1. Introduction

Drying is a unit operation widely used in chemical, food, agricultural, wastewater treatment and pharmaceutical industries to remove water from solids through heat and mass exchanges.

One of the most used equipment to perform drying is the rotary dryer because of its adaptability and flexibility in processing materials that are not heating sensitive or fragile [

1]. A rotary dryer is composed of a slightly inclined cylindrical shell or drum (length: 5-90m, diameter: 0.3-5m) with internal lifting flights. The cylinder rotates around a shaft in such a manner that the solid to be dried is fed in at the upper part of the cylinder and descends through the flights towards the discharging end. The drying medium (usually hot air) can be directly or indirectly in contact with the wet solid, and it can be operated in concurrent or countercurrent flow mode [

2].

There exist diverse evaluation criteria for the performance of a rotary dryer and some of these are: drying efficiency which is computed considering initial, final and equilibrium moisture content [

3] and energy efficiency that represents the ratio between the amount of energy used for evaporation of moisture and the total energy consumption [

4]. Although rotary dryers are characterized by their relative high drying efficiency for diverse wet solids (e.g., around 85% in the case of sewage sludge [

5], 95% in the case of wood particles [

6] and up to 98% in the case of lateritic ore [

7]) they are also distinguished by their relative low energy efficiency (between 2% and 17% for paddy drying [

8]). According to Kaveh et al., (2021) this fact could lead to an increase of emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) with negative environmental effects [

9]. Furthermore, Perazzini et al., (2021) indicate that 10 to 20% of the total energy in industrialized countries is used for drying making it a highly demanding power operation [

10]. Another drawback of rotary dryers is related to their economic performance. In the case of biological sludge dewatering, the internal rate of return for a thermal rotary dryer can be around 27% which is higher than that usually expected. Besides, the ratio between the total operating cost and the total capital cost can reach more than 0.5 [

11]. Moreover, drying has been reported as a hazardous industrial operation for the number of reported incidents with serious results for personnel and equipment [

12].

Despite these limitations, rotary dryers are still widely used in industry due to their ability to continuously dry large quantities of material in a relatively short period and their ease of adjustment of operating conditions such as residence time and rotation speed [

3]; therefore, training of students or professionals in rotary dryers is required. An innovative tool that has been recently considered for training is Virtual Reality (VR) [

13]. Basically, VR is a digital or computer-generated representation (in 3D) of a real (or invented) space that can be explored from diverse angles and in which interaction is possible through head-mounted displays and other accessories. Training for rotary dryers in a VR atmosphere would decrease drastically efficiency, environmental, economic and industrial safety issues associated with the use and training in real rotary dryers and therefore it can be considered as a sustainable practice. Furthermore, VR training for rotary dryers could be considered an immersive and effective learning experience if the VR environment works as close to reality as possible. This can be achieved by incorporating as much as possible both visual and behavioral aspects of the real-world equipment, system or process into its digital version in VR environments [

14]. To the best of our knowledge, most efforts to engineer digital versions of equipment in such environments are focused on improving their visual aspects but little has been done to improve their behavioral aspects.

This contribution seeks to enhance behavioral realism of a digital rotary dryer in a VR environment by incorporating and numerically integrating validated mathematical models given by ordinary differential equations. The model depicts the drying process taking place within the digital rotary dryer with the following variables: water content and temperature of both the solid to be dried and the drying medium (i.e., hot air) along and within the rotary dryer. Two case studies were explored: the drying of ammonium nitrate, due to its importance in the fertilizers industry and the drying of low-rank coal (LRC) or sub-bituminous coal which is a promising energy resource provided it remains dry.

The paper is organized as follows. The methodology section describes visual aspects of a proposed digital industrial rotary dryer. Behavioral aspects of the digital dryer are also addressed as a part of the methodology section. This is done through the description of the mathematical model that governs the digital dryer and their corresponding drying kinetics for ammonium nitrate and low-rank coal. Next, the Results section addresses the following topics: description of the VR environment, interaction in the VR environment, expansion of such an environment and simulation results of the mathematical model for both case studies. These simulation results were embedded in 2 different VR environments, one for each case study, that are identical in what concerns visual aspects but with differences in their behavioral aspects since they are governed by different drying kinetics. In the Discussion section, the behavior of the state variables considered in the mathematical models is analyzed and the enhancement of the VR environment is demonstrated. Finally, the conclusions section summarizes the main findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Visual Aspects of the Digital Rotary Dryer in the VR Environment

The rotary dryer in the VR environment was designed to work in concurrent flow mode with the following components: cylindrical drum, internal lifting flights, roller rings supported by carrier rollers distributed along the drum, a primary gear or gear ring connected to a motor gear by a drive chain, a feed hopper, a feeding cover, a burner, an induced draft fan and a couple of control panels (see

Figure 1). These components were first sketched individually in Blender considering industrial dimensions for the characteristic lengths of the rotary dryer reported by Abbasfard et al., (2013) and those mentioned in the introduction section of the present paper: 18m length, 3.324m inside diameter and 0.025m/m slope for the drum [

15].

