1. Introduction: Core Concepts and Their Mathematical Representation

At its core, GP is a stochastic optimization

technique inspired by biological evolution. The process begins with

an initial population of randomly generated computer programs. These programs

are composed of functions and terminals appropriate for the problem domain.

Advancements in technology have influenced the software industry (Kodytek et

al., 2024) through automation, streamlining software development and testing.

Kodytek et al. focused on an automated system for generating LabVIEW code,

testing it on programming problems. Results indicated it produced functional,

accurate code, suggesting potential benefits for both experienced and novice

developers. LabVIEW (Laboratory Virtual Instrument Engineering Workbench) uses

visual elements to simplify application design for measurement and automation.

Programs consist of "virtual instruments" (VIs), graphical blocks

connecting data flow, with a front panel (user interface) and block diagram

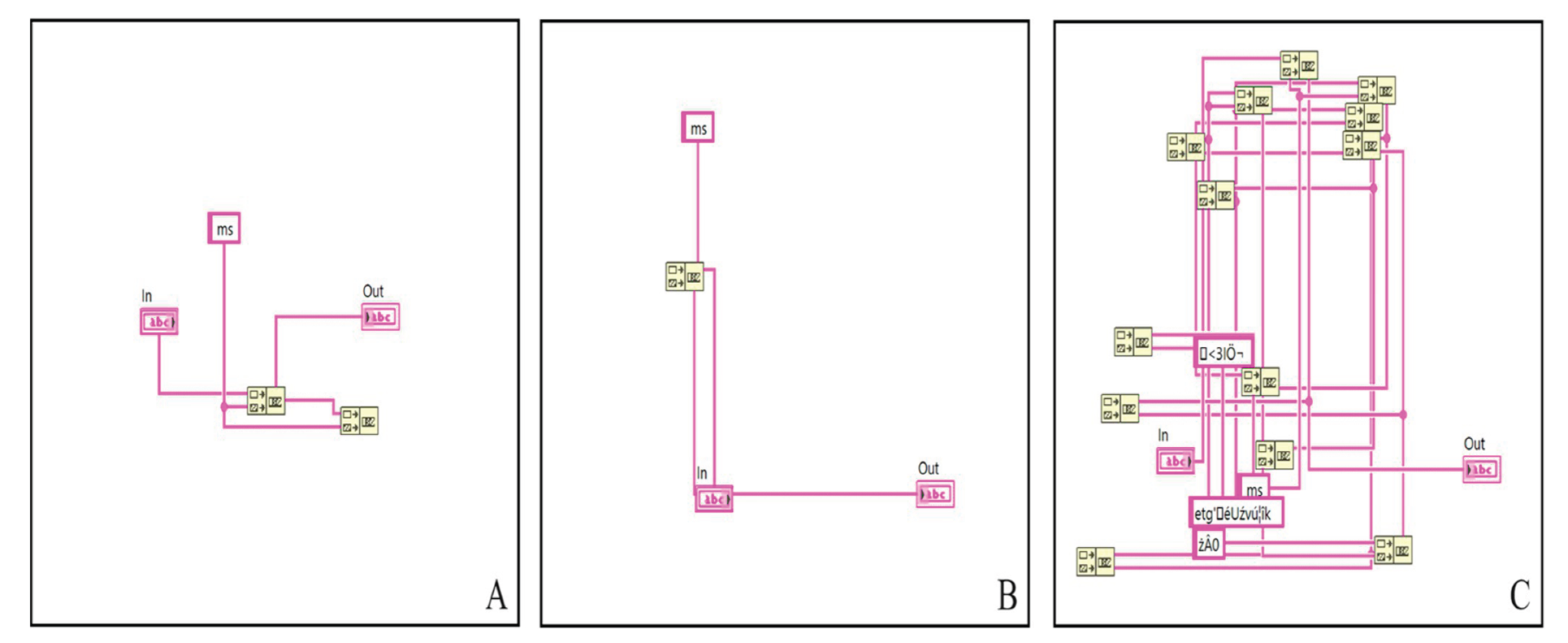

(logic and code)., as in

Figure 1 (Kodytek

et al., 2024).

In (Kodytek et al., 2024), the authors explain that

their automated code generation method uses two main scripting methods called

the "Wirer" and the "Creator" to create and manage code.

These methods help organize the code information effectively, and the details

about how they work are provided in a specific section of the paper.

Figure 2 (Kodytek et al.,

2024)illustrates the entire process of how the code is generated, starting from

defining what the user needs to creating the final code.

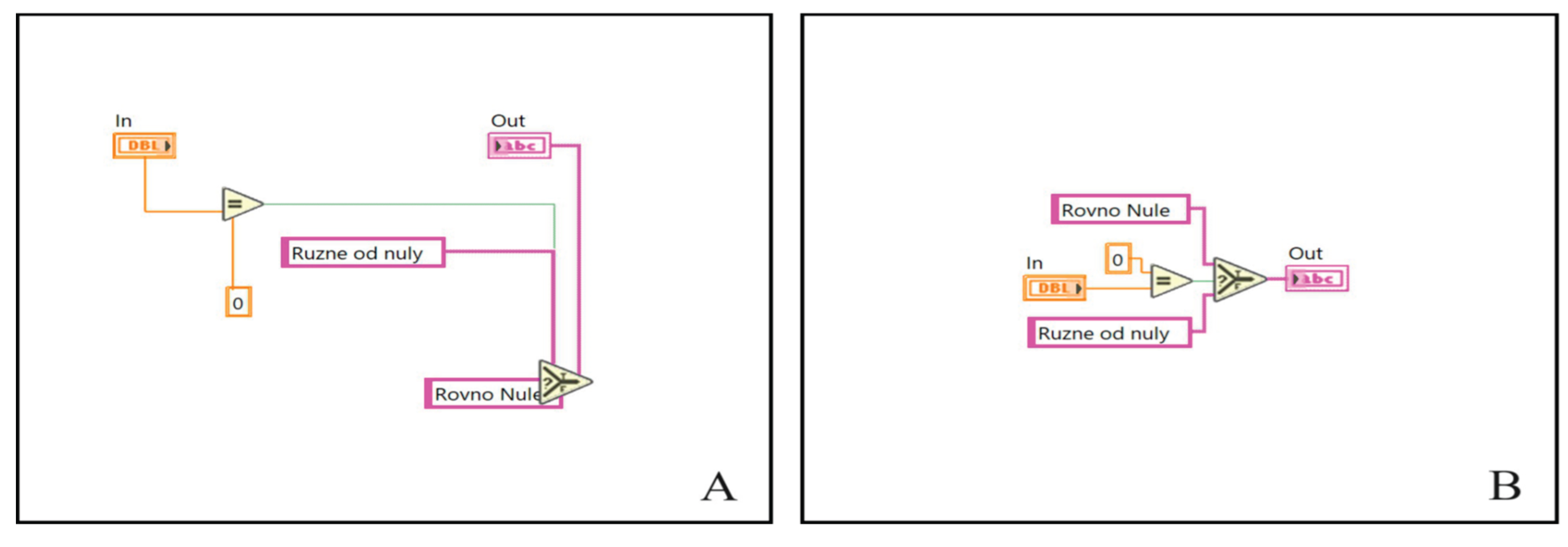

Following(Kodytek et al., 2024), the

"Wirer" and the "Creator" are compared to chromosomes in

human cells, where each has specific roles like genes. The Creator adds

functions to a graphical programming diagram, while the Wirer connects these

functions by managing their inputs and outputs. This analogy (Kodytek et al.,

2024)helps explain how the automated code development system organizes and

structures the programming elements, similar to how genetic information is

organized in living organisms, as depicted in

Figure 3 (Kodytek et al., 2024).

