Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

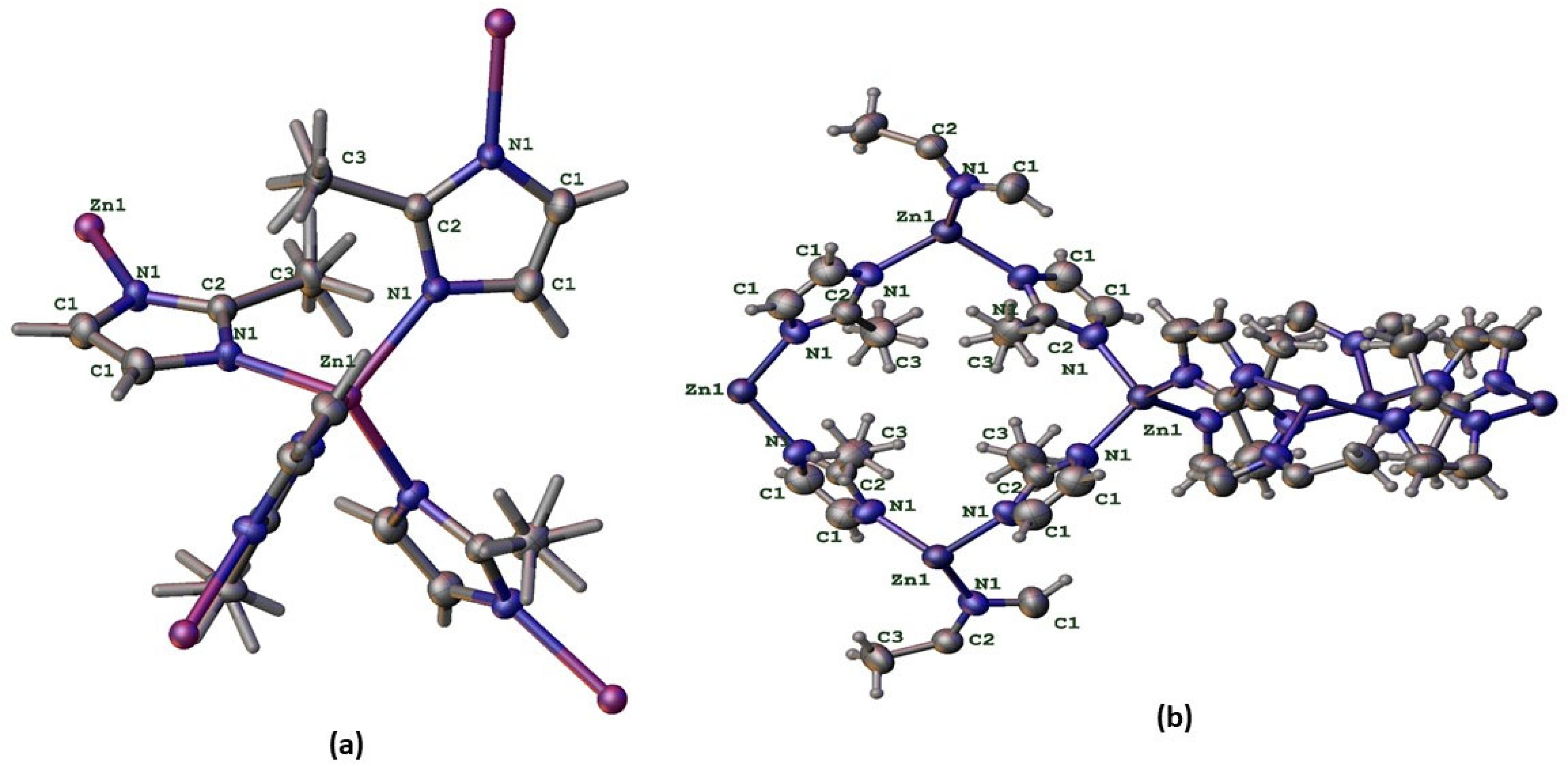

2.1. Crystallographic Results

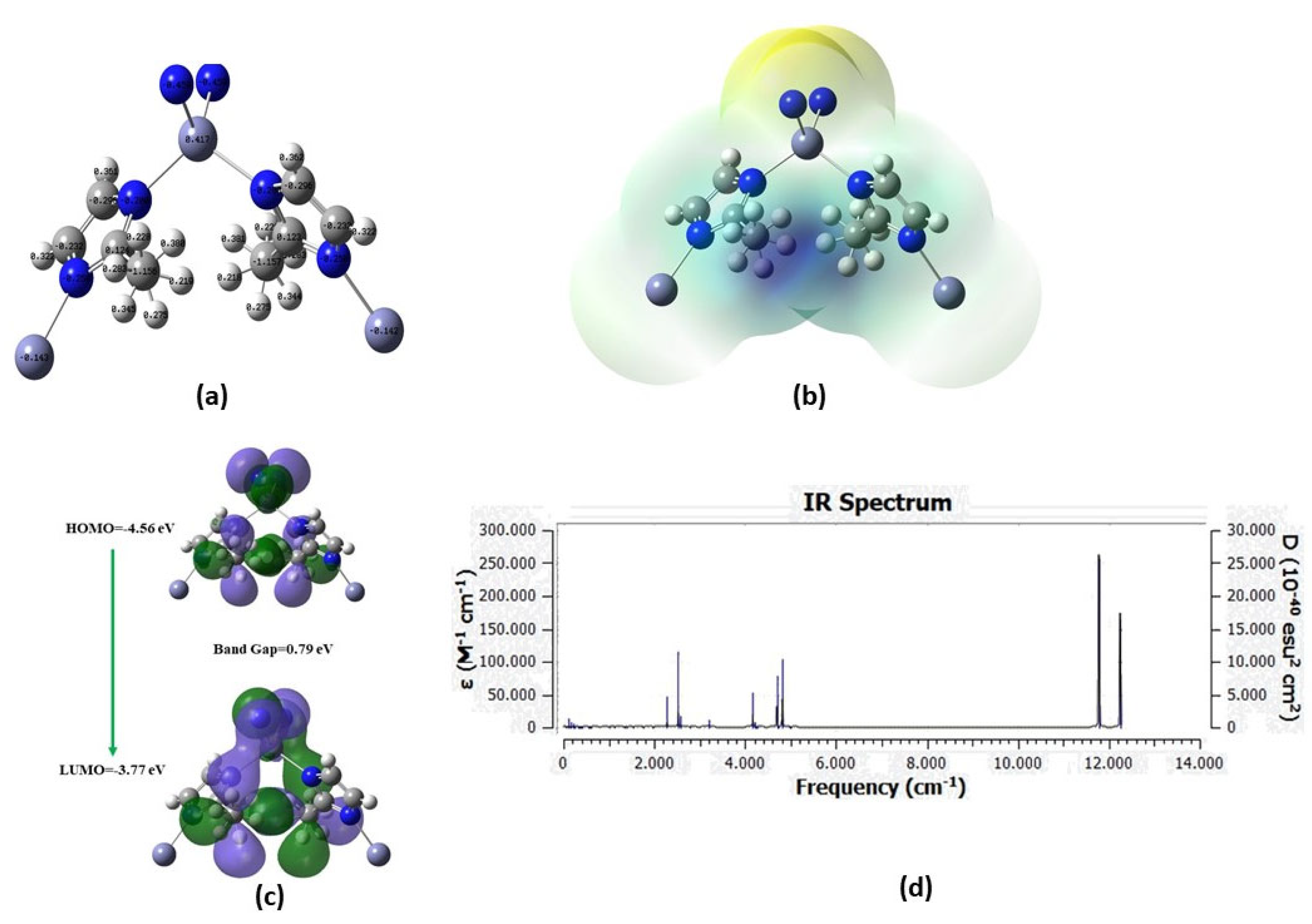

2.2. Theoretical Results