2.2. Behavioral Aspects of the Digital Rotary Dryer in the VR Environment

2.2.1. Mathematical Model of an Industrial Rotary Dryer

In order to enhance behavioral realism of the rotary dryer in the VR environment, a steady state one-dimensional mathematical model is proposed to be included in such an environment. This model depicts water content and temperature of both the solid to be dried and the air along and within the rotary dryer drum and it was developed under the following assumptions: the heat exchange from the drum to the surroundings is neglected, the solids to be dried have a spherical shape and their dimensions and heat capacities remain constant, the drying process is conducted below critical moisture content (i.e., in the falling-rate period of the drying process), the flows of solids and air follow a plug flow model, diffusion and dispersion through the axial direction is not considered, back-mixing, potential and kinetic energy are neglected. The model is given by the following set of ordinary differential equations:

where

is a dimensionless normalized length of the rotary dryer drum (i.e.,

) defined as

where

is the length of the drum, whereas

is the coordinate indicating the direction of both solid and air flows. In addition,

,

denote the solid moisture (kg water/kg dry solid) and temperature in the solid whereas

and

represent the air absolute humidity (kg water/ kg dry air) and temperature of the air. Boundary conditions of the model are denoted by

,

,

, and

. Besides,

is the drying rate or kinetics,

is the dryer total load which is computed as

(

is the average residence time and

is the dry solid mass flow rate),

is the dry air mass flow rate,

is the internal heat transfer rate,

is the latent heat of vaporization,

,

,

and

are specific heats of the dry solid, of liquid water, of dry air and of water vapor, respectively.

2.2.2. Case Study: Ammonium Nitrate Plant

Abbasfard et al., (2013) [

15] proposed a mathematical model with a similar structure than that described by equations (1) - (4) to describe the drying process of 650 metric tons/day of ammonium nitrate in a rotary dryer. For this process, the model was validated with the following drying kinetics:

where

(with units of min

-1) is the drying constant and

is the equilibrium moisture content calculated as:

where

where

is air relative humidity. In this paper,

was computed as

where

is the operating pressure (assumed as 101325Pa, the atmospheric pressure) and

is the saturation pressure for water obtained from the following equation

that was proposed by Huang [

16].

2.2.3. Case Study: Low-Rank Coal (LRC)

The drying of LRC was addressed using the same mathematical model defined by equations (1) - (4) except that in this case the parameters

and

of the drying rate

were obtained as follows. First, the drying rate can be related to the decrease of the moisture content along the time with the expression

Considering equation (5), the previous equation takes the following form

Then, equation (12) can be integrated resulting in

where

is the moisture content at the beginning of the drying for a certain experiment. On the other hand, Rong et al., (2016) evaluated the dynamics of the moisture content in LRC at 101kPa under different air temperatures (

= 64.85 °C,

= 99.85°C and

= 149.85°C) and they were gathered in

Figure 2 with the software WebPlotDigitalizer [

17].

For each

, an arbitrary value for

can be assumed to plot a graph with

on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. From such a graph, the slope corresponding to

(as defined in equation (13)) and the coefficient of determination or R-squared (

) can be obtained. This procedure was optimized to maximize

yielding the values described in

Table 1.

Finally,

and

were fitted to an exponential expression and to a linear expression with respect to

, respectively resulting in

It was decided to fit to an exponential expression of because that is a standard practice (see equation (6)) whereas was fitted to a linear expression of in order to give a simpler alternative than those usually considered (see equation (7)).

3. Results

3.1. Description of VR Environment

The integration of each one of the rotary dryer components described in

Figure 1 into a VR environment was made in Unity 3D with an Alienware Aurora R8 Gaming Desktop Computer designed for virtual reality (3.2GHz Intel Core i7-9700, 16GB, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060) (see Figure 3). A conveyor belt (not shown in

Figure 1) was also designed and included as an element to transport the solid to be dried from the feeding cover towards the digital rotary dryer.

Figure 3.

Integration of the rotary dryer components into a single VR environment using Unity 3D.

Figure 3.

Integration of the rotary dryer components into a single VR environment using Unity 3D.

