Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

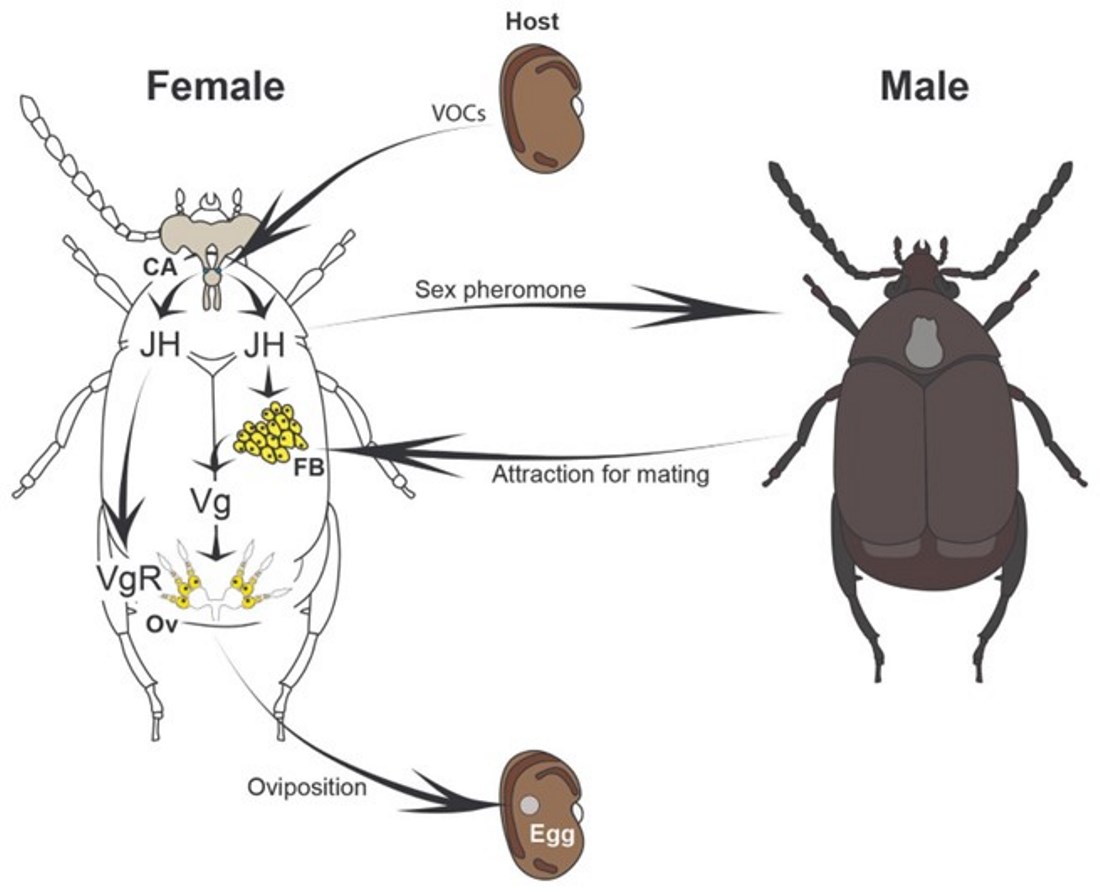

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Weevil Husbandry

2.2. Histological Processing of Pupal and Adult Ovaries

2.3. Experimental Group Allocation: Groups A, B, C, and D

2.3.1. Assessment of the Oviposition and Fecundity Profiles

2.3.2. Dissection of Adult Ovaries, Fluorescent Staining, and Scoring of Ovariole Activation