Kodytek et al. (2024) described a process where

algorithms evolve by selecting the best "parent" genes and then

applying mutations to create new variations. For the Creator genes(Kodytek et

al., 2024), a random number is generated, and if it's below 25, the gene may

change, either increasing or decreasing its value slightly. Similarly (Kodytek

et al., 2024), the Wirer genes also undergo mutations, but with different

probabilities, allowing for more variability in the changes, which helps improve

the overall performance of the code generated by the algorithm(See

Figure 4 (Kodytek et al., 2024)).

The first problem tested in the study was a

"string problem," which involves manipulating sequences of characters

or text. This problem had two main challenges: adjusting the size of the data

and changing the values within that data. The researchers ran the algorithm

several times to see how well it performed, and the results were illustrated in

(

Figure 5 (Kodytek et al., 2024)).

The results (Kodytek et al., 2024) indicated that

the algorithm can produce consistent and effective solutions even when the

input parameters change. Based on (Kodytek et al., 2024), one important part of

testing the automated code development was checking how well the generated

programs could perform a simple addition function.

The results from these tests provided clear

insights that were not as obvious when looking at more complicated mathematical

functions. These findings are illustrated in (

Figure 6 (Kodytek et al., 2024) included in the research, showing how the

simpler tasks helped clarify the program's effectiveness.

In symbolic regression, the function set may

include arithmetic operators {+, -, *, /}, while the terminal set consists of

input variables and constants. Each program's fitness is evaluated using

training data. The fittest programs are selected for the next generation via

genetic operators like crossover (swapping subtrees) and mutation (random

alterations)(Zakharov, 2023).

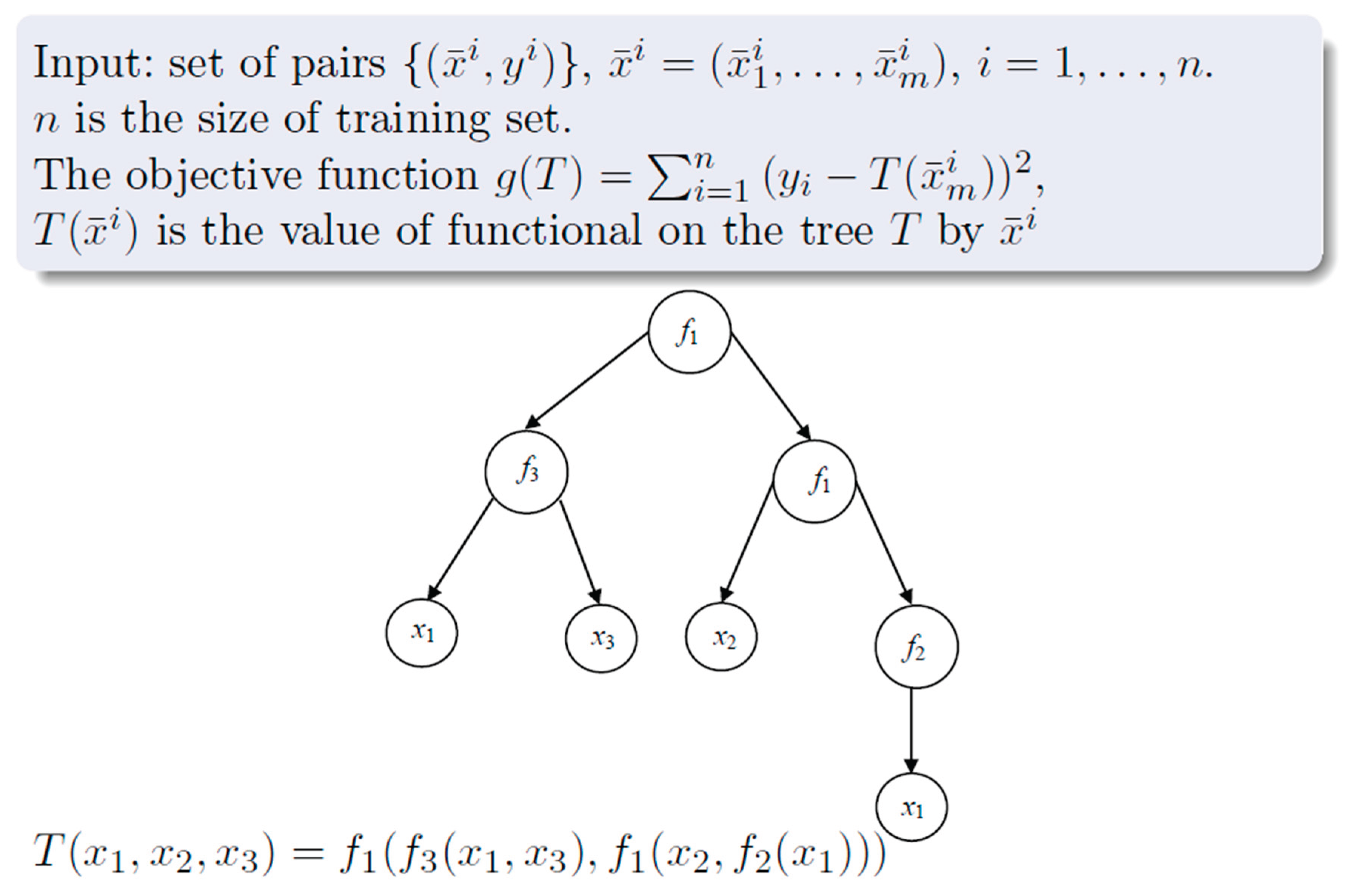

Optimization problems with tree-based solutions involve creating complex models)(Zakharov, 2023), like mathematical functions or algorithms, from experimental data and a set of variables. This process often uses decision trees)(Zakharov, 2023), which help in recognizing patterns in biological sequences, such as proteins. In genetic programming, a method inspired by natural evolution)(Zakharov, 2023), a group of these tree structures is improved over time through processes like natural selection, including selection, crossover, and mutation, to find the best solution to a given problem, as in

Figure 7 (Zakharov, 2023).