Control panel 1 was equipped with digital displays for the temperature of the air, moisture content of the solid at the inlet of the dryer (i.e., the boundary conditions

and

), velocity of the air (

) (which is directly related to the mass flow of the air or

, see Table 3) and rotary dryer drum speed (in rpm). Control panel 1 also has on-off buttons, an emergency stop or E-stop button and a selector switch for the drum’s rotation. Besides, control panel 2 has a couple of digital displays to register the solid that is being dried (between ammonium nitrate or LRC) and the number of solid particles that can be generated from the feed hopper in the VR environment. It was decided to show how the drying occurs in the solid using solid particles (See

Figure 6b) instead of dust-type particles since they allow for easier manipulation and more effective interaction control in VR environments. In this sense, each solid particle has the same value for temperature and moisture content at the inlet of the dryer and these values will change according to the mathematical model and drying kinetics along the dryer drum. Control panel 2 also includes a button to initiate the feeding of solids. Components of Control panel 1 and 2 are described in

Figure 4a-b. The VR environment for the digital rotary dryer was enriched with laboratory workbenches on which a virtual thermometer for the solid, a virtual moisture content meter for the solid and a virtual shovel were placed (see

Figure 5a-b). The shape of the virtual thermometer and the moisture content meter were inspired by common IR thermometers and by common portable moisture meters, respectively.

Figure 4.

(a) Control panel 1 components. Digital displays: inlet air temperature (), inlet air speed or velocity (), inlet material moisture () and rotary dryer drum speed in rpm. Buttons: E-stop, turn on/off for the induced draft fan, burner and rotation of the drum, selector switch to change the drum’s rotation; (b) Control panel 2 components. Digital displays: material selection (ammonium nitrate or LRC) and number of solid particles to be dried. Button: Activates the solid feed system.

Figure 4.

(a) Control panel 1 components. Digital displays: inlet air temperature (), inlet air speed or velocity (), inlet material moisture () and rotary dryer drum speed in rpm. Buttons: E-stop, turn on/off for the induced draft fan, burner and rotation of the drum, selector switch to change the drum’s rotation; (b) Control panel 2 components. Digital displays: material selection (ammonium nitrate or LRC) and number of solid particles to be dried. Button: Activates the solid feed system.

Figure 5.

Additional elements of the VR environment for the digital rotary dryer located on laboratory workbenches. (a) Temperature and moisture content meters for solid; (b) Shovel.

Figure 5.

Additional elements of the VR environment for the digital rotary dryer located on laboratory workbenches. (a) Temperature and moisture content meters for solid; (b) Shovel.

Figure 6.

Interaction in the VR environment (a) solid particles displacement with the shovel and (b) single particle displacement; (c) Temperature and (d) moisture content measurement with virtual thermometer and virtual moisture content meter.

Figure 6.

Interaction in the VR environment (a) solid particles displacement with the shovel and (b) single particle displacement; (c) Temperature and (d) moisture content measurement with virtual thermometer and virtual moisture content meter.

3.2. Interaction in the VR Environment

An Oculus Quest all-in-one VR gaming system headset (128GB, model MH-B) and a pair of Oculus Touch Controllers (MR-BR, Right and MI-BL, Left) were selected as the head-mounted display (HMD) to interact in the VR environment containing the digital rotary dryer. Through this HMD it is possible to increase or to decrease , , and the rotary dryer drum speed by selecting the up or down arrow key in the digital displays of Control Panel 1. All these variables can also be set to their nominal (arbitrary) values by selecting the set button. It is also possible to turn on or turn off the burner or the induced draft fan, to activate the E-stop button or to change the drum rotation in the corresponding buttons placed in Control Panel 1. Interaction also occurs when the type of solid to be dried and the number of solid particles are using the digital displays on Control Panel 2 or when the “start” button is pressed in the same panel.

Using the HMD, users can also interact with the proposed environment by picking up the virtual shovel to manually guide solid particles from the feed hopper to the conveyor belt. Users can also interact with solid single particles from the hopper, placing them directly into the rotary dryer (see

Figure 6a-b). Besides, the temperature and moisture of the solid particles at the inlet of the rotary dryer can be monitored using the thermometer and the moisture meter placed on the laboratory workbenches by pointing them directly to the solid (see

Figure 6c-d).