2.3.3. Quantification of Vitellogenic Genes Transcript Levels Using RT-qPCR

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

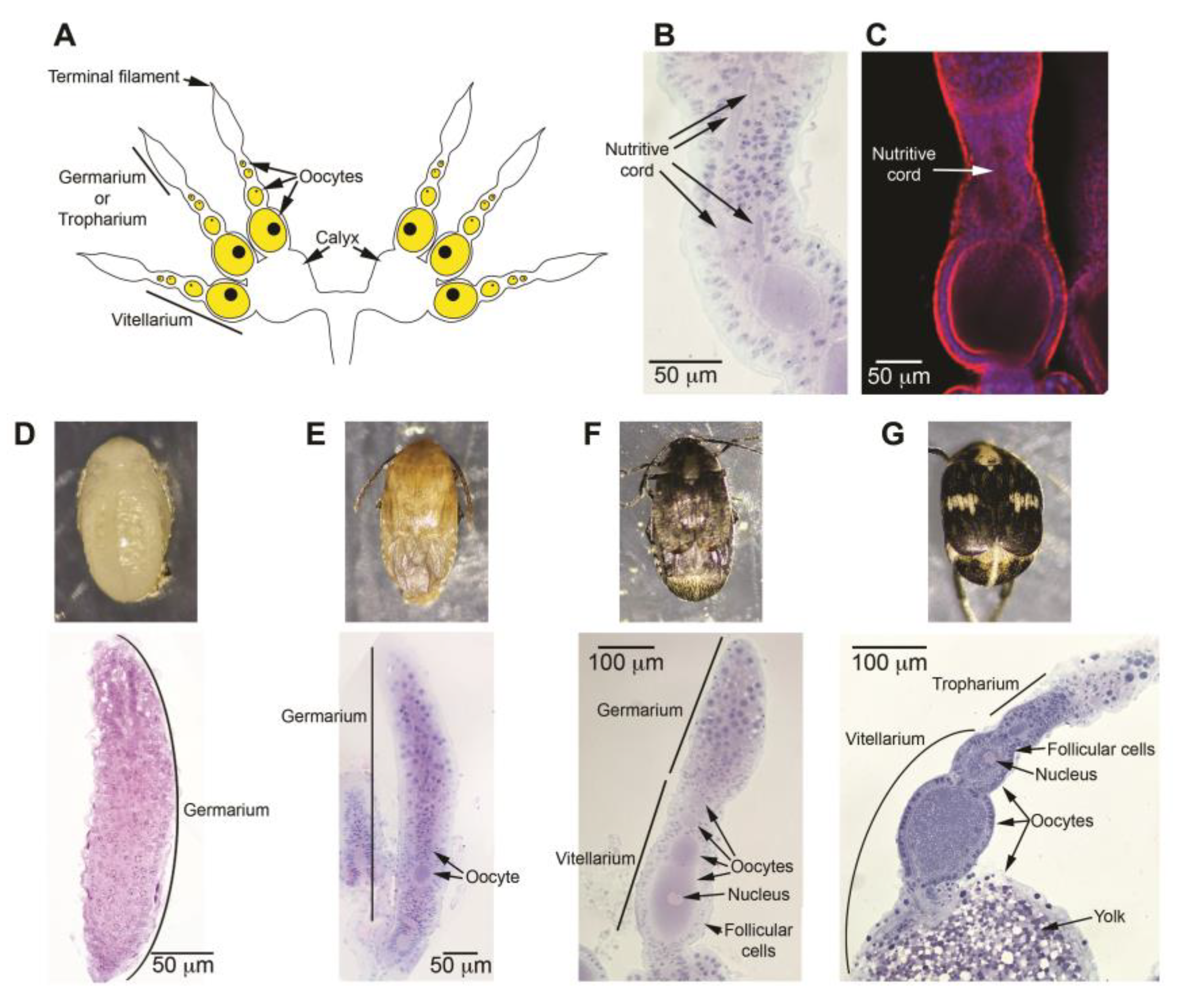

3.1. Female Zabrotes subfasciatus Begin Vitellogenesis During the Final Phases of Adult Development

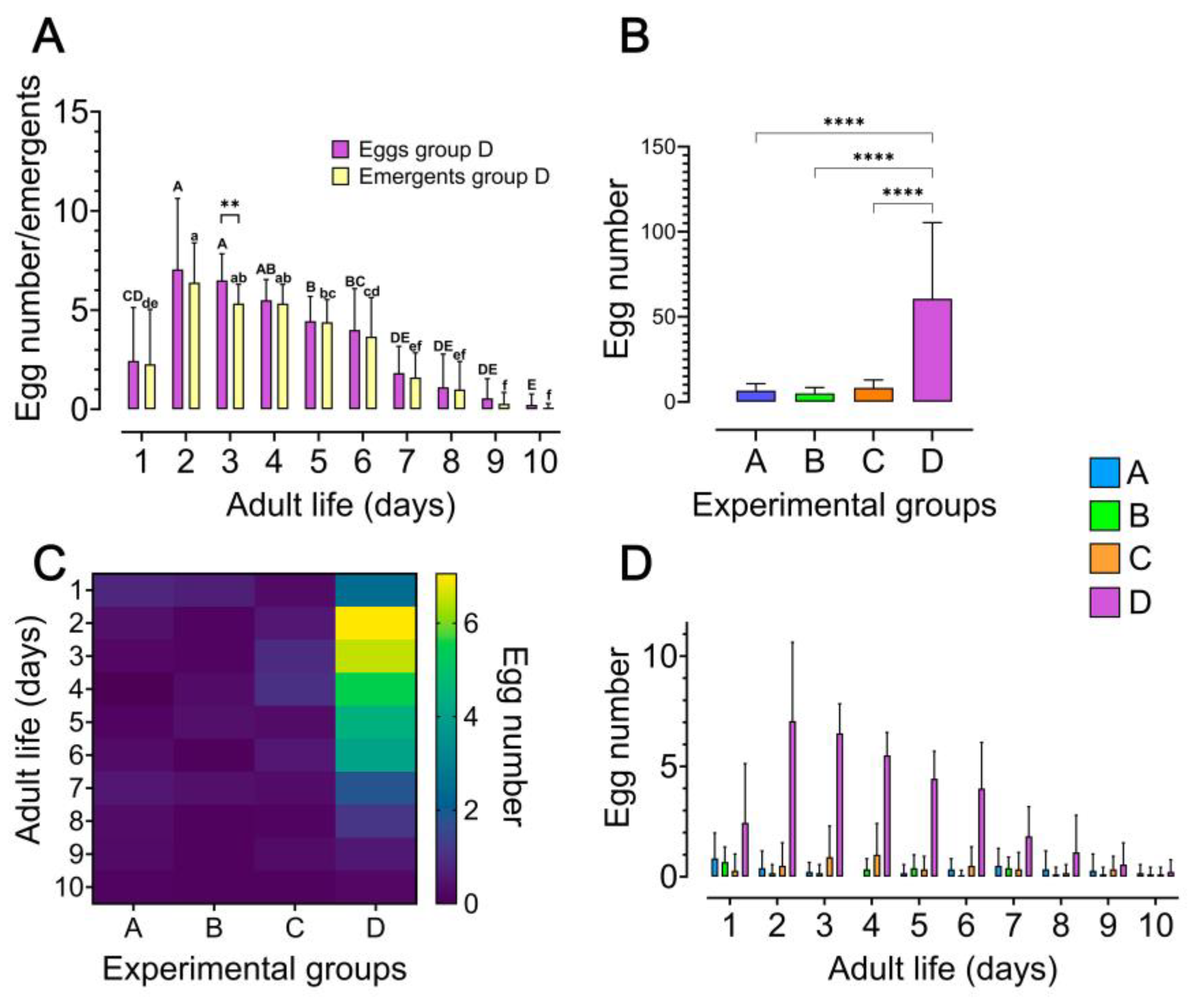

3.2. Oviposition in Zabrotes subfasciatus Begins Shortly After Adult Emergence and Is Enhanced by the Availability of Seeds and Males