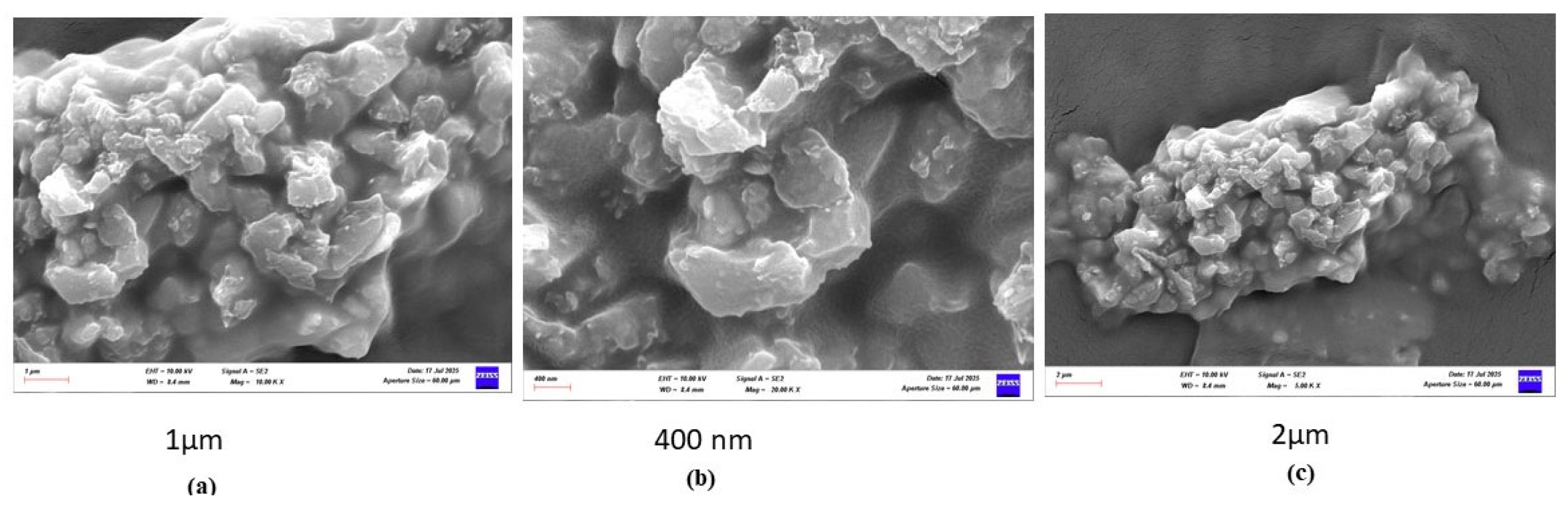

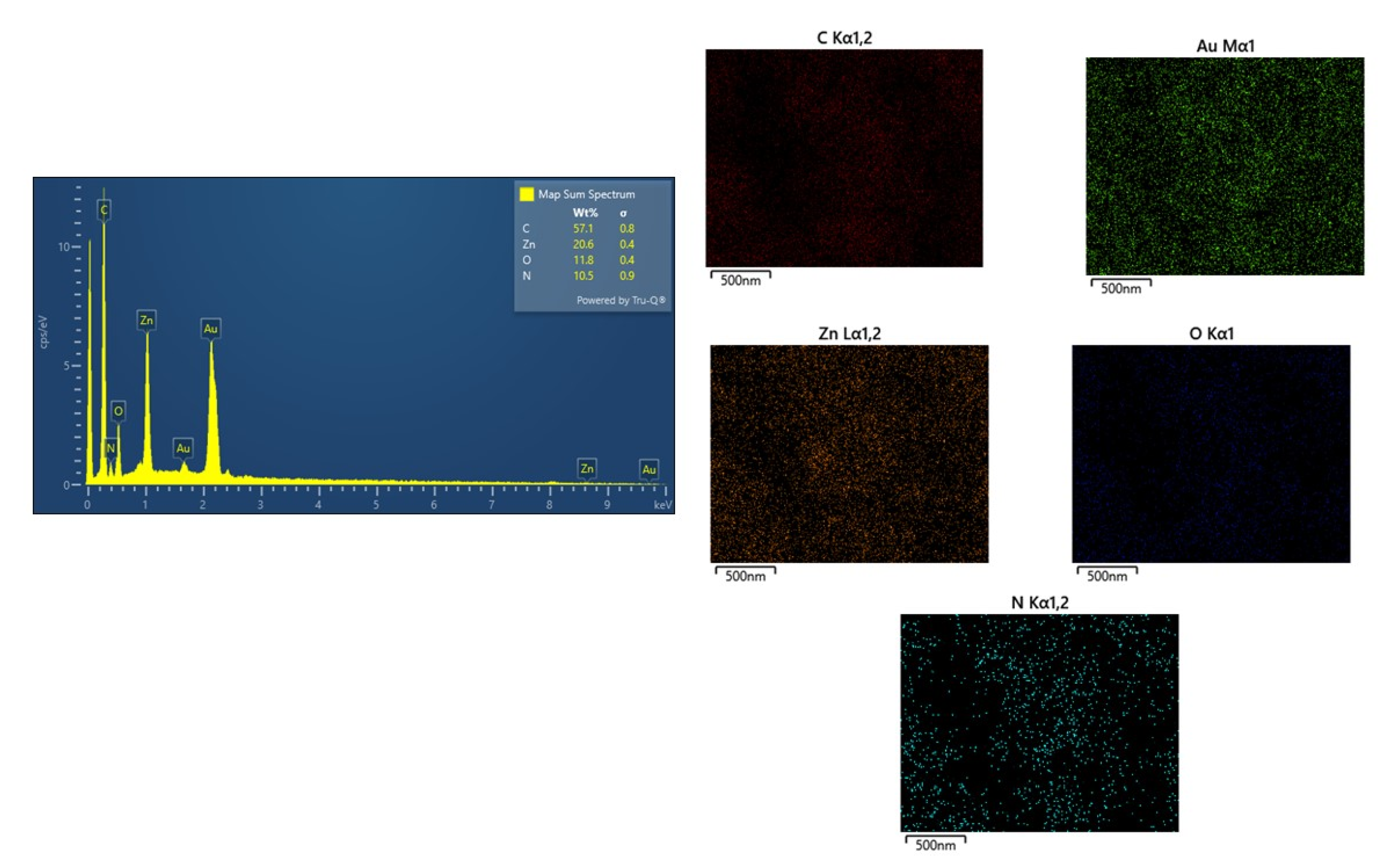

2.3. SEM-Based Surface Topography and Morphology

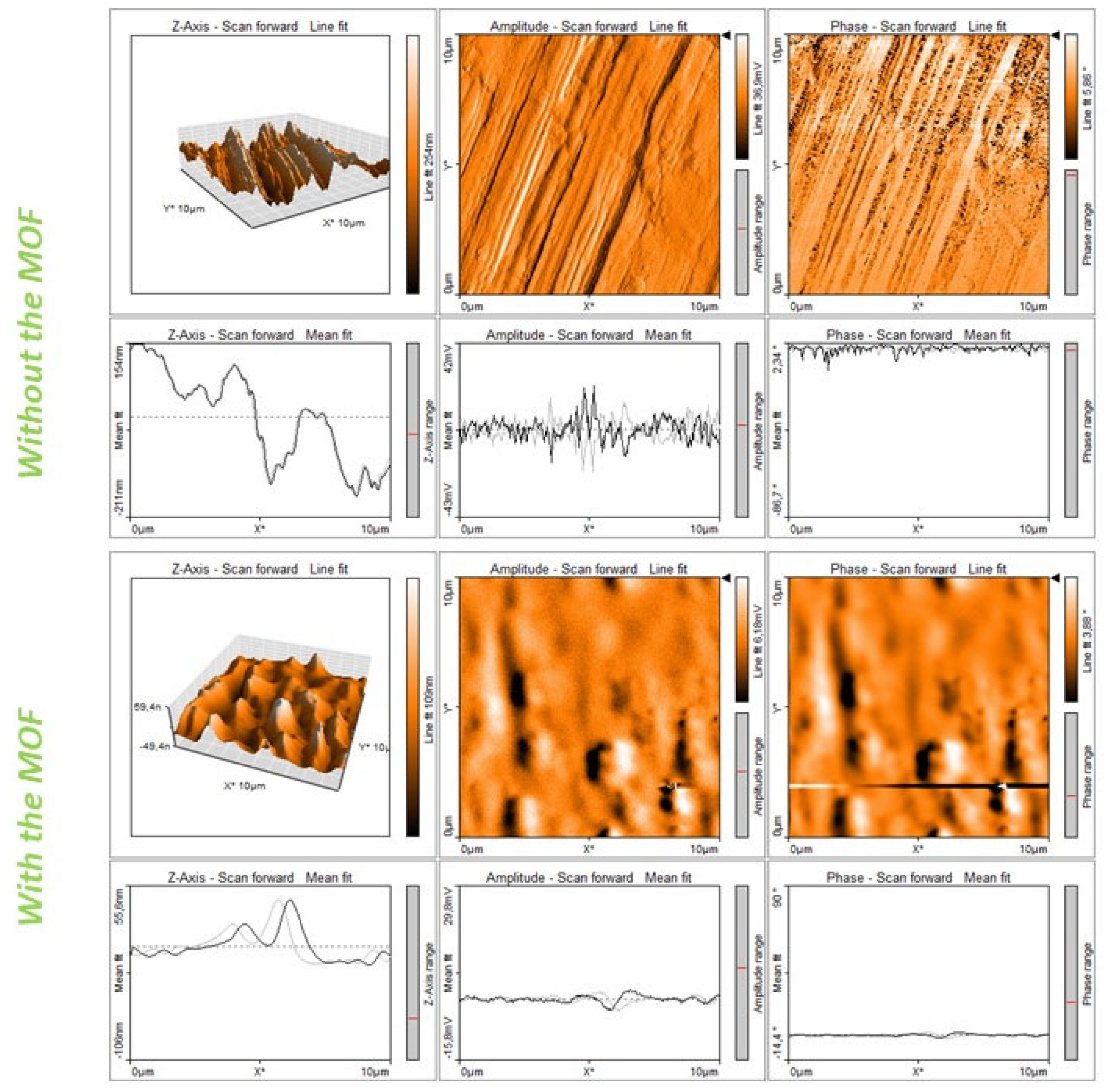

2.4. AFM-Based Surface Topography and Morphology