Transport of solid particles along the rotary dryer can be also visualized with the help of the HMD and they can be extracted at any point along from the dryer drum to analyze their temperature and moisture content. Variations in the color of the solid particles depending on the point from which they have been extracted from the drum (i.e., related to their temperature and moisture content) are also included as a part of the VR experience (see

Figure 7a-c and Supplementary material)

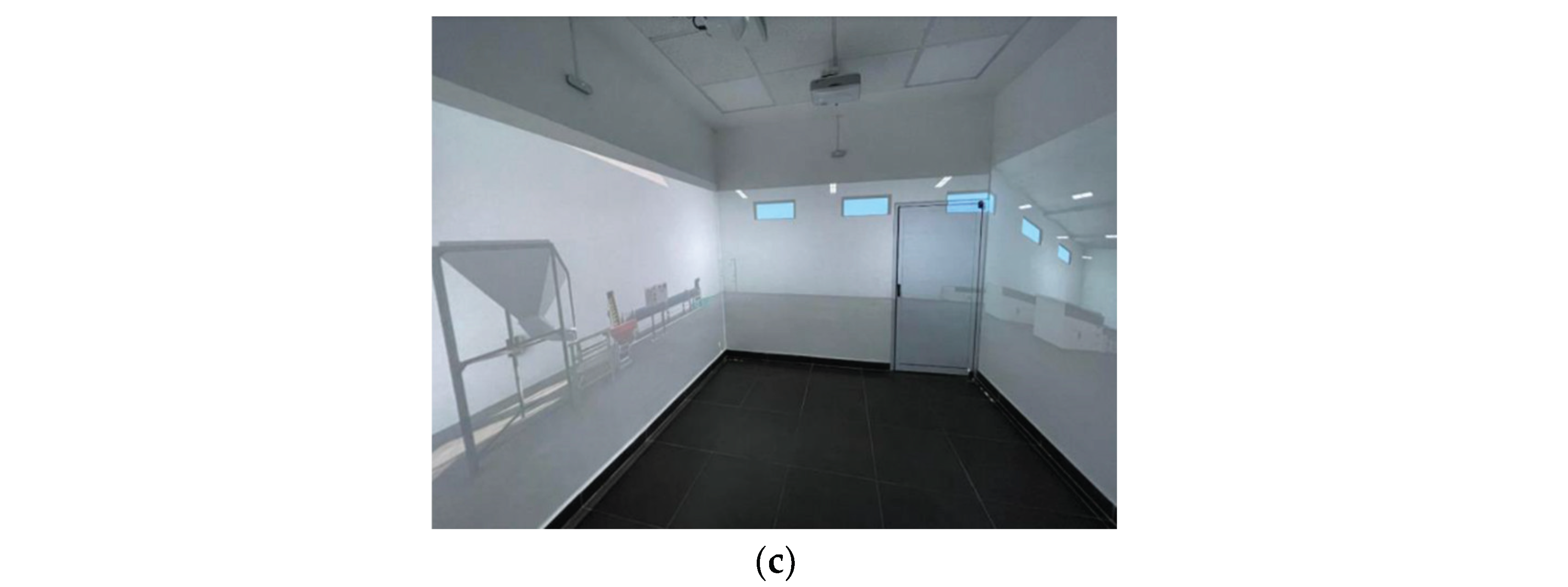

3.3. Expansion of the VR Environment

Interaction in the VR environment through the HMD is limited to one person. In order to expand the VR environment to multiple people, a physical space or virtual cellar at the Chemical Engineering Laboratory of the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara in México was set up with 4 projectors (Epson Home Cinema 2500 ANSI Lumens, V11H852020) supported in the roof and connected to the Alienware Aurora desktop computer and the HMD both remaining outside the virtual cellar (see

Figure 8a-c). Therefore, the VR environment was controlled by one person outside the virtual cellar (generally a teacher) while the rest of the people (generally students) can experience the VR environment inside the virtual cellar.