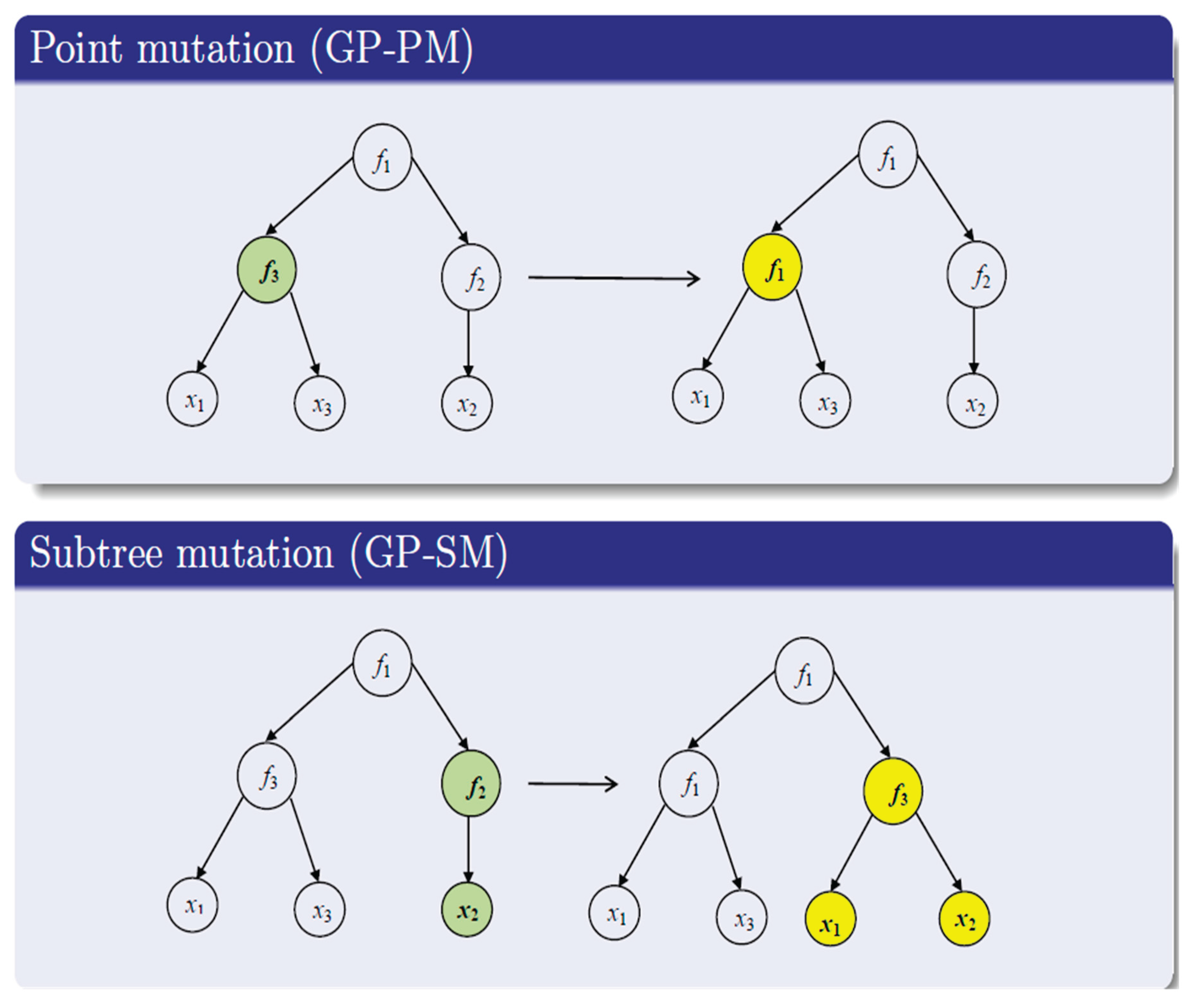

Figure 8 (Zakharov, 2023)reads mutation operators for trees as techniques used in genetic programming (GP) to modify tree-like structures that represent solutions or functions. Two common types of mutation are point mutation (GP-PM) (Zakharov, 2023), where a single node in the tree is changed to a different function or variable, and subtree mutation (GP-SM), where a whole subtree is replaced with another subtree. These operators help maintain diversity in the population of solutions(Zakharov, 2023), allowing for exploration of new potential solutions during the evolutionary process.

By merging the characteristics of two current solutions (parents), the Optimal Recombination Problem (ORP) (Zakharov, 2023) is a combinatorial optimization idea aimed at generating fresh solutions (offspring). Here(Zakharov, 2023), every parent possesses a set of characteristics; the objective is to create offspring that preserves characteristics from either parent while guaranteeing that this new result is at least as good as any other possible combination of traits from the parents. Many genetic algorithms—which simulate natural selection to identify best solutions to difficult challenges.