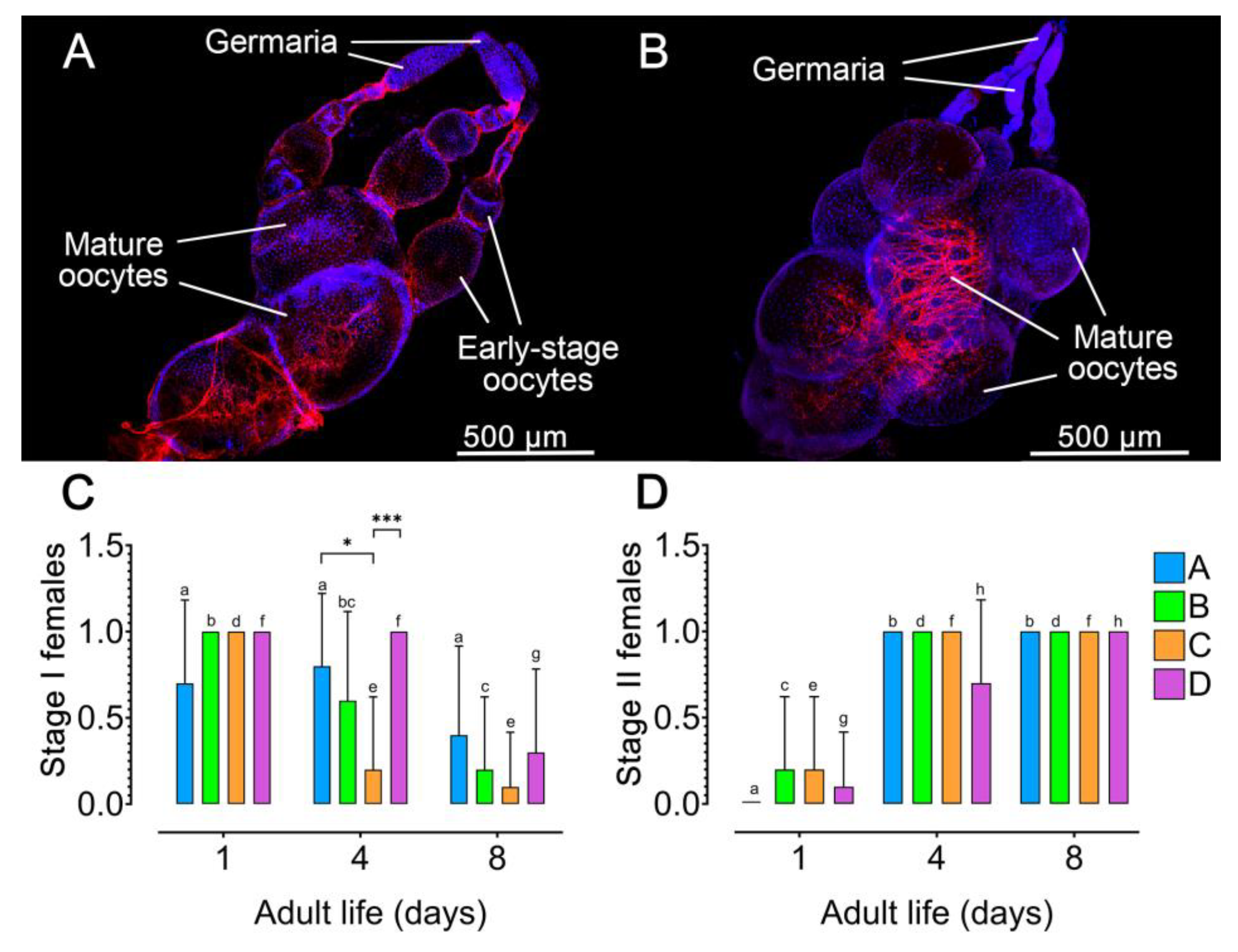

3.3. Vitellogenesis Is Elevated During the Early Phase of the Oviposition Period in Zabrotes subfasciatus, and Its Duration Is Extended by the Presence of Seeds and Males