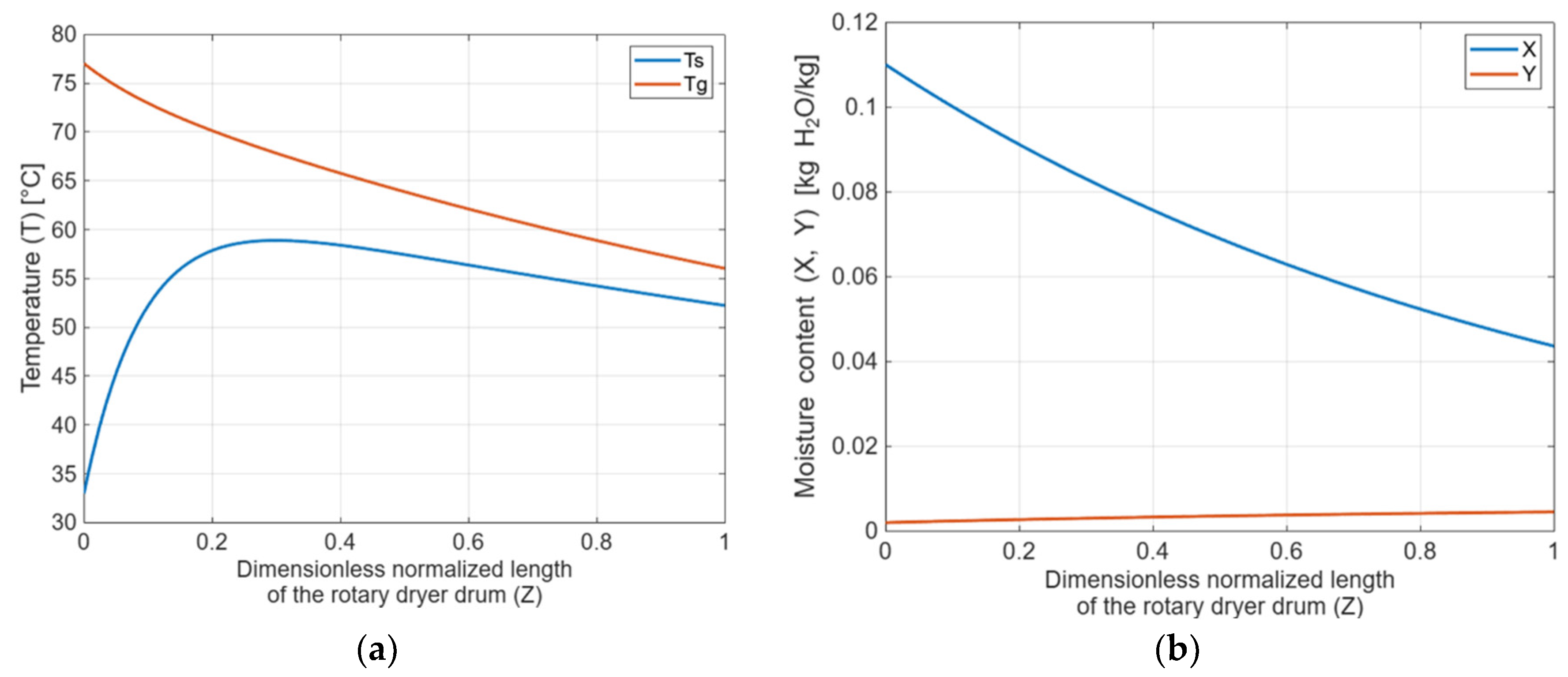

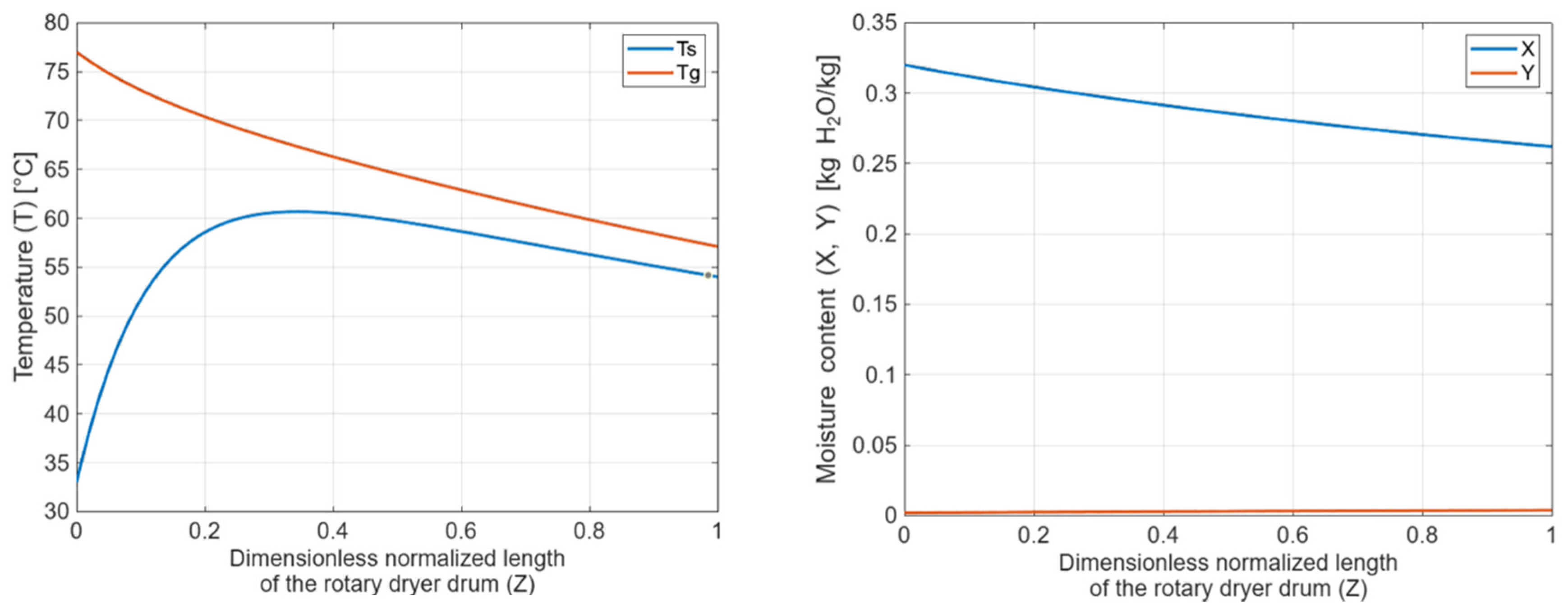

3.4. Simulation Results for Case Studies

The mathematical model for the industrial rotary dryer was solved in Matlab using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method (RK4) for each one of the case studies considering their corresponding drying kinetics. In both cases, the following expressions for Q and were considered. First, Q was computed with the equation

where

is the dryer volume (i.e.,

) and

is the global volumetric heat transfer coefficient that can be computed with

where

is the dryer cross-sectional area. This expression has been derived by Arruda (2006) and is generally accepted for industrial rotary dryers [

18]. Besides,

was computed with the following model proposed by Watson (1943)

where

is the latent heat of vaporization at temperature

whereas

is the critical temperature. In this work, the following values were considered for water:

=2257.06KJ/Kg at

=100°C and

=374.14°C [

19].

On the other hand, the heat capacities for air and water as a vapor were computed from the following equation proposed by NASA (1971)

where

=

or

(Air or water),

is the molar mass of the

-th species and while parameters are depicted in

Table 2 [

20].

In addition, the heat capacities for liquid water and for the solids were considered constants with the following values

=4.18KJ/(kg°C) and

= 1.56KJ/(kg°C) for the ammonium nitrate and

= 1.3KJ/(kg°C) for the LRC. Finally, the rotary dryer drum speed was set at 3 rpm. Given the characteristic lengths of the rotary dryer (i.e., 18m length, 3.324m inside diameter and 0.025m/m slope) this leads to an average residence time of 30min (i.e., = 30min) (Abbasfard et al., 2013). The boundary and operational conditions depicted in

Table 3 were considered to obtain the simulation results shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 for the nitrate plant and for the LRC case studies, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. On the Behavior of the State Variables