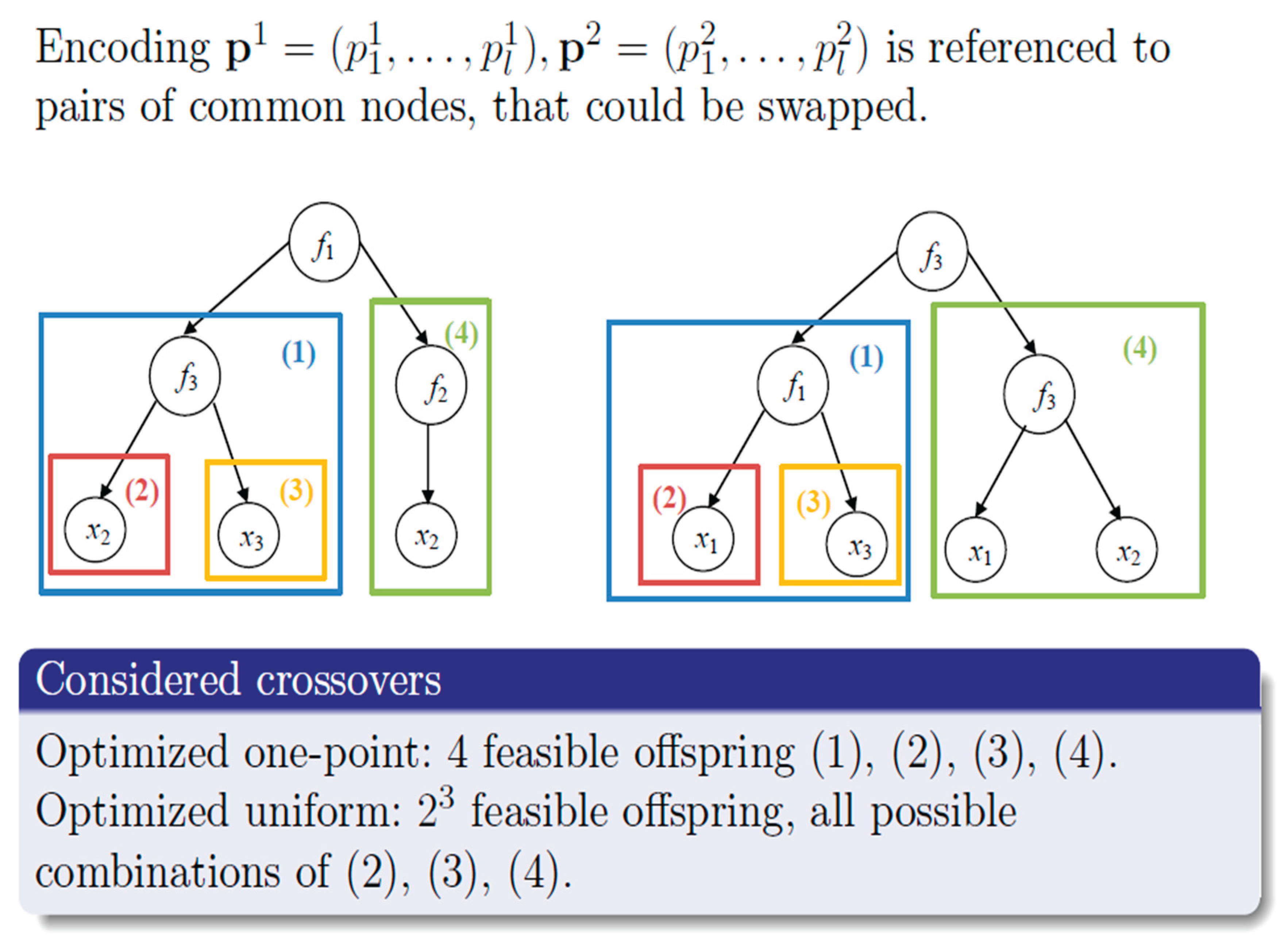

Observing

Figure 9 (Zakharov, 2023), ORP on trees refers to "Optimal Recombination in Genetic Programming" applied to tree structures, which are often used to represent solutions in genetic algorithms. In this context(Zakharov, 2023), it involves encoding pairs of nodes in a tree that can be swapped or recombined to create new offspring solutions. The goal is to optimize the process of generating these new solutions by considering different crossover methods, such as one-point and uniform crossover, to produce the most effective combinations of existing solutions.

This evolutionary process (Kodytek et al., 2024; Zakharov, 2023; Garcia et al., 2020)continues for many generations to discover a solution program. Mathematically, the search space of GP includes all possible programs from the function and terminal sets. This space is vast(Kodytek et al., 2024; Zakharov, 2023; Garcia et al., 2020), discrete, and often characterized by a highly complex and rugged fitness landscape. The tree-based representation of programs, while flexible(Kodytek et al., 2024; Zakharov, 2023; Garcia et al., 2020), introduces significant challenges for theoretical analysis. The size and shape of the program trees are not fixed(Kodytek et al., 2024; Zakharov, 2023; Garcia et al., 2020), leading to a variable-length representation that complicates the application of classical theoretical tools from evolutionary computation.

Exploring (Garcia et al., 2020), genetic algorithms (GAs)—methods inspired by natural selection used to solve challenging optimization issues in mathematics and engineering—were investigated. These algorithms build a population of possible solutions (Garcia et al., 2020), assess their performance using a fitness function, then iteratively improve them through techniques like selection, crossover, and mutation. Using GAs to locate the maximum values of challenging mathematical functions, the authors (Garcia et al., 2020) created a technique implemented in Python and tested on certain functions to verify its efficacy.

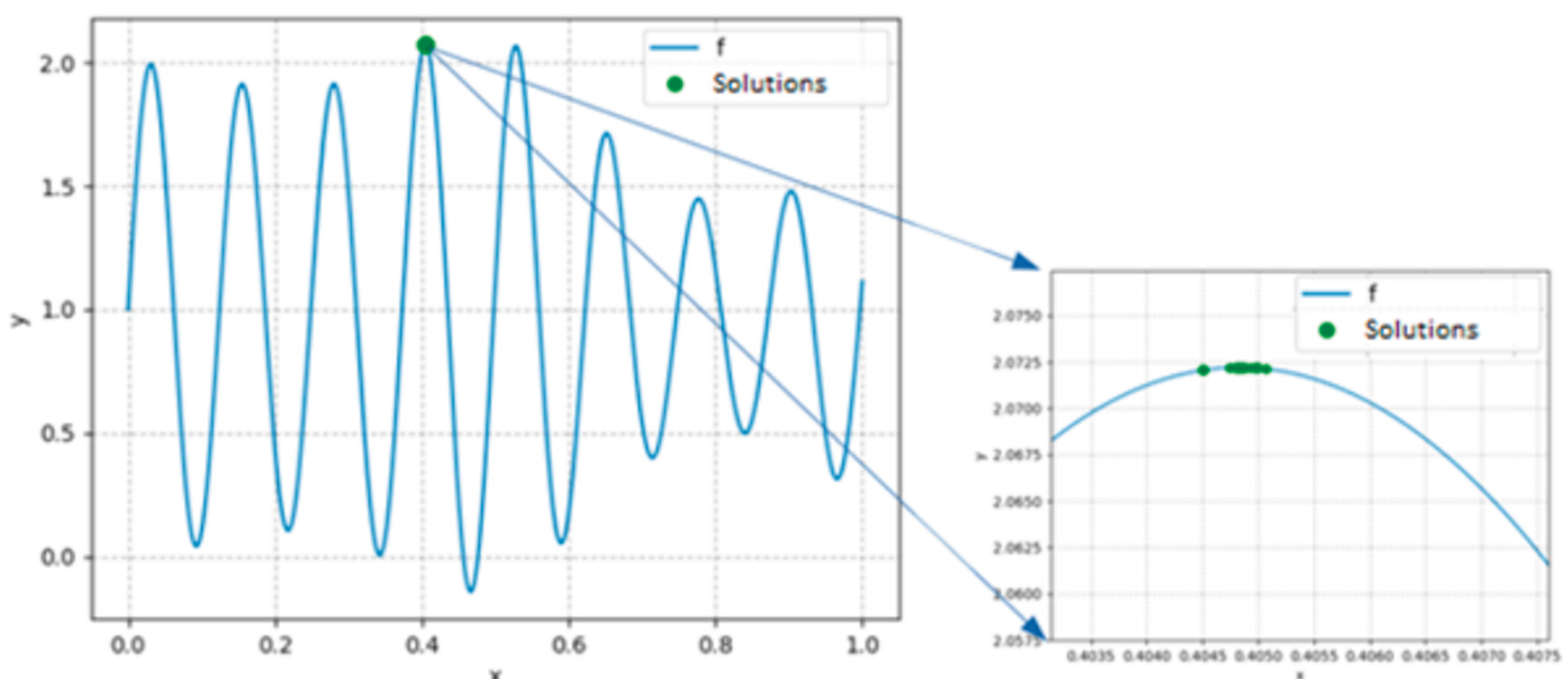

Building on (Garcia et al., 2020), the writers outlined their mathematical optimization problem-solving using a genetic algorithm (GA). Beginning with a population of 300 chromosomes, which represent possible solutions (Garcia et al., 2020), they let the algorithm run for a maximum of 200 iterations. After 100 runs of the algorithm (Garcia et al., 2020), they discovered an ideal solution denoted by a particular binary code (the optimum chromosome) that matches to a numerical value and possesses a calculated performance score reflecting how well it resolves the problem, as in