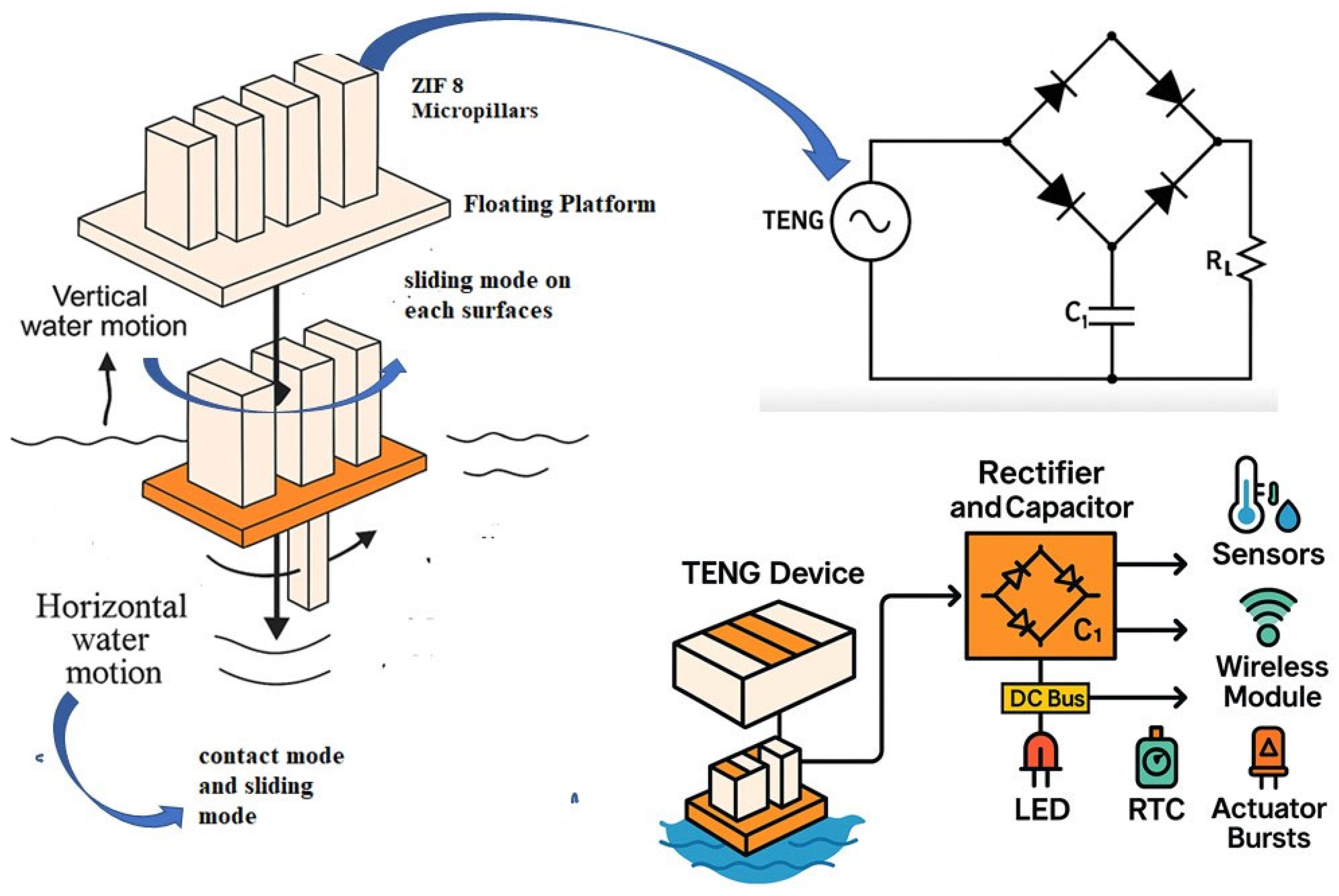

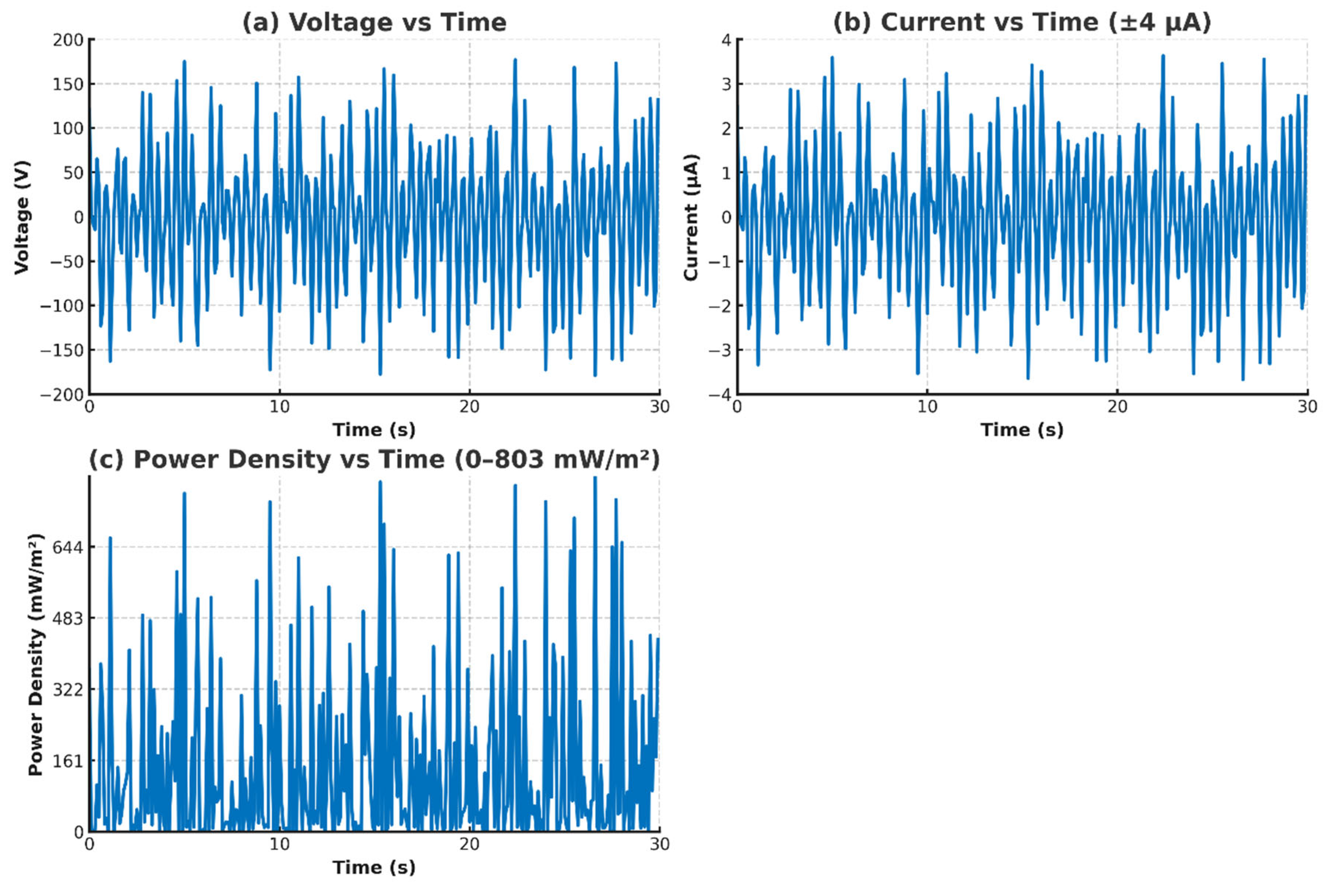

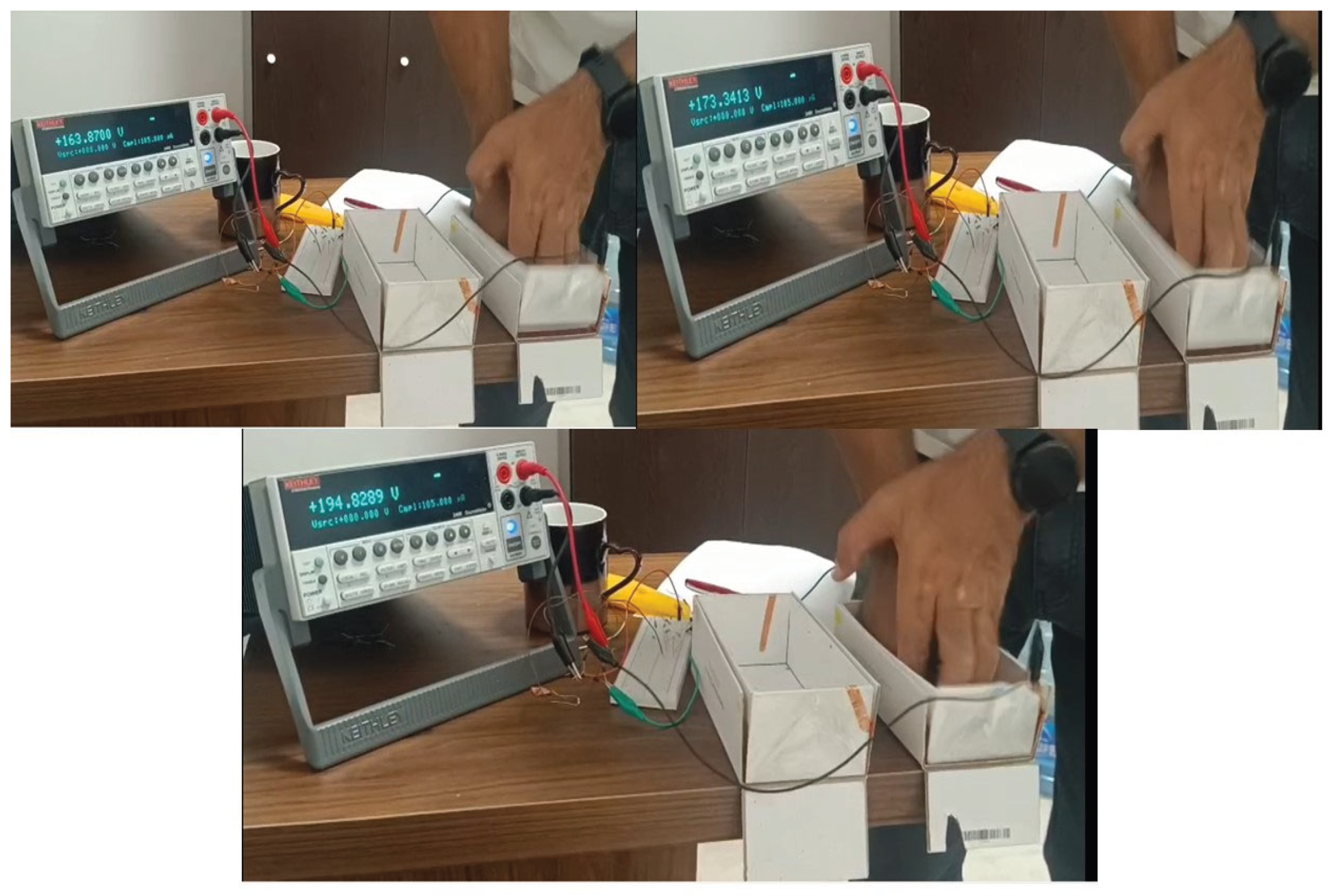

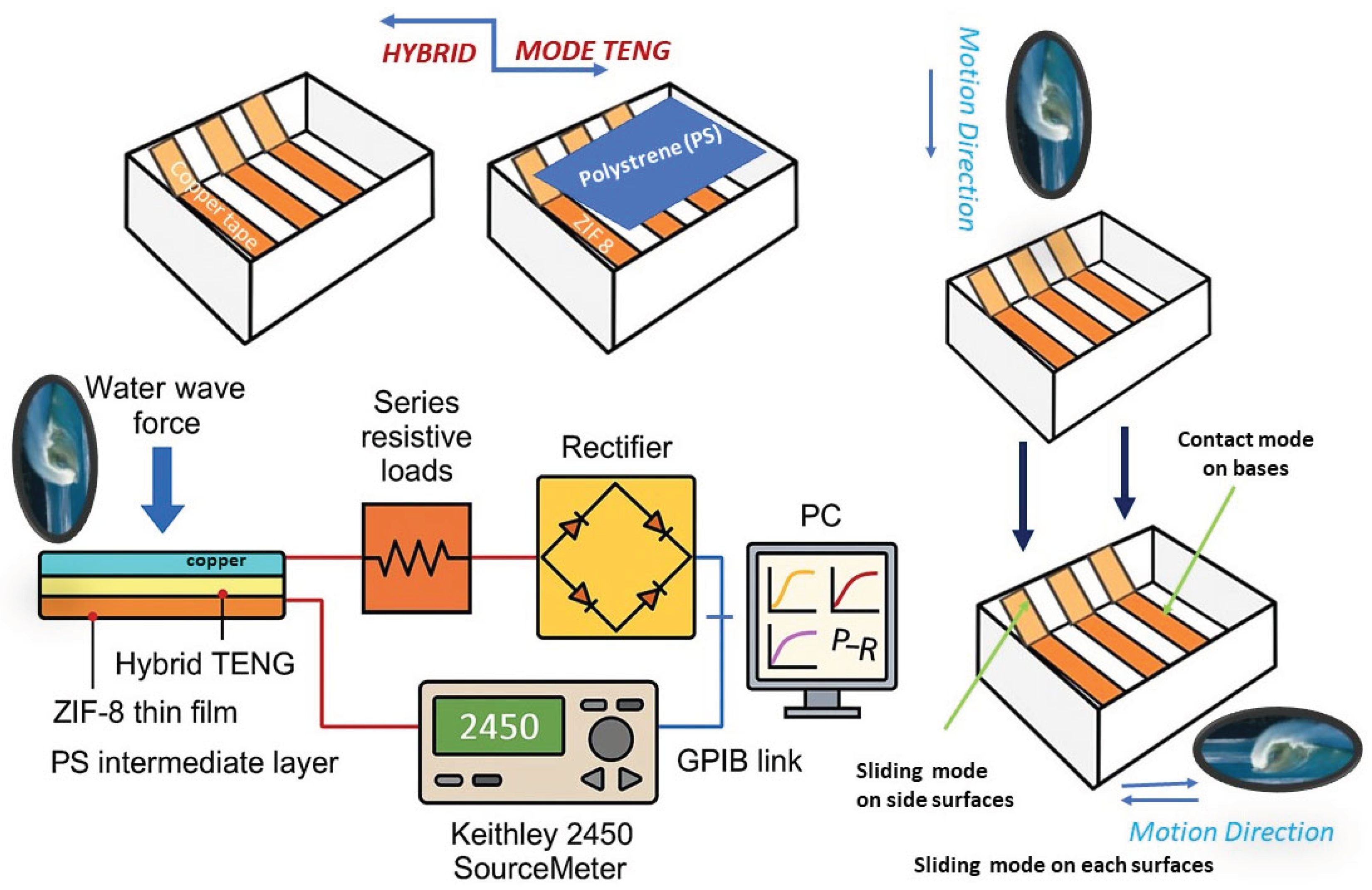

2.5. Electrical Output Performance of the Polystyrene