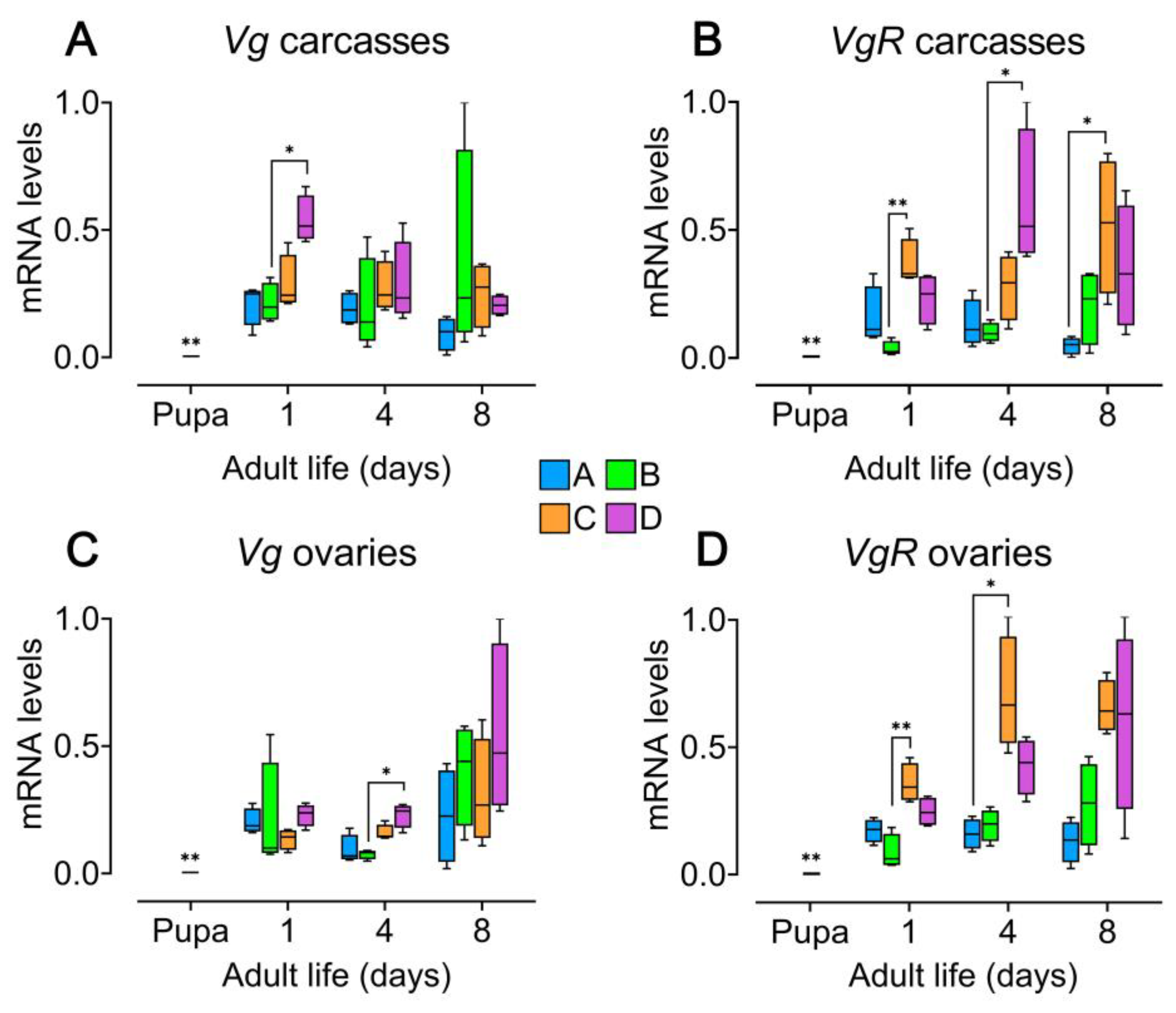

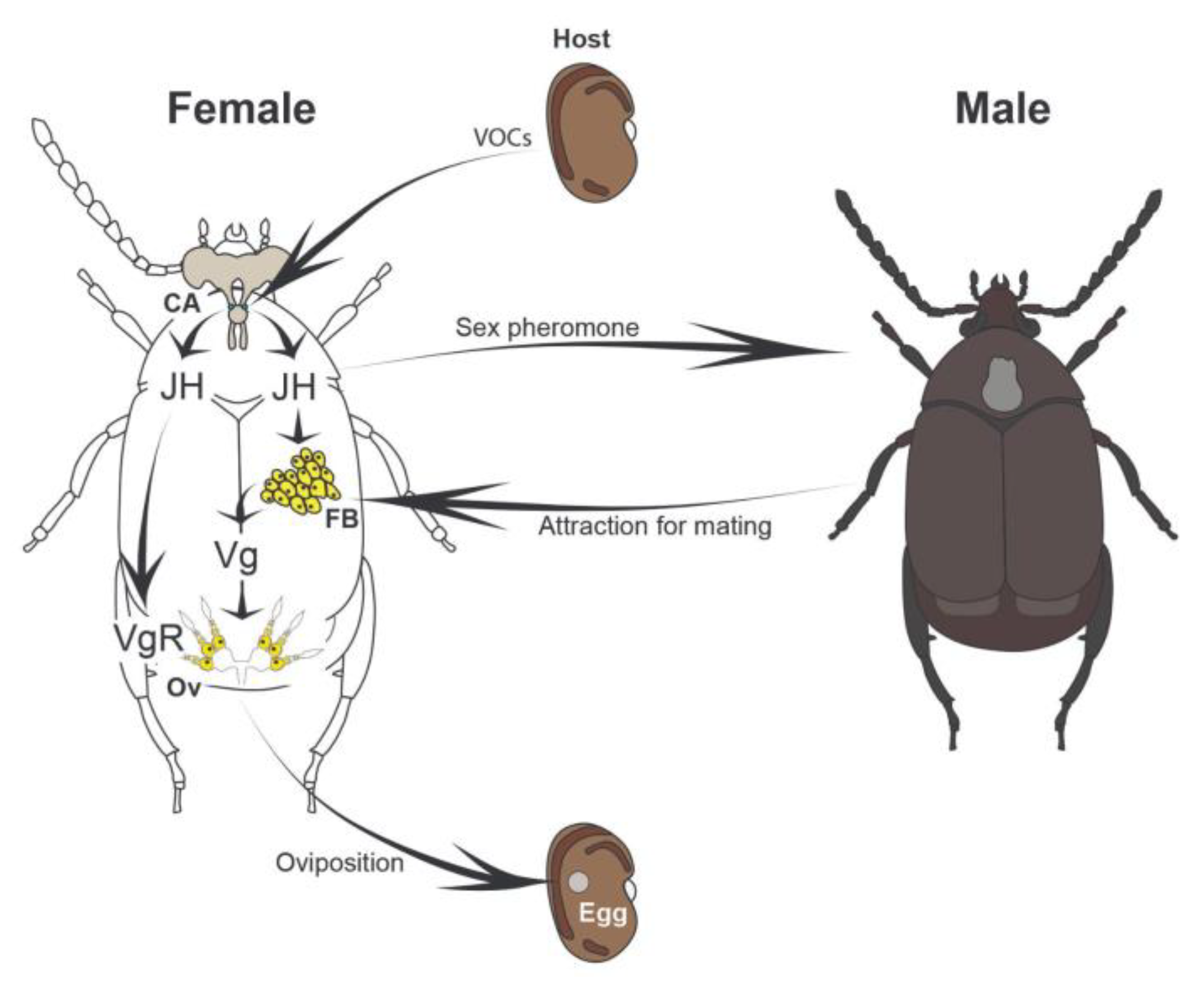

3.4. Male Presence Enhances Vitellogenin (vg) Expression, While Seeds Boost Vitellogenin Receptor (vgR) Expression in the Ovaries of Zabrotes subfasciatus Females

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawrence, J.F. Coleoptera. In Synopsis and Classification of Living Organism; Parker, S.P., Ed.; MacGraw-Hill, 1982; Vol. 2, pp. 482–553.

- McKenna, D.D.; Shin, S.; Ahrens, D.; Balke, M.; Beza-Beza, C.; Clarke, D.J.; Donath, A.; Escalona, H.E.; Friedrich, F.; Letsch, H.; et al. The Evolution and Genomic Basis of Beetle Diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 24729–24737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, D.D.; Scully, E.D.; Pauchet, Y.; Hoover, K.; Kirsch, R.; Geib, S.M.; Mitchell, R.F.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ahn, S.-J.; Arsala, D.; et al. Genome of the Asian Longhorned Beetle (Anoplophora Glabripennis), a Globally Significant Invasive Species, Reveals Key Functional and Evolutionary Innovations at the Beetle–Plant Interface. Genome Biology 2016, 17, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, G. Bruchinae Latereille. In Arthropoda: Insecta: Coleoptera.; Handbook of Zoology; Vol. 3, pp. 189–197.