Figure 10 (Garcia et al., 2020).

Figure 10 (Garcia et al., 2020) shows that the function f has eight peaks (maximum values) between 0 and 1, two of which are close in value. This closeness can lead genetic algorithms (AG) to mistakenly identify the wrong peak as the highest one. The next challenge is to find the maximum of another function, g, which depends on two variables (x and y) within the range of -5 to 5, requiring the genetic algorithm to use chromosomes that represent both and as a pair.

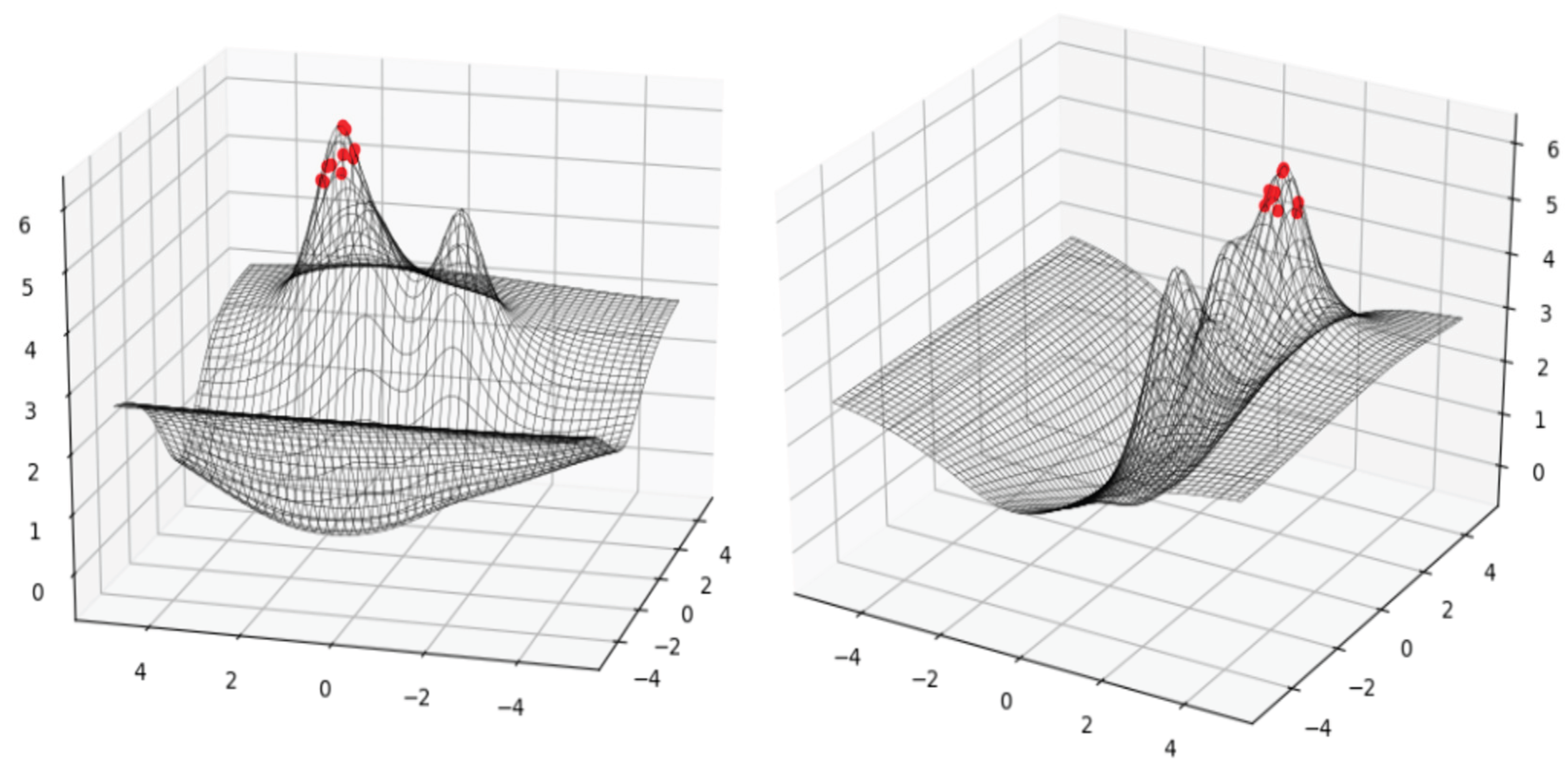

Describing the setup for a genetic algorithm(Garcia et al., 2020), which is a method used to find optimal solutions to problems by mimicking the process of natural selection. They used a population of 300 "individuals," each represented by a chromosome of 50 bits(Garcia et al., 2020) and allowed the algorithm to run for a maximum of 1000 cycles. The best solution they found after running the algorithm 100 times is represented by a specific binary string (Equation 1), which corresponds to a point in a two-dimensional space with coordinates (2.00085124, 1.89686467) and a performance value of approximately 6.04.

(1)

Figure 11 (Garcia et al., 2020) illustrates the results of a genetic algorithm (GA) applied to a mathematical optimization problem, showing the best solutions (represented by red dots) found within a specific range. The graph displays two local maxima(Garcia et al., 2020), indicating that the GA identified not only the optimal solution but also several other close solutions, demonstrating its ability to explore the solution space effectively. The algorithm was efficient(Garcia et al., 2020), typically completing its search for the best solution in just two to three minutes over 200 cycles, and tracking the other solutions helps visualize how the algorithm improves over time.

Figure 11 (Garcia et al., 2020) illustrates a mathematical function, g, showing two local maximum points within the specified range of (-5, 5) for both axes.

