. [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for Error Correction in Panel Data*. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(6), 709–748. [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J., & Edgerton, D. L. (2008). A simple test for cointegration in dependent panels with structural breaks. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 70(5), 665–704. [CrossRef]

- Wirdemo, A. (2017). The Impact of Wind Power Production on Electricity Price Volatility MASTER’ S THESIS The Impact of Wind Power Production on Electricity Price Volatility.

- Wolde-Rufael, Y., & Weldemeskel, E. M. (2020). Environmental policy stringency, renewable energy consumption and CO2 emissions: Panel cointegration analysis for BRIICTS countries. 17(10), 568–582. https://di.org/10.1080/15435075.2020.1779073.

- Woo, C. K., Zarnikau, J., Kadish, J., Horowitz, I., Wang, J., & Olson, A. (2013). The Impact of Wind Generation on Wholesale Electricity Prices in the Hydro-Rich Pacific Northwest. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 28(4), 4245–4253. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., & Johansson, D. J. (2024). Adapting to uncertainty: Modeling adaptive investment decisions in the electricity system. Applied Energy, 358, 122603. [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Dehkordi, P., Rakai, L., Zareipour, H., & Rosehart, W. (2016). Big Data Analytics for Modelling the Impact of Wind Power Generation on Competitive Electricity Market Prices. 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 2016-March, 2528–2535. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H., Tan, Z., He, Y., Xie, L., & Kang, C. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 for the electricity industry: A comprehensive review. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, 6(3), 489-495. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9160443/. https://doi:.org/10.17775/cseejpes.2020.02500.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).