Hybrid-Mode TENG with Dual Copper Electrodes

3. Experimental Section

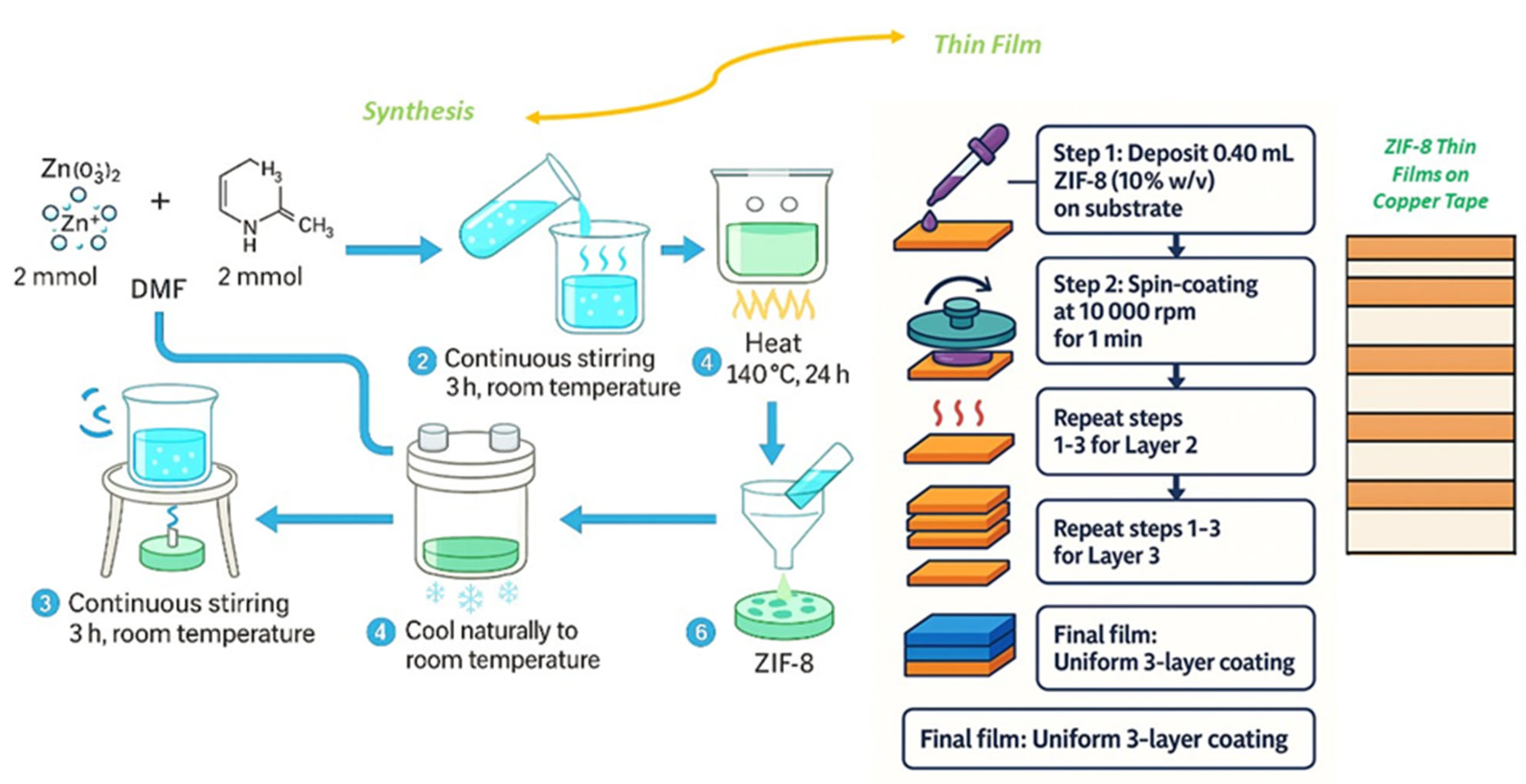

3.1. Synthesis, Thin Film Preperation and Characterization of ZIF-8 on Copper Tape

3.2. Thin Film Preperation

3.3. Single Crystal X-Ray Crystallography

3.4. Scanning electron Microscopy Analysis (SEM) of the Thin Film

3.5. Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis (AFM) of the Thin Films