2. The Mathematical Complexities of GP Dynamics

Several key mathematical complexities arise from the dynamics of the GP search process:

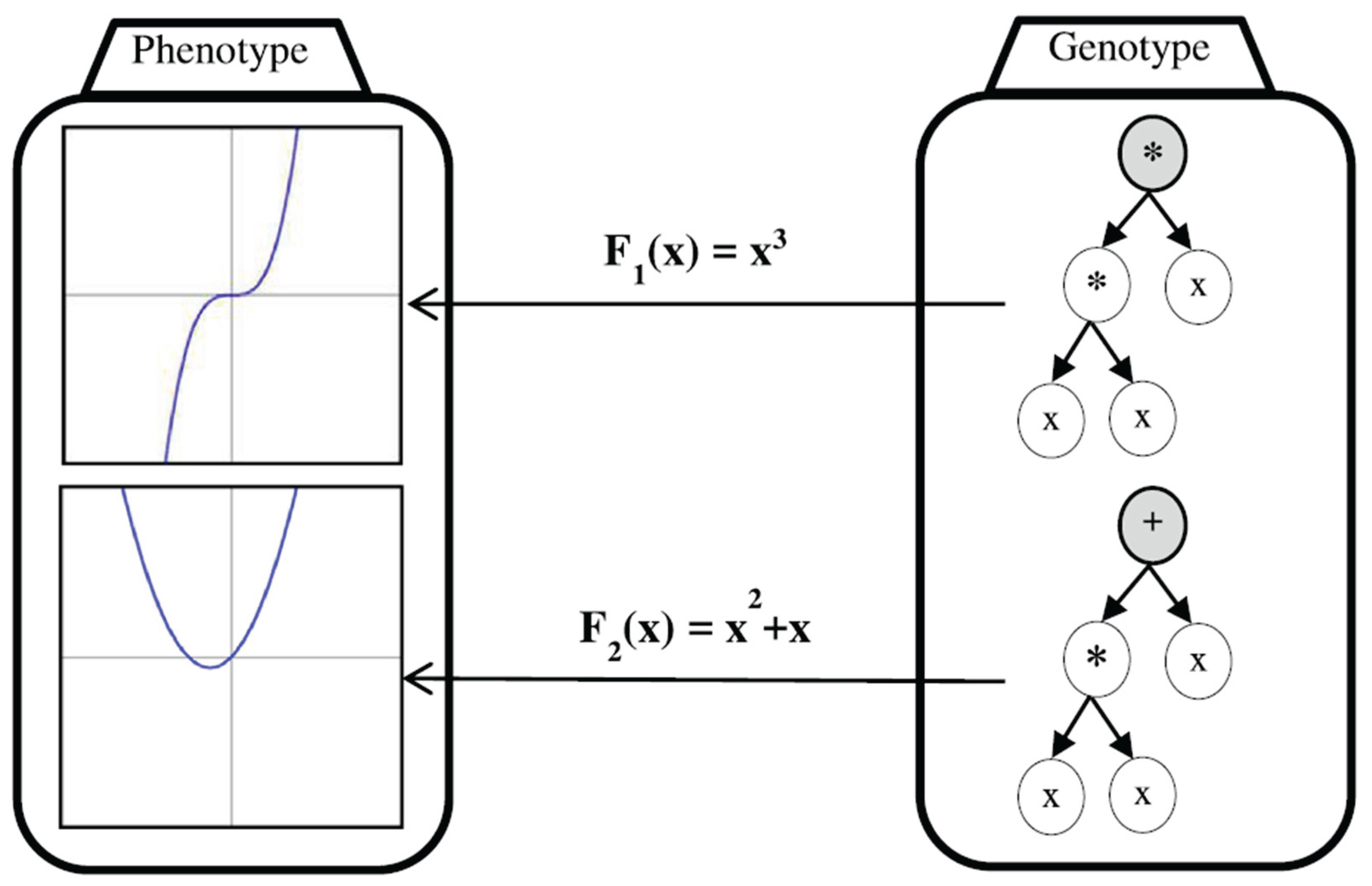

Schema Theory in Genetic Programming (Zojaji et al., 2022): The schema theory was one of the first theoretical frameworks for understanding evolutionary algorithms. It explains how low-order, highly fit building blocks (schemata) are transmitted and integrated to generate superior solutions. In typical genetic programming, the way programs are structured is deemed "non-local" since even minor modifications to a program can result in major changes in how it acts. This means that even a slight modification can result in an entirely different outcome, making it difficult to forecast how changes would affect overall performance. This non-locality is a challenge since it hampers the process of generating better solutions through incremental improvements.

In the example provided, a tree structure in genetic programming represents a mathematical function(Zojaji et al., 2022), specifically F

1(x) = x

3. When the multiplication symbol (*) at the root of this tree is changed to an addition symbol (+), the function changes to F

2(x) = x

2 + x, which is a very different equation despite the small change in the tree's structure. This illustrates how small modifications in genetic programming can lead to significant differences in meaning, highlighting the challenge of maintaining meaningful relationships between parts of the program during evolution, as in

Figure 12 (Zojaji et al., 2022).