- Johnson, C.D. Seed Beetle Host Specificity and the Systematics of the Leguminosae. In Advances in Legume Systematics Part 2; Ponhill, R.M., Ed.; 1981.

- Southgate, B.J. Biology of the Bruchidae. Ann. Rev. Entomol 1979, 24, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsolver, J.M. Handbook of the Bruchidae of the United States and Canada; United States Department of Agriculture, 2004.

- Diamond, J. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies; W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

- Tuda, M. Evolutionary Diversification of Bruchine Beetles: Climate-Dependent Traits and Development Associated with Pest Status. Bulletin of Entomological Research 2011, 101, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, C.P.; Parreiras, S.S.; Beijo, L.A.; Ávila, P.M. de; Teixeira, I.R.V.; Barchuk, A.R. Life History Trait Response to Ambient Temperature and Food Availability Variations in the Bean Weevil Zabrotes subfasciatus. Physiological Entomology 2021, 46, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, Á.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. Losses in the Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimbert, M. A Model of Host Plant Change of Zabrotes subfasciatus Boh. (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in a Traditional Bean Cropping System in Costa Rica. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture 1985, 3, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimbert, M. Reproduction and Oviposition Preferences of Zabrotes subfasciatus Stocks Reared from Two Host Plant Species. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1985, 38, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.W. The Effect of Inbreeding on Natural Selection in a Seed-feeding Beetle. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2013, 26, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.W.; Waddell, K.J.; Mousseau, T.A. Host-Associated Fitness Variation in a Seed Beetle (Coleoptera: Bruchidae): Evidence for Local Adaptation to a Poor Quality Host. Oecologia 1994, 99, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, A.; Barrio, A.M.; Immonen, E.; Dainat, J.; Berger, D.; Tellgren-Roth, C.; Nystedt, B.; Arnqvist, G. The Genomic Footprint of Sexual Conflict. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2019, 3, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.R. do V. ; Beijo, L.A.; Barchuk, A.R. Behavioral and Physiological Responses of the Bean Weevil Zabrotes subfasciatus to Intraspecific Competition. Journal of Stored Products Research 2016, 69, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.P.; Dias, R.O.; Ferreira, C.; Silva, C.P.; Terra, W.R. Histochemistry and Transcriptomics of Mucins and Peritrophic Membrane (PM) Proteins along the Midgut of a Beetle with Incomplete PM and Their Complementary Function. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2023, 162, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.P.; Terra, W.R.; Sá, M.F.G. de; Samuels, R.I.; Isejima, E.M.; Bifano, T.D.; Almeida, J.S. Induction of Digestive α-Amylases in Larvae of Zabrotes subfasciatus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Response to Ingestion of Common Bean α-Amylase Inhibitor 1. Journal of Insect Physiology 2001, 47, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, B. de O.; Miranda, S. de O.; Benedito, E.R.C.; Martins, J.R.; Beijo, L.A.B.; Nogueira, E.S.C.; Mazzoni, T.S.; Moda, L.M.R.; Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Barchuk, A.R. Early Adaptation to an Unusual Host in the Bean Weevil Zabrotes subfasciatus Is Associated with Changes in Body Size and Reproductive Physiology. Physiological Entomology 2025.

- Rodrigues, P.A. da P.; Martins, J.R.; Capizzani, B.C.; Hamasaki, L.T.A.; Simões, Z.L.P.; Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Barchuk, A.R. Transcriptional Signature of Host Shift in the Seed Beetle Zabrotes subfasciatus. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Barchuk, A.R.; Zucoloto, F.S. Host Preference of the Bean Weevil Zabrotes subfasciatus. Insect Science 2008, 15, 335–341. [CrossRef]

- Love, A.C.; Yoshida, Y. Reflections on Model Organisms in Evolutionary Developmental Biology. In; 2019; pp. 3–20.

- Valencia, C.A.; Mejía, C.C.; Schoonhoven, A. van Main Insect Pests of Stored Beans and Their Control [Tutorial Unit].; Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), 1986.

- Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Gris, C.F. Genetic Diversity of Grains, Storage Pests and Their Effects on the Worldwide Bean Supply. In Beans: Nutrition, Consumption and Health; Popescu, E., Golubev, I., Eds.; 2011.

- Boheman, C.H. Genera et Species Curculionidum, Cum Synonymia Hujus Familiae; Schoenherr, C.J., Ed.; Synonymia insectorum, oder: Versuch einer Synonymie aller bisher bekannten Insecten; nach Fabricii Systema Eleutheratorum &c. geordnet; Roret: Paris, France, 1833.

- Lucas, M.H. Spermophagus Semifasicatus. In Proceedings of the Bulletins trimestriels de la Société Entomologique de France; Annales de la Société Entomologique de France, 1858.