3.6. Density Functional Theory Analysis

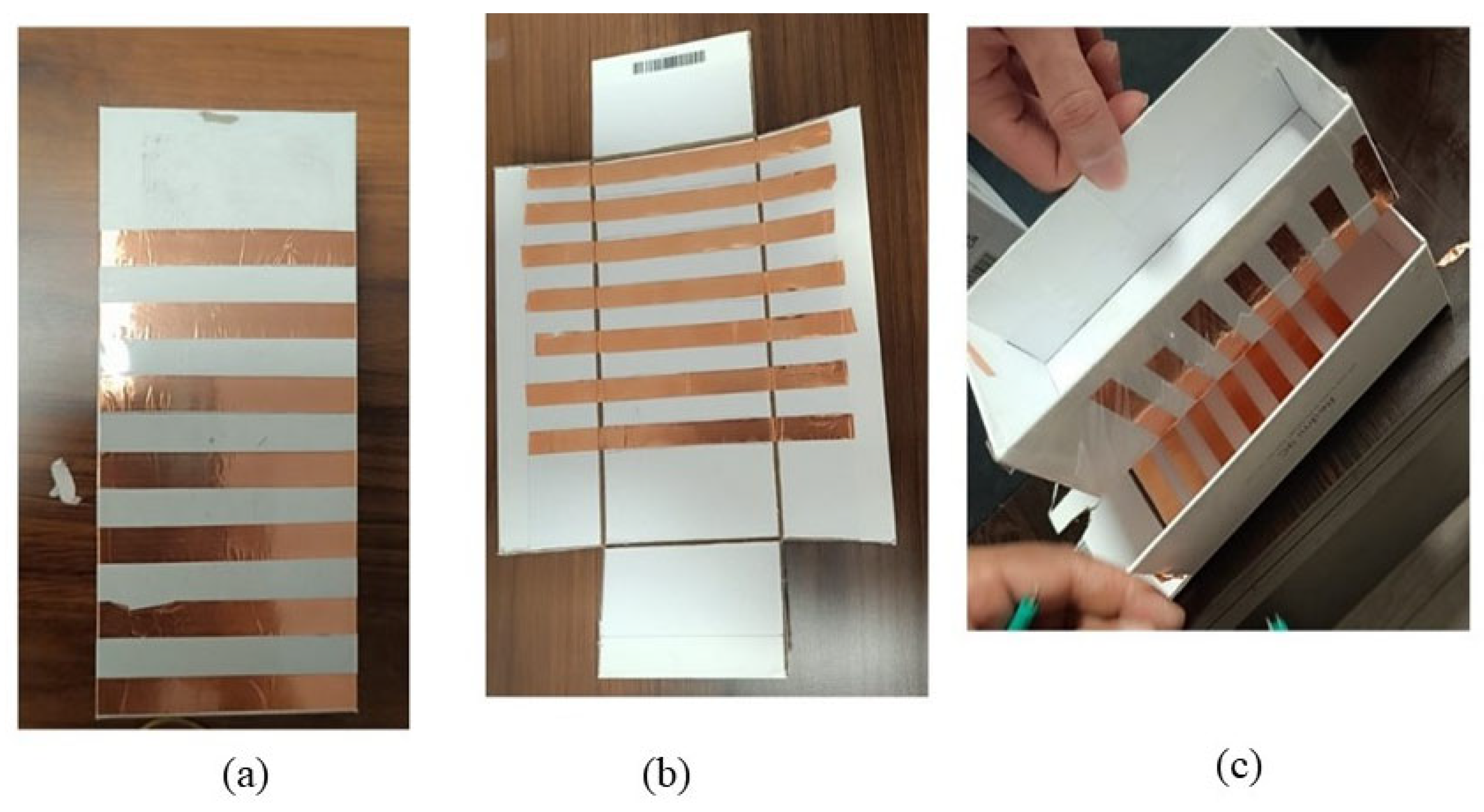

3.7. Fabrication of Hybrid TENG: The Vertical Contactseparation and the Lateral Sliding Mode

3.8. Electrical Measurements of TENG Device

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Fan, F.-R.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Lin, L. Progress in triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology and self-powered sensors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2250–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.; Inman, D. Energy Harvesting Technologies; Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sodano, H.A.; Inman, D.J.; Park, G. A Review of Power Harvesting from Vibration Using Piezoelectric Materials. Shock. Vib. Dig. 2004, 36, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology: materials, systems, and applications. Mater. Today 2014, 17, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; et al. Wearable triboelectric nanogenerator for powering portable electronics. Nano Energy 2015, 16, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Nanoscale Triboelectric-Effect-Enabled Energy Conversion for Sustainably Powering Portable Electronics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6339–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Lee, Y.; Lin, Z.-H.; Cho, S.; Kim, M.; Ao, C.K.; Soh, S.; Sohn, C.; Jeong, C.K.; Lee, J.; et al. Recent Advances in Triboelectric Nanogenerators: From Technological Progress to Commercial Applications. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 11087–11219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theory of Sliding-Mode Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6184–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinchet, R.; Ghaffarinejad, A.; Lu, Y.; Hasani, J.Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Basset, P. Understanding and modeling of triboelectric-electret nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2018, 47, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Nanoscale Triboelectric-Effect-Enabled Energy Conversion for Sustainably Powering Portable Electronics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6339–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmasena, R.D.I.G.; Jayawardena, K.D.G.I.; Mills, C.A.; Deane, J.H.B.; Anguita, J.V.; Dorey, R.A.; Silva, S.R.P. Triboelectric nanogenerators: providing a fundamental framework. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jing, Q.; Niu, S.; Yang, J.; Hong, Y.; Zi, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Nanogenerator integrated into pavement for self-powered vehicle sensors. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Anithkumar, M.; Prasanna, A.P.S.; Hussain, N.; Kim, S.-J.; Mobin, S.M. Triboelectric nanogenerators enhanced by a metal–organic framework for sustainable power generation and air mouse technology. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 26531–26542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.; Saqib, Q.M.; Ameen, S.; Patil, S.R.; Patil, C.S.; Kim, J.; Ko, Y.; Kim, B.; Bae, J. Controlling Triboelectric Charge of MOFs by Leveraging Ligands Chemistry. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2404993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsiwal, S.; Babu, A.; Khanapuram, U.K.; Potu, S.; Madathil, N.; Rajaboina, R.K.; Mishra, S.; Divi, H.; Kodali, P.; Nagapuri, R.; et al. ZIF-67-Metal–Organic-Framework-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Devices. Nanoenergy Adv. 2022, 2, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, B.C.; Hajra, S.; Priyadarshini, A.; Panda, S.; Vivekananthan, V.; Swain, J.; Swain, S.; Das, N.; Samantray, R.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Innovative Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework by a Stovetop Kitchen Pressure Cook Pot for Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2400099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Gupta, M.K.; Zhang, H.; Tien, N.T.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator–ink for printing flexible electronics and self-powered pressure sensors. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd9558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.B.; Zhang, C.; Tang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting energy from low-frequency vibrations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.K.; Han, J.H.; Lee, J.H. High-efficiency electromagnetic–triboelectric hybrid nanogenerator for broadband vibration energy harvesting. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3329–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Zhu, J.; Shen, P.; Wang, Z.L.; Cheng, T. Driving-torque self-adjusted triboelectric nanogenerator for effective harvesting of random wind energy. Nano Energy 2022, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Sun, J.