For both case studies, temperature of the air () decreases along the dryer drum. This can be explained due to mass and energy interactions of the air with a solid which has a lower temperature. Regarding the temperature of the solid an increase is observed in both cases. Nevertheless, in the ammonium nitrate drying, the temperature of the solid () reaches a maximum around =0.2 while in the case of LRC drying, temperature of the solid also reaches a maximum but this occurs after =0.2. This different behavior can be attributed to the different parameters in the drying kinetics of the ammonium nitrate and LRC. The influence in drying kinetics is also shown in the behaviour of the solid moisture () along the dryer drum. Although in both case studies decreases as expected, the decrease is noticeably faster for ammonium nitrate than for LRC. Notice that water lost by the solids is absorbed into the air, as shown by the increase in the absolute humidity of air () in both drying cases.

4.2. Enhancing the VR Environment

The development of equipment in VR environments is generally focused on improving visual aspects leaving aside behavioral realism. In this contribution, whilte the visual features of the digital rotary dryer in the VR environment were addressed, equal attention was given tu accurately representing the behavioral aspects of the dryer. To enhance the realism of the digital dryer, the mathematical model described by equations (1-4), their corresponding drying kinetics depending on the case study and the numerical method to solve the model (i.e., RK4) were transferred from Matlab into Unity 3D. This transfer represented a technical challenge because the programming language in Matlab (M-Code) that combines C, Fortran and Python characteristics is different than that used by Unity 3D which is C#. The challenge was overcome by using Visual Studio Code as translator of the M-Code to C#. Then, it can be said that the proposed VR environment for the industrial rotary dryer is enhanced in comparison to most available VR environments as one of its main components, the digital dryer, is governed by a validated mathematical model. This feature of the VR environment is present in the measurements recorded by the virtual thermometer and by virtual moisture content meter that correspond to the numerical values of Ts and X, respectively that are produced by the integrated mathematical model. At this point, it is important to remark that 2 different VR environments were developed, one for each case study. The VR environments are identical in in terms of visual aspects but they differ from each other in their behavioral aspects because they are governed by different drying kinetics.