- Corrêa, C.P.; Capizzani, B.C.; Beijo, L.A.; Ávila, P.M. de; Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Barchuk, A.R. Adult Feeding and Host Type Modulate the Life History Traits of the Capital Breeder Zabrotes subfasciatus. Physiological Entomology 2020, 45, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meik, J.; Dobie, P. The Ability of Zabrotes subfasciatus to Attack Cowpeas. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1986, 42, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.R.V.; Zucoloto, F.S. Seed Suitability and Oviposition Behaviour of Wild and Selected Populations of Zabrotes subfasciatus (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) on Different Hosts. Journal of Stored Products Research 2003, 39, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodin, J. She Shapes Events as They Come: Plasticity in Female Insect Reproduction. In Phenotypic Plasticity of Insects: Mechanisms and Consequences; Science Publishers: Enfield, NH, USA, 2009; pp. 423–521. [Google Scholar]

- Soller, M.; Bownes, M.; Kubli, E. Control of Oocyte Maturation in Sexually Mature Drosophila Females. Developmental Biology 1999, 208, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; He, Q.; Zhou, S. Regulatory Mechanisms of Vitellogenesis in Insects. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyria, J. Endocrine Factors Modulating Vitellogenesis and Oogenesis in Insects: An Update. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2024, 587, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delobel, A. Effect of Groundnut Pods (Arachis hypogaea) and Imaginal Feeding on Oogenesis, Mating and Oviposition in the Seed Beetle, Caryedon Serratus. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1989, 52, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouzat, J.; Bilal, H.; Nammour, D.; Pimbert, M. A Comparative Study of the Host Plant’s Influence on the Sex Pheromone Dynamics of Three Bruchid Species. Acta Oecologica, Oecologia Generalis 1989, 10, 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Papaj, D.R. Ovarian Dynamics and Host Use. Annual Review of Entomology 2000, 45, 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimbert, M.; Pouzat, J. Electroantennogram Responses of Zabrotes subfasciatus to Odours of the Sexual Partner. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1988, 47, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.M.J.; Credland, P.F. Determinants of Oviposition in Acanthoscelides obtectus: A Nonconformist Bruchid. Physiological Entomology 2003, 28, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analysis in a Tubular Olfactometer of the Influence of Different Olfactory Stimuli on the Search for a Sexual Partner by Zabrotes subfasciatus. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1987.

- Pimbert, M.; Pierre, D. Ecophysiological Aspects of Bruchid Reproduction: The Influence of Pod Maturity and Seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris and the Influence of Insemination on the Reproductive Activity of Zabrotes subfasciatus. Ecological Entomology 1983, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, E.M.; Boake, C.R.B. Onset of Vitellogenesis in Female Drosophila silvestris Is Accelerated in the Presence of Sexually Mature Males. Journal of Insect Physiology 1992, 38, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boake, C.R.B.; Moore, S. Male Acceleration of Ovarian Development in Drosophila silvestris (Diptera, Drosophilidae): What Is the Stimulus? Journal of Insect Physiology 1996, 42, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.A.; Norman, V.C.; Rouse, J.L.; Duncan, E.J. Environmentally Responsive Reproduction: Neuroendocrine Signalling and the Evolution of Eusociality. Current Opinion in Insect Science 2022, 53, 100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Teal, P.E.A.; Sivinski, J.; Dueben, B.D. Influence of Male Presence on Sexual Maturation in Female Caribbean Fruit Fly, Anastrepha suspensa (Diptera: Tephritidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 2006, 19, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, S.T. Juvenile Hormone-Mediated Reproduction in Burying Beetles: From Behavior to Physiology. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 1997, 35, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, S.T.; Borst, D.W.; Robinson, G.E. Rapid Elevation of Juvenile Hormone Titer during Behavioral Assessment of the Breeding Resource by the Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus orbicollis. Journal of Insect Physiology 1995, 41, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouzat, J. Host Plant Chemosensory Influence on Oogenesis in the Bean Weevil Acanthoscelides obtectus (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1978, 24, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-L.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zheng, X.-L.; Lu, W. Research Progress on Oviposition-Related Genes in Insects. Journal of Insect Science 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.A. de; Carvalho, M.R. de O.; Martins, E.R.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Oliveira, L.O. de Diversidade Genética Estimada Com Marcadores ISSR Em Populações Brasileiras de Zabrotes subfasciatus. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 2008, 43, 843–849. [CrossRef]

- Bondar, G.G. Notas Biologicas Sobre Bruchideros Observados No Brasil. Tip. do Jornal do Commercio 1937.

- Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Barchuk, A.R.; Medeiros, L.; Zucoloto, F.S. Females of the Weevil Zabrotes subfasciatus Manipulate the Size and Number of Eggs According to the Host Seed Availability. Physiological Entomology 2009, 34, 246–250. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.R.V.; Zucoloto, F.S. Intraspecific Competition in Zabrotes subfasciatus: Physiological and Behavioral Adaptations to Different Amounts of Host. Insect Science 2012, 19, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnovsky, M.J. A Formaldehyde Glutaraldehyde Fixative of High Osmolality for Use in Electron Microscopy. The Journal of Cell Biology 1965, 27, 1A–149A. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, H.F. On the Rapid Conversion of Haematoxylin into Haematein in Staining Reactions. Journal of Applied Microscopic Laboratory Methods 1900, 3, 777. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, R.W.; Currie, J.E. Some Laboratory Observations on the Rates of Development, Mortality and Oviposition of Several Species of Bruchidae Breeding in Stored Pulses. Bulletin of Entomological Research 1964, 55, 437–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendy, J.; Credland, P.F. Development, Fecundity and Egg Dispersion of Zabrotes subfasciatus. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1991, 59, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A. da; Farder-Gomes, C.F.; Barchuk, A.R.; Malaspina, O.; Nocelli, R.C.F. Sublethal Exposure to Thiamethoxam and Pyraclostrobin Affects the Midgut and Malpighian Tubules of the Stingless Bee Frieseomelitta varia (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini). Ecotoxicology 2024, 33, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GraphPad Software. GraphPad Prism, Version 10.5.0; GraphPad Software: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.graphpad.com/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Sappington, T.W.; Raikhel, A.S. Molecular Characteristics of Insect Vitellogenins and Vitellogenin Receptors. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 1998, 28, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klowden, M.J.; Pallai, S.R. Physiological Systems in Insects; Fourth edition.; Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier: London ; San Diego, CA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-12-820359-0.

- Mohamed, M.I.; Khaled, A.S.; Fattah, H.M.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Salem, D.A.M.; Fawki, S. Ultrastructure and Histopathological Alteration in the Ovaries of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) Induced by the Solar Radiation. The Journal of Basic & Applied Zoology 2015, 68, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.K. Morphological and Histochemical Studies on Oogenesis in Callosobruchus analis Fabr. (Bruchidae-Coleoptera). Journal of Morphology 1967, 122, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büning, J. The Telotrophic Nature of Ovarioles of Polyphage Coleoptera. Zoomorphologie 1979, 93, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büning, J. Ovariole Structure Supports Sistergroup Relationship of Neuroptera and Coleoptera. ASP 2006, 64, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belles, X.; Piulachs, M.-D. Ecdysone Signalling and Ovarian Development in Insects: From Stem Cells to Ovarian Follicle Formation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2015, 1849, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, K.I.; Jonsson, K.I. Capital and Income Breeding as Alternative Tactics of Resource Use in Reproduction. Oikos 1997, 78, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katvala, M.; Rönn, J.L.; Arnqvist, G. Correlated Evolution between Male Ejaculate Allocation and Female Remating Behaviour in Seed Beetles (Bruchidae). Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2008, 21, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailly, T.P.M.; Kohlmeier, P.; Etienne, R.S.; Wertheim, B.; Billeter, J.-C. Social Modulation of Oogenesis and Egg Laying in Drosophila melanogaster. Current Biology 2023, 33, 2865–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat-Canals, M.; Schnelle, K.; Leipart, V.; Halskau, Ø.; Amdam, G.V.; Moeller, A.; Cunha, E.S.; Luecke, H. Cryo-EM Structure of Native Honey Bee Vitellogenin. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; He, S.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. Characterization of a Vitellogenin Receptor in the Bumblebee, Bombus lantschouensis (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Insects 2019, 10, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.C.A.; Valle, D.; Machado, E.A.; Salerno, A.P.; Paiva-Silva, G.O.; Silva, N.L.C.E.; Souza, W. de; Masuda, H. Synthesis of Vitellogenin by the Follicle Cells of Rhodnius prolixus. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2000, 30, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonbaum, C.P.; Perrino, J.J.; Mahowald, A.P. Regulation of the Vitellogenin Receptor during Drosophila melanogaster Oogenesis. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2000, 11, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Takeda, M. Molecular Cloning, Characterization and Regulation of the Cockroach Vitellogenin Receptor during Oogenesis. Insect Molecular Biology 2005, 14, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, L.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Bai, L. Vitellogenin and Vitellogenin Receptor Gene Expression Profiles in Spodoptera exigua Are Related to Host Plant Suitability. Pest Management Science 2018, 74, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capizzani, B.C.; Rainho, H.L.; Miranda, S. de O.; Rosa, V.D. de S.; Beijo, L.A.; Teixeira, I.R. do V.; Bento, J.M.; Barchuk, A.R. Contrasting Responses to Ethenylbenzene (Styrene) and 2-Ethyl-1-Hexanol Suggest Their Role as Chemical Cues in Host Selection by the Seed Beetle Zabrotes subfasciatus (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae). Neotropical Entomology 2024, 54, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, S. Juvenile Hormone Studies in Drosophila melanogaster. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).