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, Z.L. Ultrastretchable, transparent triboelectric nanogenerator as electronic skin for biomechanical energy harvesting and tactile sensing. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, M.; Liu, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Yan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, L.; Sun, C.-L.; He, J. Stearic Acid-Enhanced Triboelectric Nanogenerators with High Waterproof, Output Performance, and Wear Resistance for Efficient Harvesting of Mechanical Energy and Self-Powered Sensing for Human Motion Monitoring. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ji, L.; Pu, X. Self-powered, broadband vibration sensor based on a hybrid triboelectric-piezoelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Bai, P.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Efficient water-solid triboelectric nanogenerator via direct charge transmission. Nano Energy 2019, 60, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lin, L.; Ding, W.; Wang, Z.L. Material selection rule for high-output triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2021, 79, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.L. A simple model for single-electrode triboelectric nanogenerators: analysis of flat plates. Nano Energy 2017, 31, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chen, J.; He, X.; Wang, Z.L. A high-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on a multi-layered structure for low-frequency mechanical energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2020, 68, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Thapa, K.; Ojha, G.P.; Seo, M.-K.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.-W.; Sohn, J.I. Metal-organic frameworks-based triboelectric nanogenerator powered visible light communication system for wireless human-machine interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Fan, L.; Li, Q.; Zhai, J. A composite triboelectric nanogenerator based on flexible and transparent film impregnated with ZIF-8 nanocrystals. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 346003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Nan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xu, H. Enhanced of ZIF-8 and MXene decorated triboelectric nanogenerator for droplet energy harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 454, 160137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potu, S.; Navaneeth, M.; Bhadoriya, A.; Bora, A.; Sivalingam, Y.; Babu, A.; Velpula, M.; Gollapelli, B.; Rajaboina, R.K.; Khanapuram, U.K.; et al. Enhancing Triboelectric Nanogenerator Performance with Metal–Organic-Framework-Modified ZnO Nanosheets for Self-Powered Electronic Devices and Energy Harvesting. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 22701–22710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Xu, T.; Tan, J.-C. Triboelectric Nanogenerators Based on Composites of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks Functionalized with Halogenated Ligands for Contact and Rotational Mechanical Energy Harvesting. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 4567–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.-Z.; Luo, C.; Zhao, J.-N.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Yin, B.; Zhang, K.; Ke, K.; et al. Metal–Organic Framework Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for a Self-Powered Methanol Sensor with High Sensitivity and Selectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 45855–45867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, G.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Raj, N.P.M.J.; Kim, S. Metal–Organic Framework: A Novel Material for Triboelectric Nanogenerator–Based Self-Powered Sensors and Systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potu, S.; Navaneeth, M.; Bhadoriya, A.; Bora, A.; Sivalingam, Y.; Babu, A.; Velpula, M.; Gollapelli, B.; Rajaboina, R.K.; Khanapuram, U.K.; et al. Enhancing Triboelectric Nanogenerator Performance with Metal–Organic-Framework-Modified ZnO Nanosheets for Self-Powered Electronic Devices and Energy Harvesting. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 11234–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Ni, Z.; Côté, A.P.; Choi, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Chae, H.K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10186–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.C.; Fordham, S.; Zuluaga, S.; Cheetham, A.K.; Bennett, T.D. Mechanical resilience of zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF 8: Pressure induced amorphization and recovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8551–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; … Fox, D.J. (2016). Gaussian 16, Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc.

- Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.L. Achieving ultrahigh triboelectric charge density for efficient energy harvesting. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Kim, Y.; Yu, S.; Kim, M.-O.; Park, S.-H.; Cho, S.M.; Velusamy, D.B.; Cho, S.H.; Kim, K.L.; Kim, J.; et al. Molecularly Engineered Surface Triboelectric Nanogenerator by Self-Assembled Monolayers (METS). Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4749–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zi, Y.; Zhou, Y.S.; Li, S.; Fan, F.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Molecular surface functionalization to enhance the power output of triboelectric nanogenerators. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 3728–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brukerstein, J.I.; Newbury, D.E.; Joy, D.C.; Lyman, C.E.; Echlin, P.; Lifshin, E.; … Michael, J.R. (2003). Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis (3rd ed.). Springer.

- Guo, H.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered sensors and systems. Advanced Materials, 2020, 32, 2002348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R. Dynamic atomic force microscopy methods. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2002, 47, 197–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckelee Corporation. (2014). Dimension Icon Atomic Force Microscope User Manual (Version 8.15). Bruker Corporation.

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.T.; Rana, S.S.; Abu Zahed, M.; Lee, S.; Yoon, E.-S.; Park, J.Y. Metal-organic framework-derived nanoporous carbon incorporated nanofibers for high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators and self-powered sensors. Nano Energy 2022, 94, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, C. Fabrication and performance evaluation of hybrid electromagnetic–triboelectric nanogenerators. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpula, M.; Navaneeth, M.; Potu, S.; Mandal, T.; Bochu, L. High-performance MOF-303-based triboelectric nanogenerators for road energy harvesting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 5000–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, W.; Wang, X. Enhancing low-frequency energy harvesting of triboelectric nanogenerators via surface microstructuring. Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Pang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.L. Integrated triboelectric nanogenerator array for simultaneous harvesting of water wave energy and wind energy. iScience 2021, 24, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhao, J.; Liu, T.; Luo, B.; Chi, M.; Zhang, S.; Cai, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; et al. Strong and Stable Woody Triboelectric Materials Enabled by Biphase Blocking. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 14932–14940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigaku Oxford Diffraction. (2018). CrysAlisPro (Version 1.171.41.93a) [Data collection and processing software].

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keithley Instruments, Inc. (2018). Model 2450 SourceMeter® Source Measure Unit: User’s Manual. Beaverton, OR: Keithley Instruments, Inc.

- National Instruments. (2020). NI Measurement & Automation Explorer (MAX) User Manual (Document Number 378443A 01). Austin, TX: National Instruments.

| Bond Lengths (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Theoretical | |

| Zn1N1 | 2.028(4) | 2.02805 |

| Zn1N11 | 2.028(4) | 2.02868 |

| Zn1N12 | 2.028(4) | 2.02832 |

| Zn1N13 | 2.028(4) | 2.02785 |

| N1C1 | 1.347(6) | 1.34814 |

| N1C2 | 1.281(6) | 1.27991 |

| N1C14 | 1.257(11) | 1.25865 |

| C2C3 | 1.562(12) | 1.56300 |

| Bond Angles( | ||

| Experimental | Theoretical | |

| N1Zn1N11 | 109.11(11) | 102.08207 |

| N1Zn1N13 | 109.11(11) | 109.10786 |

| N1Zn1N12 | 110.2(3) | 109.12354 |

| N1Zn1N13 | 110.2(3) | 109.12780 |

| C2N1Zn1 | 129.0(4) | 129.10616 |

| C1N1Zn1 | 127.1(3) | 126.98515 |

| MOF System | Power Density (mW·m⁻²) | Conditions / Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| This work (236 MΩ load) | 87.3 | 2 Hz, matched load (A = 8.25 cm²) | This work |

| This work (open-circuit) | 839.1 | 2 Hz, open-circuit (A = 8.25 cm²) | This work |

| ZIF-8/MO-PPy@CelF | 33.3 | Low-frequency, PTFE counter pair | Zhang et al., “Methyl Orange-Doped Polypyrrole Promoting Growth of ZIF-8 on Cellulose Fiber for TENG,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2021 (PubMed) |

| ZIF-8 + MIL-100 in PAN | 18.4 | Electrospun PAN/MIL-100 composite | Liu et al., “Electrospun ZIF-8/MIL-100 Nanofiber Composites for TENGs,” J. Mater. Chem. A, 2022 |

| ZIF-8 hydrogel TENG | 3 470 | 2 wt% ZIF-8 hydrogel, matched load | Wang et al., “High-Performance Hydrogel-Based ZIF-8 TENG,” Adv. Funct. Mater., 2022 (Cell) |

| ZIF-67/PMMA | 593 | PMMA thin film | Kim et al., “ZIF-67/PMMA Composite for Enhanced TENG Output,” Nano Energy, 2023 (Cell) |

| ZIF-67 (direct growth on substrate) | 2 350 | Bare ZIF-67 layer | Li et al., “Direct Growth of ZIF-67 on Substrates for TENGs,” Chem. Eng. J., 2021 (ACS Publications) |

| ZIF-67 on cellulosic fabric | 5 | 800 MΩ load | Chen et al., “Cellulosic Fabric Coated with ZIF-67 for TENGs,” ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., 2020 (ResearchGate) |

| MOF-modified ZnO/PAN | 800 | ZIF-8 or MIL-100 in ZnO/PAN matrix | Liu et al., “ZnO/PAN Nanocomposites with ZIFs for Triboelectric Harvesting,” Mater. Today Energy, 2023 (ResearchGate) |

| Name | Molecule |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C8H10N4 Zn |

| Formula weight | 227.57 |

| Temperature (K) | 295(2) |

| Crystal system | cubic |

| Space group | I-43m |

|

Unit cell dimensions a (Å) b (Å) c (Å) (⁰) β (⁰) |

16.9887(2) 16.9887(2) 16.9887(2) 90 90 90 |

| Volume/(Å3) | 4903.21(17) |

| Z | 12 |

| Dcalc (g/cm-3) | 0.925 |

| Absorption coefficient (mm-1) | 1.477 |

| F (000) | 1392.0 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.31× 0.25 × 0.23 |

| h ranges | -21→21 |

| k range | -21→21 |

| l range | -21→21 |

| Reflections collected/unique | 5673/3182 |

| Data / restrains / parameters | 3543/967/35 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 1.065 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0338 wR2 = 0.0955 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0352 wR2 = 0.0966 |

| Largest difference peak and hole (e Å-3) | 0.33/-0.18 |

| Flack parameter | 0.29(3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).