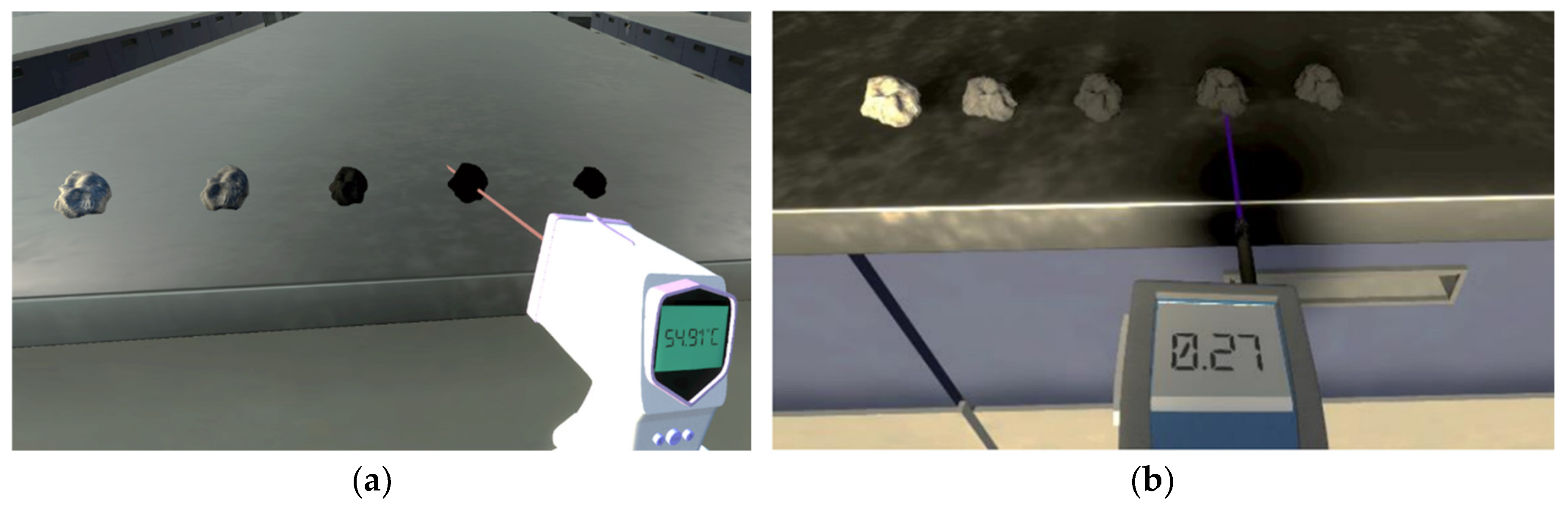

Finally, two examples are given to illustrate enhancements of the VR environments. First, the VR environment for ammonium nitrate is launched. In this case, solid samples are extracted along the dryer drum at the following positions z=0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1 and are placed over a virtual workbench. When the virtual thermometer and is pointed at the sample located at z=0.75, a temperature of 54.91°C is recorded (see

Figure 11a). This value clearly corresponds to the one shown in

Figure 9 for Ts at z=0.75. Next VR environment for LRC is launched. Similarly solid samples are also extracted at the same z positions and placed on a virtual workbench. In this case, the moisture content meter is taken and is pointed at the sample located at z=0.75 yielding a moisture content of 0.27 (see

Figure 11b). This value corresponds to that for X at z=0.75 in

Figure 10. Taken together, these examples demonstrate that the values generated for Ts and X in the VR environments are consistent to those provided by a validated mathematical model.

5. Conclusions

A couple of VR environments for the drying of ammonium nitrate and LRC in industrial rotary dryers were developed in Unity 3D. These environments provide, through digital devices, numerical values for temperature and moisture content of the solid to be dried. These values were obtained from the numerical integration of mathematical models with validated drying kinetics for the corresponding case studies. As a result, the proposed VR environments could serve not only as visualization platforms but also as impactful training systems for people dealing with industrial rotary dryers, as they are able to replicate real-world behavior using mathematical modelling techniques. The VR environments have been officially registered in Mexico (through INDAUTOR) under the following number: 03-2023-050410553100-01. The methodology proposed in this contribution could be expanded for the design of other virtual equipment particularly those whose real versions can also be depicted by validated mathematical models. In this sense, future work will focus on incorporating mathematical models using time as a state variable in order to provide real-time responses in the VR environment.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Jonathan Rosales-Hernández; Funding acquisition, Efrén Aguilar-Garnica; Methodology, Ricardo Gutiérrez-Aguiñaga and Rogelio Salinas-Santiago; Project administration, Efrén Aguilar-Garnica; Software, Ricardo Gutiérrez-Aguiñaga and Rogelio Salinas-Santiago; Validation, Ricardo Gutiérrez-Aguiñaga and Froylán Escalante; Visualization, Jonathan Rosales-Hernández; Writing – original draft, Efrén Aguilar-Garnica; Writing – review & editing, Ricardo Gutiérrez-Aguiñaga, Jonathan Rosales-Hernández and Froylán Escalante. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This research was funded by Decanato de Diseño, Ciencia y Tecnología. Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, México.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Mtro. Joel García Ornelas for his invaluable support in the creation of the virtual cellar at the Chemical Engineering Laboratory at the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara. They also thank “Fondo Semilla” of the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara for covering the APC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| LRC |