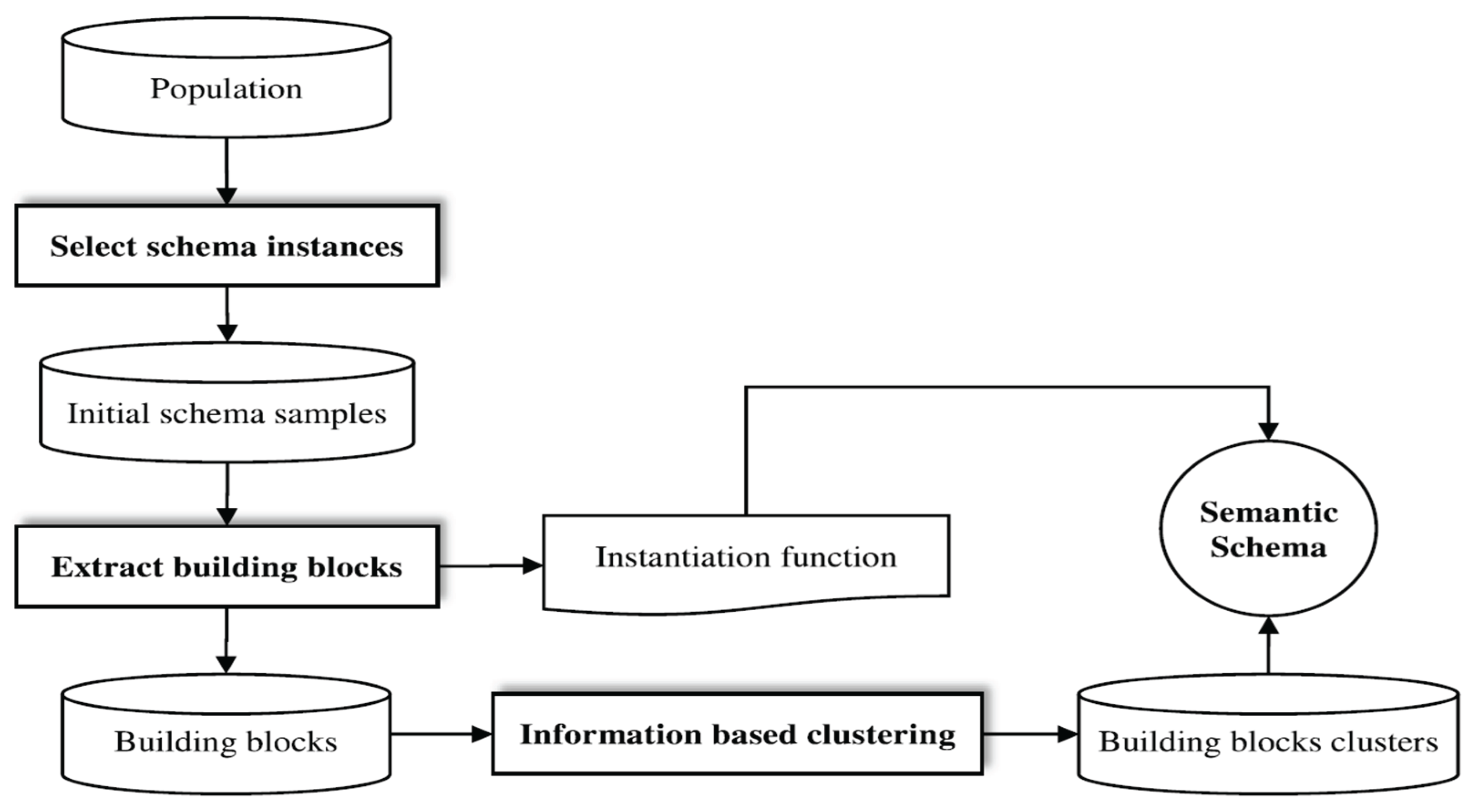

A semantic schema consists of two main parts: a group of important building blocks that represent meaningful components of solutions, and a function that helps describe how these building blocks are arranged within the overall solution(Zojaji et al., 2022). To extract the major schema, or significant schema, from a population in genetic programming, specific steps need to be followed. This process involves identifying patterns or structures within the population that represent common features or solutions(Zojaji et al., 2022). By analyzing these significant schemas, researchers can better understand how to improve the genetic programming process and enhance the effectiveness of finding optimal solutions, as

Figure 13 (Zojaji et al., 2022) reads.

In natural evolution(Zojaji et al., 2022), species can change over time due to factors like changes in gene frequencies, shifts in their environment, or mutations in their DNA. There are two main theories about how these changes happen: Phyletic Gradualism suggests that evolution occurs slowly and steadily(Zojaji et al., 2022), while Punctuated Equilibria proposes that changes happen suddenly and in bursts, often followed by long periods of stability. Both theories help explain how species adapt and evolve in response to their surroundings(Zojaji et al., 2022).

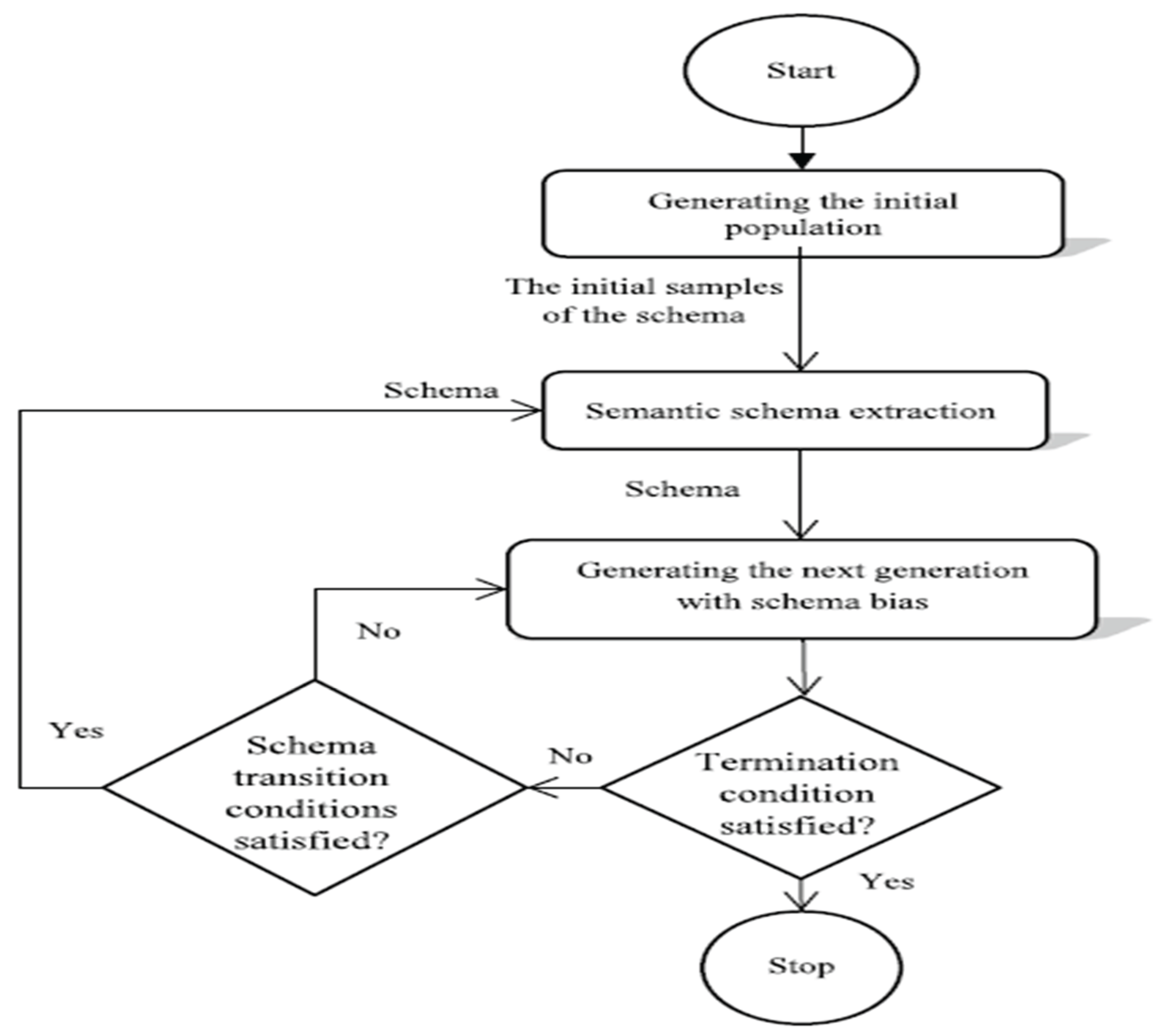

In the context of genetic programming, the statement refers to two different ways of influencing the search for solutions: implicit bias and explicit mutation. Implicit bias means that the algorithm naturally favors certain patterns or structures (schemas) in the search space, while explicit mutation involves actively changing these patterns to explore new possibilities. The flowchart (

Figure 14 (Zojaji et al., 2022)) mentioned as in below likely illustrates how these two approaches work together in the process of finding better solutions in genetic programming.