Low Rank Coal |

| HMD |

Head Mounted Display |

References

- Malekjani, N.; Poureshmanan Talemy, F.; Zolqadri, R.; Jafari, S.M. Roller/drum dryers and rotary dryers. In Drying Technology in Food Processing; Jafari, S.M., Malekjani, N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 47–66. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, H.; Sokhansanj, S. A review on determining the residence time of solid particles in rotary drum dryers. Dry. Technol. 2021, 39, 1762–1772. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2021.1912.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196.

- Gómez-de la Cruz, F.J.; Palomar-Torres, A.; Palomar-Carnicero, J.M.; Cruz-Peragón, F. Energy and exergy analysis during drying in rotary dryers from finite control volumes: Applications to the drying of olive stone. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 200, 117699. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Yu, Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Huo, H.; Su, F.; Wen, Z. Energy efficiency analysis of a rotating-drum dryer using hot steel balls for converter sludge. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 49, 103389. [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.; Lim, M.; Yoshikawa, K. Development of a high-efficiency rotary dryer for sewage sludge. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2012, 14, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinabadi, H.Z.; Layeghi, M.; Berthold, D.; Doosthosseini, K.; Shahhosseini, S. Mathematical modeling the drying of poplar wood particles in a closed-loop triple pass rotary dryer. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 55–67. [CrossRef]

- Rojas Vargas, A.; Pérez García, L.; Sánchez Guillen, C.; AlJaberi, F.Y.; Salman, A.D.; Alardhi, S.M.; Le, P.-C. Performance evaluation of a flighted rotary dryer for lateritic ore in concurrent configuration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21132. [CrossRef]

- A’yuni, D.; Subagio, A.; Prasetyaningrum, A.; Sasongko, S.; Djaeni, M. The optimization of paddy drying in the rotary dryer: Energy efficiency and product quality aspects analysis. Food Res. 2024, 8(S1), 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, M.; Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Nowacka, M. Comparison of different drying techniques and their carbon emissions in green peas. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 160, 108274. [CrossRef]

- Perazzini, H.; Perazzini, M.T.B.; Freire, F.B.; Freire, F.B.; Freire, J.T. Modeling and cost analysis of drying of citrus residues as biomass in rotary dryer for bioenergy. Renew. Energy 2021, 175, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- El-Qanni, A.; Alsayed, M.; Alsurakji, I.H.; Najjar, M.; Odeh, D.; Najjar, S.; Hmoudah, M.; Zubair, M.; Russo, V.; Di Serio, M. A technoeconomic assessment of biological sludge dewatering using a thermal rotary dryer: A case study of design applicability, economics, and managerial feasibility. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 13055–13069. [CrossRef]

- Markowski, A.S. Assessment of safety measures in drying systems. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 517–526. [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Gutworth, M.B.; Jacobs, R.R. A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106808. [CrossRef]

- Arias, S.; Wahlqvist, J.; Nilsson, D.; Ronchi, E.; Frantzich, H. Pursuing behavioral realism in virtual reality for fire evacuation research. Fire Mater. 2021, 45, 462–472. [CrossRef]

- Abbasfard, H.; Rafsanjani, H.H.; Ghader, S.; Ghanbari, M. Mathematical modeling and simulation of an industrial rotary dryer: A case study. Powder Technol. 2013, 239, 499–505. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. A simple accurate formula for calculating saturation vapor. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2018, 57, 1265–1272. [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Song, B.; Yin, W.; Bai, C.; Chu, M. Drying behaviors of low-rank coal under negative pressure: Kinetics and model. Dry. Technol. 2016, 35, 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Arruda, E.B. Comparison of the Performance of the Roto-Fluidized Dryer and Conventional Rotary Dryer; Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Brazil, 2006.

- Watson, K.M. Thermodynamics of the liquid state – Generalized prediction of properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1943, 35, 398–406. [CrossRef]

- NASA. SP-273; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1971.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).