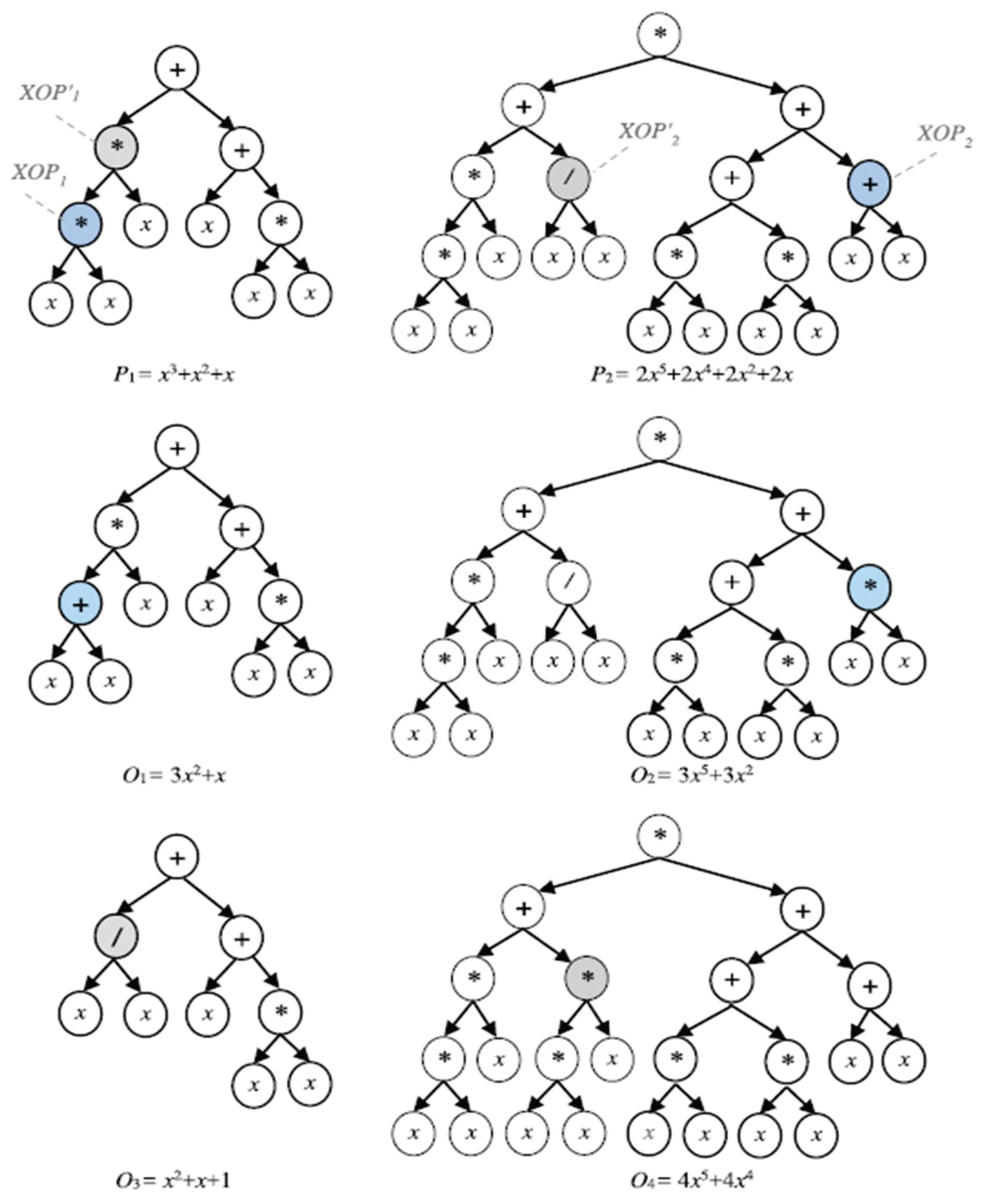

In this context, the visual example , showcased through

Figure 15 (Zojaji et al., 2022) illustrates how genetic programming can produce offspring (

O1 and

O2) that do not match a specific pattern or schema (

H) when unsuitable points are selected during the recombination process. This means that

O1 and

O2 are not meaningful solutions because they don't follow the structure defined by the schema(Zojaji et al., 2022) . In contrast(Zojaji et al., 2022) , when suitable points are chosen, the offspring (

O4) can successfully match the schema, making it a more relevant and potentially useful solution in the search for optimal answers.

However(Gong et al., 2024; Viswambaran et al., 2020), extending schema theory to GP has proven to be a formidable challenge. The traditional definition of a schema as a string with "don't care" symbols does not translate well to the tree-based representation of GP. While various GP-specific schema theories have been proposed(Gong et al., 2024; Viswambaran et al., 2020), they are often more complex and less predictive than their counterparts for fixed-length genetic algorithms. The destructive nature of standard crossover, which can easily disrupt beneficial building blocks, further complicates the analysis(Gong et al., 2024; Viswambaran et al., 2020).

Fitness Landscapes: Fitness landscape metaphorically visualizes the search process in GP, with program fitness determining height(Huang et al, 2025). Mathematical properties like ruggedness, neutrality (plateaus), and modality (local optima) significantly impact GP search performance(Huang et al, 2025). Analyzing these properties is mathematically challenging due to the high dimensionality and discrete nature of the program space(Huang et al, 2025).

Bloat: A well-known and persistent problem in GP is the tendency for programs to grow in size over successive generations without a corresponding improvement in fitness (Rimas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). This phenomenon, known as bloat, can lead to a significant increase in computational cost and can hinder the discovery of good solutions (Rimas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Several mathematical theories have been proposed to explain bloat, with many pointing to the protective nature of non-coding regions (introns) against the destructive effects of crossover(Rimas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). While various methods have been developed to control bloat, a complete and universally accepted mathematical theory of its causes and dynamics remains an active area of research(Rimas et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Convergence: Proving the convergence of GP to an optimal solution is another significant mathematical challenge(Langdon, 2022; Chen et al., 2025). Unlike some optimization algorithms for which rigorous convergence proofs exist, the stochastic and complex nature of GP makes such proofs difficult to obtain(Langdon, 2022; Chen et al., 2025). While some convergence results have been established under simplified assumptions, a general and practical convergence theory for GP is still lacking(Langdon, 2022; Chen et al., 2025)